TL;DR#

Estimating amino acid substitution rate matrices is computationally expensive, hindering research in evolutionary biology and variant effect prediction. Traditional methods struggle with massive datasets common in modern genomics. This limitation affects studies involving protein evolution and predicting the effects of genetic mutations on protein function.

This paper introduces a groundbreaking near linear-time method, “FastCherries,” significantly speeding up the process. Combined with CherryML, it allows for the estimation of site-specific rate matrices, leading to a new model called SiteRM. SiteRM outperforms large protein language models in predicting variant effects. The improved scalability and accuracy open new possibilities in evolutionary biology and computational variant effect prediction.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in phylogenetics and variant effect prediction. It offers a significantly faster method for estimating amino acid substitution rates, a fundamental task in evolutionary biology. The method’s scalability enables analysis of massive datasets, previously impossible, opening avenues for new discoveries in protein evolution and improving variant effect prediction, impacting fields like drug discovery and personalized medicine.

Visual Insights#

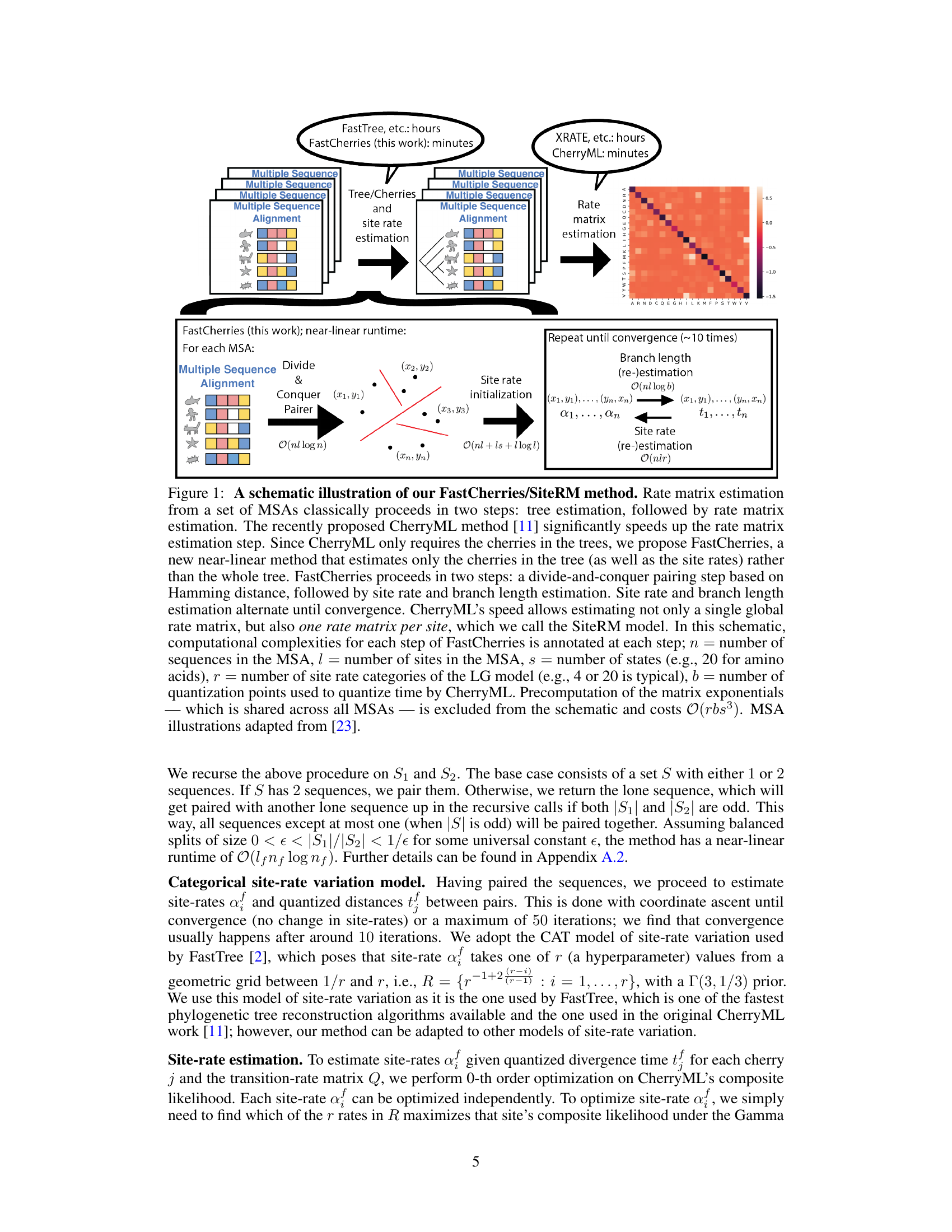

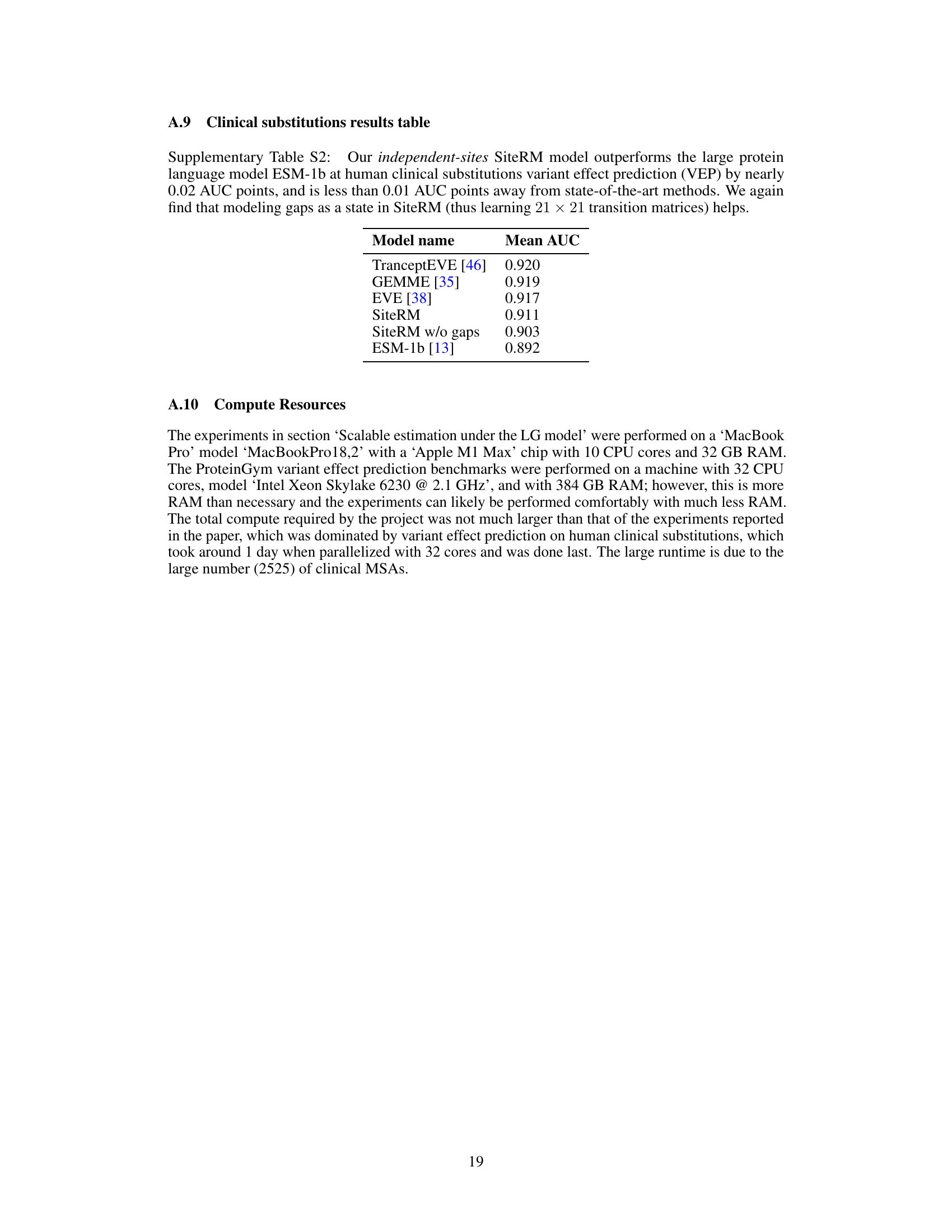

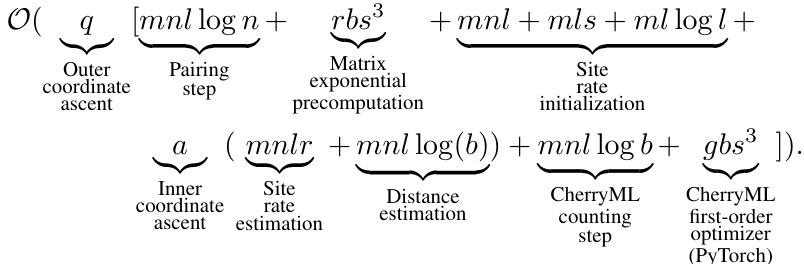

🔼 This figure illustrates the FastCherries/SiteRM method, a two-step process for rate matrix estimation from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). It contrasts the traditional method, which involves computationally expensive tree reconstruction, with the proposed method, FastCherries, which avoids this step. FastCherries uses a divide-and-conquer approach to find pairs of sequences, followed by iteratively estimating site rates and branch lengths. The figure also shows the SiteRM model which allows for site-specific rate matrices.

read the caption

Figure 1: A schematic illustration of our FastCherries/SiteRM method. Rate matrix estimation from a set of MSAs classically proceeds in two steps: tree estimation, followed by rate matrix estimation. The recently proposed CherryML method [11] significantly speeds up the rate matrix estimation step. Since CherryML only requires the cherries in the trees, we propose FastCherries, a new near-linear method that estimates only the cherries in the tree (as well as the site rates) rather than the whole tree. FastCherries proceeds in two steps: a divide-and-conquer pairing step based on Hamming distance, followed by site rate and branch length estimation. Site rate and branch length estimation alternate until convergence. CherryML's speed allows estimating not only a single global rate matrix, but also one rate matrix per site, which we call the SiteRM model. In this schematic, computational complexities for each step of FastCherries is annotated at each step; n = number of sequences in the MSA, l = number of sites in the MSA, s = number of states (e.g., 20 for amino acids), r = number of site rate categories of the LG model (e.g., 4 or 20 is typical), b = number of quantization points used to quantize time by CherryML. Precomputation of the matrix exponentials which is shared across all MSAs is excluded from the schematic and costs O(rbs³). MSA illustrations adapted from [23].

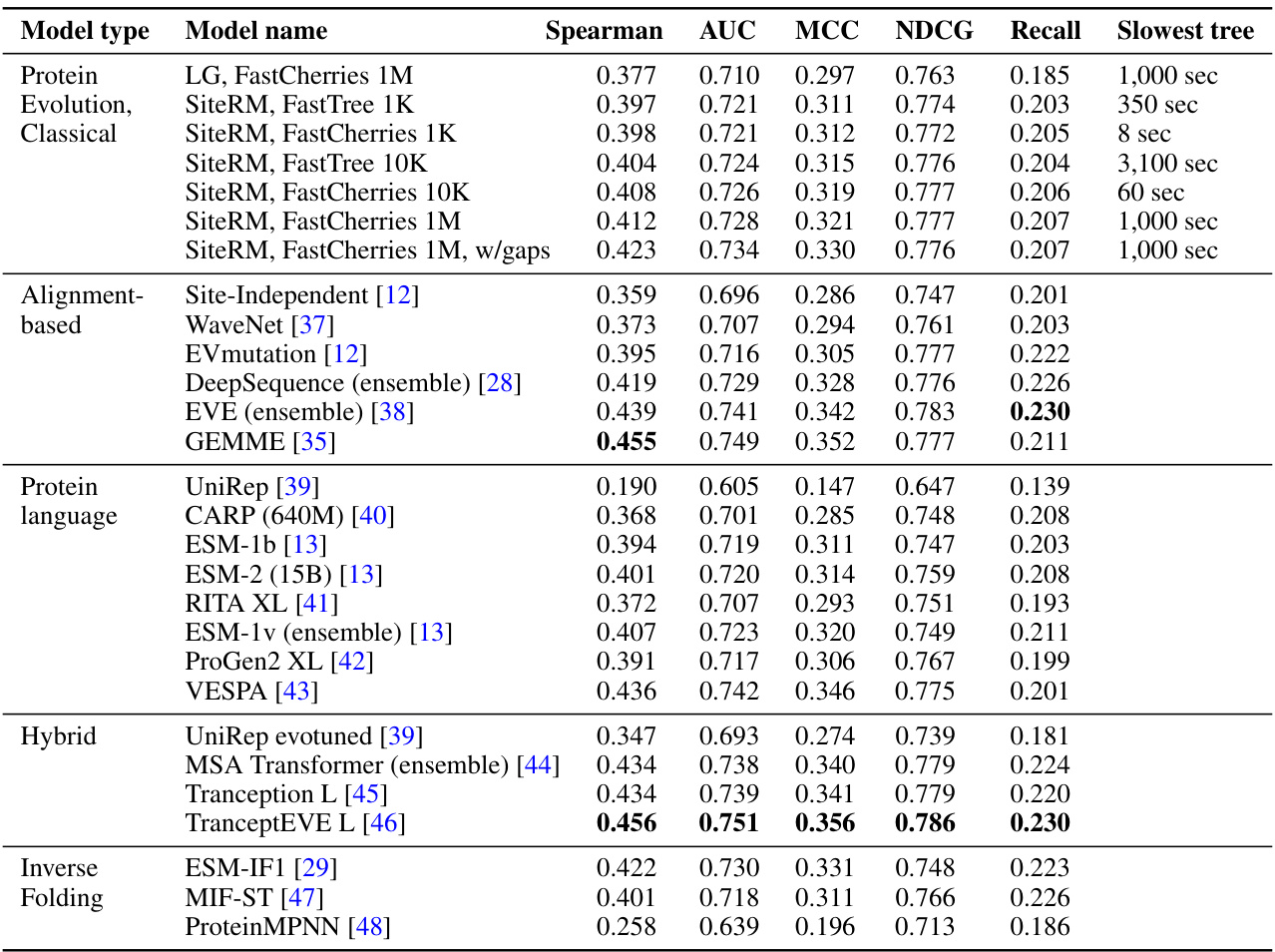

🔼 This table compares the performance of SiteRM against several other state-of-the-art models for variant effect prediction using different evaluation metrics (Spearman, AUC, MCC, NDCG, Recall). SiteRM, despite being a simpler independent-sites model, demonstrates comparable or superior performance to more complex models, highlighting its effectiveness in this task.

read the caption

Table 1: Despite being an independent-sites model, SiteRM matches or outperforms many notable models, including the large protein language model ESM-1v [13], the alignment-based epistatic models EVmutation [12] and DeepSequence [28], and the inverse-folding model ESM-IF1 [29]. Best performance among these models are shown in boldface.

In-depth insights#

Phylo-Method Speedup#

The core of this research lies in dramatically accelerating phylogenetic methods. The authors identify a critical computational bottleneck in estimating amino acid substitution rate matrices, crucial for understanding protein evolution. Their proposed solution, FastCherries, cleverly bypasses the computationally expensive phylogenetic tree reconstruction step typical in existing methods. Instead, it leverages a divide-and-conquer strategy on multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) focusing only on “cherries”, which are small, easily calculable subtrees. This novel approach, combined with the composite likelihood method (CherryML), achieves near-linear time complexity. The speedup is substantial; they demonstrate orders-of-magnitude performance gains compared to traditional methods on both simulated and real datasets, making analyses of massive datasets feasible. This enhanced scalability directly fuels their SiteRM model, which improves variant effect prediction by enabling the estimation of site-specific rate matrices. The conceptual elegance of FastCherries, simplifying a traditionally complex process, is a major contribution. Its practical impact extends across statistical phylogenetics and computational biology, opening doors to previously intractable analyses of large protein datasets.

SiteRM Variant Effects#

The heading ‘SiteRM Variant Effects’ suggests an investigation into how the SiteRM model, a novel phylogenetic method, performs in predicting the effects of genetic variations. The core idea appears to be leveraging the model’s ability to estimate site-specific rate matrices to achieve superior performance compared to other state-of-the-art methods, including large protein language models. A key aspect is the conceptual advance in probabilistic treatment of evolutionary data, allowing for effective handling of massive datasets. The results likely demonstrate that despite being an independent-sites model (meaning it doesn’t directly model interactions between sites), SiteRM surpasses complex models by conceptually modeling the evolutionary process more accurately. This success likely highlights the importance of principled probabilistic modeling over complex, data-driven approaches in tasks such as variant effect prediction. The findings suggest that SiteRM’s scalability and accuracy make it a powerful tool for variant effect prediction, offering a substantial improvement over existing methods.

Linear Time Algorithm#

A linear time algorithm, in the context of a phylogenetic analysis, would represent a significant breakthrough. Phylogenetic methods often grapple with computationally intensive tasks, especially when dealing with large datasets. A linear time algorithm would mean the computational cost scales proportionally to the input size, offering substantial speed improvements compared to algorithms with higher-order complexities. This could lead to faster inference of evolutionary trees and rate matrices, enabling analyses of significantly larger datasets, and potentially uncovering more intricate details about evolutionary processes. Achieving linear time complexity might involve clever algorithmic design such as divide-and-conquer strategies, exploiting inherent sparsity in the data, or using composite likelihood methods. However, trade-offs might exist; a linear time algorithm could sacrifice accuracy or require stronger assumptions compared to more sophisticated, but slower methods. The practical benefits of such an algorithm in fields such as variant effect prediction are immense; it would enable quicker and broader screening of mutations and improve prediction accuracy, accelerating the development of new therapies and diagnostics. Ultimately, the success of a linear-time phylogenetic method hinges on its ability to strike a balance between computational efficiency and statistical accuracy.

Model Scalability#

The study’s core contribution lies in achieving unprecedented scalability in estimating amino acid substitution rate matrices, a crucial step in phylogenetic analysis. Traditional methods struggle with large datasets, often requiring substantial computational resources and time. The authors address this limitation by introducing a novel near-linear time method, which dramatically reduces the computational burden associated with handling massive multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). This scalability is achieved through a clever combination of techniques, significantly improving the efficiency of rate matrix estimation. The enhanced scalability enables the application of these methods to previously intractable datasets, such as MSAs with millions of sequences, thus opening the door for richer, more comprehensive phylogenetic models to be built. Faster estimation also accelerates the overall pipeline, enhancing the practicality and wider applicability of phylogenetic methods in areas like variant effect prediction.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of this research paper would ideally expand upon the current work’s limitations and suggest promising avenues for future investigation. A key area would be exploring more complex, non-independent-sites models of protein evolution. The current SiteRM model, while surprisingly effective, assumes independence between sites. Relaxing this assumption, perhaps through incorporating deep learning methods or advanced statistical techniques, could significantly improve variant effect prediction accuracy. Another direction would involve investigating the use of time-irreversible models of protein evolution, a departure from the common time-reversibility assumption. This is particularly relevant given the inherent directionality of evolutionary processes. Further research could focus on enhancing the scalability of the SiteRM model for even larger datasets, potentially through optimized algorithms or distributed computing techniques. Finally, the paper could propose new applications of the method, such as phylogenetic tree reconstruction or ancestral sequence reconstruction using site-specific rate matrices. This would showcase the broader impact of the faster phylogenetic method. The effectiveness of the probabilistic treatment could also be tested on different types of variants and datasets, particularly those with less annotated information. Exploring the model’s performance against existing state-of-the-art methods in greater depth is also vital.

More visual insights#

More on figures

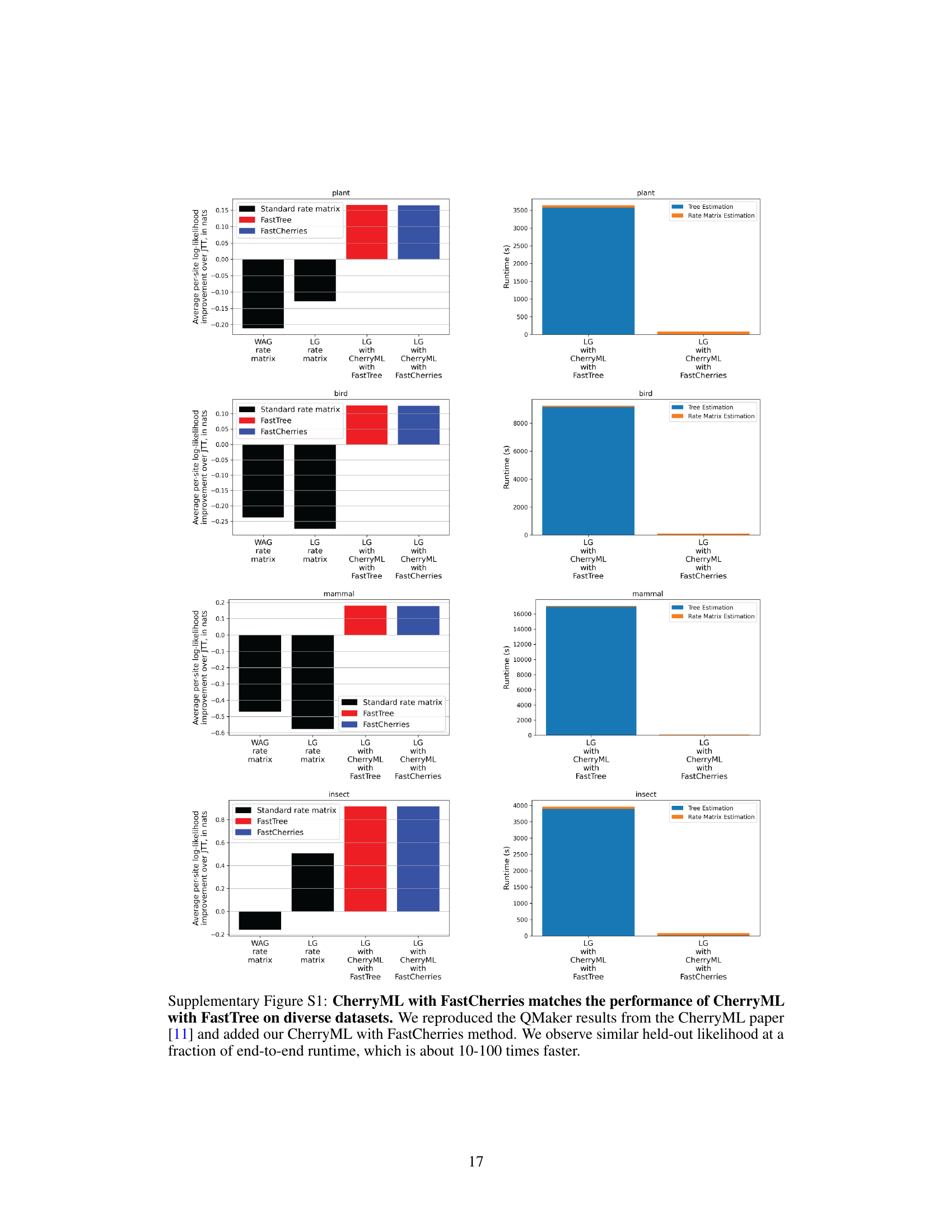

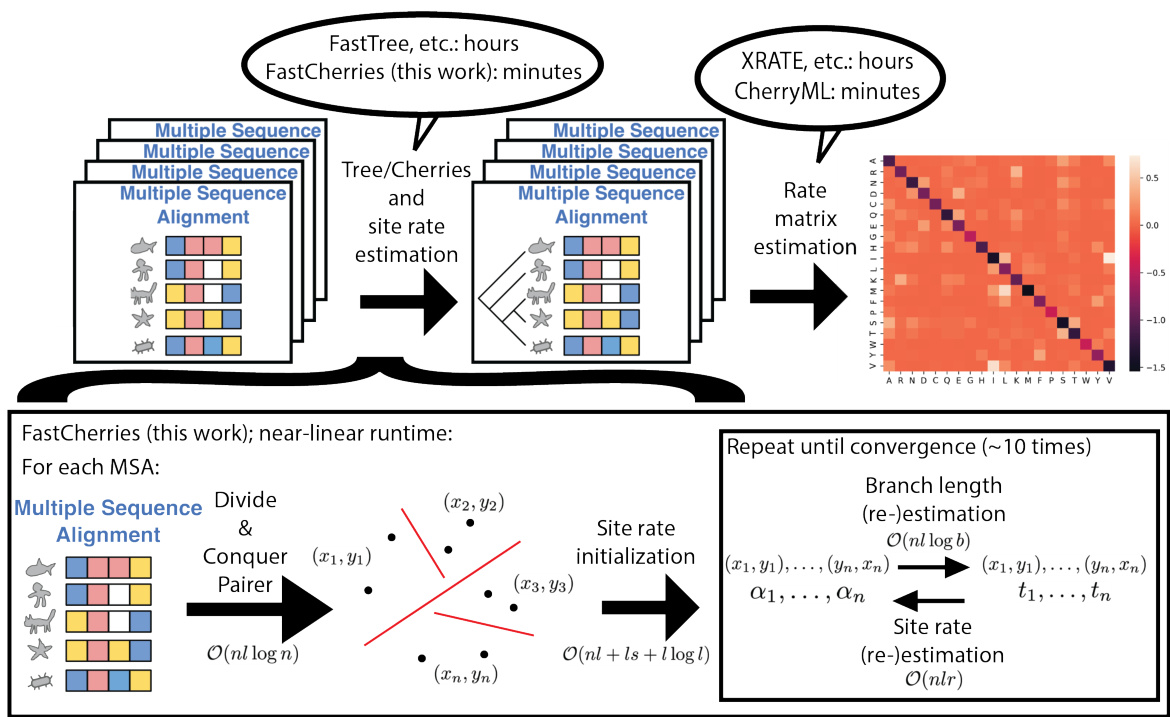

🔼 This figure compares the performance of CherryML with two different tree estimation methods (FastCherries and FastTree) and an oracle using ground truth trees. Panels (a) and (b) show the runtime and median relative error of rate matrix estimation, demonstrating the significant speed improvement of FastCherries while maintaining reasonable accuracy. Panels (c) and (d) present results on real data, showing that FastCherries achieves similar accuracy to FastTree but with a much faster runtime. The bottleneck shifts from tree estimation to rate matrix estimation in (d), highlighting the efficiency of FastCherries.

read the caption

Figure 2: CherryML with FastCherries applied to the LG model. (a) End-to-end runtime and (b) median estimation error as a function of sample size for CherryML with FastCherries vs CherryML with FastTree (as well as an oracle with ground truth trees and site rates). Practically, the loss of statistical efficiency for CherryML with FastCherries relative to FastTree or ground truth trees (which perform similarly) is ≈ 50% with a small asymptotic bias of around 2%, yet CherryML with FastCherries is two orders of magnitude faster when applied to 1,024 families. The bulk of the end-to-end runtime is taken by rate matrix estimation. The simulation setup is the same as in the CherryML paper [11]. (c) On the benchmark from the LG paper [7], CherryML with FastCherries yields similar likelihood on held-out families compared to CherryML with FastTree, while (d) shows that CherryML with FastCherries is approximately 20 times faster end-to-end than CherryLM with FastTree, with the bottleneck now being rate matrix estimation.

🔼 This figure provides a detailed schematic of the FastCherries/SiteRM method for rate matrix estimation. It illustrates the two-step process: first, a near-linear time method called FastCherries estimates the cherries in the tree and site-specific rates; second, CherryML estimates the rate matrices, achieving a significant speedup compared to traditional methods. The figure also annotates the computational complexity of each step and shows how the SiteRM model, which estimates a rate matrix per site, can be achieved with this approach.

read the caption

Figure 1: A schematic illustration of our FastCherries/SiteRM method. Rate matrix estimation from a set of MSAs classically proceeds in two steps: tree estimation, followed by rate matrix estimation. The recently proposed CherryML method [11] significantly speeds up the rate matrix estimation step. Since CherryML only requires the cherries in the trees, we propose FastCherries, a new near-linear method that estimates only the cherries in the tree (as well as the site rates) rather than the whole tree. FastCherries proceeds in two steps: a divide-and-conquer pairing step based on Hamming distance, followed by site rate and branch length estimation. Site rate and branch length estimation alternate until convergence. CherryML's speed allows estimating not only a single global rate matrix, but also one rate matrix per site, which we call the SiteRM model. In this schematic, computational complexities for each step of FastCherries is annotated at each step; n = number of sequences in the MSA, l = number of sites in the MSA, s = number of states (e.g., 20 for amino acids), r = number of site rate categories of the LG model (e.g., 4 or 20 is typical), b = number of quantization points used to quantize time by CherryML. Precomputation of the matrix exponentials which is shared across all MSAs is excluded from the schematic and costs O(rbs³). MSA illustrations adapted from [23].

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of CherryML with the newly developed FastCherries method compared to the original CherryML with FastTree, as well as an oracle using true trees and site rates, across various aspects. Panels (a) and (b) show the runtime and accuracy of rate matrix estimation, respectively, as functions of the number of protein families used in the simulation. Panel (c) compares the average per-site AIC improvement over the JTT model for the various methods. Finally, panel (d) compares the runtimes of the complete workflow for the different methods using a benchmark dataset from the LG paper, showcasing a significant speed improvement from using FastCherries.

read the caption

Figure 2: CherryML with FastCherries applied to the LG model. (a) End-to-end runtime and (b) median estimation error as a function of sample size for CherryML with FastCherries vs CherryML with FastTree (as well as an oracle with ground truth trees and site rates). Practically, the loss of statistical efficiency for CherryML with FastCherries relative to FastTree or ground truth trees (which perform similarly) is ≈ 50% with a small asymptotic bias of around 2%, yet CherryML with FastCherries is two orders of magnitude faster when applied to 1,024 families. The bulk of the end-to-end runtime is taken by rate matrix estimation. The simulation setup is the same as in the CherryML paper [11]. (c) On the benchmark from the LG paper [7], CherryML with FastCherries yields similar likelihood on held-out families compared to CherryML with FastTree, while (d) shows that CherryML with FastCherries is approximately 20 times faster end-to-end than CherryLM with FastTree, with the bottleneck now being rate matrix estimation.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of SiteRM model against several other notable models for variant effect prediction. It shows that SiteRM, despite its simplicity as an independent-sites model, achieves comparable or better results than more complex models like large language models (ESM-1v), alignment-based epistatic models (EVmutation, DeepSequence), and inverse-folding models (ESM-IF1). The metrics used for comparison include Spearman correlation, AUC, MCC, NDCG, and Recall. The best-performing model for each metric is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Despite being an independent-sites model, SiteRM matches or outperforms many notable models, including the large protein language model ESM-1v [13], the alignment-based epistatic models EVmutation [12] and DeepSequence [28], and the inverse-folding model ESM-IF1 [29]. Best performance among these models are shown in boldface.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of the SiteRM model against other state-of-the-art models for variant effect prediction. The models are evaluated based on several metrics, including Spearman correlation, AUC, MCC, NDCG, and recall. SiteRM, despite its simplicity as an independent-sites model, achieves comparable or superior performance to more complex models, highlighting the effectiveness of its probabilistic approach.

read the caption

Table 1: Despite being an independent-sites model, SiteRM matches or outperforms many notable models, including the large protein language model ESM-1v [13], the alignment-based epistatic models EVmutation [12] and DeepSequence [28], and the inverse-folding model ESM-IF1 [29]. Best performance among these models are shown in boldface.

Full paper#