↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current zero-shot object navigation struggles with limited context, hindering accurate and explainable navigation. Existing methods rely on simple textual descriptions of nearby objects, failing to capture rich scene context. This leads to unreliable and difficult-to-interpret results.

SG-Nav introduces a novel framework that uses a hierarchical 3D scene graph to represent the environment, offering a more comprehensive context to the LLM. A chain-of-thought prompting strategy guides the LLM’s reasoning process through the scene graph, leading to more accurate and explainable decisions. Furthermore, SG-Nav incorporates a re-perception mechanism to improve the reliability of navigation by validating detected objects and correcting errors. These improvements yield significant performance gains compared to prior art.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances zero-shot object navigation, a crucial area in robotics. Its novel 3D scene graph approach and hierarchical prompting method improve accuracy and explainability, overcoming limitations of prior methods. This opens avenues for more robust and explainable AI systems in complex environments, impacting various research areas.

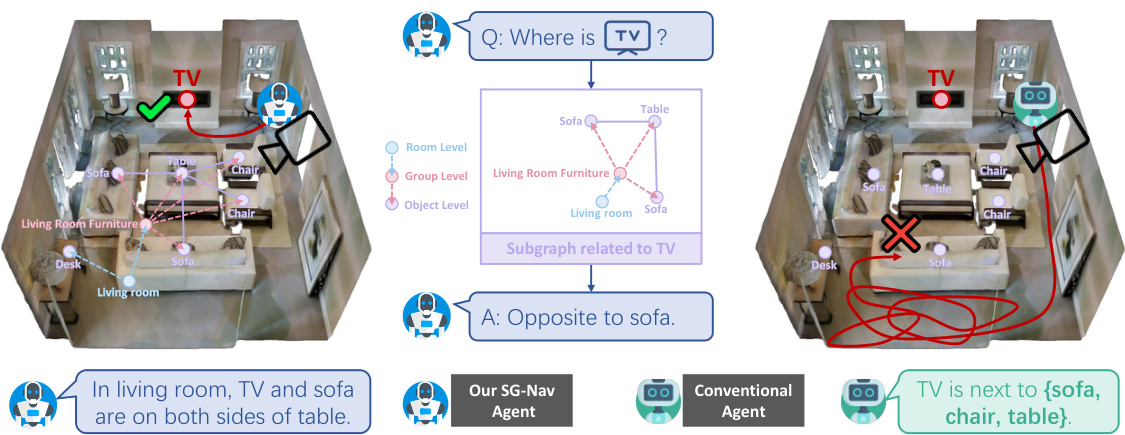

Visual Insights#

The figure compares SG-Nav with conventional zero-shot object navigation methods. Conventional methods use only textual descriptions of nearby objects, lacking rich scene context. SG-Nav leverages a hierarchical 3D scene graph representing the observed environment, allowing the LLM to utilize structural information for more accurate and explainable decisions. This improved context leads to better performance and reasoning.

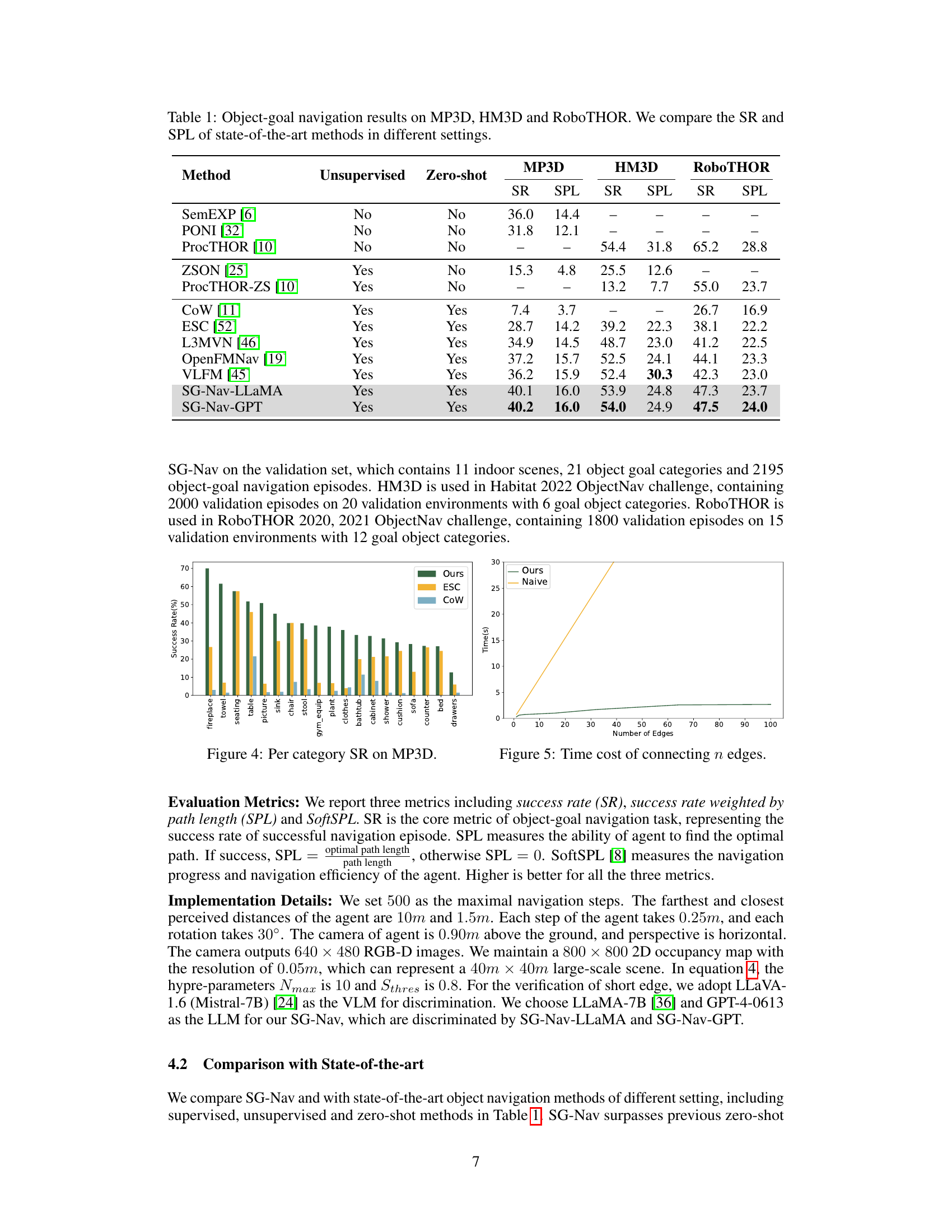

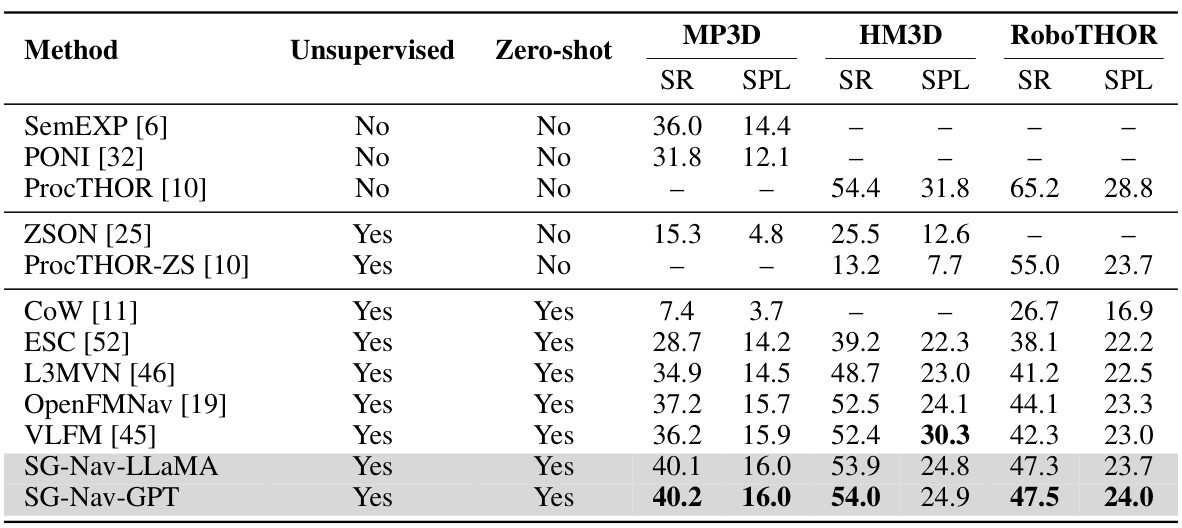

This table presents a comparison of the success rate (SR) and success rate weighted by path length (SPL) achieved by various object navigation methods on three benchmark datasets: MP3D, HM3D, and RoboTHOR. The methods are categorized into unsupervised and zero-shot approaches, highlighting the performance differences between methods trained with supervision and those that do not require any training. The table allows for a direct comparison of the state-of-the-art performance for each dataset and approach type.

In-depth insights#

Zero-Shot Nav#

Zero-shot object navigation, or “Zero-Shot Nav,” presents a significant challenge in robotics, aiming to enable agents to navigate to unseen objects using only their textual descriptions. This approach eliminates the need for extensive training data specific to each object category, improving generalization and reducing development time. However, this requires robust methods for bridging the gap between language and visual perception, often leveraging powerful Language Models (LLMs) to interpret the textual goal and reason about the scene. A key challenge lies in effectively representing the 3D environment in a format that LLMs can process efficiently and meaningfully, often incorporating scene graphs or other structured representations. Successful approaches must address inherent ambiguities in language, handle perceptual noise, and manage the computational demands of online reasoning within the LLM. Explainability and robustness are also crucial factors, as understanding the LLM’s decision-making process is important for debugging and building trust. Future advancements could explore improved methods for integrating multimodal information, developing more efficient scene representations, and enhancing the reasoning capabilities of LLMs to further advance zero-shot navigation abilities.

Scene Graph#

The concept of a scene graph is central to many computer vision and AI applications, offering a structured representation of a scene’s elements and their relationships. A scene graph typically consists of nodes representing objects and their attributes, connected by edges defining relationships such as spatial proximity, part-whole, or action-object. Its strength lies in moving beyond simple object detection, offering richer contextual understanding. Building a scene graph can be challenging, as it requires robust object detection, relationship inference, and handling variations in scene complexity. Effective scene graph construction frequently involves advanced techniques like graph neural networks, leveraging both visual and semantic information. A well-constructed scene graph is valuable in applications such as visual question answering, scene understanding, and robot navigation, empowering algorithms to reason about the relationships between objects and solve more complex tasks.

LLM Prompting#

The effectiveness of Large Language Models (LLMs) hinges significantly on the design and execution of prompting strategies. Effective prompting leverages the LLM’s inherent knowledge and reasoning capabilities to elicit desired outputs, going beyond simple keyword searches. For navigation tasks, effective prompts should provide sufficient contextual information about the environment and the goal object. This could involve describing object relationships, spatial layouts, and relevant characteristics in a structured way. Prompt engineering needs to be iterative, involving experimentation and refinement to optimize prompt design for specific LLMs and tasks. Hierarchical prompting offers a method for complex reasoning, breaking down the task into manageable sub-tasks and guiding the LLM’s process systematically. Chain-of-thought prompting encourages the LLM to explicitly articulate its reasoning steps, which improves transparency and allows for better analysis and debugging of the model’s response. A well-crafted prompt is crucial for achieving high accuracy, efficiency, and explainability in LLM-based object navigation systems.

Re-perception#

The concept of ‘Re-perception’ in this context is a crucial mechanism for enhancing the robustness of zero-shot object navigation. It directly addresses the limitations of relying solely on initial perception by implementing a re-evaluation process of detected objects. Instead of blindly accepting the first detected goal object, the agent actively gathers more observations and accumulates credibility scores. This method reduces the impact of false positive detections, a significant issue in zero-shot settings where the model lacks prior training data and may misinterpret visual input. By integrating multi-view observations and probabilistic measures, the system can intelligently reject unreliable identifications, thereby improving navigation accuracy and reliability. The explainable nature of the re-perception mechanism adds to its value, offering insights into the decision-making process which is important for trust and debugging.

SG-Nav Limits#

Despite its impressive performance, SG-Nav has limitations. The reliance on online 3D instance segmentation for scene graph construction is a crucial weakness. Current methods, which combine 2D vision-language models and vision foundation models, are not fully 3D-aware and could hinder performance. A more robust, end-to-end 3D instance segmentation would significantly improve SG-Nav’s accuracy and efficiency. The framework’s current limitations to object-goal navigation restricts its broader applicability. While the strong zero-shot generalization of LLMs and the rich scene context in the 3D graph suggest potential for extension to other tasks (image-goal navigation, vision-and-language navigation), further research is needed to explore this. The computational cost of building the hierarchical scene graph and performing the hierarchical chain-of-thought prompting with the LLM could also present challenges, especially in large or complex environments. Finally, while the re-perception mechanism improves robustness, it cannot completely eliminate errors stemming from inaccurate initial object detection or false positives.

More visual insights#

More on figures

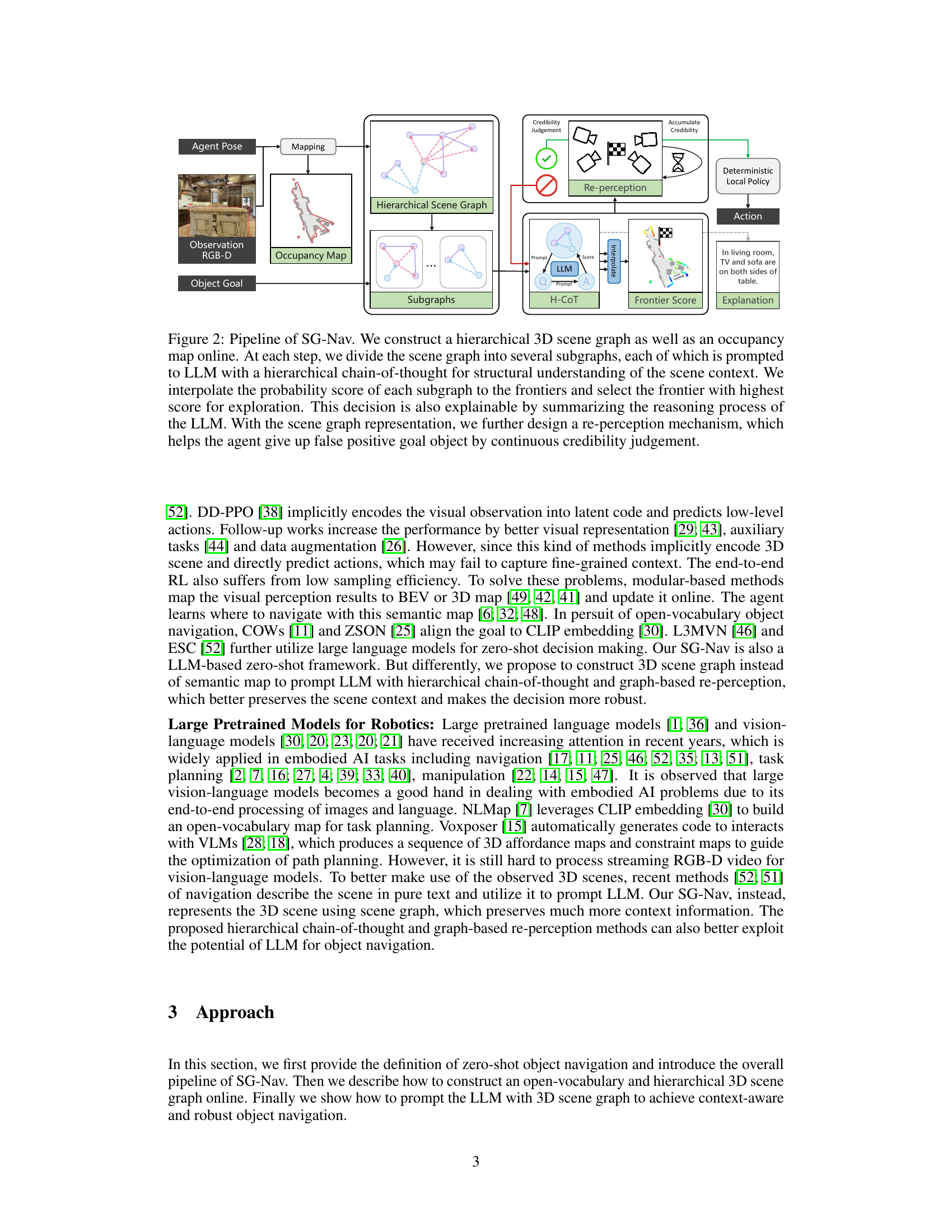

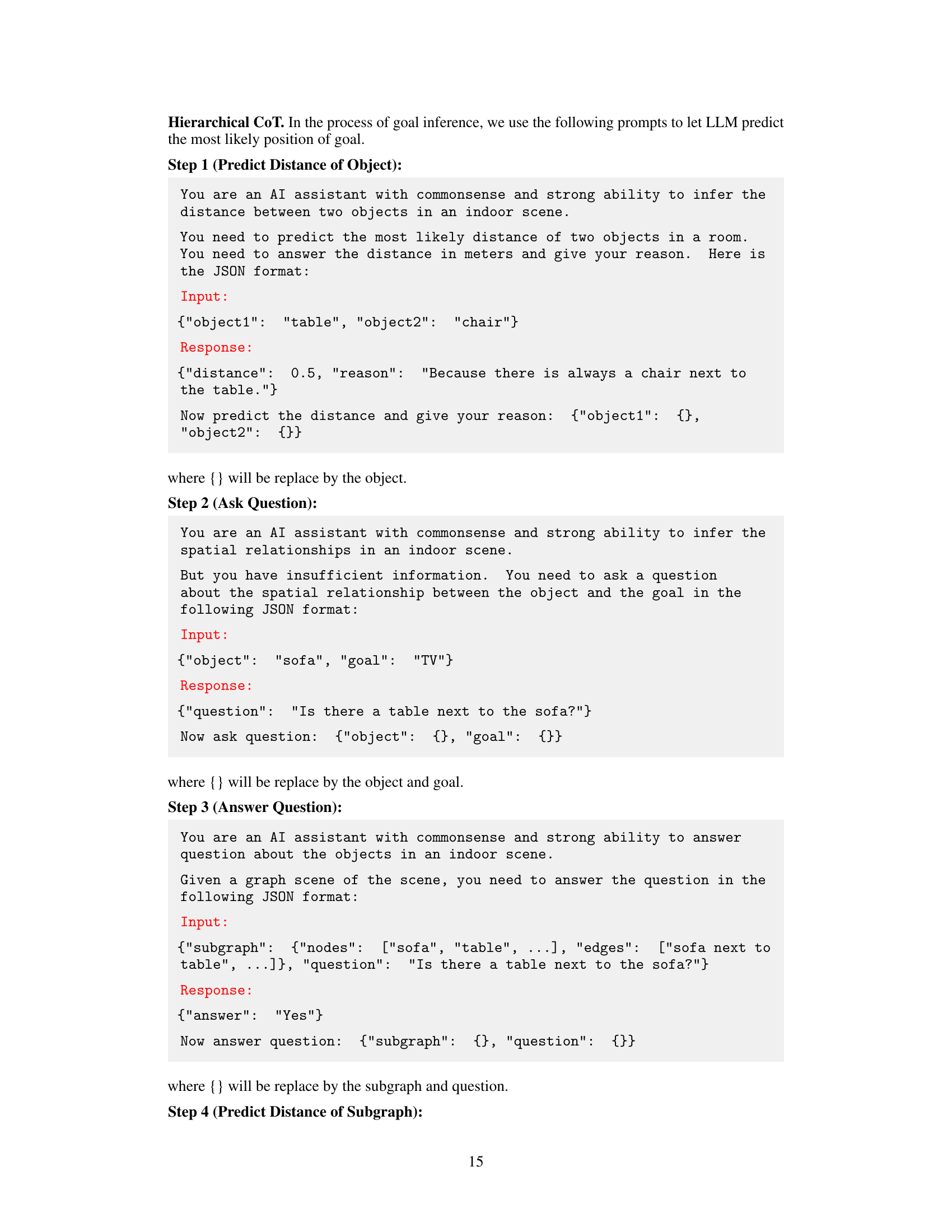

This figure illustrates the pipeline of the SG-Nav object navigation framework. It starts with agent pose and observation (RGB-D image), which are used to create an occupancy map and a hierarchical 3D scene graph. The scene graph is divided into subgraphs, each of which is used as input to a large language model (LLM) along with a hierarchical chain-of-thought prompt to reason about the scene and predict the probability of the goal object being near each subgraph. These probabilities are then used to assign a score to each frontier (possible next navigation step). A credibility judgement and re-perception mechanism are used to help avoid false positives and ensure robustness. Finally, a deterministic local policy determines the next action (move, turn, or stop) and the reasoning is presented as an explanation.

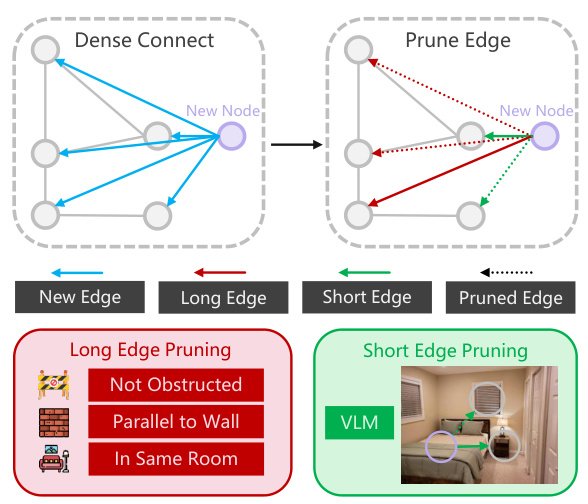

This figure illustrates the incremental process of building the scene graph in SG-Nav. Newly detected nodes (purple) are densely connected to existing nodes via efficient LLM prompting. Edges are categorized as long or short, with less informative edges pruned using different strategies (long edges are pruned based on spatial and structural relationships; short edges are pruned based on VLM verification of relationships). This ensures efficient and accurate graph construction during online navigation.

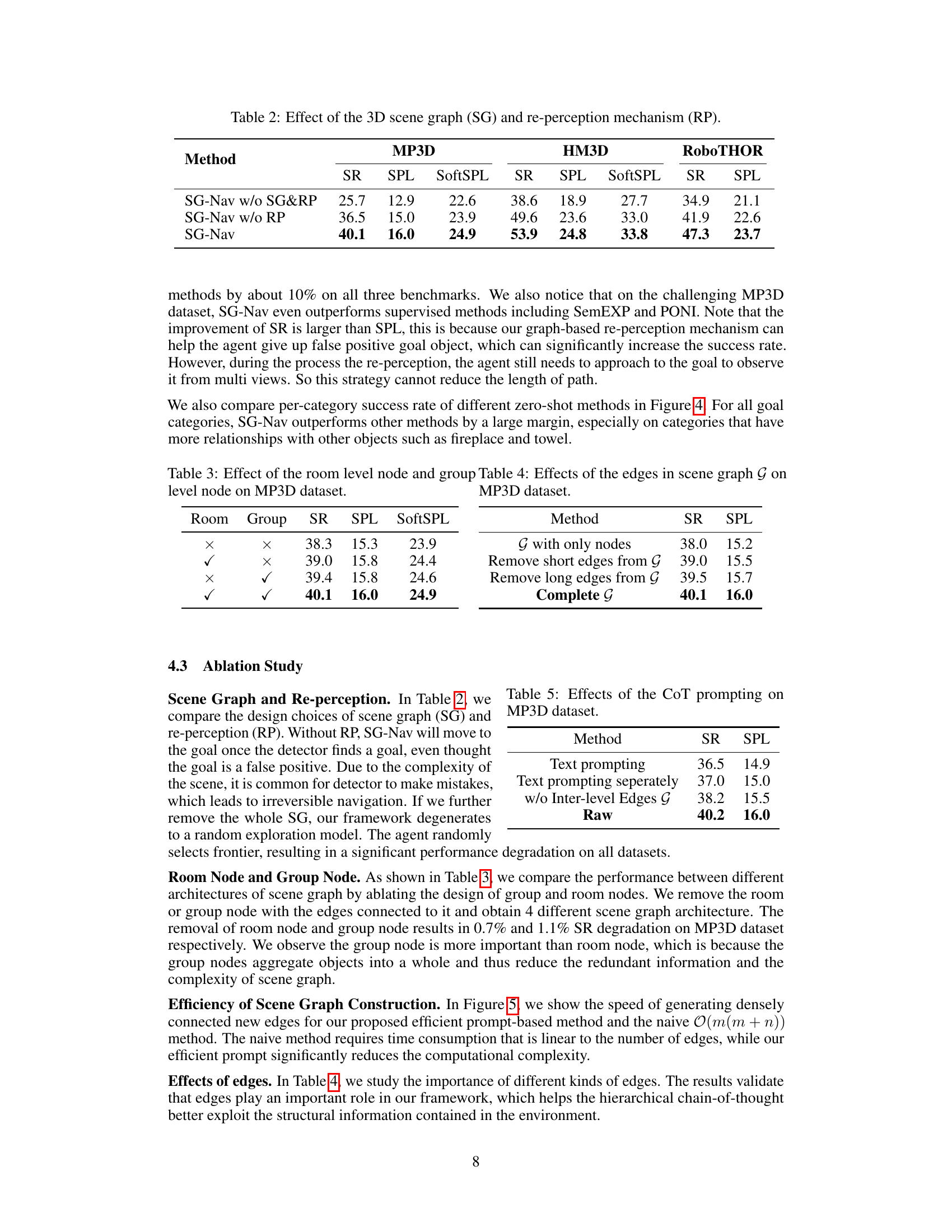

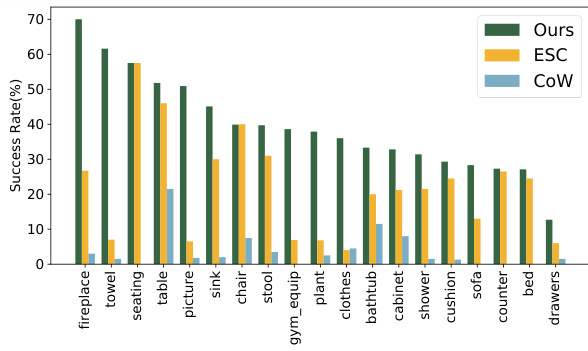

This figure shows the success rate (SR) for each object category in the Matterport3D (MP3D) dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed SG-Nav method against two other zero-shot methods (ESC and CoW). The figure visually represents the varying difficulty of navigating to different object types, highlighting the superior performance of SG-Nav across nearly all categories.

The figure shows a comparison of the time cost for connecting newly detected nodes to existing nodes in a scene graph using two different methods. The ‘Ours’ method demonstrates a linear time complexity, while the ‘Naive’ method exhibits a quadratic time complexity. This highlights the efficiency of the proposed incremental edge updating and pruning method in the paper, enabling real-time scene graph construction.

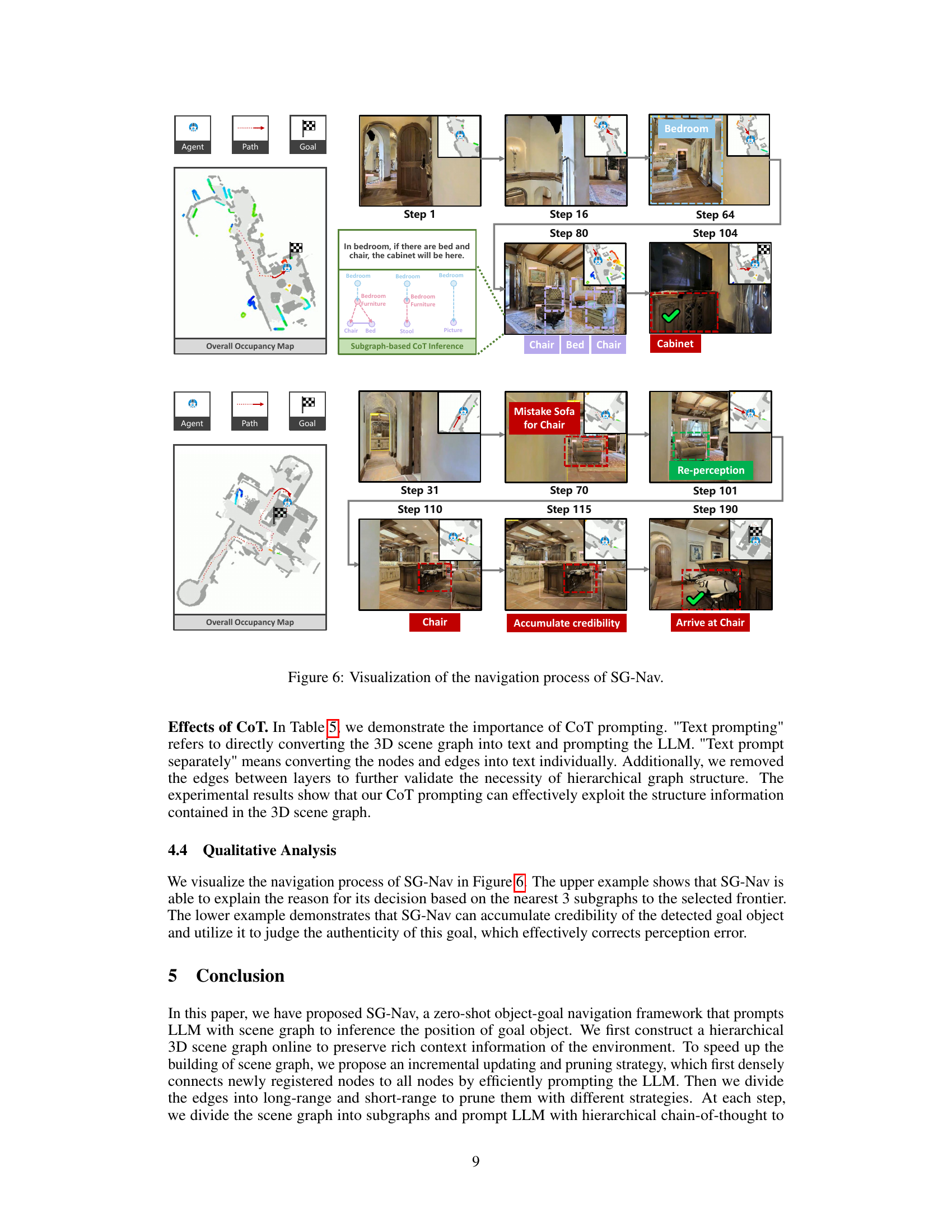

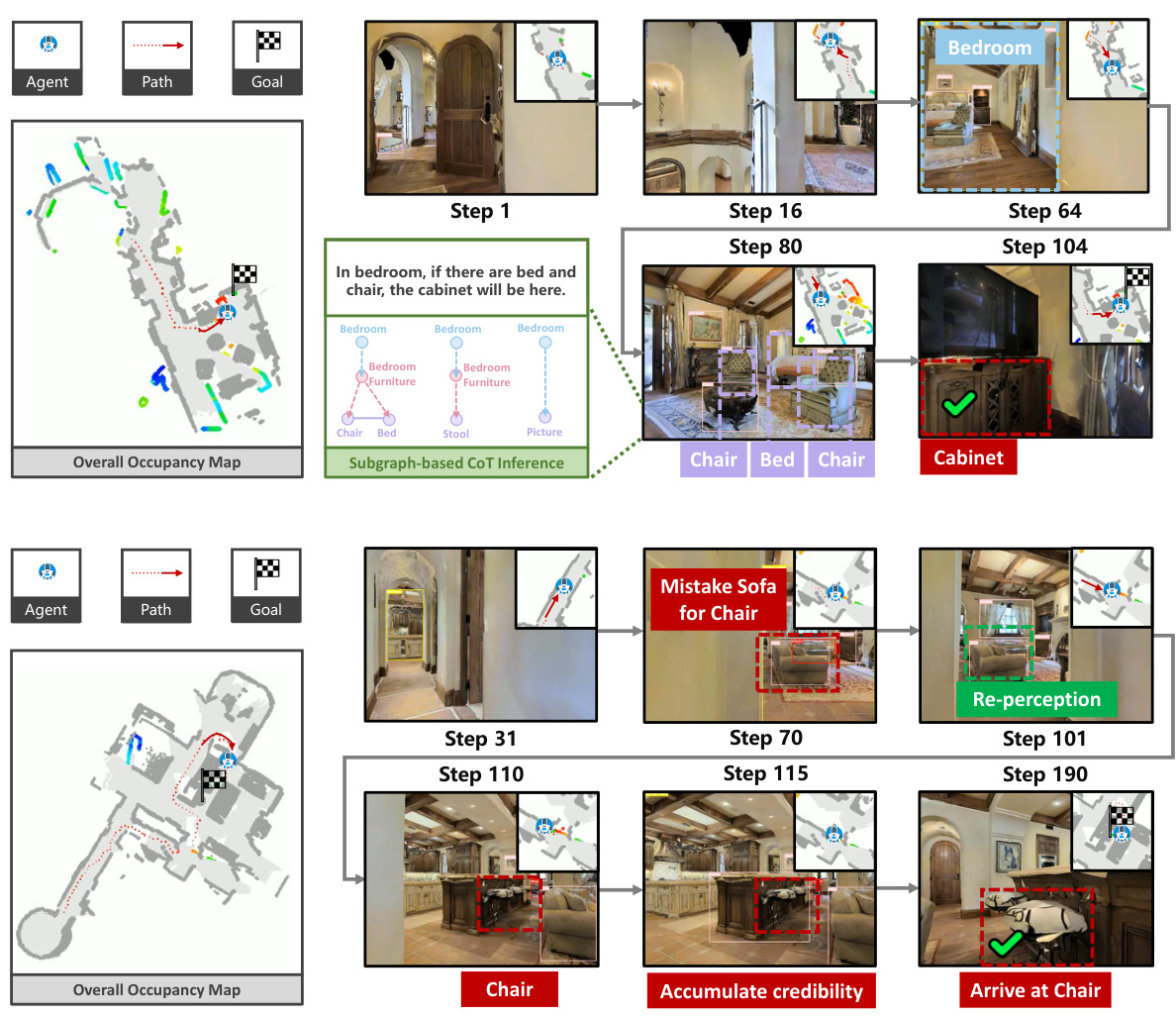

This figure visualizes two example navigation processes using SG-Nav. The top example shows a successful navigation where the agent effectively uses hierarchical chain-of-thought prompting with subgraph information to reason about the goal location. The bottom example shows how SG-Nav handles false positive goal object detection by incorporating a re-perception mechanism. The agent approaches the suspected goal object from multiple viewpoints, accumulating credibility scores to confirm or reject the initial detection. If the credibility falls below a threshold, the agent abandons the suspected object and continues exploring.

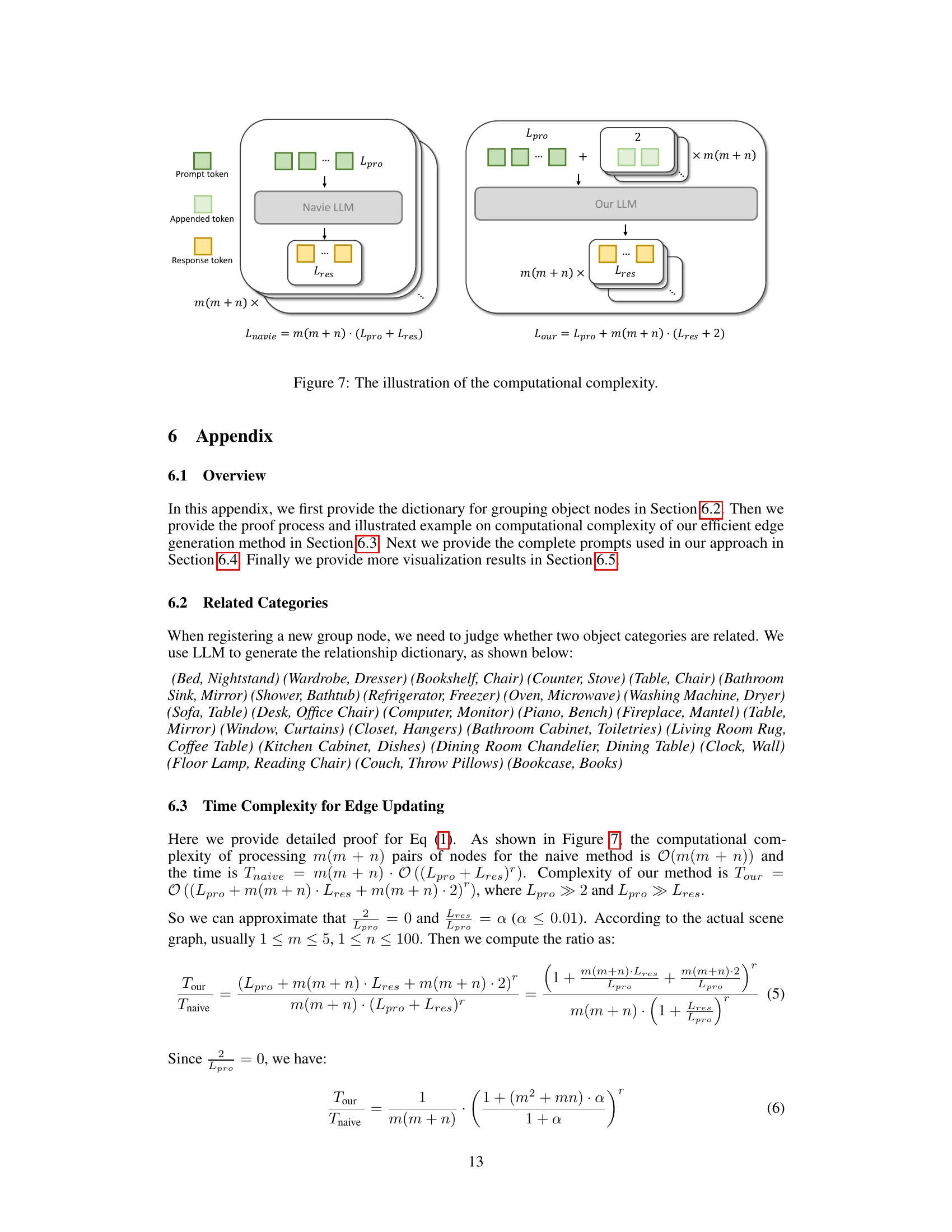

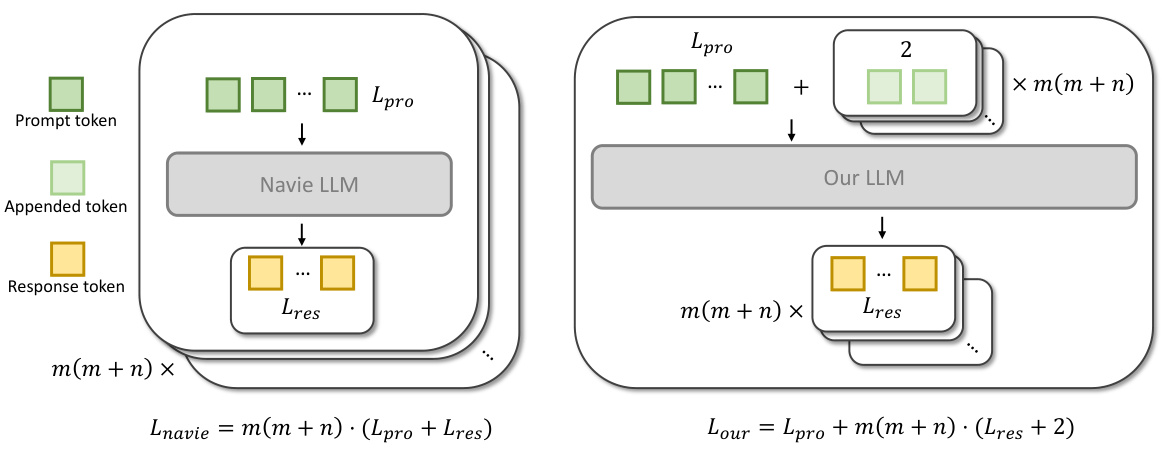

This figure illustrates the computational complexity comparison between the naive method and the proposed method for densely connecting newly registered nodes to previous nodes in a scene graph. The naive method involves processing each pair of nodes individually, resulting in O(m(m+n)) complexity, where ’m’ is the number of new nodes and ’n’ is the number of previous nodes. In contrast, the proposed method uses a more efficient prompt to process all node pairs simultaneously, reducing the complexity to O(m). The figure visually represents this difference by showing the repeated processing steps in the naive method versus the single processing step in the proposed method. The formulas Lnavie = m(m + n) · (Lpro + Lres) and Lour = Lpro + m(m + n) · (Lres + 2) further quantify the complexity difference, where Lpro represents prompt tokens and Lres represents response tokens.

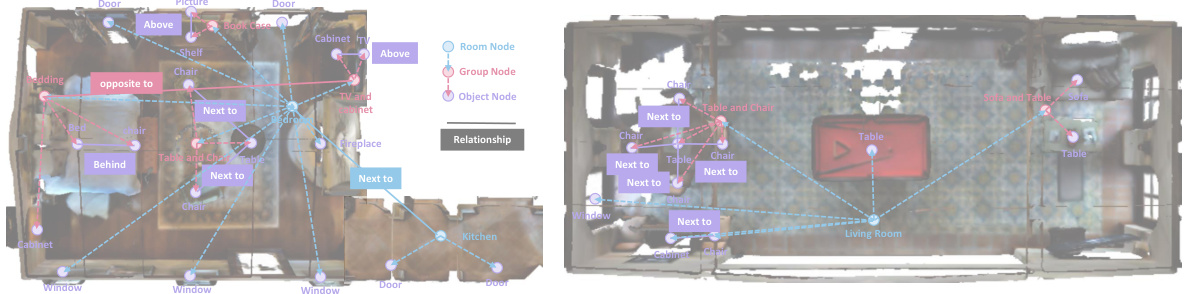

This figure visualizes two examples of 3D scene graphs generated by the SG-Nav model. The left graph shows a bedroom scene with various objects and their relationships (e.g., ‘above’, ’next to’, ‘behind’) represented by edges connecting nodes. Object, group, and room level nodes are indicated by different colors. The right graph displays a living room scene, again illustrating the hierarchical relationships between objects. These graphs illustrate how SG-Nav represents the environment using a hierarchical structure to improve LLM-based reasoning for navigation.

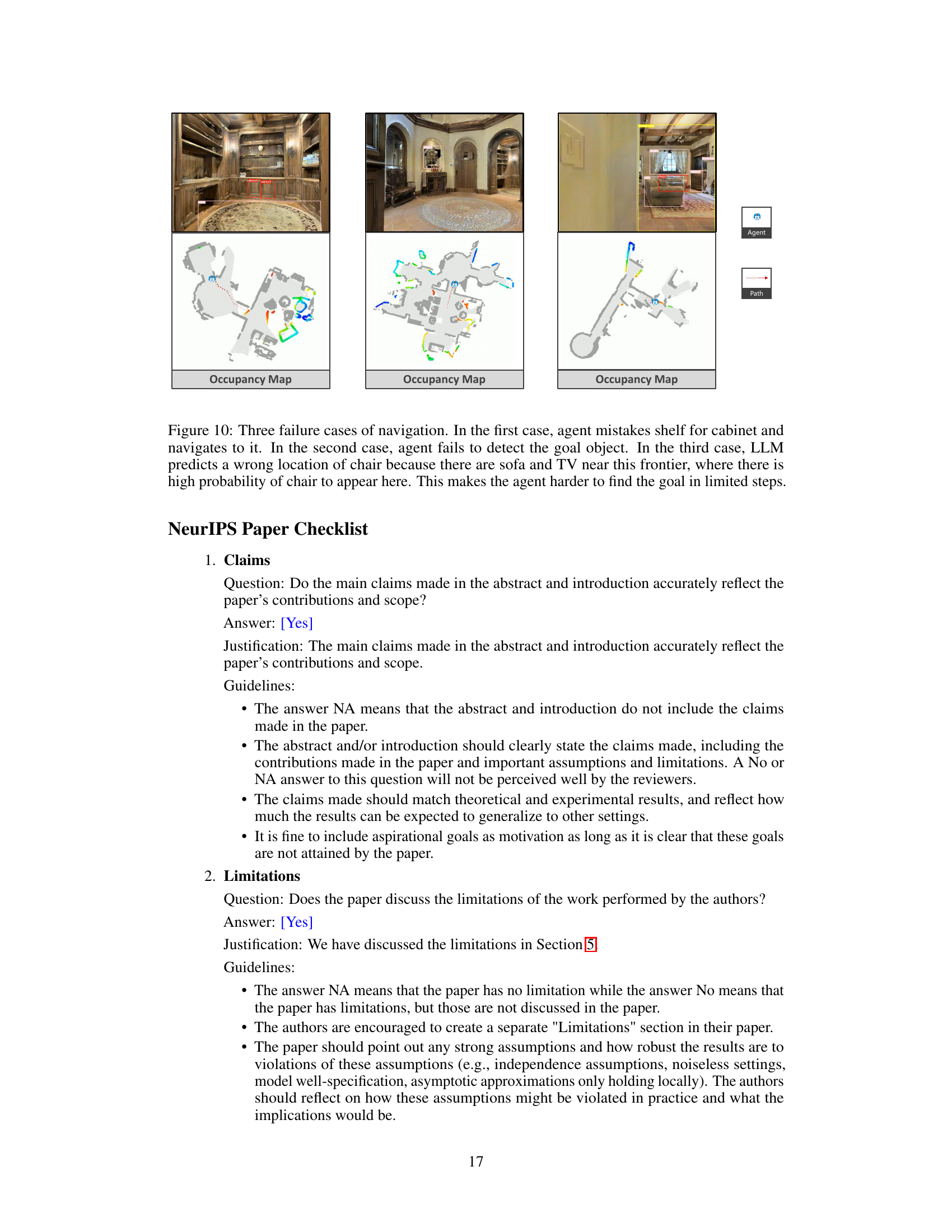

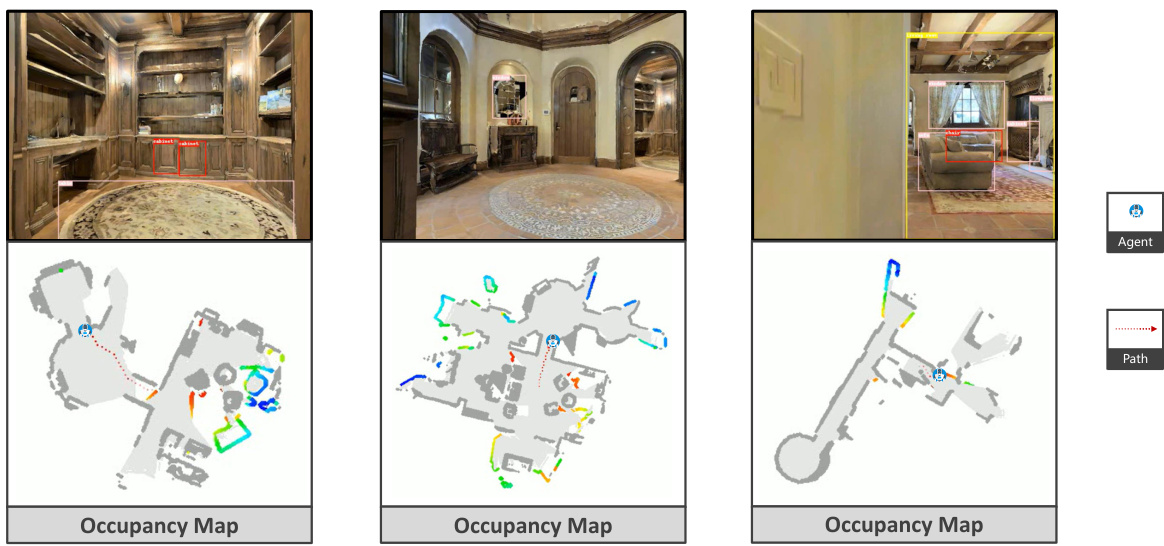

This figure visualizes the navigation process using SG-Nav, showing how the agent explores the environment step-by-step. It highlights the hierarchical chain-of-thought prompting of the LLM, the online occupancy map, and the graph-based re-perception mechanism. The example demonstrates the system’s ability to correct false positive goal object detections and provide explainable decisions based on the scene graph structure and LLM reasoning.

This figure visualizes two example navigation processes using the SG-Nav approach. The upper example shows how the model uses a hierarchical chain-of-thought to reason through the scene graph, providing explanations for its decisions. The lower example demonstrates the graph-based re-perception mechanism, which helps the agent to avoid false positive goal object detections and corrects perception errors by accumulating credibility scores over multiple observations. The visualizations include the occupancy map, the agent’s path, the goal object, and screenshots of the agent’s view at different steps during the navigation process. The images illustrate how SG-Nav uses scene understanding and re-perception to make reliable and explainable navigation decisions.

More on tables

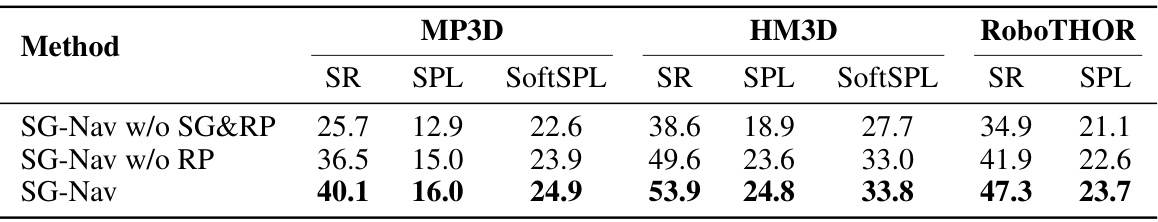

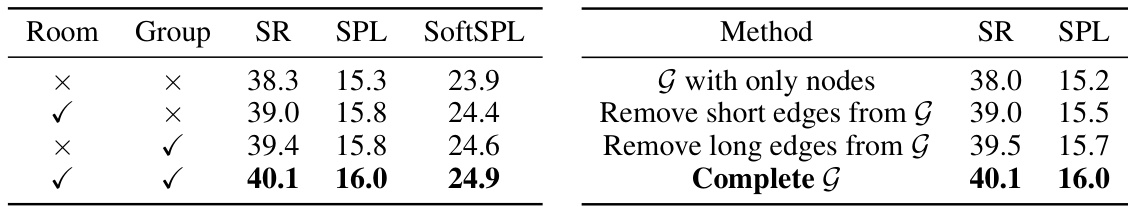

This table presents the ablation study results, showing the impact of removing the 3D scene graph and/or re-perception mechanism from the SG-Nav model. The results are shown in terms of Success Rate (SR), Success Rate weighted by path length (SPL), and SoftSPL, which measures navigation efficiency. The performance of the full SG-Nav model is compared to versions without the scene graph, without the re-perception mechanism, and without both.

This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of the 3D scene graph and the re-perception mechanism on the performance of the SG-Nav model. It compares the success rate (SR), success rate weighted by path length (SPL), and SoftSPL across different settings: with both SG and RP, without RP, and without both SG and RP. The results demonstrate the importance of both components for achieving high performance in zero-shot object navigation.

This table presents ablation study results on the effects of different prompting methods on the MP3D dataset. It compares the success rate (SR) and success rate weighted by path length (SPL) achieved by four methods: basic text prompting, text prompting with separated nodes and edges, text prompting without inter-level edges in the scene graph, and the proposed hierarchical chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting method. The results demonstrate the superiority of the CoT prompting approach for achieving the best performance in object navigation.

Full paper#