↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for modeling group actions primarily focus on the data space. This approach is limited as many real-world scenarios involve group actions affecting underlying latent factors, rather than directly on observable data. For example, consider modeling the rotation of a partially occluded object: the rotation affects the latent representation of the object, but the observed image shows only partial information due to occlusion. This limitation has not been fully addressed by previous work.

This paper introduces a new method that directly models group actions within the latent space. This approach enables greater flexibility in encoder/decoder architectures and handles a broader range of scenarios, including those with latent group actions. Through extensive experiments on image datasets with different group actions, they show that their approach significantly outperforms existing methods. The theoretical analysis proves that modeling group actions in the latent space is a generalization of existing data-space methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to model group actions in autoencoders, addressing limitations of existing methods. It offers a more flexible and versatile model capable of learning a wider range of real-world scenarios where groups act on latent factors. The theoretical analysis and superior performance on diverse datasets demonstrate its significance and open new avenues for future research in representation learning and generative modeling. This work is particularly relevant to researchers interested in applications involving symmetries, geometric transformations, and deep learning.

Visual Insights#

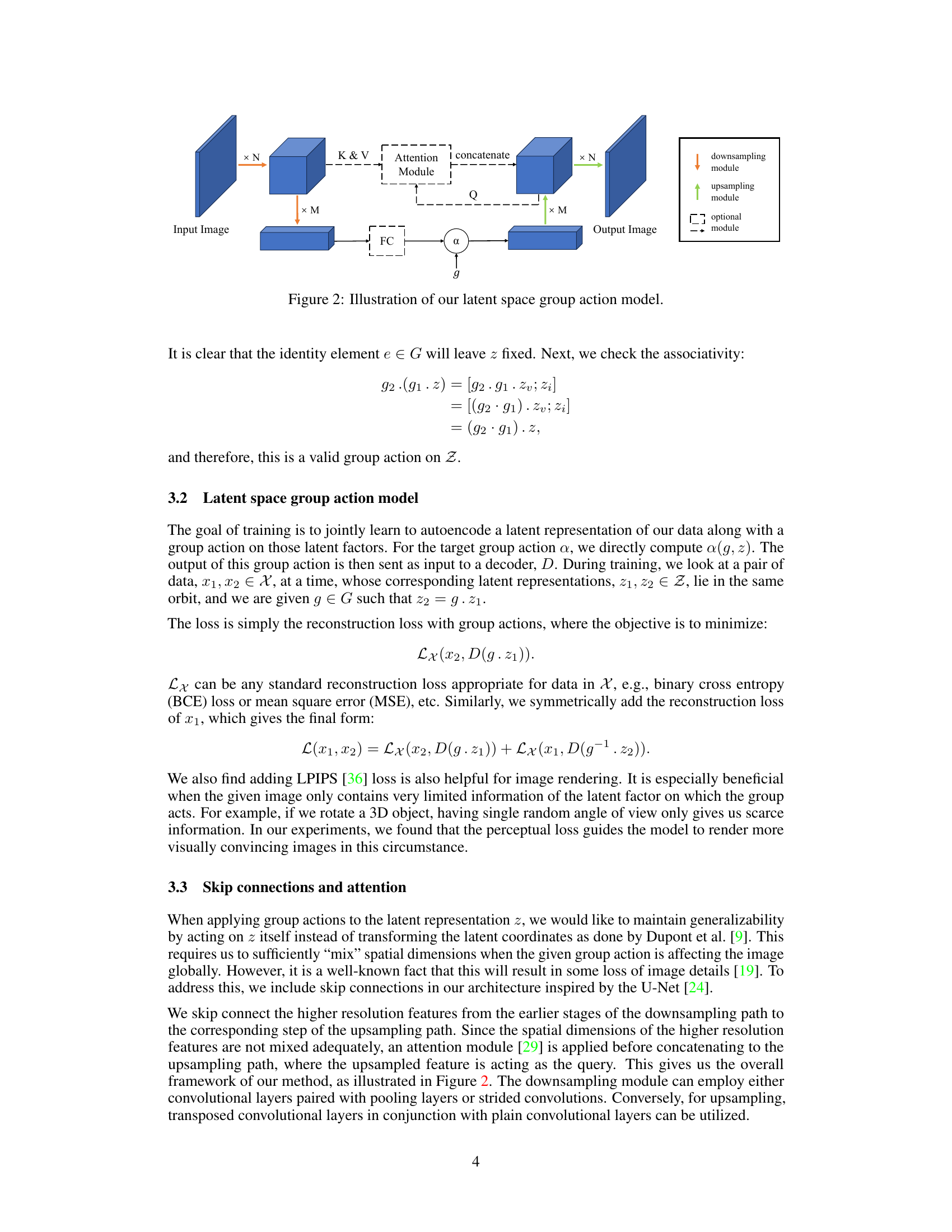

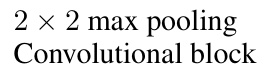

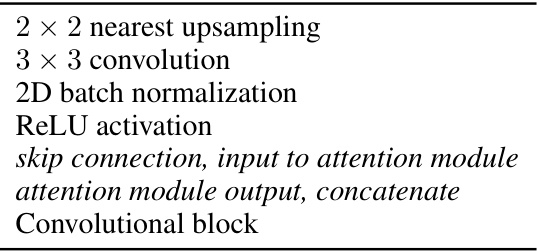

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed latent space group action model. The model consists of an encoder, an attention module, a group action module, and a decoder. The encoder takes an input image and encodes it into a latent representation. The attention module processes the latent representation and generates query, key and value vectors. The group action module applies a group action to the latent representation. Finally, the decoder takes the modified latent representation and generates the output image.

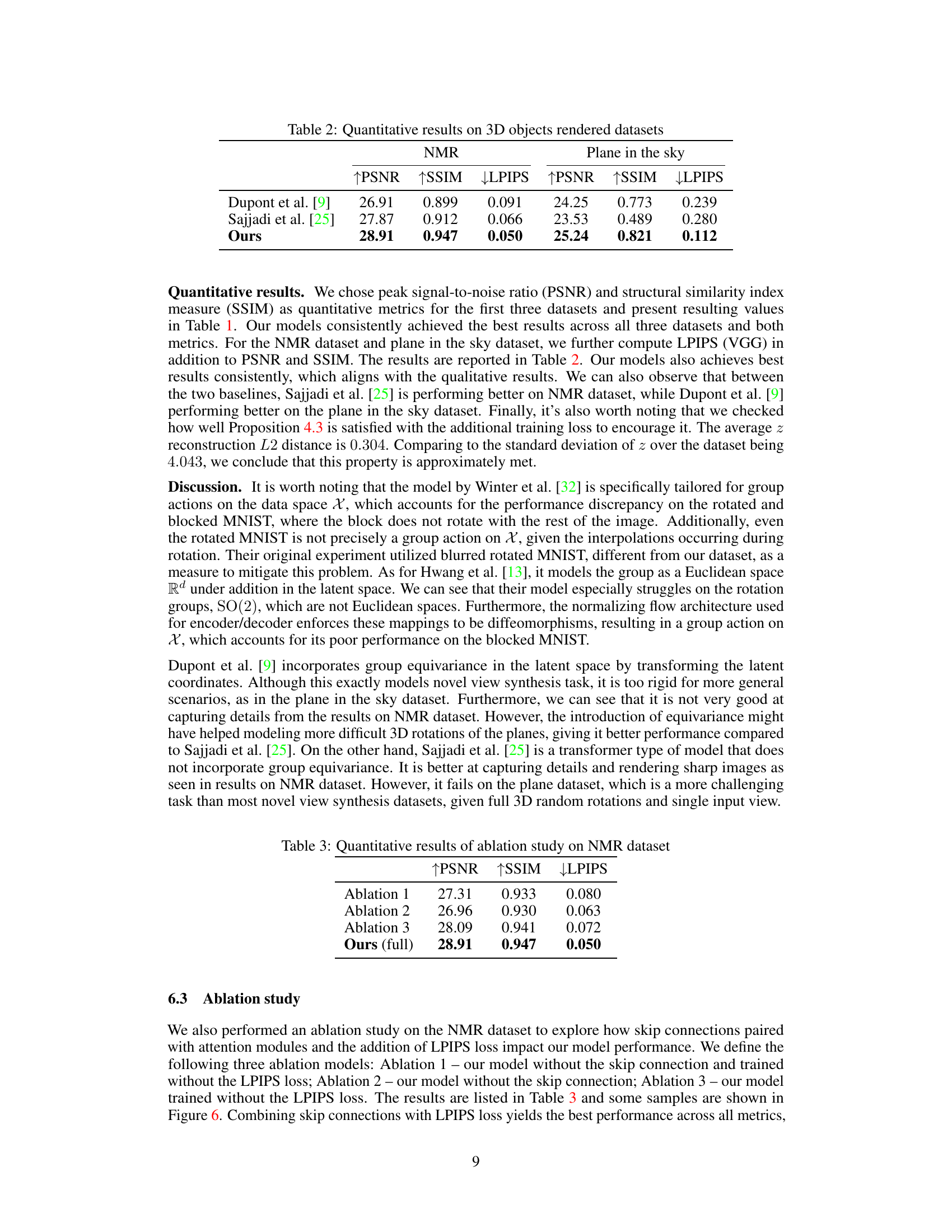

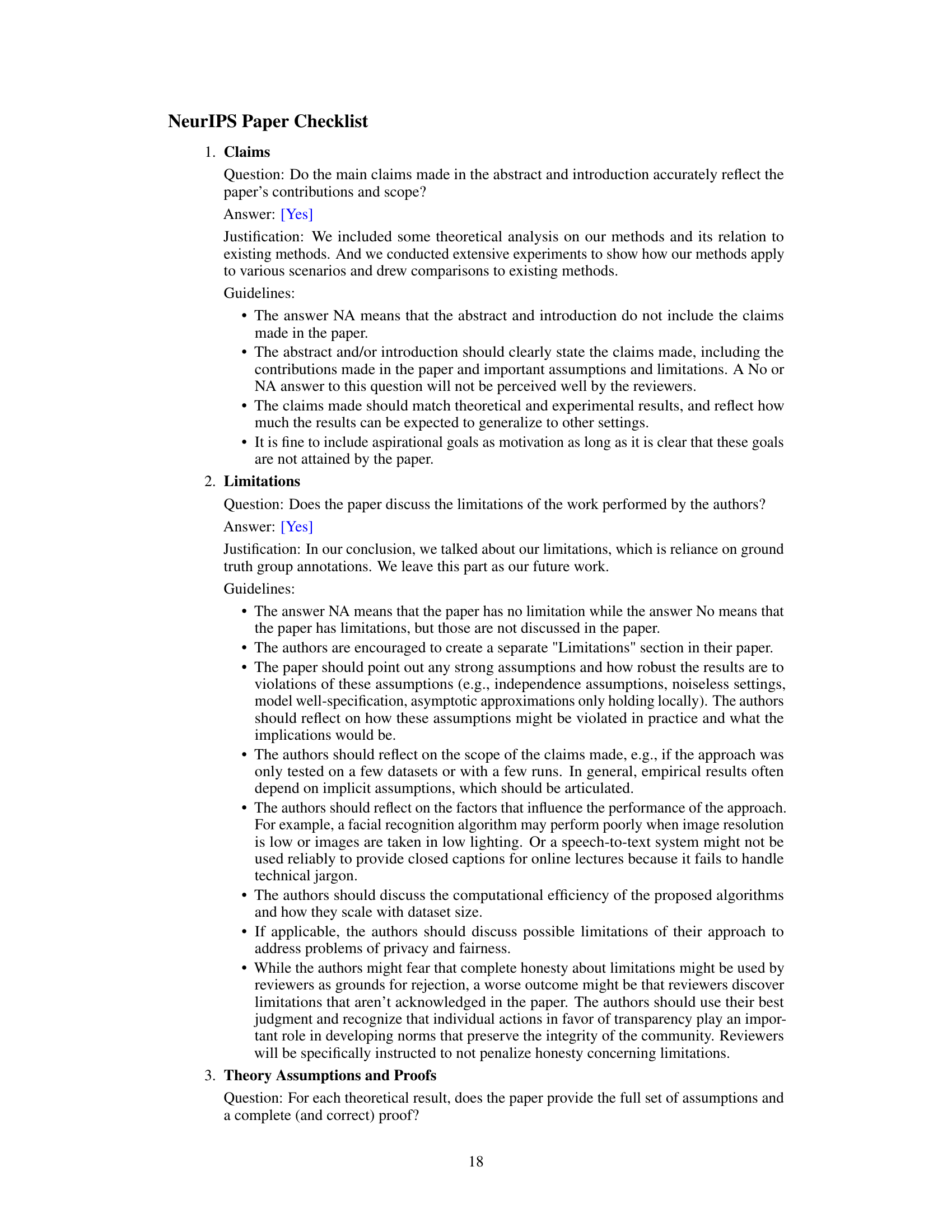

This table presents a comparison of the quantitative results obtained using different methods on three datasets: Rotated MNIST, Rotated and Blocked MNIST, and Brain MRI. The metrics used for comparison are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM). The methods compared include those proposed by Winter et al. [32], Hwang et al. [13], and the authors’ proposed method.

In-depth insights#

Latent Group Actions#

The concept of ‘Latent Group Actions’ in a research paper likely explores how group symmetries or transformations affect the underlying, unobserved (latent) structure of data, rather than directly manipulating the observed data itself. This approach is powerful because it allows modeling scenarios where group actions aren’t directly visible, such as in images with occlusions or in analyzing the latent factors influencing 3D object rotations. A key advantage is the flexibility in encoder-decoder architectures, as the method doesn’t require group-specific layers. The research would likely demonstrate that this latent space approach is a generalization of methods that directly model group actions on data, showing it capable of learning both types of actions. This would be supported by theoretical analysis and experimental results showcasing superior performance on image datasets with diverse group actions.

Autoencoder Framework#

An autoencoder framework is a powerful machine learning technique particularly well-suited for tasks involving learning latent representations from data. The core idea is to learn a compressed encoding of the input data and then reconstruct the original input from this encoding. This process helps in identifying the most important features or latent variables in the data, effectively reducing dimensionality and noise. In the context of group actions, an autoencoder framework allows for the modeling of group symmetries and transformations directly within the latent space, or indirectly via the data space. This offers significant advantages for tasks where group actions are crucial, for example, object recognition under different rotations or generative modeling of objects with inherent symmetries. The latent representation learned by the autoencoder acts as a meaningful intermediate representation on which group actions are defined. The flexibility of the encoder and decoder architectures within the autoencoder framework ensures adaptability to various data types and group actions, while also allowing the use of advanced deep learning techniques for improved performance. A key challenge when using this framework is the design of effective loss functions that accurately reflect the group action structure and ensure the preservation of key information during the compression and reconstruction process.

Group-Invariant Factors#

The concept of ‘Group-Invariant Factors’ within a research paper likely refers to elements or features of data that remain unchanged despite transformations by a group action. Identifying these invariant factors is crucial because they represent underlying properties unaffected by specific group operations, offering a more fundamental understanding of the data’s structure. This could be particularly useful in scenarios involving image analysis (e.g., rotation invariance), where the underlying object remains consistent, even when its representation changes. These invariants may serve as a basis for robust feature extraction, leading to more stable and reliable models that generalize better across various transformed data instances. The investigation might involve exploring different mathematical representations to capture the essence of these invariant properties, perhaps through group representation theory, leading to methods for effective dimension reduction or model simplification. The significance of this concept also lies in its potential application for disentangled representation learning, enabling models to learn representations that are explicitly separated into invariant and variant parts, improving interpretability and facilitating downstream tasks. This approach promises to contribute significantly to fields such as computer vision, machine learning, and signal processing.

Image Data Modeling#

Image data modeling is a crucial aspect of computer vision, focusing on representing and manipulating images effectively. Successful models must capture the complex interplay of visual features, such as color, texture, shape, and spatial relationships. Different modeling approaches exist, ranging from simple pixel-based representations to sophisticated deep learning architectures. Deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has revolutionized the field, enabling the automatic extraction of hierarchical features and achieving state-of-the-art performance in numerous tasks. However, challenges remain, including the need for massive datasets, computational cost, and the difficulty in interpreting model decisions. Furthermore, the development of models capable of handling diverse image types, variations in lighting conditions, and occlusions is an active area of research. The ultimate goal is to create robust and generalizable models that can accurately understand and reason about visual information, empowering applications in various domains.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the latent space group action model to handle more complex group structures and actions is crucial, moving beyond the SO(2), SO(3), and cyclic groups explored here. Investigating the model’s performance with diverse data modalities and group types would also be highly valuable. Developing efficient methods for automatically identifying the appropriate group and latent factor for a given dataset is a key challenge; current methods require manual selection. Furthermore, exploring the theoretical underpinnings of the model in greater depth, including formal analysis of the relationship between latent and data-space group actions, and establishing convergence guarantees under various conditions, is necessary. Finally, research into semi-supervised or unsupervised learning techniques within this framework would broaden the applicability and reduce the reliance on ground-truth group annotations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

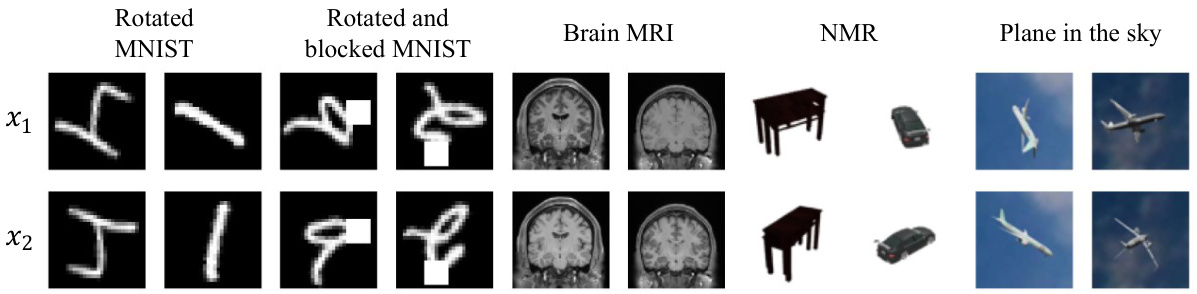

This figure shows example pairs of images from the five datasets used in the paper’s experiments. Each column represents a dataset, and each row shows a pair of images related by a group action (e.g., rotation, contrast change). The pairs demonstrate the various types of group actions that the proposed model handles. For instance, the ‘Rotated MNIST’ shows rotated images of the digit ‘7’, while ‘Rotated and blocked MNIST’ shows the same digit with an added block, demonstrating that the group action is on the digit itself, and not just the visual appearance of the image.

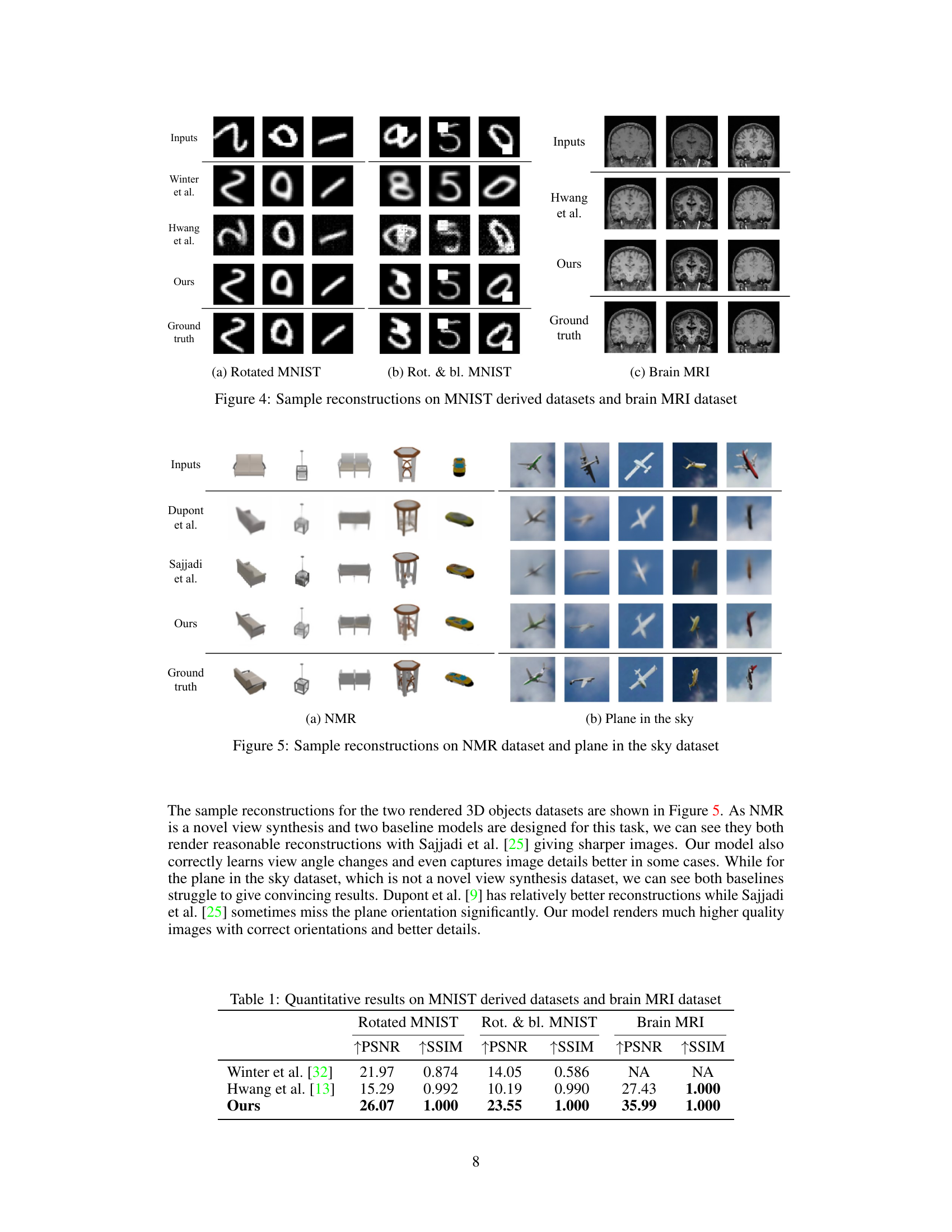

This figure shows the qualitative results of the proposed latent space group action model and two baselines (Hwang et al. and Winter et al.) on three datasets: Rotated MNIST, Rotated and blocked MNIST, and Brain MRI. For each dataset, the ‘Inputs’ row shows example input images. Subsequent rows show the reconstructions generated by each model. The ‘Ground truth’ row shows the corresponding target images. The figure demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method in generating visually accurate reconstructions, particularly in capturing finer details and dealing with occlusion (as in Rotated and blocked MNIST).

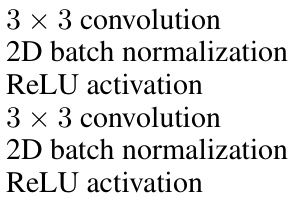

This figure shows the reconstruction results of two 3D object datasets: NMR dataset and Plane in the sky dataset. For each dataset, the input images are shown in the top row, followed by reconstruction results from three different models: Dupont et al., Sajjadi et al., and the proposed model. The ground truth images are displayed in the bottom row. The NMR dataset contains rendered 3D objects from various viewpoints, whereas the Plane in the sky dataset shows images of airplanes against a sky backdrop, under different rotations. The figure visually demonstrates the relative performance of each model on reconstructing images based on group actions in the latent space. The proposed model showcases better performance overall in terms of detail and visual fidelity.

This figure visually compares the results of different ablation studies on the 3D object rendering dataset. Each row represents a different object (gun, car, chair, airplane). The ‘Inputs’ column shows the original input image. The subsequent columns show the reconstructions generated by different model variations: * Ablation 1: Model without skip connections and LPIPS loss. * Ablation 2: Model without skip connections. * Ablation 3: Model without LPIPS loss. * Full: The complete model with skip connections and LPIPS loss. * Ground truth: The original, correctly rendered image. The figure demonstrates the impact of skip connections and LPIPS loss on reconstruction quality. The ‘Full’ model generally produces the best reconstructions, highlighting the importance of these components in achieving high-quality results.

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to disentangle invariant and varying factors in latent representations. By swapping the invariant and varying components of latent representations between two input images and decoding the results, the model generates new combinations of features. This showcases the model’s capacity to generalize to unseen combinations of factors, indicating a successful disentanglement of the latent space.

More on tables

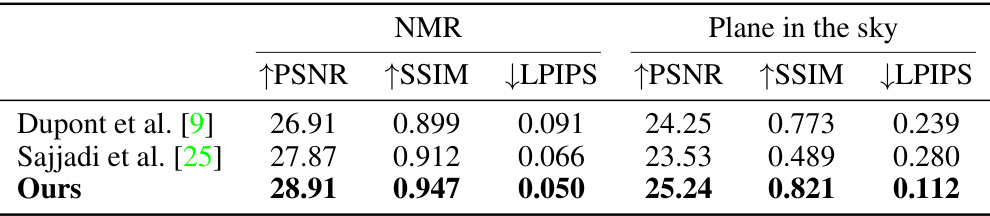

This table presents quantitative results on two 3D object rendered datasets, NMR and Plane in the sky. The metrics used are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS). The table compares the performance of three different methods: Dupont et al., Sajjadi et al., and the method proposed in the paper. Lower LPIPS values indicate better perceptual quality.

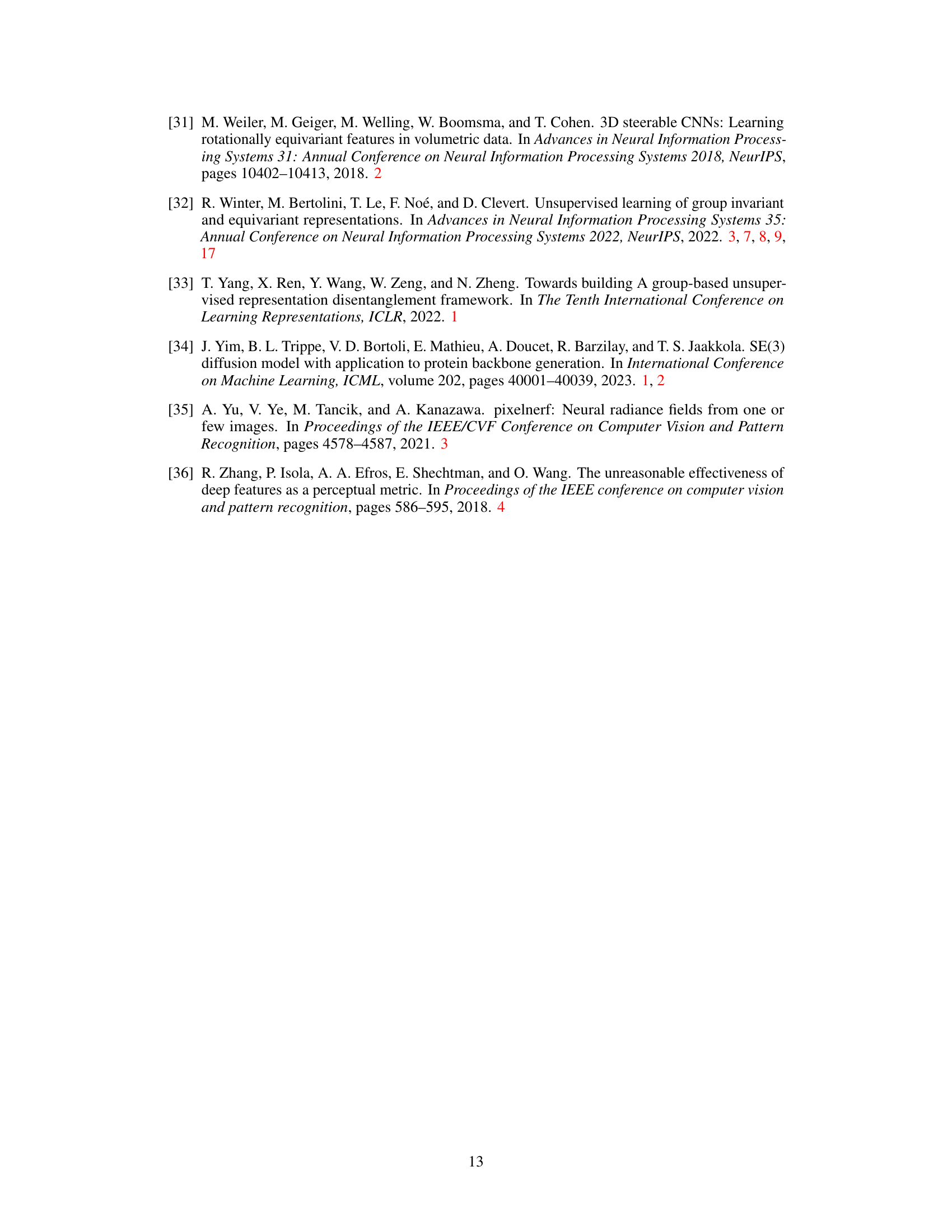

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different model configurations on the NMR dataset. It shows the impact of removing skip connections and/or the LPIPS loss on the model’s performance, as measured by PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS. The ‘Ours (full)’ row shows the performance of the complete model, which includes both skip connections and the LPIPS loss.

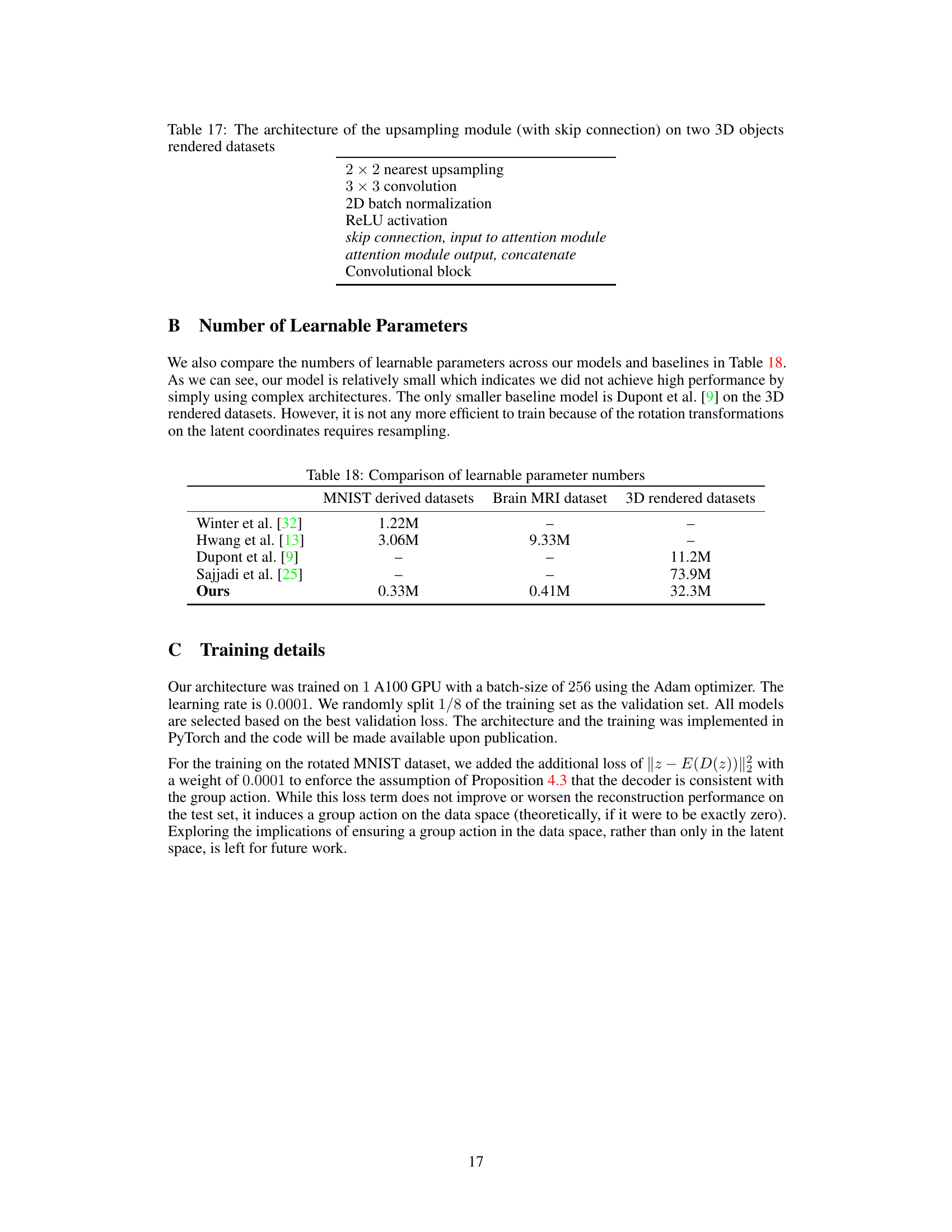

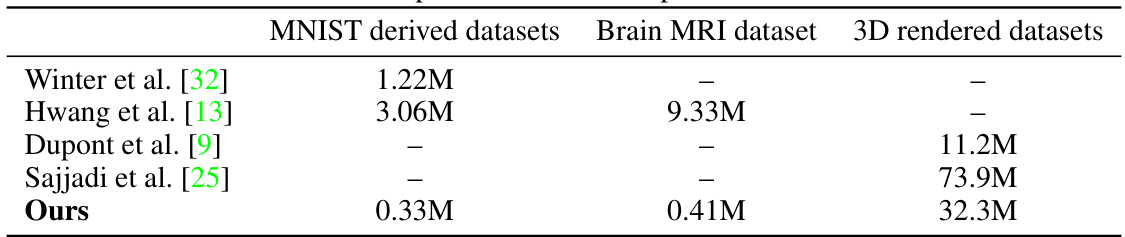

This table compares the number of learnable parameters in the proposed model and baseline models across three different datasets: MNIST-derived datasets, brain MRI dataset, and 3D object-rendered datasets. It highlights the relative efficiency of the proposed model in terms of the number of parameters.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed model’s performance against baseline models on three datasets: Rotated MNIST, Rotated and blocked MNIST, and Brain MRI. The metrics used for comparison are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM). Higher PSNR and SSIM values indicate better image reconstruction quality.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against baseline methods on three datasets: Rotated MNIST, Rotated and Blocked MNIST, and Brain MRI. The metrics used for comparison are PSNR and SSIM. The table shows that the proposed method outperforms existing methods on all three datasets across both metrics.

This table compares the number of learnable parameters for the proposed model and baseline models across three different datasets: MNIST-derived datasets, Brain MRI dataset, and 3D objects rendered datasets. It highlights the relative efficiency of the proposed model in terms of the number of parameters used compared to alternative approaches.

This table compares the number of learnable parameters across different models and datasets. It shows that the proposed model (‘Ours’) has a significantly smaller number of parameters than most other models, particularly on the 3D rendered datasets, while still achieving comparable or better performance. This suggests that the model’s efficiency is not solely dependent on the complexity or size of the model architecture.

Full paper#