TL;DR#

Differential privacy (DP) adds noise to training data to protect privacy, but this reduces model accuracy. The standard approach sets a privacy budget (epsilon) which is then translated into an operational attack risk. This is overly conservative, leading to excessive noise and reduced utility.

This work proposes directly calibrating noise to a desired attack risk (e.g., accuracy, sensitivity, specificity of inference attacks), thereby avoiding the indirect and overly-cautious epsilon-based approach. The proposed methods significantly decrease noise scale, improving model accuracy while maintaining equivalent privacy guarantees. Empirical results show substantial utility improvements across various models and datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is vital for improving the utility of privacy-preserving machine learning without compromising privacy. It offers a novel calibration method, enhancing the interpretability and practical application of differential privacy. This is crucial given the increasing use of sensitive data in ML and growing concerns about privacy.

Visual Insights#

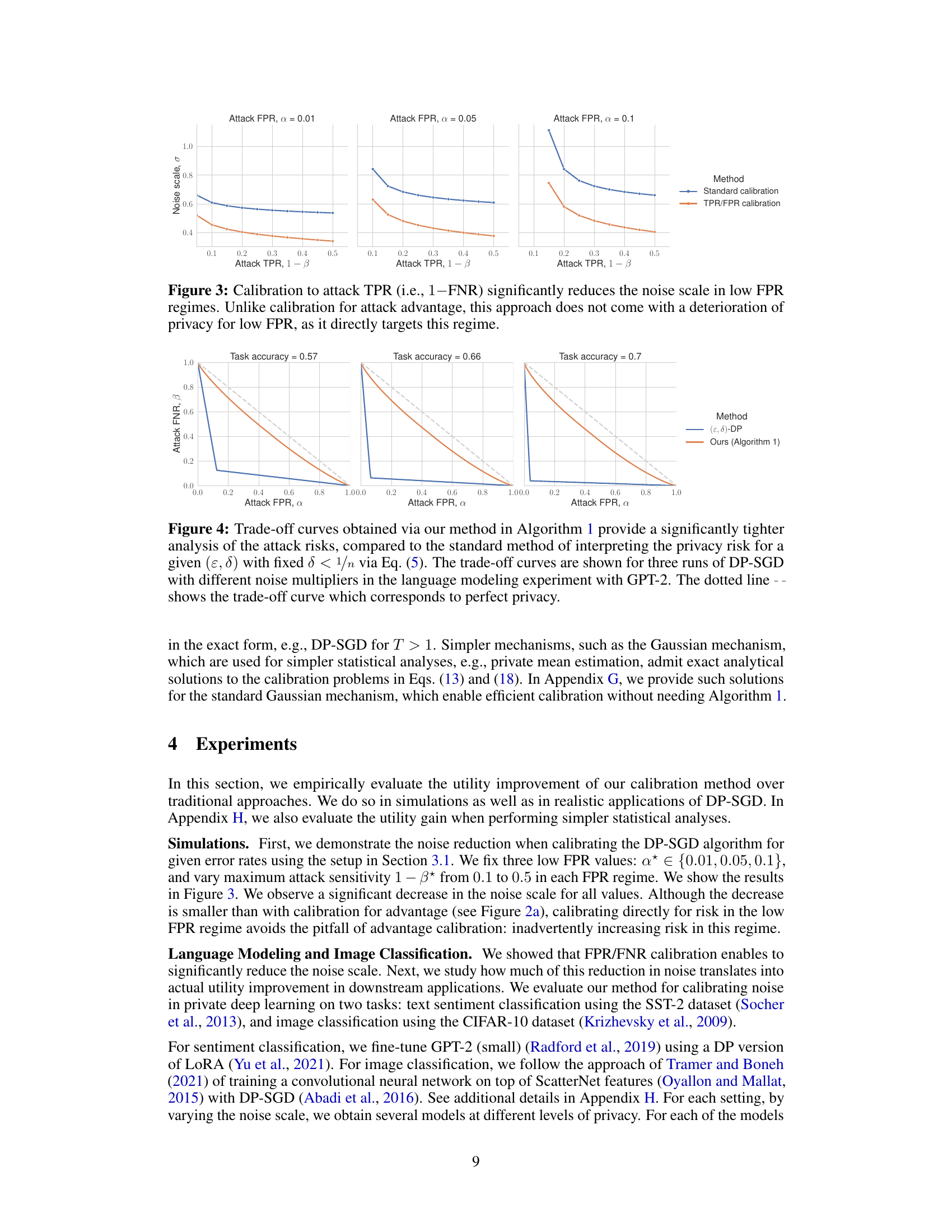

🔼 This figure compares the test accuracy of two different machine learning models (GPT-2 for text sentiment classification and CNN for image classification) trained with two different noise calibration methods: standard calibration and attack risk calibration. The x-axis represents the task accuracy achieved by the model, and the y-axis represents the attack risk (sensitivity). Three different false positive rates (α) are shown. The figure demonstrates that directly calibrating noise to attack risk (our method) leads to higher accuracy compared to standard calibration for the same level of risk.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test accuracy (x-axis) of a privately finetuned GPT-2 on SST-2 text sentiment classification dataset (top) and a convolutional neural network on CIFAR-10 image classification dataset (bottom). The DP noise is calibrated to guarantee at most a certain level of privacy attack sensitivity (y-axis) at three possible attack false-positive rates α ∈ {0.01, 0.05, 0.1}. See Section 4 for details.

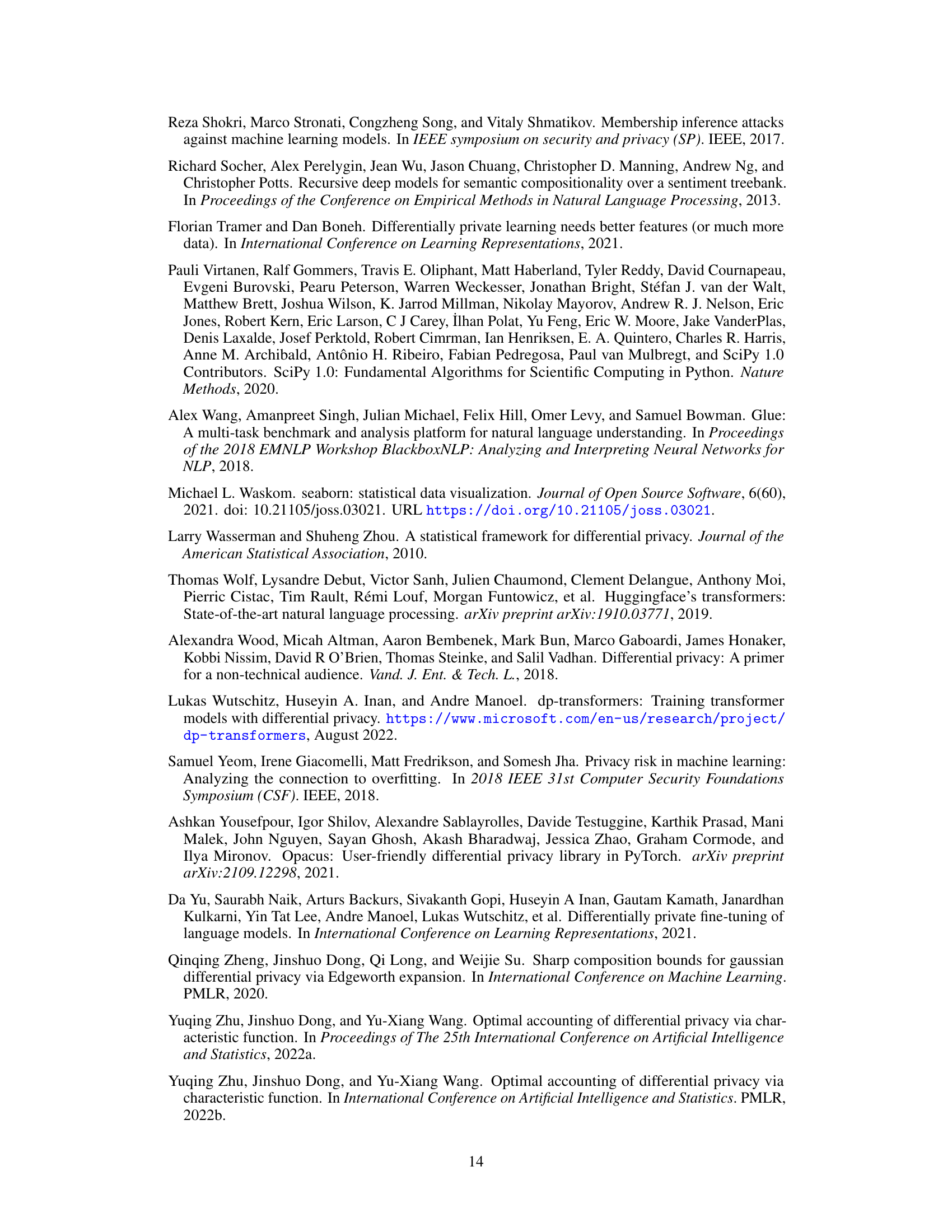

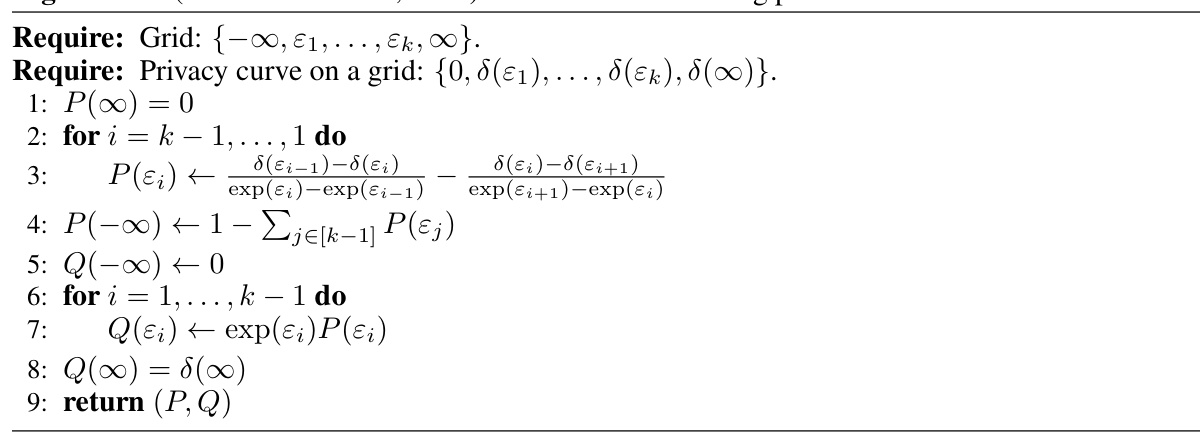

🔼 This table summarizes the notations used throughout the paper. It defines symbols for data records, datasets, neighboring dataset relationships, privacy-preserving mechanisms, noise parameters, the hockey-stick divergence, differential privacy parameters, privacy profile curves, membership inference hypothesis tests, false positive and negative rates, attack advantage, trade-off curves, and dominating pairs and privacy loss random variables.

read the caption

Table 1: Notation summary

In-depth insights#

Attack-Aware DP#

Attack-aware differential privacy (DP) represents a significant advancement in privacy-preserving machine learning. Traditional DP focuses on satisfying a pre-defined privacy budget (ε, δ), often leading to overly cautious noise addition and reduced model utility. Attack-aware DP directly calibrates the noise mechanism to a desired level of attack risk, such as the sensitivity or specificity of membership inference attacks, rather than an abstract privacy parameter. This approach offers substantial improvements in model accuracy without sacrificing privacy guarantees. The key innovation lies in its direct focus on interpretable and operationally meaningful metrics, bypassing the intermediate step of translating a privacy budget into attack risk, which frequently results in overly conservative risk assessments. The methodology allows practitioners to directly manage the level of risk that is acceptable to both regulators and data subjects, resulting in more effective and practical privacy-preserving machine learning models.

Noise Calibration#

The concept of noise calibration in differential privacy is crucial for balancing privacy and utility. The core idea revolves around carefully determining the amount of noise added to a dataset during training to prevent information leakage while preserving the model’s accuracy. The paper explores different calibration methods, shifting from the traditional approach of setting a privacy budget (ε, δ) to a more direct calibration based on attack risk. This direct approach offers the potential to significantly reduce the noise level, leading to improved model utility without compromising privacy. Attack risk, in this context, can be measured in several ways such as the accuracy of membership inference attacks or true/false positive rates, and is a more intuitive metric than the privacy budget for practitioners. The paper further highlights the importance of considering specific attack risk types, like sensitivity and specificity, as focusing solely on overall attack accuracy can lead to a decrease in robustness to certain attacks. The proposed methods aim to provide more principled and practical ways for applying differential privacy in machine learning, leading to improved tradeoffs between privacy and utility.

f-DP Risk Analysis#

Analyzing privacy through the lens of f-DP offers a more nuanced perspective than traditional (ε, δ)-DP. f-DP directly connects the privacy parameters to the operational risks of attacks, such as membership inference, providing a more tangible measure of privacy. Instead of relying on abstract privacy guarantees, f-DP allows researchers to quantify the trade-off between privacy and utility based on the probability of successful attacks, giving a more interpretable measure for non-technical audiences. A key advantage of f-DP is its ability to directly link the noise calibration to the desired attack risk level, bypassing the less intuitive step of calibrating noise solely to satisfy a privacy budget. This direct approach is crucial for improving the utility of privacy-preserving machine learning models while maintaining an acceptable level of risk. However, a thorough analysis of f-DP should include an evaluation of its behavior across various attack models and practical considerations, such as computational cost and the handling of compositions of multiple mechanisms. Furthermore, understanding the implications of various risk metrics, like true positive and false positive rates, is essential to ensure the calibration aligns with the desired security posture. This holistic understanding allows for a more informed, and safer, design of privacy-preserving systems.

Empirical Results#

The Empirical Results section of a research paper should present a robust evaluation of the proposed methods. It’s crucial to show clear evidence supporting the claims made in the abstract and introduction. This involves presenting quantitative metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, or AUC, along with appropriate statistical significance tests (e.g., p-values, confidence intervals). It is important to compare the performance of the proposed method to existing baselines to demonstrate its relative strengths and weaknesses. The experimental setup needs to be clearly detailed, including datasets used, hyperparameters, evaluation protocols and any pre-processing steps. The results should be presented in a clear and accessible manner, often using tables and graphs to facilitate understanding. Transparency is key, and any limitations of the experiments or potential biases should be acknowledged. A strong Empirical Results section builds trust in the validity and generalizability of the research findings, helping readers to confidently evaluate the contribution of the work.

Future Work#

The paper’s discussion on future work is insightful, highlighting several promising research avenues. Improving the methods for choosing target FPR/FNR values is crucial, as the current approach relies on somewhat arbitrary thresholds. This requires further investigation into how to align these choices with legal and practical constraints. The concept of catastrophic failures in DP mechanisms needs more attention. The authors correctly note that some mechanisms can exhibit complete loss of privacy under certain conditions, and developing more robust methods to prevent this is essential. Exploring how their methods could extend beyond privacy and generalization, for instance, toward improving the fairness of machine learning models, is another potentially valuable future direction. Finally, the paper suggests the exploration of more efficient computational methods for the trade-off curve calculation, which is critical for wider adoption of this approach. Addressing these points would significantly contribute to advancing the field of privacy-preserving machine learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

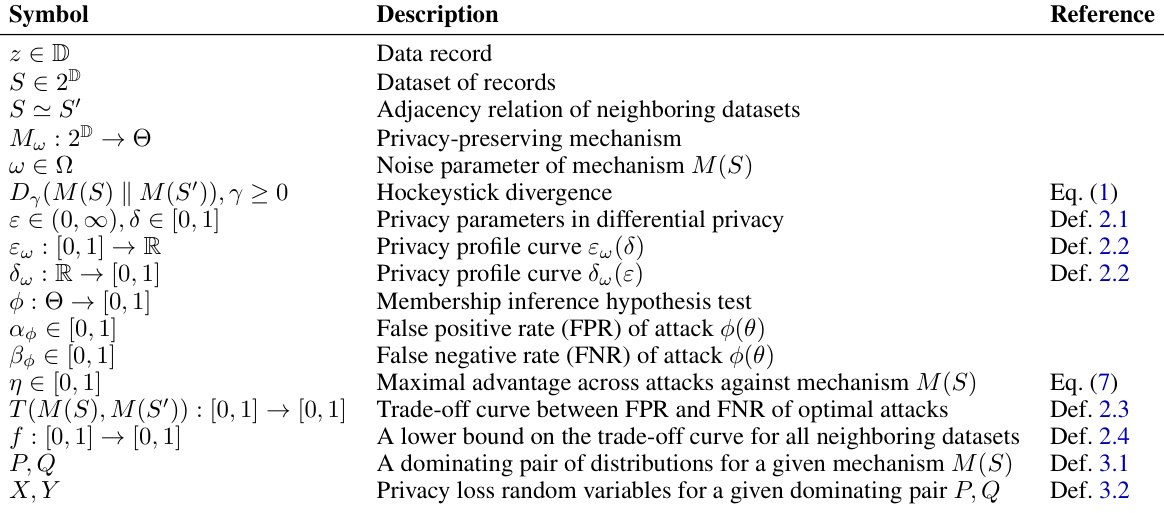

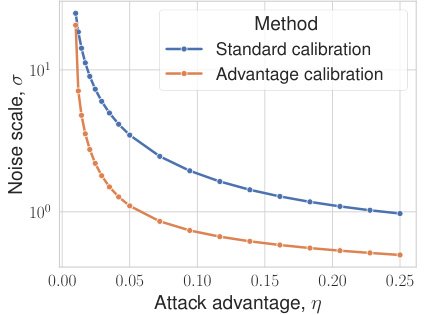

🔼 This figure compares two methods for calibrating noise in differentially private machine learning models: standard calibration and advantage calibration. The x-axis represents the attack advantage (η), a measure of an attacker’s success in recovering information. The y-axis represents the noise scale (σ), which is inversely proportional to model utility. Panel (a) shows that advantage calibration substantially reduces the required noise scale compared to standard calibration, improving utility. However, panel (b) illustrates a potential pitfall: advantage calibration can inadvertently increase the attack power (Δβ) in low-FPR regimes.

read the caption

Figure 2: Benefits and pitfalls of advantage calibration.

🔼 This figure shows the comparison of standard calibration and advantage calibration in terms of noise scale and attack risk. (a) shows that calibrating noise to attack advantage significantly reduces the required noise scale compared to the standard approach. (b) shows a pitfall of advantage calibration: it allows for higher attack power in the low FPR regime compared to standard calibration.

read the caption

Figure 2: Benefits and pitfalls of advantage calibration.

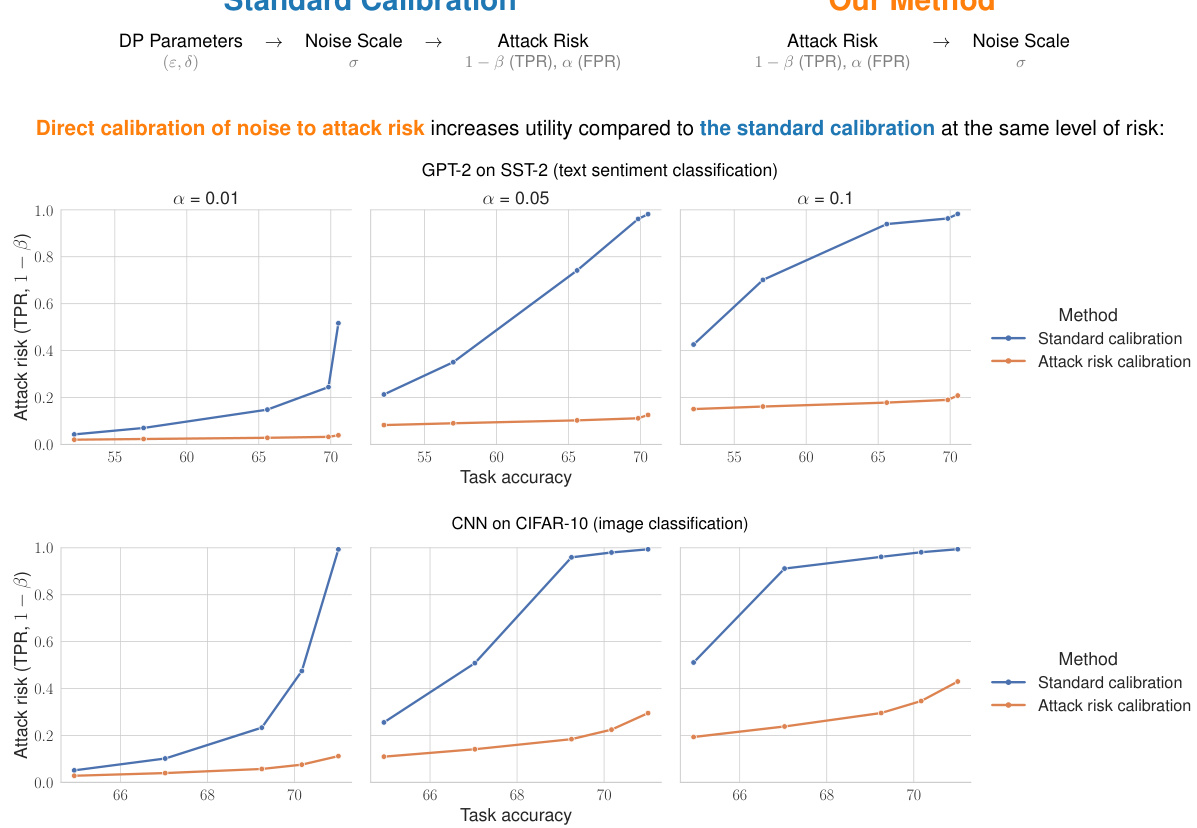

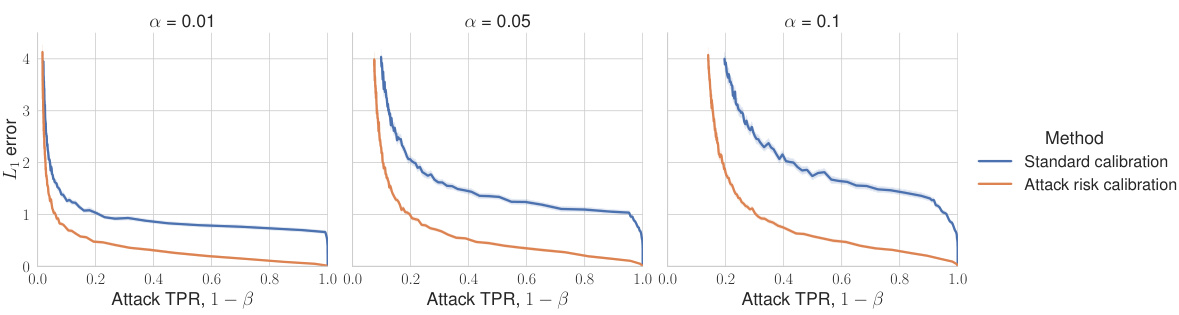

🔼 This figure shows the results of calibrating noise to the attack True Positive Rate (TPR, which is 1-FNR) at three different False Positive Rate (FPR) levels (0.01, 0.05, and 0.1). The x-axis represents the attack TPR, and the y-axis represents the noise scale (σ). The figure compares the noise scale required using the standard calibration method (blue line) versus the proposed TPR/FPR calibration method (orange line). The results demonstrate that the proposed method requires significantly less noise to achieve the same level of privacy risk (specified by the FPR and TPR) compared to the standard calibration. The key finding is that directly calibrating to TPR/FPR avoids the pitfall of advantage calibration, which is a decrease in privacy for the low FPR regime.

read the caption

Figure 3: Calibration to attack TPR (i.e., 1–FNR) significantly reduces the noise scale in low FPR regimes. Unlike calibration for attack advantage, this approach does not come with a deterioration of privacy for low FPR, as it directly targets this regime.

🔼 This figure shows the test accuracy achieved by two different models (GPT-2 for text sentiment classification and CNN for image classification) trained with differential privacy. The x-axis represents the accuracy of the model, while the y-axis represents the sensitivity of a privacy attack. Different lines represent different false positive rates (α) for the privacy attack. The figure demonstrates that direct calibration of noise to attack risk (our method) leads to significantly higher accuracy than standard calibration for the same level of attack risk.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test accuracy (x-axis) of a privately finetuned GPT-2 on SST-2 text sentiment classification dataset (top) and a convolutional neural network on CIFAR-10 image classification dataset (bottom). The DP noise is calibrated to guarantee at most a certain level of privacy attack sensitivity (y-axis) at three possible attack false-positive rates α ∈ {0.01, 0.05, 0.1}. See Section 4 for details.

🔼 This figure shows the test accuracy achieved by two different machine learning models (GPT-2 for text sentiment classification and CNN for image classification) trained using differential privacy. The x-axis represents the test accuracy, and the y-axis represents the attack sensitivity. The figure compares the standard calibration method with the proposed attack-aware calibration method. The results demonstrate that the attack-aware calibration method achieves higher accuracy at the same privacy level, demonstrating that directly calibrating noise to attack risk leads to significantly better model utility.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test accuracy (x-axis) of a privately finetuned GPT-2 on SST-2 text sentiment classification dataset (top) and a convolutional neural network on CIFAR-10 image classification dataset (bottom). The DP noise is calibrated to guarantee at most a certain level of privacy attack sensitivity (y-axis) at three possible attack false-positive rates a ∈ {0.01, 0.05, 0.1}. See Section 4 for details.

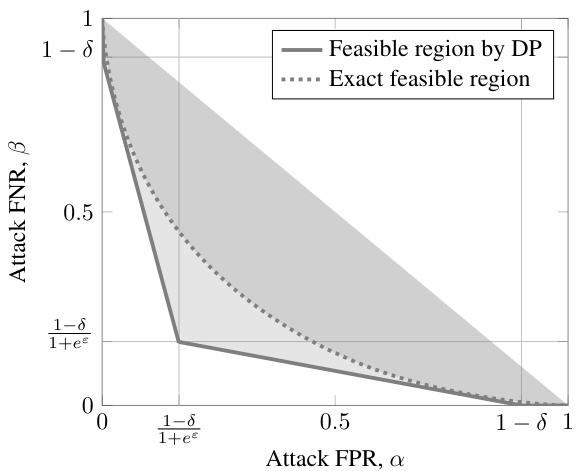

🔼 This figure illustrates the trade-off between the false positive rate (FPR) and the false negative rate (FNR) for membership inference attacks against a Gaussian mechanism satisfying (ε, δ)-differential privacy. The shaded region represents the area of possible (FPR, FNR) pairs allowed by the (ε, δ)-DP guarantee. The solid line shows a conservative approximation of this region, while the dotted line provides a more accurate representation of the achievable trade-off. The point closest to the origin (0,0) corresponds to the maximum advantage an attacker can achieve.

read the caption

Figure 5: Trade-off curves of a Gaussian mechanism that satisfies (ε, δ)-DP. Each curve shows a boundary of the feasible region (greyed out) of possible membership inference attack FPR (α) and FNR (β) pairs. The solid curve shows the limit of the feasible region guaranteed by DP via Eq. (5), which is a conservative overestimate of attack success rates compared to the exact trade-off curve (dotted). The maximum advantage η is achieved with FPR and FNR at the point closest to the origin.

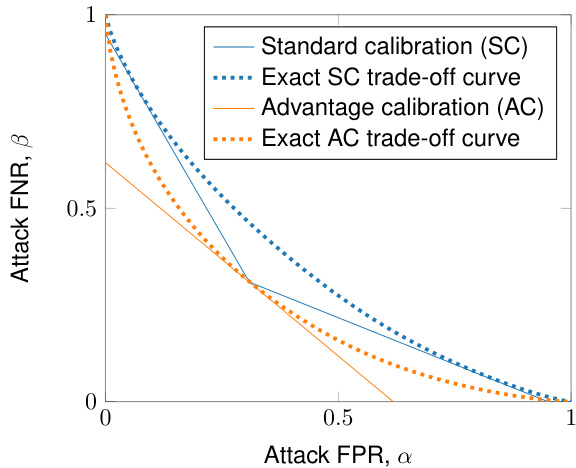

🔼 This figure compares the attack sensitivity (FNR) for two different calibration methods: standard calibration and advantage calibration. Both methods are applied to a Gaussian mechanism. The plot shows that while both methods result in a trade-off between attack FPR and FNR, the increase in attack sensitivity when using advantage calibration is less pronounced compared to a generic (ε, δ)-DP mechanism. This suggests that calibrating directly to the desired attack risk (advantage) might be less detrimental to utility for Gaussian mechanisms than for other mechanisms.

read the caption

Figure 6: The increase in attack sensitivity due to calibration for advantage is less drastic for Gaussian mechanism than for a generic (ε, δ)-DP mechanism.

🔼 The figure shows the results of calibrating the noise to achieve a target attack TPR (true positive rate), which is 1 minus the FNR (false negative rate), at three different low FPR (false positive rate) levels. The standard calibration method and the proposed attack risk calibration method are compared. The results demonstrate that the attack risk calibration significantly reduces the required noise scale, especially in the low FPR regimes, without compromising privacy.

read the caption

Figure 3: Calibration to attack TPR (i.e., 1–FNR) significantly reduces the noise scale in low FPR regimes. Unlike calibration for attack advantage, this approach does not come with a deterioration of privacy for low FPR, as it directly targets this regime.

More on tables

🔼 This table summarizes the notations used throughout the paper. It includes symbols for data records, datasets, neighboring relations, mechanisms, privacy parameters, privacy profiles, hypothesis tests, attack risks, and various other mathematical objects used in the analysis of differential privacy.

read the caption

Table 1: Notation summary

🔼 This table summarizes the notations used throughout the paper. It includes symbols representing data records, datasets, neighboring relations, mechanisms, privacy parameters (epsilon and delta), privacy profiles, attack metrics (FPR, FNR, advantage), trade-off curves, and dominating pairs, along with their descriptions and references to relevant equations or definitions within the paper.

read the caption

Table 1: Notation summary

🔼 This table shows how to derive the false negative rate (FNR) β* given a fixed false positive rate (FPR) α* for three different operational risk measures: advantage η*, accuracy acc*, and positive predictive value (precision) ppv*. These calculations are used to calibrate noise using the methods described in Section 3.2 of the paper.

read the caption

Table 2: Some supported risk measures for calibration with a fixed level of FPR α*, with the derivation of the corresponding level of FNR β*. Given α* and the derived β*, we can calibrate noise using the procedure in Section 3.2.

🔼 This table summarizes the notations used throughout the paper. It includes symbols for data records, datasets, neighboring relations, mechanisms, noise parameters, privacy parameters, privacy profiles, attack rates, attack advantages, trade-off curves, dominating pairs, and privacy loss random variables. Each symbol is defined and the relevant equation number or definition is referenced.

read the caption

Table 1: Notation summary

Full paper#