↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current multimodal Large Language Models (LLMs) primarily focus on scaling through increased data and model size, overlooking efficient vision-side improvements. This is computationally expensive and limits scalability. Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) has proven effective in scaling LLMs but hasn’t been widely applied to the vision component of multimodal models. This approach is costly and often unstable.

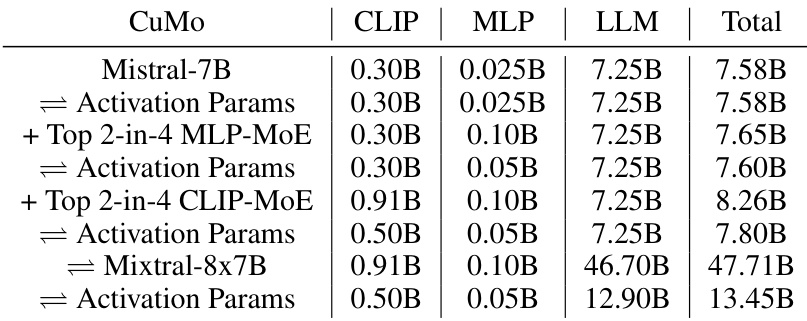

CuMo addresses these issues by introducing a novel co-upcycling method for integrating sparsely-gated MoE blocks into both vision encoders and MLP connectors. It pre-trains MLP blocks, initializes MoE experts from them, and employs auxiliary losses for balanced expert loading. Experiments demonstrate that CuMo surpasses other multimodal LLMs across various benchmarks, achieving state-of-the-art results within each model size group, while exclusively using open-sourced data. This demonstrates the potential of CuMo to significantly enhance the efficiency and performance of multimodal LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel and efficient approach to scaling multimodal LLMs, a critical area of current AI research. The use of co-upcycled Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) blocks significantly improves performance with negligible additional parameters at inference time. The work also tackles the challenge of efficiently scaling from the vision side and provides valuable insights into the design and training of large-scale multimodal models. This opens up new avenues of research into more efficient and powerful multimodal LLMs and helps address limitations in scaling existing approaches.

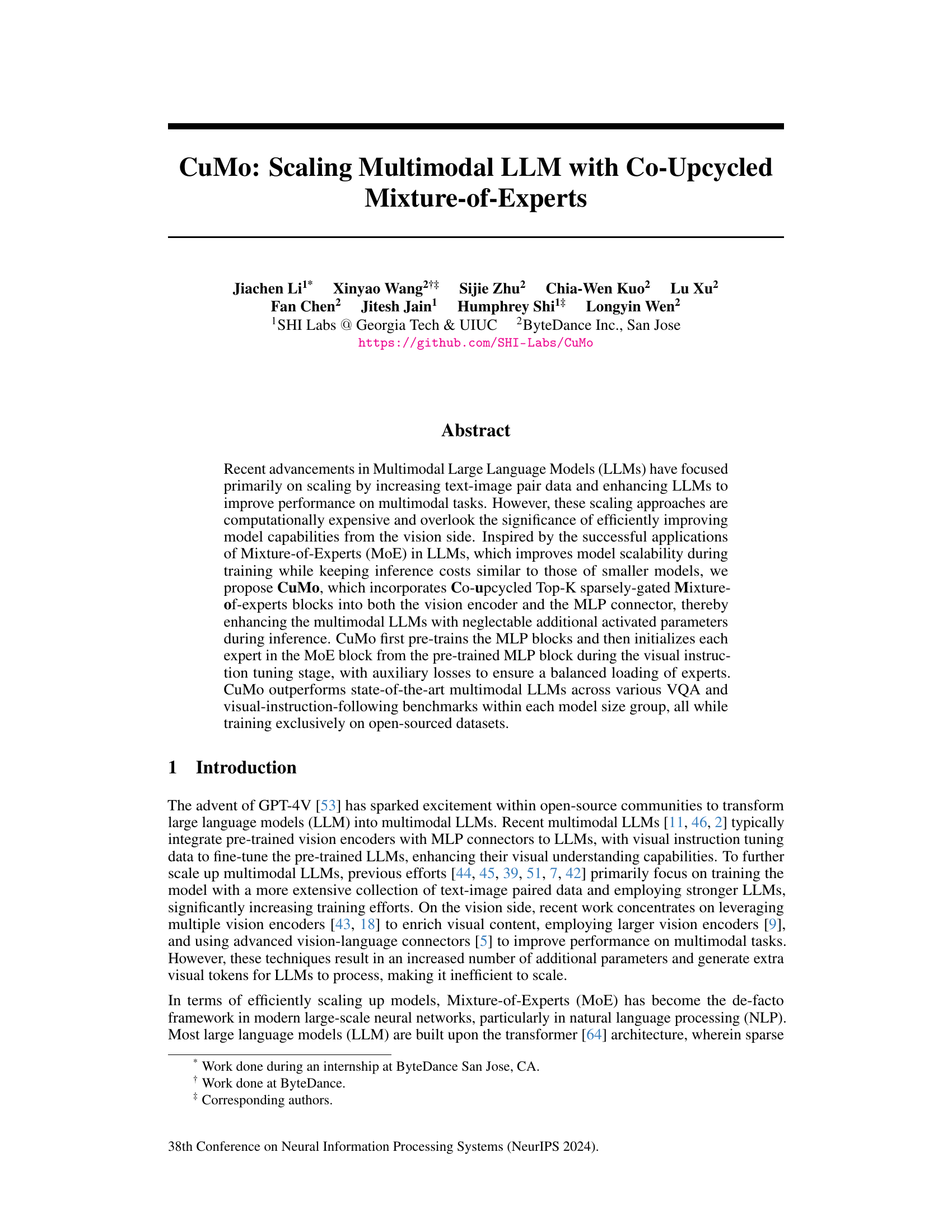

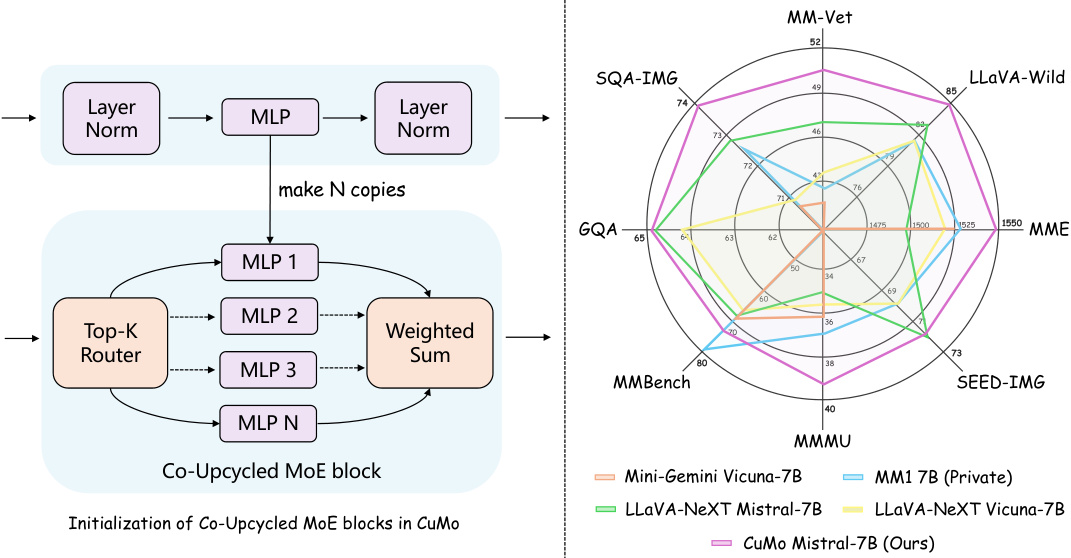

Visual Insights#

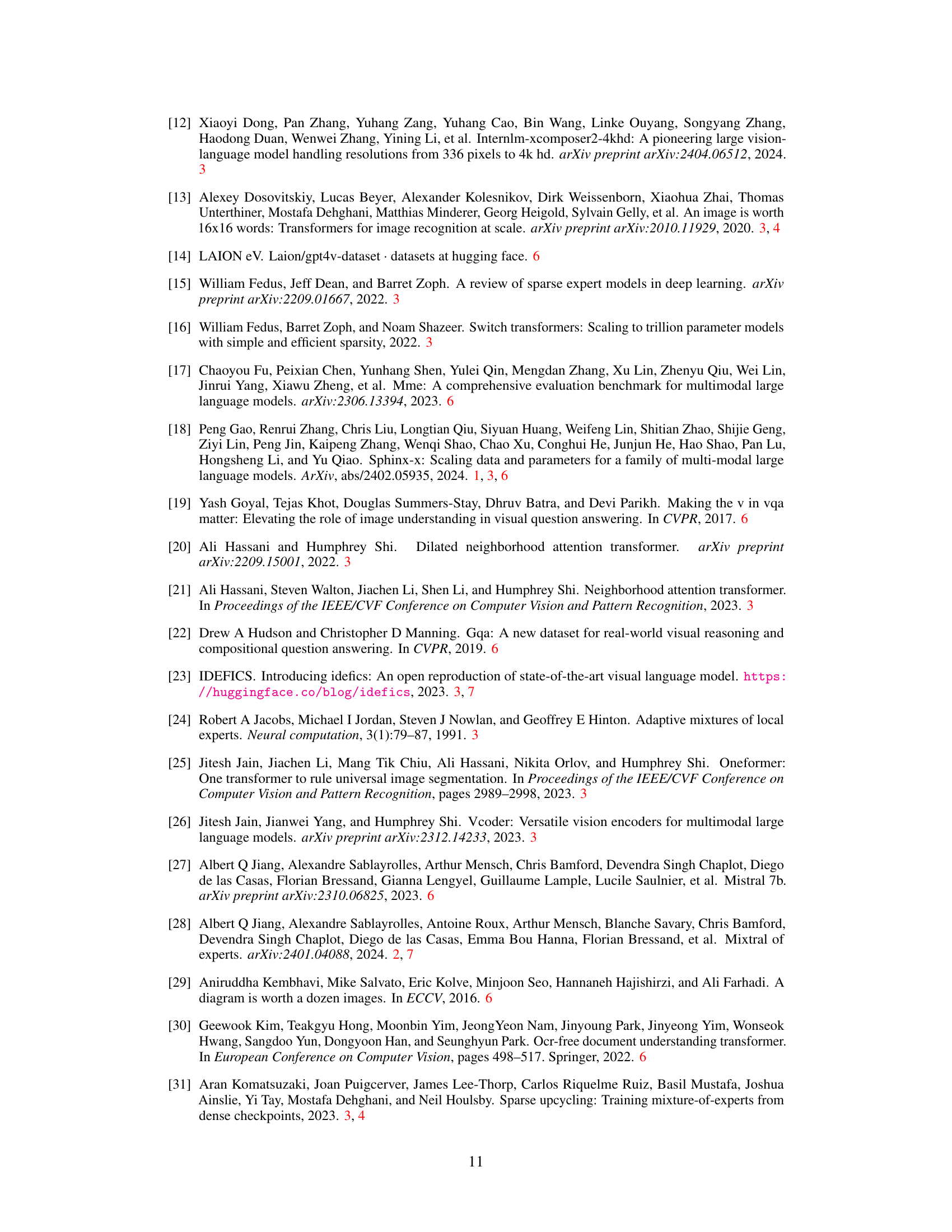

The figure demonstrates the architecture of CuMo’s co-upcycled Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) blocks, highlighting how each expert is initialized from pre-trained MLP blocks. The right panel shows a radar chart comparing CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs across various benchmarks, showcasing CuMo’s superior performance.

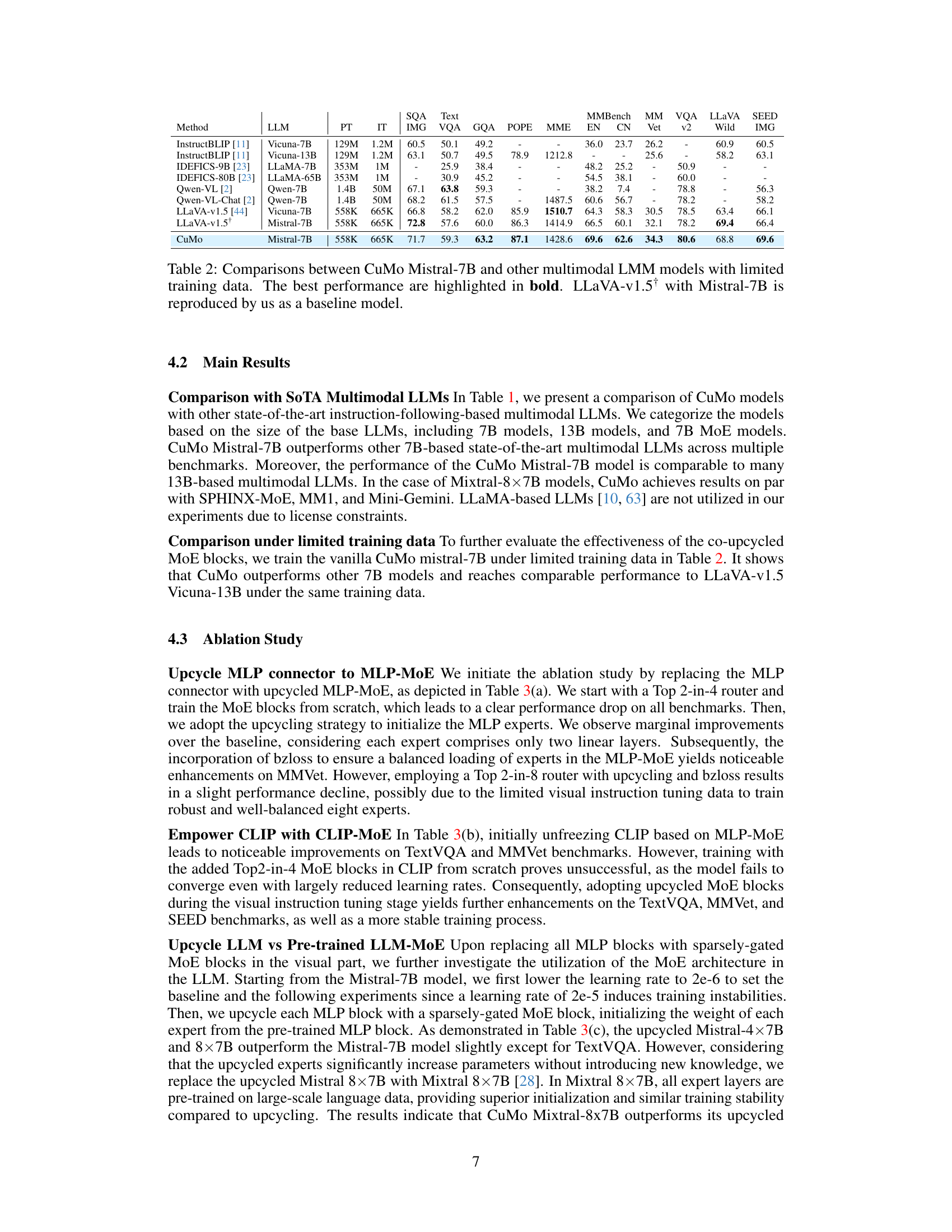

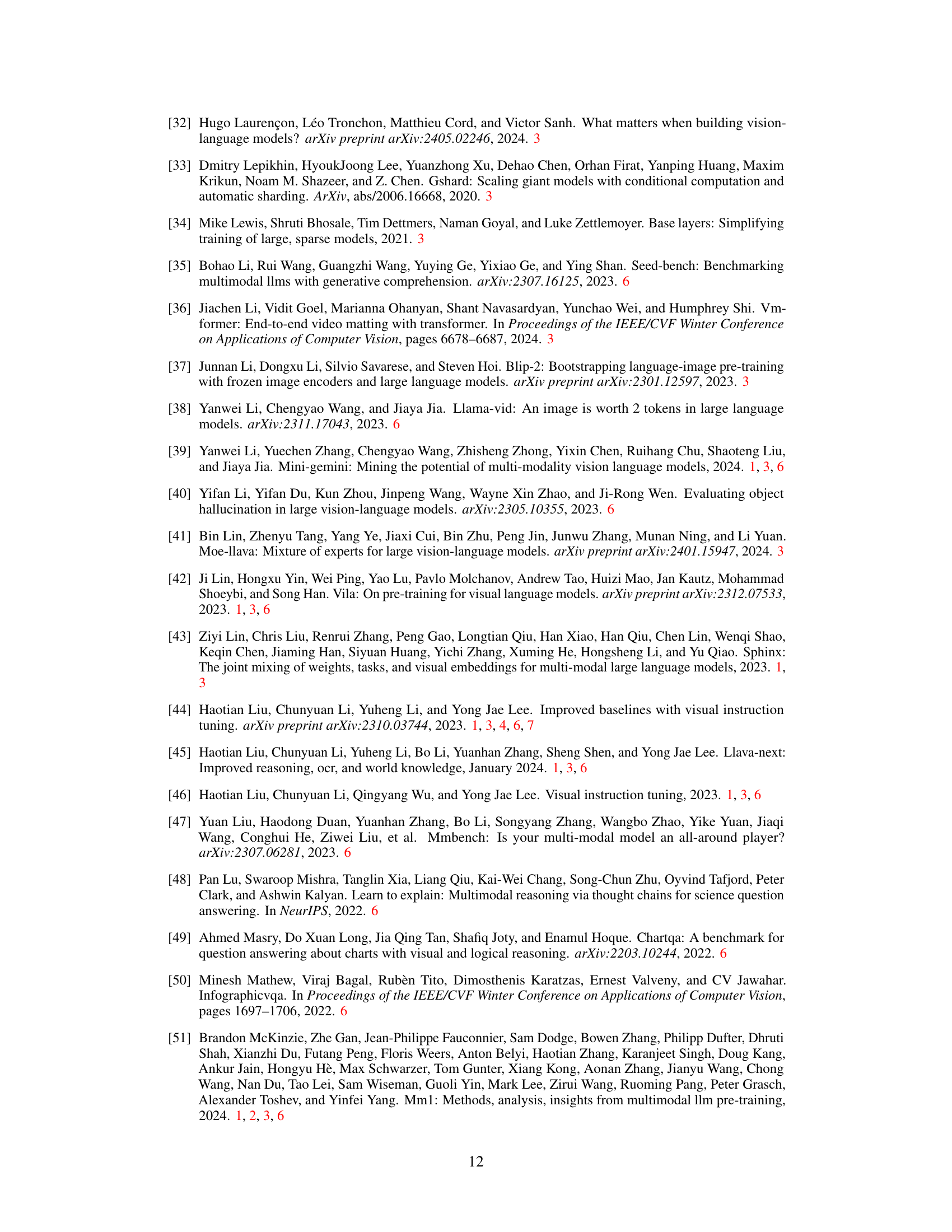

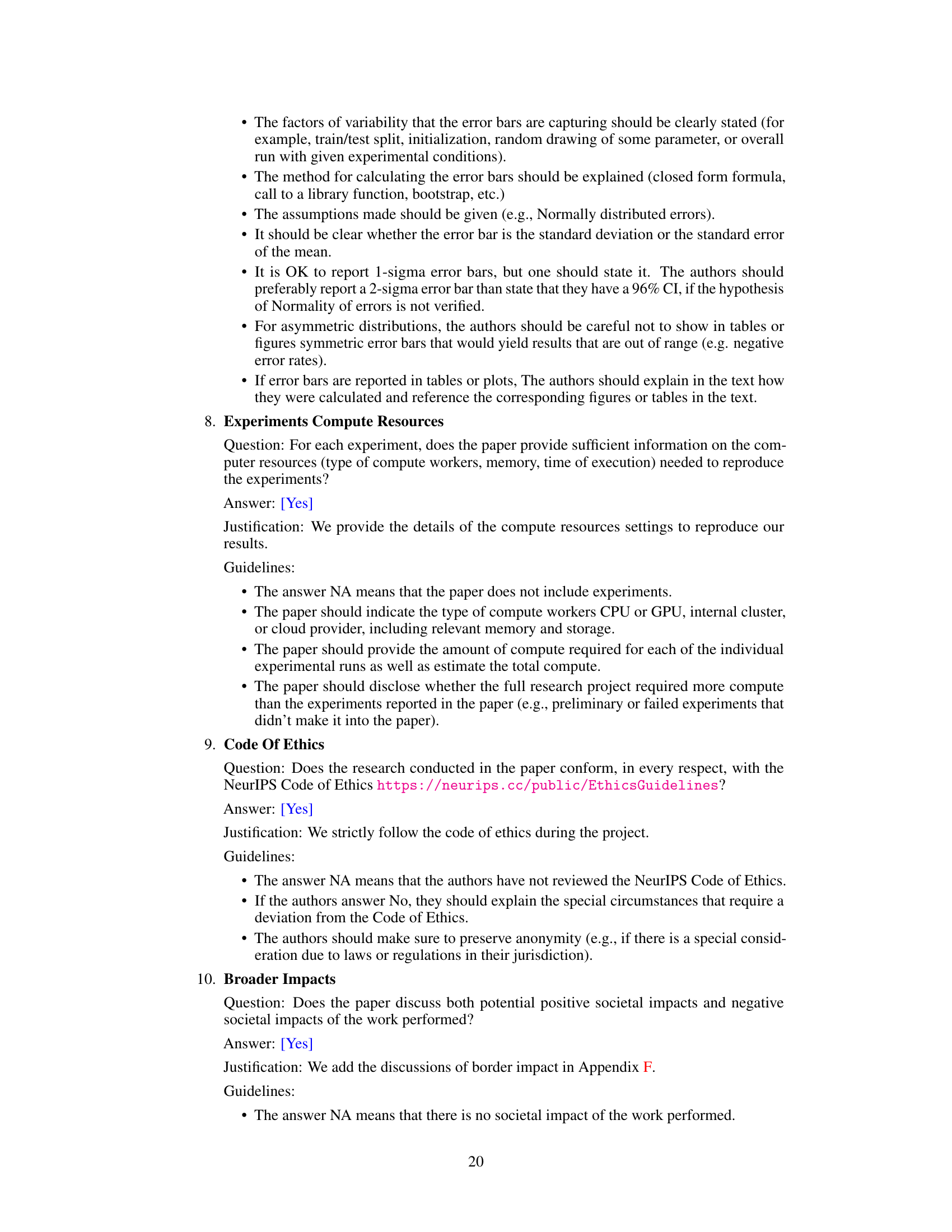

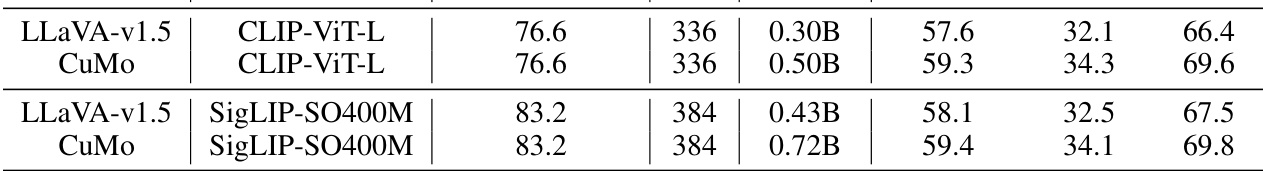

This table compares CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs across various benchmarks. Models are grouped by their base LLM size (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE). The table shows metrics for various tasks, including image understanding and question answering, and highlights CuMo’s superior performance within each model size group. The ‘Act.’ column represents the number of activated parameters during inference.

In-depth insights#

Co-Upcycled MoE#

The concept of “Co-Upcycled MoE” blends the efficiency of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models with a novel initialization strategy. Instead of training MoE components from scratch, which can be computationally expensive and unstable, this approach leverages pre-trained, dense Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) blocks. These MLPs, already possessing valuable features learned during previous training stages, serve as the foundation for initializing the MoE experts. This co-upcycling process dramatically reduces training time and improves stability. Furthermore, the use of sparsely activated MoE blocks ensures that during inference, only a subset of experts needs to be activated, maintaining similar computational costs to smaller models. By combining the knowledge gained from pre-trained MLPs with the efficiency of MoE, this technique likely results in significant performance improvements while remaining resource-efficient. The name “Co-Upcycled” highlights that the upcycling occurs across different model components (e.g., vision encoder and MLP connector), further optimizing the multimodal model. This innovative approach offers a pathway to scalable and efficient multimodal large language models.

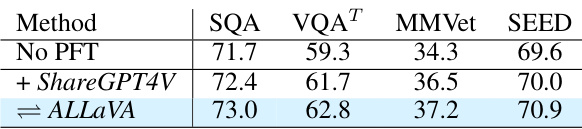

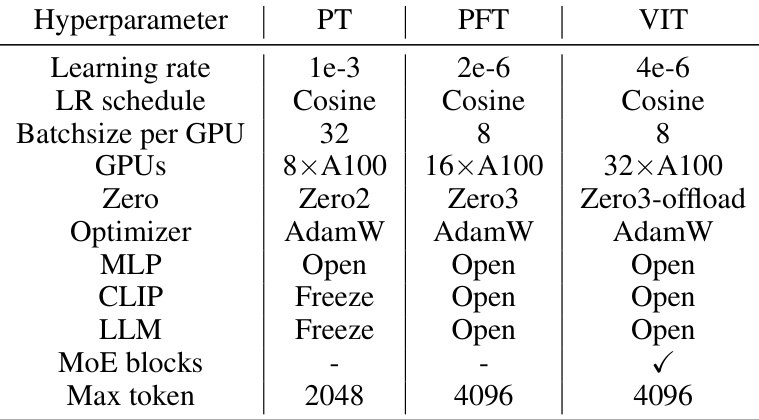

Three-Stage Training#

The proposed three-stage training methodology for CuMo is a key contribution, enhancing model stability and performance. Pre-training focuses on the MLP connector, preparing it for integration with the vision encoder and LLM. This stage ensures that the core components are well-aligned before adding the complexity of MoE. Pre-fine-tuning then trains all parameters, acting as a warm-up for the subsequent stage. Importantly, it allows the model to integrate the components prior to introducing the sparsity inherent in the MoE blocks. The final visual instruction tuning stage incorporates the sparsely-gated MoE blocks, leveraging the pre-trained weights for initialization and improved stability. Auxiliary losses ensure balanced loading of experts, preventing over-reliance on specific experts. This multi-staged approach is crucial, demonstrating the importance of a progressive training strategy for effectively scaling multimodal LLMs using MoE.

Visual MoE Impact#

The integration of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) into the visual processing components of a multimodal large language model (MLLM) presents a significant opportunity to enhance performance and efficiency. A ‘Visual MoE Impact’ analysis would explore how strategically placing MoE blocks within the vision encoder and/or vision-language connector affects various aspects of the model. Key considerations would include: the impact on parameter efficiency, as MoE allows for scaling model capacity without a proportional increase in computational cost during inference; the improvement in performance across different visual question answering (VQA) and instruction-following benchmarks, as the specialized experts within MoE modules could potentially achieve better accuracy; the robustness and stability of training, as careful consideration of the training strategy and auxiliary losses are vital for ensuring balanced expert utilization and convergence; and finally, an assessment of any increase in model latency introduced by the routing mechanism within MoE. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the ‘Visual MoE’ hinges on achieving a delicate balance between enhanced performance, improved resource efficiency, and training stability. Analyzing these factors provides critical insights into the viability and advantages of using MoEs specifically in the vision processing aspect of MLLMs.

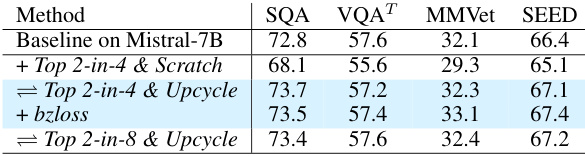

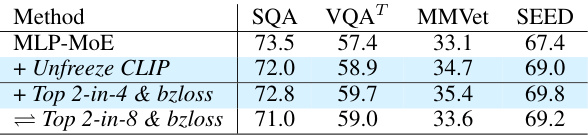

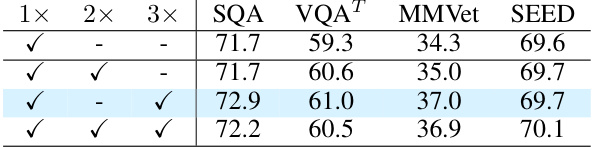

Ablation Study#

The ablation study systematically evaluates the contributions of different components within the proposed model. By selectively removing or altering specific modules (e.g., the MoE blocks in the vision encoder or MLP connector), the researchers assess the impact on overall performance across various benchmarks. This methodical approach helps isolate the effects of each component, providing evidence of their individual contributions and relative importance. Key findings from such a study might reveal, for instance, the extent to which the vision encoder’s MoE enhancement improves performance compared to its simpler MLP counterpart, or the degree to which balanced loading of experts, facilitated by auxiliary loss functions, stabilizes training and improves results. The ablation study thus provides crucial insights into the model’s architecture, highlighting its strengths and suggesting potential areas for improvement or simplification. The process is essential for establishing a clear understanding of which elements are integral to the model’s success and why they are beneficial.

Hallucination Limits#

The phenomenon of hallucination, where large language models (LLMs) generate incorrect or nonsensical outputs, presents a significant challenge in their practical application. Hallucination limits the reliability and trustworthiness of LLMs, especially in high-stakes scenarios where factual accuracy is crucial. While progress is being made in mitigating hallucinations through techniques such as improved training data, refined architectures, and fact verification methods, a complete elimination of hallucinations remains elusive. The inherent complexity of natural language and the probabilistic nature of LLMs contribute to this limitation. Furthermore, the trade-off between creativity and factual accuracy needs careful consideration; overly stringent constraints on generation might stifle the very creativity that makes LLMs useful. Therefore, research into robust methods for identifying and mitigating hallucinations is crucial for the advancement of safe and reliable LLM technology. Focusing on specific application domains to tailor hallucination mitigation strategies is also important, as the tolerance for inaccuracies varies significantly across contexts.

More visual insights#

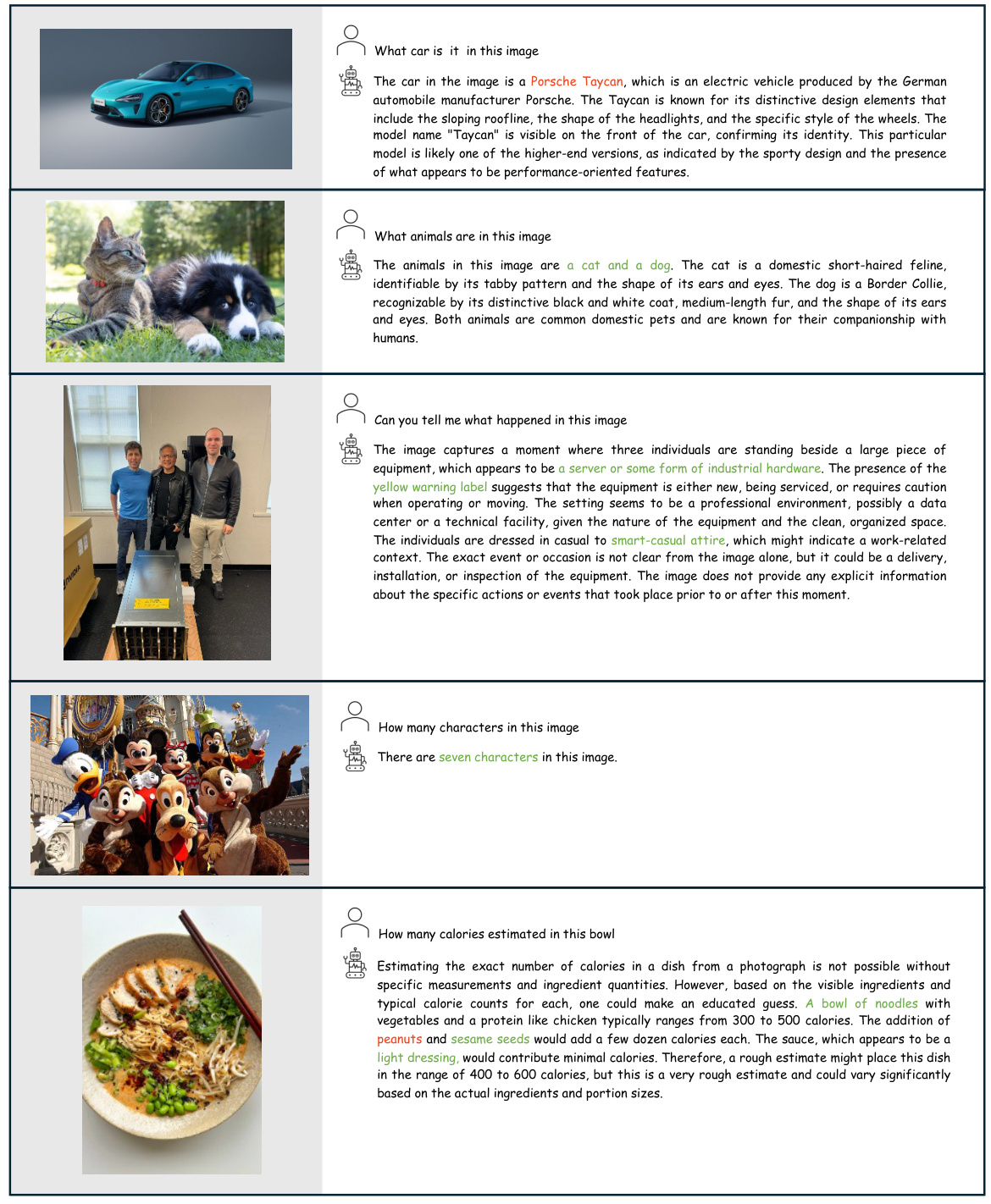

More on figures

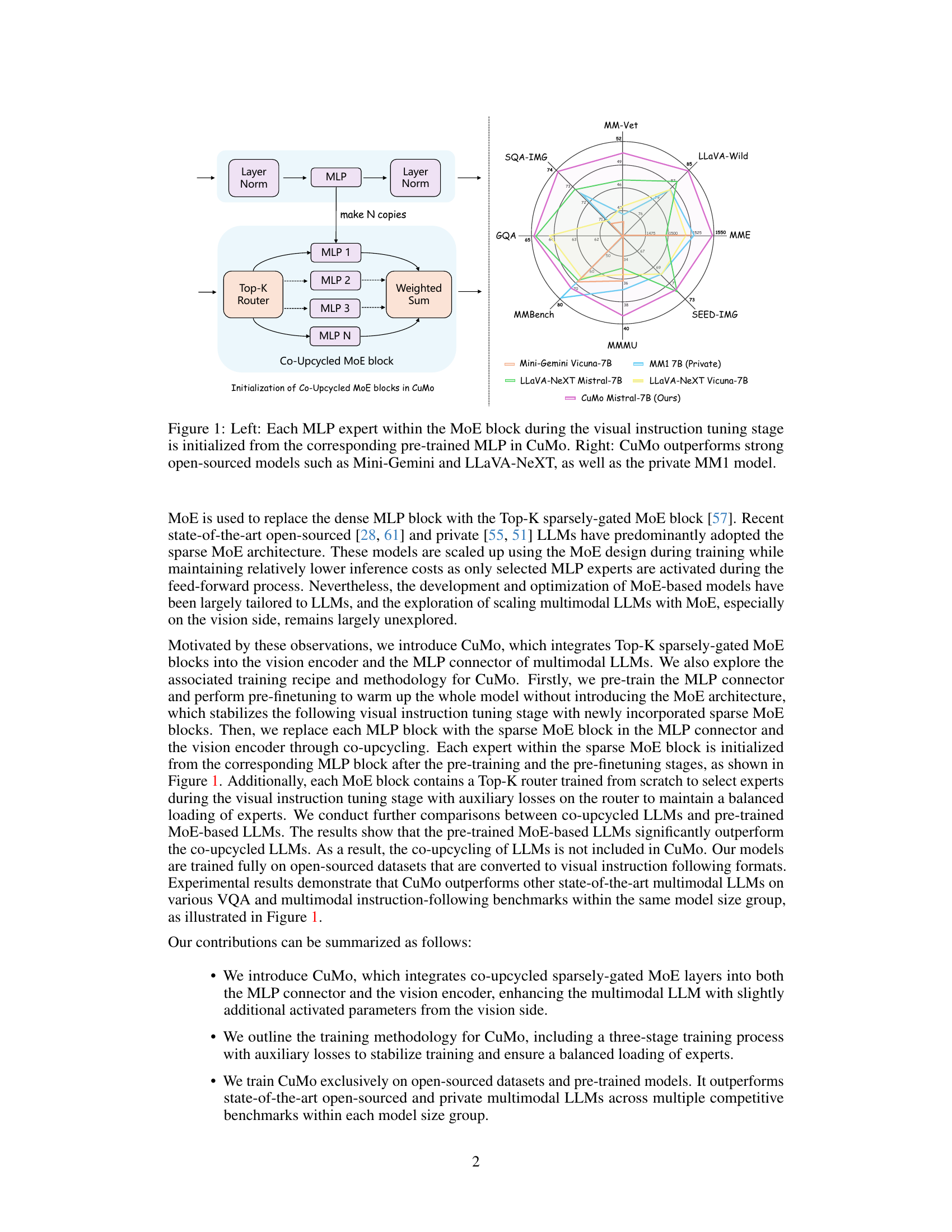

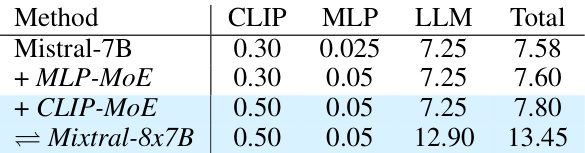

The figure illustrates the architecture of CuMo, a multimodal large language model. It shows how sparse Top-K Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) blocks are integrated into both the CLIP vision encoder and the MLP connector. This improves the model’s ability to process visual information and enhances its multimodal capabilities. The diagram simplifies the architecture by omitting skip connections for clarity. More detailed implementation information can be found in Section 3.2 of the paper.

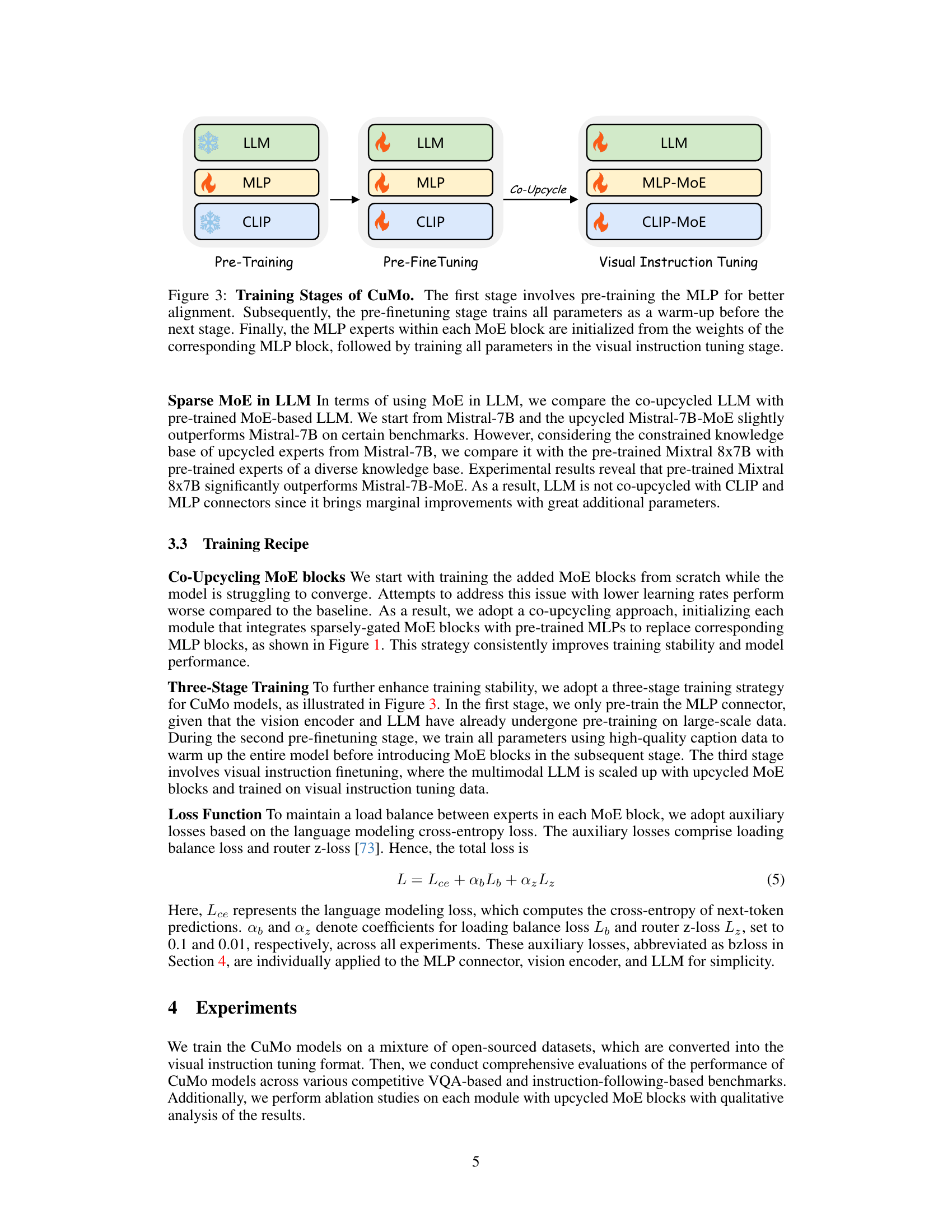

This figure illustrates the three-stage training process of CuMo. The first stage is pre-training the MLP, followed by pre-fine tuning of all parameters. The final stage is visual instruction tuning, where the MLP experts in the MoE blocks are initialized from the pre-trained MLP weights before training.

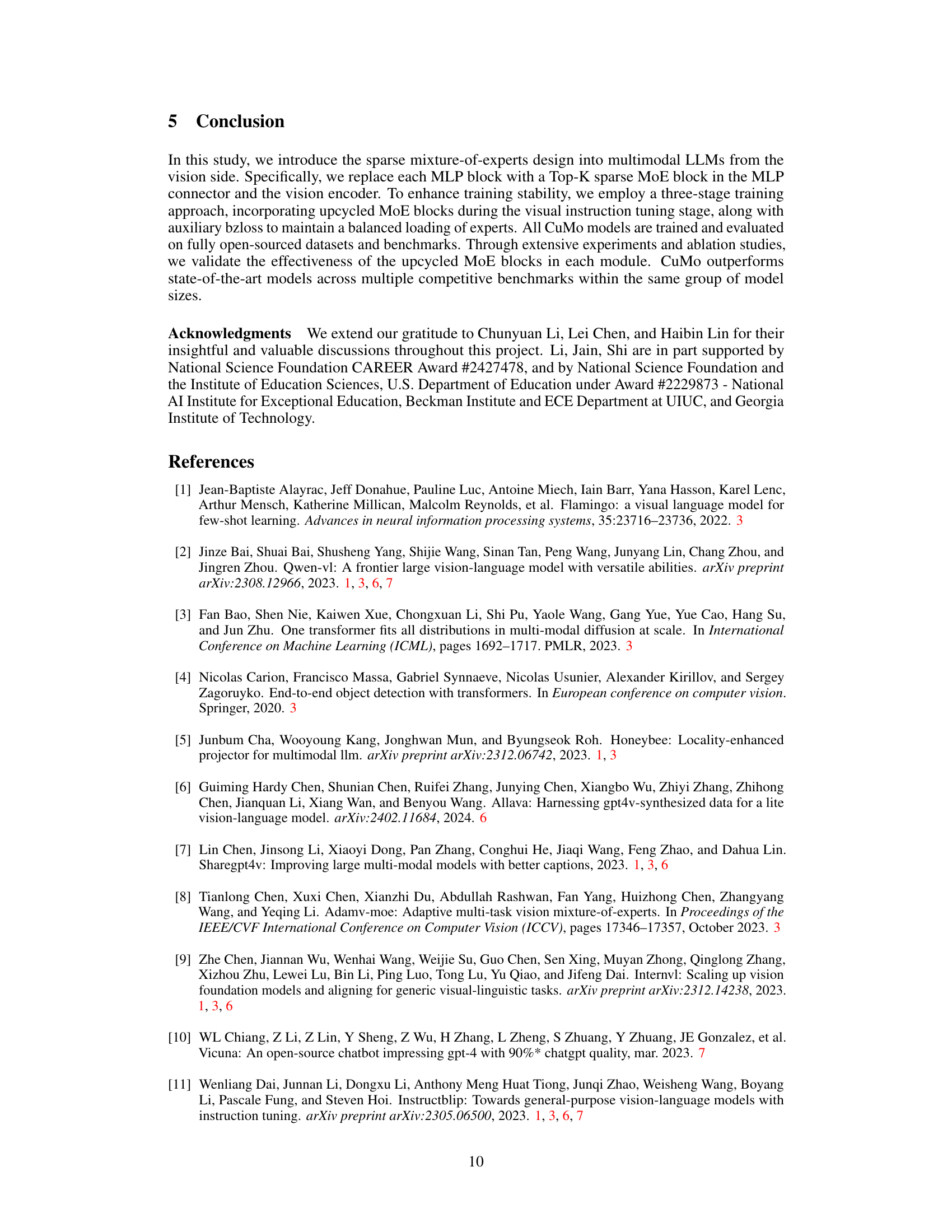

This figure visualizes the distribution of activated experts within the Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) blocks of the CLIP vision encoder during inference. It shows the percentage of times each expert is activated across different layers of the CLIP model for a specific benchmark (MME). The even distribution across experts demonstrates the effectiveness of auxiliary loss functions in balancing expert utilization during training.

The figure displays two key aspects of CuMo. The left panel illustrates the co-upcycling initialization of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) blocks, showing how each expert within the MoE is initialized using a pre-trained Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) from CuMo. The right panel presents a performance comparison of CuMo against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs (Mini-Gemini, LLaVA-NeXT, and a private model MM1) across several benchmarks, demonstrating the superior performance of CuMo.

The left panel of the figure shows the architecture of a co-upcycled Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) block used in CuMo. Each expert in the MoE block is initialized from a corresponding pre-trained Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) block. The right panel shows a comparison of CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs on various benchmarks. CuMo outperforms other models across different benchmarks.

More on tables

This table compares CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs across various benchmarks. Models are grouped by the size of their base LLMs (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE models). The table highlights CuMo’s superior performance in many cases, particularly considering the number of activated parameters during inference. Some results use an average of three GPT API queries.

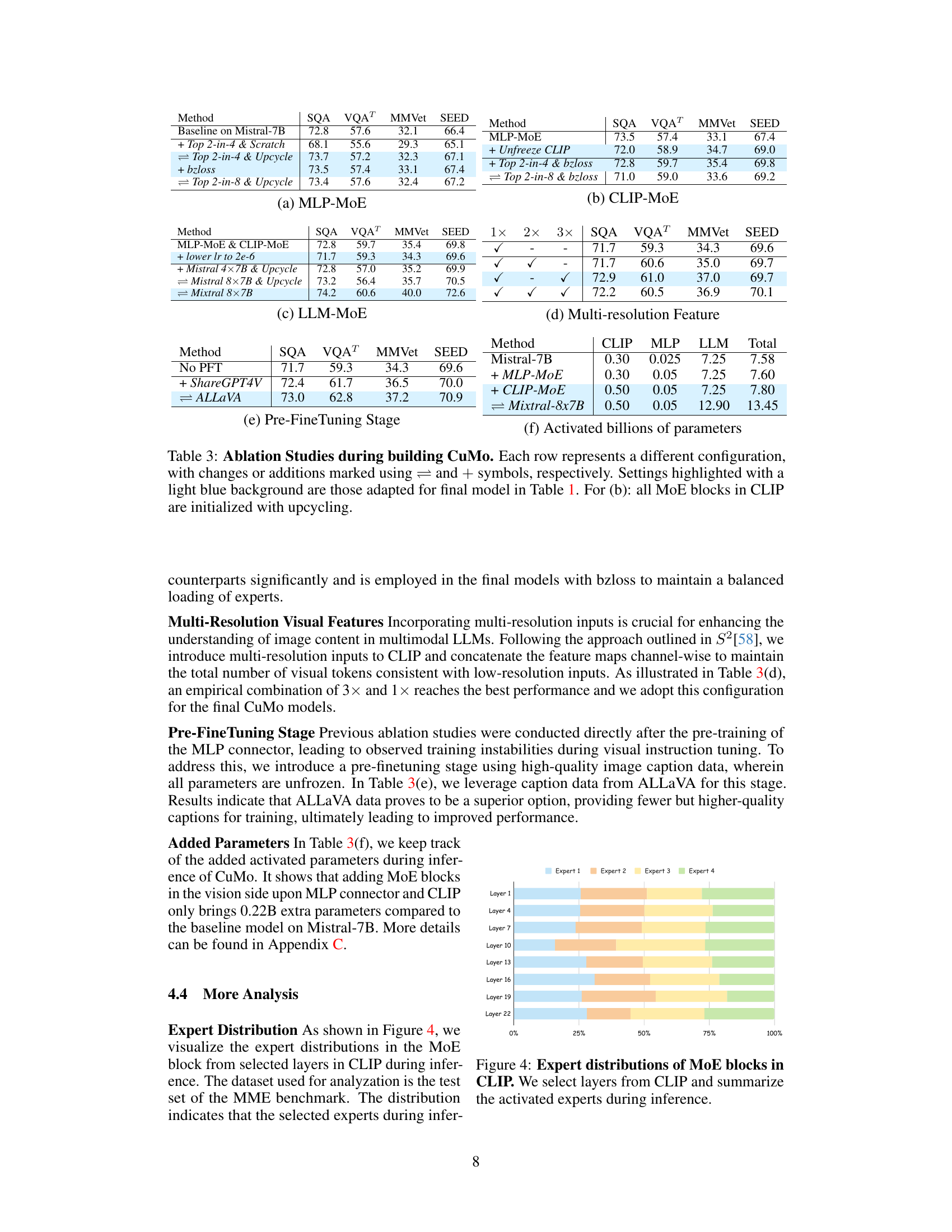

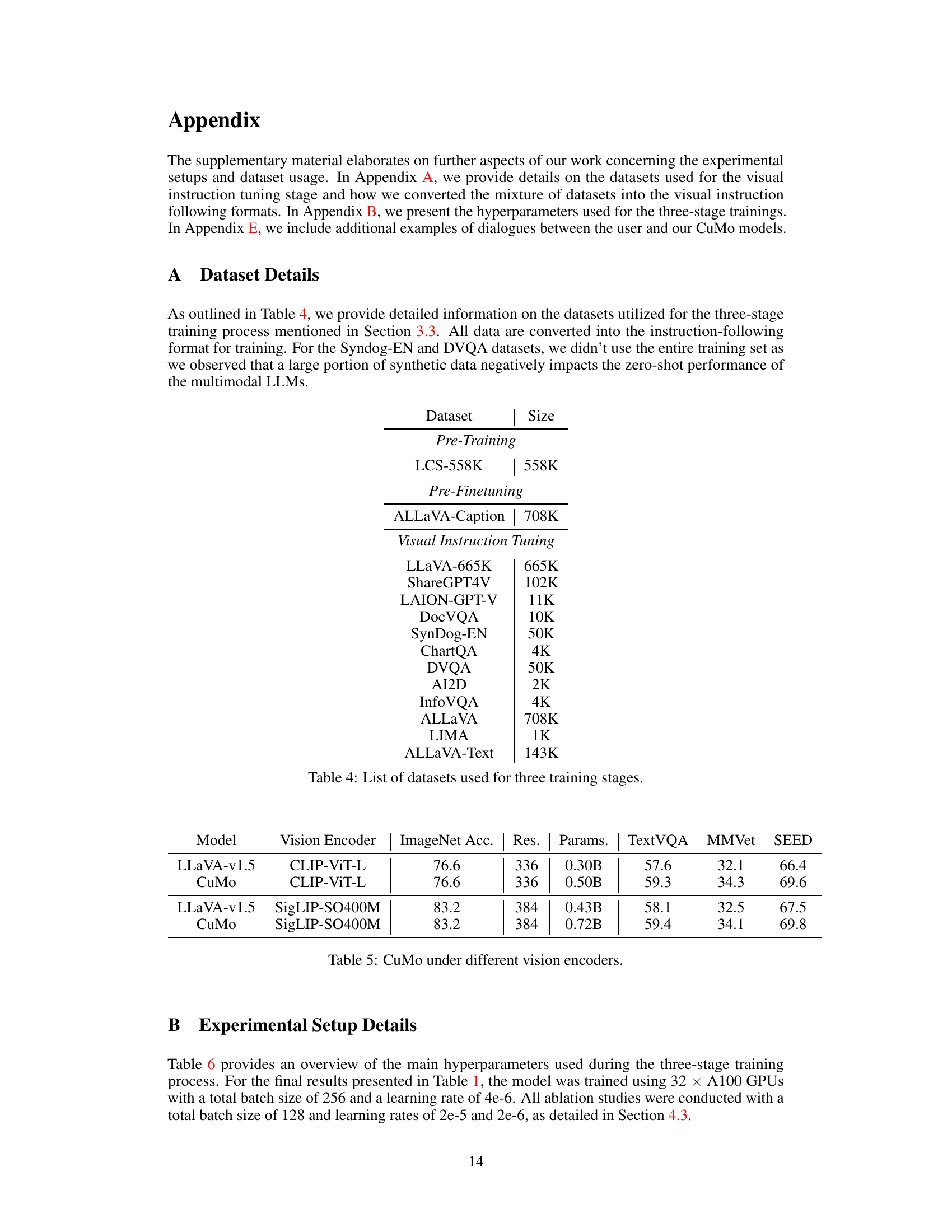

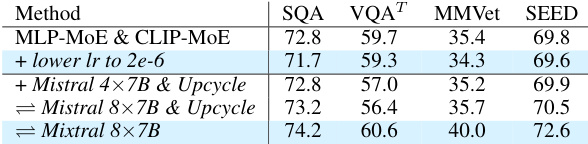

This ablation study investigates the impact of different design choices within CuMo, focusing on the incorporation of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) blocks in different components, including the MLP connector, CLIP vision encoder, and LLM. The table shows the impact on various metrics (SQA, VQAT, MMVet, SEED) for each configuration, comparing scratch training vs upcycling, and including or excluding auxiliary losses. The results illustrate the effectiveness of co-upcycling in stabilizing training and improving performance, as well as the impact of different MoE block configurations and auxiliary loss functions.

This table presents the ablation study results for the CuMo model. It shows the impact of different design choices on the performance of the model on various benchmarks, such as SQA, VQA, MMVet, and SEED. The rows indicate adding different MoE blocks and using different training strategies. The table helps understand the contribution of each component (MLP connector, CLIP vision encoder, and the LLM itself) to the overall model’s performance.

This table compares the performance of CuMo against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs on several benchmark datasets. The models are grouped by their base LLM size (7B, 13B parameters, and 7B MoE models). The table highlights CuMo’s superior performance across multiple benchmarks within each size group, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed method. The ‘Act.’ column refers to activated parameters during inference, and the † symbol denotes results averaged over three GPT API queries.

This table compares the performance of CuMo against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs on various benchmarks. Models are categorized by their base LLM size (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE models). The table highlights CuMo’s superior performance across multiple benchmarks, often matching or exceeding the performance of larger models. The ‘Act.’ column shows the number of activated parameters during inference, and the † symbol indicates results averaged from three GPT API queries for greater accuracy.

This table compares the performance of CuMo against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs across various benchmarks. Models are grouped by base LLM size (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE). The best performance for each benchmark is highlighted in bold. The ‘Act.’ column indicates the number of activated parameters during inference, and numbers with a dagger (†) represent averages from three GPT API queries.

This table compares CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs on various benchmarks. Models are grouped by base LLM size (7B, 13B, and 7B with Mixture-of-Experts). The best performance for each benchmark is highlighted in bold. ‘Act.’ indicates the number of activated parameters during inference. Results marked with a dagger (†) represent averages from three GPT API queries.

This table compares CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs on various benchmarks. Models are categorized by base LLM size (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE models). The best performance for each benchmark is highlighted in bold. ‘Act.’ refers to the number of activated parameters during inference, and numbers marked with a dagger symbol (+) represent averages from three inference runs using the GPT API.

This table compares CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs on various benchmarks. Models are grouped by base LLM size (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE). The best performance for each benchmark is highlighted in bold. The table also shows the number of activated parameters during inference for each model. Note that some numbers are averages from three runs using the GPT API.

This table compares CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs across various benchmarks. Models are grouped by base LLM size (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE). The best performance for each benchmark is highlighted in bold. ‘Act.’ refers to activated parameters during inference, and numbers marked with a dagger symbol (+) represent averages from three GPT API queries.

This table compares CuMo’s performance against other state-of-the-art multimodal LLMs on various benchmarks. Models are grouped by the size of their base LLM (7B, 13B, and 7B MoE models). The best performance on each benchmark is highlighted in bold. The table also shows the number of activated parameters during inference and notes that some numbers are averages from three GPT API queries.

Full paper#