↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The experts problem, crucial in online learning, becomes challenging in distributed settings where expert costs must be aggregated across multiple servers. Existing solutions often suffer from high communication overhead, hindering scalability. This necessitates efficient protocols that minimize communication while maintaining near-optimal prediction accuracy.

This research introduces novel communication-efficient protocols that achieve near-optimal regret even against strong adversaries. The protocols are validated both theoretically, with a conditional lower bound, and empirically, showcasing significant communication savings on real-world benchmarks (HPO-B). This contribution offers a practical and theoretically sound approach to solving the distributed experts problem, thereby enhancing the scalability and efficiency of online learning in large-scale systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in distributed online learning and optimization. It offers communication-efficient protocols that achieve near-optimal regret in various settings, addressing a key challenge in big data environments. The conditional lower bound provides theoretical guarantees, while the empirical results on real-world benchmarks demonstrate practical benefits. This work paves the way for more efficient algorithms in distributed systems.

Visual Insights#

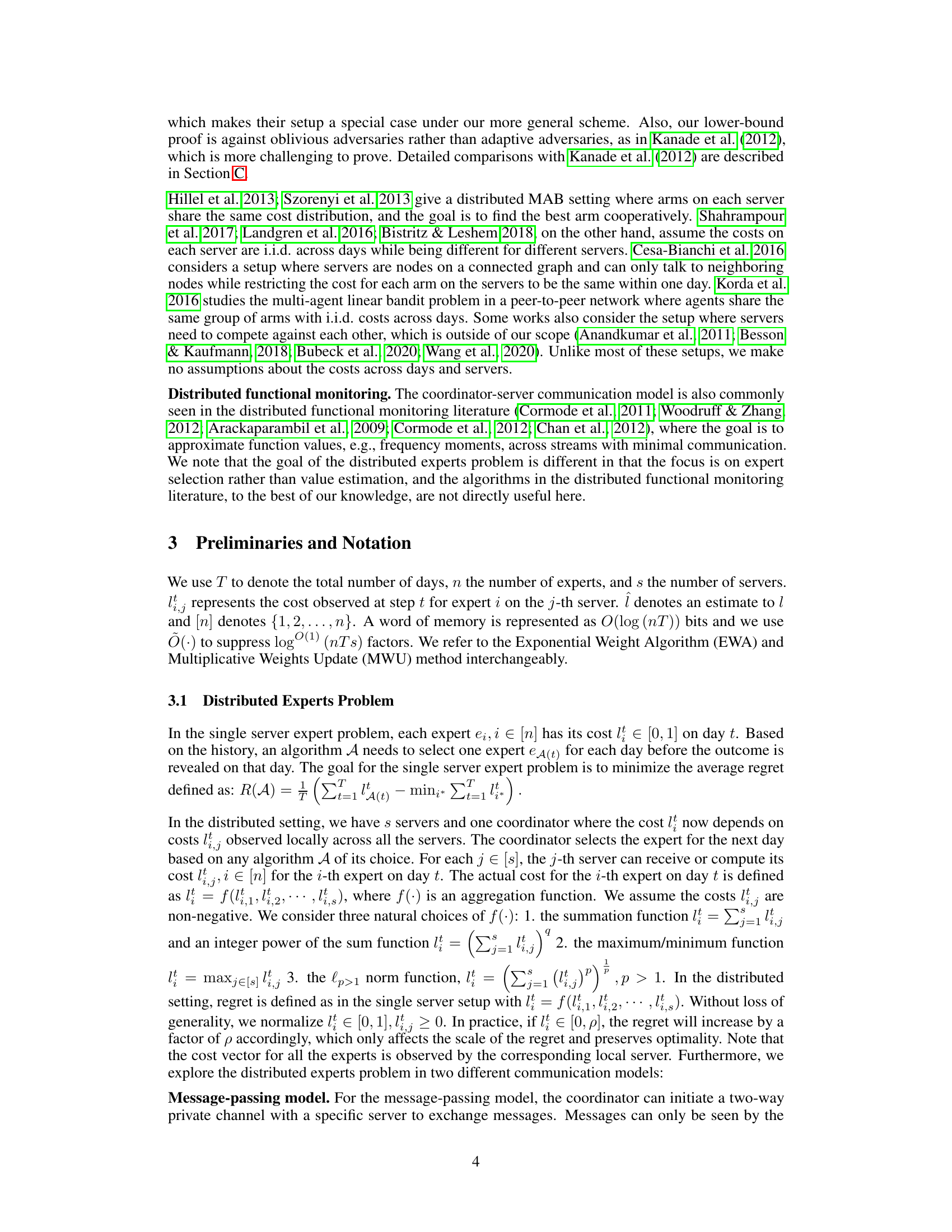

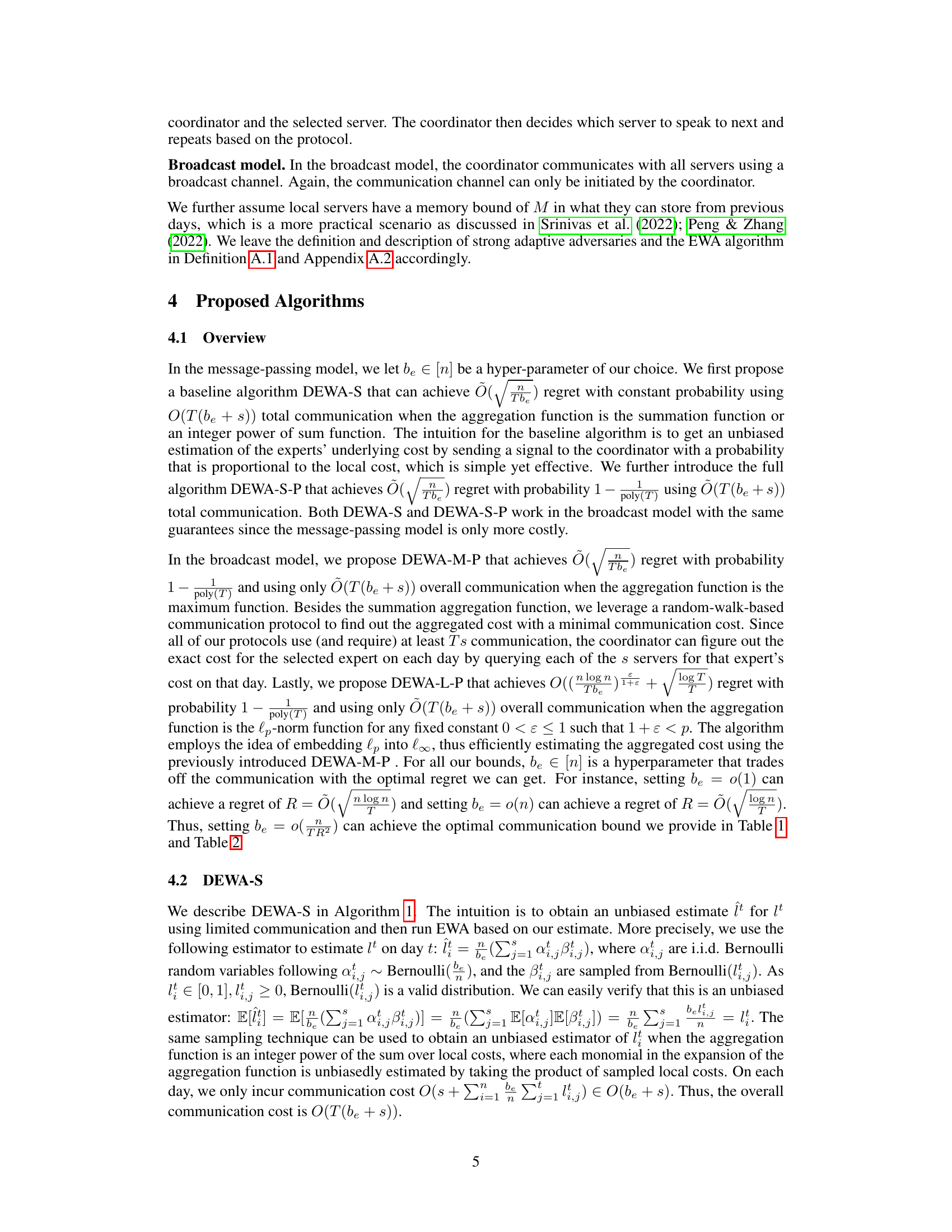

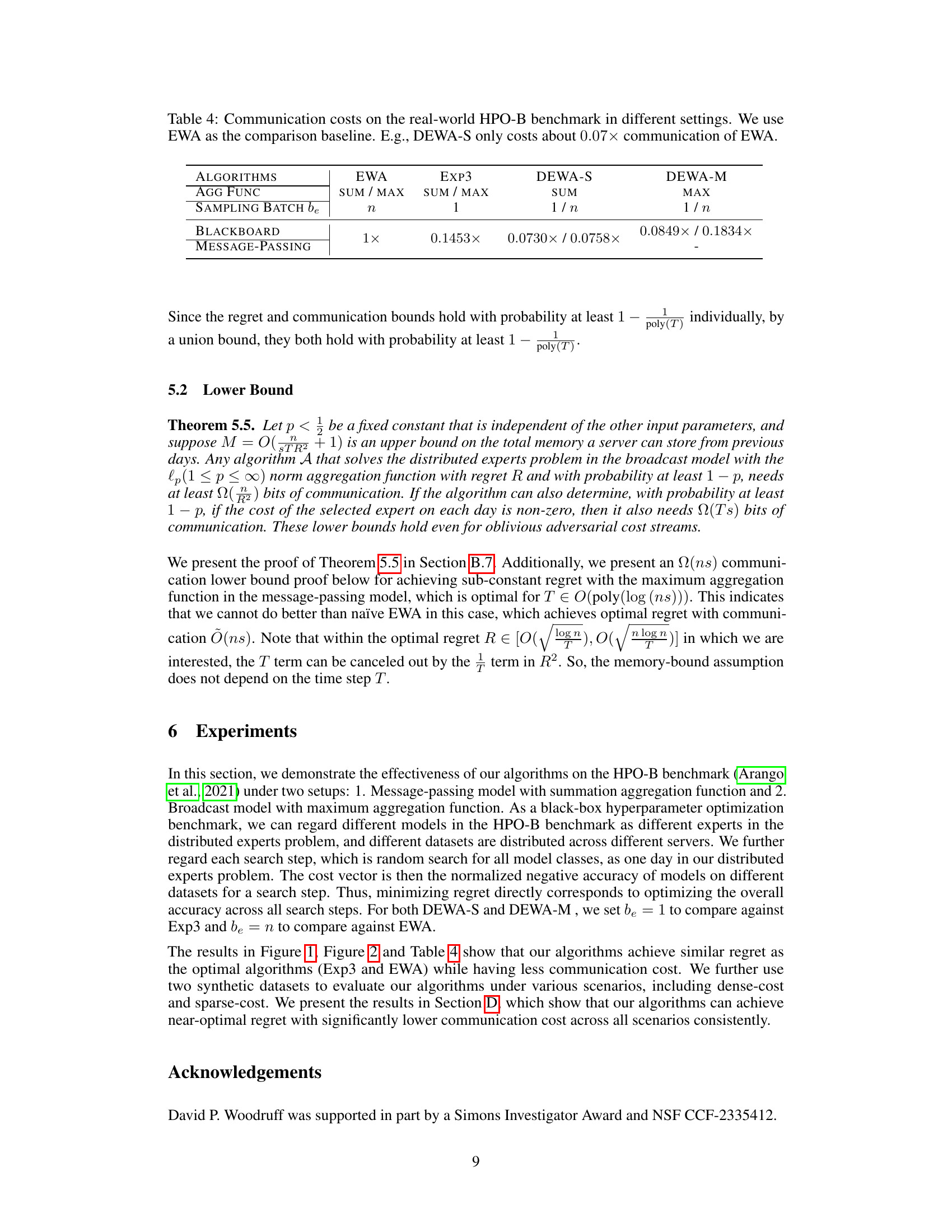

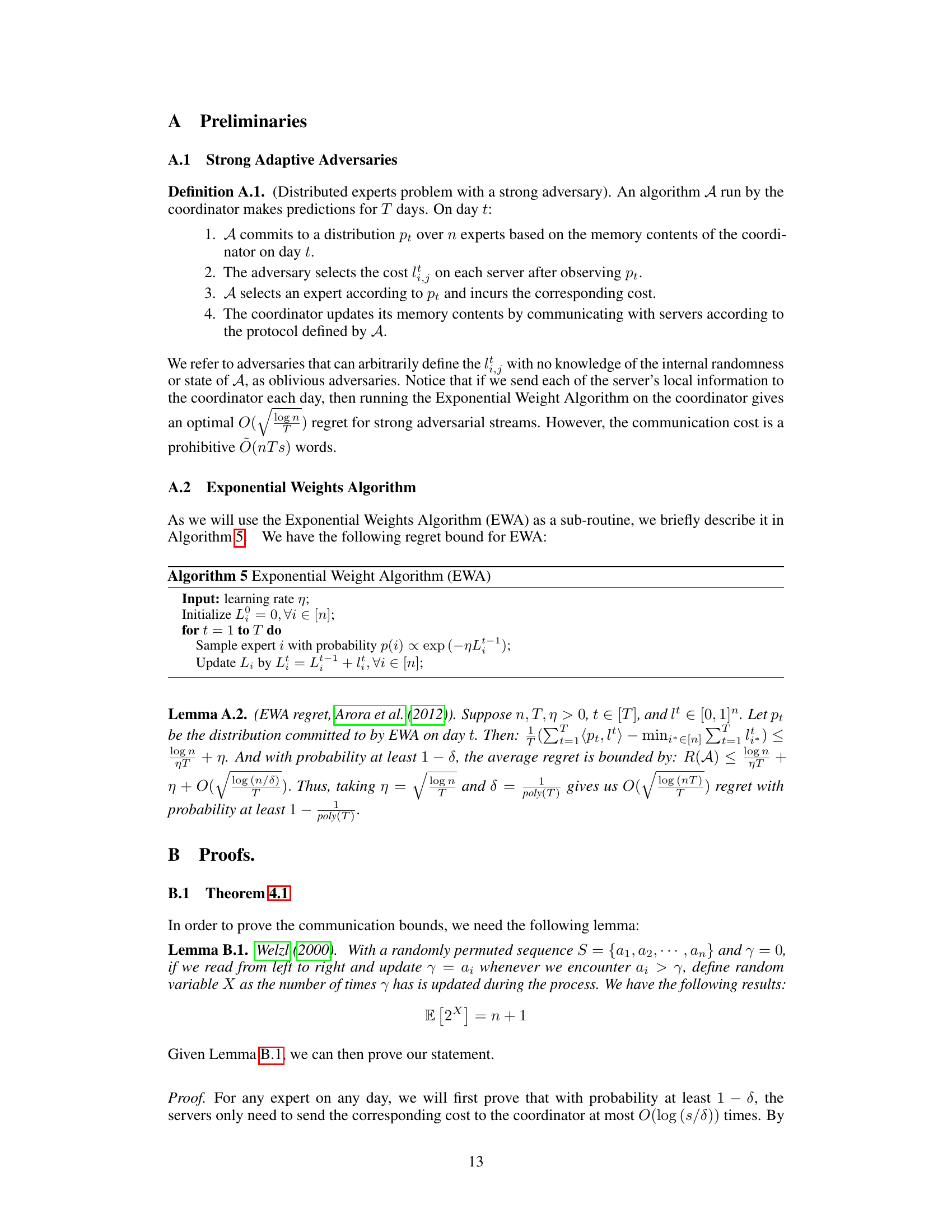

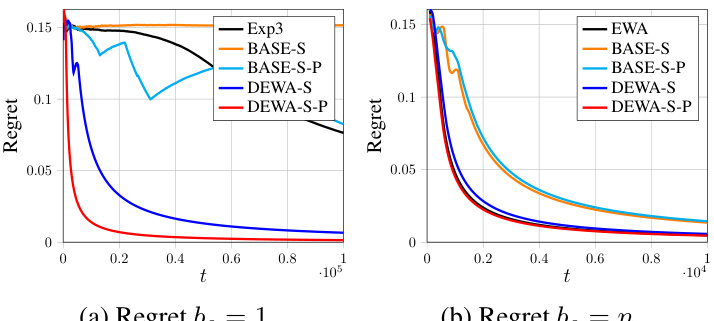

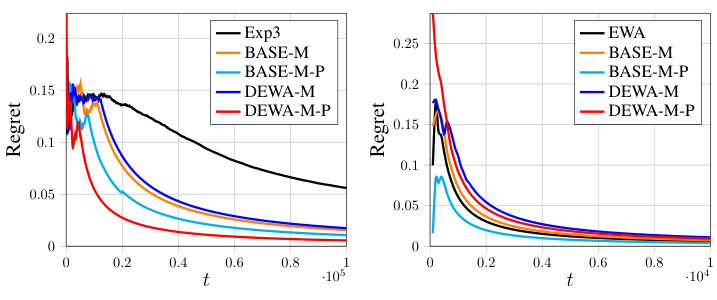

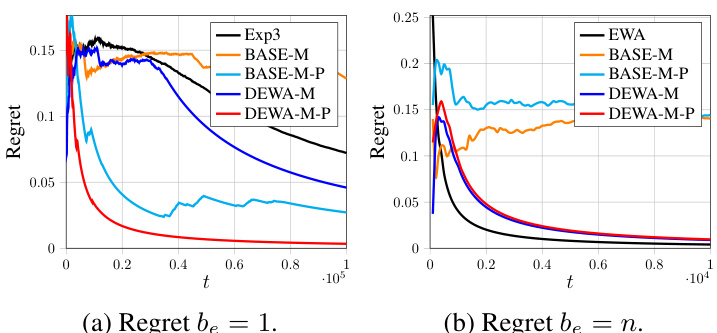

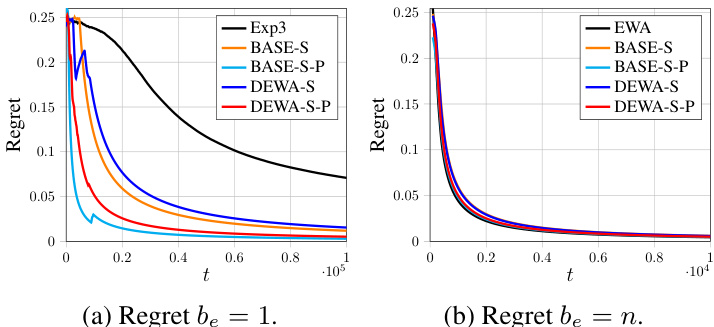

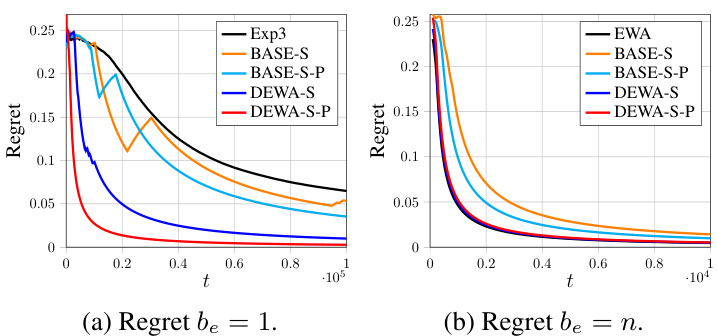

This figure shows the regrets of different algorithms (Exp3, EWA, DEWA-S, DEWA-M) on the HPO-B benchmark with sum aggregation. Subfigures (a) and (b) show the results for different sampling budgets, be = 1 and be = n, respectively. The x-axis represents the time step (t), and the y-axis represents the regret. The figure illustrates the performance of the proposed DEWA algorithms in comparison to existing algorithms.

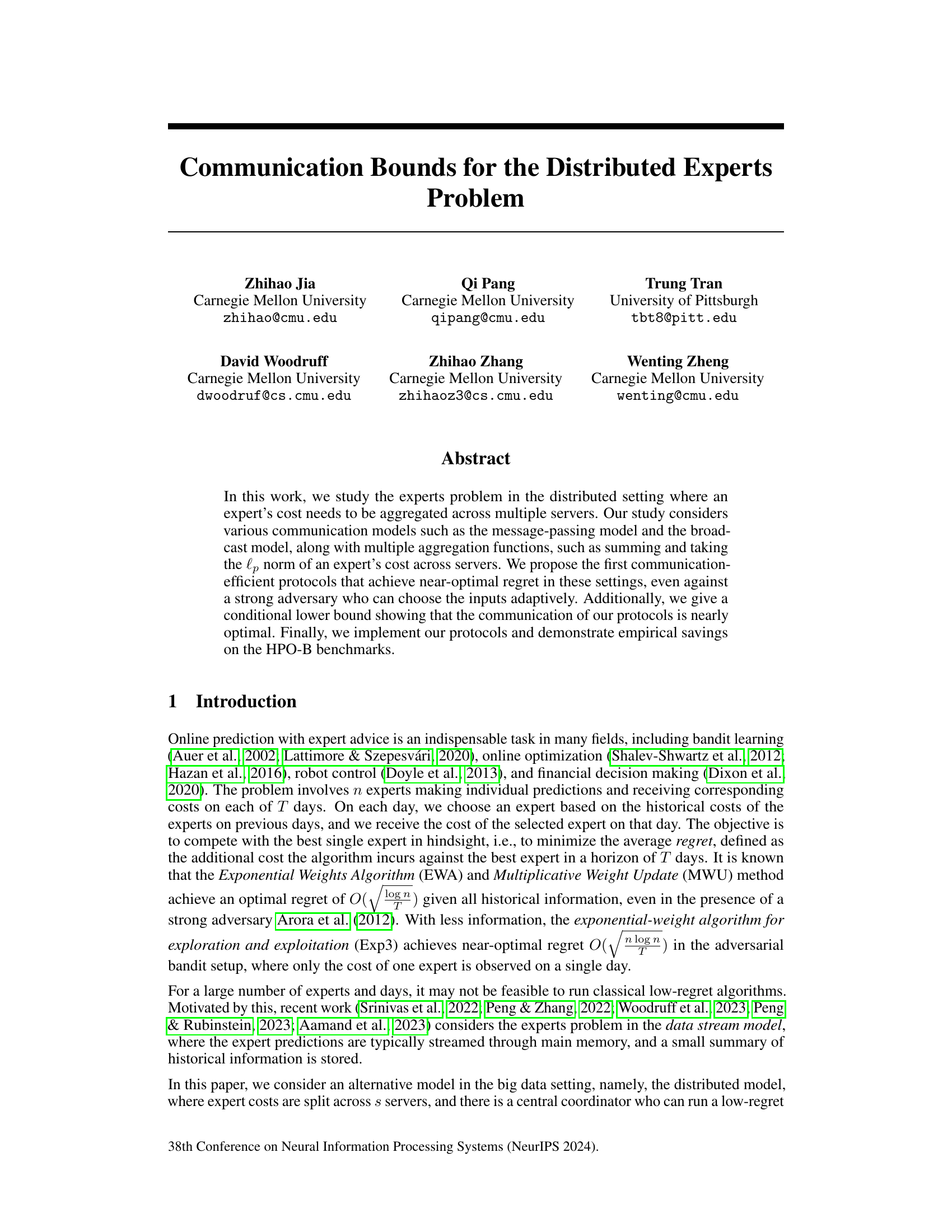

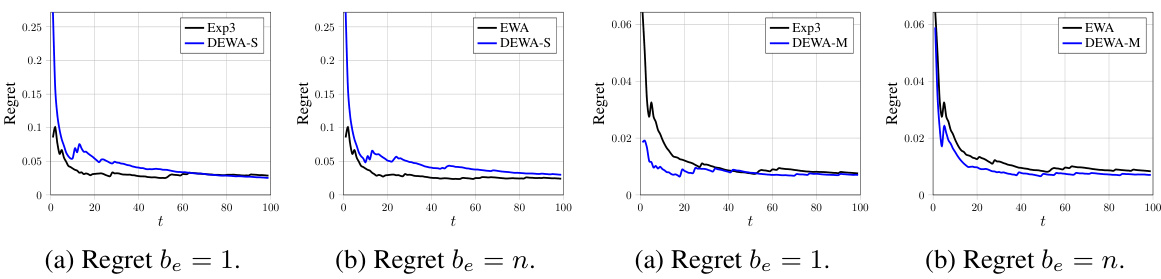

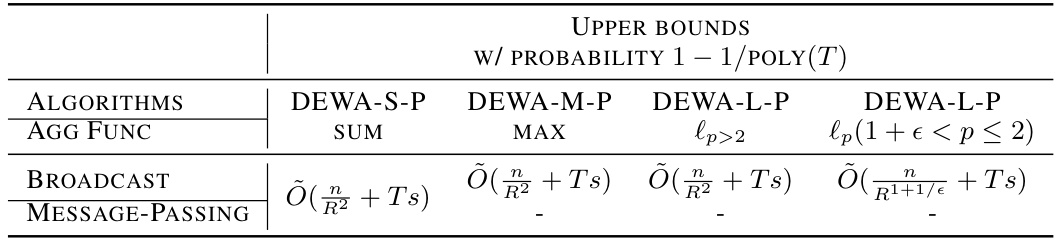

This table presents the upper bounds on communication complexity for different algorithms (DEWA-S, DEWA-M, DEWA-L) under two communication models (broadcast and message-passing) with a constant probability of success. The algorithms are designed for different aggregation functions (sum, max, lp-norm). The upper bounds represent the communication cost in terms of the regret (R) and other problem parameters (T, s).

In-depth insights#

Regret vs. Communication#

The core challenge addressed in this research is to minimize the communication overhead while maintaining low regret in distributed online learning, specifically the distributed experts problem. The trade-off between communication cost and regret is central. The authors explore various communication models (message-passing, broadcast) and aggregation functions (sum, max, lp-norm), designing algorithms that achieve near-optimal regret while significantly reducing communication compared to existing methods like EWA. A key innovation is the development of communication-efficient protocols that achieve this balance, particularly in scenarios with strong adaptive adversaries. The theoretical results are substantiated with empirical evidence from both synthetic and real-world benchmarks, demonstrating the practical effectiveness of the proposed algorithms. The near-optimality of the proposed algorithms is established through conditional lower bounds, highlighting the efficiency gains achieved. The work effectively navigates the complexity of distributed settings, offering valuable insights and practical protocols for optimizing this challenging trade-off.

Adaptive Adversaries#

The concept of “Adaptive Adversaries” in a machine learning context, particularly within online learning settings like the distributed experts problem, is crucial. Adaptive adversaries represent a more challenging scenario than oblivious adversaries. Unlike oblivious adversaries whose actions are predetermined, adaptive adversaries can dynamically adjust their strategies based on the algorithm’s previous actions and observed data. This adaptability makes achieving low regret significantly harder, requiring algorithms to be more robust and less predictable. Dealing with adaptive adversaries necessitates algorithms that exhibit strong generalization capabilities and are less susceptible to overfitting on past data. The design and analysis of algorithms that successfully manage the challenges posed by adaptive adversaries are key contributions of research in this field. Successfully achieving near-optimal regret against adaptive adversaries showcases the robustness and adaptability of the proposed protocols. Future research could explore alternative adversary models or investigate the impact of various adaptive strategies on algorithm performance.

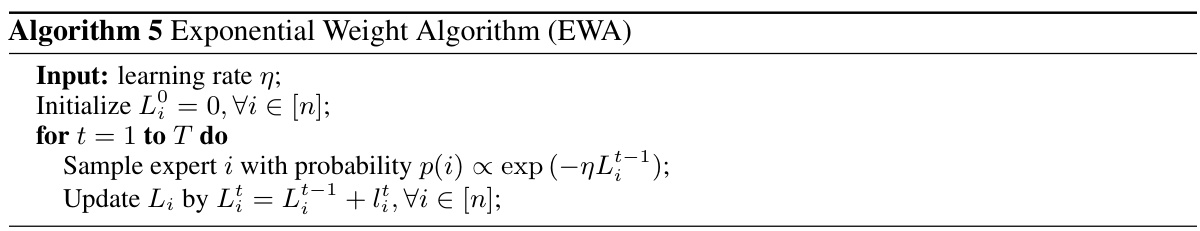

Distributed EWA#

A hypothetical “Distributed EWA” heading suggests a research focus on adapting the Exponential Weighted Average (EWA) algorithm for distributed computing environments. This would likely involve strategies for efficient communication and aggregation of data across multiple machines to maintain the algorithm’s low-regret properties. Challenges would include handling communication delays and bandwidth limitations, ensuring consensus among distributed agents, and managing potential data inconsistencies. The work might compare different communication models (message-passing, broadcast), exploring trade-offs between communication costs and algorithm performance. A successful approach could significantly improve the scalability of EWA for large-scale online learning problems such as those involving large datasets or complex models, opening new possibilities for real-world applications. The research could further focus on proving theoretical guarantees on regret bounds in this distributed setting. Key considerations would also be the computational complexity of the distributed implementation and its effect on convergence speed and overall efficiency. Overall, a successful “Distributed EWA” approach would represent a substantial contribution to both the theory and practice of online learning in distributed settings.

Communication Bounds#

The study of communication bounds in distributed systems is crucial for optimizing performance and resource utilization. Efficient algorithms need to minimize the amount of communication required to achieve a desired level of accuracy or performance. The paper likely explores various communication models (e.g., message-passing, broadcast) and aggregation functions (e.g., sum, max, lp-norm) to analyze the tradeoffs between communication cost and other metrics, such as regret in online learning scenarios. A key aspect of this analysis is likely the development of communication-efficient protocols that provide near-optimal performance in the context of the chosen communication model and aggregation function. Furthermore, the paper probably establishes conditional lower bounds to demonstrate the near-optimality of the proposed protocols. These bounds highlight the inherent limitations in communication efficiency for specific problem settings. In essence, by analyzing communication bounds, the paper aims to provide valuable insights into designing efficient distributed systems and algorithms, allowing for optimal resource allocation and reduced overhead.

HPO-B Experiments#

The HPO-B experiments section would likely detail the empirical evaluation of the proposed distributed experts algorithms. The authors would probably compare their methods against established baselines like EWA and Exp3. Key metrics would include regret and communication cost, measuring the performance across various settings. The experiments might involve both synthetic datasets (to control parameters and analyze performance under ideal conditions) and real-world datasets like HPO-B. The choice of HPO-B is crucial, implying the applicability of the algorithms to hyperparameter optimization. The results would showcase the efficiency gains from reduced communication, likely showing near-optimal regret while drastically reducing communication overhead compared to the baselines. The experiments would potentially analyze performance with respect to various factors such as the number of experts, the number of servers, and data sparsity. Visualizations such as plots of regret over time and communication costs would be used to present results clearly.

More visual insights#

More on figures

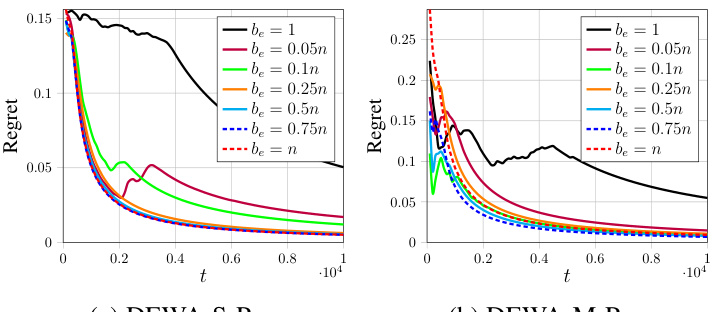

This figure shows the regret of DEWA-S-P and DEWA-M-P algorithms with different sampling budgets (be) under Gaussian distribution for non-sparse scenario. The x-axis represents the time step (t), and the y-axis represents the regret. Different lines represent different values of be ranging from 1 to n. The figure illustrates the impact of the sampling budget on the algorithms’ performance, showcasing how a larger be leads to faster convergence but may increase communication cost.

This figure shows the regret of DEWA-S-P and DEWA-M-P algorithms under different sampling budgets (be). The non-sparse scenario is considered, where the costs are not concentrated on a few servers. The results show that increasing the sampling budget leads to faster convergence of the regret to zero, with larger be values resulting in lower regret. The plot compares the performance against baselines (Exp3 and EWA) to demonstrate the algorithms’ effectiveness. The left panel is for the DEWA-S-P algorithm and the right panel is for the DEWA-M-P algorithm.

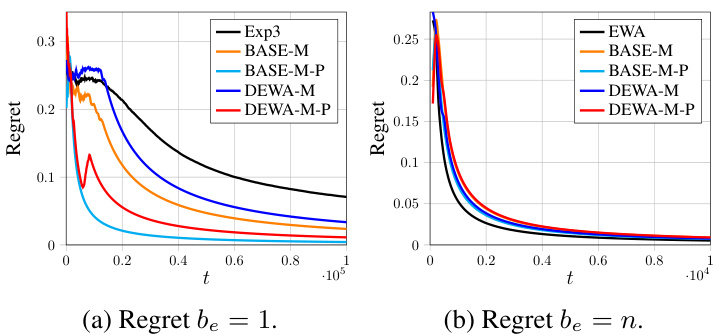

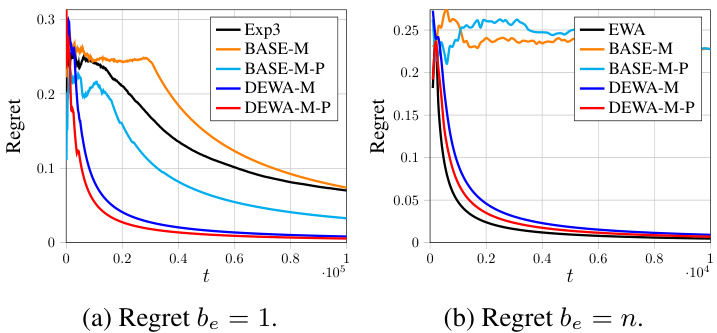

This figure shows the comparison of regrets for different algorithms on the HPO-B benchmark using the sum aggregation function. The x-axis represents the time step (t), and the y-axis represents the regret. Multiple lines represent different algorithms: Exp3, EWA, DEWA-S, DEWA-S-P, DEWA-M, and DEWA-M-P. The plots show the average regret and the variance over multiple runs of the algorithms. The sampling budget (be) is varied between 1 and n (the total number of experts) in separate plots to demonstrate how this parameter affects the regret.

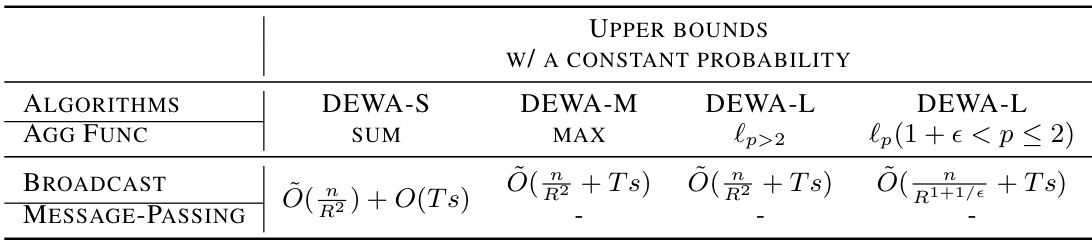

This figure shows the regret (vertical axis) over time (horizontal axis) for different algorithms using the Gaussian distribution with summation aggregation and a non-sparse scenario. The algorithms shown are Exp3, BASE-S, BASE-S-P, DEWA-S, DEWA-S-P, EWA, with sampling budget, be, set to 1 for (a) and n for (b). It illustrates the performance comparison of different algorithms, showing the convergence of regret towards zero as time progresses, highlighting the effectiveness of DEWA-S and DEWA-S-P in achieving low regret.

The figure shows the regrets of different algorithms (Exp3, BASE-S, BASE-S-P, DEWA-S, DEWA-S-P, EWA) on Gaussian distribution with summation aggregation in a non-sparse setting. The left subplot shows the results when the sampling budget be is 1 and the right subplot shows the results when be is n. The plots illustrate the average regret over time, showing how the different algorithms perform in minimizing cumulative cost.

This figure shows the regret results for the Gaussian distribution in a non-sparse scenario under different sampling budget be. It shows that the regret converges faster with a larger be and a reasonably large value (0.25n) is sufficient to achieve good regret. The plots compare DEWA-S-P and DEWA-M-P with Exp3 and EWA as baselines. The x-axis represents the number of days t, and the y-axis represents the regret.

The figure shows the regrets of DEWA-S and DEWA-S-P with summation aggregation function in a non-sparse setting. The results are compared to those of EWA (when the sampling budget be = n) and Exp3 (when be = 1). The plots show that DEWA-S and DEWA-S-P achieve regrets comparable to EWA (when be = n) and significantly better than Exp3 (when be = 1). The regrets converge to 0 with increasing time (t).

This figure compares the regret of DEWA-S-P and DEWA-M-P algorithms with different sampling budgets (be) against Exp3 and EWA baselines for Gaussian distribution cost in a non-sparse setting. The x-axis represents the time step (t), and the y-axis shows the regret. It demonstrates the impact of varying the hyperparameter be on the convergence of the algorithms; larger values of be generally lead to faster convergence but higher communication costs.

This figure shows the regret curves for DEWA-S-P and DEWA-M-P algorithms under different sampling budgets (be). The non-sparse scenario is considered. The x-axis represents the time step (t), and the y-axis represents the regret. Different lines represent different values of be ranging from 1 to n (the total number of experts). The results show that using a larger be leads to faster convergence of the regret to 0, but also increases the communication cost.

This figure compares the communication cost of DEWA-S-P and DEWA-M-P algorithms with different sampling budgets (be) in a non-sparse scenario. The communication cost is plotted against the sampling budget. EWA (Exponential Weighted Algorithm) serves as the baseline for comparison. The figure shows that the communication cost of DEWA-S-P increases linearly with be, while the cost of DEWA-M-P increases more gradually.

More on tables

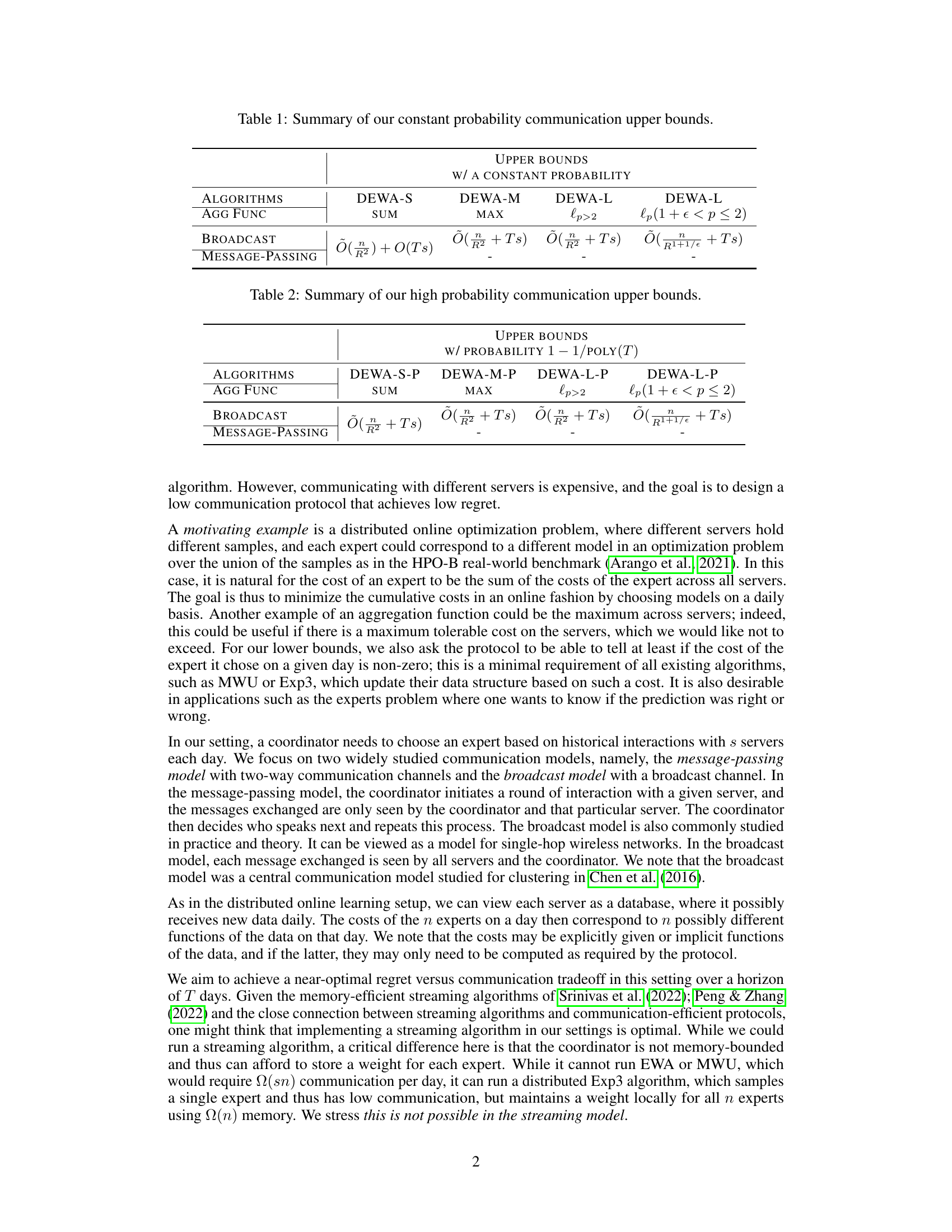

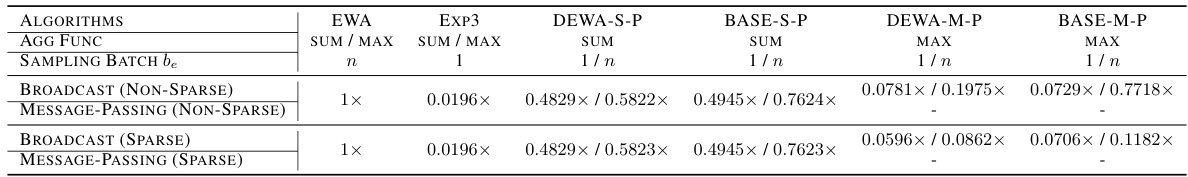

This table presents the upper bounds on communication complexity for several algorithms (DEWA-S-P, DEWA-M-P, DEWA-L-P) achieving near-optimal regret with high probability (1-1/poly(T)). The algorithms use different aggregation functions (SUM, MAX, lp-norm) and communication models (BROADCAST, MESSAGE-PASSING). The bounds show the communication cost in terms of the parameters n (number of experts), T (number of days), s (number of servers), R (regret bound), and ε (a small constant).

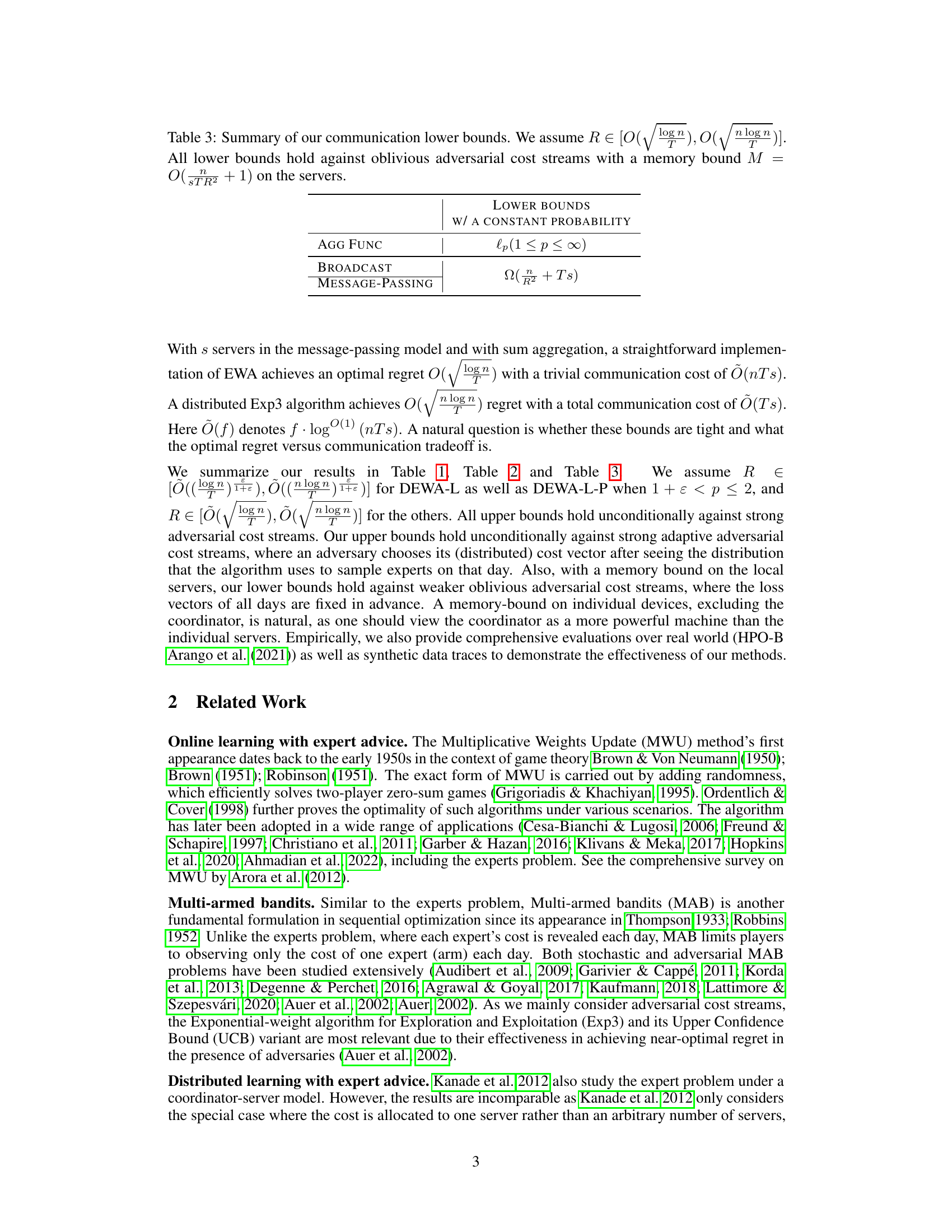

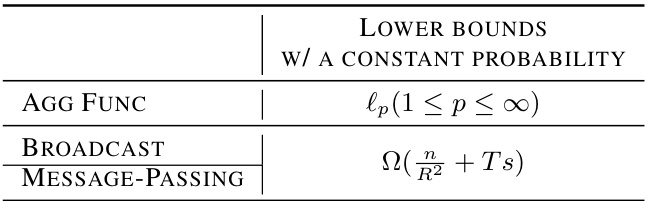

This table presents the lower bounds on communication complexity for achieving a certain regret (R) in the distributed experts problem, considering both broadcast and message-passing communication models. The lower bounds hold for various aggregation functions (lp norm, where 1 ≤ p ≤ ∞) and against oblivious adversaries with a memory constraint (M) on the servers. The table highlights the dependency of these lower bounds on the parameters R, T, s, and n.

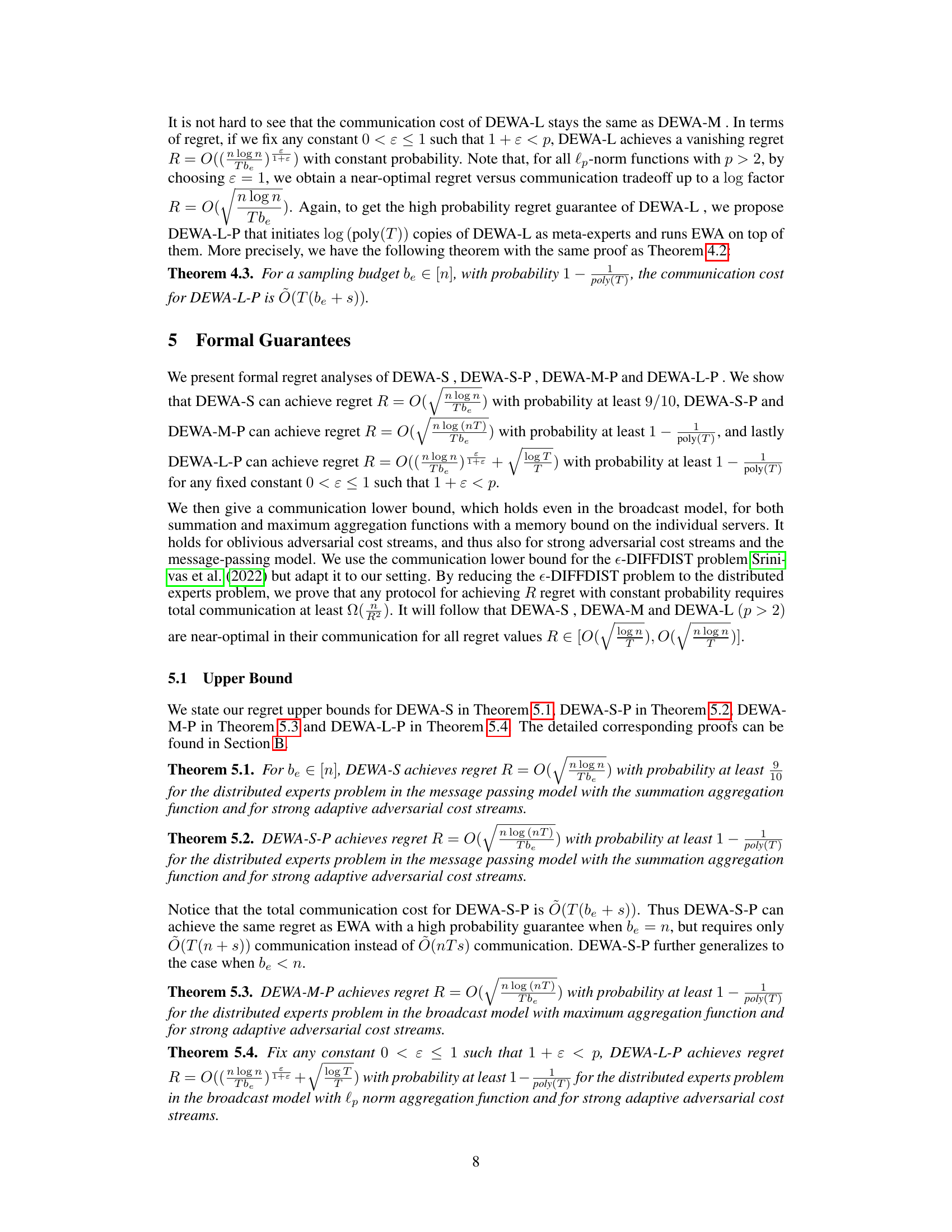

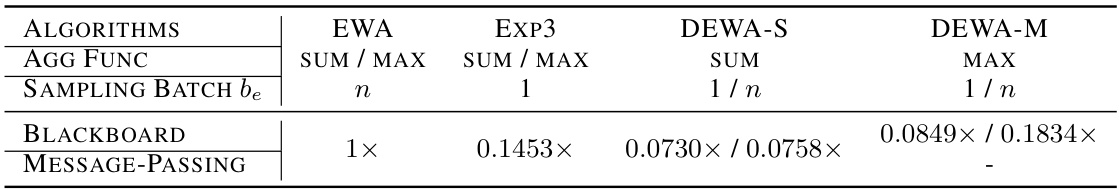

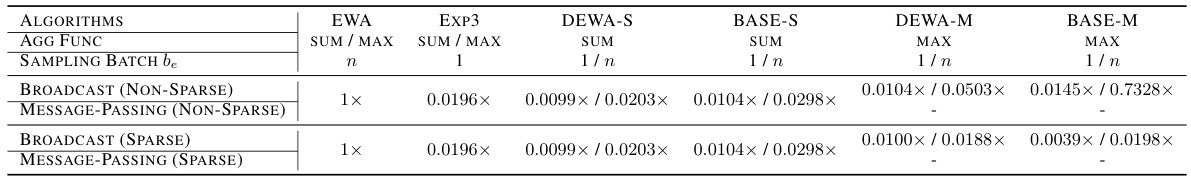

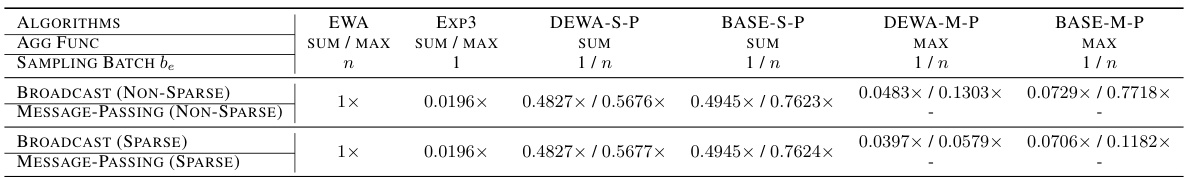

This table presents the communication costs observed when applying different algorithms (EWA, Exp3, DEWA-S, DEWA-M) to the HPO-B benchmark dataset. The communication costs are expressed relative to the cost of using the EWA algorithm. The table shows the cost for both the broadcast and message-passing communication models, and for different aggregation functions (sum and max), and for various sampling batch sizes. The results demonstrate the communication efficiency gains achieved by the DEWA algorithms compared to the baselines.

This table compares the communication costs of different algorithms (EWA, Exp3, DEWA-S, DEWA-M) on the HPO-B benchmark dataset for both blackboard and message-passing communication models. It shows the relative communication cost compared to EWA, indicating the efficiency gains of the proposed DEWA algorithms.

This table presents the communication costs of different algorithms (EWA, Exp3, DEWA-S, DEWA-M) on the real-world HPO-B benchmark dataset for hyperparameter optimization. It compares the communication costs of the proposed algorithms (DEWA-S and DEWA-M) against the baseline methods (EWA and Exp3) under different settings (broadcast, message-passing) and aggregation functions (sum, max). The results demonstrate that the proposed algorithms significantly reduce communication costs compared to the baselines.

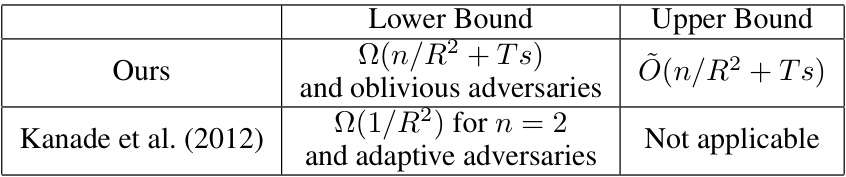

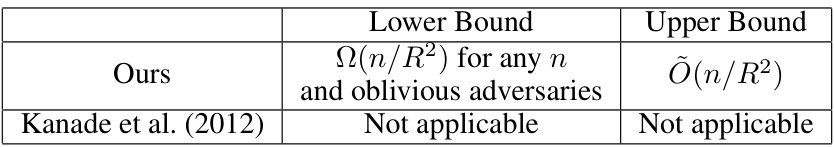

This table compares the lower and upper bounds of communication costs between our work and Kanade et al. (2012)’s work. The comparison considers two different types of adversaries: oblivious adversaries and adaptive adversaries. It also specifies whether only the coordinator or both the coordinator and servers can initiate the communication channel.

This table compares the lower and upper bounds of communication costs for the distributed experts problem in the message-passing model, where either the coordinator or servers can initiate the communication. It shows that our proposed algorithms achieve near-optimal communication complexity compared to the existing work by Kanade et al. (2012), particularly in the scenario with oblivious adversaries.

This table shows the communication costs of several algorithms (EWA, Exp3, DEWA-S, BASE-S, DEWA-M, BASE-M) for both non-sparse and sparse settings under Gaussian distribution. The communication costs are relative to EWA, which is set as the baseline (1x). The table provides a comparison across different aggregation functions (sum and max) and sampling batches. BASE-S and BASE-M are simplified versions of DEWA-S and DEWA-M, respectively. It demonstrates the efficiency of the proposed algorithms, particularly in sparse settings where significantly less communication is needed compared to EWA.

This table presents the communication costs of high-probability protocols (DEWA-S-P, BASE-S-P, DEWA-M-P, BASE-M-P) on Gaussian distribution for both non-sparse and sparse settings. The communication costs are compared to EWA (Exponential Weighted Average), which serves as the baseline and is denoted as 1x. The table shows the costs for different aggregation functions (SUM, MAX) and sampling batches (1/n, n), illustrating the communication efficiency of the proposed protocols under various scenarios. ‘Non-Sparse’ indicates a setting where the costs are distributed across all servers, while ‘Sparse’ suggests a scenario with costs concentrated on only a few servers.

This table presents the communication costs of various algorithms (EWA, Exp3, DEWA-S, BASE-S, DEWA-M, BASE-M) for both broadcast and message-passing models under non-sparse and sparse scenarios. The costs are normalized relative to EWA’s communication cost, offering a clear comparison of the communication efficiency of different algorithms.

This table presents the communication costs of high-probability protocols (DEWA-S-P, BASE-S-P, DEWA-M-P, BASE-M-P) on Gaussian distribution in different settings (Broadcast/Message-Passing, Non-sparse/Sparse). The costs are relative to EWA (baseline = 1x), showing the efficiency gains of the proposed methods. The sampling batch size (be) is varied (n, 1/n).

Full paper#