↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are powerful tools in machine learning, but their fixed weight matrices limit their ability to adapt to diverse contexts and tasks. This paper tackles this limitation by introducing a novel neuromodulated RNN (NM-RNN) architecture. The NM-RNN incorporates a neuromodulatory subnetwork that dynamically scales the weights of the main RNN, mimicking how neuromodulators work in biological brains. This approach allows for more flexible and adaptable computations.

The NM-RNN model was evaluated across several benchmarks, including timing tasks and multitask learning problems. The results consistently show superior performance and generalizability compared to standard RNNs. The authors also provide theoretical analysis, demonstrating the close connection between NM-RNN dynamics and those of LSTMs, a highly successful type of RNN. Their findings indicate the potential of using neuromodulation as a means for improving the flexibility and efficiency of AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to enhance the flexibility and adaptability of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) by incorporating a biologically-inspired neuromodulation mechanism. This addresses a key limitation of traditional RNNs, their fixed weight matrices, which hinder their ability to handle diverse tasks and contexts. The NM-RNN model presented has potential implications for various fields requiring flexible computation, including artificial intelligence and neuroscience. The study opens new avenues for research by suggesting ways to investigate the complex interplay between neuromodulation and neural dynamics, and how these interactions might improve AI systems’ adaptability.

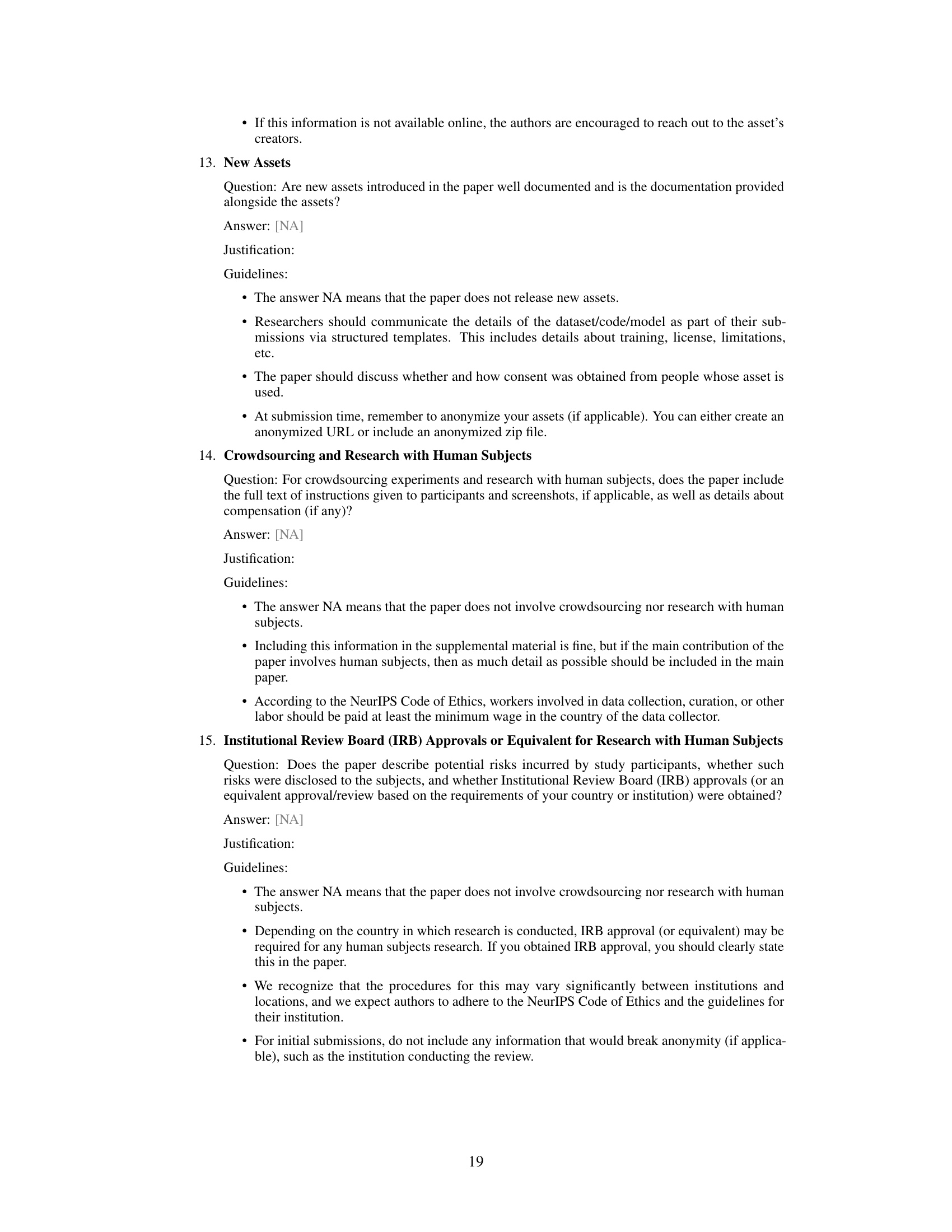

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the architecture of the Neuromodulated Recurrent Neural Network (NM-RNN). It comprises two main components: a neuromodulatory subnetwork and an output-generating subnetwork. The neuromodulatory subnetwork is a smaller, fully connected RNN that generates a time-varying neuromodulatory signal. This signal then modulates the weights of the larger, low-rank output-generating subnetwork. The output-generating subnetwork is a low-rank recurrent neural network that produces the final output of the system. The neuromodulatory signal dynamically scales the low-rank recurrent weights of the output-generating network, providing flexibility and adaptability.

In-depth insights#

Neuromodulated RNNs#

The concept of “Neuromodulated RNNs” introduces a novel approach to recurrent neural networks by incorporating a neuromodulatory subnetwork. This subnetwork dynamically scales the weights of the main RNN, enabling flexible and structured computations. Neuromodulation allows for the dynamic adaptation of the network’s behavior, mirroring biological systems where synaptic plasticity is heavily influenced by neuromodulators like dopamine. This approach yields improved accuracy and generalization on various tasks compared to traditional RNNs. Furthermore, the inclusion of a neuromodulatory signal provides a mechanism for gating, similar to LSTMs, enabling the network to handle long-term dependencies and temporal information more effectively. The model’s low-rank architecture facilitates easier analysis of dynamic behavior and its distribution among the network’s components. Neuromodulated RNNs, therefore, represent a compelling biological model and a potentially powerful machine learning tool that bridges the gap between biological plausibility and computational efficiency.

Low-Rank Dynamics#

The concept of ‘Low-Rank Dynamics’ in the context of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) is intriguing. It suggests that despite the network’s potentially high dimensionality, the essential computations unfold within a lower-dimensional subspace. This is particularly relevant for understanding biological neural systems, where low-rank structures have been observed in neural recordings. Analyzing the low-rank dynamics allows researchers to gain insights into the essential features and computational mechanisms underlying the networks’ behavior. This approach can offer a more interpretable view of complex RNN dynamics, aiding in the design of efficient and biologically plausible network architectures. Moreover, leveraging low-rank decompositions provides a powerful tool for visualizing and interpreting how task computations are distributed within the network. It could unveil hidden modularity or other inherent structure, thereby enhancing the understanding of both artificial and biological intelligence. The use of neuromodulation adds further complexity, possibly influencing which low-rank components are active, hence affecting the task computations within the low-dimensional subspace. This suggests the potential of neuromodulation for creating dynamic and flexible computations through a control of low-rank dynamics.

Timing Task Results#

The timing task results section would likely present empirical evidence demonstrating the NM-RNN’s ability to accurately perform timing tasks. A key aspect would be a comparison against traditional RNNs and possibly LSTMs, highlighting the NM-RNN’s superior generalization capabilities, especially on extrapolating to untrained timing intervals. The results might involve quantitative metrics such as mean squared error or correlation with target timing, showcasing the NM-RNN’s improved accuracy. Visualizations of the network’s output, such as a comparison of the generated ramp signals against the desired ramp, would be critical. Analysis of the neuromodulatory signals’ role in the timing process is also important and would likely involve detailed visualizations showing how the neuromodulatory signals align with the timing cues and adapt to different intervals, potentially suggesting their role as gating or timing mechanisms. The discussion would need to address any limitations of the empirical findings and possibly explore potential biological interpretations based on the neuromodulatory model used.

Multitask Learning#

The concept of multitask learning, applied within the context of recurrent neural networks (RNNs), is a powerful technique that leverages the shared representation of multiple tasks to improve generalization and efficiency. The core idea is that by training a single model to perform multiple tasks simultaneously, the model can learn more generalizable features that are applicable across tasks. This approach contrasts with traditional single-task learning, which trains separate models for each task, potentially leading to overfitting and reduced efficiency. The success of multitask learning depends heavily on the relatedness of the tasks; related tasks benefit more from shared representations. In the case of RNNs, multitask learning can be particularly effective in scenarios where the tasks share similar temporal dynamics, enabling more efficient learning of temporal dependencies. However, challenges remain in designing effective architectures and training strategies for multitask RNNs. Careful consideration must be given to how the tasks are integrated, how the model weights are shared, and how to prevent interference between tasks. The ability to effectively leverage the underlying structure of the data is critical for success in multitask learning. Careful selection of tasks and proper weight sharing can dramatically improve performance and generalization. In this context, it is important to study how the model dynamically adapts to various tasks and how shared representations are formed and utilized during the learning process.

Future Research#

The ‘Future Research’ section of this paper suggests several promising avenues. Expanding the NM-RNN model to encompass a wider range of neuromodulatory roles is crucial, including exploring both excitatory and inhibitory effects and the impact of neuromodulators on different timescales. Investigating how different neuromodulatory effects might interact, particularly their temporal dynamics, is key to understanding their combined impact on neural computation. Further research should also explore the effects of neuromodulation on network learning. The authors propose to examine how neuromodulation might interact with existing learning rules, potentially leading to more biologically plausible learning mechanisms. Finally, given the biological complexity of the brain, extending the model to include a wider range of signaling mechanisms beyond neuromodulation, like neuropeptides and hormones, is warranted to achieve higher fidelity and uncover further computational insights.

More visual insights#

More on figures

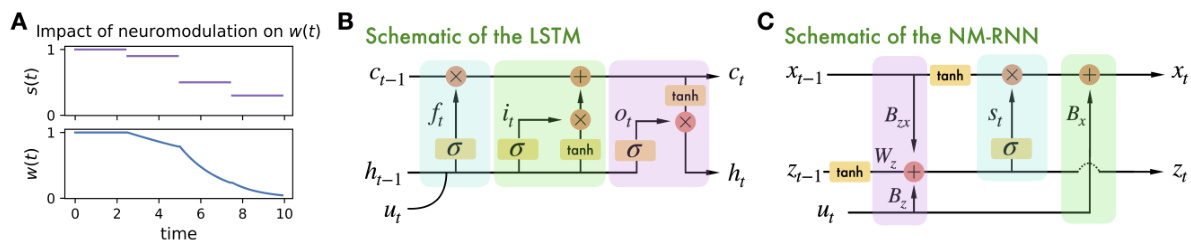

This figure compares the NM-RNN and LSTM networks, highlighting their similarities. Panel A shows how neuromodulation affects the decay rate of a simplified model’s state variable. Panels B and C provide a visual comparison of the NM-RNN and LSTM, emphasizing the structural similarities between them by highlighting corresponding components with color-coded rectangles.

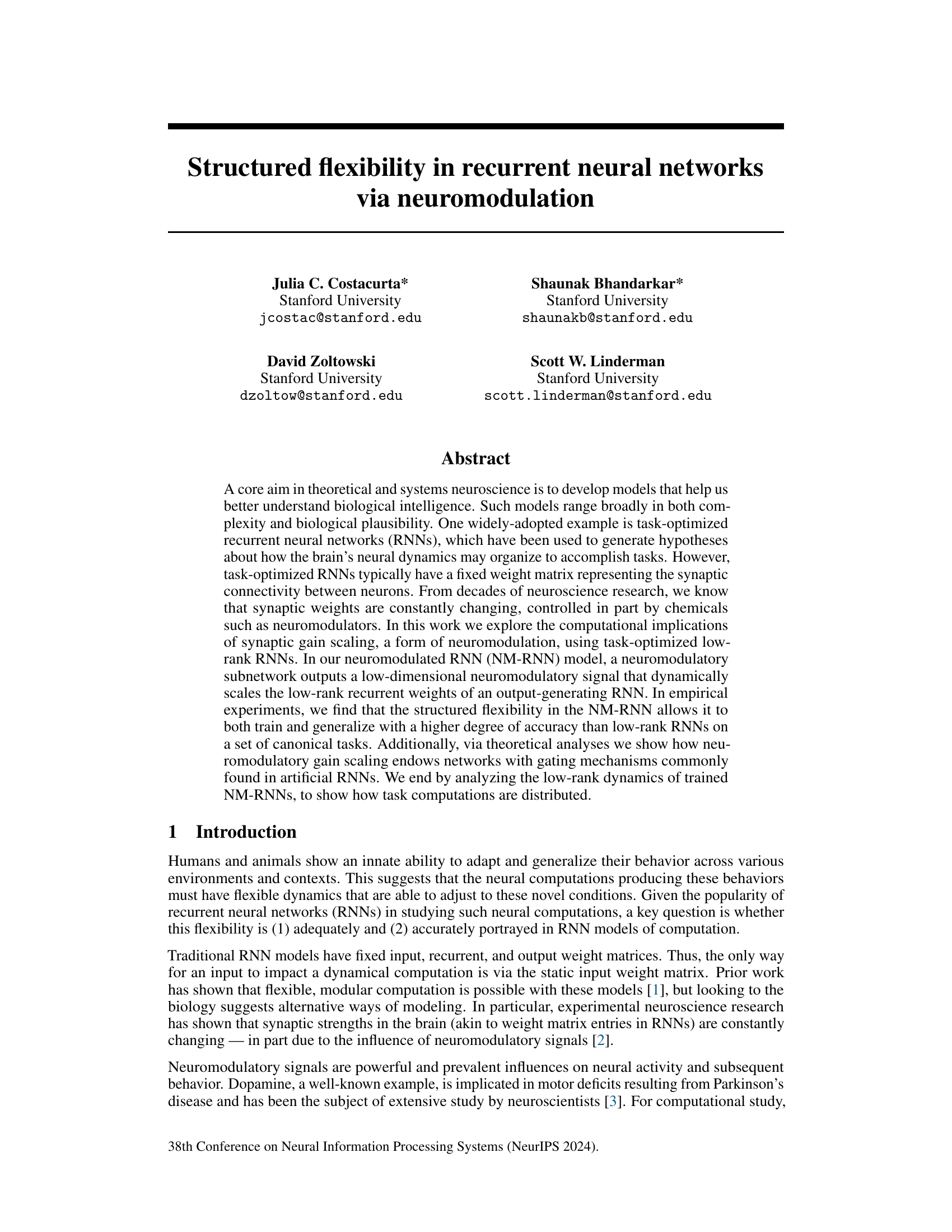

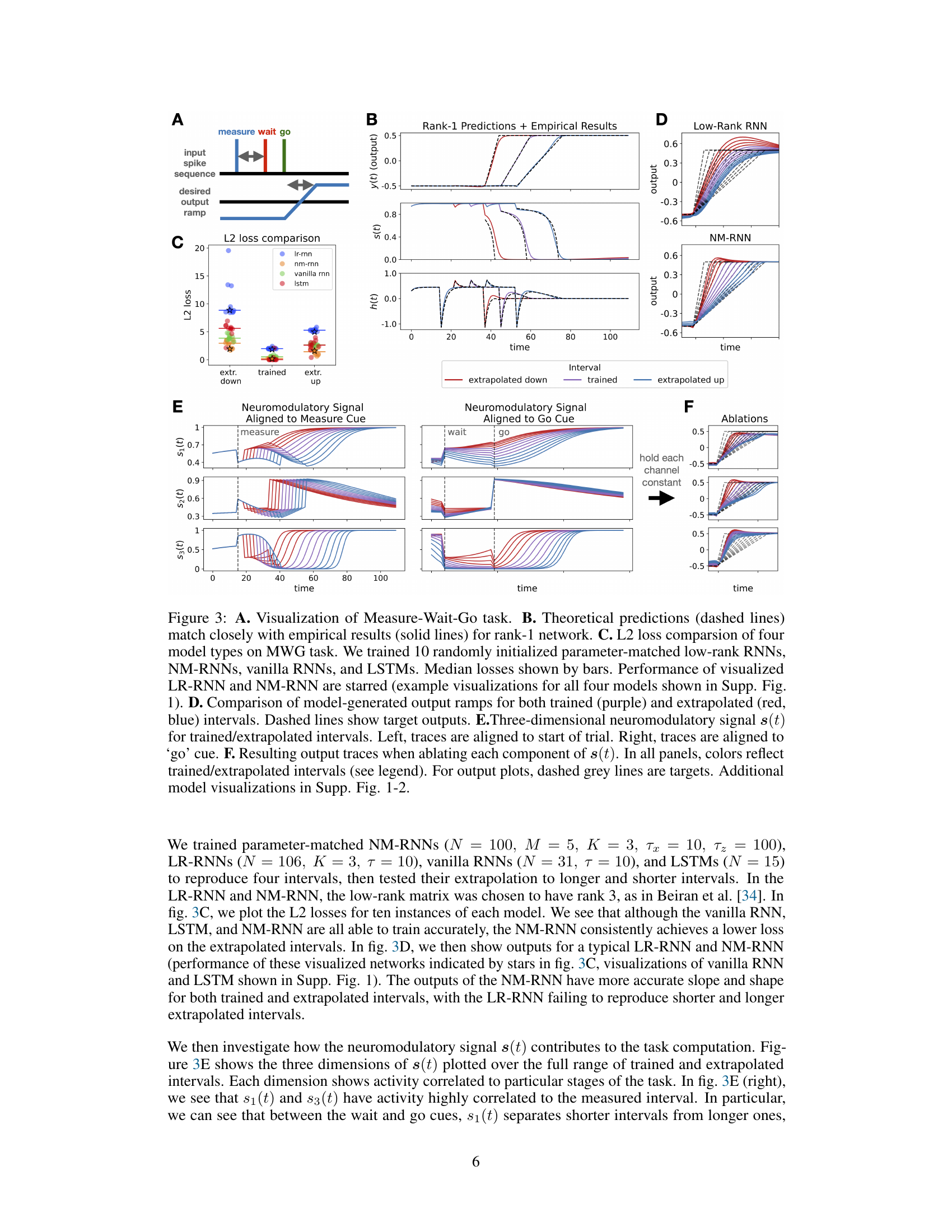

This figure shows the results of applying the NM-RNN model to a timing task, comparing its performance to other RNN architectures. Panel A shows a schematic of the task. Panel B shows the close match between theoretical predictions and empirical results obtained using a rank-1 NM-RNN. Panel C compares the performance (measured by L2 loss) of NM-RNNs, low-rank RNNs, vanilla RNNs and LSTMs on the task. Panel D visualizes the output ramps generated by these models for trained and extrapolated intervals. Panel E shows the three-dimensional neuromodulatory signal (s(t)) during the task. Panel F shows the impact of ablating each component of the neuromodulatory signal on the model’s performance.

This figure shows the results of the Measure-Wait-Go (MWG) task. It compares the performance of four different RNN models: low-rank RNNs, NM-RNNs, vanilla RNNs, and LSTMs. The figure includes plots showing the theoretical predictions vs. empirical results for a rank-1 network, a comparison of L2 losses for the four models, a comparison of the generated output ramps for trained and extrapolated intervals, the three-dimensional neuromodulatory signal, and the resulting output traces when ablating each component of the neuromodulatory signal. The results show that the NM-RNN outperforms other models in both accuracy and generalization.

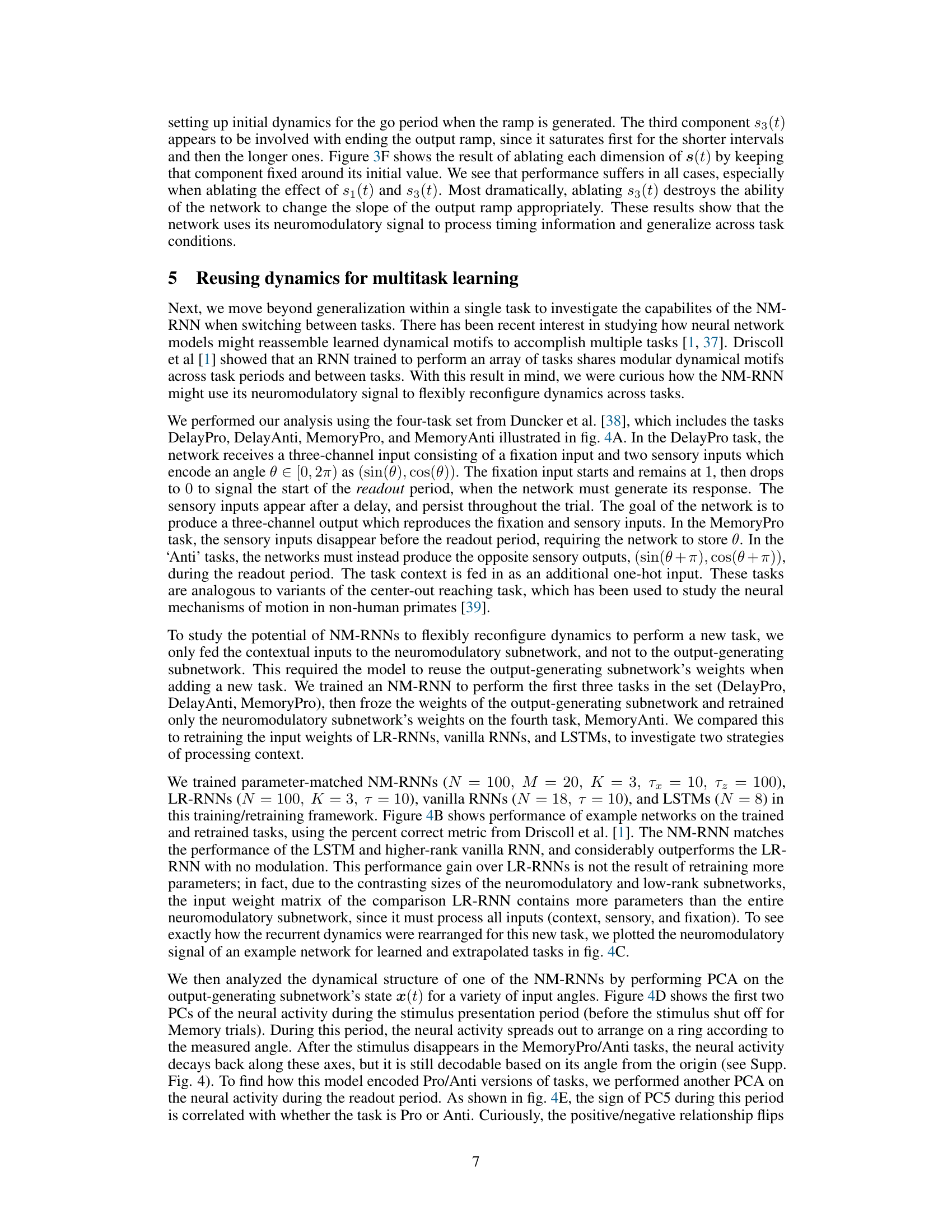

This figure shows the results of the Element Finder Task (EFT). Panel A describes the EFT. Panel B compares the performance of different RNN models (LSTM, NM-RNNs, LR-RNNs, and RNNs) on the EFT in terms of Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss. Panel C displays the training dynamics (MSE loss over iterations) for different NM-RNN models and other models. Panels D-F provide visualizations of the NM-RNN’s internal dynamics, showing how the neuromodulatory signal (s(t)) and the latent states of the neuromodulatory (z(t)) and output-generating (x(t)) subnetworks evolve across different query indices and target values during the EFT.

Full paper#