↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing methods for evaluating explanation robustness rely on lp distance, which may not align with human perception and can lead to an “arms race” between attackers and defenders. Moreover, adversarial training (AT) methods, commonly used to improve robustness, are computationally expensive. This paper addresses these limitations.

The paper proposes a novel metric, “ranking explanation thickness,” which better captures human perception of stability. It also introduces R2ET, a training method that uses an efficient regularizer to promote robust explanations. R2ET avoids the drawbacks of AT by directly optimizing the ranking stability of salient features and is theoretically shown to be robust against various attacks. Extensive experiments across different data modalities and model architectures confirm R2ET’s superior performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical issue of explanation robustness in machine learning, a crucial aspect for building trust and reliability in AI systems. By introducing a novel metric and training method, it offers a practical solution for enhancing the stability of explanations, which is highly relevant to current research trends in explainable AI and adversarial robustness. The findings open up avenues for future research, including the development of new explanation methods, improved attack models and defenses, and further explorations into the theoretical underpinnings of explanation stability.

Visual Insights#

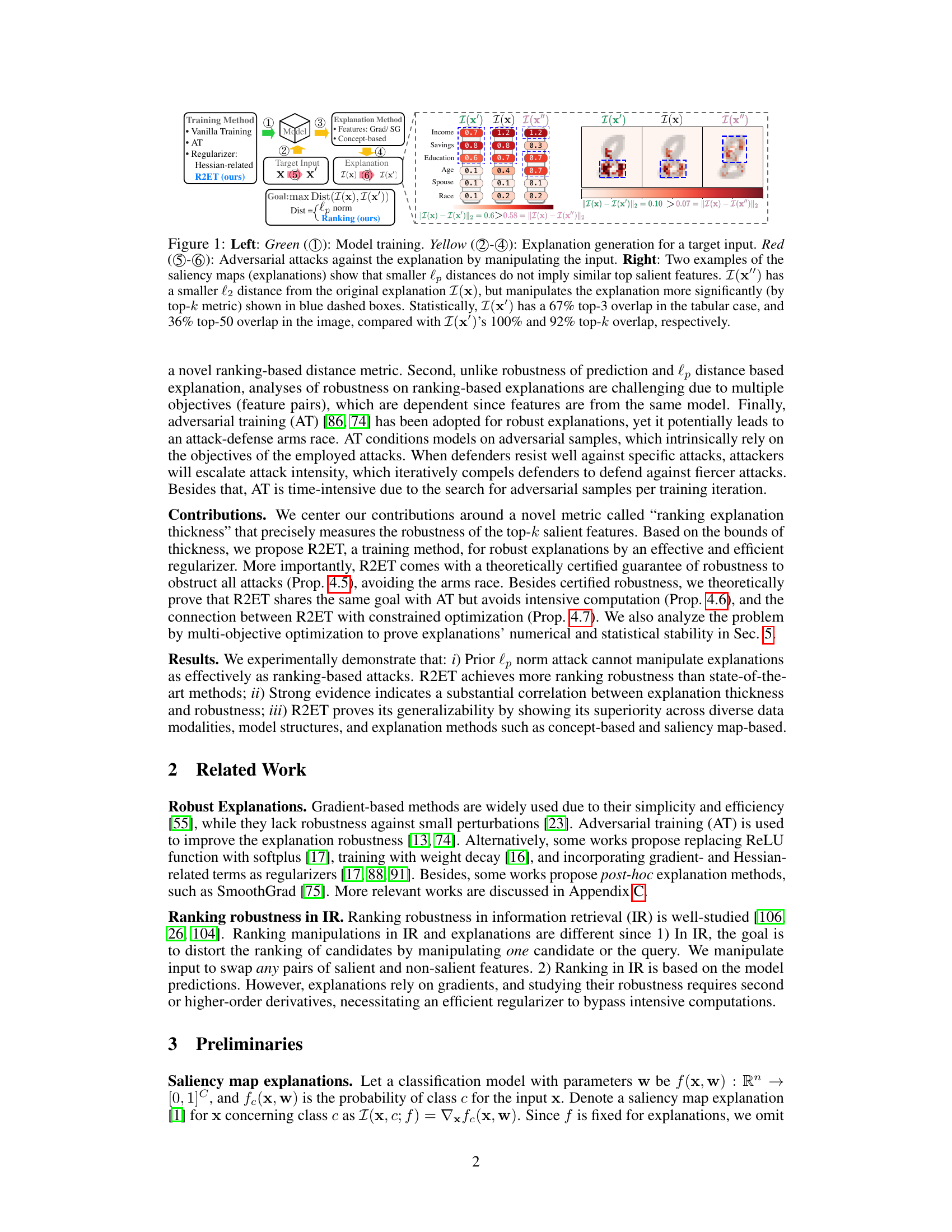

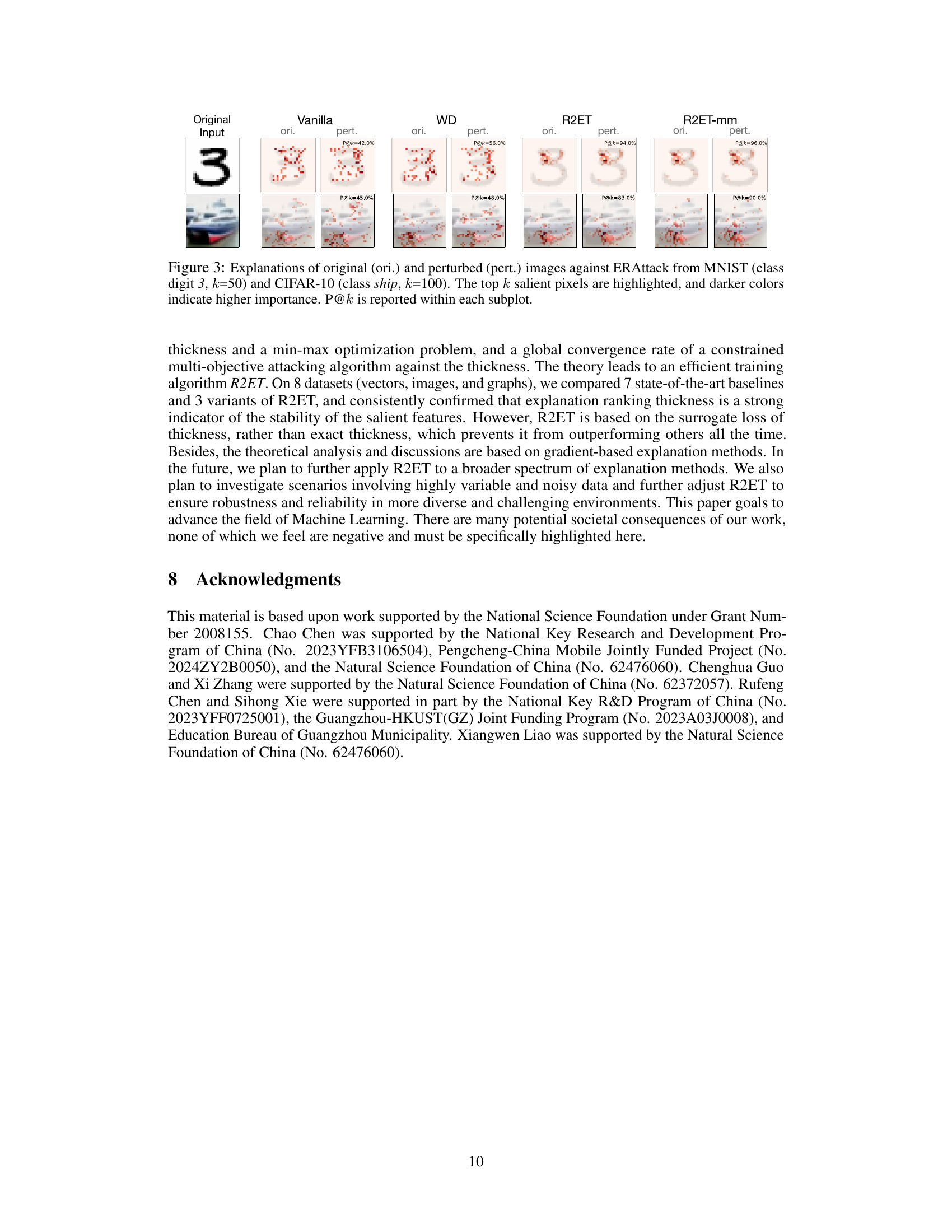

This figure illustrates the process of explanation generation and adversarial attacks. The left side shows a schematic of model training and explanation generation, while the right side presents two examples showing that smaller L_p distances between explanations do not guarantee similar top salient features. This highlights the limitations of using L_p distance as a metric for explanation stability.

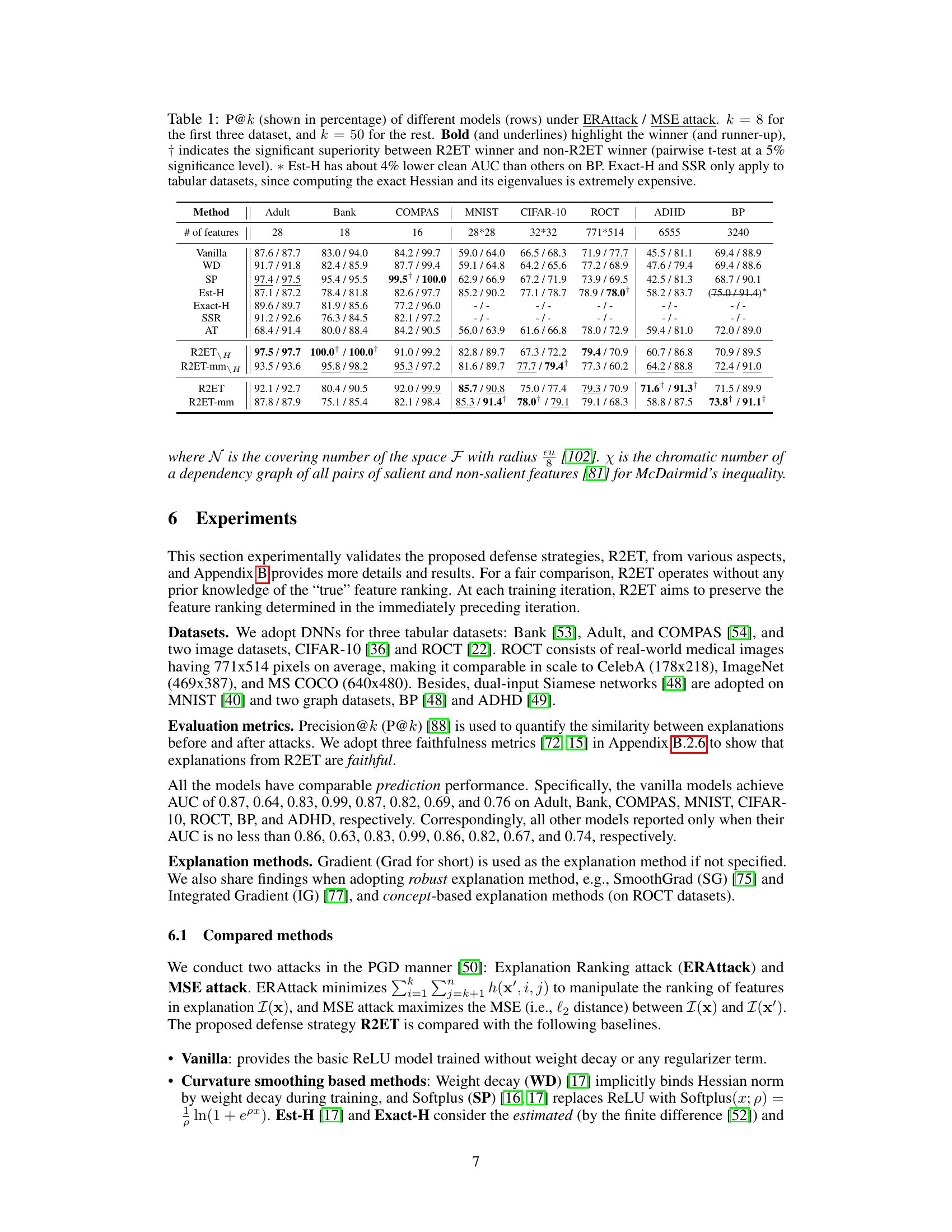

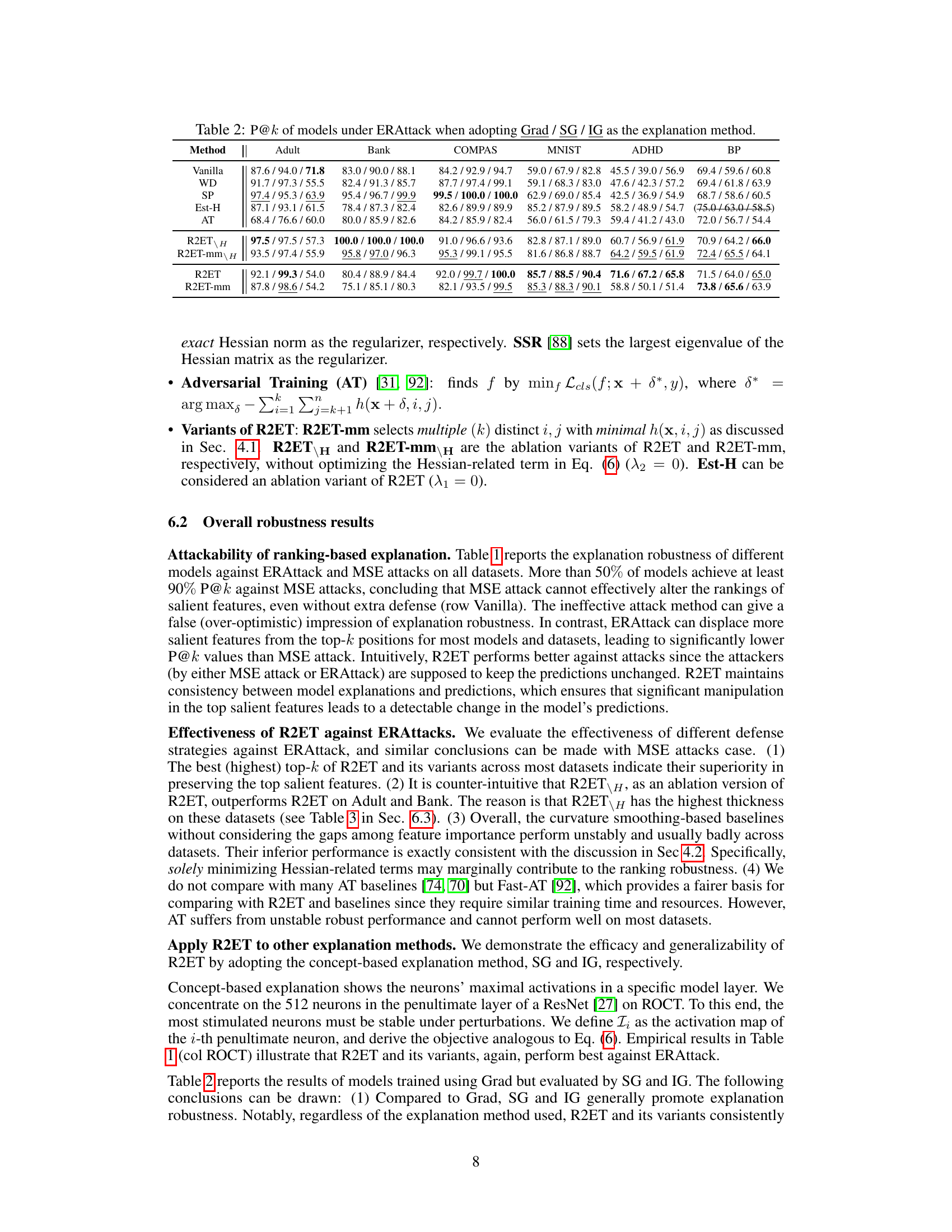

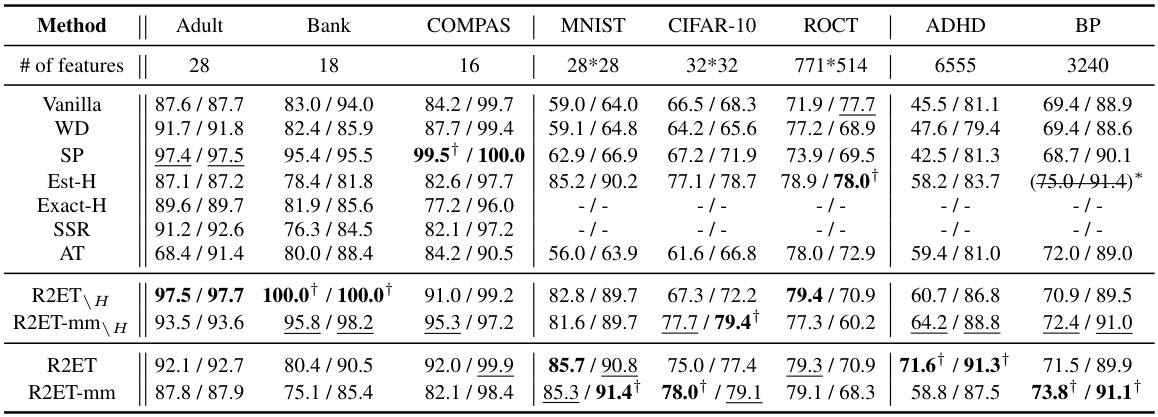

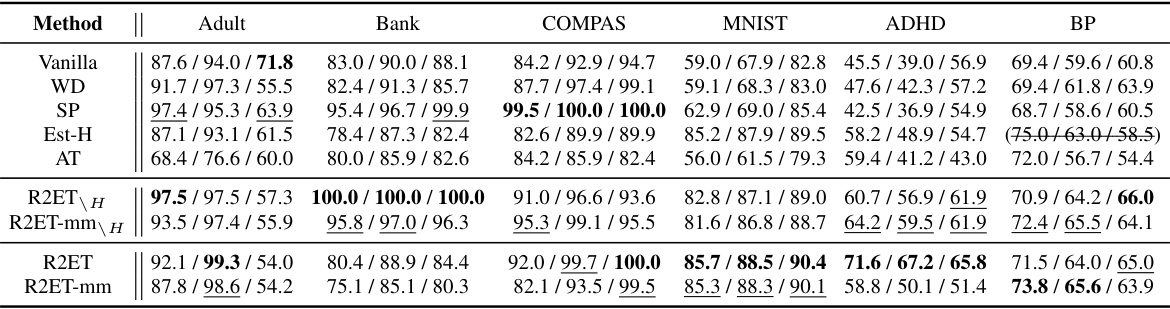

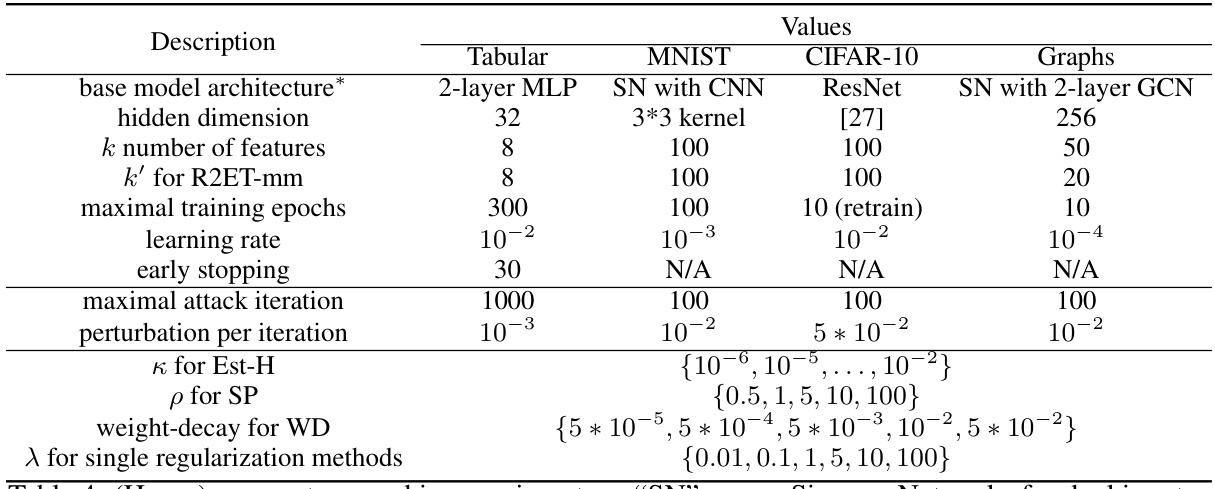

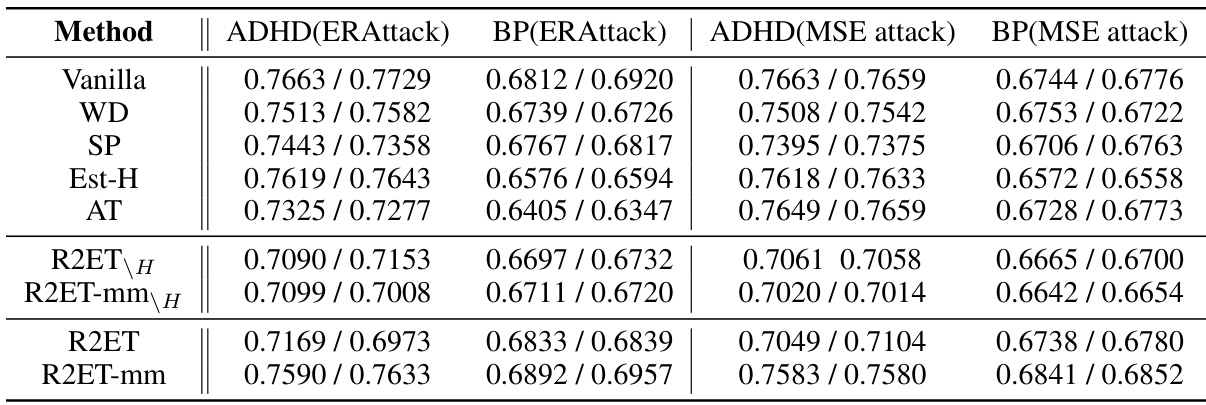

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) performance of various models under two different attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The ‘k’ value represents the number of top features considered. The table highlights the best-performing models for each dataset and attack type, indicating statistical significance where applicable. Note that some methods (Exact-H and SSR) are only applicable to tabular data due to computational constraints.

In-depth insights#

Stable Explanations#

The concept of “Stable Explanations” in machine learning centers on the reliability and consistency of model interpretations. Unstable explanations can drastically change with minor input perturbations, undermining trust and hindering reliable use. A key challenge lies in defining and measuring stability; simply using lp distance metrics may be insufficient as it doesn’t always align with human perception. Therefore, research focuses on developing novel metrics that better capture the robustness of explanations, often considering the stability of top-k salient features identified. Adversarial training (AT) is a common approach to improve stability, but its computational cost can be high. Efficient regularizers offer an alternative, aiming to promote stable explanations during training without the intensive computations of AT. The theoretical underpinnings of stability are also crucial, with connections drawn to certified robustness and multi-objective optimization to provide guarantees. Ultimately, the goal is to develop methods that yield faithful and consistent explanations, improving user trust and enabling more reliable insights from complex models.

R2ET Regularizer#

The R2ET regularizer is a novel approach to enhancing the stability of explanations generated by machine learning models. It directly addresses the limitations of existing methods that rely on LP distances, which often diverge from human perception of stability. R2ET focuses on the ranking of salient features, proposing a new metric, “ranking explanation thickness,” to more accurately measure robustness. Unlike adversarial training (AT), which can lead to computationally expensive arms races, R2ET uses an efficient regularizer to directly optimize the ranking stability. This is theoretically justified by connections to certified robustness, proving its effectiveness in resisting diverse attacks. Furthermore, R2ET’s theoretical foundation is grounded in multi-objective optimization, demonstrating its numerical and statistical stability. The empirical results across multiple datasets and model architectures show that R2ET significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods in explanation stability, highlighting its effectiveness and generalizability.

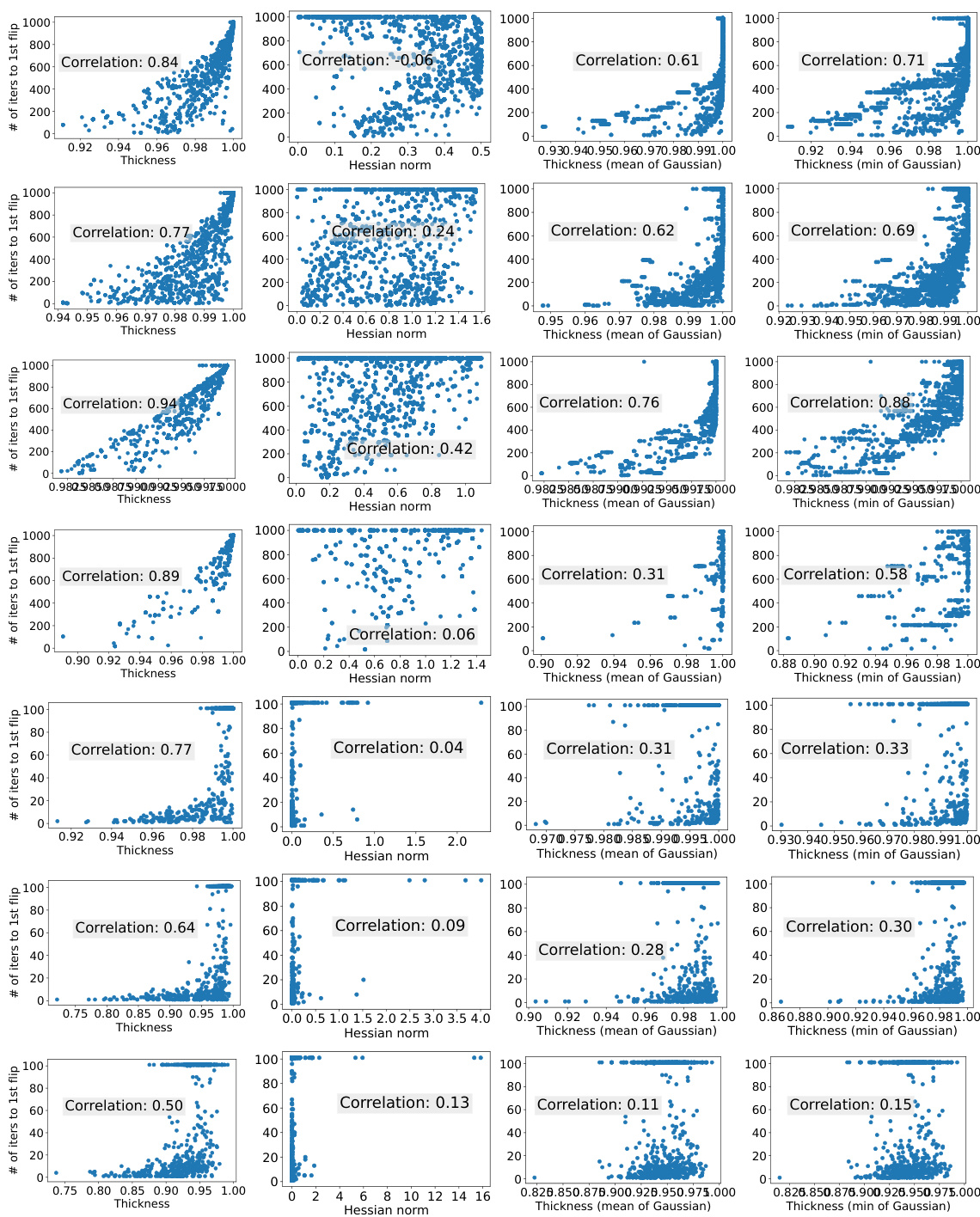

Thickness Metric#

The concept of a ‘Thickness Metric’ in a research paper likely revolves around quantifying the robustness or stability of a model’s explanations, particularly concerning the ranking of salient features. A thicker explanation would be more resistant to adversarial attacks or perturbations, maintaining consistent insights even with slight input modifications. The metric likely goes beyond simple distance measures (like L_p norms) which may not accurately reflect human perception of similarity. It likely focuses on the relative ranking of top-k features, considering the order of importance rather than just the absolute values. This would make it more aligned with how humans assess explanations’ reliability—a small change that doesn’t alter the top features’ ranking signifies higher robustness. The paper likely provides a formal definition and analysis of this metric, potentially exploring different variants and their properties. The usefulness lies in its ability to guide the development of models that produce more stable and trustworthy explanations. A key aspect to consider is whether the metric is computationally tractable and if it can be incorporated into the training process to improve robustness.** Its theoretical grounding may involve aspects of multi-objective optimization** to account for the multiple feature pairs and their interdependent rankings. In essence, a well-defined ‘Thickness Metric’ offers a significant step toward building more reliable and trustworthy machine learning systems.

Attack Robustness#

Attack robustness in machine learning models focuses on the ability of explanations to remain consistent and faithful even when subjected to adversarial attacks. A key challenge lies in defining an appropriate metric for evaluating robustness. While methods based on L_p distances are common, they may not accurately reflect the perceptual stability of explanations as humans interpret them. Therefore, new metrics such as ‘ranking explanation thickness’ are being explored, aiming to align better with human cognitive processes. Adversarial training (AT) is a popular approach to enhance robustness, but it can be computationally expensive and potentially lead to an arms race between attackers and defenders. Alternative training methods that achieve robustness without the computational overhead of AT are needed. Theoretical analysis is crucial to understand and justify the stability and reliability of explanation methods; the connection between stability metrics, optimization, and certified robustness needs further investigation. Ultimately, achieving attack robustness for explanations requires a multi-faceted approach, combining effective metrics, efficient training strategies, and solid theoretical justifications.

Future: Diverse Data#

A crucial aspect for advancing the robustness and generalizability of explanation methods is the exploration of diverse data modalities. The current research predominantly focuses on image and text data, neglecting other crucial areas such as tabular data, time-series data, graph data, and sensor data. Exploring these diverse data types will not only enhance the understanding of how explanation methods perform under different data characteristics but also reveal potential limitations and biases within existing approaches. Future research should prioritize the development of standardized benchmarks and evaluation metrics tailored to these diverse data types; this would facilitate more rigorous comparisons of methods and accelerate the identification of robust and generalizable techniques. Furthermore, investigating how domain expertise can be incorporated into explanation methods for different data modalities is crucial. Combining automated methods with human-in-the-loop approaches would strengthen the development of trustworthy explanation systems across various applications. By addressing these areas, the field can move beyond simplified benchmark datasets toward creating more powerful and reliable explanation tools applicable in real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure demonstrates the process of generating explanations and how adversarial attacks can manipulate them, even with small lp-distances. The left side shows the model training and explanation generation process. The right side uses two examples to show that smaller lp distances between explanations do not guarantee that their top salient features will be similar. This highlights a weakness in using lp distances to assess explanation stability, which motivates the paper’s proposed method.

This figure illustrates the process of explanation generation and adversarial attacks. The left side shows the steps involved in model training and explanation generation, highlighting adversarial attacks that manipulate the input to distort the explanation. The right side uses two examples to demonstrate that a small L_p distance between the original explanation and a perturbed explanation does not guarantee similarity in top-k salient features.

This figure illustrates the process of explanation generation and adversarial attacks. The left side shows the training of a model and the subsequent generation of explanations for a target input, followed by adversarial attacks that manipulate the input to distort the explanation. The right side provides two examples to demonstrate that small lp distances between explanations do not necessarily imply that the top salient features are similar. It highlights the limitations of relying on lp distance as a metric for evaluating the stability of explanations.

This figure illustrates the process of explanation generation and adversarial attacks. The left side shows a model training process followed by explanation generation from a given input using an explanation method. Then, adversarial attacks manipulate the input, aiming to change the explanation while preserving the original prediction. The right side shows two examples of explanation maps, demonstrating that small lp distances between explanations do not always indicate similar top salient features. This highlights the limitation of using lp distance as a metric for assessing explanation stability.

This figure illustrates the process of generating explanations and adversarial attacks. The left side shows the model training and explanation generation, while the right side uses two examples to demonstrate that a small lp distance between explanations does not necessarily mean that the top salient features are similar. This highlights the limitations of using lp distance as a metric for evaluating explanation stability.

This figure demonstrates the process of generating explanations and how adversarial attacks can manipulate them. The left side illustrates the training process and generation of explanations for a target input, followed by adversarial attacks. The right side uses examples to highlight that a small lp distance between two explanations does not guarantee that they have similar top-k features. This is a key point to the paper’s argument about the limitations of using lp distance as a metric for evaluating explanation stability.

This figure illustrates the process of generating explanations and the impact of adversarial attacks. The left side shows the steps involved in model training and explanation generation, while the right side demonstrates how small L_p distance between explanations does not guarantee similarity in top salient features. Two examples highlight how a perturbed explanation can significantly differ from the original explanation, even with a small L_p distance.

This figure illustrates the process of explanation generation and adversarial attacks. The left side shows the model training and the generation of explanations using various methods. The right side shows two examples of saliency maps, demonstrating that a small L_p distance between perturbed and original explanations does not guarantee similarity in the top-k salient features. This highlights the limitations of using L_p distance alone to assess explanation stability.

More on tables

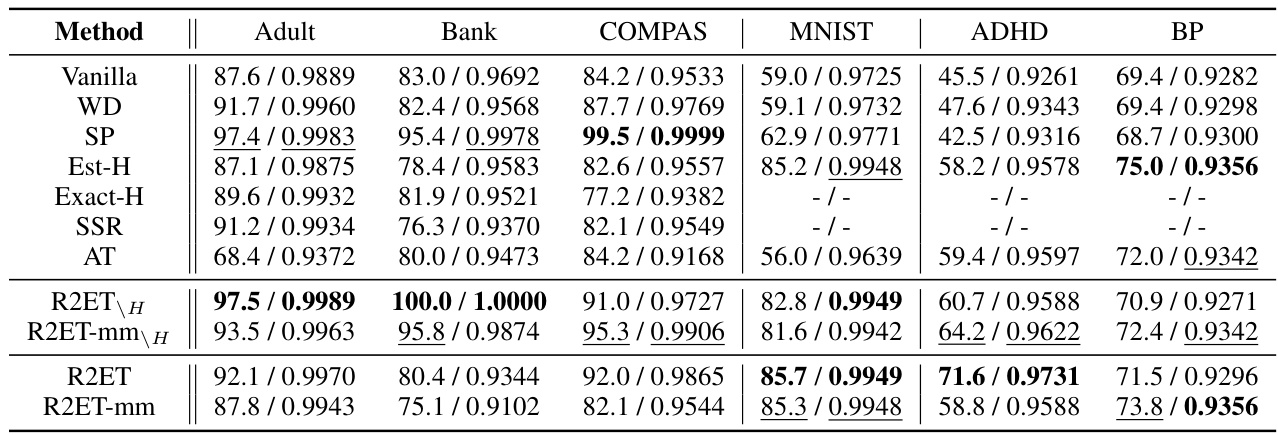

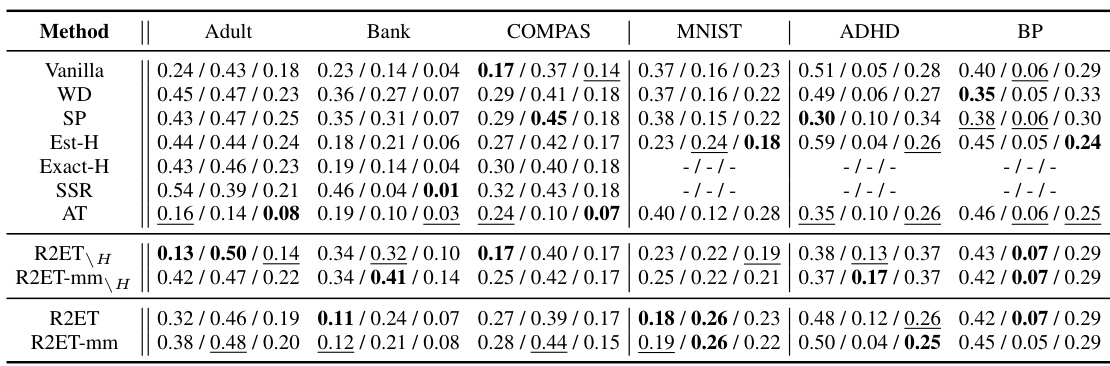

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) values for various models under two attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The ‘k’ value represents the number of top features considered. The table compares the performance of several methods (Vanilla, WD, SP, Est-H, Exact-H, SSR, AT, R2ET variants) across different datasets (Adult, Bank, COMPAS, MNIST, CIFAR-10, ROCT, BP, ADHD). Bold values indicate statistically significant improvements by R2ET compared to other methods. Note that Exact-H and SSR are computationally expensive, and only used on tabular data.

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) scores for several models across various datasets under two different attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The value of k (the number of top features considered) varies across datasets. The table highlights the best performing model for each dataset and attack method, indicating statistical significance where appropriate. Note that certain methods are not applicable to all datasets due to computational constraints.

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) performance of various models under two different attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The P@k metric shows the proportion of correctly ranked top-k features after an attack. The table compares the robustness of several methods, including vanilla training, weight decay, softplus activation, Hessian-based methods, adversarial training, and the proposed R2ET method. Results are shown for several datasets with different numbers of features. Statistical significance is indicated using a † symbol.

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) scores for various models under two different attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The P@k metric evaluates the similarity of explanations before and after an attack. The table shows results for several datasets, highlighting the best-performing model (in bold) for each dataset and attack method. Statistical significance is also indicated.

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) scores for various models under two different attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The P@k metric measures the proportion of correctly ranked top-k features after the attacks. The table shows results for several datasets and compares different explanation robustness methods, highlighting the best-performing model (R2ET) in bold. Statistical significance testing is included, and notes are provided regarding differences in clean AUC scores and the applicability of certain methods to specific datasets.

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) values for various models under two different attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The P@k metric assesses the robustness of explanations by measuring how well the top-k important features remain consistent after an attack. The table compares the performance of several models, including Vanilla, weight decay (WD), Softplus (SP), Hessian-related methods (Est-H, Exact-H), Adversarial Training (AT), and the proposed Robust Ranking Explanation via Thickness (R2ET) and its variants. The number of top-k features considered (k) is 8 for the first three datasets and 50 for the remaining datasets. Statistical significance is indicated using the † symbol. The asterisk (*) indicates a lower clean AUC (Area Under Curve) for the Est-H method on the BP dataset. The table notes that two of the methods (Exact-H and SSR) are limited to tabular datasets due to computational constraints.

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) scores for various models under two different attack methods: Explanation Ranking attack (ERAttack) and Mean Squared Error attack (MSE attack). The P@k metric assesses the robustness of explanations by measuring the overlap between the top-k features identified before and after an attack. The table compares several models (Vanilla, WD, SP, Est-H, Exact-H, SSR, AT, R2ET, R2ET-mm, R2ET_H, R2ET-mm_H), across multiple datasets (Adult, Bank, COMPAS, MNIST, CIFAR-10, ROCT, BP, ADHD), highlighting the best performing model for each scenario using bold text and underlining. Statistical significance is indicated by a † symbol. A note is included regarding the computational cost of Exact-H and SSR, which limits their applicability to tabular datasets.

This table presents the Precision@k (P@k) values for various models under two different attack methods (ERAttack and MSE attack). It shows the performance of different explanation robustness methods (Vanilla, WD, SP, Est-H, Exact-H, SSR, AT, R2ET, R2ET-mm, R2ET_H, R2ET-mm_H) across multiple datasets (Adult, Bank, COMPAS, MNIST, CIFAR-10, ROCT, BP, ADHD). Higher P@k indicates better robustness against attacks. Statistical significance is indicated using a dagger (†) symbol.

Full paper#