TL;DR#

Many real-world problems involve allocating limited resources under constraints (e.g., portfolio optimization, workload distribution). Existing methods for these “constrained allocation tasks” often struggle to satisfy constraints or converge to suboptimal solutions. The challenge stems from the complex interaction between the constraints and the allocation space, making it difficult to find effective policies.

This paper introduces PASPO (Polytope Action Space Policy Optimization), a novel approach that tackles these issues. PASPO uses an autoregressive process to sequentially sample allocations, ensuring feasibility at each step. A key innovation is a de-biasing mechanism to correct sampling bias caused by sequential sampling. Experimental results across various tasks demonstrate PASPO’s superior performance and constraint satisfaction compared to state-of-the-art methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel method for solving constrained allocation problems, a common challenge in various fields like finance and resource management. Its autoregressive approach with a de-biasing mechanism offers improved performance and guarantees constraint satisfaction, which is a significant improvement over existing techniques. This opens up avenues for developing more efficient and reliable solutions for various real-world applications.

Visual Insights#

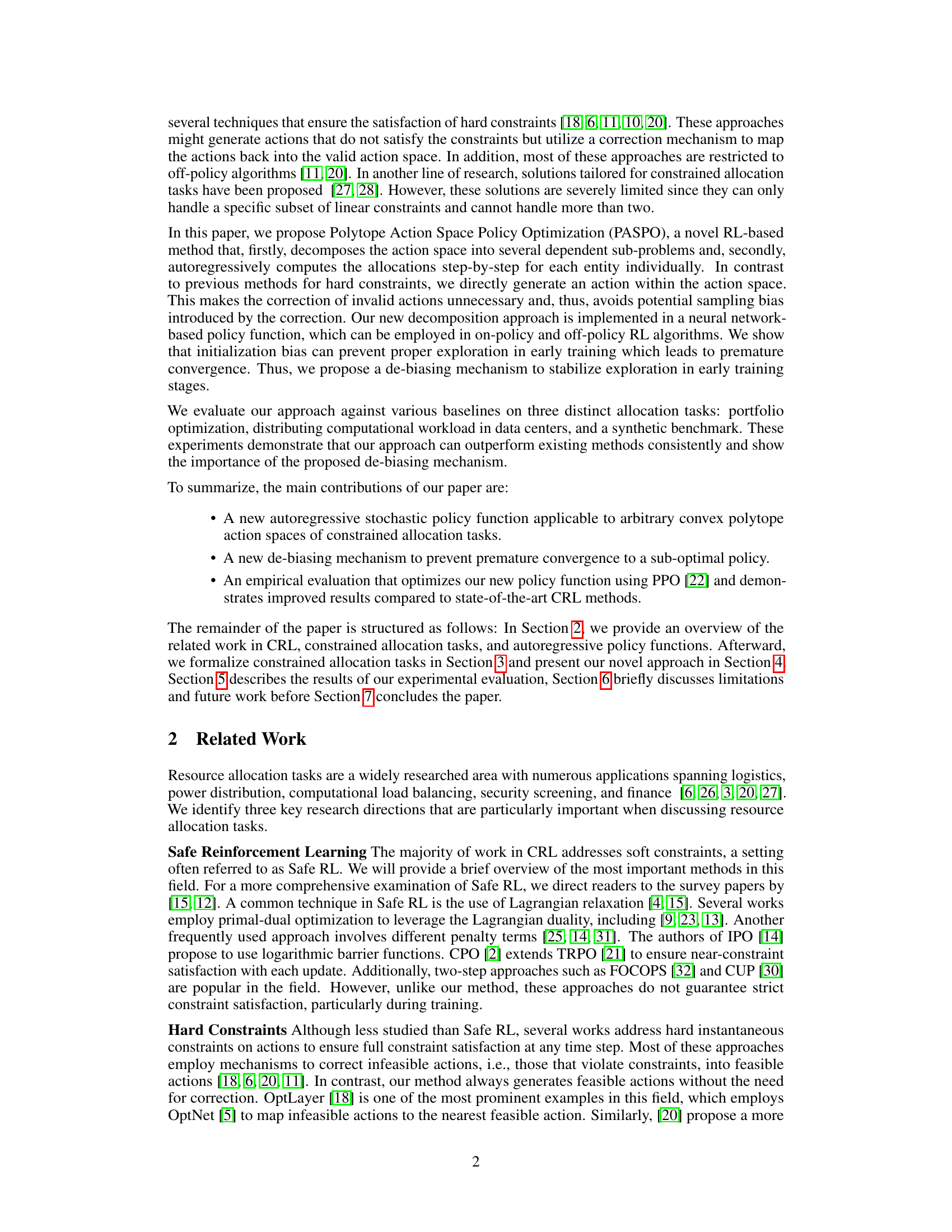

🔼 This figure shows two 3D plots visualizing allocation action spaces. The left plot (a) represents an unconstrained standard simplex, where all points within a triangular plane represent valid allocations. The right plot (b) illustrates a constrained simplex, where the valid allocations are restricted by linear inequalities, shown as a smaller, irregular polytope within the simplex. The red area highlights the valid allocation space in both cases.

read the caption

Figure 1: Examples of 3-dimensional allocation action spaces (a) unconstrained and (b) constrained (valid solutions as red area).

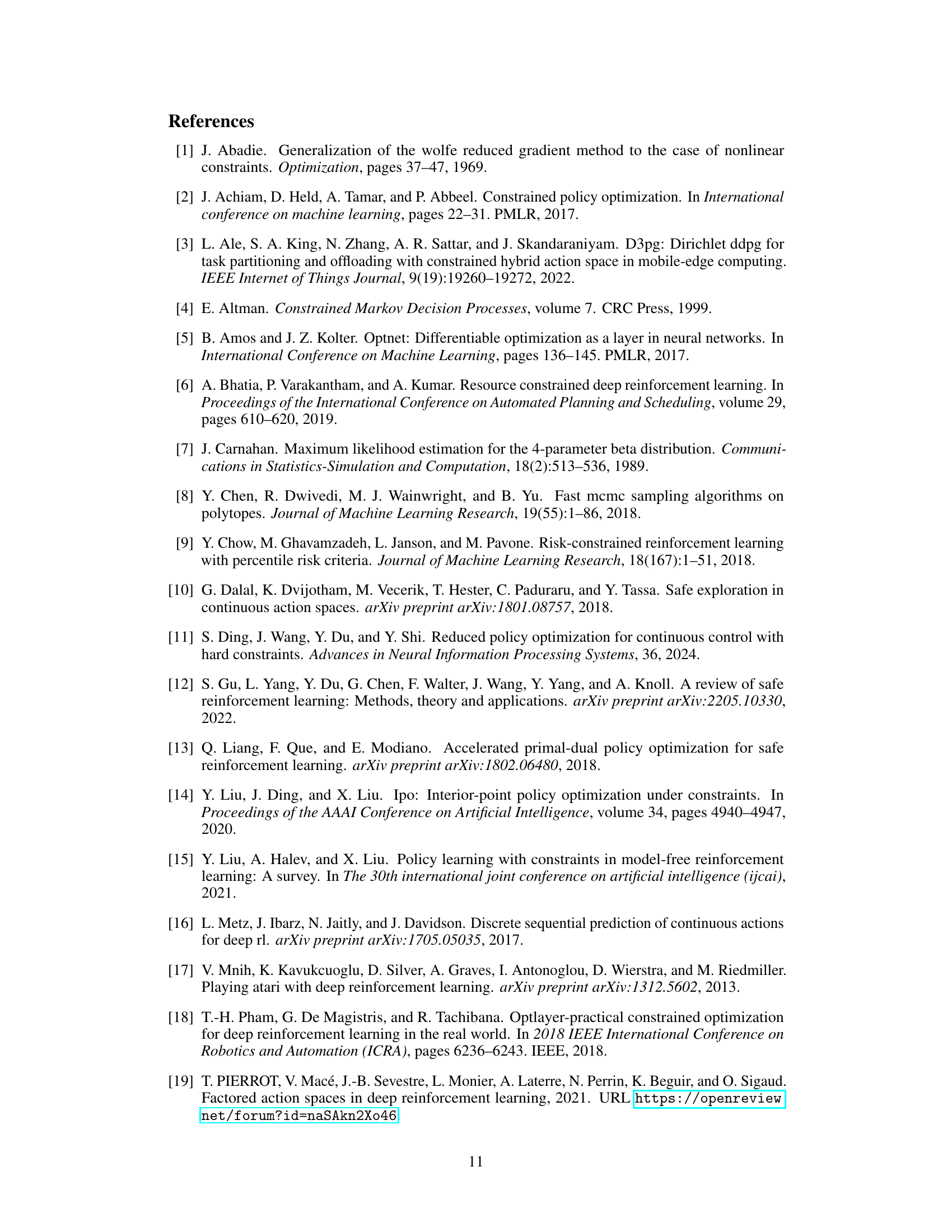

🔼 This table lists the 13 assets used in the Portfolio Optimization environment of the paper. For each asset, it provides the index number, ISIN (International Securities Identification Number), ticker symbol, and the full company name.

read the caption

Table 1: List of assets used in the environment.

In-depth insights#

Constrained Allocation#

Constrained allocation problems involve the optimal distribution of limited resources among competing entities under a set of constraints. These constraints, often linear inequalities, represent real-world limitations such as budget restrictions, capacity limits, or regulatory requirements. Finding feasible solutions that satisfy all constraints is a challenge in itself, but the real goal is to find the optimal allocation that maximizes a specific objective function (e.g., profit, efficiency, or social welfare). Reinforcement learning (RL) offers a powerful framework for solving these problems, particularly when dealing with complex or dynamic environments. However, applying standard RL approaches directly often proves difficult due to the constraints. Methods for tackling constrained allocation problems in RL often involve carefully designed policy functions that explicitly respect the constraints or penalty mechanisms that discourage constraint violations. Autoregressive approaches appear to be promising as they allow for the sequential generation of allocations, making the problem more tractable. De-biasing techniques may become necessary to prevent premature convergence to sub-optimal solutions due to the inherent biases in sequential sampling methods.

Autoregressive Policy#

An autoregressive policy, in the context of reinforcement learning for constrained allocation tasks, is a novel approach to sequentially generating allocation decisions. Instead of making all allocation decisions simultaneously, it iteratively samples allocations for each entity, conditioning each decision on the previously sampled ones. This sequential nature simplifies the problem of satisfying linear constraints inherent in many resource allocation tasks, as the feasible action space is dynamically reduced after each allocation is made. The autoregressive nature facilitates handling complex dependencies between entities, allowing for more effective policy learning compared to methods that optimize all allocations concurrently. A key advantage is that valid actions are directly generated, eliminating the need for post-hoc correction of infeasible allocations. However, this sequential approach can introduce initial biases, and the authors cleverly address this with a novel de-biasing mechanism that ensures that sufficient exploration happens during early phases of training. This de-biasing mechanism likely involves using a parameterized distribution and learning its parameters to counteract the sampling bias, ensuring that the policy can learn effectively without getting stuck in suboptimal solutions due to early training bias.

PASPO Algorithm#

The PASPO algorithm presents a novel approach to constrained resource allocation tasks by employing an autoregressive process. It decomposes the complex action space into a sequence of simpler sub-problems, allowing for efficient sampling of valid actions within the constrained polytope. A key innovation is the introduction of a de-biasing mechanism to mitigate sampling bias inherent in the sequential sampling approach, thereby promoting more thorough exploration of the action space. The algorithm’s performance is empirically validated on three distinct allocation tasks, demonstrating its superiority over existing methods in terms of both reward and constraint satisfaction. The use of a beta distribution to model allocations for each entity, while novel in this context, provides a parameterizable policy function, facilitating the use of standard reinforcement learning optimization techniques like PPO. However, the computational cost of linear programming at each step might present a challenge for high-dimensional tasks.

De-biasing Mechanism#

The core idea behind the de-biasing mechanism is to counteract the inherent bias introduced by the autoregressive sampling process. Because the allocation of resources happens sequentially, earlier allocations influence the feasible space for later ones. This creates a bias where resources might be disproportionately assigned to entities sampled earlier. To mitigate this, the authors propose estimating the parameters (α, β) of beta distributions using maximum likelihood estimation. This is done by sampling uniformly from the constrained action space and then fitting the parameters. These estimated parameters are then used to initialize the beta distributions in the policy network. The result is a more uniform allocation across all entities at the beginning of training, thus promoting better exploration and preventing premature convergence to suboptimal policies. This initialization method effectively tackles the sampling bias and is crucial to improving performance, as demonstrated in their experiments.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section would benefit from a more concrete and detailed outline. Extending PASPO to handle state-dependent constraints is a crucial area to explore, as real-world allocation tasks rarely feature static constraints. Addressing the high computational cost for many entities is also critical for scalability and practical application. This likely involves exploring more efficient optimization techniques or approximation methods for the linear programming steps. Investigating the applicability of PASPO to settings with both hard and soft constraints is important for broader applicability, potentially combining PASPO’s hard constraint handling with existing Safe RL methods for soft constraints. Finally, the authors should consider providing a more in-depth analysis of the impact of hyperparameter settings and architecture choices, possibly through extensive ablation studies, to offer more robust guidelines for future applications of their method.

More visual insights#

More on figures

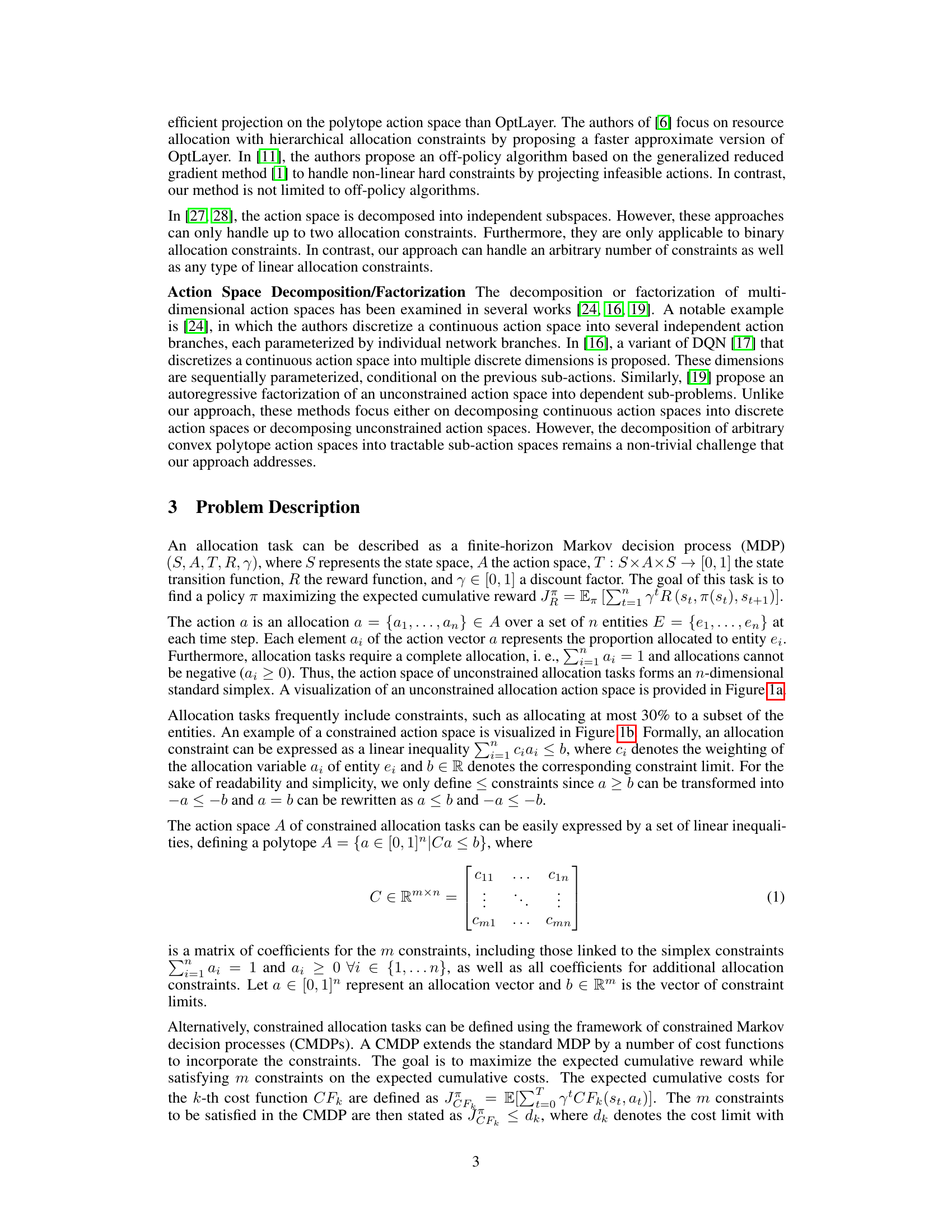

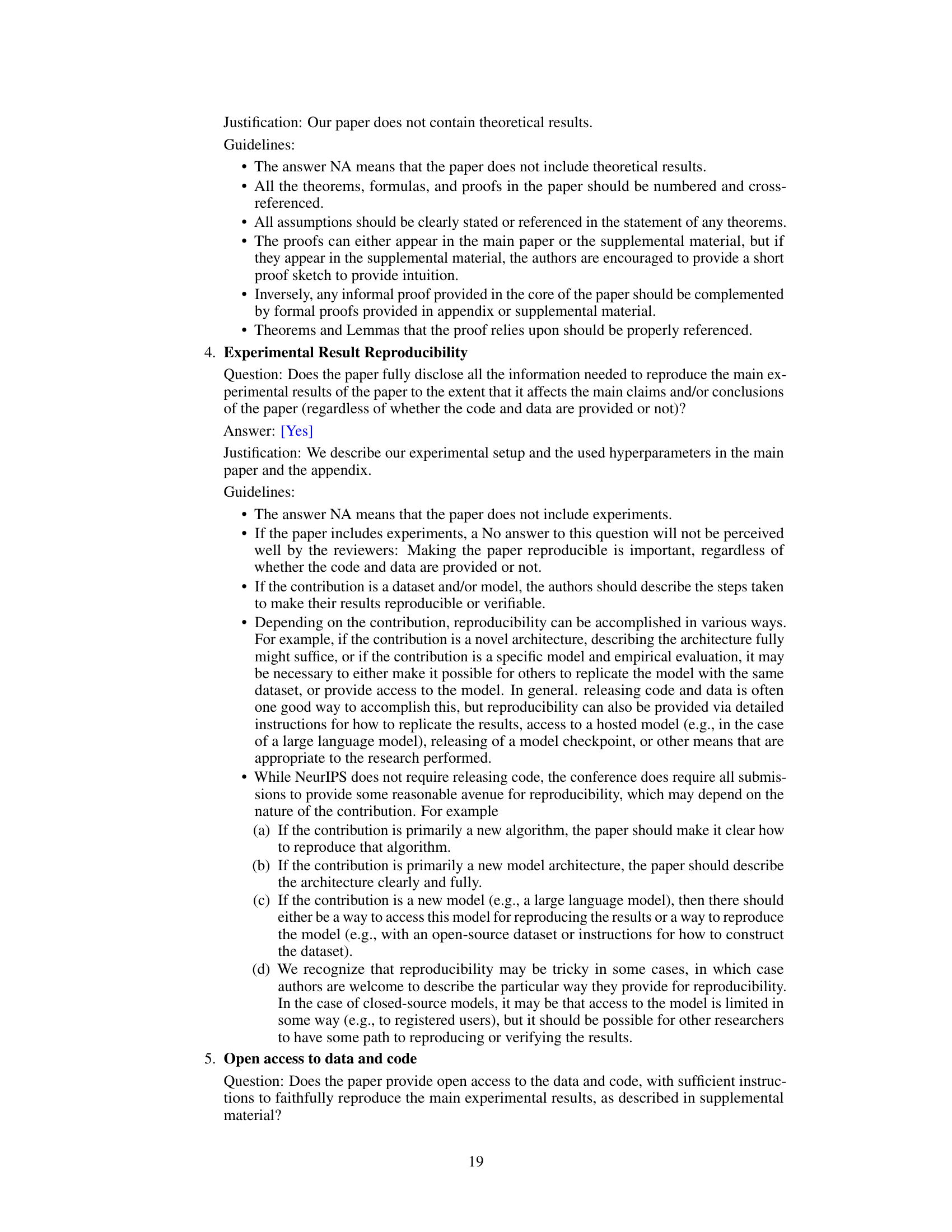

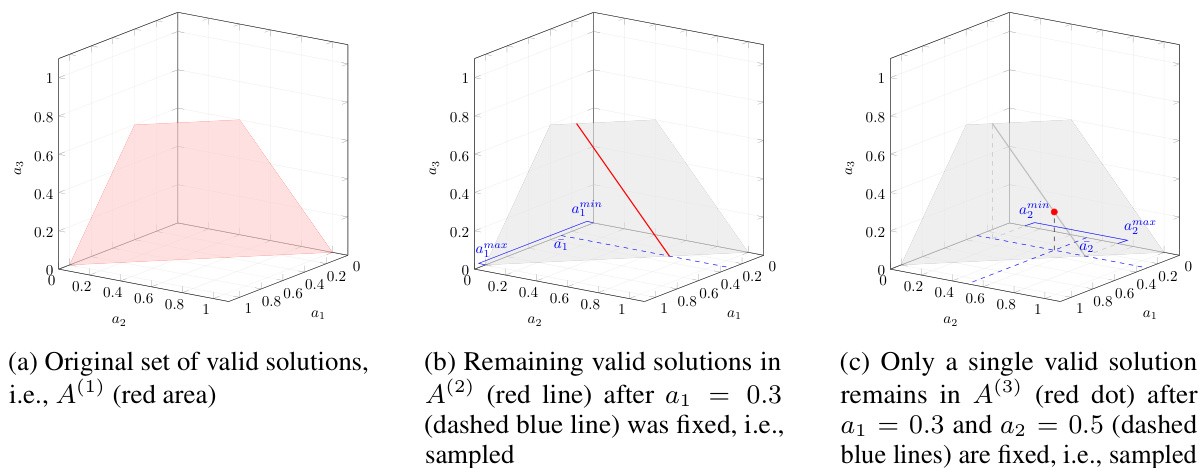

🔼 This figure illustrates the autoregressive sampling process used in the PASPO algorithm. Panel (a) shows the initial feasible region (red area) of the 3D allocation space. In panel (b), after sampling the first allocation a1 = 0.3 (dashed blue line), the feasible region shrinks to a line segment (red line). Panel (c) depicts the final step after sampling a2 = 0.5 (dashed blue lines), where the feasible region collapses to a single point (red dot), representing the final allocation.

read the caption

Figure 2: Example of sampling process of an action (a1, a2, a3) in a 3-dimensional constrained allocation task.

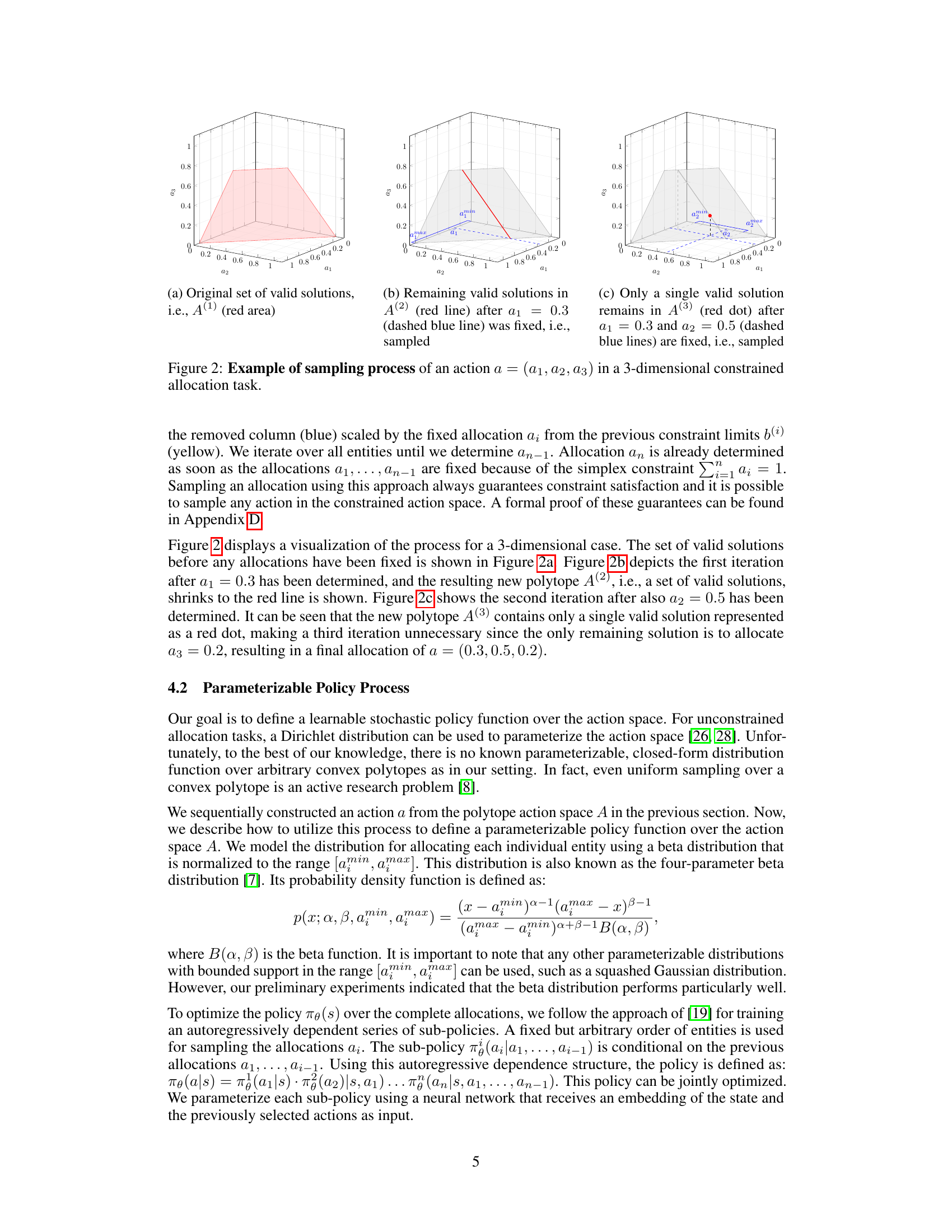

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effect of different initialization methods on the allocation process in an unconstrained simplex. Panel (a) shows the mean allocations to each of seven entities when using either a uniform distribution or the authors’ proposed initialization method. The authors’ method results in more balanced allocations. Panels (b) and (c) visualize the distribution of 2500 allocations in a three-entity setting using uniform sampling and the proposed initialization, respectively, highlighting the impact of initialization on the resulting allocation distribution.

read the caption

Figure 3: The impact of initialization in an unconstrained simplex. (a) Mean allocations ai to each entity in a seven entity setup when sampling each individual allocation using the uniform distribution (red) vs. our initialization (blue). (b,c) Distribution of 2500 allocations in a three entity setup when sampling each individual allocation uniformly (b) or using beta distributions with parameters set according to our initialization (c).

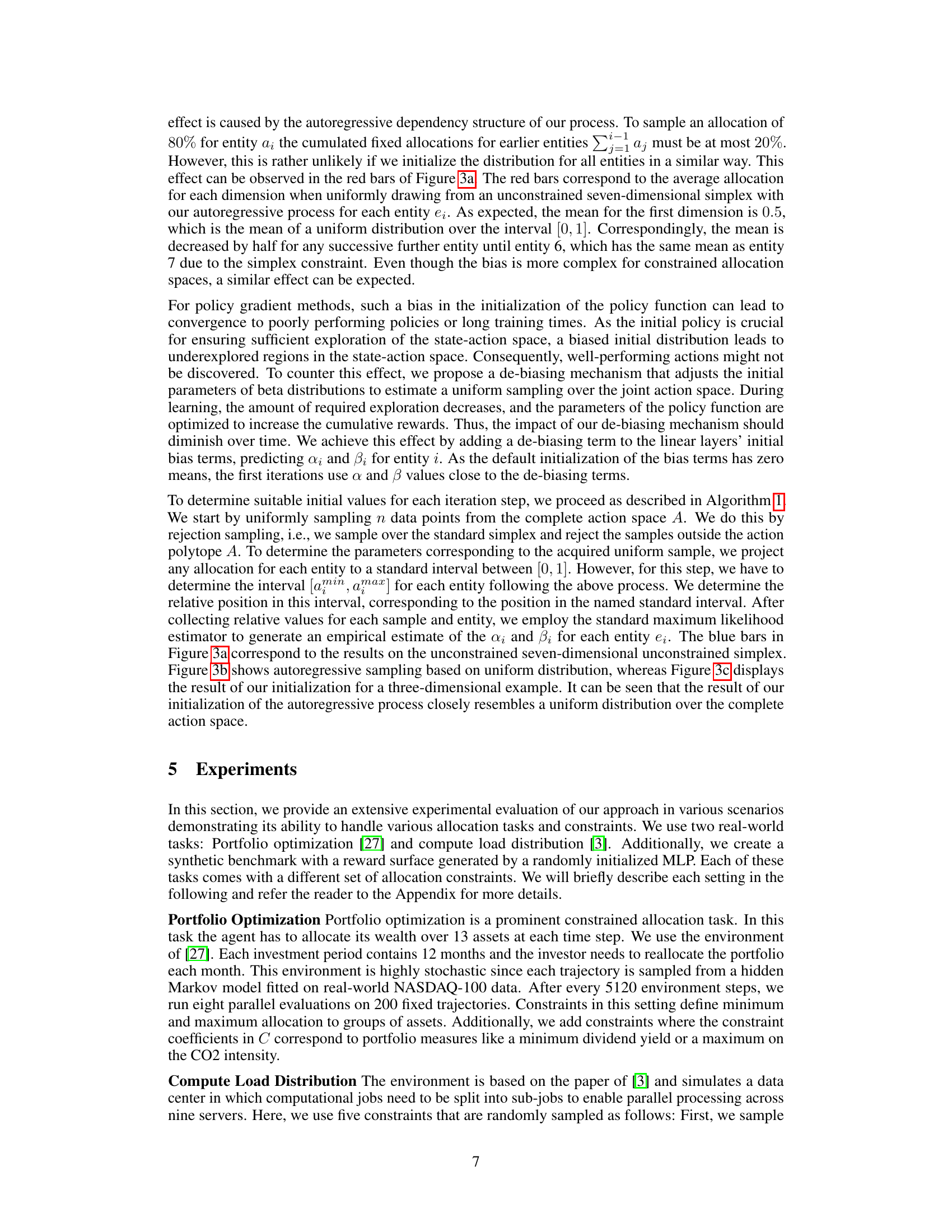

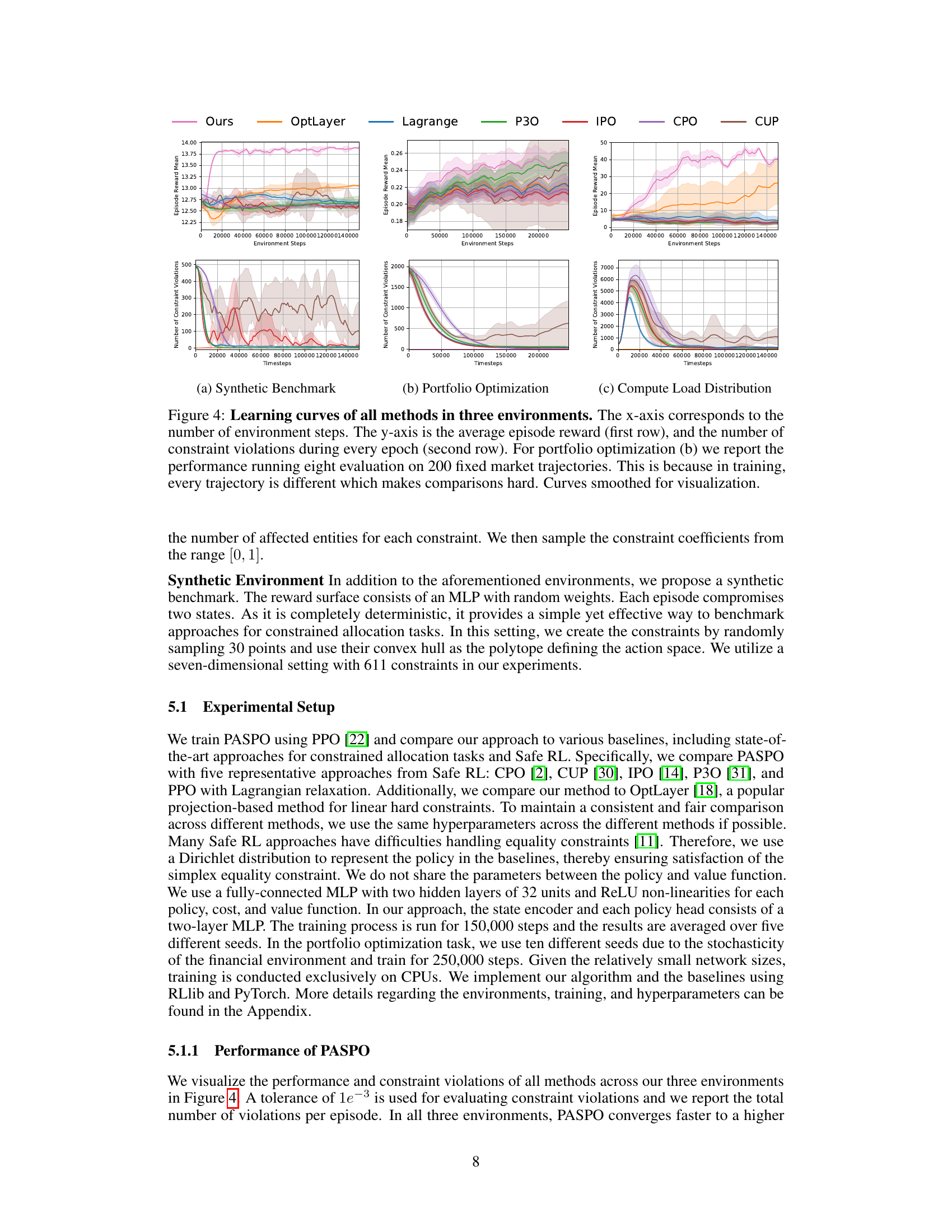

🔼 This figure shows the performance of different reinforcement learning algorithms on three constrained allocation tasks. The top row displays the average episode reward over time for each algorithm, while the bottom row shows the number of constraint violations. The results demonstrate the superior performance of PASPO (the authors’ algorithm) across all three tasks, highlighting its ability to maintain high reward while strictly adhering to constraints, unlike the other algorithms that demonstrate various levels of constraint violation.

read the caption

Figure 4: Learning curves of all methods in three environments. The x-axis corresponds to the number of environment steps. The y-axis is the average episode reward (first row), and the number of constraint violations during every epoch (second row). For portfolio optimization (b) we report the performance running eight evaluation on 200 fixed market trajectories. This is because in training, every trajectory is different which makes comparisons hard. Curves smoothed for visualization.

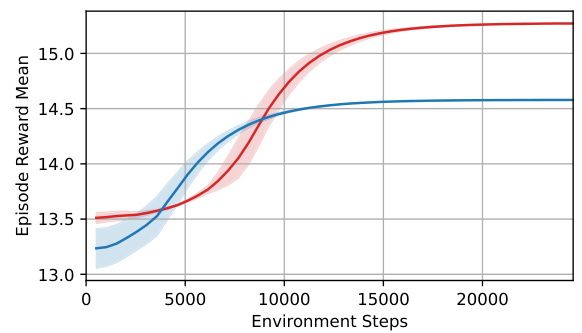

🔼 This figure presents ablation studies to show the effect of the de-biased initialization and the allocation order. The left subplot (a) compares the performance with and without de-biased initialization. The right subplot (b) compares the performance with standard and reversed allocation order. It shows that de-biased initialization is important for faster learning and better performance, while the allocation order has little effect.

read the caption

Figure 5: Ablations in (a) show the performance of our approach with (blue) and without (orange) the de-biased initialization. In (b) depicts the impact of the allocation order. We reverse the allocation order (red).

🔼 This figure visualizes two 3-dimensional allocation action spaces. (a) shows an unconstrained standard simplex, where all points within the simplex represent valid allocations. (b) illustrates a constrained simplex with two linear constraints (a3 ≤ 0.6 and a2 ≤ 0.7), which restricts the valid allocation space to a smaller subset represented by the red area.

read the caption

Figure 1: Examples of 3-dimensional allocation action spaces (a) unconstrained and (b) constrained (valid solutions as red area).

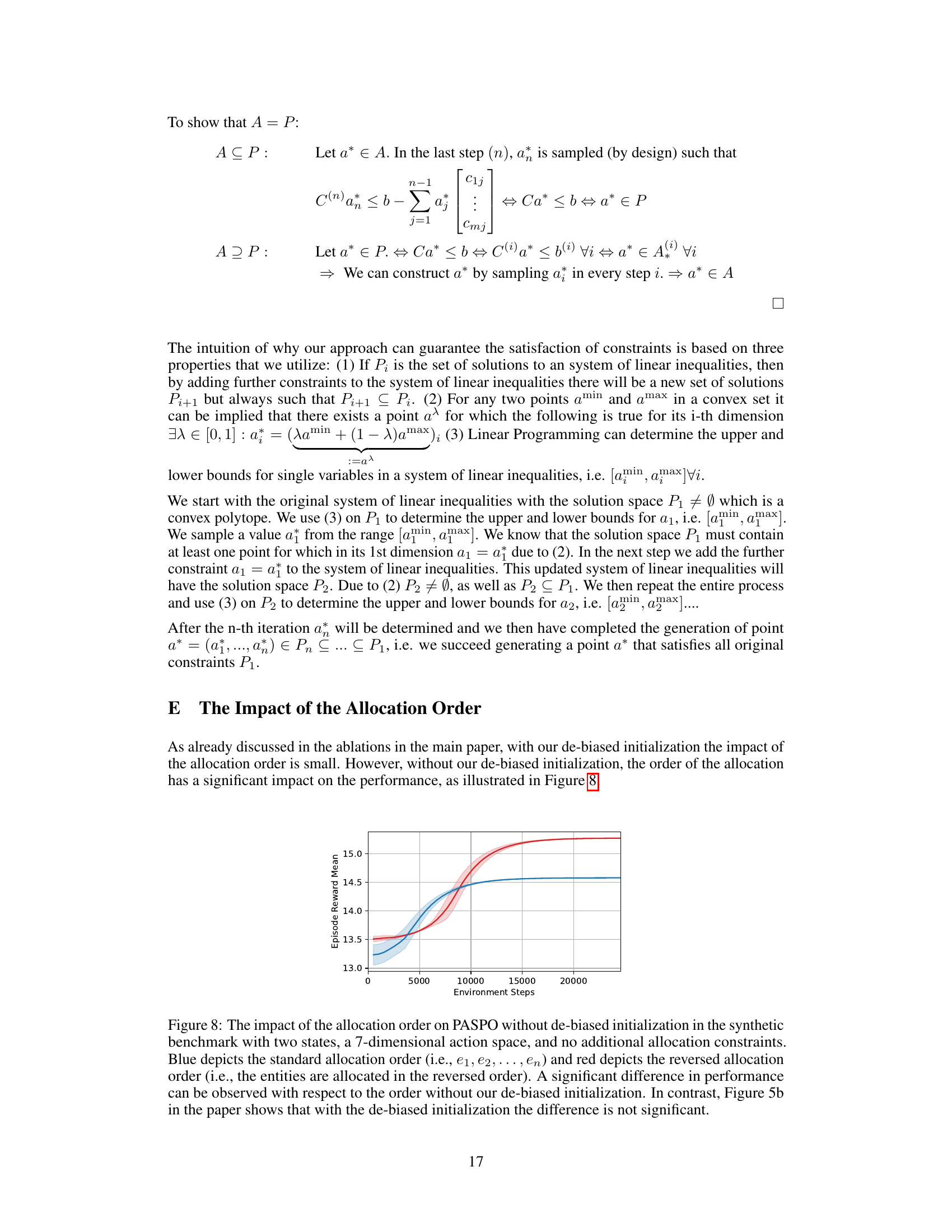

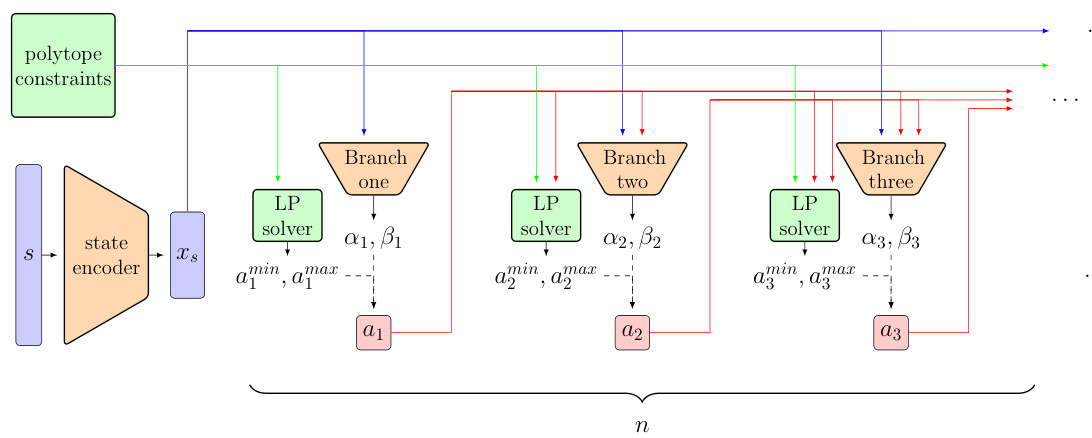

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Polytope Action Space Policy Optimization (PASPO) method. It shows how the state, represented by s, is first encoded by a state encoder to produce a latent representation xs. This representation, along with the previously sampled allocations (a1, a2,…, ai-1), is then fed into a series of neural networks, one for each entity. Each network outputs parameters αi and βi for a beta distribution used to sample the allocation ai for entity i. The beta distribution’s support is determined by solving a linear program (LP) to find the minimum and maximum feasible values for ai given the previously allocated resources and constraints. This process is repeated sequentially for each entity until a full allocation is generated. The figure highlights the iterative nature of the process, showing how each entity’s allocation depends on the previous allocations and the overall polytope constraints.

read the caption

Figure 7: Architecture of PASPO

🔼 This figure shows two ablation studies conducted by the authors to evaluate their proposed method, PASPO. The left subplot (a) compares the performance of PASPO with and without the debiasing mechanism, demonstrating the positive impact of debiasing on the model’s performance. The right subplot (b) demonstrates the effect of changing the order of entities allocation on the model’s performance, showing that changing the allocation order has little effect on the results.

read the caption

Figure 5: Ablations in (a) show the performance of our approach with (blue) and without (orange) the de-biased initialization. In (b) depicts the impact of the allocation order. We reverse the allocation order (red).

More on tables

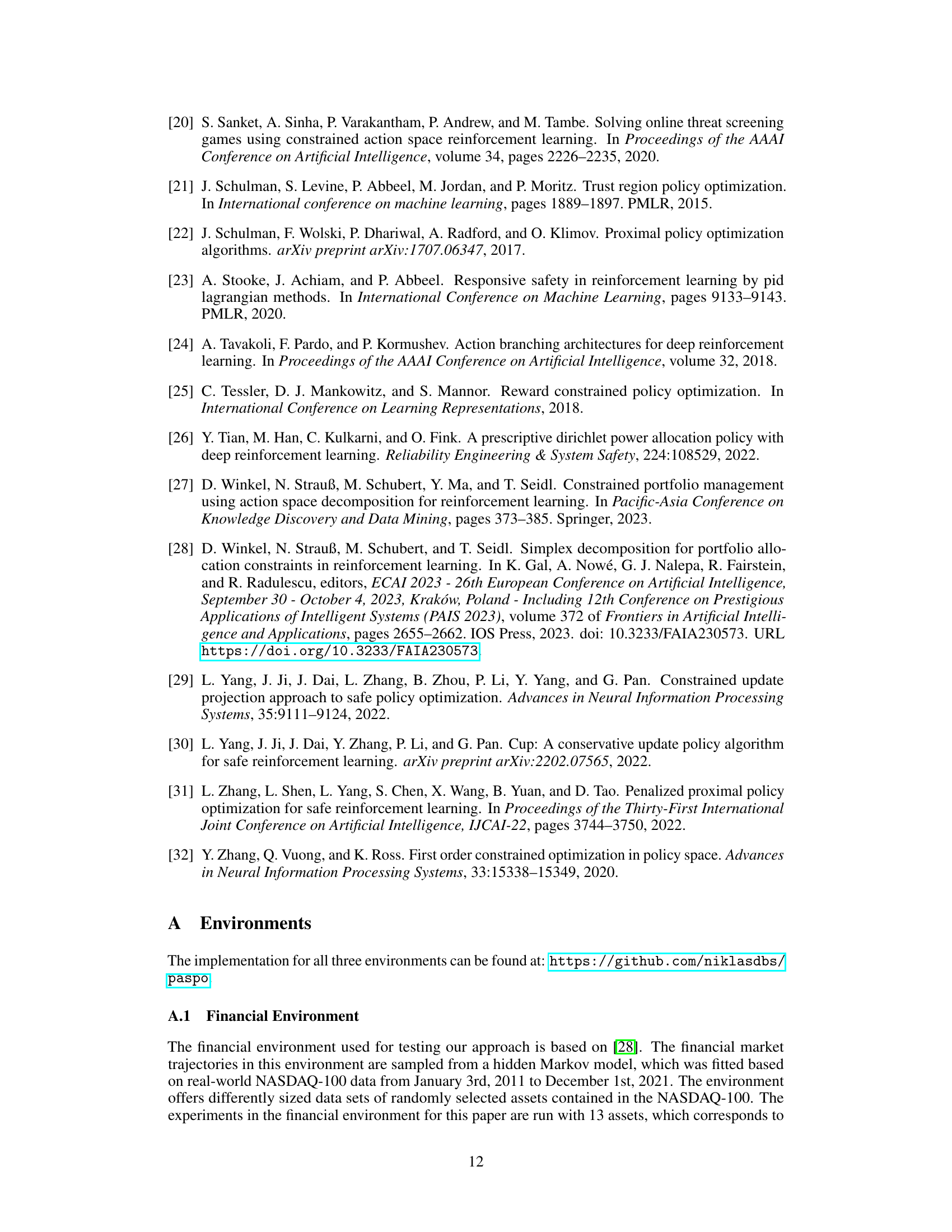

🔼 This table presents Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for 13 assets used in the Portfolio Optimization environment of the paper. The KPIs include estimated total energy use and CO2 emissions to Enterprise Value Including Cash (EVIC), estimated weighted average cost of capital, estimated dividend yield, and estimated return on equity. These metrics are calculated based on 2021 data from Refinitiv and are used to define constraints in the portfolio optimization task.

read the caption

Table 2: KPI estimates for assets based on 2021 (final year of the used data set, source: Refinitiv); EVIC - Enterprise value including Cash

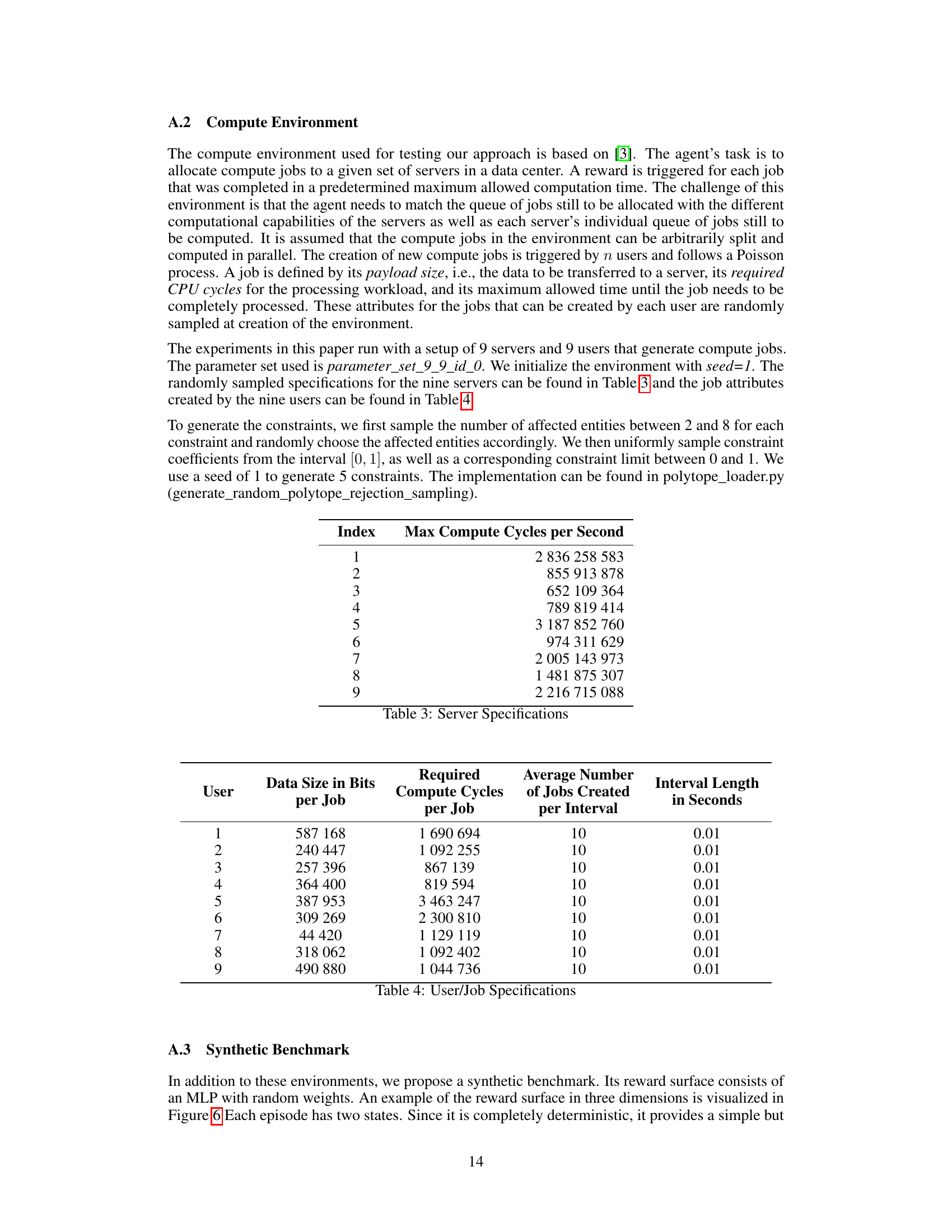

🔼 This table presents the specifications of the nine servers used in the compute load distribution environment. For each server, it lists the maximum compute cycles per second that can be performed. This data is used to simulate the varying computational capabilities of servers in a data center.

read the caption

Table 3: Server Specifications

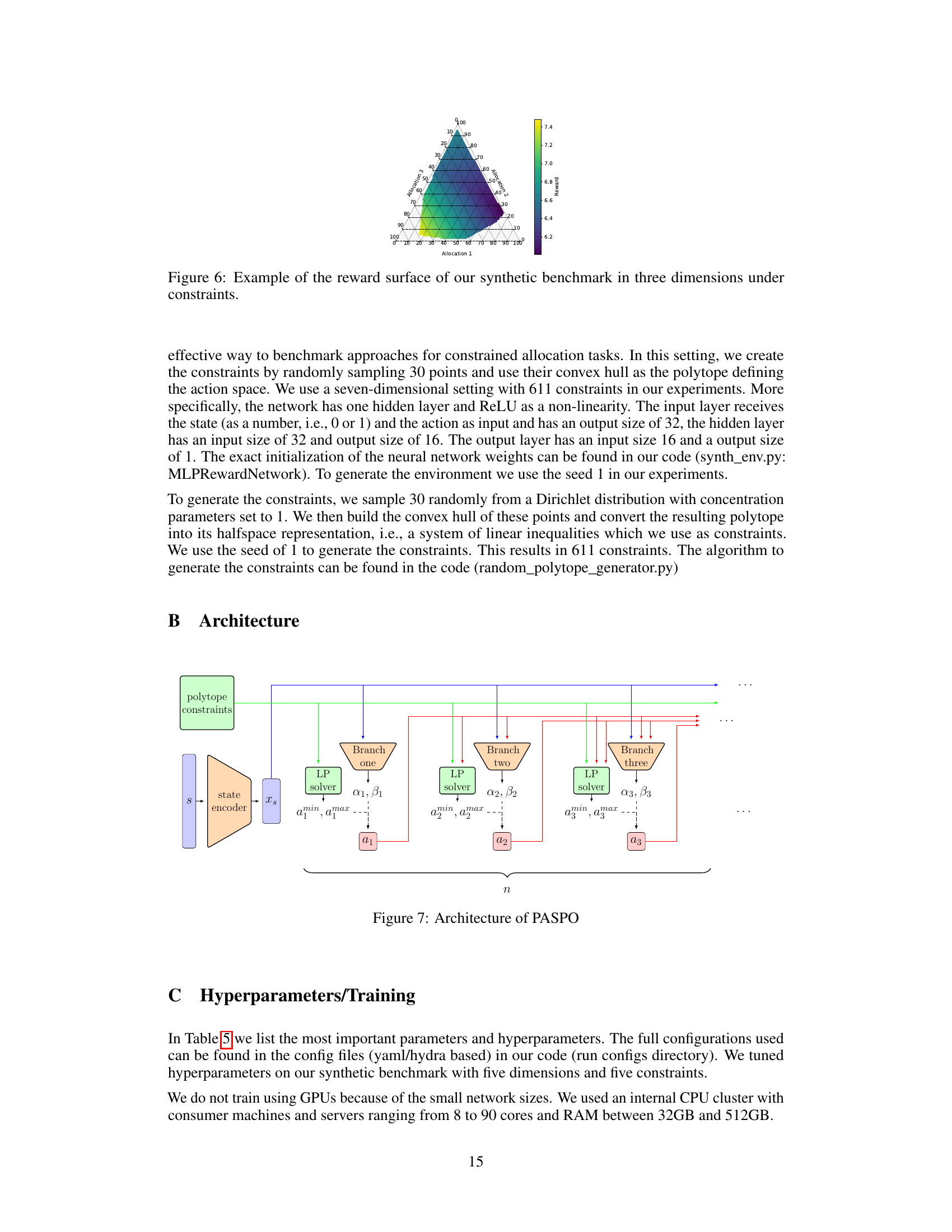

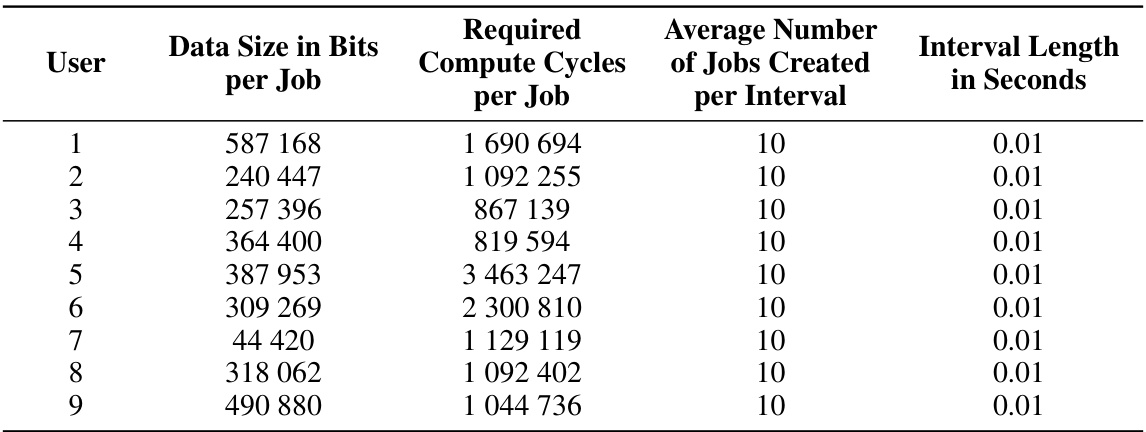

🔼 This table lists the specifications for each of the nine users that generate compute jobs in the compute load distribution environment. For each user, it shows the data size in bits per job, the required compute cycles per job, the average number of jobs created per interval, and the length of each interval in seconds. These specifications are randomly sampled at the creation of the environment.

read the caption

Table 4: User/Job Specifications

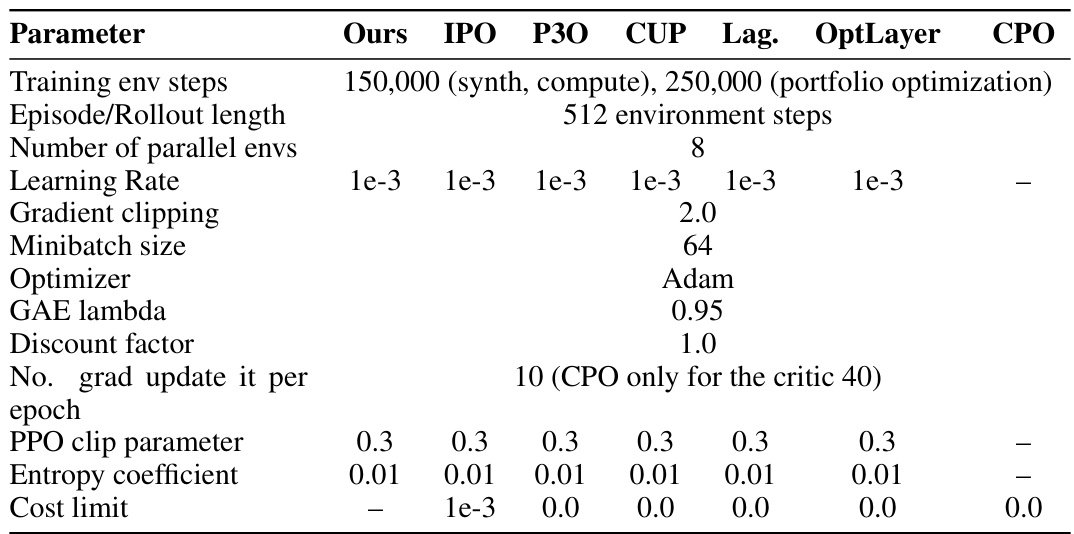

🔼 This table compares the hyperparameters used for training the proposed PASPO method against several baseline methods for constrained reinforcement learning. The hyperparameters include training steps, rollout length, learning rate, gradient clipping, minibatch size, optimizer, GAE lambda, discount factor, number of gradient updates per epoch, PPO clip parameter, entropy coefficient, and cost limit. The table highlights the differences in hyperparameter settings between the PASPO method and various baselines (IPO, P3O, CUP, Lag, OptLayer, and CPO) to aid in understanding the experimental setup and potential reasons for performance differences.

read the caption

Table 5: The most important Parameters and Hyperparameters for Various Methods

Full paper#