↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Designing peptides with desired properties is crucial for drug discovery but challenging due to the vast conformational space and complex interactions with target proteins. Existing methods often struggle with either efficiency or focus solely on sequence design, neglecting the crucial 3D structure. Furthermore, current diffusion models aren’t well-suited for full-atom peptide representations and variable binding site geometries.

This work introduces PepGLAD, a generative model using geometric latent diffusion. PepGLAD tackles these challenges by employing a variational autoencoder to handle the full-atom detail, and uses a receptor-specific affine transformation to normalize binding geometries. The results show that PepGLAD generates significantly more diverse and higher-affinity peptides compared to existing methods, improving both sequence-structure co-design and the generation of binding conformations. The benchmark dataset and the proposed method offer a significant advancement in peptide design, potentially speeding up drug discovery and therapeutic development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to peptide design using geometric latent diffusion, a method that significantly improves the diversity and binding affinity of generated peptides. It addresses limitations of existing methods by handling full-atom geometry and variable binding site shapes. This opens avenues for more efficient drug discovery and the development of new therapeutics.

Visual Insights#

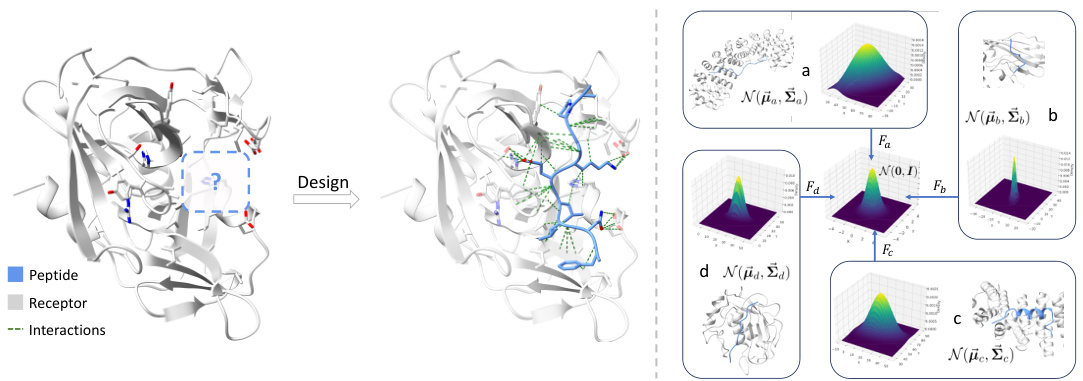

The figure illustrates the challenge of peptide design. The left panel shows that peptides must interact compactly with the receptor’s binding site, necessitating efficient exploration of a vast sequence-structure space. The right panel highlights the variability in binding site geometry across different examples (a-d). These sites have varying shapes and locations, represented as different 3D Gaussian distributions. The paper proposes using an affine transformation derived from the binding site’s geometry to standardize this variability and make it easier to learn with a generative model.

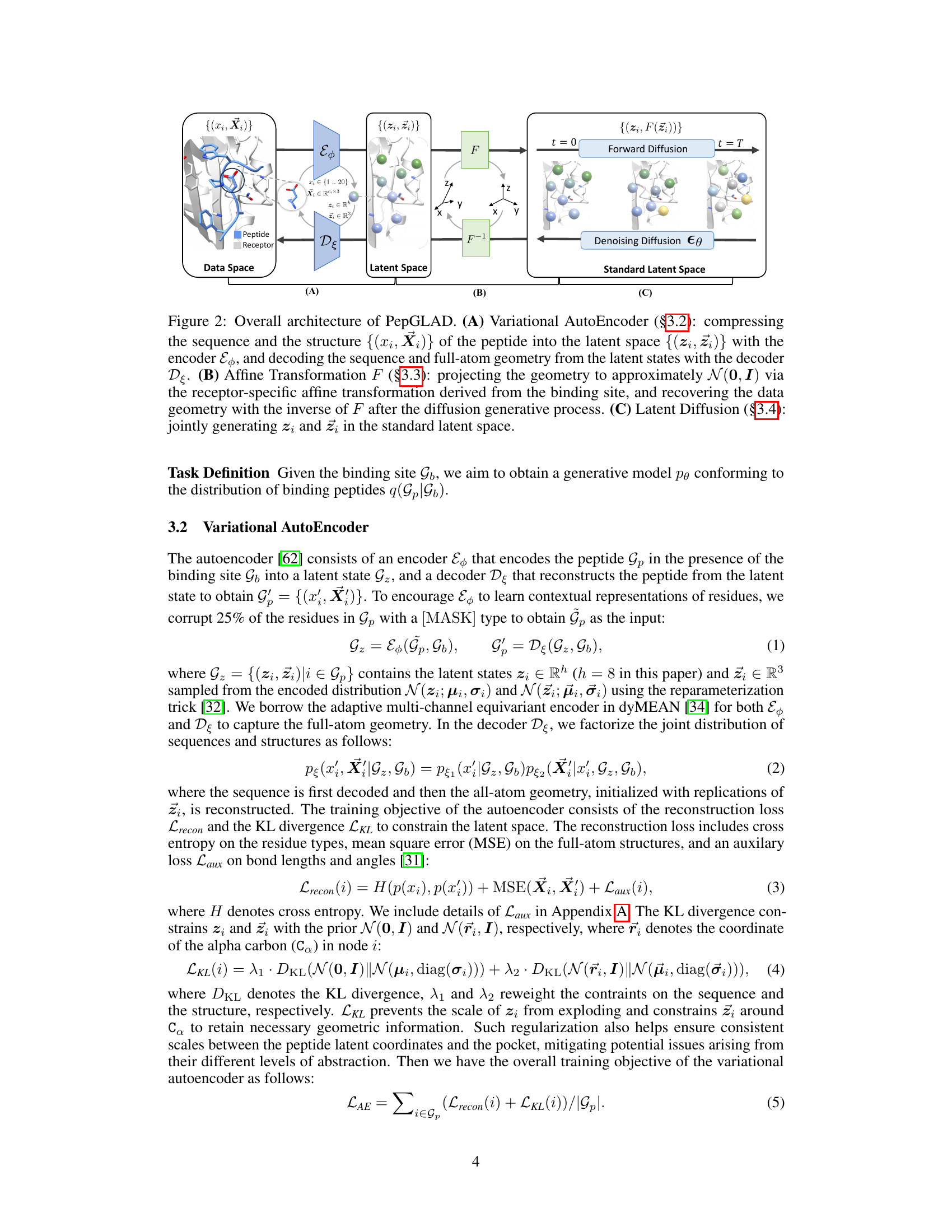

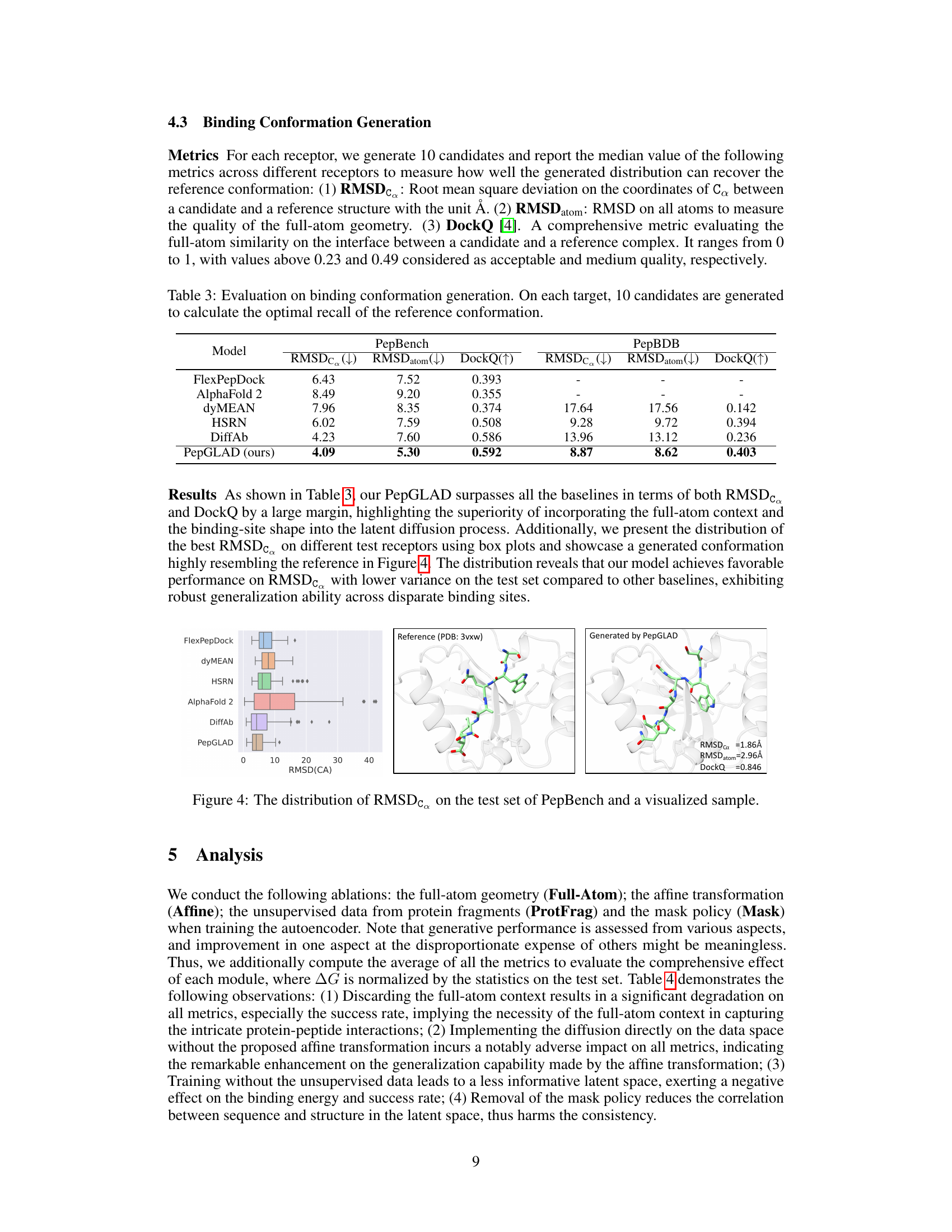

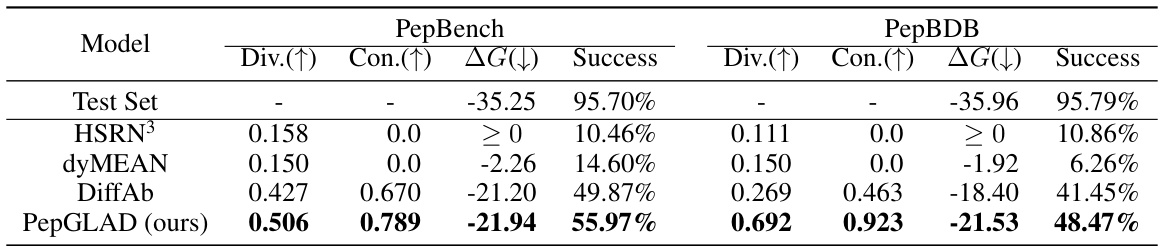

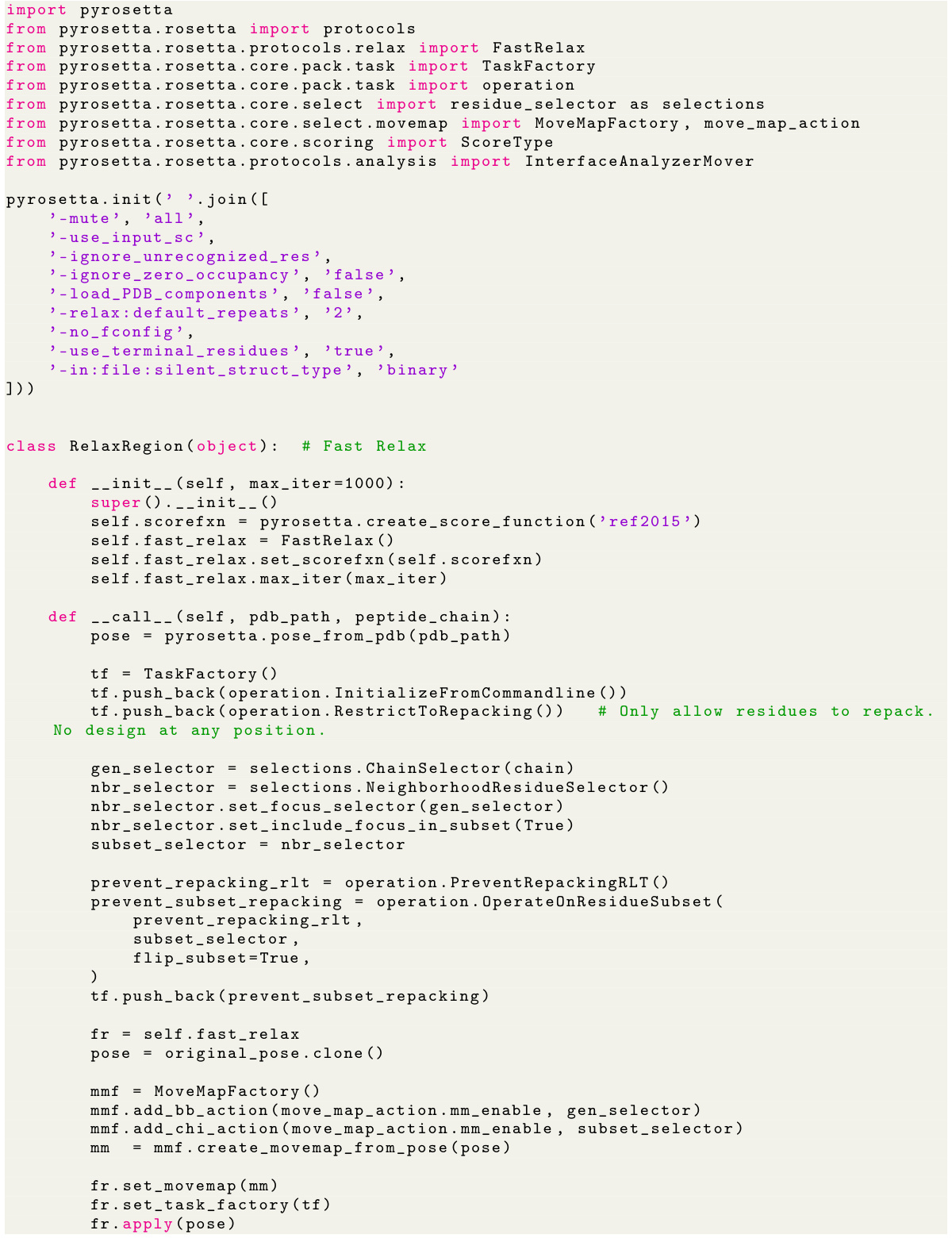

This table presents the results of a sequence-structure co-design experiment comparing PepGLAD against several baselines. For each model, the diversity (Div) of generated sequences and structures, the consistency (Con) between sequences and structures, the average binding energy (△G), and the success rate (percentage of candidates with no atomic clashes) are reported for both the PepBench and PepBDB datasets. Higher diversity, consistency, and success rate, along with lower binding energy, indicate better model performance.

In-depth insights#

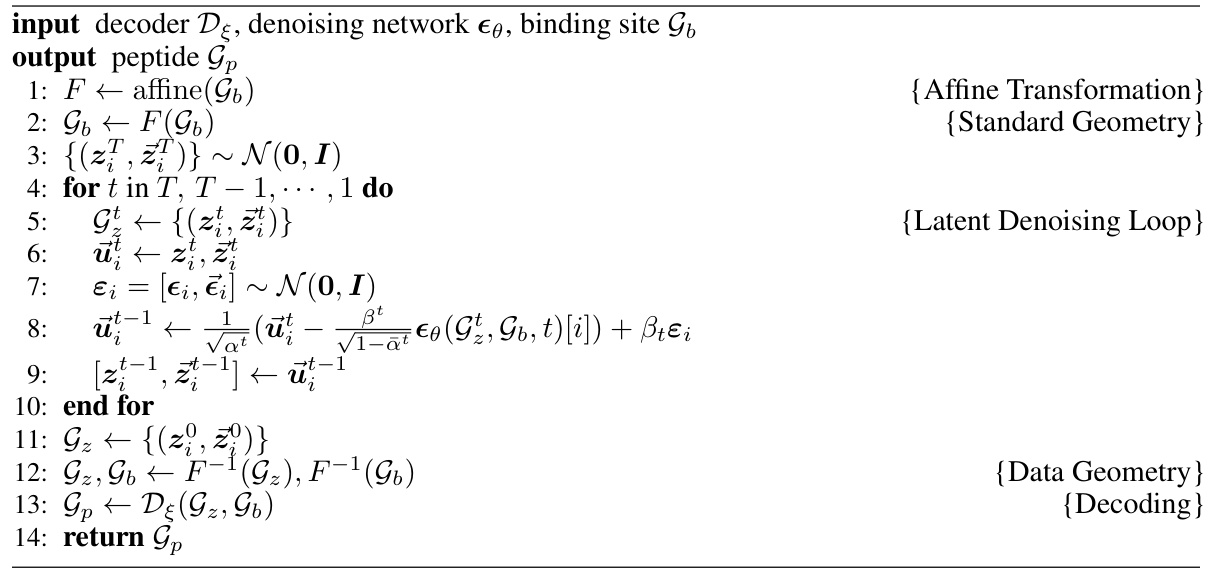

PepGLAD: Method#

The PepGLAD method section would detail a novel generative model for peptide design, likely using a diffusion-based approach. It would likely leverage a variational autoencoder (VAE) to compress full-atom residue representations into a lower-dimensional latent space, addressing the challenge of variable residue sizes. A key innovation would be the use of a receptor-specific affine transformation to map 3D coordinates into a shared standard space, improving generalization across various binding sites. The method would then apply a diffusion process within this standardized latent space, followed by decoding to reconstruct the full-atom peptide structure. The section would conclude with a discussion of training procedures and sampling strategies, likely involving a denoising process and possibly techniques to maintain peptide chain connectivity during generation. The overall goal would be to enable generation of peptides with diverse sequences and structures optimized for binding to specific receptors.

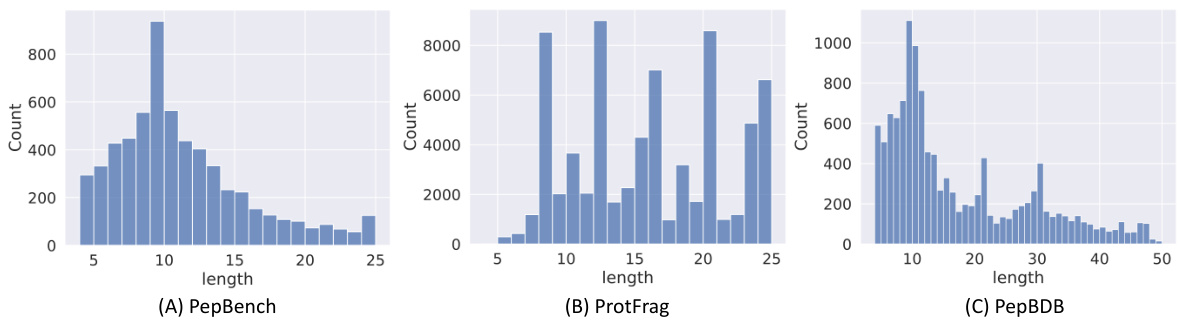

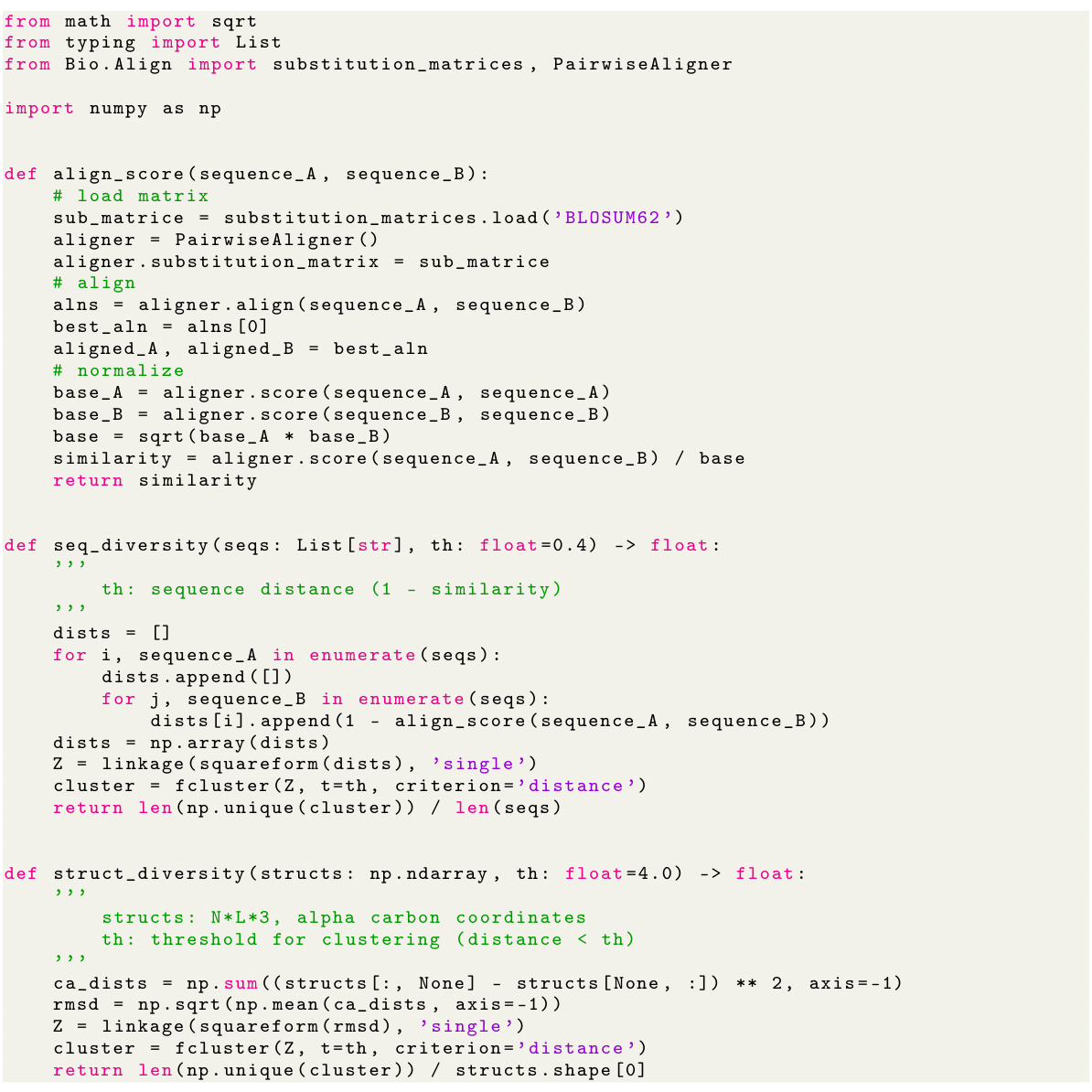

Benchmarking Peptides#

Creating a robust benchmark for peptide design is crucial due to the vast conformational space and the lack of standardized evaluation metrics. A proper benchmark should encompass diverse peptide sequences and structures, ideally spanning various lengths, amino acid compositions, and binding affinities. It should also consider the target proteins, ensuring representation of different binding sites and interaction characteristics. The selection of peptides for benchmarking must be non-redundant and representative of practically relevant scenarios, avoiding bias towards easily designable peptides. Systematic evaluation should involve multiple metrics, including binding affinity (e.g., using various scoring functions), specificity, and structural similarity to reference structures. Furthermore, the benchmark should allow for comparison across different design methodologies and computational approaches. A well-defined benchmark will accelerate the development and validation of novel peptide design techniques, facilitating progress in drug discovery, materials science, and other relevant fields. Publicly available datasets and standardized evaluation procedures are essential to enable fair comparison and broader adoption of new methodologies.

Affine Transformation#

The application of affine transformations in the context of protein-peptide interactions represents a novel approach to address the challenge of variable binding geometries. Standard diffusion models often struggle with diverse binding site shapes, leading to poor generalization. The affine transformation, derived from the binding site’s covariance and center, maps the 3D coordinates into a shared standard space, essentially standardizing the binding site shapes. This standardization allows the diffusion process to learn a more generalizable representation, improving the model’s capability to generate diverse and accurate peptides that effectively interact with various target proteins. This technique is crucial for enhancing transferability across different binding sites and is a significant contribution towards robust peptide design.

Full-Atom Geometry#

Modeling full-atom geometry in peptides presents significant challenges due to the variable size and composition of amino acid residues. Existing methods often simplify this complexity by focusing on backbone representations, losing crucial information about side-chain interactions. A variational autoencoder (VAE) is a powerful tool for addressing this issue. By encoding the full-atom coordinates into a fixed-dimensional latent space, the VAE allows a more manageable representation of the peptide, while still capturing essential geometric details. However, maintaining the full-atom geometry during the diffusion process is critical for generating functional peptides. Furthermore, the receptor-specific affine transformation helps to effectively handle the highly diverse binding geometries found in protein-peptide interactions, facilitating generalization to unseen receptor structures. Therefore, a combined approach, like using a VAE and a receptor-specific transformation, is essential for capturing the nuances of full-atom geometry in peptide design.

Future Directions#

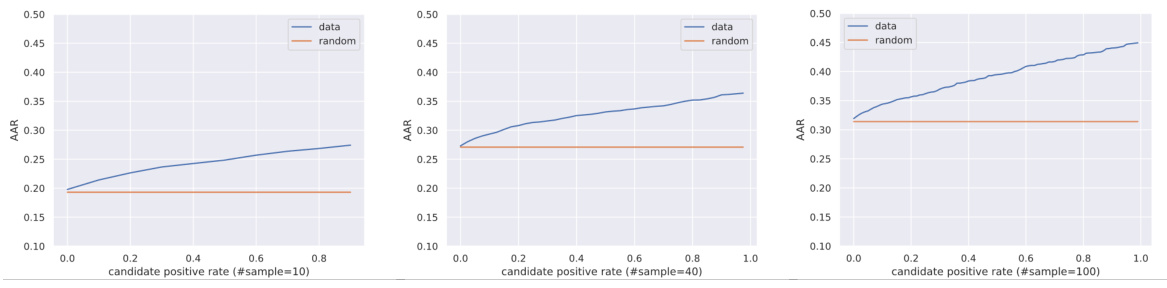

Future research directions stemming from this peptide design work could involve several key areas. Improving the accuracy of binding affinity prediction is crucial, perhaps through incorporating more sophisticated scoring functions or integrating experimental data. Addressing the challenges of larger peptides and more complex protein-peptide interactions would require enhanced computational techniques and possibly new generative model architectures. Exploring the application of PepGLAD to other molecule types, such as antibody design or small molecule drug discovery, is a promising avenue. Furthermore, investigating the impact of different training data and augmentation strategies on model performance and generalizability warrants attention. Finally, developing more efficient sampling techniques that reduce computational cost is essential for real-world applications. These advancements would broaden the potential of generative models in drug discovery and related fields.

More visual insights#

More on figures

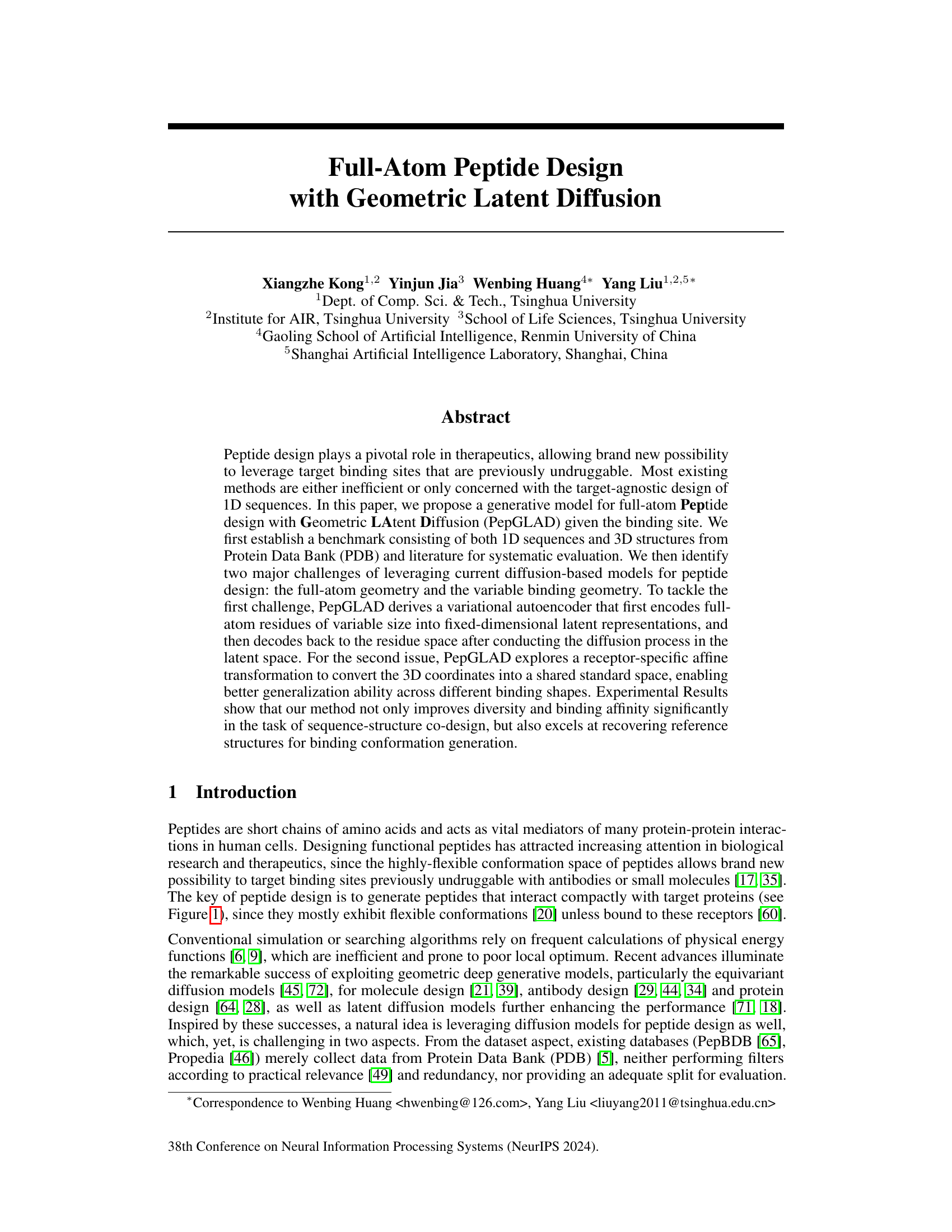

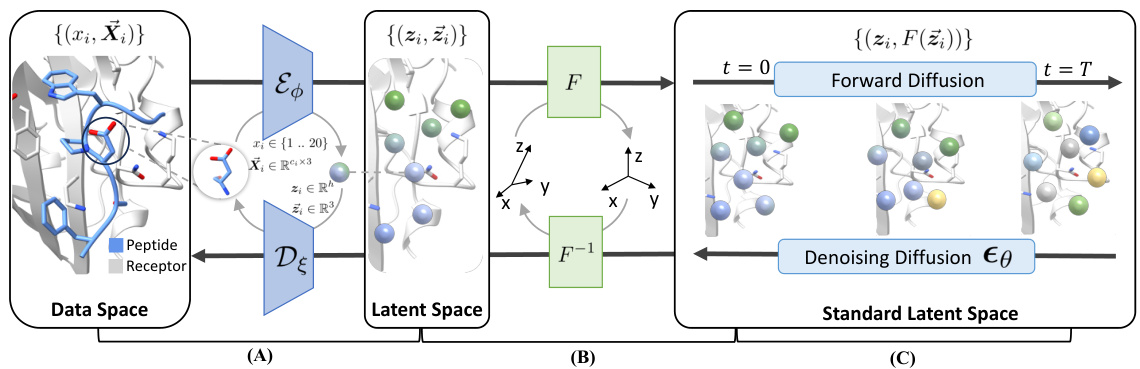

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the PepGLAD model, showing the three main modules: a variational autoencoder that compresses peptide sequence and structure into a latent space; a receptor-specific affine transformation that projects the geometry into a standard space; and a latent diffusion model that generates the peptide in this standard latent space. The figure shows the flow of data through the three modules, starting with the peptide and receptor in the data space, progressing through the latent space, and finally to the standard latent space where the diffusion process occurs. The different stages of the diffusion process are also visually represented.

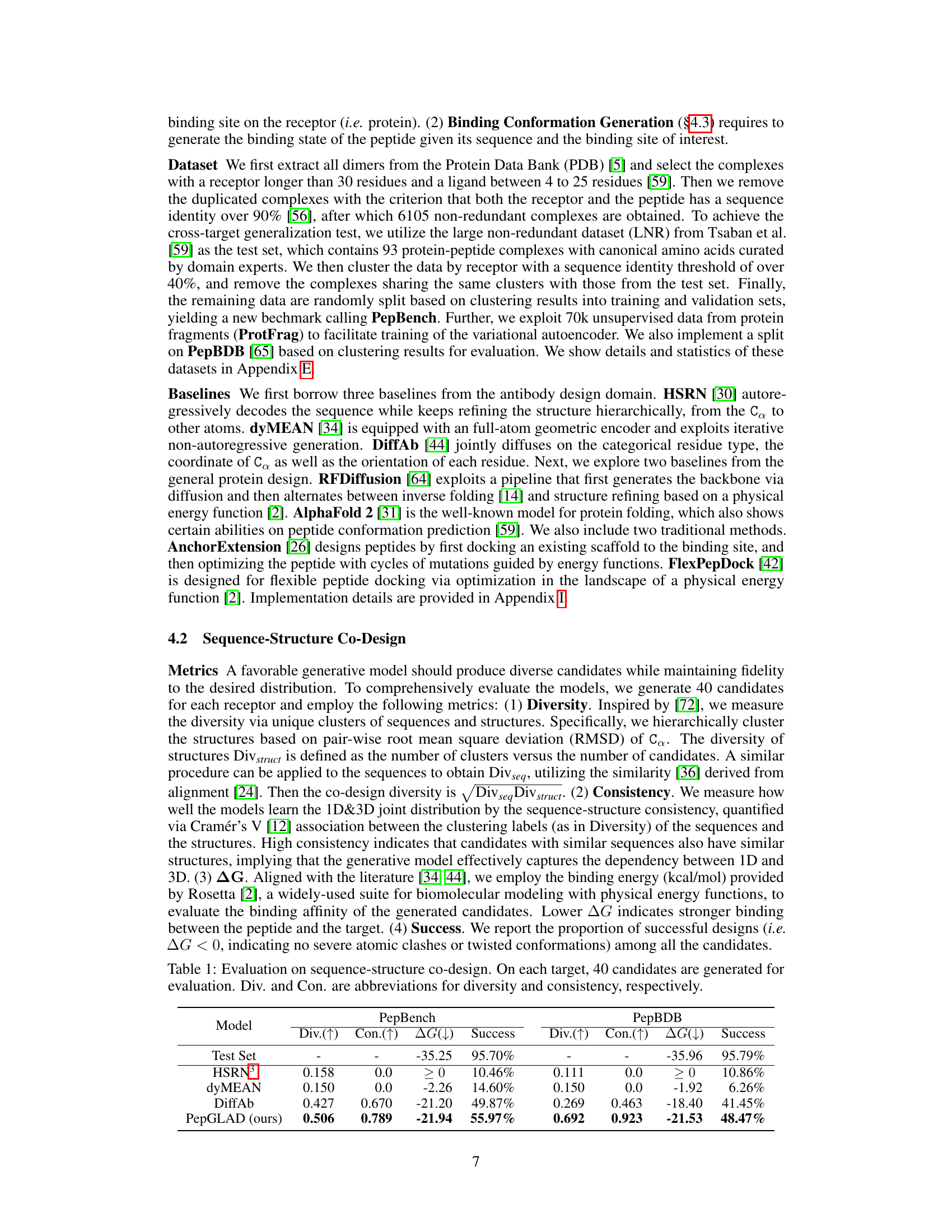

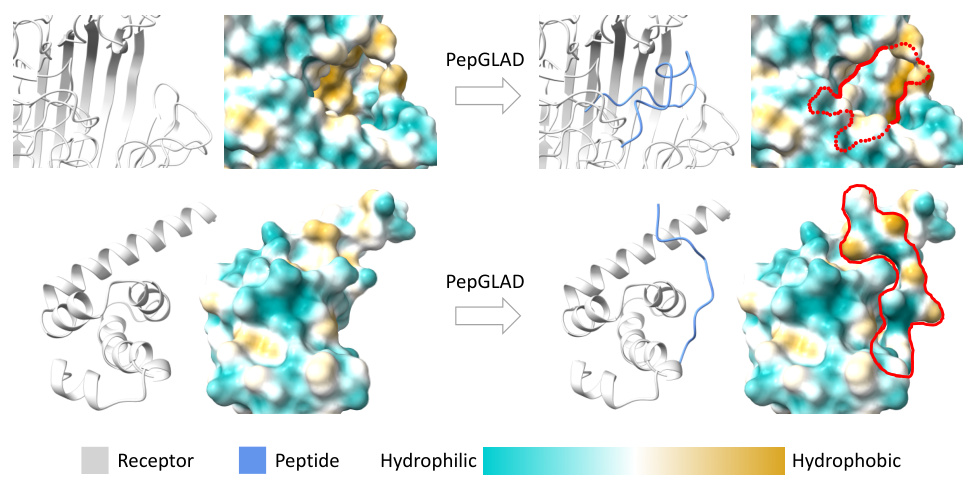

This figure showcases two example peptides generated by the PepGLAD model. The top panel shows a peptide that fits snugly within the binding site of a receptor (PDB ID: 4cu4), demonstrating a compact interaction. The bottom panel presents a peptide whose shape complements the binding site of a different receptor (PDB ID: 3pkn), again showcasing a successful binding conformation. Both examples highlight the model’s ability to generate peptides with favorable binding affinities (indicated by negative ∆G values), and its capacity for generating diverse binding conformations.

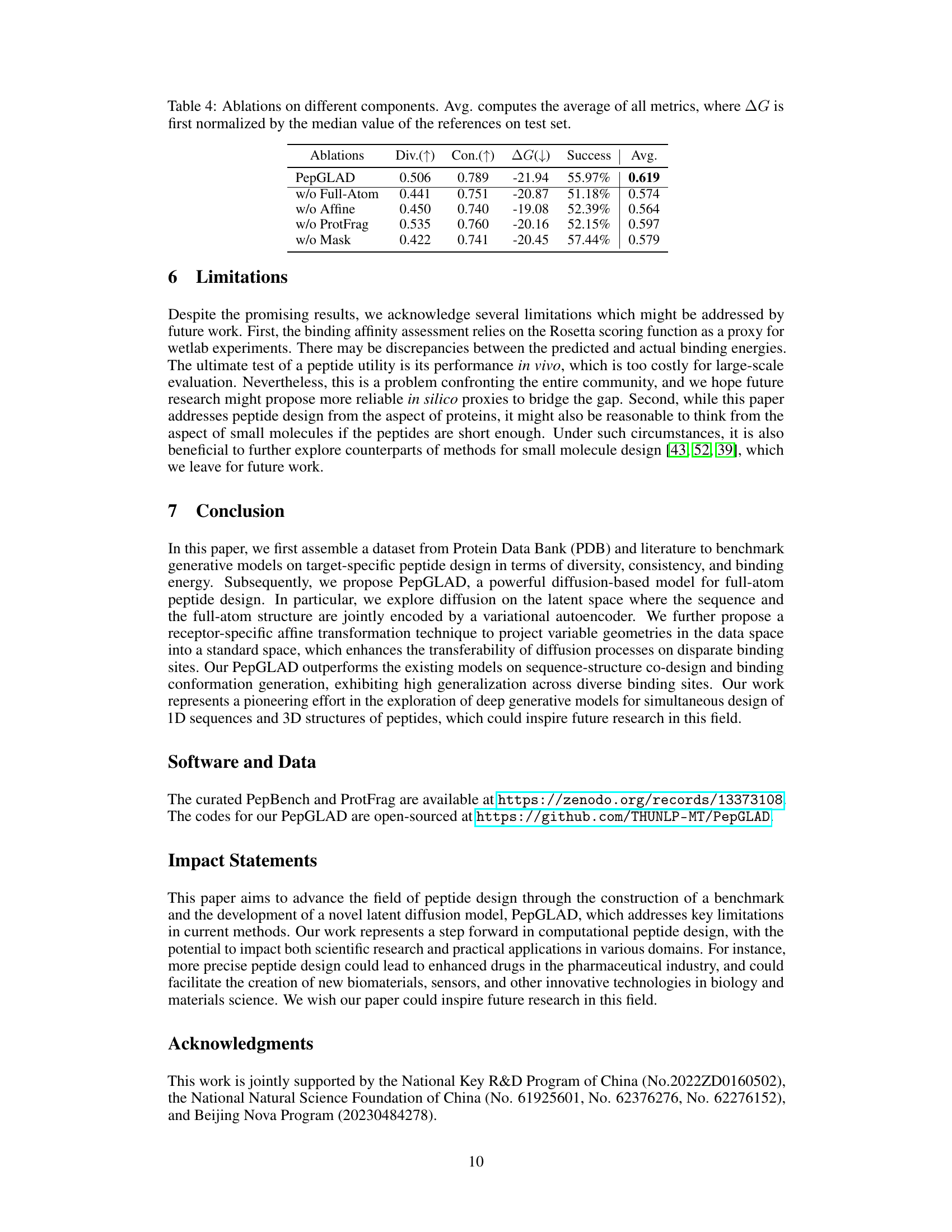

This figure visualizes the distribution of RMSDCα values obtained on the PepBench test set when comparing generated peptide conformations against reference structures. It also shows a specific example comparing a reference structure (PDB: 3vxw) with a peptide conformation generated by PepGLAD, highlighting the low RMSDCα, RMSDatom, and high DockQ score achieved. The box plot provides a visual representation of the distribution’s central tendency, spread, and outliers, offering a comparison of PepGLAD’s performance against other models.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the PepGLAD model, which comprises three modules: a variational autoencoder, an affine transformation, and a latent diffusion model. The autoencoder compresses the peptide sequence and structure into a fixed-dimensional latent space, handling the variable-size nature of amino acid residues. The affine transformation converts the 3D coordinates into a standardized space, improving generalization across different binding sites. Finally, the latent diffusion model generates the peptide sequence and structure in this standardized space, which is then converted back to the original space using the inverse transformation.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the PepGLAD model, which consists of three main modules: a variational autoencoder (VAE), an affine transformation, and a latent diffusion model. The VAE compresses the peptide’s sequence and structure into a fixed-dimensional latent space. The affine transformation converts the 3D coordinates of the peptide into a shared standard space to improve generalization across different binding sites. Finally, the latent diffusion model generates the peptide in this standard latent space. The figure shows the flow of information through the model, from the input peptide and binding site to the generated peptide.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the PepGLAD model, which consists of three main modules: a Variational Autoencoder (VAE), an affine transformation, and a latent diffusion model. The VAE encodes the peptide sequence and structure into a fixed-dimensional latent representation, which is then transformed into a standard space using a receptor-specific affine transformation. Finally, the latent diffusion model generates new peptides in this standard latent space, which are then decoded back into the original sequence and structure space by the decoder.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the PepGLAD model, which consists of three main modules: Variational Autoencoder, Affine Transformation, and Latent Diffusion. The Variational Autoencoder compresses the peptide’s sequence and 3D structure into a fixed-dimensional latent representation. The Affine Transformation converts the 3D coordinates to a shared standard space, improving generalization. Finally, the Latent Diffusion model generates new sequences and structures within this standardized latent space.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the PepGLAD model, which consists of three main modules: 1. Variational Autoencoder: Encodes the peptide’s sequence and structure into a fixed-dimensional latent representation. 2. Affine Transformation: Transforms the 3D coordinates of the peptide and binding site into a shared standard space, improving generalization. 3. Latent Diffusion Model: Generates the peptide’s sequence and structure in the standardized latent space using a diffusion process.

More on tables

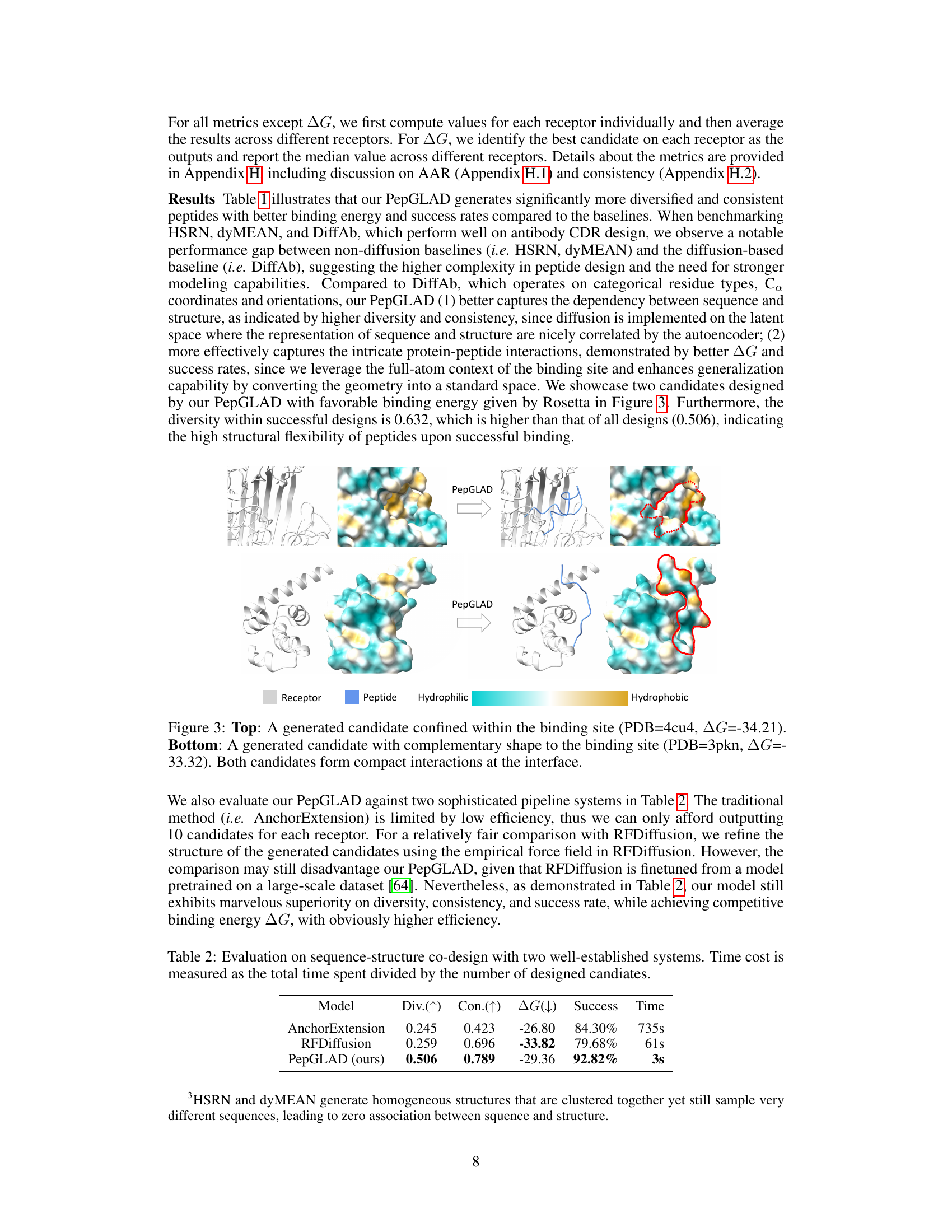

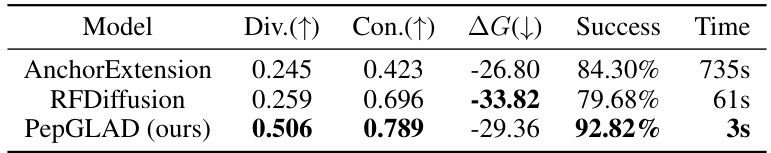

This table compares the performance of PepGLAD against two other well-established peptide design methods: AnchorExtension and RFDiffusion. The metrics used for comparison are diversity (Div.), consistency (Con.), binding energy (△G), success rate (Success), and time cost (Time). The results show that PepGLAD significantly outperforms the other methods in terms of diversity, consistency, and success rate, while achieving competitive binding affinity.

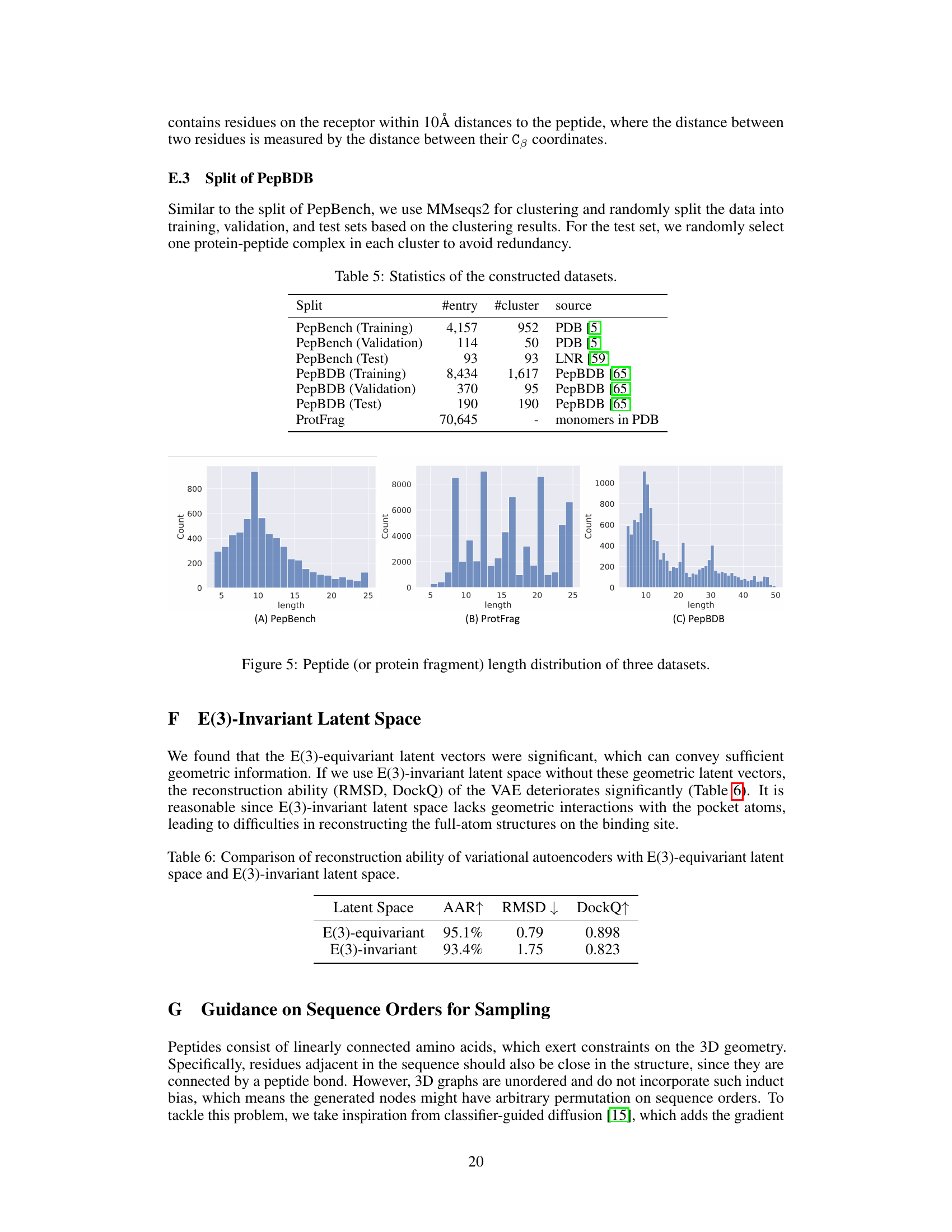

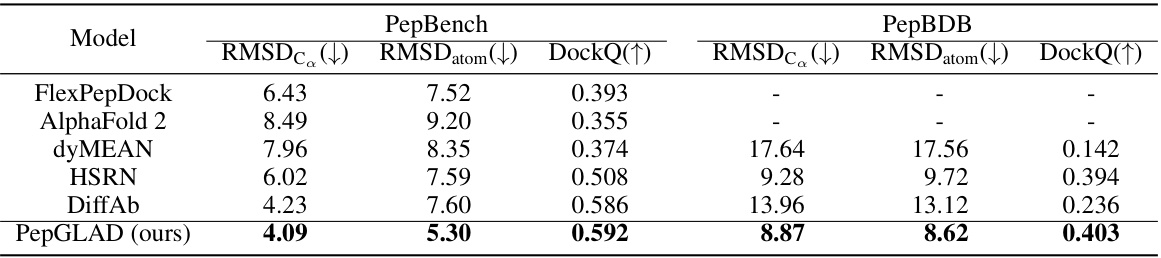

This table presents the results of the Binding Conformation Generation task. For each binding site, 10 peptide candidates were generated, and their similarity to the reference binding conformation was evaluated using three metrics: RMSDC (root mean square deviation of Cα atoms), RMSDatom (RMSD of all atoms), and DockQ (a comprehensive metric evaluating full-atom similarity on the binding interface). Lower values for RMSDC and RMSDatom, and a higher value for DockQ, indicate better performance. The table compares the performance of PepGLAD against several baseline methods on two different datasets, PepBench and PepBDB.

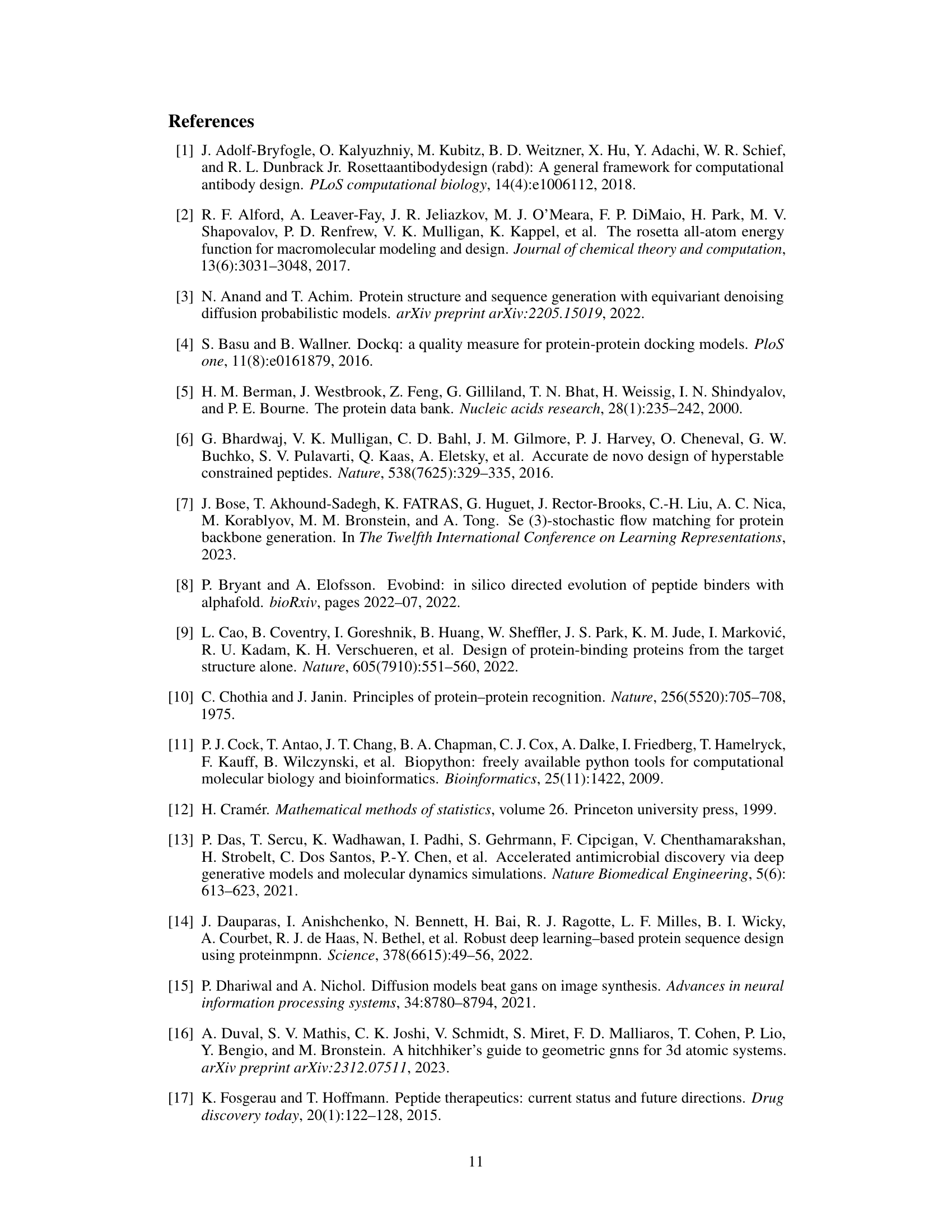

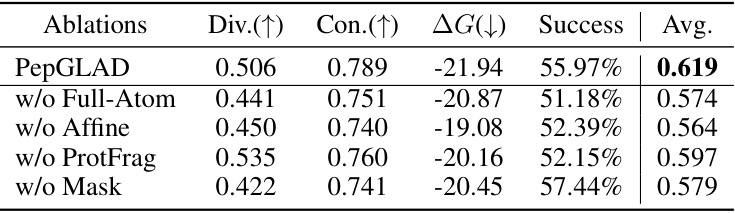

This table presents the ablation study results for the proposed PepGLAD model. It shows the impact of removing different components of the model on several metrics: Diversity (Div.), Consistency (Con.), Binding energy (ΔG), Success rate (Success), and the average of these four metrics (Avg.). The ablation studies include removing the full-atom geometry, the affine transformation, the unsupervised data from protein fragments, and the masking policy during training. The results demonstrate the importance of each component in achieving the overall performance of PepGLAD.

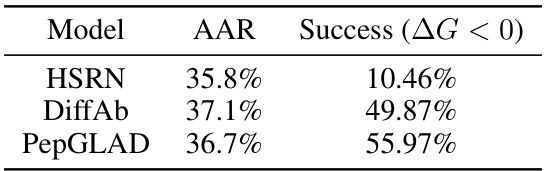

This table presents the results of the sequence-structure co-design task, comparing PepGLAD against several baselines. Metrics include diversity (Div.) of generated sequences and structures, consistency (Con.) between sequences and structures, binding energy (ΔG), and success rate (percentage of successful designs with ΔG<0). The results show PepGLAD’s superior performance in all aspects.

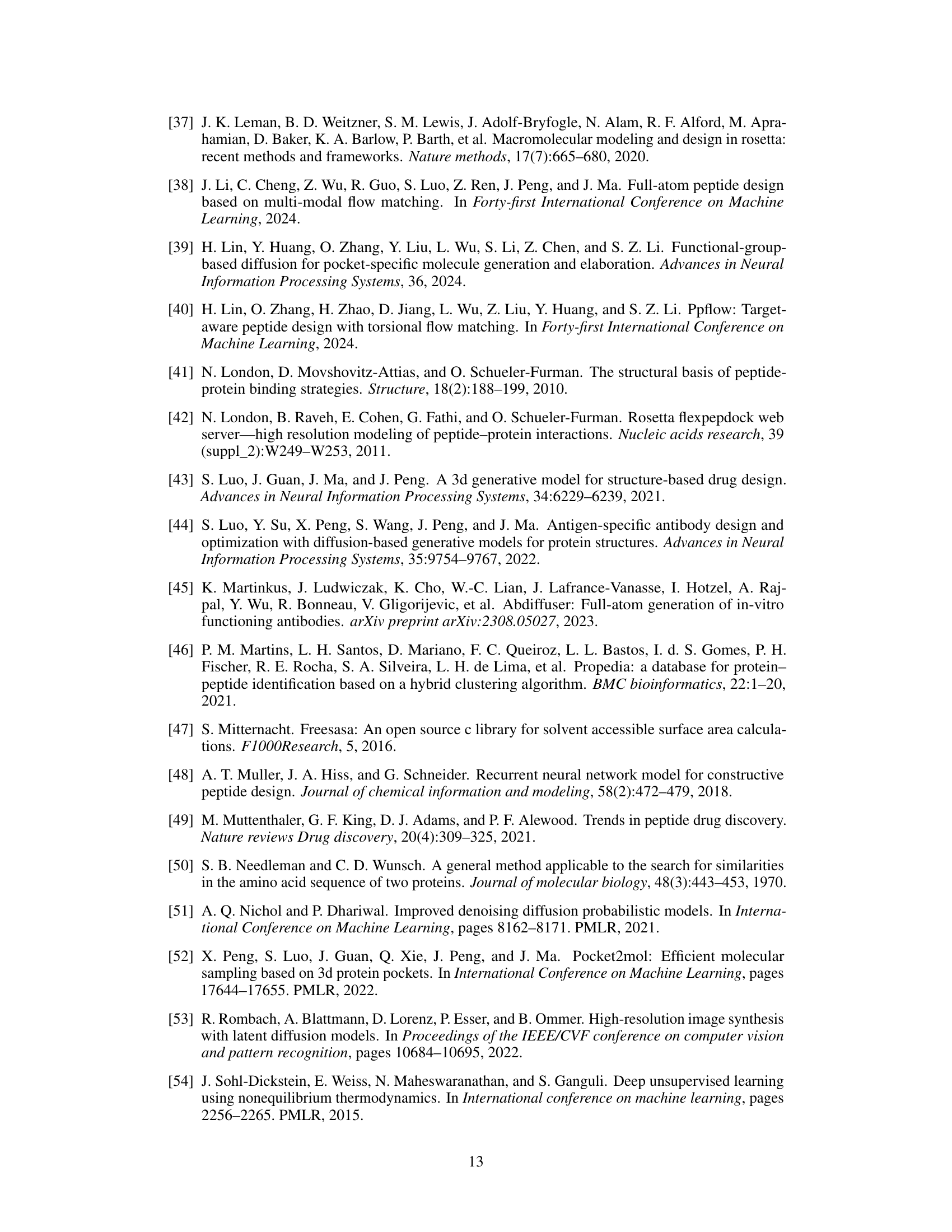

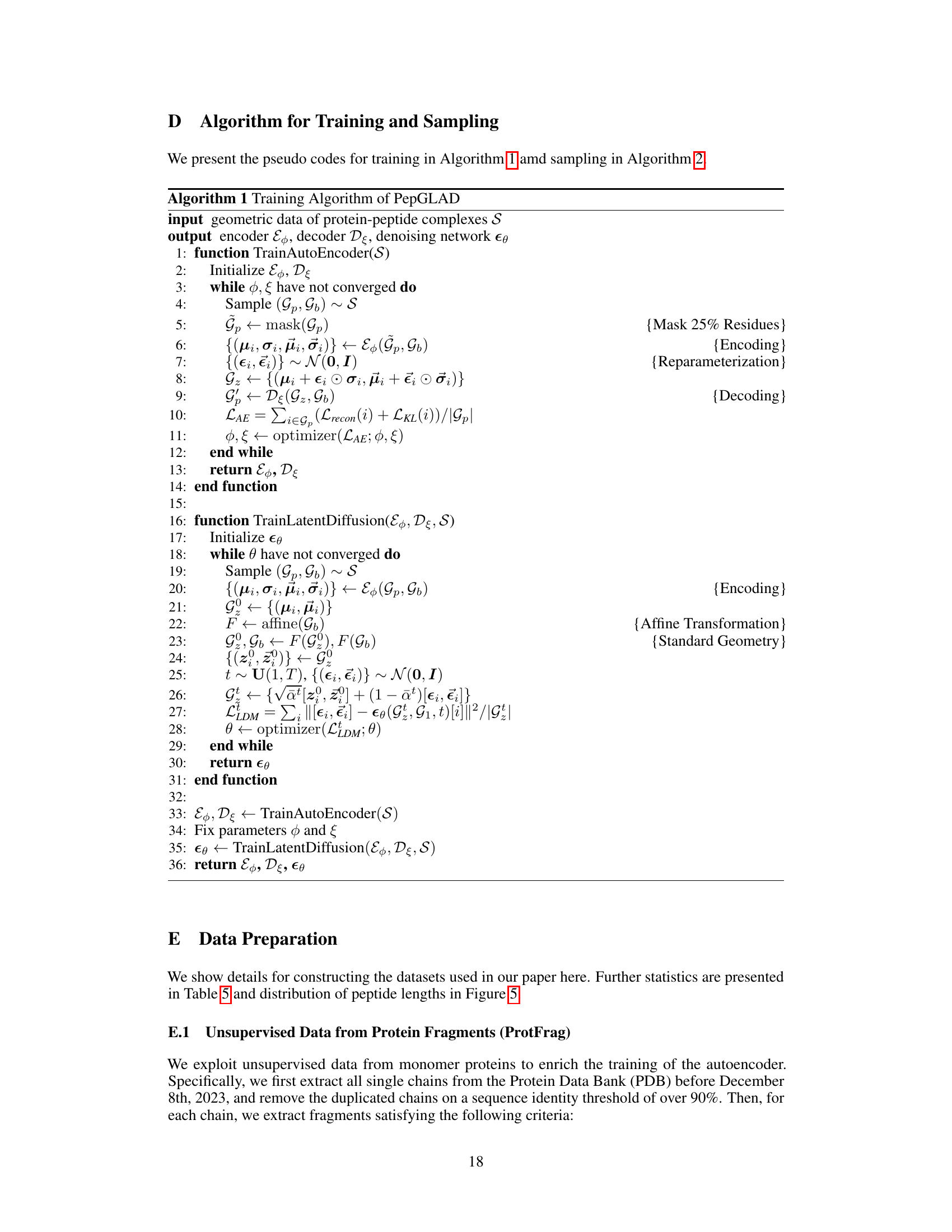

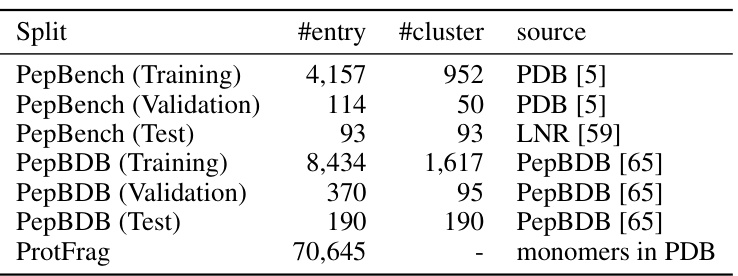

This table presents the statistics of the constructed datasets used in the paper. It breaks down the number of entries and clusters in the training, validation, and test sets for both PepBench and PepBDB datasets. It also includes the number of entries and source for the ProtFrag dataset which is used for unsupervised pretraining.

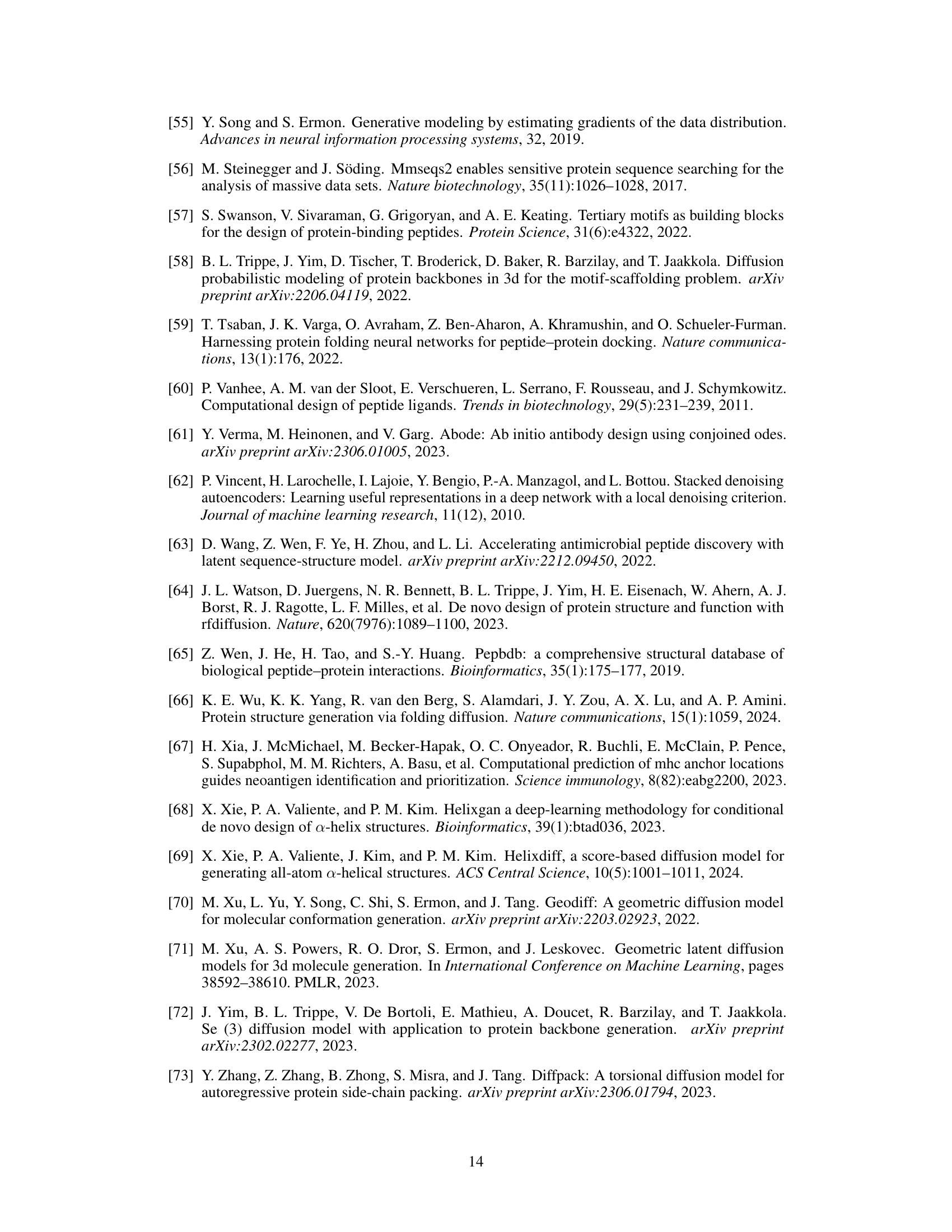

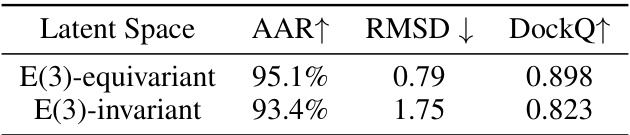

This table compares the performance of variational autoencoders using two different types of latent spaces: E(3)-equivariant and E(3)-invariant. The comparison focuses on three metrics to evaluate the reconstruction quality: Amino Acid Recovery (AAR), Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), and DockQ. Higher AAR and DockQ values, along with a lower RMSD value, indicate better reconstruction performance. The results demonstrate that the E(3)-equivariant latent space significantly outperforms the E(3)-invariant latent space in reconstructing the full-atom structures.

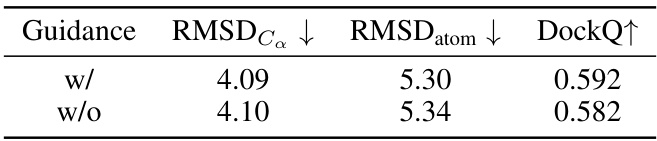

This table presents the results of the Binding Conformation Generation task. For each receptor (binding site), 10 peptide candidates were generated, and their similarity to the reference binding conformation was evaluated using three metrics: RMSDc (Root Mean Square Deviation of Cα atoms), RMSDatom (RMSD of all atoms), and DockQ (a comprehensive metric evaluating full-atom similarity at the binding interface). Lower values for RMSDc and RMSDatom indicate better agreement with the reference structure, while a higher DockQ value indicates greater similarity. The table compares the performance of PepGLAD against several baselines.

This table presents the quantitative results of the sequence-structure co-design task. Four metrics are used to evaluate the performance of different models, including diversity of sequences and structures, the consistency between them, the binding affinity (represented by the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔG), and the success rate. Higher diversity and consistency indicate better performance. Lower ΔG and higher success rates indicate stronger binding affinity and successful peptide design.

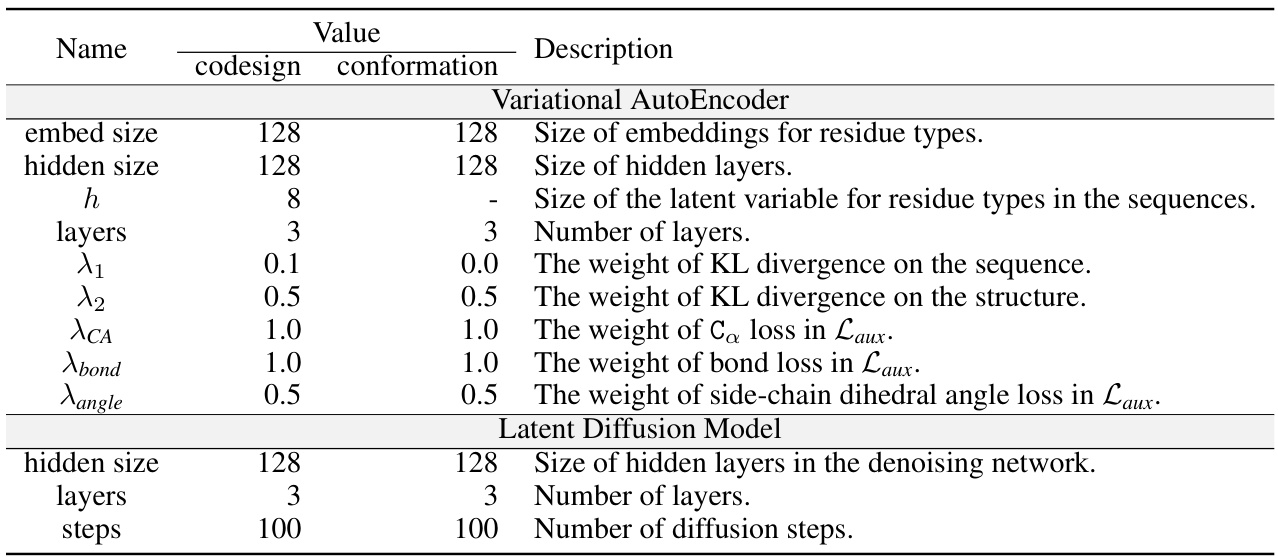

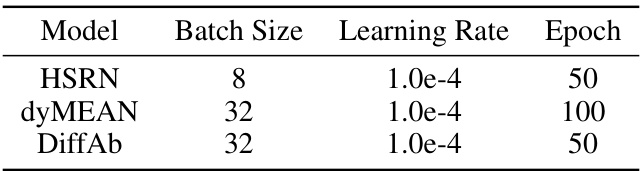

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the PepGLAD model. It shows values used for both the sequence-structure co-design and binding conformation generation tasks. The hyperparameters are categorized into those for the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) and the Latent Diffusion Model. Specific parameters include the sizes of embeddings and hidden layers, the number of layers, and the weights associated with different loss functions (KL divergence on sequences and structures, Ca loss, bond loss, and angle loss).

This table presents the results of sequence-structure co-design experiments on the PepBench and PepBDB datasets. It compares the performance of PepGLAD against several baseline models across four key metrics: diversity of sequences (Div.(↑)), diversity of structures (Div.(↑)), consistency between sequences and structures (Con.(↑)), average binding energy (△G(↓)), and the success rate of generating peptides with favorable binding energies (Success). Higher values for Div.(↑) and Con.(↑) and lower values for △G(↓) indicate better performance. The upward and downward arrows indicate the direction of improvement for each metric.

Full paper#