TL;DR#

Digital platforms wield significant power, influencing online user behavior. Existing antitrust tools struggle to address this, and there’s currently no universally accepted technical framework to quantify this influence. The paper addresses this gap by focusing on the concept of ‘performative power’—a platform’s ability to causally affect user behavior via algorithmic changes.

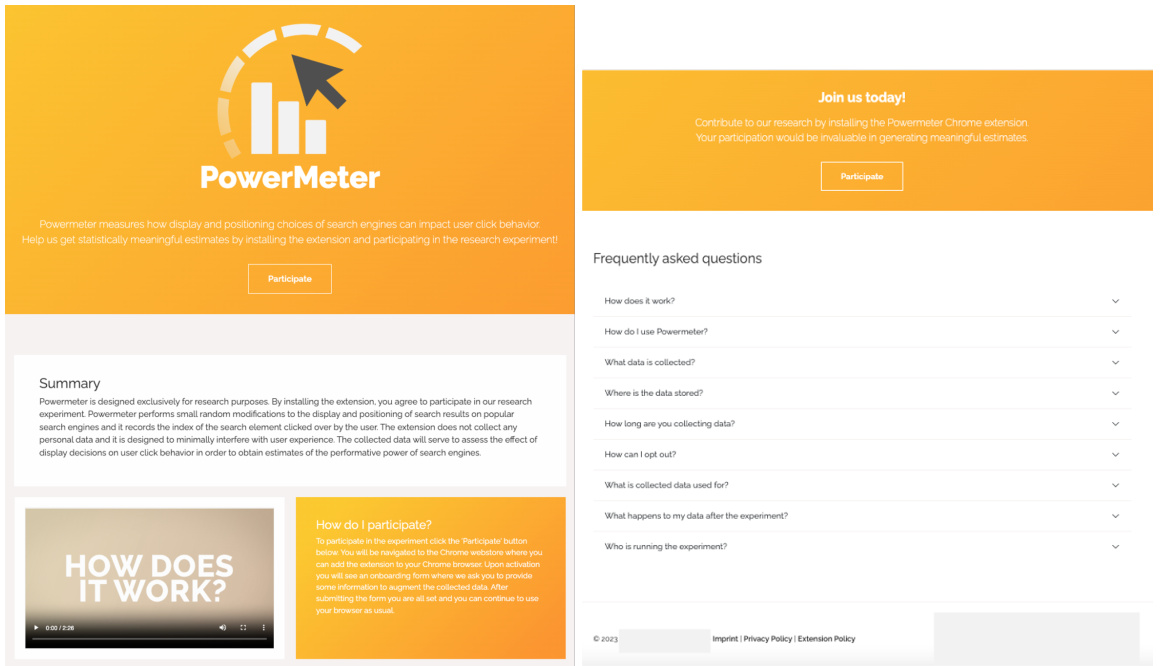

The research introduces Powermeter, a browser extension that runs randomized experiments to measure the causal effects of altered search result ordering on user clicks. The study analyzes tens of thousands of clicks across major search engines, revealing a strong causal link between content positioning and click-through rates. This quantitative evidence provides a lower bound on performative power, demonstrating the potential of the method to support antitrust investigations and providing crucial insights into digital market dynamics.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers studying digital market power and antitrust. It provides a novel method for measuring performative power, bridging the gap between theoretical concepts and practical applications. The findings are directly relevant to ongoing policy debates and offer new avenues for quantitative investigations into digital platform influence. This methodology advances our ability to quantify the causal effect of algorithmic changes on user behavior, with broad implications for competition law and digital market regulation.

Visual Insights#

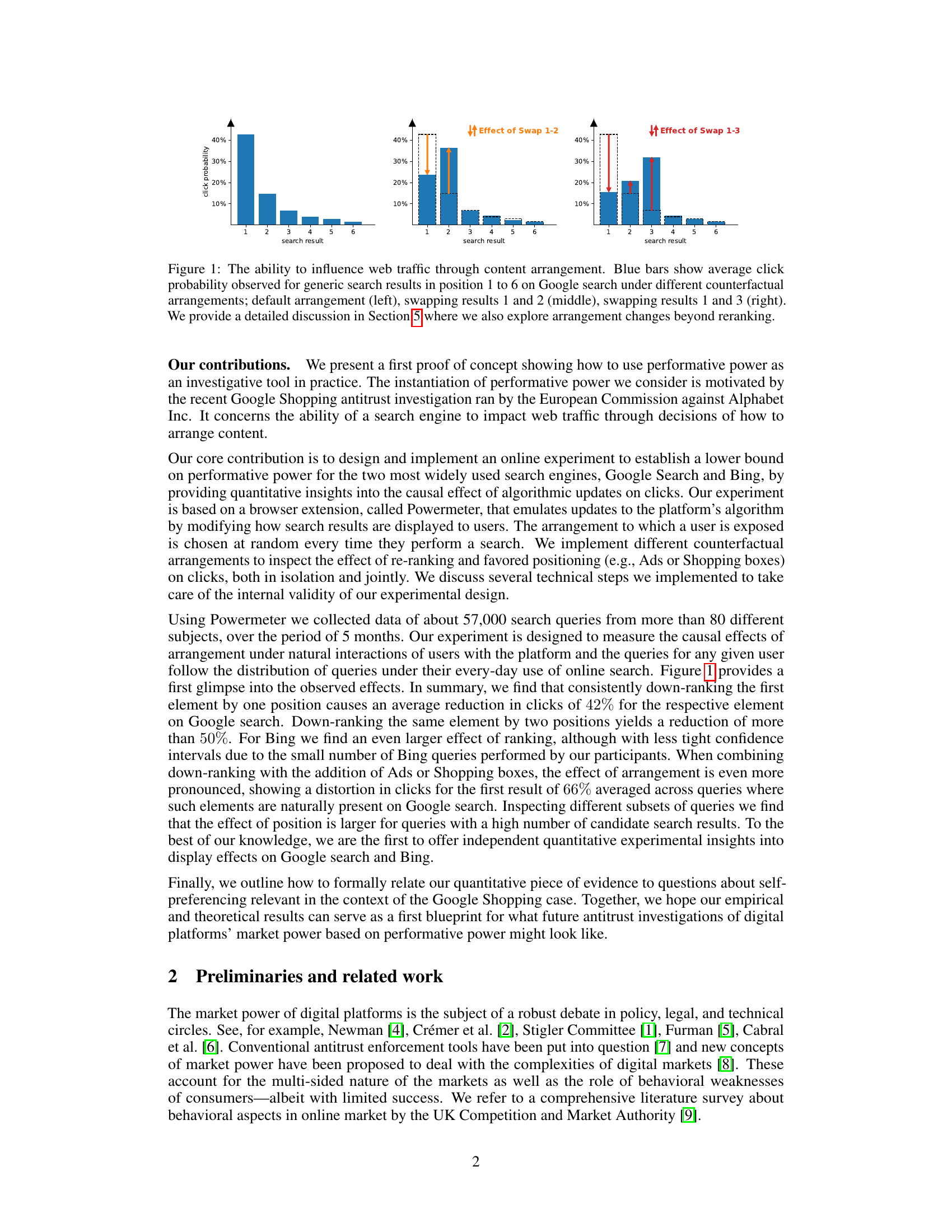

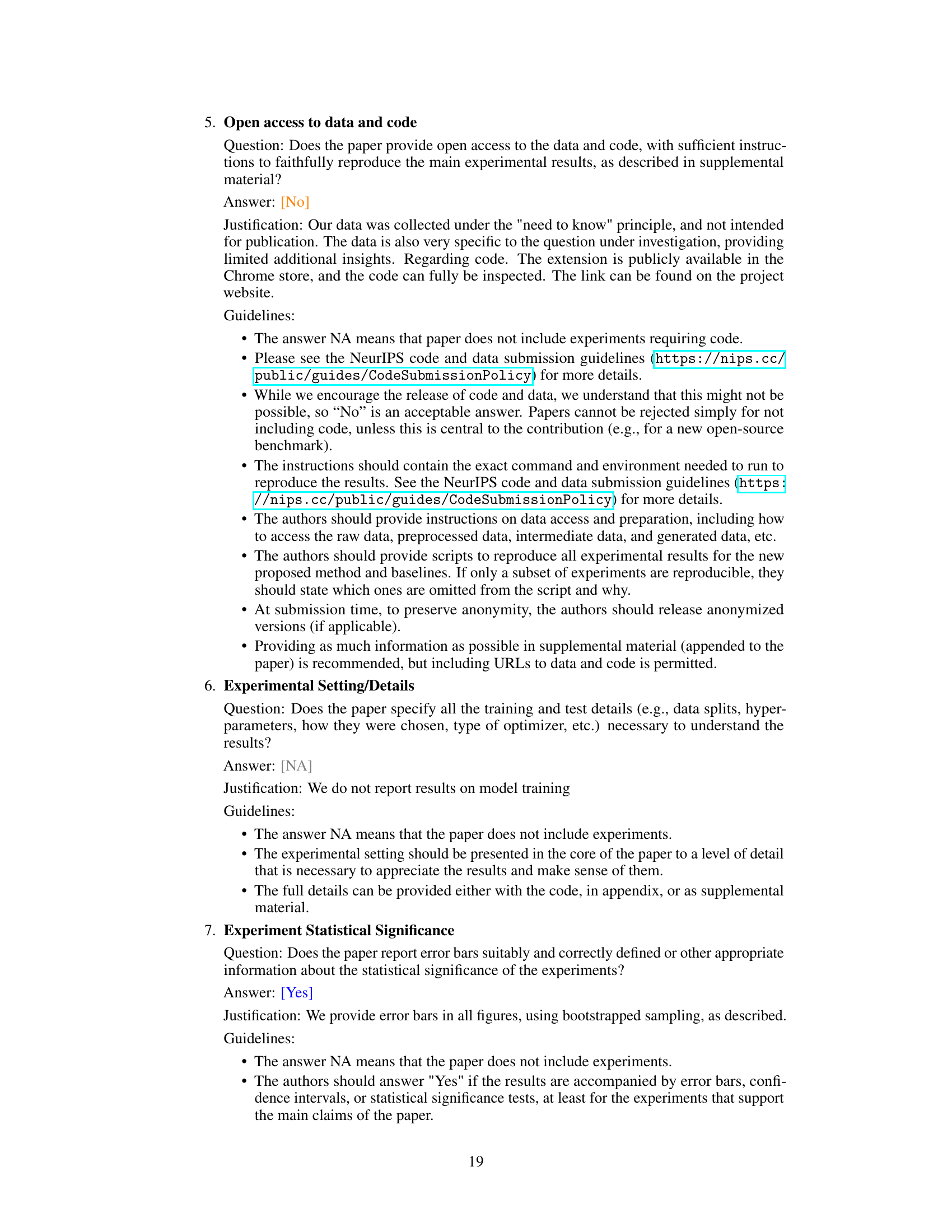

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of search result reordering on click-through rates (CTR). Three scenarios are presented: 1. Default Arrangement: Shows the baseline CTR for each search result position (1-6). 2. Swap 1-2: Illustrates the CTR change when the top two results are swapped. 3. Swap 1-3: Shows the CTR change when the top result is swapped with the third result. The blue bars represent the average click probability for each position under each arrangement. The significant differences in CTR between the default and swapped arrangements highlight how search engines can influence user behavior through result positioning. Section 5 provides further detail.

read the caption

Figure 1: The ability to influence web traffic through content arrangement. Blue bars show average click probability observed for generic search results in position 1 to 6 on Google search under different counterfactual arrangements; default arrangement (left), swapping results 1 and 2 (middle), swapping results 1 and 3 (right). We provide a detailed discussion in Section 5 where we also explore arrangement changes beyond reranking.

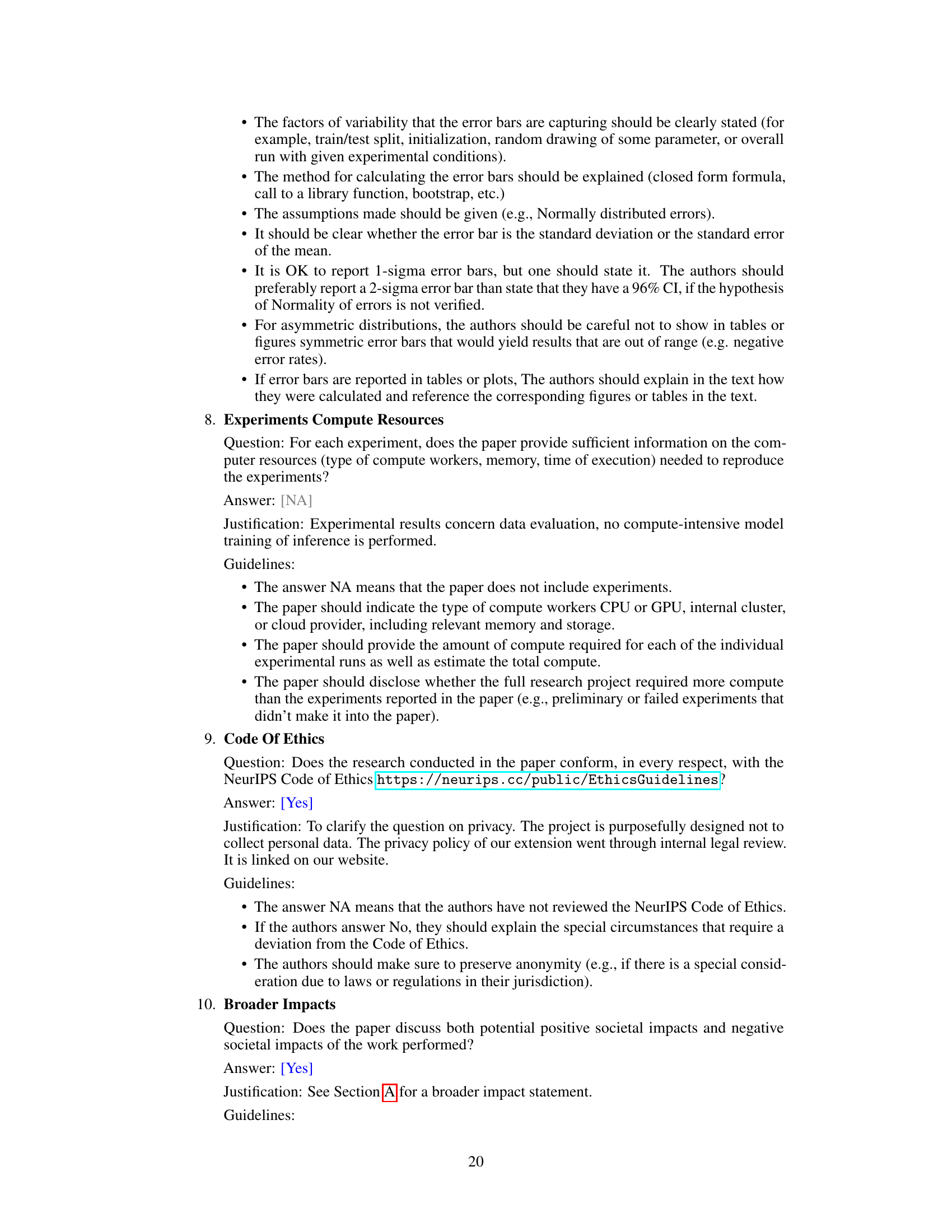

🔼 This table describes the different experimental arrangements used in the study. The ‘control’ arrangement shows the default search results. The other arrangements involve swapping the positions of certain search results or hiding elements like Ads and Shopping boxes, allowing researchers to measure the causal effect of these changes on user clicks. The table is crucial for understanding the methodology used to isolate the effects of different algorithmic manipulations on user behavior.

read the caption

Table 1: Counterfactual content arrangements implemented by Powermeter as part of the RCT.

In-depth insights#

Performative Power#

The concept of ‘Performative Power’ in the context of online search engines is a novel approach to quantifying the influence of algorithmic choices on user behavior and market outcomes. It moves beyond traditional antitrust frameworks, which often struggle with the complexities of digital markets, by directly measuring the causal effect of algorithmic actions. The core idea is that a platform’s ability to influence user clicks, and thus web traffic, is a direct measure of its power. The paper operationalizes this concept through a randomized controlled trial (RCT) using a browser extension that emulates algorithmic changes, enabling researchers to precisely quantify the causal impact on click-through rates. This approach provides a robust and quantitative way to evaluate performative power, filling a gap in existing methodologies and offering a powerful tool for investigations into the economic power of digital platforms, particularly in antitrust cases. The empirical findings highlight the significant influence of even minor algorithmic changes on user behavior, underscoring the performative power of major online search engines. The study’s rigorous approach helps to establish a causal link between algorithmic decisions and market outcomes, potentially contributing to more effective antitrust enforcement and policymaking.

RCT Experiment#

A hypothetical “RCT Experiment” section in a research paper would detail the rigorous design and execution of a randomized controlled trial. This would involve clearly defining the treatment and control groups, explaining the randomization method used to assign participants to each group, and describing the procedures for data collection and analysis. A strong RCT would acknowledge potential confounding variables and detail efforts to mitigate their effects. Crucially, the section would discuss sample size calculations to ensure sufficient statistical power to detect meaningful differences between groups and would report results with appropriate measures of statistical significance, such as confidence intervals or p-values. Furthermore, a complete RCT description should include a discussion of any limitations of the study, ensuring transparency and replicability for other researchers.

Powermeter Tool#

The Powermeter tool, a Chrome browser extension, is a pivotal element in the study’s methodology. Its design is crucial, allowing researchers to conduct randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on major search engines without direct access to or modification of the platforms’ algorithms. Powermeter’s unobtrusive nature, emulating algorithmic updates by subtly changing the display of search results, is essential for maintaining the natural user experience and ensuring the internal validity of the experiment. The tool collects data on user clicks, recording both the click events and relevant contextual information about the search result page. This capability allows for the quantitative analysis of how changes in content arrangement impact user behavior, providing robust causal evidence. The design’s attention to privacy, anonymizing user data, ensures ethical compliance and protects user information. This approach represents a significant advancement, enabling rigorous measurement of performative power in a real-world setting.

Algorithmic Bias#

Algorithmic bias in online search is a critical concern, as search engines’ ranking algorithms can perpetuate and amplify existing societal biases. Implicit biases in data used to train these algorithms, such as underrepresentation of certain demographics, can lead to skewed results. This can manifest in several ways, including biased search result ordering, where content reflecting particular viewpoints or favoring specific groups appears disproportionately higher in search results, even when not objectively superior. Furthermore, algorithms may also exhibit filter bubbles and echo chambers, reinforcing pre-existing beliefs and potentially limiting exposure to diverse perspectives. Mitigating algorithmic bias requires a multifaceted approach involving careful data curation, algorithm design improvements, and transparency regarding how algorithms function. It also requires an ongoing assessment of the societal impact of algorithms. The paper’s experiments contribute to understanding the magnitude of the impact, but also highlight the complexity and subtlety of measuring and addressing these biases.

Future of Antitrust#

The future of antitrust in the digital age necessitates a paradigm shift from traditional frameworks. The rise of performative power, where algorithms shape market outcomes, demands novel measurement and enforcement tools. Causal inference and experimental design, as demonstrated in the paper’s methodology, will be crucial to establish clear links between algorithmic actions and their impact on competition. This includes addressing the complex interplay between algorithmic biases, user behavior, and market dynamics. Data privacy and the challenges of obtaining comprehensive data will remain significant hurdles, thus emphasizing the need for innovative data collection and analysis techniques, potentially including the use of synthetic data or novel experimental methods. Ultimately, international collaboration and a harmonization of legal approaches will be essential to address the global scale of these challenges.

More visual insights#

More on figures

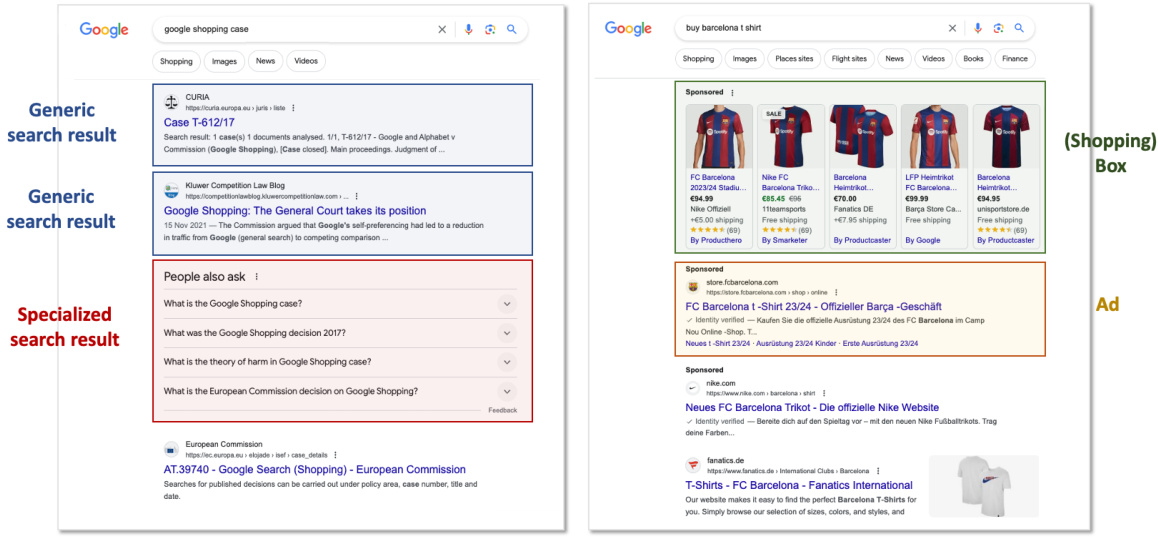

🔼 This figure shows two screenshots of Google Search results pages for the query ‘buy barcelona t-shirt’. The left screenshot shows the default arrangement, while the right screenshot shows a modified arrangement with Ads and a Shopping box. The figure highlights the different elements present on the Google search results page, including generic search results, specialized search results, Ads, and a Shopping box, to illustrate the various elements considered in their experiment.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of different elements on the Google search website.

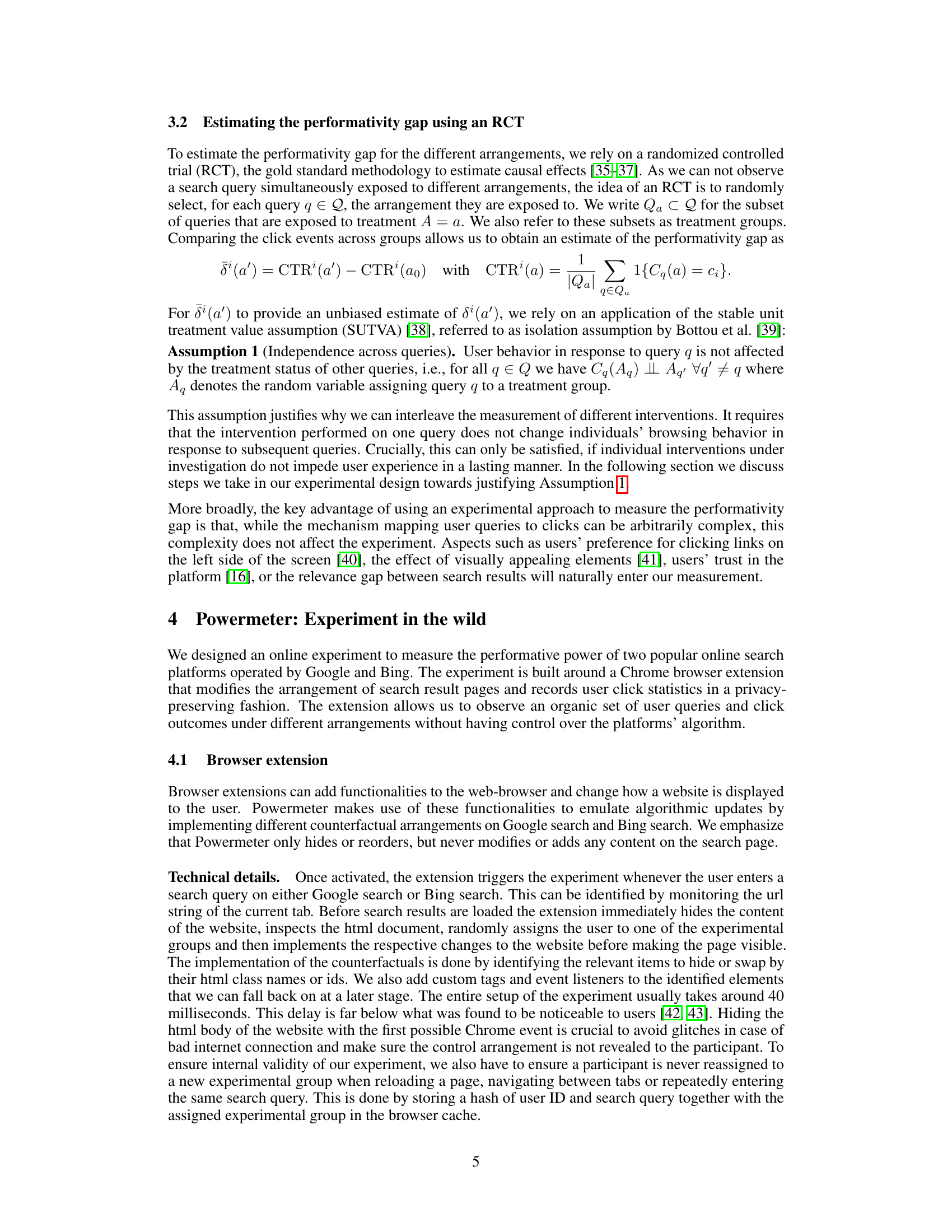

🔼 This figure visualizes the click-through rate for each of the top 6 search results under different arrangements. The left panels show the results for Google search, while the right panels are for Bing search. Each panel has three subplots, showing results for three different arrangements: swapping the first two results, the first and the third, and the second and the third. The bottom row plots the performativity gap, indicating the difference in click-through rates between each arrangement and the control arrangement. The results show a substantial impact of reordering search results on click-through rates, especially for the top-ranked result.

read the caption

Figure 3: Click through rate and performativity gap for general search results c1 to c6 under the counterfactual arrangements a1, a2, a3 for Google and the counterfactual arrangement a1 for Bing, compared to the control arrangement a0 (in blue).

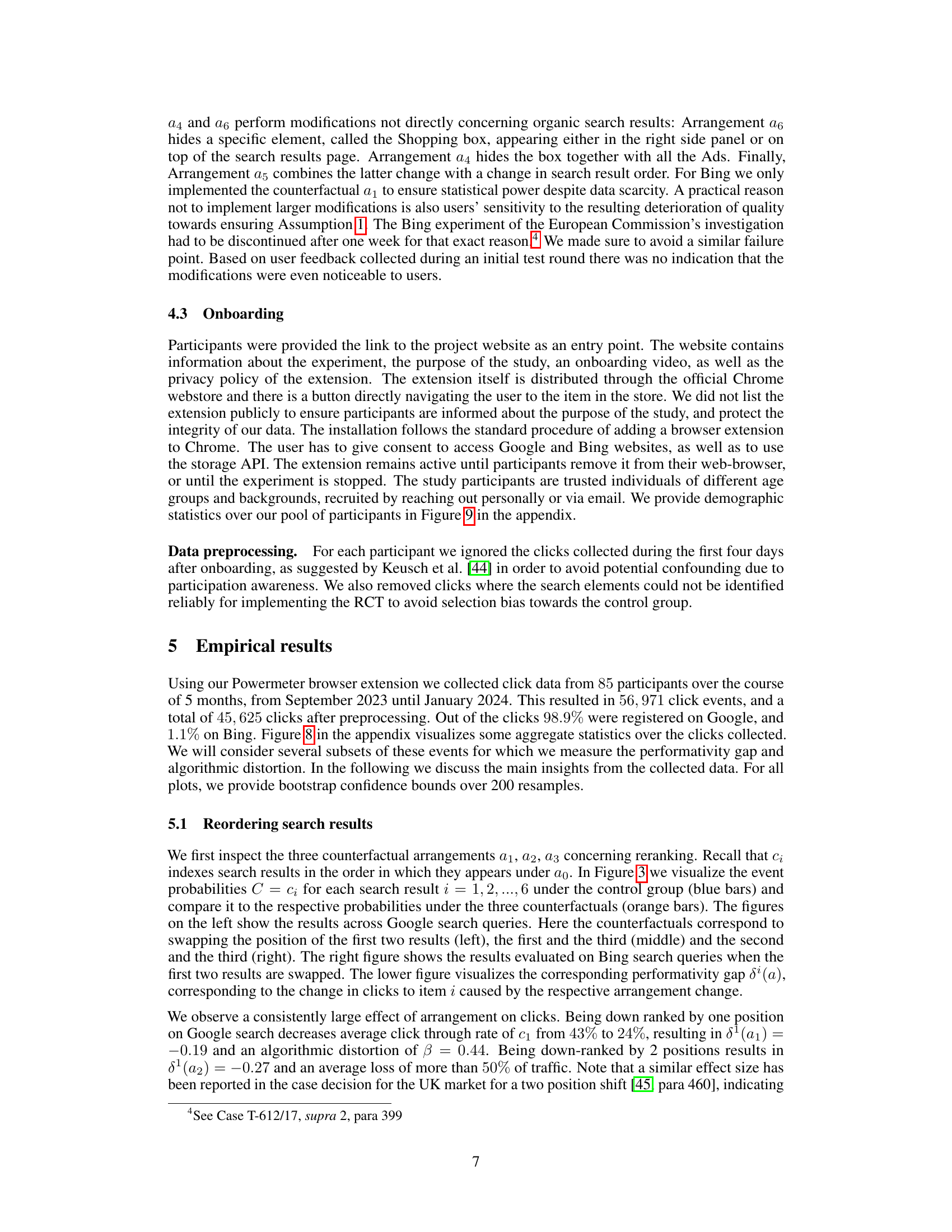

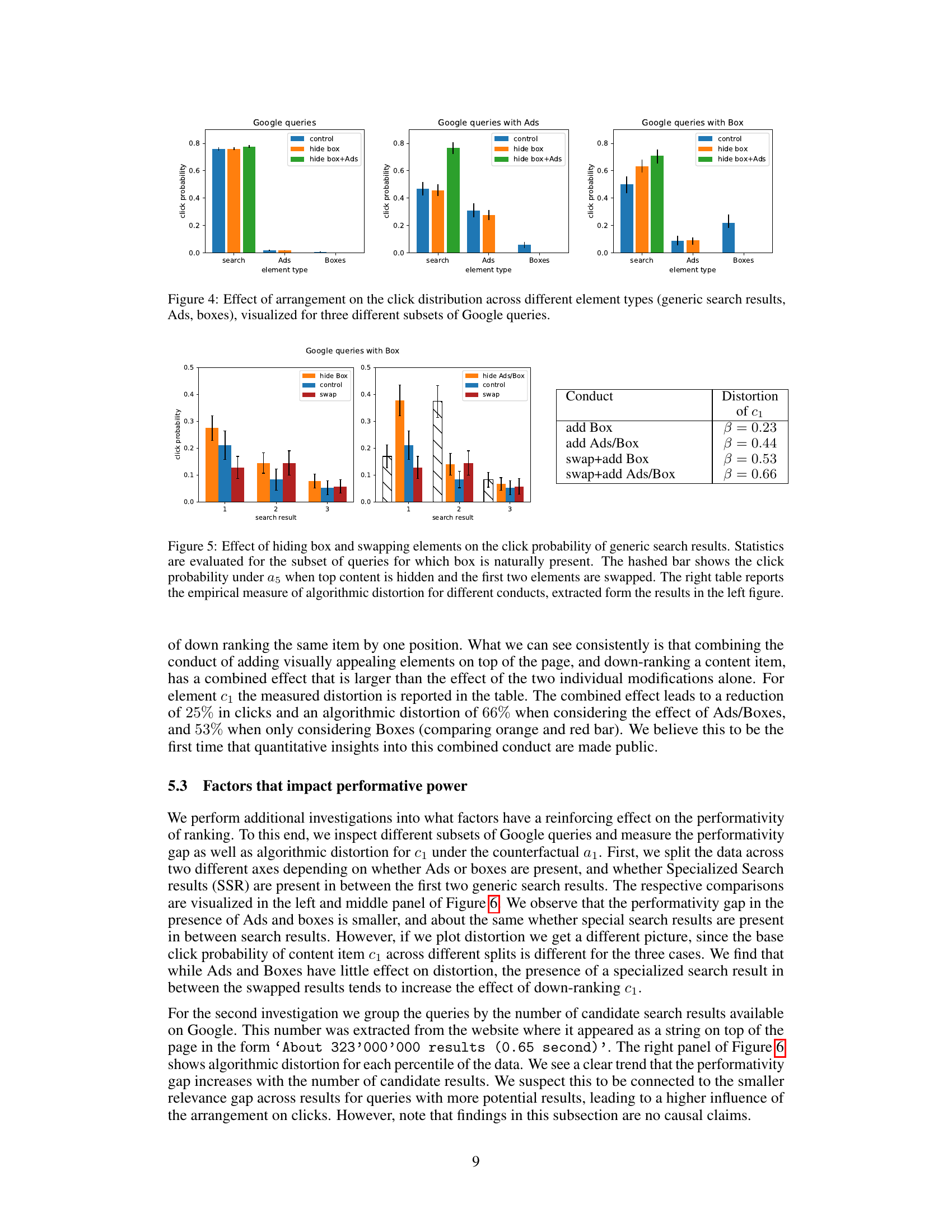

🔼 This figure shows the effect of hiding ads and shopping boxes on click distribution across different element types for Google search queries. It’s broken down into three panels: all queries, queries with ads, and queries with boxes. Each panel shows a bar chart comparing the click probabilities for generic search results, ads, and boxes under three conditions: control (no changes), hiding the box, and hiding both the box and ads. The data reveals how the removal of these elements affects the distribution of user clicks, highlighting the impact of visual prominence on user behavior.

read the caption

Figure 4: Effect of arrangement on the click distribution across different element types (generic search results, Ads, boxes), visualized for three different subsets of Google queries.

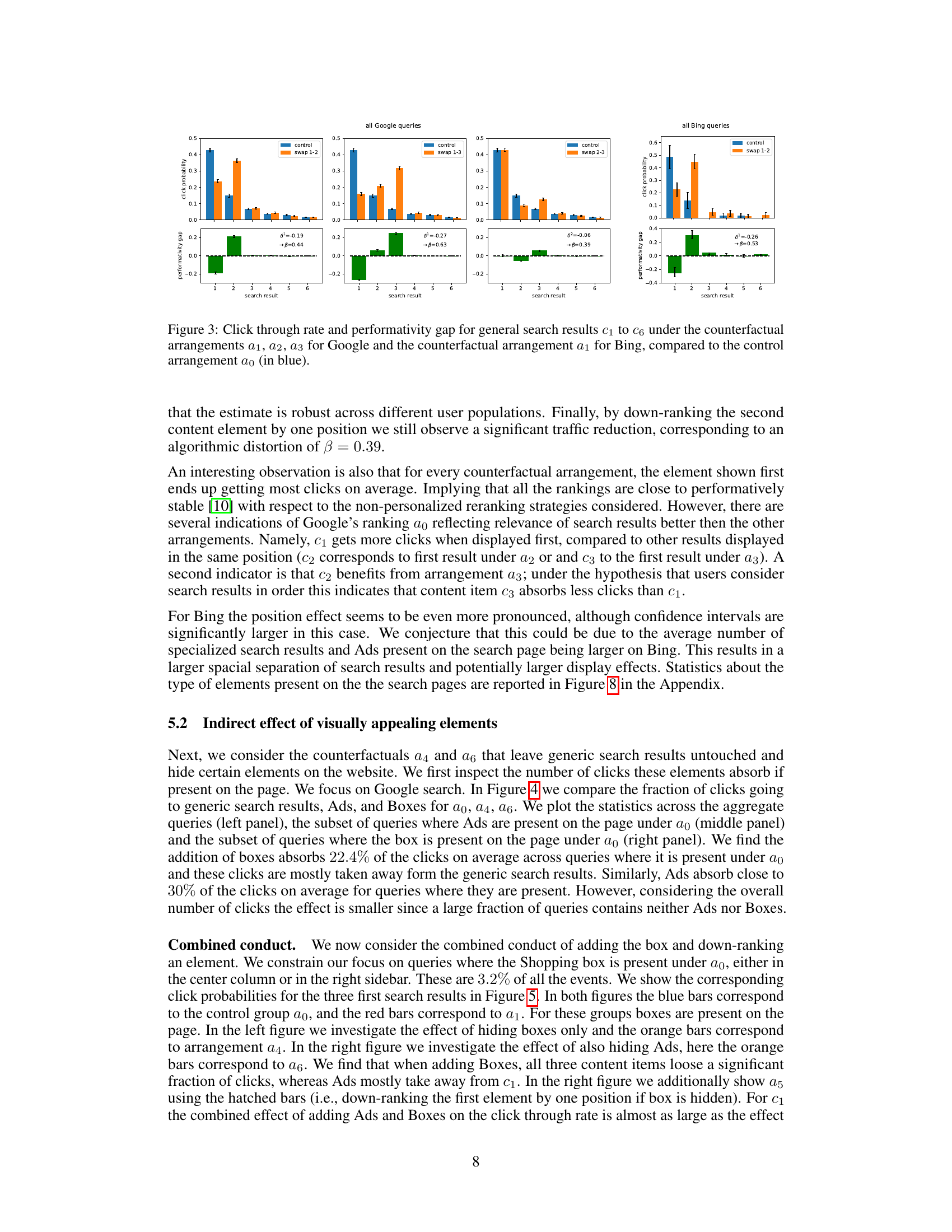

🔼 This figure shows the effect of hiding the shopping box and swapping the positions of the top search results on click probabilities. The left panel illustrates the click probabilities for the top three search results under four different conditions: a control group (no changes), hiding only the shopping box, hiding both ads and the box, and a combination of swapping the first two results and hiding the ads/box. The right panel presents a table summarizing the algorithmic distortion for each of these conditions. The results demonstrate that hiding the shopping box and/or ads significantly alters click patterns, often more so when combined with result reordering. The data is a subset of queries where the shopping box was present in the default arrangement.

read the caption

Figure 5: Effect of hiding box and swapping elements on the click probability of generic search results. Statistics are evaluated for the subset of queries for which box is naturally present. The hashed bar shows the click probability under a5 when top content is hidden and the first two elements are swapped. The right table reports the empirical measure of algorithmic distortion for different conducts, extracted form the results in the left figure.

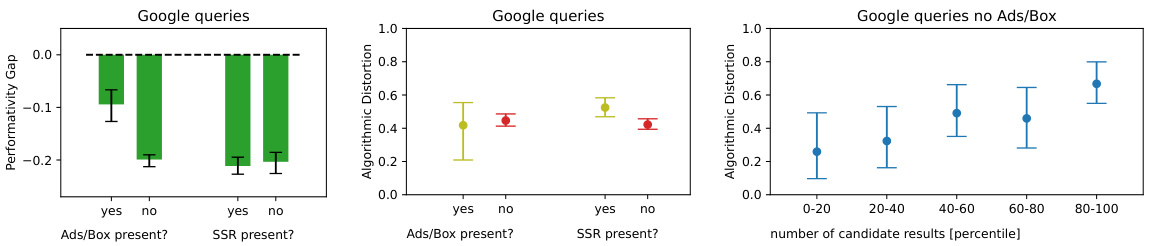

🔼 This figure presents three subplots visualizing the effects of different factors on the performativity gap and algorithmic distortion for the first search result (c1) when its position is swapped with the second result (counterfactual arrangement a1). The left subplot shows the performativity gap (change in click-through rate) when comparing queries with and without Ads/Boxes and queries with and without Specialized Search Results (SSRs) present between the top two organic search results. The middle subplot shows the algorithmic distortion (performativity gap relative to the base click-through rate) for the same comparison. The right subplot shows the algorithmic distortion as a function of the number of candidate search results (quantiles). Overall, it indicates that the presence of Ads/Boxes and SSRs can influence the magnitude of the effect, with larger effects observed for queries with many candidate search results.

read the caption

Figure 6: Performativity gap and algorithmic distortion for content item c₁ under the counterfactual arrangement a1 measure across different subsets of Google search queries.

🔼 This figure illustrates the causal relationships between user requests, search queries, content arrangement, clicks, and website traffic within the context of online search engines. A user request (U) initiates the process, leading to a search query (Q) on Google Search. The search engine’s algorithm then produces a specific content arrangement (A). This arrangement influences which result the user clicks (C), ultimately impacting the traffic (T) directed to the target website.

read the caption

Figure 7: Causal graph of online search users. A web request leads to the visit of a website, partially mediated by Google search.

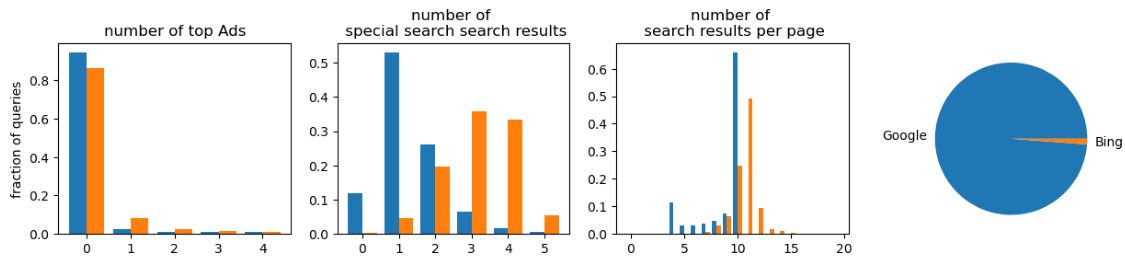

🔼 This figure presents four sub-figures showing the distributions of several features across Google and Bing search queries. The first sub-figure displays the distribution of the number of top ads. The second shows the distribution of the number of specialized search results. The third sub-figure presents the distribution of the total number of search results per page. The final sub-figure is a pie chart showing the proportion of Google and Bing queries in the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 8: Aggregate statistics over clicks and search result pages collected during our experiment. The blue bars show the statistics for Google and the orange bars show the statistics for Bing. Numbers are aggregated based on original search pages, before any modifications are performed.

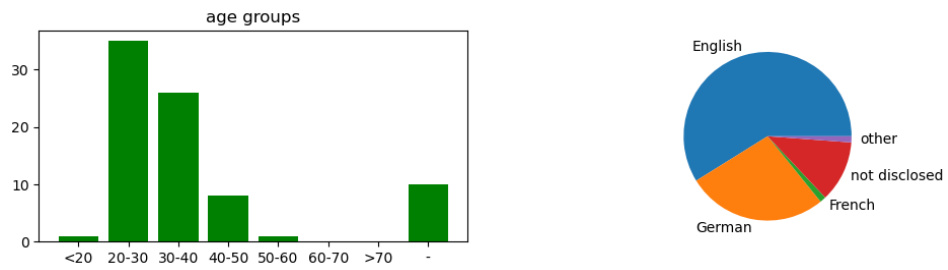

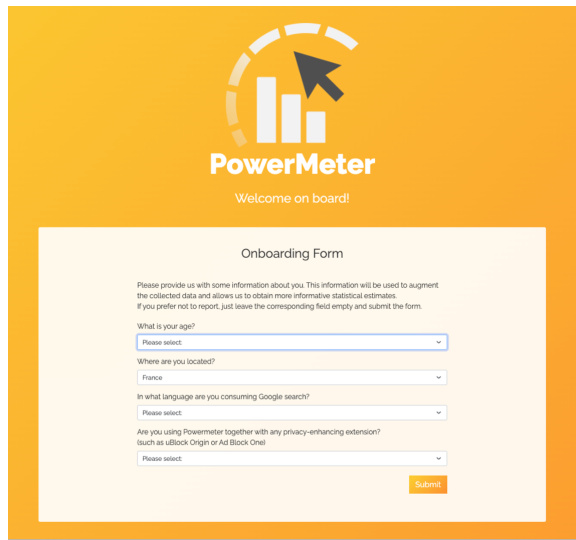

🔼 This figure shows the demographics of the 85 participants who installed the browser extension and participated in the study. The left panel displays the age distribution of the participants, indicating the number of participants in each age group. The right panel shows the language distribution, illustrating the languages used by the participants for their online searches.

read the caption

Figure 9: Aggregate user statistics collected from the 85 participants with the onboarding form. Age distribution (left) and language in which they consume online search (right). That's all the data we have about the demographics of our participants.

🔼 This figure displays the impact of altering the order of search results on click-through rates. The leftmost bar graph shows the baseline click probabilities for organic search results in positions 1-6. The middle graph illustrates the change in click probabilities when results in positions 1 and 2 are swapped, and the rightmost graph shows the same but for results in positions 1 and 3. The change in click probability demonstrates the performative power of the search engine to influence user behavior.

read the caption

Figure 1: The ability to influence web traffic through content arrangement. Blue bars show average click probability observed for generic search results in position 1 to 6 on Google search under different counterfactual arrangements; default arrangement (left), swapping results 1 and 2 (middle), swapping results 1 and 3 (right). We provide a detailed discussion in Section 5 where we also explore arrangement changes beyond reranking.

🔼 This figure displays the ability of a search engine to influence user clicks by changing the order of search results. It shows how the click-through rate (CTR) for each position changes when the order of results is altered. The blue bars represent the average click probability for each position under the default arrangement. The orange bars show the average click probability after swapping the positions of results 1 and 2 (middle) and results 1 and 3 (right). The results demonstrate a significant impact of result order on user clicks.

read the caption

Figure 1: The ability to influence web traffic through content arrangement. Blue bars show average click probability observed for generic search results in position 1 to 6 on Google search under different counterfactual arrangements; default arrangement (left), swapping results 1 and 2 (middle), swapping results 1 and 3 (right). We provide a detailed discussion in Section 5 where we also explore arrangement changes beyond reranking.

Full paper#