↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many graph embedding methods use sampling due to the impracticality of processing full adjacency matrices, especially for large graphs. This can lead to incomplete representation and hinder model performance. This paper tackles this by investigating the minimal number of entries needed to uniquely identify a graph’s structure within a specific class (transitively-closed DAGs).

The researchers introduce a novel framework to identify this minimal data subset and demonstrate its effectiveness. They propose a new hierarchy-aware sampling method which utilizes the reduced data set. Using synthetic and real-world data, they show improved convergence rates and performance on node embedding models with an appropriate inductive bias. This significantly enhances the efficiency of graph representation learning, especially for resource-constrained scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large graphs, especially in resource-constrained settings. It offers significant efficiency gains by reducing the number of training examples needed, thus making large-scale graph embedding more feasible. Additionally, it introduces a novel framework that could be adapted for various graph properties, opening new avenues for research in efficient graph representation learning.

Visual Insights#

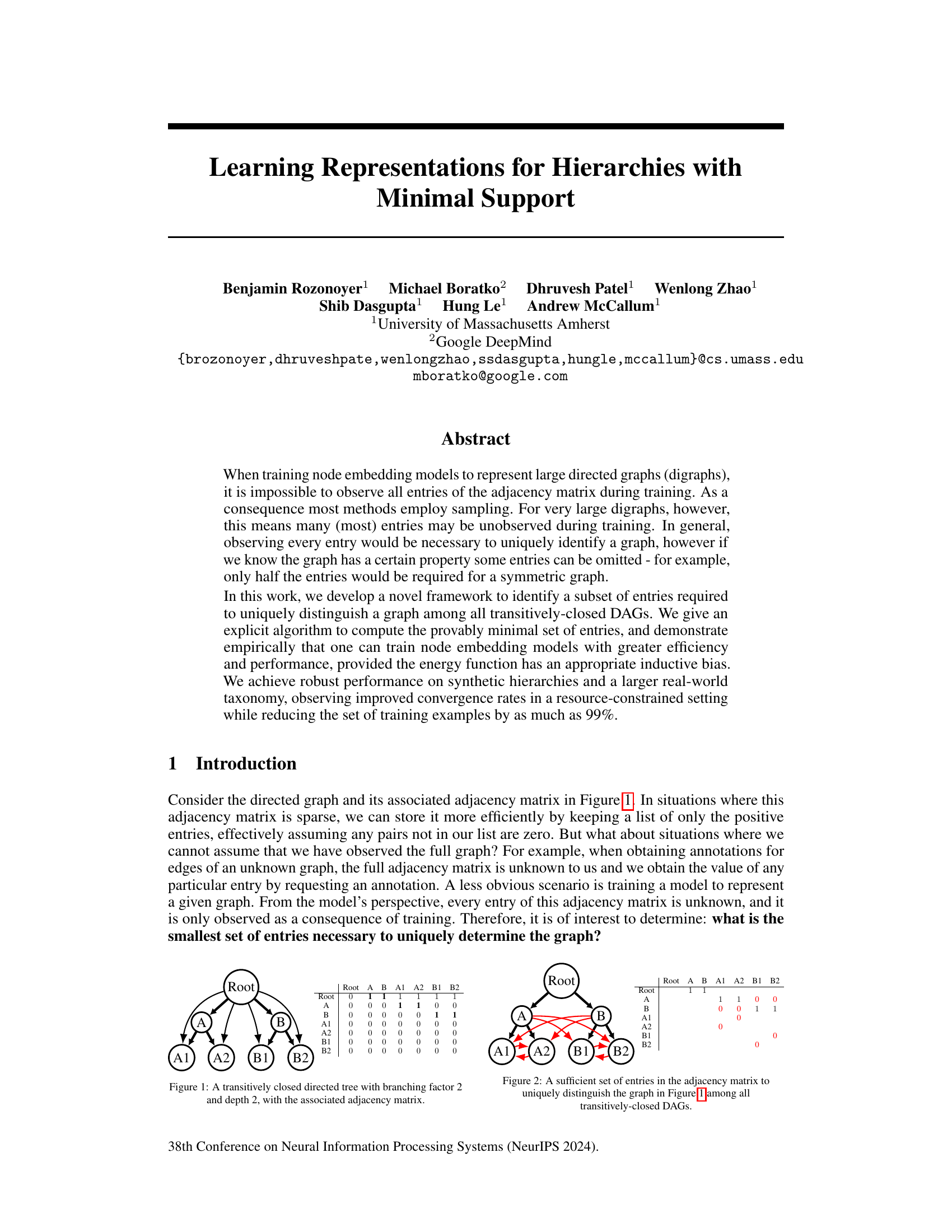

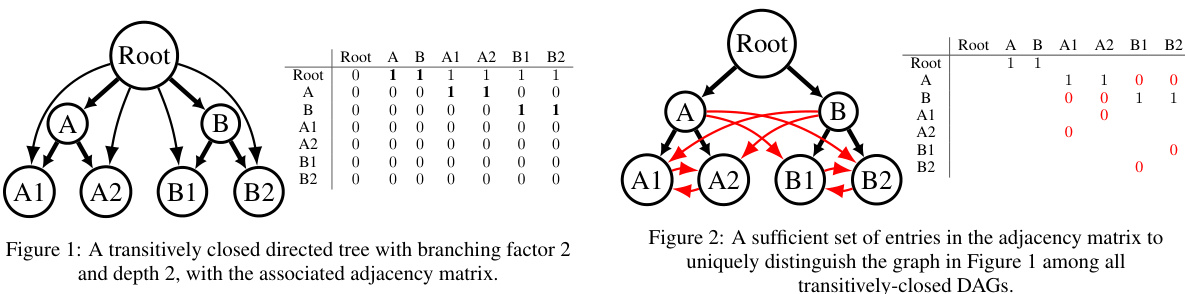

This figure shows a small directed acyclic graph (DAG) that is transitively closed, meaning if there is a path from node A to node B, then there is also a direct edge from A to B. The graph has a root node connected to two intermediate nodes (A and B), which in turn are each connected to two leaf nodes. The adjacency matrix alongside the graph visually represents the connections between nodes; a ‘1’ indicates a direct edge, and a ‘0’ indicates the absence of an edge.

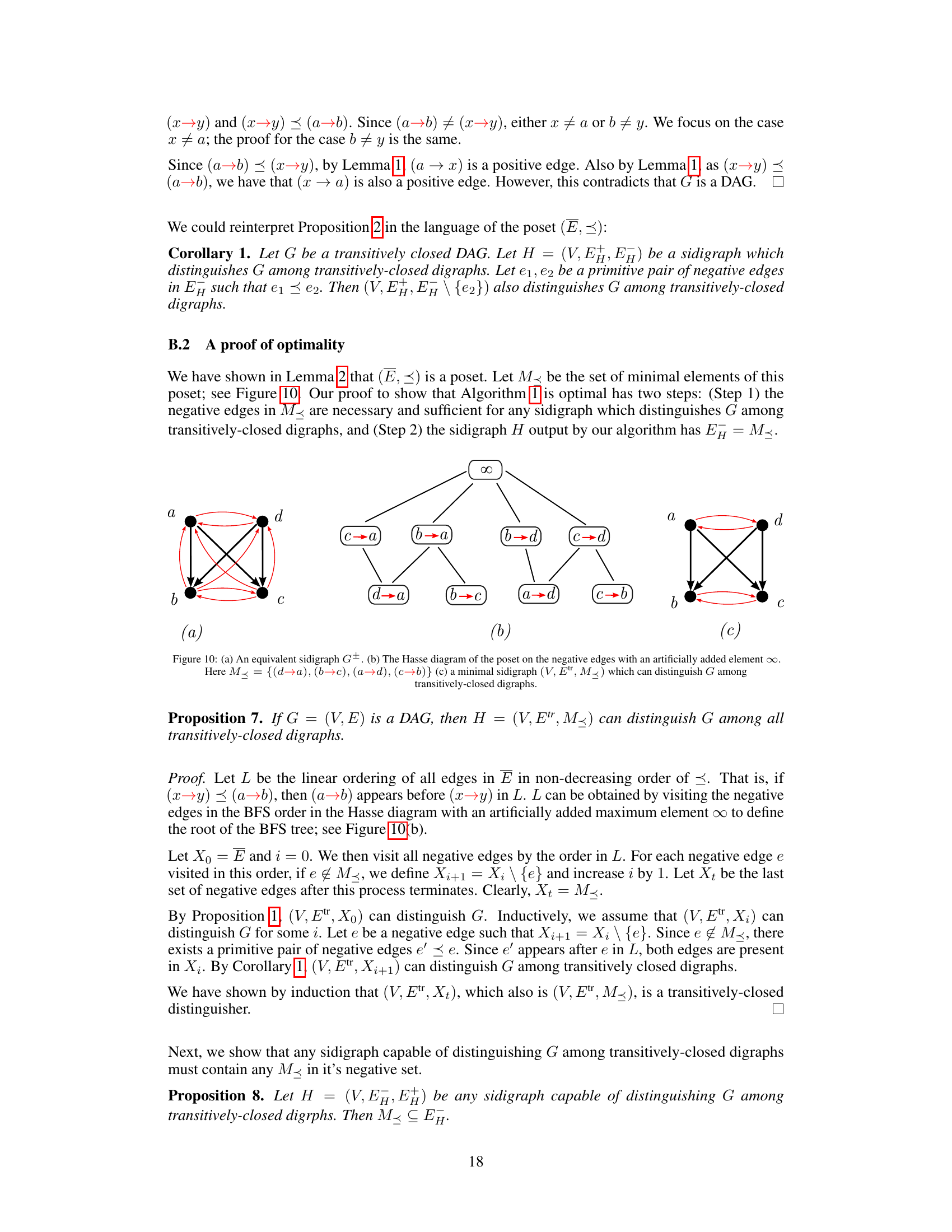

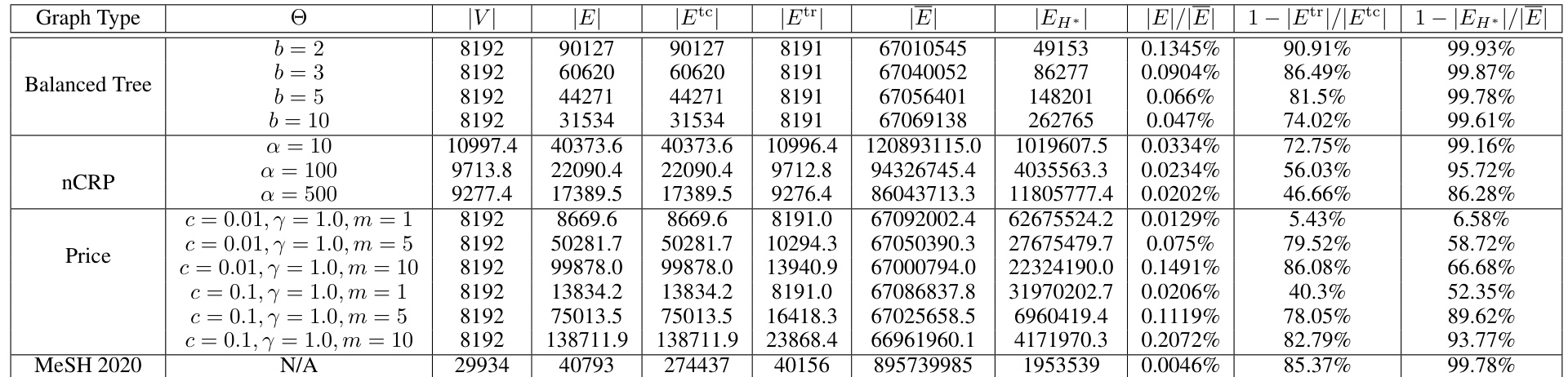

This table presents statistics for synthetic transitively-closed directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) used in the experiments described in Section 6 of the paper. It shows the number of vertices (V), edges (E), edges in the transitive closure (Etc), edges in the transitive reduction (Etr), edges in the complement (E), edges in the minimal distinguishing sidigraph (EH*), and several ratios related to these quantities. The ratios help quantify the reduction in the number of edges used in the ‘reduced’ experimental setting compared to the ‘full’ setting. Note that the statistics for nCRP and Price models are averages over 10 random seeds, while the Balanced Tree graphs are deterministic.

In-depth insights#

Minimal Graph Representation#

Minimal graph representation seeks to reduce the complexity of storing and processing graph data by identifying the smallest subset of information sufficient to uniquely define the graph structure. This concept is particularly relevant in large-scale graph analysis where complete representations are often intractable. Optimizing for minimality offers significant benefits in terms of storage efficiency, computational speed, and bandwidth usage. However, it requires careful consideration of the trade-off between minimality and preserving key structural properties. A minimal representation must still capture sufficient information to accurately reconstruct the graph for any downstream analysis. Furthermore, the effectiveness of minimal representation techniques is intrinsically linked to the specific characteristics of the graph, including its density, connectivity, and the presence of any inherent hierarchical structures. This suggests that optimal minimal representation methods may need to adapt to the graph’s unique properties and the desired level of detail required for analysis.

Transitivity Bias#

The concept of “Transitivity Bias” in node embedding models for directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) centers on the idea that the model’s energy function should implicitly encode the transitive nature of hierarchical relationships. A model with transitivity bias would predict a high likelihood of a relationship between nodes u and w if it already predicts high likelihoods for relationships u→v and v→w. This bias leverages the inherent structure of DAGs, where an edge between two nodes implies a transitive closure of relationships. By incorporating this bias, the model can learn more efficiently and effectively from a smaller subset of training data. The implication is that training data can be pruned substantially, reducing the computational cost and improving convergence while still maintaining accuracy. This is especially crucial for extremely large DAGs, where observing every entry in the adjacency matrix is impossible. However, relying solely on this bias also presents limitations; it might restrict the model’s ability to capture other non-transitive relationships crucial to a complete graph representation. The optimal approach is to strike a balance, incorporating the bias effectively but allowing for flexibility in capturing non-transitive relationships.

Hierarchy-Aware Sampling#

The proposed “Hierarchy-Aware Sampling” method is a crucial contribution, addressing the challenge of training node embedding models efficiently on large hierarchical graphs. Traditional methods often rely on random sampling of edges, which can be inefficient and fail to capture the hierarchical structure effectively. This novel approach leverages the concept of minimal distinguishing sidigraphs to identify a small, yet sufficient, subset of edges (positive and negative) for training. By focusing on this minimal subset, the algorithm significantly reduces the training data size while retaining crucial information for capturing the hierarchy. This results in faster convergence rates and potentially improved performance. The method’s effectiveness hinges on the energy function having an appropriate inductive bias, such as transitivity bias, to ensure the model accurately represents hierarchical relationships based on the reduced edge set. This smart sampling strategy is particularly effective for transitively-closed DAGs and offers a powerful way to improve scalability and resource efficiency in training node embedding models for hierarchical data.

Box Embedding#

Box embeddings offer a unique approach to knowledge graph representation by encoding entities as hyperrectangles (boxes) in a high-dimensional space. Unlike traditional node embeddings that represent entities as points, this method captures uncertainty and variability inherent in real-world data by representing entities with regions rather than precise points. This results in richer, more expressive representations that better reflect the imprecise and multifaceted nature of knowledge. The geometric relationships between boxes, such as containment or overlap, then model relationships within the knowledge graph, providing a powerful mechanism for capturing various types of relationships. While computationally more intensive than point-based embeddings, the richer representations offered by box embeddings can lead to improved performance in tasks requiring robust handling of uncertainty and nuanced relationships, such as those found in hierarchical knowledge graphs. However, challenges remain, particularly in efficiently training box embedding models for large-scale knowledge graphs and in further developing the theoretical underpinnings and inductive biases that can fully leverage the expressive power of this representation.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore extending the framework to other graph properties beyond transitive closure, such as exploring specific structural motifs or incorporating node attributes. Investigating the impact of different energy functions and their inductive biases on the efficiency and effectiveness of hierarchy-aware sampling is crucial. A deeper investigation into the optimality of the minimal sufficient sidigraph for various graph classes would be beneficial. Developing more sophisticated sampling methods that are both efficient and accurately reflect the underlying graph structure is also important. Finally, applying these techniques to real-world, large-scale hierarchical datasets and assessing the scalability and performance gains would provide further validation and practical insights.

More visual insights#

More on figures

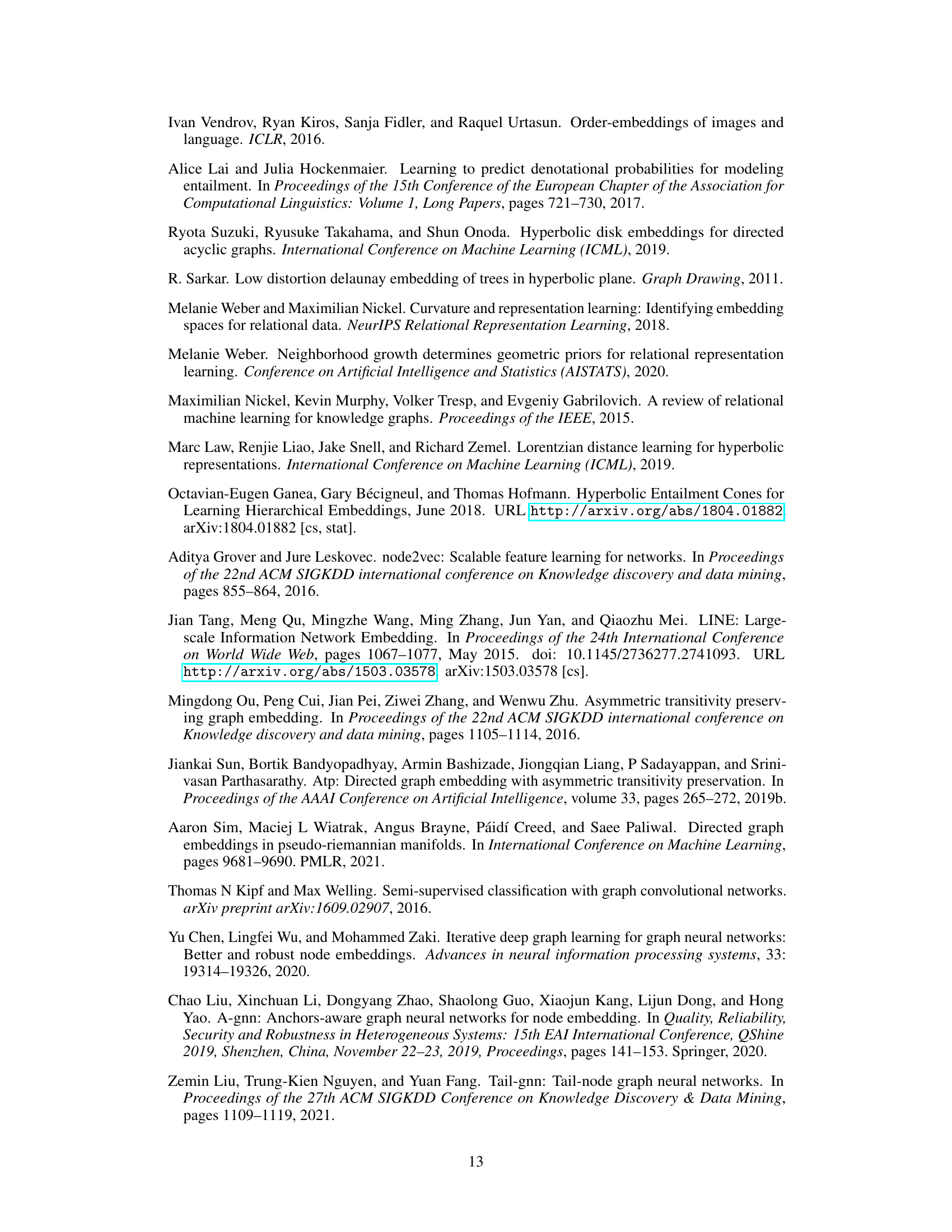

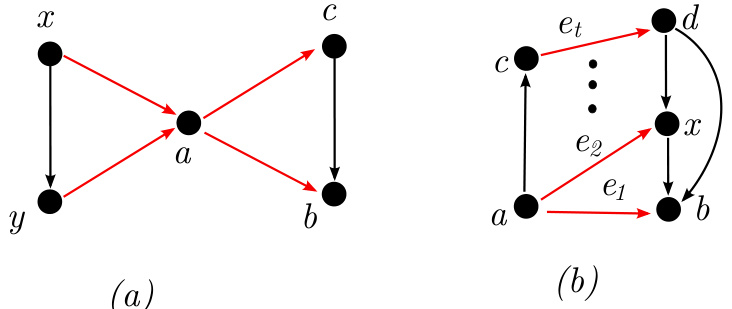

This figure illustrates Proposition 2, which states conditions under which negative edges can be removed from a transitively closed digraph while maintaining the ability to uniquely distinguish the graph. The left side shows a digraph with two negative edges (red dashed arrows). The right side shows that if there’s a positive edge (black arrow) from the tail of one negative edge to the head of another (and vice versa), the negative edge between those same nodes can be removed (as indicated by the removal of one of the red dashed edges). This pruning operation preserves the unique representation of the graph within the class of transitively closed DAGs.

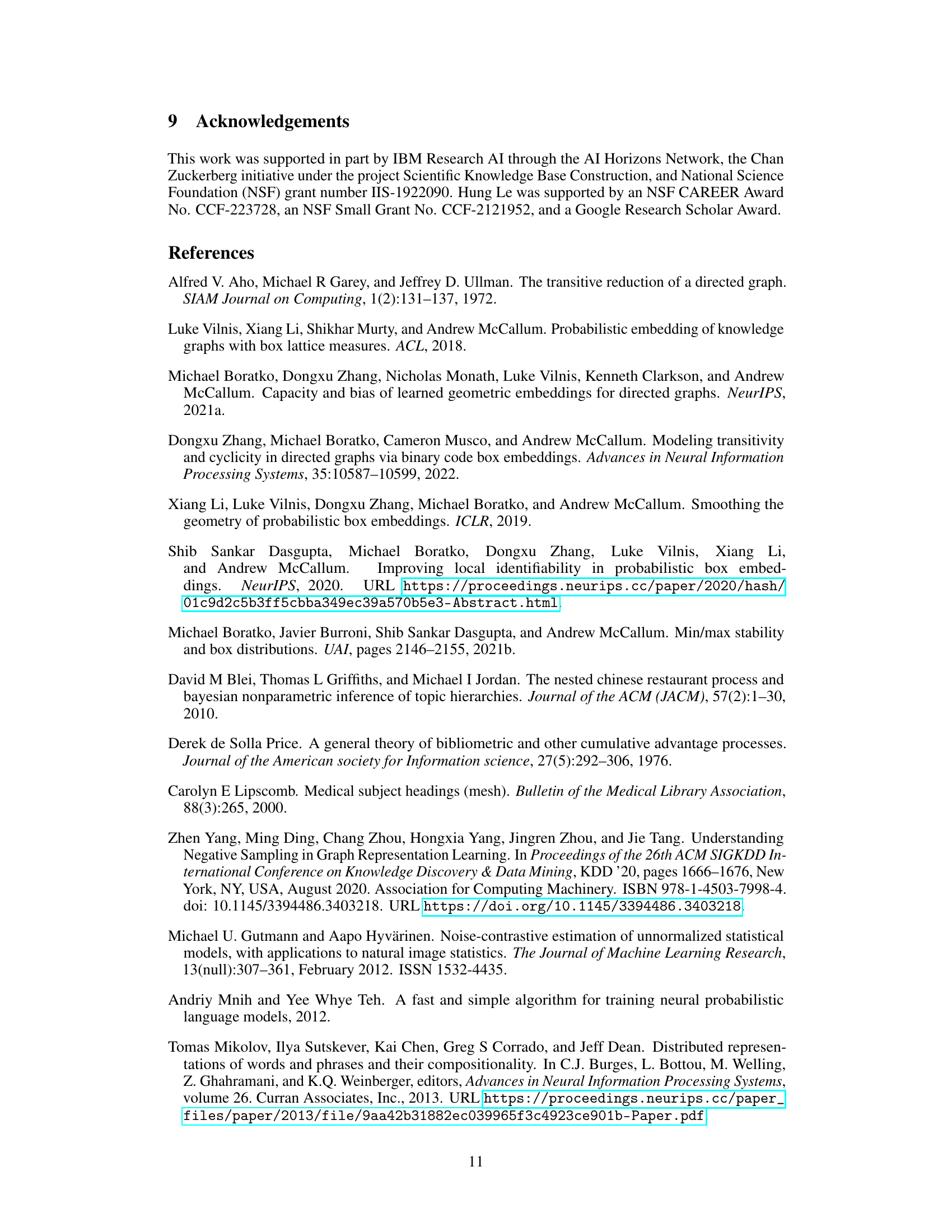

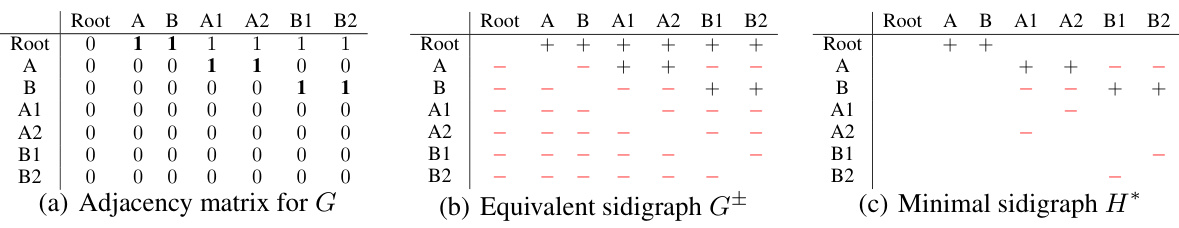

This figure shows three representations of a sample graph. The first is its adjacency matrix, the second its equivalent sidigraph, and the third its minimal sidigraph. The minimal sidigraph shows the smallest set of entries needed in the adjacency matrix to uniquely identify the graph within the set of transitively-closed DAGs.

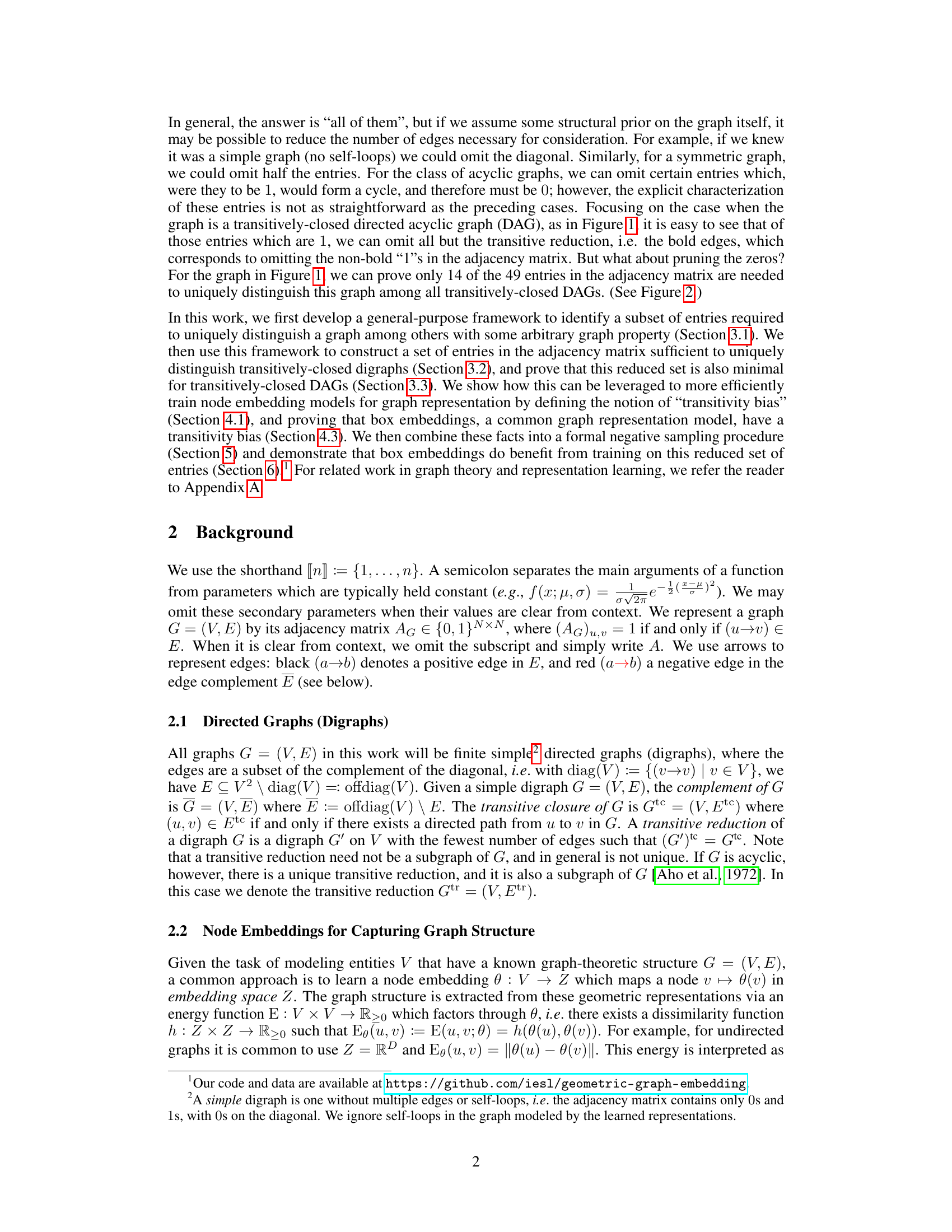

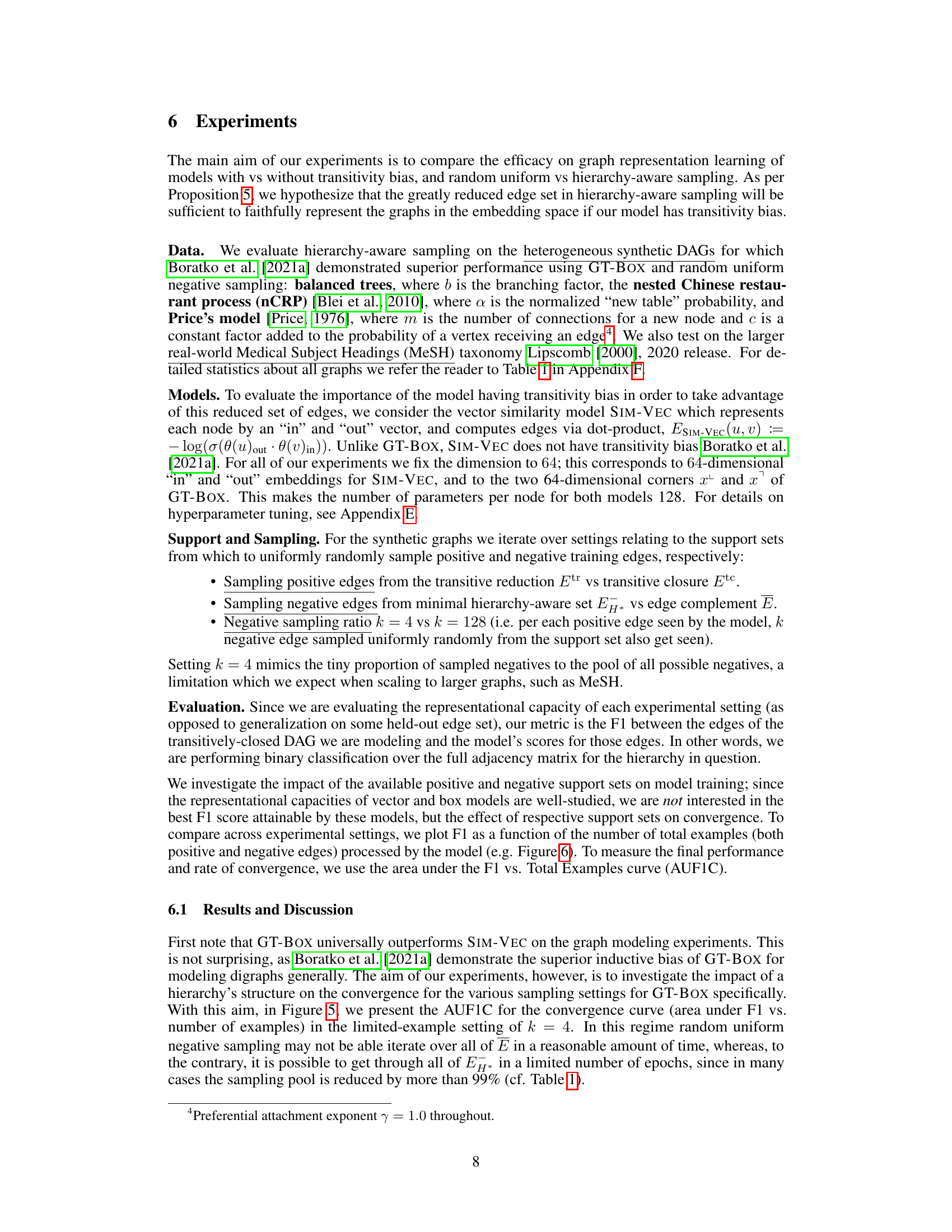

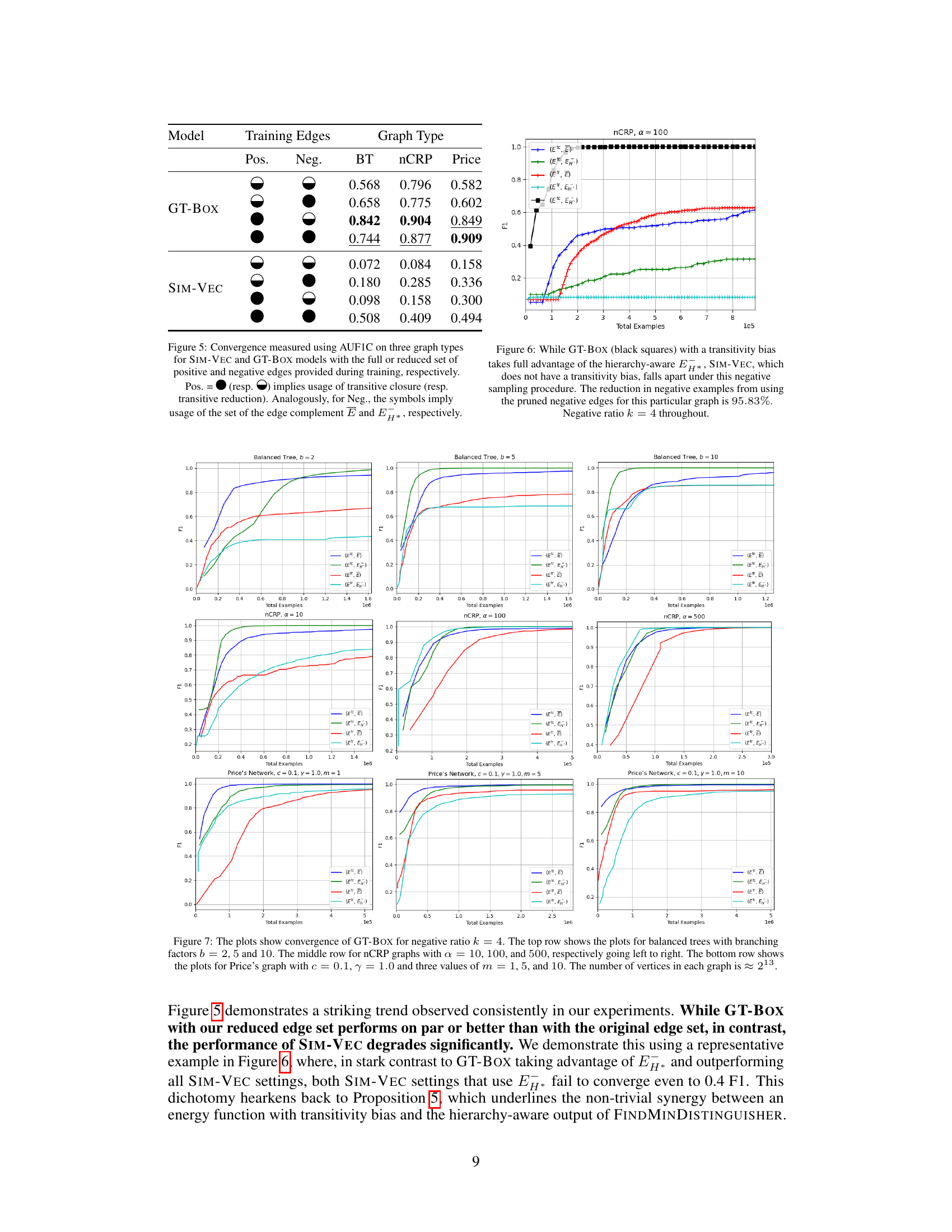

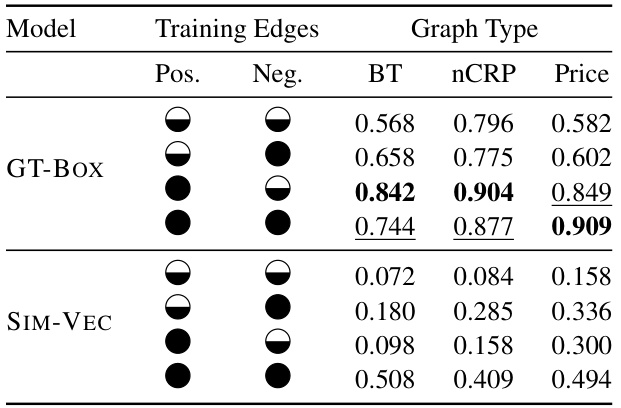

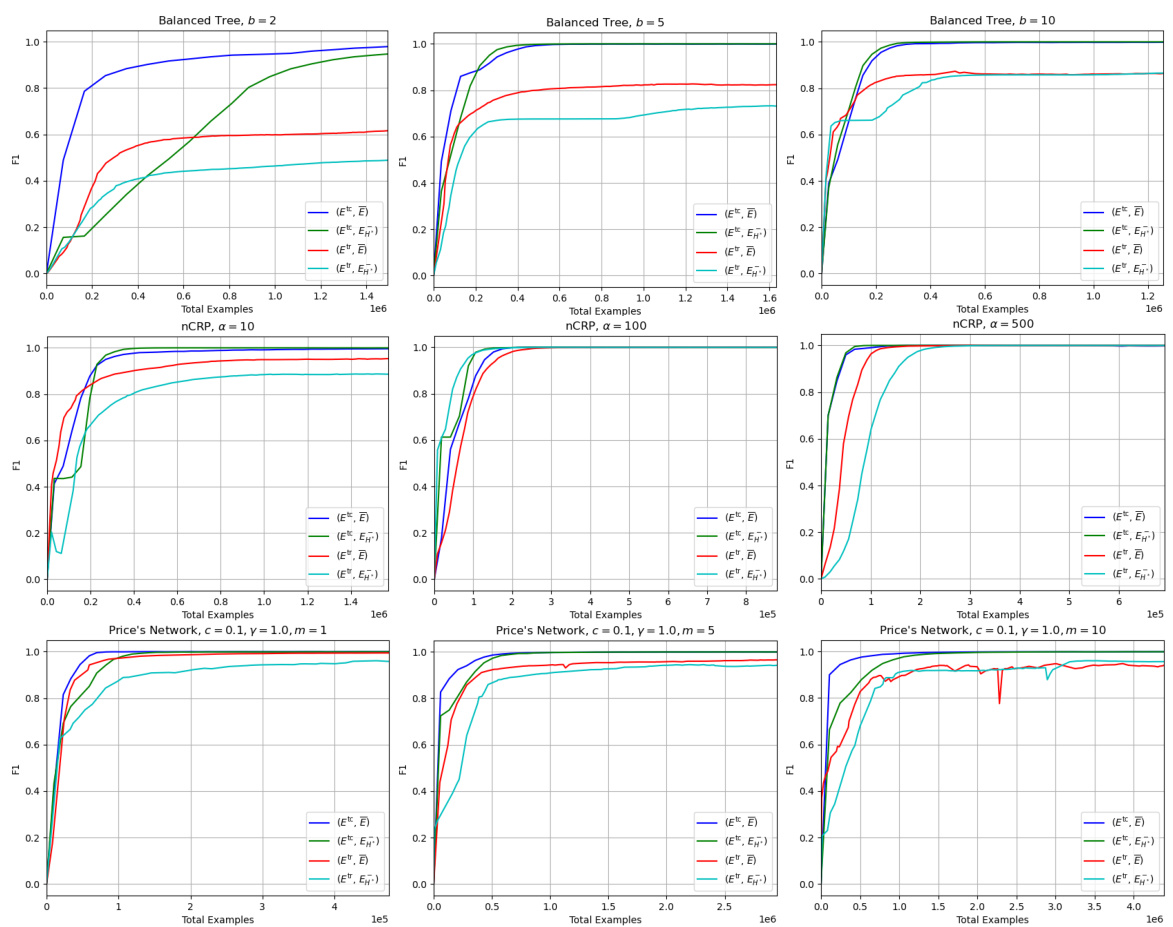

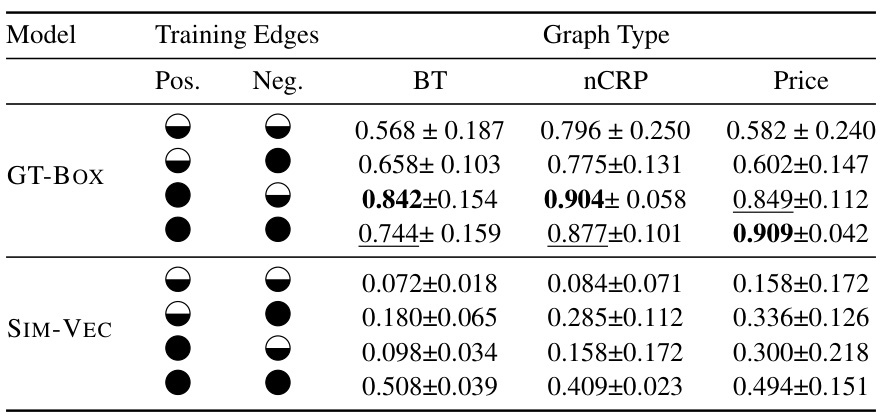

This figure compares the area under the F1 vs total examples curve (AUF1C) for SIM-VEC and GT-BOX models trained on different sets of positive and negative edges. The positive edges are sampled either from the transitive reduction (Etr) or the transitive closure (Etc) of the graph, while the negative edges are sampled from either the edge complement (E) or the minimal set of negative edges (EH*) identified by the algorithm. The results demonstrate that using the reduced set of edges (EH*) significantly improves convergence for GT-BOX, a model with transitivity bias, but harms SIM-VEC, which lacks such bias.

This figure shows an adjacency matrix of a sample graph, its equivalent sidigraph representation, and the minimal sidigraph required to uniquely identify the graph among all transitively-closed DAGs. The sidigraph uses + and - to represent positive and negative edges, respectively, providing a compact way to represent the minimal set of entries necessary for graph identification.

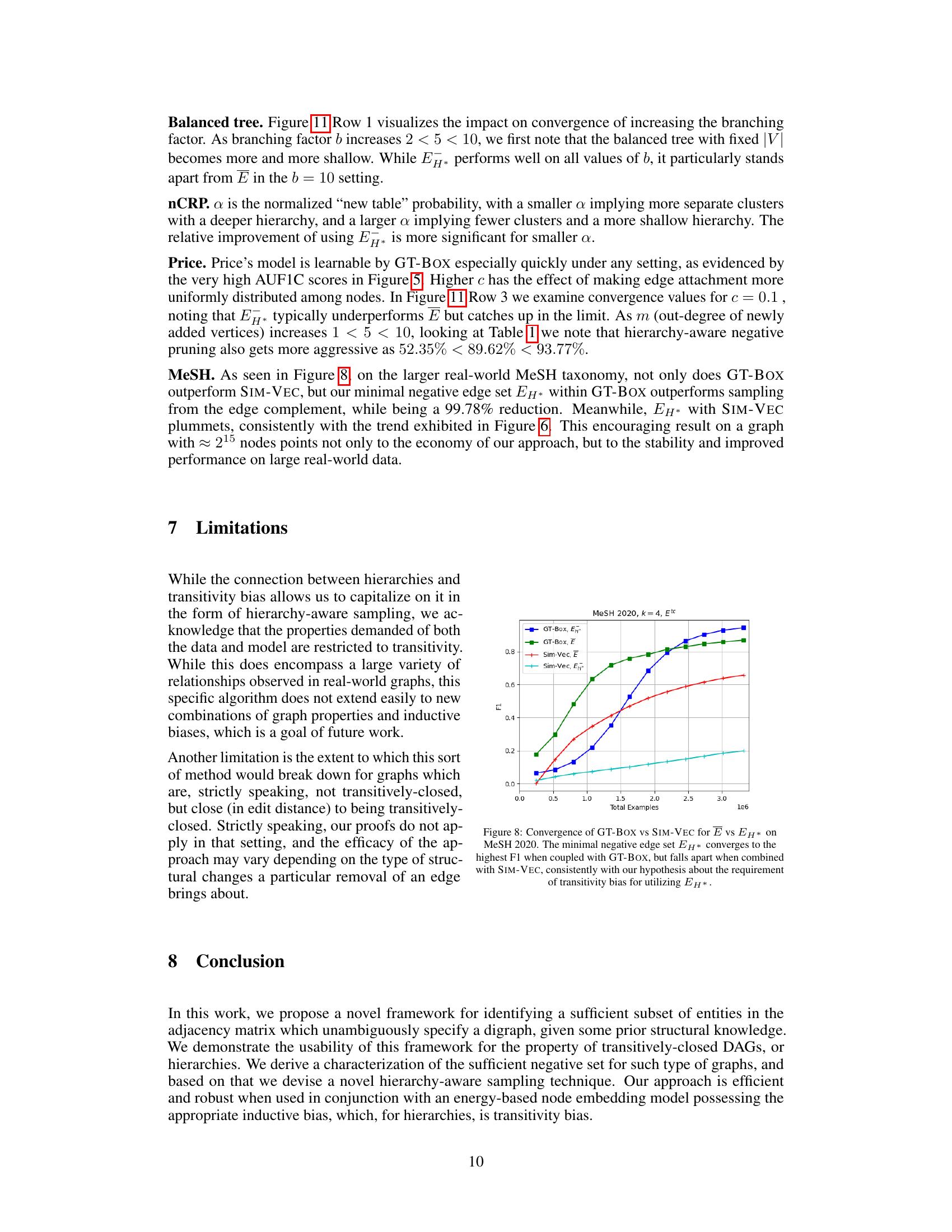

This figure compares the performance of GT-BOX and SIM-VEC models on the MeSH 2020 dataset with k=4 and using only the transitive closure for positive edges. The key difference is that GT-BOX leverages transitivity bias, while SIM-VEC does not. The results show that GT-BOX effectively uses the hierarchy-aware negative sampling (EH*) with a 95.83% reduction in the number of negative examples, demonstrating significant improvements in convergence and accuracy. In contrast, SIM-VEC’s performance degrades when using this reduced negative sample set.

This figure illustrates two scenarios where negative edges can be removed from a transitively closed DAG while still maintaining the ability to uniquely distinguish the graph among all transitively closed DAGs. Proposition 2 formally describes these pruning rules. In (a), if (a→b) and (a→d) are positive edges, and (b→d) is a negative edge, then (b→d) can be removed. Similarly in (b), if (a→d) is a positive edge, (c→d) is a positive edge and (a→c) is a negative edge, then (a→c) can be removed.

This figure shows three representations of the same transitively-closed DAG. (a) is the adjacency matrix of the graph, with 1 denoting an edge and 0 denoting no edge. (b) is the equivalent sidigraph, using + for positive edges (present in the graph) and - for negative edges (absent in the graph). This representation explicitly highlights the edges required for uniquely identifying the graph. Finally, (c) depicts the minimal sidigraph H*, which includes only a subset of the edges necessary to uniquely identify the graph among other transitively-closed DAGs. This minimal representation underlines the effectiveness of focusing on a subset of edges during model training.

This figure shows an adjacency matrix of a graph, its equivalent sidigraph representation, and the minimal sidigraph needed to uniquely identify the graph amongst all transitively-closed DAGs. The sidigraph uses + and - to represent the positive and negative edges respectively, while the minimal sidigraph highlights the smallest set of entries required for unique identification.

More on tables

This table presents the results of Area Under F1 vs. Total Examples Curve (AUF1C) for three different graph types (Balanced Tree, nCRP, Price’s Network) using two different models (SIM-VEC and GT-BOX). It shows the effect of using either the full set of positive and negative edges or a reduced set for training. The reduced set leverages transitive reduction (Etr) for positive edges and a minimal set (EH*) of negative edges derived using the proposed hierarchy-aware sampling approach. The table demonstrates how the choice of training edges affects the convergence and performance of each model.

This table presents statistics for synthetic transitively-closed directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) used in the experiments of the paper. It shows the number of vertices (|V|), edges (|E|), edges in the transitive closure (|Etc|), edges in the transitive reduction (|Etr|), edges in the complement (|E|), edges in the minimal distinguishing sidigraph (|EH*|), and the ratios of |E|/|Etc|, 1-|Etr|/|Etc|, and 1-|EH*|/|E|. The data is separated into graphs generated by different models: Balanced Tree, nCRP, and Price. The table also includes statistics for a real-world dataset, MeSH 2020. For stochastic graph generators (nCRP and Price), the statistics are averaged over 10 random seeds.

Full paper#