TL;DR#

Best-arm identification (BAI) aims to efficiently find the arm with the highest expected reward. Most BAI research focuses on the frequentist setting, assuming a fixed, pre-determined reward distribution. However, real-world applications often benefit from incorporating prior knowledge through a Bayesian approach, where the reward distribution is treated as a random variable. This paper investigates the fixed-confidence best-arm identification (FC-BAI) problem within the Bayesian framework, highlighting a critical gap in existing research.

This research demonstrates that frequentist algorithms are suboptimal in Bayesian FC-BAI. The authors derive a new lower bound for the expected number of samples and propose a novel algorithm—a modified successive elimination with an early stopping criterion—that matches this lower bound up to a logarithmic factor. This new algorithm offers significantly improved sample efficiency compared to existing frequentist methods in Bayesian settings, showcasing the benefits of explicitly considering prior information.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in Bayesian optimization and best-arm identification. It highlights the limitations of frequentist approaches in Bayesian settings and provides a novel algorithm that’s near-optimal for the fixed-confidence best-arm identification problem. This opens new avenues for improving the efficiency and accuracy of Bayesian decision-making algorithms in various applications.

Visual Insights#

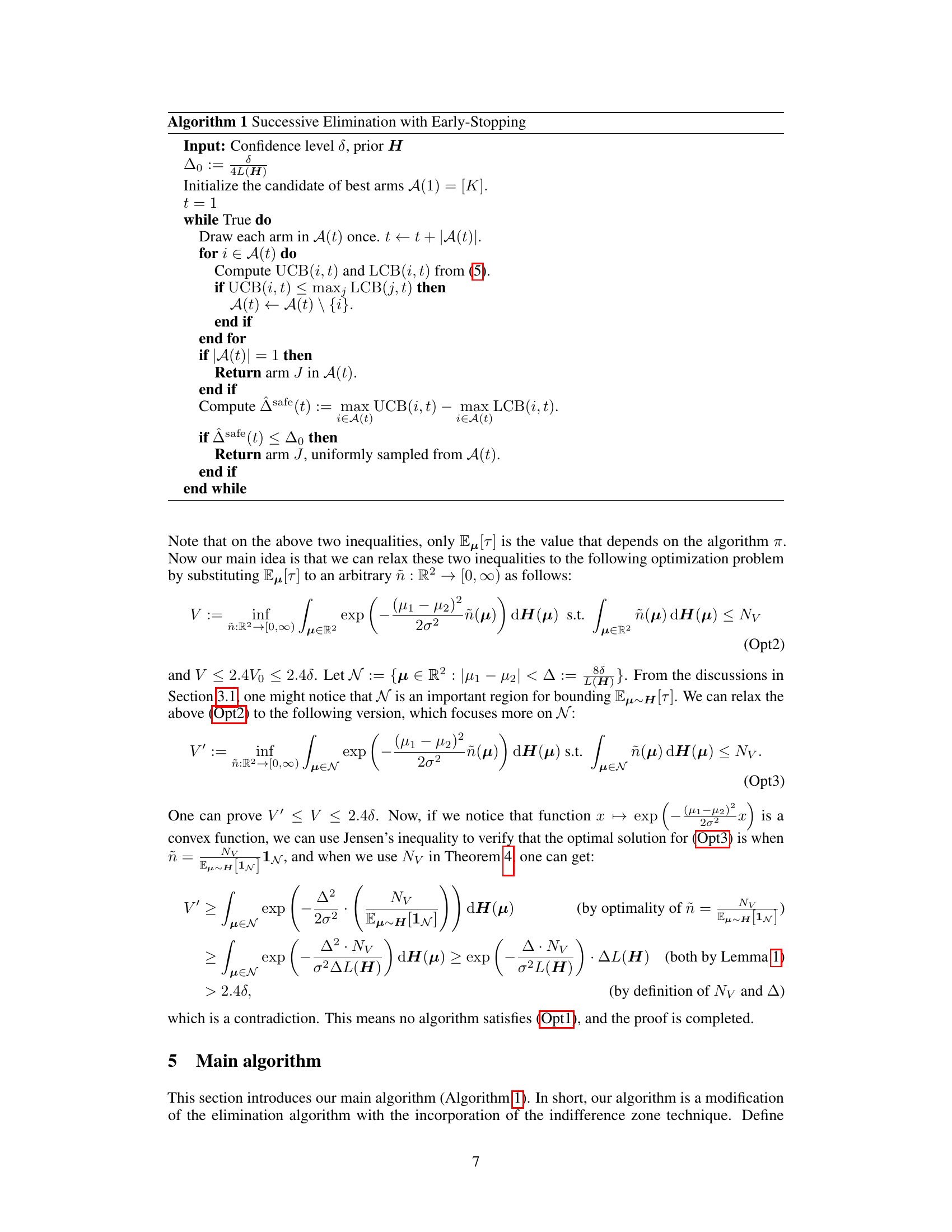

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the average and maximum stopping times, as well as the error rate, for three different best arm identification algorithms: Algorithm 1 (the proposed algorithm in the paper), TTTS (Top-Two Thompson Sampling), and TTUCB (Top-Two Upper Confidence Bound). The results demonstrate that Algorithm 1 significantly outperforms the other two frequentist algorithms, especially in terms of the maximum stopping time.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of two top-two algorithms and Algorithm 1.

In-depth insights#

Bayesian FC-BAI#

Bayesian Fixed-Confidence Best Arm Identification (FC-BAI) presents a unique approach to the multi-armed bandit problem. Unlike frequentist methods, which assume a fixed, pre-determined model, Bayesian FC-BAI incorporates prior knowledge about the arms’ distributions through a Bayesian prior. This allows for more efficient exploration and exploitation, particularly when dealing with low suboptimality gaps between arms where traditional methods struggle. The Bayesian setting allows the algorithm to make better-informed decisions by leveraging prior information and update beliefs as more data is collected. A key challenge is to determine the optimal sampling strategy to minimize the expected number of samples needed to identify the best arm with a fixed level of confidence. This is complicated by the influence of the prior distribution on sample complexity. The theoretical analysis of Bayesian FC-BAI often involves concepts like volume lemma and KL-divergence to provide rigorous bounds on sample complexity and error probability. Simulation studies are crucial to verify these theoretical findings and compare the performance of Bayesian FC-BAI to frequentist counterparts. The development of efficient algorithms that fully exploit the prior information for Bayesian FC-BAI remains an active research area.

Frequentist Limits#

The heading ‘Frequentist Limits’ suggests an analysis of the limitations of frequentist methods when applied to Bayesian best-arm identification problems. A frequentist approach assumes a fixed, unknown data-generating process, while Bayesian methods incorporate prior knowledge about the process. The discussion likely explores how traditional frequentist algorithms, designed for worst-case scenarios, perform poorly when prior information exists, potentially showing suboptimal sample complexity or failure to converge. This section would likely highlight how Bayesian methods offer improved efficiency and accuracy by leveraging prior beliefs. The analysis might involve theoretical bounds, demonstrating the inherent limitations of frequentist approaches in scenarios where Bayesian inference is more natural. It will likely conclude with a strong argument for the superiority of Bayesian techniques in these scenarios, setting the stage for the introduction of a new Bayesian approach or a modified frequentist approach that acknowledges the available prior information.

Lower Bound Proof#

The Lower Bound Proof section of a Bayesian best-arm identification paper would rigorously demonstrate a fundamental limit on the performance of any algorithm solving this problem. It would establish a theoretical lower bound on the expected number of samples needed to identify the best arm with a given confidence level, considering the prior distribution over the arm parameters. This proof would likely leverage information-theoretic arguments, possibly using techniques like Fano’s inequality or related methods, to show that no algorithm can perform better than the established lower bound. The key insight here is quantifying the inherent difficulty of the problem based on the properties of the prior, demonstrating that algorithms which are optimal in a frequentist setting may perform poorly in a Bayesian setting where prior information is available. A successful lower bound proof would be a crucial contribution, providing a benchmark against which to evaluate the efficiency of proposed algorithms and highlighting the unique challenges posed by the Bayesian framework. The proof’s complexity would likely depend on the assumptions made about the prior distribution and the reward distributions, potentially requiring advanced mathematical tools from information theory and probability.

Novel Algorithm#

The heading ‘Novel Algorithm’ suggests a research paper section detailing a newly developed algorithm. A thoughtful analysis would delve into the algorithm’s core functionality, its novelty compared to existing methods, and its performance characteristics. Key aspects to consider include: the algorithm’s design principles (e.g., is it a greedy approach, a dynamic programming solution, or something else?), its computational complexity (e.g., time and space requirements), and how it addresses limitations of prior algorithms. The section should also highlight empirical evidence of the algorithm’s superiority, possibly including comparative performance results on benchmark datasets or real-world applications. Robustness and generalizability are also critical aspects to examine: how well does the algorithm perform under various conditions, including noisy data or different problem instances? Finally, the paper should discuss the algorithm’s potential impact and applications, establishing its significance in solving practical problems.

Future Work#

The authors propose several avenues for future research. Tightening the logarithmic gap between the upper and lower bounds on the sample complexity is a crucial next step to fully understand the algorithm’s efficiency. Extending the analysis to bandit models beyond the Gaussian assumption, encompassing general exponential families, is essential for broader applicability. Developing a robust algorithm less sensitive to prior misspecification would significantly enhance its practical use. Finally, investigating the performance and adaptability of the early-stopping and elimination strategies in other BAI settings, particularly the fixed-budget scenario, could lead to valuable insights and potentially more efficient algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on tables

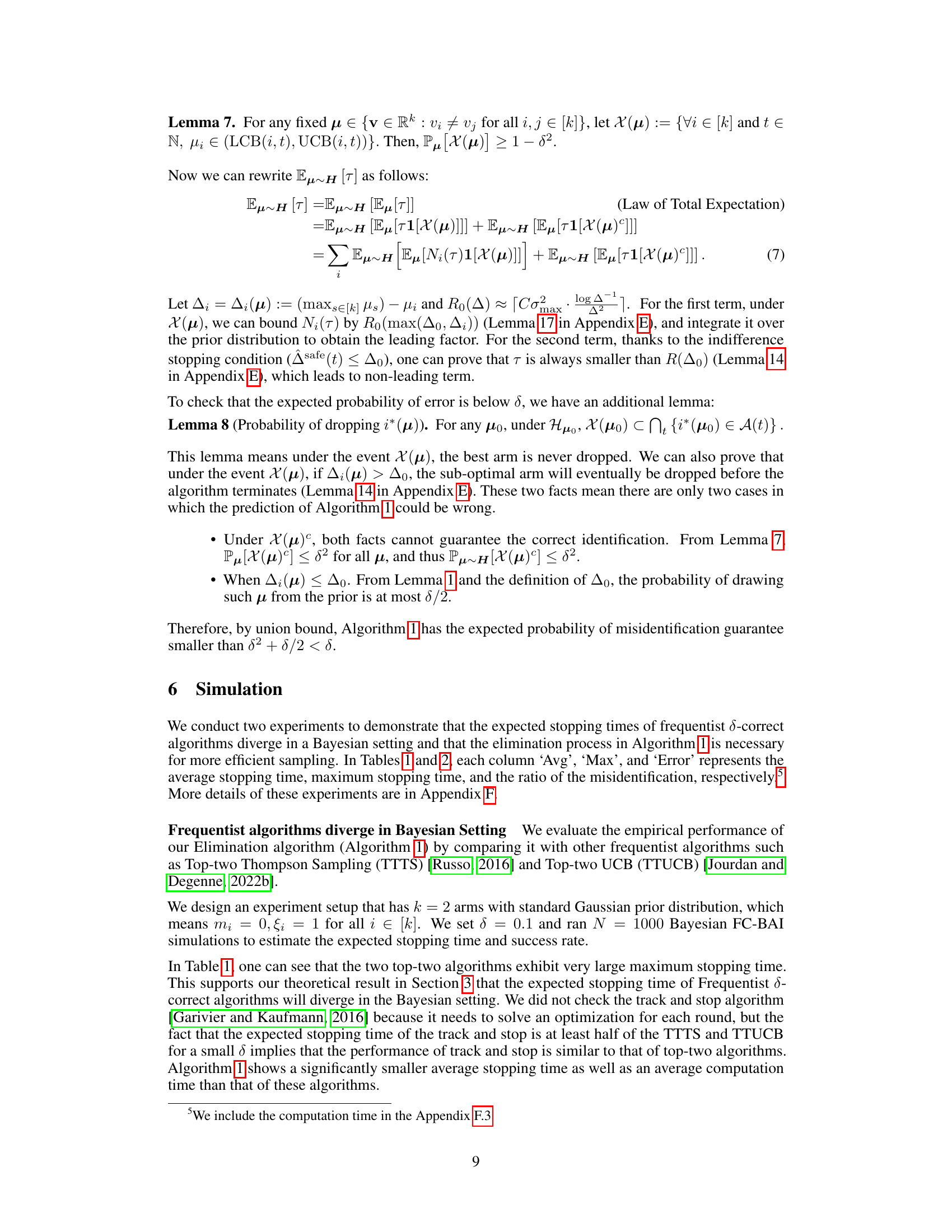

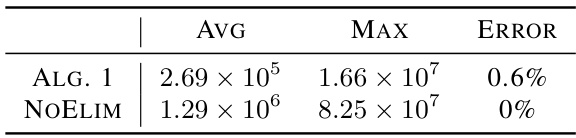

🔼 This table compares the performance of Algorithm 1 (Successive Elimination with Early Stopping) and its modification without the elimination process (NoElim). The comparison focuses on the average (AVG) and maximum (MAX) stopping times, and the error rate (ERROR) of each algorithm. The error rate represents the percentage of times the algorithm fails to correctly identify the best arm. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the elimination process in Algorithm 1, resulting in significantly reduced stopping times with comparable error rates.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of Algorithm 1 and the no-elimination version of it.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Algorithm 1 (the proposed algorithm) against two existing top-two algorithms (TTTS and TTUCB) in a Bayesian setting for best arm identification. The comparison focuses on the average and maximum stopping times, as well as the error rate (misidentification). The results demonstrate that the traditional frequentist approaches (TTTS and TTUCB) have significantly larger stopping times, especially the maximum stopping times, compared to Algorithm 1. This highlights the advantage of the proposed Bayesian approach for this problem.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of two top-two algorithms and Algorithm 1.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Algorithm 1 (the proposed algorithm) against two existing top-two algorithms (TTTS and TTUCB) in terms of average stopping time, maximum stopping time, and error rate. The results demonstrate that Algorithm 1 is significantly more efficient in terms of the number of samples required to achieve the desired confidence level. The high maximum stopping times for TTTS and TTUCB highlight their inefficiency in the Bayesian setting.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of two top-two algorithms and Algorithm 1.

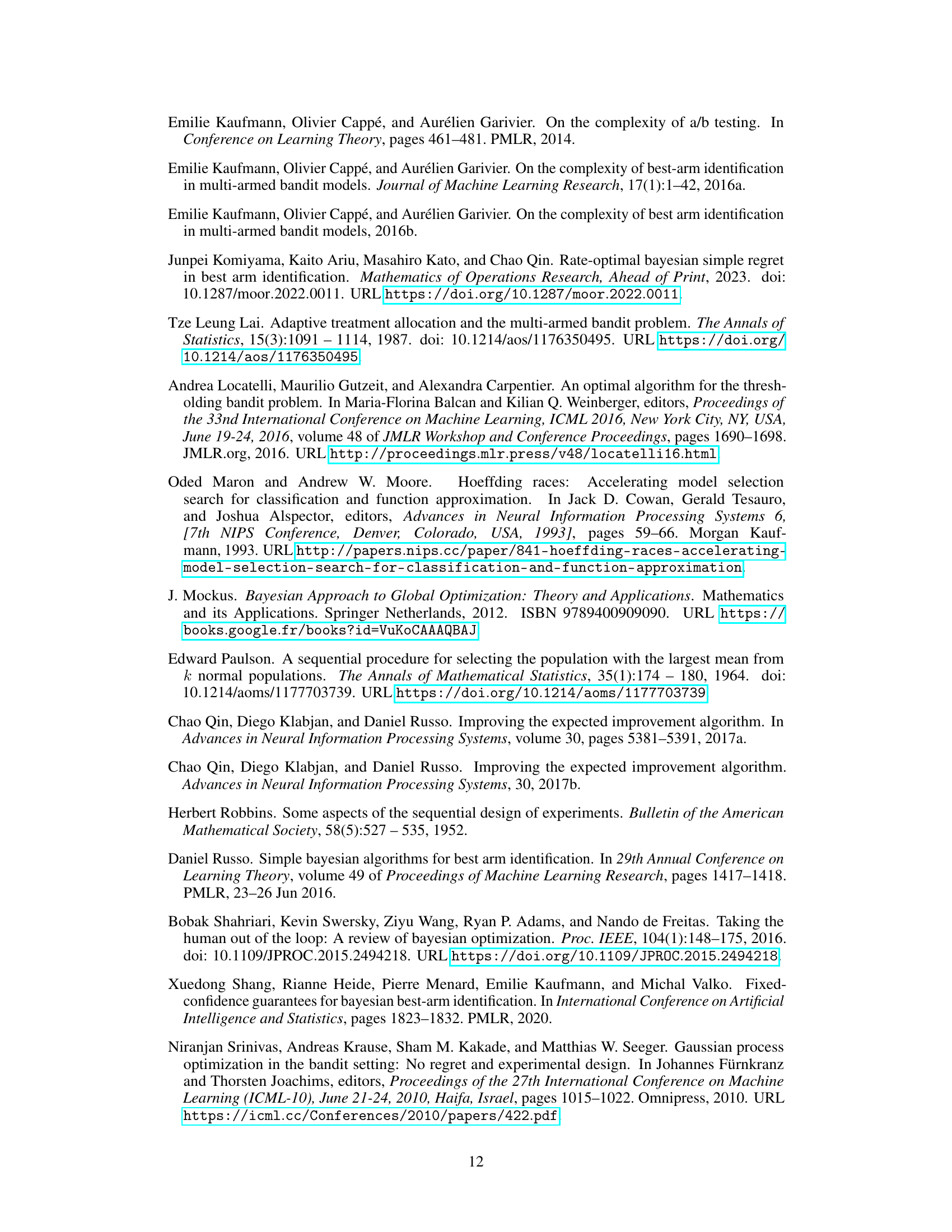

🔼 This table compares the performance of Algorithm 1 and TTUCB in a Bayesian setting with 10 arms. The average and maximum stopping times, error rate, and computation time are shown. Note that TTUCB’s maximum stopping time is capped at 108 due to time constraints.

read the caption

Table 8: Multiple arms.

Full paper#