TL;DR#

Current OOD detection methods for generative language models (GLMs) struggle with high-density output spaces, a common characteristic of mathematical reasoning. These methods often rely on static embedding comparisons, which are ineffective in such scenarios because the output embeddings of different samples tend to converge, obscuring meaningful distinctions. This convergence is termed ‘pattern collapse’. The paper highlights the limitations of existing GLMs in accurately handling mathematical reasoning problems due to this pattern collapse.

To address this, the paper proposes a novel trajectory-based method called TV Score. This method focuses on the dynamic changes in embeddings as a GLM processes input, rather than just the final embedding. By analyzing the volatility of these embedding trajectories, TV Score effectively distinguishes between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) samples, even when their final embeddings are similar. Extensive experiments demonstrate that TV Score significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods on various mathematical reasoning datasets and GLMs. The method’s generalizability is also explored, showing promise for application to other tasks with high-density outputs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical issue of out-of-distribution (OOD) detection in the context of generative language models (GLMs), particularly for complex tasks like mathematical reasoning. It introduces a novel trajectory-based approach that outperforms traditional methods, opening new avenues for improving GLM robustness and reliability in real-world applications where unexpected inputs are common.

Visual Insights#

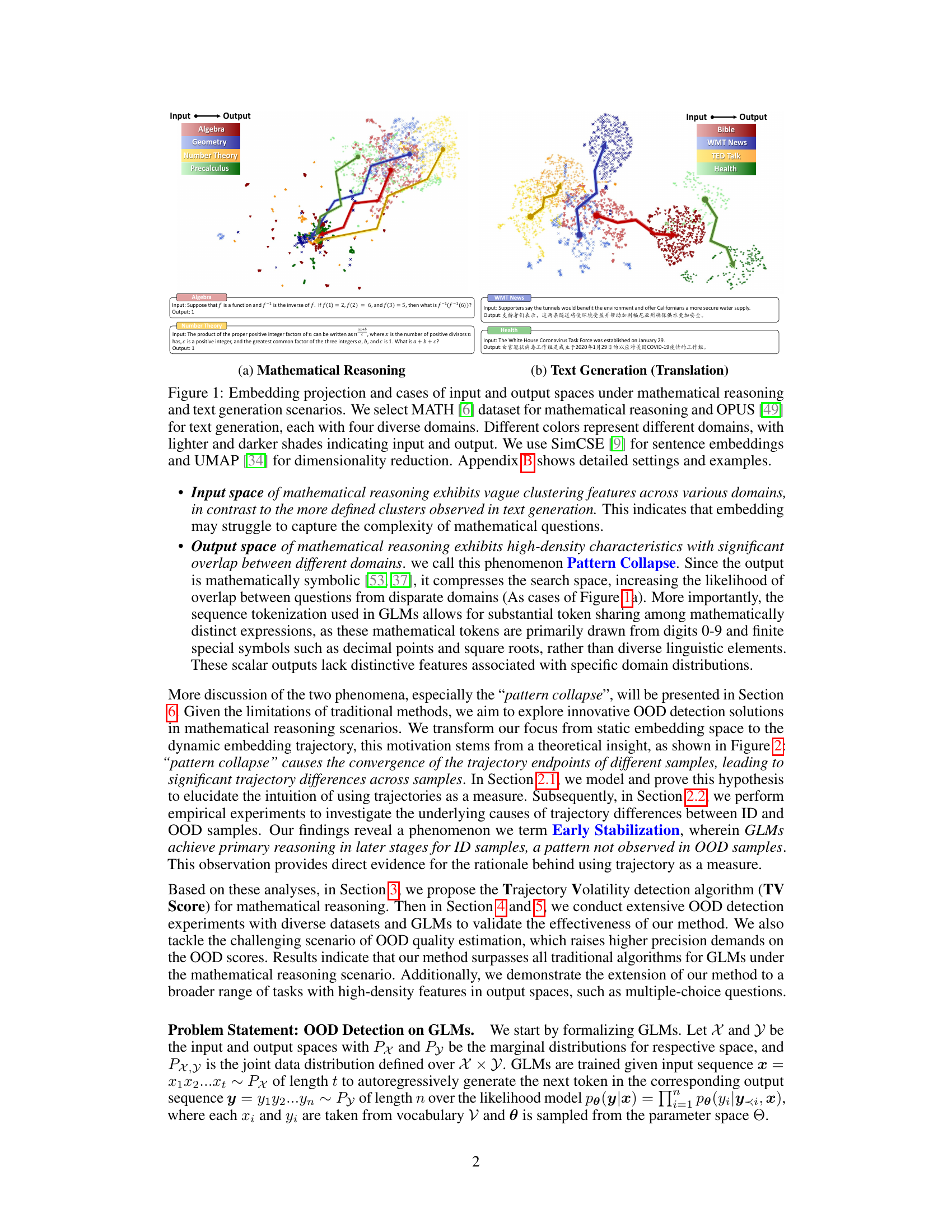

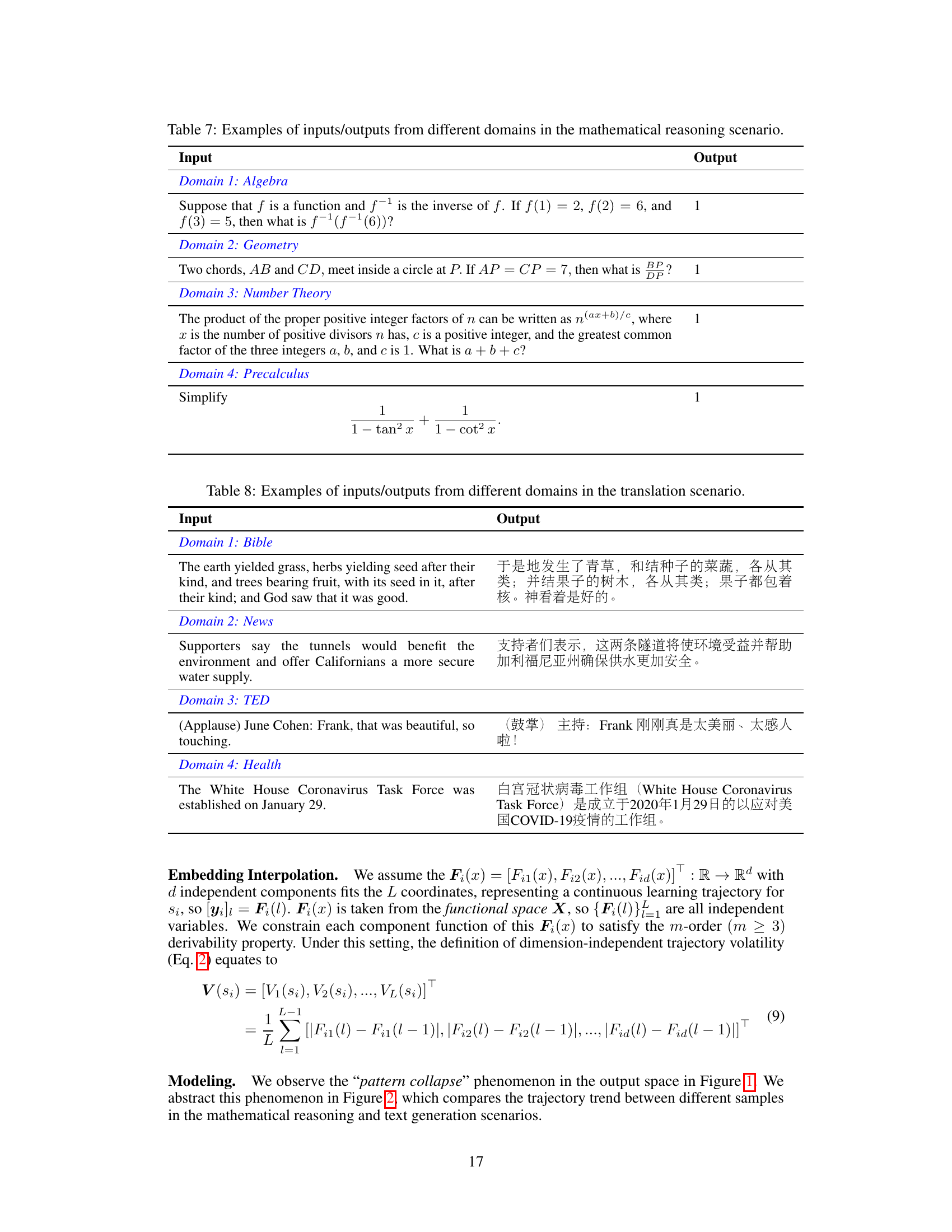

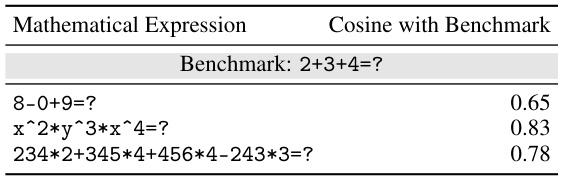

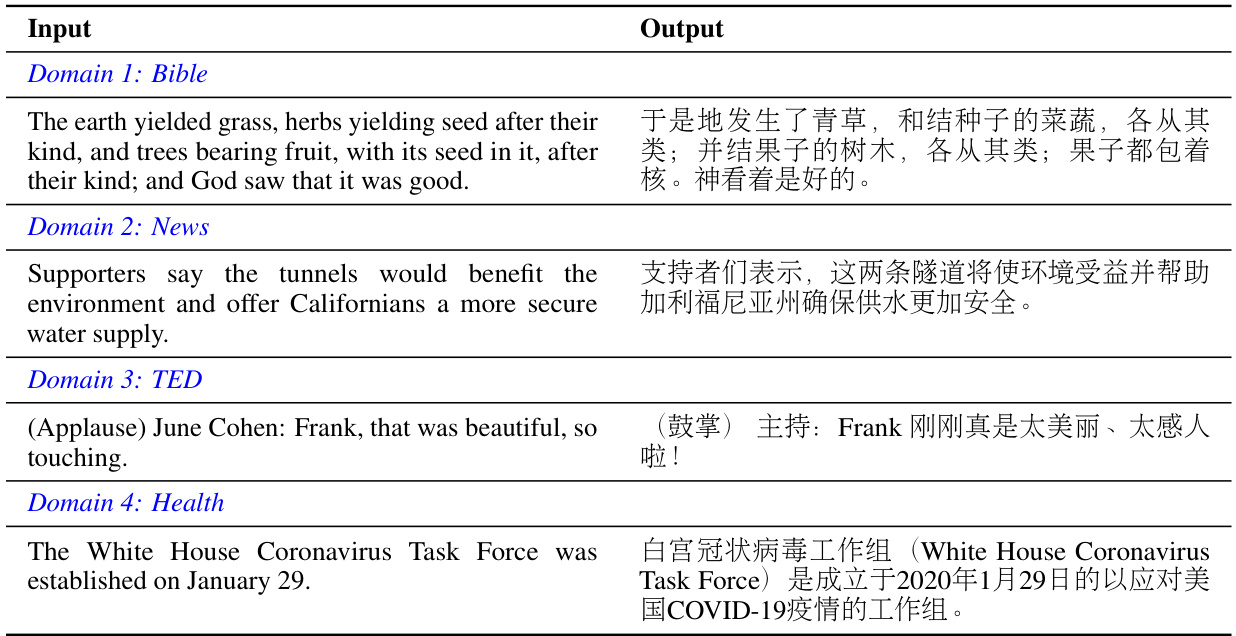

🔼 This figure shows the visualization of input and output embedding spaces for both mathematical reasoning and text generation tasks. It uses the MATH dataset for mathematical reasoning and the OPUS dataset for text generation, each with four different domains. The visualizations highlight the differences in the clustering of embeddings between the two tasks, particularly noting the phenomenon of ‘pattern collapse’ in the output space of mathematical reasoning. SimCSE was used for sentence embedding and UMAP for dimensionality reduction.

read the caption

Figure 1: Embedding projection and cases of input and output spaces under mathematical reasoning and text generation scenarios. We select MATH [6] dataset for mathematical reasoning and OPUS [49] for text generation, each with four diverse domains. Different colors represent different domains, with lighter and darker shades indicating input and output. We use SimCSE [9] for sentence embeddings and UMAP [34] for dimensionality reduction. Appendix B shows detailed settings and examples.

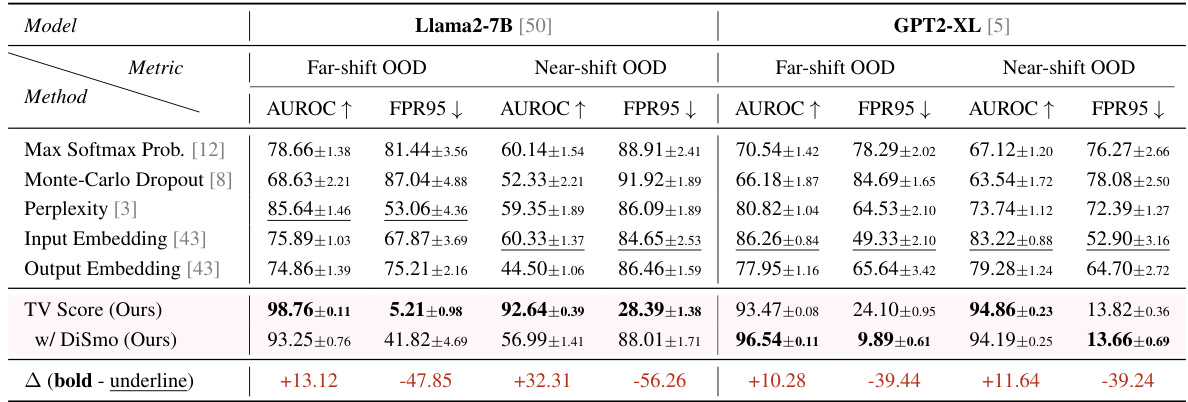

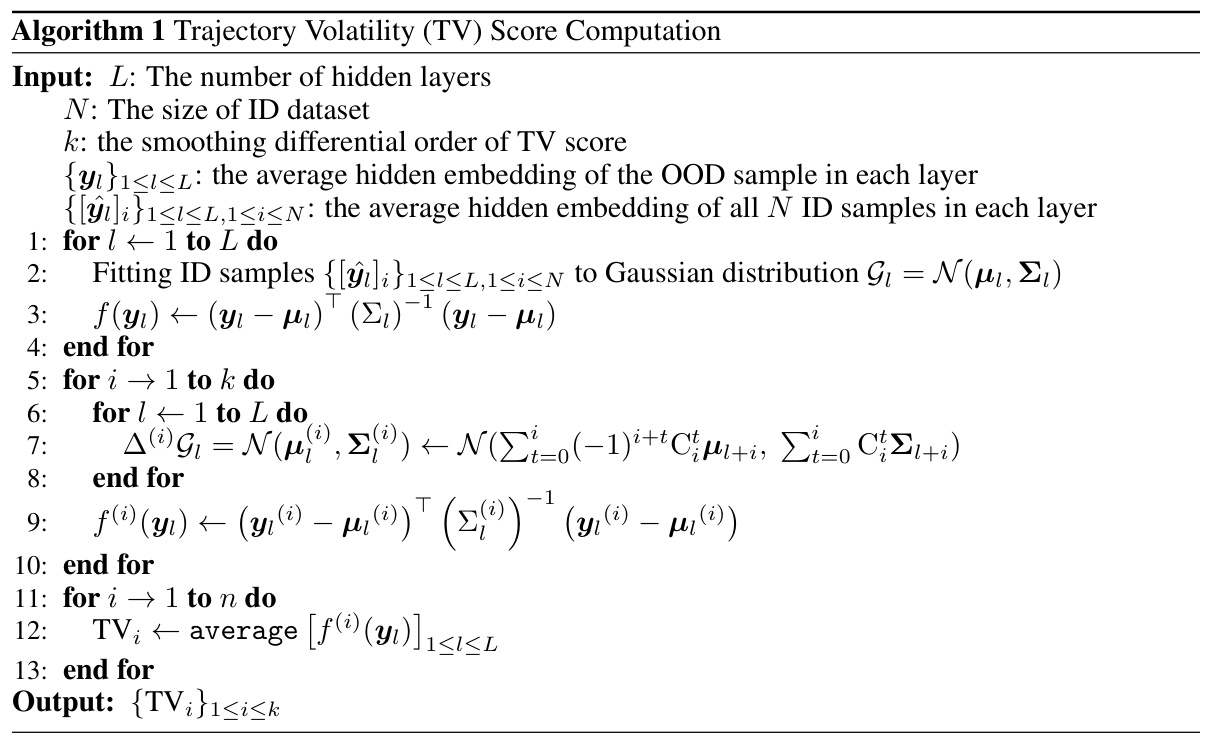

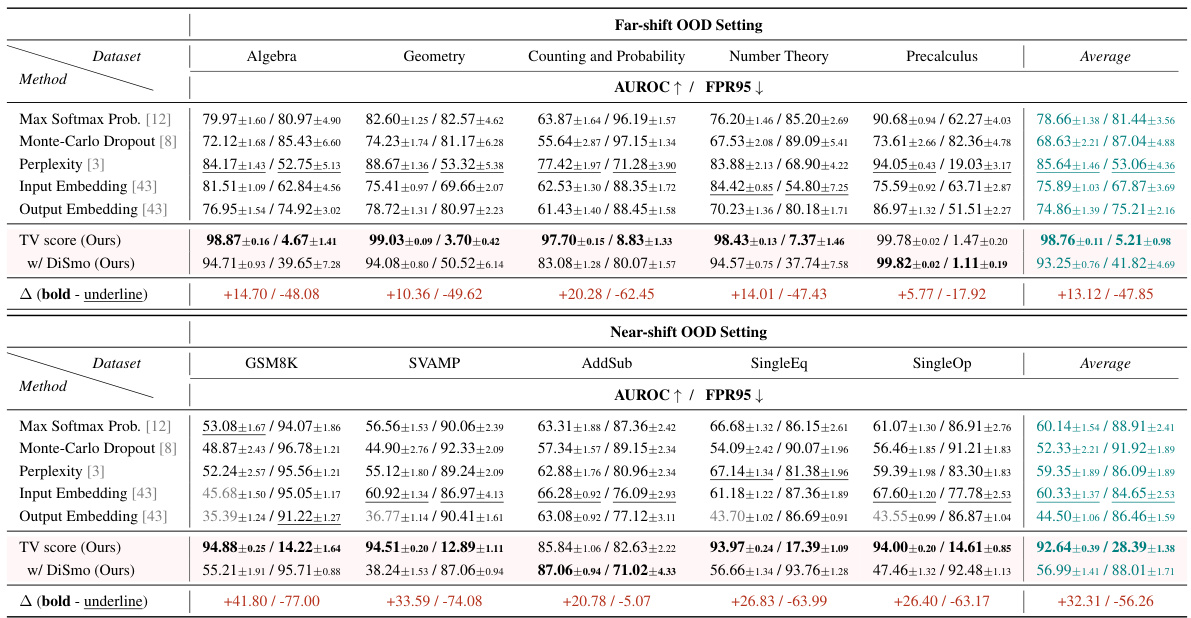

🔼 This table presents the AUROC and FPR95 scores for various OOD detection methods on both far-shift and near-shift OOD scenarios. The results are shown for two different language models (Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL) and are averaged across multiple samplings to account for variance. The table compares a proposed trajectory volatility method (TV Score) against five baseline methods, highlighting its superior performance.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

In-depth insights#

OOD in Math#

Out-of-distribution (OOD) detection in mathematical reasoning presents unique challenges due to the high density of the output space, a phenomenon termed ‘pattern collapse’. Traditional methods relying on embedding distances are ineffective because the embeddings of different samples converge in the output space. This paper proposes a novel trajectory-based approach (TV Score) that focuses on the dynamic changes of embeddings during the generation process, rather than the static embeddings themselves. By analyzing the volatility of these trajectories, the method effectively distinguishes between in-distribution (ID) and OOD samples. The key insight is that OOD samples exhibit ’early stabilization,’ meaning their embedding trajectories converge earlier than ID samples. This characteristic is exploited to design a robust algorithm, showcasing superior performance compared to existing techniques. This approach not only enhances OOD detection but also facilitates OOD quality estimation, demonstrating potential applicability beyond mathematical reasoning to other tasks with high-density output spaces, such as multiple-choice questions.

Trajectory-based OOD#

Trajectory-based out-of-distribution (OOD) detection offers a novel approach to identifying anomalies in data generated by complex models, particularly generative language models (GLMs). Unlike traditional methods that rely on static embeddings or uncertainty estimates, a trajectory-based approach captures the dynamic evolution of embeddings as a model processes input. This dynamic perspective is particularly valuable in scenarios like mathematical reasoning, where output spaces are dense, leading to the ‘pattern collapse’ phenomenon where distinct inputs converge to similar outputs. By analyzing the volatility of the embedding trajectory, trajectory-based methods can discern subtle differences that might be missed by static methods. This approach is theoretically sound and empirically validated, showing improvements over static embedding methods in various scenarios. A key advantage is the ability to adapt to high-density output spaces and extend to tasks beyond mathematical reasoning, including multiple choice questions. However, the limited availability of sufficiently large datasets for mathematical reasoning poses a challenge in robustly evaluating the approach.

TV Score Algorithm#

The core idea behind the hypothetical ‘TV Score Algorithm’ appears to revolve around leveraging the dynamic trajectory of embeddings within a generative language model (GLM) to detect out-of-distribution (OOD) data, particularly in scenarios like mathematical reasoning where traditional static embedding methods fall short. Instead of solely relying on the final embedding’s position, the algorithm analyzes the entire path taken by the embedding as it progresses through the GLM’s layers. This approach is motivated by the observation of a phenomenon called ‘pattern collapse’, where distinct samples in the input space converge to similar points in the high-density output space of mathematical reasoning. By calculating trajectory volatility, the algorithm potentially captures subtle shifts and differences that would be missed by traditional static methods. The algorithm’s success hinges on the assumption that OOD samples exhibit greater trajectory volatility compared to in-distribution (ID) samples. The method’s novelty lies in its shift from analyzing the static embedding to analyzing its dynamic trajectory, promising better handling of high-density output spaces. The practical implementation likely involves calculating trajectory volatility measures (e.g., using L2 norms of difference vectors between adjacent layers) and establishing a threshold to distinguish between ID and OOD data. A key benefit is its potential generalizability to other tasks with high-density output spaces.

Empirical Analysis#

An empirical analysis section in a research paper would typically present results from experiments or observations designed to test the study’s hypotheses or answer its research questions. It should clearly state the methods used, including data collection techniques, experimental design, and any relevant statistical analyses. The presentation of results should be clear and concise, ideally using tables and figures to enhance readability. Critical aspects include a discussion of the limitations of the experimental design and any potential sources of bias, along with a thoughtful interpretation of the findings, relating them back to the paper’s theoretical framework. A strong empirical analysis section not only presents results but provides a rigorous evaluation of their validity, reliability, and implications, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the findings.

Generalization#

Generalization in machine learning models, especially large language models (LLMs), is a critical yet challenging area. This paper focuses on the problem of out-of-distribution (OOD) detection within the context of mathematical reasoning. The core argument revolves around the limitations of traditional embedding-based approaches due to the high-density nature of the output space in mathematical problems, leading to a phenomenon called “pattern collapse.” This means that different mathematical problems converge to similar embeddings, making it difficult to distinguish between in-distribution and OOD examples. The authors propose a novel trajectory-based method that uses dynamic embedding analysis to address this limitation. By considering the trajectory of embeddings through layers of the model, rather than relying solely on the final embedding, they are able to capture subtle differences which lead to improved generalization performance. This dynamic approach is shown to be more effective than static embedding methods in handling the “pattern collapse” issue. The paper also emphasizes the significance of trajectory volatility, proposing a novel metric (TV Score) to quantify it, resulting in a more robust and accurate OOD detection system. The successful application of the proposed technique extends beyond mathematical reasoning to other tasks with similar high-density output spaces, suggesting broad applicability and generalizability of the methodology.

More visual insights#

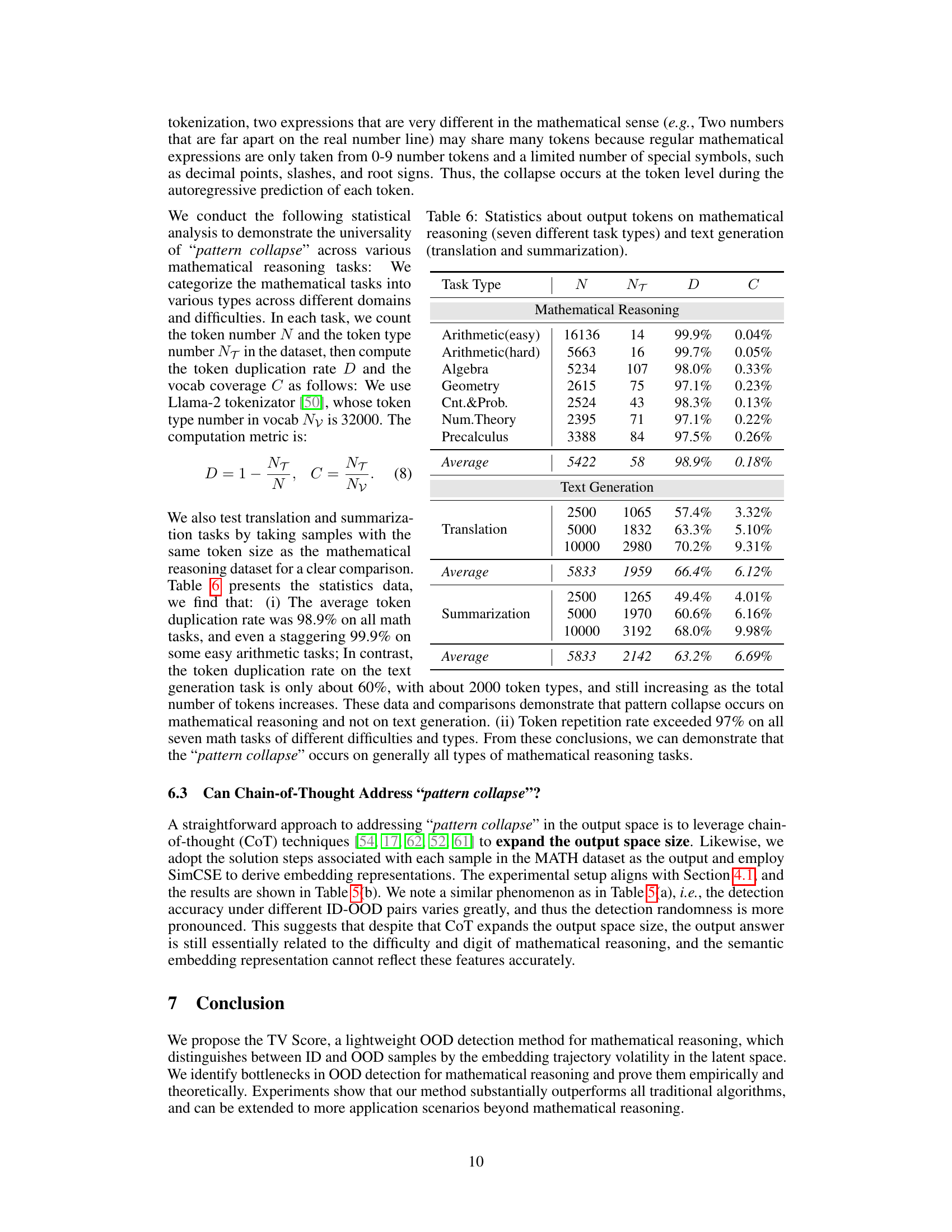

More on figures

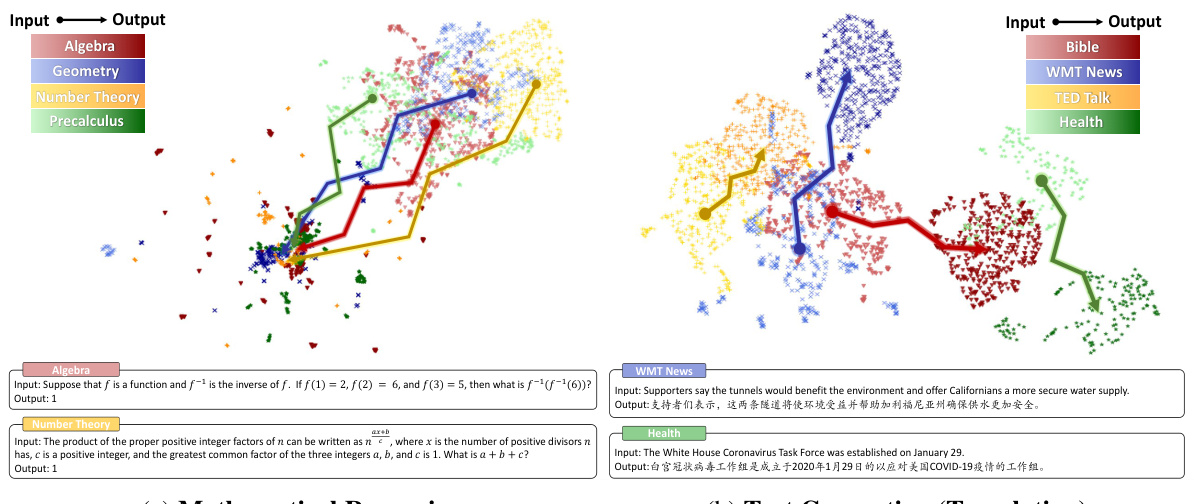

🔼 The figure shows a comparison of embedding trajectory behavior between mathematical reasoning and text generation tasks. In mathematical reasoning, the ‘pattern collapse’ phenomenon is observed, where trajectories from initially distinct samples converge towards the same endpoint in the output space. This is in contrast to text generation, where trajectories remain more distinct. The difference in trajectory behavior is highlighted as a key aspect for differentiating in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) samples in mathematical reasoning.

read the caption

Figure 2: The 'pattern collapse' phenomenon only exists in mathematical reasoning scenarios, where two samples initially distant in distance will converge approximately at the endpoint after undergoing embedding shifts, and does not occur in text generation scenarios. This produces a greater likelihood of trajectory variation under different samples in mathematical reasoning.

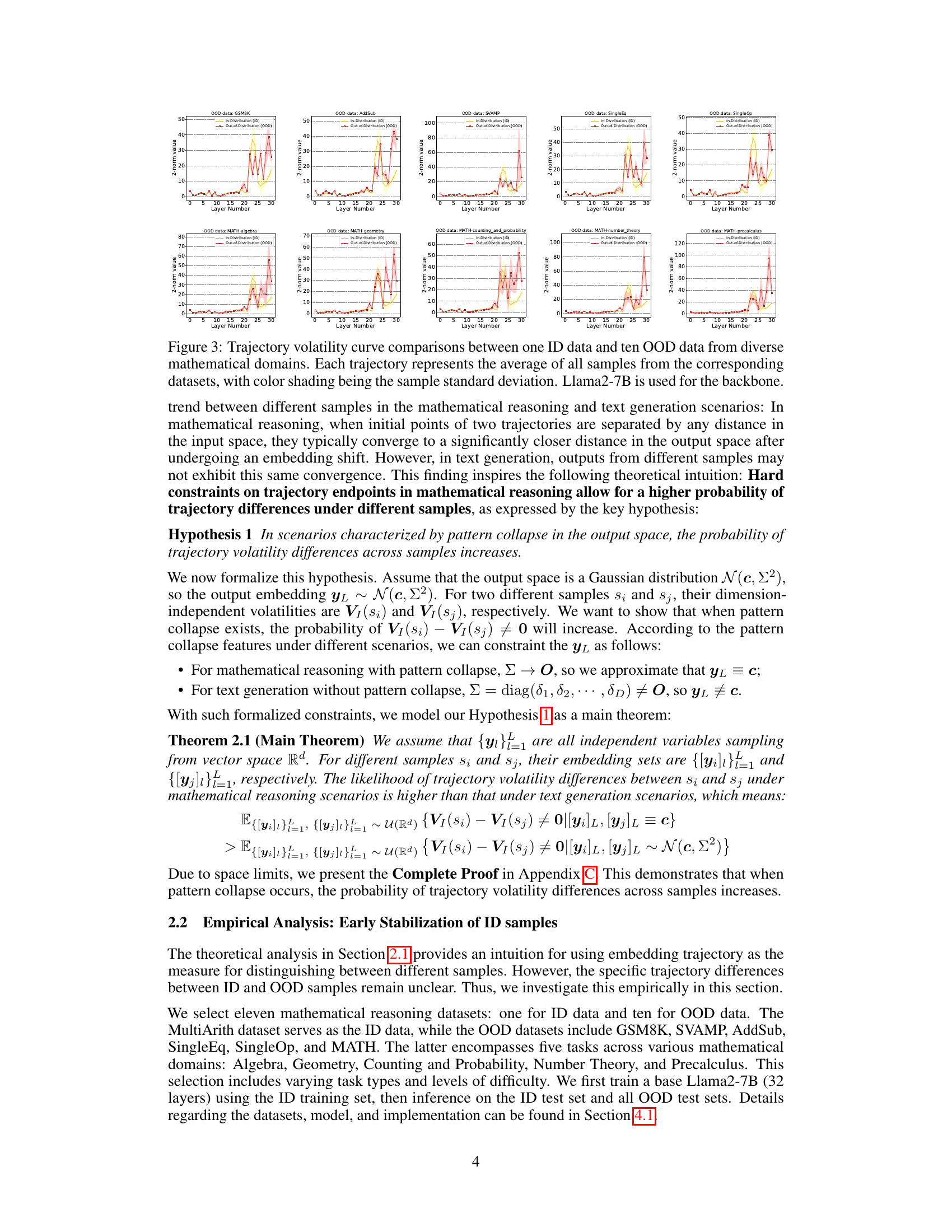

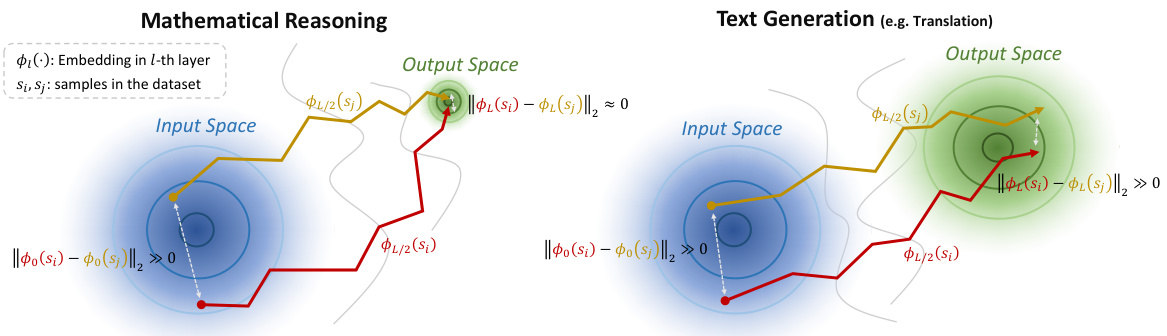

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of trajectory volatility curves for in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) data across various mathematical domains. Each line represents the average 2-norm of the embedding differences between adjacent layers for a dataset, showing the volatility of the embedding trajectory during the model’s reasoning process. The color shading around each line indicates the standard deviation of the volatility values across samples within the dataset. Llama2-7B was used as the language model in these experiments. The figure demonstrates that OOD samples exhibit significantly different trajectory volatility patterns compared to ID samples, supporting the use of trajectory volatility as a metric for OOD detection in mathematical reasoning.

read the caption

Figure 3: Trajectory volatility curve comparisons between one ID data and ten OOD data from diverse mathematical domains. Each trajectory represents the average of all samples from the corresponding datasets, with color shading being the sample standard deviation. Llama2-7B is used for the backbone.

🔼 This figure shows the visualization of input and output spaces for both mathematical reasoning and text generation tasks using the dimensionality reduction technique UMAP. The data used are from MATH and OPUS datasets, each having four different domains. Each domain is represented by a different color. The figure highlights the significant difference between the two tasks. Mathematical reasoning demonstrates less defined clustering of both input and output domains, showing a phenomenon termed as ‘pattern collapse’. In contrast, the text generation shows more distinct input and output domains.

read the caption

Figure 1: Embedding projection and cases of input and output spaces under mathematical reasoning and text generation scenarios. We select MATH [6] dataset for mathematical reasoning and OPUS [49] for text generation, each with four diverse domains. Different colors represent different domains, with lighter and darker shades indicating input and output. We use SimCSE [9] for sentence embeddings and UMAP [34] for dimensionality reduction. Appendix B shows detailed settings and examples.

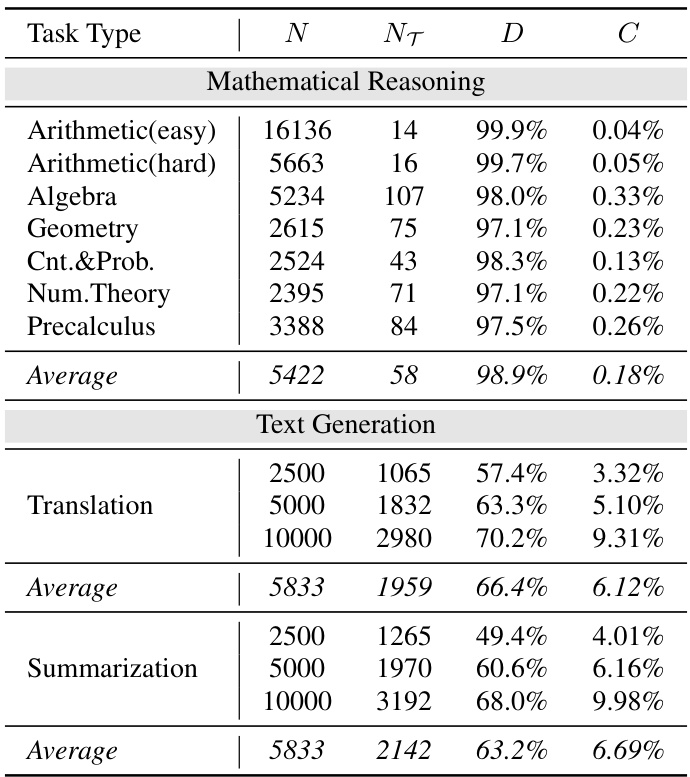

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of the offline detection experiments. It compares the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) and the False Positive Rate at 95% True Positive Rate (FPR95) of the proposed TV Score method against five baseline methods across two scenarios: far-shift OOD and near-shift OOD. The results are averaged across multiple samplings and show the performance for both Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL models. Detailed per-dataset results are available in the appendix.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

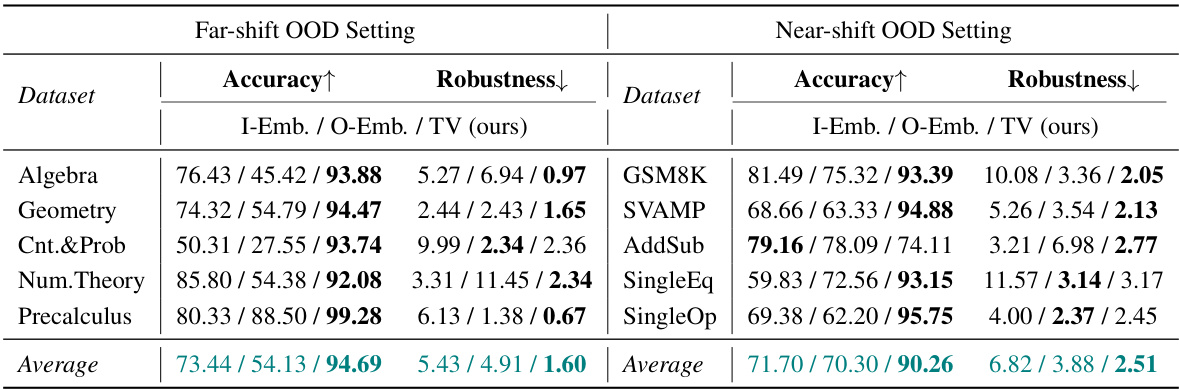

🔼 This table presents the accuracy and robustness results of the online OOD detection. The accuracy reflects the correctness of identifying OOD samples, while the robustness indicates the stability of the performance across various sampling. The results are compared against embedding-based methods, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed TV Score method.

read the caption

Table 2: Accuracy and Robustness results of the Online Detection scenario. We mainly compare our method with embedding-based methods, and bold denotes the best among these methods.

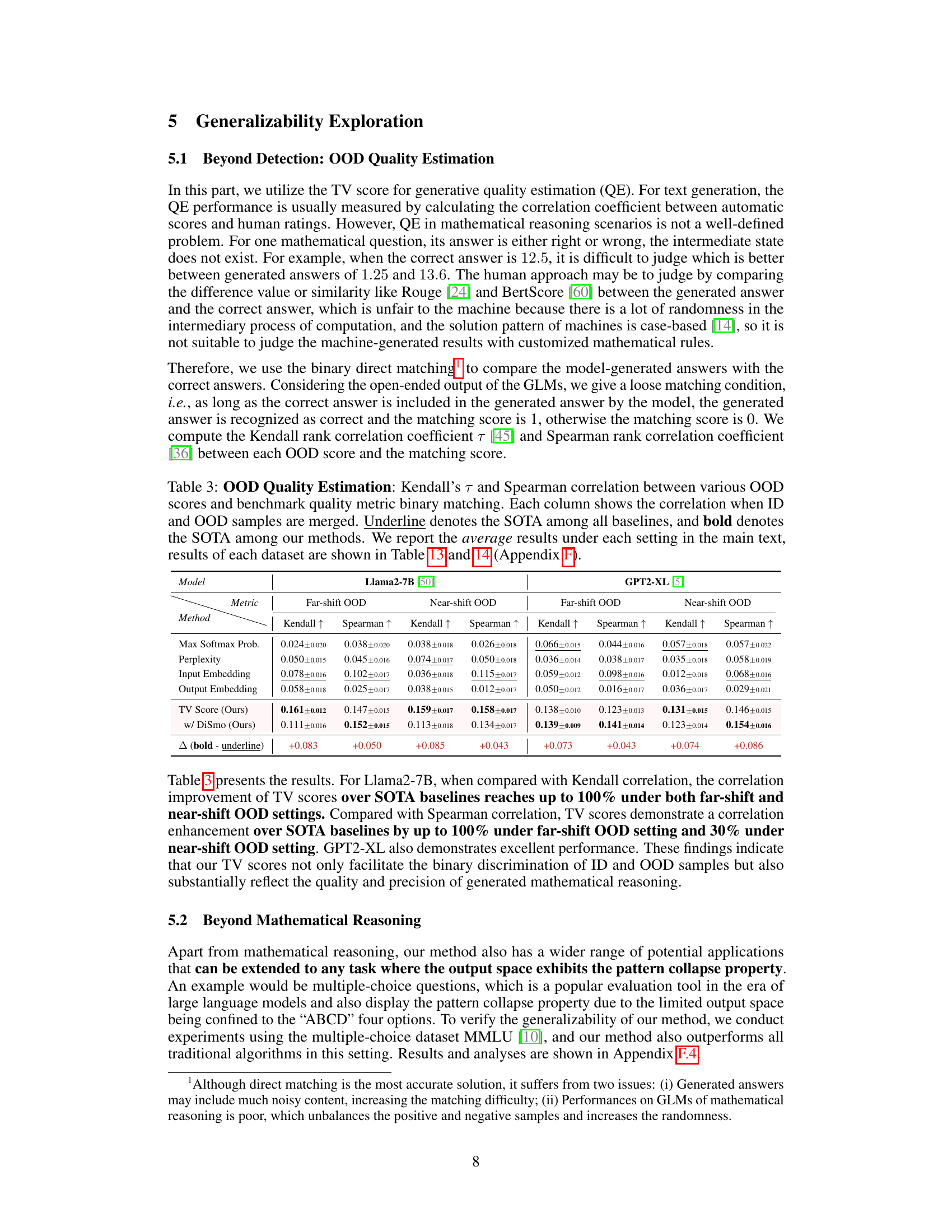

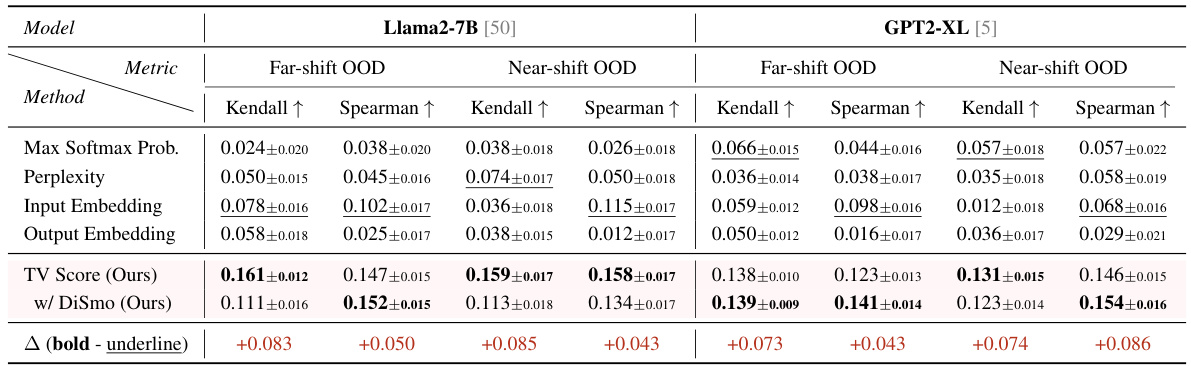

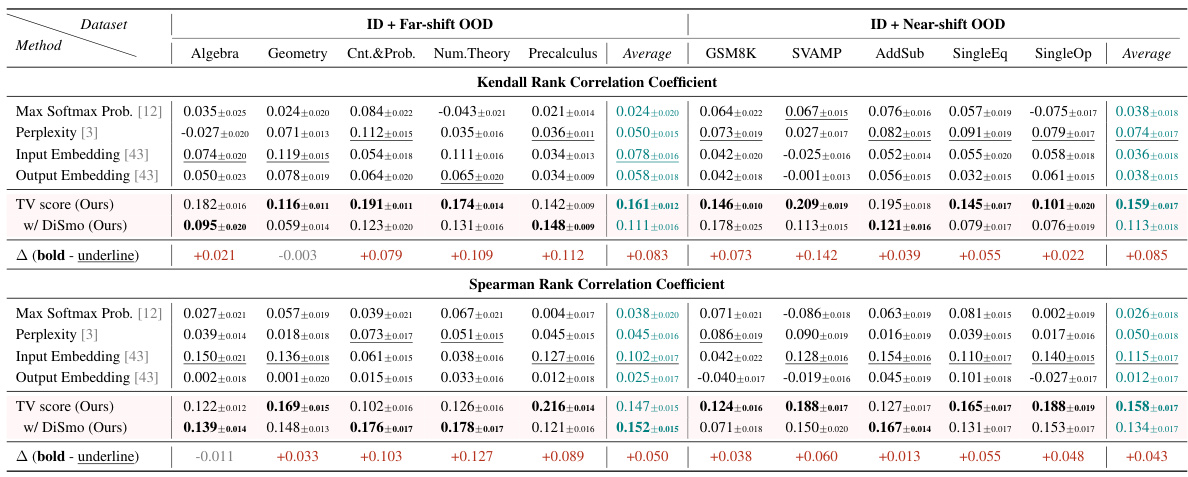

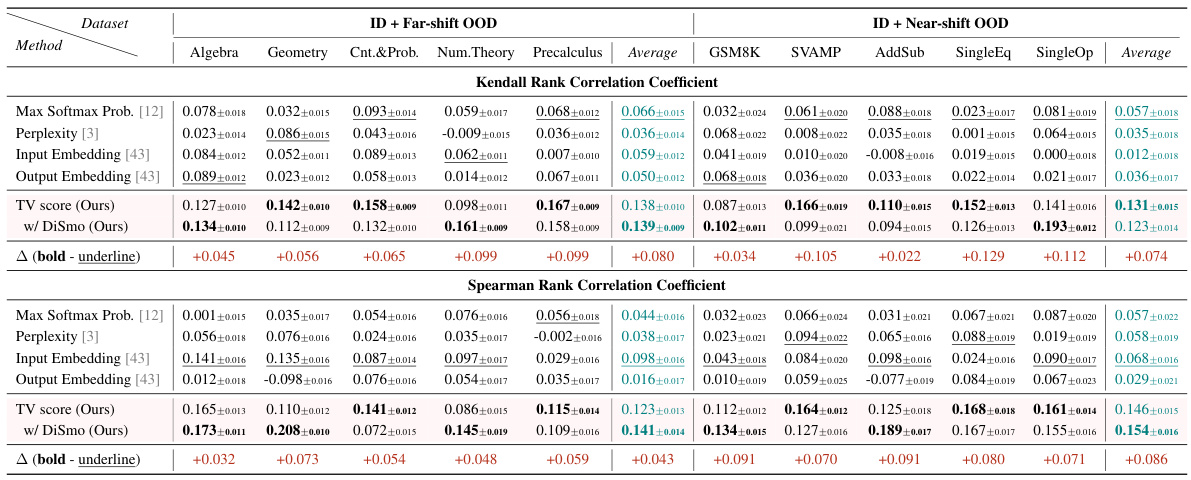

🔼 This table presents the Kendall’s Tau and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients between different OOD detection methods’ scores and a binary matching metric for OOD quality estimation. The binary matching metric checks if the model-generated answer contains the correct answer. The results are shown separately for far-shift and near-shift OOD scenarios, and the best-performing methods (SOTA) are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 3: OOD Quality Estimation: Kendall's T and Spearman correlation between various OOD scores and benchmark quality metric binary matching. Each column shows the correlation when ID and OOD samples are merged. Underline denotes the SOTA among all baselines, and bold denotes the SOTA among our methods.

🔼 This table shows the Kendall’s Tau and Spearman correlation coefficients between different out-of-distribution (OOD) detection scores and a benchmark quality metric (binary matching). The results are presented separately for far-shift and near-shift OOD scenarios, comparing the performance of the proposed TV Score method against several baselines. The table highlights the best-performing methods for each scenario and metric.

read the caption

Table 3: OOD Quality Estimation: Kendall's T and Spearman correlation between various OOD scores and benchmark quality metric binary matching. Each column shows the correlation when ID and OOD samples are merged. Underline denotes the SOTA among all baselines, and bold denotes the SOTA among our methods.

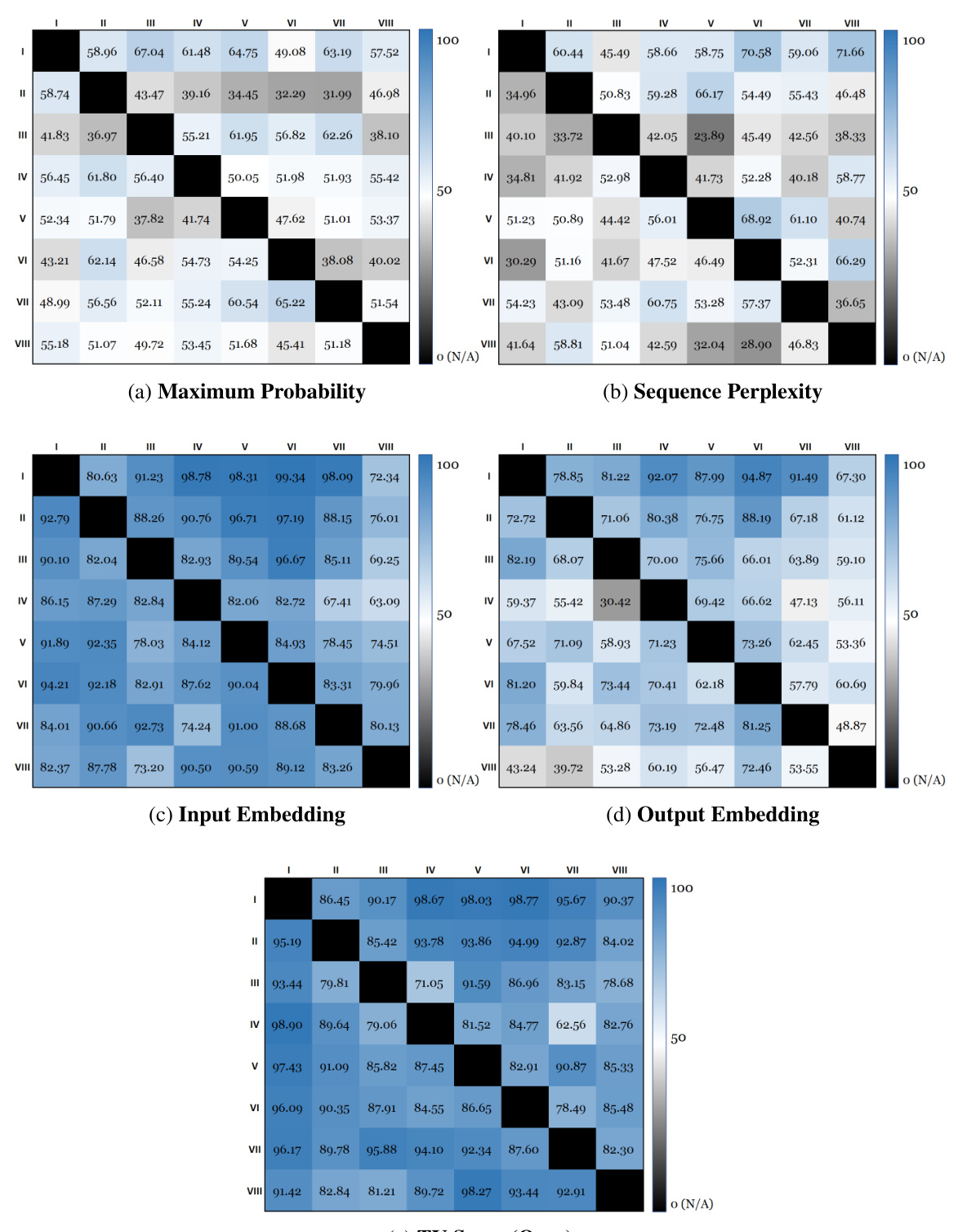

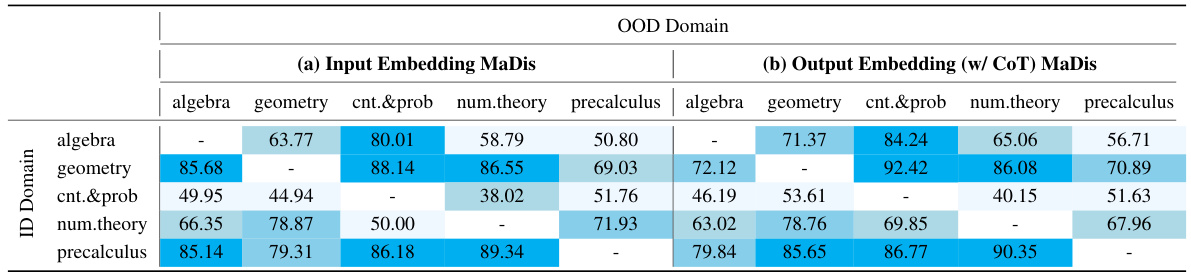

🔼 This table presents the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) scores for the input embedding Mahalanobis distance and the output embedding (with Chain-of-Thought) Mahalanobis distance methods. Each cell shows the AUROC score when one of the five MATH domains is used as the in-distribution (ID) data and the remaining four are used as the out-of-distribution (OOD) data. The table is structured as a 5x5 matrix, with each row representing an ID domain and each column representing an OOD domain. Darker colors indicate higher AUROC scores, showing better performance of the method in distinguishing between ID and OOD data. The table helps demonstrate the limitations of static embedding methods for out-of-distribution detection in mathematical reasoning.

read the caption

Table 5: AUROC score matrix produced after alternating the MATH dataset's five domains as ID and OOD data measured by (a) Input Embedding Mahalanobis Distance and (b) Output Embedding (w/ CoT) Mahalanobis Distance. Darker colors represent better performances.

🔼 This table presents the results of the offline detection experiments. It shows the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) and the False Positive Rate at 95% True Positive Rate (FPR95) for different OOD detection methods, including the proposed TV Score and several baselines. The results are broken down by model (Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL) and OOD scenario (far-shift and near-shift). Underlined values indicate the best performance among baseline methods, and bold values show the best overall performance.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

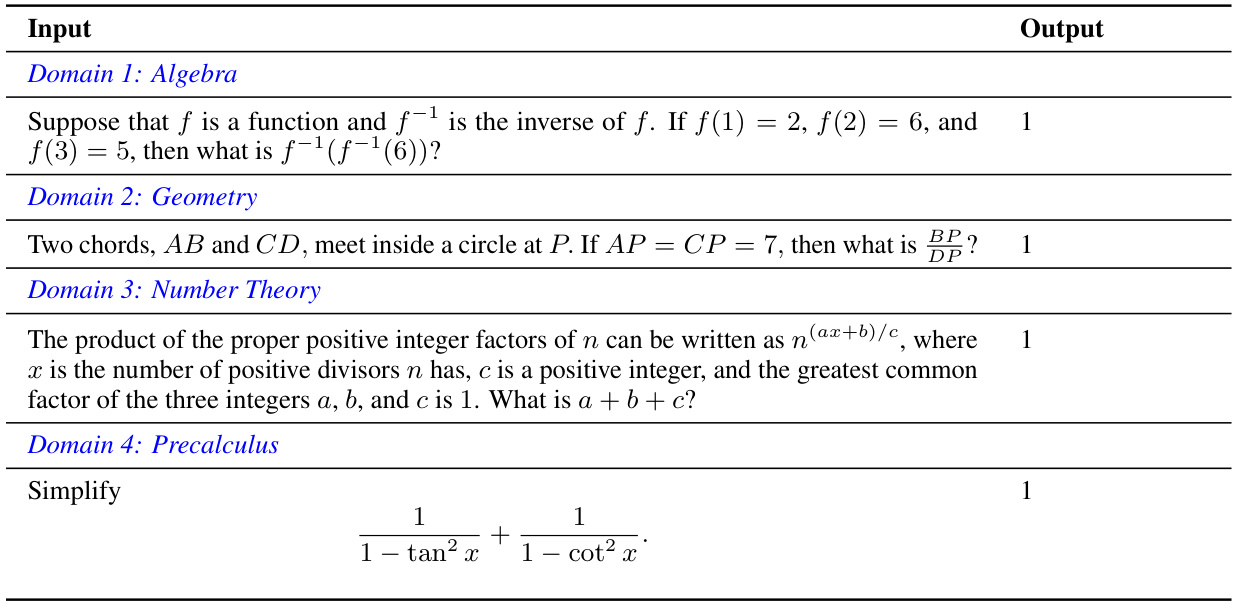

🔼 This table shows four examples of input-output pairs from different mathematical domains (Algebra, Geometry, Number Theory, and Precalculus). Each row represents a different domain, showing the input question and the correct numerical output. The examples highlight the fact that different domains can lead to the same numerical output, which is a challenge for existing methods based on comparing embedding distances.

read the caption

Table 7: Examples of inputs/outputs from different domains in the mathematical reasoning scenario.

🔼 This table presents the results of the offline OOD detection experiment. It compares the performance of the proposed TV Score method against five baselines (Maximum Softmax Probability, Monte-Carlo Dropout, Sequence Perplexity, Input Embedding, and Output Embedding) across two OOD scenarios (far-shift and near-shift). The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) and False Positive Rate at 95% True Positive Rate (FPR95) metrics are reported for each method and scenario. The table highlights the best-performing method (SOTA) for each metric and scenario.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

🔼 This table presents the AUROC and FPR95 scores for various offline OOD detection methods under two scenarios: far-shift OOD and near-shift OOD. The results are shown for the Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL models, comparing the proposed TV Score method against several baselines. The table highlights the best-performing methods for each metric and dataset, demonstrating the effectiveness of the TV Score method, particularly in near-shift OOD scenarios. Detailed results for individual datasets are available in Appendix F.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

🔼 This table presents the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) and the False Positive Rate at 95% True Positive Rate (FPR95) for different offline OOD detection methods. The results are shown for both far-shift and near-shift OOD scenarios, using two different language models (Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL). The table highlights the best-performing methods (SOTA) among all baseline methods and all methods.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

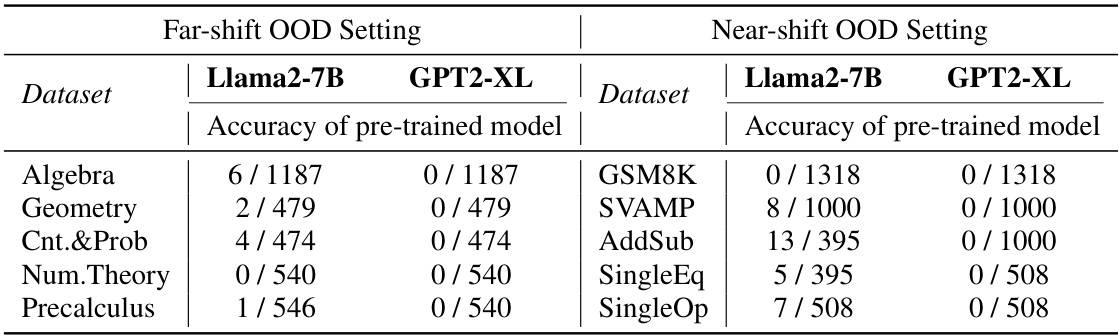

🔼 This table presents the accuracy of pre-trained Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL models on various datasets used as out-of-distribution (OOD) data. It shows the number of correctly classified samples out of the total number of samples for each dataset in both far-shift and near-shift OOD scenarios. The results indicate the baseline performance of the GLMs and illustrate the difficulty of the OOD detection tasks.

read the caption

Table 10: Accuracies of all datasets we select as the OOD data in pre-trained GLMs.

🔼 This table presents the results of offline OOD detection experiments using two different large language models (LLMs), Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL, on both far-shift and near-shift OOD scenarios. It compares the performance of the proposed Trajectory Volatility (TV) score method with five baseline methods across multiple metrics (AUROC and FPR95). The results are presented as averages across different datasets, showing the effectiveness of the TV score, especially in near-shift scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

🔼 This table presents the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) and False Positive Rate at 95% True Positive Rate (FPR95) for various offline OOD detection methods. Results are shown for both far-shift and near-shift OOD scenarios, comparing the proposed TV Score method with several baselines. The table highlights the best performing methods for both metrics in each scenario.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

🔼 This table presents the results of offline OOD detection experiments. It shows the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) and False Positive Rate at 95% True Positive Rate (FPR95) for different methods, including the proposed TV Score and several baselines. Results are shown for both far-shift and near-shift out-of-distribution (OOD) scenarios using two different language models (Llama2-7B and GPT2-XL). Detailed results for each individual dataset can be found in Appendix F.

read the caption

Table 1: AUROC and FPR95 results of the Offline Detection scenario. Underline and bold denote SOTA among all baselines and all methods, respectively. We report the average results under each setting in the main text, results of each dataset are shown in Table 11 and 12 (Appendix F).

🔼 This table presents the results of the OOD quality estimation experiment, comparing different methods’ Kendall’s Tau and Spearman’s correlation coefficients against a binary matching benchmark. It shows the correlation between each OOD detection method’s score and the accuracy of the model’s generated answer (whether it matches the correct answer). The table is divided into far-shift and near-shift OOD settings and shows the average correlation for each method across multiple datasets.

read the caption

Table 3: OOD Quality Estimation: Kendall's T and Spearman correlation between various OOD scores and benchmark quality metric binary matching. Each column shows the correlation when ID and OOD samples are merged. Underline denotes the SOTA among all baselines, and bold denotes the SOTA among our methods.

Full paper#