↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for training LLMs as agents struggle with the exponentially large action space and coarse credit assignment at the action level, leading to inefficient learning and poor generalization. These methods often rely on manually restricting the action space, limiting their applicability. The issue of misalignment between the agent’s knowledge and the environment’s dynamics further hinders performance.

This paper introduces Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD). POAD tackles these issues by decomposing the optimization process from the action level to the token level. This allows for much finer-grained credit assignment for each token within an action, significantly reducing optimization complexity and improving learning efficiency. The theoretical analysis and empirical results on various tasks confirm the effectiveness of POAD, showing significant improvements over existing methods. POAD demonstrates better generalization and performance, showcasing its potential for building more robust and versatile LLM agents.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) as intelligent agents. It directly addresses the challenges of inefficient optimization and limited generalization in interactive environments, offering a novel solution with significant performance improvements. The proposed method, POAD, provides a valuable framework for future research, opening avenues for enhancing LLM agent capabilities in complex, interactive scenarios.

Visual Insights#

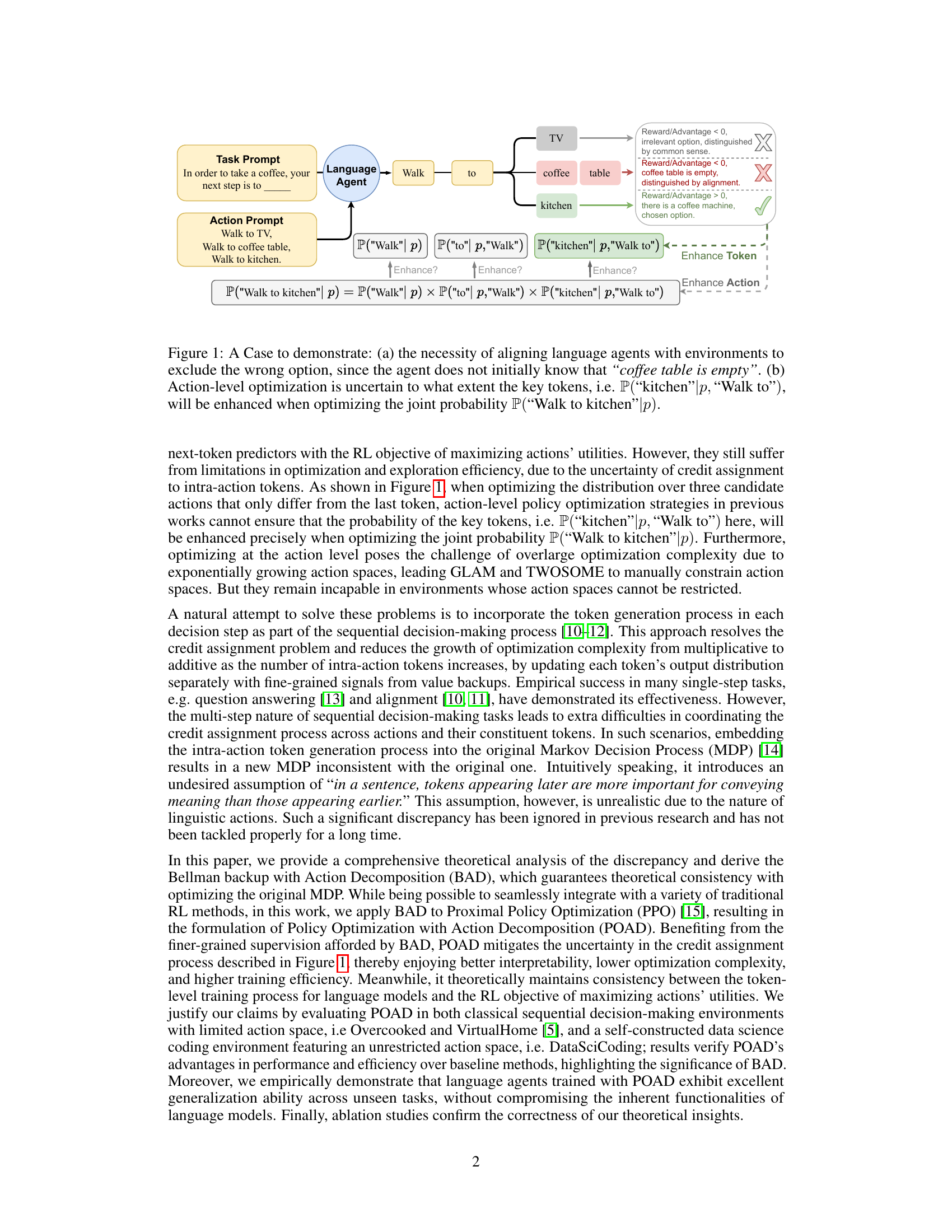

This figure demonstrates two key aspects. First, it showcases the importance of aligning language agents with their environments. The example shows that a language agent, lacking world knowledge, might suggest an incorrect action (walking to an empty coffee table). Second, it highlights a limitation of action-level optimization in reinforcement learning. This method struggles to precisely enhance the probability of crucial tokens within an action, leading to inefficient learning and exploration.

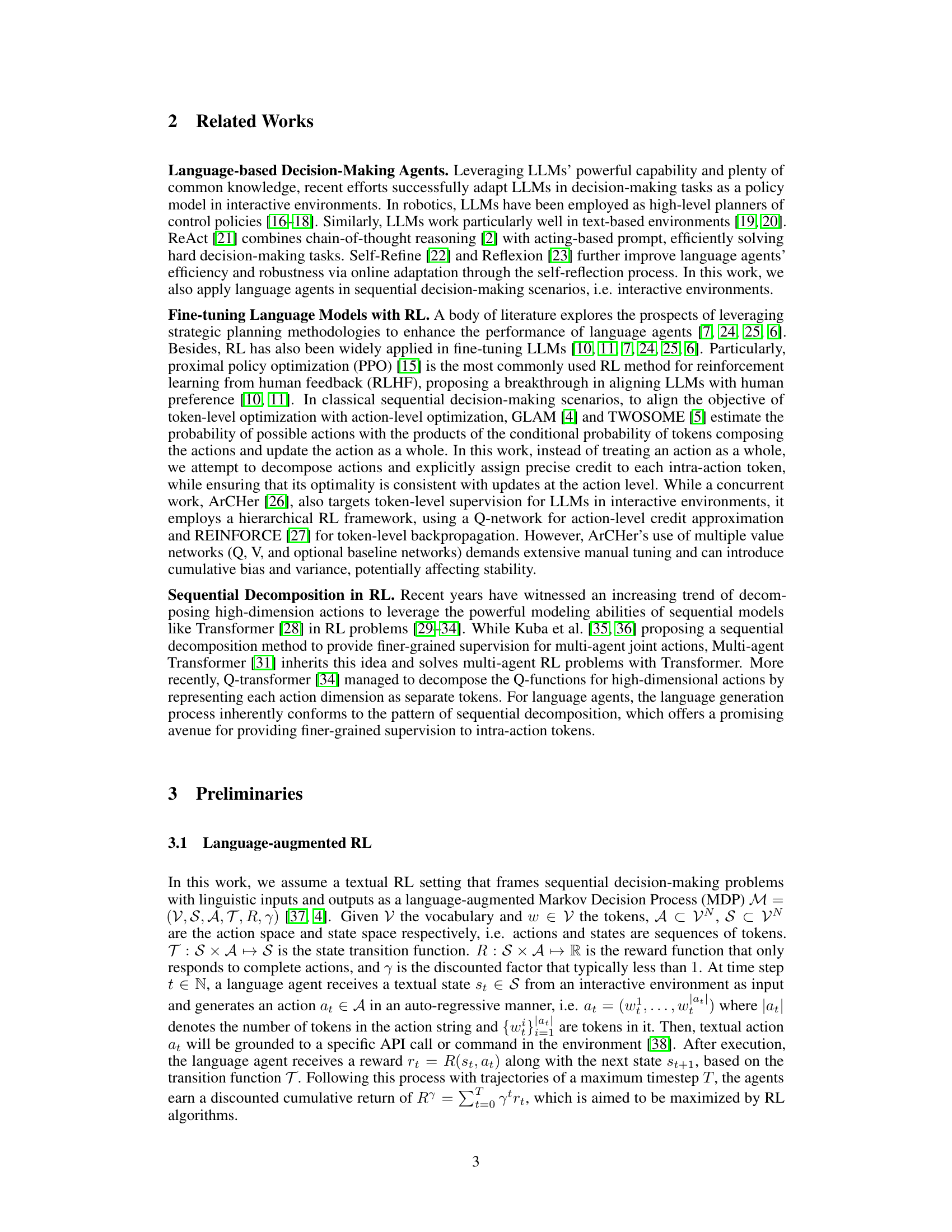

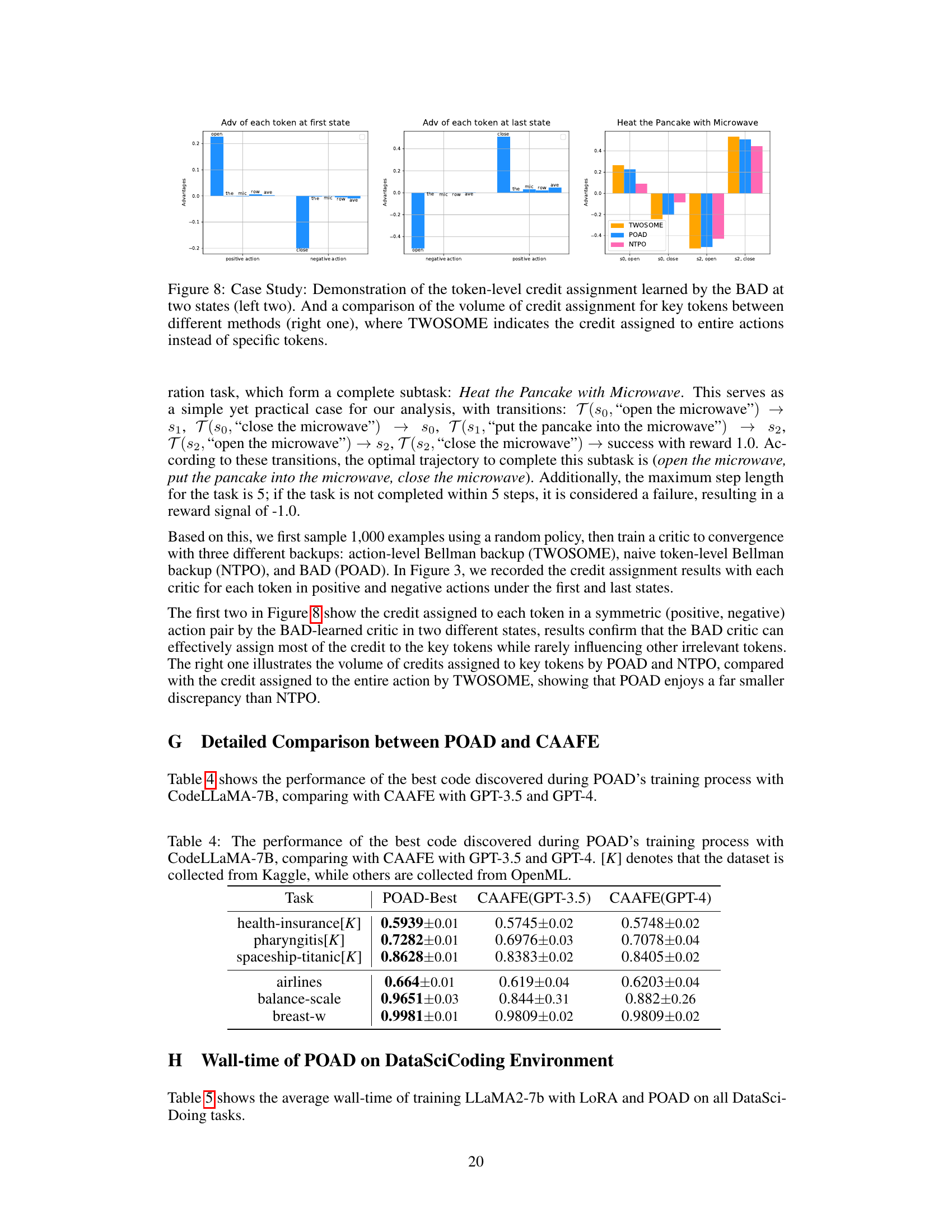

This table presents the generalization performance of different language agent training methods on eight unseen tasks. The tasks are variations of the Food Preparation task from the Overcooked environment, modifying the food items and appliances. The performance is measured by the average episodic return over 100 episodes, showing how well the agents can adapt to new, similar tasks after training.

In-depth insights#

LLM Agent RL#

LLM Agent RL represents a fascinating intersection of large language models (LLMs) and reinforcement learning (RL). LLMs bring their powerful text generation and reasoning capabilities, enabling agents to interact with environments in a more sophisticated way than traditional RL agents. However, the massive action space inherent in natural language presents a significant challenge. RL algorithms struggle with the scale and complexity, requiring innovative solutions such as action decomposition techniques. The combination demands careful credit assignment, as the success of a language action often hinges on the quality of its constituent tokens. Theoretical analysis is crucial to ensure the consistency between token-level optimization and the overall RL objective. Furthermore, the use of LLMs introduces new considerations around efficiency, generalization, and interpretability. Ultimately, LLM Agent RL pushes the boundaries of AI by enabling sophisticated natural language interaction within complex decision-making environments, though significant research remains focused on scaling to more complex and interactive tasks.

Action Decomposition#

Action decomposition, in the context of reinforcement learning for Large Language Models (LLMs), is a crucial technique for enhancing learning efficiency and generalization. By breaking down complex language actions into sequences of individual tokens, it enables finer-grained credit assignment, addressing the limitations of action-level optimization which often struggles with assigning credit appropriately to individual token contributions within an action. This token-level approach facilitates more precise supervision and backpropagation of reward signals, leading to improved learning. Further, decomposing actions mitigates the problem of exponentially large action spaces, which often hampers effective learning in traditional methods. The theoretical analysis of the discrepancies between action-level and token-level optimization, as presented in this approach, underscores the importance of this method, demonstrating how it effectively integrates credit assignments for both intra- and inter-action tokens. Ultimately, this approach offers a more nuanced and efficient learning paradigm for LLMs acting as agents in complex interactive environments.

POAD Algorithm#

The core of this research paper revolves around the proposed POAD (Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition) algorithm. POAD enhances the training of LLM agents by decomposing the optimization process from the action level down to the token level. This granular approach offers finer-grained credit assignment for each token within an action, thereby mitigating the uncertainty inherent in action-level optimization methods. The theoretical foundation of POAD lies in the derived Bellman backup with Action Decomposition (BAD), which ensures consistency between the token and action-level optimization objectives. By addressing the discrepancies between action-level and naive token-level approaches, POAD significantly improves learning efficiency and generalization. Experimental results across diverse environments confirm that POAD outperforms existing methods, showcasing its effectiveness in aligning language agents with interactive environments, particularly those with unrestricted action spaces. The algorithm’s strength rests on its ability to handle high-dimensional action spaces more efficiently and provides better interpretability and enhanced performance.

Empirical Validation#

An Empirical Validation section in a research paper would rigorously test the proposed methodology. This would involve carefully designed experiments, likely across multiple datasets and settings to showcase generalizability. Key aspects would include a clear definition of metrics used for evaluation, such as precision, recall, F1-score, or AUC, along with a baseline comparison against existing approaches. The presentation of results would be crucial, visually representing findings with graphs and tables, and statistically analyzing the significance of any observed differences between the new method and the baseline. A robust empirical validation would also address potential limitations and edge cases, ideally including an ablation study to systematically evaluate the contribution of each component of the proposed method. Sufficient detail regarding experimental setup and parameter choices is vital for reproducibility, allowing other researchers to verify the findings. Ultimately, a strong empirical validation serves as compelling evidence supporting the claims made by the research paper, highlighting its practical value and reliability.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section could productively explore several avenues. Extending POAD’s applicability to a wider range of RL algorithms beyond PPO is crucial to demonstrate its general utility and robustness. Addressing the limitation of needing a quantitative reward function is key, perhaps by investigating techniques like self-rewarding or hindsight relabeling. Furthermore, a deeper investigation into the impact of action space size and token length on POAD’s performance would refine its theoretical understanding. Finally, assessing POAD’s efficiency and scalability on more complex, real-world problems with larger language models is essential to solidify its practical value, with particular attention to the potential computational costs.

More visual insights#

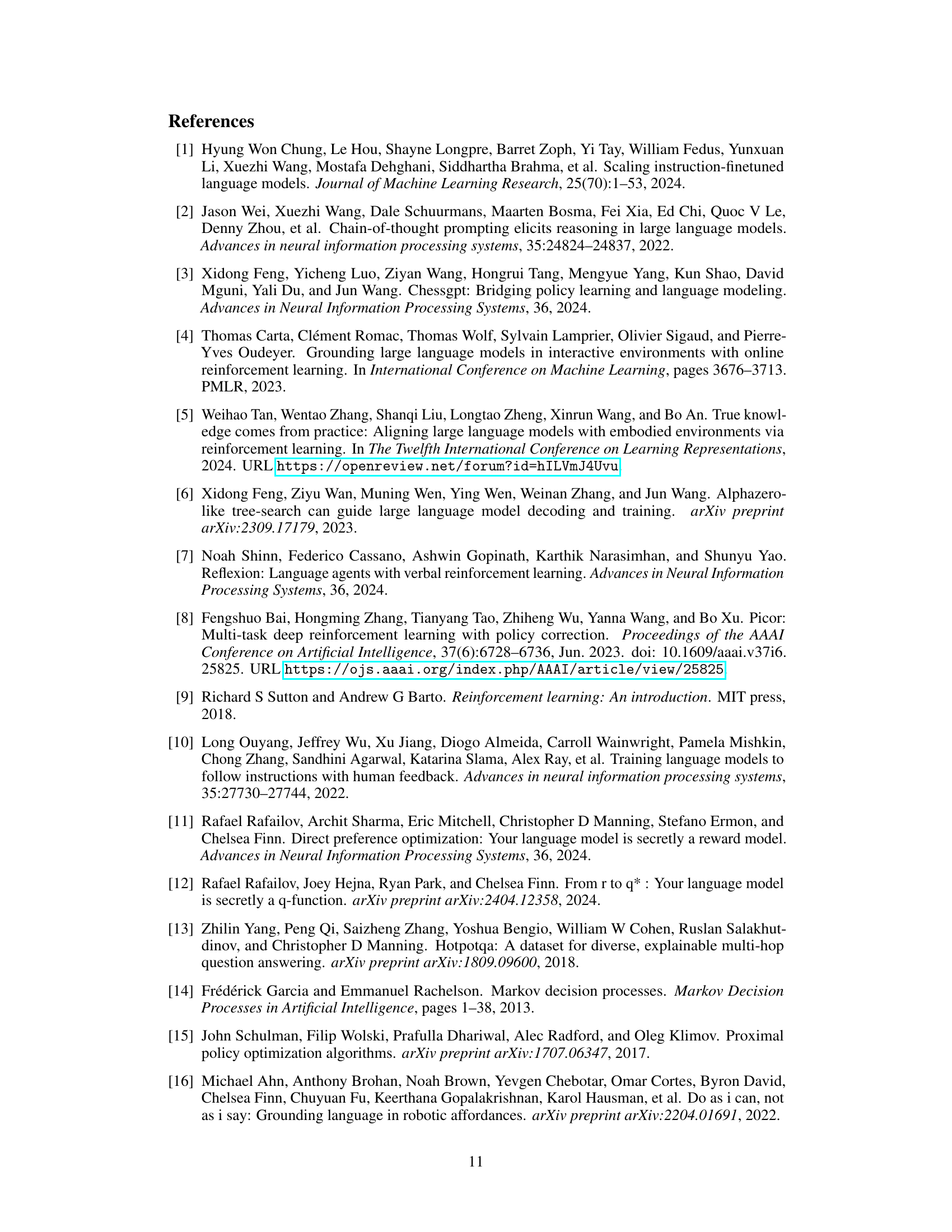

More on figures

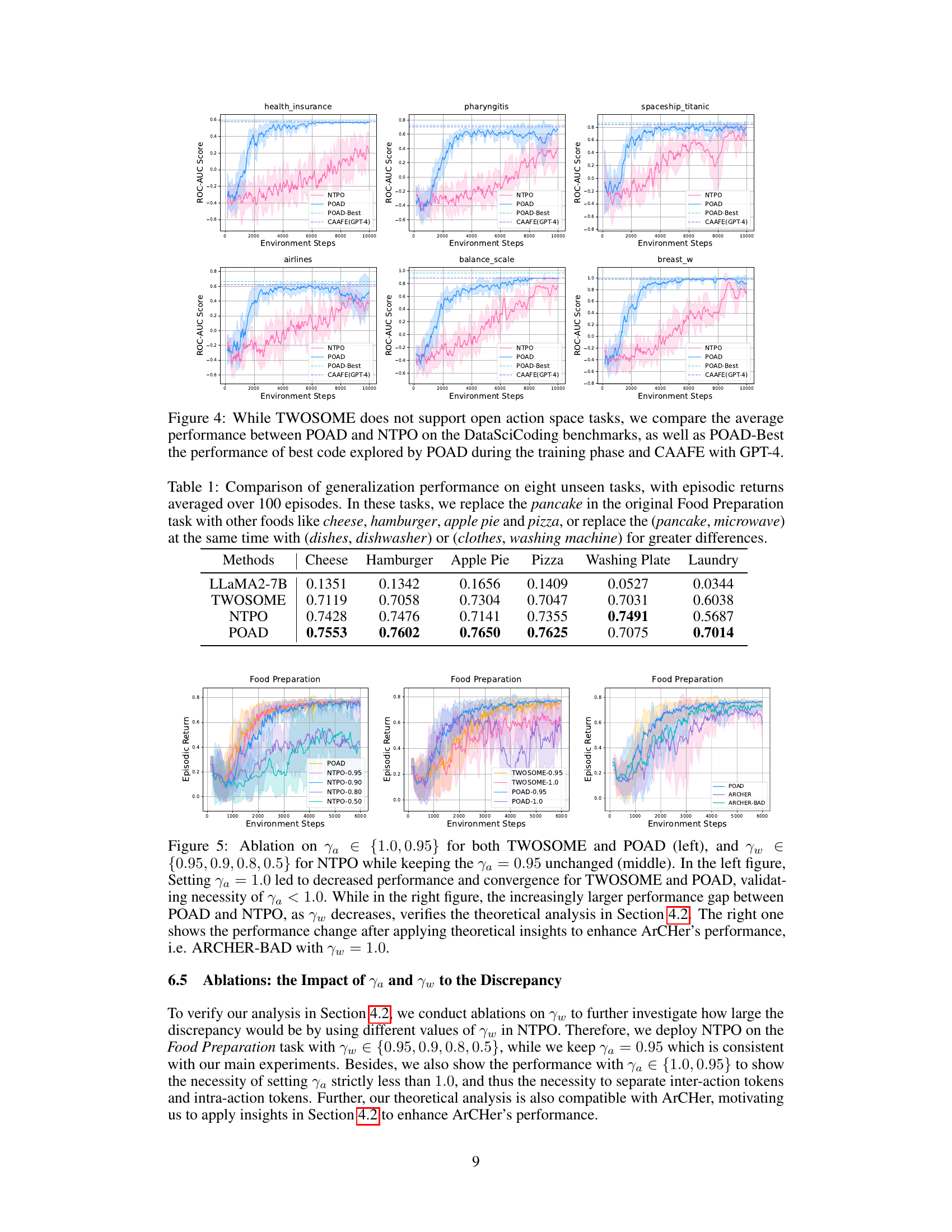

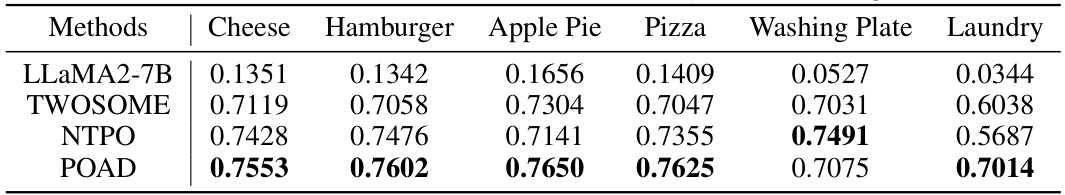

This figure compares the performance of three reinforcement learning algorithms (TWOSOME, NTPO, and POAD) on four different tasks from the Overcooked and VirtualHome environments. The x-axis represents the number of environment steps, and the y-axis represents the episodic return. The shaded area around each line indicates the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results show that POAD generally outperforms TWOSOME and NTPO in terms of both final performance and learning speed, indicating its effectiveness in aligning language agents with interactive environments.

This figure compares the performance of POAD, NTPO, and TWOSOME on four tasks from the Overcooked and VirtualHome environments. The x-axis represents the number of environment steps, and the y-axis represents the performance (likely average reward or cumulative reward). Each subplot shows the learning curves for the three methods on a specific task, allowing for a comparison of their learning speed and final performance. The shaded areas likely represent standard deviation or confidence intervals, indicating the variability in performance across different runs. The results demonstrate that POAD generally outperforms NTPO and often achieves comparable or even better results than TWOSOME.

This figure shows the training curves of POAD, NTPO, TWOSOME, and ARCHER on four different tasks from Overcooked and VirtualHome. The x-axis represents the number of environment steps, and the y-axis represents the episodic return. The shaded area around each line represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. The figure demonstrates that POAD generally outperforms other methods in terms of both convergence speed and final performance. The comparison highlights POAD’s superior stability and efficiency compared to other methods.

This figure compares four different reinforcement learning approaches, visualizing their credit assignment processes. It shows how each method assigns credit to actions and tokens over multiple steps to achieve a goal. The key takeaway is that POAD, using Bellman backup with action decomposition (BAD), achieves the same outcome as TWOSOME (optimizing at the action level) but with finer-grained token-level supervision. In contrast, NTPO and ARCHER show discrepancies between token-level and action-level optimization.

This figure shows four different scenarios from two different environments used in the paper: Overcooked and VirtualHome. The top two images (a and b) depict the task scenarios from the Overcooked environment, showing the preparation steps for Tomato Salad and Tomato-Lettuce Salad. The bottom two images (c and d) illustrate scenes from the VirtualHome environment, showcasing the Food Preparation and Entertainment tasks. These environments are used to test the performance of the proposed language agent.

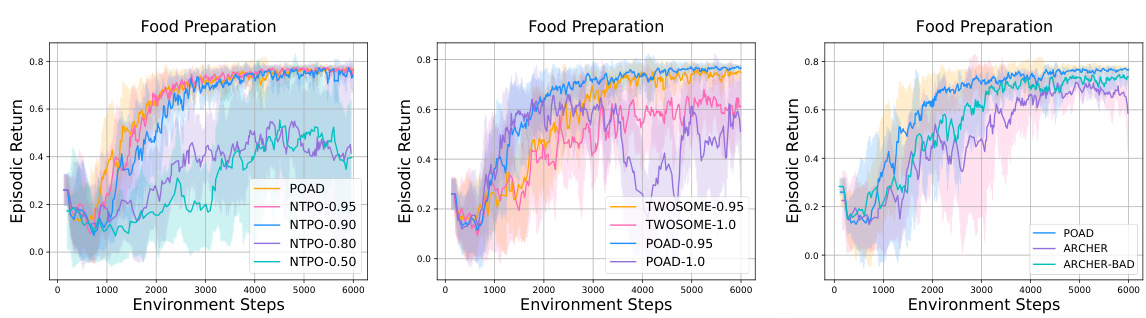

This figure demonstrates the token-level credit assignment learned by the Bellman backup with Action Decomposition (BAD). The left two subfigures show the advantages of each token at the first and last states. The right subfigure compares the volume of credit assignment for key tokens between BAD, TWOSOME, and NTPO. It highlights how BAD precisely assigns credit to key tokens while minimizing credit assignment to irrelevant tokens, unlike the other methods.

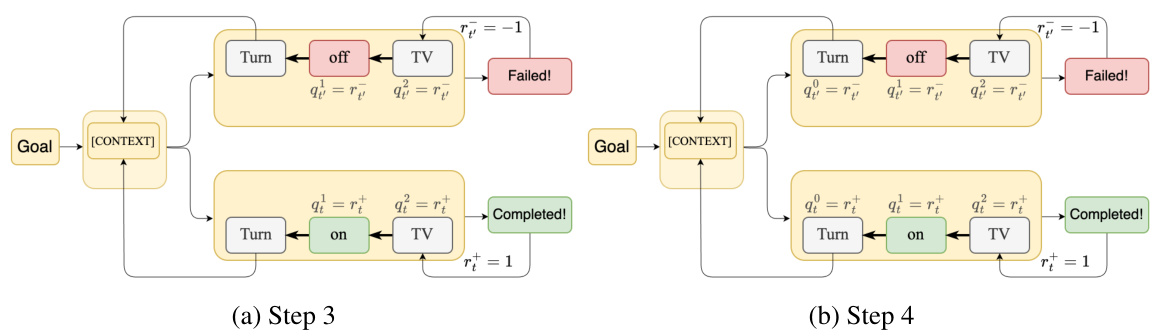

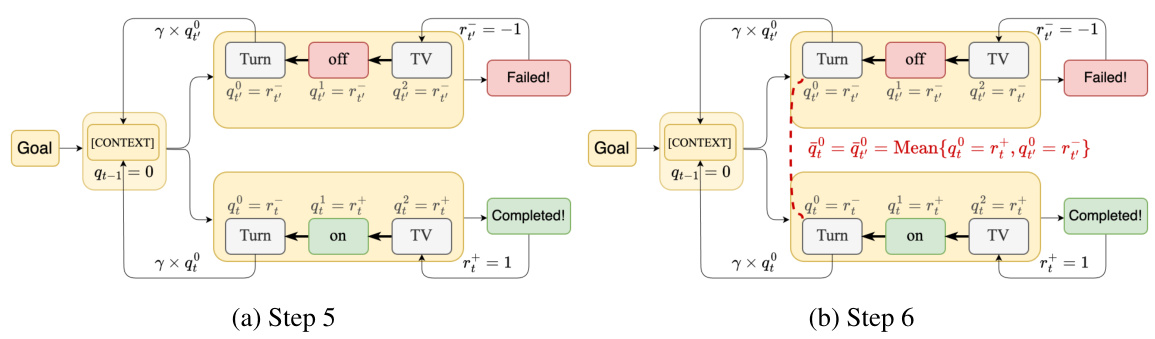

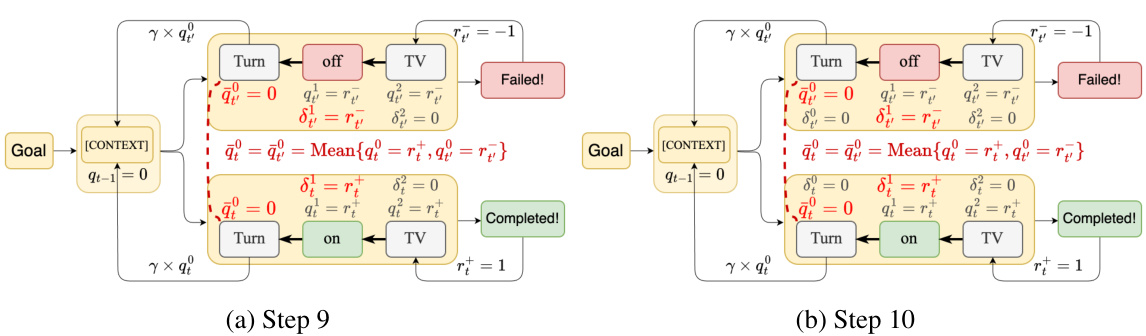

This figure compares the action-level Bellman backup with the proposed Bellman backup with Action Decomposition (BAD). The left side shows the traditional action-level backup, while the right side illustrates the BAD method. The key difference is that BAD assigns credit to individual tokens within an action, providing finer-grained supervision for policy optimization. The figure uses the example of turning on a TV to illustrate how the credit is assigned step by step. Appendix L provides a detailed breakdown of the BAD process shown on the right side.

This figure compares the action-level Bellman backup with the proposed Bellman backup with Action Decomposition (BAD). The left side shows the traditional action-level approach, while the right side illustrates BAD. BAD provides finer-grained credit assignment by considering individual tokens within an action, leading to more precise policy updates. The Appendix L provides a detailed step-by-step explanation of the BAD process shown on the right.

This figure compares the action-level Bellman backup with the proposed Bellman backup with Action Decomposition (BAD). The left side shows the traditional action-level backup, while the right side shows the proposed BAD method. The key difference is that BAD provides finer-grained credit assignment to individual tokens within an action, rather than assigning credit to the entire action as a whole. Appendix L provides a detailed, step-by-step explanation of BAD.

This figure compares the action-level Bellman backup with the proposed Bellman backup with Action Decomposition (BAD). The left side shows the traditional action-level backup, where credit is assigned to the whole action. The right side shows BAD, where credit is assigned to individual tokens within the action. The step-by-step breakdown of BAD is provided in Appendix L for better understanding.

This figure shows a step-by-step breakdown of how the Bellman backup with Action Decomposition (BAD) precisely assigns credit to each token. It details steps 7 and 8 of the BAD process, showing how credit is modified and back-propagated for tokens in both positive and negative trajectories, ultimately leading to the calculation of advantage values for optimization.

More on tables

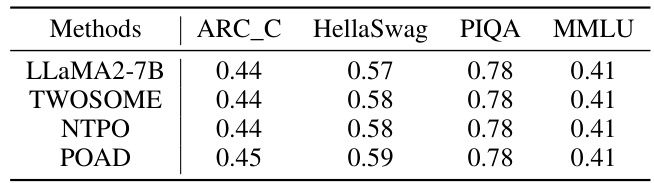

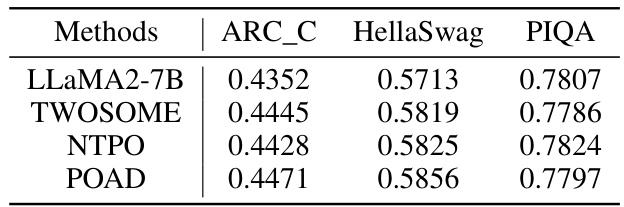

This table presents the zero-shot performance of different language models (LLaMA2-7B, TWOSOME, NTPO, and POAD) on four common NLP benchmarks: ARC_C, HellaSwag, PIQA, and MMLU. It demonstrates the impact of fine-tuning the language models using reinforcement learning techniques (POAD, TWOSOME, and NTPO) on their original capabilities, specifically focusing on whether the fine-tuning process negatively affected their performance on these standard NLP tasks. The results show little to no negative effect, suggesting the proposed methods successfully align language models with embodied environments without compromising their core linguistic abilities.

This table shows the average training time of the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) model on different datasets using one Nvidia A100 GPU. It provides the wall-clock time for training and the number of environmental steps taken for each dataset. The datasets are those used in the DataSciCoding task, which involves training language models to generate code for data science tasks.

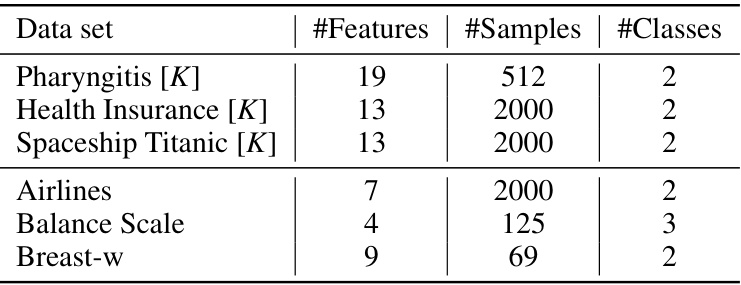

This table shows the details of six datasets used in the DataSciCoding experiments. Three datasets (Pharyngitis, Health Insurance, Spaceship Titanic) are from Kaggle, while the remaining three (Airlines, Balance Scale, Breast-w) are from OpenML. For each dataset, the number of features, samples, and classes are listed. The [K] designation indicates that the dataset originates from Kaggle.

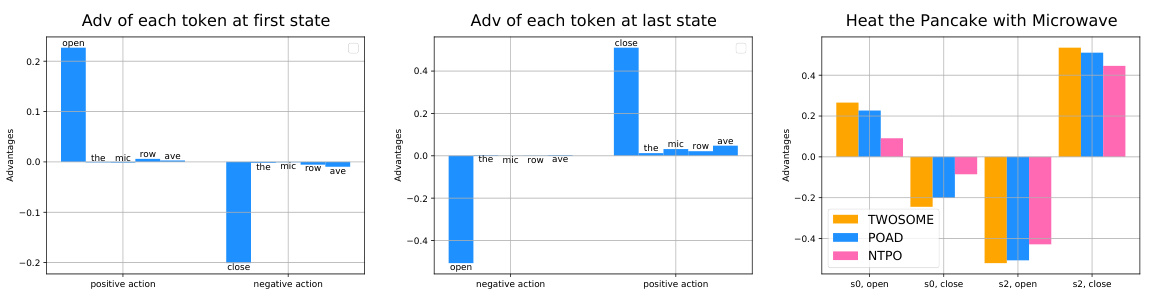

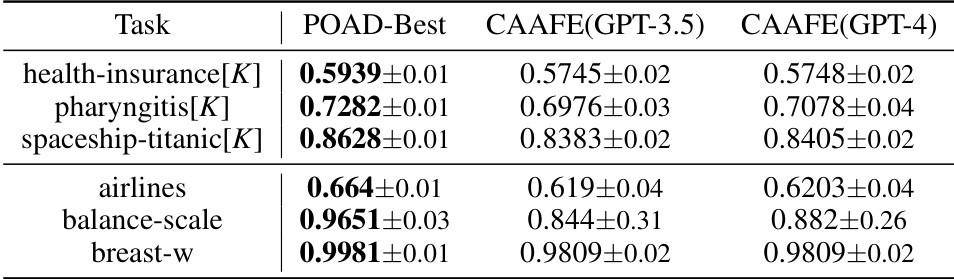

This table compares the performance of the best code generated by POAD using CodeLLaMA-7B against CAAFE (using GPT-3.5 and GPT-4) across six different datasets. It highlights the relative performance of POAD against state-of-the-art AutoML methods, particularly on datasets with higher complexity.

This table presents the average training time and the number of environmental steps for the POAD model on six different datasets used in the DataSciCoding task. The datasets vary in size and complexity, which impacts the training time. The table shows that training times generally range from approximately 1 hour and 43 minutes to 3 hours and 5 minutes, indicating a reasonable training time for this task and scale of model.

This table shows a comparison of generalization performance across eight unseen tasks using different methods (LLaMA2-7B, TWOSOME, NTPO, and POAD). The tasks involve replacing the original pancake task with various food items or kitchen appliances to test the models’ ability to generalize to similar but unseen tasks. Results are reported as episodic returns averaged over 100 episodes, with success rates within 50 timesteps in parentheses.

This table presents the zero-shot performance of four different language models (LLaMA2-7B, TWOSOME, NTPO, and POAD) on three common sense reasoning benchmarks: ARC_C, HellaSwag, and PIQA. Zero-shot performance indicates the models’ performance without any fine-tuning or specific training on these particular benchmarks. The results show the scores achieved by each model on each benchmark, providing a comparison of their reasoning capabilities in a common sense context.

This table presents the zero-shot performance of three different language models (LLaMA2-7B, TWOSOME, NTPO, and POAD) on a variety of tasks from the Massive Multitask Language Understanding benchmark. The results show the performance of each model on each individual task, providing a detailed comparison of their zero-shot capabilities across diverse domains.

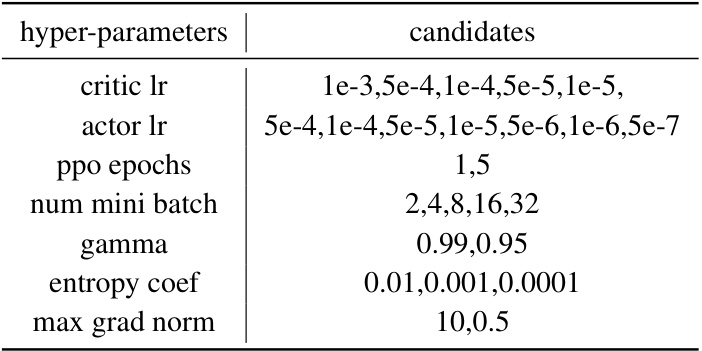

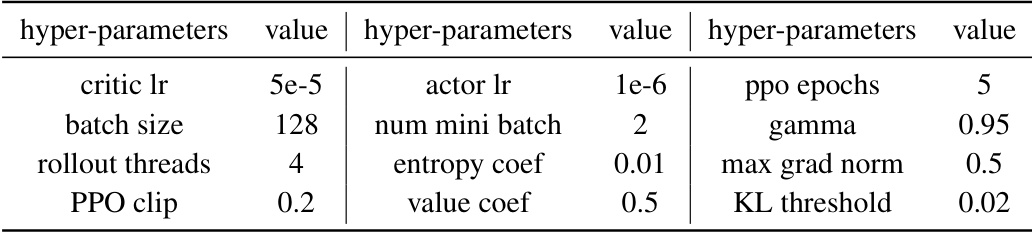

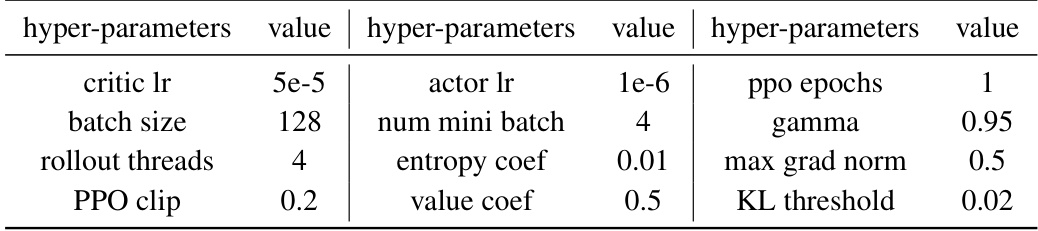

This table presents the hyperparameter candidates explored during the grid search in three different environments: Overcooked, VirtualHome, and DataSciCoding. The hyperparameters considered include learning rates for both critic and actor networks, the number of PPO epochs, the mini-batch size used during training, the discount factor (gamma), the entropy coefficient, and the maximum gradient norm.

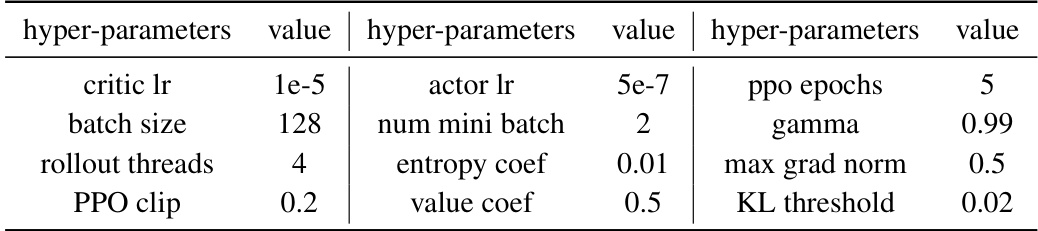

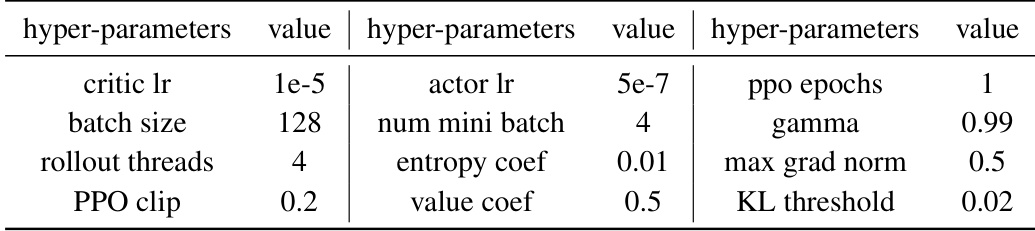

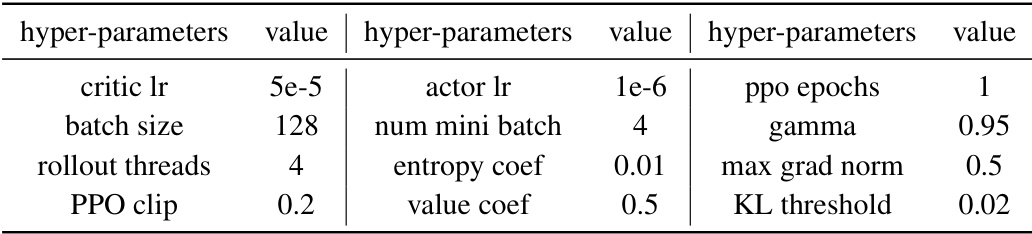

This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) method on the Overcooked tasks. It lists the values used for parameters such as critic learning rate, actor learning rate, batch size, number of mini-batches, PPO clipping value, entropy coefficient, value coefficient, maximum gradient norm, gamma (discount factor), and KL (Kullback-Leibler divergence) threshold. These parameters were tuned for optimal performance within the POAD framework on Overcooked.

This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) method in the Overcooked environment. The hyperparameters are values chosen through a grid search or experimentation that yielded optimal performance for POAD on this specific task. The parameters listed control various aspects of the training process, including learning rates, batch size, and exploration parameters.

This table shows the hyperparameters used for the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) method in the Overcooked environment. It lists the values used for various parameters including learning rates for the critic and actor networks, batch size, number of mini-batches, PPO clipping, entropy coefficient, value coefficient, gamma, max gradient norm, and KL threshold. These parameters were tuned to optimize the performance of the POAD algorithm in this specific environment.

This table presents the average training time in hours and minutes for the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) model across six different datasets. Each dataset was trained using a single Nvidia A100 GPU. The number of environmental steps for each dataset is also provided.

This table presents the average training time in hours and minutes for the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) method on different datasets using a single Nvidia A100 GPU. The number of environmental steps for each task is also included.

This table shows the average training time in hours and minutes for the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) method on different datasets using one Nvidia A100 GPU. The number of environmental steps is also provided.

This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the Policy Optimization with Action Decomposition (POAD) method in the Overcooked experimental environment. It lists the values used for various parameters such as the critic learning rate, actor learning rate, number of PPO epochs, batch size, mini-batch size, gamma, entropy coefficient, value coefficient, maximum gradient norm, and KL threshold. These parameters were found to produce the best performance for POAD in the Overcooked tasks.

This table presents the average training time taken by the POAD algorithm for each dataset used in the experiments. The training was performed using a single Nvidia A100 GPU. The table shows the wall-time (hours and minutes) and the number of environmental steps for each dataset.

Full paper#