↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) heavily rely on effective prompt engineering. Automatic prompt optimization (APO) aims to automate this process, typically focusing on either instruction optimization (IO) or exemplar optimization (EO). However, current research disproportionately emphasizes IO. This paper systematically compares IO and EO across various tasks. The study addresses this research gap by comprehensively evaluating both approaches separately and in combination.

The findings reveal that EO, even with simple methods like random search, can significantly improve performance, surpassing SoTA IO methods that focus solely on instructions. Furthermore, the research discovered a synergy between EO and IO: intelligently combining both techniques consistently outperforms either approach in isolation, even with constrained computational budgets. The results suggest a critical need for more balanced research in APO, with greater focus given to EO and its combined application with IO to advance the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the current research bias towards instruction optimization in automatic prompt optimization (APO) and highlights the significant, often overlooked, role of exemplar optimization. It provides practical methods and valuable insights for researchers to improve LLM performance and opens new avenues for APO research. The findings are relevant across various LLM applications and could significantly impact future prompt engineering strategies.

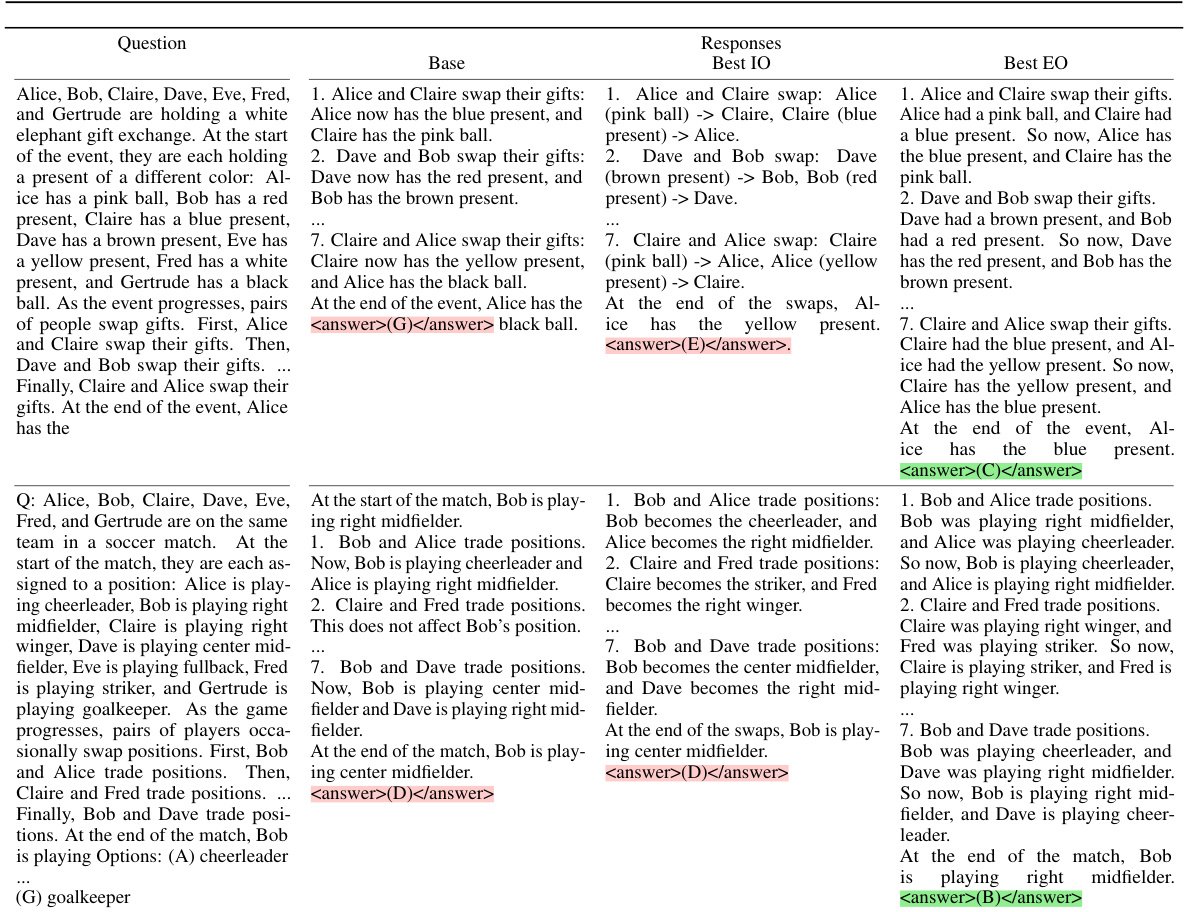

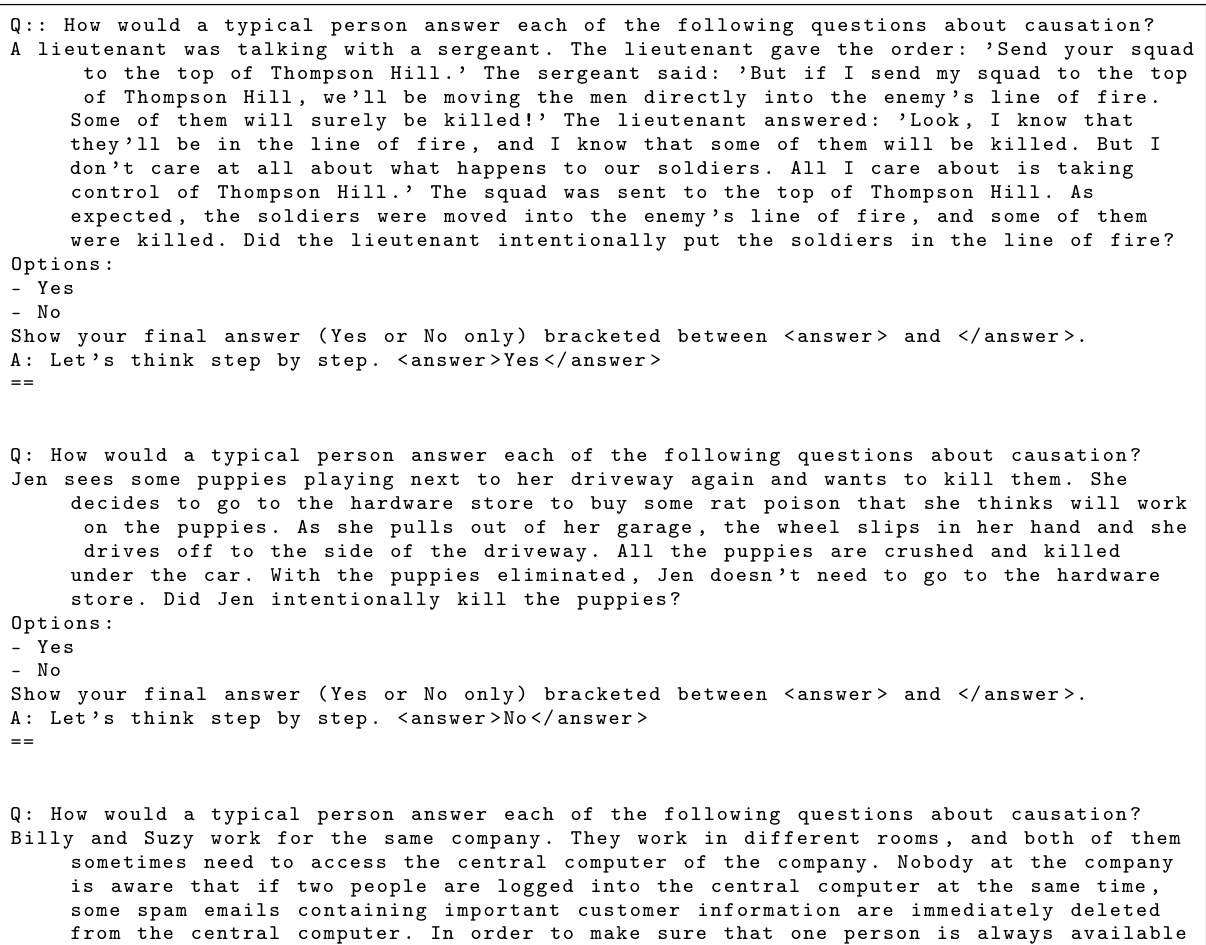

Visual Insights#

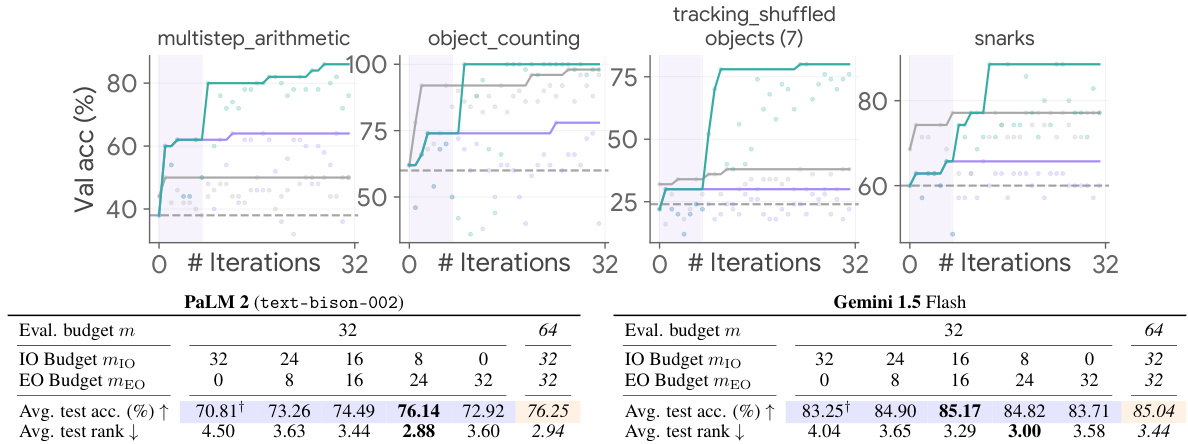

This figure shows the average performance across more than 20 tasks using the PaLM 2 Language Model. It compares different prompt optimization approaches. The blue bars represent instruction optimization (IO) methods. The orange bars show exemplar optimization (EO) methods. The purple bar shows IO combined with random exemplars, while the cyan bar shows IO combined with optimized exemplars. The key finding is that EO, even simple random search, can significantly improve the accuracy compared to complex IO methods. Combining IO and EO produces the best results.

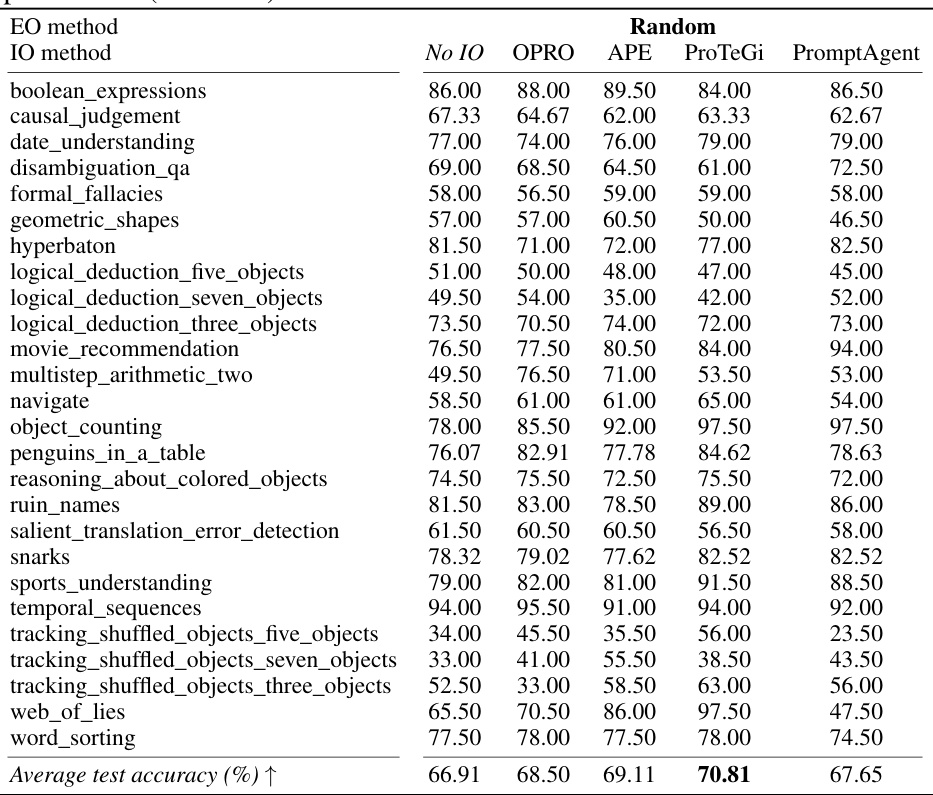

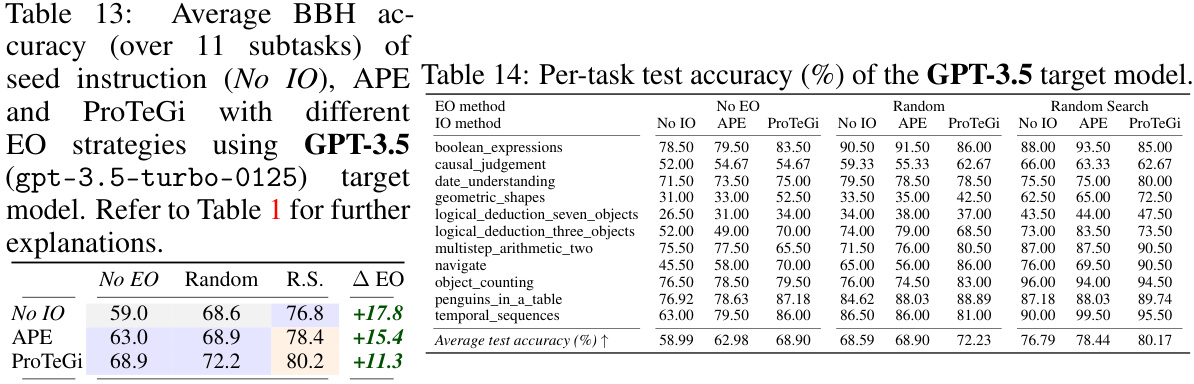

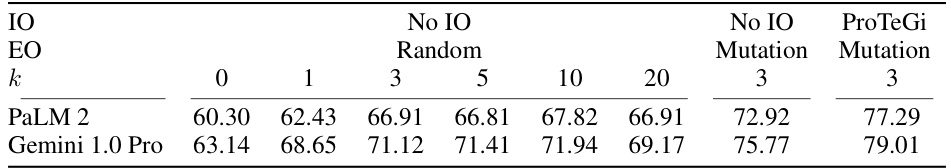

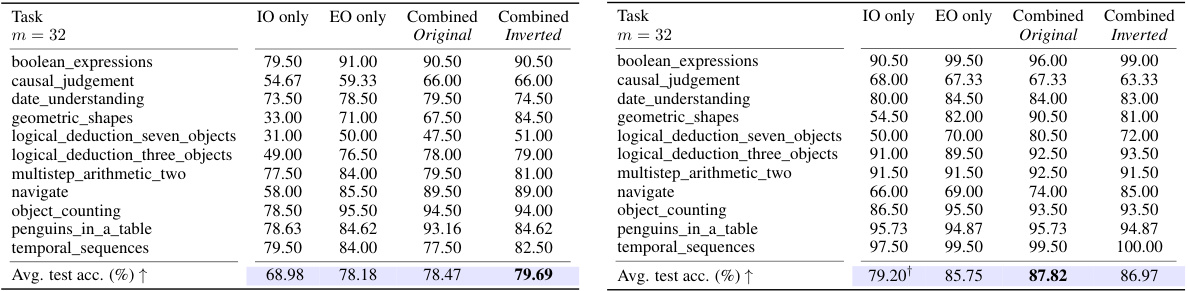

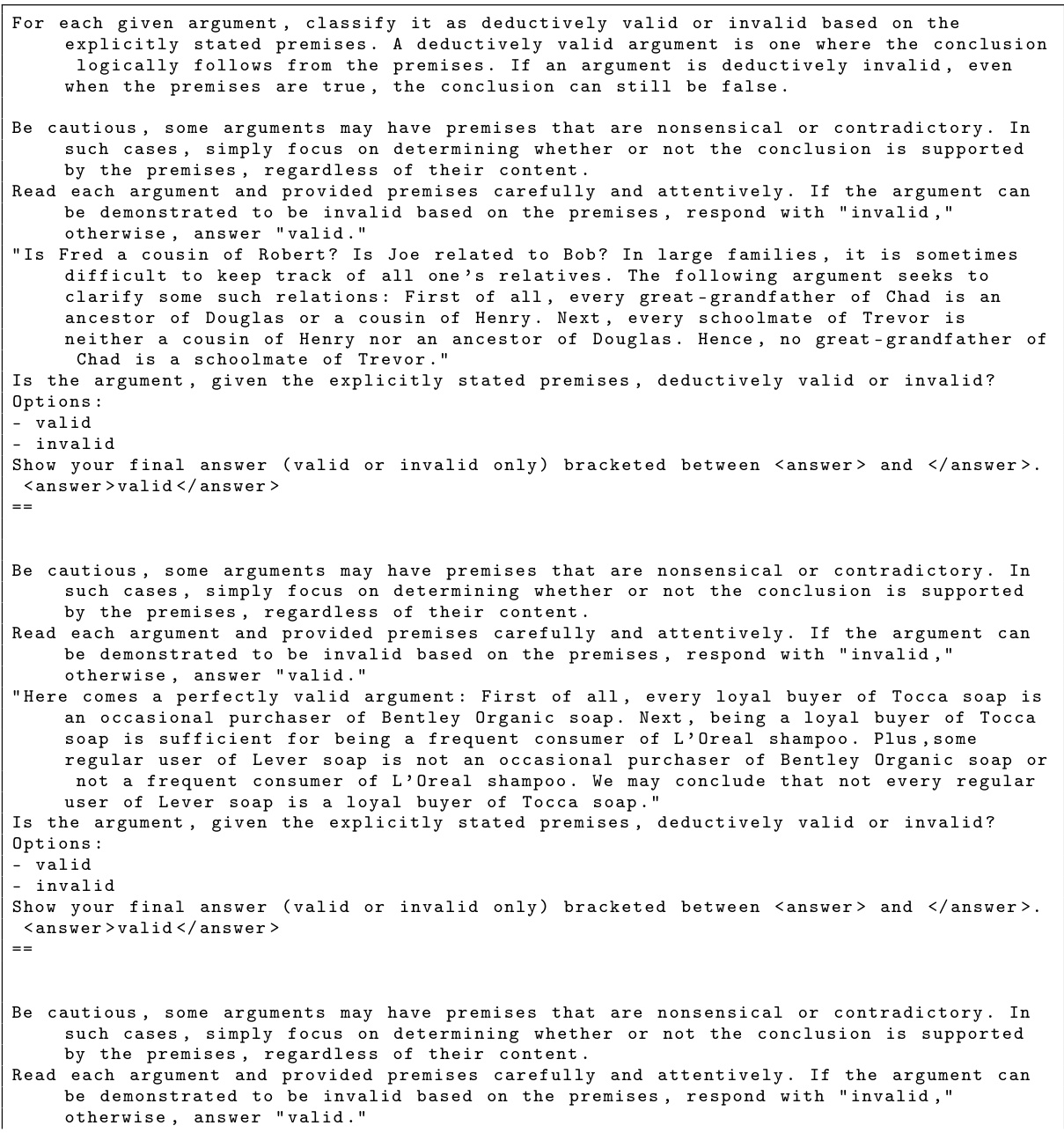

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy scores achieved by combining various instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. It shows the performance of using no IO/EO, various IO methods (APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO), and various EO methods (Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation). The table highlights the maximum improvement in accuracy obtained with each EO method compared to the baseline (No EO) and the maximum improvement when combining IO and EO, relative to the baseline (No IO/EO). The color-coding indicates the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations on the validation set) for each experiment.

In-depth insights#

Prompt Engineering#

Prompt engineering is a crucial technique for effectively utilizing large language models (LLMs). It involves carefully crafting input prompts to guide the model towards desired outputs, optimizing both instructions and exemplars to maximize performance. While instruction optimization focuses on refining the textual instructions, exemplar optimization centers on selecting relevant examples. The interplay between these two approaches is significant, with intelligent combination often surpassing the performance of either method alone. Effective prompt engineering is vital, even with highly capable instruction-following models, as the right exemplars can significantly influence LLM behavior. Therefore, a balanced approach considering both instructions and exemplars remains crucial for unlocking the full potential of LLMs and minimizing the need for manual intervention.

Exemplar Optimization#

Exemplar optimization (EO) in automatic prompt optimization (APO) focuses on selecting the most effective examples to guide a large language model’s (LLM) behavior. Unlike instruction optimization (IO), which refines the instructions themselves, EO leverages the existing input-output pairs from a validation set, treating them as exemplars. The paper highlights the often-overlooked significance of EO, demonstrating that intelligent reuse of model-generated exemplars can substantially improve LLM performance, even surpassing state-of-the-art IO methods in certain scenarios. Simple EO strategies, such as random search, can surprisingly outperform sophisticated IO methods, revealing that choosing the right exemplars is paramount. The research emphasizes a synergistic relationship between EO and IO, advocating for their combined use to achieve optimal results. This highlights a critical need for a more balanced approach to APO, giving EO the attention it deserves. Future research should explore the combined use of EO and IO, as well as more advanced optimization techniques for selecting and utilizing exemplars, especially in resource-constrained settings.

Synergy of IO & EO#

The research explores the interplay between Instruction Optimization (IO) and Exemplar Optimization (EO) in enhancing Large Language Model (LLM) performance. A key finding is the synergistic relationship between IO and EO, where intelligently combining both methods consistently surpasses the performance achieved by either method alone. This suggests that optimizing instructions and exemplars jointly unlocks a level of performance not attainable through independent optimization. The study demonstrates that even simple EO strategies can significantly improve performance, sometimes even exceeding state-of-the-art IO methods. This highlights the often-underestimated importance of EO, suggesting that it deserves more attention in future research. Furthermore, the investigation suggests that SoTA IO methods might implicitly utilize model-generated exemplars, indicating an inherent link between the two optimization strategies. The findings advocate for a more holistic approach to automatic prompt optimization, emphasizing the complementary nature of IO and EO and advocating for joint optimization techniques.

APO Generalization#

Analyzing the generalization capabilities of Automatic Prompt Optimization (APO) methods is crucial for their real-world applicability. Effective APO should not only optimize prompt performance on a validation set but also generalize well to unseen data. A model that performs exceptionally well on the validation set but poorly on unseen data suffers from overfitting, rendering it unreliable. The paper investigates this by comparing validation and test accuracies, revealing the extent of generalization achieved by different APO techniques. Exemplar Optimization (EO) methods demonstrate superior generalization compared to Instruction Optimization (IO) methods, suggesting that carefully selected exemplars are more transferable across different tasks than finely tuned instructions. This highlights the importance of a balanced approach, potentially combining IO and EO for optimal performance, while maintaining good generalization. Further research should focus on understanding why EO generalizes better and how to design robust APO strategies that avoid overfitting and enhance transferability.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize a more unified approach to automatic prompt optimization (APO), focusing on the synergistic interplay between instruction and exemplar optimization. Further investigation into the implicit generation of exemplars by instruction optimization methods is crucial, to understand their contribution to overall performance. This requires deeper analysis of the generated prompts to identify and quantify the impact of unintentional exemplar creation. Developing advanced methods for exemplar selection is vital, moving beyond simple heuristics towards optimization-based techniques that can effectively handle high-dimensional search spaces in many-shot scenarios. This would require exploring novel search strategies and incorporating effective methods for promoting exemplar diversity. Investigating the impact of context length limitations on the effectiveness of different APO methods is needed, especially given the emergence of LLMs with expanded context windows. Finally, a thorough analysis of the generalization capabilities of various APO methods will clarify their practical applicability across diverse tasks and model types.

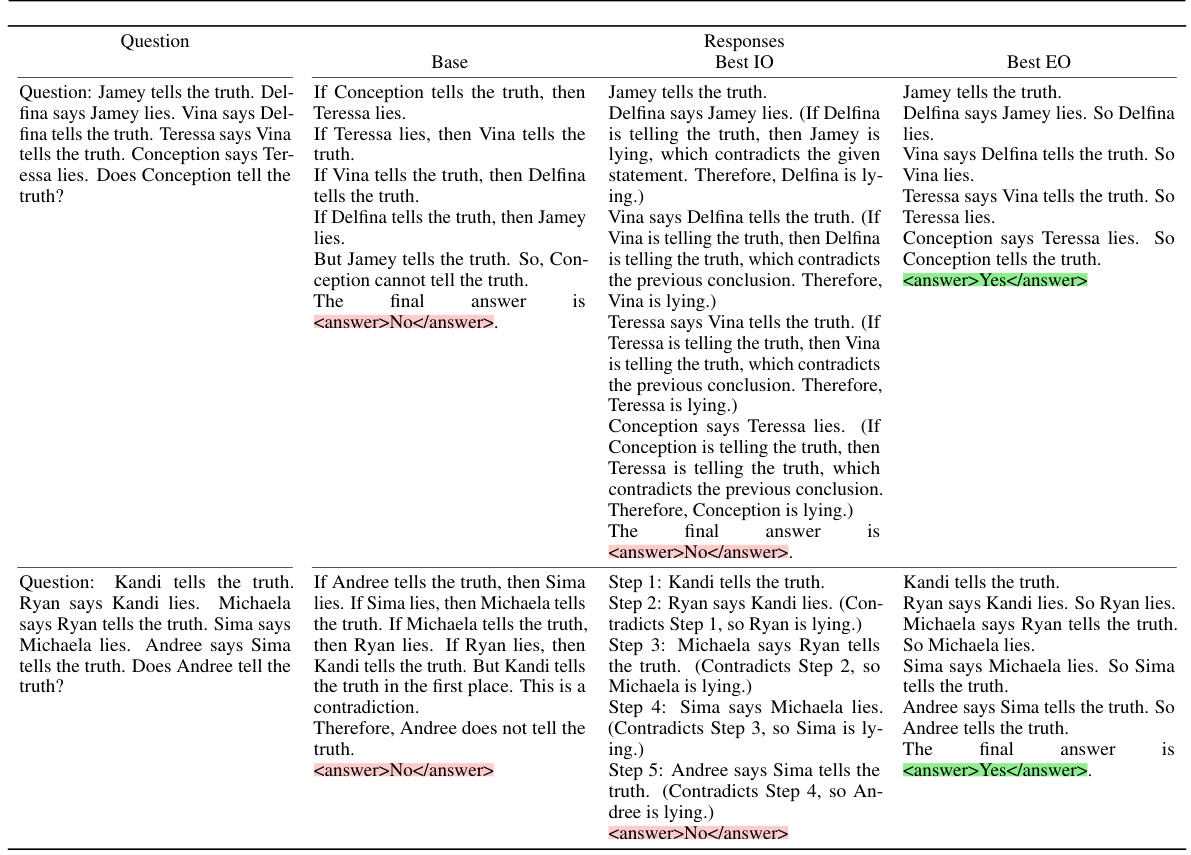

More visual insights#

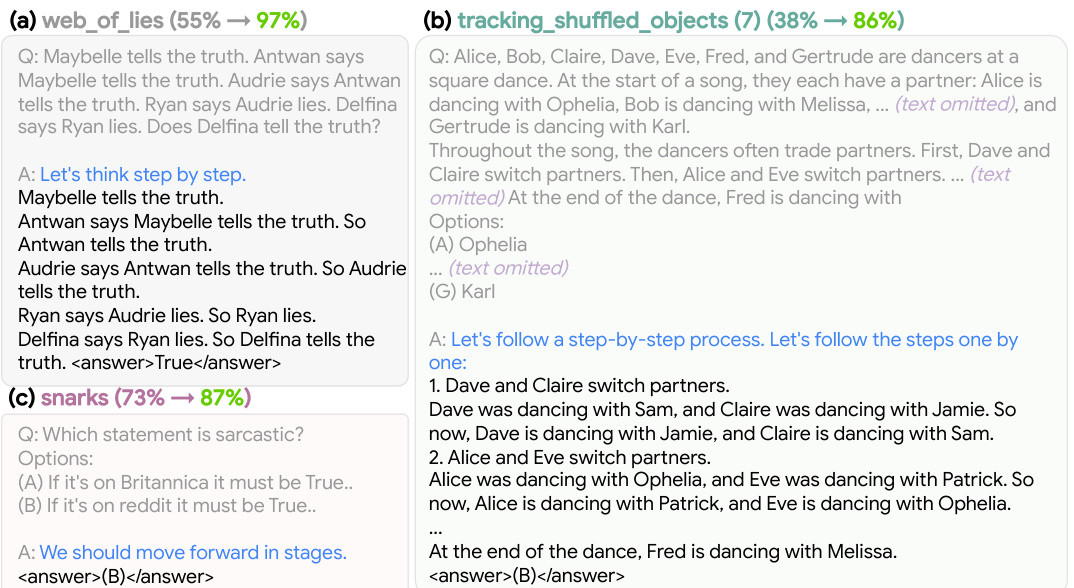

More on figures

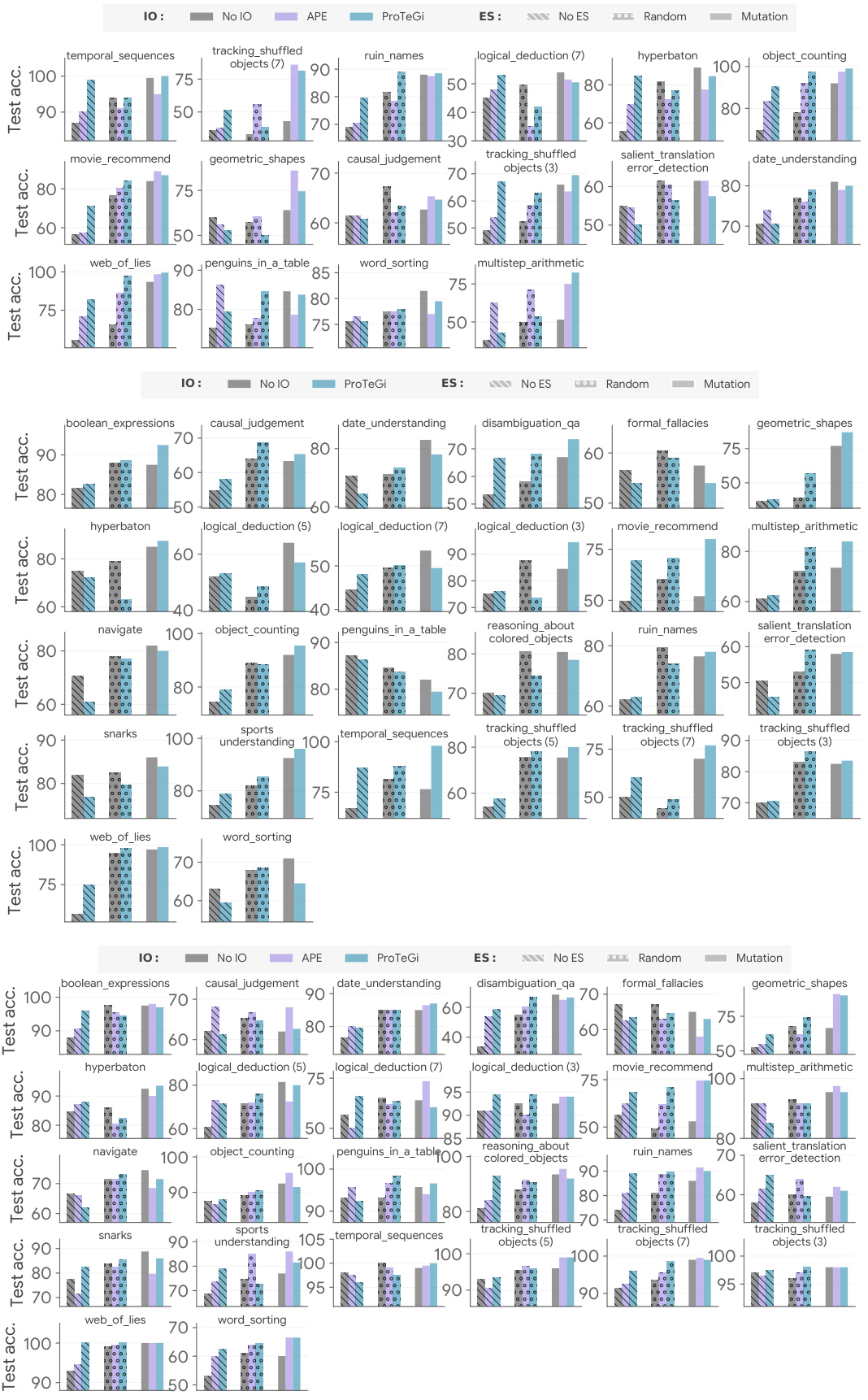

This figure shows the average performance across more than 20 tasks using PaLM 2 Language Model. It compares three automatic prompt optimization (APO) approaches: instruction optimization (IO) alone, exemplar optimization (EO) alone, and a combination of both (IO+EO). The results demonstrate that EO can significantly improve performance, sometimes surpassing even state-of-the-art IO methods. Combining IO and EO yields the best overall results. The color-coding helps visualize the performance of each approach.

This figure shows the average performance across more than 20 tasks using different automatic prompt optimization (APO) methods. It compares instruction optimization (IO), exemplar optimization (EO), and combinations of both. The key finding is that effectively optimizing exemplars can lead to better results than optimizing instructions alone, even surpassing state-of-the-art IO methods. Combining both IO and EO yields the best performance.

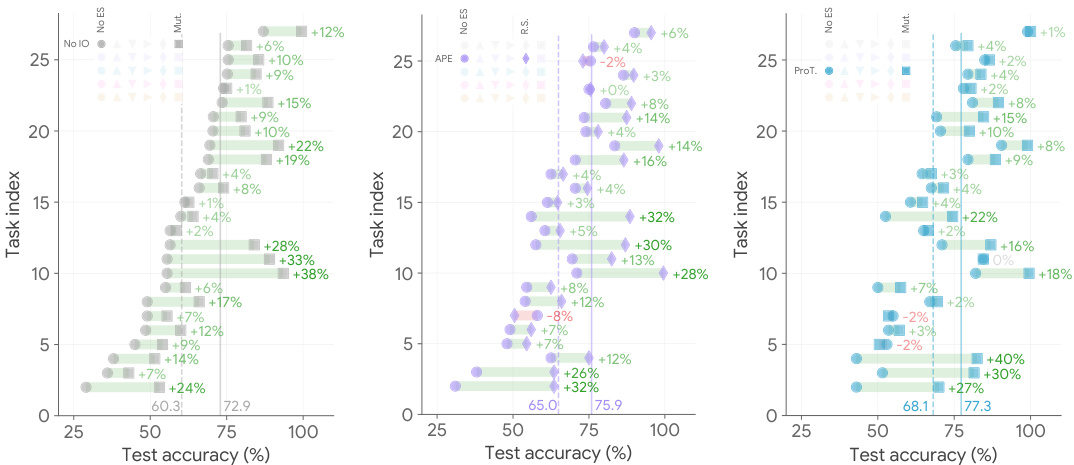

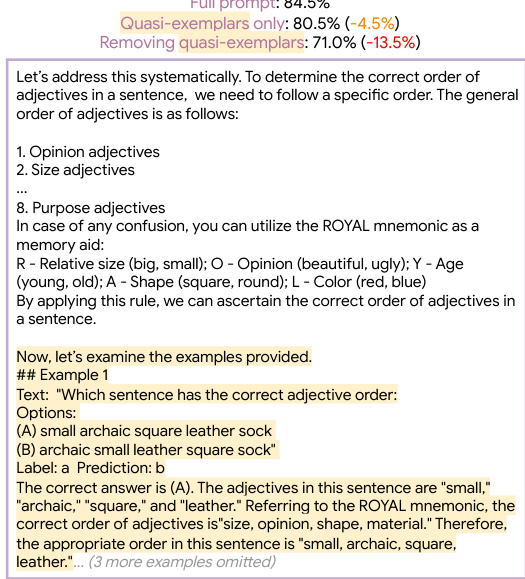

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization methods on a subset of BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks. It demonstrates that using exemplars, even with simple optimization strategies, outperforms state-of-the-art instruction optimization methods. The figure shows three scenarios: no instruction optimization, advanced instruction optimization, and the combination of both with the addition of exemplars. In all three scenarios, including exemplars through mutation significantly boosts the model’s performance, consistently improving average test accuracy. The task index is determined by performance with seed instructions only.

This figure shows the average performance of different automatic prompt optimization (APO) methods across more than 20 tasks using PaLM 2. It compares the performance of instruction optimization (IO) alone, exemplar optimization (EO) alone, and combinations of IO and EO. The key finding is that EO can significantly improve performance, even outperforming state-of-the-art IO methods, and that combining IO and EO yields the best results.

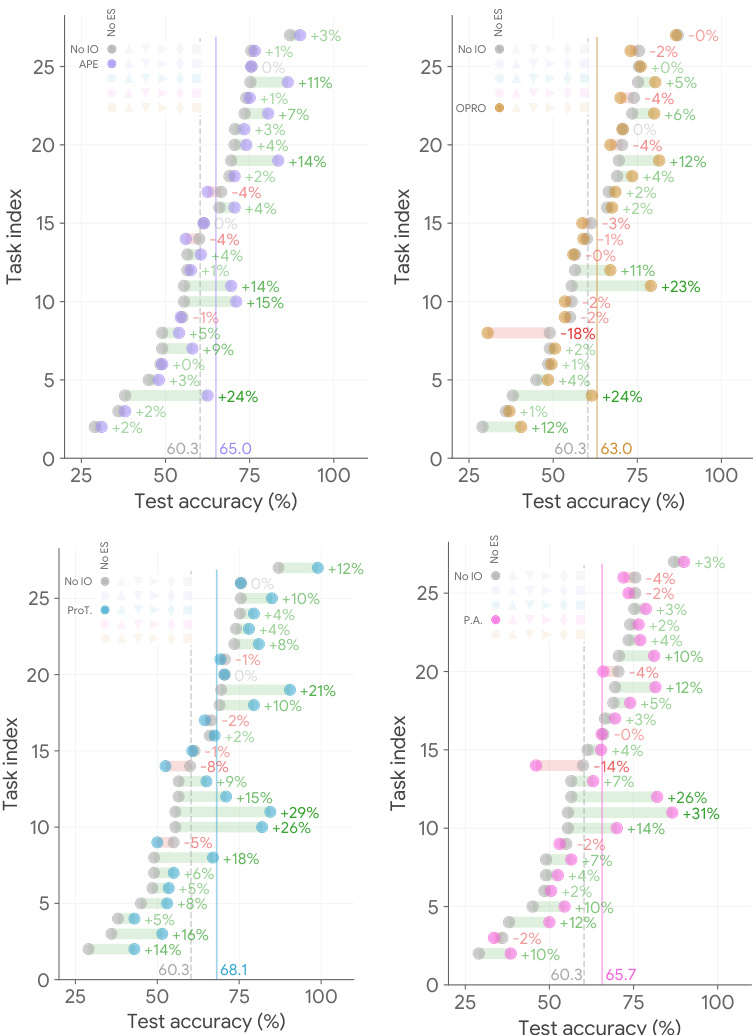

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization methods on a set of BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks. It shows that intelligently using model-generated exemplars significantly improves performance, even when compared to state-of-the-art instruction optimization methods. The figure highlights the impact of exemplar optimization (EO) alone and in combination with instruction optimization (IO), demonstrating EO’s importance and synergy with IO.

This figure compares different automatic prompt optimization (APO) methods on the performance of PaLM 2 across over 20 tasks. It shows that optimizing exemplars can yield better results than optimizing instructions alone, a finding that contrasts with current research trends. The best performance is achieved by combining both exemplar and instruction optimization.

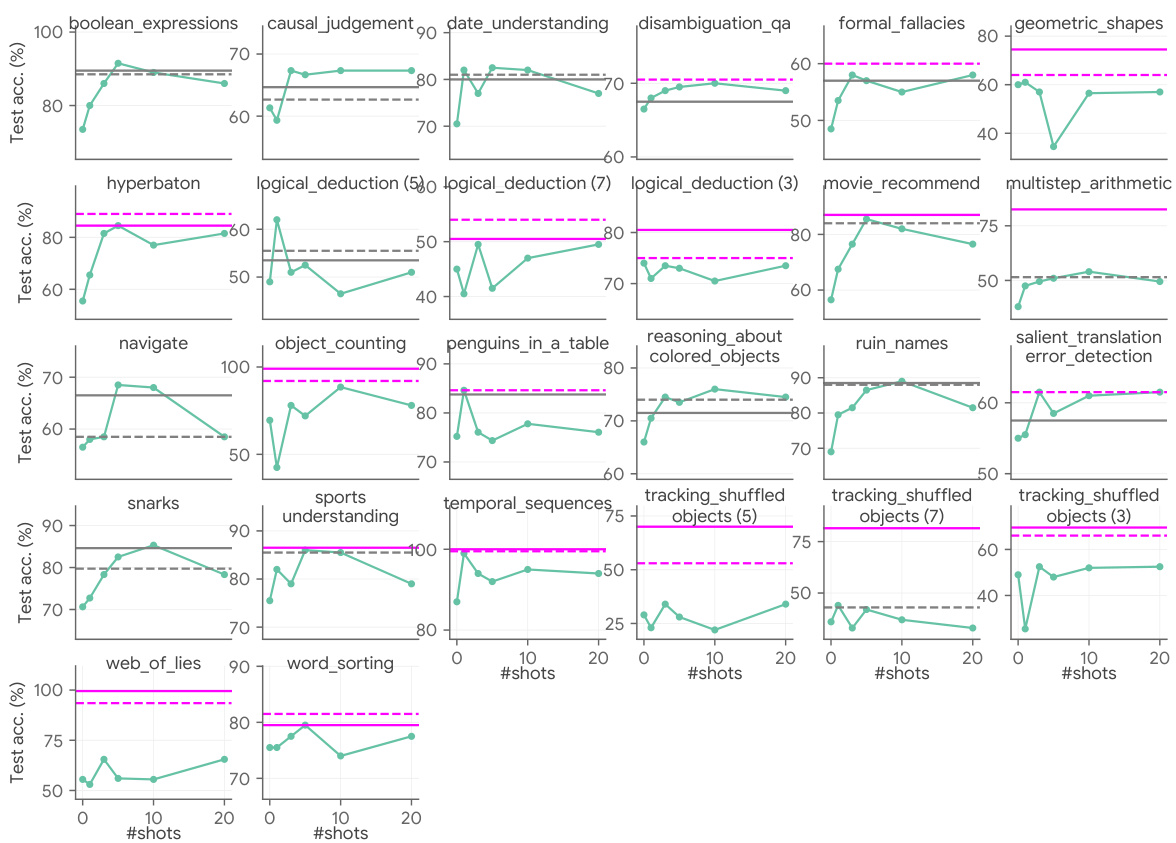

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) benchmark using PaLM 2. It demonstrates the impact of exemplar optimization (EO) alone and in combination with state-of-the-art instruction optimization (IO) methods (APE and ProTeGi). The left panel shows the improvement gained by EO when no IO is used, the middle panel shows the improvement when EO is combined with APE, and the right panel shows the improvement when EO is combined with ProTeGi. Dashed lines indicate performance before EO is applied and solid lines show performance after. The figure highlights that even a simple EO strategy (Mutation) significantly improves performance, often outperforming complex IO methods.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) dataset using PaLM 2. It shows that intelligently adding exemplars generated by the model itself consistently improves performance, even when compared to state-of-the-art instruction optimization techniques. The left panel shows performance without any instruction optimization, while the middle and right panels show results with two different SoTA instruction optimization methods (APE and ProTegi). Dashed lines represent performance before adding exemplars, while solid lines show performance after adding exemplars generated via a mutation process. The x-axis represents test accuracy, and the y-axis represents the task index (ordered by ascending accuracy with the seed instruction).

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization techniques on various tasks from the BIG-Bench Hard benchmark using PaLM 2. It shows that intelligently using model-generated exemplars significantly improves performance, often surpassing state-of-the-art instruction optimization methods, even with simple exemplar selection strategies. The results highlight the synergy between exemplar and instruction optimization, demonstrating that combining both techniques consistently yields the best performance.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) dataset using PaLM 2. It shows that adding exemplars consistently improves performance, even surpassing state-of-the-art instruction optimization methods. The left panel shows the results without instruction optimization, while the middle and right panels show the results with two different state-of-the-art instruction optimization methods (APE and ProTeGi). The dashed lines represent the performance before adding exemplars, and the solid lines show the improvement after adding exemplars generated using a mutation-based method.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization methods on a set of challenging tasks. It demonstrates that intelligently reusing model-generated input-output pairs as exemplars consistently improves performance, surpassing state-of-the-art instruction optimization methods in many cases. Even simple exemplar optimization techniques, such as random search, outperform complex instruction optimization when seed instructions are used without any optimization. The optimal combination of instruction and exemplar optimization surpasses the performance of either method alone.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization techniques on various tasks from the BIG-Bench Hard benchmark. The left panel shows results when no instruction optimization is used; the middle and right panels show results when advanced instruction optimization methods (APE and ProTeGi) are applied. In all panels, the effect of adding exemplars generated via a mutation method is assessed. The results indicate that intelligent use of exemplars (EO) consistently improves performance, surpassing state-of-the-art instruction optimization (IO) methods in many cases, even when using simple exemplar selection strategies.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization (APO) methods on a set of BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks. It shows that intelligently incorporating exemplars (EO), even with simple methods, consistently improves the performance over instruction optimization (IO) alone. The figure highlights the synergy between IO and EO, with optimal combinations surpassing individual methods and even outperforming state-of-the-art IO methods with simple EO strategies.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization techniques on a subset of BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks. It shows that intelligently adding model-generated exemplars (EO) consistently improves performance, even surpassing state-of-the-art instruction optimization (IO) methods in some cases. The left panel shows results without any IO, the middle panel shows results with APE IO, and the right panel shows results with ProTeGi IO. For each, the performance is compared with and without the addition of exemplars. The data clearly shows EO strategies consistently improve the baseline, and simple EO methods can even outperform complex IO methods.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization techniques on the BIG-Bench Hard benchmark using PaLM 2. It shows that intelligently incorporating exemplars consistently improves performance, even surpassing state-of-the-art instruction optimization methods in some cases. The results highlight the synergy between instruction optimization and exemplar optimization, indicating that combining both approaches yields superior results.

This figure displays a comparison of the performance of exemplar optimization (EO) methods against instruction optimization (IO) methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) benchmark using PaLM 2. The left panel shows the baseline performance using only seed instructions. The middle and right panels show results after applying state-of-the-art IO methods (APE and ProTeGi). Within each panel, performance is shown before and after adding exemplars optimized via mutation. The results clearly demonstrate that incorporating model-generated exemplars significantly boosts performance and that simple EO methods can outperform SoTA IO methods.

This figure shows the average performance across more than 20 tasks using PaLM 2. It compares different automatic prompt optimization (APO) methods: instruction optimization (IO), exemplar optimization (EO), and a combination of both. The key finding is that effectively optimizing exemplars can lead to better results than optimizing instructions alone, even surpassing state-of-the-art IO methods. Combining both IO and EO yields the best performance.

This figure compares the performance of different prompt optimization strategies on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) benchmark using PaLM 2. It shows that using exemplars (EO), even with simple optimization methods like random search, can significantly improve performance, outperforming state-of-the-art instruction optimization (IO) methods. The figure also highlights the synergistic effect of combining both EO and IO, showing that the best results are obtained when both instructions and exemplars are optimized.

This figure displays the average performance across more than 20 tasks using PaLM 2. It compares different automatic prompt optimization (APO) methods: instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO). It shows that EO can outperform state-of-the-art IO methods, even with simple strategies. Additionally, combining IO and EO leads to the best performance, exceeding the performance of each method alone.

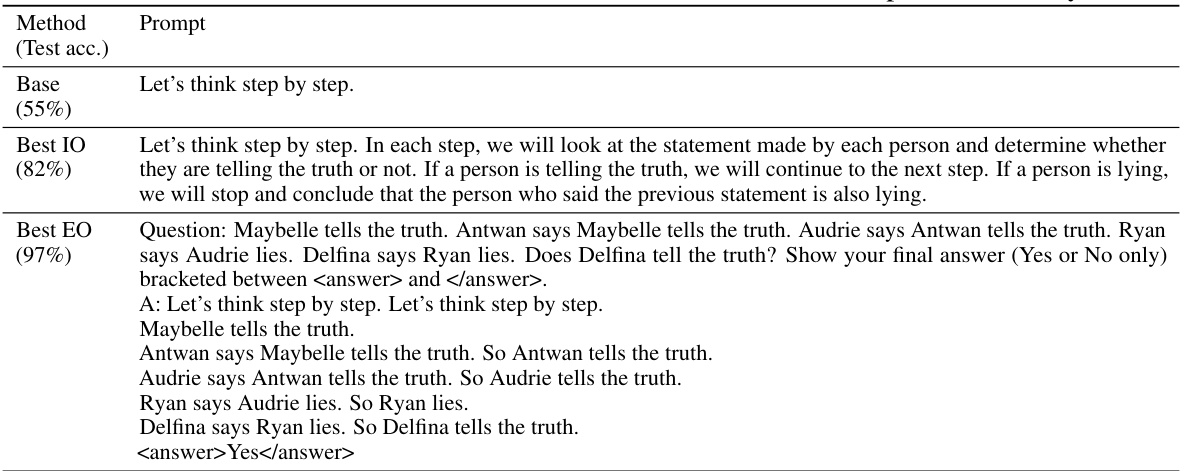

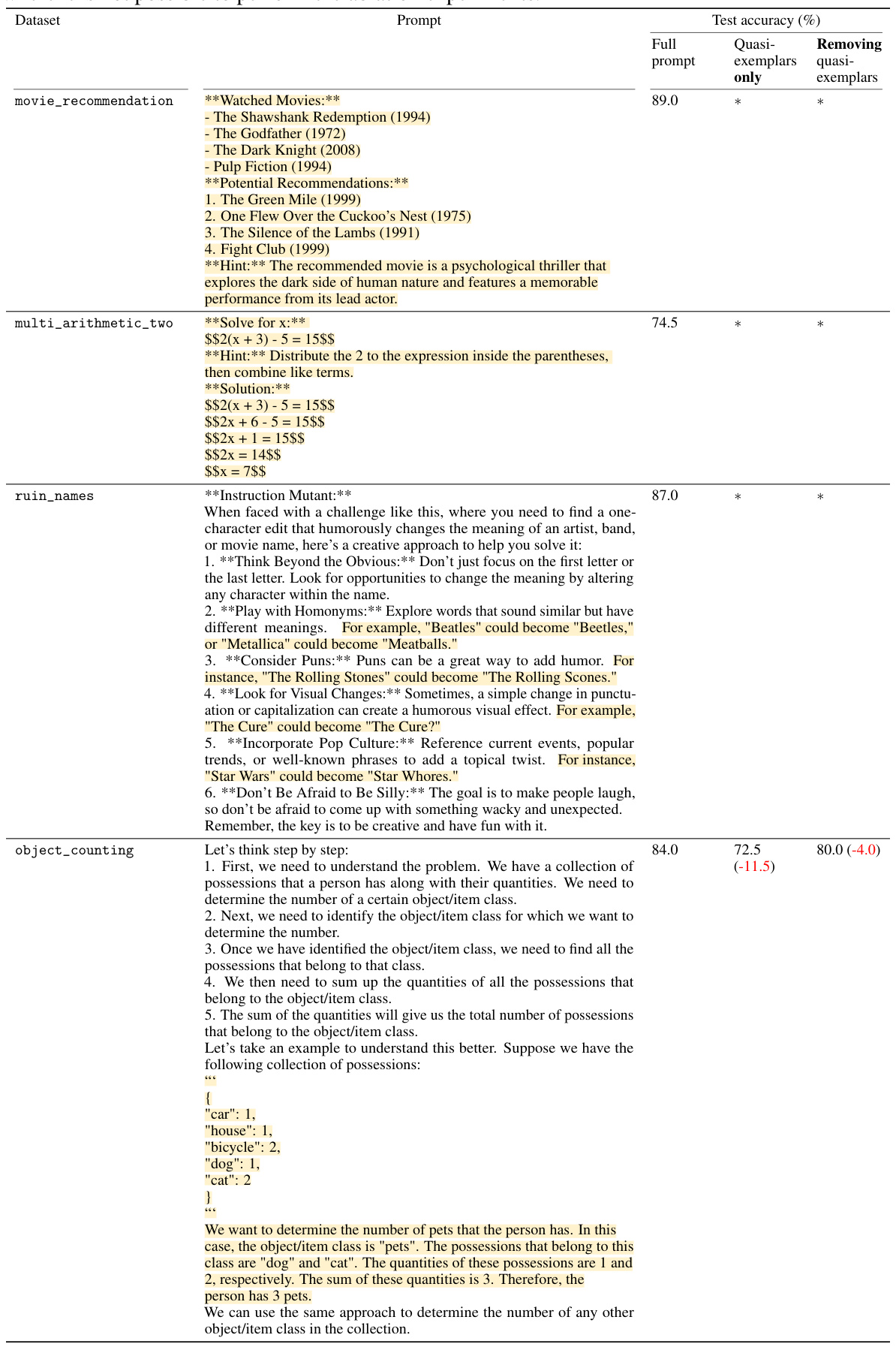

More on tables

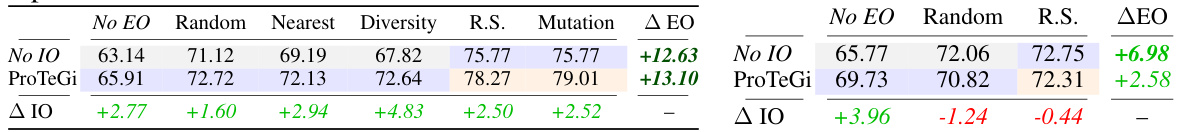

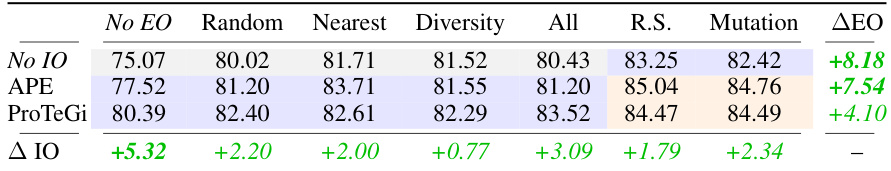

This table presents the average performance of different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) benchmark using PaLM 2. It shows the impact of various IO and EO strategies, both individually and in combination, on the model’s accuracy. The table highlights the computational cost associated with each method by color-coding the cells, indicating the number of prompt evaluations on the validation set. The last row and column show the maximum accuracy improvement achieved by EO and IO respectively.

This table presents the average performance across BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks for various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. The rows represent different IO methods (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO), while the columns show different EO methods (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation). The numbers in the cells show the average BBH accuracy for each IO-EO combination. The last row and column highlight the maximum improvement achieved over baselines (No IO and No EO). Color-coding indicates the computational cost: gray is zero cost, blue is a cost of 32 prompt evaluations, and orange is a cost of more than 32 prompt evaluations due to iterative optimization.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy results for various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using PaLM 2. It shows the impact of using different EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, and Mutation) in conjunction with different IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, and OPRO). The table highlights the maximum accuracy improvement achieved by using EO and/or IO compared to the baseline (No EO and No IO). The color-coding helps visualize the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) for each combination.

This table presents the average performance across various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) methods and exemplar optimization (EO) methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) benchmark using PaLM 2. The table shows the average BBH accuracy for each combination of IO and EO techniques. The last row and column highlight the maximum accuracy improvement achieved by using either EO or IO compared to the baseline (no IO or EO). The color-coding of the cells represents the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) involved in each optimization strategy.

This table presents the average performance across 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) methods and exemplar optimization (EO) methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) dataset using PaLM 2. The table shows the impact of using different IO and EO strategies, both individually and in combination. The color-coding indicates the computational cost of each method, with gray representing no additional cost, blue representing a cost of 32 prompt evaluations, and orange representing a cost of 32 prompt evaluations for IO and an additional m evaluations for EO. The last row and column show the maximum improvement achieved by each optimization strategy compared to the baseline (no IO and/or no EO).

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy across 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using the PaLM 2 language model. The table shows the impact of different EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, and Mutation) when combined with different IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, and OPRO). The color-coding of the cells represents the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations). Gray indicates no cost, blue indicates 32 evaluations, and orange represents iterative optimization of exemplars on top of already optimized instructions.

This table presents the average BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy across 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. The rows represent different IO methods (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO), while the columns show different EO methods (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation). The last row and column highlight the maximum accuracy improvement achieved by using either EO or IO, respectively, compared to the baseline (No IO and No EO). The shading of cells indicates the computational cost, with gray representing no cost, blue representing 32 prompt evaluations for iterative optimization, and orange representing iterative exemplar optimization on top of instruction optimization.

This table presents the average performance across all BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks for 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. It shows the performance gains from using different EO methods (random, nearest neighbor, diversity, random search, and mutation) in combination with different IO methods (no IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, and OPRO). The color-coding indicates the computational cost of each combination, with gray representing no cost, blue representing a cost of 32 prompt evaluations, and orange representing a cost of 32 prompt evaluations for IO plus an additional m evaluations for EO. The last row and column show the maximum improvement achieved for each method over the baselines (no IO and/or no EO).

This table presents the average performance across all BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks for 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using the PaLM 2 language model. It shows how different exemplar selection and instruction optimization techniques impact the model’s performance, both individually and in combination. The color-coding indicates the computational cost for each combination, with gray representing no extra evaluations, blue indicating 32 evaluations for either IO or EO, and orange indicating 32 additional evaluations for EO on top of an already optimized instruction.

This table presents the average performance across various BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks for different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using the PaLM 2 model. The table shows the impact of each method individually and in combination. The color-coding of cells indicates the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations), ranging from zero (gray) for methods without iterative optimization to 32 (blue) for those with iterative optimization of either instructions or exemplars, and finally to 32 (orange) for those that iterate on both.

This table presents the average performance of various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods on the BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) benchmark using PaLM 2. It shows the impact of using different EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, and Mutation) in conjunction with different IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, and OPRO). The table highlights the maximum performance gain achieved by each EO strategy and by combining IO and EO, indicating the cost (number of prompt evaluations) for each approach. The color-coding of the cells provides a visual representation of the computational cost.

This table presents the average BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy scores achieved by combining various instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. It shows the performance gains from using each method alone and in combination. The color-coding highlights the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations on the validation set). Gray indicates no cost, blue indicates 32 evaluations, and orange indicates iterative optimization of exemplars (32 evaluations per iteration). The last row and column show the maximum accuracy improvement compared to baselines (No IO/No EO).

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy across 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. The table shows the impact of various EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation) combined with various IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO) on the model’s performance. The color-coding highlights the computational cost of each combination, with gray representing no additional evaluations, blue representing 32 evaluations for iterative optimization, and orange representing iterative exemplar optimization on top of optimized instructions. The last row and column show the maximum accuracy improvement compared to baselines (No IO/No EO).

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy across 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. It compares using no IO/EO, various state-of-the-art IO methods (APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO), and multiple EO methods (Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation). The color-coding of cells represents the computational cost: gray (no cost), blue (32 evaluations), orange (more than 32 evaluations). The last row and column show the maximum accuracy gain compared to the baseline of no IO and no EO, respectively.

This table presents the average BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy results across various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using the PaLM 2 language model. It shows the impact of different EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation) when combined with different IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO). The table highlights the maximum accuracy gain achieved by using EO and/or IO compared to a baseline with no optimization. The color-coding of the cells indicates the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations on the validation set) for each approach.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy across 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using the PaLM 2 language model. It shows the impact of using different EO methods (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation) in conjunction with various IO methods (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO). The table highlights the maximal accuracy gains achieved by both EO and IO alone and in combination, indicating the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) associated with each method. The color-coding of the cells visually represents the computational cost for each combination.

This table presents the average BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy results across various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using PaLM 2. It shows the impact of using different EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, and Mutation) in combination with different IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, and OPRO). The color-coding helps visualize the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) for each combination.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy results across various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using PaLM 2. It shows the impact of different EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation) combined with different IO methods (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO). The table highlights the maximum accuracy gains achieved by using either EO or IO alone, and also the synergy obtained by combining both, considering the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations).

This table presents the average performance across BIG-Bench Hard (BBH) tasks for various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using PaLM 2. It shows the impact of different EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation) combined with different IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO). The table highlights the maximum performance gains achieved by using EO and/or IO compared to the baseline (No IO and No EO). The background colors help visualize the computational cost associated with each method, with gray indicating no cost, blue indicating moderate cost, and orange indicating high cost.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy results for 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using the PaLM 2 language model. It shows the impact of various EO strategies (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, and Mutation) when combined with various IO strategies (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO). The table highlights the maximal accuracy gains achieved by using EO and/or IO compared to the baseline (No IO, No EO), and uses color-coding to represent the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) for each combination.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy for various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using PaLM 2. It shows the maximum accuracy gains achieved by using either EO or IO alone, and by combining them. The color-coding highlights the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) for each method.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy scores achieved by combining various instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods. It shows the impact of each method individually and in combination. The table highlights the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) for each combination, categorized into no cost (gray), moderate cost (blue), and high cost (orange). The last row and column indicate the maximum accuracy improvement achieved by using EO and/or IO, respectively.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy scores for various combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using PaLM 2. It shows the impact of combining different IO and EO techniques on model performance. The color-coding of the cells indicates the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) associated with each combination, facilitating a cost-benefit analysis of different APO strategies.

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy for 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using PaLM 2. It shows the maximum accuracy gain achieved by using EO and/or IO compared to the baseline (no IO, no EO). The color-coding of the cells represents the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations): gray (no cost), blue (32 evaluations), orange (iterative optimization of exemplars on top of optimized instructions).

This table presents the average Big-Bench Hard (BBH) accuracy for 30 different combinations of instruction optimization (IO) and exemplar optimization (EO) methods using the PaLM 2 language model. It shows the impact of using various EO methods (No EO, Random, Nearest, Diversity, Random Search, Mutation) in combination with various IO methods (No IO, APE, ProTeGi, PromptAgent, OPRO). The maximum improvement achieved by applying EO and IO methods is also presented. The background color-coding helps in understanding the computational cost (number of prompt evaluations) associated with each combination.

Full paper#