↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

This research investigates whether causal language models can effectively solve complex logic puzzles, specifically Sudoku and Zebra puzzles. Existing studies show that large language models (LLMs) have impressive abilities on various tasks, but their true reasoning capabilities remain under debate. This work addresses this question by using LLMs to solve logic puzzles, which require a complex interaction of searching, applying strategies, and making deductions. The challenges lie in the complexity of the puzzles and ensuring accurate assessment of an LLM’s reasoning ability.

The study trains transformer models on carefully ordered solution steps for Sudoku puzzles, demonstrating that the model significantly improves its accuracy. Additionally, it is shown that the internal representation of the trained model implicitly encodes a “candidate set” of possible values, analogous to human reasoning. This extends to Zebra puzzles, showcasing that the successful LLM training relies on providing the correct sequence of solution steps rather than just the complete solution. The findings suggest that LLMs might have more advanced reasoning abilities than previously thought.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it demonstrates the surprising reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs), challenging the notion that LLMs merely mimic language rather than truly understanding and reasoning. It opens new avenues for research into LLM reasoning, including the investigation of training methods and the development of more robust and sophisticated reasoning tasks.

Visual Insights#

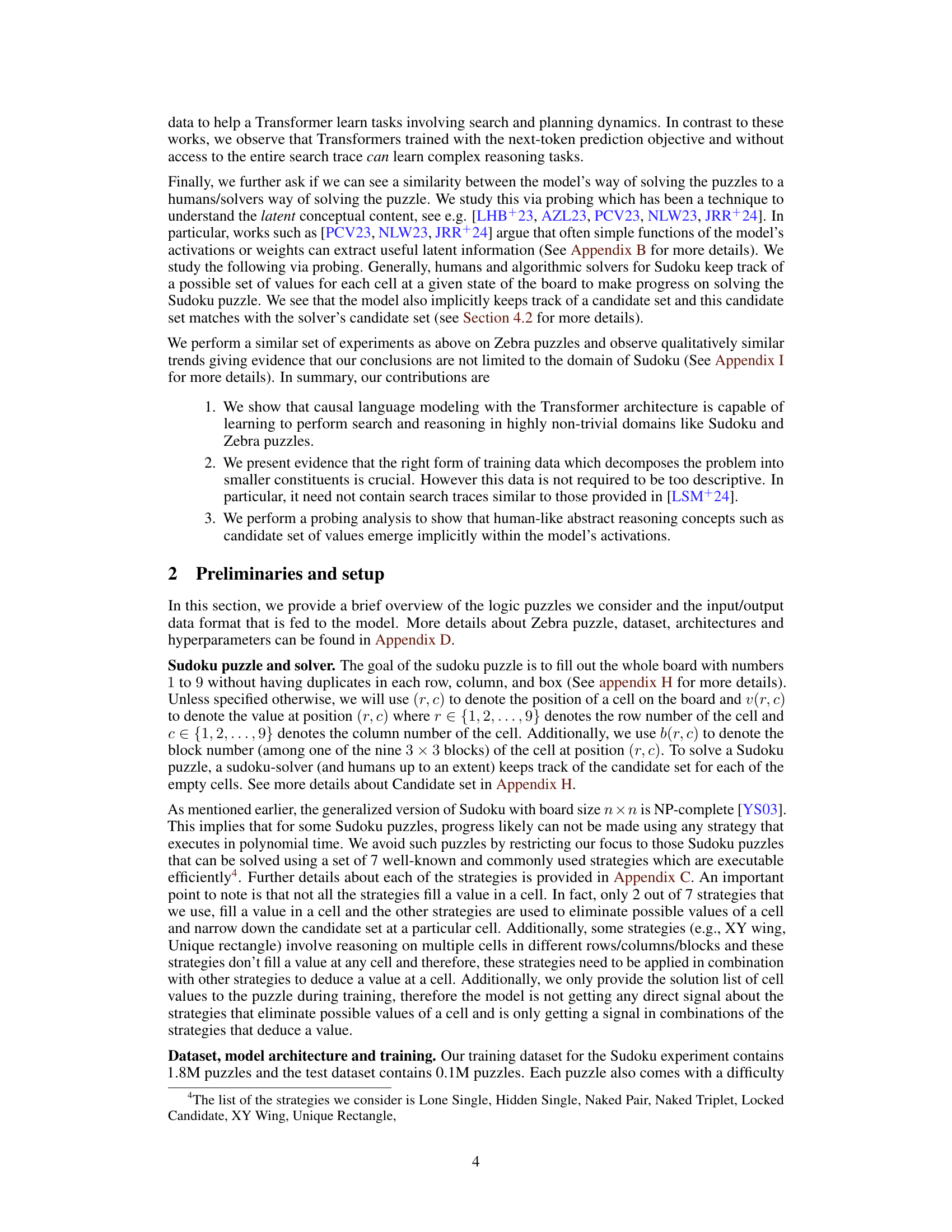

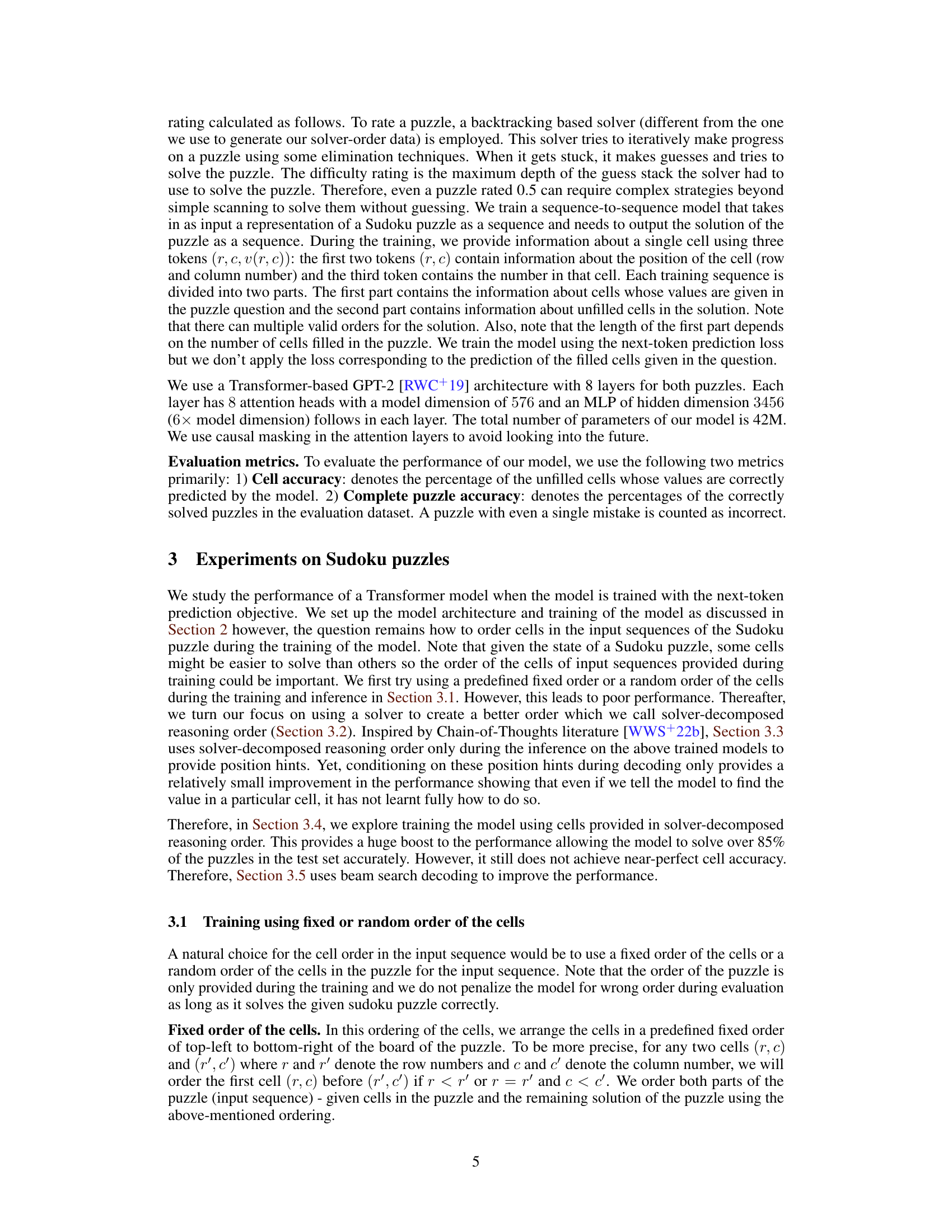

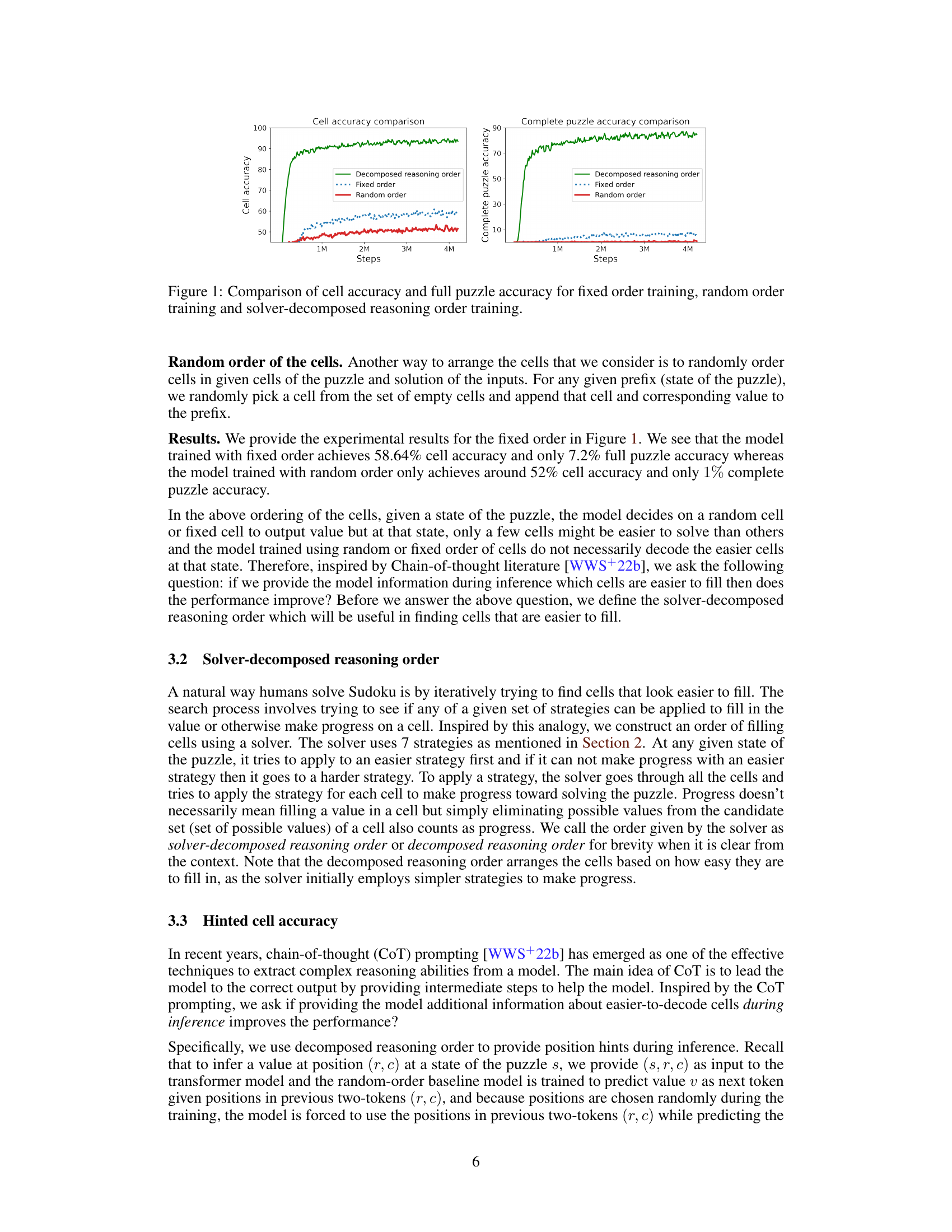

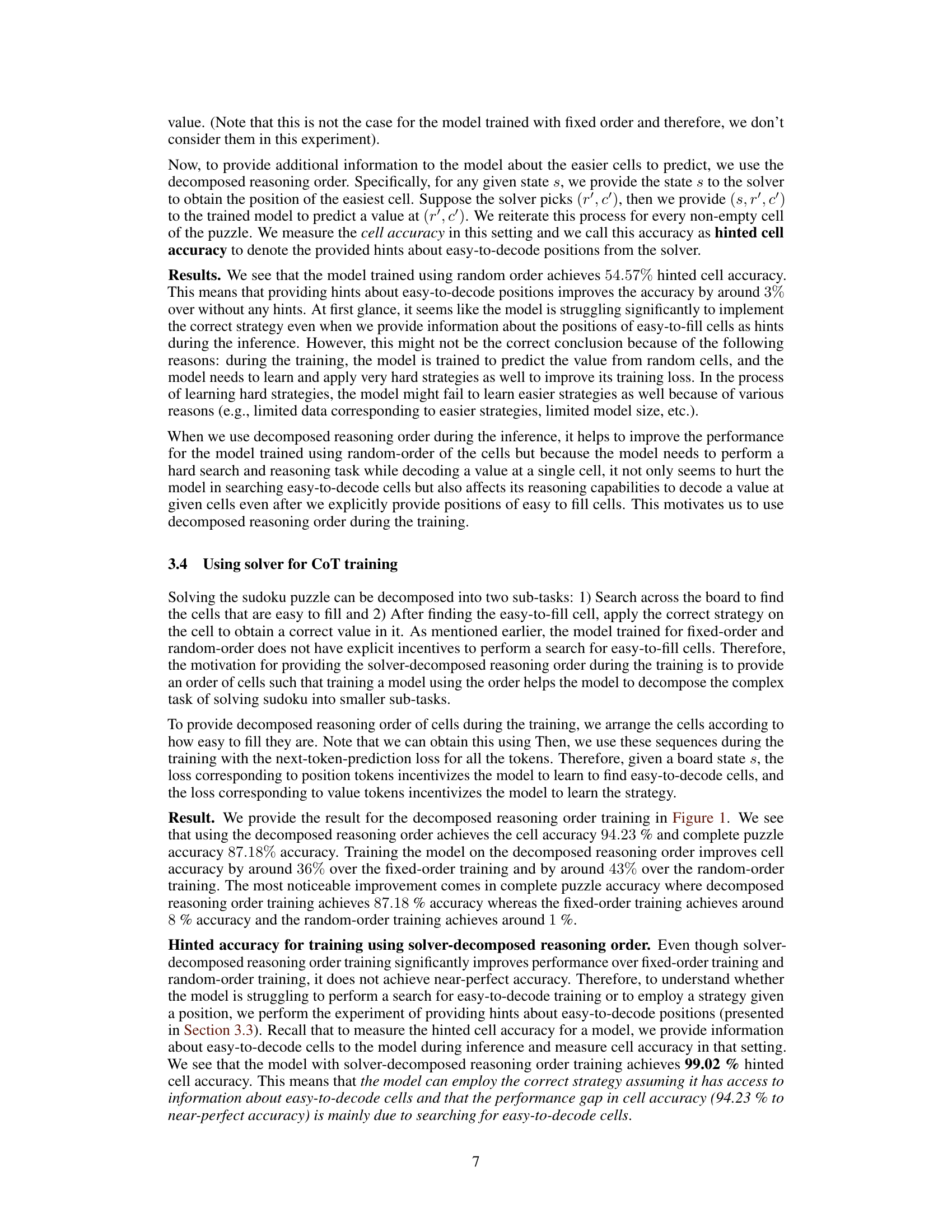

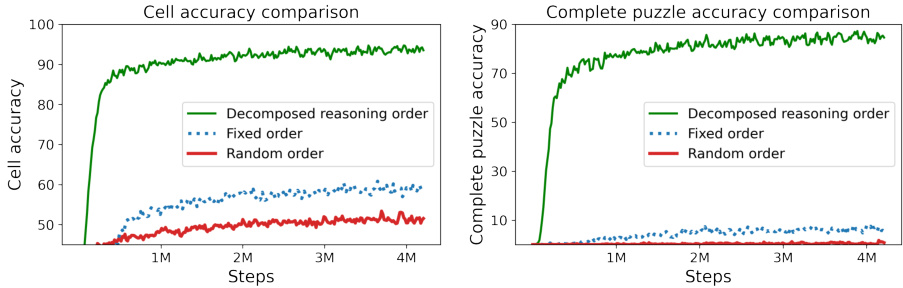

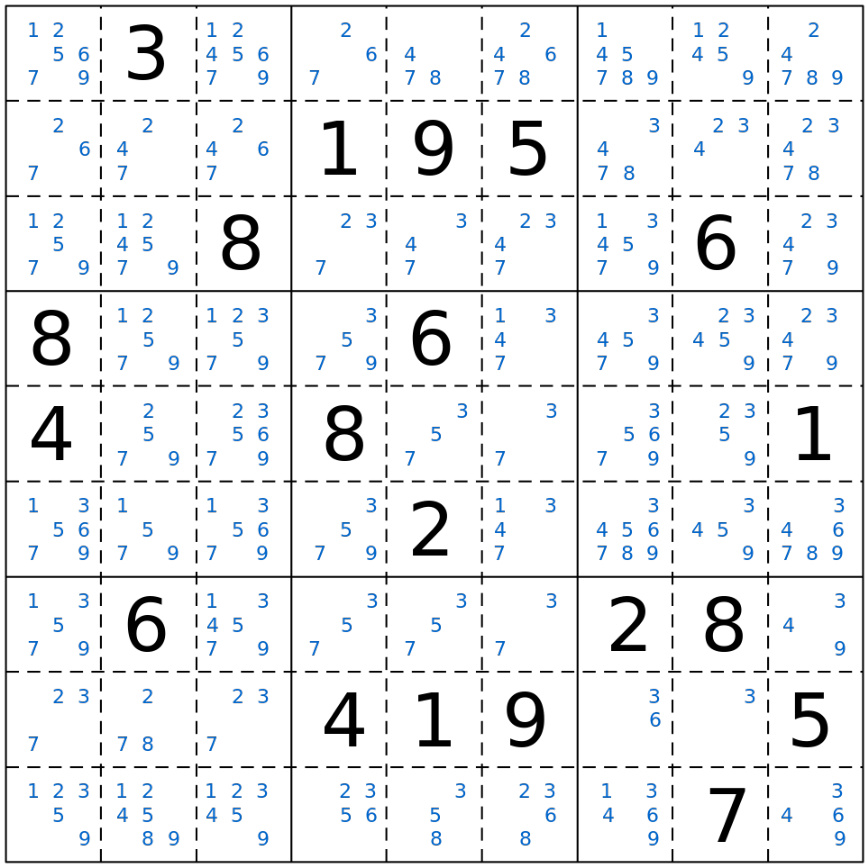

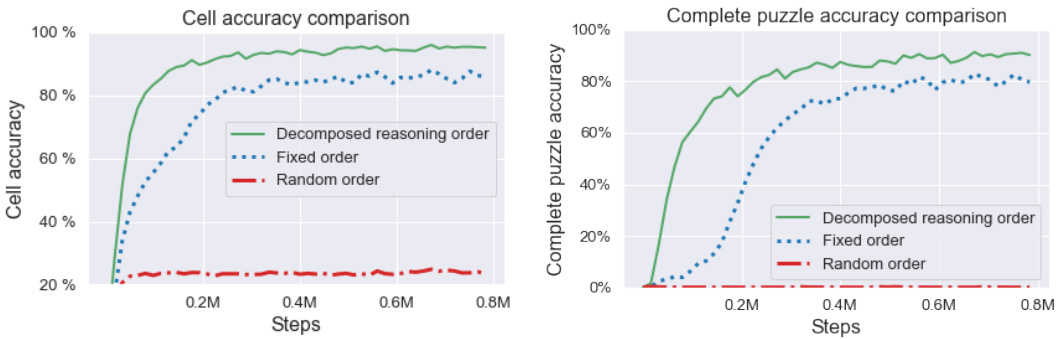

The figure shows the training curves for cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy using three different cell ordering methods during training: fixed order, random order, and solver-decomposed order. The solver-decomposed order, which uses a Sudoku solver to determine the order of cells, significantly outperforms the other two methods in both cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy. The plot demonstrates the impact of training data ordering on the model’s ability to learn complex reasoning strategies needed to solve Sudoku puzzles.

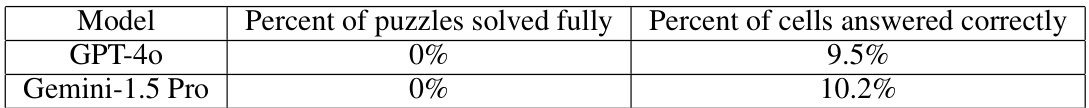

This table presents the results of a 4-shot Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting experiment on Sudoku puzzle solving using two state-of-the-art large language models (LLMs): GPT-4 and Gemini-1.5 Pro. The experiment evaluated the models’ ability to completely solve Sudoku puzzles and their accuracy in correctly filling individual cells. The results show that both models performed poorly, achieving 0% success in fully solving any puzzles, with cell accuracy only slightly above random guessing.

In-depth insights#

Causal LM Reasoning#

The concept of ‘Causal LM Reasoning’ explores how causal language models (LLMs), trained to predict the next token in a sequence, can exhibit reasoning abilities. The core idea is that the causal structure of language, where each word’s probability depends on preceding words, implicitly encodes logical relationships. This allows the model to solve complex tasks like logic puzzles by seemingly chaining together steps in a way that resembles human reasoning. However, it’s crucial to differentiate between true understanding and sophisticated pattern matching. While LLMs might achieve high accuracy, it remains a topic of debate whether this stems from genuine reasoning or clever prediction based on training data. The order of input information significantly influences performance, highlighting the dependence on structured, step-by-step guidance for successful reasoning. Techniques like chain-of-thought prompting help guide the model toward a more structured solution path, showcasing the potential of assisting LLMs to reason effectively, but also emphasizing the limits of solely relying on next-token prediction. Further research is needed to unravel the extent of true reasoning capabilities in LLMs and to design more effective training methods that promote genuine comprehension rather than merely predictive accuracy.

Sudoku Solver Order#

The concept of “Sudoku Solver Order” in the context of training transformer models for solving Sudoku puzzles is crucial. The paper highlights that simply training on puzzles with a fixed or random cell order leads to poor performance. Instead, utilizing a solver to determine the order in which cells are filled proves highly effective. This “solver-decomposed reasoning order” allows the model to learn a more strategic approach, breaking down the complex task into smaller, more manageable sub-tasks. This approach mimics how a human might solve Sudoku, focusing on easier cells first and progressively building the solution. The success of this method underscores the importance of providing the model with informative training data that reflects the steps involved in effective problem-solving, rather than just the final solution. Ultimately, this structured training methodology demonstrates a significant improvement in the model’s ability to solve complete Sudoku puzzles, highlighting the impact of well-crafted training data on complex reasoning tasks.

Chain-of-Thought#

The concept of Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting is a significant advancement in prompting techniques for large language models (LLMs). CoT guides the LLM through intermediate reasoning steps, moving beyond simple word prediction to elicit more complex and accurate responses. The approach involves augmenting prompts with explicit reasoning steps, thereby prompting the model to articulate its thought process before arriving at a final answer. This technique significantly boosts the performance of LLMs on tasks requiring logical reasoning and problem-solving. CoT’s success stems from its ability to break down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable sub-problems, enabling the model to chain together simpler inferences and reduce the likelihood of errors. While effective, CoT prompting is not without limitations. It can be computationally expensive and requires carefully crafted prompts. The effectiveness of CoT heavily depends on the task’s structure and the quality of the intermediate reasoning steps provided. Future research should focus on improving CoT’s efficiency and exploring its applicability across diverse tasks, possibly by automatically generating the necessary reasoning steps.

Internal Representations#

Analyzing a model’s internal representations is crucial for understanding its decision-making process. In the context of solving logic puzzles, probing these representations can reveal whether the model genuinely reasons or merely simulates reasoning. Linear probing, for instance, could examine whether the model’s internal activations encode information about the possible values for each cell, a key aspect of human-like Sudoku solving. If successful, this would suggest a strong reasoning engine, as the model implicitly maintains and updates the candidate sets similar to human solvers. Failure to find such representations might indicate the model relies on simpler pattern matching or memorization techniques rather than true reasoning. Investigating the specific internal representations utilized by the model could provide insights into the nature of its reasoning capabilities and its limitations. The architecture of the internal representations, whether distributed or localized, could further shed light on the model’s learning process and its potential to handle variations in puzzle complexity.

Future Work#

The paper’s results suggest several promising avenues for future research. Extending the model’s capabilities to more complex, real-world logic puzzles beyond Sudoku and Zebra puzzles is crucial. This might involve datasets with richer, less structured constraints and more nuanced reasoning pathways. Investigating the model’s performance on puzzles requiring creative problem-solving, rather than just constraint satisfaction, would reveal its true reasoning depth. Additionally, exploring the use of different model architectures or training paradigms to improve efficiency and scalability is warranted. Incorporating explicit mechanisms to guide search efficiently, potentially mimicking human solution strategies, is another direction for improvement. Finally, more in-depth probing analyses to further uncover the model’s internal representations and reasoning processes are necessary to understand its decision-making. This would include exploring higher-level cognitive representations beyond candidate sets.

More visual insights#

More on figures

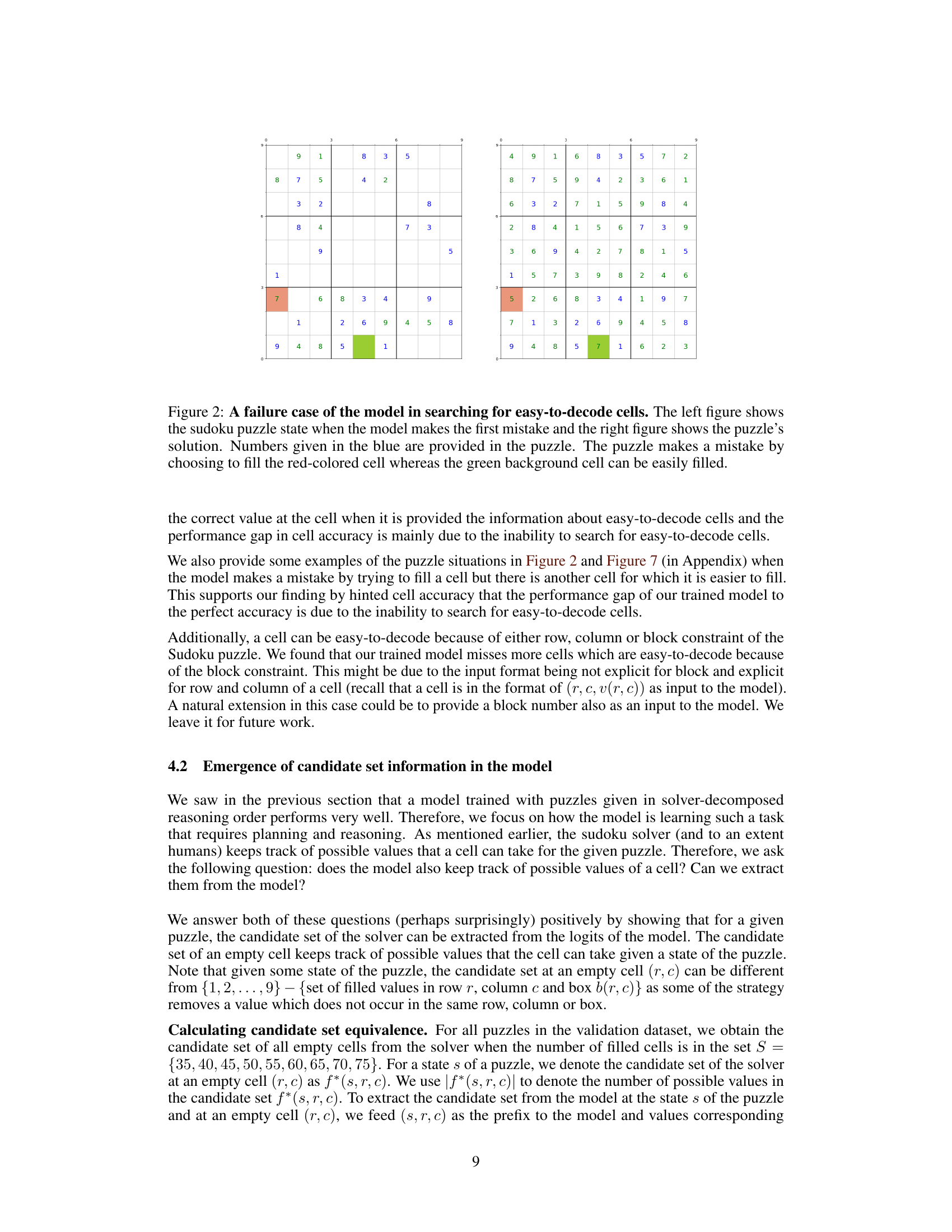

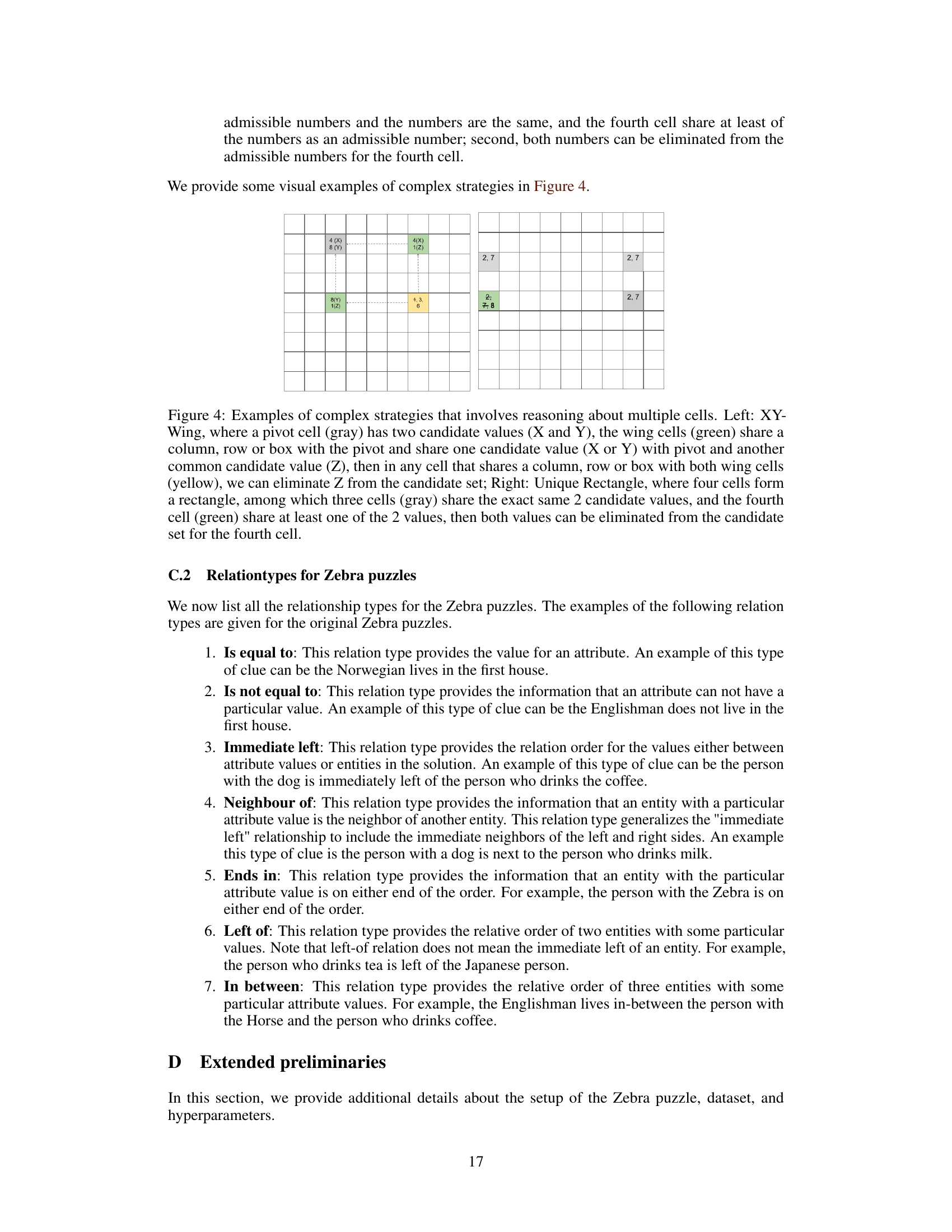

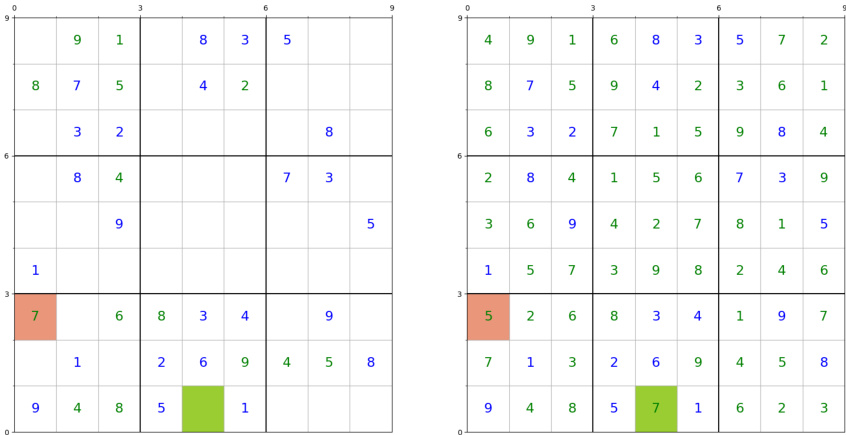

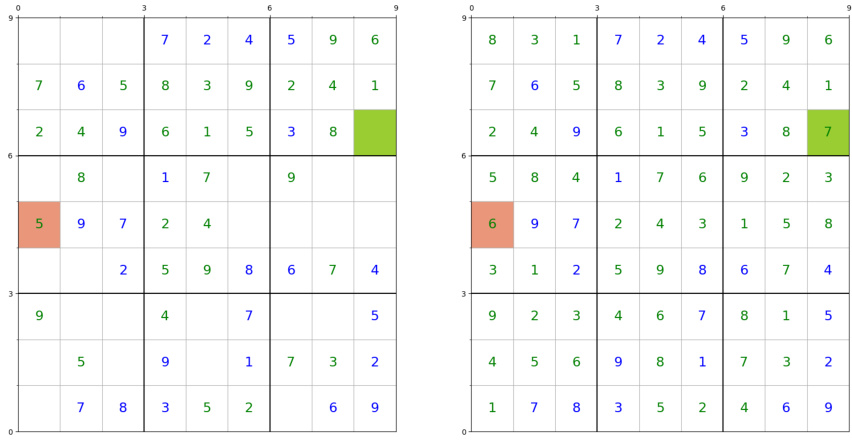

This figure shows a failure case of the model’s ability to find easy-to-decode cells. The left panel depicts the puzzle state where the model made its first mistake (red cell). The right panel shows the correct solution. Notice that a different cell (green cell) would have been an easier choice for the model.

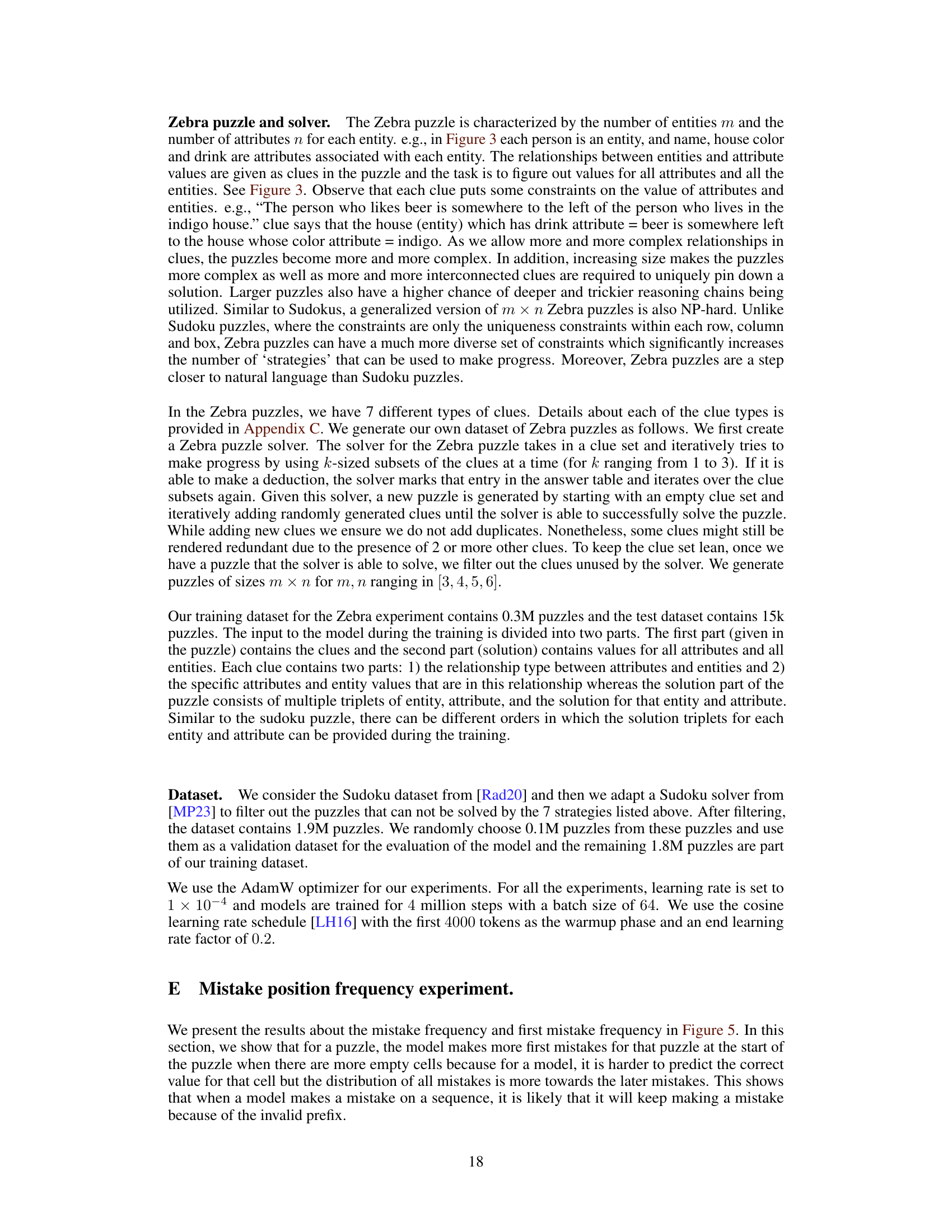

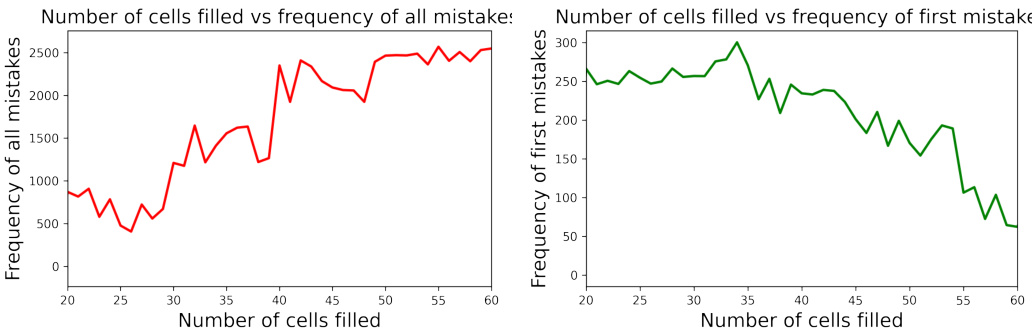

This figure shows two plots. The left plot shows the total number of mistakes made against the number of cells that had been filled when the mistakes were made. The right plot shows the number of times a model made its first mistake against the number of cells filled at the time of the first mistake. Both plots aim to visualize the relationship between the number of mistakes made and the number of cells filled in a Sudoku puzzle. It is intended to show how the difficulty in finding the correct value increases as the number of unfilled cells decreases (i.e., more mistakes are made near the end).

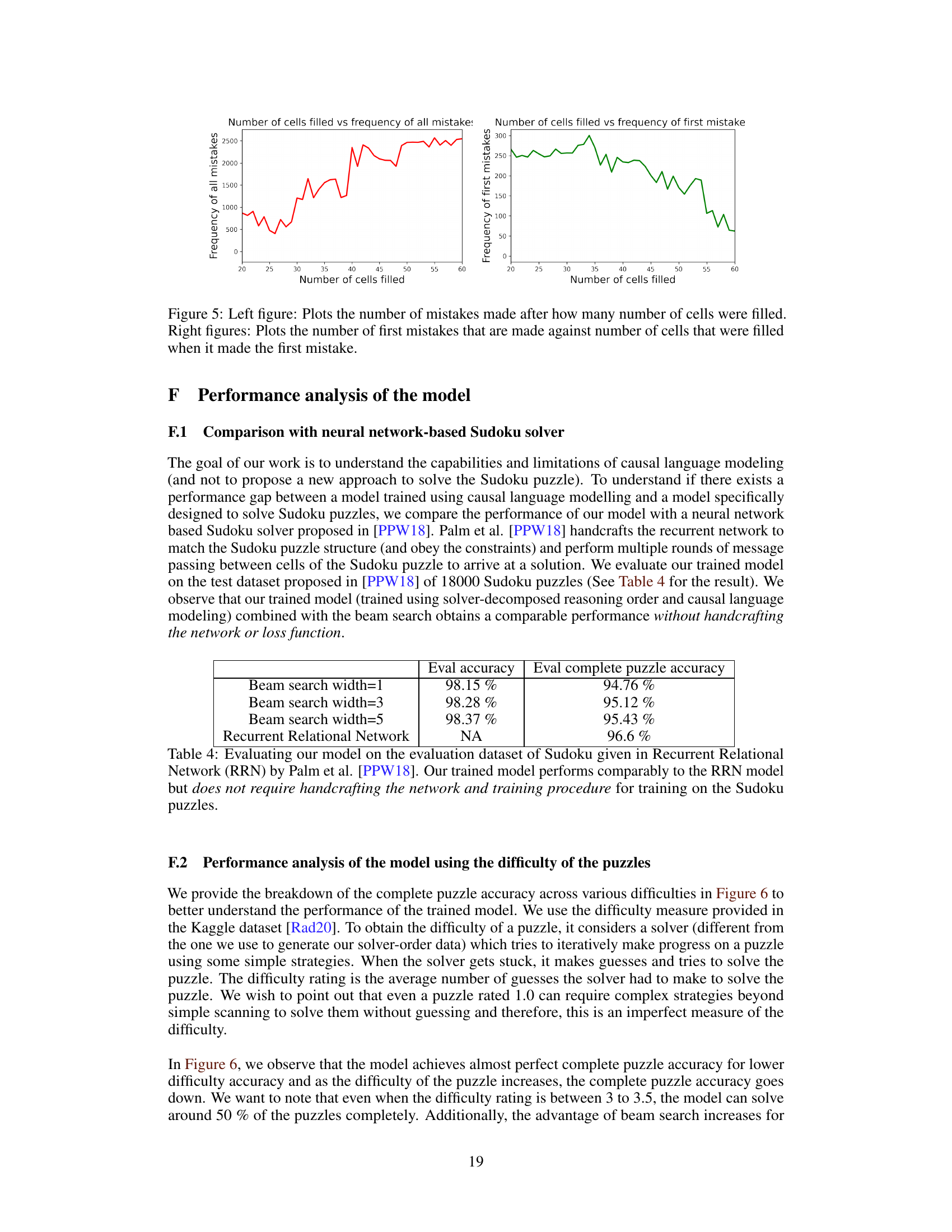

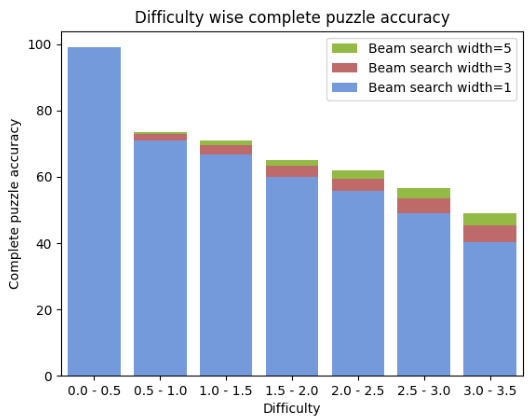

This figure shows the complete puzzle accuracy for Sudoku puzzles of varying difficulty levels. The difficulty is measured by the number of guesses a solver needed to solve the puzzle. The figure compares the complete puzzle accuracy for three different beam search widths (1, 3, and 5). It demonstrates how the accuracy decreases as the puzzle difficulty increases, indicating that the model struggles more with harder puzzles. The beam search width also impacts accuracy, with larger widths generally leading to better performance but at increased computational cost.

This figure shows a failure case of the model’s search for easy-to-decode cells in a Sudoku puzzle. The left panel displays the puzzle state where the model makes its first mistake, highlighting the incorrectly filled cell in red. The right panel shows the correct solution, indicating a readily solvable cell (in green) that the model missed. The blue numbers represent the initially given values in the puzzle.

This figure shows an example where the model fails to identify an easy-to-solve cell in a Sudoku puzzle. The left panel displays the puzzle state when the model makes its first mistake, while the right panel shows the correct solution. Cells with numbers in blue are pre-filled in the puzzle, the model incorrectly fills the red cell, while the green cell represents a much easier choice to solve.

This figure compares the performance of three different training methods for a Sudoku-solving model: fixed order, random order, and solver-decomposed reasoning order. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, while the y-axis shows both the cell accuracy (percentage of correctly predicted values in individual cells) and the complete puzzle accuracy (percentage of fully solved puzzles). The plot reveals a substantial performance gap between the solver-decomposed approach and the other two methods, highlighting the importance of providing the model with a strategically ordered sequence of cells during training.

This figure shows the comparison of cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy for three different training methods: fixed order, random order, and solver-decomposed order. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, while the y-axis shows the accuracy. The solver-decomposed order significantly outperforms both the fixed and random order approaches in terms of both cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy.

More on tables

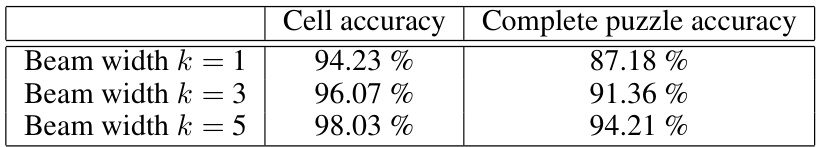

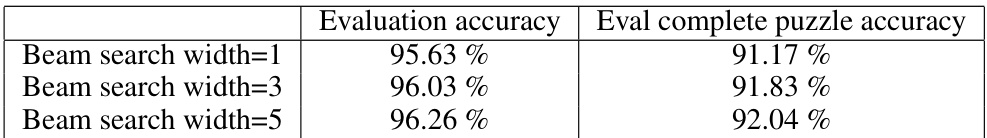

This table shows the performance of the model in terms of cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy when using beam search with different beam widths (k=1, 3, and 5). The results demonstrate how increasing the beam width improves both cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy, suggesting that exploring multiple hypotheses during decoding enhances the model’s ability to solve Sudoku puzzles.

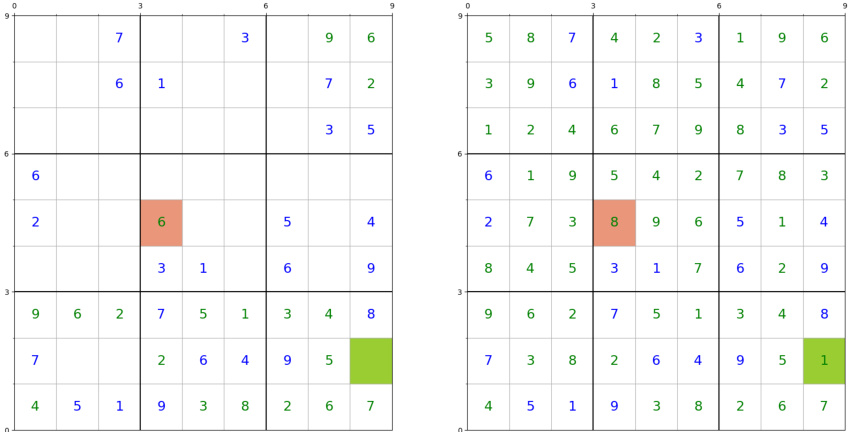

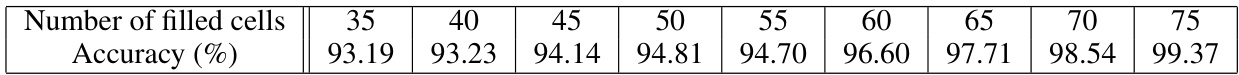

This table presents the accuracy of candidate set equivalence for different numbers of filled cells in Sudoku puzzles. The accuracy represents the average overlap between the candidate sets generated by a human solver and the model’s predictions for correctly solved puzzles. The more filled cells, the higher the accuracy, indicating improved agreement between the solver and the model.

This table presents the results of an experiment to evaluate the impact of beam width on the performance of a model trained to solve Sudoku puzzles. The experiment measures two performance metrics: cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy. Cell accuracy refers to the percentage of cells that are correctly filled in the puzzle, whereas complete puzzle accuracy refers to the percentage of puzzles which are fully solved correctly (without any mistakes). The table shows that increasing the beam width improves both cell accuracy and complete puzzle accuracy.

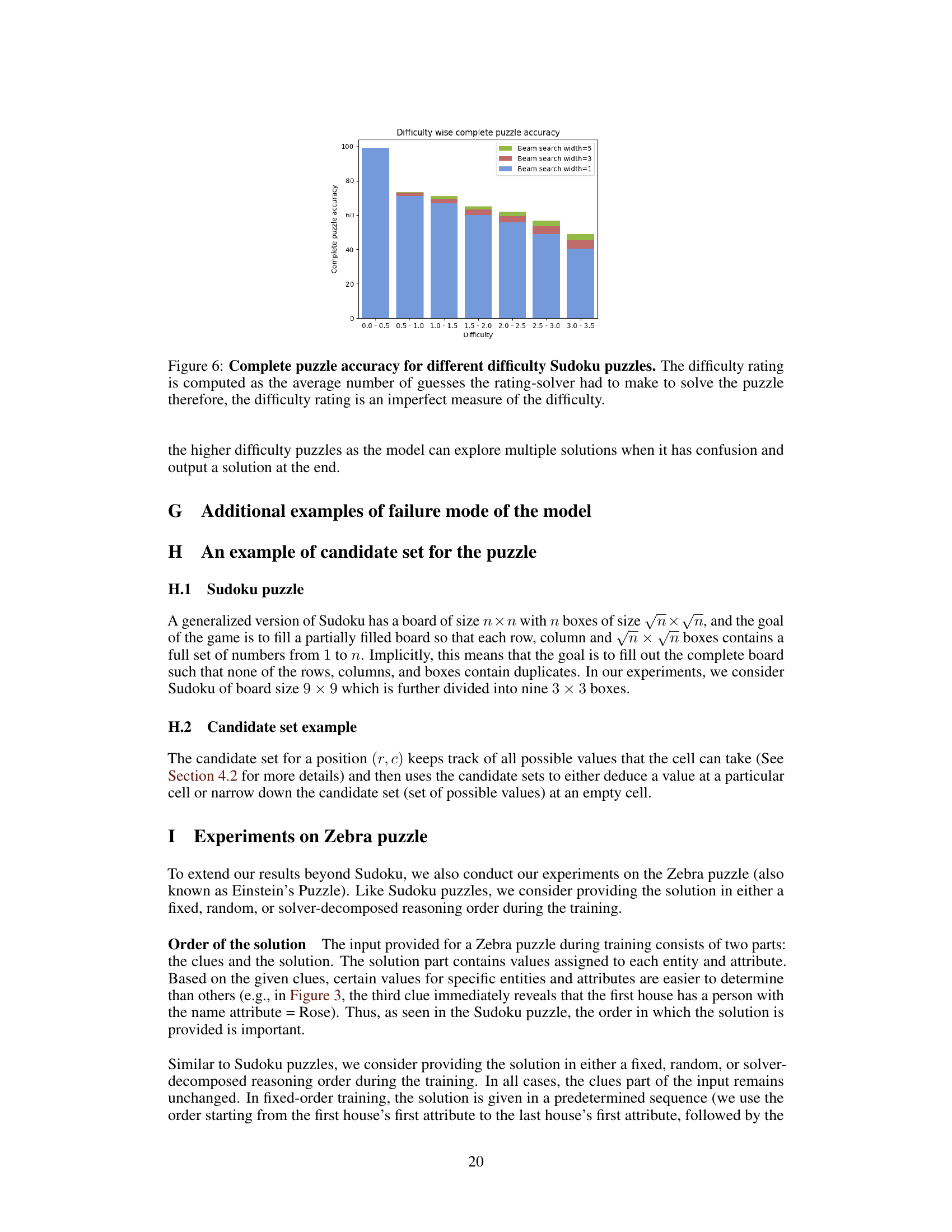

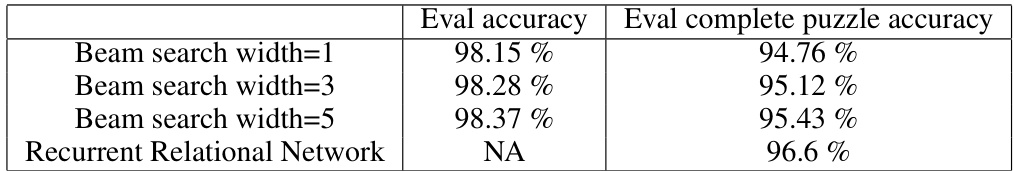

This table compares the performance of the proposed causal language model on Sudoku puzzles with a neural network-based Sudoku solver from prior work. The comparison focuses on evaluation accuracy (percentage of correctly solved cells) and complete puzzle accuracy (percentage of fully correctly solved puzzles). It highlights that the language model achieves comparable results without requiring the architecture-specific design or training of the neural network approach.

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on Zebra puzzles. It shows the evaluation accuracy (percentage of correctly predicted attributes) and complete puzzle accuracy (percentage of completely and correctly solved puzzles) for different beam search widths (1, 3, and 5). The training data consisted of 320,000 Zebra puzzles with varying numbers of entities and attributes, generated to ensure solvability. The model’s performance is evaluated on a separate test set of 15,000 puzzles.

Full paper#