↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

This research investigates the privacy implications of machine unlearning, the process of removing a user’s data from a model after it’s been trained. The common belief is that simple models don’t pose significant privacy risks, but this study proves otherwise. It reveals that requesting data removal can create vulnerabilities that allow attackers to reconstruct the user’s information with astonishing accuracy, even with very basic algorithms. This is because the model’s change before and after deletion exposes data to advanced reconstruction attacks.

The researchers demonstrate this by creating a highly effective attack on linear regression models. They extend this work to other model architectures and show the attack’s effectiveness across various datasets. The findings emphasize the surprising privacy risks associated with machine unlearning and suggest that techniques like differential privacy should be used to mitigate these vulnerabilities. This research provides a significant contribution by highlighting this vulnerability and encouraging the development of stronger privacy-preserving strategies for machine unlearning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the common assumption that simple models are inherently safe from privacy attacks in the context of machine unlearning. It reveals a significant privacy vulnerability, even in seemingly secure systems, and motivates the need for stronger privacy-preserving techniques, such as differential privacy, during model training and updates. This work opens up new avenues of research into developing more robust machine unlearning methods that address the identified vulnerabilities and provide better data autonomy. It also highlights the need for careful consideration of privacy risks when designing and deploying machine unlearning systems.

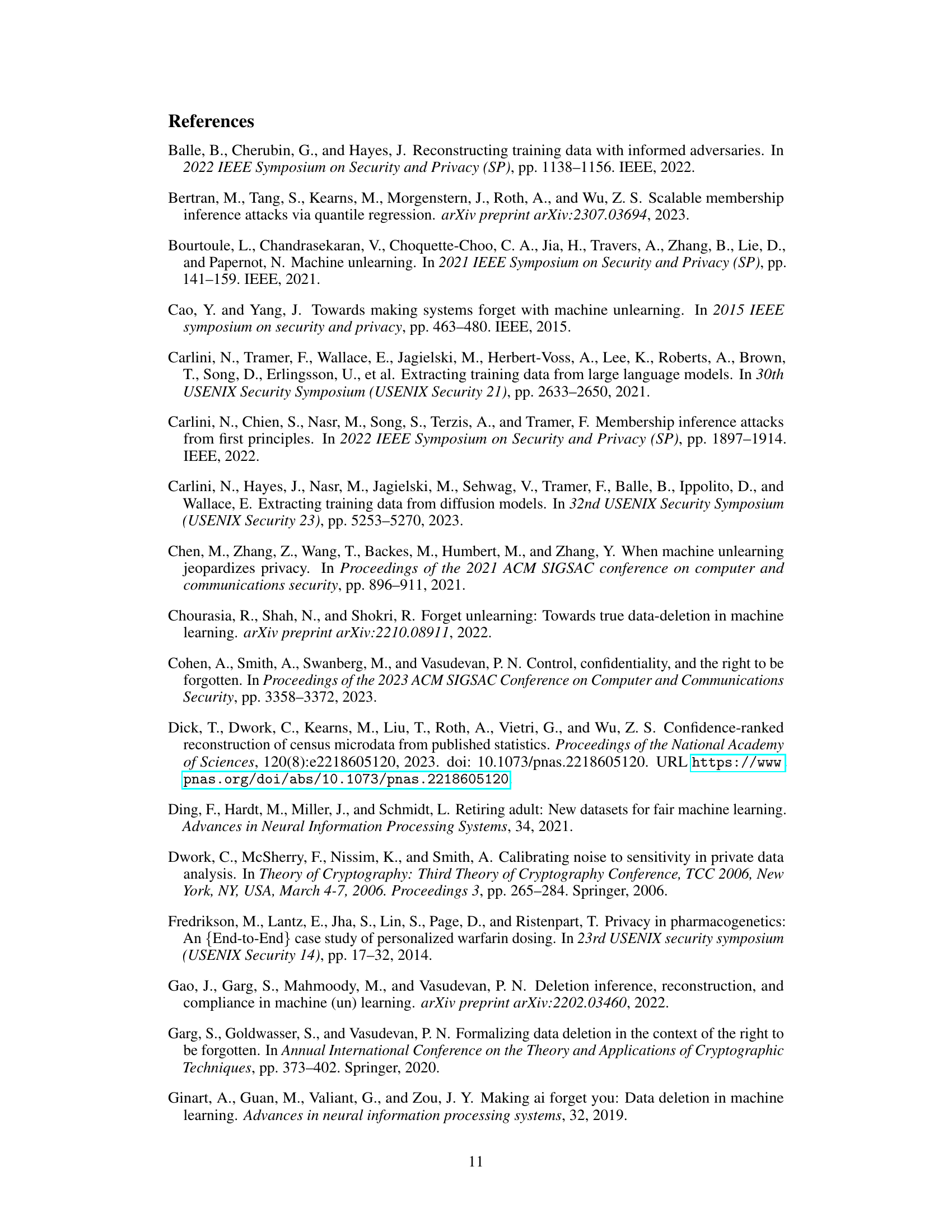

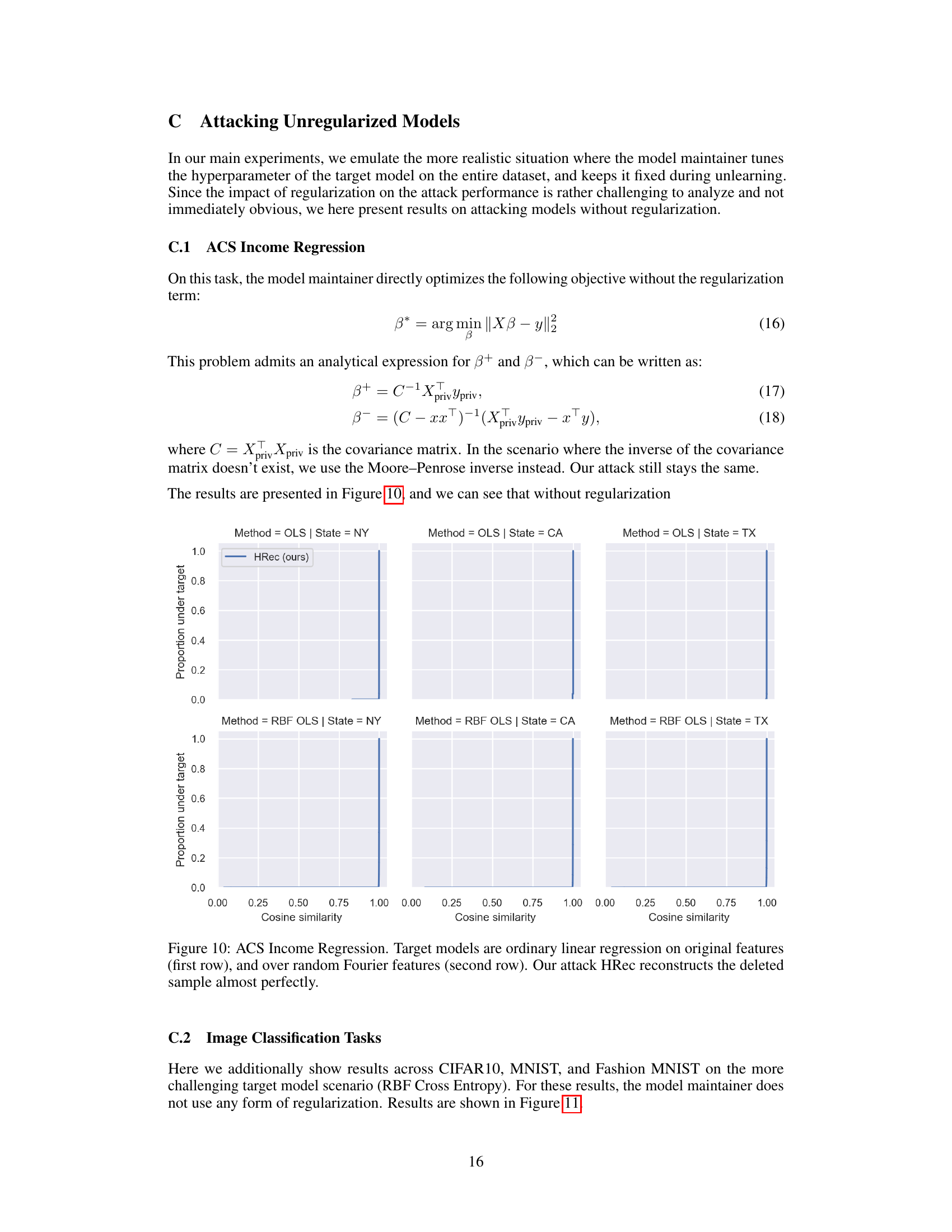

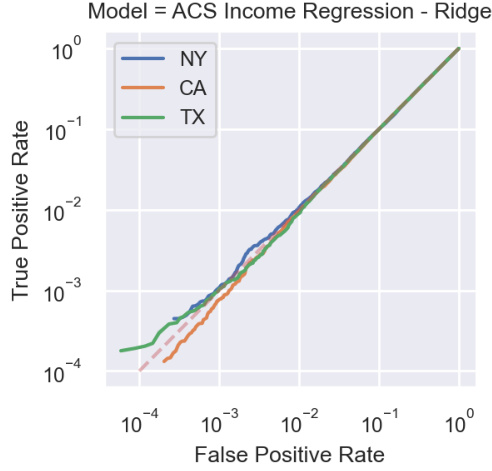

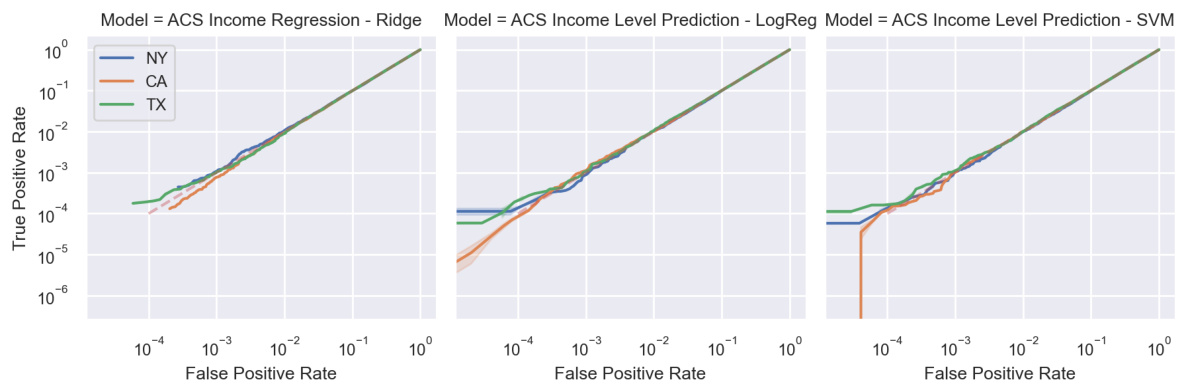

Visual Insights#

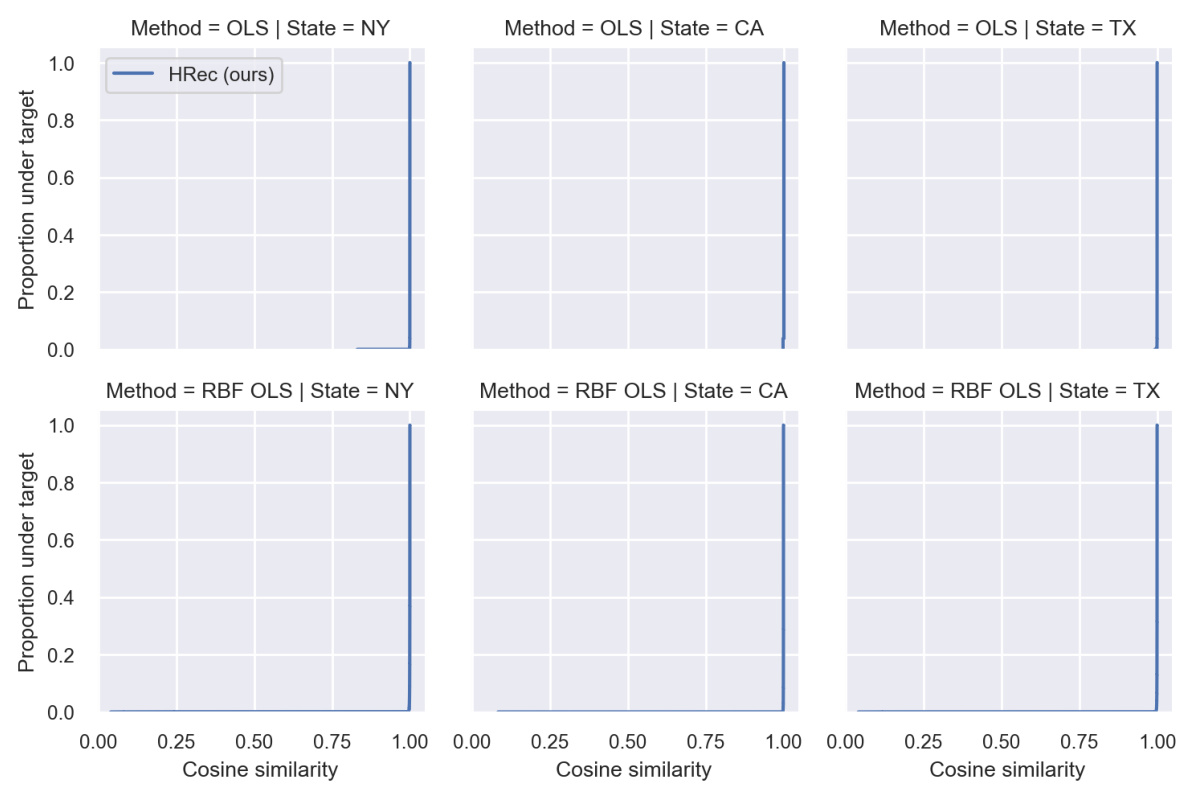

This figure shows the results of membership inference attacks on a ridge regression model trained on the ACS Income dataset. The results are presented as ROC curves (Receiver Operating Characteristic curves) for three different states: NY, CA, and TX. The curves show that the true positive rate (the proportion of correctly identified members) is very close to the false positive rate (the proportion of non-members incorrectly identified as members). This indicates that the attack performs poorly and is essentially no better than random guessing. This is evidence that linear models are not easily vulnerable to membership inference attacks.

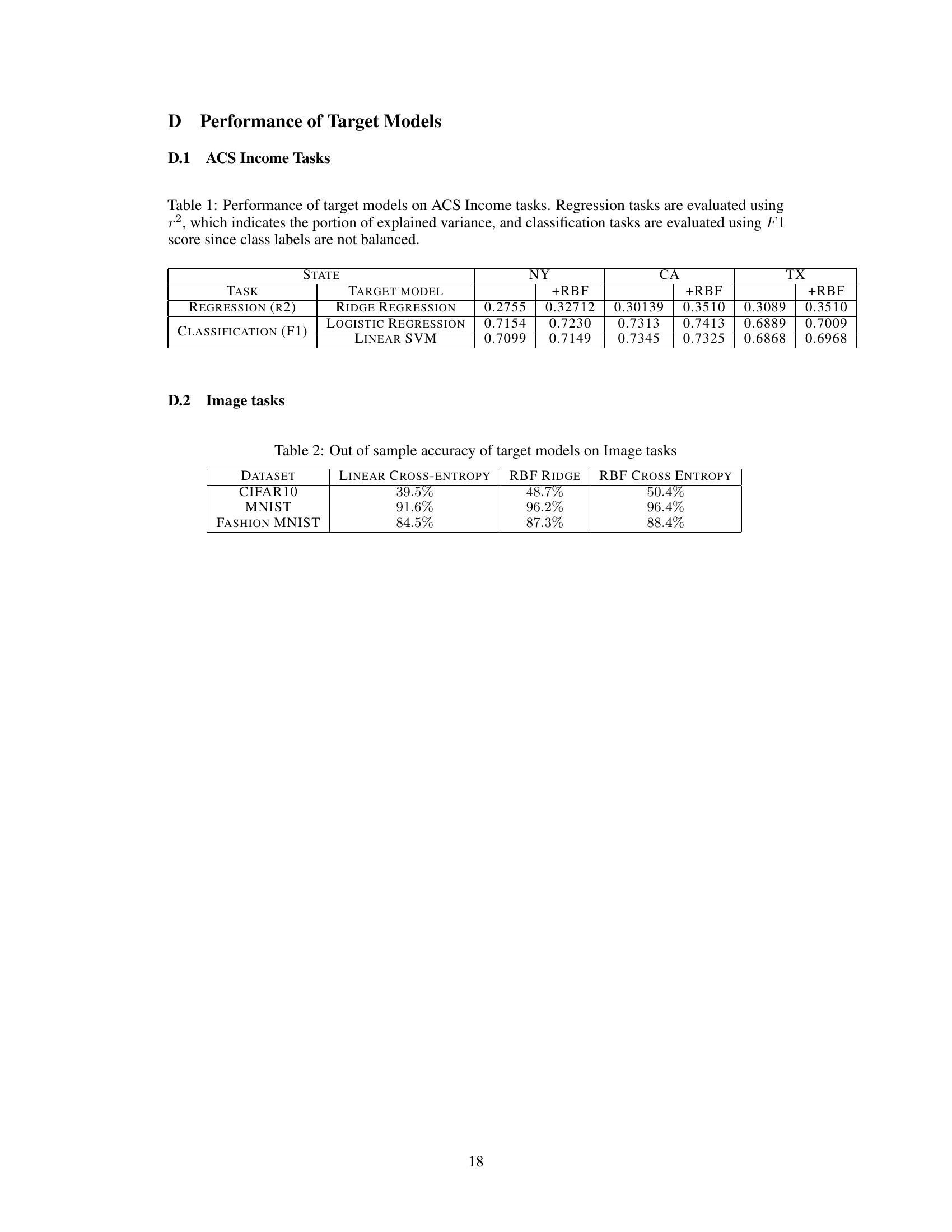

This table presents the performance of different models (Ridge Regression, Logistic Regression, and Linear SVM) on the American Community Survey (ACS) Income dataset. The performance is measured using two metrics: R-squared (R2) for regression tasks, indicating the proportion of variance explained by the model, and F1-score for classification tasks, a common metric for imbalanced datasets. The table shows results for three states (NY, CA, TX) and with and without Random Fourier Features (RBF).

In-depth insights#

Unlearning Attacks#

The concept of “Unlearning Attacks” highlights a critical vulnerability in machine unlearning, where an individual’s data is removed from a model. Counterintuitively, the process of removing this data can inadvertently reveal sensitive information. The attacks exploit the differences between a model trained with and without the target data, enabling reconstruction of the original data with potentially high accuracy. This is especially concerning for simple models, where privacy risks were previously underestimated. Linear models, in particular, are shown to be vulnerable. The attacks leverage mathematical properties of various model types and loss functions, demonstrating a broader threat than previously recognized. The implications are significant for data privacy and autonomy, challenging the assumptions underlying the machine unlearning paradigm. Robust defense mechanisms are urgently needed to protect individuals’ privacy in the context of data deletion requests.

Linear Model Risks#

The notion of ‘Linear Model Risks’ in machine unlearning unveils a surprising vulnerability. While simpler models like linear regression were previously considered less susceptible to privacy breaches, this heading highlights that data removal requests expose these models to highly effective reconstruction attacks. The simplicity of the model, ironically, makes it easier to pinpoint the exact parameter changes resulting from data deletion. This allows adversaries, with access to the model before and after the deletion, to exploit these changes and reconstruct the deleted data point with high accuracy. This is a crucial finding that challenges the common assumption of linear models’ inherent safety in machine unlearning, demanding a re-evaluation of the privacy implications of data deletion requests, even for the simplest of models. The risk isn’t merely theoretical; empirical results across various datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of these reconstruction attacks, thereby emphasizing the practical threat and the need for stronger privacy mechanisms in machine unlearning techniques.

Reconstruction Attacks#

Reconstruction attacks, within the context of machine unlearning, pose a significant threat to data privacy. These attacks exploit the inherent vulnerabilities created when models are updated to remove the influence of specific individuals’ data. The core issue is that the act of ‘unlearning’ itself can inadvertently leak information, making the removed data points more accessible to attackers than before. The paper highlights this risk, demonstrating that even simple models, previously considered low-risk, become vulnerable when unlearning is implemented. The success of reconstruction attacks hinges on the ability to compare model parameters before and after data removal. This comparison effectively reveals information about the deleted data, thereby enabling its reconstruction. The vulnerability is significant, especially in the absence of robust privacy-preserving techniques like differential privacy. Therefore, careful consideration of this attack vector is critical for developing secure machine unlearning systems.

Beyond Linearity#

The extension of reconstruction attacks beyond the confines of linear models is a crucial step in understanding the vulnerability of machine unlearning. The simplicity of linear models allowed for elegant mathematical analysis, enabling the development of precise and effective attacks. However, real-world machine learning models are rarely linear, often involving complex architectures and non-linear activation functions. Moving ‘Beyond Linearity’ requires addressing how the principles of the linear attack might be generalized to these more intricate models. This involves tackling significant computational challenges, such as approximating gradients and Hessians efficiently for large, complex models, along with the added difficulty of handling non-linear relationships within the data. The paper’s exploration of second-order unlearning methods using Newton’s method hints at a viable approach, but this approximation’s accuracy and effectiveness require further investigation. The success of such an extended attack would have far-reaching implications, highlighting a significant security risk inherent in many deployed machine unlearning systems. The findings emphasize the need for stronger safeguards, such as differential privacy, to ensure data protection in the face of sophisticated reconstruction attacks against non-linear models.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize developing robust machine unlearning techniques that are provably resistant to reconstruction attacks. This includes exploring advanced methods beyond simple parameter adjustments, such as differential privacy or homomorphic encryption, to ensure data is truly removed while maintaining model utility. Investigating new model architectures less susceptible to memorization is crucial, perhaps focusing on models with inherent privacy-preserving properties or those that leverage federated learning paradigms. Furthermore, research should delve into developing more sophisticated attack models, going beyond simple linear models to encompass more complex neural networks, and extending attacks to broader model update strategies. Ultimately, a theoretical framework unifying privacy, utility, and unlearning is needed to provide rigorous guarantees and guide the development of truly secure and effective machine unlearning algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

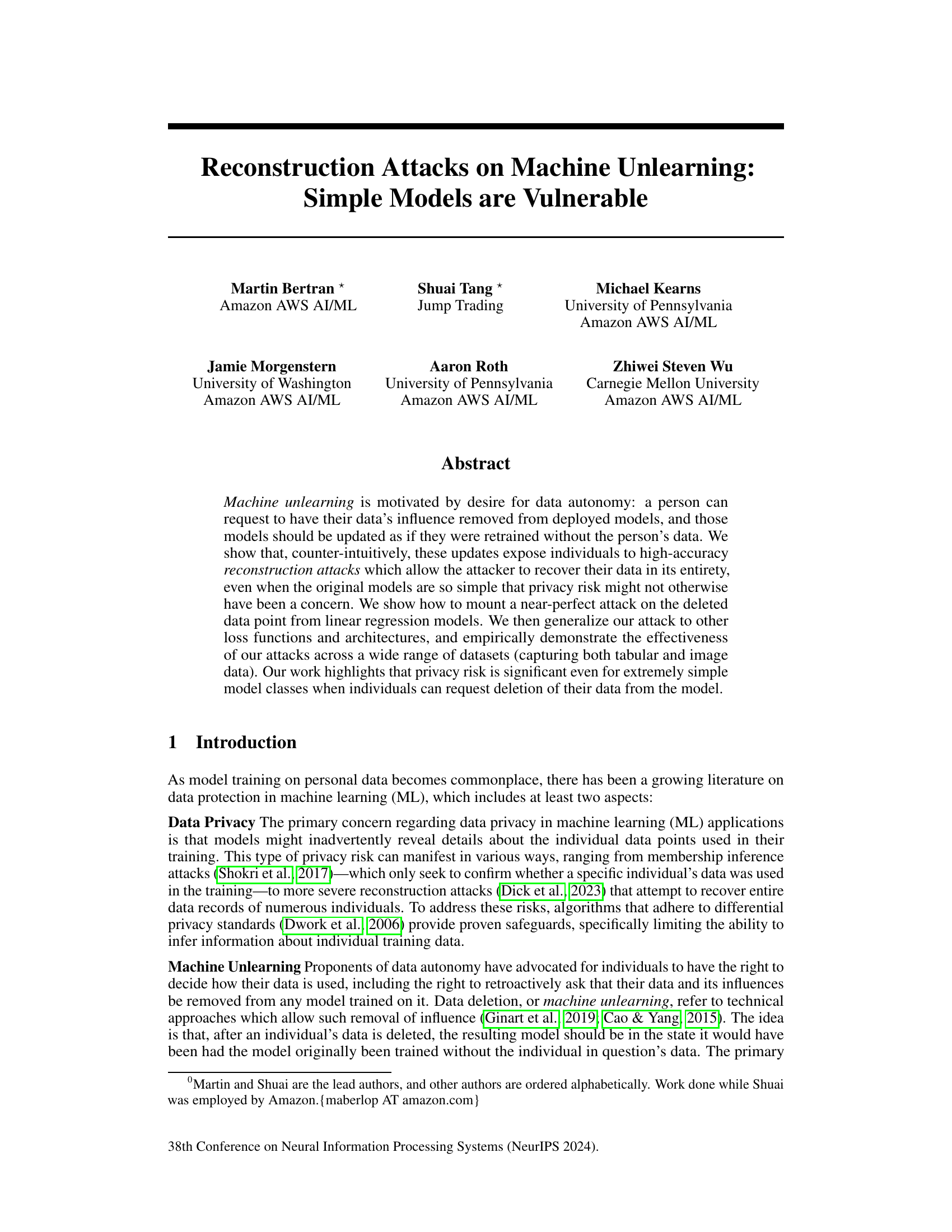

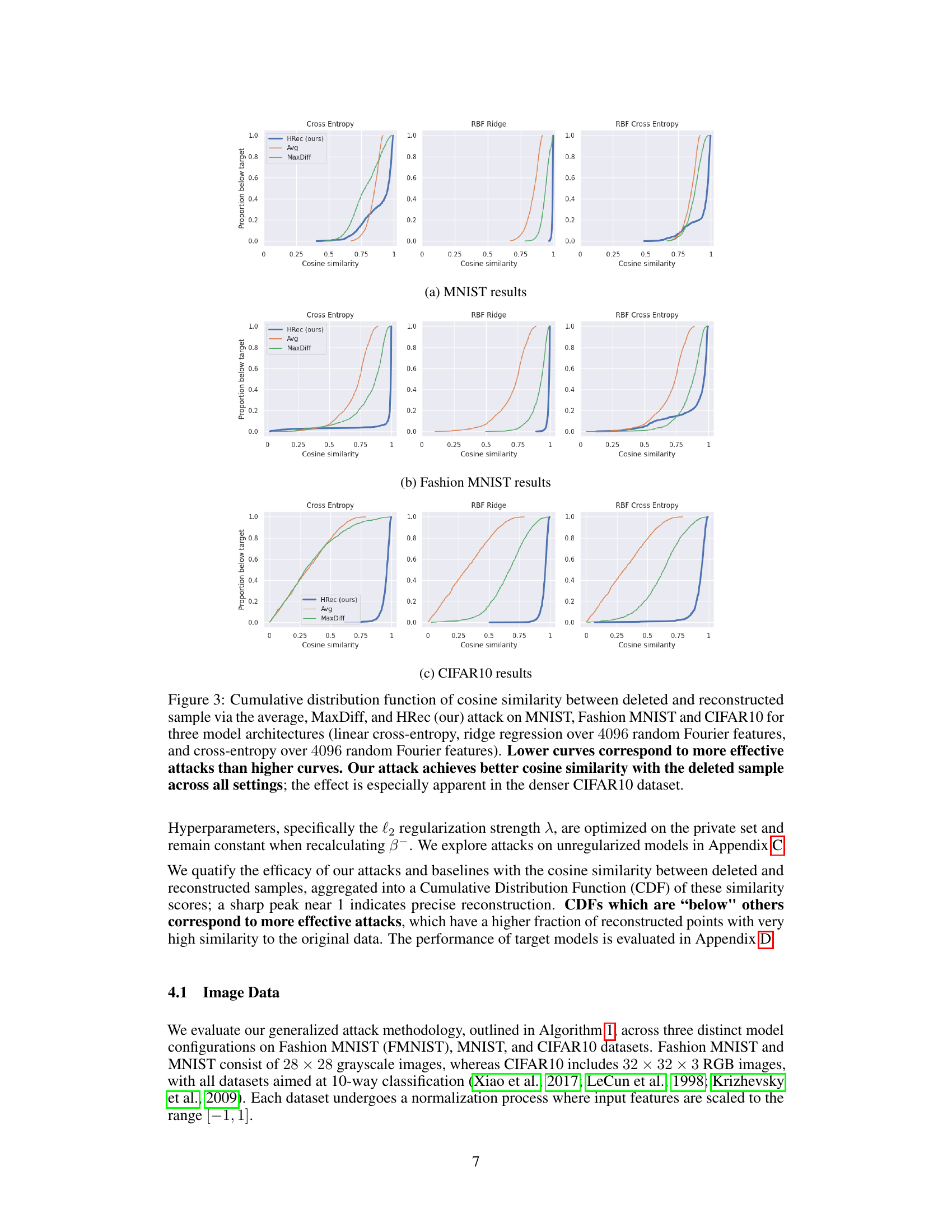

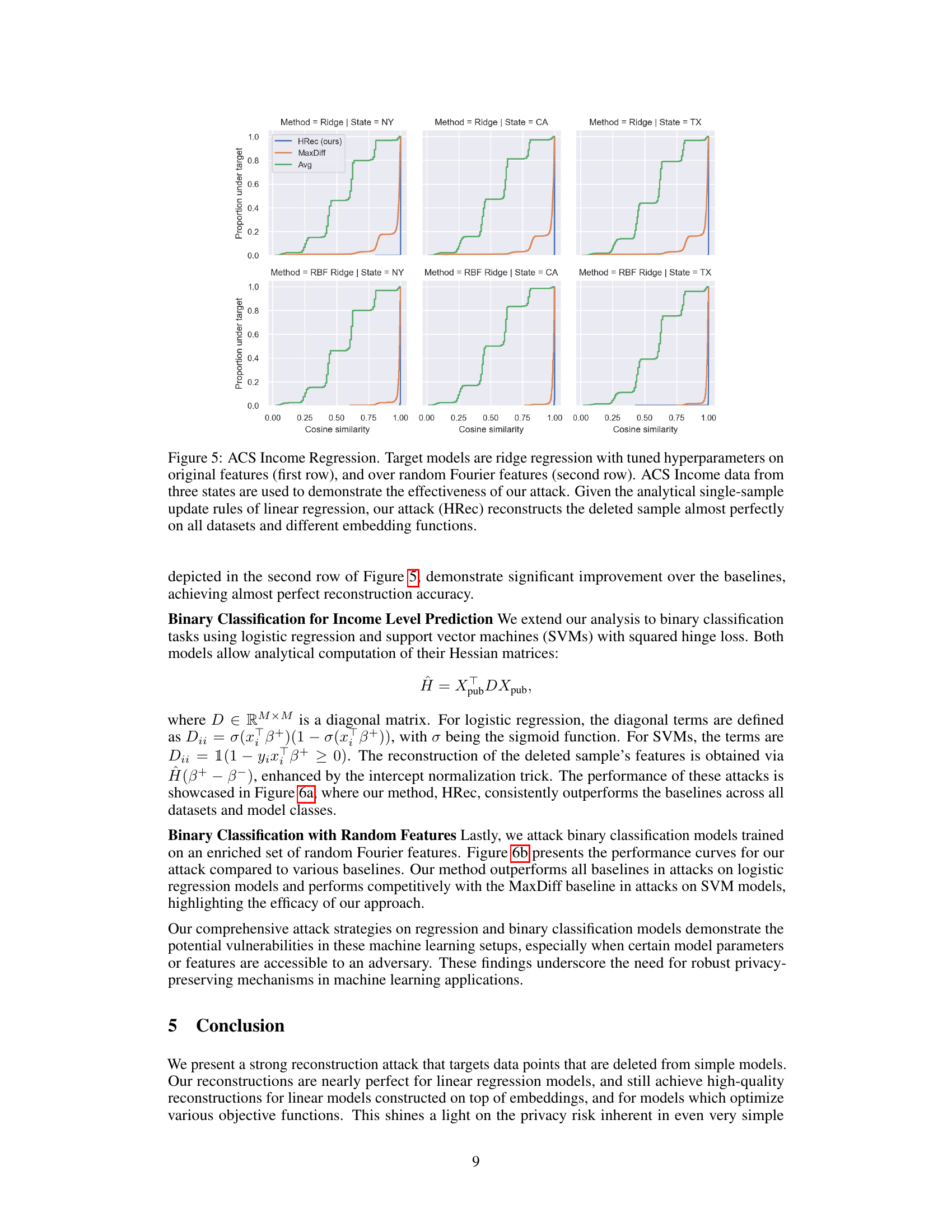

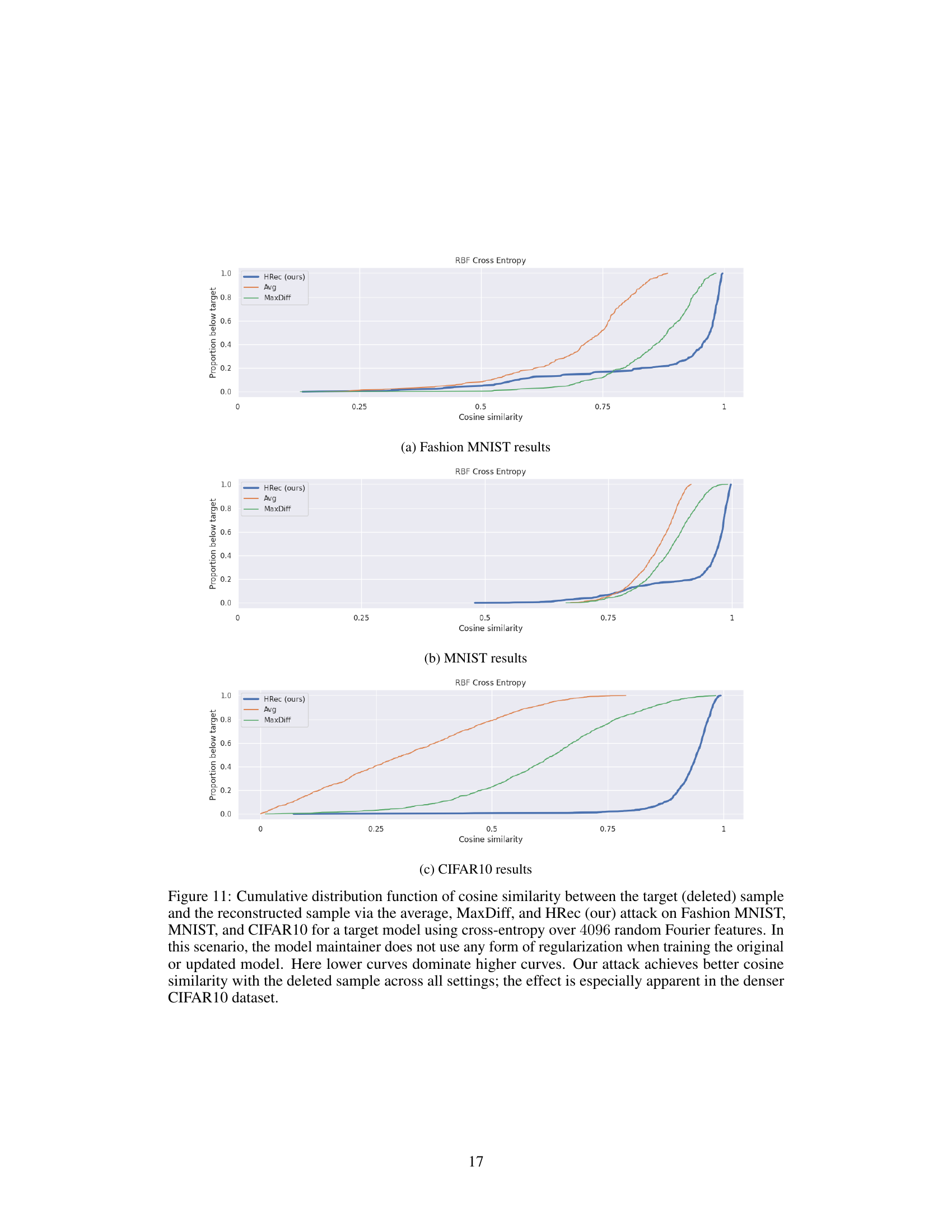

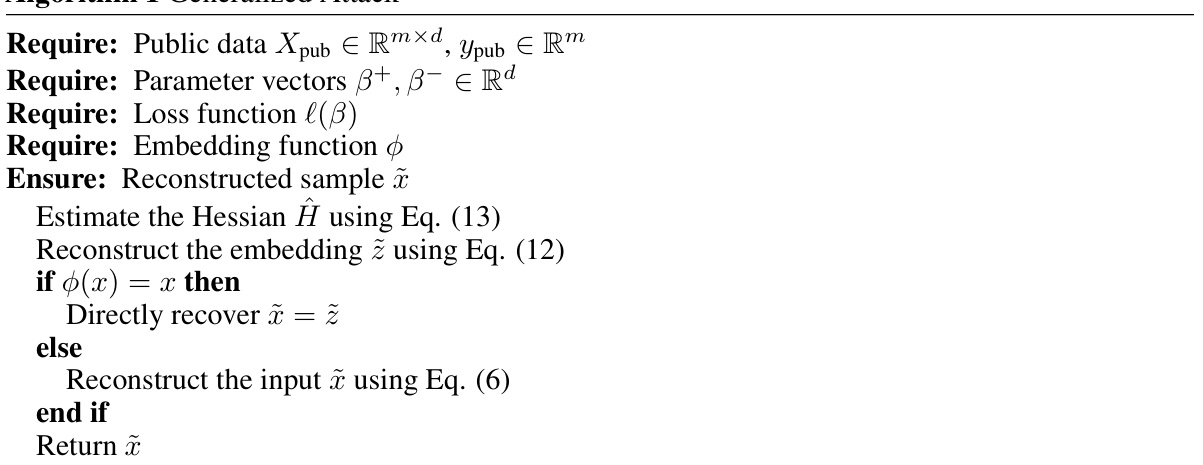

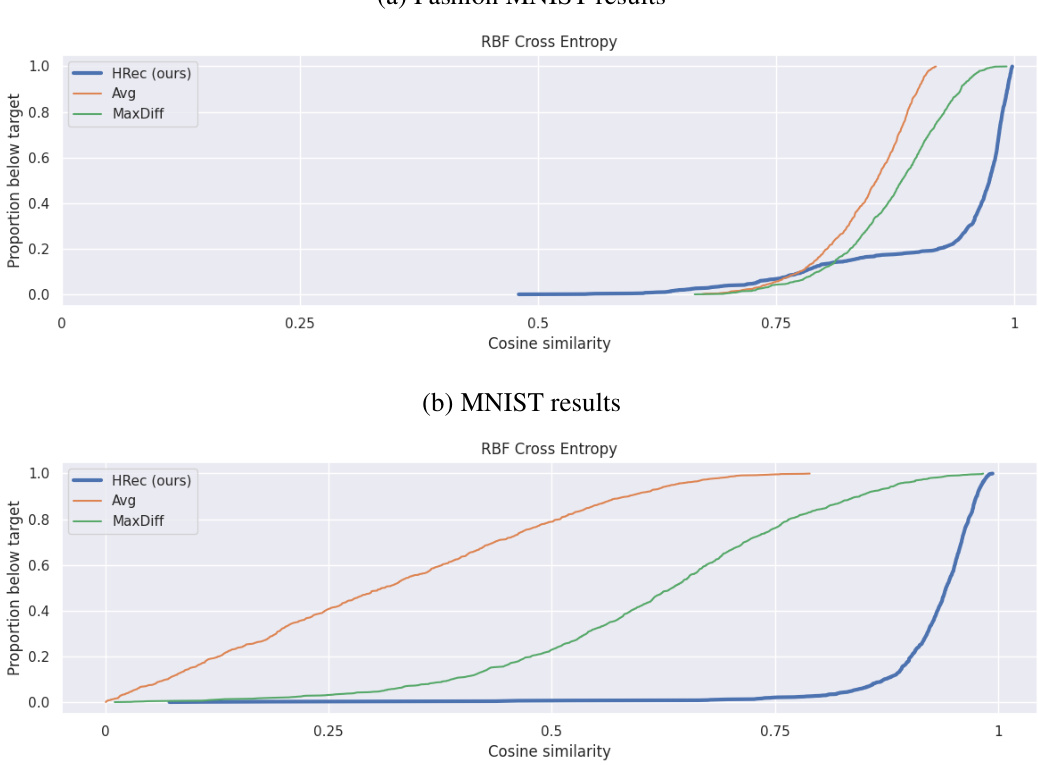

This figure displays the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of cosine similarity scores between the original deleted data points and their reconstructions using three different methods: the proposed HRec attack, the average baseline, and the MaxDiff baseline. The CDFs are shown for three datasets (MNIST, Fashion MNIST, CIFAR10) and three model architectures. Lower curves indicate more effective reconstruction, showing the superior performance of the proposed HRec attack, particularly for the denser CIFAR10 dataset.

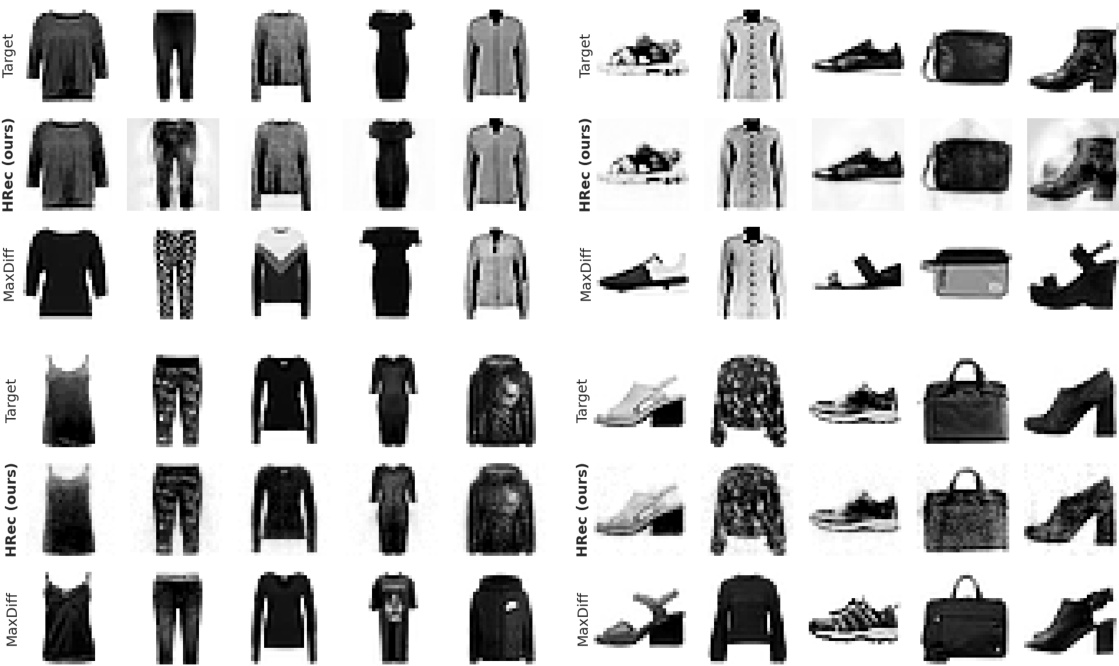

This figure shows the results of reconstruction attacks on Fashion MNIST and MNIST datasets. The model used is a 40K parameter model with cross-entropy loss and random Fourier features. One deleted sample per class label was selected, and the reconstructions are compared using the authors’ method (HRec) and a baseline perturbation method (MaxDiff). HRec shows superior image reconstruction compared to MaxDiff.

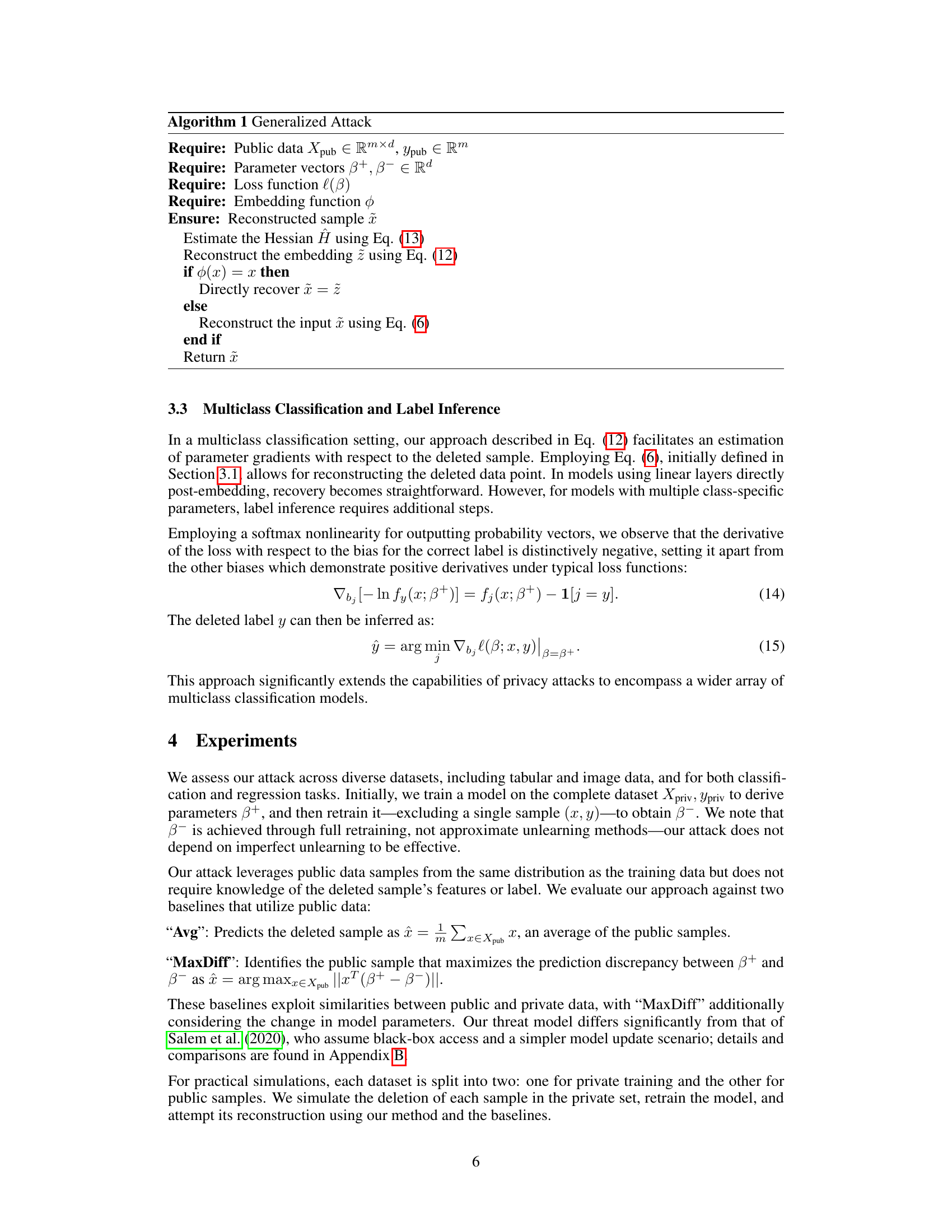

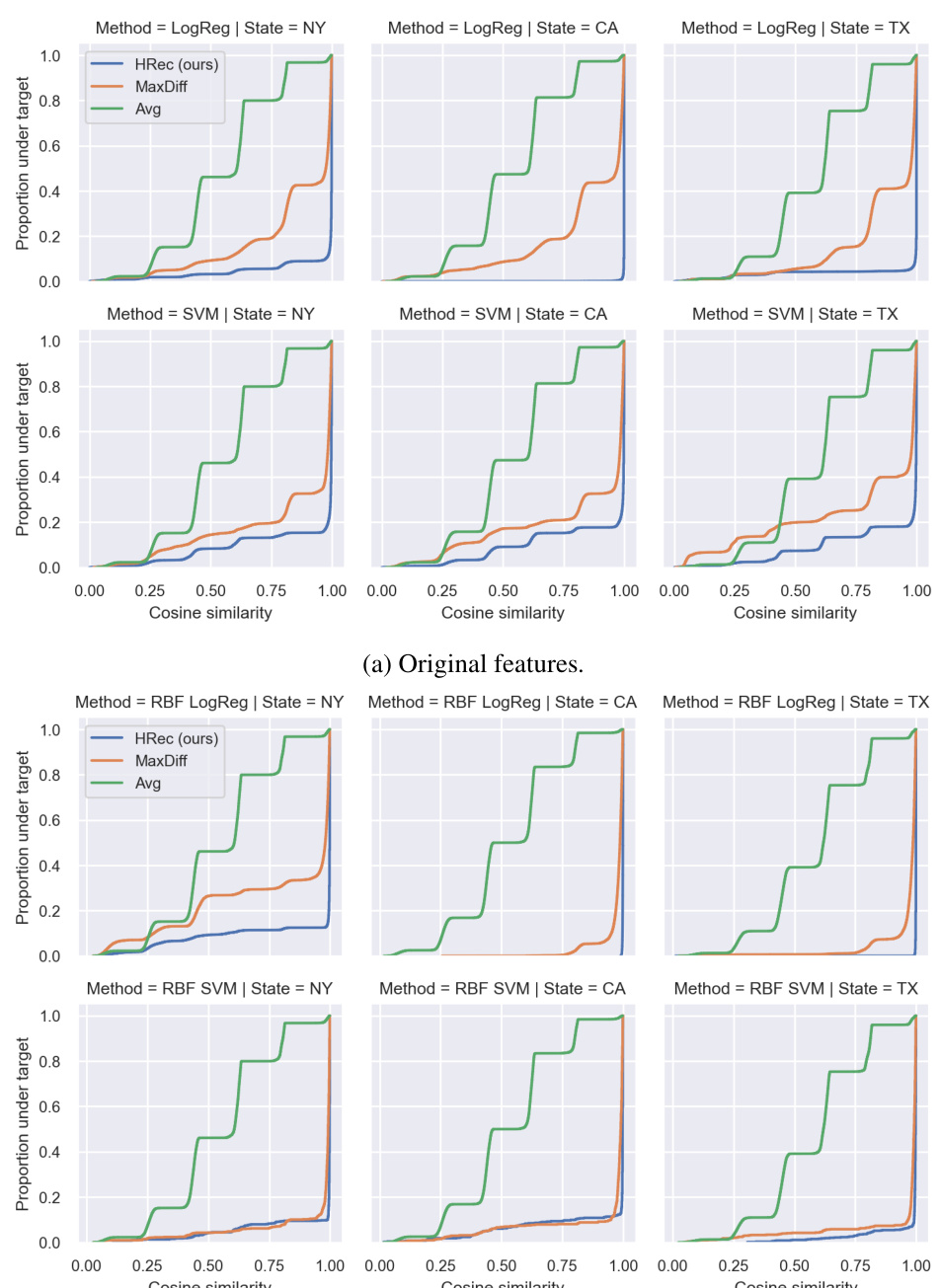

This figure shows the results of reconstruction attacks on ridge regression models using ACS income data from three states (NY, CA, TX). Two model types are used: ridge regression on original features and ridge regression over random Fourier features. The results demonstrate that the proposed reconstruction attack (HRec) achieves almost perfect reconstruction accuracy in all cases, significantly outperforming the baseline methods (Avg and MaxDiff). This highlights the effectiveness of the attack even with different model architectures and data.

This figure compares the performance of three different reconstruction attack methods (average, MaxDiff, and HRec) on three different datasets (MNIST, Fashion MNIST, and CIFAR10) using three different model architectures. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of cosine similarity is used to measure the effectiveness of the attacks. Lower curves represent better reconstruction accuracy. The results demonstrate that the HRec method consistently outperforms the other methods, especially on the more complex CIFAR10 dataset.

This figure presents the results of membership inference attacks performed on three different tasks using the American Community Survey (ACS) data. The attacks aimed to determine whether a given sample was part of the training dataset for a specific model. The results are displayed as ROC curves for three different states: NY, CA, and TX. The curves show the true positive rate against the false positive rate for each state and task. The fact that the curves are close to the diagonal suggests that the attacks perform poorly, highlighting the difficulty in determining the membership of samples in linear models trained on tabular data.

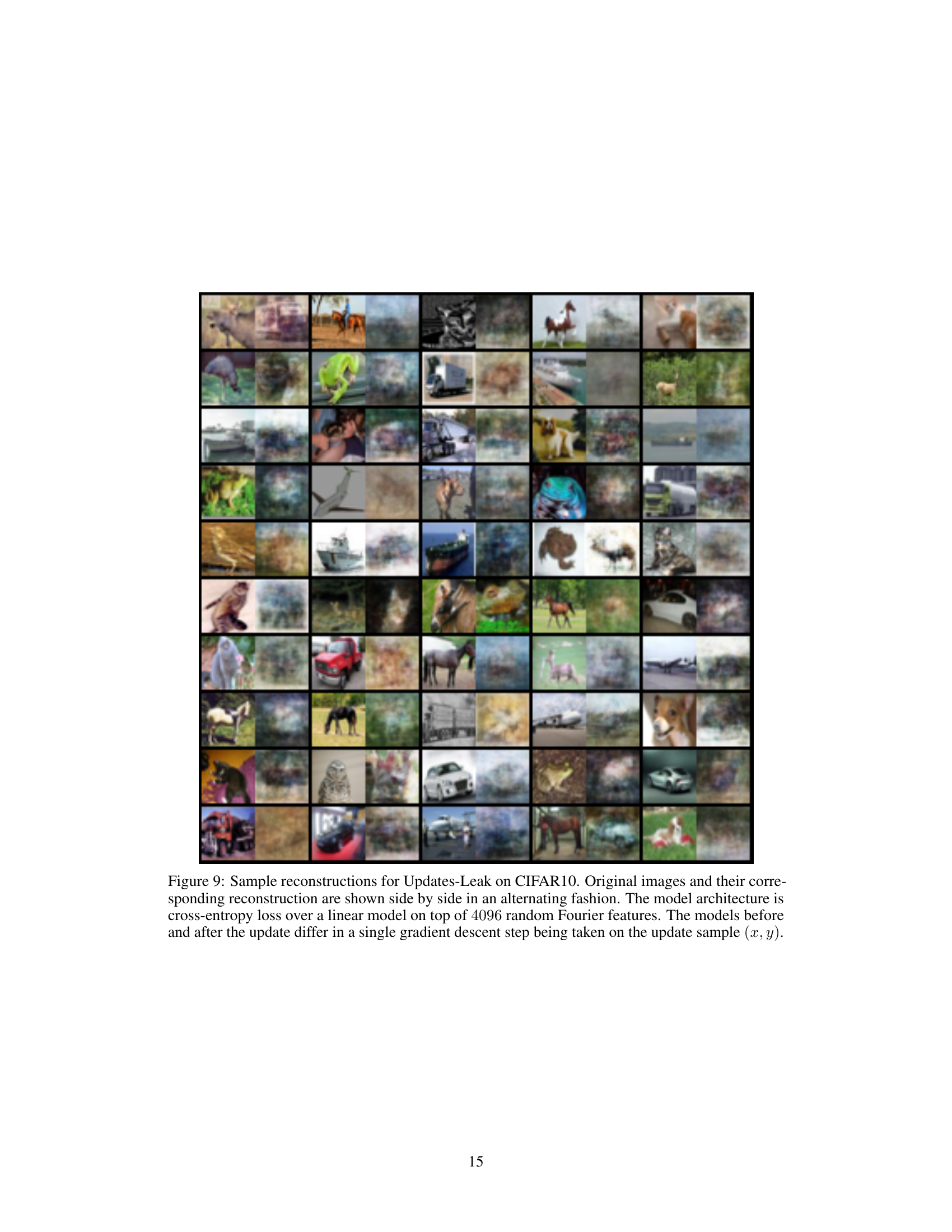

This figure compares the performance of four different reconstruction attacks on the CIFAR10 dataset using a simple model. The attacks are: the average, MaxDiff, Updates-Leak, and HRec (the authors’ method). The y-axis shows the cumulative distribution function of the cosine similarity between the reconstructed and deleted samples, while the x-axis represents the cosine similarity. Lower curves indicate better performance. The figure demonstrates that HRec consistently outperforms the other methods, achieving higher cosine similarity with the deleted sample.

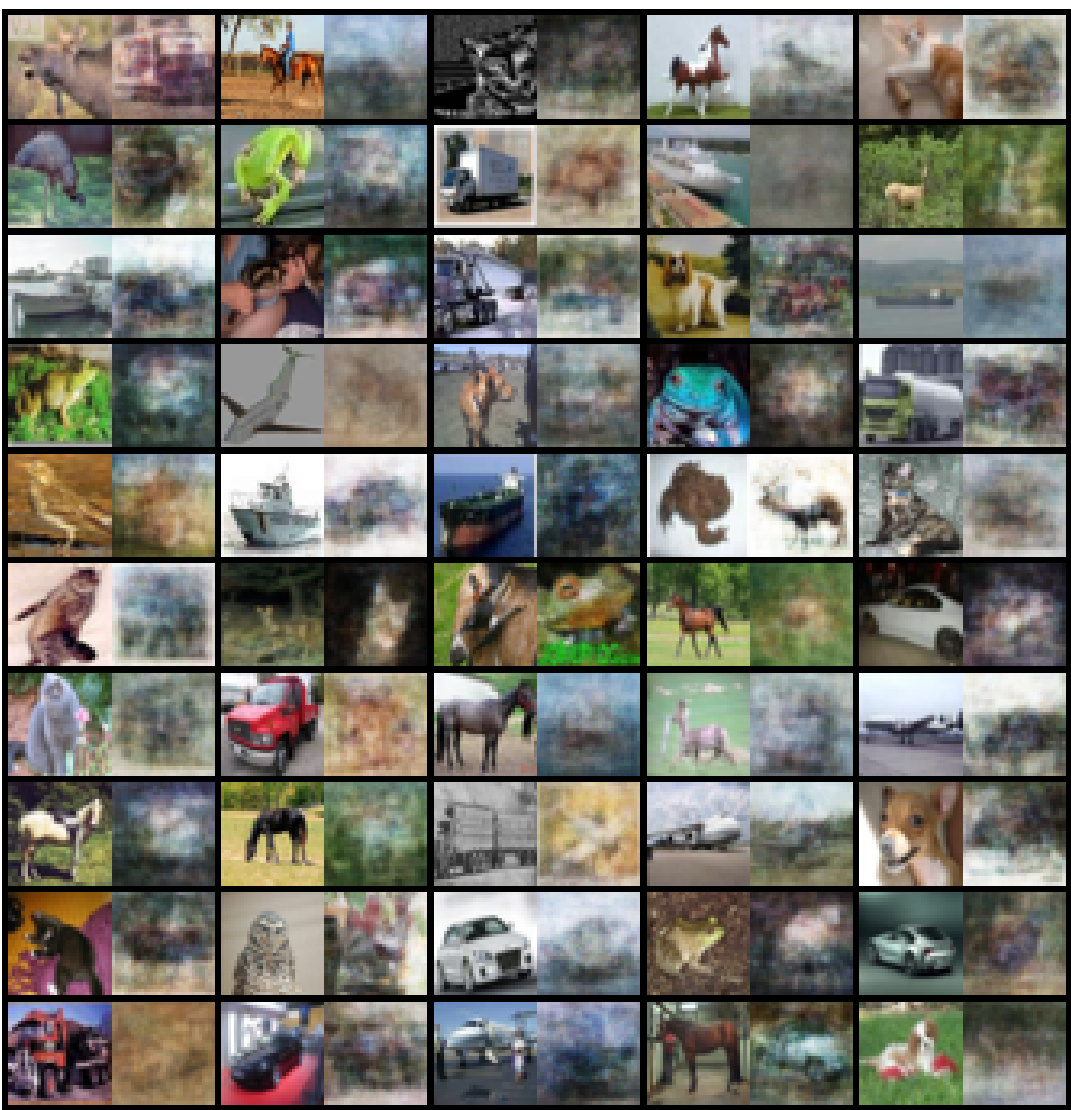

This figure shows the results of reconstruction attacks on CIFAR10 images. Three rows are shown for each image: the original deleted image, a reconstruction using the authors’ method (HRec), and a reconstruction from a baseline method (MaxDiff). The MaxDiff baseline simply finds the public image most different in prediction before and after deletion. The goal is to demonstrate that the authors’ method, HRec, produces reconstructions that closely match the original deleted images, both visually and quantitatively.

This figure shows the results of reconstruction attacks on ACS income regression models. Two model types are used: ordinary linear regression and ridge regression with random Fourier features. The reconstruction accuracy (cosine similarity) is measured and compared between the proposed attack (HRec) and baselines (Average and MaxDiff). The results demonstrate that the HRec attack achieves near-perfect reconstruction of deleted samples, even without regularization.

This figure compares the performance of three different reconstruction attacks (HRec, Avg, MaxDiff) on three datasets (MNIST, Fashion MNIST, CIFAR10) and three model architectures. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of cosine similarity between the original and reconstructed samples is used to evaluate the performance. Lower CDF curves indicate better reconstruction accuracy. The results show that HRec consistently outperforms the other two attacks, particularly on the denser CIFAR10 dataset, highlighting its effectiveness in reconstructing deleted samples.

This figure compares the performance of three methods (HRec, Avg, MaxDiff) for reconstructing deleted samples in three image datasets (MNIST, Fashion MNIST, CIFAR10) using three different model architectures. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of cosine similarity scores is used to evaluate the accuracy of reconstruction. The lower the curve, the better the reconstruction method performs, indicating that HRec generally outperforms Avg and MaxDiff, particularly on the denser CIFAR10 dataset.

This figure shows the results of reconstructing CIFAR10 images after they were deleted from a logistic regression model. Three rows are shown for each image: the original deleted image, a reconstruction using the authors’ method (HRec), and a reconstruction using a perturbation baseline (MaxDiff). The HRec method is shown to produce reconstructions that are visually very similar to the original deleted images, suggesting that the attack is highly effective.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed reconstruction method (HRec) against a perturbation baseline (MaxDiff) on Fashion MNIST and MNIST datasets. For each dataset, a 40K parameter model (using cross-entropy loss with random Fourier features) was trained, and then one sample per class was deleted. The figure shows the original deleted samples, the reconstructions obtained by HRec, and the reconstructions obtained by MaxDiff. The results demonstrate that HRec produces significantly better reconstructions, which are visually very similar to the original deleted samples, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed method.

This figure compares the image reconstruction results of three methods: the proposed HRec method, a perturbation baseline (MaxDiff), and the original image. Rows 1 and 4 show the original deleted images from Fashion MNIST and MNIST datasets respectively. Rows 2 and 5 show the reconstructions using the HRec method, and rows 3 and 6 show reconstructions using the MaxDiff method. The results demonstrate that the HRec method produces reconstructions which are visually very similar to the original deleted images, significantly better than the MaxDiff baseline.

More on tables

This table presents the performance of different models (Ridge Regression, Logistic Regression, and Linear SVM) on American Community Survey (ACS) income data for three different states (NY, CA, TX). The performance is measured using R-squared (R2) for regression tasks and F1-score for classification tasks. The use of F1-score is justified by the class imbalance in the dataset. Additionally, the table shows results both with and without random fourier features.

This table shows the out-of-sample accuracy of three different models (Linear Cross-Entropy, RBF Ridge, and RBF Cross Entropy) on three image datasets (CIFAR10, MNIST, and Fashion MNIST). The accuracy represents the model’s performance on unseen data, indicating its generalization ability. Higher accuracy suggests better model performance and generalization.

Full paper#