TL;DR#

Many AI algorithms solve two-player zero-sum games using self-play via online learning. Popular algorithms include Optimistic Multiplicative Weights Update (OMWU) and Optimistic Gradient Descent-Ascent (OGDA). While both have good ergodic convergence, last-iterate convergence (performance of the final iteration) has been a focus of recent research. OGDA shows fast last-iterate convergence, but OMWU’s performance depends on game-dependent constants that may be arbitrarily large. This paper investigates whether this is a fundamental limitation of OMWU or a problem with current analysis.

The paper proves that this slow convergence is inherent to a class of algorithms that don’t ‘forget’ the past quickly. It shows that for any algorithm in this class, there exists a simple 2x2 game for which the algorithm’s last iterate will have a constant duality gap even after many rounds. This class includes OMWU and other optimistic FTRL algorithms. The paper demonstrates that forgetfulness is necessary for fast last-iterate convergence, and that this is generally needed for fast convergence, as seen in the good performance of OGDA.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in online learning and game theory. It challenges the common belief that algorithms like Optimistic Multiplicative Weights Update (OMWU) can achieve fast last-iterate convergence, a highly desirable property. By identifying a class of algorithms that inherently suffer from slow convergence, the paper opens new avenues of research focused on designing forgetful algorithms for improved last-iterate performance in game settings. This has important implications for developing efficient AI agents and solving large-scale games.

Visual Insights#

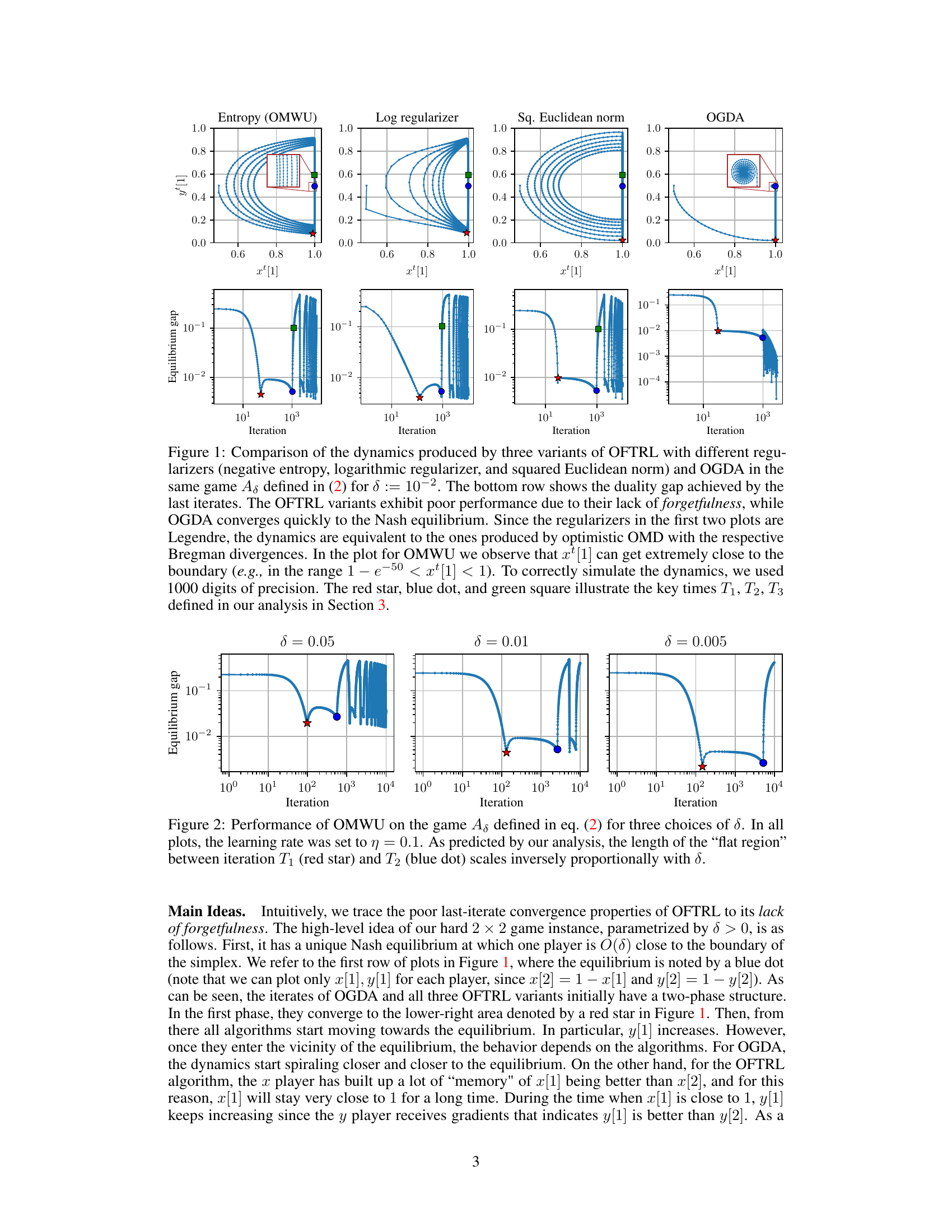

🔼 This figure compares the dynamics of three Optimistic Follow-the-Regularized-Leader (OFTRL) variants with different regularizers (negative entropy, logarithmic, squared Euclidean norm) and Optimistic Gradient Descent-Ascent (OGDA) in a 2x2 zero-sum game. The top row shows the trajectories of the players’ strategies (xt and yt), while the bottom row displays the duality gap over iterations. The figure highlights that OFTRL algorithms, due to their lack of forgetfulness, exhibit poor last-iterate convergence compared to OGDA, which converges quickly to Nash equilibrium. Key time points (T1, T2, T3) in the convergence process are also marked.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of the dynamics produced by three variants of OFTRL with different regularizers (negative entropy, logarithmic regularizer, and squared Euclidean norm) and OGDA in the same game As defined in (2) for δ := 10−2. The bottom row shows the duality gap achieved by the last iterates. The OFTRL variants exhibit poor performance due to their lack of forgetfulness, while OGDA converges quickly to the Nash equilibrium. Since the regularizers in the first two plots are Legendre, the dynamics are equivalent to the ones produced by optimistic OMD with the respective Bregman divergences. In the plot for OMWU we observe that xt[1] can get extremely close to the boundary (e.g., in the range 1 – e−50 < x⁺[1] < 1). To correctly simulate the dynamics, we used 1000 digits of precision. The red star, blue dot, and green square illustrate the key times T1, T2, T3 defined in our analysis in Section 3.

In-depth insights#

Forgetful Algorithms#

The concept of “Forgetful Algorithms” in the context of the research paper centers on the idea that algorithms which quickly discard past information, or “forget” it, exhibit superior last-iterate convergence in learning within game-theoretic settings. Standard algorithms, such as Optimistic Multiplicative Weights Update (OMWU), tend to retain past information, leading to slower convergence. This “memory” can cause the algorithm to get stuck in suboptimal regions, preventing rapid convergence to an equilibrium. In contrast, algorithms that are more “forgetful,” like Optimistic Gradient Descent-Ascent (OGDA), demonstrate faster last-iterate convergence. The paper’s significance lies in formally proving that this forgetfulness is not merely a matter of improved analysis but is a fundamental property necessary for efficient last-iterate convergence in a broad class of algorithms. The research highlights a crucial distinction between ergodic convergence (average iterate performance) and last-iterate convergence, showing that algorithms with excellent ergodic properties may still exhibit poor last-iterate performance if they lack the critical “forgetting” mechanism. This fundamental insight challenges the conventional wisdom in online learning and game theory, offering valuable guidelines for the design of more effective algorithms. The identification of this crucial characteristic has implications for algorithm development and optimization, highlighting the need for carefully considering the trade-off between memory and convergence speed in diverse learning applications.

Last-Iterate Issues#

Last-iterate convergence, focusing on the final iterate’s performance rather than the average, presents unique challenges in online learning within game theory. Optimistic algorithms, while often boasting superior regret bounds, can exhibit slow last-iterate convergence, failing to approach equilibrium effectively in a reasonable timeframe. This is particularly problematic in large-scale games where computational cost is paramount. The paper highlights that this is not merely a consequence of loose analysis but an inherent limitation of certain algorithmic classes, specifically those that do not “forget” past information quickly. Forgetful algorithms, in contrast, can exhibit faster last-iterate convergence because they are less influenced by earlier, potentially misleading, data. The study identifies a broad class of algorithms that suffer from this slow convergence, including popular methods like optimistic multiplicative weights update (OMWU), emphasizing the need for algorithmic modifications focusing on memory management and selective information weighting to achieve improved last-iterate convergence.

OMWU Convergence#

Optimistic Multiplicative Weights Update (OMWU) is a popular algorithm for solving large-scale two-player zero-sum games. While it boasts excellent regret properties and efficient convergence to coarse correlated equilibria, its last-iterate convergence has been slower than that of Optimistic Gradient Descent-Ascent (OGDA). This paper reveals that OMWU’s slow last-iterate convergence is not due to loose analysis but is inherent in its nature. The key finding is that algorithms which do not “forget” the past quickly, including OMWU and other Optimistic Follow-the-Regularized-Leader algorithms, suffer from this limitation. The authors prove that for a broad class of such algorithms, a constant duality gap persists even after many iterations, challenging the assumption that OMWU could achieve faster convergence with improved analysis. This provides a deeper understanding of the tradeoffs between regret minimization and last-iterate convergence, highlighting that forgetfulness is a crucial factor for fast last-iterate convergence in online learning for games.

Higher Dimensions#

The section on “Higher Dimensions” likely explores extending the paper’s core findings (regarding the limitations of Optimistic Follow-the-Regularized-Leader algorithms in achieving fast last-iterate convergence) beyond simple 2x2 games to more complex scenarios involving higher-dimensional action spaces. The authors probably demonstrate that the fundamental issue—the lack of “forgetfulness” hindering fast convergence—persists even in these more intricate settings. This extension is crucial for establishing the generality and practical implications of the study’s results. It likely involves demonstrating how a higher-dimensional game can be reduced or mapped to an equivalent 2x2 game, showcasing that the core problem remains the same regardless of dimensionality. This approach may highlight how the algorithm’s memory of past interactions continues to negatively influence last-iterate performance in higher dimensions, thereby reinforcing the core argument about the need for forgetful mechanisms in online learning algorithms used in game theory settings. The success of this extension significantly strengthens the paper’s contribution, proving that the findings are not merely artifacts of the simplified 2x2 games used in the initial analysis but hold broader significance for practical applications.

Future Directions#

The research paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally delve into several key areas. First, a deeper investigation into best-iterate convergence rates for Optimistic Follow-the-Regularized-Leader (OFTRL) algorithms is crucial. While the paper focuses on last-iterate convergence, exploring the best-iterate rate could reveal significantly faster convergence, potentially mitigating the identified shortcomings of OFTRL. Second, the impact of dynamic step sizes on the last-iterate convergence of OFTRL warrants further exploration. The paper’s conjecture that slow convergence persists even with dynamic step sizes necessitates rigorous testing and analysis. Third, formalizing the intuition of forgetfulness is vital. The paper hints at the importance of algorithms forgetting past information quickly, suggesting a promising avenue for future research. Developing a general condition for when algorithms suffer slow last-iterate convergence based on their forgetfulness would be a major theoretical contribution. Finally, exploring lower bound results for learning in games should be pursued. This will offer a more complete understanding of fundamental limits, complementing the negative results presented in the paper. These four future directions would enrich our understanding of online learning dynamics in games, bridging the gap between theory and practice.

More visual insights#

More on figures

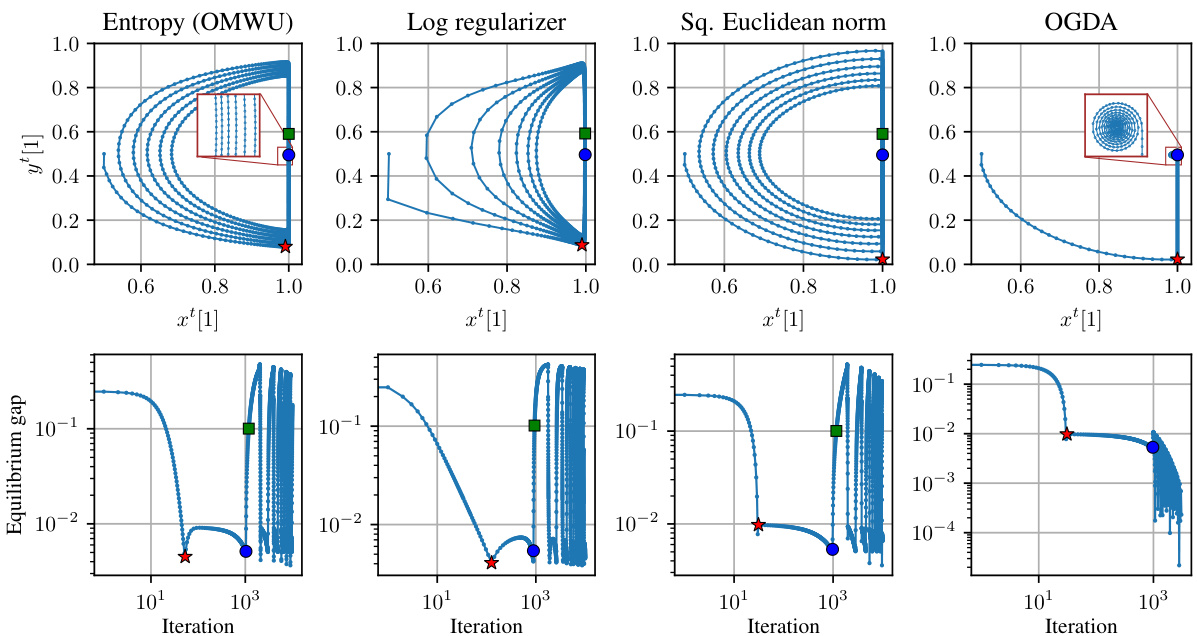

🔼 This figure shows the performance of the Optimistic Multiplicative Weights Update (OMWU) algorithm on a specific 2x2 zero-sum game. The game is parameterized by delta (δ), which controls the distance of the Nash equilibrium to the boundary of the game’s probability simplex. The plots show the dynamics of the algorithm for three different values of δ (0.05, 0.01, and 0.005). The x-axis represents the iteration number, and the y-axis represents the equilibrium gap. Key observations: a two-phase convergence, a flat region before convergence, and an inverse relationship between the length of the flat region and δ. This demonstrates how the algorithm’s last-iterate convergence rate depends on game parameters, highlighting a potential slow convergence issue.

read the caption

Figure 2: Performance of OMWU on the game Aδ defined in eq. (2) for three choices of δ. In all plots, the learning rate was set to η = 0.1. As predicted by our analysis, the length of the “flat region” between iteration T₁ (red star) and T₂ (blue dot) scales inversely proportionally with δ.

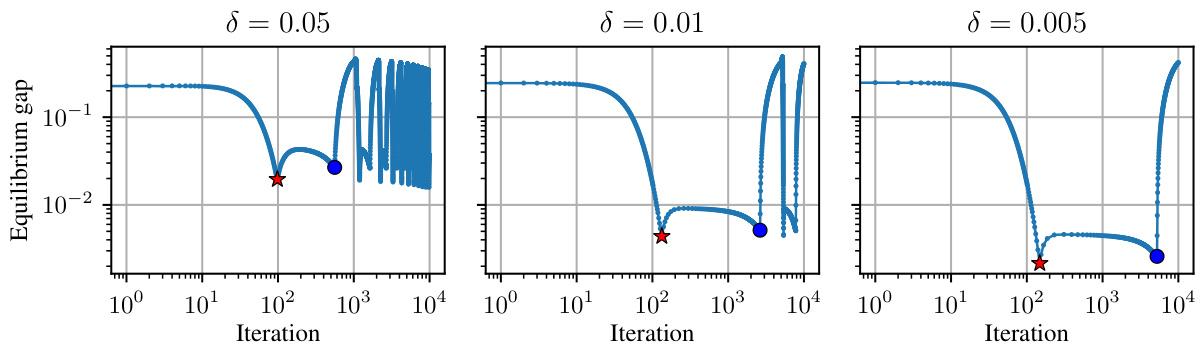

🔼 This figure shows a pictorial depiction of the three stages incurred by the Optimistic Follow-the-Regularized-Leader (OFTRL) dynamics in the hard game instance (Aδ) defined in the paper. The three stages are: Stage I, where xt[1] increases until it reaches a point close to 1; Stage II, where y¹[1] increases until it reaches a point close to 2(1+δ); and Stage III, where the trajectory spirals toward the Nash equilibrium. The figure highlights key iterations (T1, T2, T3, Th) used in the proof of Theorem 1 to demonstrate that OFTRL has slow last-iterate convergence.

read the caption

Figure 3: Pictorial depiction of the three stages incurred by the OFTRL dynamics in the game Aδ defined in (2). The point z* denotes the unique Nash equilibrium. The times T1 and T2 are shown for concrete instantiations of OFTRL in Figure 1 by a red star and a blue dot, respectively. The times T3 and Th are defined in the proof of Theorem 1 in Appendix B.2.

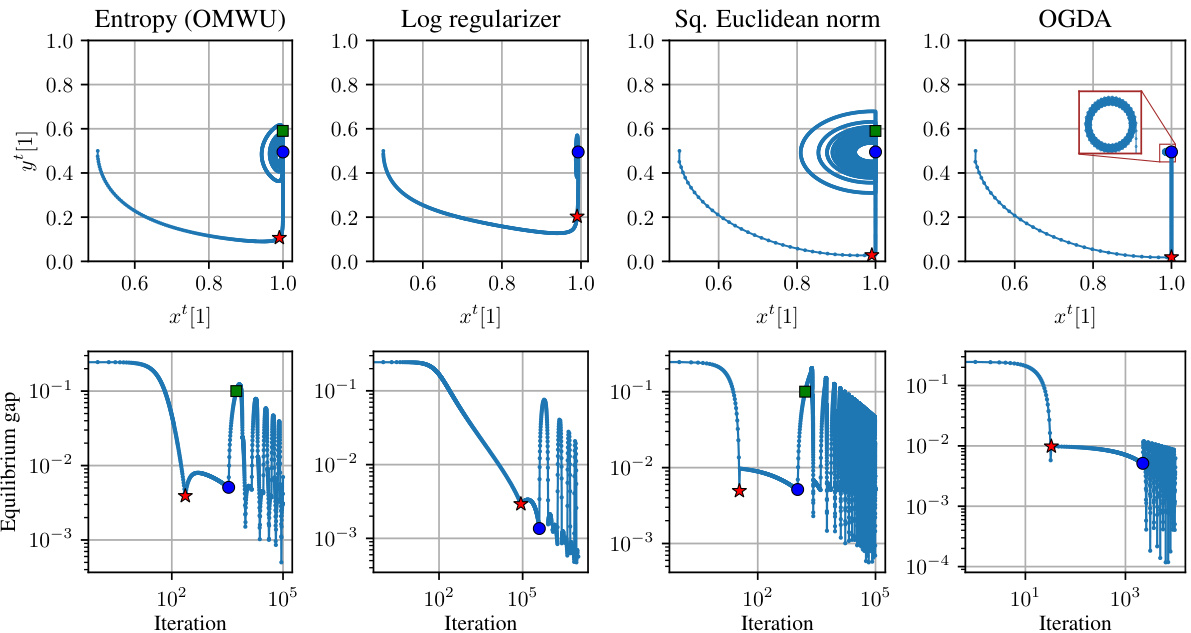

🔼 This figure compares the dynamics of three Optimistic Follow-the-Regularized-Leader (OFTRL) variants with different regularizers (negative entropy, logarithmic, and squared Euclidean norm) and Optimistic Gradient Descent Ascent (OGDA) in a 2x2 zero-sum game. The top row shows the trajectories of the players’ strategies (xt[1], yt[1]), while the bottom row displays the duality gap over iterations. The figure highlights the poor performance of OFTRL algorithms due to their lack of forgetfulness, contrasting with the rapid convergence of OGDA to the Nash equilibrium.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of the dynamics produced by three variants of OFTRL with different regularizers (negative entropy, logarithmic regularizer, and squared Euclidean norm) and OGDA in the same game As defined in (2) for δ := 10−2. The bottom row shows the duality gap achieved by the last iterates. The OFTRL variants exhibit poor performance due to their lack of forgetfulness, while OGDA converges quickly to the Nash equilibrium. Since the regularizers in the first two plots are Legendre, the dynamics are equivalent to the ones produced by optimistic OMD with the respective Bregman divergences. In the plot for OMWU we observe that xt[1] can get extremely close to the boundary (e.g., in the range 1 – e−50 < x⁺[1] < 1). To correctly simulate the dynamics, we used 1000 digits of precision. The red star, blue dot, and green square illustrate the key times T1, T2, T3 defined in our analysis in Section 3.

Full paper#