TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are powerful but resource-intensive. Current compression techniques primarily focus on model weights, often causing accuracy loss or hindering efficient retraining. This paper addresses these limitations.

The proposed method, ESPACE, tackles LLM compression by directly reducing the dimensionality of activations. By projecting activations onto a pre-calibrated set of principal components, ESPACE achieves significant compression (up to 50%) with minimal accuracy degradation. The method also leads to faster inference times and efficient retraining. This activation-centric approach demonstrates a promising new direction in LLM compression, surpassing existing weight-based methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on LLM compression due to its novel approach. It introduces ESPACE, a method focusing on activation dimensionality reduction, a less-explored area offering potential for significant improvements in model size and inference speed. This contrasts with existing weight-centric methods, addressing limitations in expressivity and retraining difficulties. The theoretical foundation and empirical results open avenues for further research in activation-centric compression techniques and their combination with other compression methods.

Visual Insights#

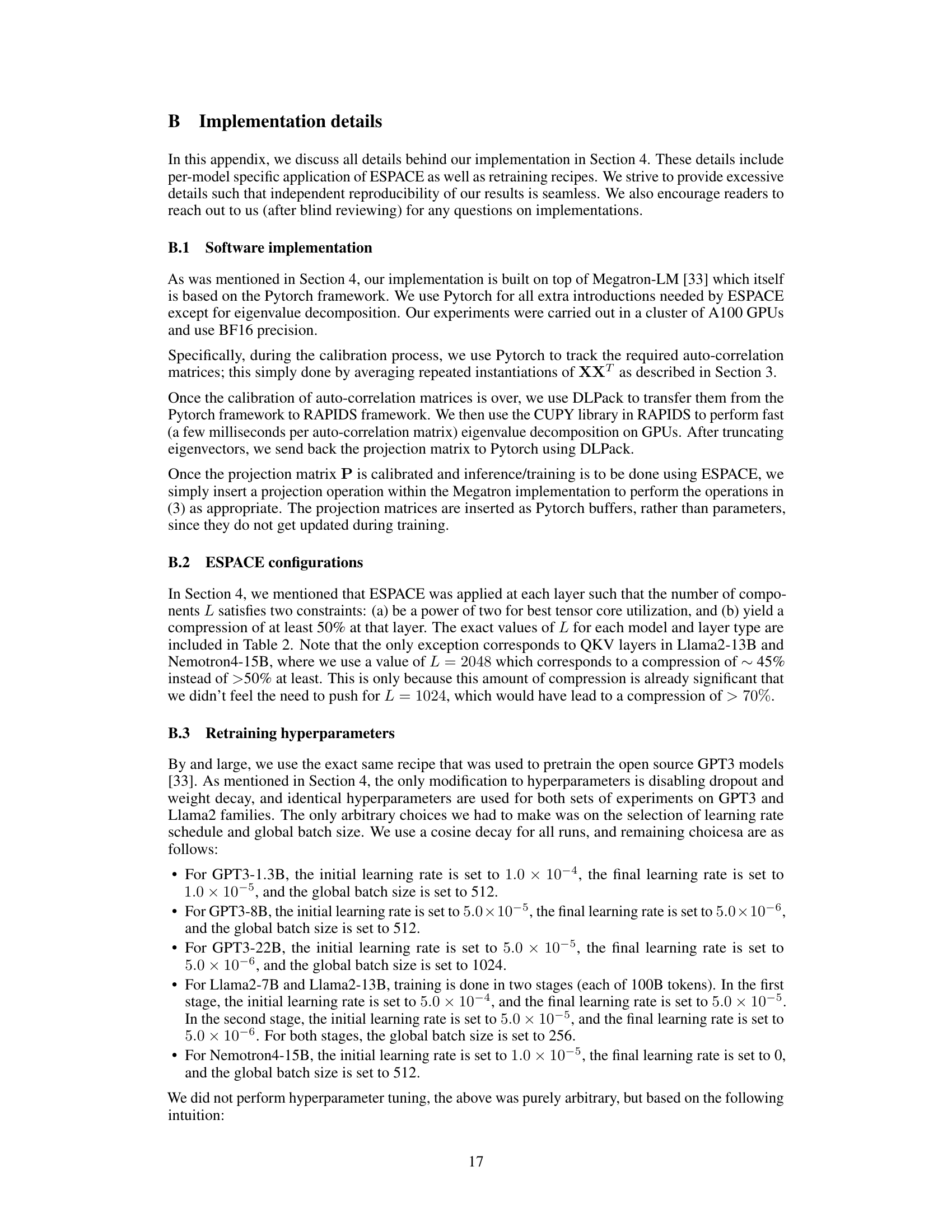

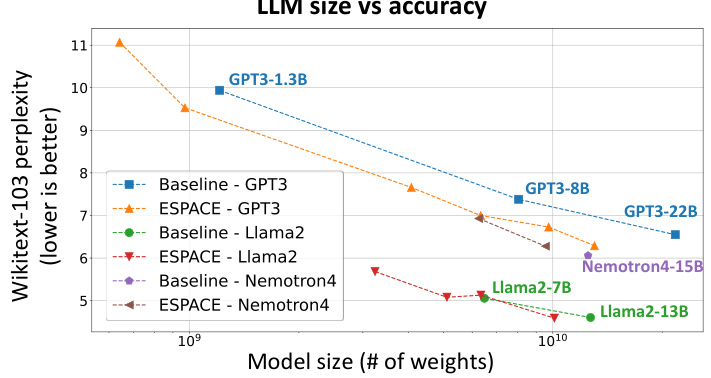

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between model size (number of weights) and perplexity (a measure of how well a language model predicts a text) for several large language models (LLMs). The baseline perplexity for GPT3 and Llama2 models of different sizes are plotted. Importantly, it shows how the perplexity changes when these models are compressed using the ESPACE technique. Lower perplexity values indicate better performance. The results show that ESPACE achieves a significant reduction in model size while maintaining relatively good accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 1: Perplexity² versus model size for GPT3 and Llama2 models and comparison to compressed models using ESPACE.

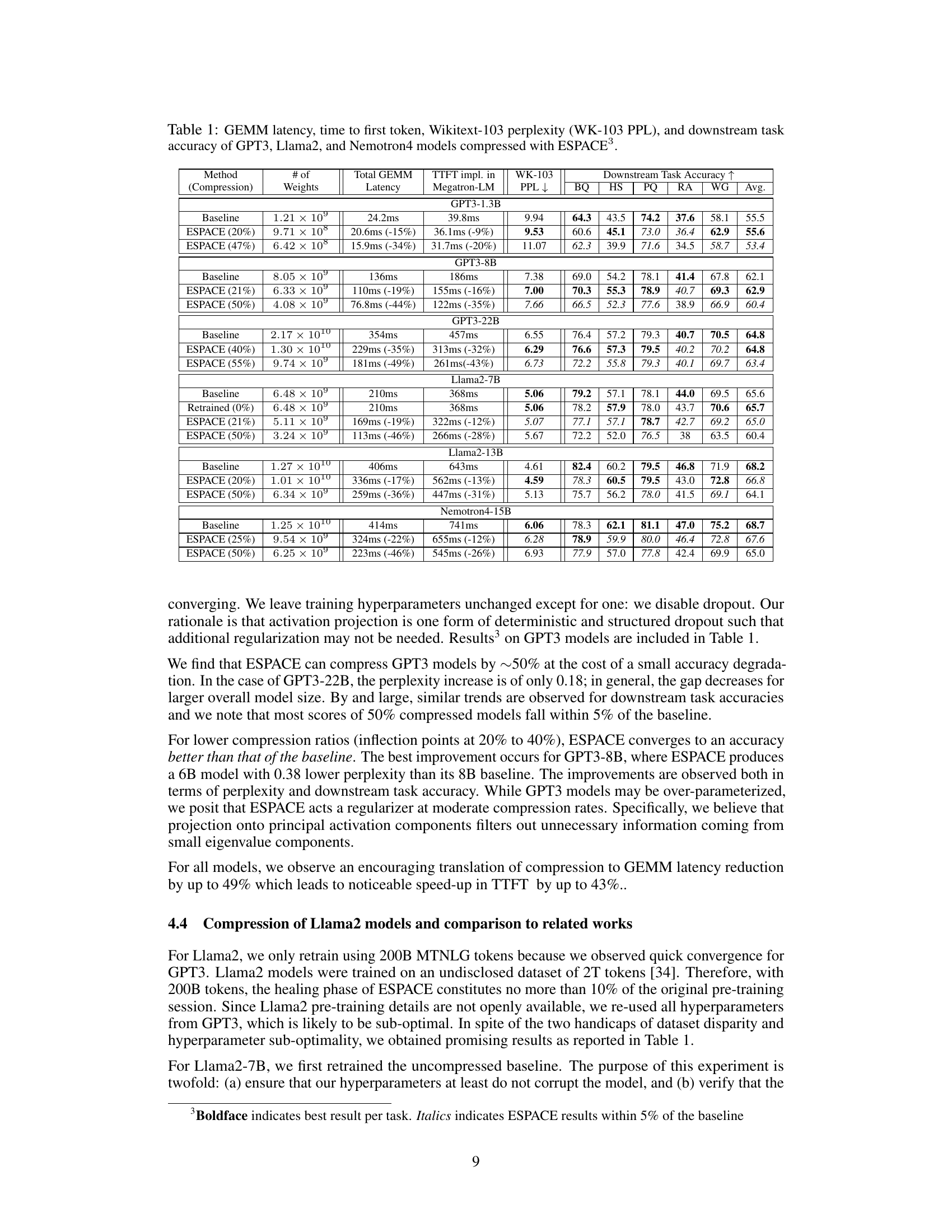

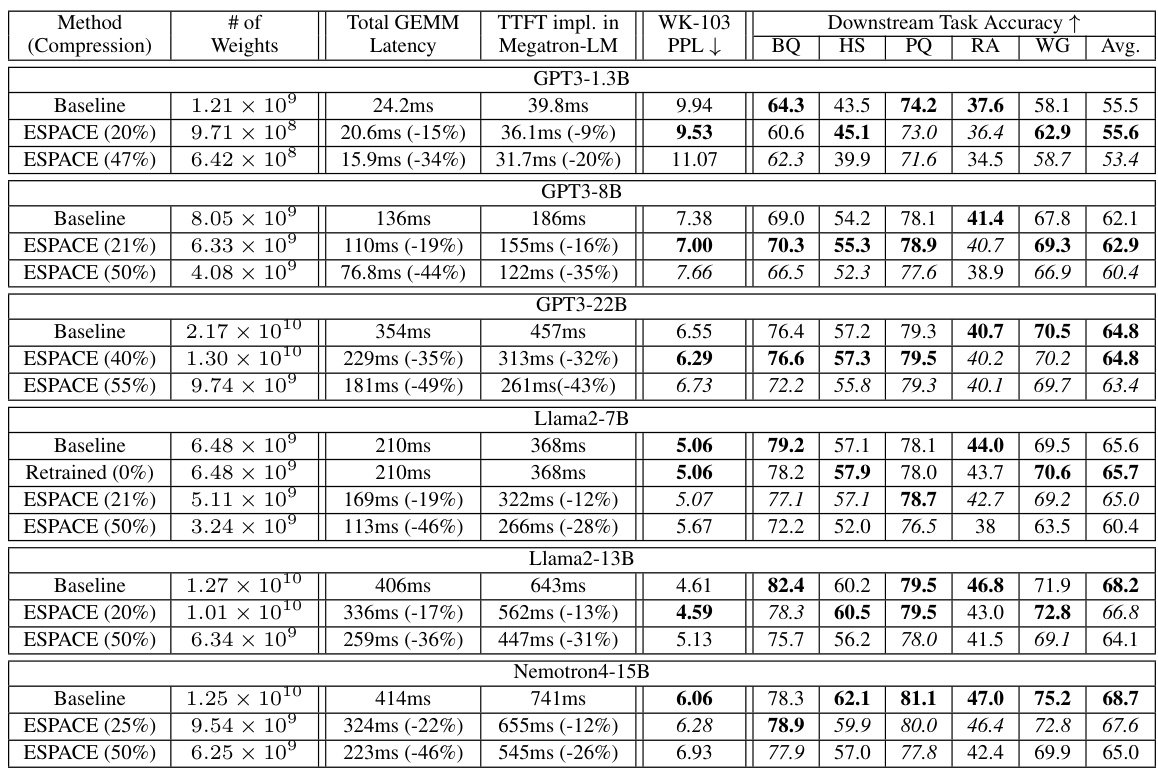

🔼 This table presents the results of the model compression experiments using ESPACE. It compares the baseline performance (without compression) to models compressed using ESPACE at different compression rates (20%, 47%, etc.). For each model and compression rate, it provides the number of weights, total GEMM latency, time to first token (TTFT) latency, Wikitext-103 perplexity, and downstream task accuracy across several benchmark tasks (BoolQ, HellaSwag, PIQA, RACE, and WinoGrande). The table shows the impact of ESPACE on both model size and inference speed.

read the caption

Table 1: GEMM latency, time to first token, Wikitext-103 perplexity (WK-103 PPL), and downstream task accuracy of GPT3, Llama2, and Nemotron4 models compressed with ESPACE.

In-depth insights#

Activation-Centric LLM#

The concept of an “Activation-Centric LLM” offers a compelling alternative to traditional weight-centric approaches in large language model (LLM) compression. Instead of focusing solely on optimizing the model’s weights (parameters), this approach prioritizes the dimensionality reduction of activations—the intermediate computational results generated during inference. This shift is significant because activations often exhibit inherent redundancies, especially within the high-dimensional spaces characteristic of LLMs. By projecting activations onto a lower-dimensional subspace using a pre-trained projection matrix, this method can effectively reduce the computational burden during inference without sacrificing expressive power, as weight matrices remain intact during training. This technique provides a promising method for compression, as it leverages matrix multiplication associativity to achieve compression as a byproduct. Moreover, an activation-centric approach offers theoretical advantages in preventing the loss of expressivity that often accompanies weight-based compression techniques. However, challenges remain, such as the optimal calibration of the projection matrix and the trade-off between compression rates and potential accuracy degradation. Further research is needed to explore the full potential of activation-centric LLMs, especially in combination with other compression techniques like quantization and pruning.

ESPACE: Projection#

The heading ‘ESPACE: Projection’ suggests a section detailing the core mechanism of the ESPACE model, focusing on how it projects activation tensors. This projection is crucial for dimensionality reduction, a key aspect of model compression. The method likely involves a learned or pre-computed projection matrix that maps high-dimensional activations to a lower-dimensional subspace. A thoughtful exploration of this section would investigate the properties of this projection matrix – is it learned during training or fixed beforehand? What criteria are used to optimize the projection (e.g., minimizing information loss, preserving crucial information)? Understanding the projection’s effect on model accuracy and computational cost is essential. The discussion might compare ESPACE’s projection approach to other dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA, SVD) emphasizing the novelty and advantages of ESPACE’s method. Theoretical analysis and empirical results demonstrating the effectiveness of the projection in compressing models while maintaining accuracy would be central to this section. Therefore, a deep dive into ‘ESPACE: Projection’ would reveal how it achieves the critical balance between model size and performance.

Compression Metrics#

To effectively evaluate model compression techniques, a robust and comprehensive set of compression metrics is crucial. Beyond simply measuring the reduction in model size (e.g., number of parameters or weights), it’s vital to assess the impact on model performance. This necessitates evaluating metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, perplexity (for language models), BLEU score (for machine translation), or other task-specific metrics appropriate to the model’s application. The trade-off between compression rate and performance degradation must be carefully analyzed, considering factors like the computational cost of the compressed model at inference time, memory footprint, and latency. A holistic evaluation should incorporate both objective metrics and subjective assessments, potentially including user studies to gauge the perceived quality of the compressed model’s output. Furthermore, the robustness of the compressed model to noise and variations in input data should be evaluated, ensuring the compressed model’s reliability across diverse conditions. Finally, the energy efficiency of the compressed model should be considered, as reducing power consumption is a key driver for model compression in many applications.

Empirical Results#

An empirical results section in a research paper should meticulously document the experiments conducted, focusing on clarity and reproducibility. Quantitative results should be presented clearly, possibly using tables and figures, and should include measures of statistical significance to ensure the findings’ robustness. Detailed methodology, including data sets used, experimental design, evaluation metrics, and hyperparameter settings, should be described to allow readers to assess the validity and understand the limitations of the study. Furthermore, a discussion of the results is critical; the authors should analyze the results in relation to their hypotheses and existing literature. Comparisons with existing methods or baselines are vital, highlighting both strengths and weaknesses of the proposed approach. Finally, a thoughtful explanation of any unexpected or counter-intuitive results should be included, and potential sources of error or bias should be acknowledged. A strong empirical results section enhances a paper’s credibility and impact significantly.

Future of Compression#

The future of LLM compression hinges on addressing the limitations of current techniques. Weight-centric methods, while effective, often hinder model expressivity due to parameter reduction. Activation-centric approaches, like the ESPACE method discussed in the provided research, offer a promising alternative by reducing the dimensionality of activations without directly modifying the weights, preserving expressivity during training. However, they require careful calibration and projection matrix optimization to minimize accuracy loss. Future research should explore hybrid methods that combine weight and activation compression techniques, potentially leveraging the strengths of each to achieve greater compression rates with minimal or even improved accuracy. Furthermore, advances in hardware acceleration and specialized architectures could significantly impact the feasibility and efficiency of various compression techniques. Investigating memory-efficient implementations and exploring different decomposition methods beyond traditional SVD, such as those leveraging sparsity, is crucial. Finally, a deeper understanding of the relationship between activation redundancy and model expressivity is needed to guide the design of more sophisticated and effective compression algorithms. Addressing inherent noise introduced by compression methods and their cumulative effect across multiple layers is also critical for ensuring reliable performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates three different GEMM (General Matrix Multiplication) decompositions. (a) shows a standard GEMM where the weight matrix and activation tensor are directly multiplied. (b) demonstrates weight decomposition using truncated SVD, where the weight matrix is approximated by the product of two smaller matrices, reducing the number of parameters but potentially sacrificing accuracy. (c) presents the ESPACE method, which inserts a static projection matrix before the activation tensor. This projection reduces the dimensionality of the activations, enabling compression at inference time without affecting the weight matrix during training. The pre-computed product of the projection and weight matrices is used for inference, leading to efficient model compression.

read the caption

Figure 2: Decompositions in GEMMs: (a) baseline multiplication of weight matrix and activation tensor, (b) truncated SVD on the weight matrix, and (c) proposed approach of inserting a static matrix to project activations. With ESPACE, all weights are available for training, while inference compression is achieved via per-computation of (PTW).

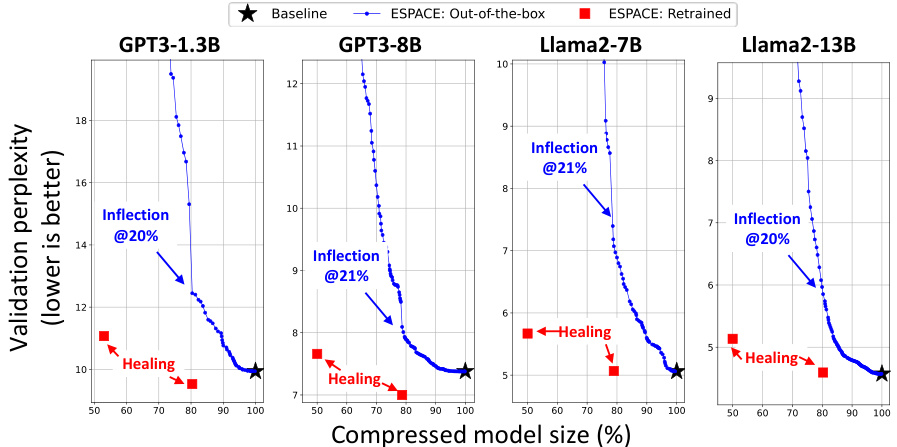

🔼 This figure shows the validation perplexity of GPT3-22B as ESPACE is progressively applied to its GEMM layers. The x-axis represents the compressed model size as a percentage of the original size. The y-axis is the validation perplexity. The black star represents the baseline perplexity. The blue line shows the perplexity when ESPACE is applied without retraining (out-of-the-box). The red squares show the perplexity after retraining the compressed model. The figure highlights that out-of-the-box compression is nearly lossless up to around 20%. After 40% compression, there is a sharp increase in perplexity, but retraining improves the accuracy, thus achieving a healing process. The order in which the layers are compressed is determined by a layer-wise sensitivity analysis.

read the caption

Figure 3: Validation perplexity for GPT3-22B when ESPACE is progressively applied to its GEMM layers. The order of layer selection is based on a layer-wise sensitivity analysis.

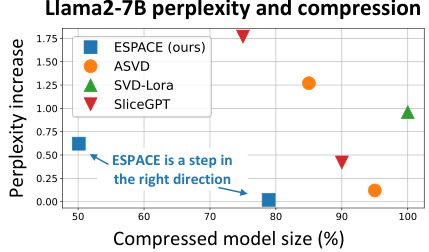

🔼 This figure compares the performance of ESPACE to three other methods for compressing the Llama2-7B language model: ASVD, SVD-LoRa, and SliceGPT. The y-axis represents the increase in perplexity compared to the baseline uncompressed model, while the x-axis shows the percentage of model size retained after compression. The graph shows that ESPACE achieves a lower perplexity increase at various compression rates compared to the other three methods, suggesting that ESPACE is an improvement in activation-centric tensor decomposition compression.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison to related works compressing Llama2-7B using matrix factorization techniques.

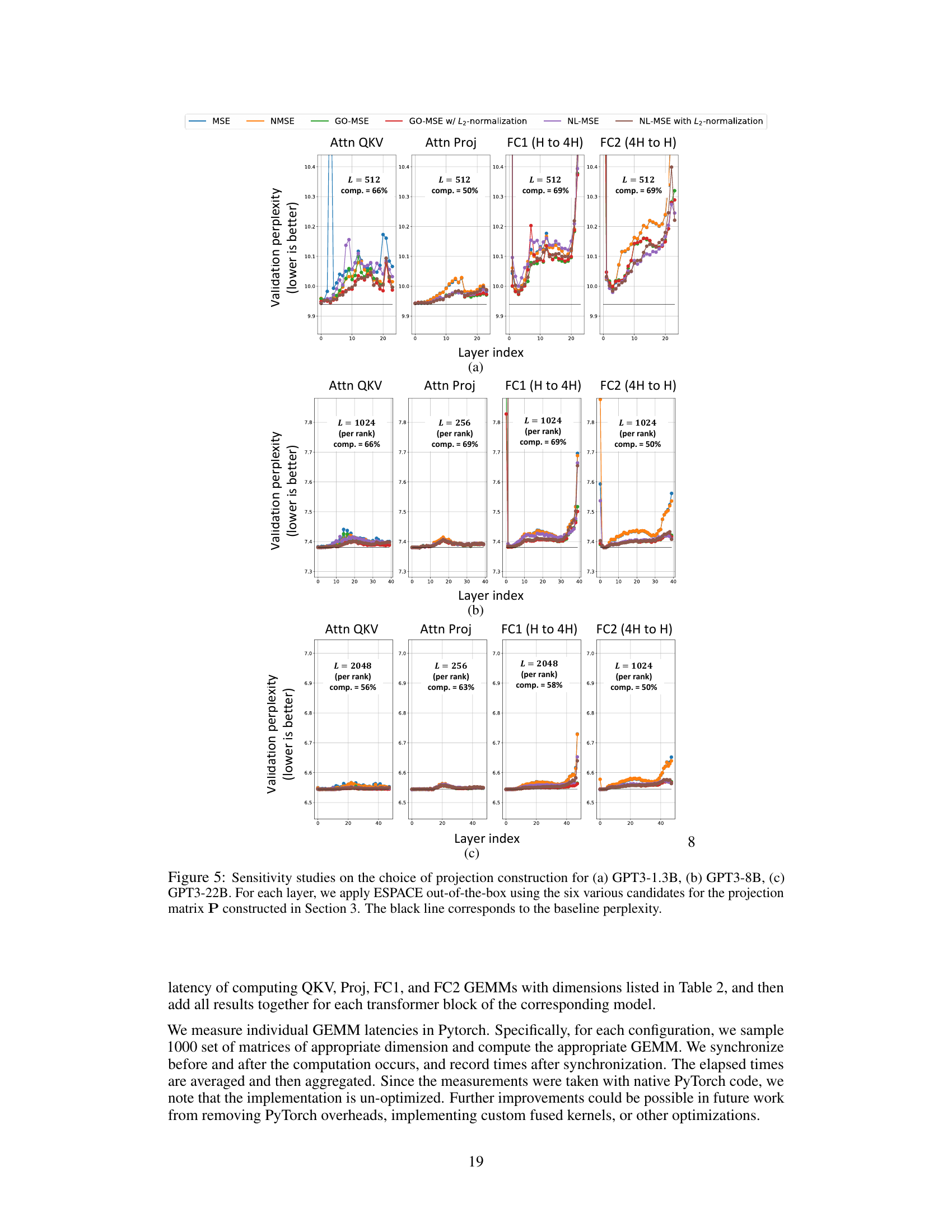

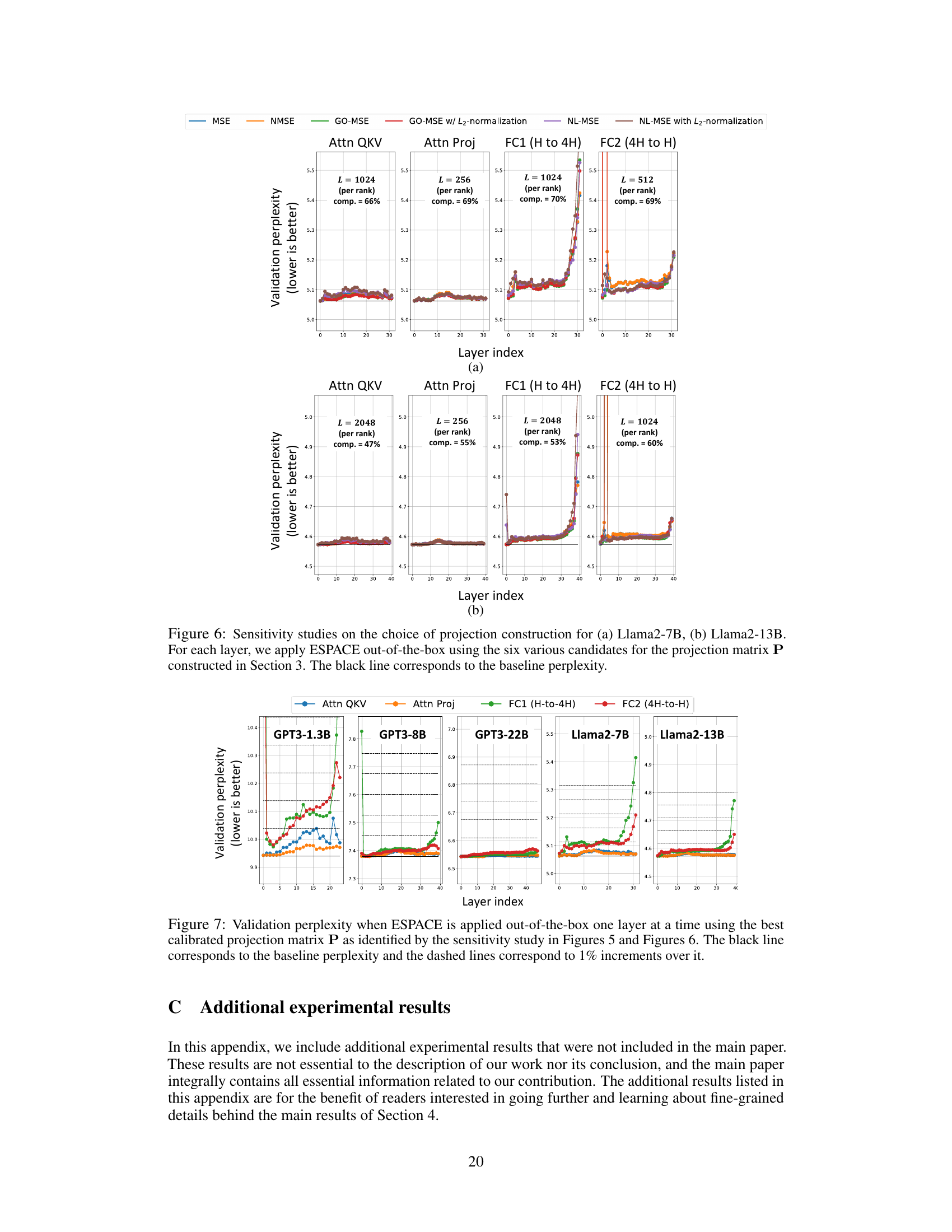

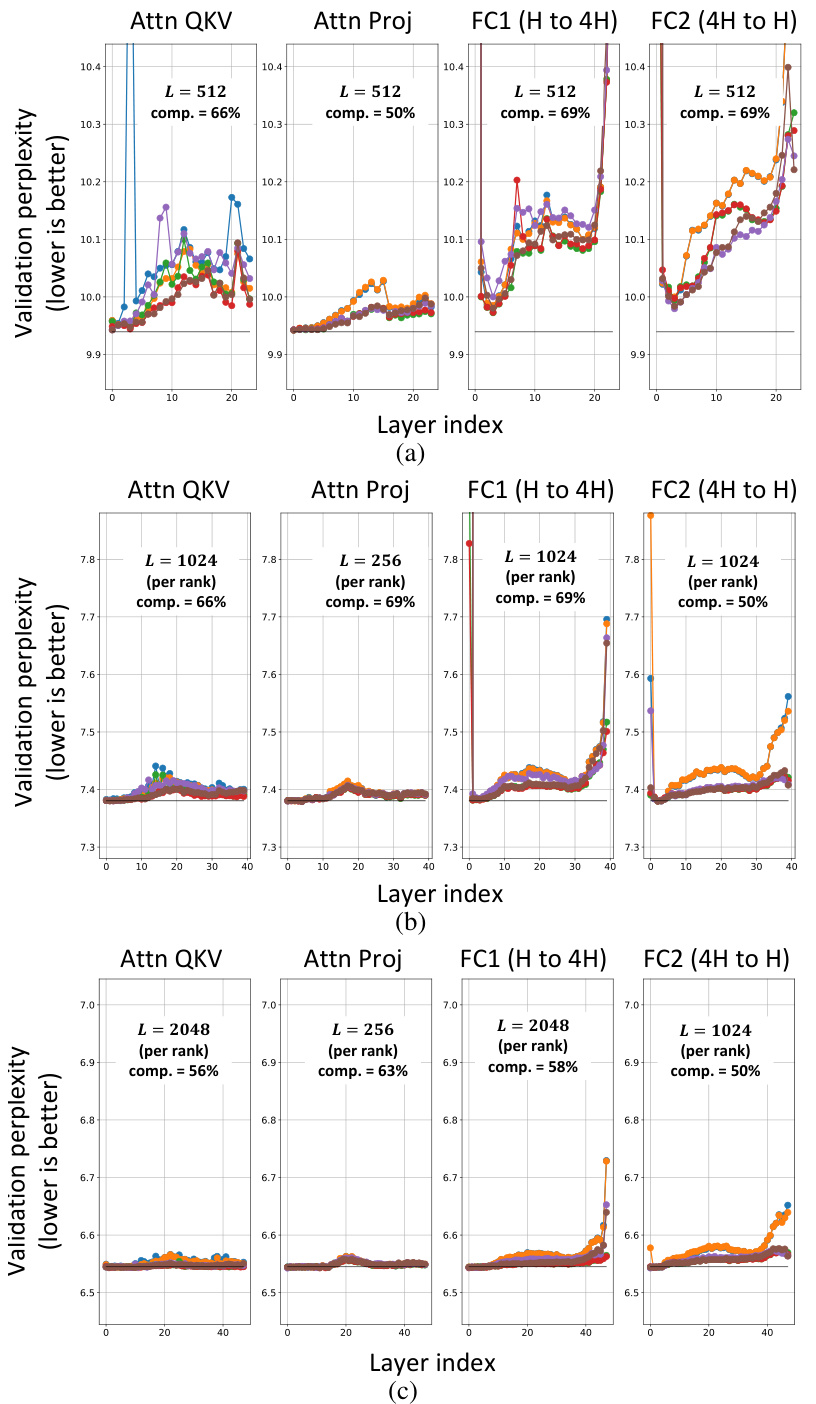

🔼 This figure shows the results of sensitivity analysis on the choice of projection matrix P for constructing ESPACE. Six different methods for constructing P, each optimizing a different metric (MSE, NMSE, GO-MSE, GO-MSE with L2 normalization, NL-MSE, NL-MSE with L2 normalization), were tested on three different GPT-3 models (1.3B, 8B, and 22B parameters). For each layer in the model, ESPACE was applied out-of-the-box using each of the six projection matrices. The resulting validation perplexities are plotted for each layer and each method. The black line in each plot represents the baseline perplexity without ESPACE.

read the caption

Figure 5: Sensitivity studies on the choice of projection construction for (a) GPT3-1.3B, (b) GPT3-8B, (c) GPT3-22B. For each layer, we apply ESPACE out-of-the-box using the six various candidates for the projection matrix P constructed in Section 3. The black line corresponds to the baseline perplexity.

🔼 This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of different projection matrix P constructions on the validation perplexity for three different GPT-3 models with different sizes. For each layer in each model, ESPACE is applied out-of-the-box using six different projection matrices and the validation perplexity is measured. The results are presented in three subfigures for GPT-3 1.3B, 8B, and 22B, respectively. Each subfigure displays the validation perplexity for each layer with different choices of projection matrices using different metrics. The black line indicates the baseline perplexity.

read the caption

Figure 5: Sensitivity studies on the choice of projection construction for (a) GPT3-1.3B, (b) GPT3-8B, (c) GPT3-22B. For each layer, we apply ESPACE out-of-the-box using the six various candidates for the projection matrix P constructed in Section 3. The black line corresponds to the baseline perplexity.

🔼 This figure shows the validation perplexity of the GPT3-22B model as the ESPACE compression technique is progressively applied to its GEMM (general matrix multiplication) layers. The layers were added sequentially, starting with the ones that caused the least increase in perplexity when compressed individually. The x-axis represents the percentage of the model’s layers compressed, and the y-axis represents the validation perplexity. The figure helps to show the relationship between compression rate and accuracy degradation.

read the caption

Figure 3: Validation perplexity for GPT3-22B when ESPACE is progressively applied to its GEMM layers. The order of layer selection is based on a layer-wise sensitivity analysis.

🔼 This figure shows the results of progressively applying ESPACE to the layers of four different LLMs (GPT3-1.3B, GPT3-8B, Llama2-7B, and Llama2-13B) without retraining. The layers are ordered from least to most impactful on validation perplexity, as determined by a separate sensitivity analysis (Figure 7). The graph plots validation perplexity against the compressed model size (%). The black star represents the baseline perplexity of the uncompressed model. The blue line shows the perplexity when ESPACE is applied out-of-the-box, and the red squares show the perplexity after retraining the compressed model. The figure highlights an inflection point where accuracy degradation accelerates (around 20% for GPT3 and Llama2), and a ‘healing’ phase following retraining where performance improves.

read the caption

Figure 8: Progressive out-of-the-box application of ESPACE on GPT3-{1.3B, 8B} and Llama2-{7B, 13B}. The plot for GPT3-22B was provided in the main text in Figure 3. The progressive application of ESPACE is based on the ranking of layers from least to most destructive based on validation perplexity sensistivity in Figure 7.

Full paper#