↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing prototype-based image classification models often struggle with handling geometric variations and providing clear explanations. They primarily use Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) which limits their ability to handle irregular shapes effectively. Furthermore, the existing models often lack semantic coherence in their prototypes, making it difficult to understand their reasoning process. These limitations hinder the adoption of prototype-based models in critical applications where human interpretability is crucial.

ProtoViT, presented in this paper, tackles these issues by integrating Vision Transformers (ViTs) into prototype-based models. The use of ViTs allows for better handling of irregular geometries and generating more coherent prototype representations. The model also incorporates an adaptive mechanism to dynamically adjust the number of prototypical parts, ensuring clear visual explanations. Through comprehensive experiments and analysis, ProtoViT demonstrates superior performance to existing prototype-based models, while maintaining inherent interpretability. The model’s innovative architecture and improved performance pave the way for future advancements in explainable AI for image classification.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between the need for accurate image classification and the demand for model interpretability, especially in high-stakes applications. ProtoViT offers a novel approach that improves accuracy while providing clear, faithful explanations, advancing the field of explainable AI. Its use of Vision Transformers and adaptive prototypes opens new avenues for research in various domains.

Visual Insights#

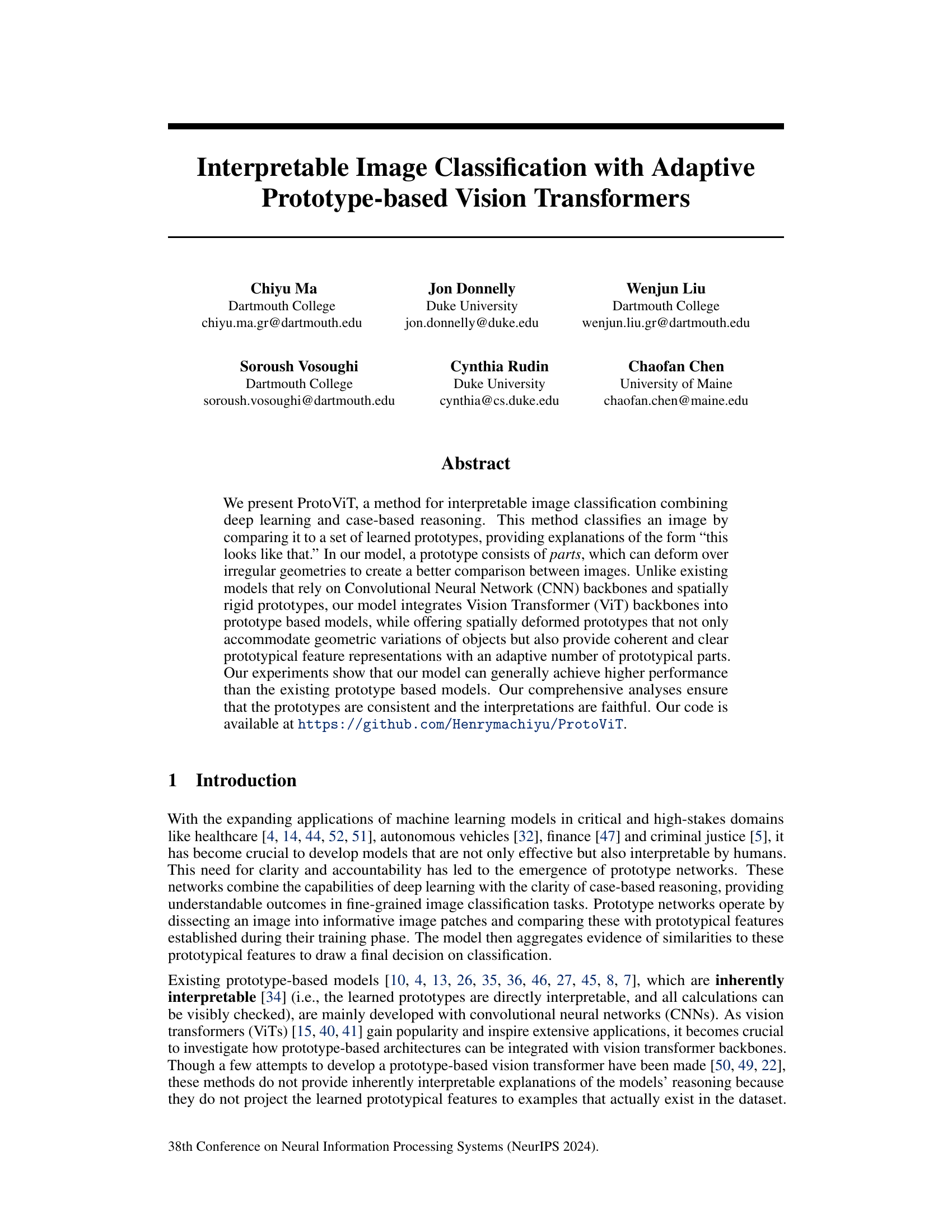

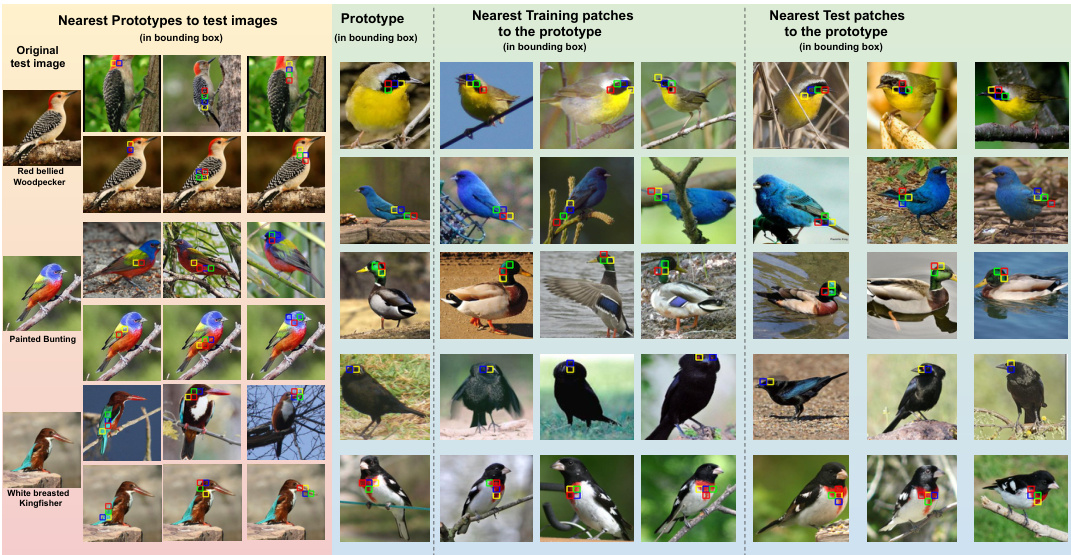

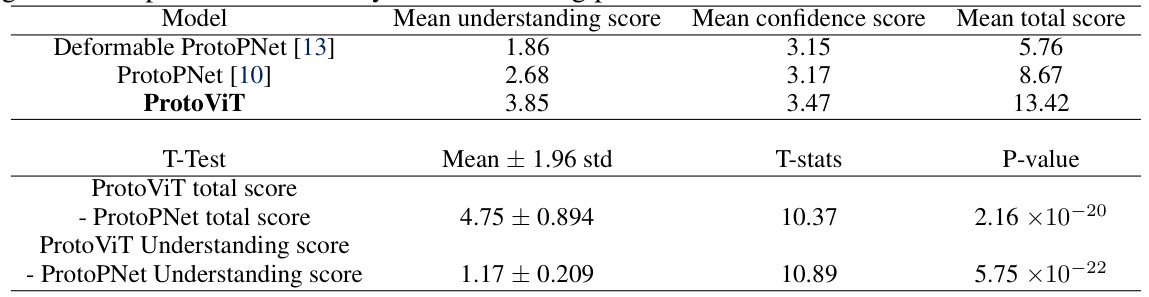

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models: ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT. Each model attempts to classify a test image of a male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. The figure showcases the prototypes used by each model to arrive at its classification. ProtoPNet uses rigid rectangular prototypes, leading to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformable prototypes, but these lack semantic coherence and the explanations are still unclear. ProtoViT, the authors’ proposed method, employs deformable prototypes that adapt to shape and maintain semantic coherence, resulting in clear and faithful interpretations. The bounding boxes highlight the prototypes used in the classification process for each method.

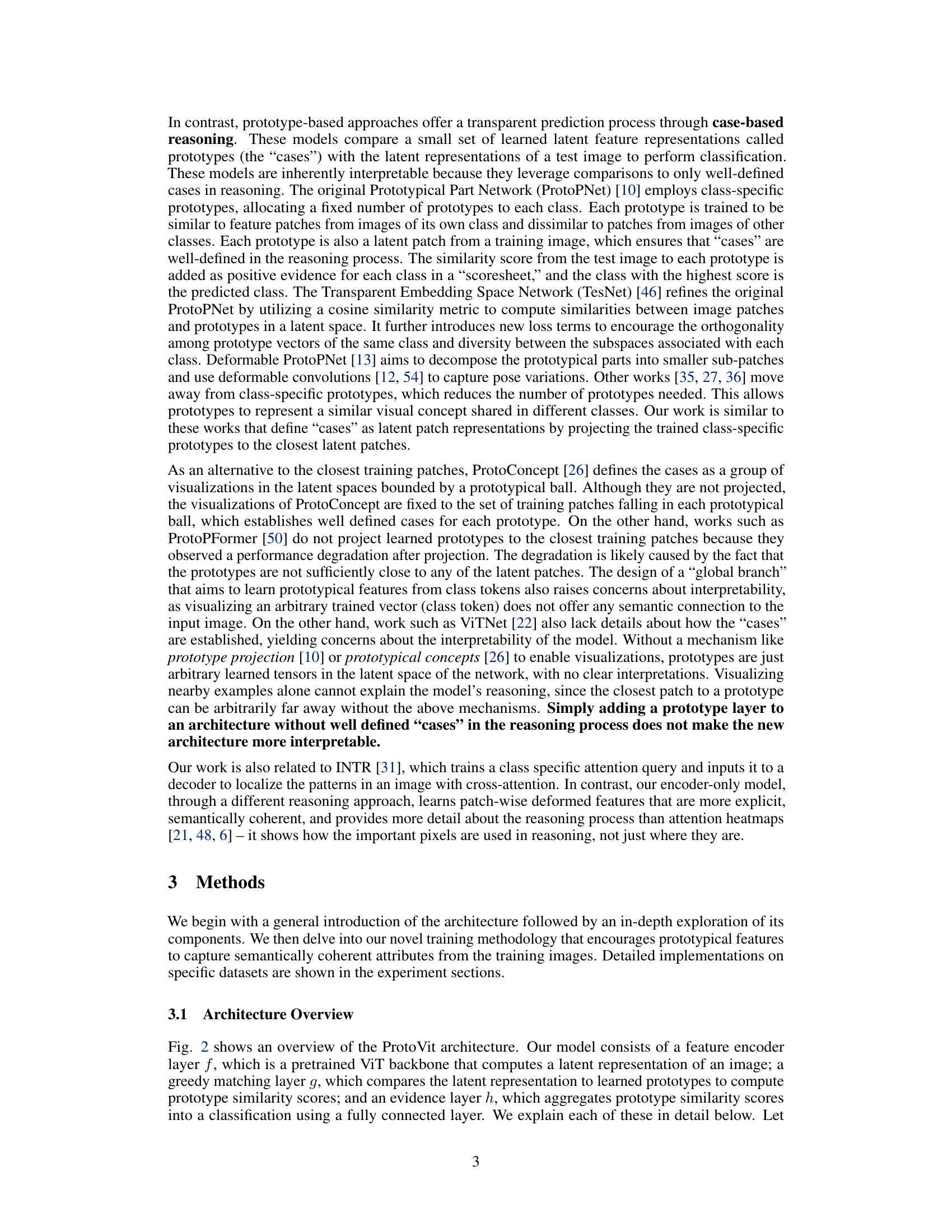

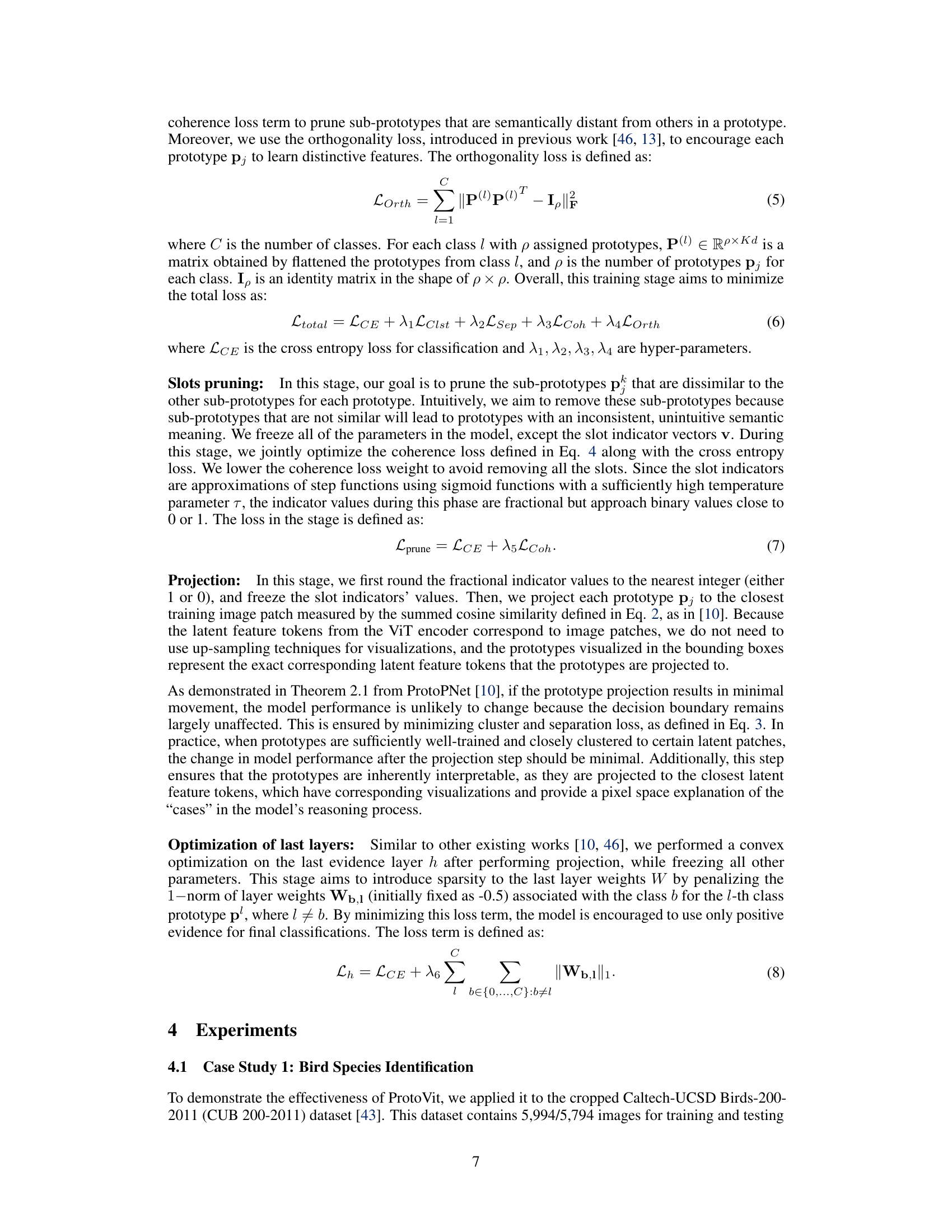

This table compares ProtoViT with three other existing interpretable image classification models: ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoPformer. The comparison is made across five key features: whether the model supports Vision Transformer (ViT) backbones, whether it uses deformable prototypes, whether the resulting prototypes are semantically coherent, whether the prototypes have adaptive sizes, and finally whether the model is inherently interpretable. ProtoViT is shown to be superior in most of the features, improving upon limitations seen in previous work.

In-depth insights#

ProtoViT Overview#

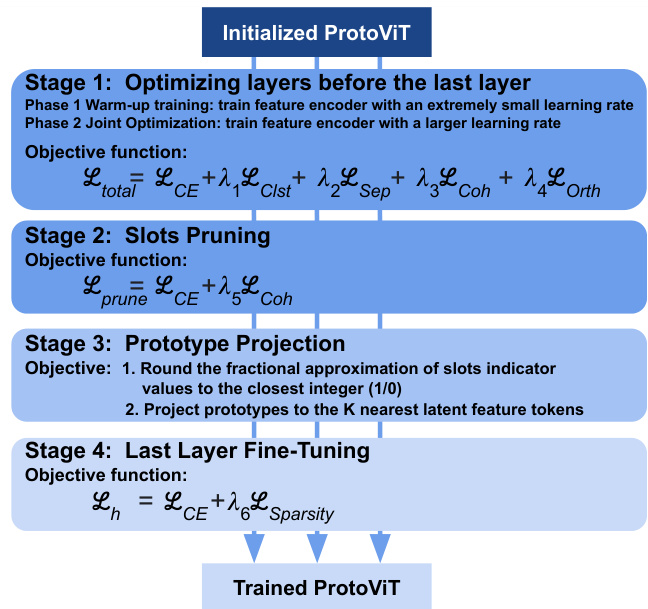

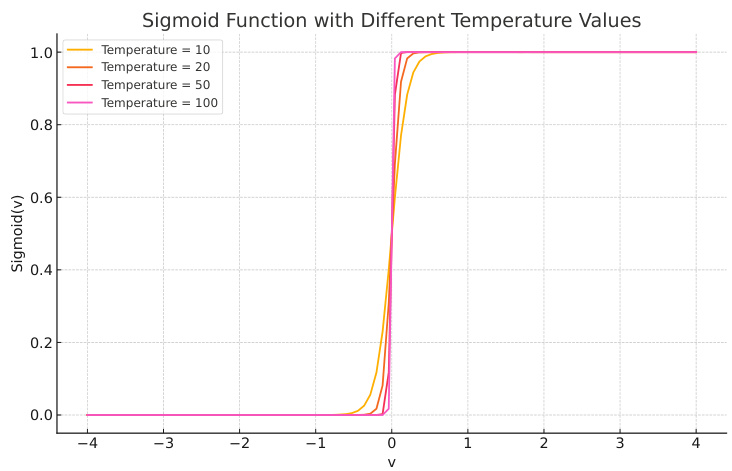

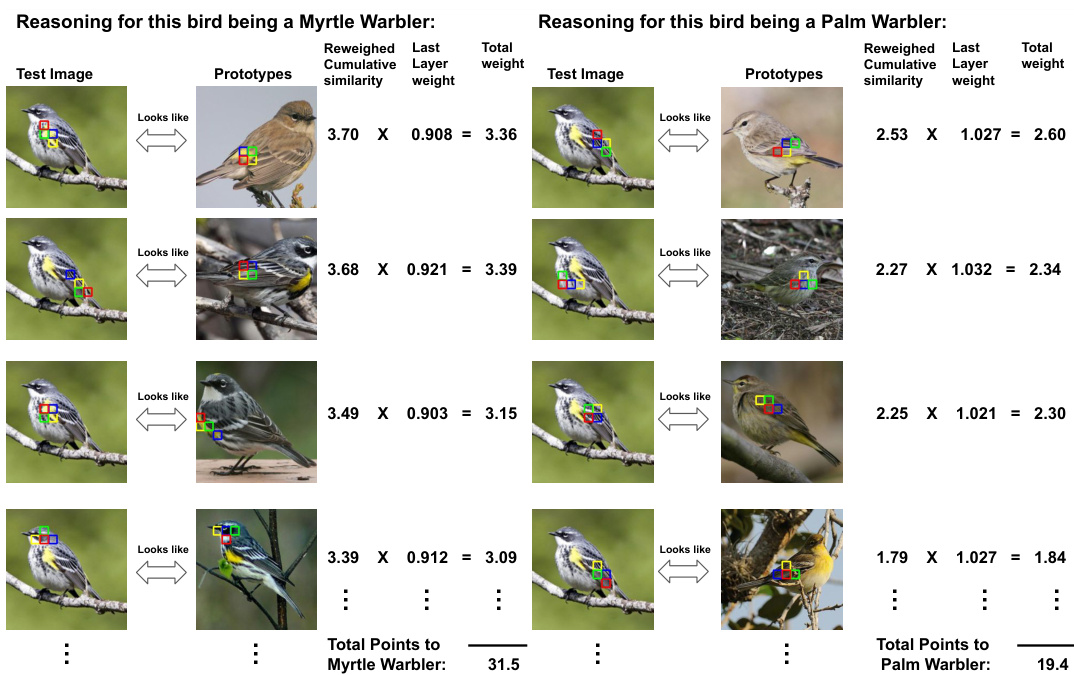

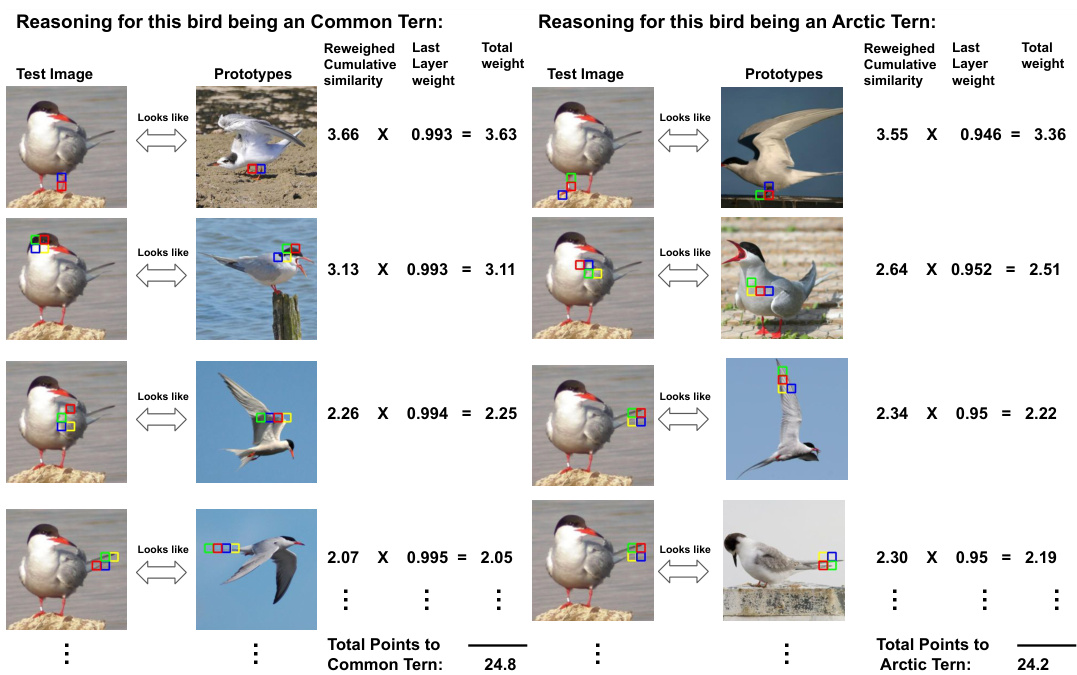

ProtoViT, a novel architecture designed for interpretable image classification, integrates Vision Transformers (ViTs) with adaptive prototype-based reasoning. Unlike CNN-based approaches, ProtoViT uses ViTs to encode image patches into latent feature tokens, enabling a more flexible and adaptable prototype representation. The model learns prototypes consisting of deformable sub-prototypes that adjust to geometric variations in the input images, creating more coherent and clear prototypical feature representations. A greedy matching algorithm ensures that the comparison between input image patches and sub-prototypes is both efficient and geometrically coherent, avoiding the ambiguities found in existing methods. The adaptive slots mechanism further enhances the interpretability and efficiency by allowing the model to dynamically adjust the number of sub-prototypes per prototype. The entire process results in interpretable image classifications with explanations in the form of ’this looks like that,’ offering a transparent and faithful interpretation of the model’s decision-making process.

Adaptive Prototypes#

The concept of “Adaptive Prototypes” in the context of a vision transformer for image classification is a significant advancement. It directly addresses the limitations of traditional prototype-based models, which often rely on fixed, spatially rigid representations. Adaptive prototypes dynamically adjust their shape and size to better match the geometric variations within the input images. This flexibility allows for more accurate comparisons and more robust feature extraction, leading to improved classification accuracy and interpretability. The adaptability is crucial because it enables the model to learn coherent and clear prototypical feature representations even with irregular or deformed objects. Unlike previous methods that might have multiple features bundled within a single bounding box, adaptive prototypes dissect the feature space more effectively. The dynamic nature of the prototypes is likely achieved through a sophisticated mechanism such as deformable attention or a learned deformation field, allowing the model to learn highly context-specific features while ensuring that the final interpretation remains faithful to the underlying data. This approach greatly enhances the interpretability of the model by providing clear and concise explanations of its reasoning process.

ViT Integration#

Integrating Vision Transformers (ViTs) into prototype-based image classification models presents a unique opportunity to leverage the strengths of both architectures. ViTs excel at capturing global contextual information, a critical aspect often overlooked by Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) commonly used in prototype methods. This integration allows for more robust feature representation and potentially improves classification accuracy. However, the inherent spatial insensitivity of standard ViTs requires careful consideration. The paper successfully addresses this by using a novel architecture with adaptive prototypes that deform to accommodate geometric variations within objects. This allows for more effective comparison between images and prototypes and ensures that resulting explanations remain clear and faithful to the model’s reasoning process. A key challenge overcome was aligning the inherently discrete output tokens of ViTs with the continuous latent space typically used in prototype deformation. The paper’s approach adeptly addresses this challenge, enhancing the interpretability of the resulting system. While previous ViT-based prototype methods lacked rigorous analysis to validate the inherent interpretability of their learned features, this research incorporates comprehensive analyses to confirm the fidelity and coherence of the generated prototypes and explanations. This comprehensive analysis is a significant contribution, proving the trustworthiness of the method.

Interpretability Focus#

The research paper’s “Interpretability Focus” likely centers on explainable AI (XAI), aiming to make the model’s decision-making process transparent and understandable. This is achieved by using prototype-based methods, where the model’s classifications are explained by comparing the input image to a set of learned prototypes. The model’s design is particularly noteworthy as it integrates vision transformers (ViTs) with the prototype approach, offering improved accuracy compared to prototype models that use CNNs. The focus isn’t merely on providing explanations, but also on their faithfulness and coherence. Faithfulness means the explanations accurately reflect the model’s internal reasoning, while coherence ensures the prototypes are semantically consistent and clearly represent distinct visual concepts. The paper likely presents thorough analyses demonstrating these qualities, potentially through visualizations and metrics that assess the alignment between the explanation and the actual decision-making process. Ultimately, the “Interpretability Focus” highlights the development and evaluation of an XAI model that balances high accuracy with meaningful and trustworthy explanations.

Future Extensions#

Future extensions of prototype-based vision transformers (ProtoViT) could explore several promising directions. Improving the efficiency of the greedy matching algorithm is crucial, possibly through approximate nearest neighbor search techniques or more sophisticated attention mechanisms. Incorporating richer contextual information beyond simple image patches, such as object relationships or scene context, could enhance both accuracy and interpretability. Expanding to more complex tasks beyond image classification, such as object detection, segmentation, or video understanding, would demonstrate the model’s versatility. Investigating different deformable prototype designs, potentially inspired by more advanced attention models or generative models, may lead to more robust and expressive representations. Finally, exploring the integration of ProtoViT with large language models (LLMs) could enable richer textual explanations and open up exciting possibilities for multimodal reasoning and understanding.

More visual insights#

More on figures

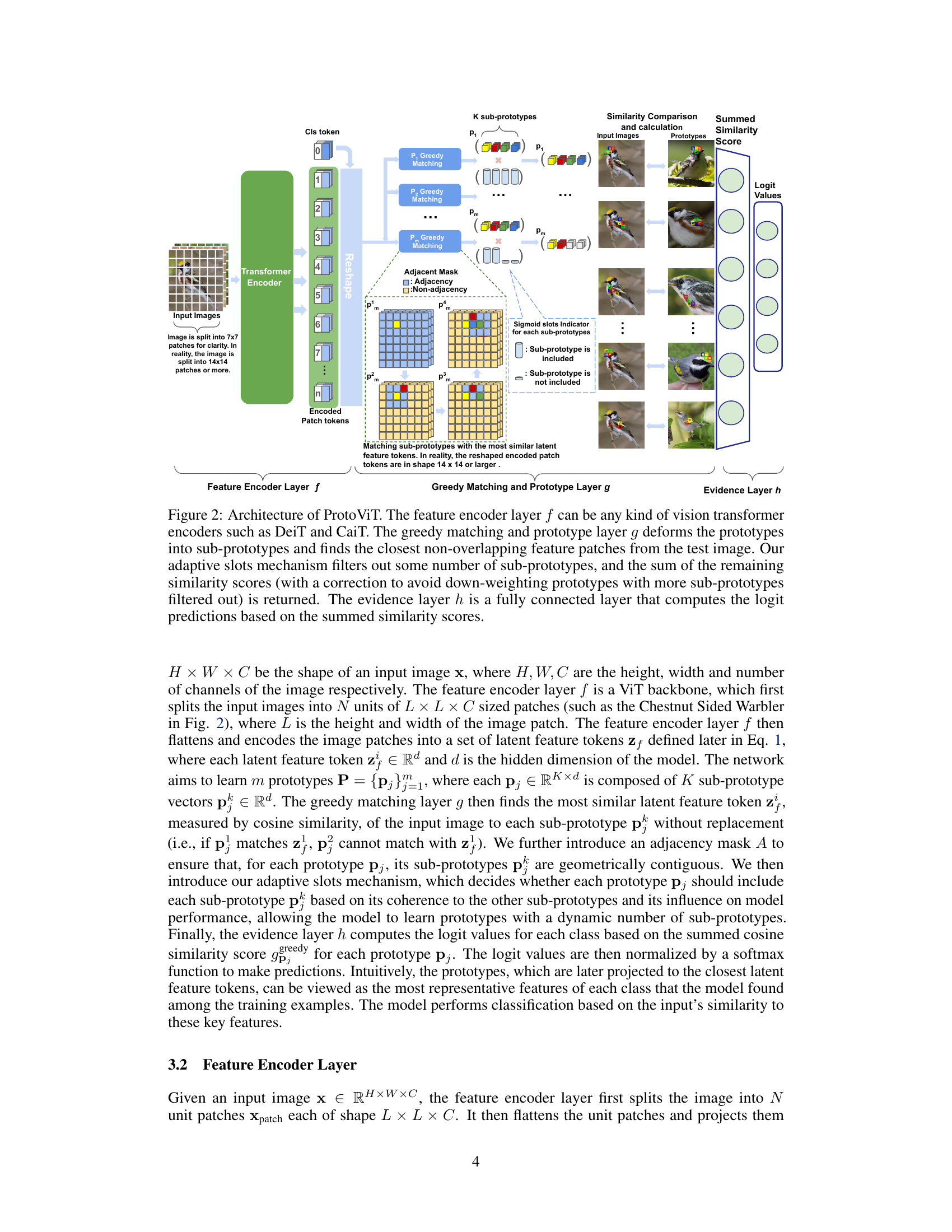

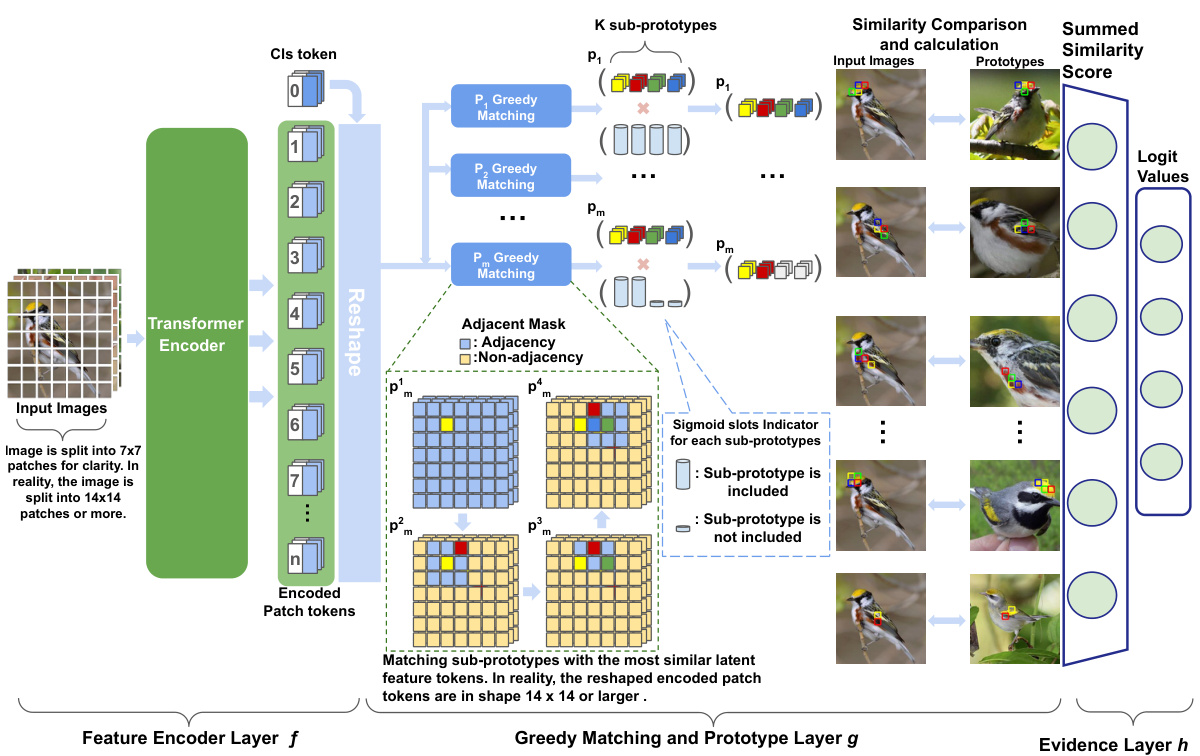

This figure illustrates the architecture of ProtoViT, a novel prototype-based vision transformer. It consists of three main layers: a feature encoder (f), which uses a vision transformer (like DeiT or CaiT) to extract features from input images; a greedy matching and prototype layer (g), which deforms prototypes into smaller sub-prototypes, matches them with the most similar image patches, and incorporates an adaptive slots mechanism to select relevant sub-prototypes; and an evidence layer (h), which combines similarity scores to produce final classification logits. The figure highlights the adaptive nature of the prototype selection and the use of adjacency masks to ensure spatial coherence.

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes that lead to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes, but these lack semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) uses deformed prototypes that adapt to the shape of the object and offer greater semantic coherence, providing clearer and more accurate explanations.

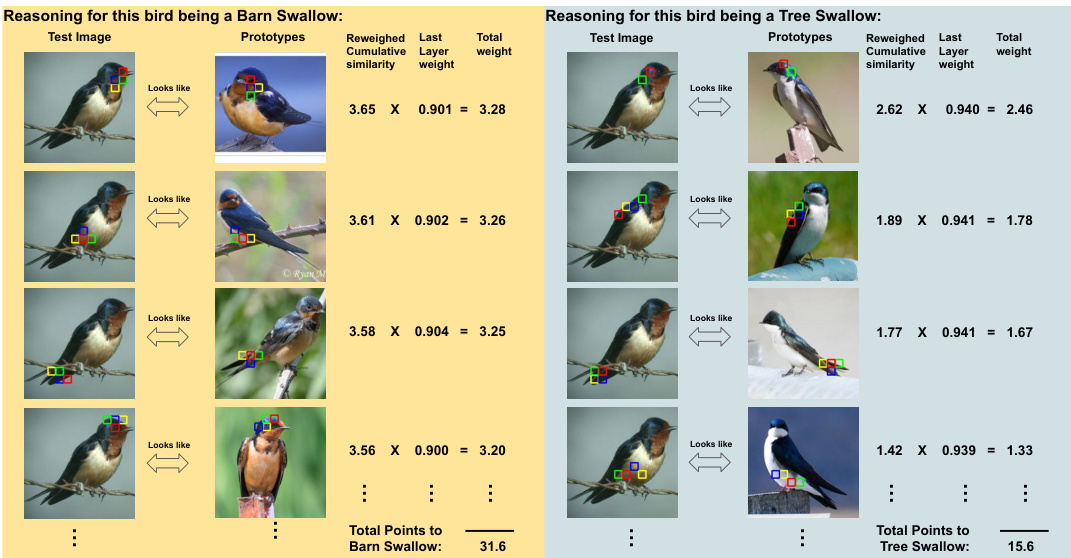

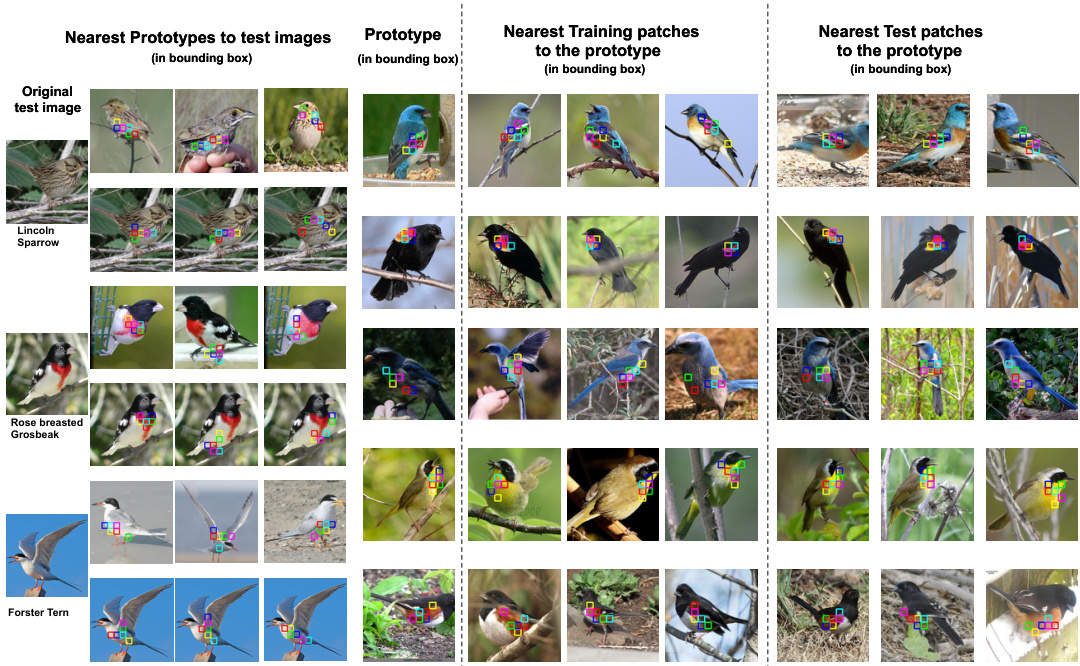

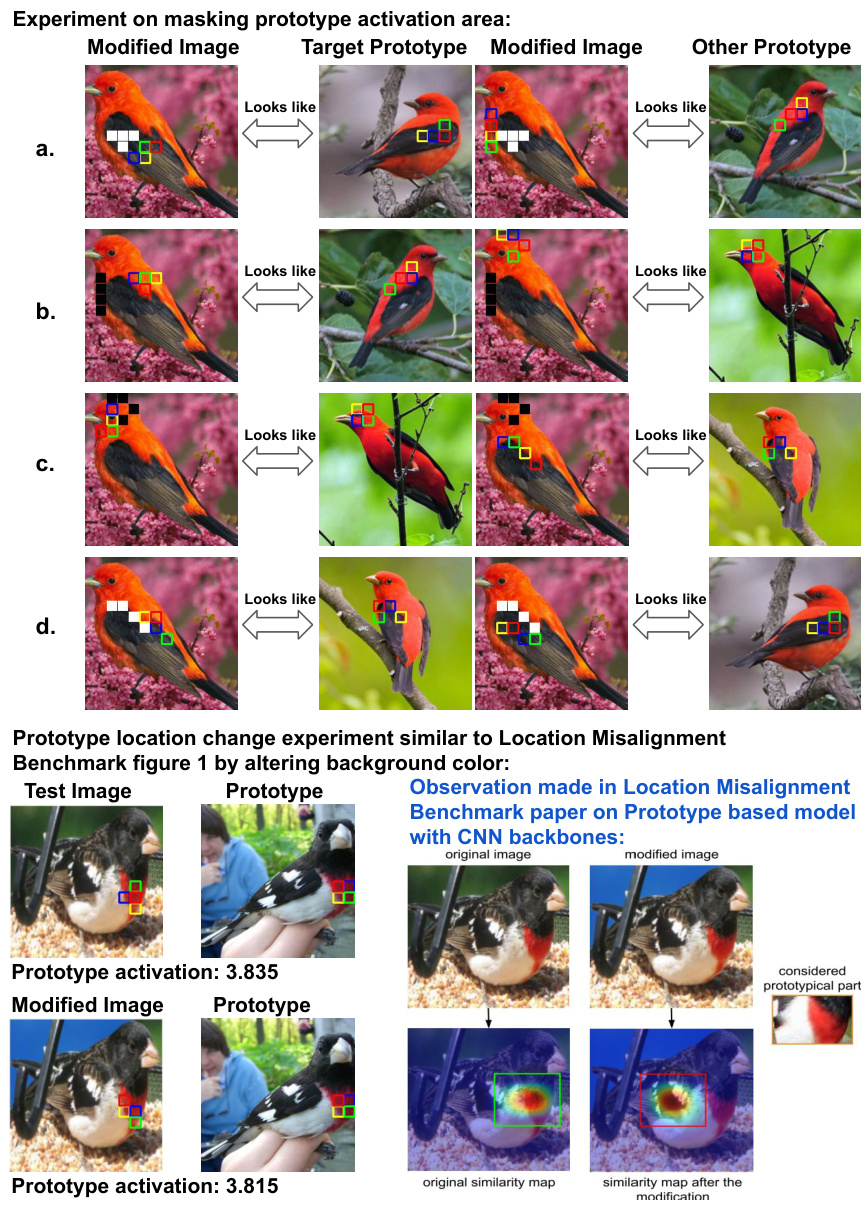

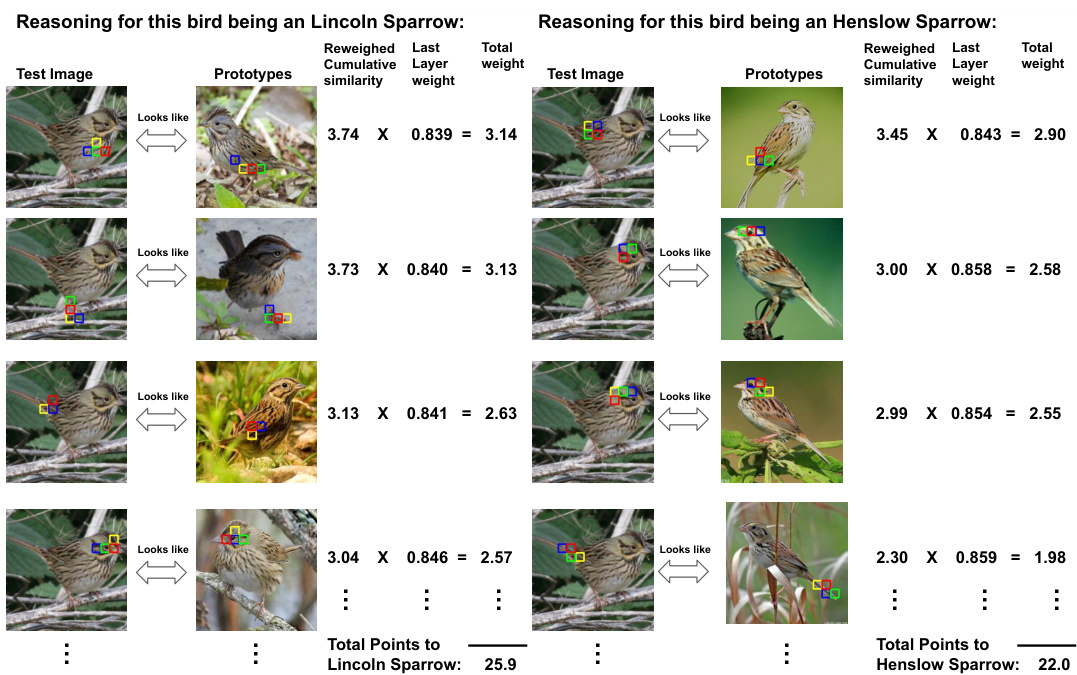

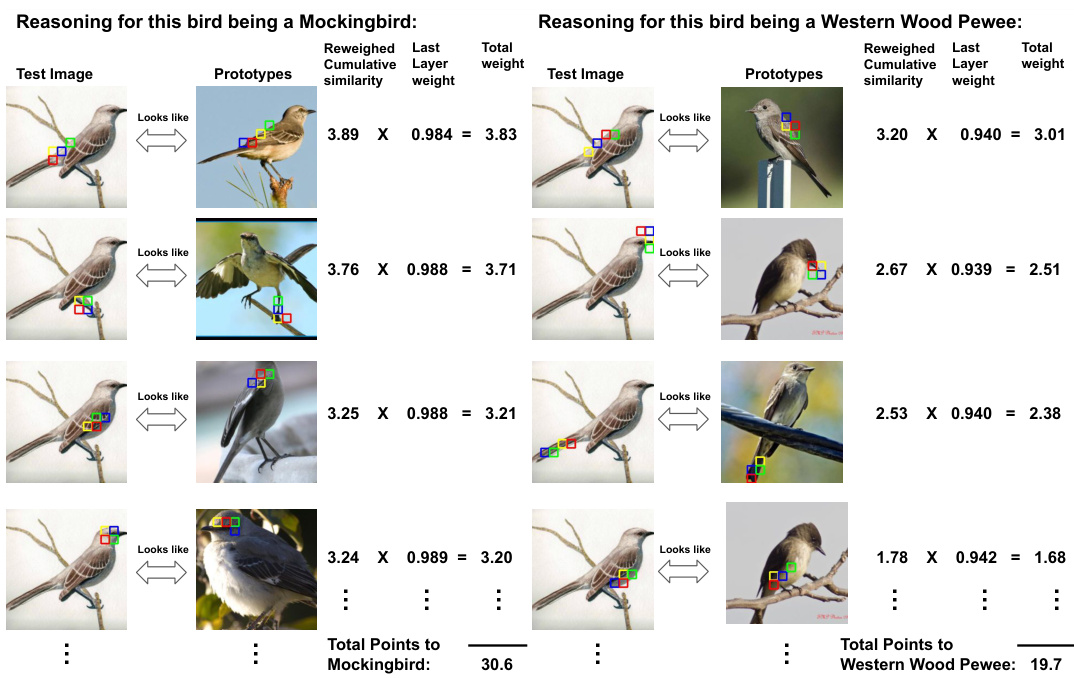

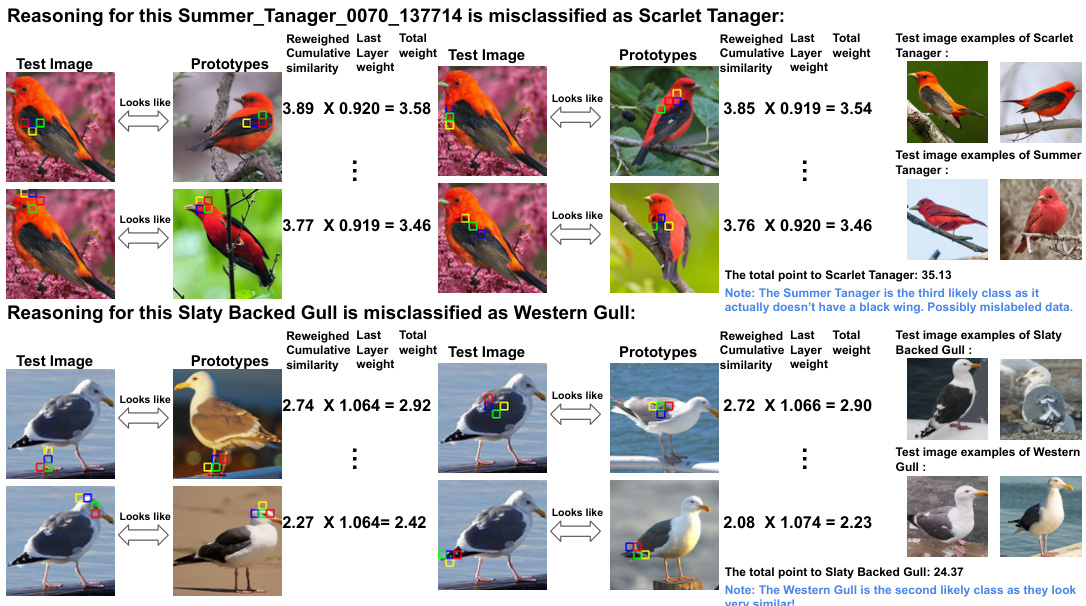

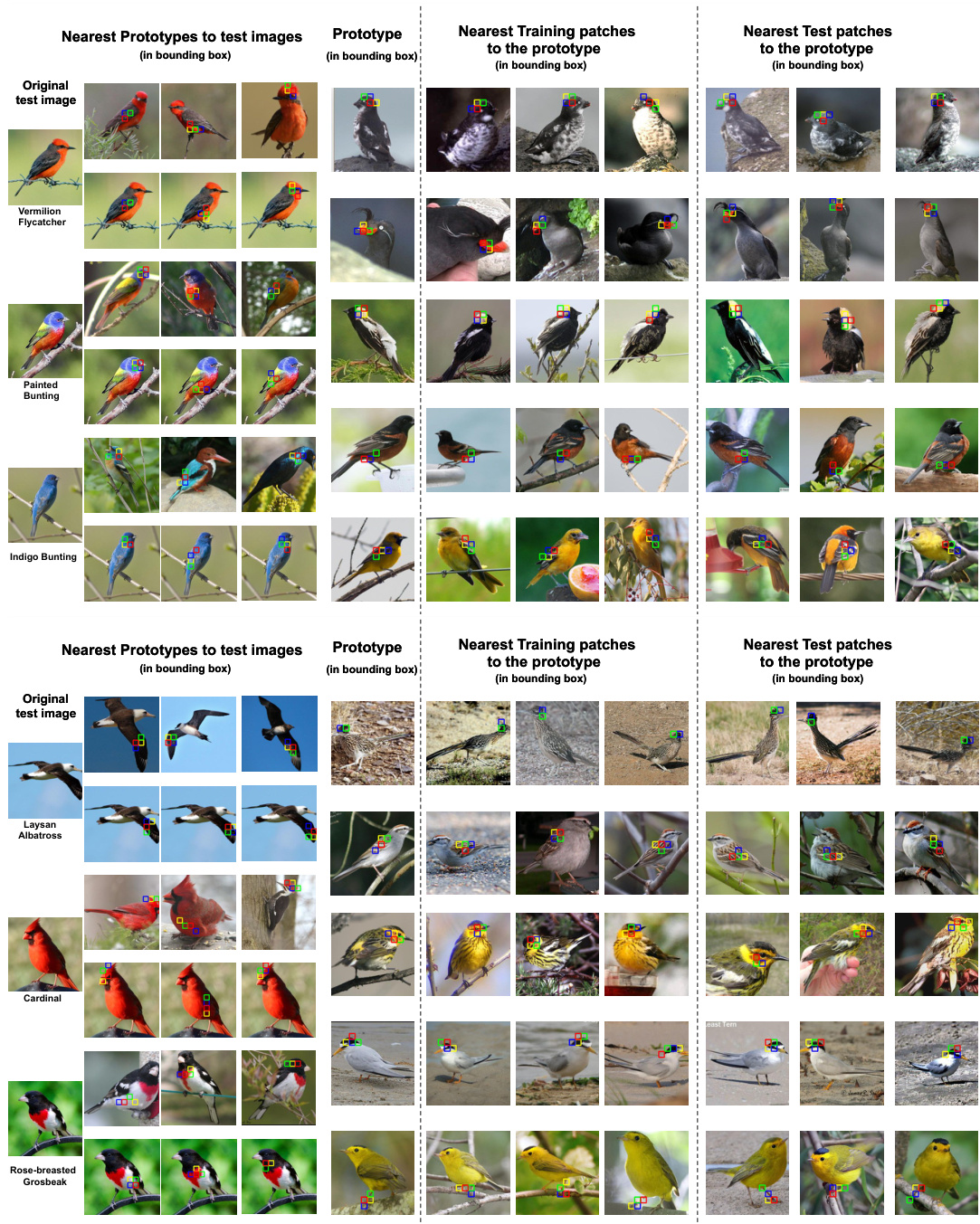

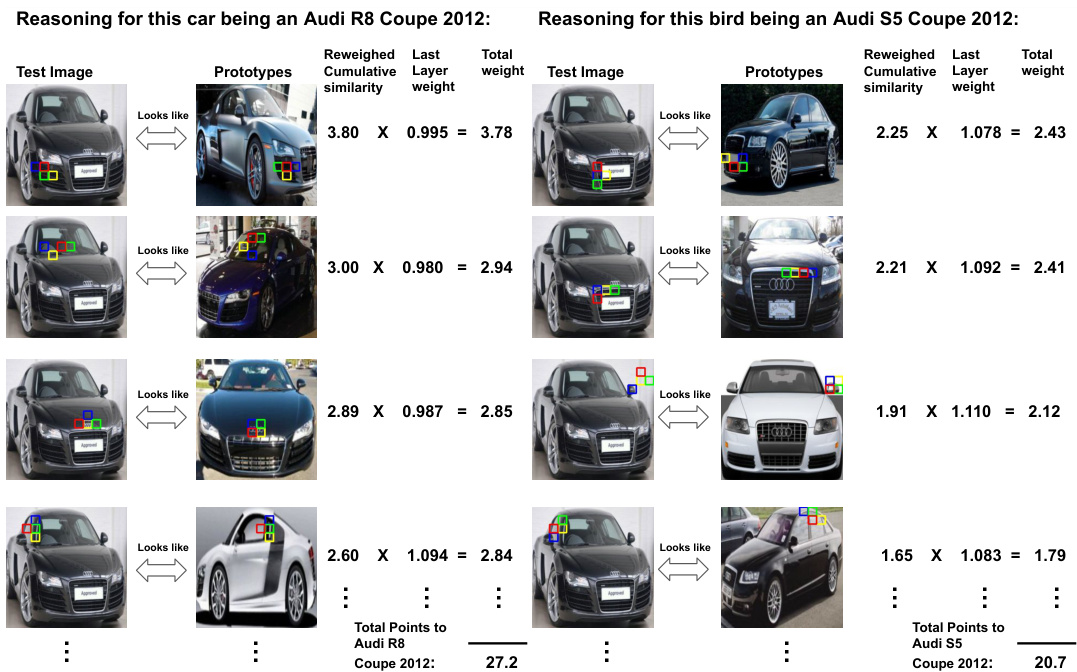

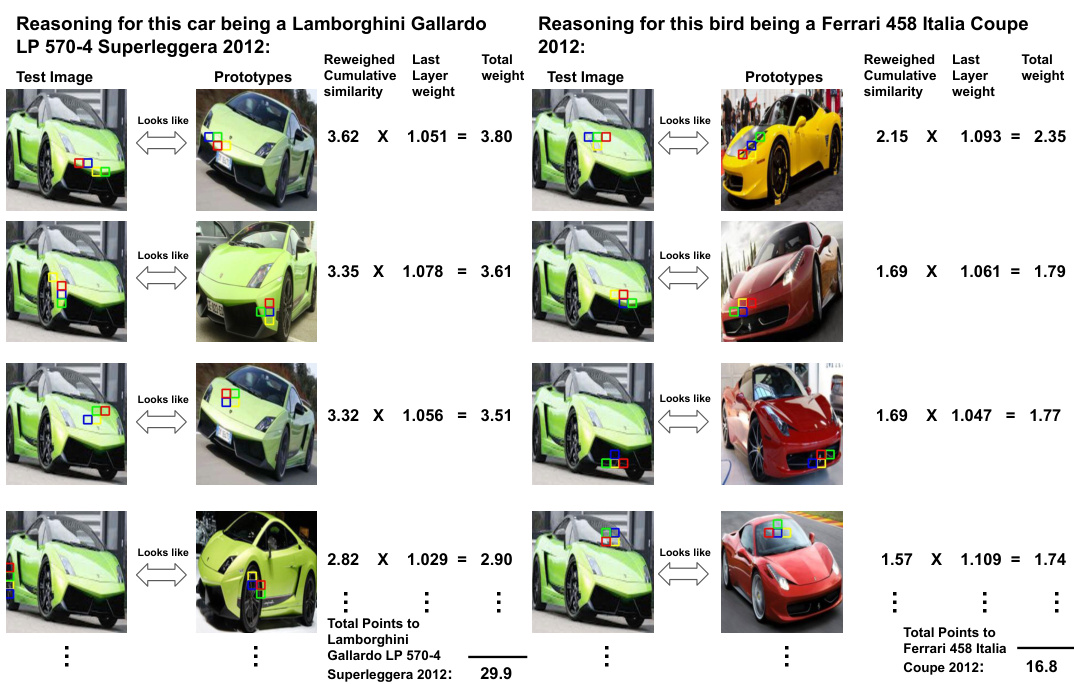

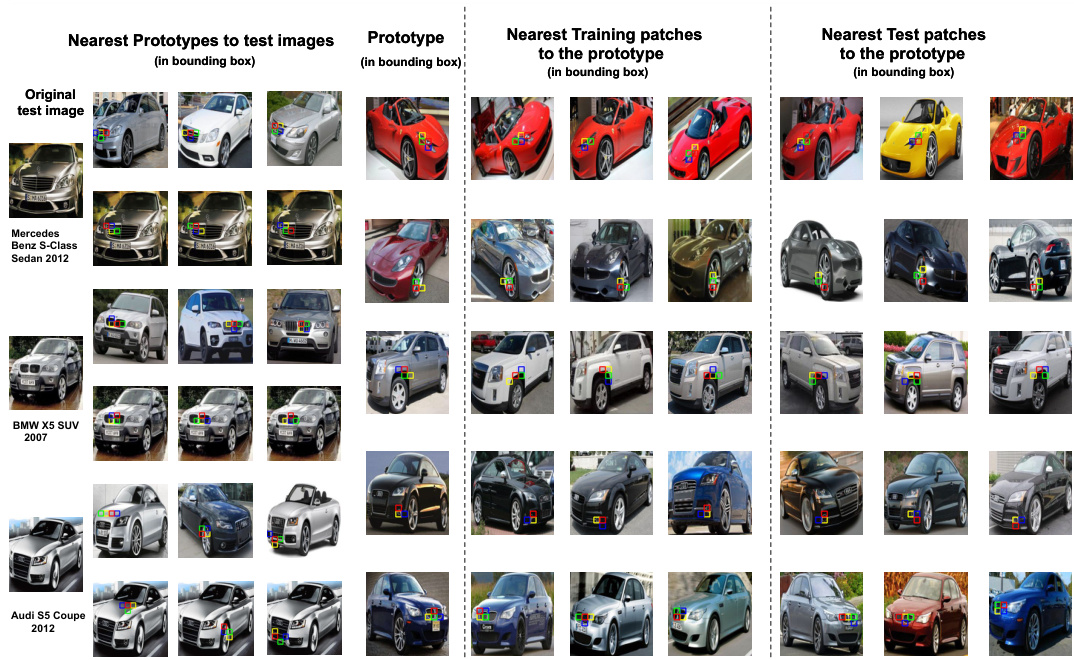

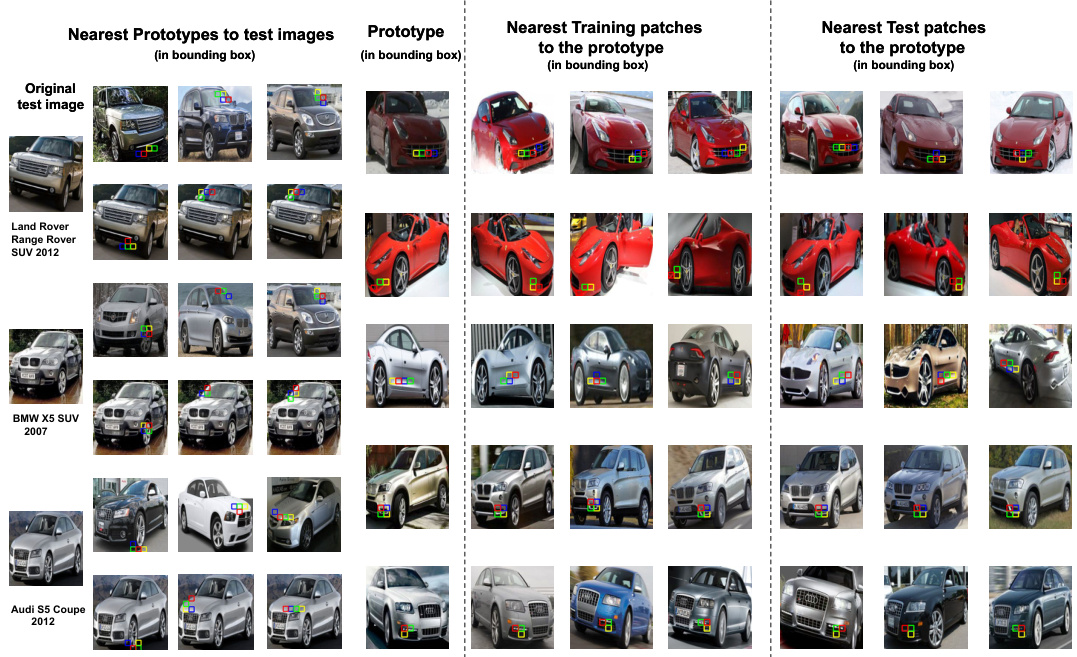

This figure shows a comparison of nearest prototypes to test images and nearest training/test patches to the prototypes. The left side shows the prototypes identified by ProtoViT for several test images, highlighting the key features used for classification. The right side demonstrates how the model finds similar image patches in the training and test datasets, that correspond to the identified prototypes. This visualization helps to understand the model’s reasoning process by illustrating the semantic similarity between prototypes and actual images.

This figure illustrates the architecture of ProtoViT, a novel prototype-based vision transformer for interpretable image classification. It shows three main layers: a feature encoder (f), a greedy matching and prototype layer (g), and an evidence layer (h). The feature encoder processes the input image using a Vision Transformer backbone. The greedy matching layer compares the encoded image features to learned prototypes, allowing for geometrically adaptive comparisons. The adaptive slots mechanism efficiently selects the most relevant sub-prototypes for the classification. Finally, the evidence layer aggregates the similarity scores from the matching process to produce the final classification logits.

This figure illustrates the architecture of ProtoViT, a novel prototype-based vision transformer. It comprises three main layers: a feature encoder (f), a greedy matching and prototype layer (g), and an evidence layer (h). The feature encoder processes the input image using a Vision Transformer (ViT) backbone. The greedy matching layer compares the encoded image patches to learned prototypes, identifying the closest matches while handling geometric variations and dynamically selecting relevant prototype parts using an adaptive slots mechanism. Finally, the evidence layer aggregates the similarity scores to generate the final classification.

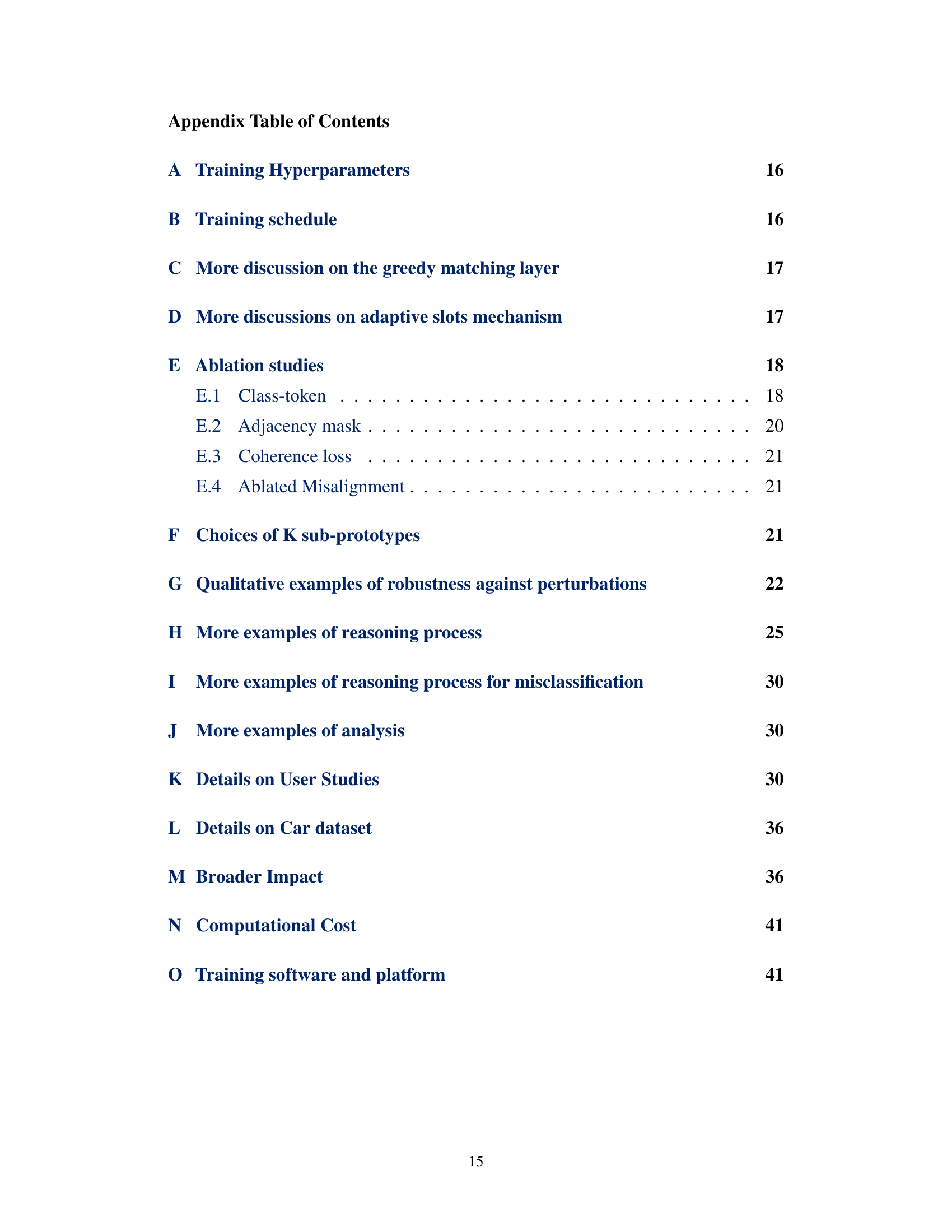

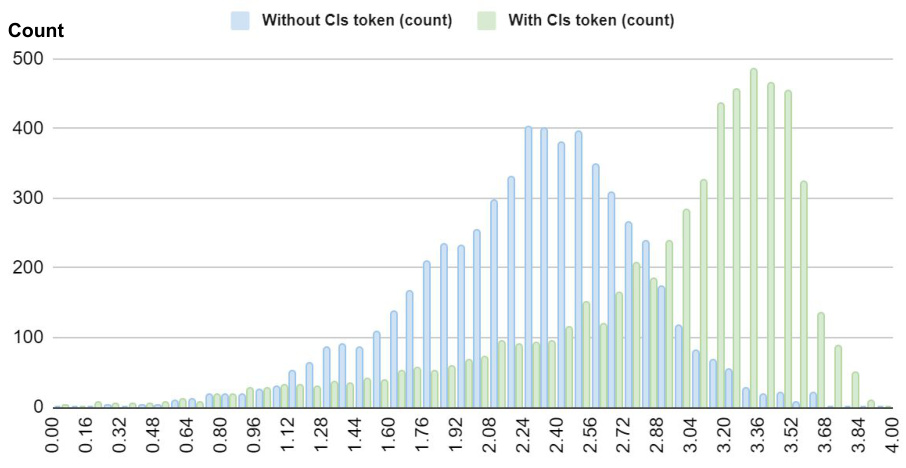

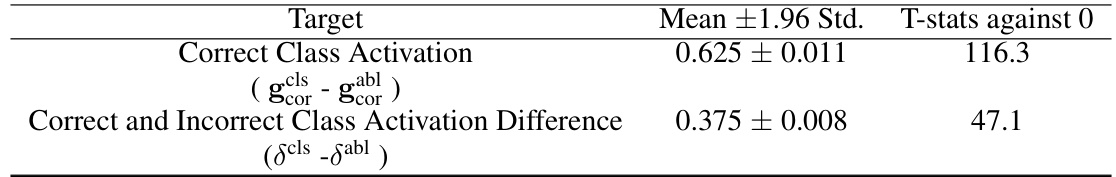

The figure shows three histograms visualizing the distribution of mean correct class activation, the largest mean incorrect class activation, and the difference between the two for ProtoViT models trained with and without the class token. The class token version shows a greater separation between correct and incorrect class activations.

This figure presents a histogram analysis comparing the mean activation of ProtoViT models with and without class tokens. Three histograms are shown: one showing the mean correct class activation, one showing the largest mean incorrect class activation, and one showing the difference between the mean correct class activation and the largest mean incorrect class activation. Each histogram is displayed for both the model with and without the class token, allowing for a comparison of the impact of including the class token on the model’s activation patterns.

This figure presents a histogram analysis comparing the mean activation of ProtoViT models with and without a class token. Three histograms are shown, visualizing: the mean correct class activation, the largest mean incorrect class activation, and the difference between the mean correct and incorrect class activations. The distributions for models with and without the class token are compared within each histogram, to demonstrate the impact of the class token on the model’s ability to distinguish between correct and incorrect classifications.

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models: ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT. Each model attempts to classify a test image of a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. The figure highlights how the different approaches handle the comparison between the test image and learned prototypes. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes which lead to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformable prototypes but lacks semantic coherence. ProtoViT, in contrast, utilizes deformed prototypes that adapt to the shape of the object and maintain semantic coherence, resulting in more clear and faithful interpretations.

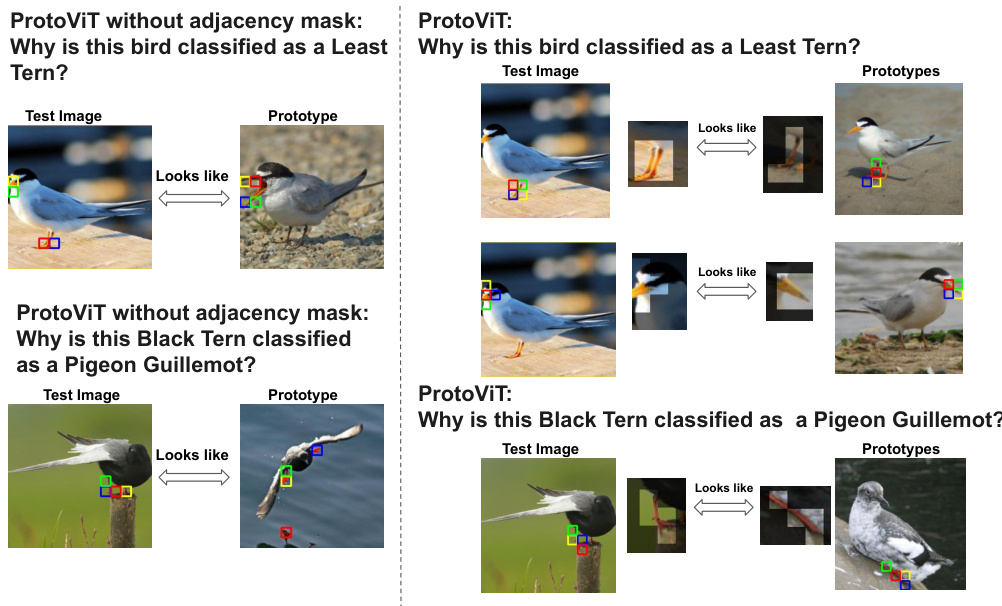

This figure compares the reasoning process of ProtoViT with and without the adjacency mask. The left column shows the results of ProtoViT without the adjacency mask, while the right column shows the results of ProtoViT with the adjacency mask. The figure uses two examples to illustrate how the adjacency mask improves the coherence and accuracy of the model’s predictions. In the first example, both models correctly classify a Least Tern image. In the second example, ProtoViT without the adjacency mask misclassifies a Black Tern image as a Pigeon Guillemot, while ProtoViT with the adjacency mask correctly classifies the Black Tern. This highlights how the adjacency mask helps to prevent the model from making incoherent and inaccurate predictions by ensuring that the sub-prototypes within each prototype are geometrically contiguous.

This figure demonstrates how three different prototype-based models classify a test image. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes, leading to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes, but the parts lack semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) uses deformed prototypes with better shape adaptation and semantic coherence, resulting in clearer and more accurate interpretations.

This figure demonstrates how three different prototype-based models classify a test image of a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. It highlights the differences in how each model identifies and uses prototypes to reach a classification decision. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes leading to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes, but the features lack semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) uses deformed prototypes with clear and coherent semantics, illustrating its superiority in providing interpretable explanations.

This figure shows a comparison between the nearest prototypes to test images and the nearest training/test image patches to the learned prototypes. The left side displays prototypes projected onto their closest test image patches. The right side shows the training and test patches that are most similar to each learned prototype. The visualization demonstrates the model’s ability to identify semantically coherent and geometrically consistent features from images during training and testing.

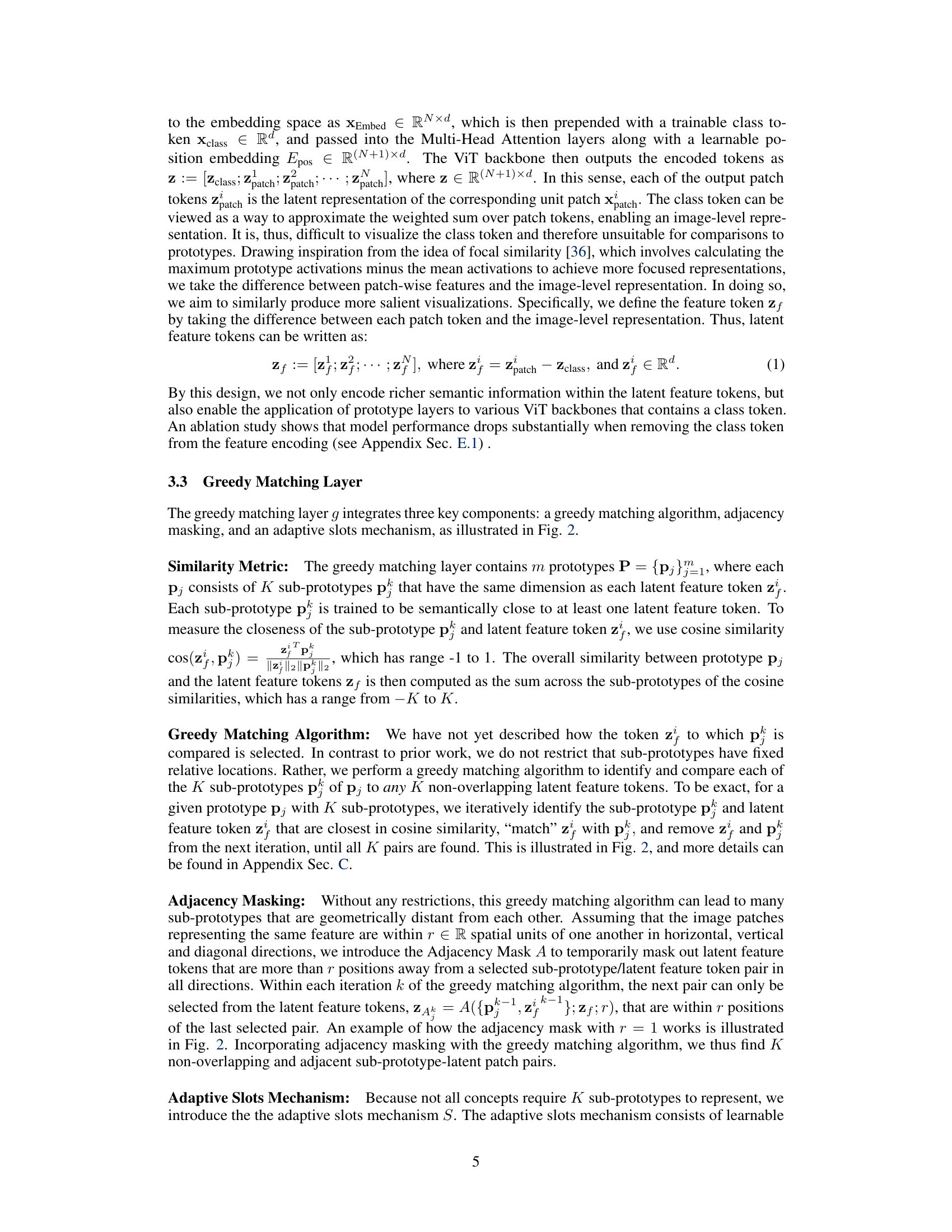

This figure shows two types of analysis to demonstrate the semantic consistency of the prototypes generated by ProtoViT. The left side displays local analysis, showing the most semantically similar prototypes to each test image. The right side shows global analysis, presenting the top three nearest training and testing images to the prototypes (excluding the training image itself that was used to create the prototype). The purpose is to show that the learned prototypes consistently represent a single, meaningful concept and the model comparisons are reasonable.

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models in identifying a test image of a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes leading to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes, but lacks semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) offers deformed prototypes that adapt to the shape and maintain semantic coherence. The bounding boxes highlight the prototypes in each model’s reasoning process.

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based models for image classification: ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT. Each model’s inference process is illustrated, showing how it compares the test image with its learned prototypes to arrive at a classification decision. The key takeaway is how ProtoViT utilizes deformed prototypes that adapt to the shape of the target image, leading to more precise and interpretable explanations than the other models which employ rectangular or ambiguously deformed prototypes.

This figure compares three different prototype-based models’ reasoning process for classifying a test image of a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. It illustrates how the models use learned prototypes (visual representations of features) to match against an input image. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes, which can be too broad and lead to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet improves upon this by using deformable prototypes, which adjust to the image’s shape, but still lacks semantic coherence in their representations. ProtoViT, the proposed model, uses deformable prototypes that both adapt to the image’s shape and provide clear, coherent prototypical feature representations, resulting in more accurate and interpretable classifications. The bounding boxes visually highlight the prototypes and their correspondence to parts of the input image.

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes that lead to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes but lacks semantic coherence, making the explanations unclear. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) uses deformed prototypes that adapt well to the image shape and provide coherent, clear explanations of the classification.

The figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes, resulting in ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes, but lacks semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) uses deformed prototypes that adapt to shape and maintain semantic coherence, providing clearer and more accurate explanations.

This figure compares three different prototype-based models on a single example image: ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT. The goal is to illustrate how each method identifies the image’s class (Male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird) by comparing image patches to its learned prototypes. It highlights the differences in how the models use prototypes, particularly regarding their shape and resulting explanations. ProtoPNet uses rigid rectangular prototypes leading to vague explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet improves by allowing deformed prototypes, but the resulting explanations still lack semantic coherence. ProtoViT, the proposed model, uses deformed prototypes with improved semantic coherence resulting in clearer explanations.

This figure compares how three different prototype-based models classify a test image. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes that lead to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes that lack semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the proposed model) uses deformed prototypes that are both adaptive and semantically coherent, offering more accurate and clear explanations.

This figure demonstrates the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models. It showcases how each model identifies the class of a test image (a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird) by comparing it to learned prototypes. The figure highlights the differences in how the models represent and utilize their prototypes. ProtoPNet uses broad rectangular prototypes, leading to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformable prototypes which are better but still lack semantic coherence, meaning the parts of the prototypes do not clearly correspond to meaningful features of the hummingbird. ProtoViT (the authors’ proposed model) utilizes deformed prototypes that adapt to the shape of the hummingbird and possess semantic coherence, providing clearer and more interpretable explanations.

This figure compares three different prototype-based models’ reasoning processes when classifying a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird image. The top row shows the results of ProtoPNet, demonstrating ambiguous explanations due to rectangular prototypes. The middle row illustrates Deformable ProtoPNet, where deformed prototypes adapt to the shape but lack semantic coherence. Finally, the bottom row showcases ProtoViT (the proposed model), exhibiting both shape adaptation and improved semantic coherence in its explanations through deformed prototypes.

The figure compares how three different prototype-based models (ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT) classify a test image of a male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. It highlights the differences in how the models use prototypes to reach a classification decision. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes that are too broad and result in ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes that adapt to the shape of the bird but lack semantic coherence, making it unclear what aspects of the bird each prototype captures. ProtoViT, in contrast, uses deformed prototypes that adapt to shape and exhibit semantic coherence, leading to clearer and more accurate explanations. The bounding boxes visually represent the prototypes in each model and how they match with regions of the test image.

This figure compares three different prototype-based models’ reasoning processes for classifying a male Ruby-throated Hummingbird image. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes leading to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes but lacks semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) uses deformed prototypes with improved semantic coherence, better adapting to the image’s shape and providing clearer explanations.

This figure demonstrates the local and global analysis conducted to evaluate the semantic consistency and coherence of ProtoViT’s prototypes. The left side displays local analysis, showing the most semantically similar prototypes to each test image. The right side shows global analysis, showcasing the top three nearest training and testing images to each prototype. This helps validate that the model’s learned prototypes are faithful and consistent across various instances of the same visual concept.

This figure shows the results of the local and global analysis for ProtoViT. The left side shows the nearest prototypes to the test images, while the right side displays the nearest training and testing image patches to the prototypes. By comparing these images, the authors illustrate the model’s ability to learn prototypes that consistently activate on the same, meaningful concept across different images. The exclusion of the nearest training patch serves to highlight the model’s ability to generalize beyond simply memorizing the training data.

This figure visualizes the nearest prototypes to test images and the nearest image patches to prototypes. The left side shows the nearest prototypes to test images, while the right side shows the nearest training patches to prototypes. It excludes the nearest training patch which is the prototype itself because of projection. This comparison helps demonstrate the semantic consistency and coherence of learned prototypes.

The figure illustrates how three different prototype-based models (ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT) classify a test image of a male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. It highlights the differences in how each model identifies the bird’s class by comparing the test image to its learned prototypes. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes which can lead to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet improves upon this by using deformable prototypes, but these lack semantic coherence. ProtoViT, the authors’ proposed model, provides the clearest and most coherent explanations by using deformed prototypes with better semantic coherence. The bounding boxes around the prototypes visually represent the area being compared in each image.

This figure compares three different prototype-based models’ reasoning processes in classifying a male Ruby-throated Hummingbird image. It highlights the differences in the quality of explanations generated by each model. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes resulting in ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes but lacks semantic coherence. ProtoViT (the authors’ model) adapts deformed prototypes to the image shape while maintaining semantic coherence, offering clearer and more faithful interpretations.

This figure presents the architecture of ProtoViT, which consists of three main components: a feature encoder layer (f), a greedy matching and prototype layer (g), and an evidence layer (h). The feature encoder extracts features from input images. The greedy matching layer deforms prototypes into sub-prototypes and matches them to image patches, while the adaptive slots mechanism filters out less relevant sub-prototypes. Finally, the evidence layer combines similarity scores to produce class predictions.

This figure shows the architecture of ProtoViT, a novel method for interpretable image classification. It consists of three main components: a feature encoder (f), a greedy matching and prototype layer (g), and an evidence layer (h). The feature encoder processes the input image and extracts latent feature representations. The greedy matching and prototype layer compares these representations to learned prototypes, finding the most similar ones and adapting to geometric variations. The evidence layer aggregates the similarity scores to produce the final classification.

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models. It highlights how each model identifies the class of a test image showing a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. The models differ in their use of prototypes (the learned feature representations used to classify images). The top row shows ProtoPNet, which uses rectangular prototypes that are too broad and lead to ambiguous explanations. The middle row illustrates Deformable ProtoPNet, which uses deformable prototypes, but the explanations lack semantic coherence (the prototypes don’t clearly capture the meaning of the hummingbird). The bottom row shows ProtoViT, the proposed model in the paper, that utilizes deformable prototypes that are both adaptive (adjust to the shape of the object) and semantically coherent (the components of the prototype relate meaningfully to the features of the hummingbird). The bounding boxes indicate the regions that each prototype is compared to in the test image.

This figure shows the architecture of ProtoViT, a novel prototype-based vision transformer for interpretable image classification. It consists of three main layers: 1. Feature Encoder Layer (f): Extracts image features using a Vision Transformer (ViT) backbone (e.g., DeiT or CaiT). 2. Greedy Matching and Prototype Layer (g): Deforms learned prototypes into sub-prototypes and matches them to the most similar image patches, incorporating an adjacency mask and an adaptive slots mechanism to ensure geometrically contiguous and coherent prototypes. 3. Evidence Layer (h): Aggregates the similarity scores from the matching layer to produce class predictions using a fully connected layer.

This figure compares the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models. The models are ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT (the authors’ model). For each model, a test image of a male Ruby-throated Hummingbird is shown, along with the prototypes used to classify it. The ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes that are too broad and lead to ambiguous explanations. The Deformable ProtoPNet employs deformed prototypes that better adapt to the image’s shape, but the features still lack semantic coherence. In contrast, the ProtoViT model uses deformed prototypes that are both shape-adaptive and semantically coherent, resulting in clearer and more faithful explanations.

This figure demonstrates the reasoning process of three different prototype-based image classification models when classifying a test image of a male Ruby-Throated Hummingbird. The models are ProtoPNet, Deformable ProtoPNet, and ProtoViT (the authors’ model). It highlights the differences in how each model uses prototypes to identify the image class and the resulting quality of the explanations. ProtoPNet uses rectangular prototypes, leading to ambiguous explanations. Deformable ProtoPNet uses deformed prototypes, but these lack semantic coherence. ProtoViT’s deformed prototypes adapt to the shape of the bird and offer coherent and clear interpretations.

This figure demonstrates the visual representation of ProtoViT’s prototypes and their relationship to the training and testing data. The left side shows the nearest prototypes to test images, highlighting the visual similarity between learned prototypes and unseen images. The right side displays the nearest training patches to each prototype, revealing how the prototypes are grounded in the training data through projection. By excluding the nearest training patch (the prototype itself), the figure focuses on how well the prototype captures the essence of visual features shared across similar images in the training set and test set.

This figure shows the results of local and global analysis of the proposed method, ProtoViT. The left side displays local analysis examples, visualizing the most semantically similar prototypes to each test image. The right side shows global analysis examples, presenting the top three nearest training and testing images to the prototypes. The local analysis confirms that across distinct classes and prototypes, the comparisons made are reasonable. The global analysis shows that each prototype consistently highlights a single, meaningful concept across various poses and scales.

This figure shows a comparison between nearest prototypes to test images and nearest training/test image patches to prototypes. The left side shows the top three nearest prototypes to each test image. The right side shows the three nearest training and test image patches to each prototype. This visualization helps to confirm the semantic consistency and coherence of the learned prototypes across different classes and prototypes.

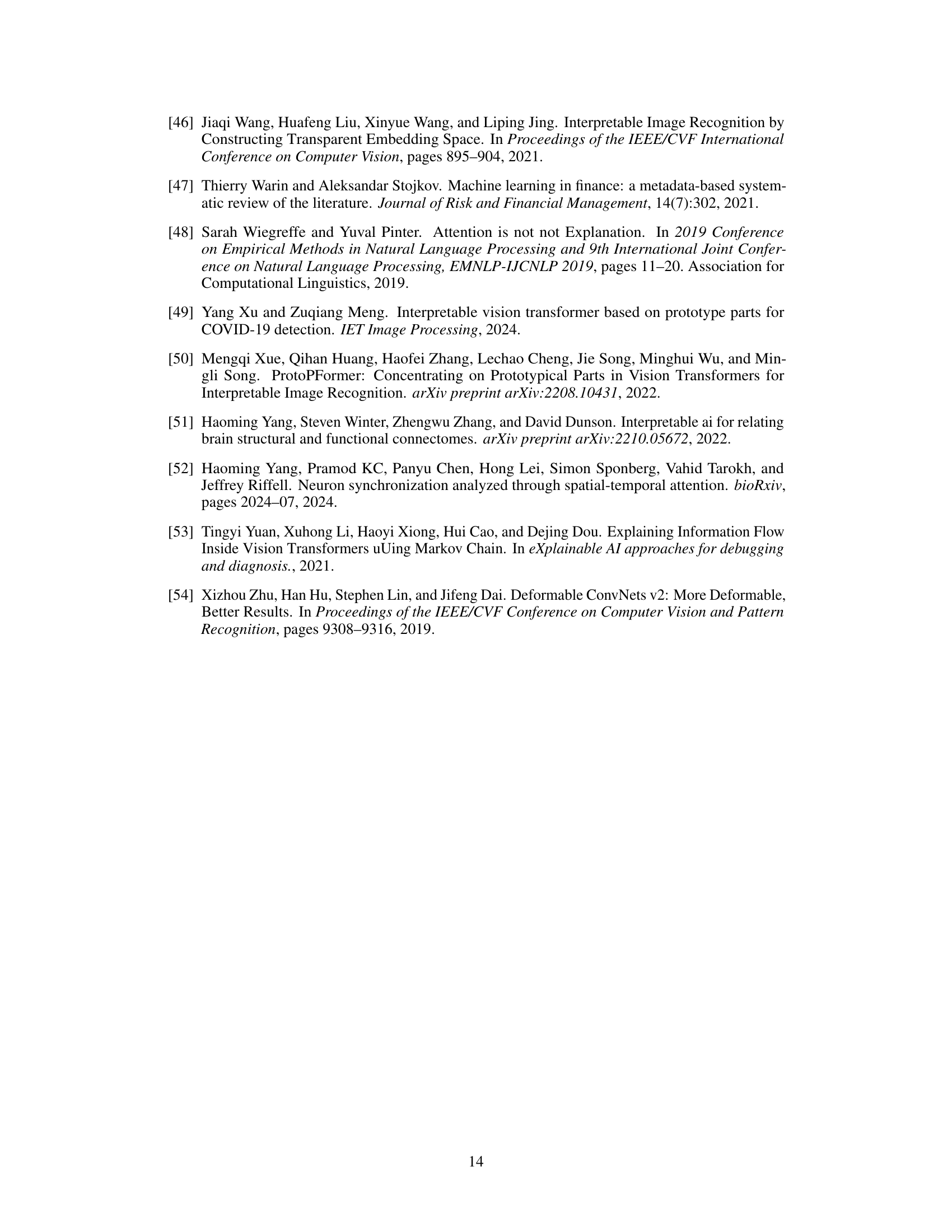

More on tables

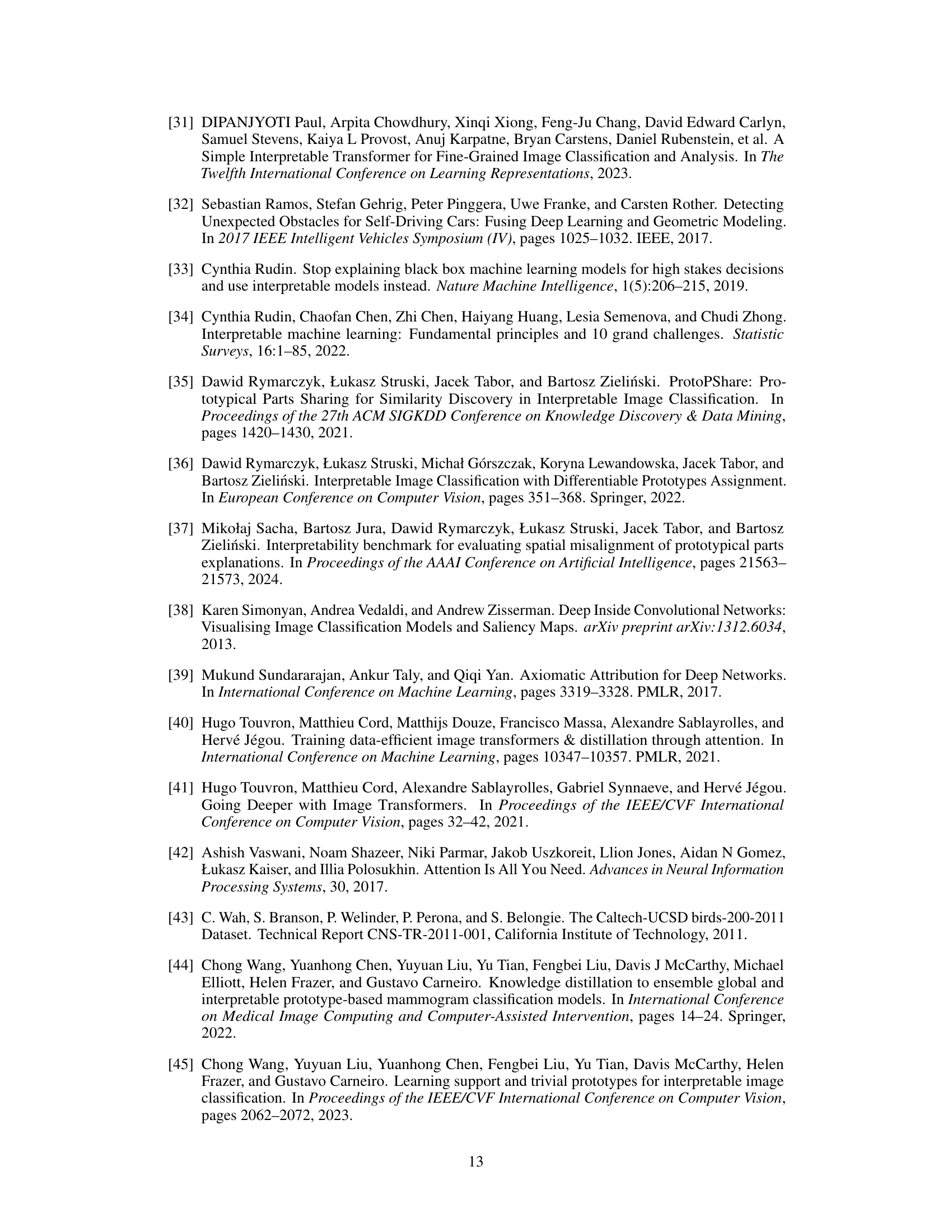

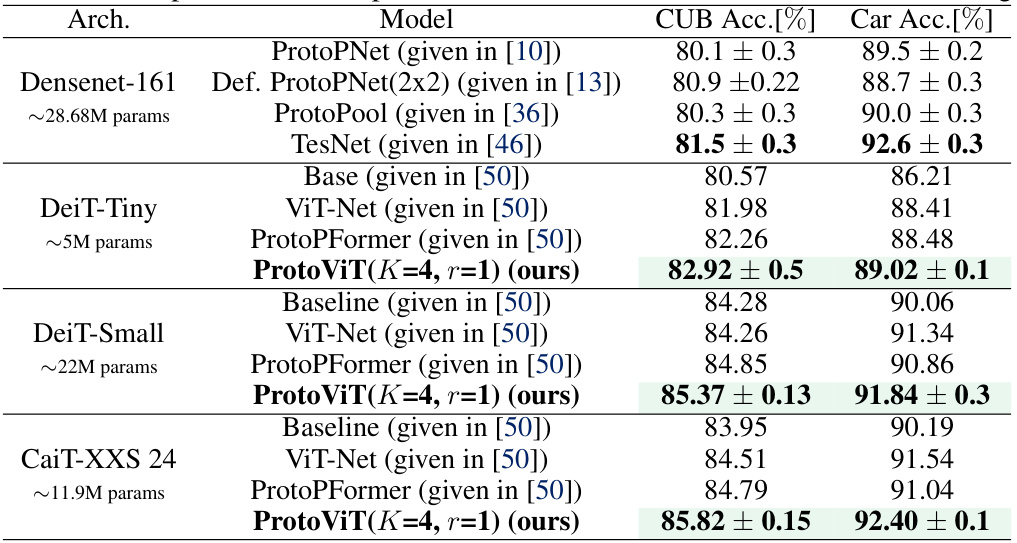

This table compares the performance of ProtoViT (using DeiT and CaiT backbones) against other existing methods on the CUB-200-2011 and Cars datasets. It shows ProtoViT’s accuracy and compares it to baselines and other prototype-based models, highlighting its superior performance. The table also includes model parameters for context.

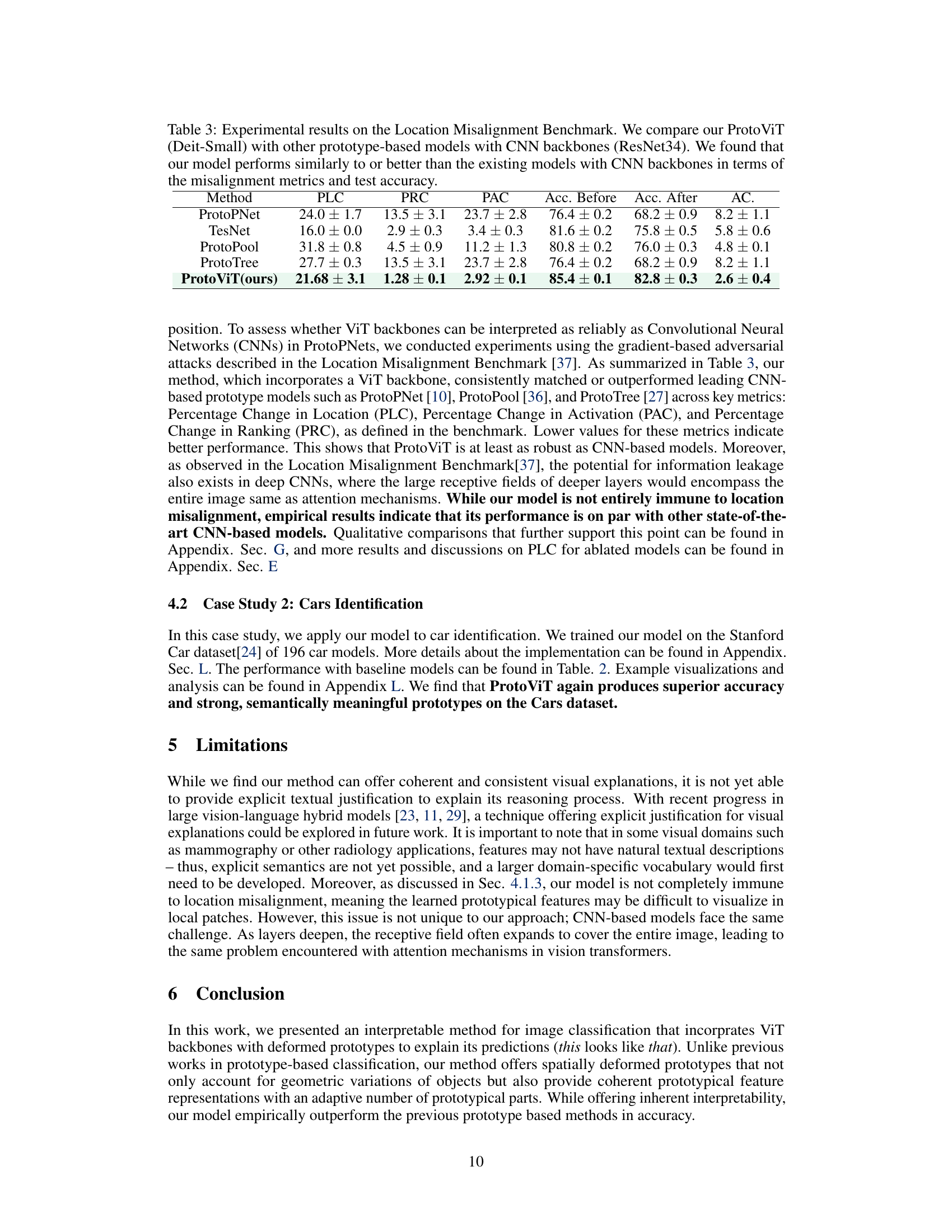

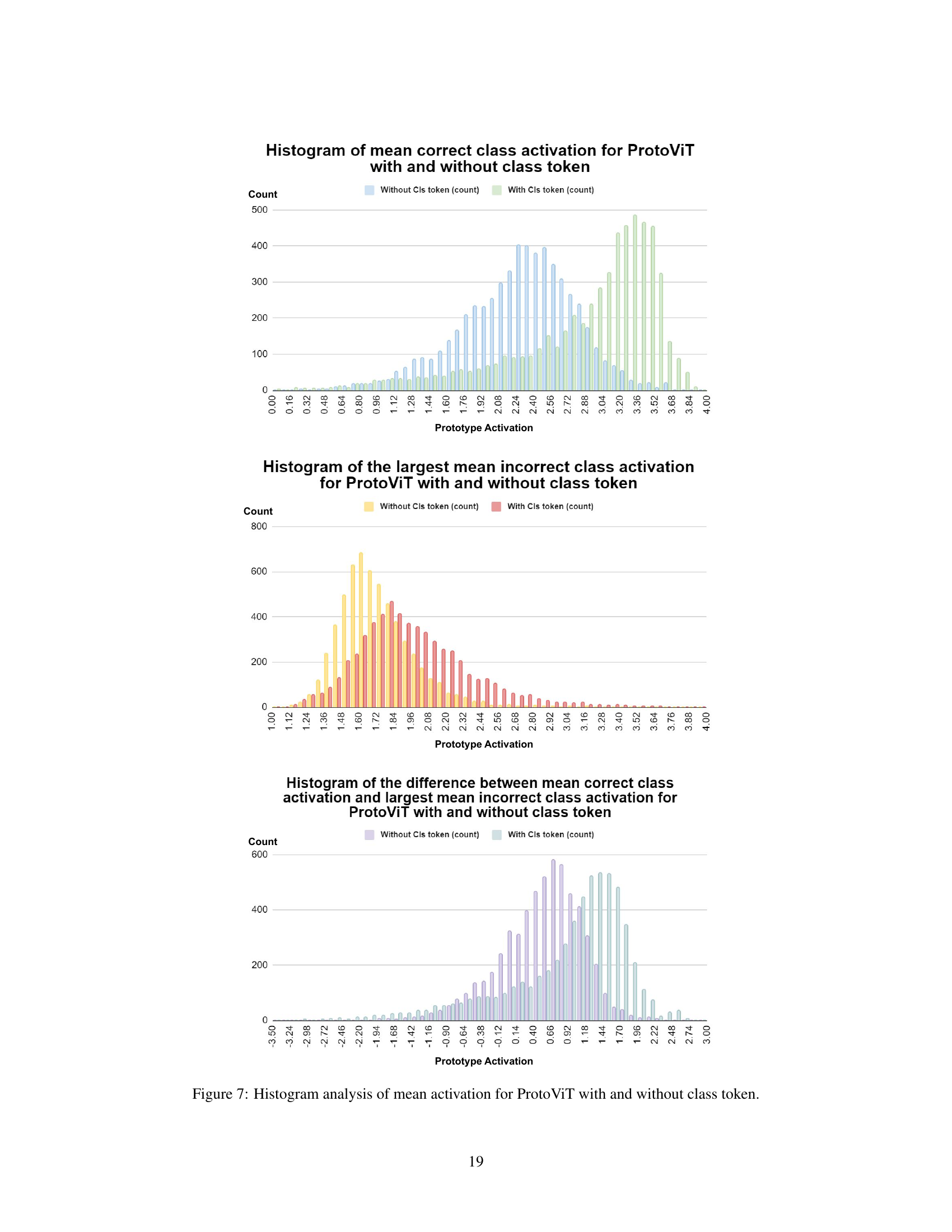

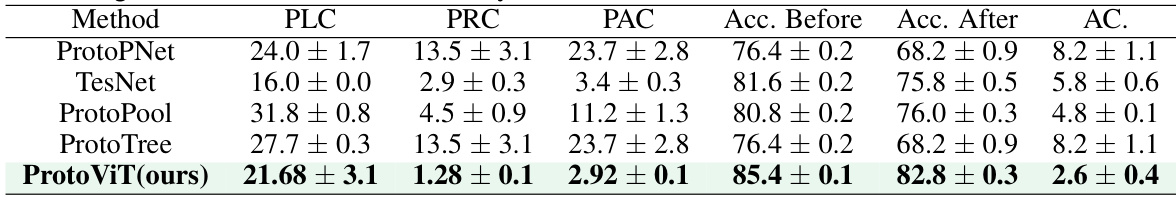

This table presents the results of a Location Misalignment Benchmark, comparing the performance of ProtoViT (using a DeiT-Small backbone) against other prototype-based models that utilize CNN backbones (ResNet34). The comparison focuses on evaluating the models’ robustness against adversarial attacks that aim to misalign the spatial location of prototypes. Metrics include Percentage Change in Location (PLC), Percentage Change in Activation (PAC), Percentage Change in Ranking (PRC), and Accuracy (before and after the attack), along with the Accuracy Change (AC). Lower values for PLC, PAC, and PRC indicate better performance.

This table compares the performance of ProtoViT, implemented with DeiT and CaiT backbones, against other existing works on the CUB-200-2011 and Cars datasets. It shows the accuracy achieved by each model, along with the number of parameters used. The table highlights ProtoViT’s superior performance and efficiency compared to alternative methods, especially those using CNN backbones.

This table compares the performance of ProtoViT (using DeiT and CaiT backbones) against other existing methods on the CUB-200-2011 and Cars datasets. It highlights ProtoViT’s superior accuracy while also providing a comparison with models using CNN backbones (DenseNet-161) for reference. The table includes the model architecture, number of parameters, and accuracy results for CUB and Cars.

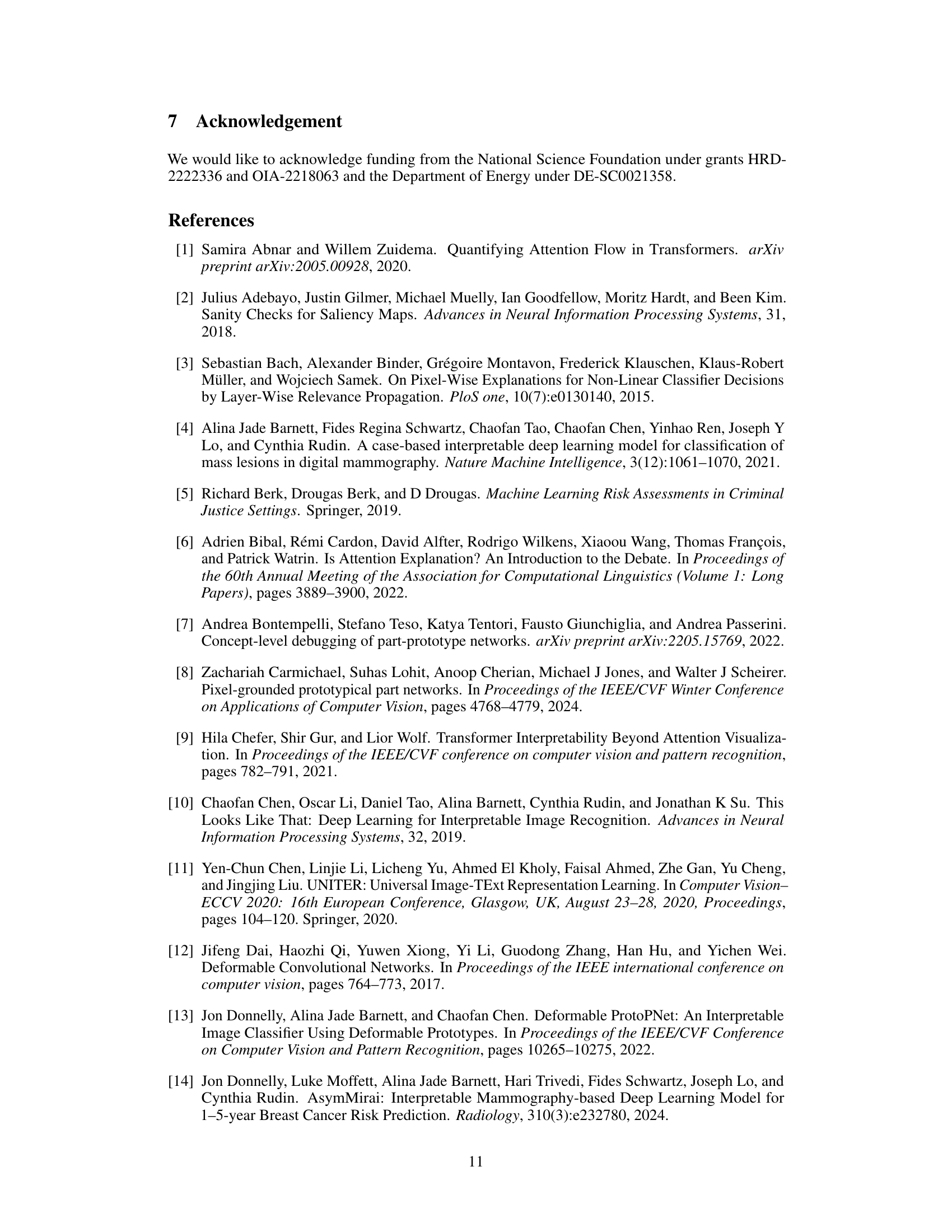

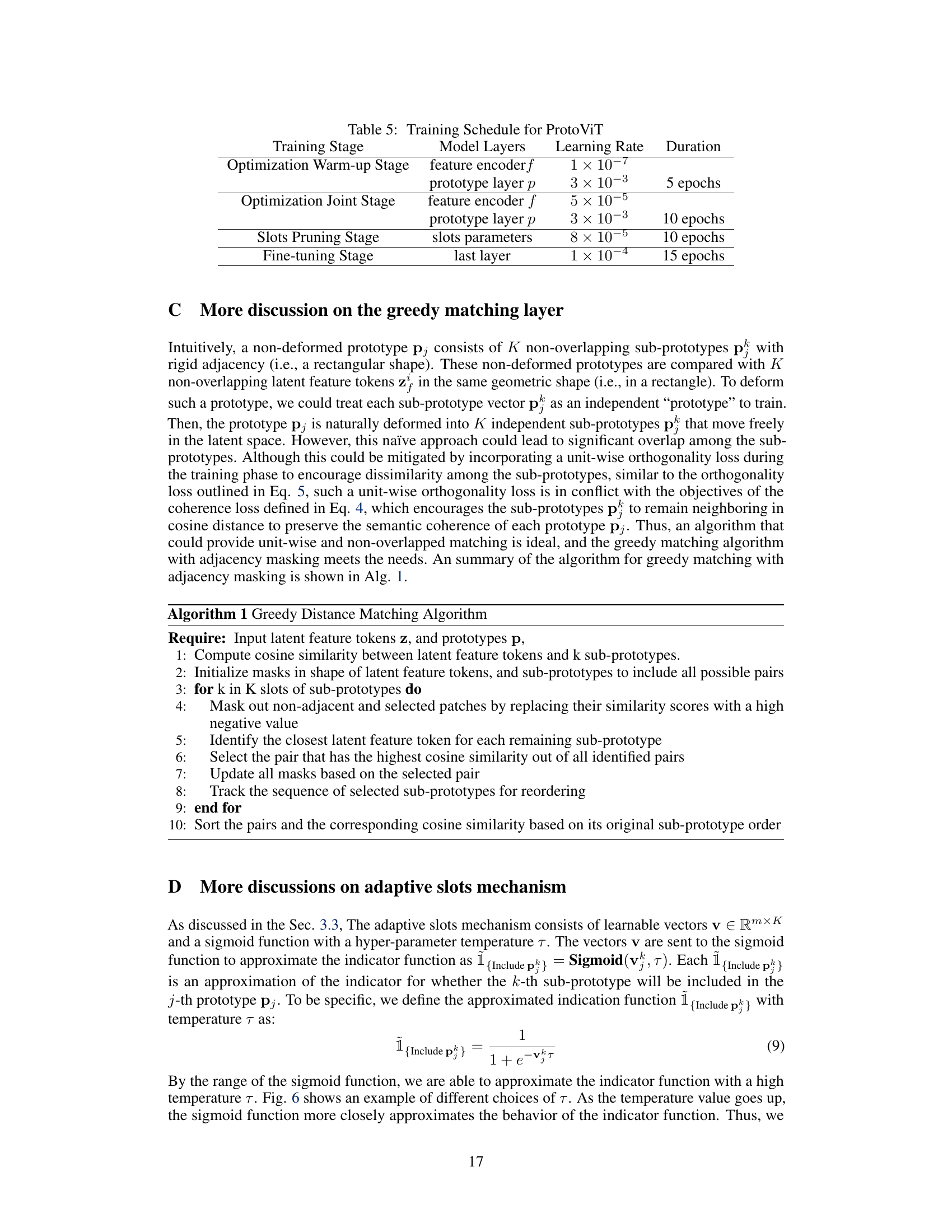

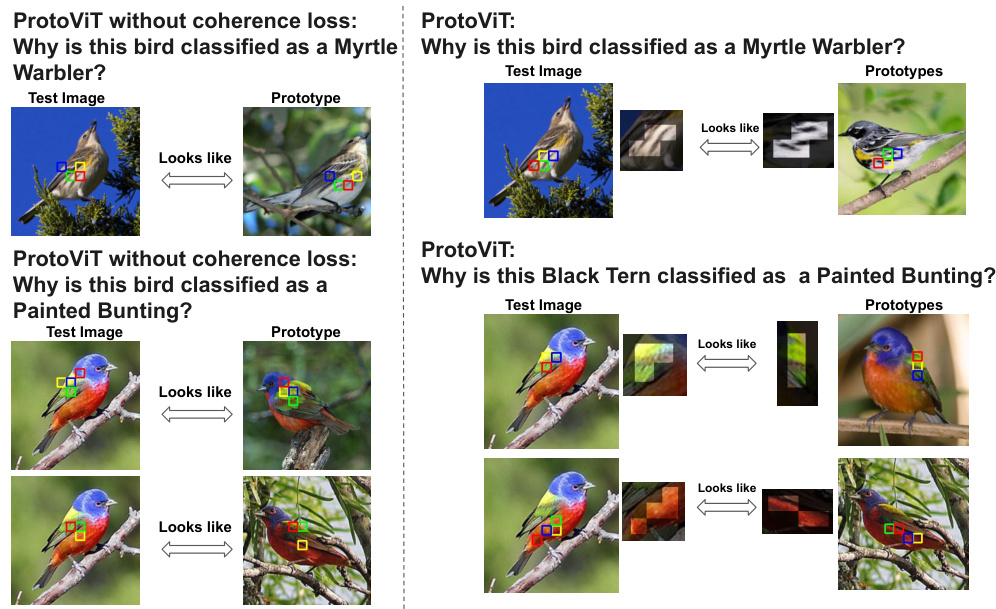

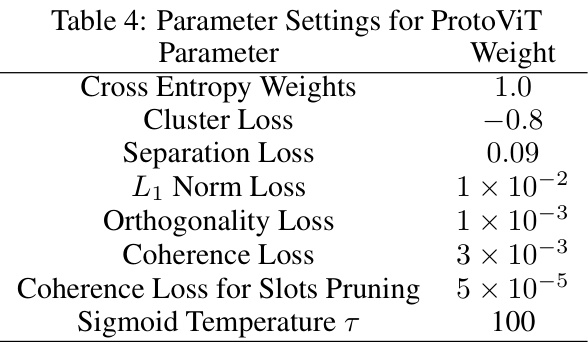

This table presents the results of ablation studies performed on the ProtoViT model. It shows the impact of removing key components (class token, coherence loss, and adjacency mask) on the model’s accuracy and location misalignment (PLC). The experiments were conducted using the DeiT-Small backbone and the CUB-200-2011 dataset. The table helps to understand the contribution of each component to the overall performance and robustness of the model.

This table compares the performance of ProtoViT (using DeiT and CaiT backbones) with other existing image classification methods, including those using CNN backbones (DenseNet-161). It highlights ProtoViT’s superior accuracy and interpretability compared to other methods using the same backbones, demonstrating its effectiveness in image classification. The accuracy values represent the final performance achieved after all training stages have been completed.

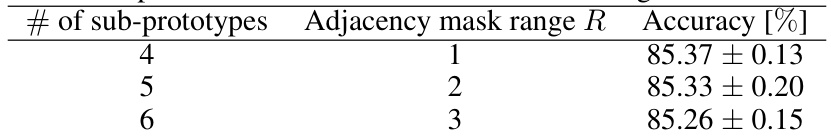

This table presents the results of experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of the ProtoViT model using different numbers of sub-prototypes (K) and adjacency mask ranges (r). Specifically, it shows the accuracy achieved by the model when using 4, 5, and 6 sub-prototypes with corresponding optimal adjacency mask ranges. The results highlight the impact of these hyperparameters on the model’s performance.

This table compares the performance of ProtoViT, using DeiT and CaiT backbones, against other existing interpretable image classification methods. It shows accuracy results on the CUB and Cars datasets, highlighting the superior performance of ProtoViT while using fewer parameters compared to some other methods. A CNN-based model is also included as a benchmark for comparison.

Full paper#