↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Smart contracts, automated programs handling financial transactions, are vulnerable to bugs, especially “accounting bugs” (errors in financial models) which are costly and hard to find. Existing methods struggle with generalization, hallucinations, and limited context.

This research introduces ABAUDITOR, a hybrid system combining LLMs (for financial meaning annotation) and rule-based reasoning (for operation validation). ABAUDITOR uses a feedback loop to address LLM hallucinations. Experiments on real-world projects demonstrate its effectiveness: achieving 75.6% accuracy in labeling financial meanings, 90.5% recall in detecting bugs, and discovering both known and unknown bugs in recent projects. ABAUDITOR provides a more robust and accurate approach to smart contract security.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on smart contract security and vulnerability detection. It presents a novel hybrid approach combining LLMs and rule-based reasoning, a significant advancement over existing methods. The findings on real-world projects and the discovery of zero-day bugs highlight the practical impact of this work and open new avenues for research into more robust and efficient bug detection techniques. The demonstration of improved accuracy and recall in accounting bug detection is particularly important, addressing a significant challenge in the field.

Visual Insights#

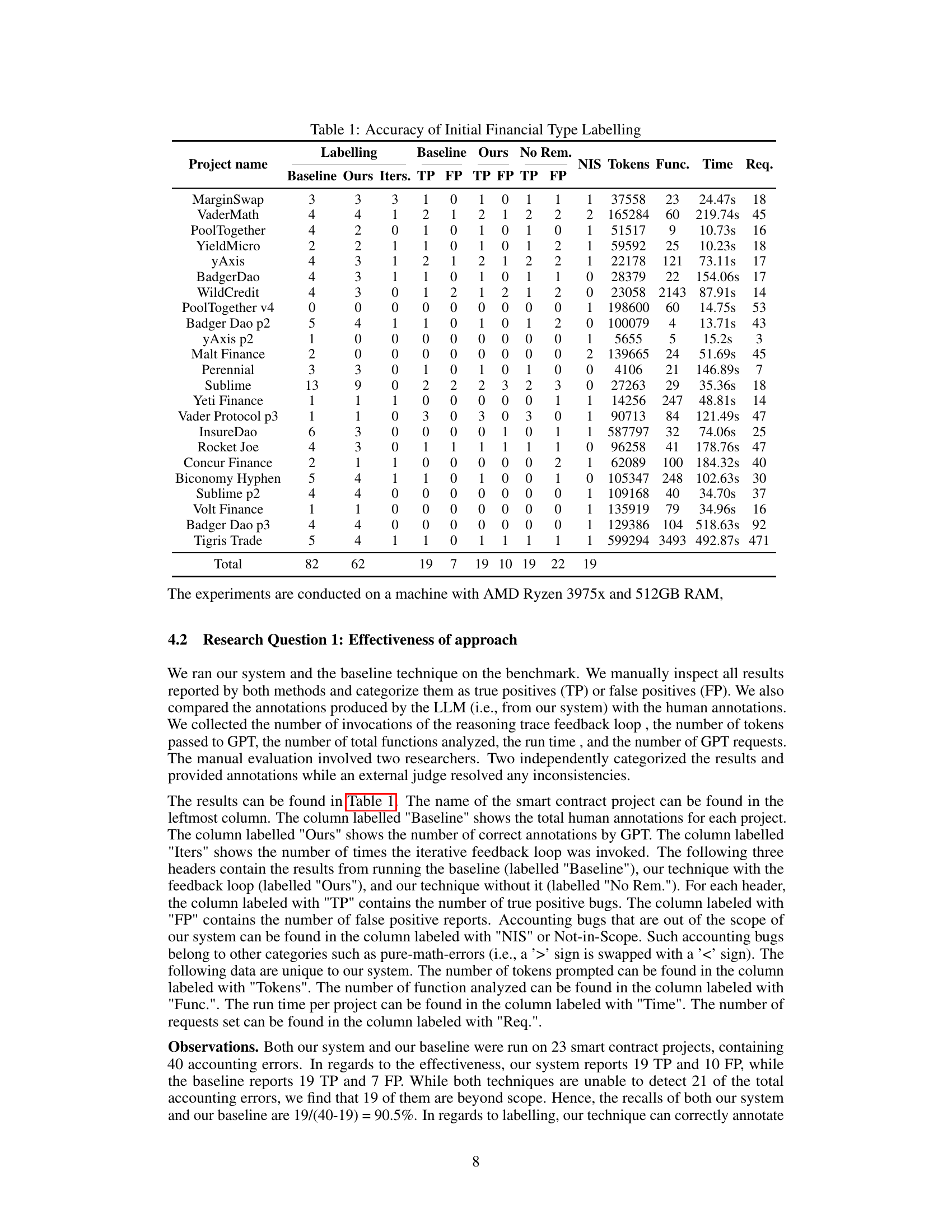

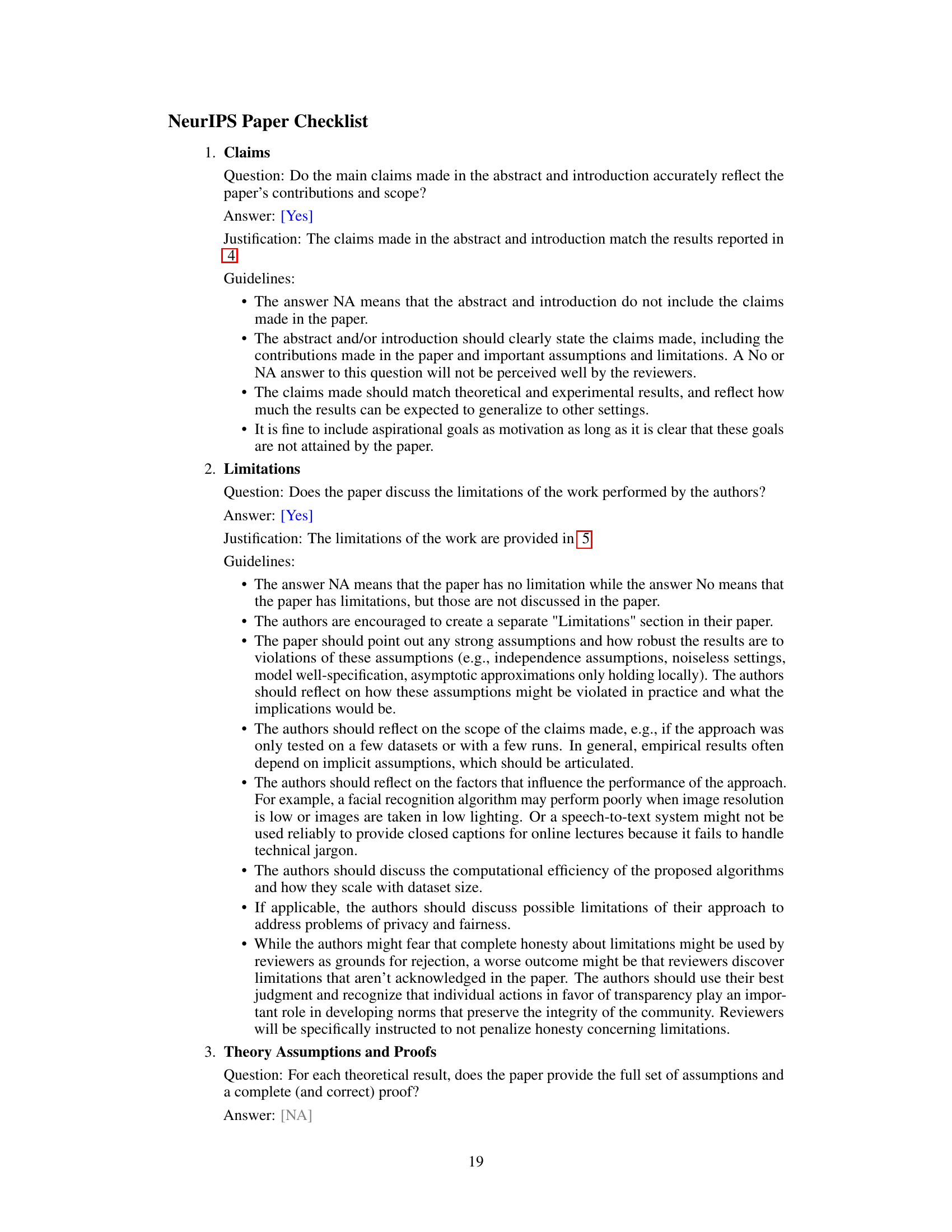

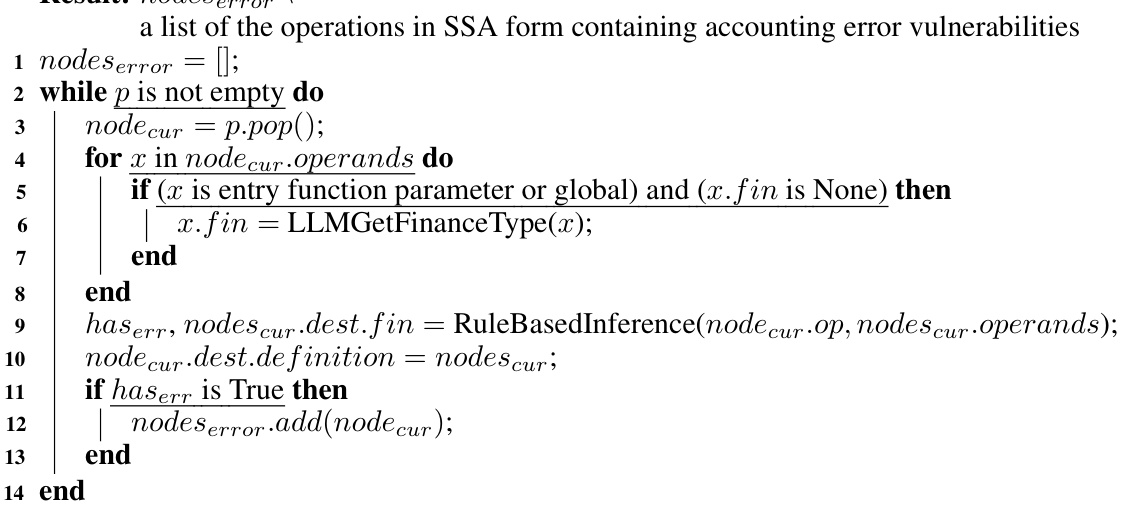

The figure illustrates the architecture of ABAUDITOR, a hybrid LLM and rule-based reasoning system for detecting accounting errors in smart contracts. It starts with a smart contract as input, which is preprocessed by converting it into Static Single Assignment (SSA) form. The preprocessor then identifies entry functions. The parameters and global variables of these entry functions are then annotated with their financial meanings using an LLM. Rule-based reasoning is then used to propagate these meanings through the contract’s logic. A validation and hallucination remedy step, using a trace generated from the rule-based reasoning, is used to filter out incorrect annotations (hallucinations) produced by the LLM. This process results in a list of potential accounting error vulnerabilities, which are further refined to identify the final accounting error vulnerabilities.

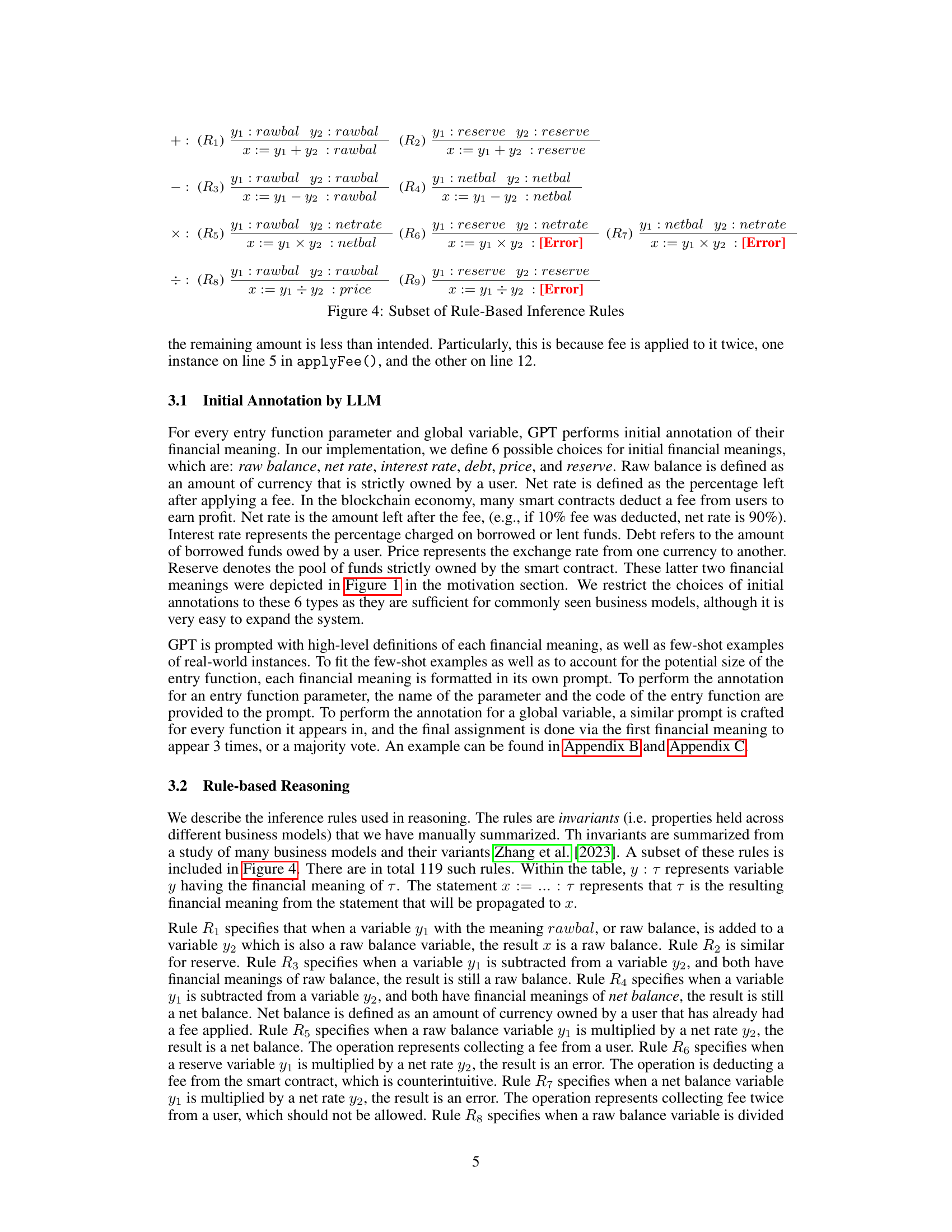

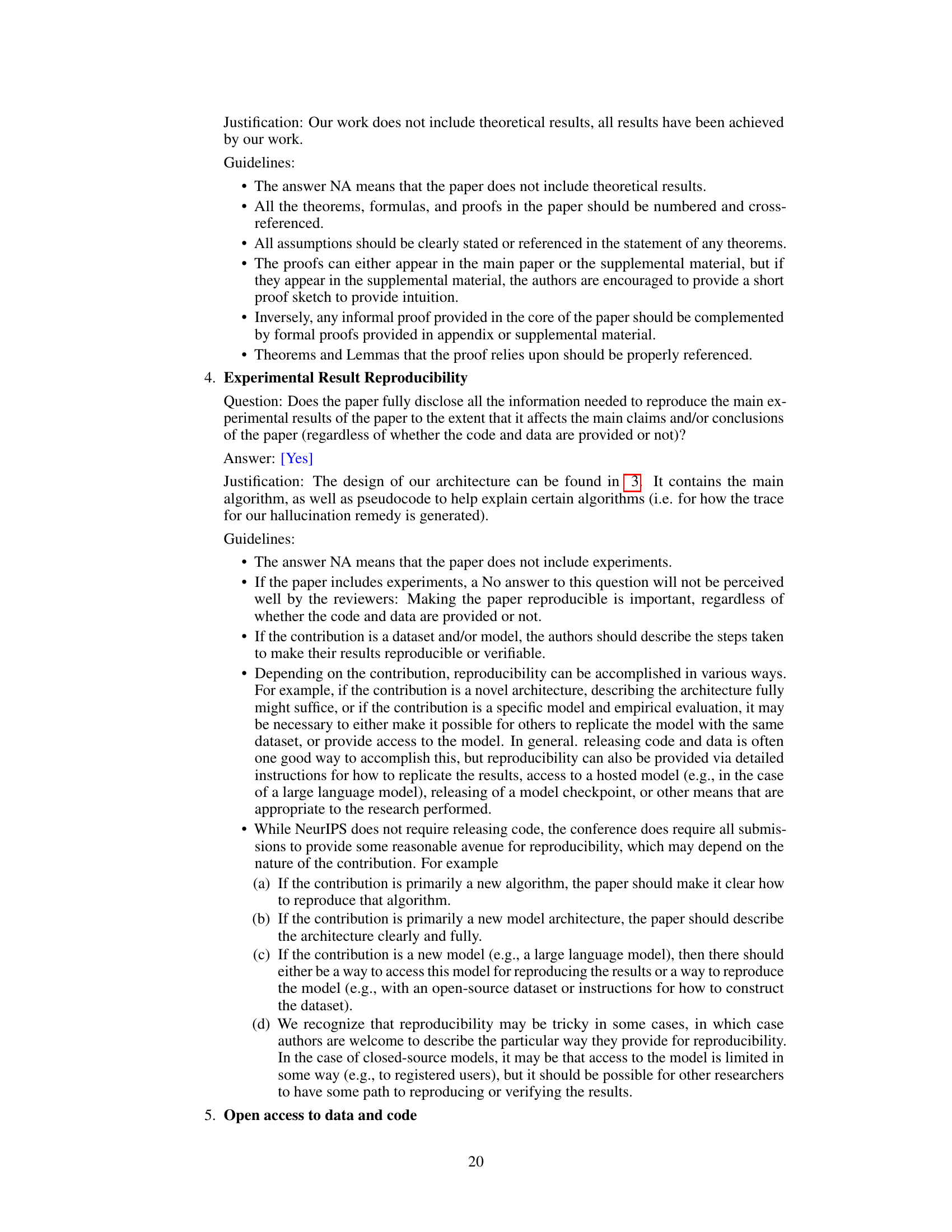

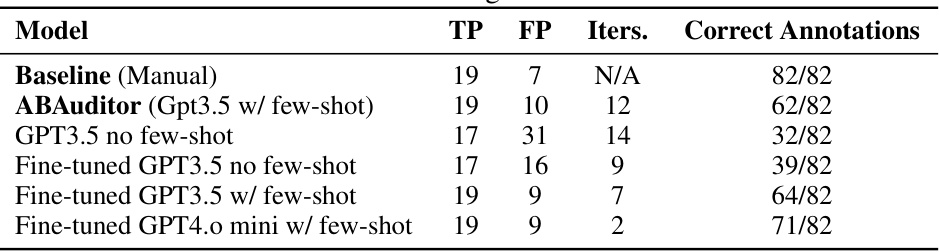

This table presents the accuracy of initial financial type labeling for various smart contract projects. It compares the accuracy of human labeling (Baseline) against the LLM’s labeling (Ours) with and without hallucination reduction. The table also shows the number of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN) for each method. Additional columns provide details on the number of iterations (Iters), non-in-scope (NIS) accounting bugs, tokens used, number of functions analyzed (Func.), run time, and the number of requests.

In-depth insights#

LLM-Rule Hybrid#

An LLM-Rule Hybrid system for smart contract vulnerability detection offers a compelling approach by combining the strengths of Large Language Models (LLMs) and rule-based reasoning. LLMs excel at understanding the context and semantics of code, enabling them to effectively annotate financial meanings of variables. This capability is crucial for identifying accounting errors, a particularly challenging class of vulnerabilities. However, LLMs can be prone to hallucinations and generalization issues. Rule-based systems provide a robust mechanism to validate the LLM’s annotations and propagate the financial meanings consistently throughout the code. This hybrid approach mitigates the weaknesses of each individual method. By leveraging rule-based reasoning, the system can detect subtle accounting errors that might be missed by LLMs alone. The iterative feedback loop, where validation results are fed back into the LLM, further enhances accuracy and reduces hallucinations, making this approach more reliable and practical for real-world applications. The success of this hybrid method hinges on the careful design of both the LLM prompting strategy and the rule-based inference rules. Effective rule design requires a deep understanding of the financial domain and common accounting practices. This system is particularly effective in detecting vulnerabilities with substantial monetary consequences. The future of this hybrid approach could involve further refinement of rules and exploring more sophisticated LLM architectures.

Bug Detection#

The paper explores a novel approach to smart contract bug detection, focusing on the financially impactful category of accounting errors. It leverages a hybrid methodology, combining the semantic understanding capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) with the precision of rule-based reasoning. The LLM’s role is to annotate the financial meaning of variables within the smart contract code, providing context for the subsequent rule-based analysis. This hybrid approach mitigates the limitations of solely relying on LLMs by reducing hallucinations and improving generalization. The rule-based component ensures deterministic validation and allows for the efficient propagation of financial meanings, leading to a more robust detection process. A key innovation is the iterative feedback loop designed to remedy LLM hallucinations. The feedback mechanism involves presenting the reasoning trace to the LLM for self-reflection, allowing for iterative correction and increased accuracy. The evaluation demonstrates that the proposed system achieves significant accuracy in identifying financial meanings and a high recall rate in detecting accounting bugs, showcasing its potential for enhancing the security of smart contract systems.

Trace Validation#

Trace validation, in the context of this research paper, is a crucial step to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the automated bug detection system. The system uses LLMs to annotate financial meanings in smart contracts and rule-based reasoning to propagate these meanings and check for accounting errors. However, LLMs are prone to hallucinations. To address this, the system incorporates a feedback loop: It provides the LLM with reasoning traces of potential bugs, allowing the model to self-reflect and iteratively refine its annotations. This iterative validation process is vital in distinguishing between genuine bugs and annotation errors, significantly enhancing the precision of the system’s findings. Reasoning traces, therefore, become not just a byproduct of the validation, but an integral element in improving the model’s accuracy and correcting hallucinations. The efficacy of this approach highlights the importance of combining LLMs’ capabilities with robust validation mechanisms for reliable bug detection in complex systems. The feedback loop’s success demonstrates a powerful strategy to address the inherent uncertainty of LLM outputs in a high-stakes setting such as automated smart contract auditing, where accuracy is paramount.

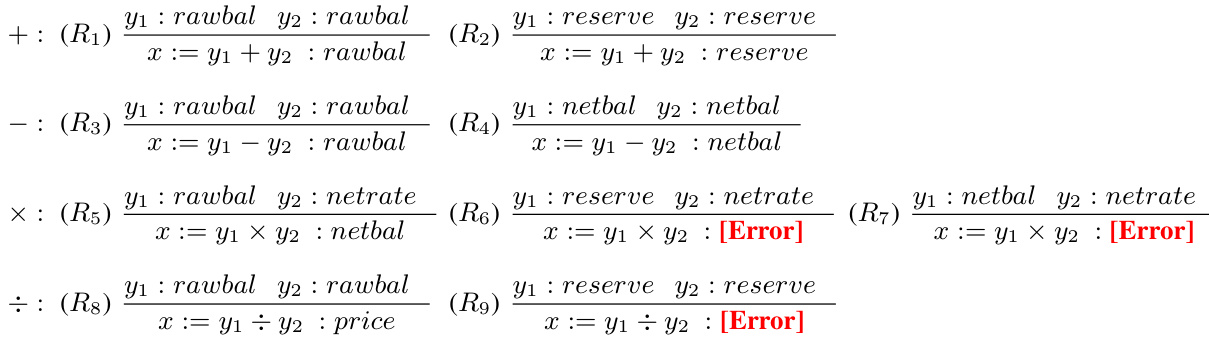

Financial Meaning#

The concept of “Financial Meaning” is central to the research paper’s methodology for detecting accounting bugs in smart contracts. It involves assigning semantic meaning to variables within the code, going beyond their syntactic types to understand their financial role (e.g., balance, price, reserve). This semantic annotation, primarily achieved using a Large Language Model (LLM), forms the crucial first step. The LLM’s interpretation, however, is prone to errors (hallucinations). Therefore, a rule-based system is then used to propagate the financial meanings through the contract’s logic, checking for inconsistencies. This hybrid approach of LLM and rule-based reasoning is key to overcoming the limitations of each individual method, aiming for higher accuracy and robustness. The success of this approach hinges on the accuracy of the initial financial meaning assignment. The paper evaluates this accuracy against human annotations, demonstrating the system’s capability. The detailed discussion of financial meanings, along with the inference rules used for validation, suggests a potentially significant contribution for formalizing the semantic aspects of financial logic within smart contracts. The research, ultimately, advocates for a more nuanced and context-aware approach to vulnerability detection.

Future Work#

The paper’s core contribution is a hybrid LLM and rule-based system for detecting accounting bugs in smart contracts. Future work naturally centers on expanding the system’s capabilities and addressing limitations. Specifically, expanding the range of supported financial meanings beyond the current six is crucial. The model’s performance is currently sensitive to variable names; improvements here would enhance robustness. While a reasoning trace method reduces hallucinations, a more sophisticated approach for handling hallucinations and improving accuracy is needed. Further investigation is also needed to deal with accounting errors not captured by the rule-based system, potentially incorporating advanced techniques. Finally, expanding the system’s support for other programming languages beyond Solidity would significantly broaden its applicability and impact within the smart contract ecosystem. This expansion should also consider the unique nuances of different languages’ syntax and semantics. The integration of path-sensitive analysis techniques could be explored to improve the handling of complex, conditional logic within smart contracts. Ultimately, further research should focus on improving the efficiency and scalability of the system, while also exploring the implications of its use for different kinds of audits and its interaction with broader blockchain security considerations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

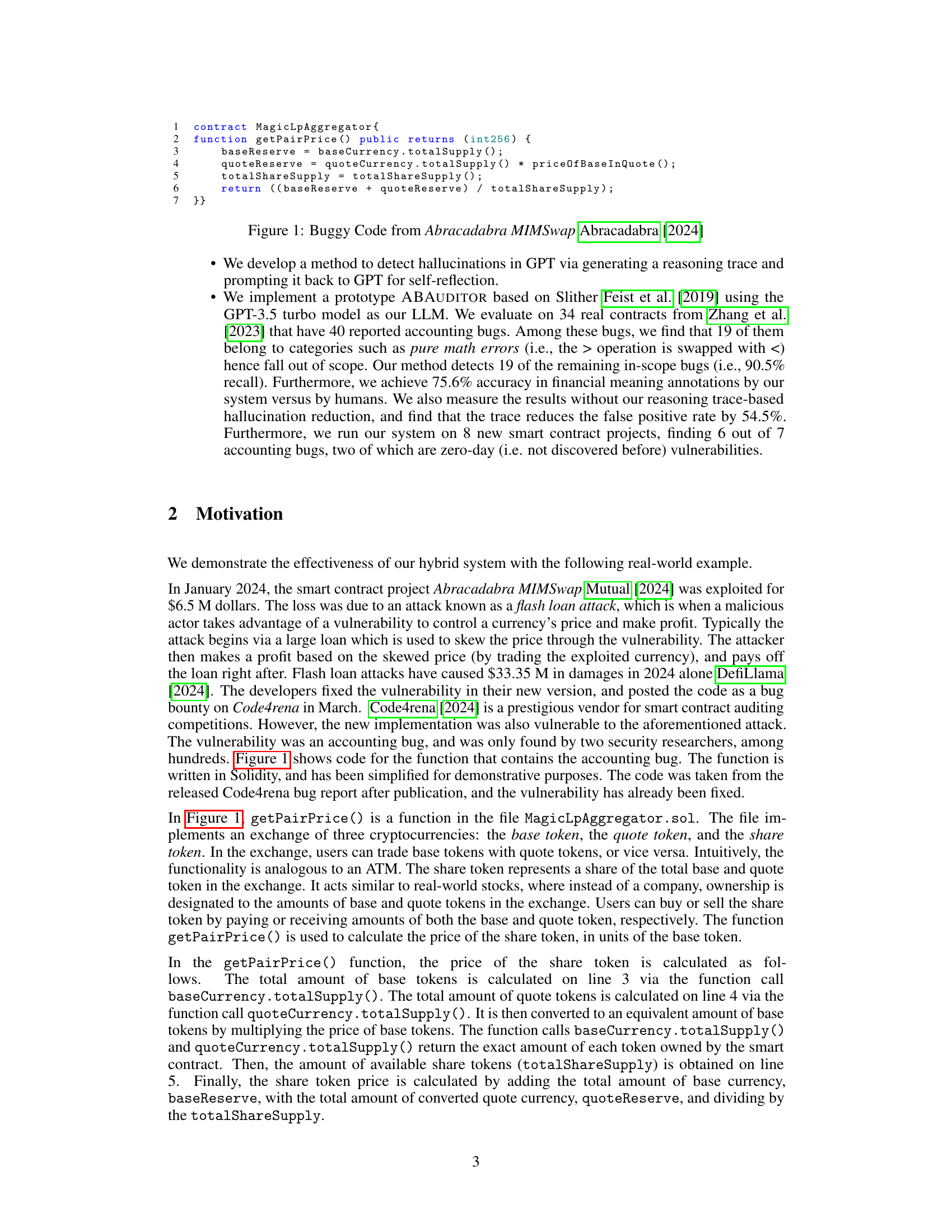

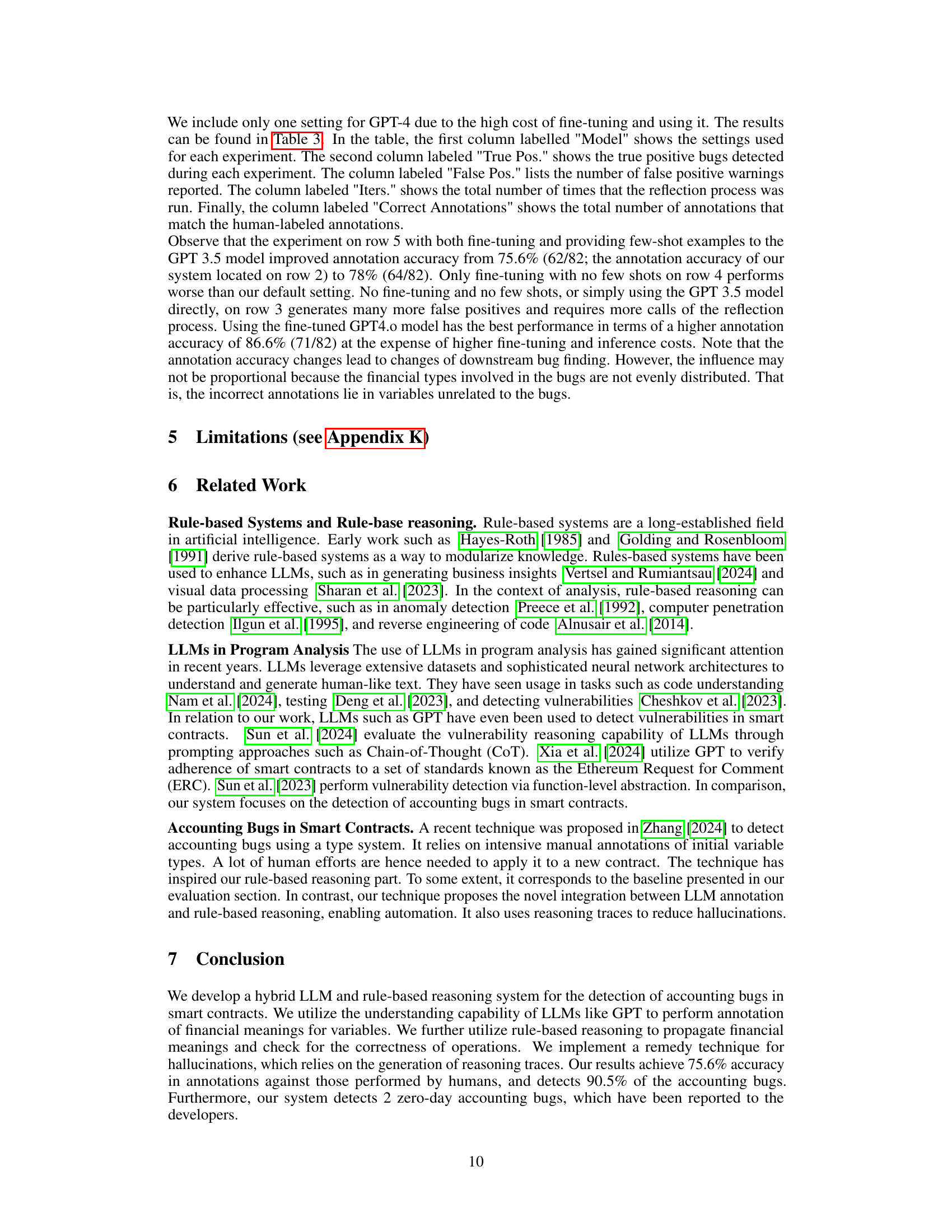

This figure shows a Solidity smart contract with two functions:

tswapandapplyFee. Thetswapfunction is a public function that performs a currency swap, applying a fee using the internalapplyFeefunction. The accounting bug lies in the double application of the fee within thetswapfunction, resulting in an incorrect final amount.

This figure shows a Solidity smart contract with two functions:

tswap()andapplyFee(). Thetswap()function is a public function that swaps an amount of one currency for another, applying a fee in the process. TheapplyFee()function is an internal function that deducts the fee from the input amount. The accounting bug lies in thetswap()function, specifically in how the fee is applied twice, resulting in a smaller remaining amount than intended.

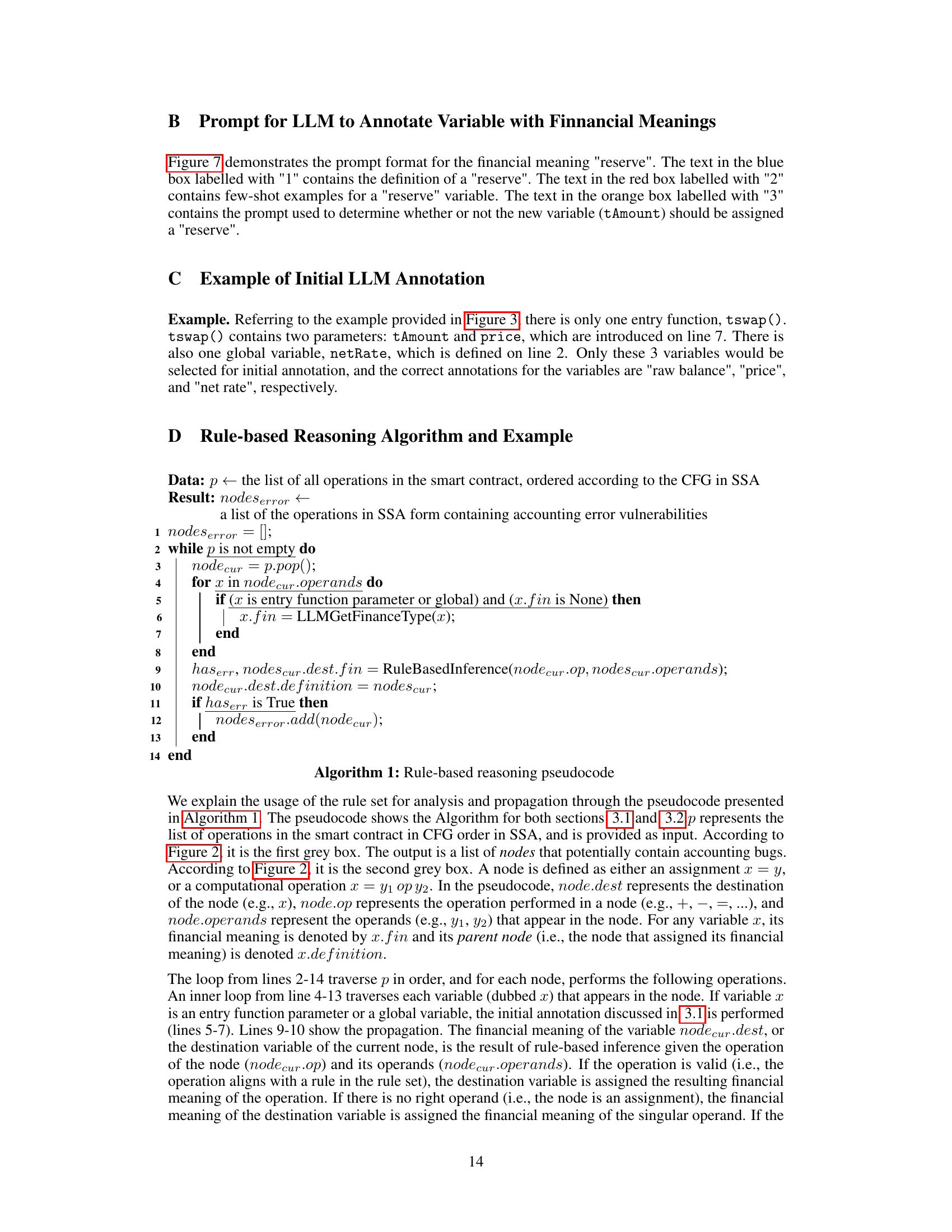

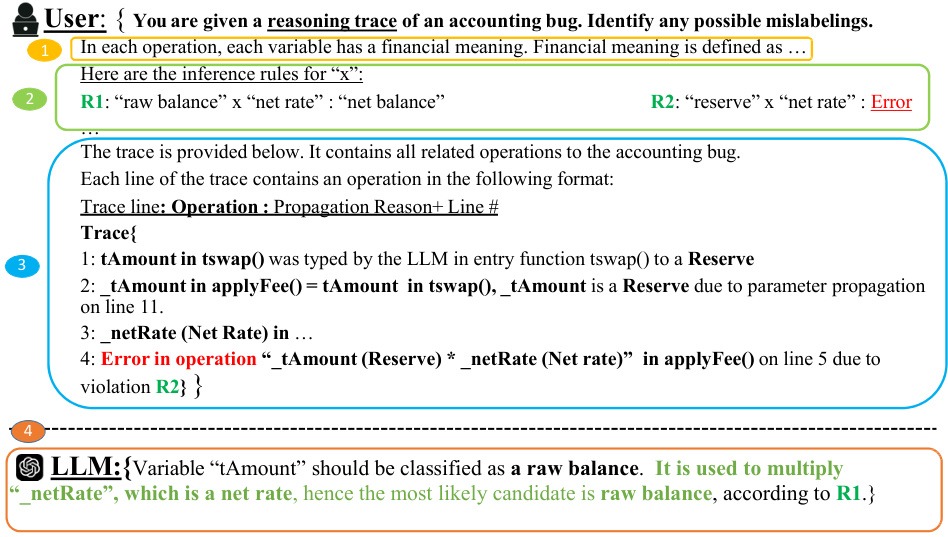

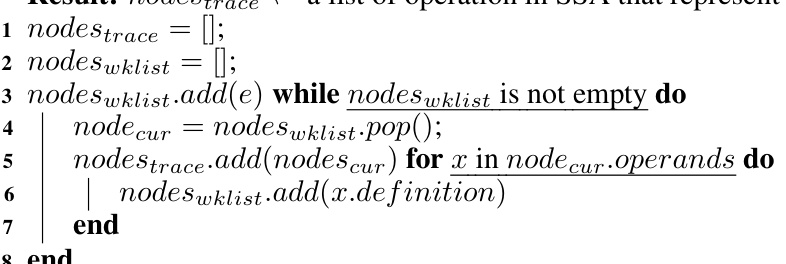

This figure demonstrates an example of how the system uses a reasoning trace to identify and correct hallucinations produced by the LLM. The LLM initially mislabels the variable ’tAmount’ as a ‘Reserve’ instead of a ‘raw balance.’ The system generates a reasoning trace that shows the LLM’s reasoning steps and the inference rules used. This trace is then given to the LLM again as a prompt to determine any possible mislabeling. Based on the trace, the LLM corrects its initial annotation, identifying that ’tAmount’ should have been classified as a ‘raw balance’. This example highlights the system’s ability to leverage the LLM’s capabilities while mitigating its potential for hallucinations.

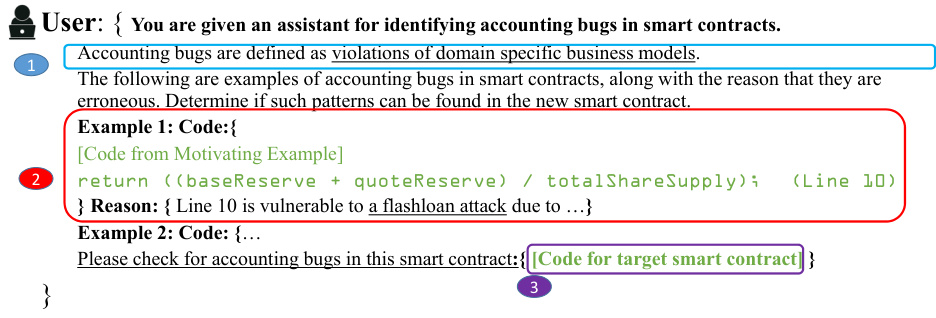

The figure shows the format of the prompt used for the naive approach of directly prompting the LLM with few-shot accounting bug examples and asking it to find new bugs of a similar nature. It consists of three parts: 1. Definition of accounting bugs; 2. Few-shot examples (code and reason for being erroneous); 3. The new smart contract to analyze.

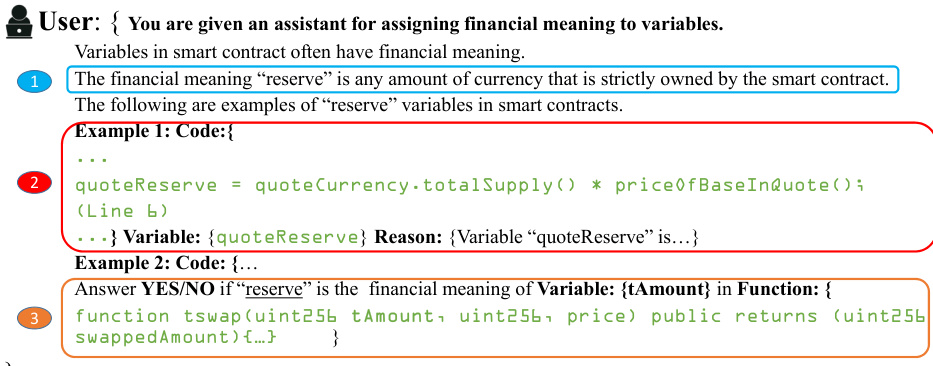

The figure shows the format of the prompt used for the initial annotation task. The prompt asks whether a given variable has a specific financial meaning. It provides a definition of the financial meaning along with examples of variables having that meaning. The user is asked to answer YES or NO.

This figure shows a Solidity smart contract with two functions:

tswap()andapplyFee().tswap()is a public function that performs a currency swap, applying a fee via the internalapplyFee()function. The accounting bug lies in the fee deduction withinapplyFee(), where the fee is applied twice, resulting in an incorrect remaining amount after the swap.

The figure illustrates the architecture of ABAUDITOR, a hybrid LLM and rule-based reasoning system for detecting accounting errors in smart contracts. It shows the flow of processing, starting with smart contract input, through several stages including pre-processing, SSA conversion, LLM annotation, rule-based reasoning, validation, and hallucination remedy. The output is a list of potential accounting error vulnerabilities.

This figure demonstrates an example of how the system uses a reasoning trace to identify and correct hallucinations by the LLM. The prompt shows the reasoning trace, which includes the LLM’s initial annotation, the propagation of financial meanings, and the identification of a potential accounting bug. The LLM then responds by correcting the initial annotation, leading to a revised classification and the removal of the bug. This illustrates the iterative validation process employed by ABAUDITOR to improve accuracy and reliability.

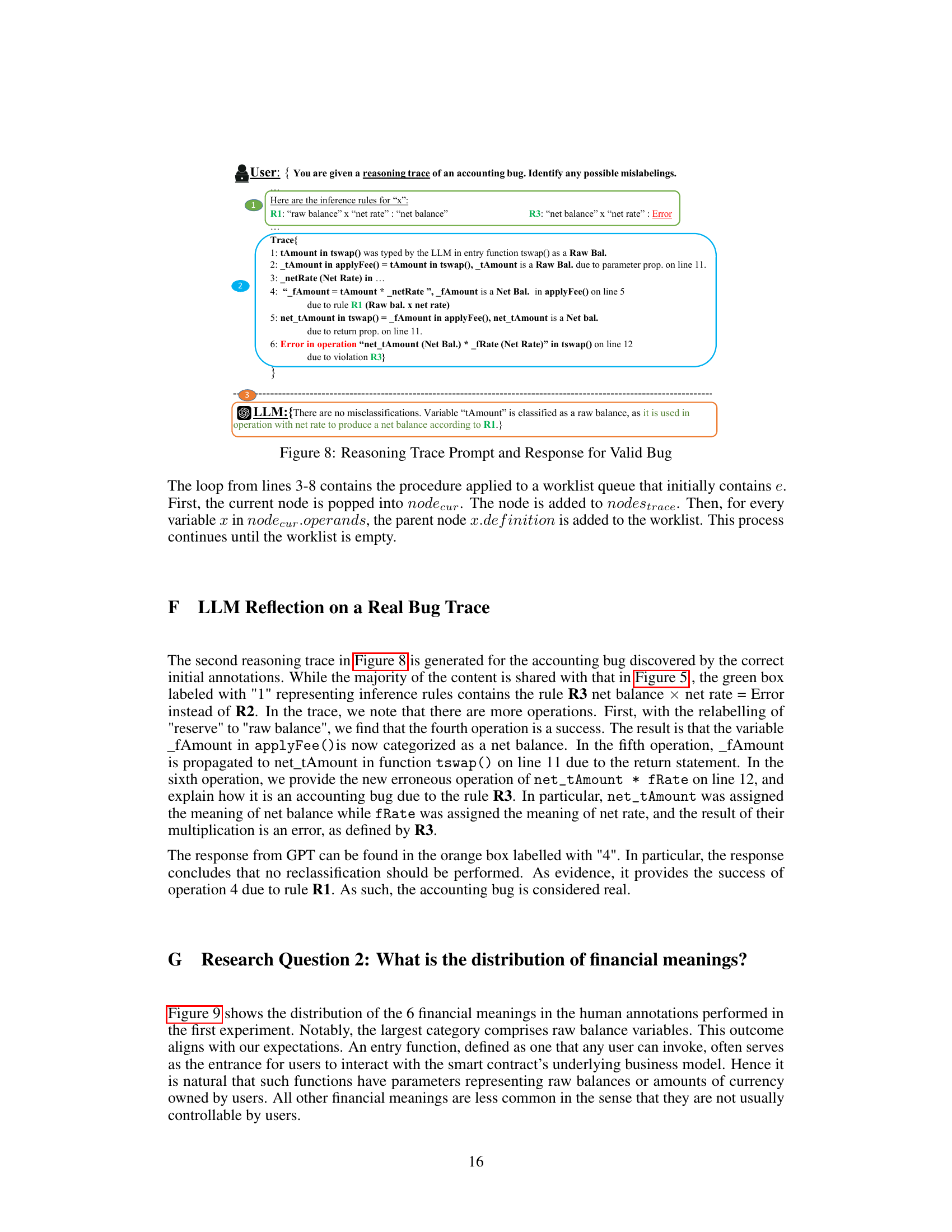

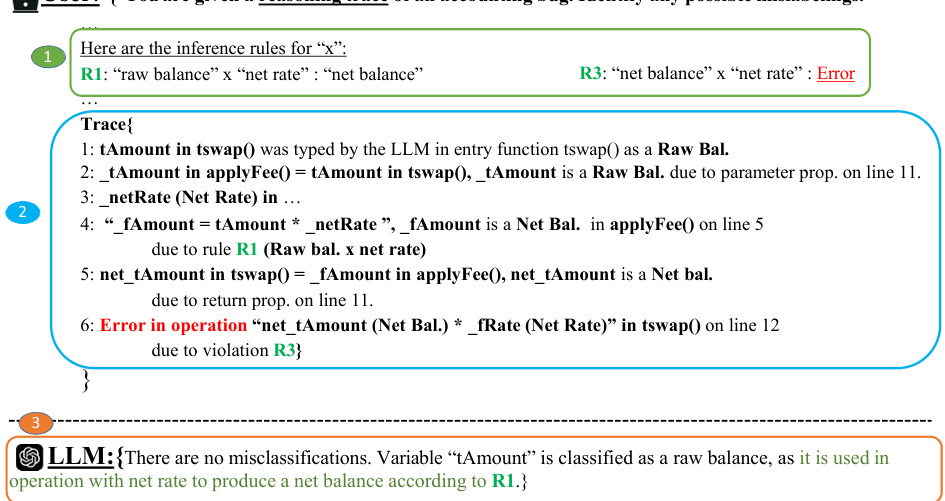

This pie chart shows the distribution of six financial meanings in the human annotations from the first experiment. Raw balance is the most frequent type (67%), followed by reserve (10%), net rate (8%), debt (5%), price (5%), and interest rate (5%). This distribution reflects the prevalence of raw balance variables in entry functions, where they often represent amounts of currency owned by users.

More on tables

This table presents the results of GPTScan, a tool used to detect accounting bugs in smart contracts. It categorizes the detected bugs by type and shows the number of projects where each bug type was found and the total number of instances. The bug types include: Wrong Order Interest, Flashloan Price, First Deposit, and Approval Not Revoked. The table gives insight into the types of accounting vulnerabilities GPTScan is able to identify in real world smart contracts.

This table presents the results of experiments using fine-tuned GPT models for detecting accounting bugs. It compares the performance of different models, including the baseline (manual annotation), ABAUDITOR with GPT-3.5 and few-shot examples, GPT-3.5 without few-shot examples, and fine-tuned versions of GPT-3.5 with and without few-shot examples. The metrics include true positives (TP), false positives (FP), iterations (Iters.) of the hallucination reduction feedback loop, and the number of correct annotations compared to human annotations.

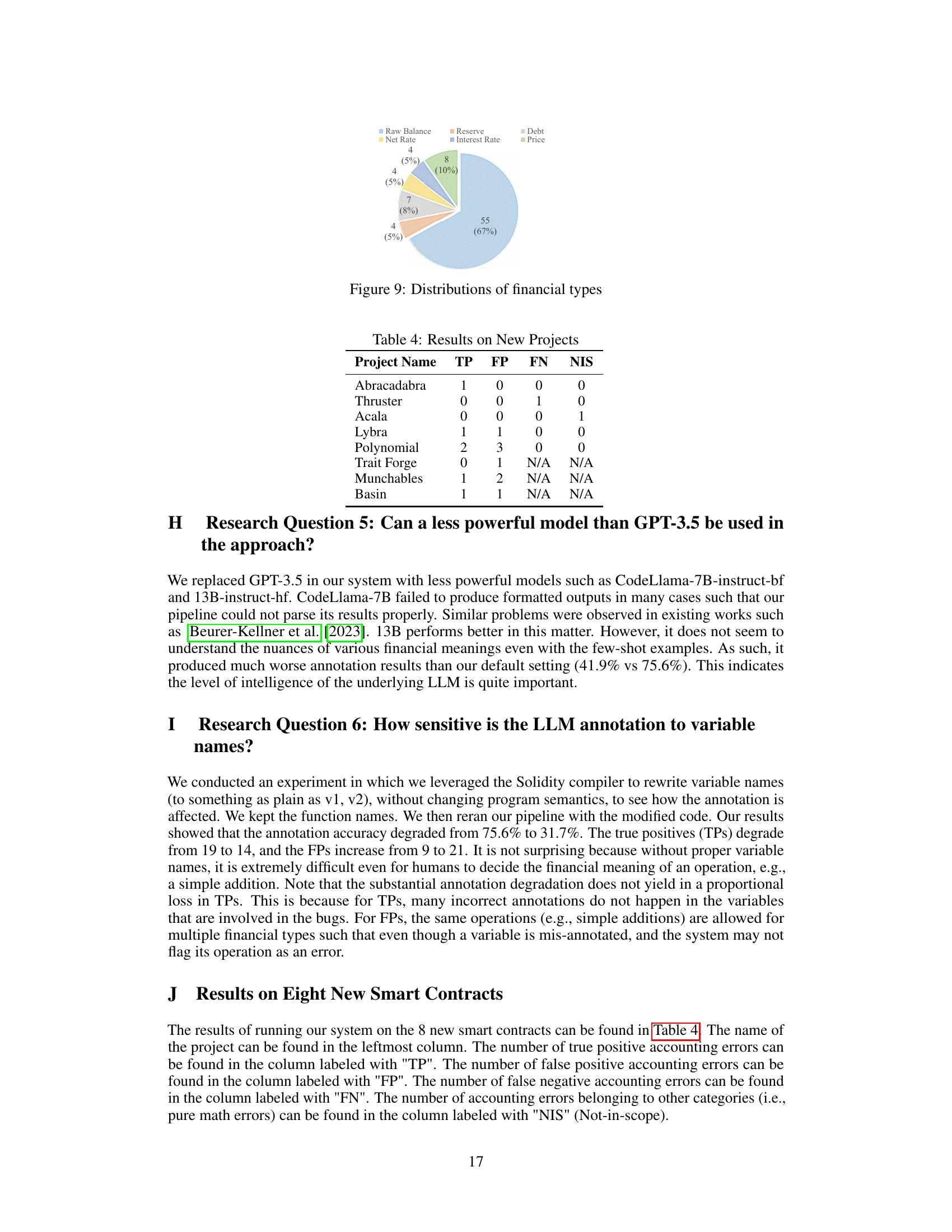

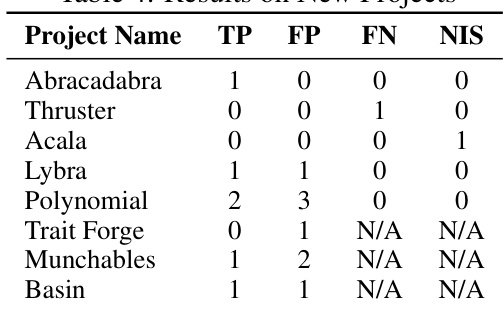

This table presents the results of applying the ABAUDITOR system to eight recently developed smart contracts. The columns represent: Project Name (the name of the project), TP (true positives - the number of correctly identified accounting bugs), FP (false positives - the number of incorrectly identified accounting bugs), FN (false negatives - the number of accounting bugs that were missed), and NIS (not in scope - the number of bugs that are out of scope for the ABAUDITOR analysis). The results show the system’s performance on previously unseen projects, demonstrating its ability to detect real-world accounting vulnerabilities.

Full paper#