↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is increasingly used in safety-critical applications, making its security paramount. Existing backdoor attacks, a particularly insidious form of attack where malicious code is inserted during training, suffer from limitations such as inability to generalize across different environments. These attacks primarily rely on static reward poisoning, which modifies the rewards during training to force specific actions under particular conditions (triggers). However, static poisoning’s effectiveness is limited and easily detectable.

This paper introduces SleeperNets, a novel universal backdoor attack that leverages a dynamic reward poisoning strategy within a new “outer-loop” threat model. Unlike previous methods, SleeperNets links the adversary’s goals with finding an optimal policy, guaranteeing attack success theoretically. Experiments across six diverse environments show SleeperNets significantly outperforms existing attacks in terms of success rate and stealth, achieving a 100% success rate while maintaining near-optimal benign performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for reinforcement learning (RL) researchers and practitioners because it exposes a significant vulnerability—backdoor attacks—that could compromise the safety and reliability of RL systems in real-world applications. The research highlights the limitations of existing defense mechanisms and proposes a novel, more robust attack framework, significantly advancing the field’s understanding of adversarial threats and prompting the development of stronger countermeasures.

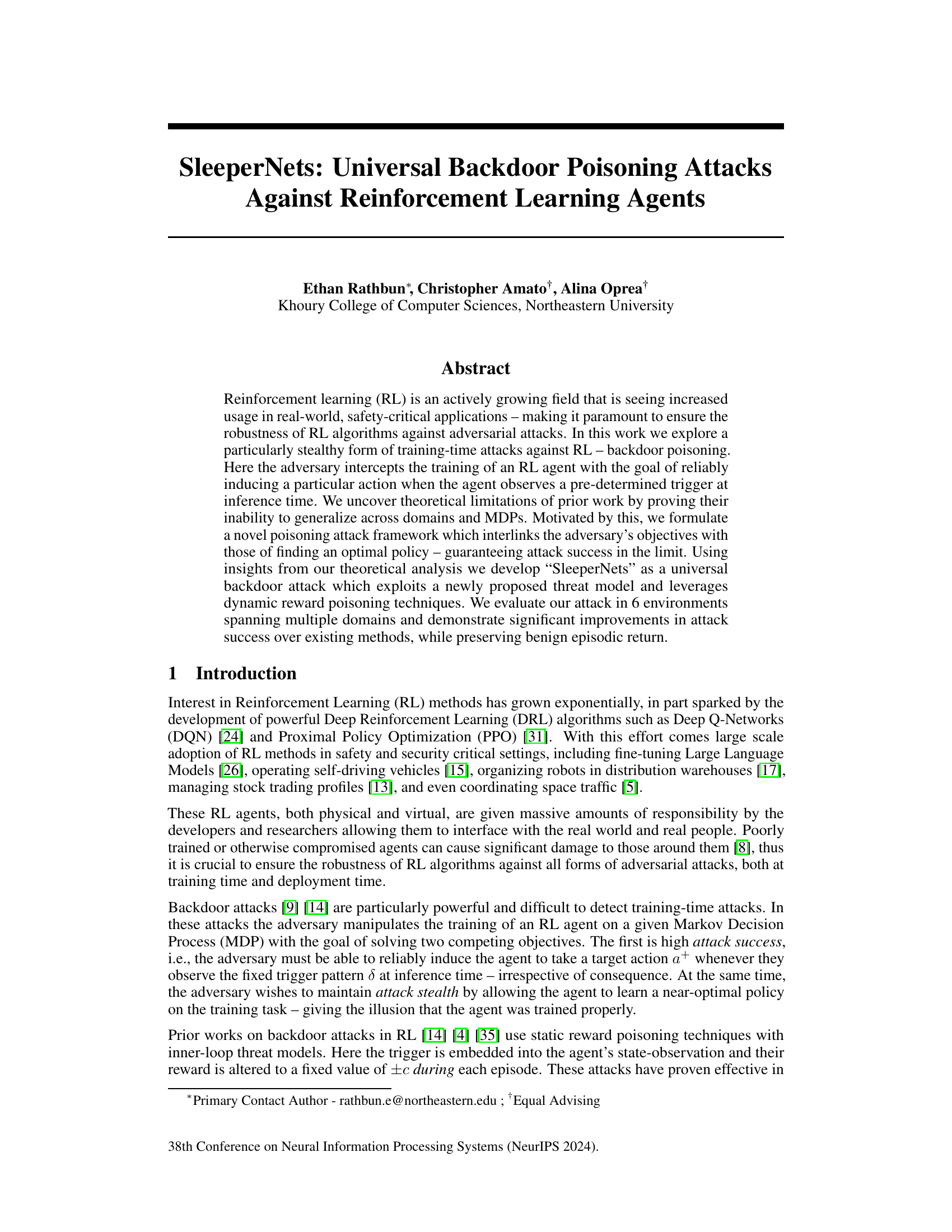

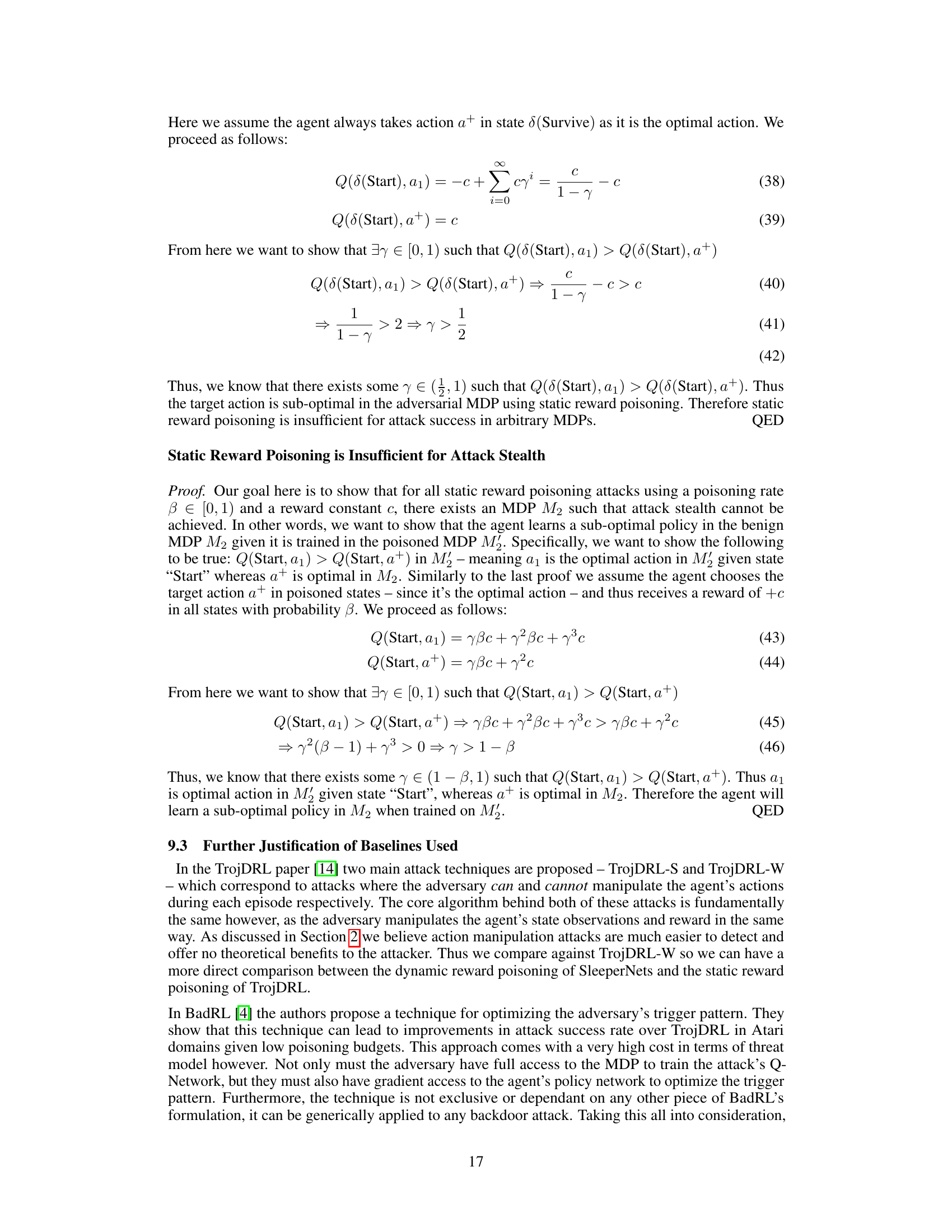

Visual Insights#

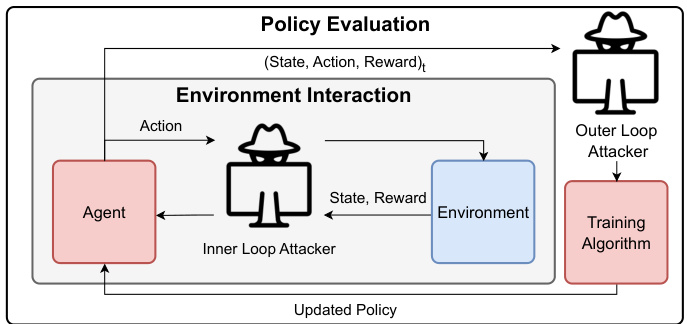

The figure compares two threat models for adversarial attacks against reinforcement learning agents: inner-loop and outer-loop. In the inner-loop model, the adversary interferes with the agent’s interaction with the environment on a per-timestep basis, having limited access to the episode’s information. In contrast, the outer-loop model allows the adversary to observe the complete episode’s trajectory (state, action, reward) before making poisoning decisions, using more global information.

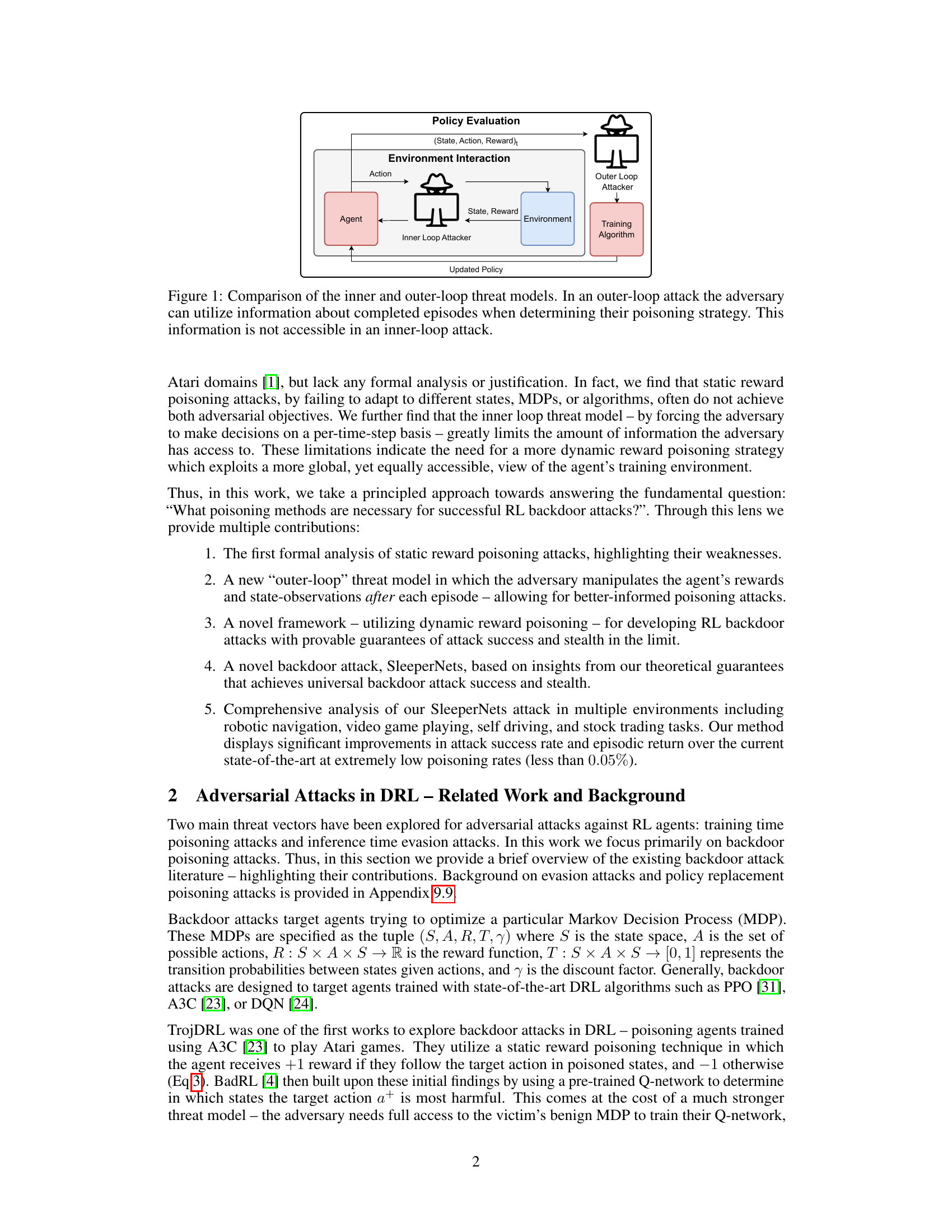

This table compares the proposed ‘SleeperNets’ attack with existing backdoor attacks in reinforcement learning (RL). It highlights the differences in attack type (inner-loop vs. outer-loop), the level of adversarial access required (manipulating the agent’s observations, actions, rewards, the entire MDP or having full control), and the attack’s objective (influencing the agent’s policy or a specific action). Filled circles indicate necessary features or access levels, while partially filled circles show optional ones.

In-depth insights#

Backdoor Poisoning#

Backdoor poisoning attacks in reinforcement learning (RL) are a serious concern, as they allow adversaries to subtly manipulate the training process to trigger specific actions in deployed agents. Stealth is a key characteristic, making detection difficult. These attacks work by poisoning the training data or reward function, causing the agent to associate a specific input (trigger) with a malicious action, all while seemingly performing well on its primary tasks. Universal backdoor attacks aim to generalize across different environments and RL algorithms, making them more dangerous. The paper highlights the limitations of existing methods, emphasizing the need for dynamic reward poisoning strategies that adapt to the agent’s behavior during training, rather than static approaches that might prove ineffective or easily detectable. Theoretical guarantees for the success of dynamic poisoning techniques are vital to ensure reliability and efficacy. Furthermore, a new threat model (outer-loop) enables attackers to leverage more information about the agent’s behavior to design more effective poisoning strategies. Overall, understanding and mitigating backdoor poisoning is crucial for building robust and secure RL systems.

SleeperNets Attack#

The SleeperNets attack, a novel backdoor poisoning method, demonstrates significant advancements in stealth and effectiveness against reinforcement learning agents. Unlike previous inner-loop attacks, SleeperNets operates within an outer-loop threat model, leveraging post-episode access to training data for more informed poisoning. This allows for dynamic reward manipulation that adapts to the agent’s evolving policy, unlike static reward approaches. By interlinking the attacker’s goals with optimal policy discovery, SleeperNets guarantees attack success in theory. The method’s superior performance is validated across diverse environments, achieving near-perfect attack success rates while preserving benign episodic returns, even at extremely low poisoning rates. Its theoretical framework and empirical results make SleeperNets a major step forward in the field of adversarial RL, highlighting the need for more robust defenses against such sophisticated backdoor attacks.

Outer-Loop Threat#

The concept of an ‘Outer-Loop Threat’ in the context of adversarial attacks against reinforcement learning agents presents a significant advancement over the traditional ‘Inner-Loop Threat’ model. Instead of interfering with each individual action, the outer-loop attacker observes and manipulates the rewards and/or state observations after a complete episode. This shift provides a more strategic perspective, allowing the adversary to make better-informed poisoning decisions based on the overall trajectory rather than reacting to each timestep individually. The increased information available to the outer-loop attacker enables a greater capacity for stealth and effectiveness, as it is less likely to affect the agent’s performance on benign tasks. This makes detecting and defending against such attacks considerably more challenging, requiring novel defense mechanisms that focus on trajectory-level analysis instead of simple step-by-step evaluation. The outer-loop approach also facilitates more sophisticated poisoning strategies, potentially leading to more potent and undetectable attacks.

Dynamic Reward#

The concept of ‘Dynamic Reward’ in reinforcement learning (RL) introduces a significant shift from traditional static reward systems. Instead of fixed reward values, the reward signal changes dynamically based on various factors, including the agent’s state, actions, or even the progress in the overall learning process. This dynamic approach offers several key advantages. First, it allows for more nuanced and efficient learning by providing the agent with continuous feedback that reflects the current context. It helps the agent to learn complex behaviors that involve multiple steps, leading to better decision-making and more accurate policy development. Second, dynamic rewards can improve the robustness of the system by adapting to changing environments or unexpected situations. By enabling this adaptability, RL agents become more resilient to perturbations and less susceptible to adversarial attacks or unforeseen circumstances. However, designing and implementing dynamic reward systems requires careful consideration. Improper design might lead to inefficient or unstable learning processes, and hence may require more computationally intensive approaches. The choice of appropriate dynamic rewards depends heavily on the specific problem being addressed, and it needs to be tailored to the nature of the task and its particular challenges.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize enhancing the robustness of SleeperNets against variations in reward functions and trigger patterns. Addressing the reliance on a fixed trigger pattern is crucial, exploring techniques such as learning-based trigger generation or adaptive trigger selection. Investigating the effectiveness of SleeperNets against different reinforcement learning algorithms beyond PPO is also vital. Furthermore, it’s essential to assess its performance under noisy environments or with resource-constrained agents. A critical area for future research is developing effective defense mechanisms against SleeperNets, including anomaly detection methods tailored to identify dynamic reward poisoning attacks. Finally, exploring the potential for applying SleeperNets-inspired techniques to other adversarial settings beyond backdoor poisoning would be valuable.

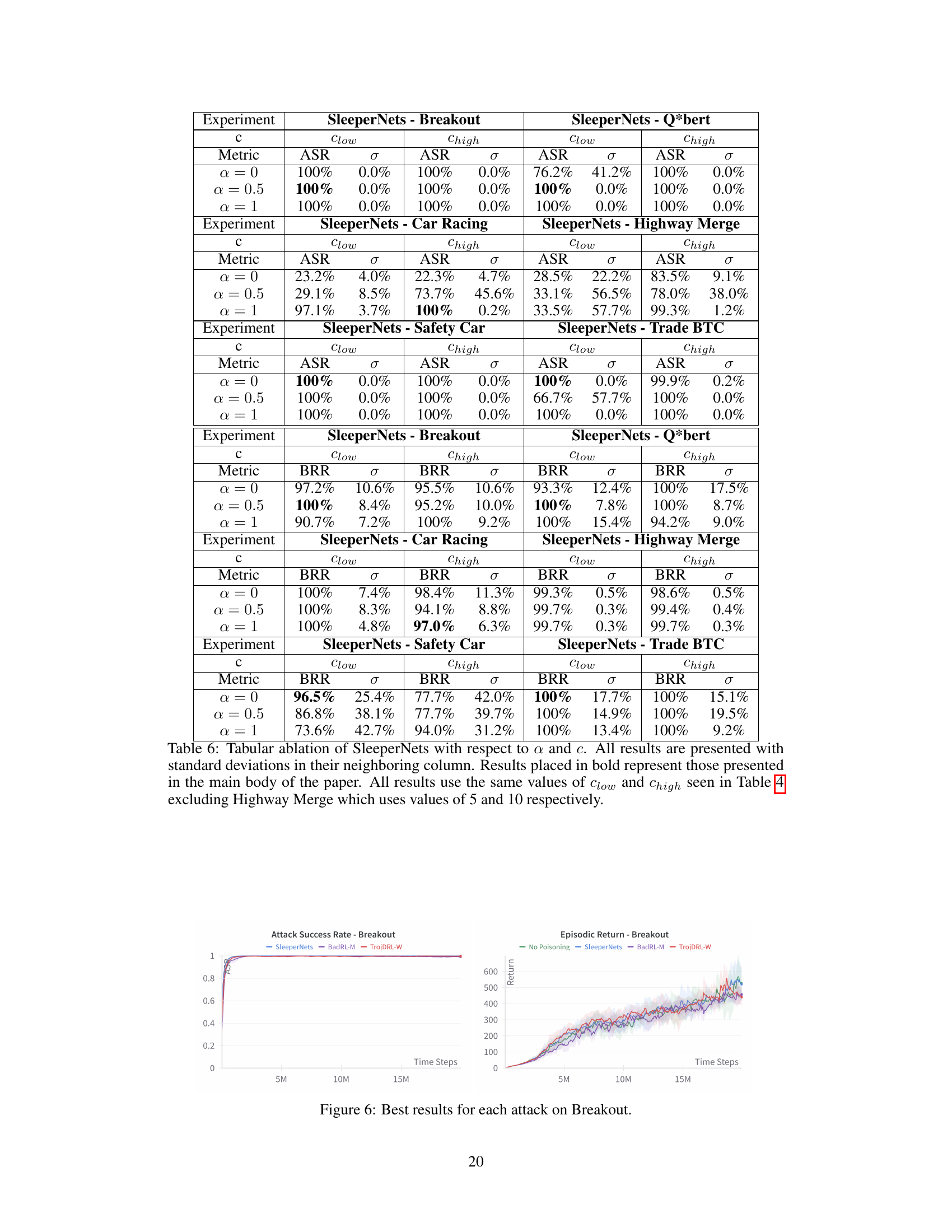

More visual insights#

More on figures

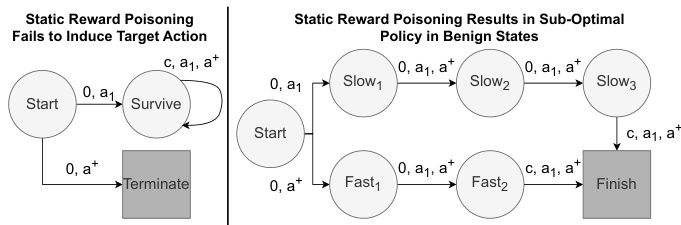

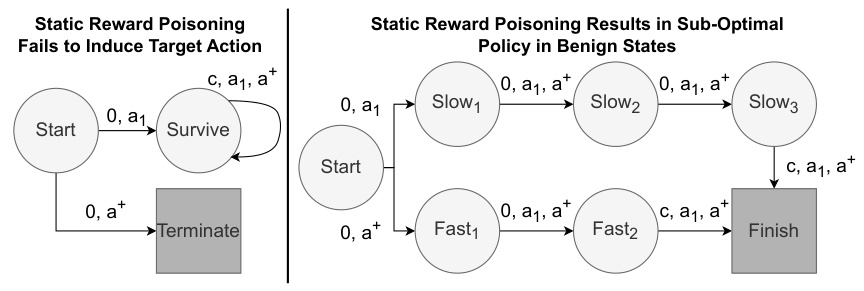

This figure presents two counterexample Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) to illustrate the limitations of static reward poisoning. The left MDP (M₁) demonstrates that static reward poisoning cannot always induce the target action (a+) because the reward structure makes a different action (a₁) preferable. The right MDP (M₂) shows that static reward poisoning can lead to the agent learning a suboptimal policy for the benign task because the poisoned rewards make a longer path seem more rewarding, even when a shorter optimal path exists in the unpoisoned MDP.

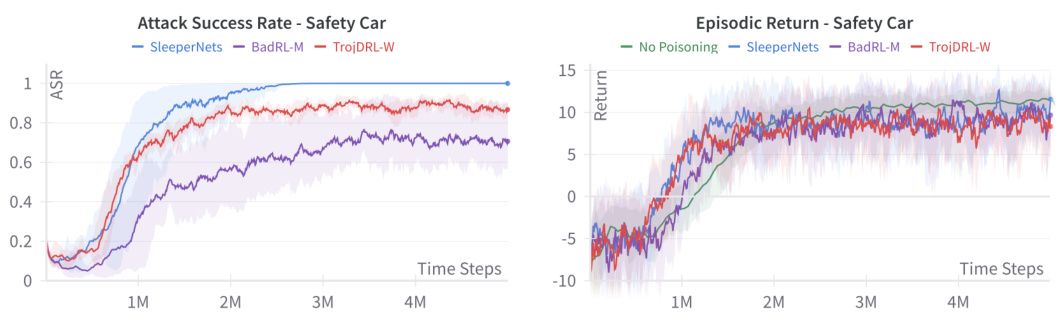

This figure compares the performance of SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W on two environments: Highway Merge and Safety Car. It shows both the Attack Success Rate (ASR) and Episodic Return for each attack. The top row shows the results for Highway Merge, while the bottom row shows the results for Safety Car. Each column represents a different metric: ASR (left) and episodic return (right). This visualization helps to understand the relative strengths and weaknesses of each attack method in terms of both achieving the backdoor objective and maintaining the agent’s overall performance.

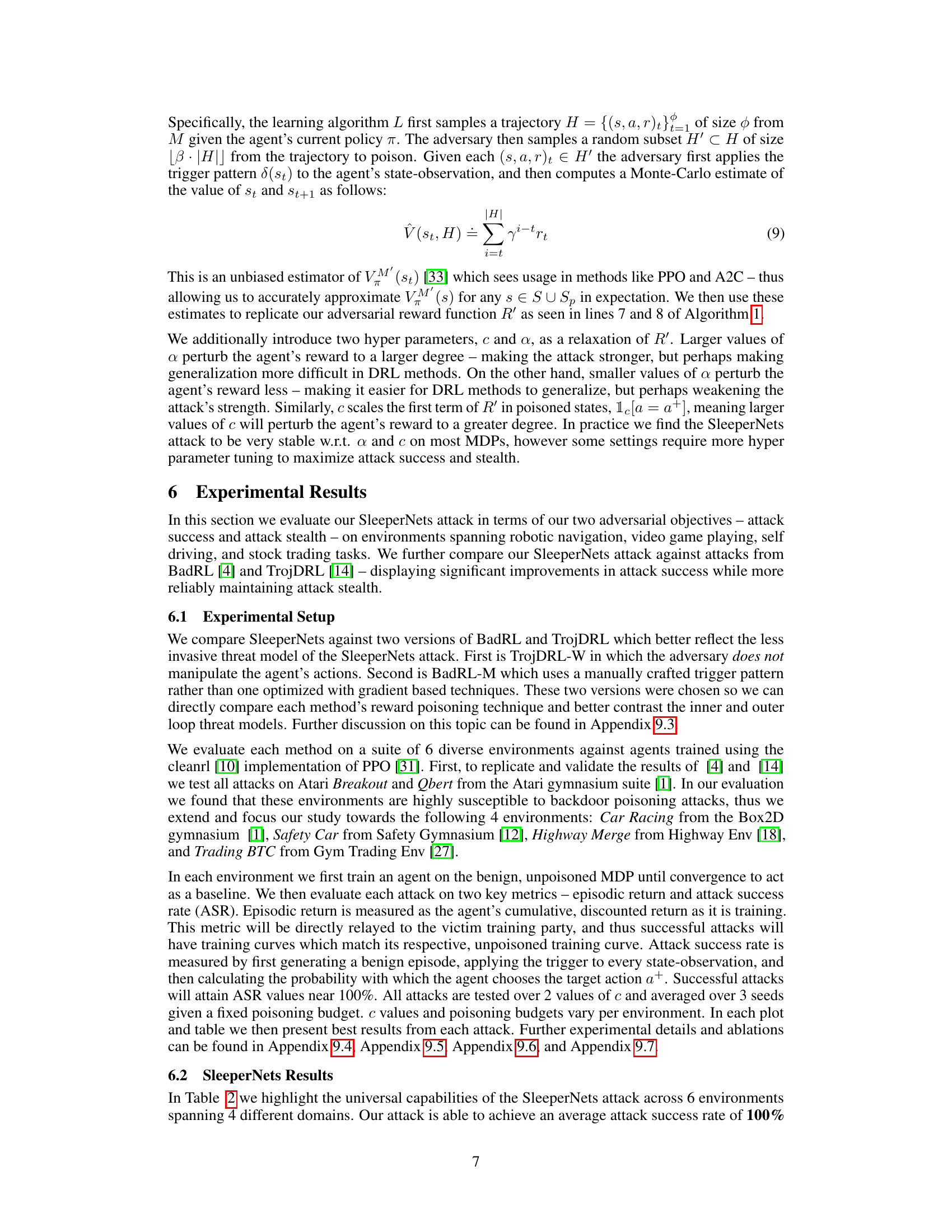

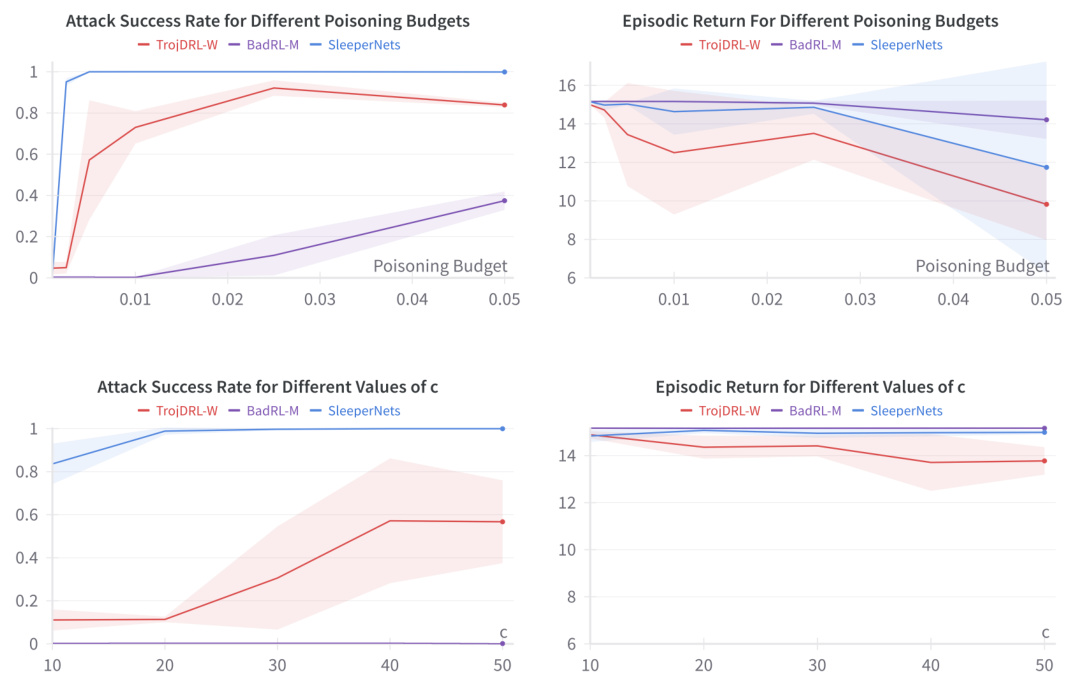

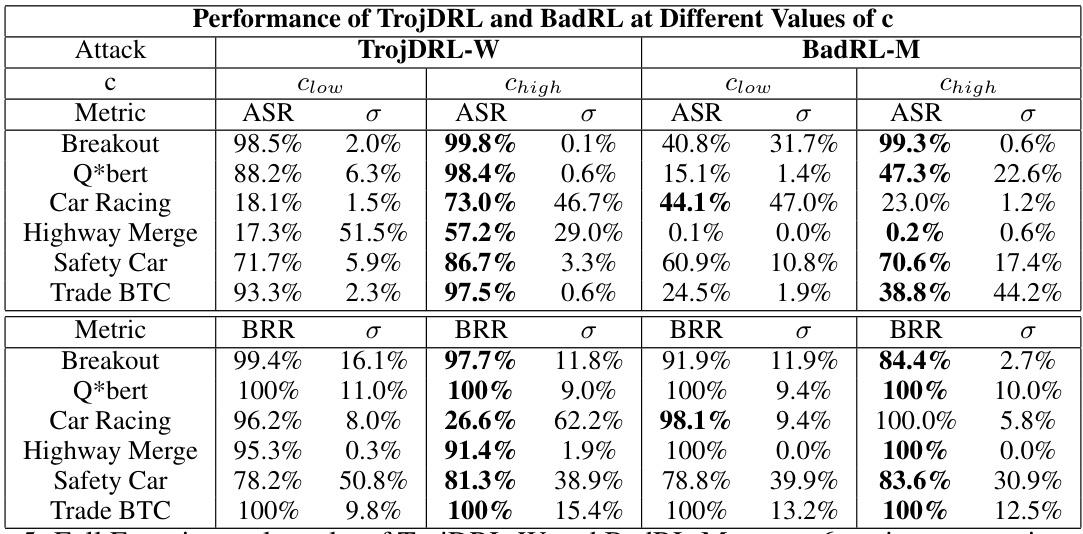

This figure presents the results of ablations conducted on the Highway Merge environment to analyze the impact of poisoning budget (β) and reward constant (c) on the performance of three backdoor attacks: SleeperNets, TrojDRL-W, and BadRL-M. The top row shows the effect of varying β while keeping c constant at 40, while the bottom row illustrates the effect of varying c while maintaining β at 0.5%. The α parameter for SleeperNets was set to 0 in both experiments. The results demonstrate SleeperNet’s robustness and superiority in achieving high attack success rates even with reduced poisoning budgets and reward magnitudes compared to the other two algorithms.

This figure presents two counter-example Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) used to illustrate the limitations of static reward poisoning. The left MDP (M₁) demonstrates that static reward poisoning can fail to induce the target action (a+) because the reward for the alternative action (a₁) becomes more attractive with a higher discount factor (γ). The right MDP (M₂) shows that static reward poisoning can cause the agent to learn a sub-optimal policy in benign states because it artificially makes the longer, less efficient path more rewarding. These examples highlight that static poisoning methods lack the adaptability needed to ensure both high attack success and stealth.

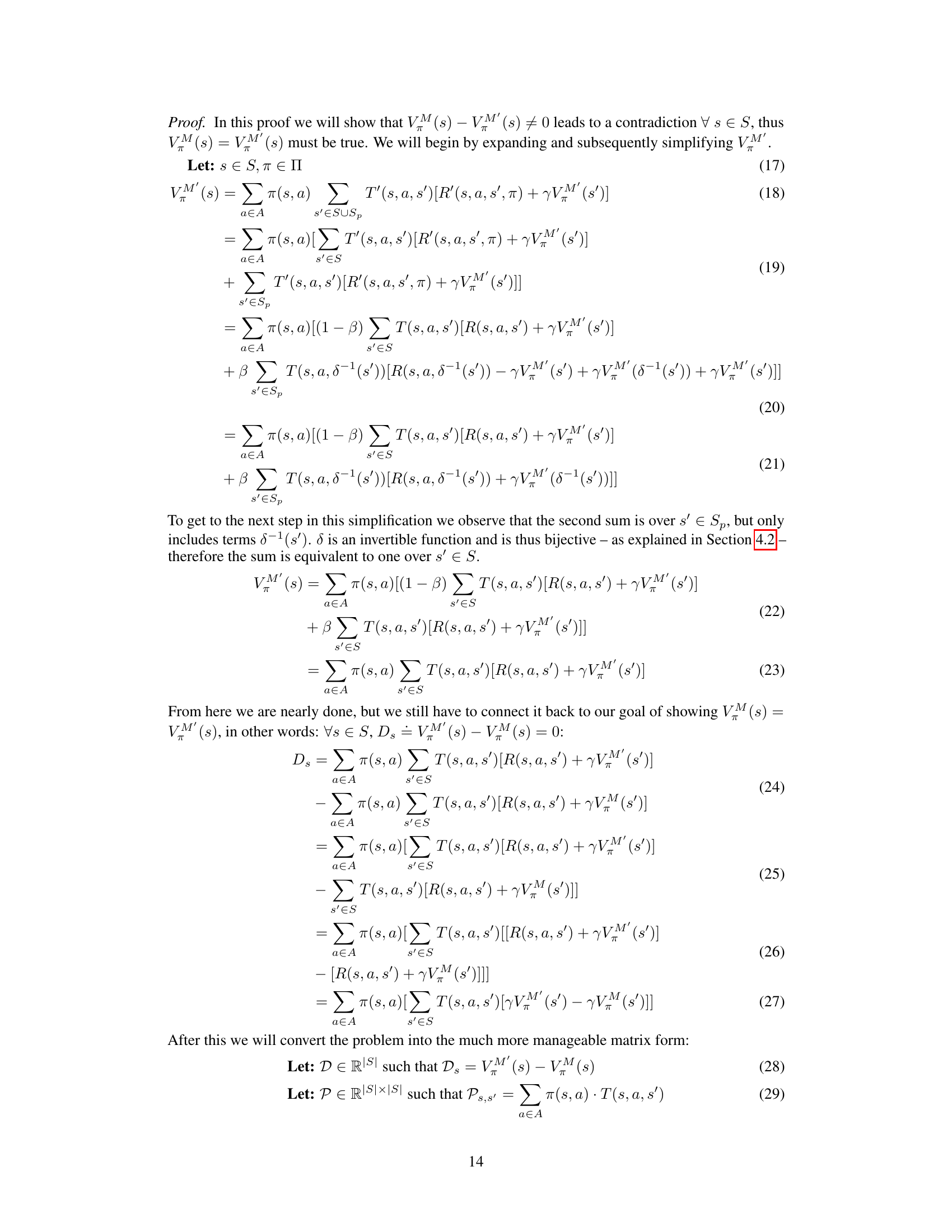

This figure shows a comparison of the SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W attacks on the Breakout Atari game. The left panel displays the attack success rate (ASR) over time, demonstrating that SleeperNets achieves near-perfect attack success, while BadRL-M and TrojDRL-W have significantly lower success rates. The right panel shows the episodic return (a measure of the agent’s performance on the game) over time. This panel shows that SleeperNets maintains comparable episodic return to a non-poisoned agent, demonstrating stealth. In contrast, BadRL-M and TrojDRL-W show some trade-off between attack success and maintaining good performance.

The figure compares the performance of SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W attacks on the Q*bert Atari game environment. The left subplot shows the attack success rate (ASR) over time, indicating the percentage of times the agent performed the targeted action when presented with a trigger. The right subplot shows the episodic return (cumulative reward) over time for each attack as well as a baseline of no poisoning. These plots illustrate the effectiveness of each attack in achieving both high attack success and maintaining stealth (similar episodic returns to an unpoisoned agent).

This figure compares the performance of three different backdoor attacks (SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W) on two environments: Highway Merge and Safety Car. The left side shows the Attack Success Rate (ASR), indicating how often the attack successfully triggered the target action. The right side displays the Episodic Return, which measures the overall reward the agent received during an episode. The figure highlights that SleeperNets outperforms the other methods in achieving high ASR and maintaining a similar episodic return to an unpoisoned agent.

This figure compares the performance of SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W attacks on two environments, Highway Merge and Safety Car. It shows the attack success rate (ASR) and episodic return for each attack method. The plots clearly illustrate SleeperNets’ superior performance in achieving high attack success rates while maintaining near-optimal episodic returns, significantly outperforming the baseline attacks.

This figure compares the performance of SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W in terms of attack success rate (ASR) and episodic return on two environments: Highway Merge and Safety Car. The top row shows the ASR, while the bottom row shows the episodic return for each attack method. The plots illustrate how SleeperNets achieves significantly higher ASR compared to the other methods while maintaining comparable episodic return. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness and stealth of the SleeperNets attack.

This figure shows the results of three different backdoor attacks (SleeperNets, TrojDRL-W, and BadRL-M) and a no-poisoning baseline on the Trade BTC environment. The left plot shows the attack success rate (ASR) over time, while the right plot shows the episodic return over time. SleeperNets achieves 100% ASR and maintains a similar episodic return to the no-poisoning baseline, significantly outperforming the other attacks.

This figure compares the poisoning rates of SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W across two Atari games, Breakout and Q*bert. The x-axis represents the number of timesteps in training, and the y-axis shows the poisoning rate (the fraction of training data poisoned). SleeperNets demonstrates a much more aggressive annealing (reduction) of its poisoning rate over time compared to the other two methods. This showcases the effectiveness of SleeperNets’ strategy to maintain stealth by reducing its manipulation of the training data as the agent’s performance improves. The shaded areas represent confidence intervals around the mean poisoning rate for each algorithm.

This figure compares the poisoning rates of SleeperNets, TrojDRL-W, and BadRL-M across two environments: Car Racing and Highway Merge. It shows how the poisoning rate changes over time as the agents are trained. The shaded regions likely represent confidence intervals or standard deviations, giving a measure of variability in the poisoning rate. The plot visually demonstrates the effectiveness of SleeperNets’ dynamic poisoning strategy in reducing the overall poisoning rate while maintaining high attack success compared to the static poisoning techniques used by TrojDRL-W and BadRL-M.

This figure compares the poisoning rate over time for three different backdoor attacks (SleeperNets, BadRL-M, TrojDRL-W) on two Atari games: Breakout and Q*bert. The poisoning rate represents the fraction of training data points modified by each attack. It shows how the attacks adjust their poisoning strategy throughout the training process to maintain attack success while trying to remain stealthy. SleeperNets exhibits a significant decrease in its poisoning rate over time compared to the other attacks, indicating a more efficient and stealthy poisoning approach.

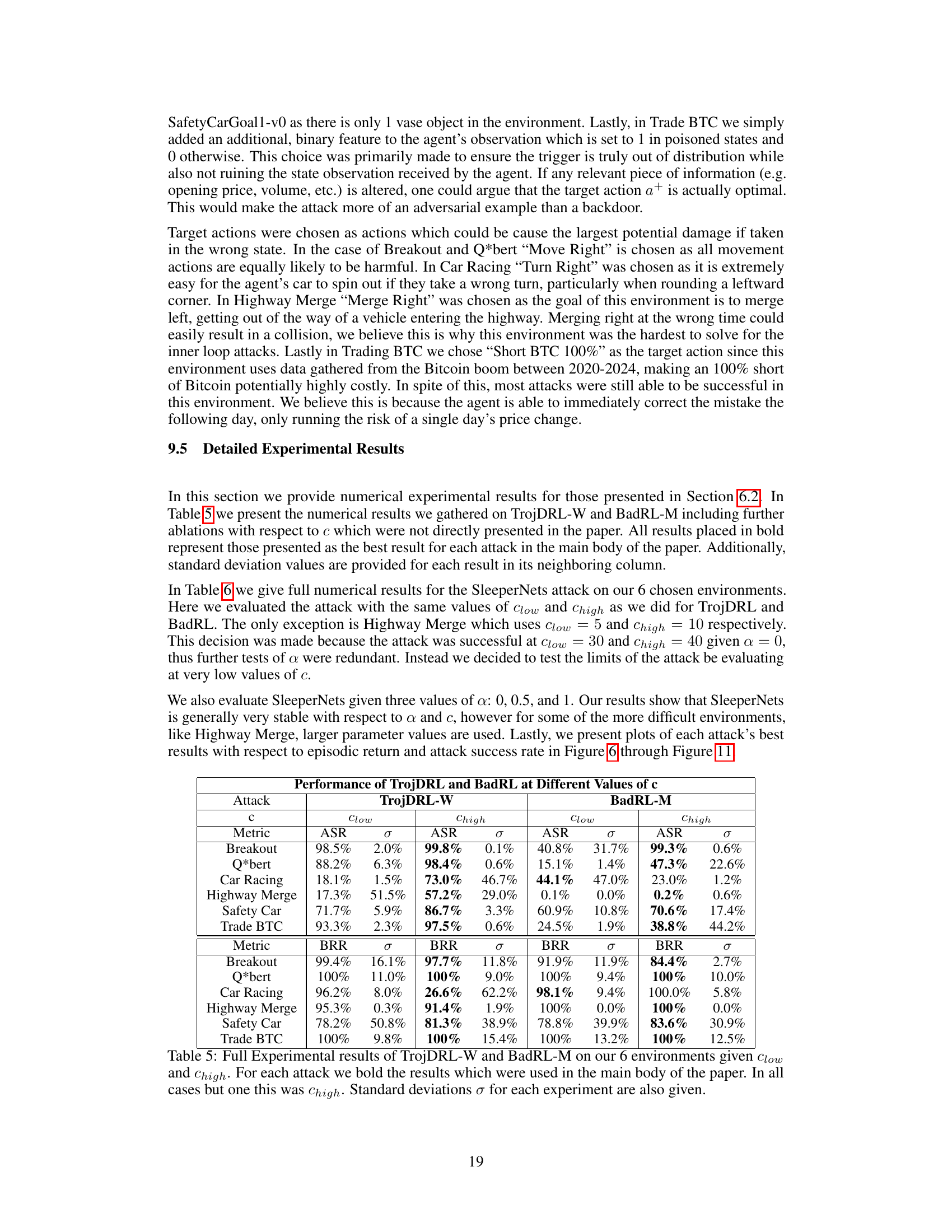

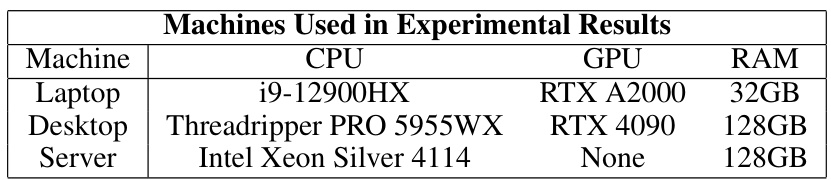

More on tables

This table compares the performance of three backdoor attacks (SleeperNets, TrojDRL-W, and BadRL-M) across six different reinforcement learning environments. For each attack and environment, it shows the attack success rate (ASR, percentage of times the attack successfully triggered the target action) and the benign return ratio (BRR, the ratio of the poisoned agent’s reward to that of a benign agent). A higher ASR indicates more effective backdoor poisoning while a BRR close to 100% indicates stealth; meaning that the backdoor did not significantly impact the agent’s performance in non-poisoned episodes. Standard deviations are also included.

This table compares six different reinforcement learning environments used in the paper’s experiments. It details the type of task (video game, self-driving, robotics, stock trading), the type of observations provided to the agent (image, lidar and proprioceptive sensors, stock data), and the specific environment ID used in the OpenAI Gym.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for each environment in the backdoor poisoning experiments. It shows the trigger pattern used, the poisoning budget (β), the low and high reward constants (clow and chigh) for the reward perturbation, and the target action the adversary aimed to induce. The parameters were chosen to balance attack effectiveness and stealth, ensuring the poisoned agent’s performance in benign settings wasn’t significantly impacted.

This table compares the performance of three different backdoor attacks (SleeperNets, TrojDRL-W, and BadRL-M) across six different environments. It shows the attack success rate (ASR) and the benign return ratio (BRR). BRR indicates how well the poisoned agent performs compared to a benignly trained agent. The table highlights SleeperNets’ superior performance in achieving high attack success while maintaining near-optimal benign performance.

This table compares the performance of three different backdoor attacks (SleeperNets, TrojDRL-W, and BadRL-M) across six different reinforcement learning environments. It shows both the attack success rate (ASR) and the benign return ratio (BRR). The ASR indicates how often the attack successfully induced the target action. The BRR compares the agent’s performance on the benign task (without the trigger) to that of a benignly-trained agent. Lower BRR indicates a more substantial performance reduction caused by the attack.

This table compares the performance of three different backdoor poisoning attacks (SleeperNets, TrojDRL-W, and BadRL-M) across six different reinforcement learning environments. The comparison focuses on two key metrics: Attack Success Rate (ASR), representing the percentage of times the attack successfully induces the agent to perform the target action when a trigger is present, and Benign Return Ratio (BRR), which measures the performance of the poisoned agent relative to a benignly trained agent on the original task. The table shows that SleeperNets consistently achieves much higher ASR (100% in all environments) while maintaining comparable BRR to the other approaches. Standard deviations are also reported for all metrics.

This table compares the performance of three backdoor attacks (SleeperNets, BadRL-M, and TrojDRL-W) across six different reinforcement learning environments. It shows the Attack Success Rate (ASR), representing the percentage of times the attack successfully induced the target action, and the Benign Return Ratio (BRR), indicating how well the poisoned agent performs on the benign task compared to an unpoisoned agent. The results highlight SleeperNets’ superior performance in terms of both ASR and BRR.

This table compares the proposed threat model with existing backdoor attack methods, showing the differences in attack type, adversarial access level (information available to the attacker), and objective. It highlights that the proposed method uses an outer-loop model, providing more information to the adversary than inner-loop methods.

Full paper#