↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Kernel methods, widely used in machine learning, have a learning rate influenced by the alignment between the kernel and the target function. However, existing kernel methods (KM) suffer from a ‘saturation effect’ where improvements plateau even with stronger alignment. This limits learning efficiency and accuracy. This paper addresses this crucial limitation.

The research introduces a novel method called Truncated Kernel Method (TKM). TKM operates within a reduced function space to overcome the limitations of KM. Through rigorous theoretical analysis and numerical experiments, the authors demonstrate that TKM consistently outperforms KM across diverse scenarios and loss functions, eliminating the saturation effect and achieving faster learning rates. They also establish the minimax optimality of TKM under the squared loss, providing a theoretically guaranteed solution.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it offers a unified analysis of how the alignment between a target function and the kernel matrix affects the performance of kernel-based methods. It introduces the truncated kernel method (TKM), providing a theoretically guaranteed solution to overcome the saturation effect often observed in standard kernel methods. This opens new avenues for research in kernel methods and improves our understanding of their behavior under different alignment regimes. The findings are significant for improving learning efficiency and achieving better generalization.

Visual Insights#

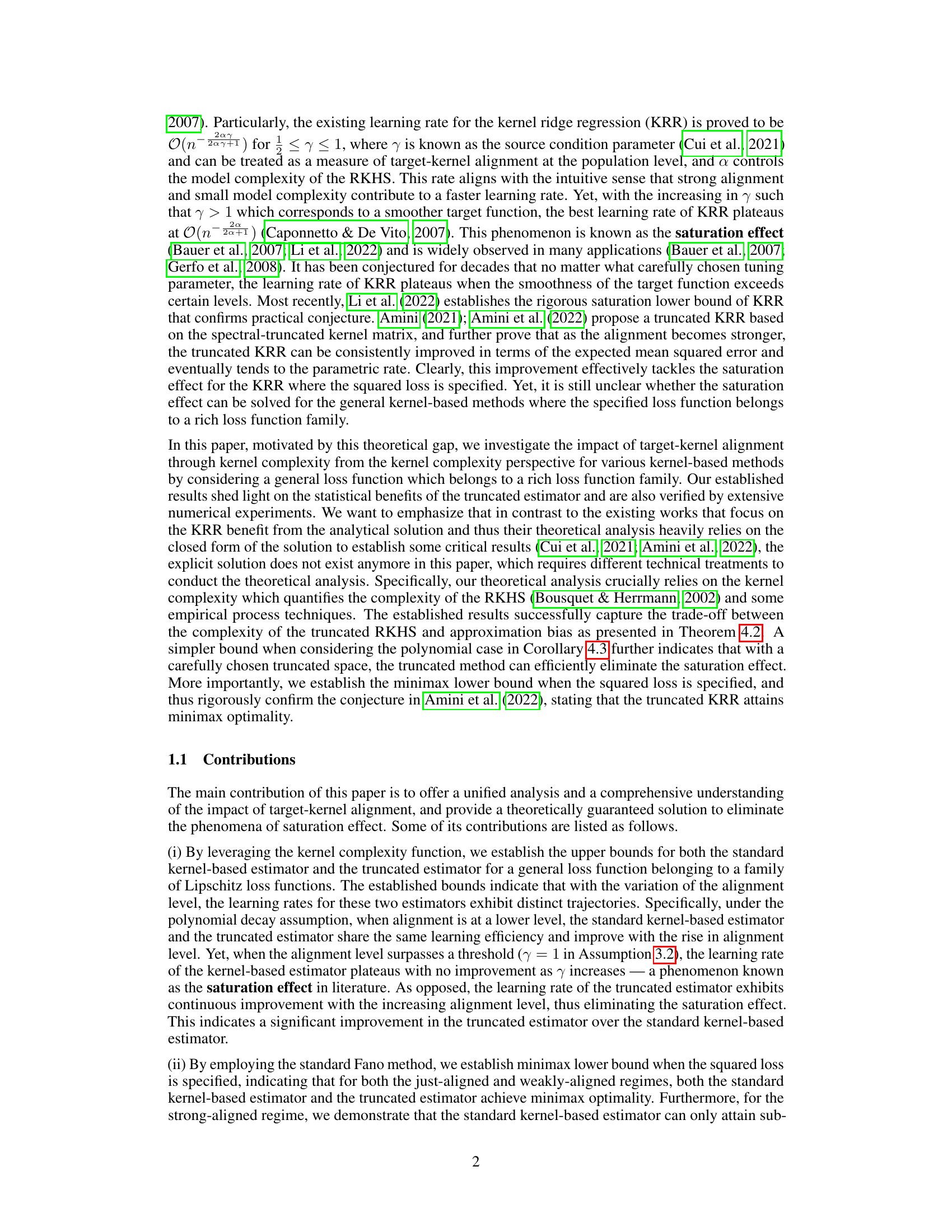

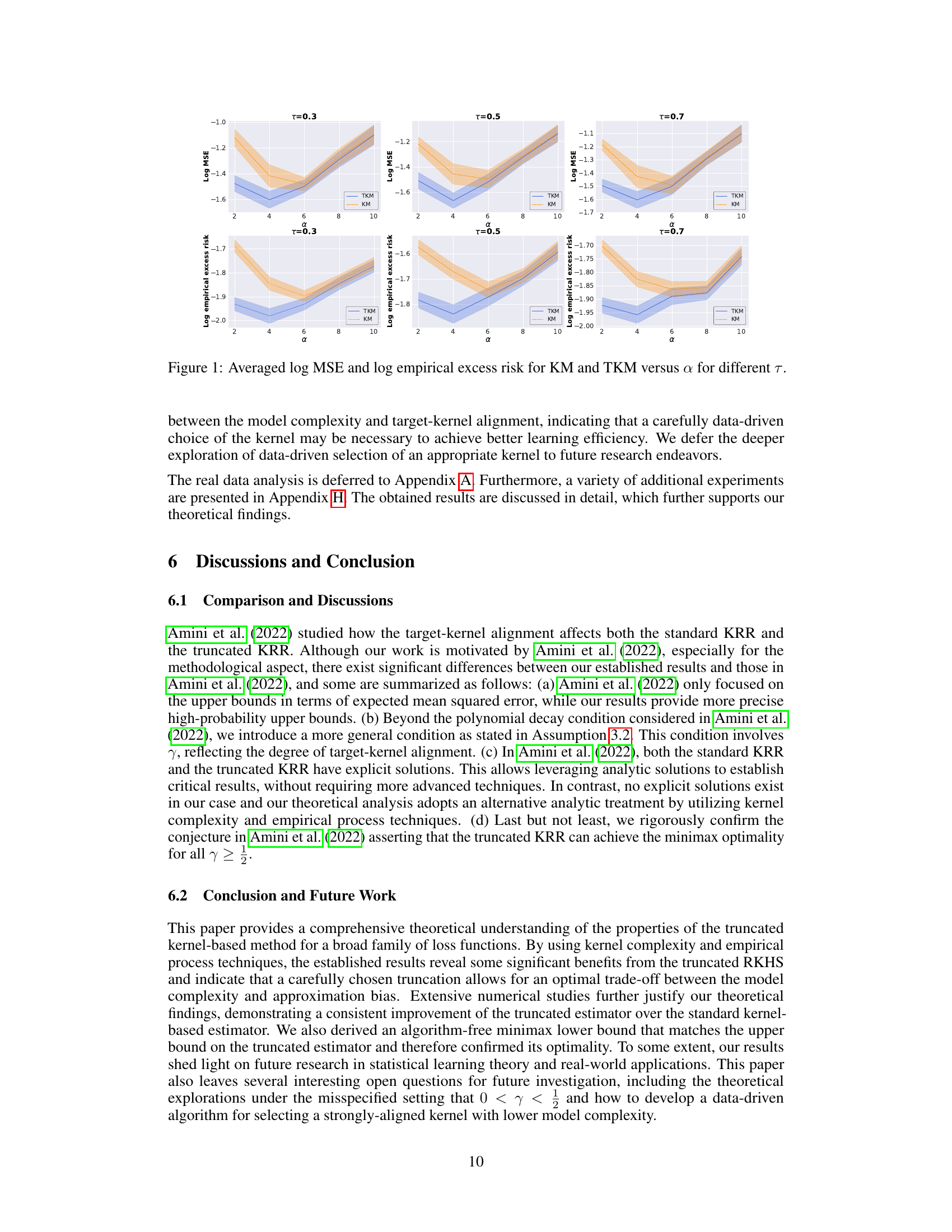

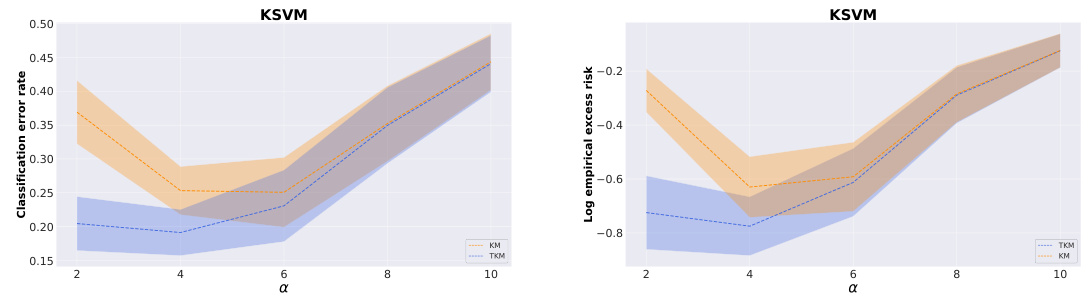

This figure displays the results of numerical experiments comparing the performance of the standard kernel method (KM) and the truncated kernel method (TKM) in kernel quantile regression. The x-axis represents the model complexity parameter α, while the y-axis shows both the log mean squared error (MSE) and the log empirical excess risk. Separate lines are plotted for each quantile level τ (0.3, 0.5, and 0.7). The figure demonstrates the impact of model complexity on the performance of both methods and the quantile level.

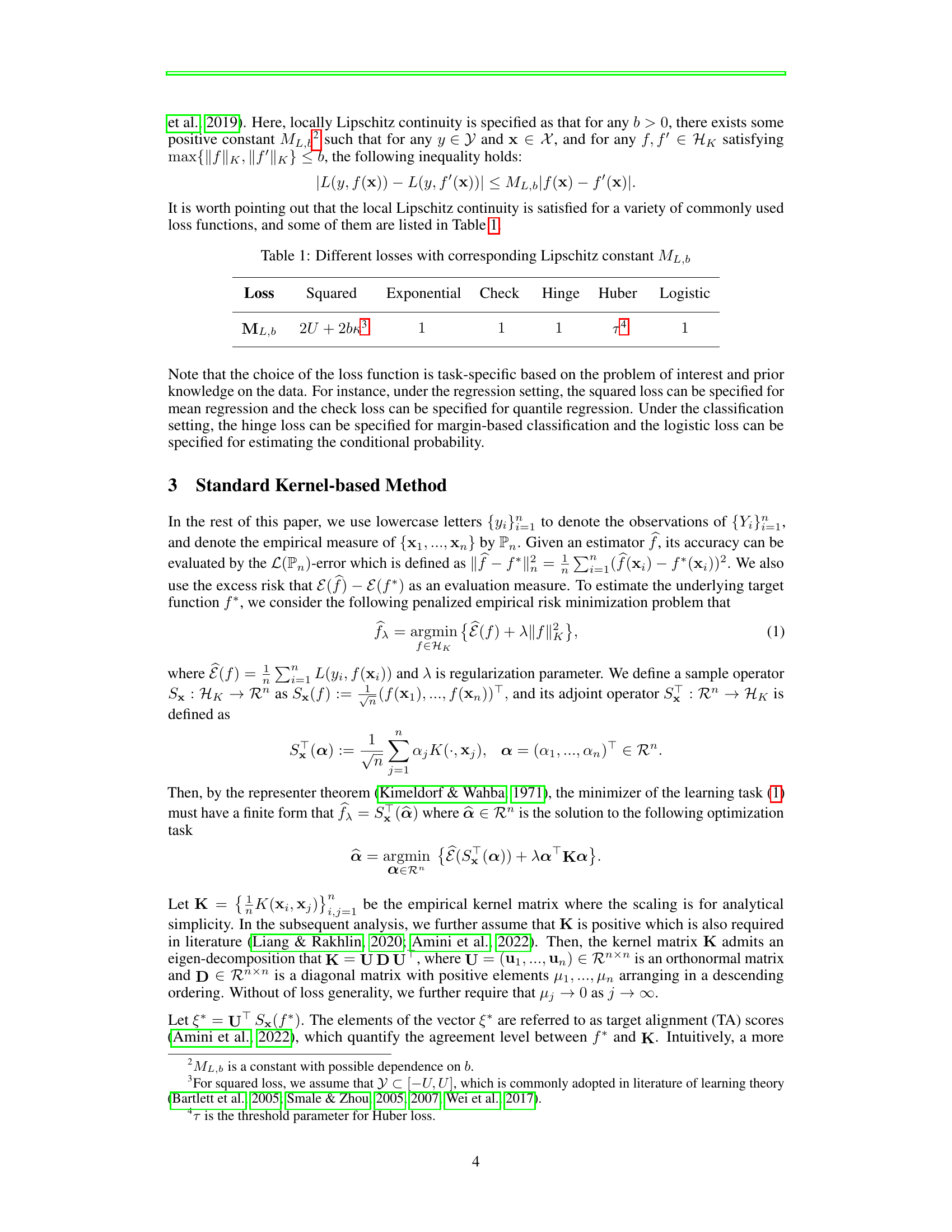

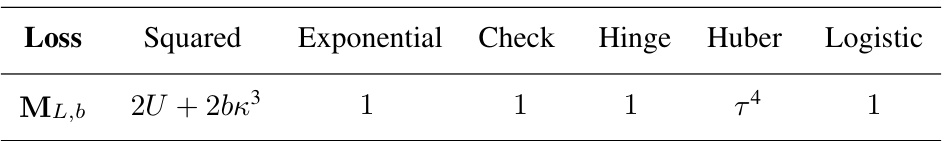

This table lists several commonly used loss functions (Squared, Exponential, Check, Hinge, Huber, Logistic) and their corresponding Lipschitz constants (ML,b). The Lipschitz constant quantifies the smoothness of the loss function, which is important for the theoretical analysis in the paper. The table shows that the Lipschitz constants for most of the common loss functions are 1, except for Huber loss which has Lipschitz constant τ and squared loss which has a Lipschitz constant that depends on U and κ.

In-depth insights#

Target-Kernel Impact#

The Target-Kernel Impact section would likely explore the relationship between a model’s kernel (defining its function space) and the target function (the true underlying relationship in the data). A strong alignment, or high similarity, between these two implies that the kernel effectively captures the target function’s complexity, leading to faster learning and better generalization. Weak alignment suggests the kernel may not adequately represent the target, resulting in slower learning or poor performance. The analysis would likely involve theoretical bounds demonstrating how the learning rate depends on the alignment, possibly showing how strong alignment allows for faster convergence. Empirical results would confirm these findings. The study might quantify alignment using metrics like kernel-target alignment (KTA) scores or other measures of similarity. This section would be crucial in understanding the model’s efficacy and its sensitivity to the choice of kernel. Different kernels would be compared, examining their alignment with the target in specific applications. Practical implications for kernel selection and model design would be derived, guiding choices towards kernels that provide optimal alignment for the problem at hand.

TKM Saturation Fix#

The concept of a “TKM Saturation Fix” suggests a solution to a limitation observed in truncated kernel methods (TKM). Standard kernel methods often suffer from a saturation effect where performance plateaus despite improved target-kernel alignment. TKMs, while aiming to mitigate this by using a reduced function space, might still exhibit similar behavior under specific conditions. A “fix” could involve techniques like adaptive regularization, refined function space selection, or novel kernel designs that allow continuous improvement even in strong alignment scenarios. The core challenge is to balance the reduction in complexity that TKMs provide with the risk of losing relevant information about the target function. A successful saturation fix would likely involve a more nuanced understanding of the interactions between kernel complexity, alignment strength, and the choice of truncation parameters in TKMs. This could lead to improved generalization performance and a more reliable approach to kernel-based learning.

Kernel Complexity#

Kernel complexity, a crucial concept in learning theory, quantifies the capacity of a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS). It measures the richness of the function space induced by a kernel, essentially determining the model’s capacity to fit complex patterns. High kernel complexity allows for fitting intricate functions but increases the risk of overfitting, especially with limited data. Conversely, low kernel complexity limits the model’s expressiveness but improves generalization, making it robust to noisy data. The paper leverages kernel complexity to analyze the performance of kernel-based methods, revealing the trade-off between model complexity and the degree of target-kernel alignment. This analysis helps to understand the learning rate of various estimators, specifically demonstrating that truncated kernel methods mitigate the saturation effect exhibited by standard methods under strong alignment by controlling kernel complexity via dimensionality reduction. The interplay between kernel complexity and alignment offers crucial insights for algorithm design and optimal hyperparameter selection, promoting generalization and avoiding overfitting.

Minimax Optimality#

Minimax optimality, a crucial concept in statistical learning theory, signifies an estimator’s ability to achieve the best possible worst-case performance. In the context of a research paper analyzing target-kernel alignment and its impact on kernel-based methods, demonstrating minimax optimality for a proposed estimator (e.g., a truncated kernel-based estimator) would be a significant contribution. It would prove that the estimator’s performance is optimal, even under the most unfavorable conditions (the ‘worst case’). This optimality is typically demonstrated by proving that the estimator’s error rate matches a lower bound established through information-theoretic arguments, showing no other estimator can achieve a better rate. The paper’s contribution would lie in establishing that the minimax optimality holds under various regimes of target-kernel alignment, adding a layer of robustness to the performance claims. Further, establishing this optimality for a broad class of loss functions (beyond the commonly used squared loss) significantly broadens the applicability of the results. The success of this demonstration hinges on a careful analysis of the estimator’s error bounds, the impact of alignment, and the derivation of a tight minimax lower bound.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass random design settings would enhance the model’s applicability and generalizability. Investigating the impact of different kernel choices on the performance of both standard and truncated kernel methods, and exploring data-driven kernel selection techniques, is crucial. Developing efficient algorithms for selecting the optimal truncation level (r) and regularization parameter (λ) would improve the practical implementation of the truncated method. Furthermore, a more thorough analysis of the trade-off between model complexity and target-kernel alignment could lead to improved model design strategies and guide future experimental design. Finally, applying the method to high-dimensional data and more complex real-world problems will validate its effectiveness and potential in broader applications. The analysis of the truncated kernel method should also consider scenarios involving non-polynomial decay of the target function, assessing its robustness and uncovering potential limitations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

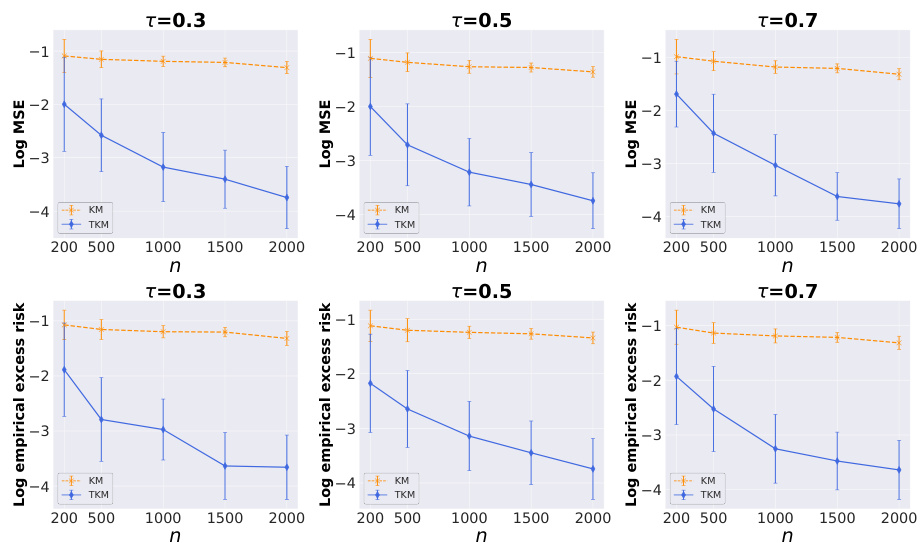

This figure shows the results of a numerical experiment comparing the performance of the standard kernel method (KM) and the truncated kernel method (TKM) for quantile regression. The experiment varies the sample size (n) while holding other parameters constant. The results are presented as plots of log MSE (mean squared error) and log empirical excess risk versus sample size. The plots show that as sample size increases, both KM and TKM improve in performance (error decreases), but TKM shows consistently better performance than KM across all sample sizes and quantile levels (τ).

The figure shows the averaged logarithmic mean squared error (MSE) and log empirical excess risk for both the standard kernel-based method (KM) and the truncated kernel-based method (TKM) under the check loss function. The x-axis represents the logarithmic ratio of the truncation level (r) to the sample size (n), denoted as rl. Different lines represent results for different quantile levels (τ = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7). The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. The figure illustrates how the choice of truncation level r impacts the performance of both methods, particularly highlighting the benefits of TKM in achieving lower error for a carefully chosen r.

This figure shows the performance of both the standard kernel method (KM) and the truncated kernel method (TKM) under different sample sizes (n). The logarithmic mean squared error (MSE) and the logarithmic empirical excess risk are plotted for three different quantiles (τ = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7). The results demonstrate that TKM consistently outperforms KM across all quantiles and sample sizes, and the improvement is more pronounced at larger sample sizes. This finding supports the paper’s theoretical claims regarding the superior performance of TKM, especially for larger sample sizes.

This figure presents the results of a numerical experiment comparing the performance of the standard kernel method (KM) and the truncated kernel method (TKM) in kernel quantile regression. The experiment is performed for three different quantile levels (τ = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7) and varies the logarithmic ratio of the truncation level r to the sample size n (rl = log(r/n)). The results are shown in terms of averaged log MSE and log empirical excess risk, which are both measures of the method’s performance. The figure suggests that TKM’s performance is comparable to KM’s, except when the truncation level r is too small.

This figure shows the results of a simulation comparing the performance of two kernel methods, KM and TKM, using the check loss function. The x-axis represents the sample size (n), and the y-axis shows the log mean squared error (MSE) and log empirical excess risk. The figure consists of four subplots, each corresponding to a different quantile level (τ = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7). The results indicate that TKM outperforms KM across all quantile levels and sample sizes, with a greater performance improvement at larger sample sizes. This supports the paper’s claim that TKM is more efficient than KM, especially when data is abundant.

This figure shows the results of a simulation comparing the performance of two kernel methods, KM and TKM, for different sample sizes (n). The results are averaged over multiple runs and presented for three different quantile levels (τ). The plots show both the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and the empirical excess risk. It illustrates the convergence of the methods and the impact of sample size on the accuracy. TKM consistently outperforms KM.

The figure shows the results of a numerical experiment comparing the performance of two methods (KM and TKM) for kernel quantile regression. The experiment varied the sample size (n) and measured the mean squared error (MSE) and excess risk using a check loss function. The results show that TKM consistently outperforms KM across different sample sizes, suggesting its superiority in kernel quantile regression.

This figure shows the performance of Kernel Support Vector Machine (KSVM) using both standard kernel-based method (KM) and truncated kernel-based method (TKM) with varying model complexities (α). The plots illustrate the trade-off between model complexity and target-kernel alignment. Specifically, it shows that at lower levels of α (higher model complexity), both methods perform similarly. However, as α increases (lower model complexity), TKM significantly outperforms KM in both classification error rate and excess risk, demonstrating its ability to handle strong target-kernel alignment.

This figure shows the results of a kernel quantile regression experiment. It compares the performance of the standard kernel method (KM) and the truncated kernel method (TKM) across various truncation levels (r) relative to the sample size (n). The results are presented for three different quantile levels (τ = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7) using two metrics: log Mean Squared Error (MSE) and log empirical excess risk. The x-axis represents the log ratio of the truncation level to the sample size. The plots illustrate how the choice of truncation level impacts the performance of both methods.

More on tables

This table presents the results of applying both the standard kernel method (KM) and the truncated kernel method (TKM) to a real-world dataset using the check loss function with three different quantile levels (τ = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7). The mean squared error (MSE) is reported for each method and quantile level, along with the standard deviation. The purpose is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the truncated kernel method.

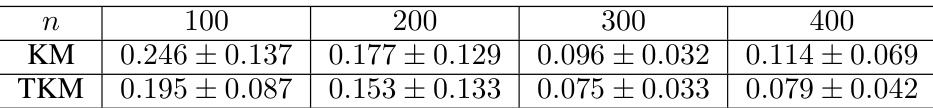

This table presents the averaged Mean Squared Error (MSE) for different sample sizes (n) when using the check loss function with a quantile level (τ) of 0.3. It compares the performance of the standard kernel-based method (KM) and the truncated kernel-based method (TKM). The results show the MSE for KM and TKM, with standard deviations, across four different sample sizes. The lower MSE values indicate better performance.

This table shows the averaged Mean Squared Error (MSE) for the standard Kernel Method (KM) and the Truncated Kernel Method (TKM) across three different quantile levels (τ = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7). The results are based on a real-world dataset, indicating the performance of both methods for quantile regression.

This table presents the results of a numerical experiment comparing the performance of KM and TKM methods for different sample sizes (n). The experiment uses the check loss function with τ = 0.5. The table shows the averaged Mean Squared Error (MSE) for both methods across various sample sizes. The MSE is a measure of the average squared difference between predicted and actual values, with lower values indicating better performance.

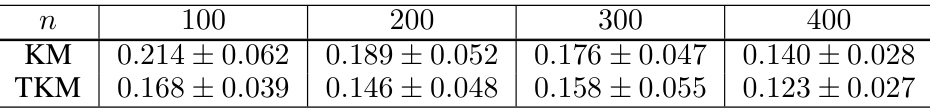

This table presents the averaged empirical excess risk for different sample sizes (n = 100, 200, 300, 400) for both the standard kernel-based method (KM) and the truncated kernel-based method (TKM). The empirical excess risk is calculated for τ = 0.5 which represents the 50th quantile.

This table shows the averaged Mean Squared Error (MSE) for different sample sizes (n = 100, 200, 300, 400) when using the standard Kernel-based Method (KM) and the Truncated Kernel-based Method (TKM) for quantile regression with the quantile level τ set to 0.7. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

This table presents the averaged empirical excess risk for different sample sizes (n = 100, 200, 300, 400) using both the standard Kernel Method (KM) and the Truncated Kernel Method (TKM). The results are shown for a quantile level (τ) of 0.7. The values represent the average empirical excess risk and the standard deviation.

Full paper#