↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

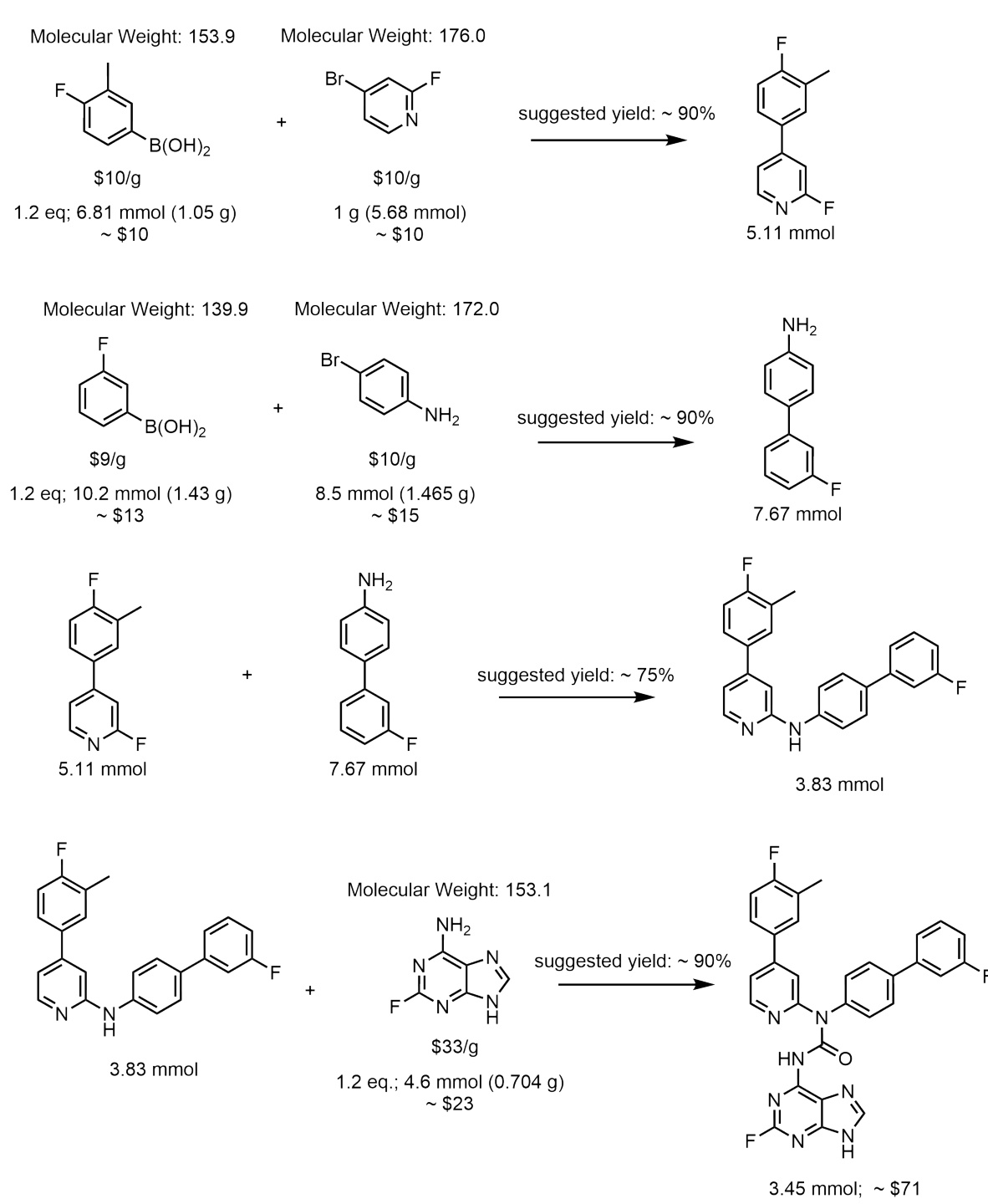

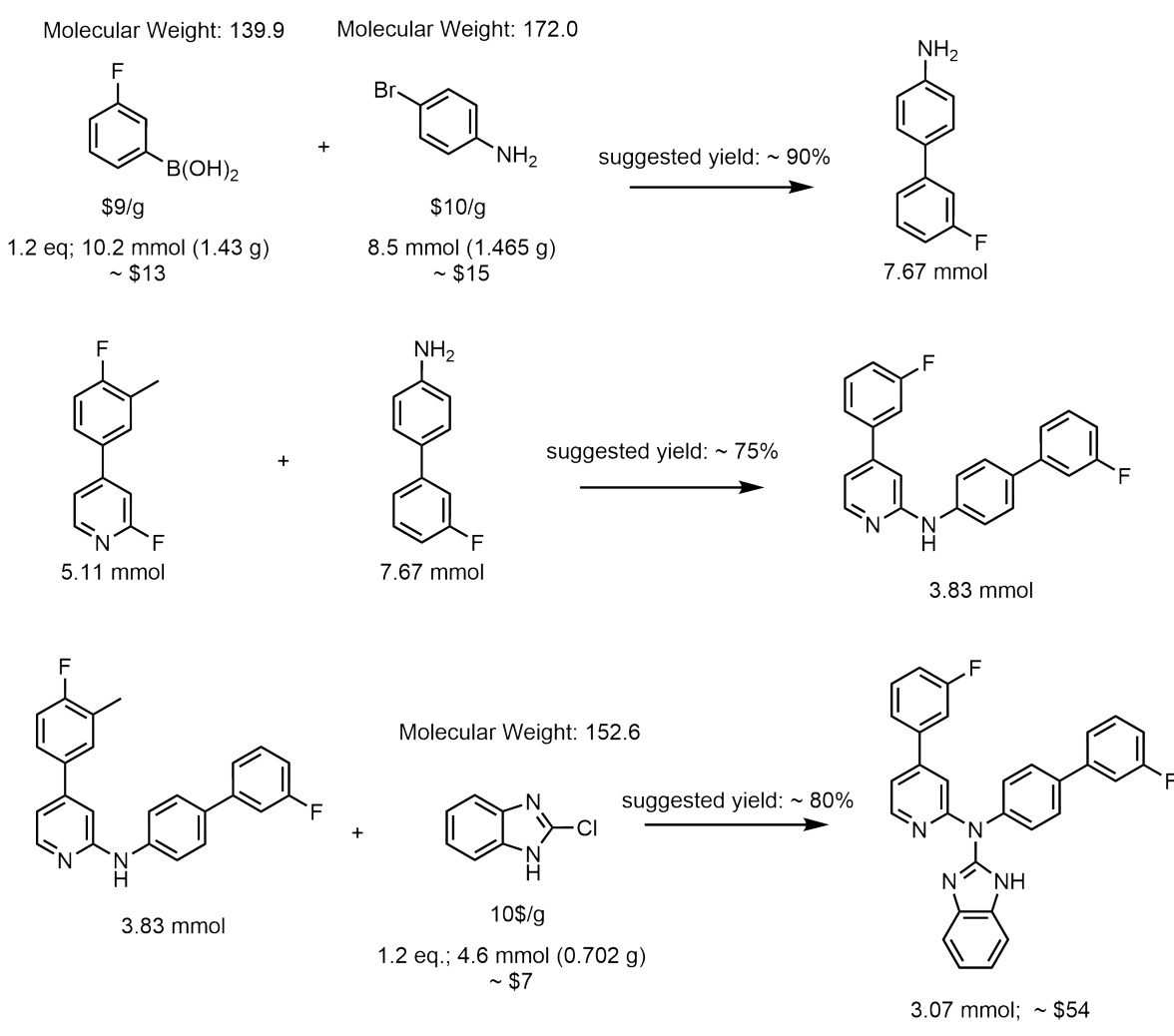

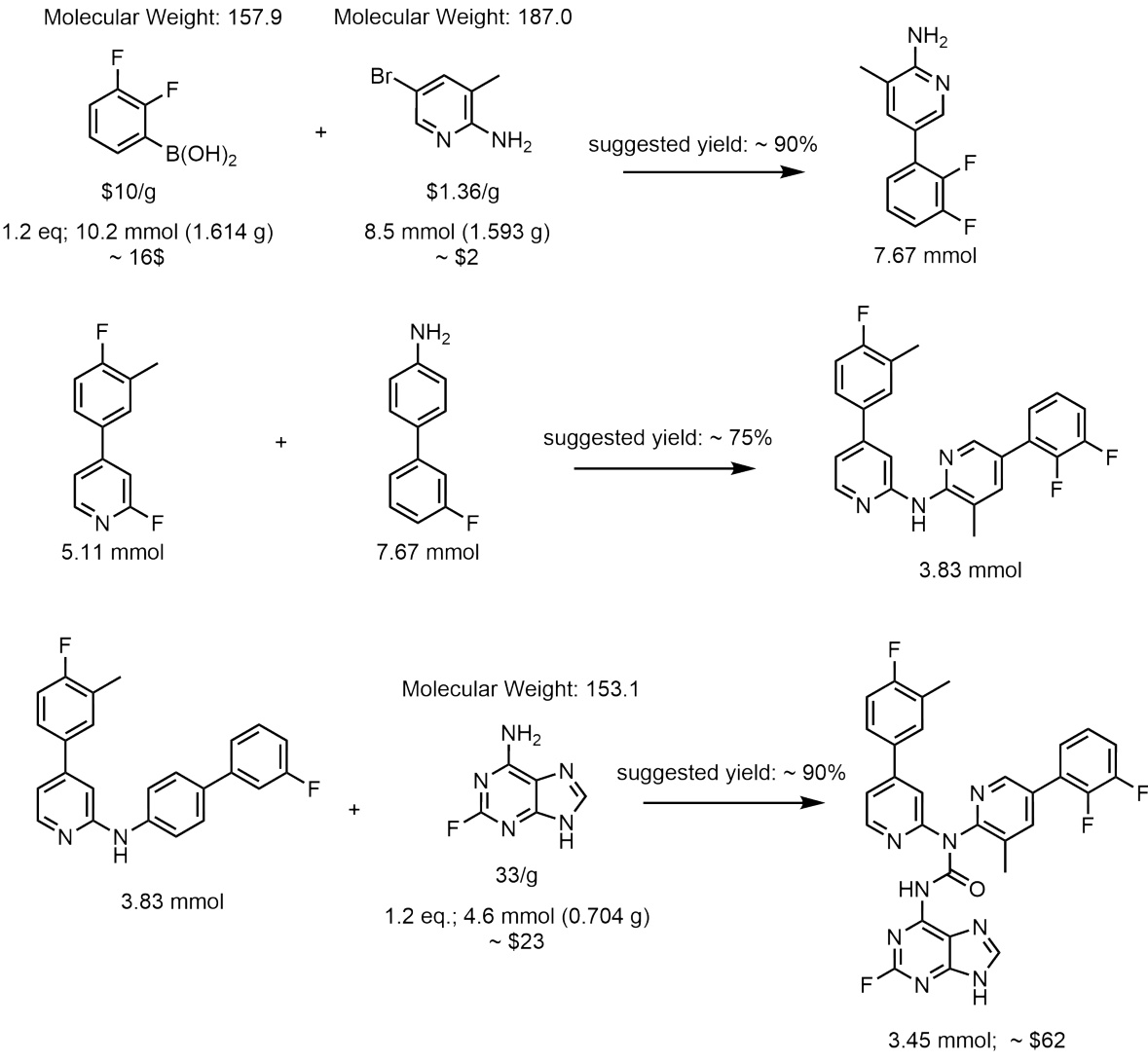

Developing new drugs traditionally involves screening vast libraries of existing compounds or relying on generative models that often produce molecules difficult to synthesize. This is inefficient and expensive. Existing machine learning approaches for molecule generation often struggle to produce molecules that are readily synthesizable, hindering experimental validation.

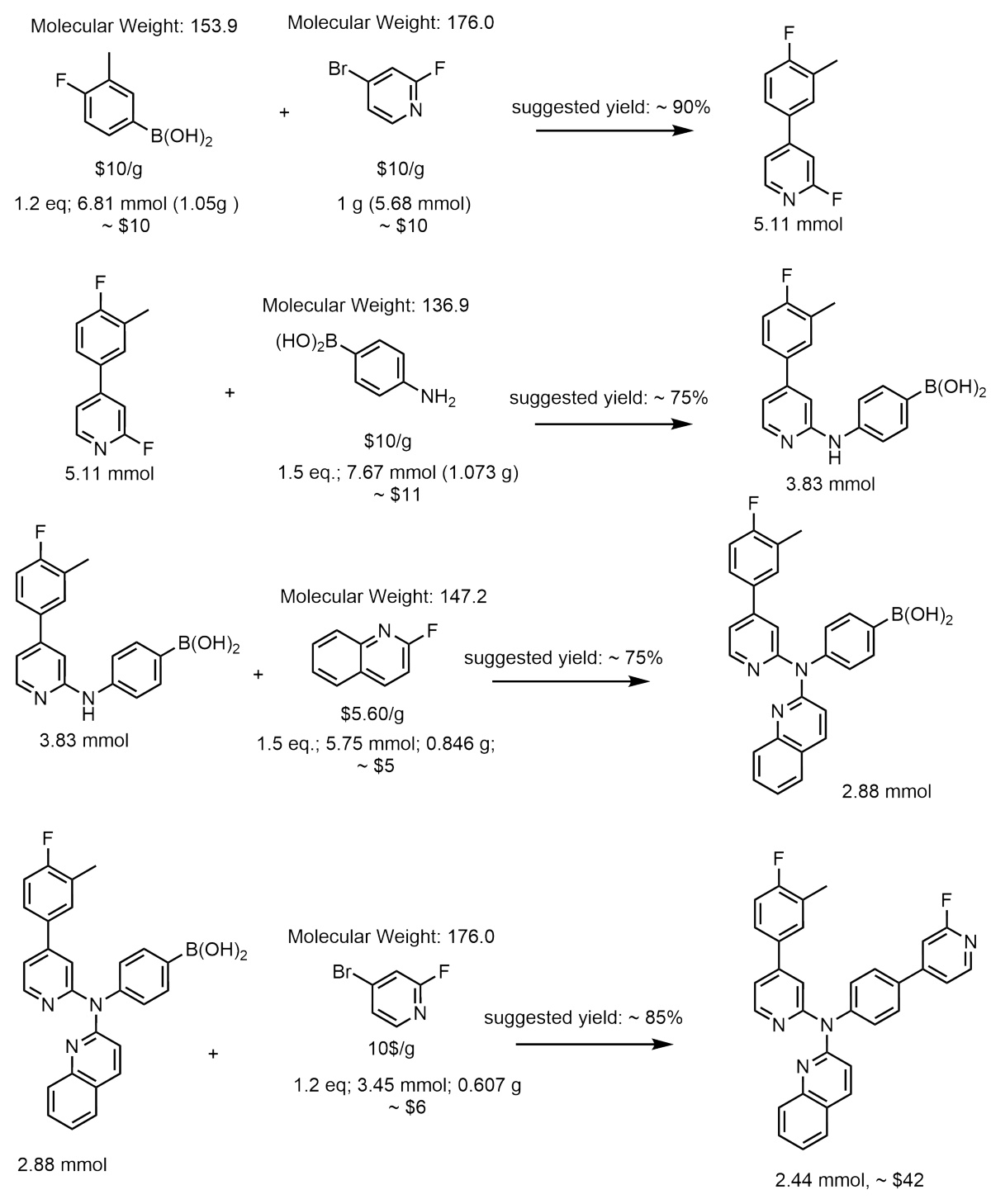

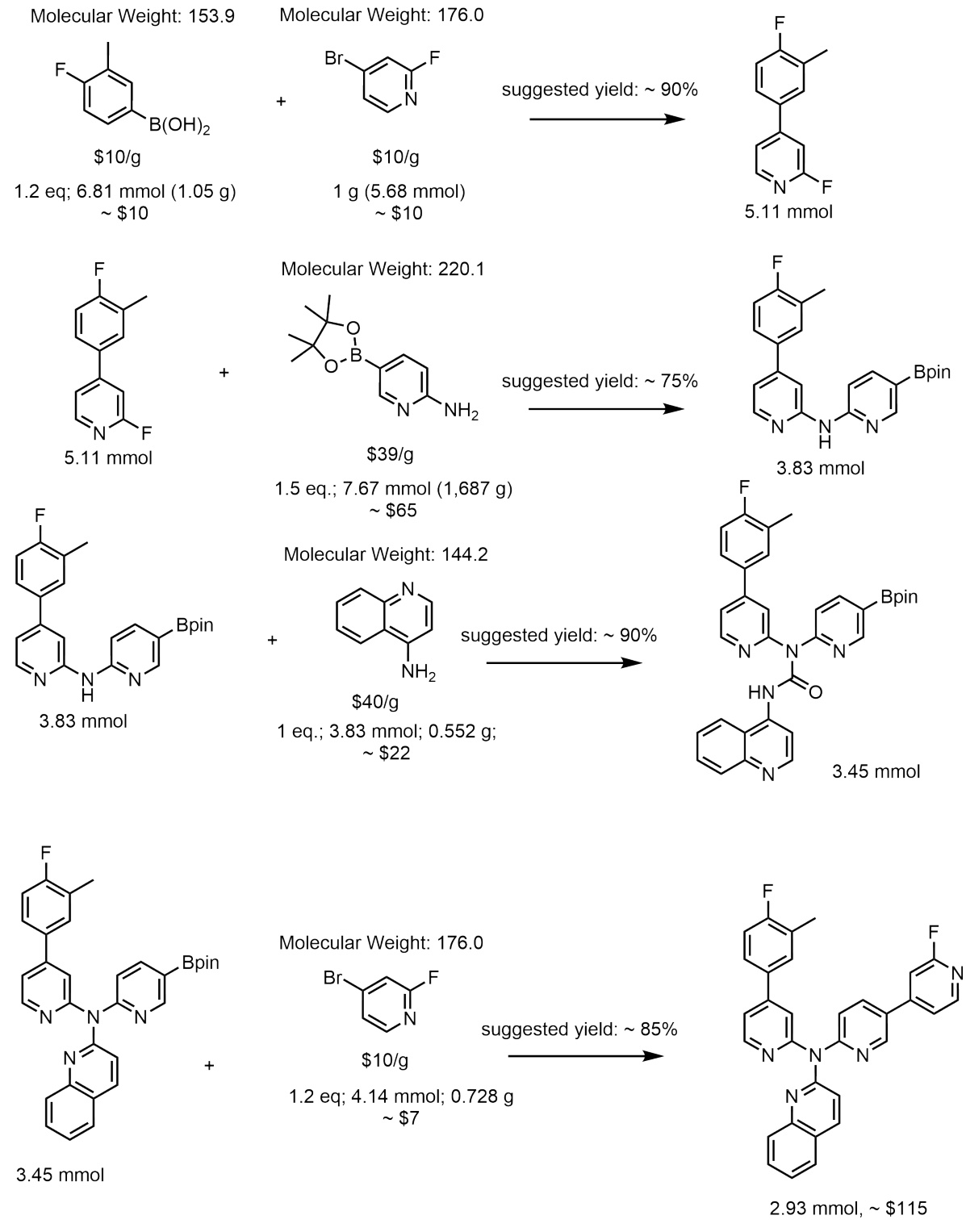

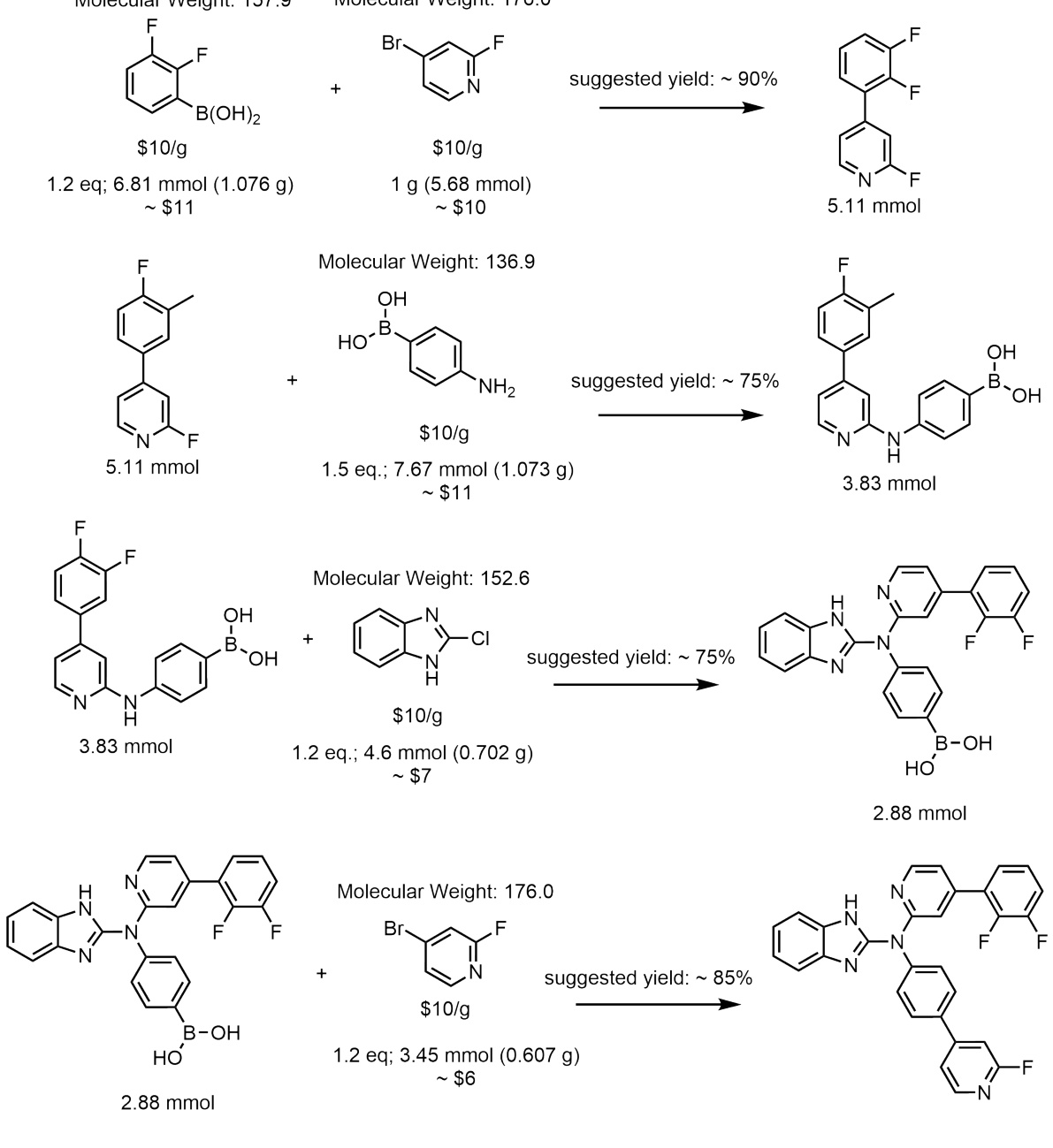

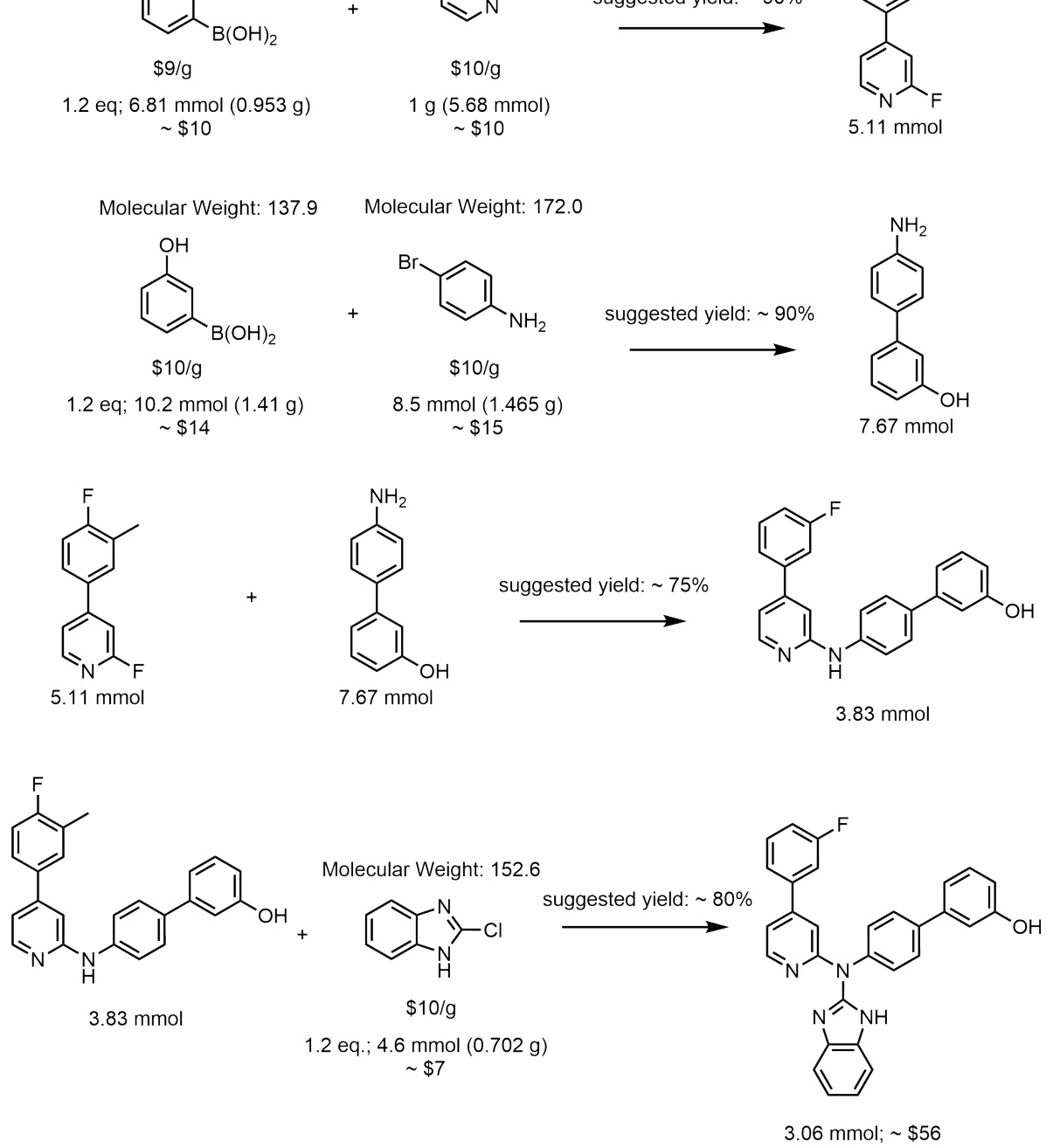

The researchers address this by proposing Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN), a novel generative model operating in the space of chemical reactions. RGFN leverages a curated set of high-yield chemical reactions and affordable building blocks, ensuring synthesizability while maintaining the quality of generated molecules. The results show that RGFN outperforms other methods across multiple screening tasks, including docking score approximation and biological activity estimation. RGFN’s ability to scale to large fragment libraries further expands its potential for drug discovery.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in drug discovery and cheminformatics. It introduces a novel approach to molecular generation that directly addresses the challenge of synthesizability, a significant bottleneck in the field. The Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) framework offers a scalable and efficient method for generating molecules with readily available synthetic routes, opening new avenues for experimental validation and accelerating the drug development process. This method is particularly important given the growing interest in integrating machine learning with chemical synthesis.

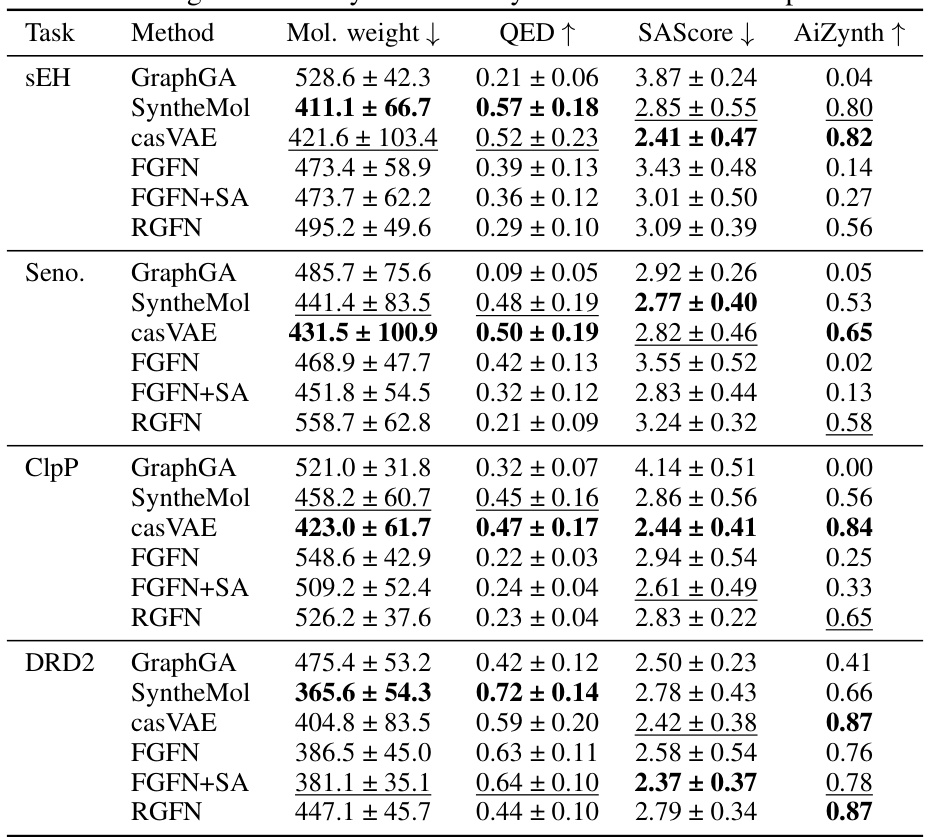

Visual Insights#

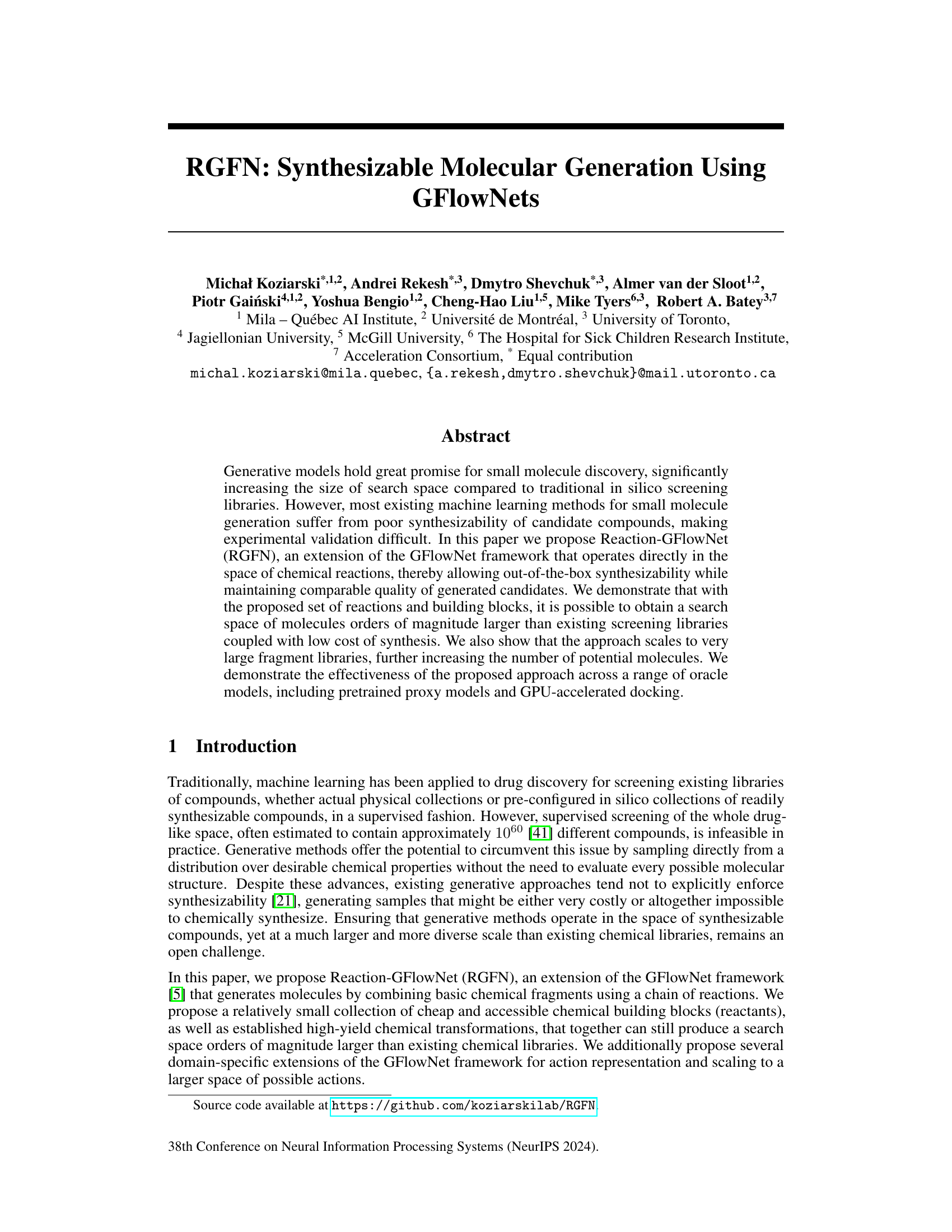

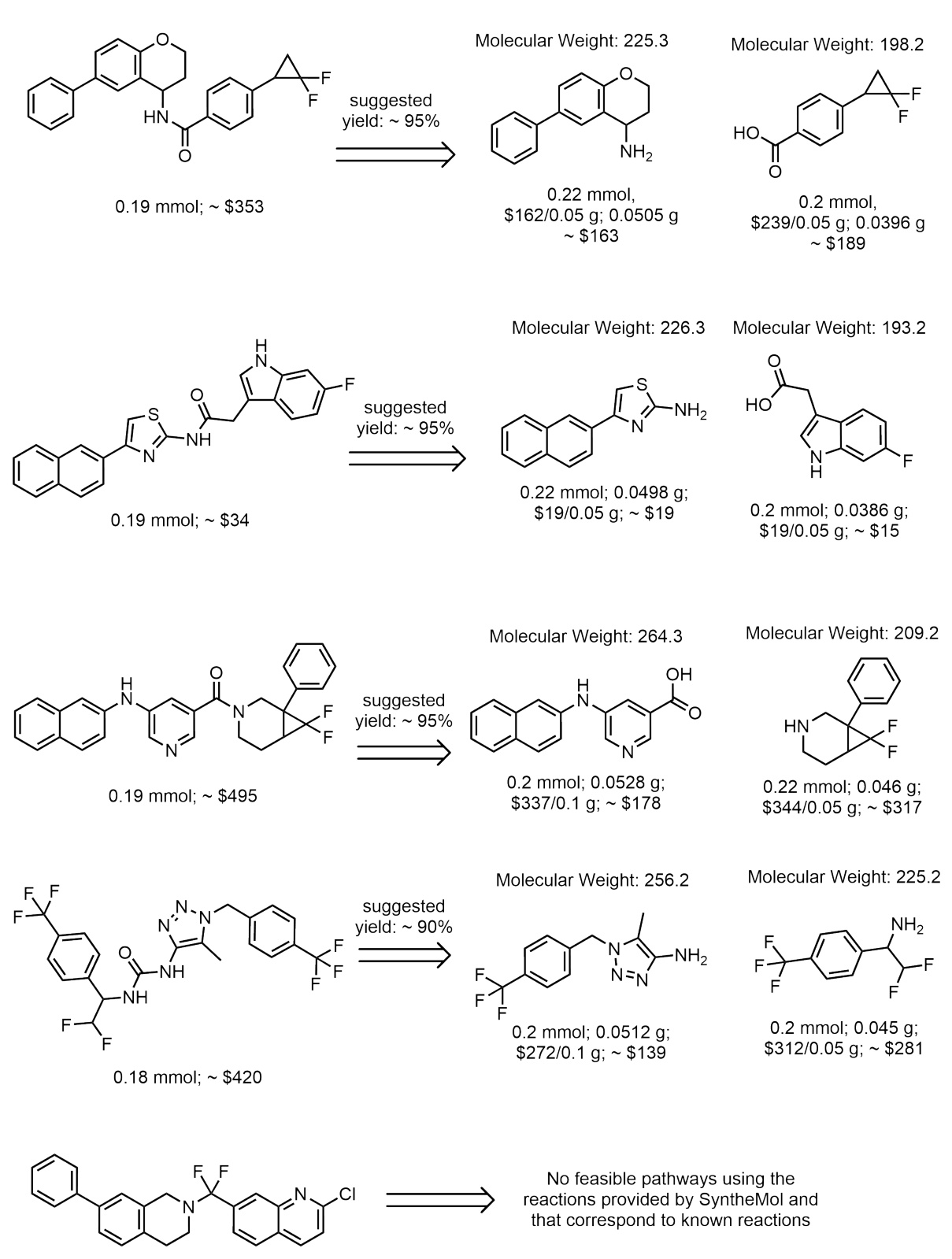

This figure illustrates the process of molecular generation using Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). It starts by selecting an initial building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant to perform an in-silico reaction. This process continues until a stop action is selected, and the final molecule is evaluated using a reward function.

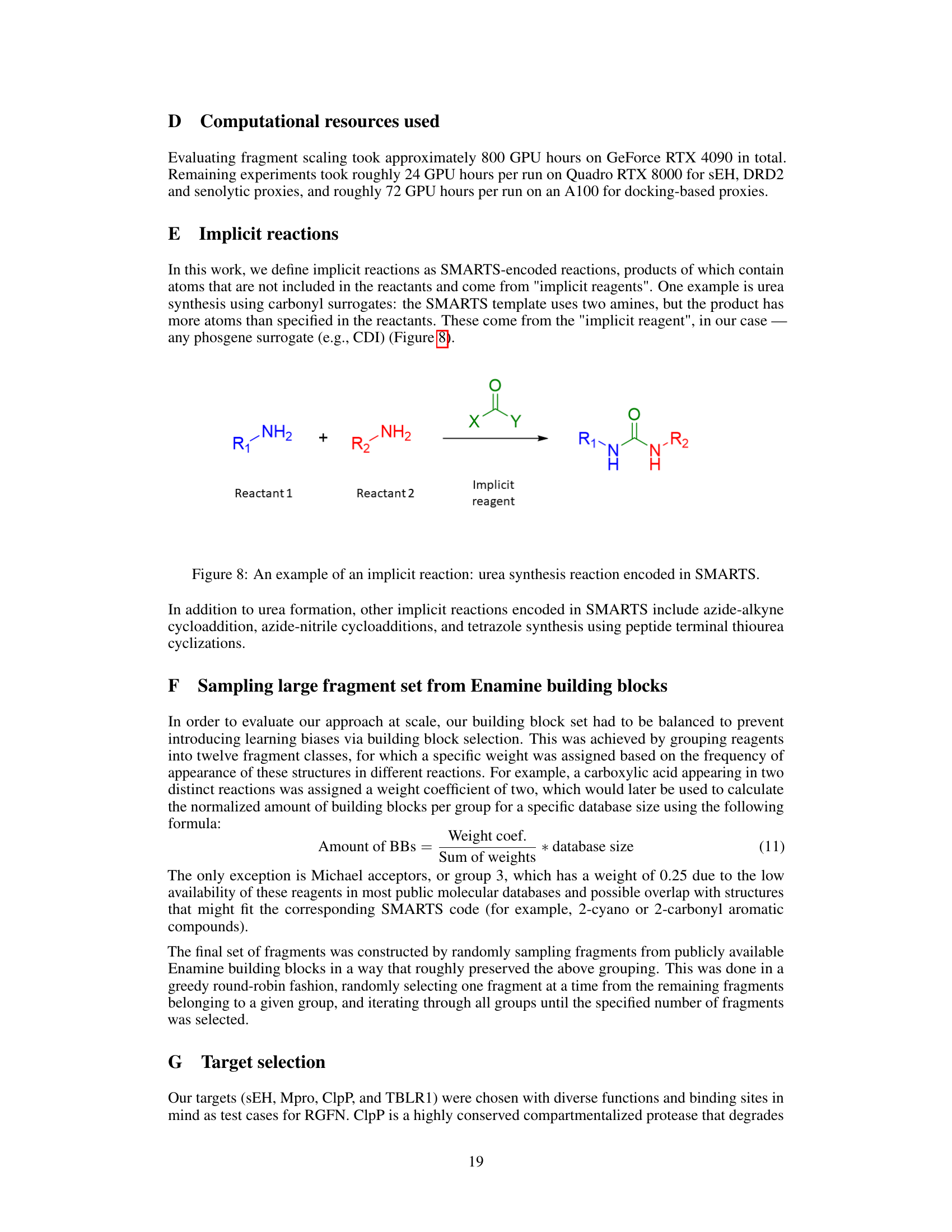

This table compares several methods for molecular generation across four different tasks (sEH proxy, senolytics proxy, DRD2 proxy, and ClpP docking). For each method and task, it shows the average molecular weight, quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility score (SAScore), and the average number of molecules with a valid retrosynthesis pathway found using AiZynthFinder. Lower molecular weight and higher QED and AiZynth scores are desirable. The table highlights the trade-off between generating high-quality molecules (according to the various scoring functions) and synthesizability, with RGFN demonstrating a balance.

In-depth insights#

Synth. Mol. Gen.#

Synthetic molecular generation (‘Synth. Mol. Gen.’) methods are crucial for drug discovery, offering a vast chemical space exploration beyond traditional libraries. Current approaches often struggle with synthesizability, generating molecules that are impractical or costly to produce. This necessitates the development of novel methods that explicitly consider synthesizability, thus bridging the gap between in silico design and experimental validation. Reaction-based methods show promise, directly operating within the space of chemical reactions to ensure synthesizable molecules are generated. However, even these approaches have limitations concerning reaction diversity and the complexity of the molecules that can be created. Future developments should focus on incorporating diverse reaction sets, diverse fragment libraries, and robust predictive models for reaction outcomes. Efficient algorithms, such as GFlowNets, provide a scalable framework for handling large chemical spaces while maintaining synthesizability. This ultimately leads to the acceleration of drug discovery through the computationally efficient generation of high-quality, synthesizable molecules.

RGFN: GFlowNet#

The heading ‘RGFN: GFlowNet’ suggests a novel approach to molecular generation using the GFlowNet framework. RGFN likely represents a Reaction-based GFlowNet, extending the original GFlowNet architecture to operate directly within the space of chemical reactions. This is a significant departure from traditional methods which often struggle with synthesizability. By working directly with reactions, RGFN inherently incorporates synthesizability into the generation process, making experimental validation more feasible. This approach also suggests a focus on efficient and readily available chemical building blocks and reactions, contributing to lower costs associated with synthesis. The combination of GFlowNet’s sampling capabilities with this reaction-based approach likely results in a larger and more diverse chemical space than achievable by conventional methods, thereby accelerating drug discovery and materials science.

Synthesizability#

The concept of “synthesizability” in the context of molecule generation using machine learning is crucial for bridging the gap between in silico design and practical application. The challenge lies in generating molecules that are not only desirable in terms of properties (e.g., binding affinity, drug-likeness) but also readily synthesizable in a laboratory setting. Existing generative models often struggle with this aspect, producing molecules that are theoretically optimal but practically impossible or prohibitively expensive to make. This paper addresses this limitation by proposing a novel framework (Reaction-GFlowNet) that operates directly within the space of chemical reactions, thereby ensuring synthesizability by design. This approach offers a significant advantage over post-hoc filtering methods, as it directly influences the generation process. The effectiveness of this methodology is demonstrated across several diverse tasks, highlighting the importance of integrating synthesizability constraints into generative models for drug discovery and material science.

Experimental eval.#

An experimental evaluation section in a research paper would typically detail the methods used to test the proposed approach, including the datasets, metrics, and baseline methods used for comparison. A thoughtful analysis would delve into the selection rationale for each component: why those specific datasets? What are their limitations and how might they affect the results? Similarly, what metrics were chosen and why are they appropriate? Were there any alternative metrics considered and, if so, why were they rejected? A robust comparison requires a thorough examination of baseline methods. Are they truly appropriate comparators? How do the performance differences between the proposed approach and baselines highlight its strengths and weaknesses? The discussion should also address reproducibility, clarifying the experimental setup’s specifics to allow replication and validation of results. Finally, a strong experimental evaluation not only reports the results but also critically analyzes their implications, discussing potential limitations and suggestions for future work.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could focus on enhancing the chemical space explored by incorporating a more extensive set of reactions and building blocks. This would lead to the generation of more diverse and potentially potent molecules. Improving the accuracy of the scoring functions employed (e.g., through better docking algorithms or alternative scoring methods that better incorporate synthesizability and cost considerations) is also crucial for improved molecule generation quality. The integration of explicit synthetic planning into the model is another important avenue. Currently, the model only outputs the final molecule, without detailing the specific synthesis steps. Explicit synthetic route generation would further enhance the practical applicability of the generated molecules. Finally, experimental validation of a selection of the top molecules is key to confirming the model’s ability to discover novel and useful compounds, potentially guiding the refinement of both the molecular generation model and the associated scoring functions. This comprehensive approach is essential to bridge the gap between in silico design and experimental realization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

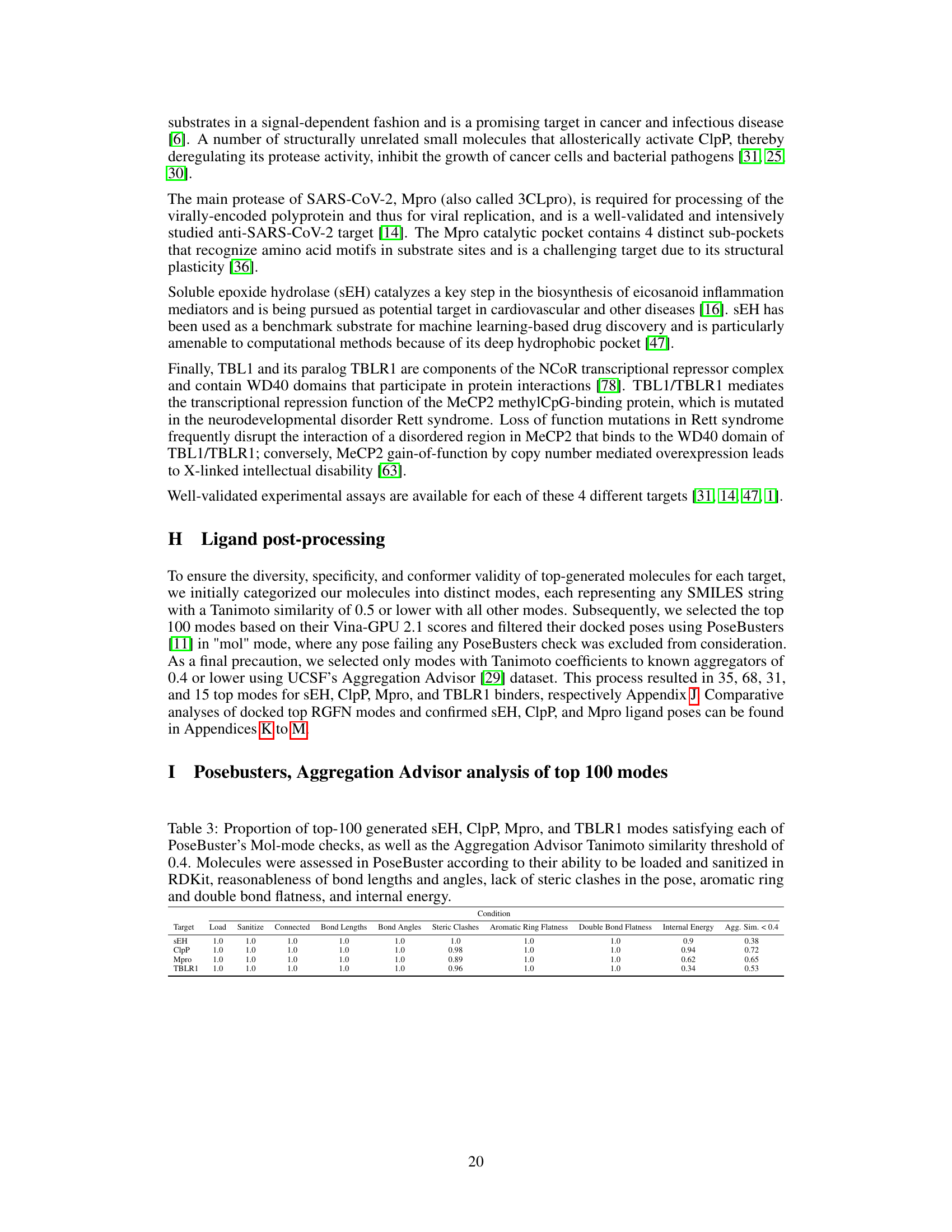

This figure shows the estimated state space size of the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) model as the maximum number of reactions used increases. Two variants of RGFN are compared: one using 350 hand-picked inexpensive building blocks, and another using an additional 8000 randomly selected building blocks from Enamine. The state space size of the Enamine REAL database (containing 6.5 billion compounds) is also shown for comparison.

Violin plots showing the distribution of rewards obtained by different methods (GraphGA, SyntheMol, casVAE, FGFN, FGFN+SA, and RGFN) across four different tasks: sEH proxy, senolytics proxy, DRD2 proxy, and ClpP docking. The plots illustrate the performance of each method in terms of achieving high rewards, which represent desirable molecular properties in the context of drug discovery.

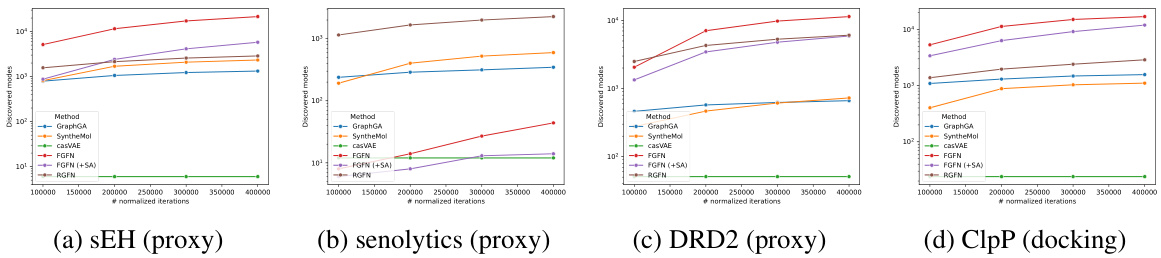

The figure shows the number of discovered modes (unique molecules with reward above a threshold and Tanimoto similarity to other modes below 0.5) for different methods (GraphGA, SyntheMol, casVAE, FGFN, FGFN+SA, and RGFN) across four different tasks (sEH proxy, senolytics proxy, DRD2 proxy, and ClpP docking). The x-axis represents the number of normalized iterations (proportional to the number of oracle calls for most methods, except for SyntheMol and casVAE, where a maximum number of oracle calls is imposed). The y-axis is the number of discovered modes. The results show that while RGFN doesn’t always achieve the best average reward, it consistently discovers a greater number of unique modes compared to other methods, especially when compared to other reaction-based methods.

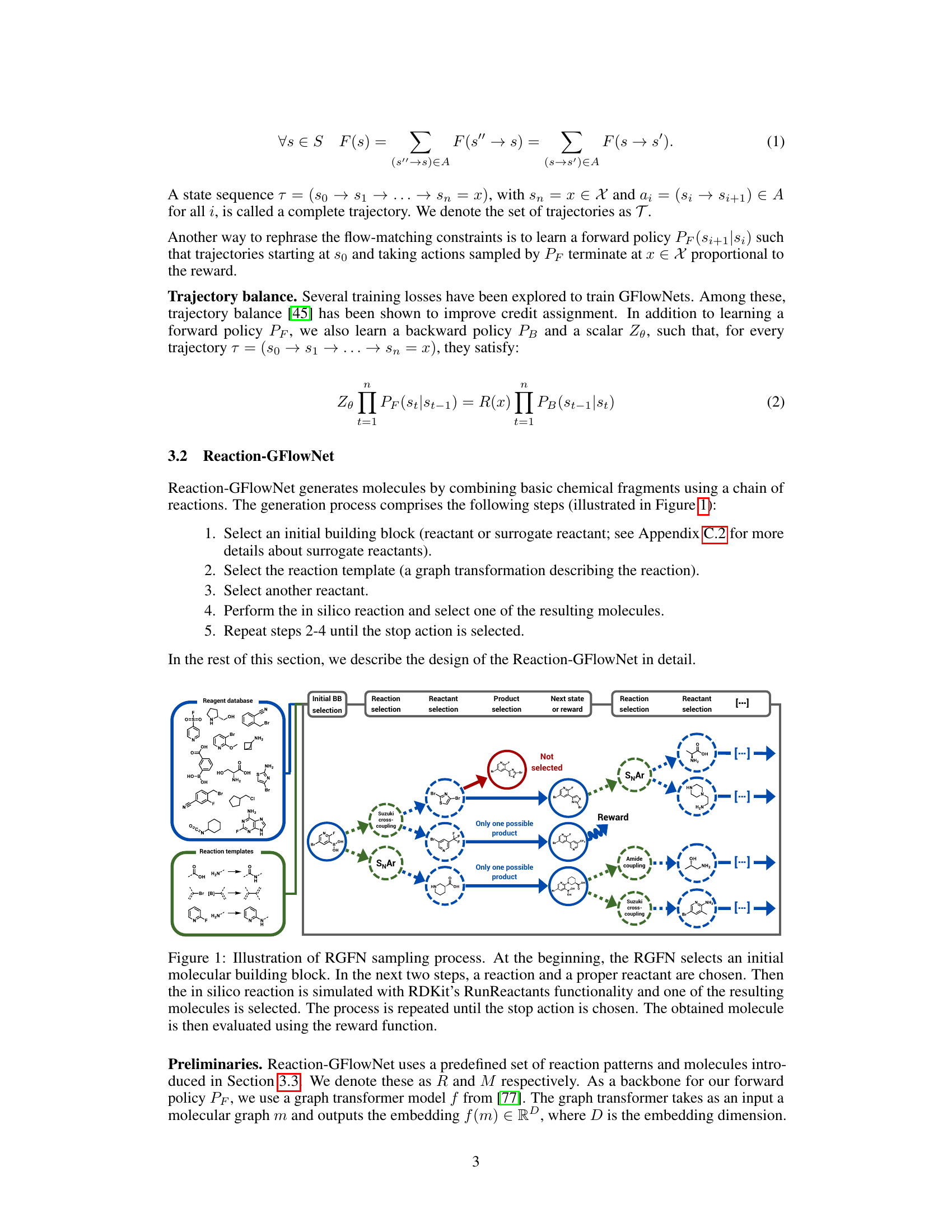

This figure compares the performance of independent and fingerprint-based embeddings in Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) when scaling to a larger fragment library. The results show that fingerprint embeddings significantly improve the number of discovered Murcko scaffolds, especially as the fragment library size increases. The y-axis represents the number of discovered scaffolds, and the x-axis represents the size of the chemical fragment library. The plot shows the median and range (minimum to maximum values) across three random seeds.

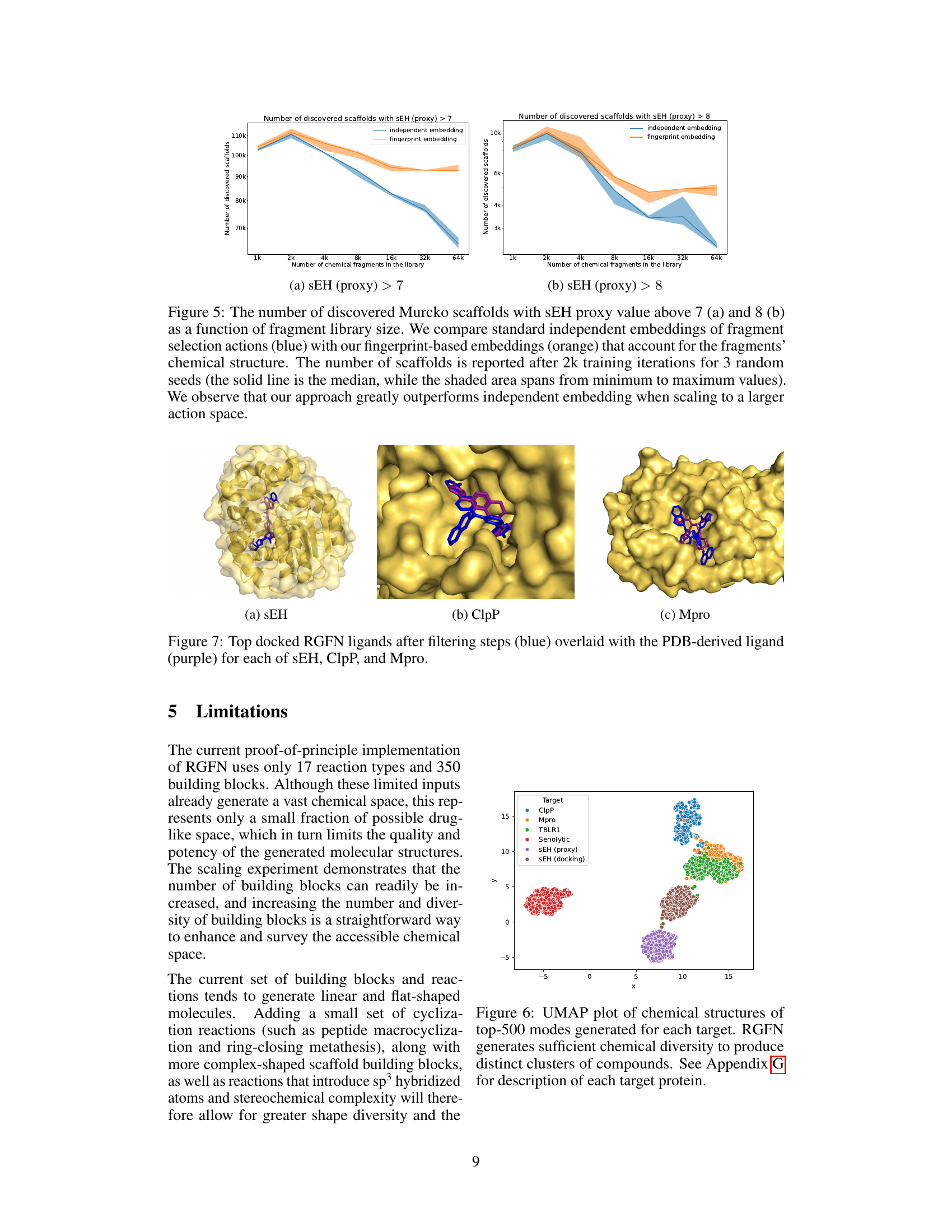

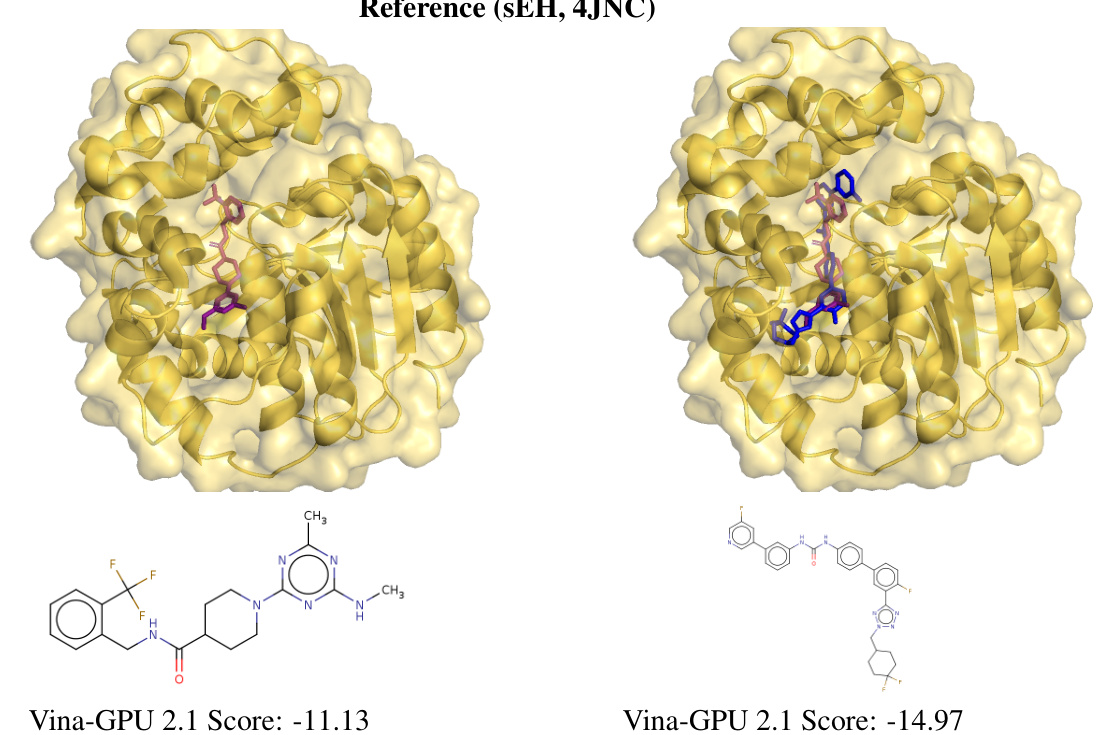

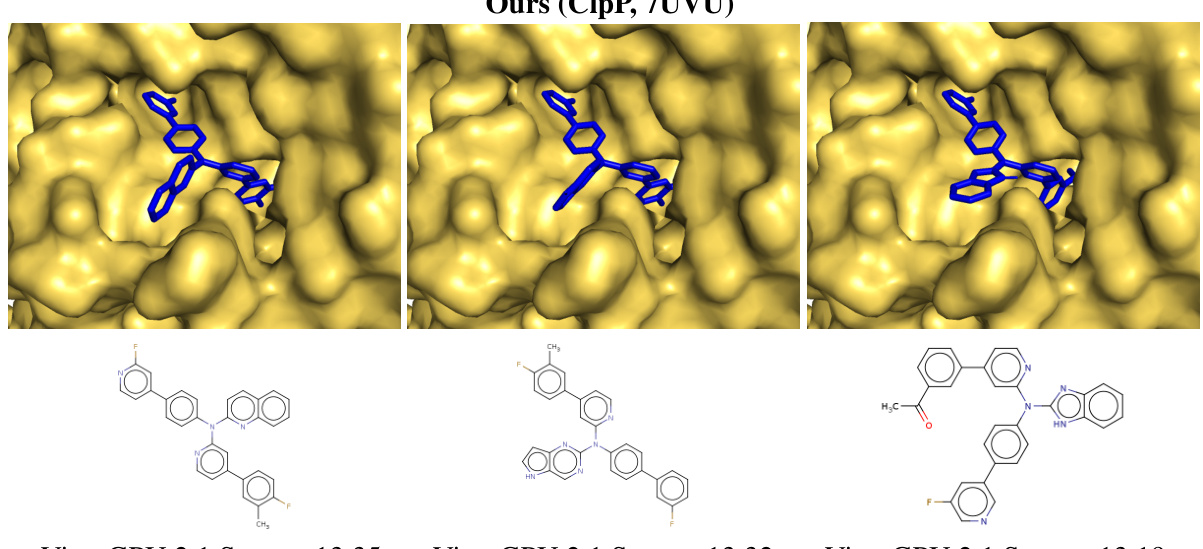

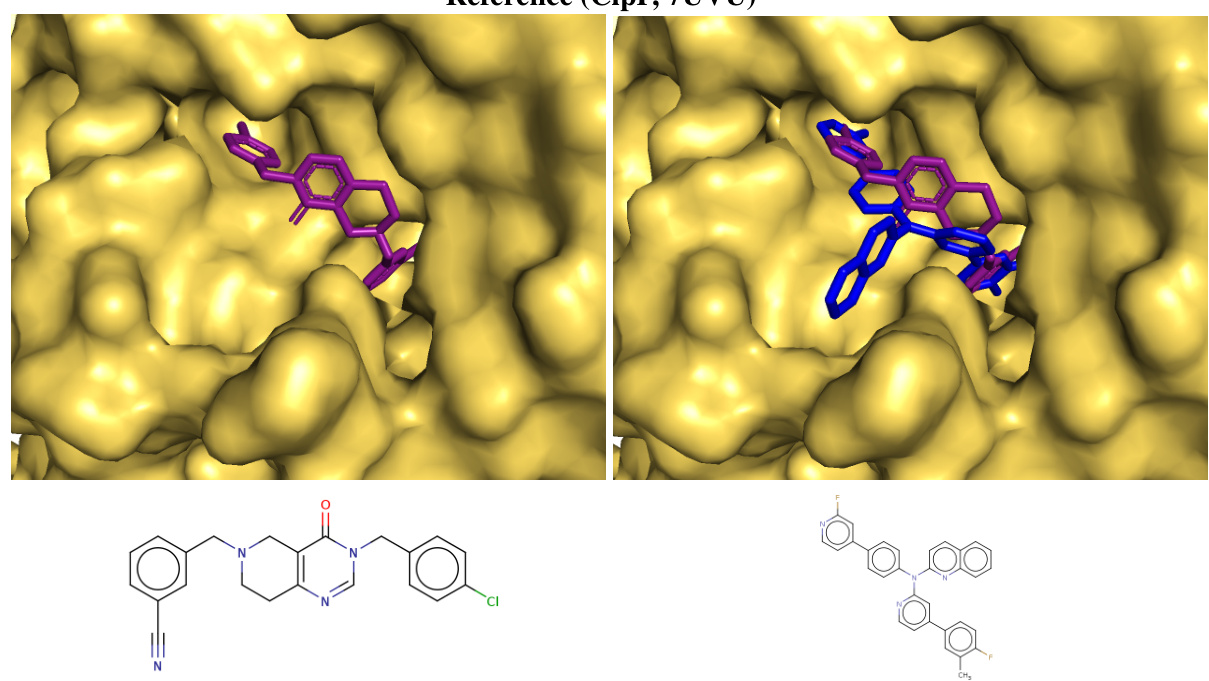

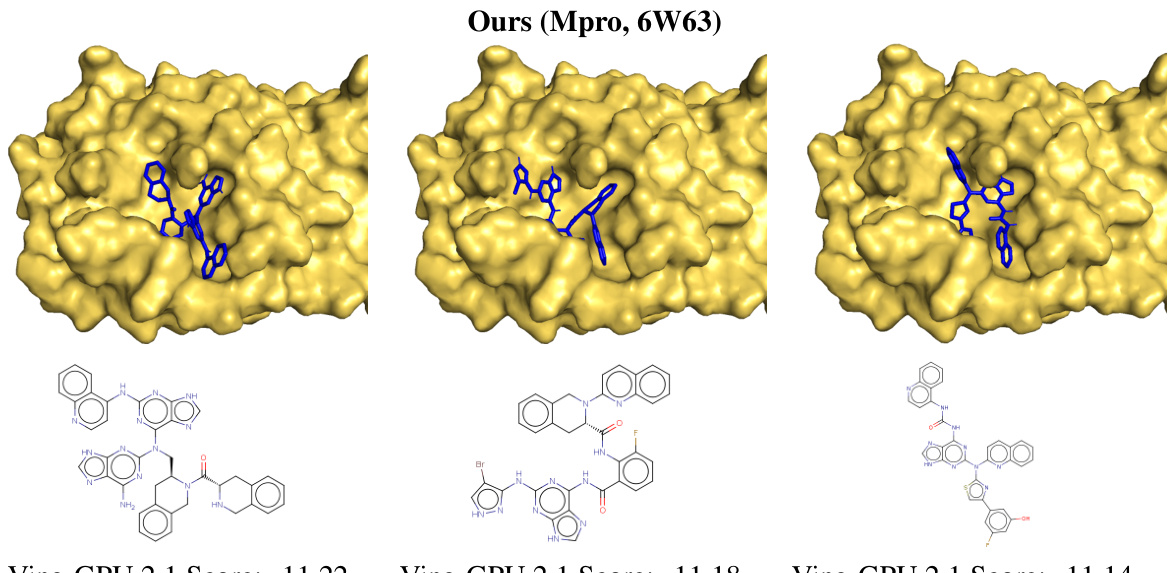

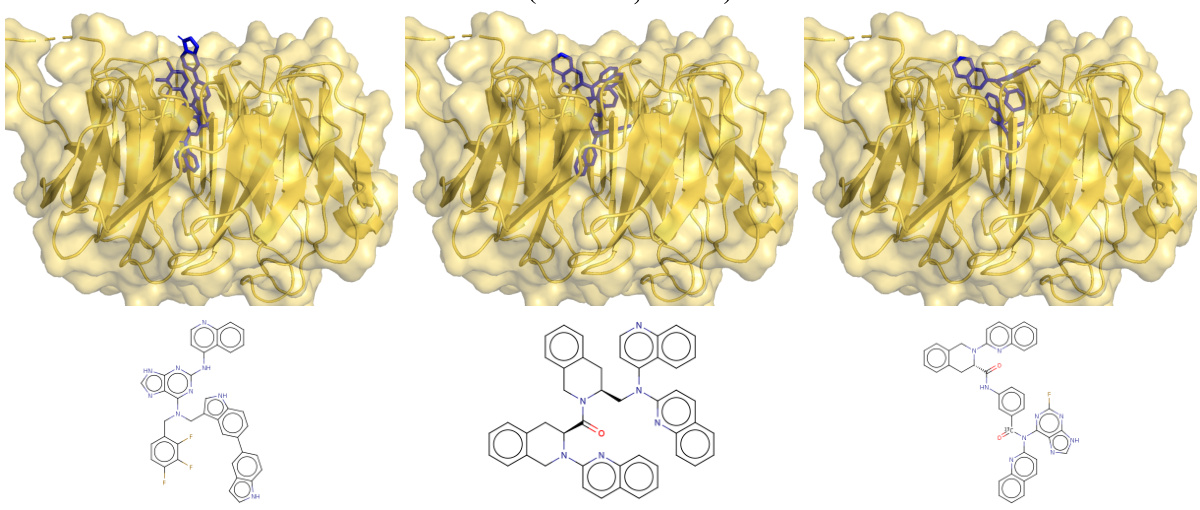

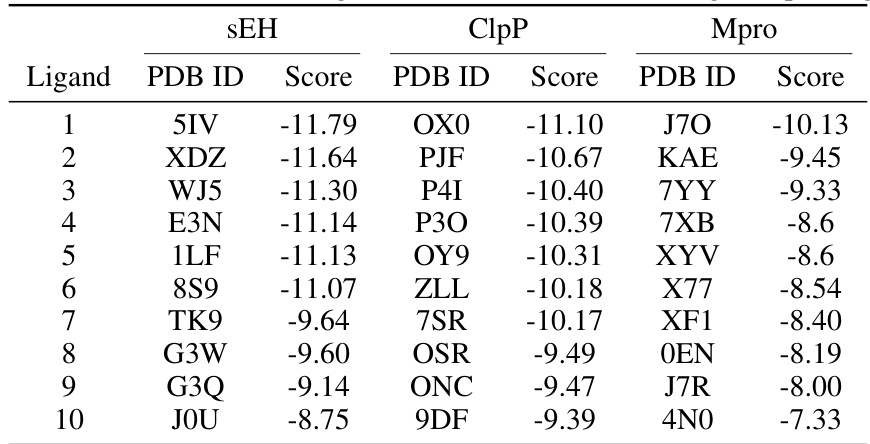

This figure shows the top-ranked ligands generated by Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) for three different protein targets: soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), Clp protease proteolytic subunit (ClpP), and SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro). The RGFN-generated ligands are shown in blue, while the known ligands from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) are shown in purple. The overlay demonstrates how well the RGFN-generated ligands fit into the binding pockets of these proteins, suggesting their potential as effective inhibitors.

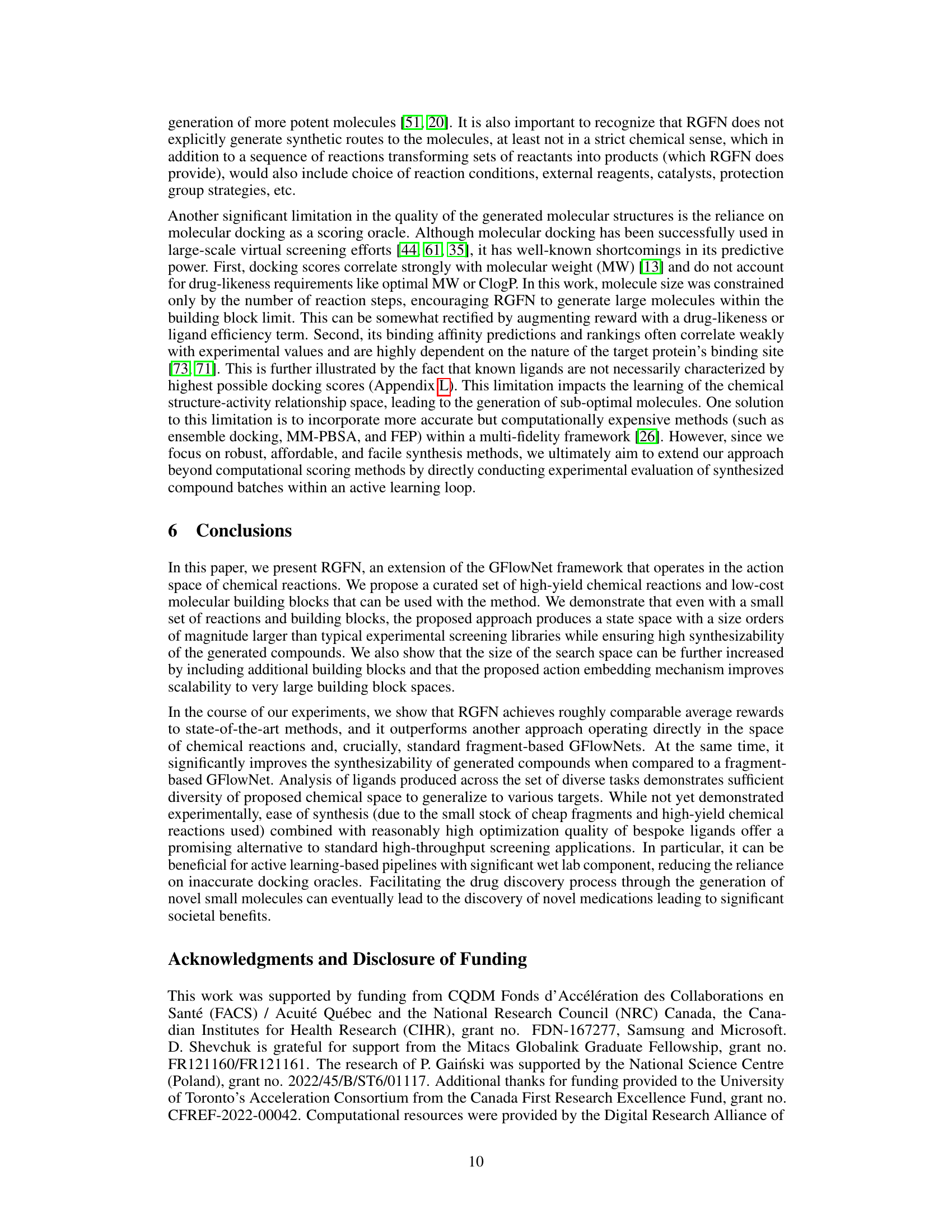

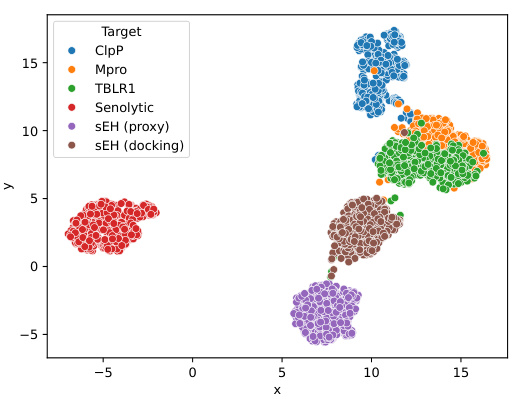

This figure is a UMAP plot visualizing the chemical structures of the top 500 molecules generated by the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) model for each of the six target proteins. The plot demonstrates that RGFN is capable of generating diverse molecules, with distinct clusters forming for each target, indicating that the generated molecules are not randomly distributed but rather show chemical structure similarity within each cluster and distinctiveness between the targets. Appendix G provides details about each target protein.

This figure illustrates the process of molecular generation using Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). It starts by selecting a building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant to perform an in-silico reaction. This process is repeated until a stop condition is met, and the final generated molecule is then evaluated by a reward function.

This figure illustrates the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) sampling process step-by-step. It starts by selecting an initial building block (reactant). Then, iteratively, a reaction template is chosen, followed by the selection of another reactant. An in silico reaction is performed using RDKit’s RunReactants, resulting in a set of possible product molecules. One of these products is selected, and the process repeats until a ‘stop’ action is selected, at which point the resulting molecule is evaluated using a reward function. This process simulates chemical reactions to generate molecules.

This figure illustrates the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) sampling process, showing how it iteratively selects building blocks, reactions, and reactants to build molecules. The process concludes when a stop action is selected, at which point the generated molecule is evaluated by a reward function.

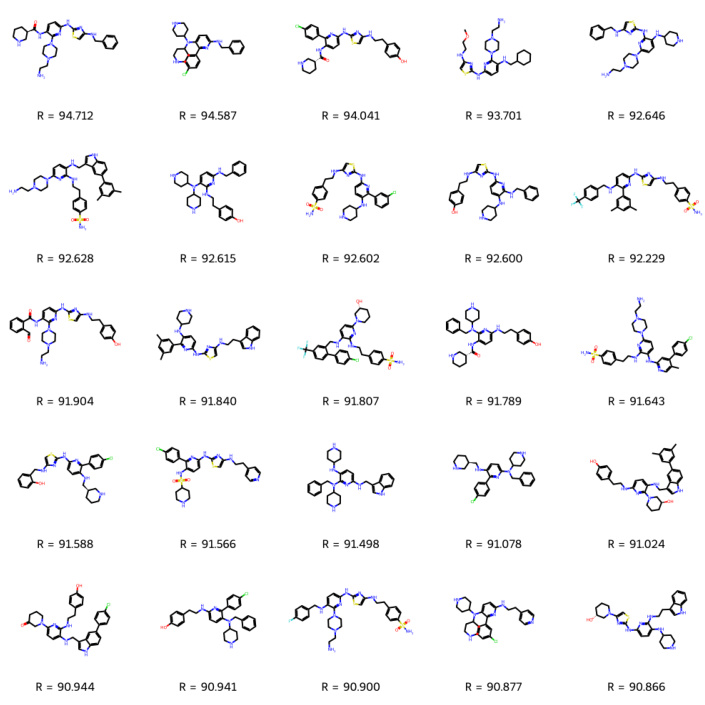

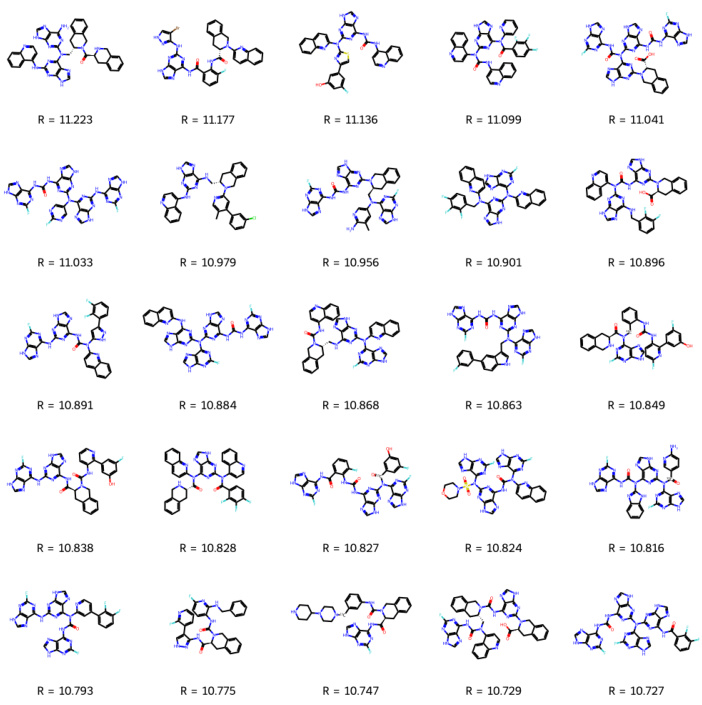

This figure shows the top 25 molecules predicted to bind to soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) by Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). These molecules were selected from the top 100 molecules generated by RGFN after filtering based on various criteria such as Tanimoto similarity, PoseBusters checks (to ensure physically valid poses), and Aggregation Advisor scores (to prevent aggregation). The figure visually presents the chemical structures of these top-scoring molecules, highlighting their potential as drug candidates. The ‘R’ values likely represent docking scores or other relevant metrics used for ranking.

This figure shows the top three generated ligand scaffolds for soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) in blue, compared to the reference ligand pose in purple (PDB ID: 1LF). The bottom right panel overlays the top-scoring generated ligand (blue) with the reference ligand (purple) to highlight the structural similarity and differences.

This figure compares the top three generated ligand scaffolds for soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) with a reference ligand. The generated ligands are shown in blue, while the reference ligand is shown in purple. The docking scores for each ligand are also provided. The image provides both a 3D representation of the ligand-protein complex and a 2D depiction of the ligand structure.

This figure shows the top-ranked docked poses of ligands generated by Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) for three different protein targets: soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), ClpP protease, and SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro). The RGFN-generated ligands are shown in blue, while the known ligands from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) are shown in purple. The overlay demonstrates how well the RGFN-generated ligands fit into the binding pockets of the target proteins.

This figure illustrates the step-by-step process of Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) in generating molecules. Starting with an initial building block, RGFN iteratively selects reactions and reactants, performs in-silico reactions using RDKit, and selects a resulting molecule. This process continues until a stop action is chosen, after which the generated molecule is evaluated using a reward function.

This figure shows the top three generated Mpro ligands, their docking poses, and a comparison to the reference ligand. The blue structures are the top three generated ligands, the purple is the reference ligand from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The overlay shows how well the generated ligands fit into the binding pocket compared to the reference ligand. The Vina GPU 2.1 scores are also provided.

This figure displays the top 25 molecules identified as binders to soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) after filtering from the top 100 molecules generated by the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) model. Filtering was performed to ensure the diversity, specificity, and conformer validity of the generated molecules. The filtering steps involved checking for Tanimoto similarity to other molecules, running docking poses through PoseBusters to check for validity, and checking for aggregation using UCSF’s Aggregation Advisor.

This figure shows the top-ranked docked poses of the generated molecules from Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) compared to the known ligands for each of three protein targets: sEH, ClpP, and Mpro. The generated molecules (blue) are overlaid on the known ligand poses (purple) to highlight the similarities and differences in their binding modes.

This box plot displays the distribution of the maximum Tanimoto similarity scores for each target protein (sEH, ClpP, Mpro). The Tanimoto similarity measures the structural similarity between generated molecules and known ligands (from PDB). Each box represents the interquartile range (IQR), the median (line inside the box), and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points not considered outliers. The circles represent outliers. This figure helps to assess the diversity of the molecules generated by the model compared to existing known ligands for each target.

The figure shows the estimated state space size of the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) model as the maximum number of reactions allowed increases. Two versions of RGFN are compared: one using 350 hand-picked inexpensive building blocks, and another using a significantly larger set of 8350 building blocks (including 8000 randomly selected Enamine blocks). The size of the Enamine REAL database (6.5 billion compounds) is included for comparison to illustrate the magnitude of the state space achieved by RGFN.

This figure illustrates the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) sampling process. Starting with an initial building block, RGFN iteratively selects a reaction and a reactant to simulate a chemical reaction using RDKit. The process continues until a stop action is selected, producing a final molecule that is then scored using a reward function.

This figure illustrates the reaction-based molecule generation process using Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). It starts by selecting a building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant to perform an in-silico reaction, yielding a new molecule. This process continues until a termination condition is met, at which point the final molecule is evaluated using a reward function.

This figure illustrates the process of molecular generation using Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). It starts by selecting an initial building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant to perform an in silico reaction using RDKit. This process continues until a stop action is selected, resulting in a final molecule that is evaluated using a reward function.

This figure illustrates the process of molecular generation using Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). It starts by selecting an initial building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant to perform an in silico reaction. The process continues until a stop action is selected, producing a final molecule which is then evaluated.

This figure shows the estimated state space size of Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) as a function of the maximum number of reactions allowed in the generation process. Two variants of RGFN are compared: one with 350 hand-picked inexpensive building blocks, and another with an additional 8,000 randomly selected building blocks from Enamine. The state space size of Enamine REAL, a large commercially available database of compounds, is also shown for comparison. The results indicate that RGFN, even with a relatively small set of reactions and building blocks, can generate a search space many orders of magnitude larger than existing screening libraries.

This figure illustrates the process of molecular generation using Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). It starts by selecting a building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant, simulates the reaction in silico, and chooses a resulting molecule. This process repeats until a stop action is selected, at which point the resulting molecule is evaluated.

This figure illustrates the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) sampling process step by step. It starts by selecting an initial building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant, performs an in-silico reaction using RDKit, selects a product molecule from the possible outcomes, and repeats until a termination condition is met. The final molecule is then evaluated using a reward function.

This figure illustrates the step-by-step process of molecular generation using Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). It starts by selecting an initial building block, followed by iteratively selecting a reaction and another reactant. The reaction is then performed in silico, and a product is chosen. This cycle continues until a stop action is triggered, at which point the final molecule is evaluated using a reward function.

This figure illustrates the step-by-step process of Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) in generating molecules. It starts by selecting an initial building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant, performs an in-silico reaction using RDKit, selects one of the resulting molecules, and repeats this cycle until a stop action is selected. The final molecule is then evaluated using a reward function.

This figure illustrates the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) sampling process. It starts by selecting an initial building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and a reactant, performs an in-silico reaction using RDKit, chooses a product molecule, and repeats until a stop condition is met. The final molecule is then evaluated using a reward function.

This figure illustrates the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) sampling process. It starts by selecting an initial building block, then iteratively selects a reaction and another reactant, simulates the reaction in silico, and selects a resulting molecule. This process continues until a stop action is chosen, at which point the final molecule is evaluated using a reward function.

This figure shows the estimated state space size of the Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) model as the maximum number of reactions allowed increases. Two versions of RGFN are compared: one with 350 hand-picked building blocks and another with 8350 building blocks (including 8000 from Enamine). The state space size of RGFN is significantly larger than that of the Enamine REAL database, even when using the smaller set of 350 building blocks. The increase in state space size demonstrates the scalability of RGFN to larger fragment libraries.

This figure shows the estimated size of the search space explored by Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) as the maximum number of allowed reactions increases. The graph compares two versions of RGFN: one using a curated set of 350 inexpensive building blocks, and another incorporating an additional 8,000 randomly selected blocks from the Enamine database. For context, the size of the Enamine REAL database (containing 6.5 billion compounds) is also plotted. The figure illustrates that RGFN, even with a relatively small set of building blocks, can explore an enormous chemical space, exceeding the size of existing libraries by orders of magnitude.

This figure shows the estimated size of the chemical space explored by Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN) as a function of the maximum number of reactions allowed in the synthesis pathway. Two variants of RGFN are compared: one using 350 curated, inexpensive building blocks, and another using 8350 building blocks (350 curated + 8000 randomly selected from Enamine). The size of the Enamine REAL database (6.5 billion compounds) is included for comparison, demonstrating that RGFN significantly expands the searchable chemical space, even with relatively few building blocks and reactions.

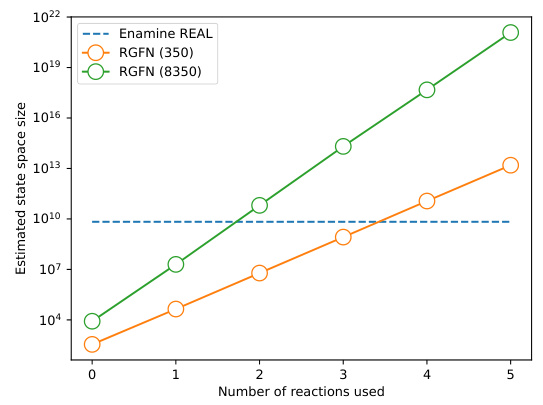

More on tables

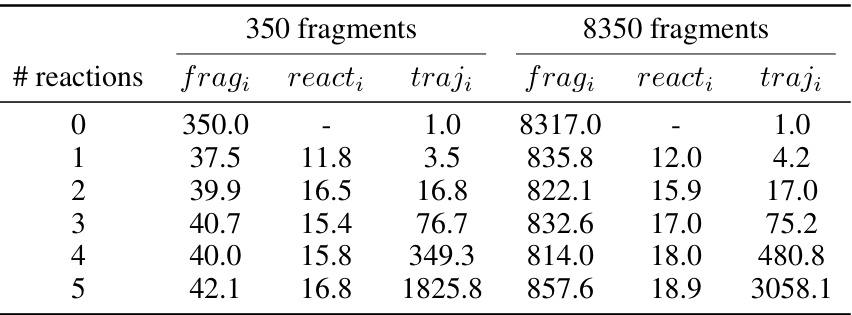

This table presents the experimentally derived average values for the number of valid fragments, reactions, and trajectories observed during the training of Reaction-GFlowNet (RGFN). The data is broken down by the number of reactions used in a given trajectory, and separately for two different sizes of fragment libraries (350 and 8350 fragments). This data is useful to understand the size of the search space explored by RGFN and how it scales with library size.

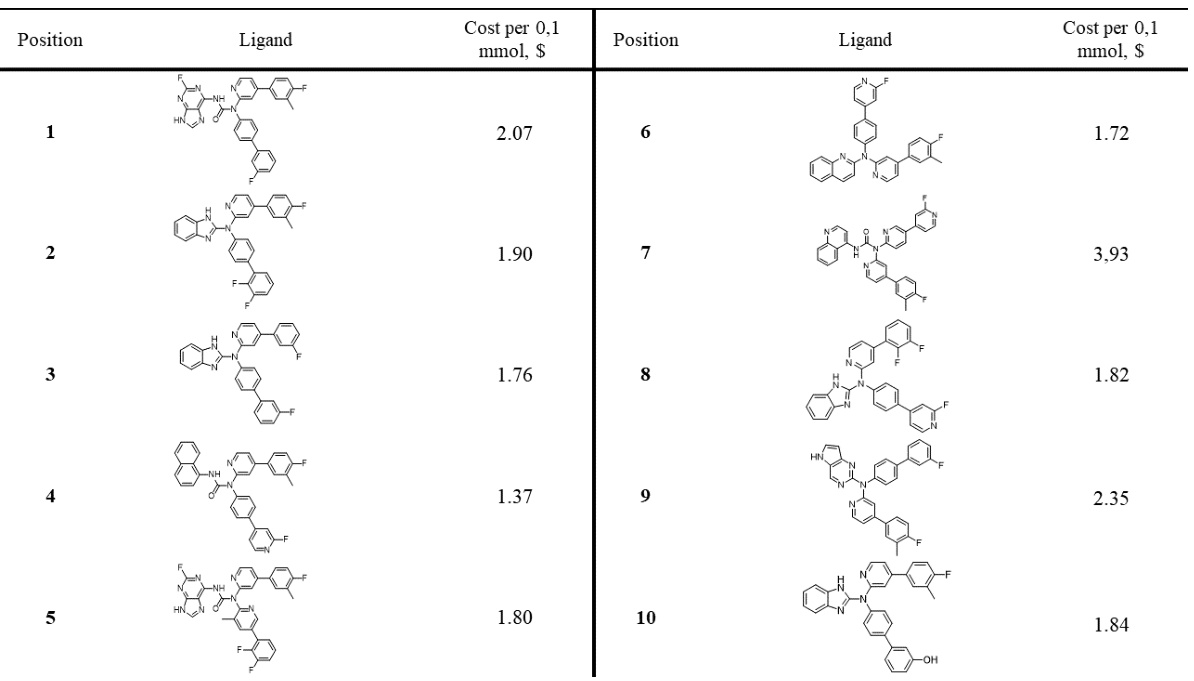

This table presents a comparison of several state-of-the-art methods for molecular generation regarding synthesizability. For each method and target (sEH, Seno., ClpP, DRD2), the table shows the average molecular weight, QED score (drug-likeness), SAScore (synthetic accessibility score), and the average number of molecules for which a valid retrosynthetic pathway was found using AiZynthFinder. Lower molecular weight and higher QED and AiZynth scores indicate better synthesizability.

This table presents a comparison of several metrics related to the synthesizability of the top-performing molecules generated by different methods across four different tasks (sEH proxy, senolytic proxy, DRD2 proxy, and ClpP docking). Metrics include molecular weight, quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility score (SAScore), and the average number of molecules in a valid retrosynthesis pathway found by AiZynthFinder. Lower molecular weight and higher QED and AiZynth scores generally indicate better synthesizability, while lower SAScores suggest higher ease of synthesis. The data illustrates how RGFN balances good performance on the relevant tasks with a high likelihood of synthesizability.

This table presents a comparison of different molecular generation methods across various metrics related to synthesizability and quality of generated molecules. The metrics include molecular weight, quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility score (SAScore), and the average number of steps in a retrosynthetic pathway (AiZynth). The results are presented for the top-k generated molecules for each method and across four different tasks (sEH proxy, senolytic proxy, DRD2 proxy, and ClpP docking).

This table shows the average values of several metrics related to the synthesizability of the top-k generated molecules for each method across four different tasks. These metrics include molecular weight, quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility score (SAScore), and the average number of molecules for which a valid retrosynthesis pathway was found using AiZynthFinder. Lower molecular weight and higher QED scores are desirable. Lower SAScores and higher AiZynthFinder scores indicate better synthesizability. The table compares several different methods to generate molecules, highlighting the tradeoffs between synthesizability and other properties like docking scores and drug-likeness.

Full paper#