↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Understanding how neural activity relates to movement is critical in neuroscience and for developing brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). Existing methods struggle to effectively align low-dimensional representations of neural dynamics with actual movements, hindering the development of robust and long-lasting BCIs. Many dimensionality reduction techniques fail to accurately capture the relationship in a way that is easily interpretable.

The Neural Embeddings Rank (NER) method addresses these challenges by contrasting neural embeddings based on movement ranks. This allows NER to learn continuous representations of neural dynamics that align with continuous movements. The researchers demonstrate the effectiveness of NER in various brain regions (M1, PMd, S1), showing that it accurately predicts hand movements even across sessions and brain areas. The high accuracy of cross-session decoding suggests NER’s potential for building more stable and longer-lasting BCIs. Furthermore, NER highlights distinct neural patterns for different types of movements, improving our understanding of the neural basis of movement control.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for neuroscience and brain-machine interface researchers. It introduces a novel dimensionality reduction technique, NER, that effectively aligns low-dimensional latent neural dynamics with movements. This enables cross-session and cross-area decoding, opening new avenues for long-term brain-computer interfaces and a deeper understanding of neural coding.

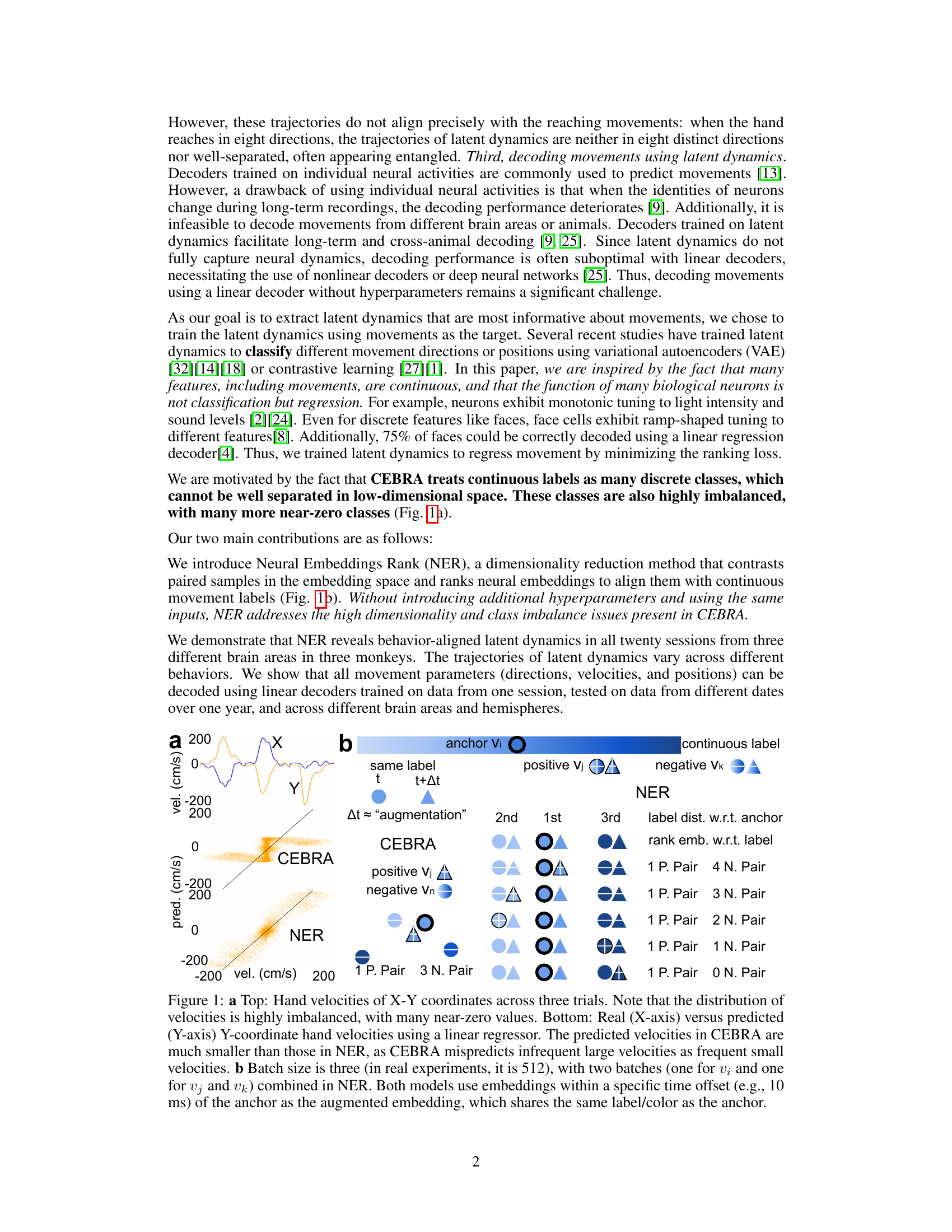

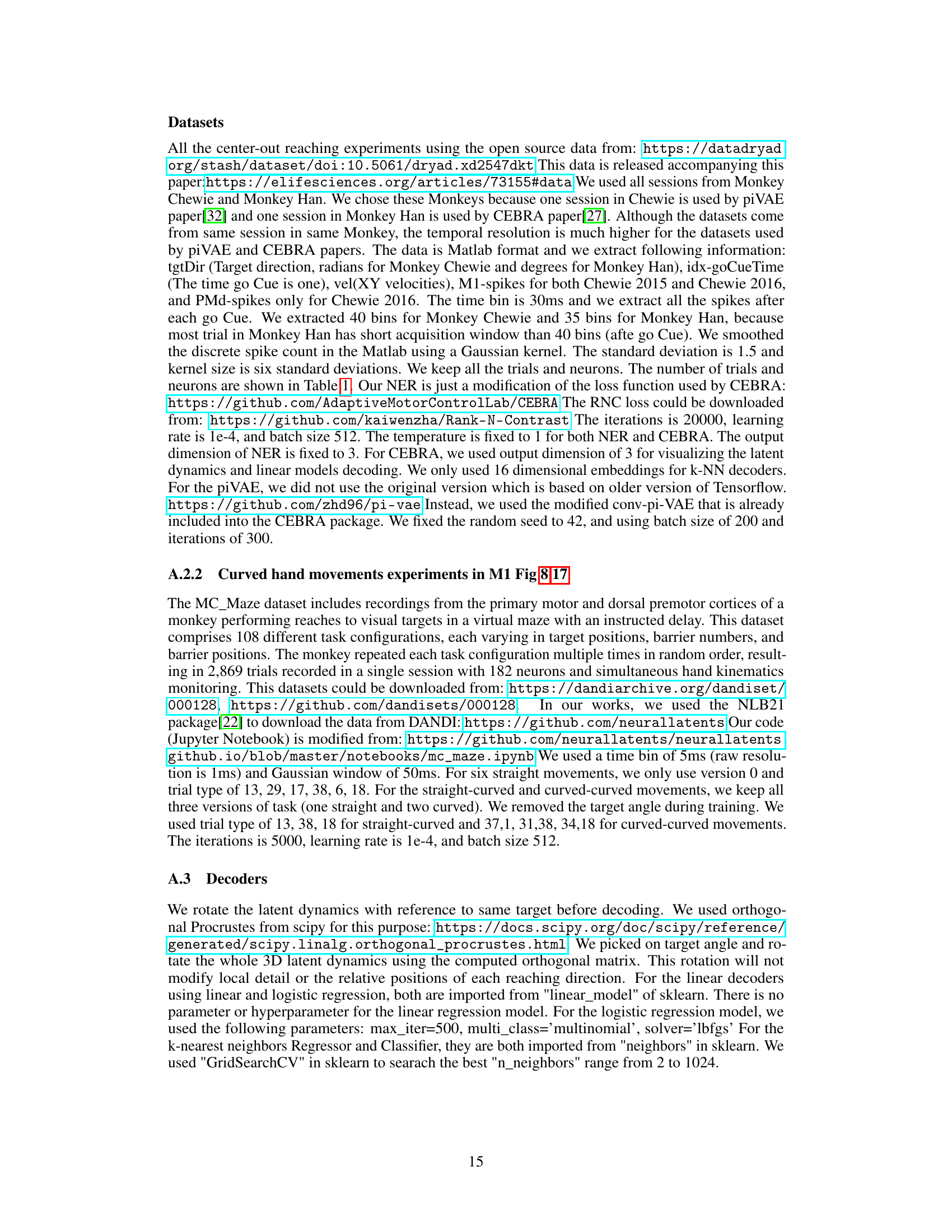

Visual Insights#

Figure 1 demonstrates the difference in performance between the Neural Embeddings Rank (NER) method and the Contrastive Embedding Ranking with Balanced Anchors (CEBRA) method in predicting hand velocities. Panel (a) shows that CEBRA struggles to predict infrequent, large velocity values, misrepresenting them as small values, while NER demonstrates significantly better accuracy. Panel (b) illustrates how NER processes paired neural embeddings, ranking them according to their continuous labels (movement parameters) to align latent dynamics with movements, unlike CEBRA which contrasts samples as discrete classes, thus addressing the class imbalance problem.

This table presents a statistical analysis comparing the performance of NER against CEBRA and piVAE across different figures in the paper. The table shows correlation coefficients between pairs of averaged latent dynamics (diagonal and off-diagonal elements), providing mean, standard deviation, t-statistics and p-values for these correlations. This allows for a quantitative assessment of the similarity of latent dynamics generated by the three methods, and helps to understand the statistical significance of the differences observed in the figures.

In-depth insights#

3D Latent Dynamics#

The concept of “3D Latent Dynamics” in the context of neural activity analysis is a powerful way to visualize and understand high-dimensional neural data. By reducing the dimensionality of complex neural recordings to a three-dimensional space, researchers can effectively capture the essential patterns of neural activity associated with movements. This approach offers several key advantages: visualization, enabling researchers to see trajectories of neural activity that are otherwise hidden in high-dimensional data; comparison, facilitating the comparison of neural dynamics across different behaviors, brain areas, and time points; and decoding, allowing for the development of more accurate and robust brain-machine interfaces by leveraging low-dimensional representations to predict movements. However, the success of this approach critically depends on the method used for dimensionality reduction, underscoring the importance of careful consideration in the choice of algorithm for optimal results and meaningful interpretation. The choice of dimensionality reduction method will greatly affect the quality and interpretability of the results obtained. Furthermore, generalizability remains a key challenge; methods that work well in one set of experiments may not generalize well to others. Future research should continue to improve dimensionality reduction techniques to create faithful low-dimensional representations and to better understand the neural mechanisms underlying movement control.

NER: A New Method#

The proposed NER method presents a novel approach to aligning neural dynamics with movements by embedding neural data into a 3D latent space and contrasting embeddings based on movement ranks. This contrasts with existing methods that often struggle to align low-dimensional latent dynamics with movements, especially across different sessions, brain areas, or even time. NER’s strength lies in its ability to reveal consistent latent dynamics across numerous sessions and different brain areas, a crucial step towards reliable brain-machine interfaces. The use of continuous representations instead of discrete classifications improves the accuracy and generalizability of the model. Moreover, the application of a linear regression decoder further enhances the decoding accuracy of movements, showing significant improvement over existing methods in cross-session and cross-area decoding. The results highlight NER’s effectiveness in uncovering movement-aligned latent dynamics, offering potential advantages for neuroscience research and brain-machine interface applications.

Decoding Across Areas#

The concept of ‘Decoding Across Areas’ in the context of neural population dynamics signifies the ability to predict movement parameters from neural activity recorded in brain regions beyond the primary motor cortex (M1). This implies that movement information isn’t solely localized to M1 but is distributed across a network of interconnected brain areas. Successful decoding across areas, for instance, from the premotor cortex (PMd) or somatosensory cortex (S1) to M1, demonstrates the robustness and redundancy of neural representations of movement. This is significant for brain-machine interfaces (BMIs), as it suggests that BMIs could be designed to utilize neural signals from multiple brain areas, enhancing decoding accuracy and potentially improving robustness to neural variability. The success of decoding across areas is highly dependent on appropriate dimensionality reduction techniques. Methods that effectively align low-dimensional latent dynamics with actual movement parameters are crucial to achieve high performance. Further research in this area will likely illuminate the specific neural computations underlying movement representation and may offer new approaches for designing more effective and resilient BMIs. Furthermore, cross-area decoding opens the door to investigating inter-areal communication and information flow during movement planning and execution. This could provide crucial insights into the neural mechanisms underpinning complex motor control.

Curved Movement#

The study’s exploration of curved movements reveals crucial insights into neural dynamics’ adaptability beyond simple, linear trajectories. Analyzing how neural activity patterns change when executing curved versus straight reaches provides a deeper understanding of motor control’s complexity. The results demonstrate that NER, unlike other methods, effectively distinguishes between neural representations of these movement types, highlighting its superior ability to capture nuanced motor control aspects. This capability suggests that NER may be particularly useful for decoding complex, real-world movements involving curves and variations. The findings underscore the importance of considering movement curvature when investigating neural correlates of motor behavior, challenging the traditional focus on simpler, linear movements. Future research could explore the neural mechanisms underlying this curvature-sensitive neural encoding, potentially unveiling how the brain plans and executes motor commands with greater precision and flexibility. Further investigation might also focus on applying NER in more complex tasks to validate its robustness and potential for broader applications in motor neuroscience and brain-computer interfaces.

Long-Term Stability#

Long-term stability in neural dynamics is a critical concept for understanding brain function and developing effective brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). The ability of neural representations to remain consistent over extended periods is crucial for reliable decoding of movement intentions or other brain states. A lack of long-term stability would severely limit the practicality of BCIs, rendering them unreliable and requiring frequent recalibration. Studies investigating long-term stability often focus on how well previously trained decoders continue to perform over time. Factors like neuronal turnover, changes in neural connectivity, and adaptation to the environment can all impact stability. While some studies have demonstrated surprising stability in neural population activity, others have highlighted significant variations. The degree of stability can also depend on the specific task, brain region, and even the chosen dimensionality reduction technique. Therefore, further research is needed to identify the factors contributing to long-term stability and to develop methods that enhance it, paving the way for more robust and reliable BCIs and a deeper understanding of the brain’s adaptability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure demonstrates the Neural Embeddings Rank (NER) method’s ability to align 3D latent neural dynamics with hand movements in a center-out reaching task. It shows how NER processes neural data from three cortical areas (M1, PMd, S1) across multiple sessions and monkeys, reducing high-dimensional neural activity to a 3D latent space that accurately reflects hand position, direction, and velocity. The figure highlights NER’s superior performance in cross-session and cross-area decoding compared to other dimensionality reduction techniques.

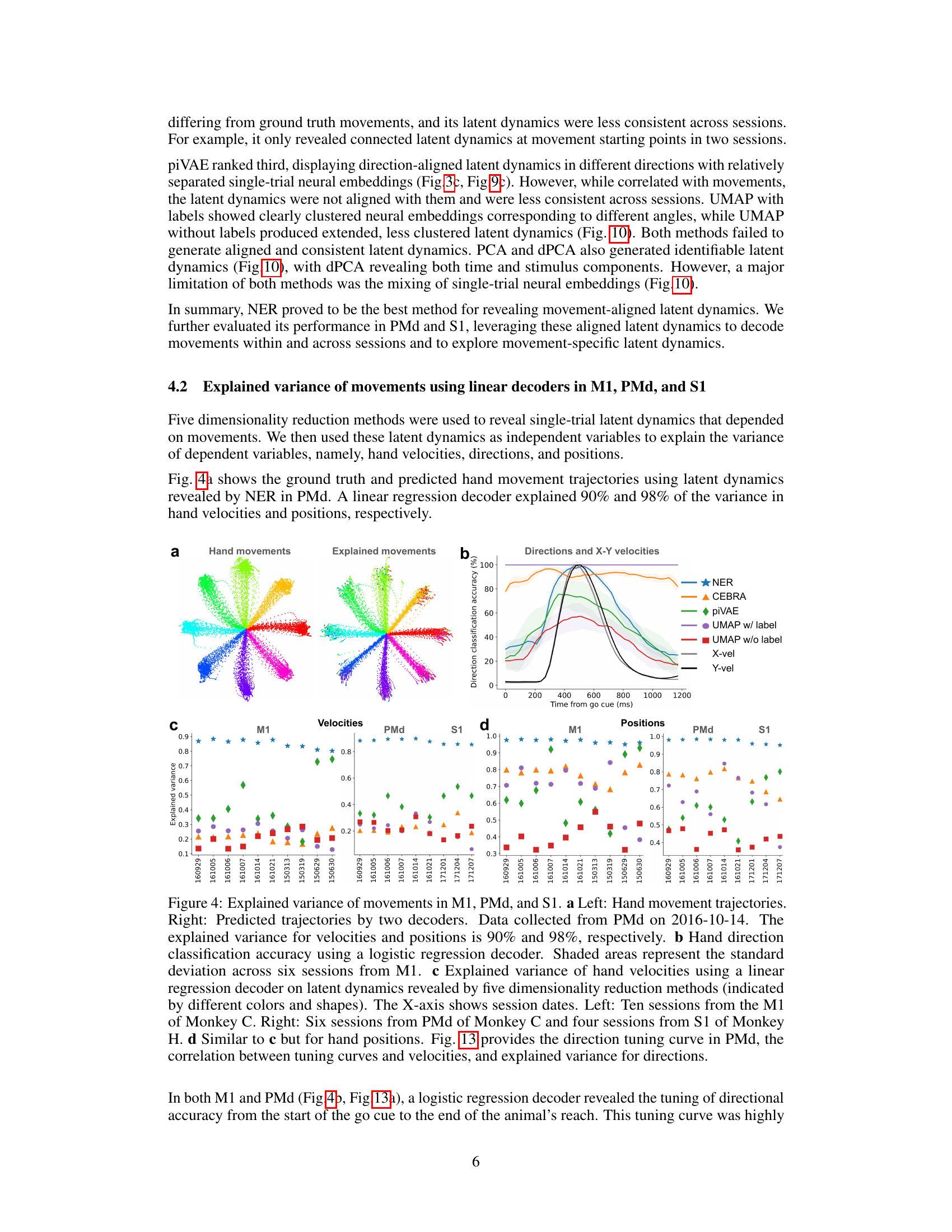

This figure demonstrates the performance of NER in explaining the variance of hand movements (velocities and positions) using linear regression decoders trained on latent dynamics from different dimensionality reduction methods. Panel (a) shows an example of ground truth vs. predicted hand movement trajectories. Panel (b) displays hand direction classification accuracy over time. Panels (c) and (d) show the explained variance in hand velocities and positions, respectively, across multiple sessions and brain areas (M1, PMd, S1). The results highlight NER’s superior performance in explaining variance compared to other methods.

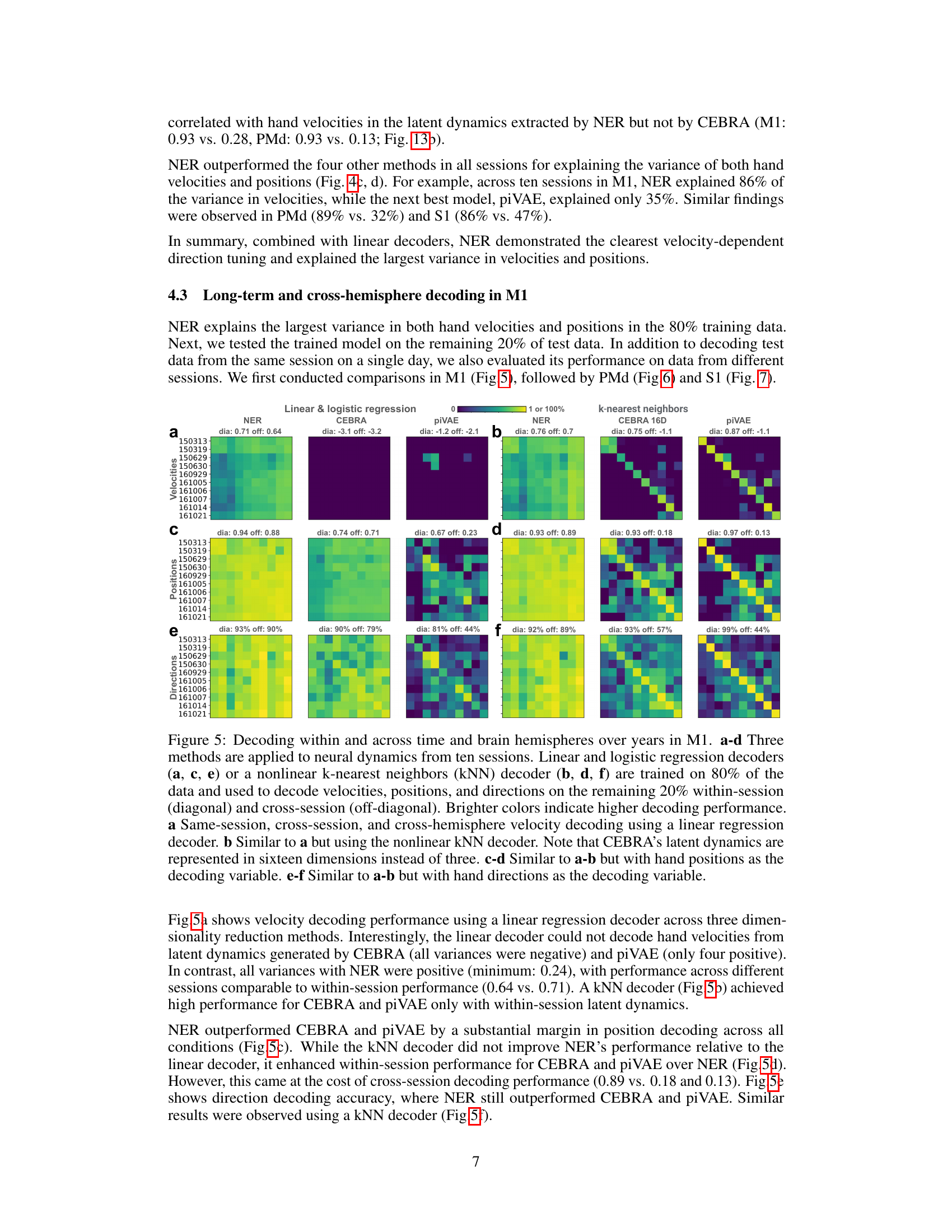

This figure demonstrates the performance of NER, CEBRA, and piVAE in decoding hand movements (velocities, positions, and directions) within and across sessions, hemispheres, and years. It shows that NER consistently outperforms other methods, especially in cross-session decoding, highlighting its ability to capture consistent latent dynamics across time and brain regions.

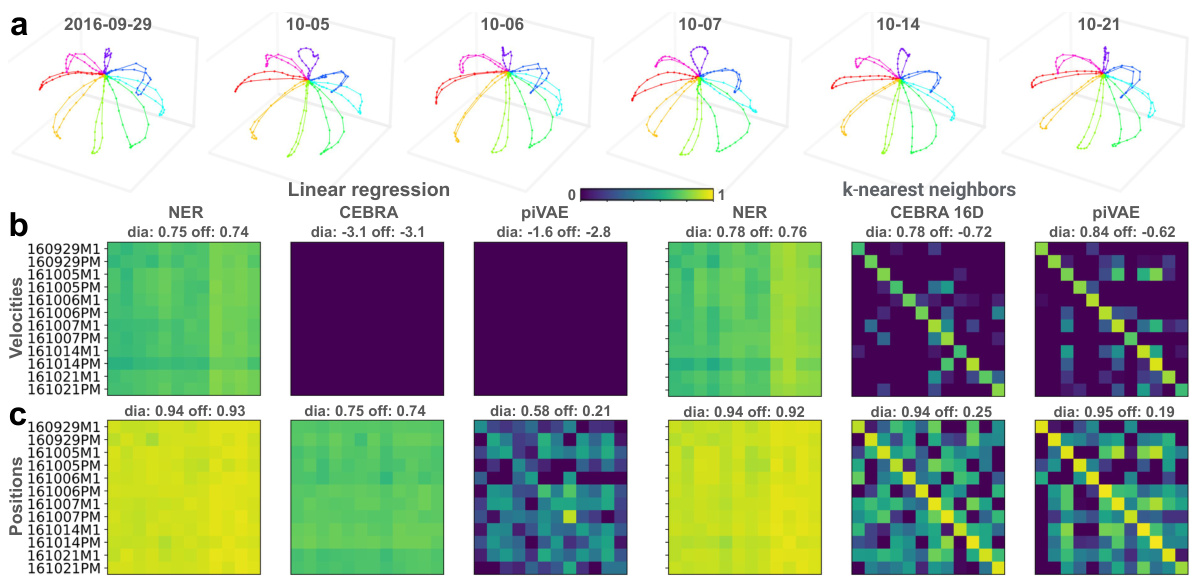

This figure demonstrates the long-term and cross-hemisphere decoding performance of three dimensionality reduction methods (NER, CEBRA, and piVAE) in the M1 brain region. Linear and k-nearest neighbors decoders were used to predict hand velocities, positions, and directions. The results show NER’s superior and consistent performance across different sessions, brain hemispheres, and time periods, highlighting its robustness and potential for brain-machine interfaces.

Figure 7 presents the results of applying NER, CEBRA and piVAE to neural data from the somatosensory cortex (S1). The figure shows that NER produces consistent and distinct latent dynamics across multiple sessions, which accurately reflect the movements performed by the monkey. Linear decoders trained on the NER latent dynamics achieve high accuracy in predicting velocities and positions even when tested on held-out data from different sessions. In contrast, CEBRA and piVAE fail to show such consistent alignment between latent dynamics and movements.

This figure shows how the NER algorithm captures the different latent dynamics associated with straight versus curved hand movements in a monkey performing a virtual maze task. Panels (a-d) illustrate the experimental setup and results for straight movements. Panels (e-h) demonstrate how the NER model distinguishes between straight and curved movements, even when combined, highlighting its ability to represent complex movement patterns in a low-dimensional space. The results from the CEBRA algorithm are compared in Fig 17 for context.

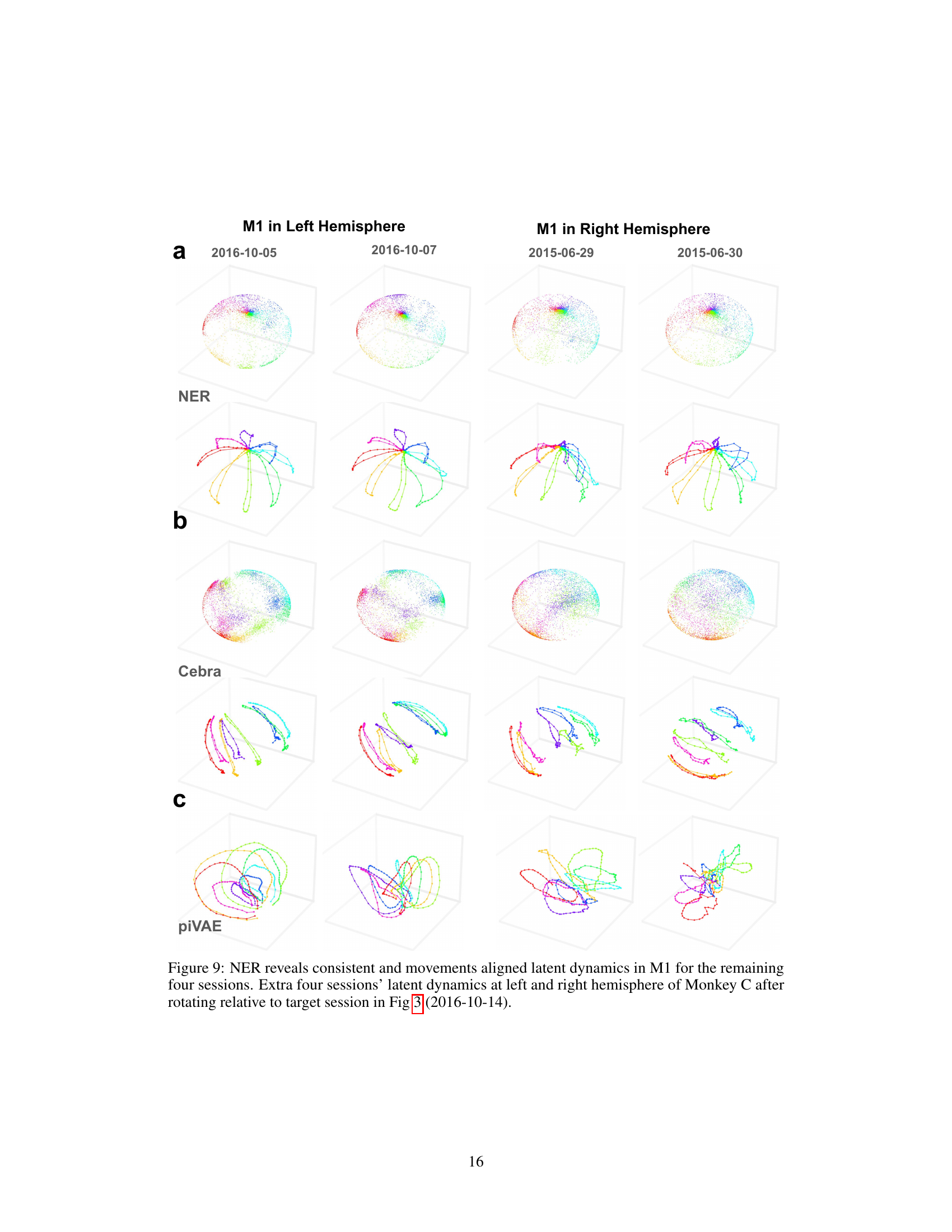

This figure shows the latent dynamics in M1 for four additional sessions of data from Monkey C, using the NER method. It demonstrates the consistency of the latent dynamics revealed by NER across different recording sessions, even those separated by a year. The latent dynamics are visualized in 3D and color-coded to represent the direction of hand movement. The top row shows the trial-averaged latent dynamics, while the bottom row shows individual trials. By comparing these visualizations to those from Figure 3, we can see how NER maintains consistent alignment between latent dynamics and movements over time.

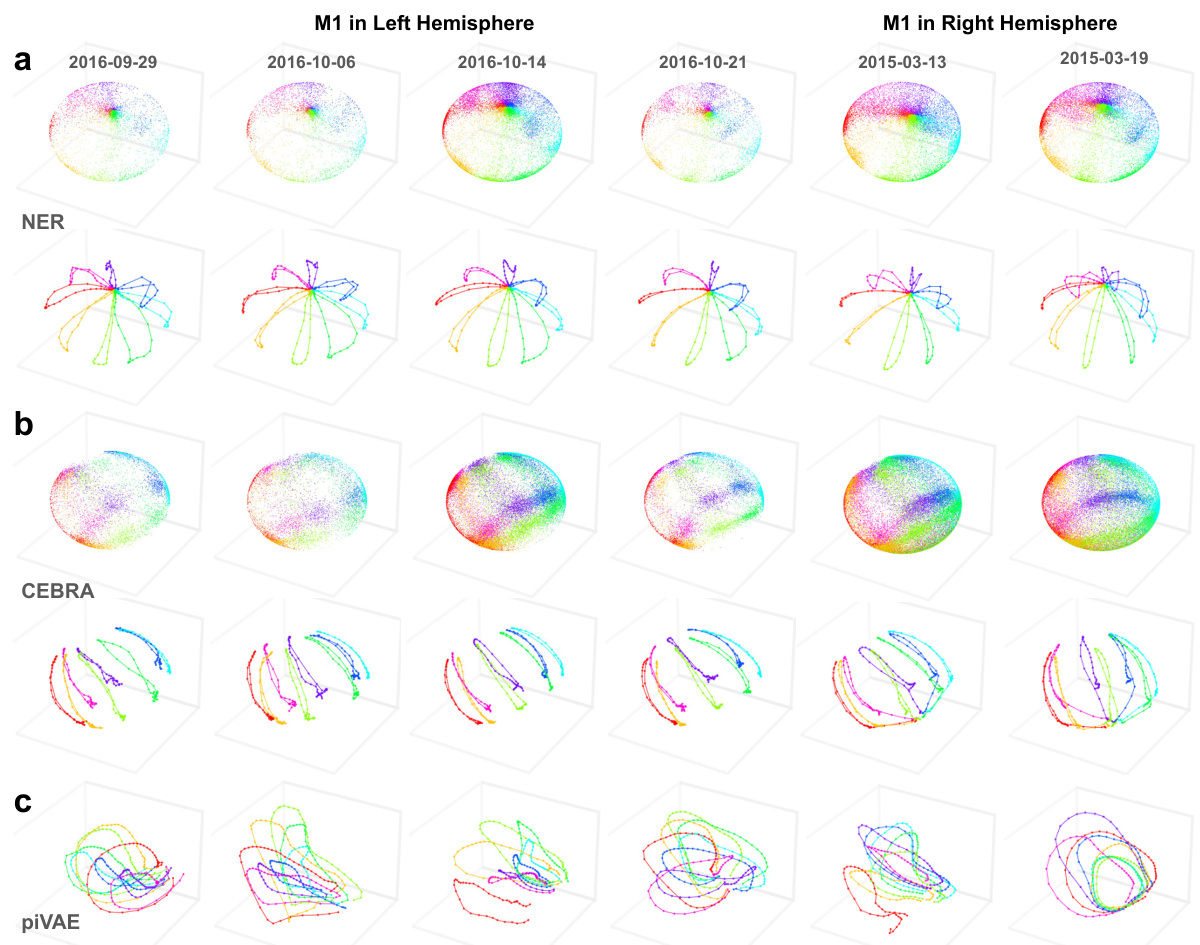

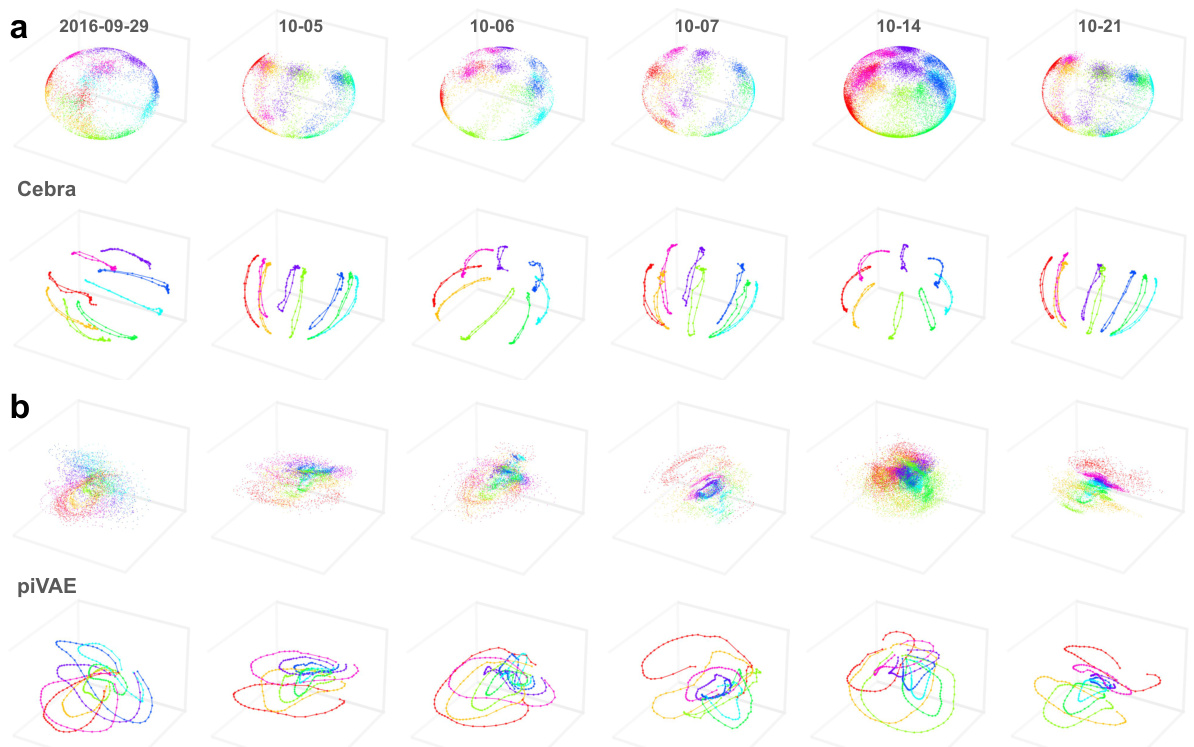

This figure shows the results of applying NER, Cebra, and piVAE dimensionality reduction methods to neural data from additional sessions of monkey M1 recordings. The latent dynamics are visualized across multiple sessions, demonstrating the consistent and movement-aligned patterns revealed by NER over time and across brain hemispheres. In contrast, Cebra and piVAE show less consistent and less clearly movement-aligned results.

This figure shows the latent dynamics for four additional sessions of data from monkey C in M1. It compares the results using NER to those of CEBRA and piVAE. The consistent, movement-aligned latent dynamics revealed by NER are highlighted, showing that even across a year and between hemispheres, the method maintains its ability to align latent dynamics with movements. CEBRA and piVAE show less consistent results.

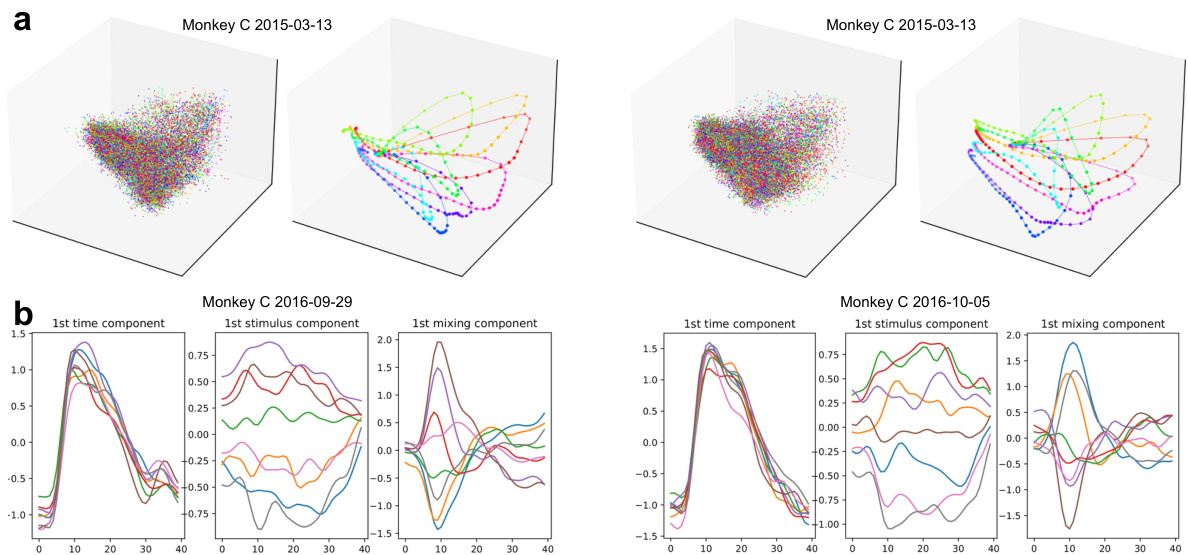

This figure shows a comparison of single-trial and trial-averaged latent dynamics obtained using PCA and dPCA. It highlights that unlike other dimensionality reduction methods, PCA and dPCA produce mixed latent dynamics where individual trials aren’t clearly separated, and only the averages reveal distinct patterns. The trial-averaged results from dPCA are further decomposed into three components: a time component associated with the go cue (consistent across directions), a stimulus component varying over time and direction, and a mixed component combining aspects of time and stimulus.

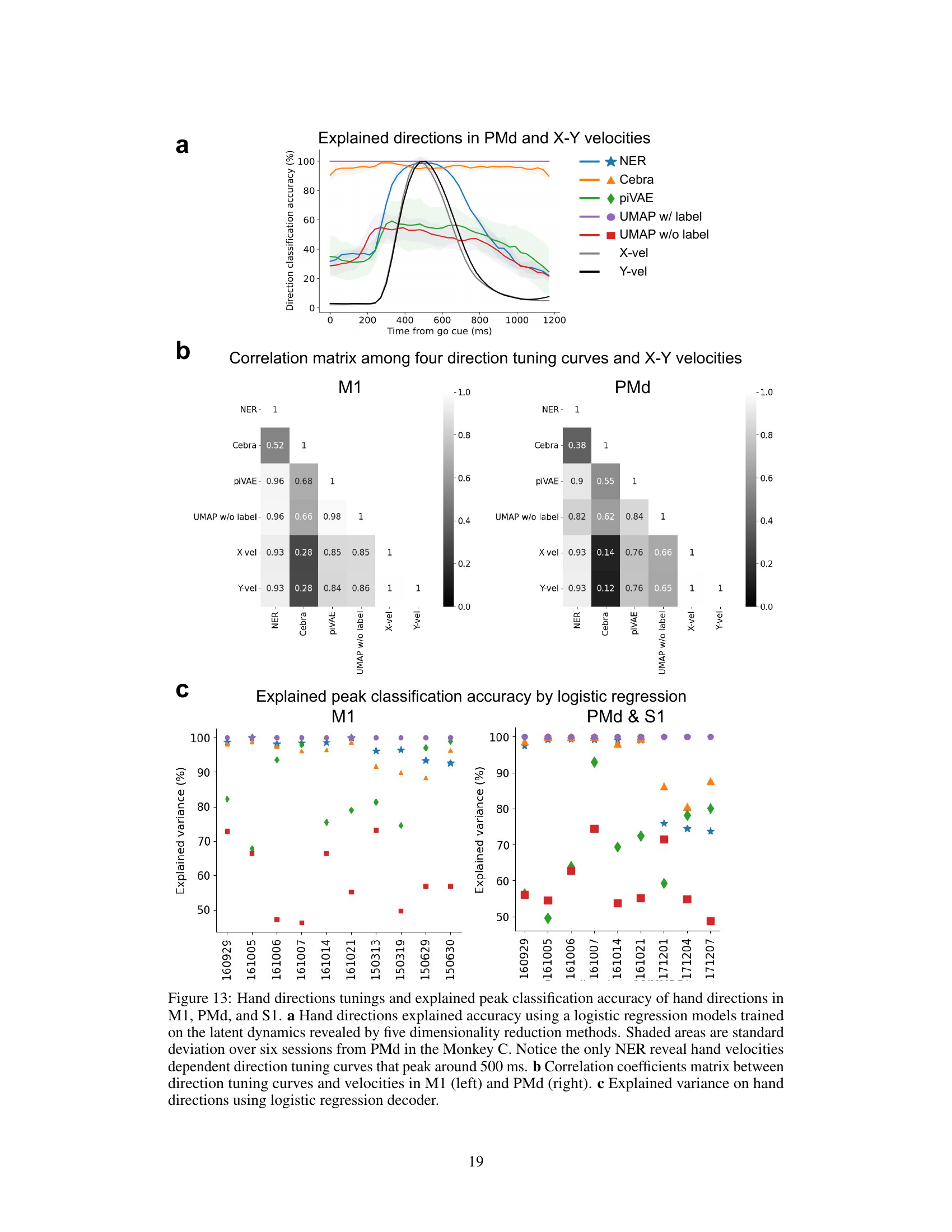

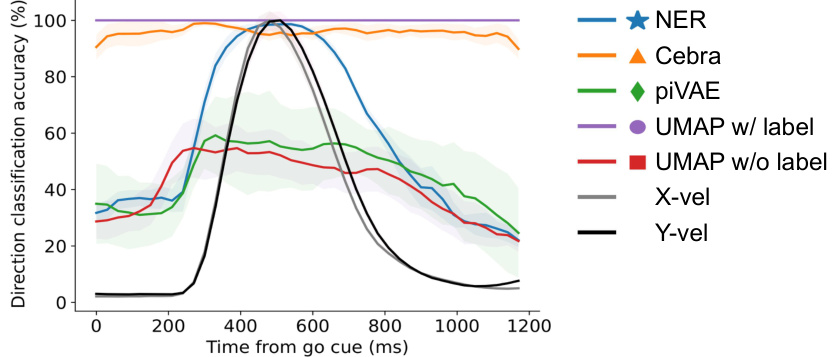

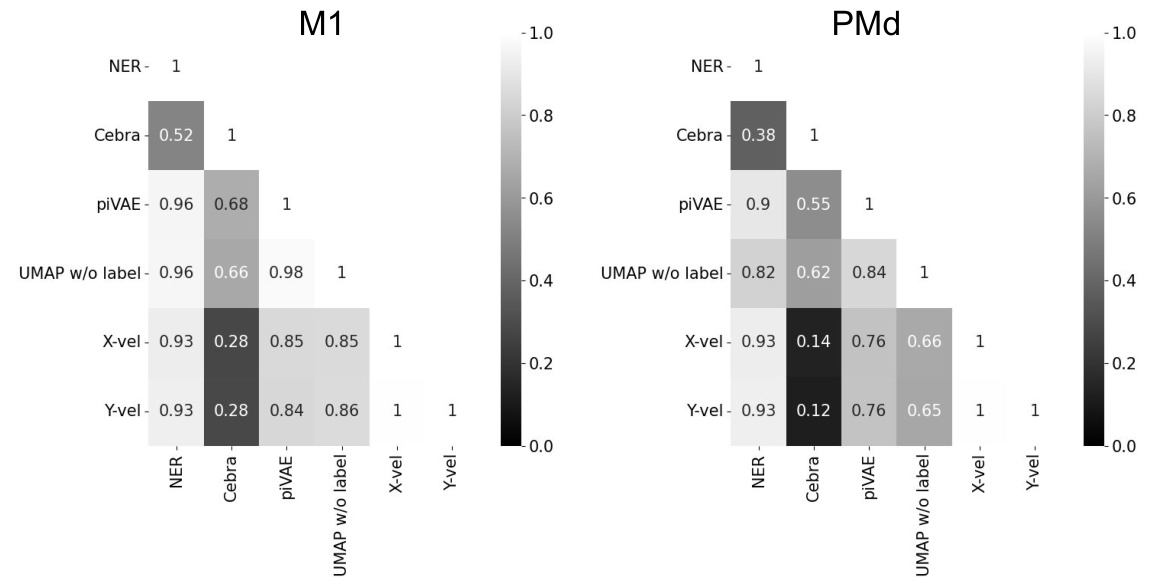

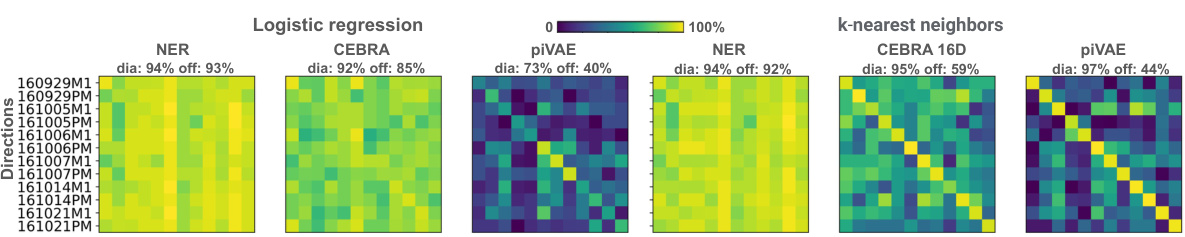

This figure demonstrates the results of applying five dimensionality reduction methods (NER, CEBRA, piVAE, UMAP with/without labels) to decode hand directions. Panel (a) shows the accuracy of hand direction classification over time (from go cue), highlighting that NER peaks around 500ms, while other methods have lower and less focused peaks. Panel (b) presents correlation matrices showing the relationship between direction tuning curves and hand velocities in M1 and PMd, demonstrating that NER’s latent dynamics show a stronger correlation than others. Panel (c) displays the explained variance of hand directions by different methods, indicating NER’s superior performance in explaining hand direction variance in all three brain regions.

This figure demonstrates the consistent and movement-aligned latent dynamics revealed by NER (Neural Embeddings Rank) in the primary motor cortex (M1) across multiple sessions over a year. It compares NER’s performance to CEBRA and piVAE, showing that NER’s latent dynamics consistently align with hand movements, even when sessions are separated by a year. Other dimensionality reduction methods (shown in supplementary figures) failed to reveal the same consistent alignment.

This figure shows the consistent movement-aligned latent dynamics revealed by NER across multiple sessions over a year in the primary motor cortex (M1). It compares NER’s performance with CEBRA and piVAE, highlighting NER’s ability to reveal consistent latent dynamics across different sessions and hemispheres. The figure also includes results from five other dimensionality reduction methods for comparison.

This figure shows the results of applying NER, CEBRA, and piVAE to extract latent dynamics from M1 neural recordings across multiple sessions. The top row displays single-trial and trial-averaged latent dynamics using NER. The next two rows present the same analysis for CEBRA and piVAE, respectively. The consistent movement-aligned latent dynamics revealed by NER across sessions highlight its effectiveness in capturing neural dynamics related to movements.

This figure demonstrates the performance of three dimensionality reduction methods (NER, CEBRA, and piVAE) in decoding hand movements (velocity, position, and direction) within and across sessions, hemispheres, and years in the primary motor cortex (M1). It uses linear and k-nearest neighbor decoders, highlighting NER’s superior and consistent performance across various conditions.

This figure compares the latent dynamics in the somatosensory cortex (S1) as revealed by three different dimensionality reduction methods: NER, CEBRA, and piVAE. The top row shows the latent dynamics when rotated to align with the primary motor cortex (M1), while the bottom row shows the latent dynamics when rotated to align with the first session of S1 data. The comparison illustrates how the different methods represent the neural activity associated with movement in S1, highlighting variations in the structure and consistency of the latent dynamics.

This figure compares the latent dynamics obtained using CEBRA with those from NER (Figure 7) for both straight-curve and curve-curve hand movements. It highlights that CEBRA struggles to separate latent dynamics for different movement types, especially when combining multiple directions, resulting in lower explained variance compared to NER.

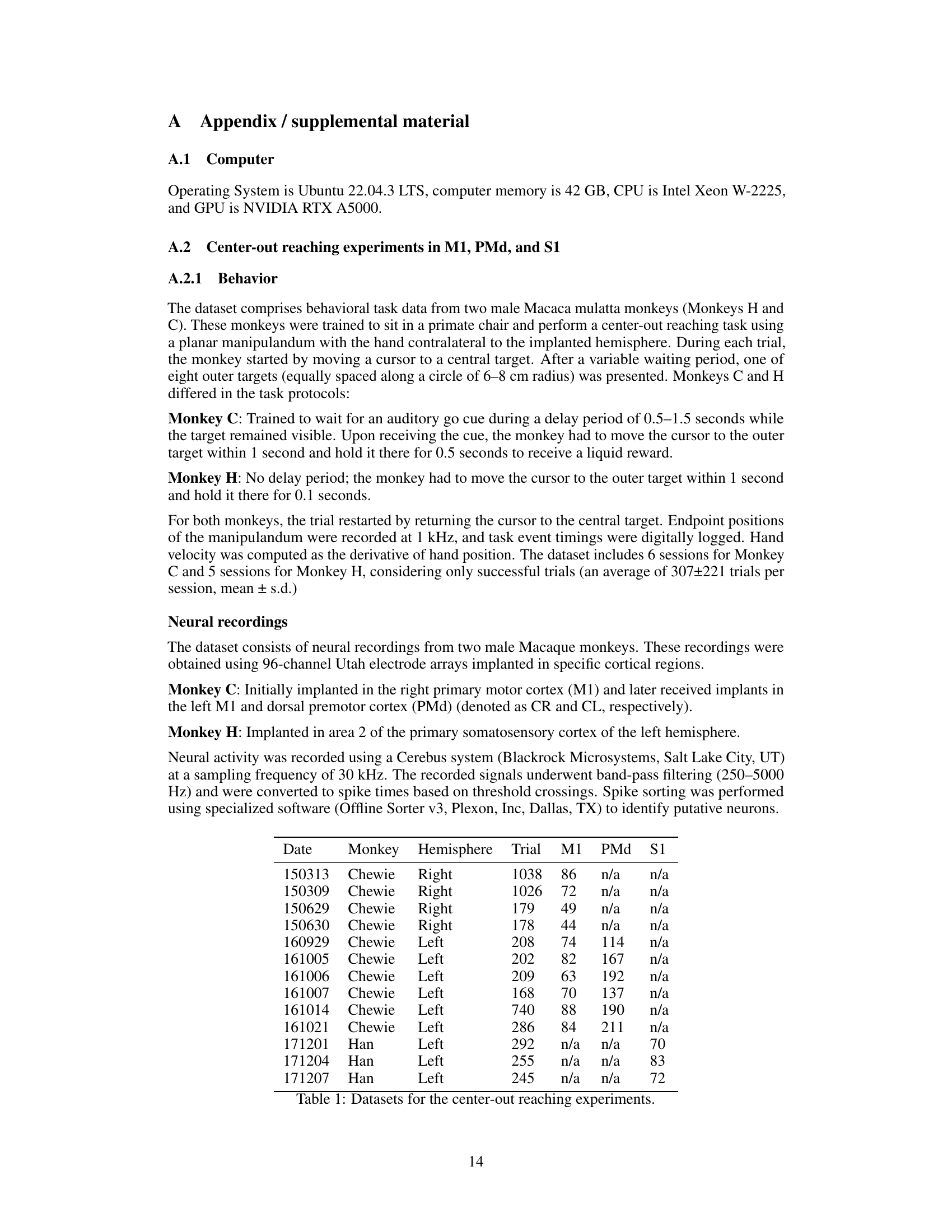

More on tables

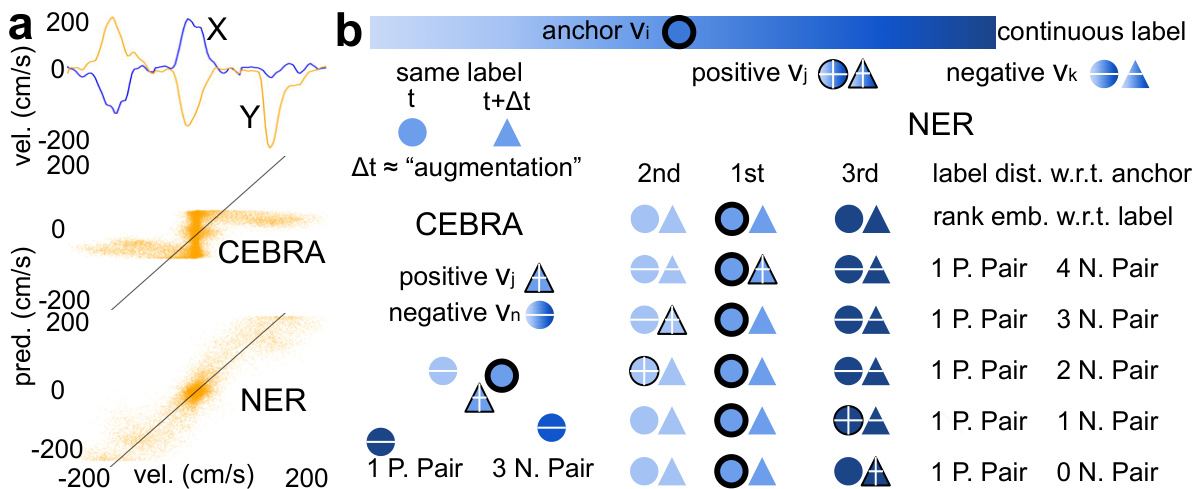

This table lists the datasets used in the center-out reaching experiments. It shows the date of the experiment, the monkey involved (Chewie or Han), the hemisphere in which the neural recordings were taken, the total number of trials, and the number of neurons recorded from the primary motor cortex (M1), dorsal premotor cortex (PMd), and primary somatosensory cortex (S1). Note that some sessions lack recordings from PMd and S1.

This table presents a statistical analysis comparing the performance of NER, CEBRA, and piVAE across different sessions and brain regions (M1, PMd, and S1). The table uses correlation coefficients to assess the similarity of latent dynamics between different sessions, distinguishing between within-session (diagonal) and cross-session (off-diagonal) comparisons. It also provides t-statistics and p-values for these comparisons, offering insights into the statistical significance of the observed differences. In essence, it quantifies the consistency and generalizability of the latent dynamics discovered by each method.

Full paper#