↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Weakly supervised learning trains models using potentially inaccurate or incomplete labels (pseudolabels), often from simpler models or rules. Existing theories struggle to explain why strong student models trained on these weak labels can often outperform their teachers, demonstrating both pseudolabel correction (fixing teacher mistakes) and coverage expansion (generalizing to unseen data). This is a significant problem, as it hinders the development of better, more reliable weakly supervised learning algorithms.

This paper introduces a novel theoretical framework to address these issues. The authors present new error bounds that explicitly account for pseudolabel correction and coverage expansion using expansion properties of the data distribution and the student model’s hypothesis class. They also propose a way to check the expansion properties from a finite dataset and provide empirical evidence showing the validity of their theory. This work significantly advances our theoretical understanding of weak-to-strong generalization and helps guide the development of more effective weakly-supervised learning techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in weakly supervised learning and related fields. It provides a novel theoretical framework that explains the surprising success of weak-to-strong generalization, a phenomenon where strong models outperform their weak teachers. This addresses a major gap in existing theory and opens exciting new avenues for improving the design and analysis of weakly supervised learning algorithms. The findings directly impact the design and application of weak supervision techniques, offering valuable insights for optimizing model performance in various applications. The introduction of verifiable expansion conditions further enhances the practical applicability of the theoretical findings, guiding future research towards more efficient and robust methods.

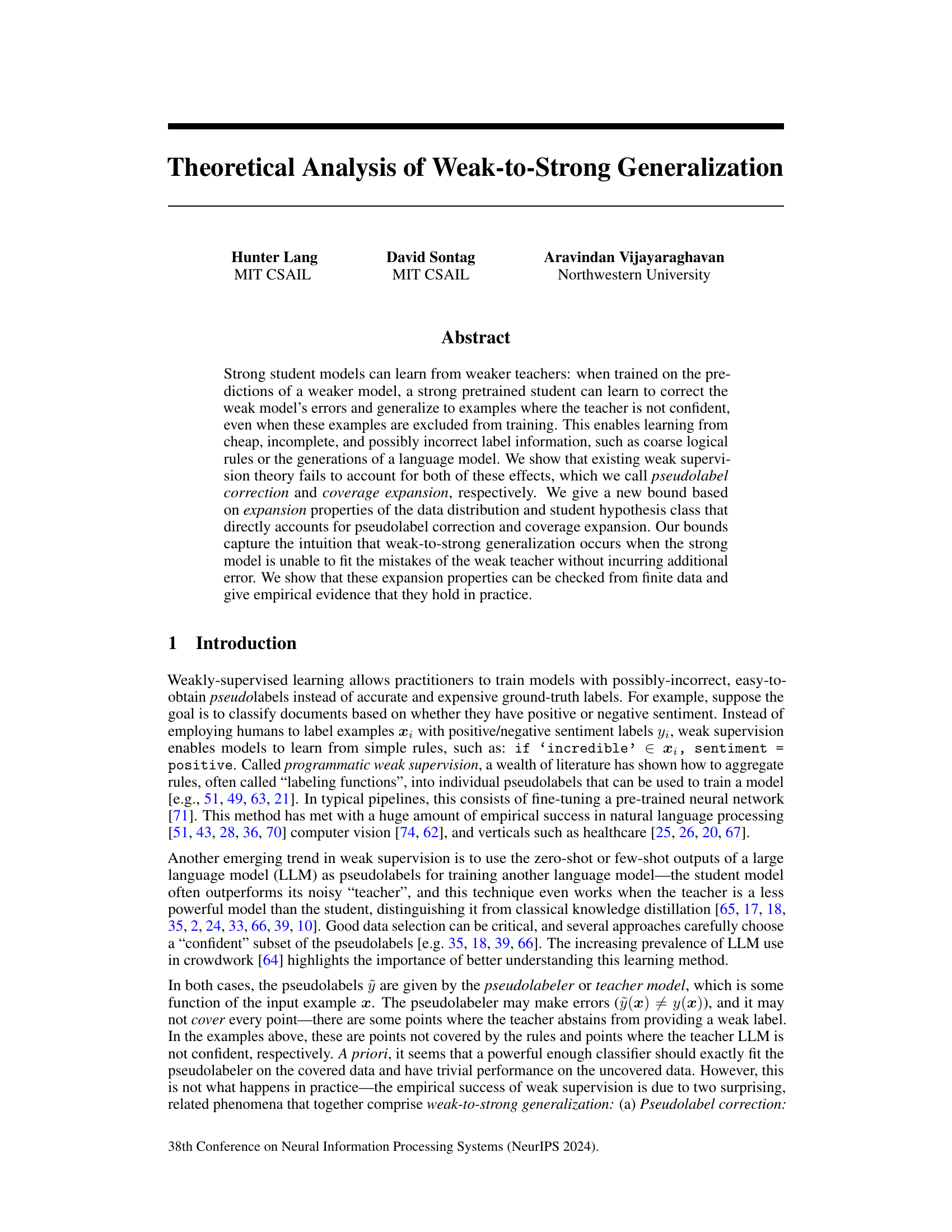

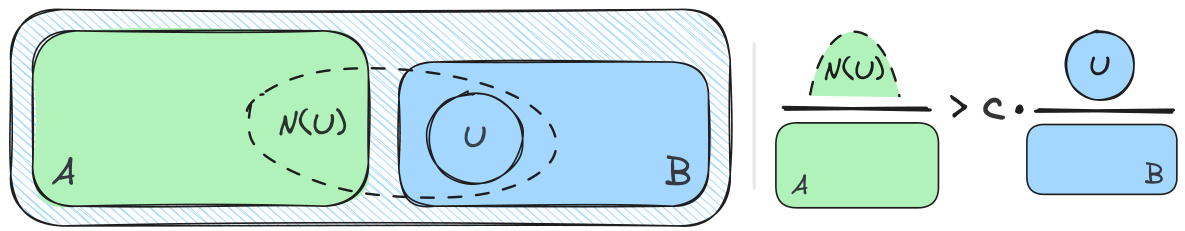

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the concept of relative expansion, a key condition in the paper’s theoretical analysis. The left side shows two sets, A (green) and B (blue), with set U (light blue circle) being a subset of B. The neighborhood of U, N(U), is represented by the dashed green oval. Relative expansion means that the ratio of the probability of N(U) in set A to the probability of U in set B must be greater than or equal to a constant c. The right side provides a simplified graphical representation of this condition as fractions, emphasizing the relationship between the size of the neighborhood of U within A and the size of U within B.

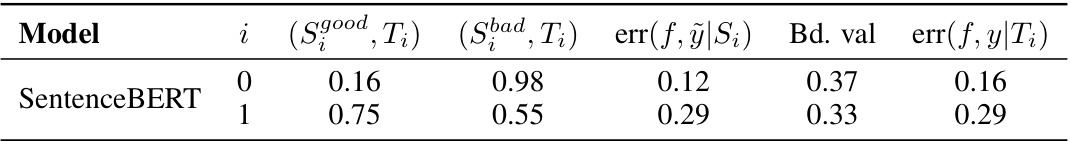

This table presents the results of measuring expansion and calculating error bounds for the covered sets (Si) based on Theorem 4.1. It demonstrates the empirical evidence supporting the theory’s assumptions and the occurence of pseudolabel correction. The table includes measured expansion values, pseudolabel errors, classifier errors on weak labels, calculated error bounds, and actual classifier errors on true labels. The comparison between the calculated bound and the actual error highlights whether pseudolabel correction is likely to occur for each label.

In-depth insights#

Weak-to-Strong Generalization#

The concept of “Weak-to-Strong Generalization” in the context of machine learning describes a surprising phenomenon where a powerful, strong model trained on the predictions of a weaker model significantly surpasses the teacher’s performance. This is particularly interesting because it challenges traditional assumptions of supervised learning. The success stems from two key aspects: Pseudolabel Correction, where the strong student corrects the errors made by the weak teacher, and Coverage Expansion, where the student generalizes beyond the limited examples the teacher had confidence in. The paper analyzes this phenomenon theoretically, introducing novel error bounds that explicitly account for these two effects, highlighting how expansion properties of the data distribution and robustness of the student model are crucial for successful weak-to-strong generalization. This theoretical analysis provides a more nuanced understanding than previous noisy label approaches, which fail to completely capture the observed behavior.

Pseudolabel Correction#

The concept of “Pseudolabel Correction” addresses a critical challenge in weakly supervised learning where inaccurate or incomplete pseudolabels, generated by a weaker model, hinder the training of a stronger student model. The core idea is that the student model, during training, can learn to identify and correct errors present in the pseudolabels, ultimately outperforming its teacher. This phenomenon is theoretically grounded by considering the distribution of the data and the model’s robustness to errors. Expansion properties, which define how ‘good’ (correctly labeled) data points relate to ‘bad’ (incorrectly labeled) ones, play a crucial role. If ‘bad’ points are surrounded by many ‘good’ neighbors, the student model can potentially generalize well even with a noisy teacher. The success of pseudolabel correction hinges on the student model’s capacity to learn from these local relationships and generalize beyond the limited training data, exhibiting a ‘weak-to-strong’ generalization phenomenon.

Coverage Expansion#

The concept of “Coverage Expansion” in weak supervision learning is crucial. It describes how a strong student model trained on weak labels from a weaker teacher model can generalize beyond the examples seen by the teacher. This surpasses the limitations of simple noisy-label settings, as the student model effectively learns from incomplete data. The paper explores this phenomenon by introducing expansion conditions, which posit that regions of data with incorrect or missing labels (the “uncovered” regions) are surrounded by regions with accurate labels (the “covered” regions). These conditions ensure that even when the student makes mistakes in the uncovered regions, the errors aren’t isolated, and the impact on overall accuracy is limited. The strength of this approach lies in its ability to directly account for both pseudolabel correction and coverage expansion, creating more realistic and applicable error bounds. The authors propose that verifiable expansion conditions can be statistically checked and empirically validated, making this framework more robust and applicable to real-world scenarios.

Robust Expansion#

Robust expansion, a concept crucial to the paper’s theoretical framework, addresses the limitations of traditional expansion assumptions in weakly supervised learning. It acknowledges that classifiers aren’t perfectly robust, introducing a parameter η to quantify the average-case robustness, representing the probability of a classifier giving different labels to a point and its neighbor. Robust expansion ensures that even with imperfect classifiers, sufficiently large subsets of data points with correct pseudo-labels expand to influence areas with incorrect or missing labels. This robustness is critical because it allows for the generalization capabilities of a strong model, trained on noisy pseudo-labels, to reliably extend to unseen data points. The paper proposes a method to statistically check for robust expansion from finite data which strengthens the theoretical framework and practical applicability. It moves beyond adversarial robustness, providing a more realistic and empirically relevant measure. This focus on average-case robustness makes the theoretical error bounds more practical for real-world weak supervision scenarios.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section would be crucial to assess the theoretical claims made in the paper. It should present results from experiments designed to test the expansion properties of the data distribution and the robustness of the student models. Specific details on datasets, model architectures, training procedures, evaluation metrics, and statistical significance tests are vital. The analysis should demonstrably show pseudolabel correction and coverage expansion, ideally comparing results to baselines that do not exhibit these phenomena. Quantitative results showing the improvement of the student model over the teacher model, especially on the uncovered regions of data space, would significantly strengthen the paper’s conclusions. A discussion of how well the theoretical expansion properties are reflected in the real-world data, including potential discrepancies and their interpretations, is also crucial for a thorough empirical validation.

More visual insights#

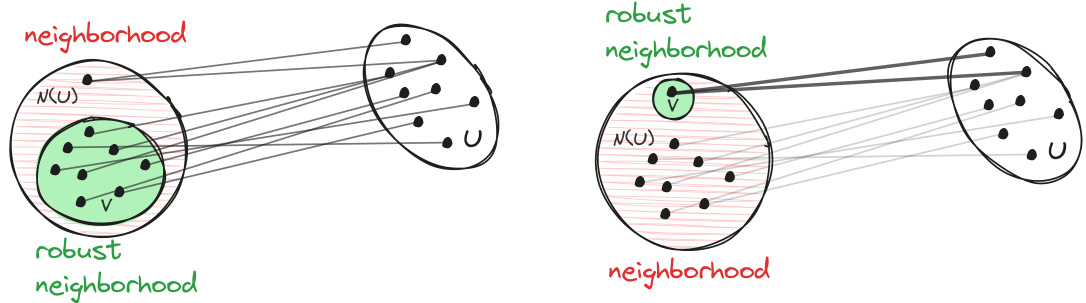

More on figures

This figure illustrates the concept of robust expansion, a key idea in the paper. Robust expansion is a generalization of standard expansion that accounts for the possibility of a few ‘bad’ edges in the graph connecting two sets. The left panel depicts good robust expansion, where even after removing a small fraction of the edges (the bad edges) there is still a significant connection between sets A and B. The right panel depicts bad robust expansion where even a small fraction of edge removals completely breaks the connection between the sets. The authors define robust expansion formally in Definition 7 and use it in Section 4 to derive bounds that are more robust to adversarial examples and noise.

This figure illustrates the process of generating neighborhood points using a paraphrase model and GPT-4. Starting with a point mislabeled by the weak supervision model, it shows how to generate a point in the uncovered region and then use that to create a point with the correct label via paraphrase. This process is used to check the expansion condition empirically.

More on tables

This table compares the measured expansion values for two different types of expansion: good-to-bad (G2B) and bad-to-good (B2G). It highlights that while Theorem B.1 (pseudolabel correction) only requires G2B expansion to hold for a positive constant c, Theorem C.2 (a result from prior work) requires the stronger condition that B2G expansion holds for a constant c > αi/(1-αi). The table shows empirical measurements of these expansion values for two different classes (i=0 and i=1), demonstrating that G2B expansion holds in practice for both classes, whereas the B2G expansion requirement of Theorem C.2 is not satisfied for the i=1 class.

This table presents the test accuracy results for linear probes trained using both gold and weak labels on the IMDB dataset. It breaks down the accuracy across the covered sets (So, S1), where the weak labels are available, and the uncovered sets (To, T1), where they are not. The results show the impact of weak supervision on the student model’s performance, demonstrating variation in pseudolabel correction and coverage expansion across different classes. Standard deviations across five training folds are included for better understanding of the variability.

This table presents the measured expansion values and error bounds for the uncovered sets (T₁, T₂). It shows the results of applying Theorem B.2 to calculate the error bounds. The expansion values are obtained using the heuristic from Section 5, showing expansion from T₁ to both Sgood and Shad. The table compares the calculated error bounds with the actual worst-case errors observed in the experiments, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed theoretical framework.

Full paper#