↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Quanta image sensors (QIS) offer unique advantages for capturing fast temporal dynamics in low-light settings by detecting individual photons. However, raw QIS data is often too sparse to be directly usable for analysis and requires binning. This binning comes at the cost of temporal resolution degradation.

This paper introduces bit2bit, a novel method to address this issue. It reconstructs high-quality image stacks at the original spatiotemporal resolution by predicting photon location probability distribution using a self-supervised approach and a novel masking loss function to compensate for the inadequacy of Poisson distribution assumption for binary data. The method is evaluated on both simulated and real SPAD data, achieving significantly higher reconstruction quality and throughput compared to existing state-of-the-art methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant as it presents bit2bit, a novel self-supervised method for reconstructing high-quality video from sparse binary quanta image data. This addresses a critical challenge in quanta image processing, enabling the use of existing analysis techniques on this type of data and surpassing the state-of-the-art. The introduction of a new dataset for real SPAD data further enhances the value of this work for the community. The method also has potential applications beyond quanta image processing, applicable to any binary, higher-dimensional spatial data from Poisson point processes.

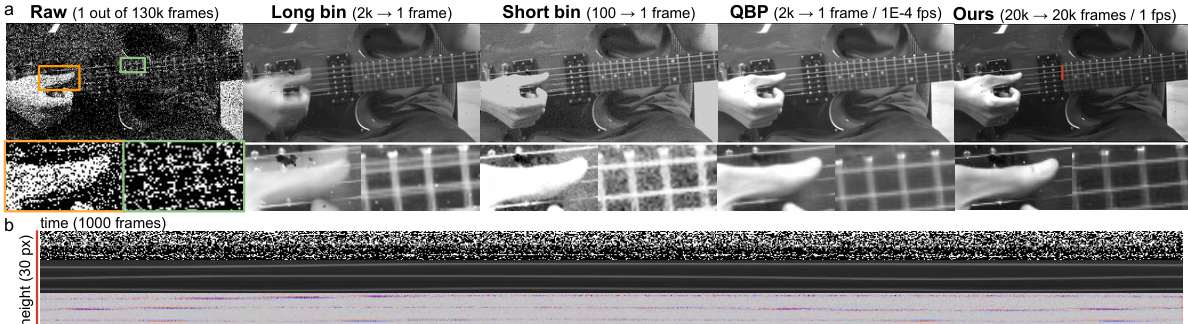

Visual Insights#

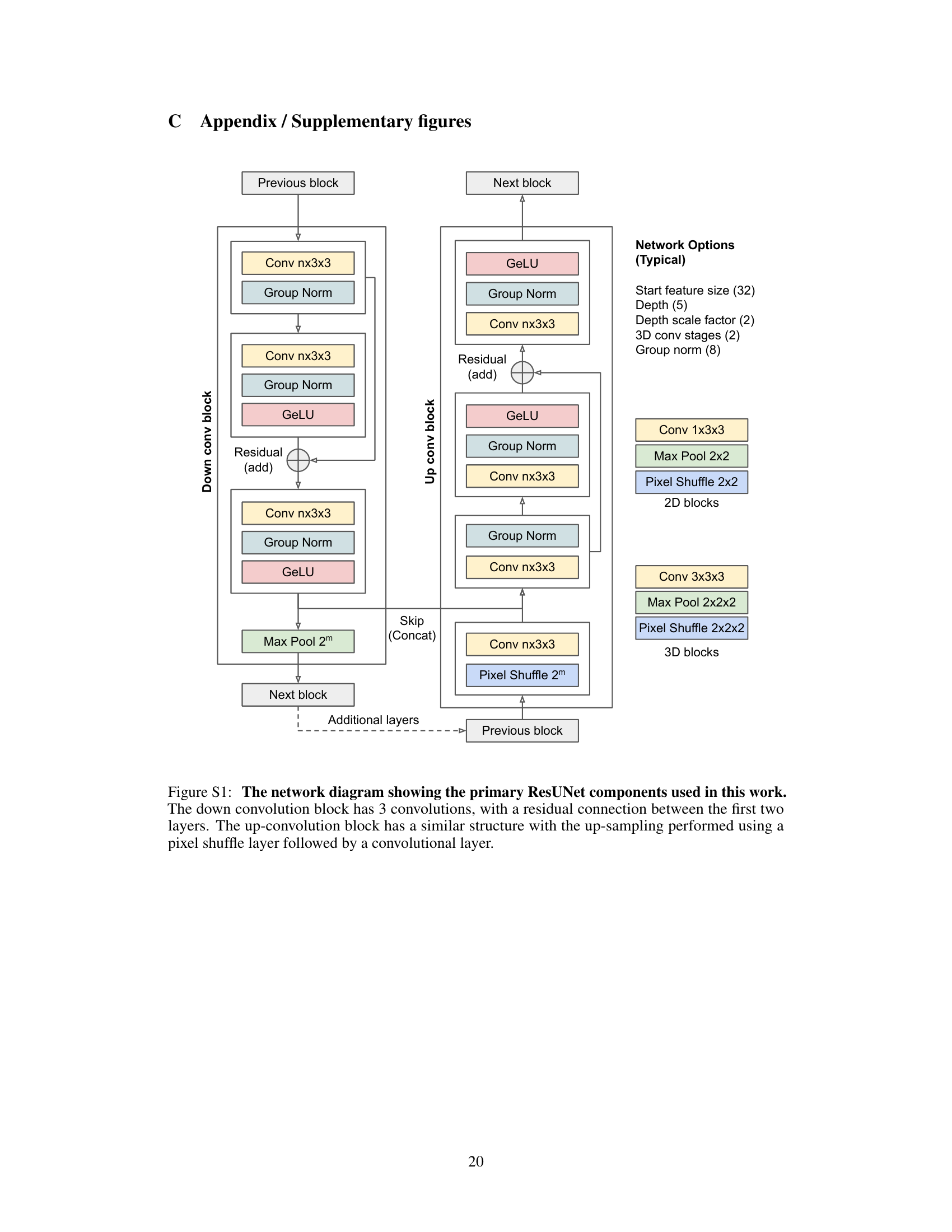

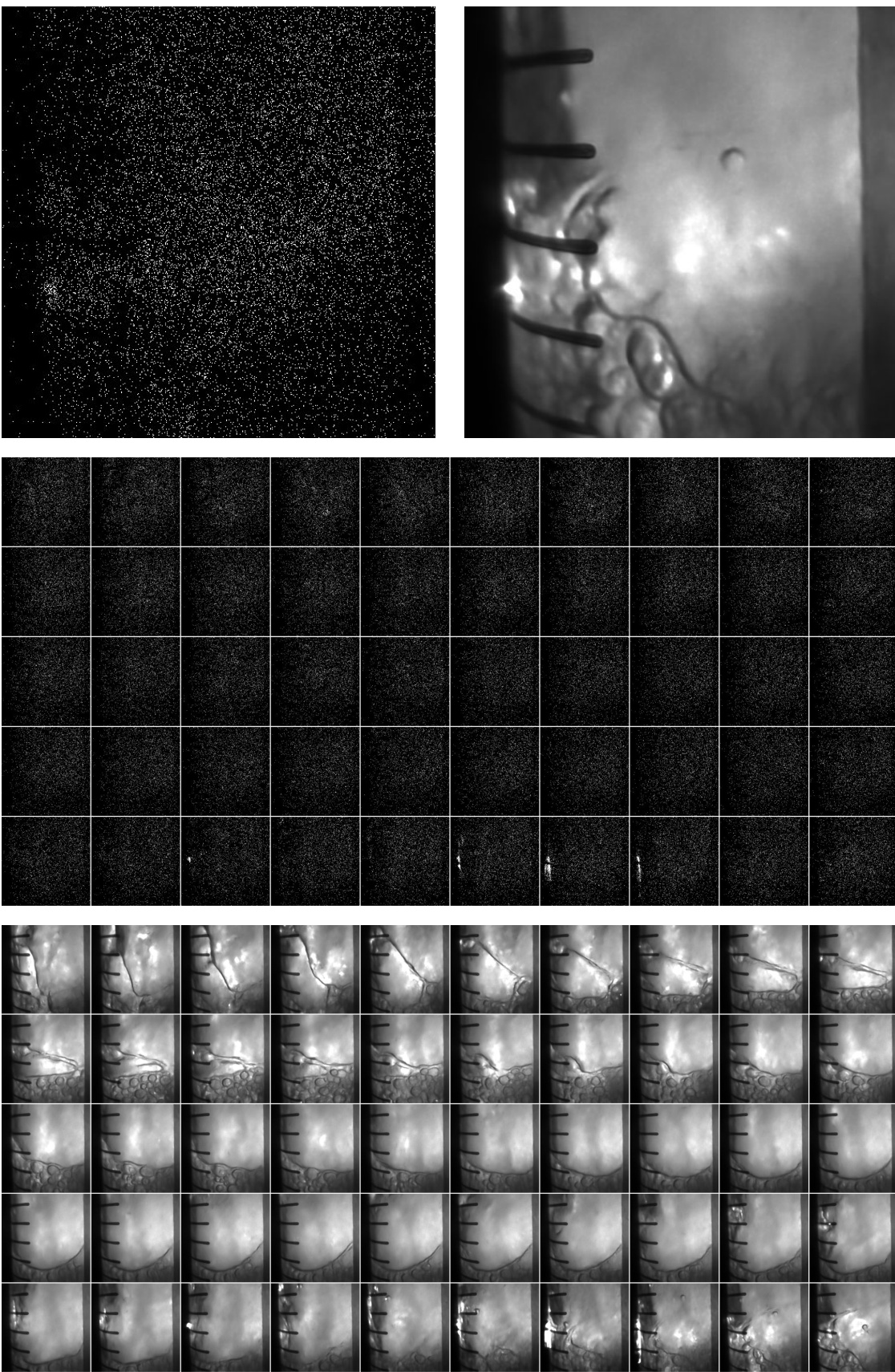

This figure visualizes the reconstruction task of the bit2bit method. It demonstrates how a signal in spacetime generates discrete photons, which are then detected by sensors as a sparse binary map due to shot noise. The figure displays real SPAD raw data, showing the sparse photon detection events, and compares the result of the proposed method with a simple binning approach.

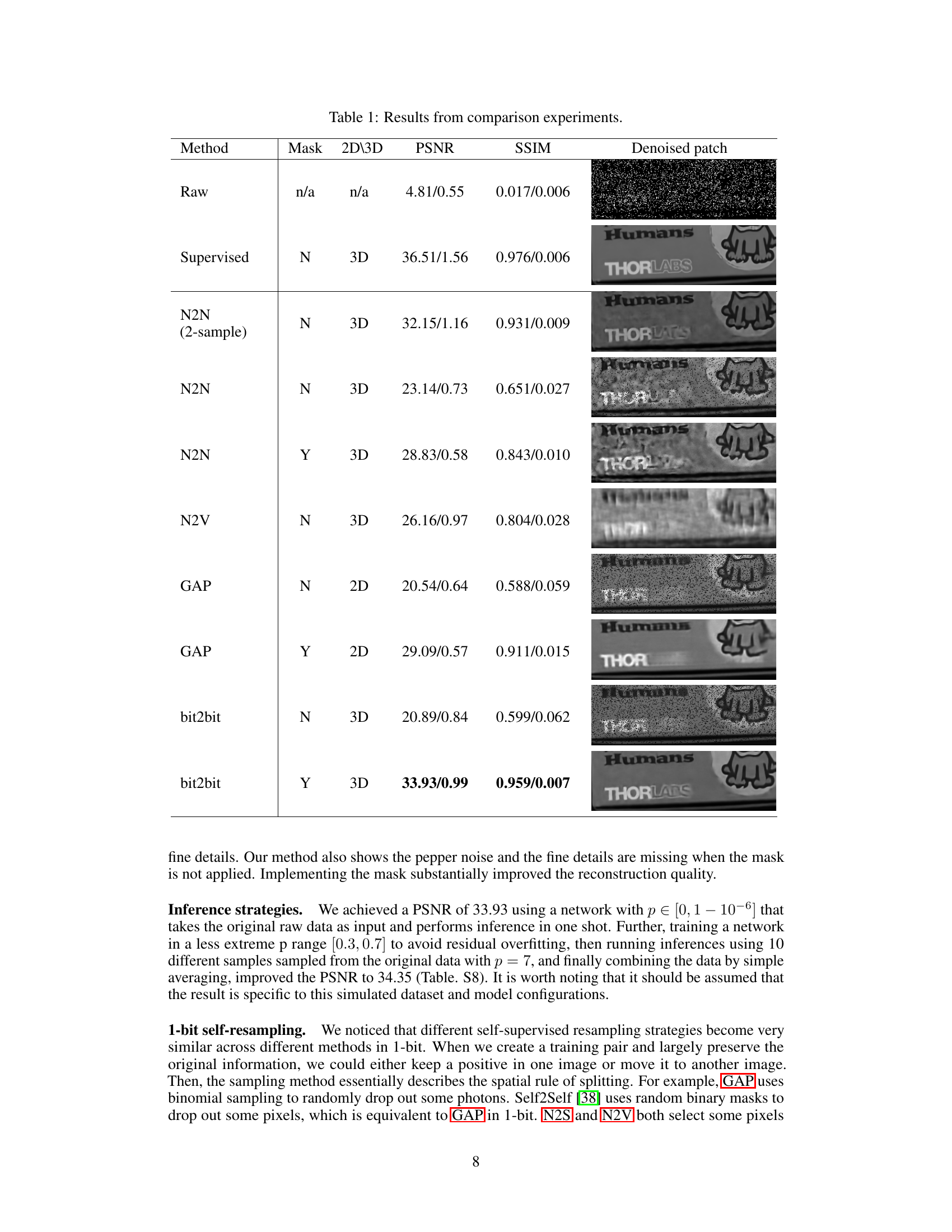

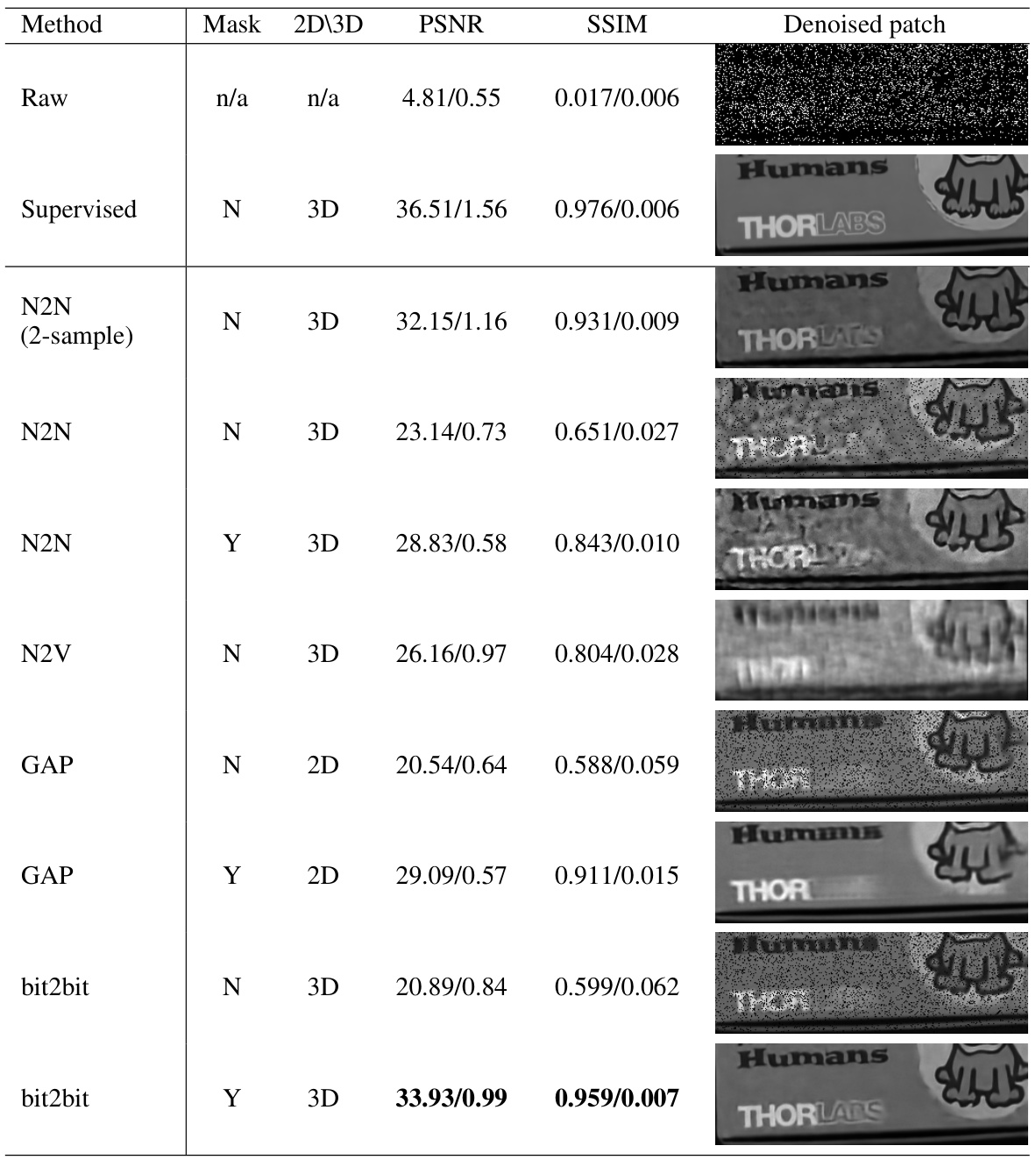

This table compares the performance of different image reconstruction methods on both simulated and real SPAD data. The methods compared include supervised learning, Noise2Noise (N2N), Noise2Void (N2V), Generative Accumulation of Photons (GAP), and the proposed bit2bit method. The table shows the PSNR and SSIM values for each method, with and without masking, along with visual examples of the denoised images. The results demonstrate that the proposed bit2bit method with masking significantly outperforms other methods, especially in terms of PSNR.

In-depth insights#

1-bit quanta video#

The concept of “1-bit quanta video” presents a significant challenge and opportunity in the field of image processing. It highlights the limitations of traditional image sensors in low-light conditions and introduces the potential of single-photon avalanche diode (SPAD) arrays. The core issue lies in the sparse and noisy nature of the data; each pixel represents only the presence or absence of a single photon, leading to information loss and reconstruction difficulties. Self-supervised learning methods, such as those based on masked loss functions, become crucial for denoising and reconstructing high-quality video without ground truth data. The challenges involve handling the non-Poissonian nature of photon arrivals and effectively utilizing spatiotemporal information. Novel datasets with a wide variety of real-world SPAD recordings are essential for developing and evaluating reconstruction techniques. This area of research demonstrates the potential for groundbreaking advancements in high-speed, low-light imaging, enabling applications where traditional methods fall short. Addressing the issues of overfitting and efficient processing are also key considerations. Ultimately, successful reconstruction of high-fidelity video from 1-bit quanta data holds significant promise for various scientific and technological applications.

Self-supervised learning#

Self-supervised learning is a powerful technique for training machine learning models, especially in scenarios where labeled data is scarce or expensive. It leverages inherent structures and redundancies within the unlabeled data itself to generate pseudo-labels or supervisory signals. This contrasts with supervised learning, which requires manually labeled datasets. The core idea is to create a pretext task, a self-defined problem, whose solution indirectly benefits the actual task. Successful self-supervised methods often focus on data augmentation, contrastive learning, or predictive modeling. The choice of pretext task significantly impacts performance, requiring careful consideration of data characteristics. Despite challenges in design and evaluation, self-supervised learning has shown promise in various applications, particularly in image processing and natural language processing, potentially bridging the gap towards more general-purpose, data-efficient AI. Further research into more robust pretext tasks and effective evaluation metrics is needed to unlock the full potential of this method.

Masked loss function#

The core idea behind the “Masked loss function” is to cleverly address the inherent dependency between input and target images generated from binary quanta data. In this approach, during training, the loss function is masked to ignore pixels where the input contains a photon detection event. This masking strategy is crucial because a photon’s presence in the input implies its necessary absence in the target, creating a deterministic relationship that would otherwise hinder effective learning. By masking the loss, the network is forced to learn from areas of uncertainty, where photon presence/absence is not predetermined, leading to a more accurate reconstruction of the underlying signal. This masking technique significantly enhances the model’s ability to handle the sparse and binary nature of quanta image data, preventing the generation of artifacts while leveraging the self-supervised learning framework. The effectiveness of this method is highlighted through comparative analyses, demonstrating substantial improvements in reconstruction quality compared to unmasked approaches and other state-of-the-art techniques.

Real SPAD datasets#

The availability of real SPAD datasets is crucial for evaluating and benchmarking the performance of novel quanta image reconstruction techniques. A major contribution of this research is the introduction of a new dataset containing a wide variety of real SPAD videos. This dataset captures scenes under diverse and challenging imaging conditions, such as varying ambient light levels, strong motion, and ultra-fast events. The comprehensive nature of this dataset will enable more robust and meaningful comparisons between different methods. The diversity of scenarios presented in the dataset is important to ensure that algorithms generalize well to real-world applications. Further, making the dataset publicly available allows researchers to use the same benchmarks, promoting fair comparisons and advancing the field. The creation of a standardized dataset fosters collaboration and accelerates development in quanta image sensing.

Future of QIS#

The future of Quanta Image Sensors (QIS) is bright, driven by ongoing advancements in SPAD technology. Higher resolution, improved sensitivity, and reduced cost are key development areas. Applications beyond traditional imaging will likely emerge, leveraging QIS’s unique time-resolved capabilities for advanced scientific instruments, high-speed 3D imaging, and even LiDAR. Algorithm development is crucial; sophisticated computational techniques are needed to effectively process the sparse, noisy data generated by QIS, and self-supervised machine learning methods may play an important role. Overcoming challenges such as the binary nature of the data, high computational demands, and the need for specialized hardware will be crucial. Despite these hurdles, the potential of QIS for groundbreaking applications across various fields, particularly where speed and low light are critical, promises a transformative impact on multiple domains. Collaboration across disciplines will be essential to fully unlock QIS’s potential.

More visual insights#

More on figures

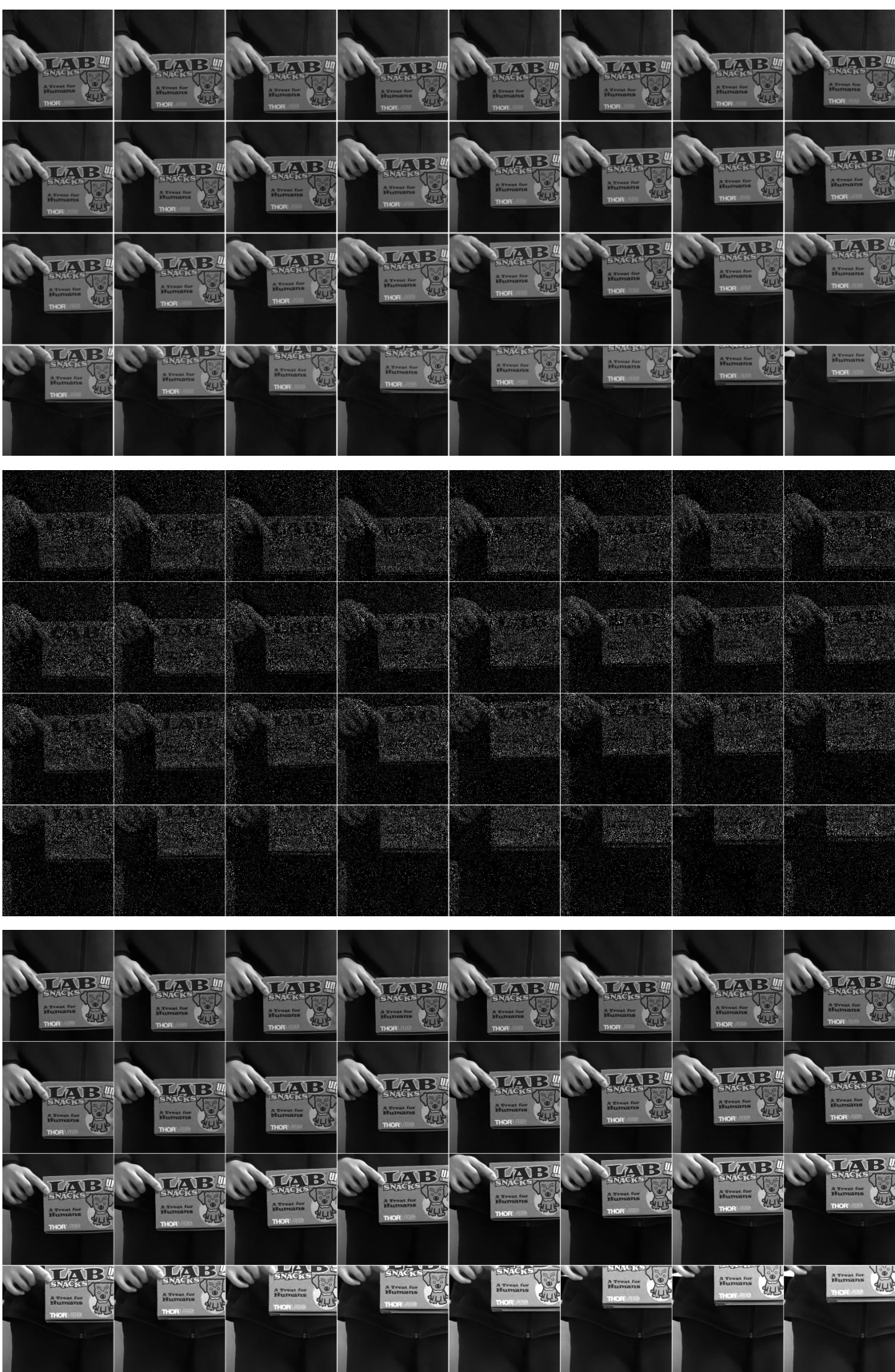

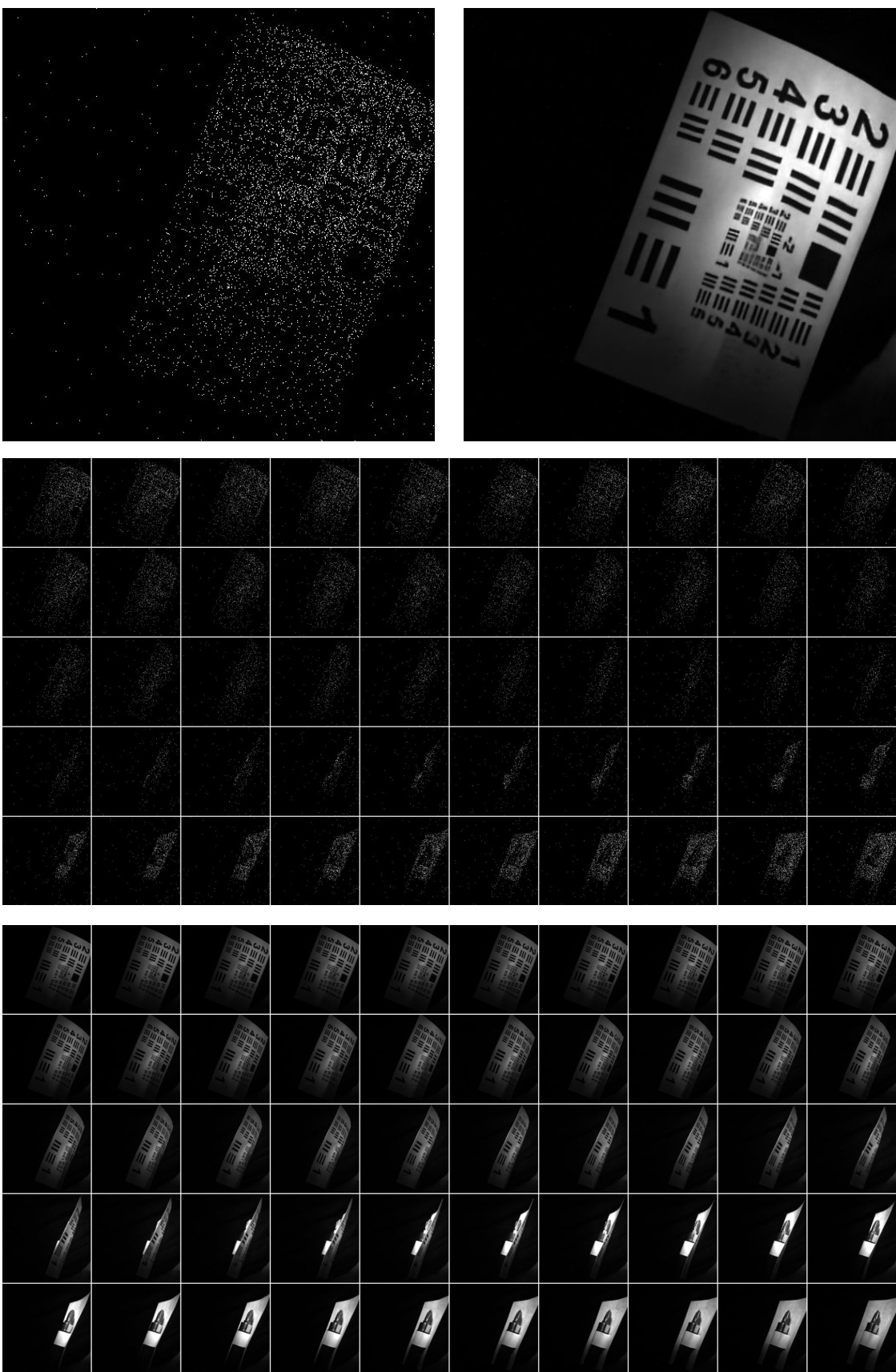

This figure showcases the results of the bit2bit method applied to various real-world SPAD datasets. The top row shows the raw, sparse binary SPAD data for each scene. The middle row displays the corresponding reconstructions generated by the bit2bit method, highlighting its ability to reconstruct high-quality images from noisy, sparse input. Each column represents a different scene: a CPU fan in motion, a histology slide viewed under a microscope, sonicating bubbles, a USAF 1951 resolution target spinning on a drill, a plasma ball, and a color-temporal coded sequence. The bottom section includes additional examples of raw data and reconstructed keyframes for the CPU fan and H&E slide scenarios, further demonstrating the efficacy of bit2bit.

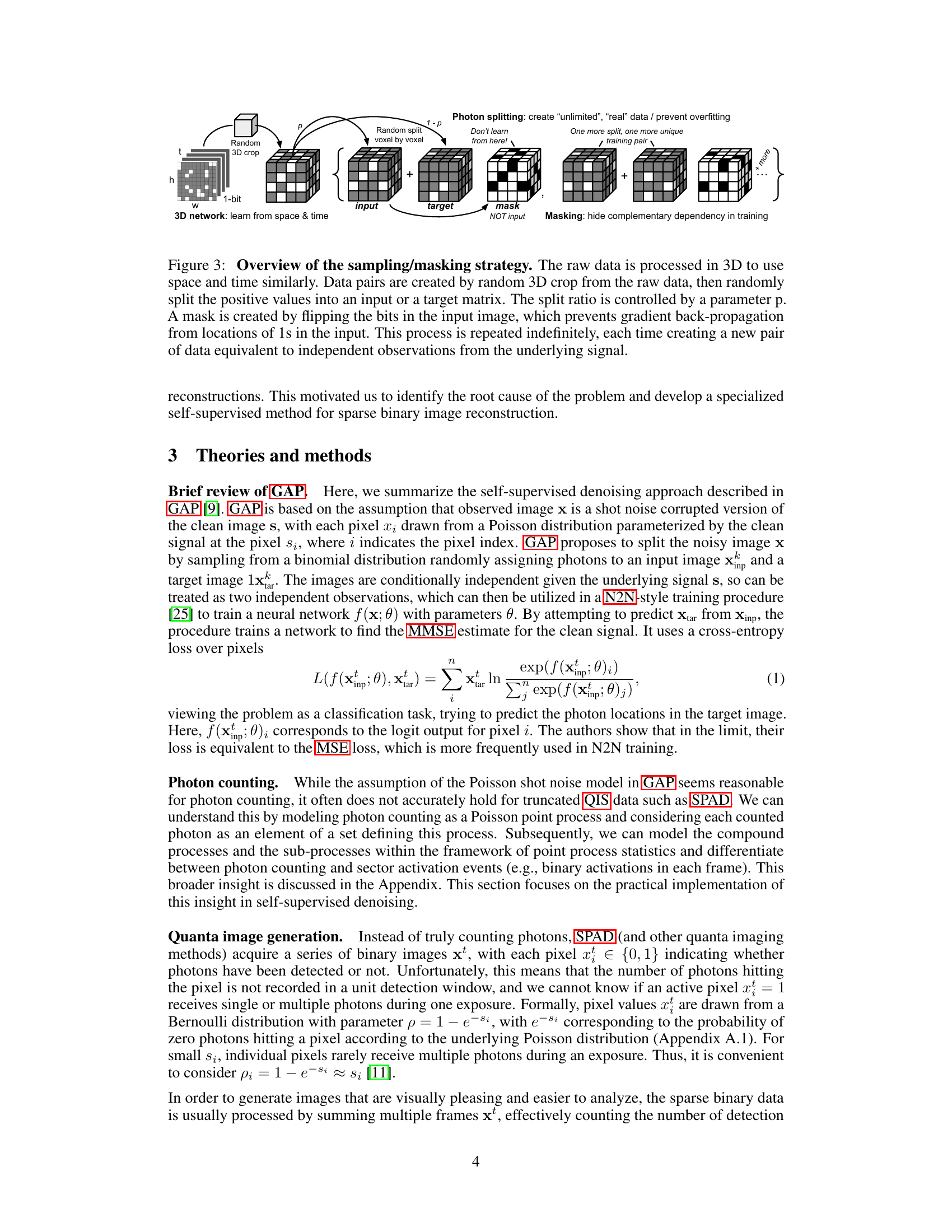

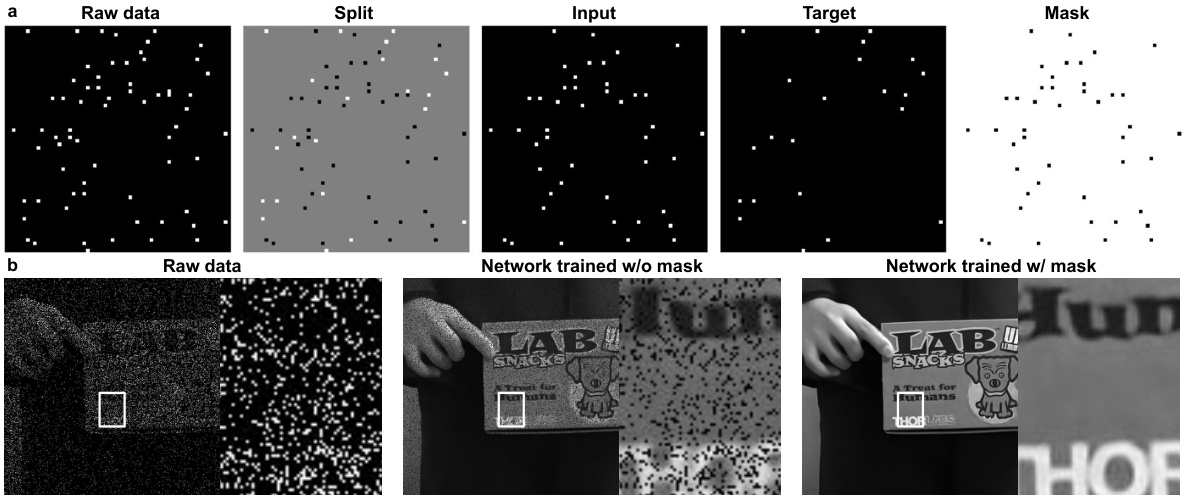

This figure illustrates the data sampling and masking strategy used in the bit2bit method. The raw 3D SPAD data is randomly cropped. Then, a voxel-wise random split assigns each photon detection event to either an input or target matrix, controlled by parameter p. A mask, created by inverting the input, prevents the network from learning the deterministic relationship between input and target matrices (i.e., if a pixel is 1 in the input, it cannot be 1 in the target). This process repeats to generate numerous training pairs from a single data sample.

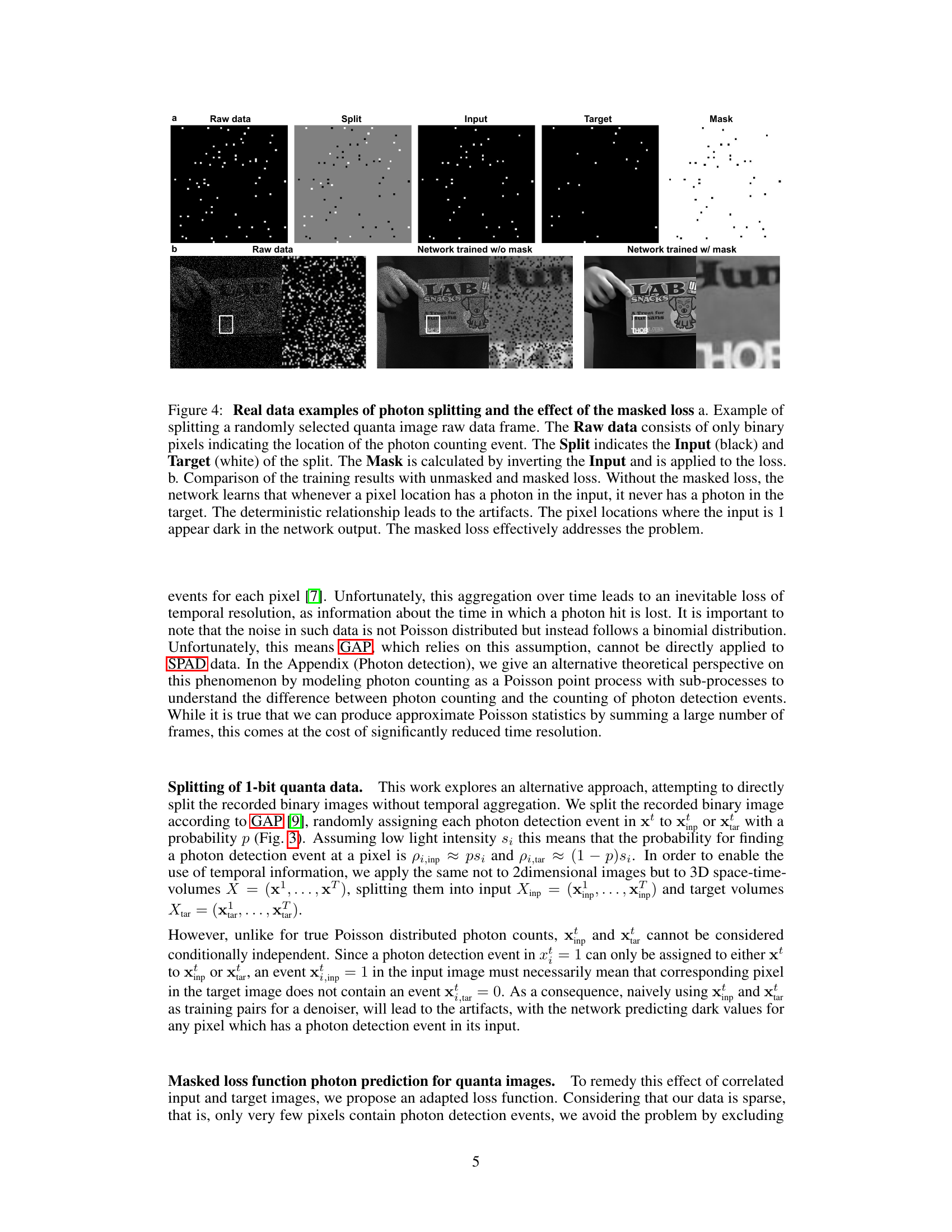

This figure demonstrates the effect of the proposed masked loss function on real SPAD data. Part (a) shows the process of splitting a raw data frame into input and target data, highlighting the creation of a mask to prevent overfitting. Part (b) compares the results of training with and without the mask. The masked loss successfully avoids artifacts caused by deterministic relationships between input and target images, producing significantly better results.

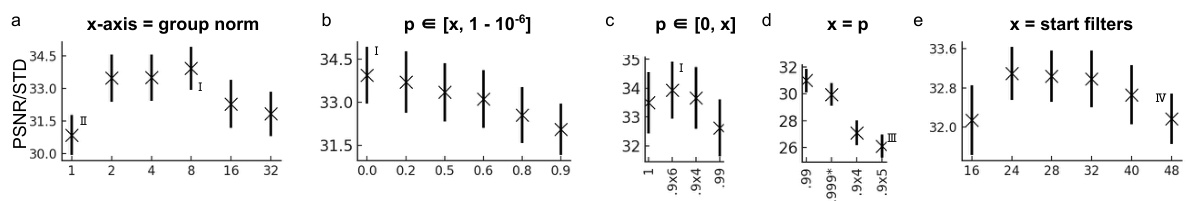

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of different hyperparameters and design choices on the performance of the proposed model. Specifically, it explores the effect of group normalization, the range of the thinning probability (p), and the model size on the PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) metric. Each subplot shows the results for a specific hyperparameter or design choice, with error bars indicating the standard deviation. The Roman numerals in the figure refer to corresponding images in Figure S3, which presumably show example reconstructions under the tested conditions. The numerical values are detailed in supplementary tables S2-6.

This figure compares the results of the proposed bit2bit method with the state-of-the-art Quanta Burst Photography (QBP) method using real SPAD data. Subfigure (a) shows different visual representations of the raw data and the reconstructed videos, highlighting the improved visual quality of bit2bit. Subfigure (b) provides a detailed analysis of a height-time slice through the video data, comparing the raw data with the bit2bit reconstruction and showing the ability of bit2bit to capture sub-pixel movements that are lost in the QBP method.

This figure illustrates the self-supervised sampling and masking strategy used in the bit2bit method. The raw 3D data (space and time) is randomly cropped, then split into input and target matrices. A masking step prevents learning from the input’s ‘1’ values, addressing the issue of complementary dependency in training pairs. This process creates numerous training pairs from limited data, enhancing performance and mitigating overfitting.

This figure demonstrates the process of photon splitting and the effect of using a masked loss function. (a) shows the steps involved in splitting a raw data frame into input and target matrices, along with the creation of a mask. The mask is used in training to prevent the network from learning deterministic relationships between input and target pixels, reducing artifacts. (b) compares results with and without the masked loss, showing how it effectively improves reconstruction quality by mitigating the artifacts generated by correlated input and target images.

This figure illustrates the self-supervised sampling and masking strategy used in the bit2bit method. The raw 3D SPAD data is cropped randomly, then split voxel-wise into input and target matrices. The split ratio is adjustable via parameter ‘p’. A mask inverts the input, preventing gradient updates from locations of ‘1s’, ensuring independence and creating numerous training pairs from limited data. This strategy effectively addresses the problem of complementary dependency between the input and target pairs in 1-bit quanta data. This process is iteratively performed to generate an unlimited number of training pairs.

This figure demonstrates the effect of the proposed masked loss function in addressing the correlation between input and target images created by the photon splitting process. The left panel (a) shows an example of how a raw quanta image is split into input and target matrices, along with the generated mask. The right panel (b) compares the results of training with and without the masked loss, highlighting the significant improvement in image quality achieved by masking.

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of different hyperparameters on the performance of the proposed method. Specifically, it shows how changes in group normalization, the range of the thinning probability (p), fixed large p values, and model size affect the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR). The results are presented graphically, showing trends for PSNR across different parameter settings. References to supplemental tables and figures are provided for more detailed numerical results.

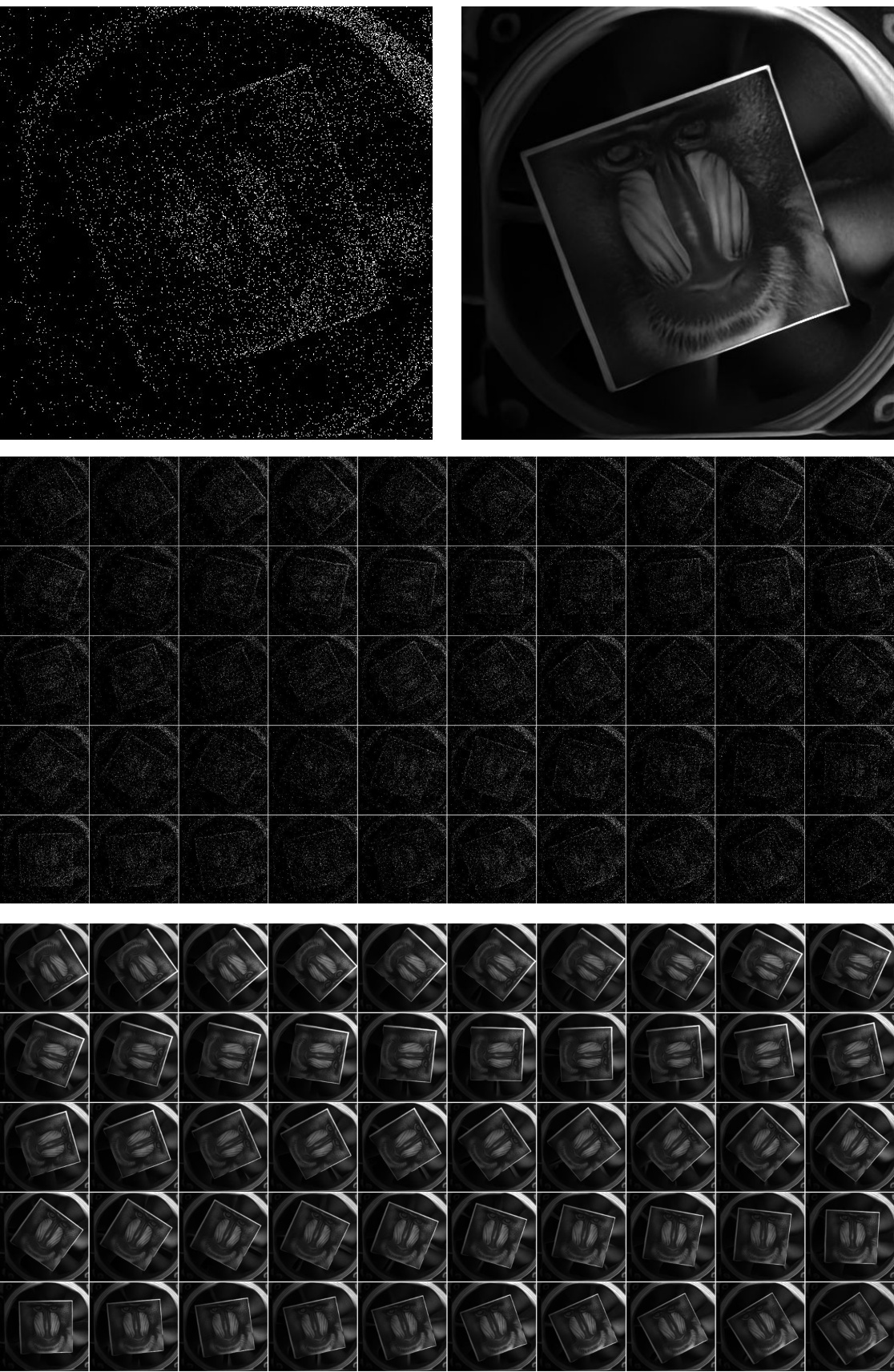

This figure shows example real SPAD data and its reconstruction. The scene is a sticker of a mandrill image rotating on a CPU fan in a dark room with low light. The figure displays the raw SPAD data, the reconstruction result, 50 frames of raw data with 50 frames skipped, and the corresponding reconstruction frames. The data demonstrates the effectiveness of the method in handling low light and motion conditions.

This figure shows a real SPAD data and its reconstruction of plasma ball. The data was acquired using a high-speed camera triggered at a similar frequency to the plasma release, capturing a 6ns snapshot of the event. The reconstruction shows the flow of plasma in a series of frames, illustrating the ability of the method to reconstruct high-speed events from sparse binary data.

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method to real SPAD data from a sonicator and bubbles experiment. The top row displays the raw SPAD data, which shows a chaotic scene with many small, rapidly moving bubbles. The bottom row shows the reconstructed images, which are significantly clearer and more interpretable than the raw data. The middle row shows 50 frames of the raw data, which highlight the dynamic nature of the scene and the challenges involved in reconstructing a clear image from such data. The results demonstrate that the proposed method is capable of reconstructing high-quality images from extremely noisy and sparse SPAD data, even in challenging imaging conditions.

This figure shows a comparison of different methods for reconstructing a 3D volume from photon-sparse confocal microscopy data. The top row displays the input data, a high SNR reference image, results using the original GAP method, and the results from the proposed bit2bit method. The bottom rows show raw data and reconstructions from key z-slices.

This figure shows a comparison of different methods for reconstructing a 3D confocal volume from photon-sparse data. The top row shows the input data, a high SNR reference, the result from the original GAP method, and the results from the proposed method. The bottom rows show the raw data and reconstruction for key z-slices.

This figure shows the reconstruction of a video of a CPU fan with camera motion using the proposed method. The top row displays the raw SPAD data (left) and the corresponding reconstruction (right). The middle row shows 50 frames of the raw data, and the bottom row shows the reconstructed frames. This experiment showcases the method’s ability to reconstruct high-quality video from noisy, sparse data under dynamic conditions.

This figure displays example results obtained using real SPAD data. The top row shows the raw SPAD data for different scenarios (CPU fan with motion, H&E slide, sonicating bubbles, USAF 1951 target with drill, and plasma ball). The middle row presents the corresponding reconstructions generated by the proposed method. The bottom shows additional keyframes. The rightmost image shows a color-coded accumulation of 50 frames.

This figure showcases the results of applying the proposed bit2bit method to various real-world SPAD datasets. The top row presents the raw, noisy SPAD data from different scenes (CPU fan with motion, H&E stained slide, sonicating bubbles, USAF 1951 resolution target with drill, and plasma ball). The middle row displays the corresponding reconstructions generated by the bit2bit method. Notably, the reconstruction achieves high-quality images at the original spatiotemporal resolution even with extremely sparse photon data. The figure highlights the capability of the method to handle various challenging imaging conditions (strong/weak ambient light, strong motion, and ultra-fast events).

This figure compares the results of the proposed method with those of Quanta Burst Photography (QBP) using real SPAD data showing a person playing a guitar. Subfigure (a) shows a comparison of raw data, QBP reconstruction, and the proposed method’s reconstruction. Subfigure (b) shows height-time slices of the raw data and the method’s reconstruction, highlighting the temporal resolution improvement. The differences between adjacent frames in the reconstruction demonstrate the capture of sub-pixel movements.

This figure displays a comparison of different methods for reconstructing images from photon-sparse confocal 3D data. The top row shows the input data (very low SNR), a high SNR reference image, and reconstructions using the GAP 2D method and the proposed ‘ours’ method. The following rows show the raw data and reconstructed data for several z-slices through the 3D volume. The results highlight that the proposed method improves the quality of the reconstruction compared to the GAP 2D method, although quantitative metrics (PSNR/SSIM) are not provided due to variations in acquisition conditions.

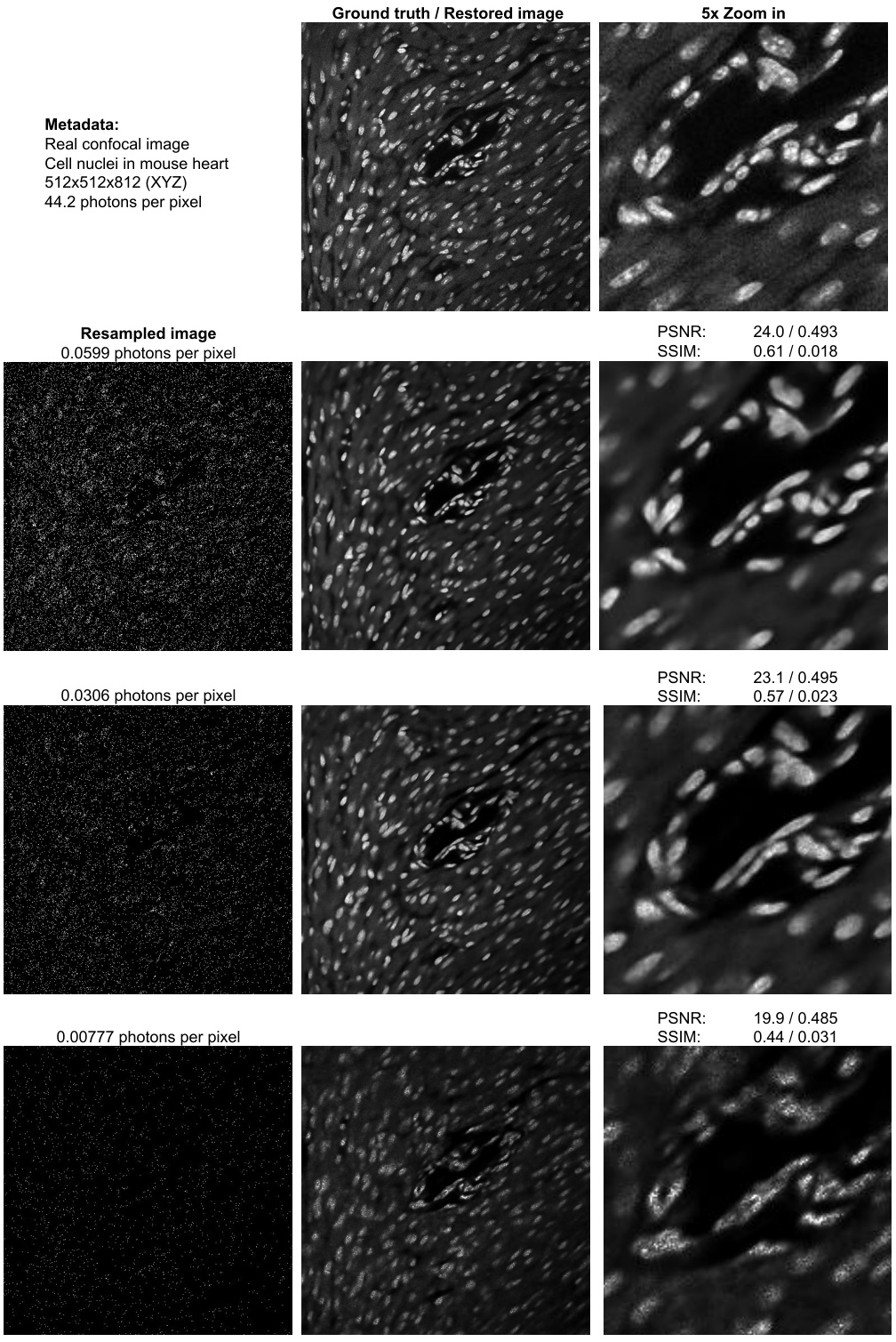

This figure presents a comparison of results from a simulated photon-sparse confocal 3D volume. The top row shows the ground truth, the restored images (using the method described in the paper), and zoomed-in views. The subsequent rows show the results of resampling the data at different photon counts (0.0599, 0.0306, and 0.00777 photons per pixel) to mimic the sparsity of SPAD data and demonstrate how the method performs at lower photon counts. The PSNR and SSIM values are provided for each level of resampling. This shows the ability of the method to reconstruct images despite the extremely sparse nature of the input data.

This figure shows the validation loss curve during the training of a Noise2Noise (N2N) model. The x-axis represents the training steps, while the y-axis shows the validation loss. The plot reveals that the validation loss starts increasing from a very early stage of training. This indicates a potential problem with the model’s ability to generalize well to unseen data, suggesting overfitting to the training data.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of different methods for quanta image reconstruction on simulated and real data. The methods compared include supervised learning, Noise2Noise, Noise2Void, Generative Accumulation of Photons (GAP), and the proposed bit2bit method. The table shows the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) values for each method, with and without masking, for both 2D and 3D reconstructions. It provides a quantitative comparison of the methods’ performance and helps highlight the benefits of the proposed bit2bit method.

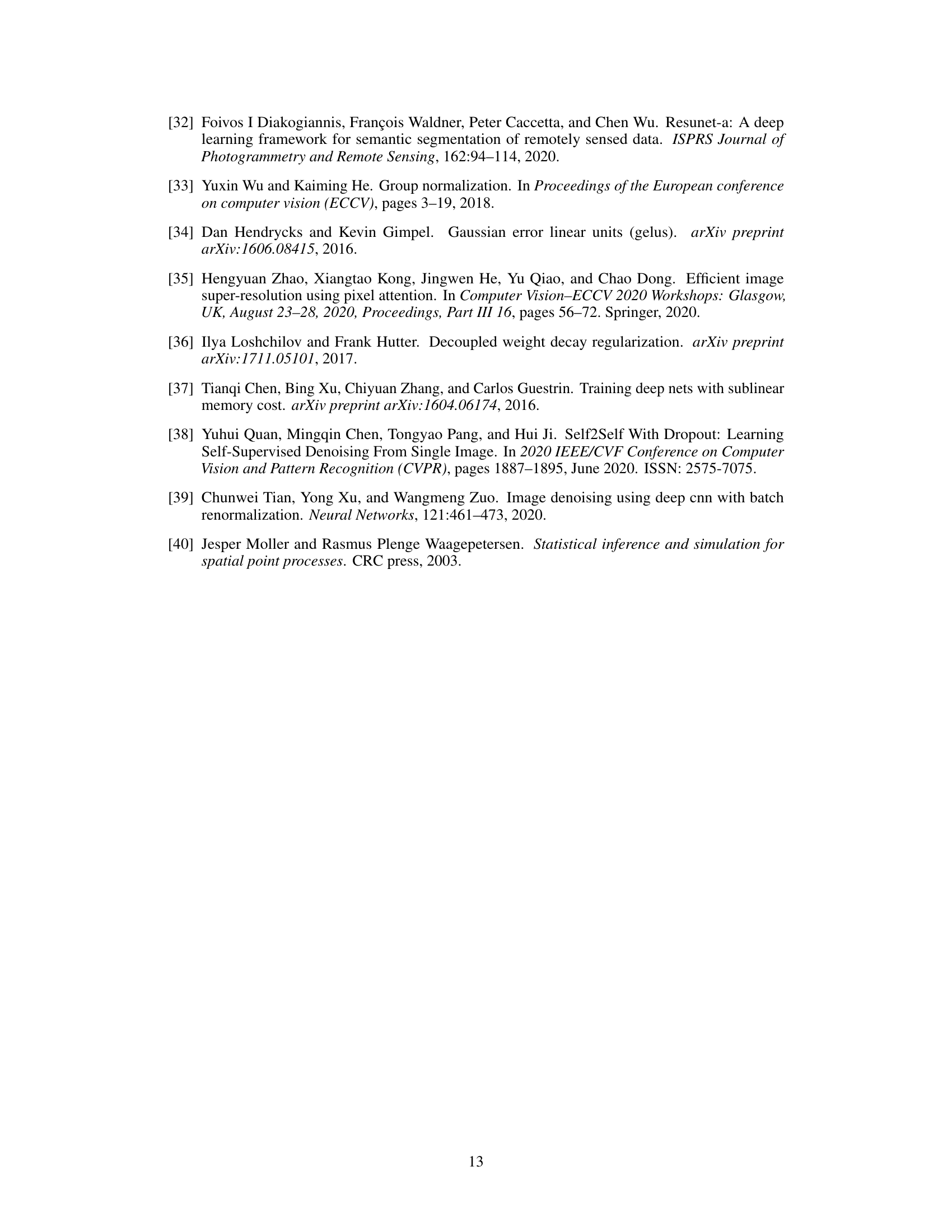

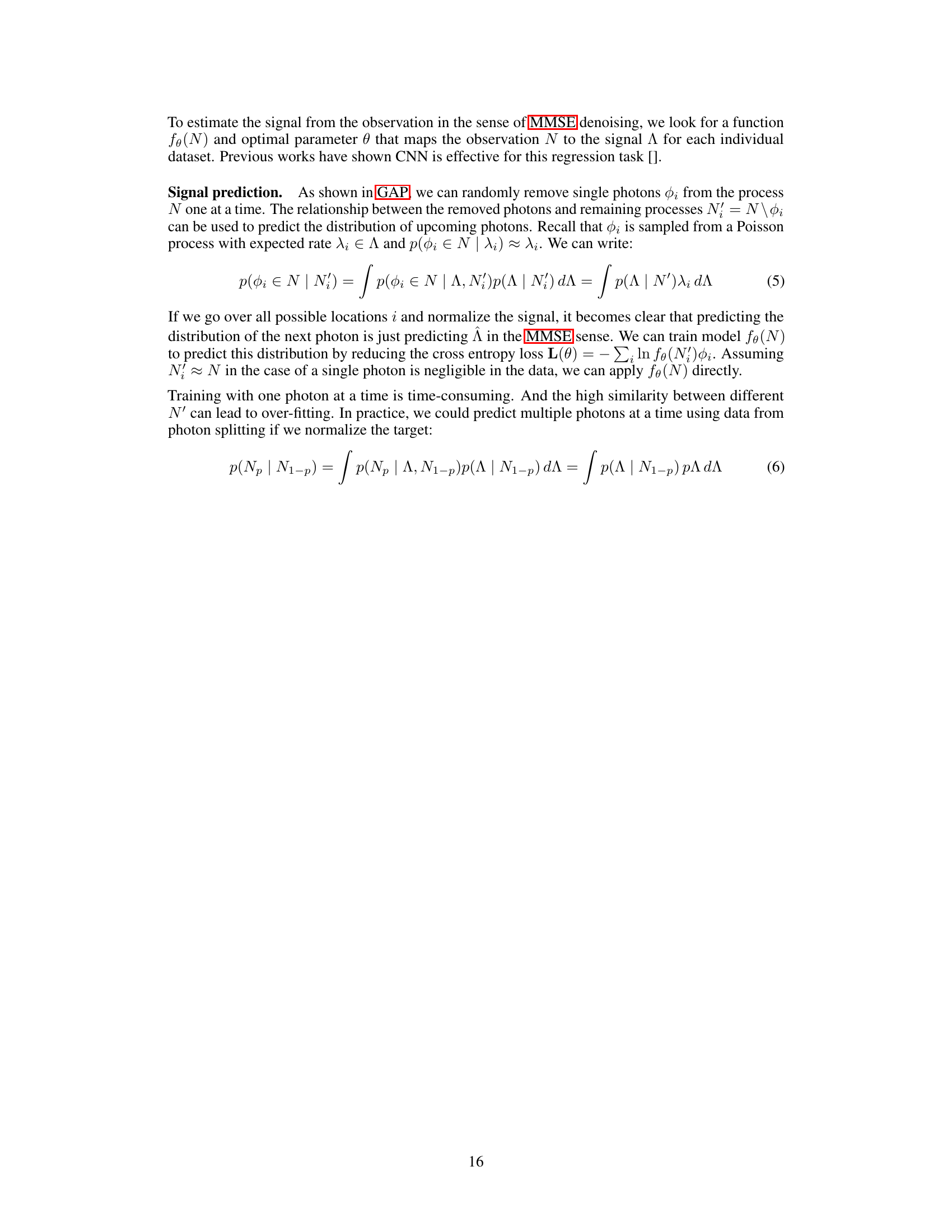

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of group normalization on the performance of the proposed method. The experiment varied the group normalization size (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32) and measured the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) as metrics to evaluate image reconstruction quality. The results demonstrate that group normalization significantly improves both PSNR and SSIM, with the best performance achieved at a group normalization size of 8.

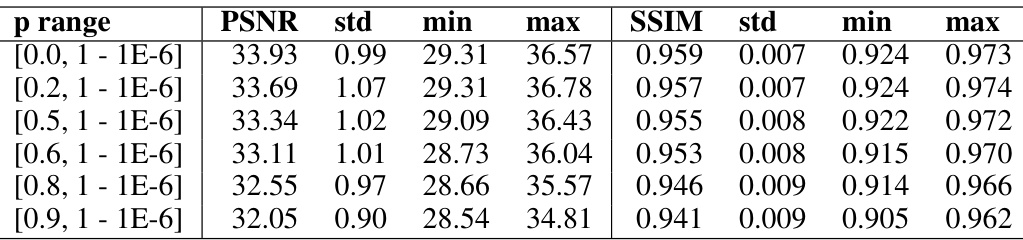

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the lower bound of the Bernoulli sampling probability (p) used in the proposed self-supervised method. It shows how the PSNR and SSIM metrics vary across different lower bounds of p, demonstrating the impact of this hyperparameter on the reconstruction quality. Lower values of p generally result in lower PSNR and SSIM.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the upper bound of the Bernoulli sampling probability parameter (p) used in the proposed method. It shows how different ranges of the upper bound of p affect the PSNR and SSIM metrics. The results indicate that the choice of upper bound has a significant impact on the performance, suggesting the need for careful tuning of this hyperparameter.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effect of fixing the parameter ‘p’ in the proposed method. The study evaluates the impact of different fixed values of ‘p’ on the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), key metrics for image reconstruction quality. The results show how the choice of a fixed ‘p’ value affects the performance of the method, indicating potential overfitting or other issues related to the choice of ‘p’.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method (bit2bit) against several other methods (supervised, N2N, N2V, GAP) for reconstructing images from sparse binary quanta image data. The comparison is done using both 2D and 3D versions of the methods, with and without masking. The metrics used for comparison are PSNR and SSIM. The table also includes qualitative results (denoised patches) to visually demonstrate the performance of each method.

This table compares the performance of different image reconstruction methods on both simulated and real SPAD data. The methods compared include supervised learning, Noise2Noise (N2N), Noise2Void (N2V), Generative Accumulation of Photons (GAP), and the proposed bit2bit method. The table presents the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) values, along with visual examples of the reconstructions for each method, showcasing the effectiveness of the bit2bit method in reconstructing high-quality images from sparse binary data. The impact of masking on the reconstruction quality is also evident from the results.

This table presents a comparison of different image reconstruction methods on simulated and real SPAD data. The methods compared include supervised learning, Noise2Noise (with two variations), Noise2Void, Generative Accumulation of Photons (GAP), and the proposed bit2bit method (with and without masking). The evaluation metrics are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM). The table shows PSNR and SSIM values for 2D and 3D implementations of the methods, allowing for a comparison of performance across different dimensions and the impact of masking.

Full paper#