↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The human brain remarkably creates similar cognitive maps for both spatial and abstract environments using grid cells. However, current computational models struggle to explain how this generalization is achieved efficiently. The paper aims to address this by proposing that the brain maps spatial domains to abstract cognitive spaces by extracting low-dimensional descriptions of displacements. This sidesteps the computational cost associated with high-dimensional sensory inputs.

The paper proposes a neural network model to learn consistent, low-dimensional velocity signals across various abstract domains. This self-supervised model leverages geometric consistency constraints and outperforms conventional methods in dimensionality reduction and motion extraction. The model highlights the importance of grid cells, demonstrating that they maintain their population correlation and manifold structure across different domains, thus explaining their flexible cognitive mapping capabilities and providing a potential self-supervised framework for transfer learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in neuroscience and AI because it introduces a novel self-supervised learning framework for understanding how the brain represents abstract cognitive spaces and offers a potential blueprint for creating more flexible and data-efficient AI systems that can generalize effectively across different domains. It also suggests new experimental predictions, which can guide future research.

Visual Insights#

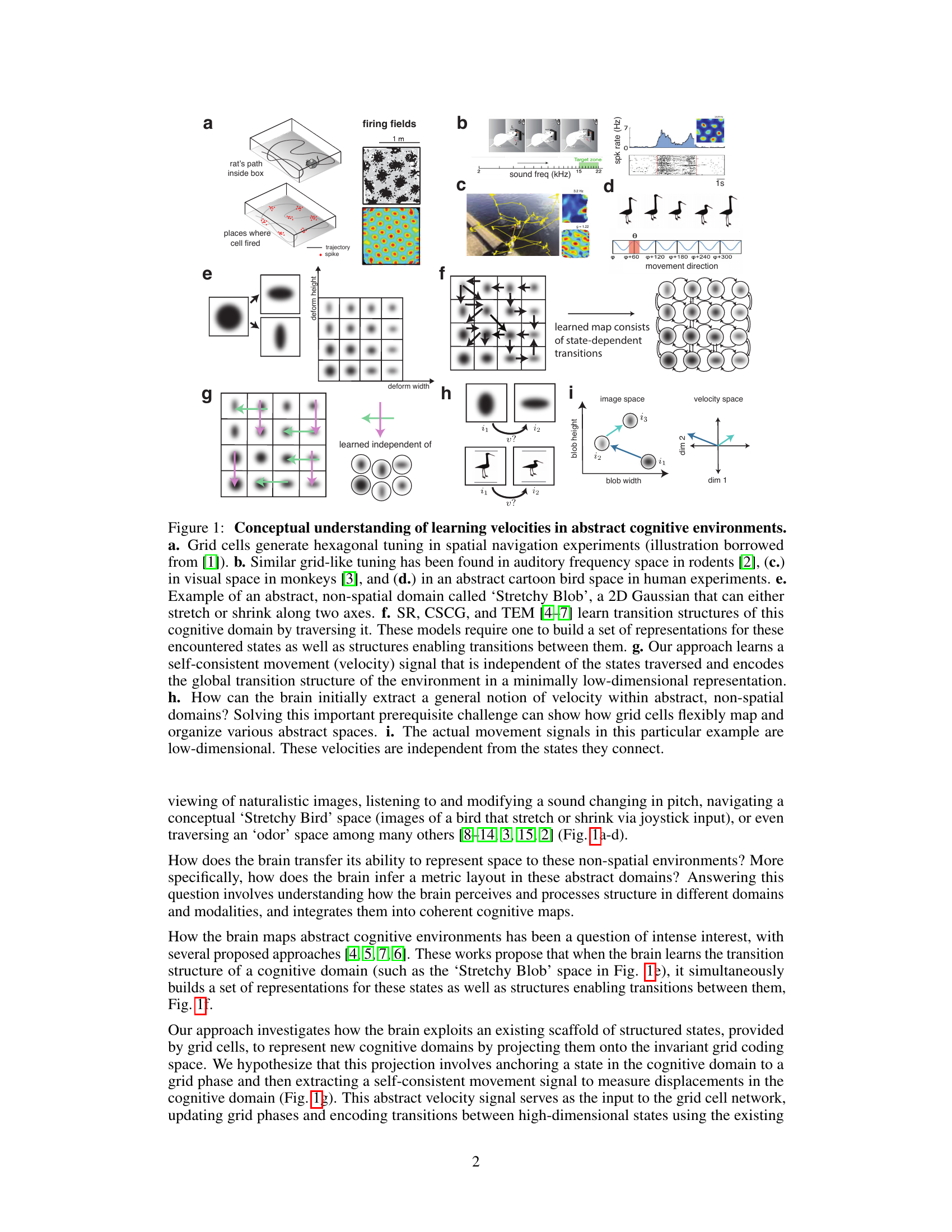

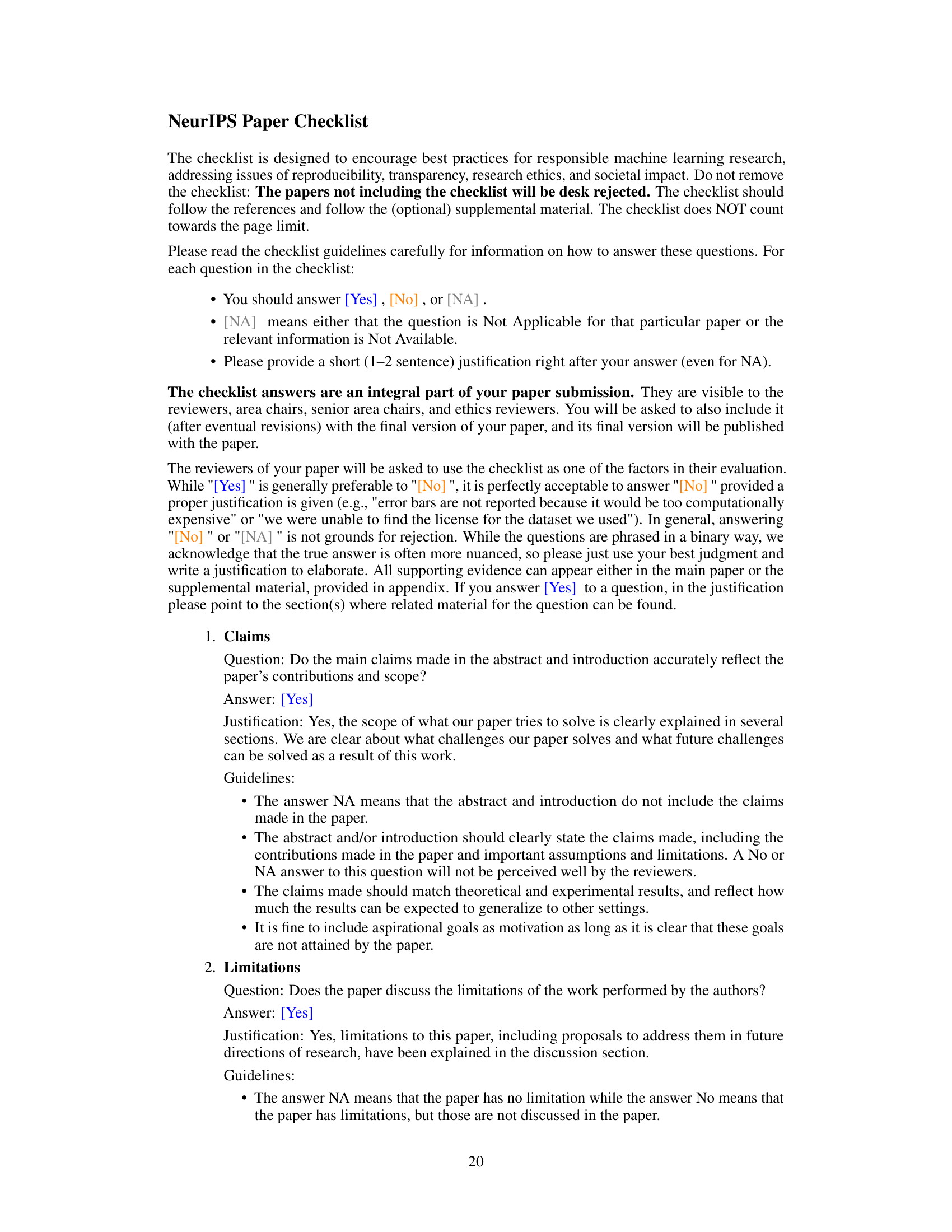

This figure provides a conceptual overview of how the brain learns velocities in abstract cognitive environments. It contrasts traditional approaches that learn state representations and transitions with the proposed approach that extracts low-dimensional, state-independent velocity signals for efficient map generation. The figure uses examples like spatial navigation, auditory tone sequences, visual space, and abstract cartoon spaces to illustrate the concept, highlighting the flexibility of grid cells in mapping diverse abstract domains.

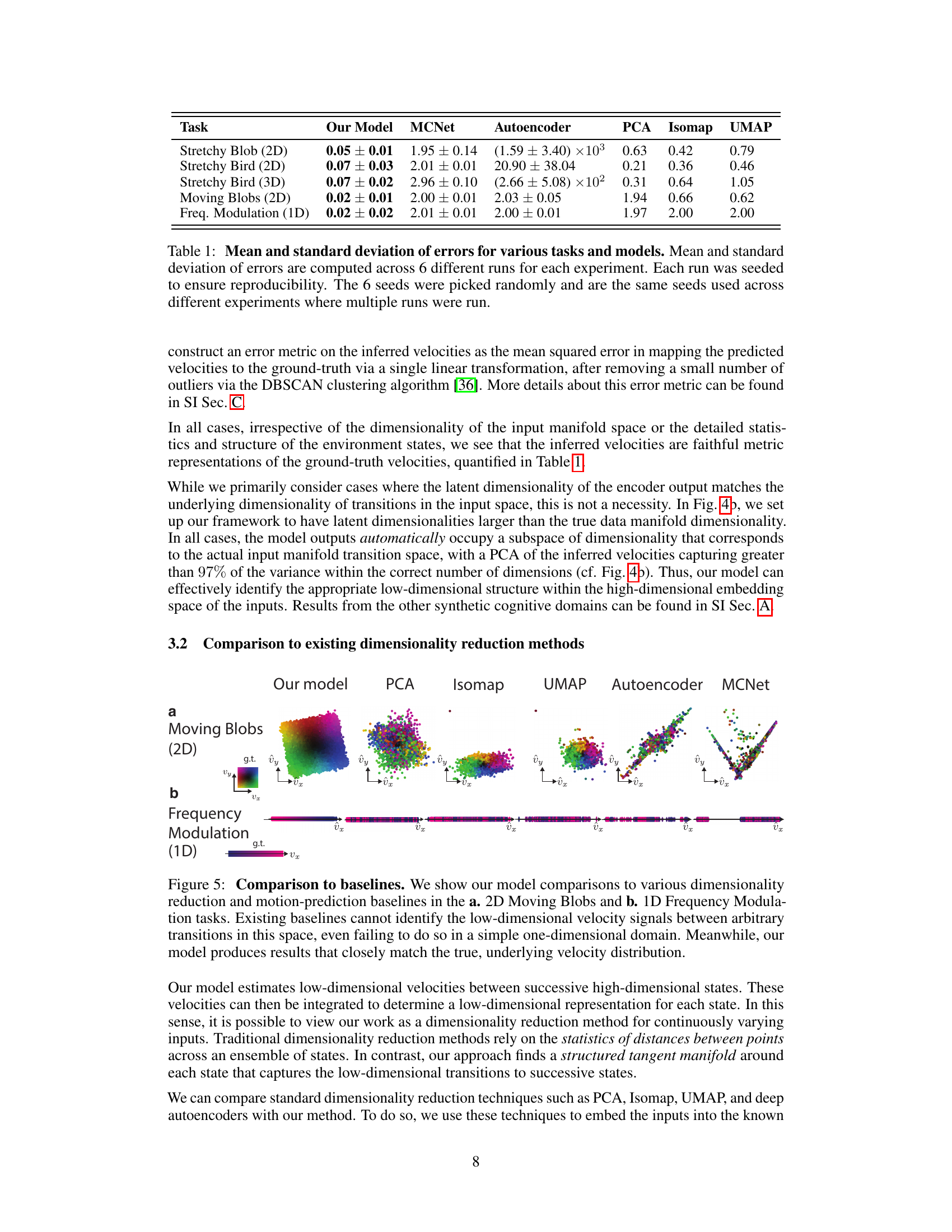

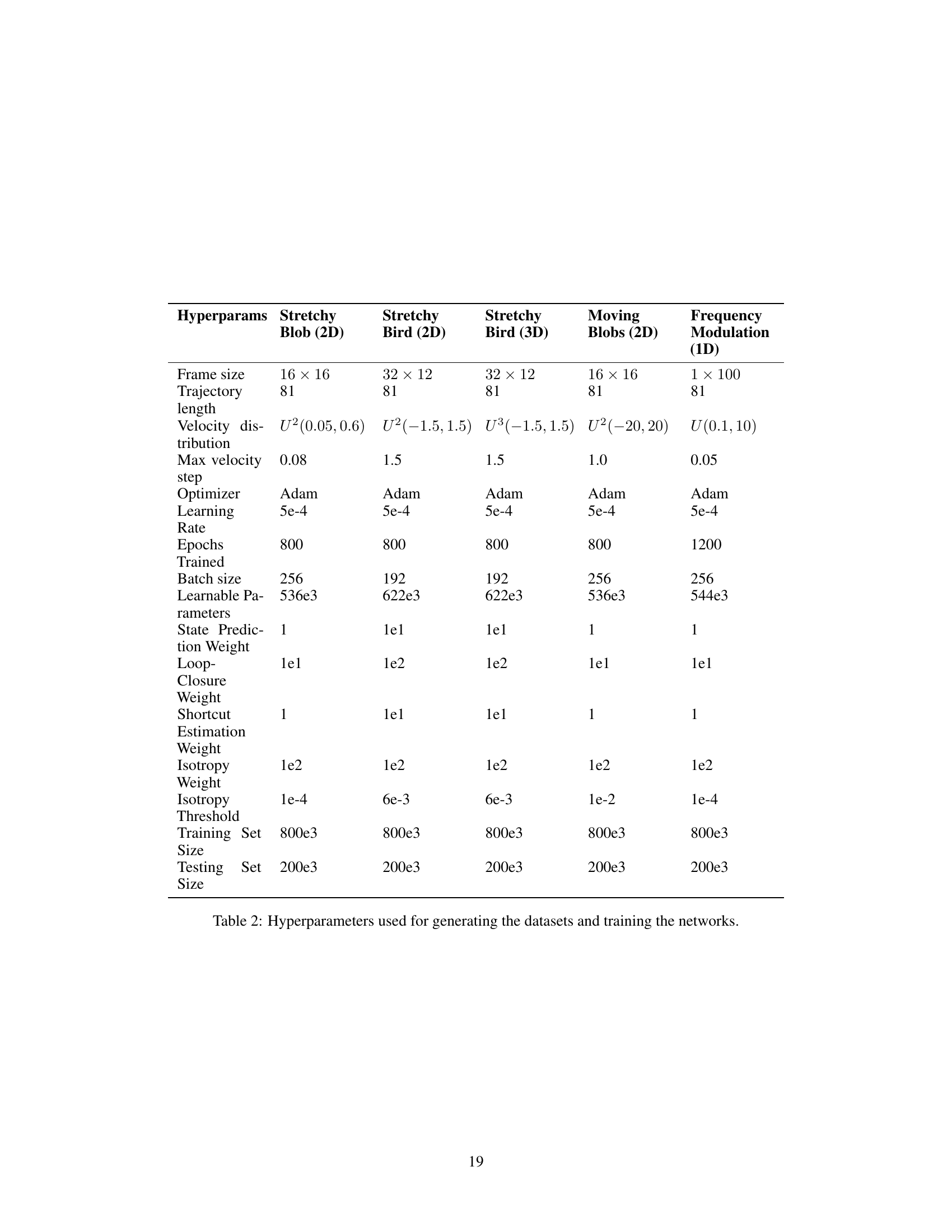

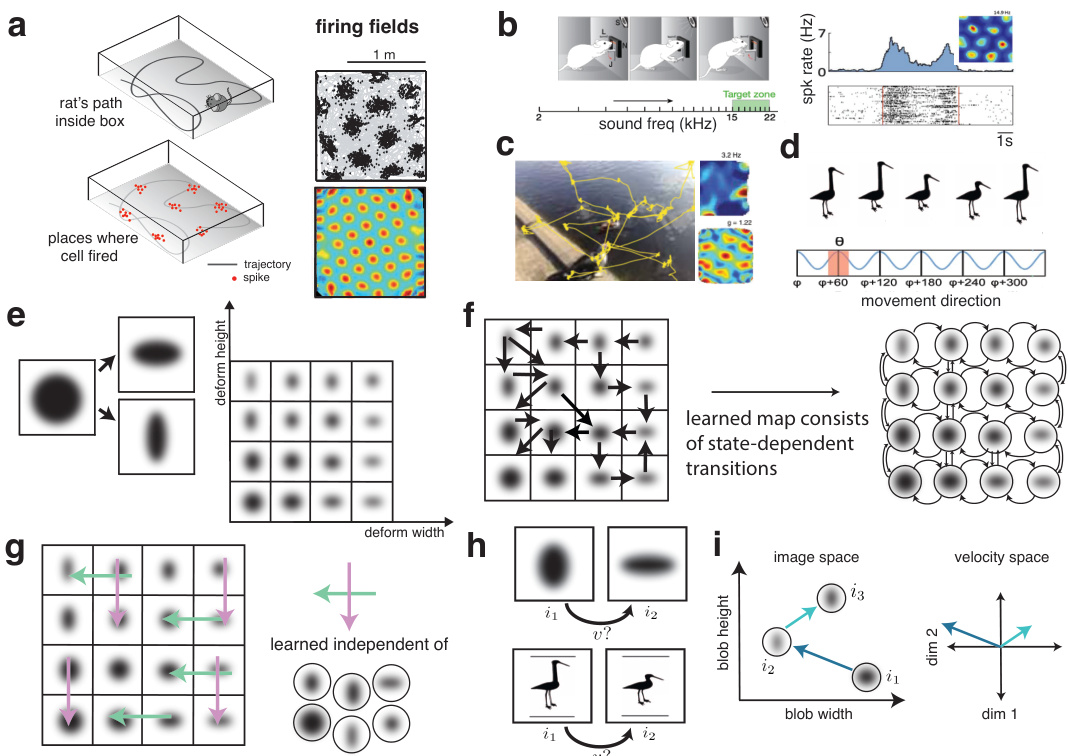

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of errors for various dimensionality reduction and motion extraction methods across five different cognitive tasks. The errors are calculated using a mean squared error metric that measures how well the model’s inferred velocities align with the ground truth velocities, following the application of a linear transformation. Each result is an average of six different runs with distinct random seeds, ensuring reproducibility across experiments.

In-depth insights#

Abstract Velocity#

The concept of ‘abstract velocity’ is crucial in understanding how the brain represents and navigates non-spatial domains. It suggests that the brain extracts low-dimensional representations of transitions between high-dimensional states, regardless of the specific nature of those states. This low-dimensional representation acts as a generalized ‘velocity’ signal, independent of the content of abstract domains. The self-supervised geometric consistency constraint, which requires the sum of displacements along closed-loop trajectories to be zero, is particularly interesting because it ensures the fidelity and self-consistency of these velocity estimates. Furthermore, this approach offers a computationally efficient solution by leveraging existing neural mechanisms (grid cells) and reusing their pre-structured states to encode transitions. The model’s success in outperforming traditional methods highlights the importance of extracting state-independent, low-dimensional velocity signals. It introduces a novel self-supervised learning framework and opens exciting avenues for transfer learning and efficient data utilization in various fields including robotics and machine learning. Ultimately, understanding abstract velocity is key to deciphering cognitive flexibility and the brain’s remarkable ability to generalize across vastly different domains.

Grid Cell Mapping#

Grid cell mapping is a fascinating area of neuroscience research, focusing on the brain’s ability to create spatial maps using grid cells. These cells, located in the medial entorhinal cortex, exhibit remarkable hexagonal firing patterns that allow for precise spatial navigation. The research explores how this inherent spatial mapping capacity of grid cells can be generalized to represent abstract, non-spatial domains. This generalization is crucial for understanding higher-level cognitive functions, as it suggests a flexible framework for encoding information beyond simple physical locations. Self-supervised learning models are playing a significant role in elucidating the mechanisms behind this flexible mapping. By leveraging the inherent spatial integration properties of grid cells, these models can extract consistent representations of movement across different abstract domains. This allows for the construction of abstract cognitive maps based on low-dimensional representations of velocity signals, enabling efficient navigation and organization of complex non-spatial information. The preservation of cell-cell relationships across domains suggests that abstract domains are mapped onto pre-existing grid cell representations, highlighting the remarkable flexibility and computational efficiency of the brain’s neural architecture. Future research should focus on the further development of these models and their implications for various fields.

SSL Framework#

A self-supervised learning (SSL) framework is proposed for flexible representation of abstract domains by grid cells. The core idea is to extract low-dimensional, content-independent velocity signals from high-dimensional abstract spaces. This is achieved through a neural network model that factors out domain-specific content from the displacement information, ensuring self-consistent velocity estimates. A crucial constraint is the geometric consistency of velocities along closed loops, mirroring the spatial velocity integration performed by the grid cell circuit. This framework not only explains the flexibility of grid cells in handling diverse abstract spaces but also surpasses traditional dimensionality reduction methods in accuracy. The framework is self-supervised, meaning it does not require labeled data for training, and generates a model that can be applied to various tasks without significant retraining. This aligns with the brain’s cognitive flexibility and provides a potential foundation for data-efficient generalization in machine learning.

Dimensionality Reduction#

The concept of dimensionality reduction is central to the paper, addressing the challenge of efficiently representing high-dimensional abstract cognitive spaces within the brain’s limited computational resources. The authors hypothesize that the brain doesn’t explicitly learn high-dimensional representations for each new domain, but instead leverages existing grid cell circuitry by extracting low-dimensional, self-consistent velocity signals. This approach sidesteps the computational cost of storing and processing high-dimensional state information for each encountered domain. The proposed neural network model explicitly factorizes the content of these domains from the underlying transitions, generating content-independent, low-dimensional velocity estimates. A key aspect is the self-supervised geometric constraint that forces displacements along closed loops to sum to zero, mimicking the integration performed by downstream grid cell circuitry. Importantly, this method outperforms traditional dimensionality reduction techniques, demonstrating superior performance in learning faithful, low-dimensional representations of velocity in abstract spaces. The resulting low-dimensional velocity representations provide a framework to map diverse abstract spaces onto a common grid cell manifold, enabling flexible and efficient reuse of existing neural resources for representing novel domains. This innovative approach highlights the brain’s sophisticated strategies for managing high-dimensionality, offering valuable insights for transfer learning and data-efficient generalization in AI.

Cognitive Flexibility#

Cognitive flexibility, the ability to switch between tasks or mental sets, is a crucial aspect of higher-level cognition. The research paper explores this concept through the lens of grid cells, suggesting a mechanism by which the brain can flexibly map different abstract domains onto a common representational space. This is achieved by extracting low-dimensional velocity signals that represent transitions within these abstract spaces, regardless of their specific content. The system leverages self-supervised learning, requiring only that closed-loop trajectories sum to zero. This framework then uses grid cells, capable of continuous attractor dynamics, for efficient navigation and map generation in high-dimensional abstract spaces. The model exhibits superior performance compared to traditional dimensionality reduction and deep learning methods, highlighting a novel method for achieving data-efficient generalization. The self-consistent nature of velocity representation is key to this flexibility, ensuring consistent mapping across varied domains and showcasing a novel approach to understand cognitive flexibility in neural terms. The key is the efficient reuse of existing neural structures (grid cells) rather than the creation of new representations for each new task, showcasing an elegant solution to a complex problem.

More visual insights#

More on figures

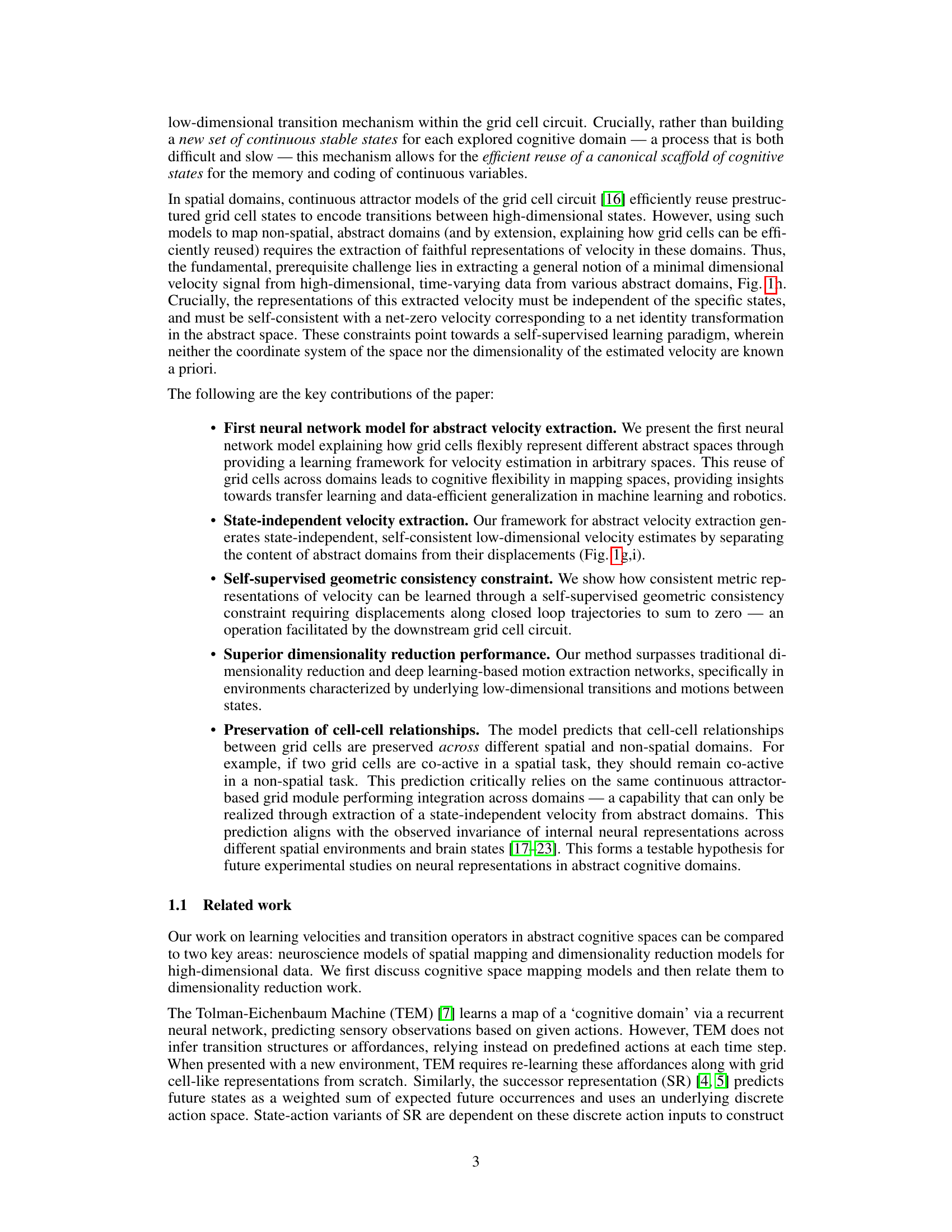

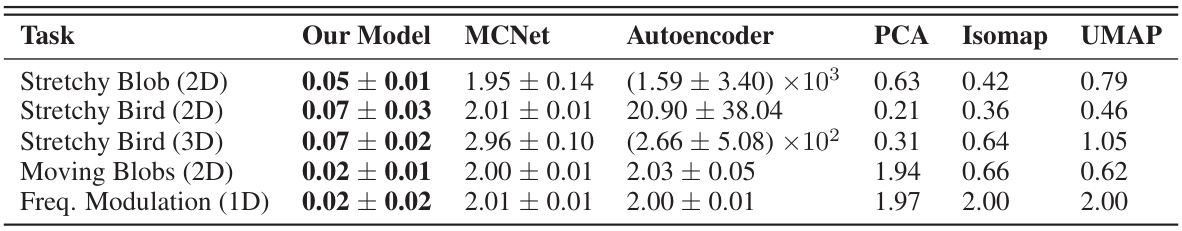

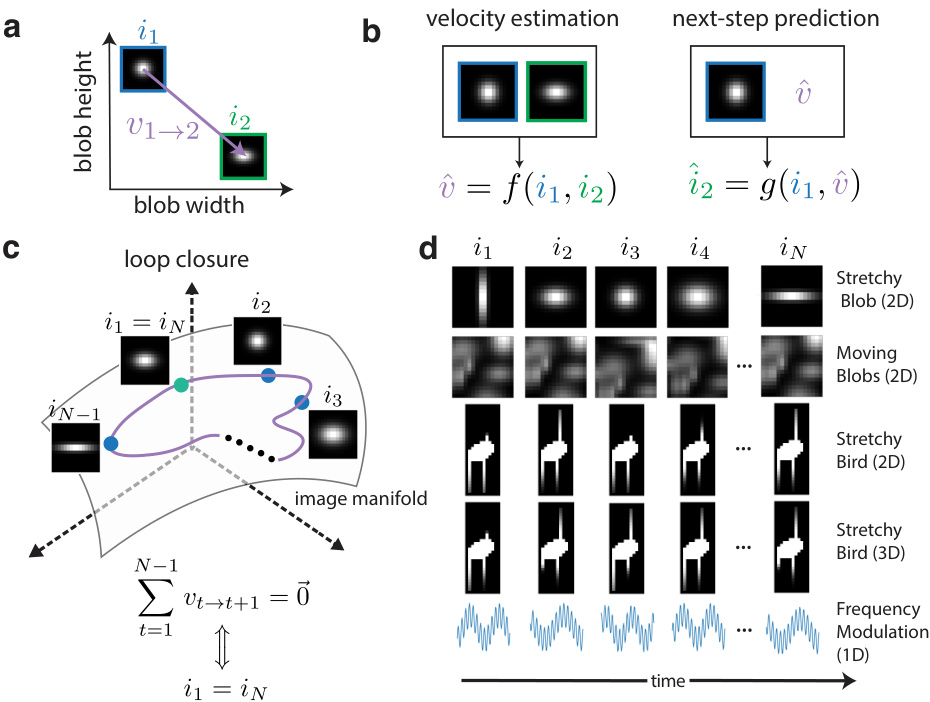

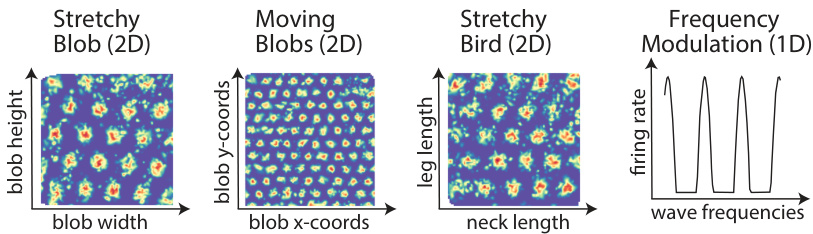

This figure illustrates the core concepts and tasks used in the paper’s proposed model. Panel (a) shows a simple example of a transition in the 2D Stretchy Blob abstract space. Panel (b) defines the core problem: learning a function (f) to estimate velocity from two consecutive images and another function (g) to predict the next image using the estimated velocity. Panel (c) introduces the ‘loop closure’ constraint, essential for self-supervised learning. Finally, panel (d) shows the five different abstract cognitive domains used to evaluate the model.

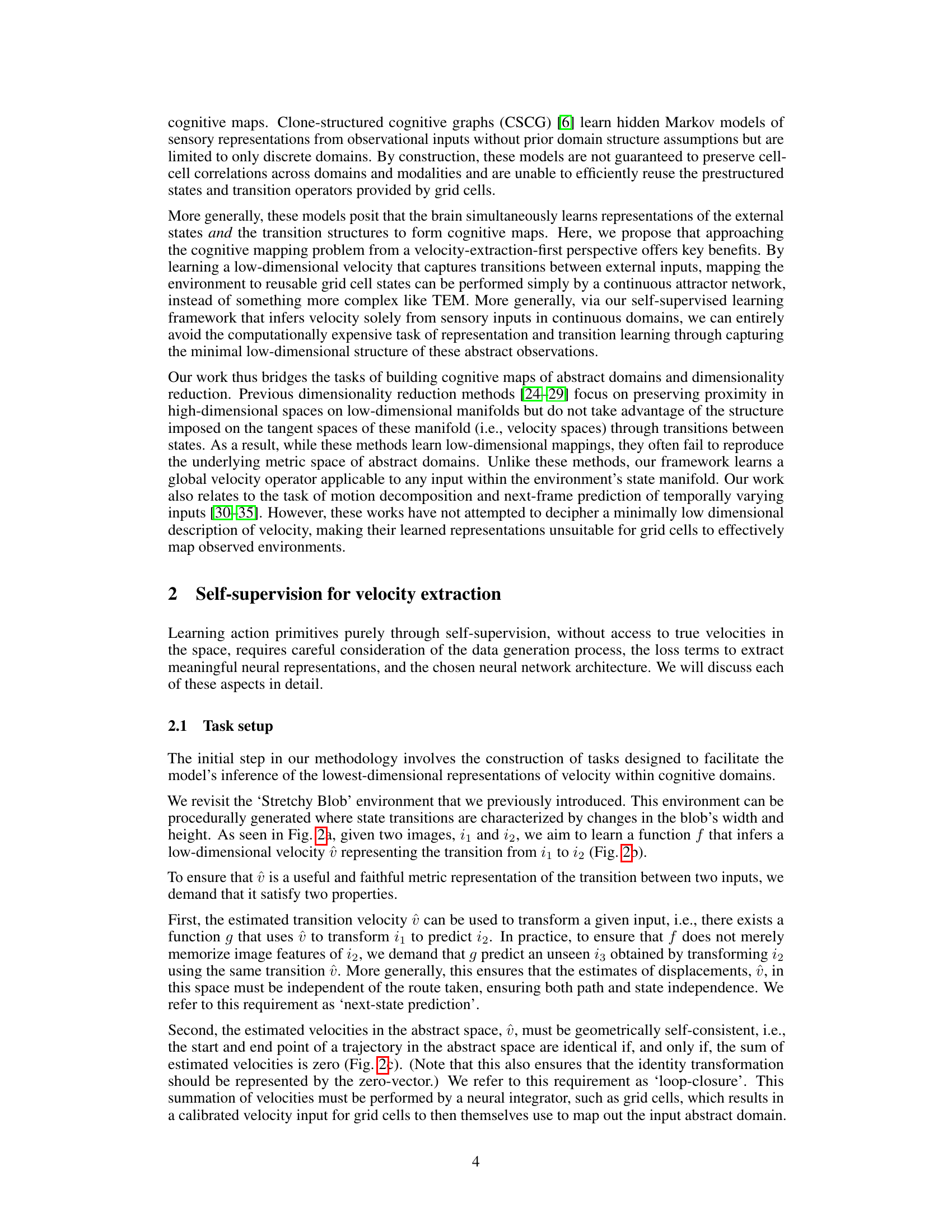

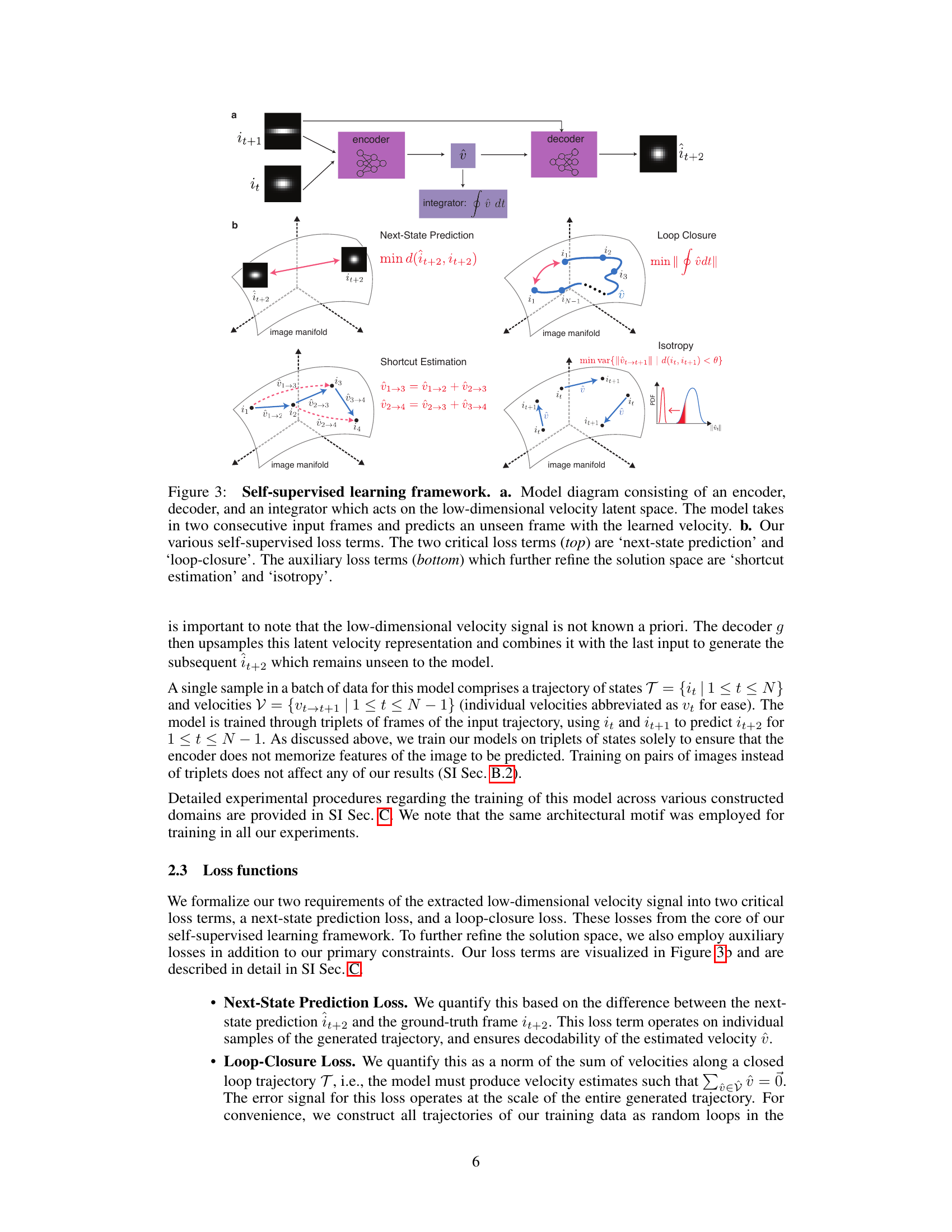

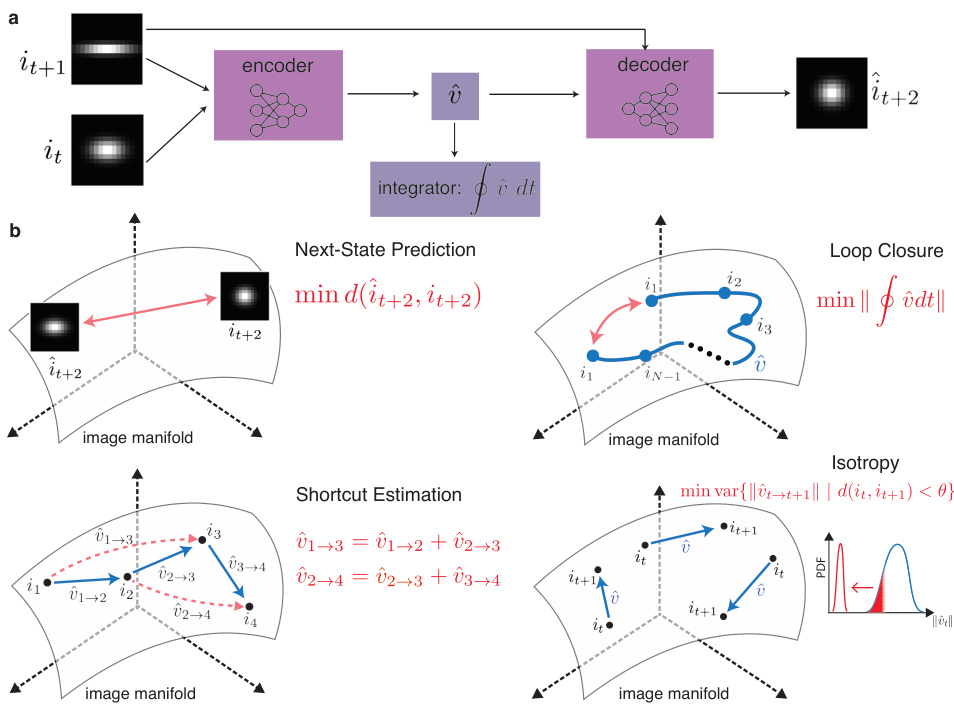

This figure illustrates the self-supervised learning framework proposed in the paper. Panel (a) shows the architecture of the model, which consists of an encoder, a decoder, and an integrator. The encoder takes two consecutive input frames and outputs a low-dimensional velocity representation. The decoder takes the velocity and the previous frame as input and predicts the next frame. The integrator sums up the velocities to enforce the loop closure constraint. Panel (b) details the different loss functions used to train the model, including next-state prediction, loop closure, shortcut estimation, and isotropy losses. These losses ensure that the model learns a consistent and faithful representation of velocity in abstract cognitive domains.

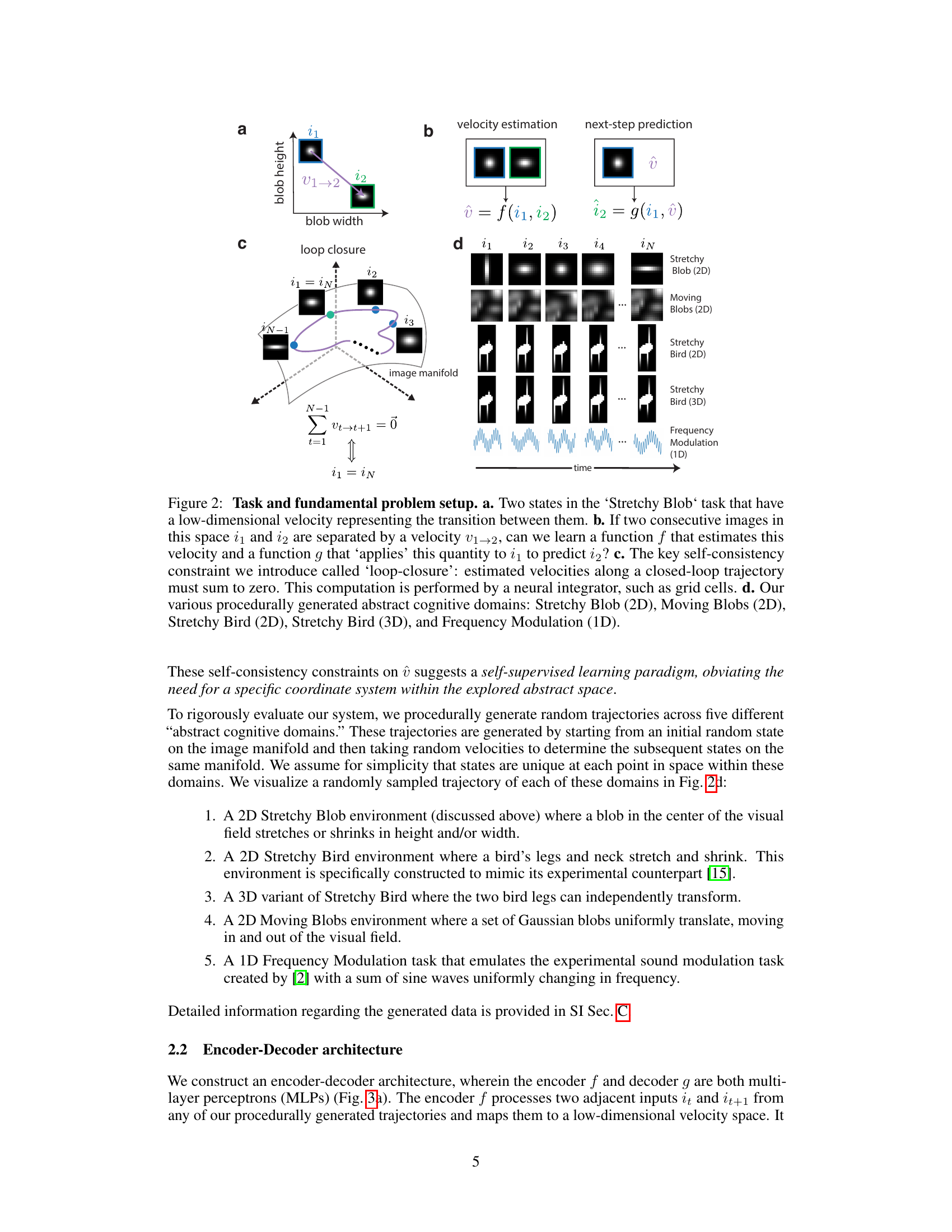

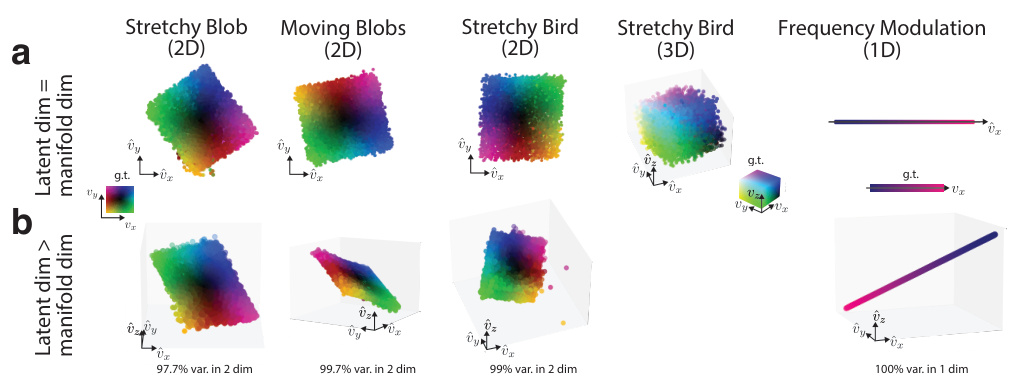

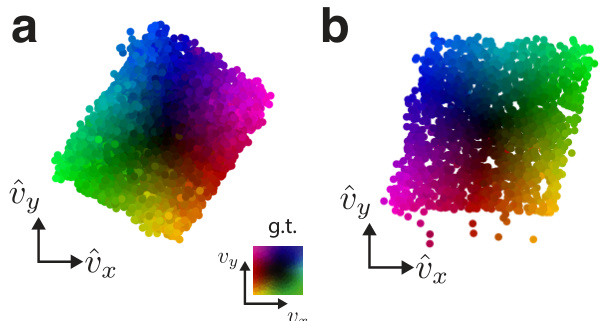

This figure displays the results of the model’s performance on various abstract cognitive tasks. Panel (a) shows that the model accurately infers low-dimensional velocity representations that align well with the ground truth, even without prior knowledge of the underlying distribution. Panel (b) demonstrates the model’s robustness: even when given a higher-dimensional latent space than the intrinsic dimensionality of the task, the model still effectively extracts the minimal, essential dimensions of the velocity.

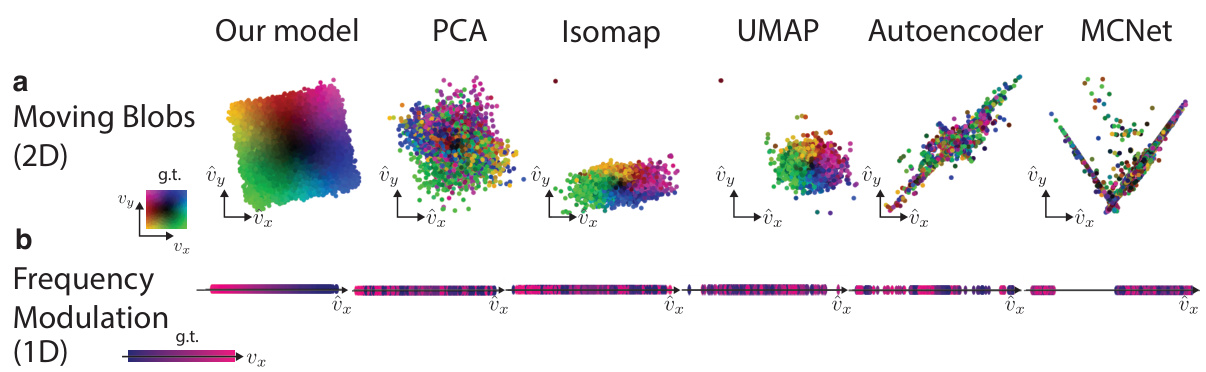

This figure compares the performance of the proposed model against several baselines for dimensionality reduction and motion prediction on two tasks: 2D Moving Blobs and 1D Frequency Modulation. It demonstrates that existing methods struggle to identify low-dimensional velocity representations in these tasks, while the proposed model accurately recovers the underlying low-dimensional velocity distribution.

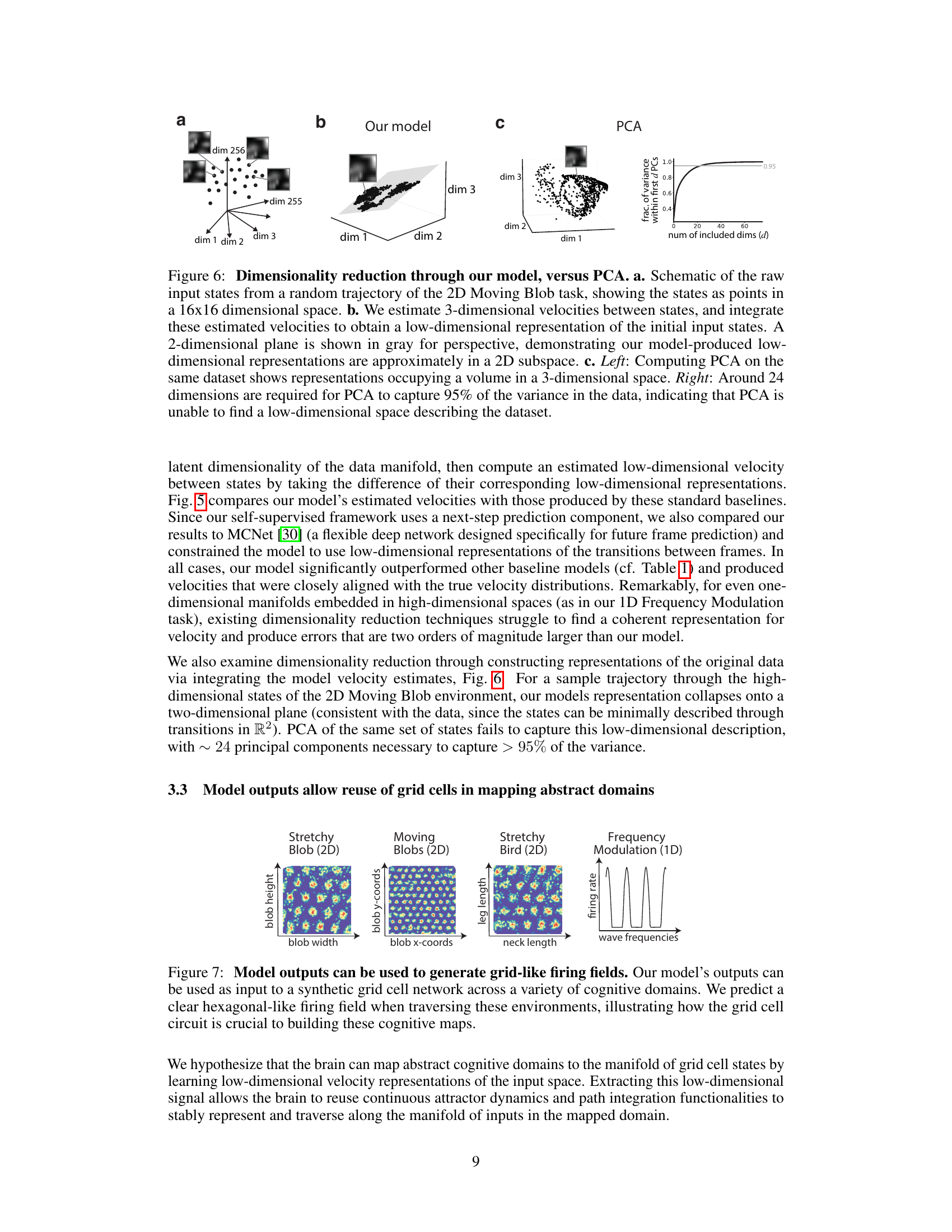

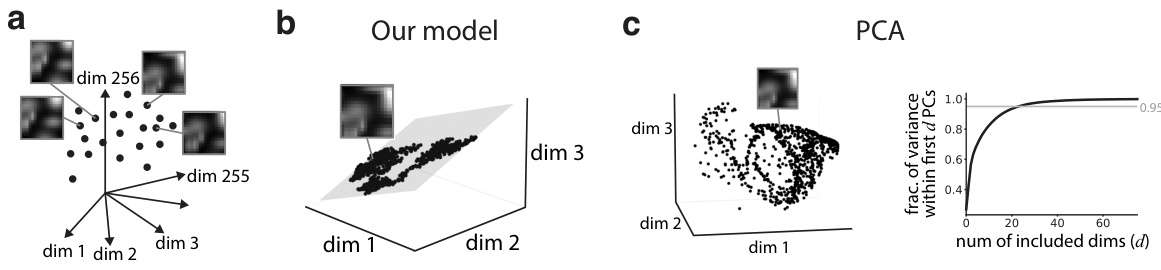

This figure compares the dimensionality reduction performance of the proposed model against Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Panel (a) shows high-dimensional input states as points in a 16x16 dimensional space. Panel (b) demonstrates how the model estimates 3D velocities between these states, integrating them to produce a low-dimensional (approximately 2D) representation. In contrast, Panel (c) shows that PCA requires many dimensions (around 24) to capture 95% of the variance, highlighting the model’s superior ability to find a low-dimensional structure in high-dimensional data.

This figure illustrates the task setup and fundamental problems addressed in the paper. It shows how a low-dimensional velocity can represent the transition between two states in an abstract cognitive domain. It also highlights the self-consistency constraint (’loop-closure’) for efficient map generation and introduces several procedurally generated abstract cognitive domains used in the experiments.

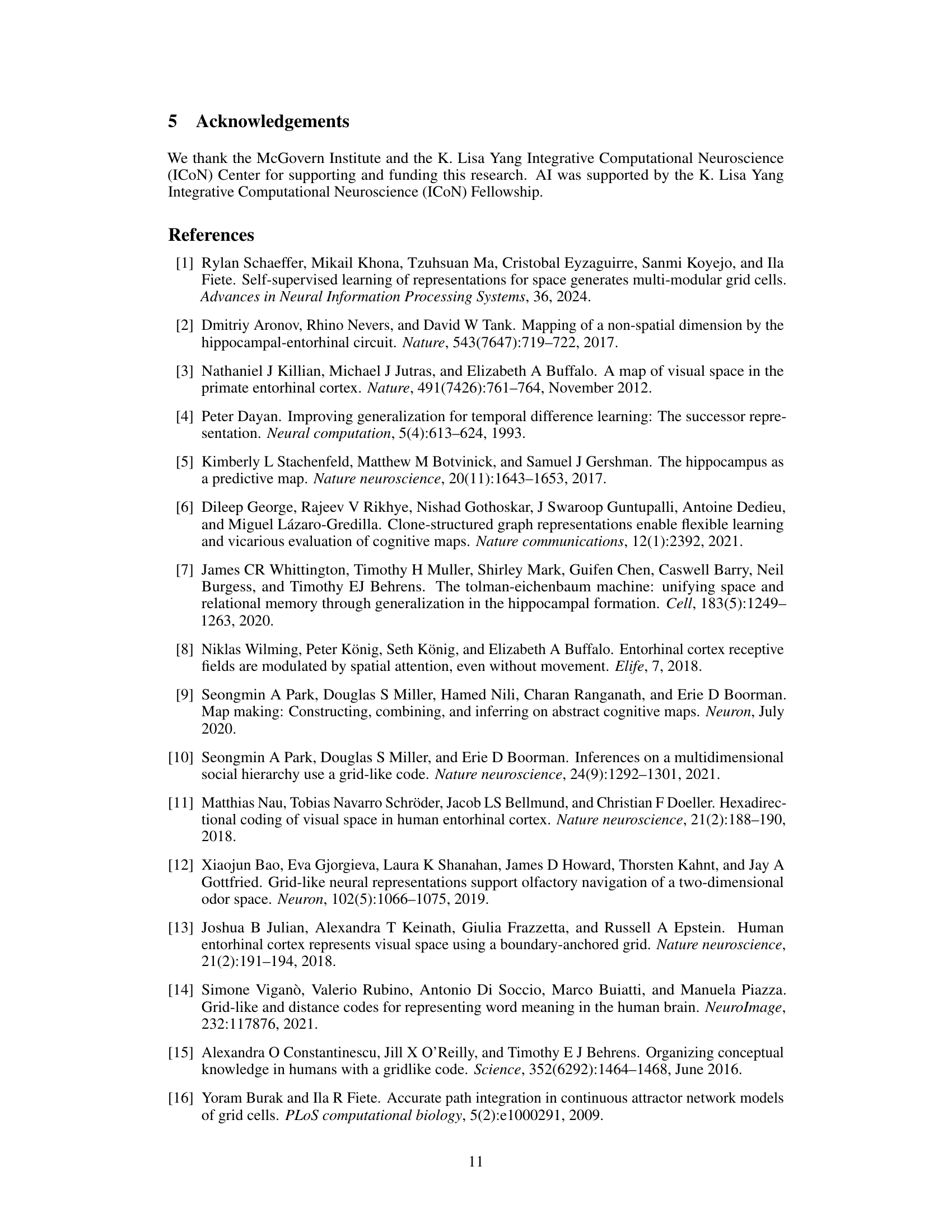

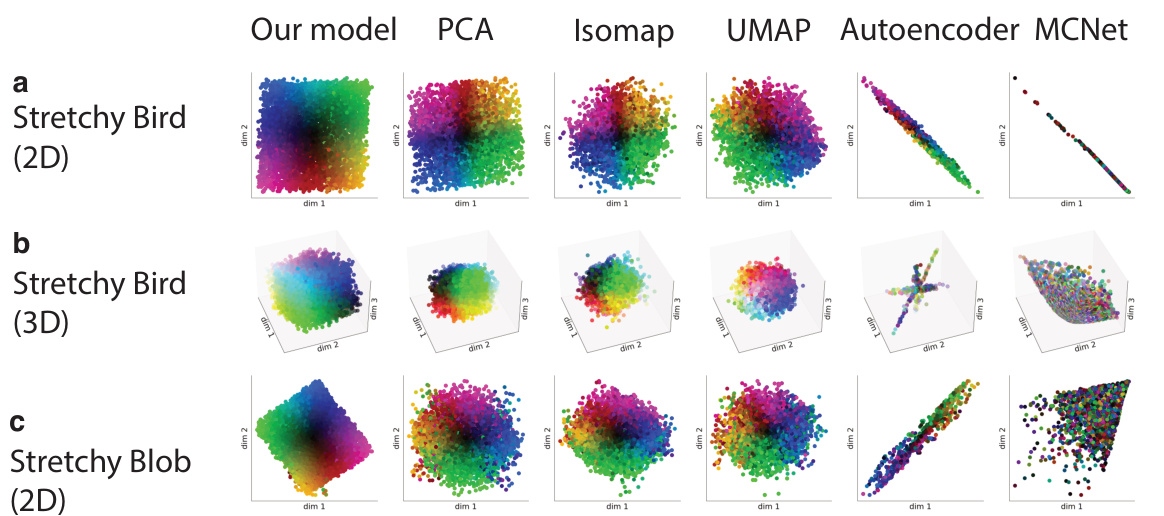

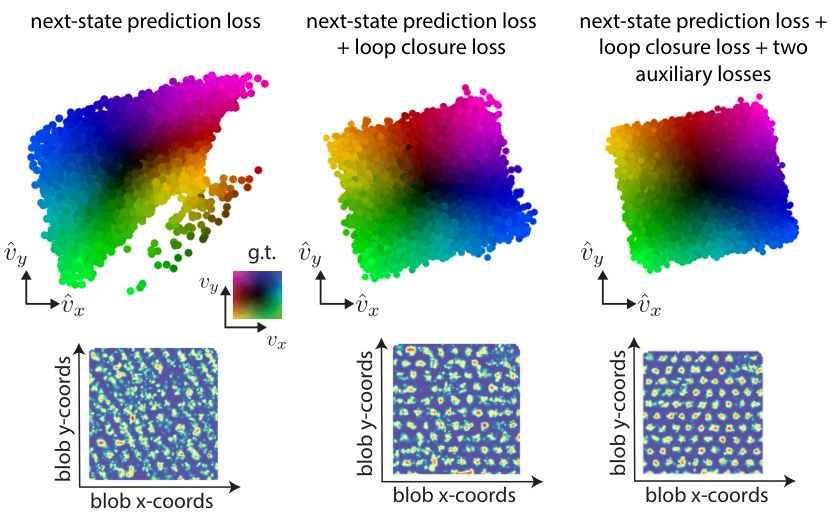

This figure compares the performance of the proposed model against several baseline dimensionality reduction and motion extraction methods across three different abstract cognitive domains. Panels (a), (b), and (c) show the inferred velocity spaces generated by the proposed model and the baselines for the 2D Stretchy Bird, 3D Stretchy Bird, and 2D Stretchy Blob domains, respectively. The color coding represents the underlying trajectory in each domain. The goal is to demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed model in accurately capturing the low-dimensional velocity structure underlying transitions within these complex high-dimensional domains.

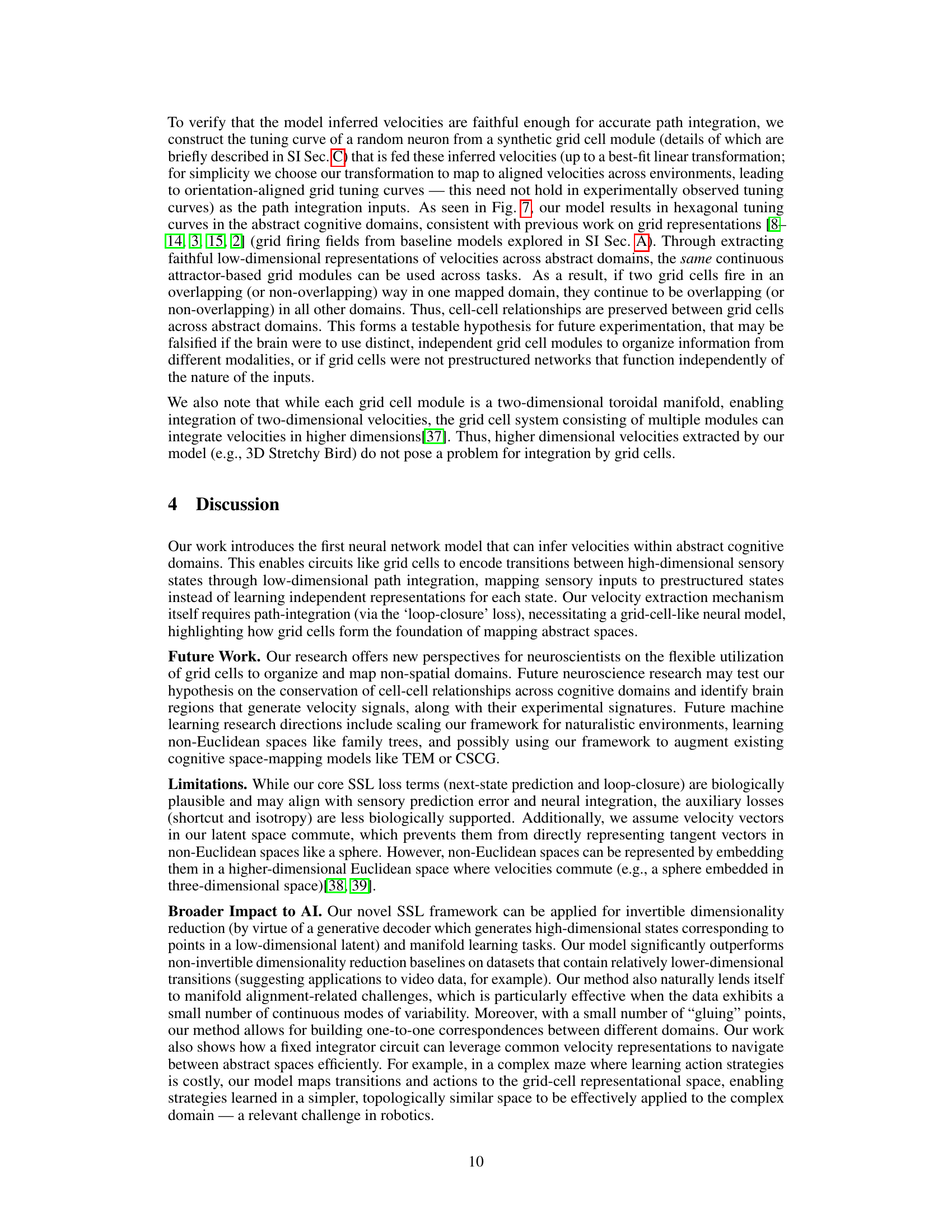

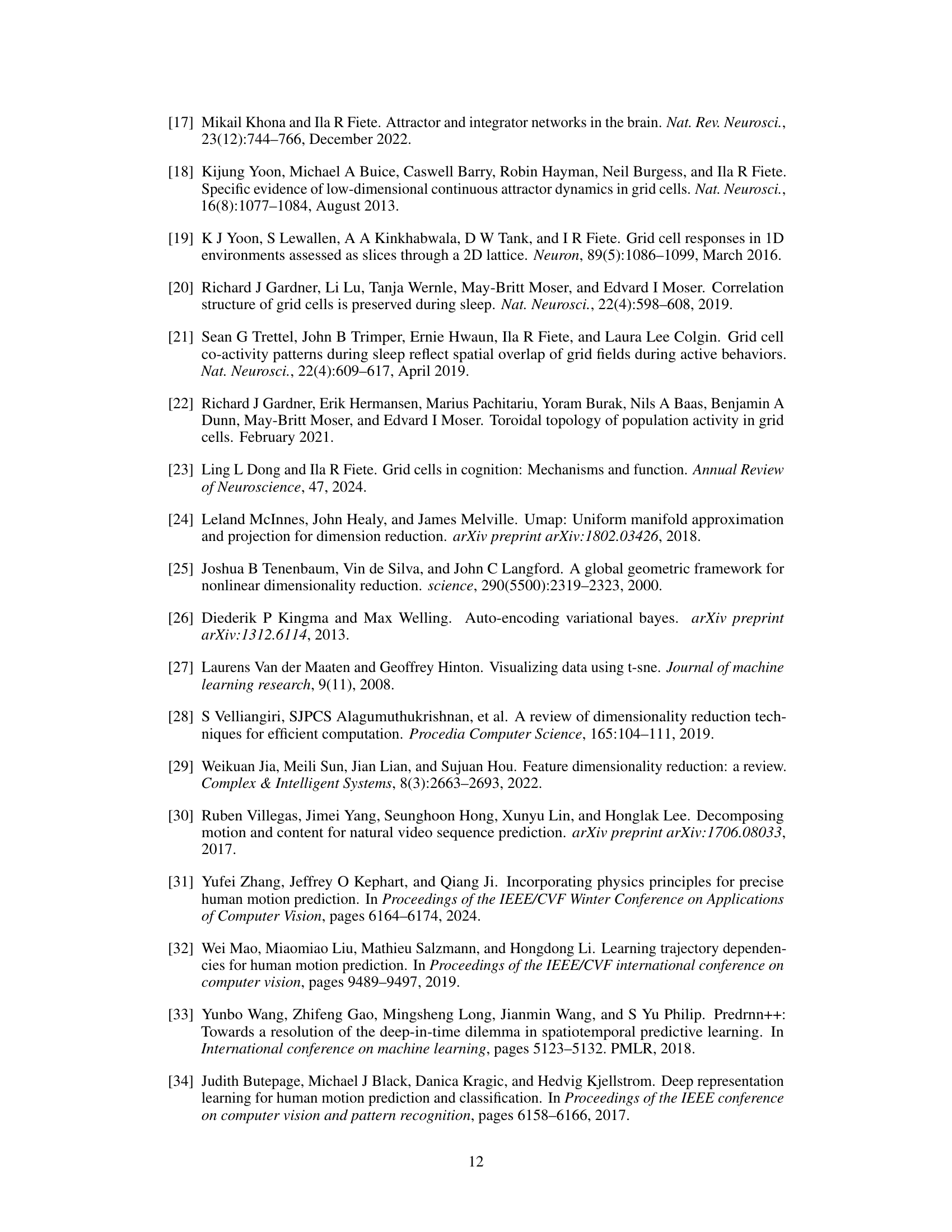

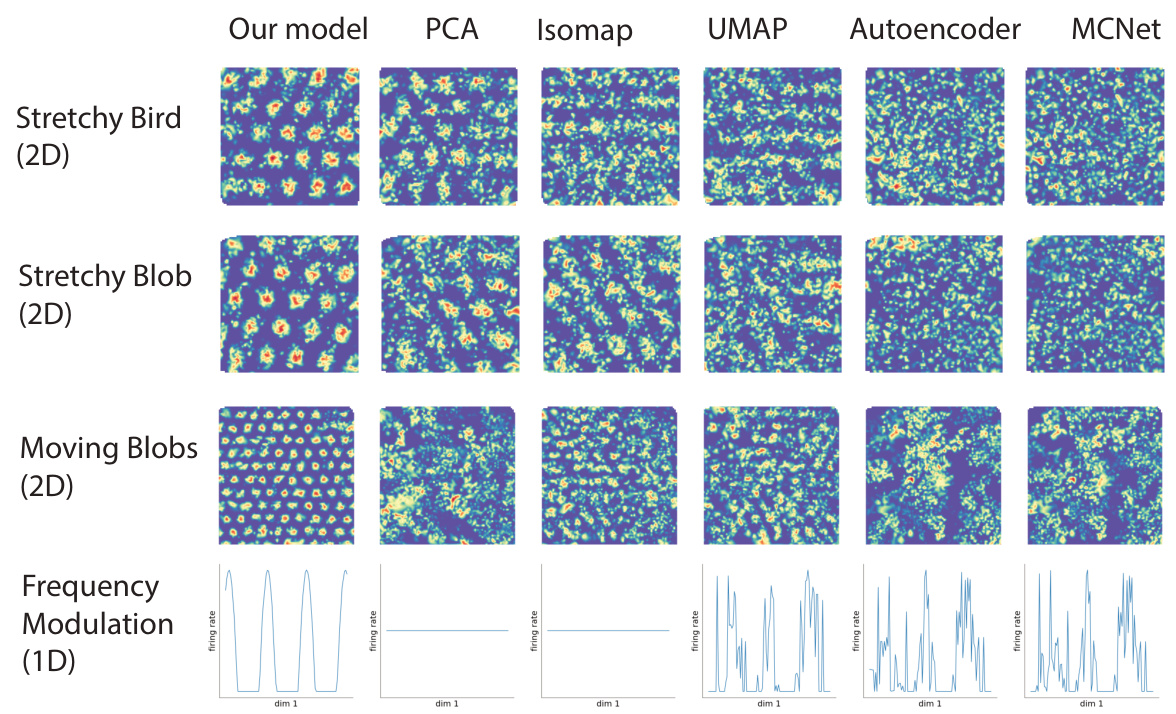

This figure compares the results of different dimensionality reduction methods, including the authors’ proposed model, in generating grid-like firing fields. The model’s outputs were used as inputs to a synthetic grid cell network. The figure visually demonstrates that the authors’ model performs better at producing hexagonal patterns characteristic of grid cells compared to traditional methods like PCA, Isomap, UMAP, autoencoder, and MCNet. This showcases the superior ability of their method to extract a low-dimensional representation of velocity that is suitable for grid cell integration across diverse tasks and environments.

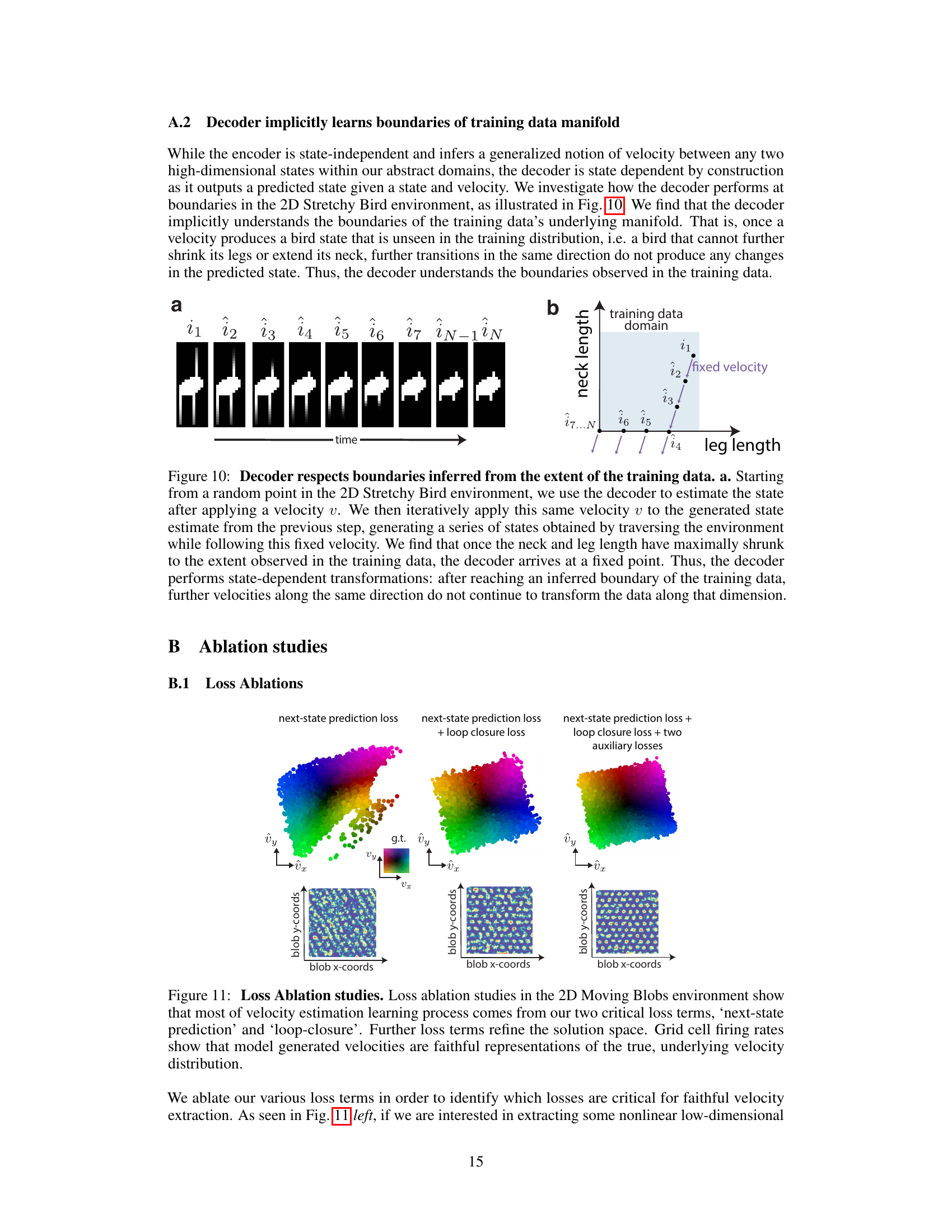

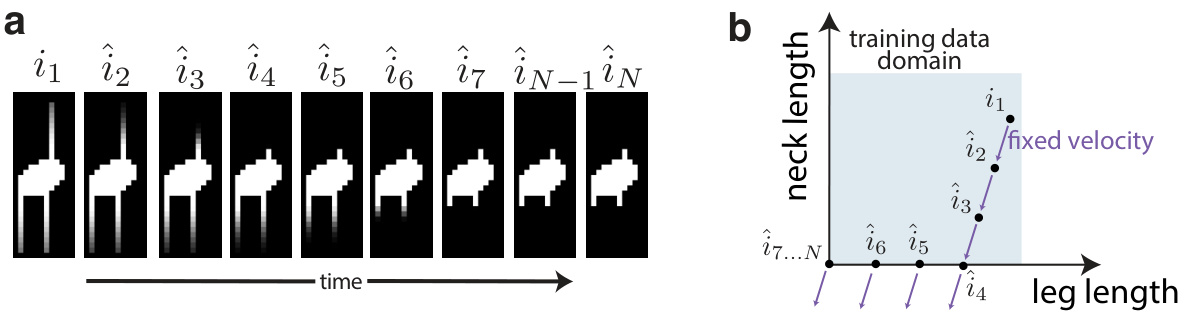

This figure shows that the decoder in the model implicitly learns the boundaries of the training data manifold. When given a velocity that would push the state outside the observed range of the training data (in this case, a bird with extreme neck and leg lengths), the decoder stops generating further changes in the state, effectively respecting the boundaries of the training data.

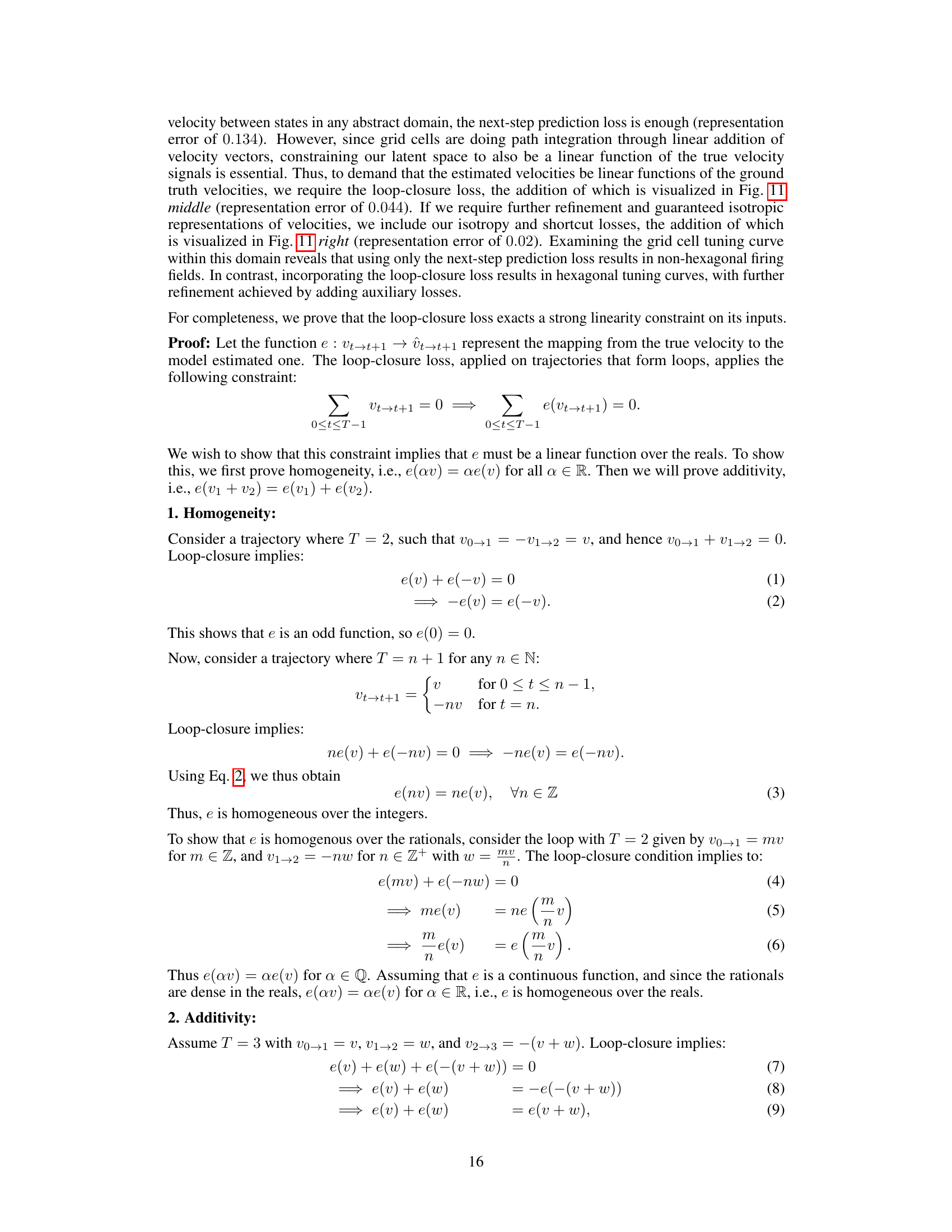

This figure presents the ablation study on the loss functions. It shows that the next-state prediction loss and loop closure loss are the most critical for accurate velocity extraction. Adding two auxiliary losses (shortcut and isotropy) further refines the solution and produces more faithful representations of the true, underlying velocity distribution, which is demonstrated using the grid cell firing rates.

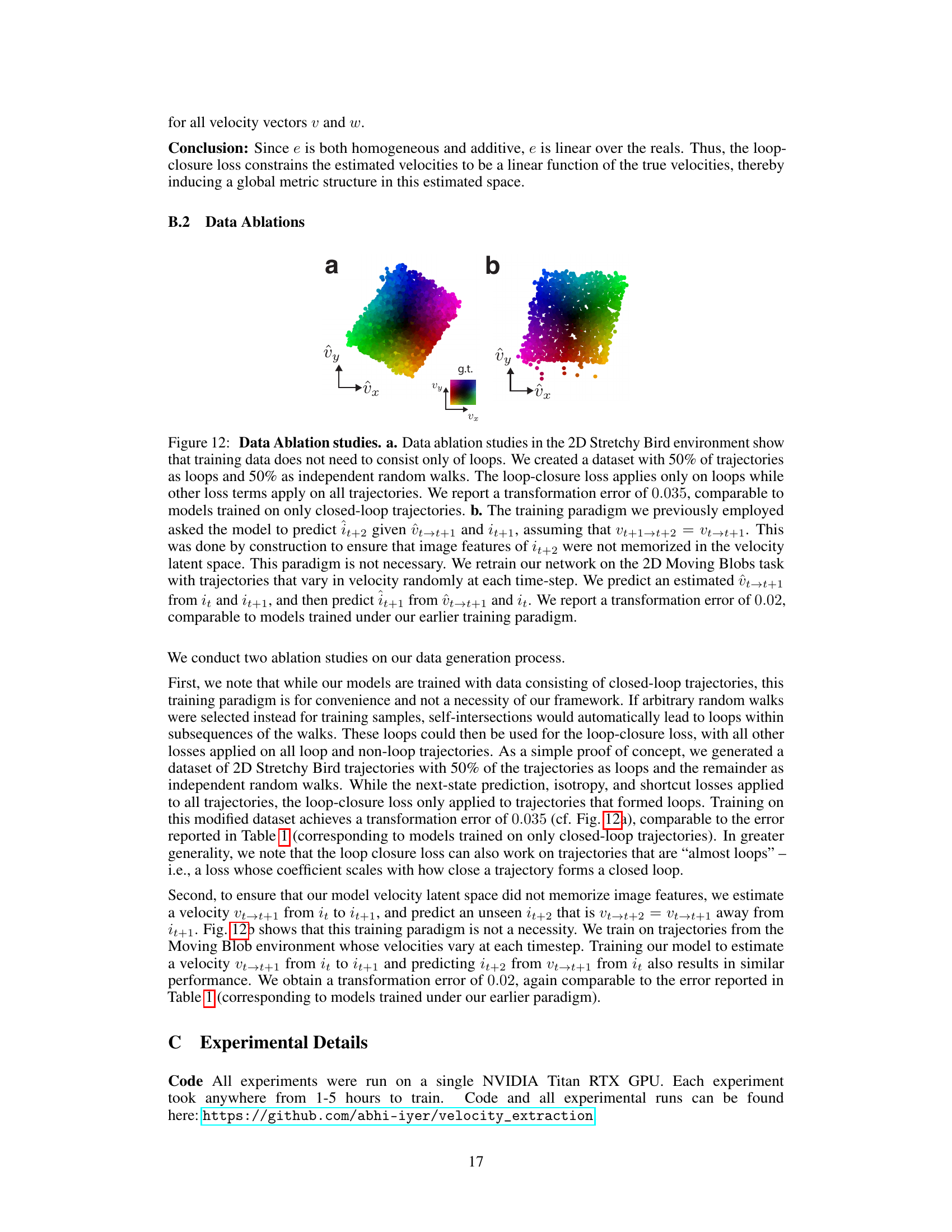

This figure compares the dimensionality reduction performance of the proposed model against PCA. Panel (a) shows high-dimensional data points from a trajectory. Panel (b) demonstrates that the model effectively reduces these to a low-dimensional representation (approximately 2D in this case), while panel (c) shows that PCA requires significantly more dimensions to capture a similar amount of variance, highlighting the model’s superior dimensionality reduction capabilities.

Full paper#