↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Humans learn through experimentation, actively testing hypotheses and revising their understanding of the world. Existing computational models of this process often rely on simplified representations of hypotheses and struggle to capture the nuanced way humans handle uncertainty and incorporate new information incrementally. This research tackles these limitations by proposing an alternative framework.

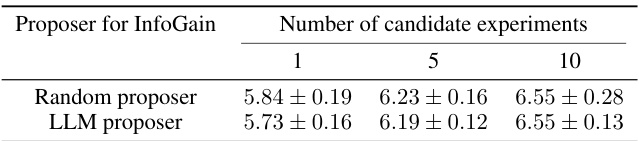

This new model, named ActiveACRE, uses Large Language Models (LLMs) to represent hypotheses as natural language strings. It then employs probabilistic inference to update belief about these hypotheses based on experimental results, using Monte Carlo methods. The study compares the model’s performance with human subjects and state-of-the-art algorithms in Zendo-style tasks, finding that ActiveACRE demonstrates higher accuracy in inferring the correct rules and more closely mirroring human behavior, especially when accounting for fuzzy and uncertain rules.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to model human learning through experimentation, integrating LLMs and probabilistic reasoning. This opens new avenues for research in active learning, cognitive modeling, and the use of LLMs for hypothesis generation and revision, especially in online settings. The findings challenge assumptions about human rationality and learning in the process, having implications for the design of AI systems that learn interactively and collaborate with humans.

Visual Insights#

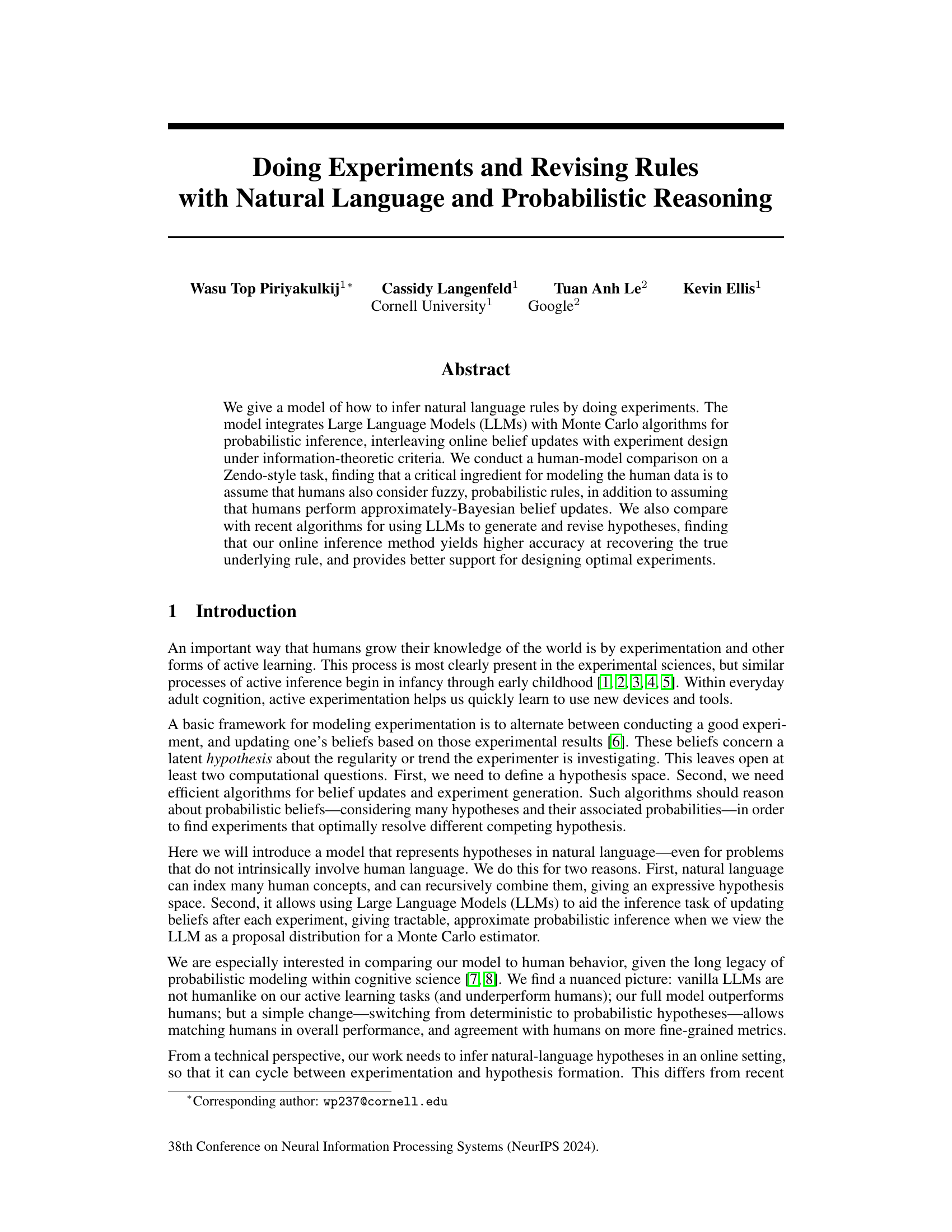

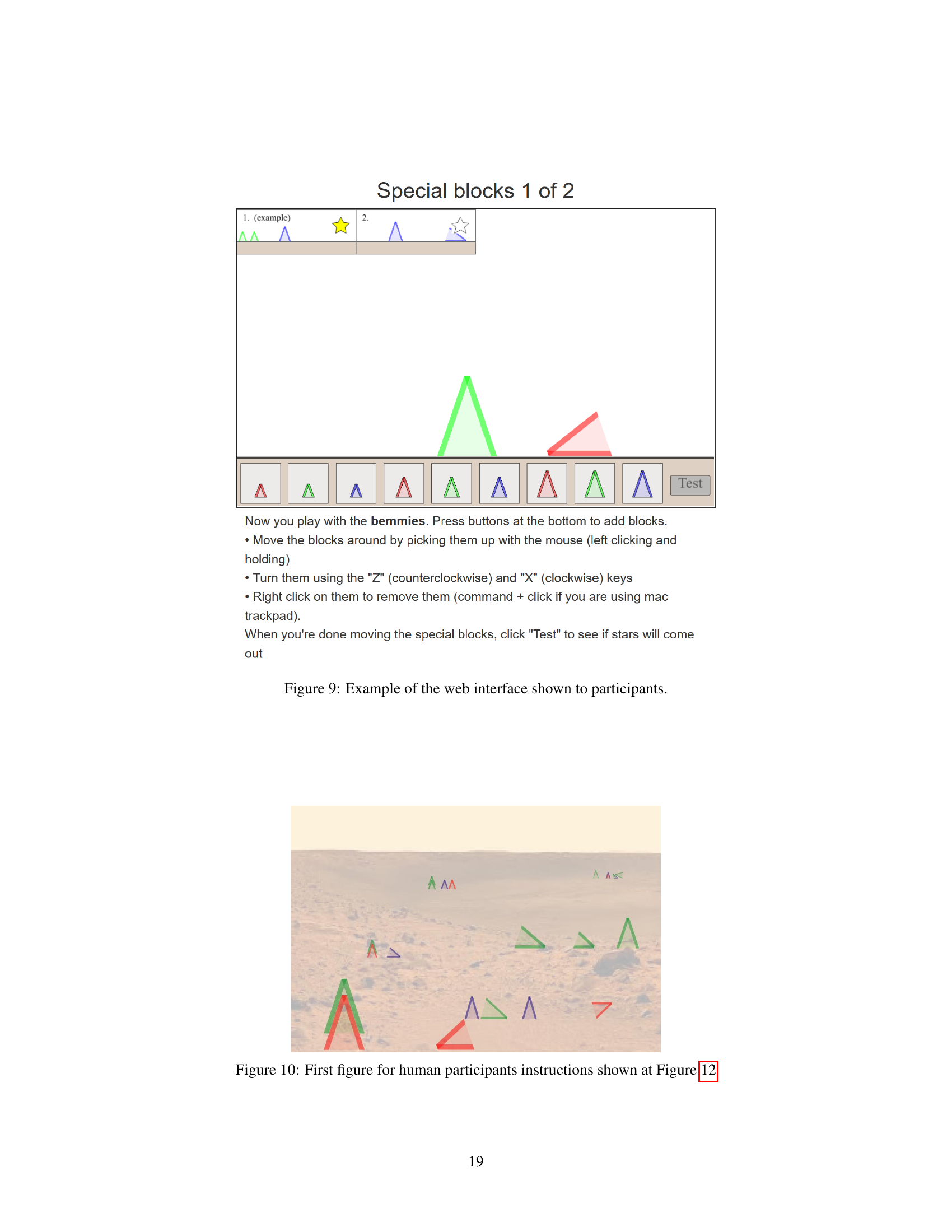

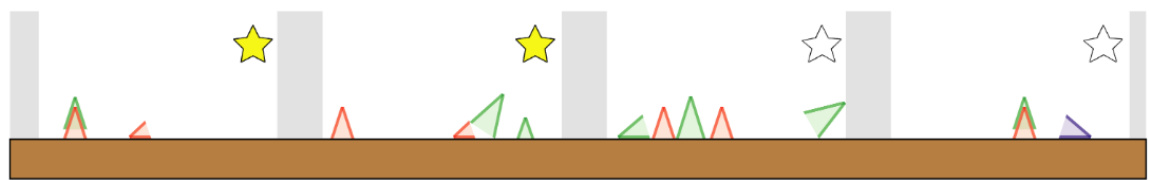

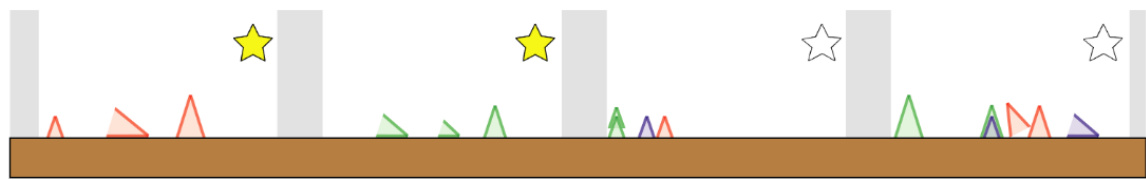

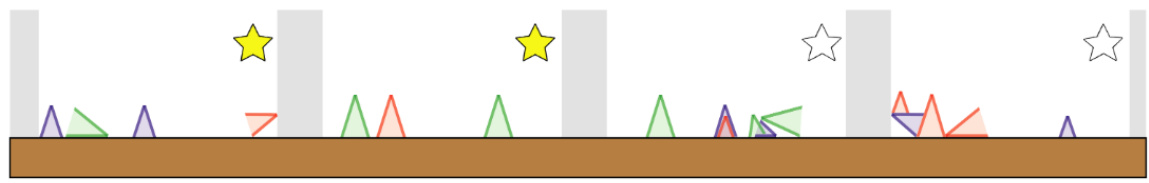

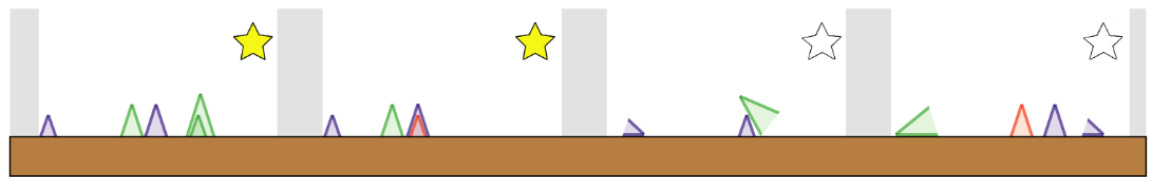

This figure illustrates the iterative process of experimentation and hypothesis revision in a simplified ActiveACRE (Abstract Causal Reasoning) domain. The left side shows a series of experiments where objects are placed on a machine, and the machine either makes a sound or does not. Based on the outcome of the experiments, hypotheses are revised, represented on the right side as natural language statements. The hypotheses refine over time, illustrating how the model learns the causal relationship between the objects placed on the machine and the machine’s sound production.

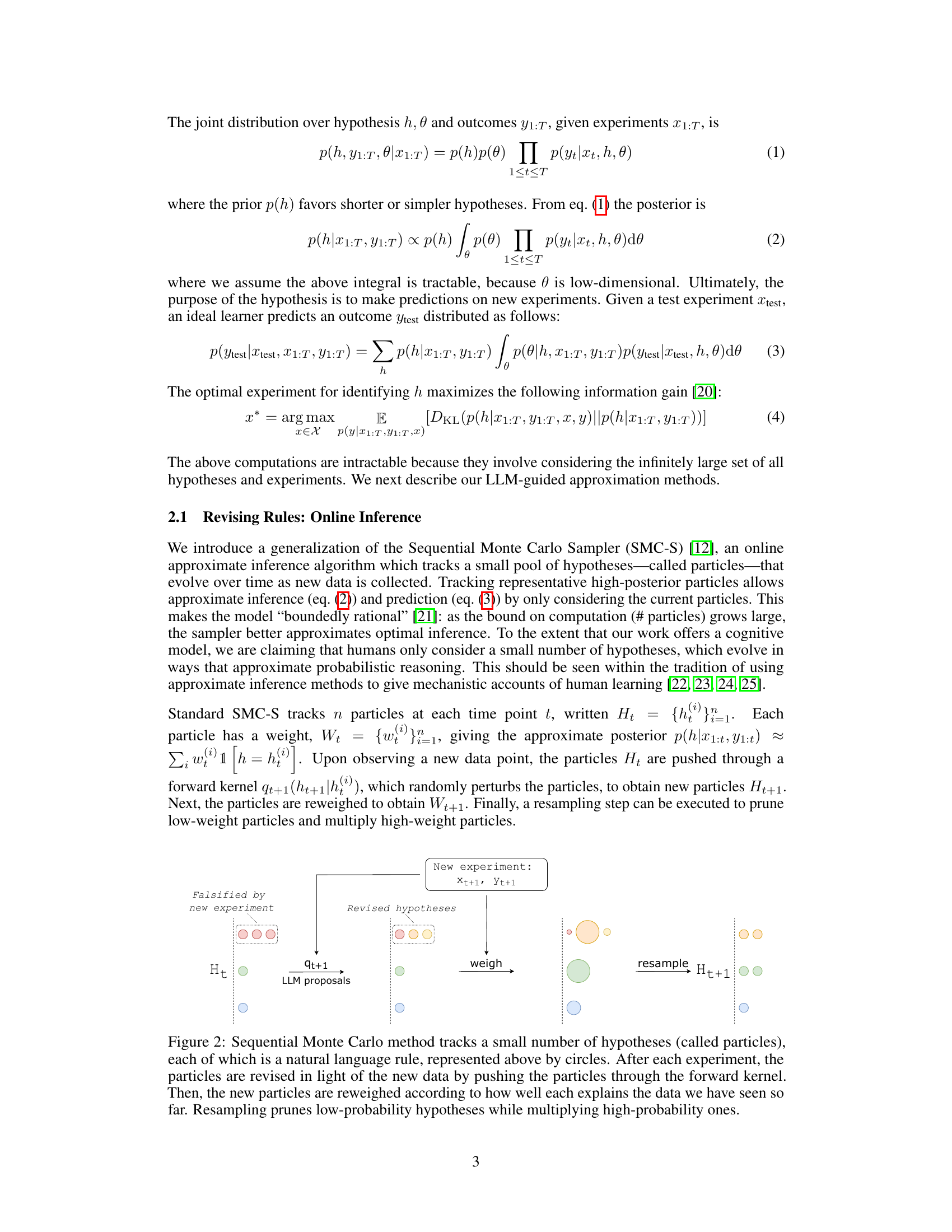

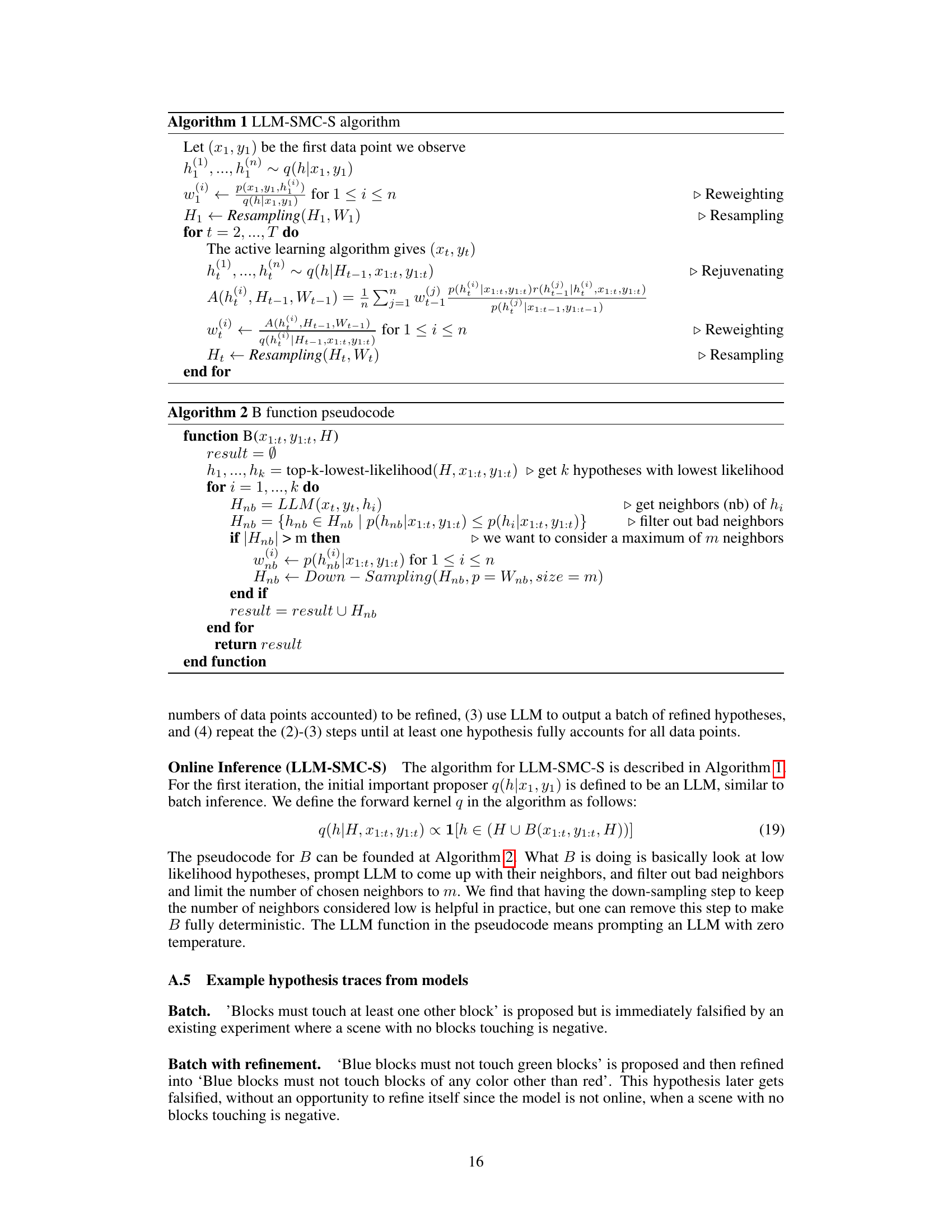

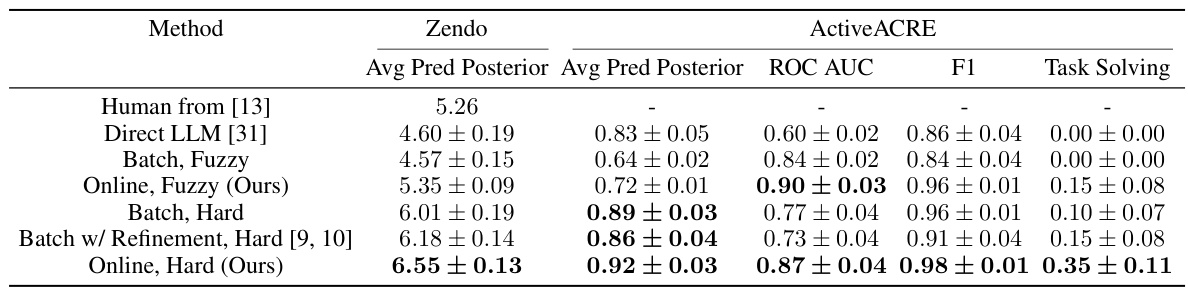

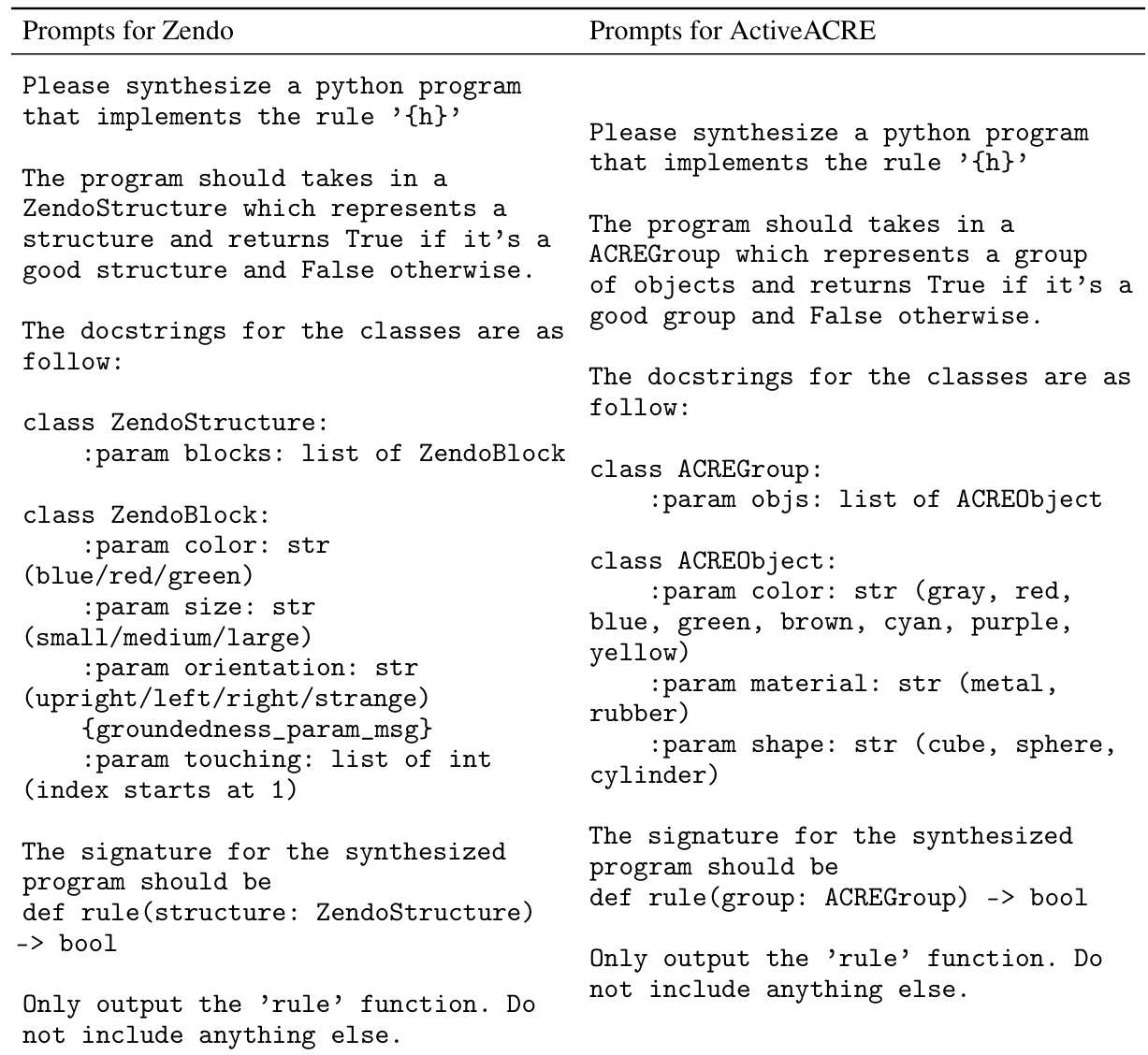

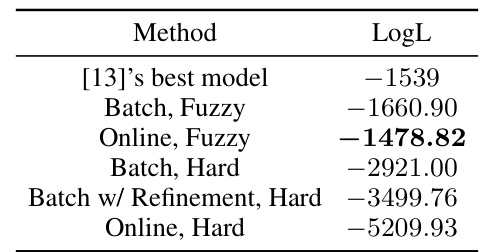

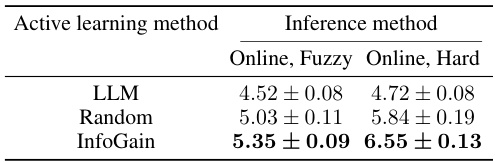

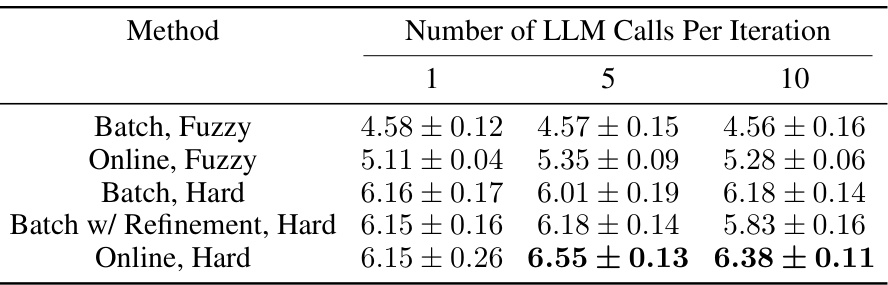

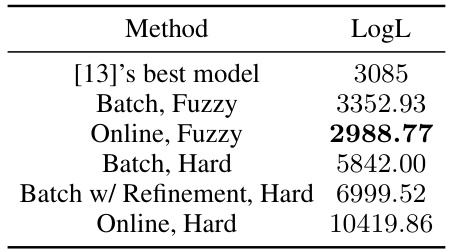

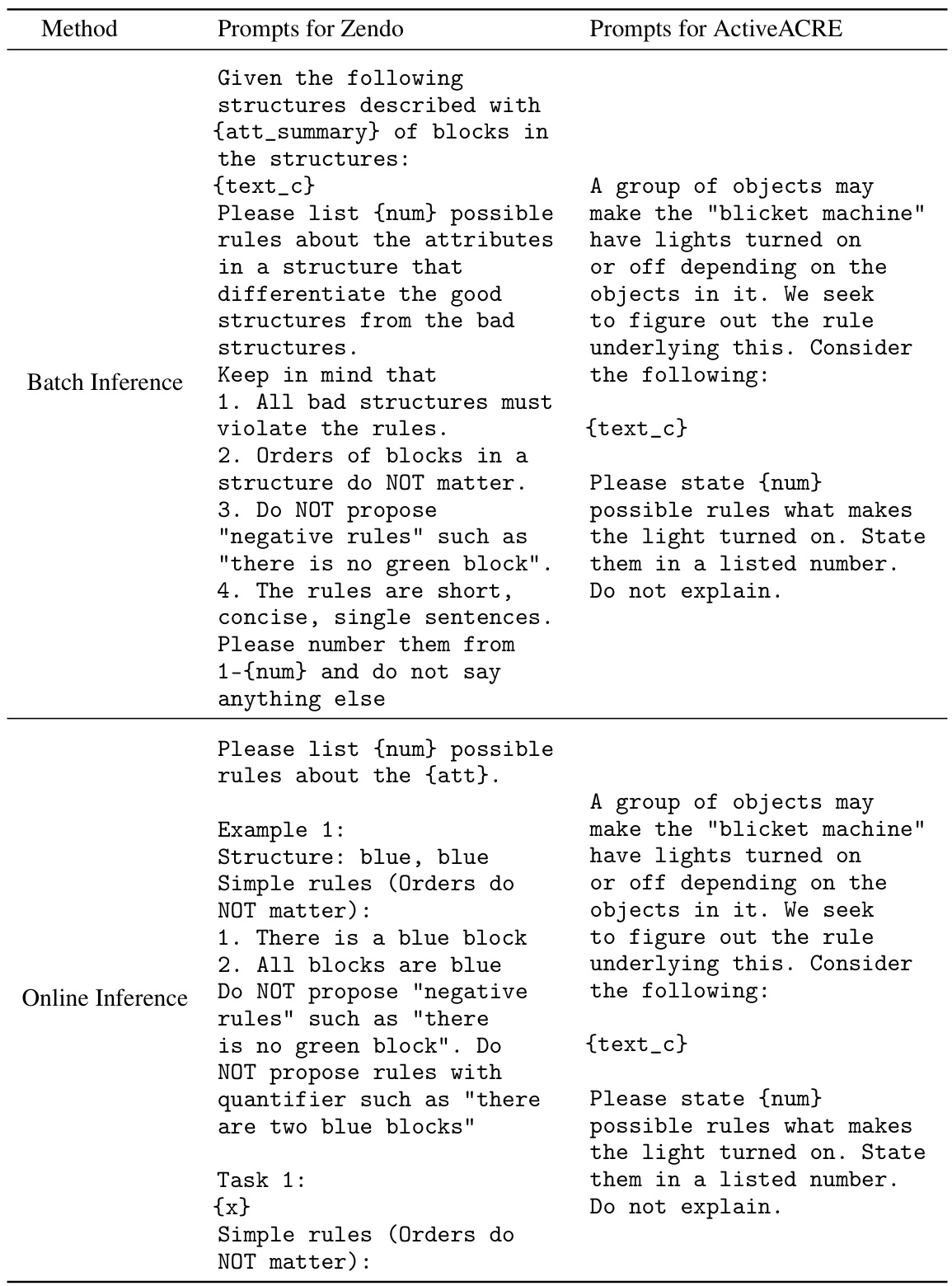

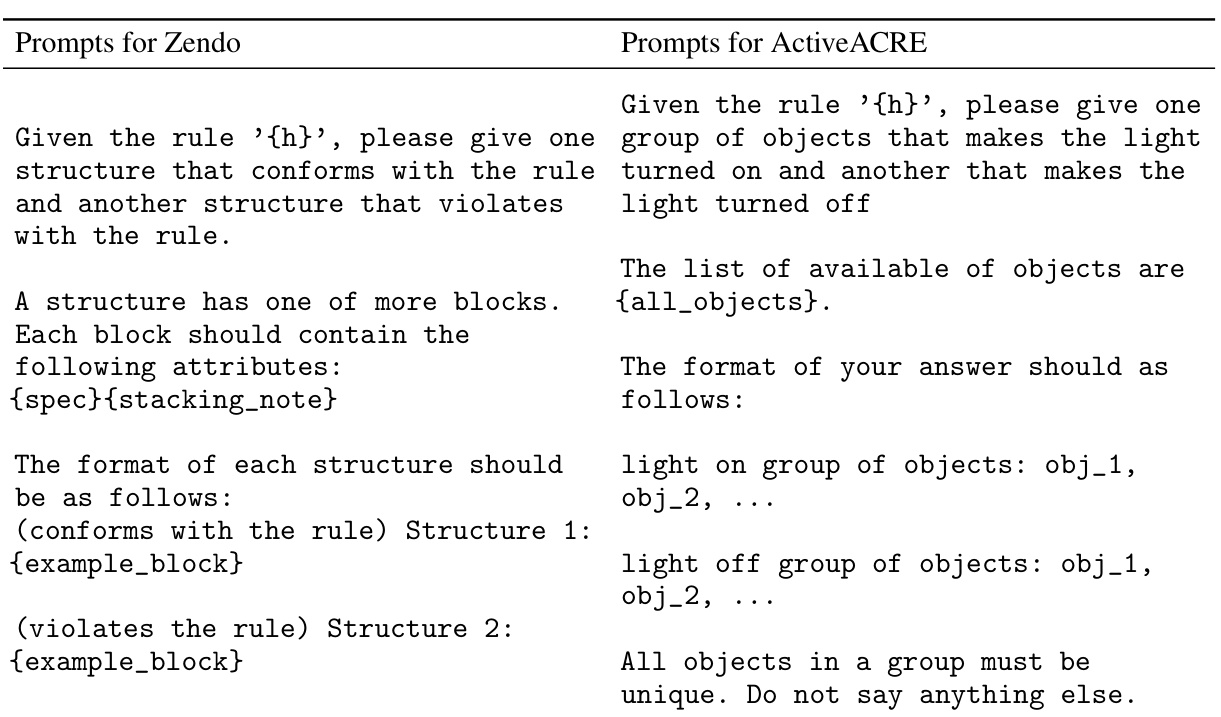

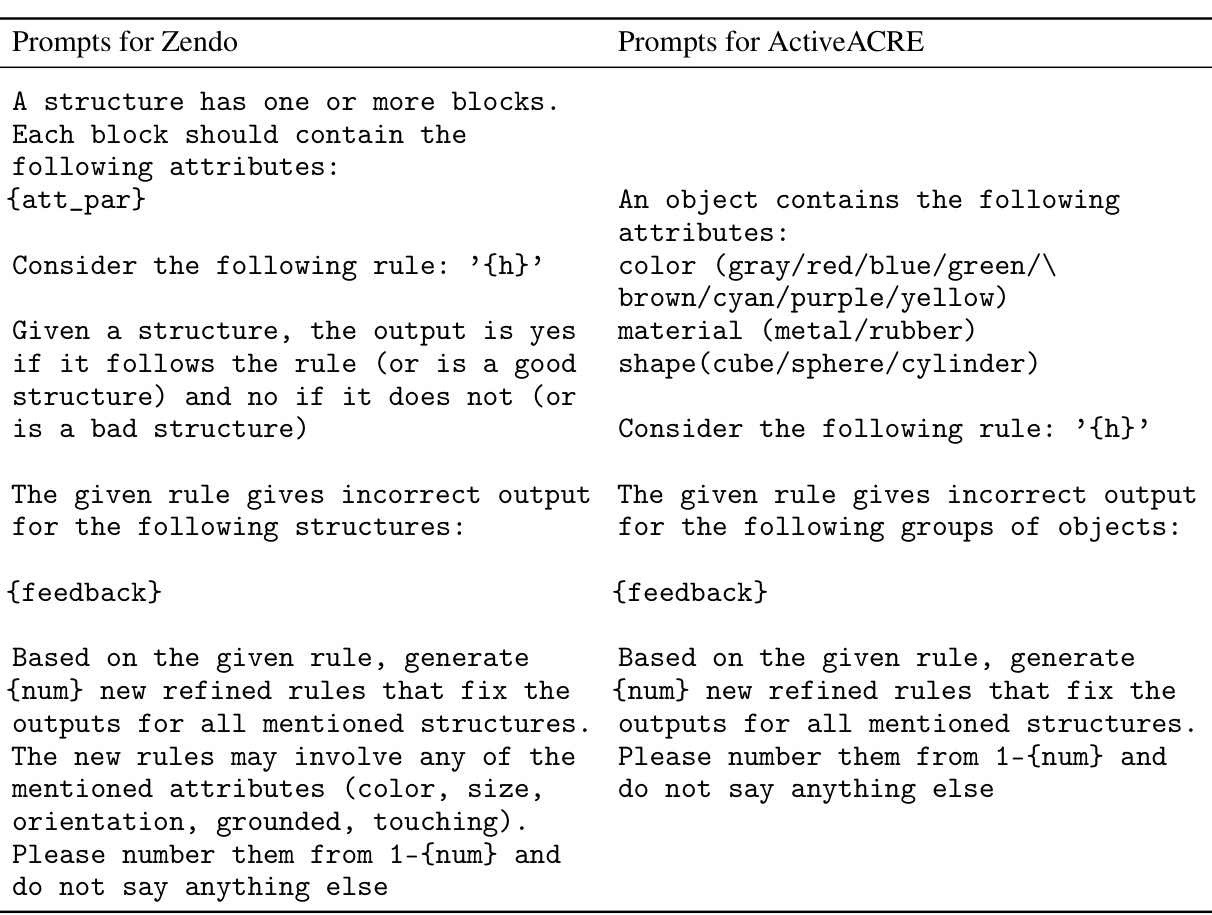

This table presents the results of two experiments, Zendo and ActiveACRE, comparing different methods for learning rules from data. It shows predictive posterior accuracy (averaged over multiple trials), along with other metrics like F1 score and ROC AUC, to evaluate the performance. Note that ActiveACRE is class-imbalanced; hence, additional metrics are used for a thorough evaluation. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of online learning methods, and comparing different models (including human performance) illustrates the nuanced picture of which methods best fit human behavior.

In-depth insights#

LLM-driven Inference#

LLM-driven inference represents a paradigm shift in probabilistic reasoning by leveraging the power of large language models. Instead of relying solely on traditional algorithms, this approach integrates LLMs to generate, refine, and evaluate hypotheses, often expressed in natural language. This offers several key advantages: enhanced expressiveness in representing complex hypotheses, improved tractability in handling high-dimensional spaces, and facilitated active learning through LLM-based experiment design. However, challenges remain. Accuracy relies heavily on the LLM’s underlying capabilities and biases, potentially introducing inaccuracies or inconsistencies into the inference process. Computational cost can also be a significant factor, particularly when dealing with complex hypotheses or extensive datasets. Therefore, effective LLM-driven inference requires careful consideration of prompt engineering, bias mitigation techniques, and efficient computational strategies to ensure reliable and robust results. The future of this field likely involves further research into these challenges to fully harness the potential of LLMs for probabilistic inference.

Online Experiment Design#

Online experiment design, in the context of a research paper, would likely explore how to iteratively design experiments and update beliefs in real-time, as data becomes available. This contrasts with traditional offline methods where all experiments are designed upfront. Active learning is a crucial aspect, aiming to select the most informative experiments based on current knowledge. The paper probably discusses algorithms for balancing exploration (trying new experiments) and exploitation (repeating successful experiments). Bayesian methods, with their ability to incorporate prior knowledge and update beliefs probabilistically, would likely be central to the approach. The paper might detail how to represent hypotheses effectively, perhaps using natural language or formal logic. Computational efficiency is another important consideration for online design, since decisions need to be made quickly. It likely evaluates such methods through simulations, comparing them with offline techniques or against human performance on learning tasks, focusing on metrics such as accuracy and efficiency.

Fuzzy Rule Modeling#

Fuzzy rule modeling offers a powerful approach to handle the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent in many real-world scenarios. Unlike traditional rule-based systems that rely on crisp, binary decisions, fuzzy rule models embrace vagueness and allow for gradual transitions between states. This is achieved through the use of fuzzy sets, which assign degrees of membership to elements, rather than absolute membership or non-membership. The core of a fuzzy rule model lies in its fuzzy rules, which typically take the form of “IF-THEN” statements connecting fuzzy sets in the antecedent and consequent parts. The inference mechanism within fuzzy rule models is based on fuzzy logic, allowing for smooth and nuanced transitions based on the degree of membership of input variables. This contrasts sharply with crisp systems where a small change in input might lead to a drastic change in output. The flexibility and adaptability of fuzzy rule models are their major strength, making them suitable for various applications such as control systems, decision making, pattern recognition and data analysis, where imprecise information is pervasive. However, a critical challenge in fuzzy rule modeling is the complexity involved in designing and tuning the fuzzy sets and rules. Often, this requires domain expertise and iterative refinement processes. Despite this, fuzzy rule modeling remains a valuable and active research area offering significant advantages over classical techniques. Interpretability is often a significant benefit of fuzzy rules, particularly in applications requiring human understanding and trust.

Human-Model Comparison#

A human-model comparison in a research paper is crucial for validating the model’s efficacy and understanding its limitations. It involves comparing the model’s performance on a specific task against human performance on the same task. Key aspects to consider include the metrics used for comparison (accuracy, response time, etc.), the sample size of both human participants and model runs, and the statistical significance of any observed differences. A thorough analysis should discuss factors influencing both human and model performance, exploring sources of error and identifying areas where the model mimics human behavior effectively and where it deviates. Careful consideration of cognitive processes and biases in human performance is necessary. Highlighting the model’s strengths and weaknesses relative to humans offers valuable insights into areas for future model improvement. The overall goal is to assess the model’s capabilities and determine its suitability for practical application by directly contrasting its behavior with human intuition and decision-making.

Active Learning Limits#

Active learning, while promising, faces inherent limits. Computational cost quickly escalates as the number of potential hypotheses and experiments grows, rendering exhaustive exploration infeasible. Data limitations restrict the types of questions that can be asked and knowledge that can be gained; incomplete, noisy, or biased data hinder effective learning. Model limitations also play a role; even sophisticated models may fail to correctly interpret data or to generalize to unseen situations. Additionally, human factors introduce complexity; humans may exhibit biases, struggle with expressing uncertainty, or prioritize questions based on factors beyond pure information gain. The optimal balance between exploration and exploitation, crucial for active learning, remains a significant challenge, requiring careful consideration of these limitations to achieve practical and efficient learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

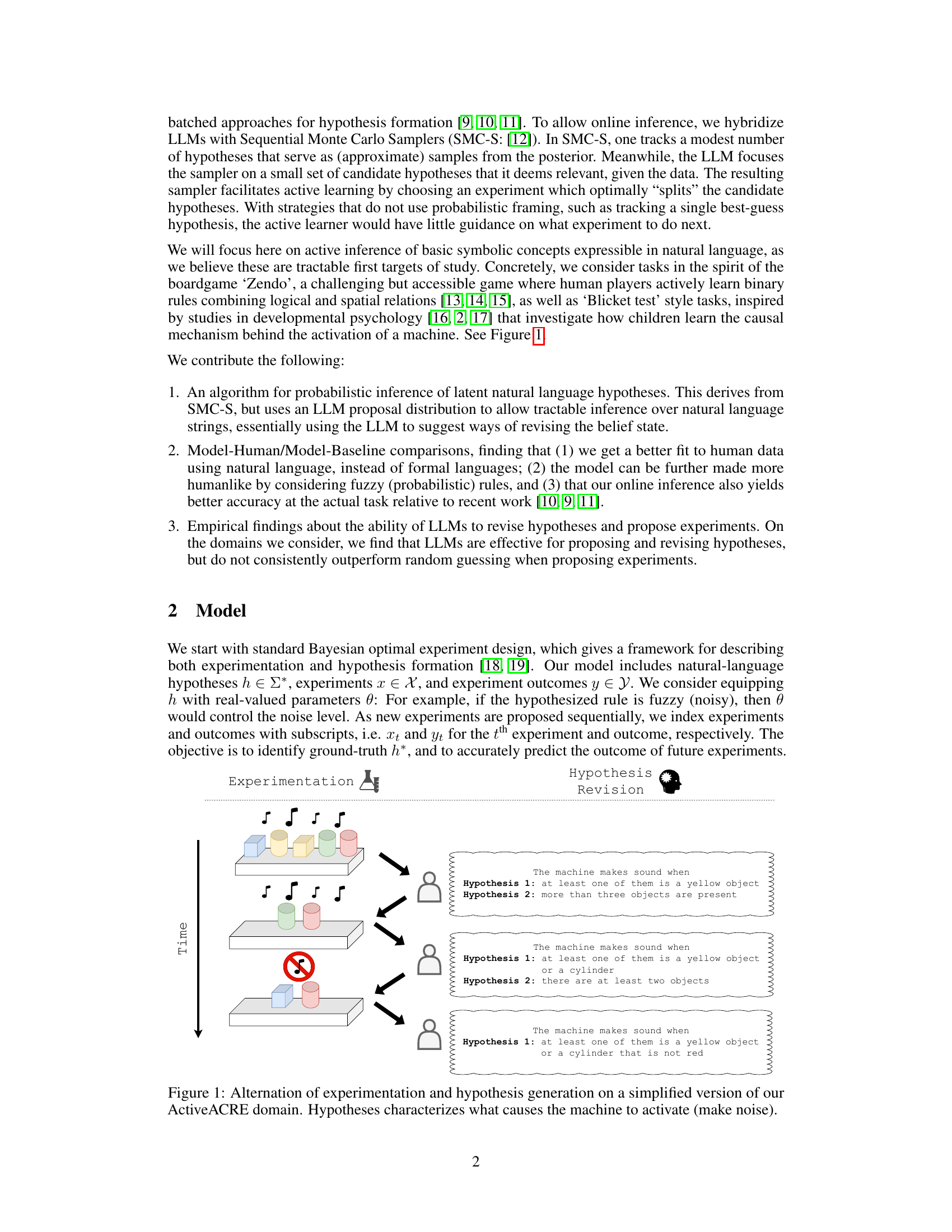

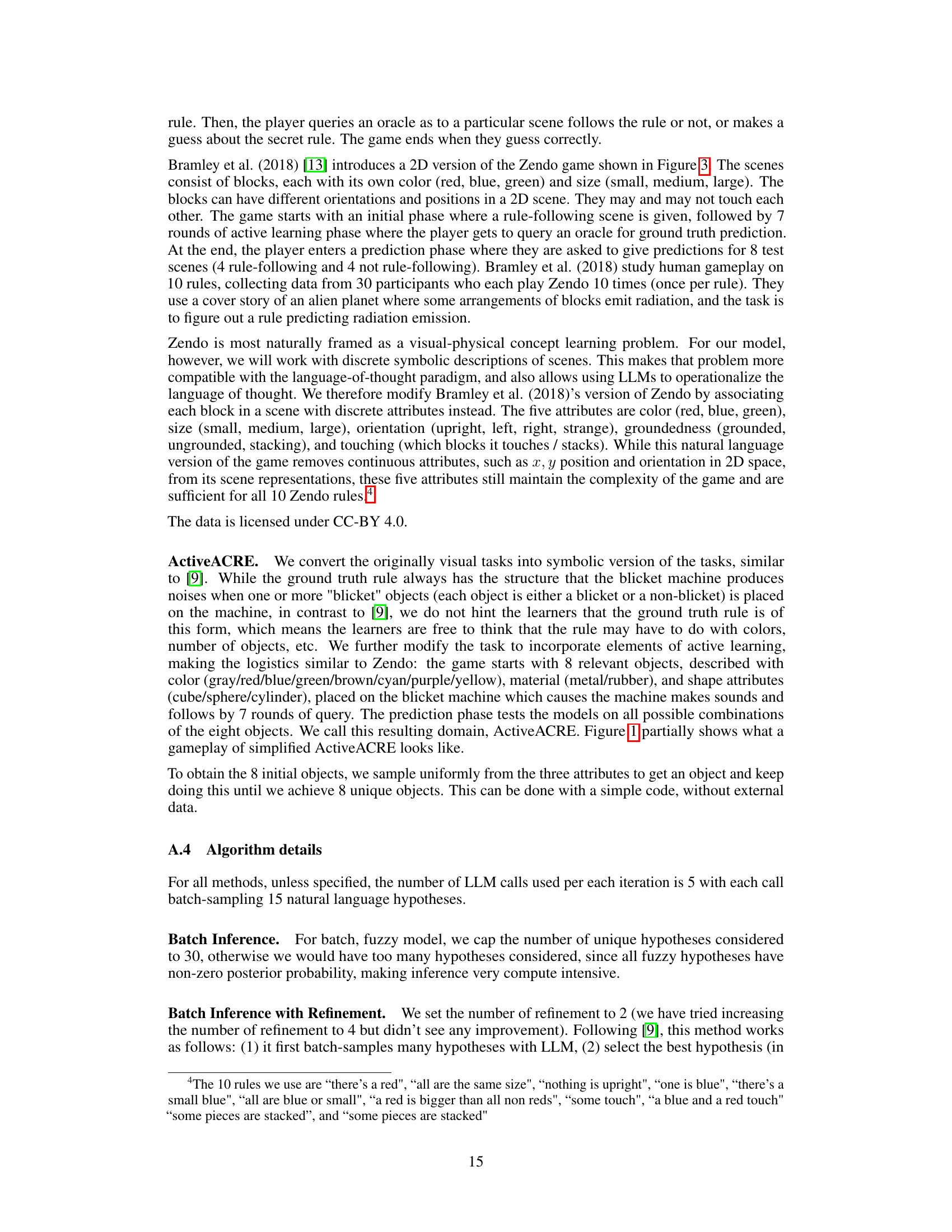

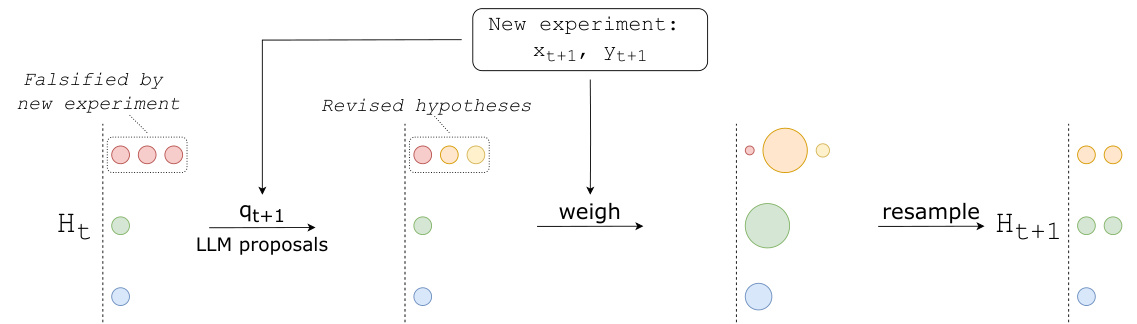

This figure illustrates the core process of the Sequential Monte Carlo Sampler (SMC-S) algorithm used in the paper. It tracks a limited number of hypotheses (represented as circles) which evolve over time based on new experimental data. The process is divided into three main steps: (1) proposing new hypotheses from previous ones using LLMs, (2) weighing the hypotheses based on their likelihood, and (3) resampling based on weights. This helps focus computation on the promising hypotheses and prune the low-probability ones.

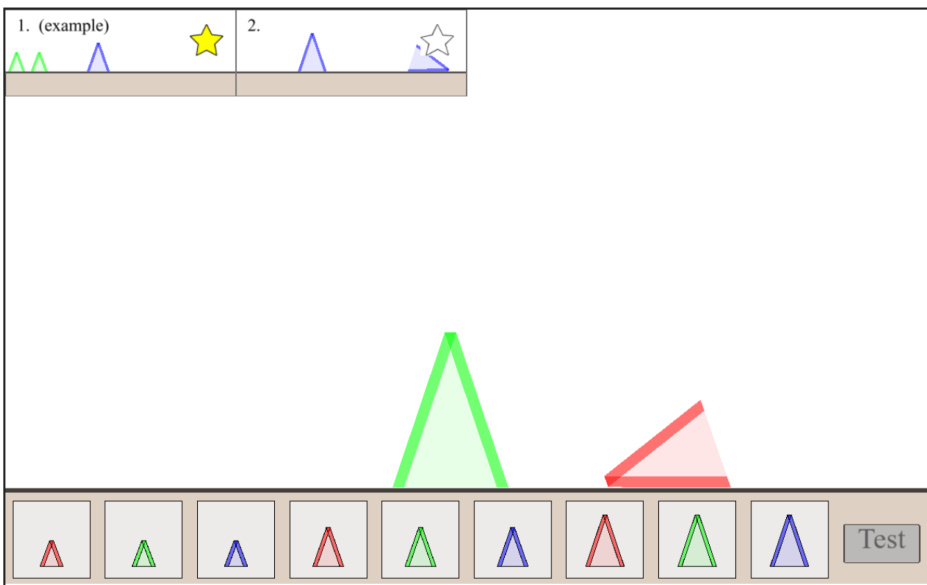

This figure shows an example of a Zendo scene and how it is represented in text format. Eight experiments are presented, where the player creates a scene and receives feedback on whether it follows a hidden rule or not. Finally, it depicts test scenes used to assess if the model or human correctly identified the hidden rule.

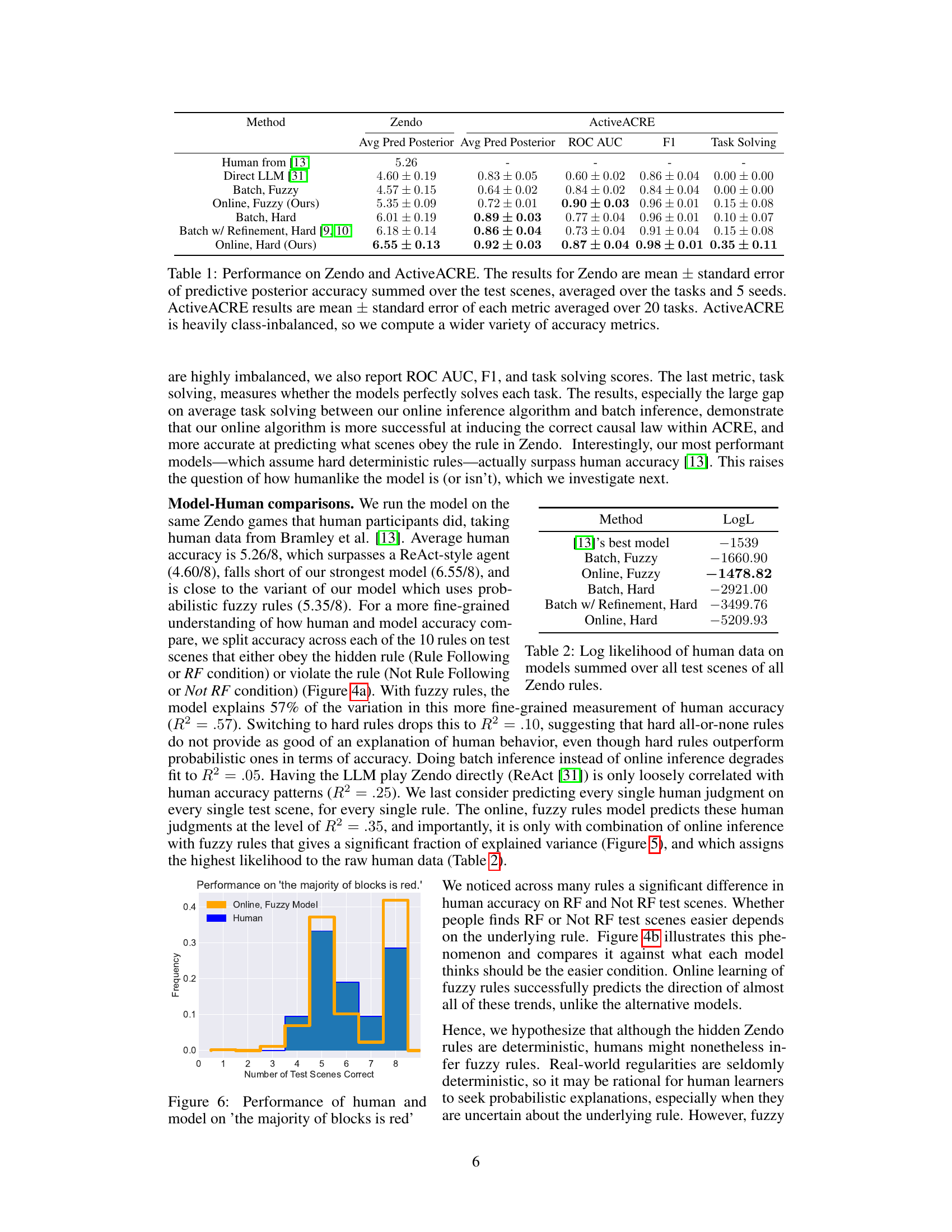

This figure shows a comparison of the performance of human participants and the online fuzzy model on a specific Zendo rule: ’the majority of blocks is red.’ The x-axis represents the number of test scenes correctly predicted, and the y-axis represents the frequency of that outcome. The bars show that the model’s predictions align well with the human data, demonstrating the model’s ability to capture the nuances of human reasoning in this Zendo variant. This specific rule was chosen because it is not expressible in the formal language developed for Zendo in prior work, highlighting the model’s flexibility in handling natural language.

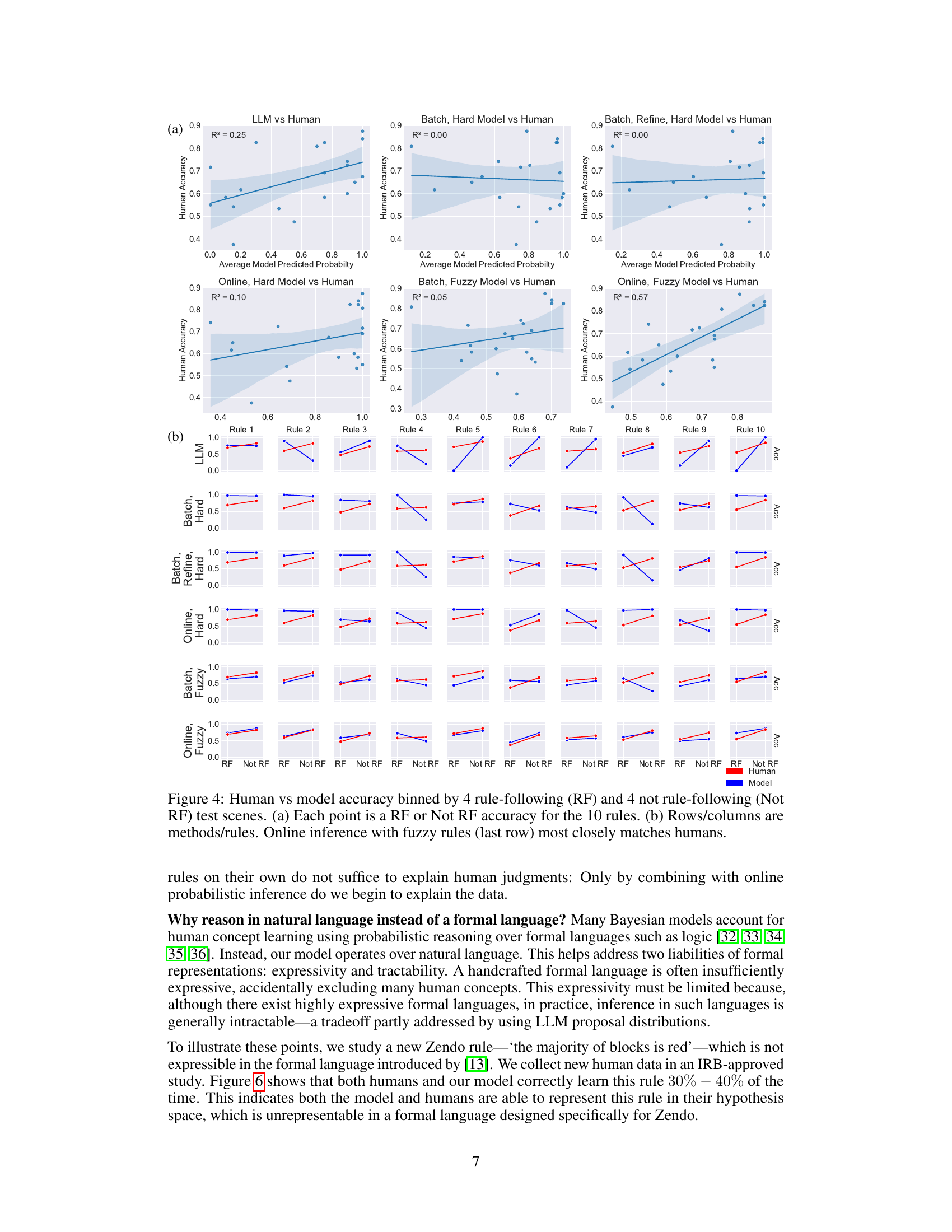

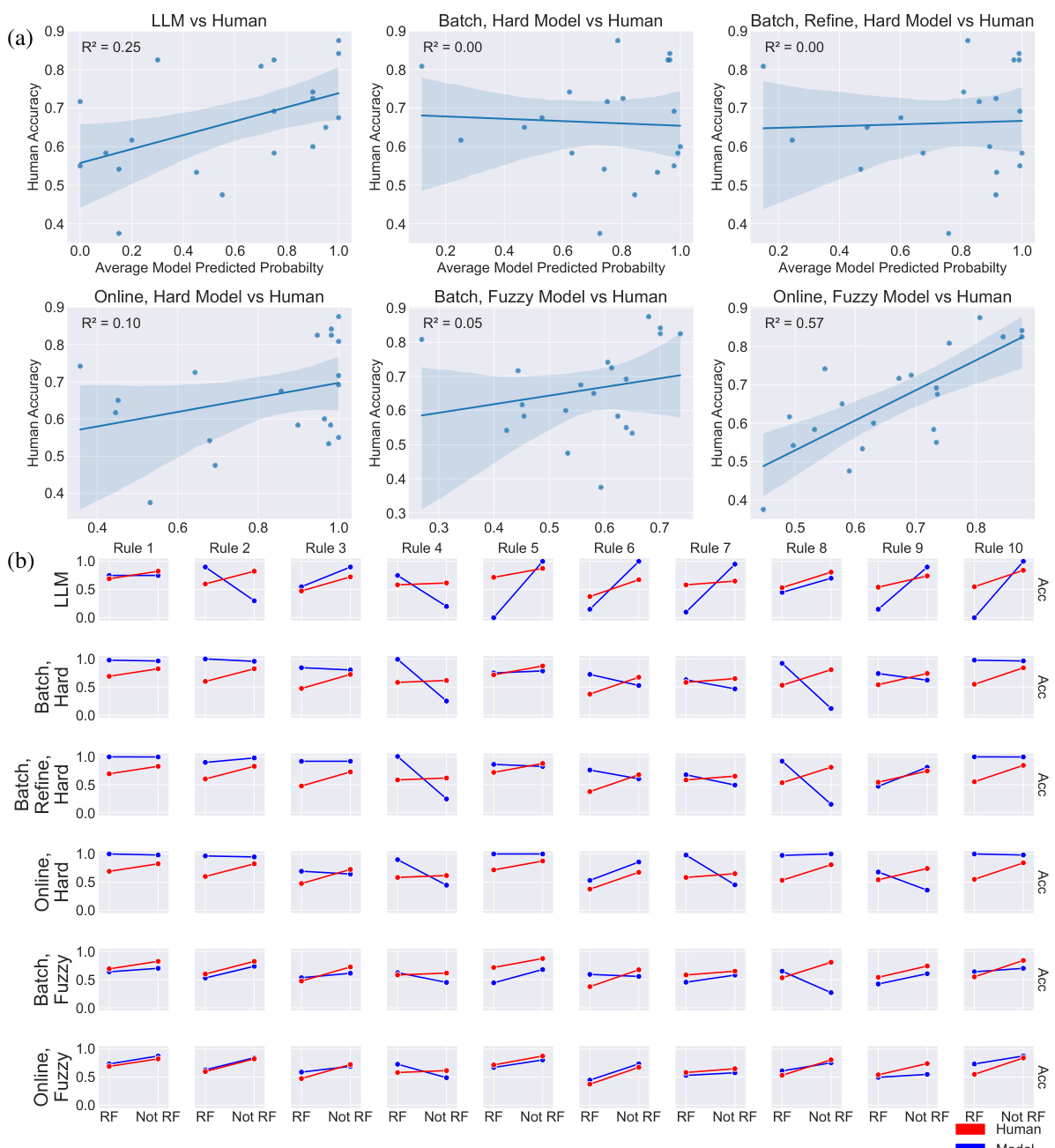

This figure compares the performance of different models against human performance on Zendo. Panel (a) shows the accuracy of each model for rule-following and rule-violating test scenes. Panel (b) provides a more detailed comparison across different models and rules. The results suggest that the model using online inference with fuzzy rules best matches human performance.

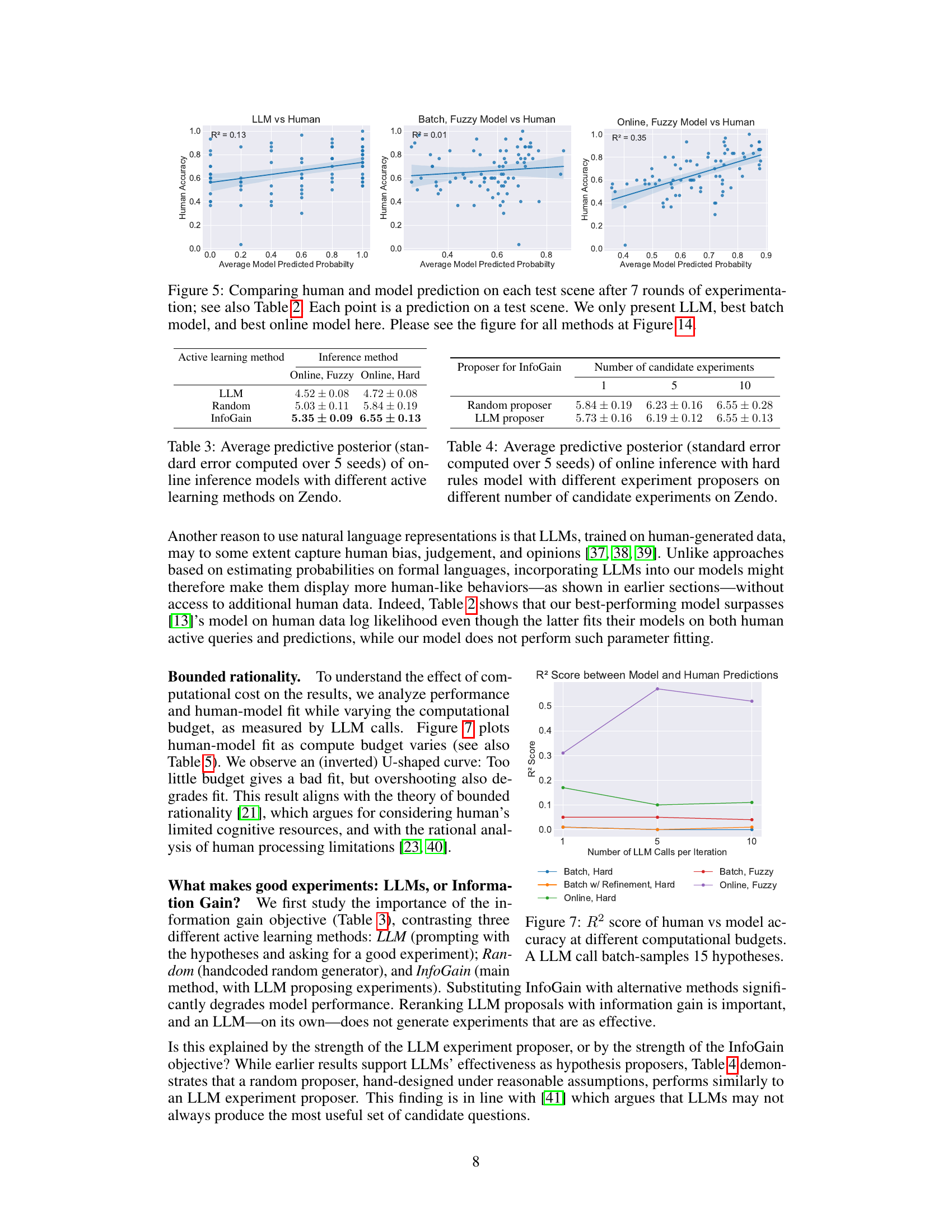

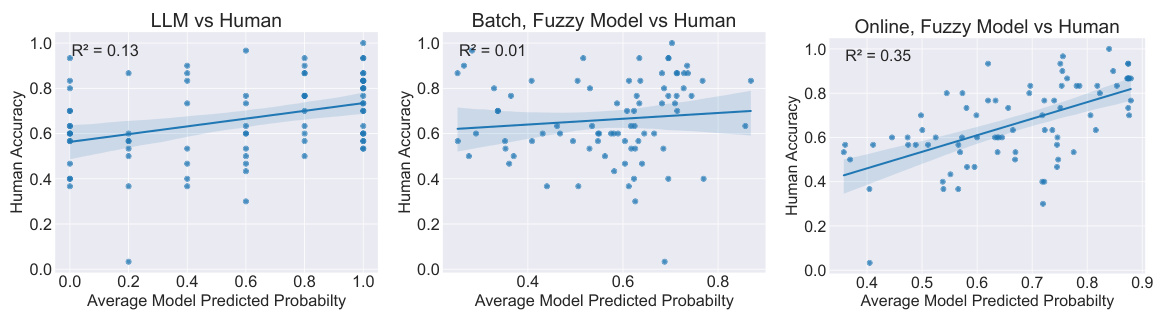

This figure compares human accuracy with model predictions on each test scene after 7 rounds of experimentation in the Zendo game. It shows the relationship between average model-predicted probabilities and human accuracy for three different models: LLM (direct LLM), the best performing batch model, and the best performing online model. The R-squared values indicate the goodness of fit for each model’s predictions against the human data. The full comparison including other model types is presented in Figure 14.

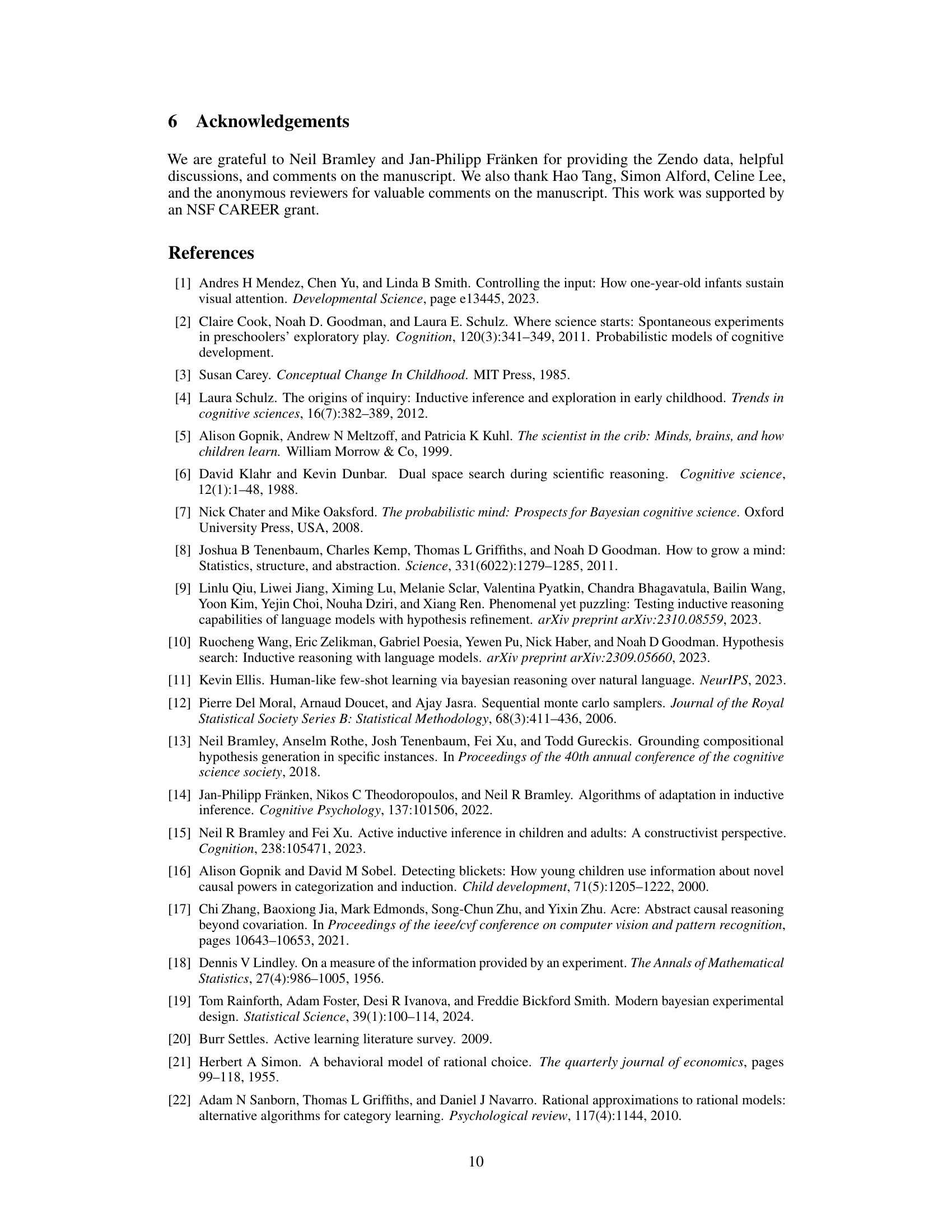

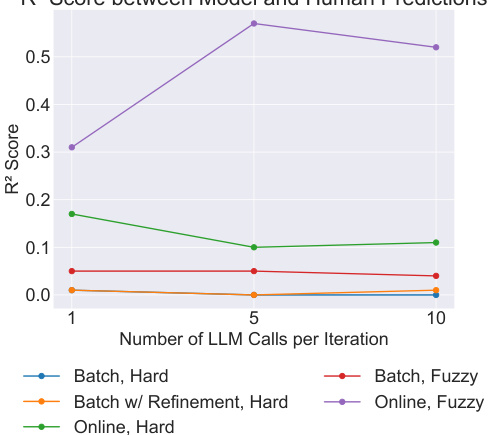

This figure shows the relationship between the R-squared score (a measure of model fit to human data) and the number of LLM calls per iteration in different active learning models. It demonstrates a clear pattern of bounded rationality; model accuracy improves with increased LLM calls but eventually plateaus, implying diminishing returns on computational effort and highlighting the importance of balancing computational resources with model accuracy.

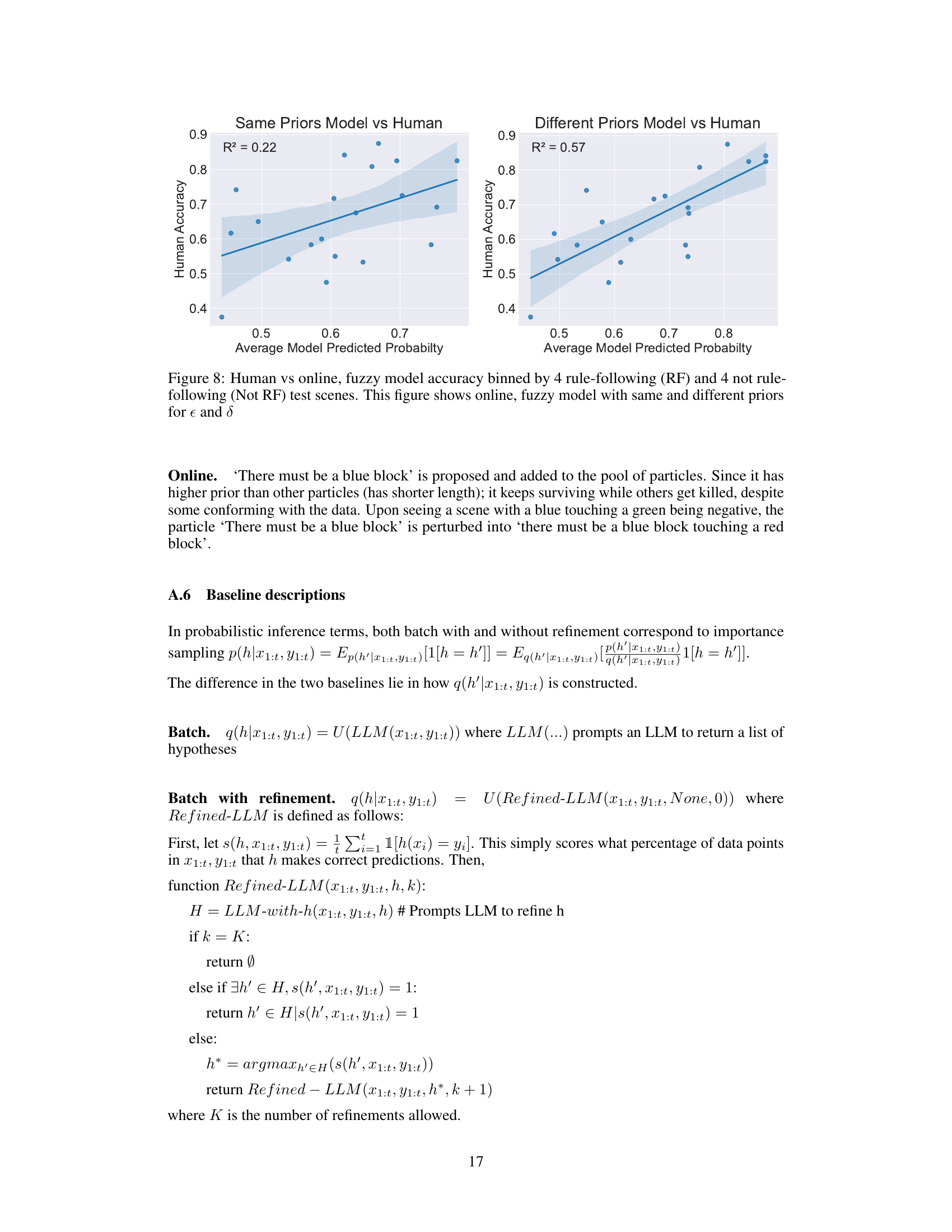

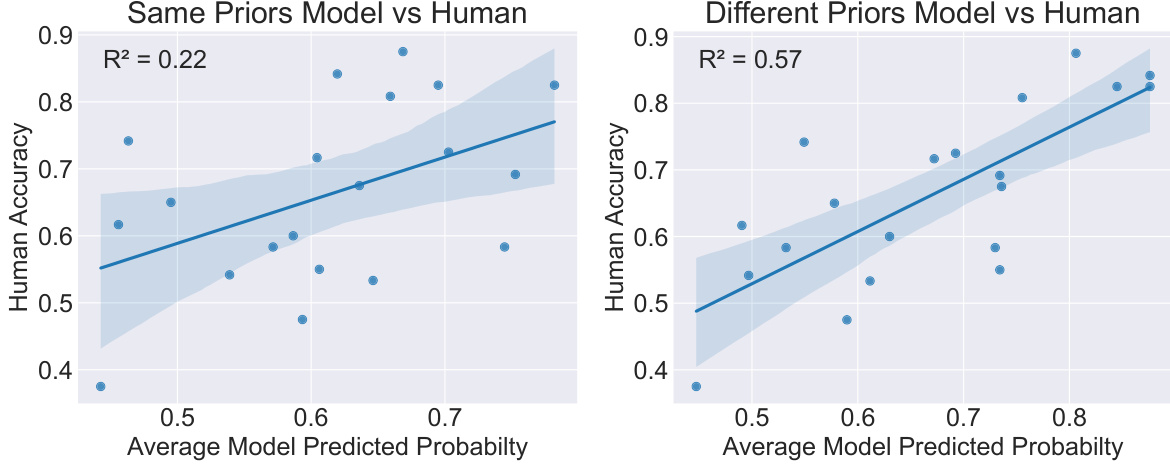

This figure shows the correlation between human accuracy and model predicted probability in Zendo. The model is an online fuzzy model. Two versions of the model are used, one with same priors and another with different priors. The R-squared value for the model with different priors (0.57) is significantly higher than the model with same priors (0.22), indicating that the model with different priors explains more of the variation in human accuracy. This suggests that using different priors may lead to a more human-like model.

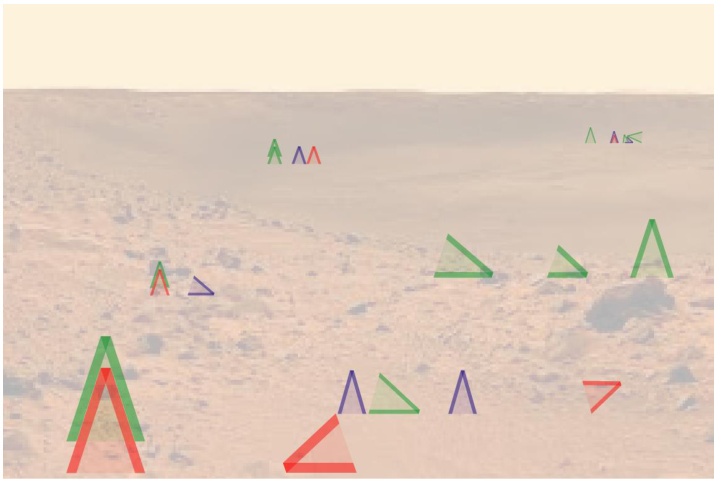

This figure illustrates the process of active learning in the ActiveACRE domain, a simplified version of the Abstract Causal Reasoning (ACRE) dataset. The process alternates between experimentation (trying different combinations of objects on a machine) and hypothesis revision (adjusting the explanation of what causes the machine to make a sound). The figure shows examples of hypotheses written in natural language evolving based on the outcomes of experiments, demonstrating the iterative nature of the learning process.

This figure illustrates a simplified version of the ActiveACRE domain used in the paper’s experiments. It shows the iterative process of experimentation and hypothesis revision. The experimenter starts with initial hypotheses and designs experiments to test those hypotheses. Based on the results of the experiments, the hypotheses are revised. This process is repeated until the true underlying rule is identified. The figure visually depicts this cycle with a simplified representation of the experimental setup and the hypothesis revision process. The machine activates (makes noise) based on a set of rules that are gradually learned through experimentation.

This figure shows a simplified version of the ActiveACRE domain used in the paper. It illustrates the iterative process of experimentation and hypothesis revision. The process starts with an initial hypothesis about what causes the machine to make noise. Based on the outcome of experiments, hypotheses are revised, leading to the creation of new experiments to further refine the hypotheses. The figure highlights the cyclical nature of this active learning process where experimentation informs belief updates, which in turn guide the design of new experiments.

This figure illustrates the Zendo game, showing how scenes are represented in text (a), examples of experiments with binary outcomes (b), and test scenes used to evaluate whether a model or human has learned the hidden rule (c).

This figure shows a simplified version of the ActiveACRE domain, illustrating the iterative process of experimentation and hypothesis revision. The top row depicts a series of experiments, where each experiment consists of arranging objects on a machine. The machine’s response (whether it makes a noise or not) is indicated below each experiment. The middle and bottom rows show how hypotheses (explanations for why the machine makes noise) are generated and refined based on the experimental results. Each hypothesis is represented as a natural language statement describing the conditions that cause the machine to activate. The process is iterative, with each experiment leading to the refinement or replacement of existing hypotheses.

This figure illustrates the iterative process of experimentation and hypothesis revision in a simplified version of the ActiveACRE domain. Each step shows an experiment conducted (indicated by the image of objects on a machine), the outcome (whether or not a sound is made), and the subsequent revision of hypotheses, represented in natural language. This process reflects the model’s active learning approach, where experiments are designed to inform and refine beliefs about the underlying rules that govern the machine’s behavior.

This figure compares human accuracy with the model’s predictions for each test scene after 7 rounds of experimentation. It shows the model’s predicted probability versus human accuracy for each scene. It helps to visualize how well different models predict human judgments on a per-scene basis. The results highlight that the online model with fuzzy rules most accurately matches the human judgments.

This figure compares the accuracy of human participants and different model variants on Zendo rule-following and non-rule-following test scenes. Panel (a) shows individual data points, plotting human accuracy against model predicted probabilities for each of the 10 Zendo rules, separately for rule-following and non-rule-following scenes. Panel (b) provides a more concise comparison across all 10 rules and models showing that the online inference method with fuzzy rules best approximates human performance.

This figure demonstrates the Zendo game setup used in the paper’s experiments. Panel (a) shows an example Zendo scene and how it’s represented in text format. Panel (b) illustrates eight example experiments, each resulting in a binary outcome (success/failure). Finally, panel (c) presents test scenes designed to assess whether a model (or human) has successfully deduced the underlying hidden rule.

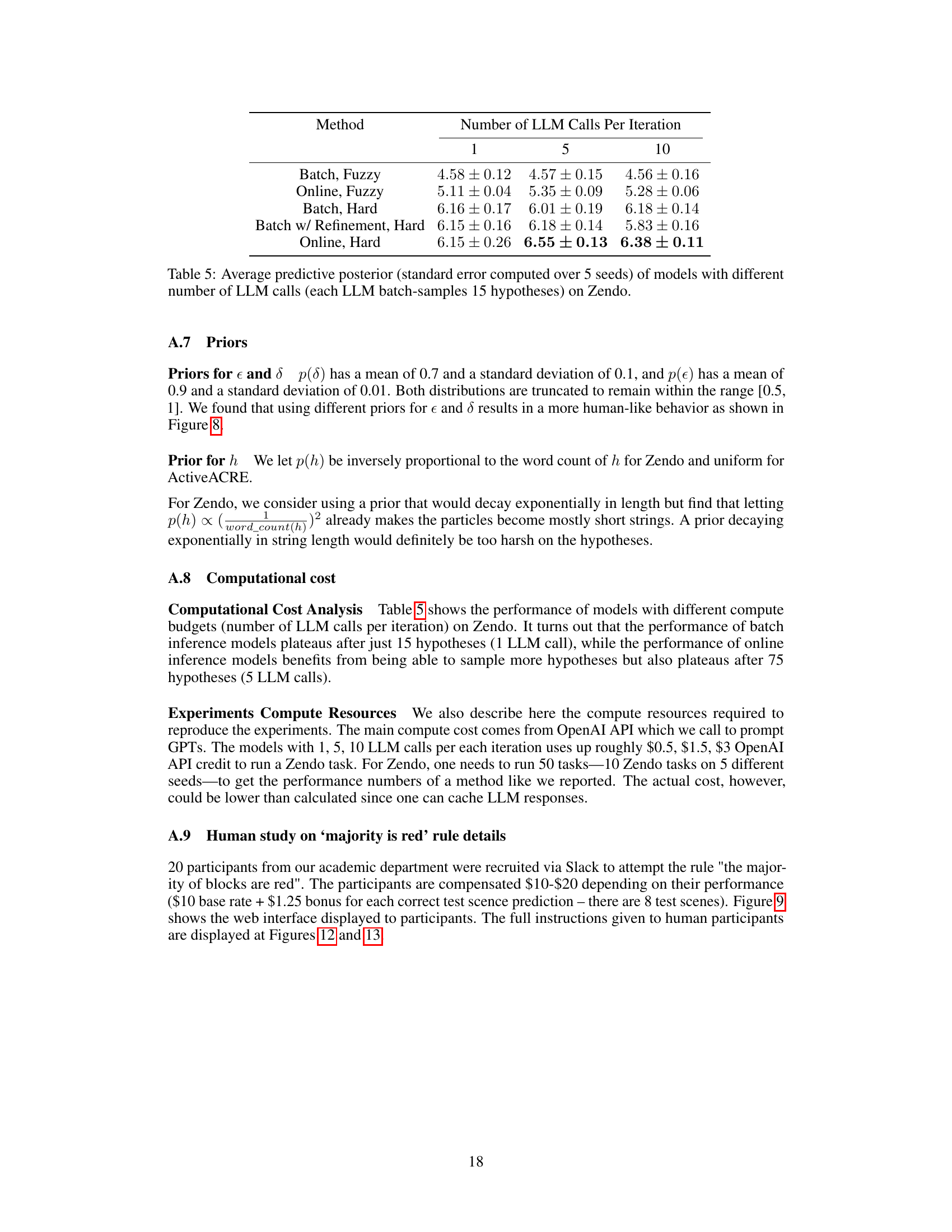

More on tables

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on two tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, the average predictive posterior accuracy is reported, averaged across multiple runs and tasks. For ActiveACRE, because of class imbalance, multiple metrics (ROC AUC, F1, task solving) are presented.

This table presents the performance of different models on two tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, it shows the average predictive posterior accuracy (with standard error) across multiple test scenes. For ActiveACRE, which has class imbalance, it presents more metrics (ROC AUC, F1, task solving) along with the average predictive posterior accuracy and standard error.

This table presents the results of the proposed model on two different tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. It compares the model’s performance against human performance and several baselines, assessing metrics such as predictive posterior accuracy, ROC AUC, F1 score, and task solving success rate. The results reveal that the online inference model, particularly when using fuzzy rules, outperforms other models, including humans in overall performance on Zendo, and achieves higher accuracy in solving the ActiveACRE tasks.

This table presents the performance of different methods on two tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, the average predictive posterior accuracy is shown, considering the mean and standard error across multiple trials. ActiveACRE results are presented with several metrics (ROC AUC, F1, Task Solving) because of the class imbalance in the data. The table allows comparison of the performance of human players, several baselines from previous work, and the authors’ proposed methods with different rule configurations (hard vs. fuzzy, online vs. batch).

This table presents the performance of different methods on two tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, the results show average predictive posterior accuracy, with standard errors. For ActiveACRE, which is class imbalanced, ROC AUC, F1 score, and task solving are reported as well, showcasing a comparison of multiple models across different metrics.

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on two tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, it shows the average predictive posterior accuracy, calculated as the mean across test scenes, tasks, and multiple runs. ActiveACRE results, due to class imbalance, include additional metrics beyond accuracy, like ROC AUC, F1 score, and task solving success rate. The table allows for comparison of human performance with the proposed model and existing baselines.

This table presents the results of the proposed model on two tasks, Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, it shows the average predictive posterior accuracy, calculated as the mean across multiple trials and averaged across different tasks. For ActiveACRE, which has an imbalanced class distribution, it presents a broader set of evaluation metrics (ROC AUC, F1-score, task solving success rate) to provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance. The standard error is provided to indicate the variability of the results.

This table presents the performance comparison of different models on two tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, it shows the average predictive posterior accuracy, while for ActiveACRE it provides a more comprehensive evaluation due to class imbalance, including ROC AUC, F1 score, and task solving rate. The results highlight the superior performance of the proposed online inference model, especially in ActiveACRE.

This table presents the performance comparison between different models on two tasks: Zendo and ActiveACRE. For Zendo, it shows the average predictive posterior accuracy, with standard error, across multiple test scenes and trials. ActiveACRE results are also averaged across multiple trials but include additional metrics (ROC AUC, F1 score, and Task Solving) due to class imbalance.

Full paper#