↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional dimension reduction techniques often fall short when dealing with datasets exhibiting a contrastive structure—data split into foreground (case/treatment) and background (control) groups. This is particularly true in biomedicine and similar fields, where researchers often need to isolate the unique characteristics of the foreground group. Existing contrastive dimension reduction (CDR) methods lack a rigorous framework for determining when these methods should be applied, and how to quantify this unique information.

This paper addresses these gaps by introducing a hypothesis test to confirm the existence of unique foreground information and a novel contrastive dimension estimator (CDE) to quantify it. The effectiveness of these methods is rigorously validated through simulated, semi-simulated, and real-world experiments using a variety of data types, including images, gene and protein expressions, and medical sensor data. The results show these methods reliably identify unique foreground information across different applications, offering a more robust and comprehensive approach to CDR.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limitations of traditional dimension reduction methods in handling contrastive data, a common scenario in various fields like biomedicine. By proposing a hypothesis test and a contrastive dimension estimator, it provides a rigorous framework for identifying unique foreground information, paving the way for more effective contrastive dimension reduction techniques and enhanced data analysis. The theoretical support and real-world validations further bolster its significance for researchers seeking to uncover unique patterns within complex datasets.

Visual Insights#

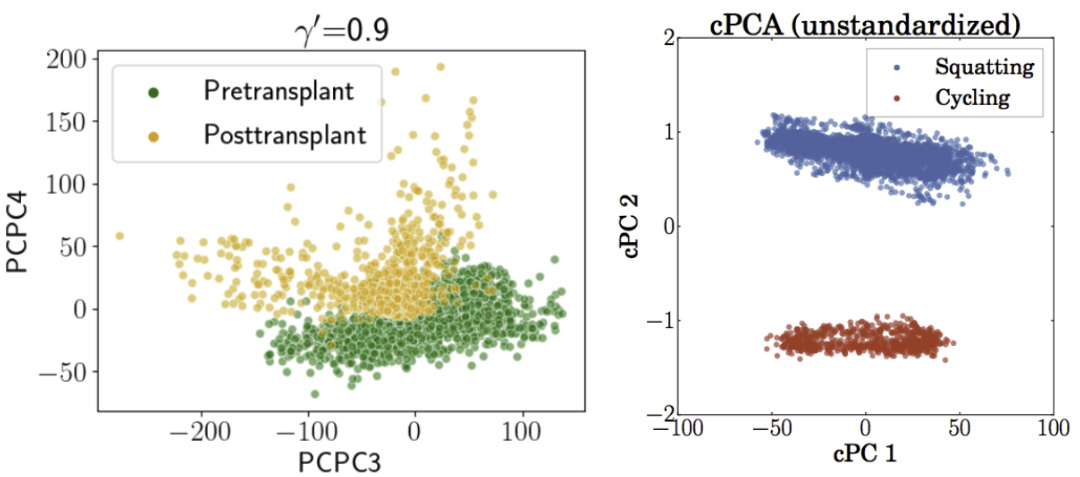

This figure shows the results of applying two contrastive dimension reduction methods, PCPCA and cPCA, to two real-world datasets: BMMC and mHealth. The left panel displays the PCPCA results for the BMMC (bone marrow mononuclear cells) dataset, illustrating the separation of pre- and post-transplant groups using the third and fourth principal components. The right panel presents the cPCA results for the mHealth dataset, showcasing how a single direction effectively distinguishes subgroups (squatting or cycling vs. lying down). This visualization demonstrates the ability of contrastive methods to uncover low-dimensional structures unique to foreground groups.

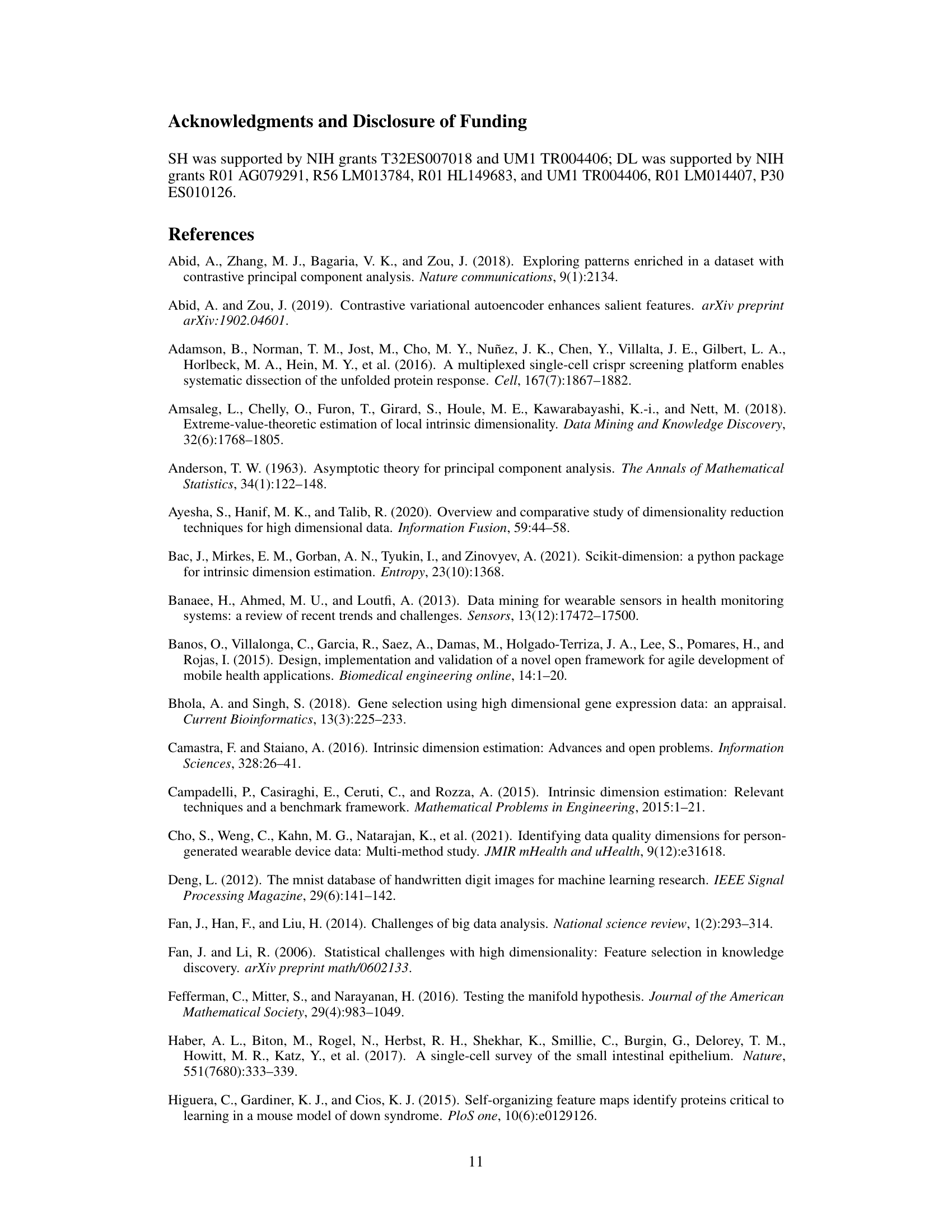

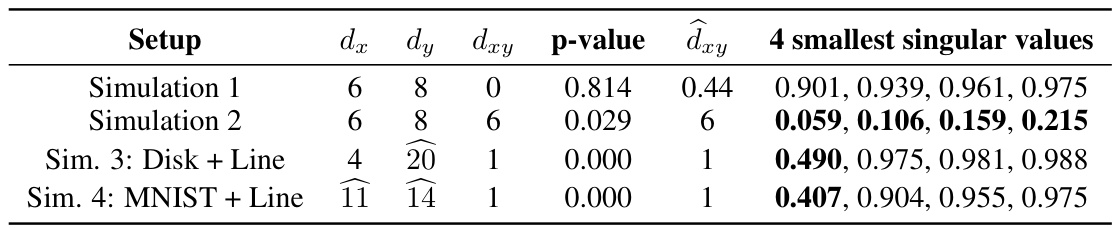

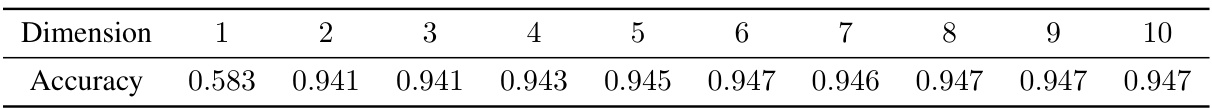

This table summarizes the results of four different simulation experiments. For each simulation, it shows the setup (including foreground and background dimensions), the true contrastive dimension (dxy), the p-value from the hypothesis test for contrastive information, the estimated contrastive dimension (dxy hat), and the four smallest singular values. The simulations test different scenarios to evaluate the accuracy of the methods in identifying and quantifying contrastive information under various conditions.

In-depth insights#

Contrastive DR#

Contrastive Dimension Reduction (CDR) tackles the challenge of dimensionality reduction in datasets exhibiting a contrastive structure, specifically where data is partitioned into foreground (e.g., treatment) and background (e.g., control) groups. Traditional DR methods often fail to effectively capture information unique to the foreground group, which is frequently the primary focus of analysis. CDR aims to address this by identifying and quantifying features that distinguish the foreground group from the background. This involves not only reducing dimensionality but also emphasizing the contrastive aspects of the data. A key challenge in CDR is determining when such contrastive information meaningfully exists and how to quantitatively assess its extent. Effective CDR methods require careful consideration of the underlying data structure and often involve advanced statistical and computational techniques to isolate the meaningful features while filtering out noise and shared aspects between groups. The development of robust hypothesis tests and dimension estimators are crucial to provide a principled framework for the application of CDR and ensure its outcomes are trustworthy and meaningful.

Hypothesis Testing#

The hypothesis testing section of this research paper is crucial for establishing the validity of the proposed contrastive dimension reduction methods. The authors cleverly design a bootstrap-based hypothesis test to address the core question: does unique information exist in the foreground group relative to the background? This innovative approach uses principal angles between subspaces to quantify contrastive information and determine whether this information surpasses a threshold defined by the null hypothesis. A significant advantage is its flexibility; it can accommodate diverse data types and doesn’t impose strong assumptions on the data’s distribution. The test’s conservative nature, while limiting the false positive rate, might lead to some valid signals being missed, highlighting a key limitation that warrants exploration in future works. Nevertheless, its foundational role in validating the proposed methods, particularly in conjunction with the contrastive dimension estimator, underscores its importance in the paper’s overall contribution.

CDE Estimation#

The core of the proposed methodology centers around the Contrastive Dimension Estimator (CDE). CDE tackles the challenge of quantifying the unique information present in a foreground group compared to a background group. This is achieved by leveraging principal angles, which measure the difference between the linear subspaces representing the foreground and background. A key innovation is the introduction of a threshold parameter (ε) to distinguish between shared and unique information. By identifying principal angles exceeding ε, CDE accurately estimates the contrastive dimension (dxy), which signifies the number of unique dimensions in the foreground. The theoretical underpinnings of CDE are robust, supported by proofs demonstrating consistency and providing finite-sample error bounds. This ensures both reliability and a measure of uncertainty in estimates. The effectiveness of CDE is empirically validated through simulations and real-world applications on diverse datasets, showcasing its ability to identify unique information and provide valuable insights for contrastive dimension reduction techniques.

Simulations#

The simulations section is crucial for validating the proposed methods. The authors cleverly designed four distinct simulations: two purely synthetic scenarios (one with null contrastive dimension, the other with a known non-zero dimension), and two semi-synthetic scenarios combining synthetic data with real-world noise (grassy images and MNIST digits). This multifaceted approach rigorously tests the methods’ robustness and ability to discern true contrastive information from noise. The use of both synthetic and semi-synthetic data is particularly insightful; it bridges the gap between idealized testing and real-world application, offering a more realistic evaluation of the methods’ performance. The inclusion of known ground truth in some simulations allows for direct assessment of accuracy, while the semi-synthetic settings gauge performance in more complex, ambiguous situations. The results presented are comprehensive and provide a clear picture of the methods’ strengths and limitations, highlighting areas where further investigation might be beneficial, such as the selection of a suitable tolerance threshold and examination of the method’s robustness to non-linear structures.** The overall approach in the simulations section is very well structured and effective in comprehensively evaluating the proposed hypothesis test and contrastive dimension estimator.

Real Data#

The ‘Real Data’ section of a research paper is crucial for validating the proposed methods. It demonstrates the practical applicability and generalizability of the theoretical findings to real-world scenarios. A strong ‘Real Data’ section would showcase diverse datasets, carefully selected to represent various characteristics and challenges. The analysis should go beyond simple application, delving into the interpretation of results in the context of the data’s domain. Detailed descriptions of the datasets used, including their sources, preprocessing steps, and limitations, are essential for reproducibility and transparent assessment. Comparisons with existing methods on the same datasets strengthen the claims of novelty and improvement. Importantly, a nuanced discussion of the results, highlighting both successes and limitations, demonstrates a thoughtful understanding of the method’s capabilities and potential weaknesses. Acknowledging limitations is crucial for responsible research and fosters trust in the validity of the findings. The ‘Real Data’ analysis ultimately determines the impact and potential of the research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

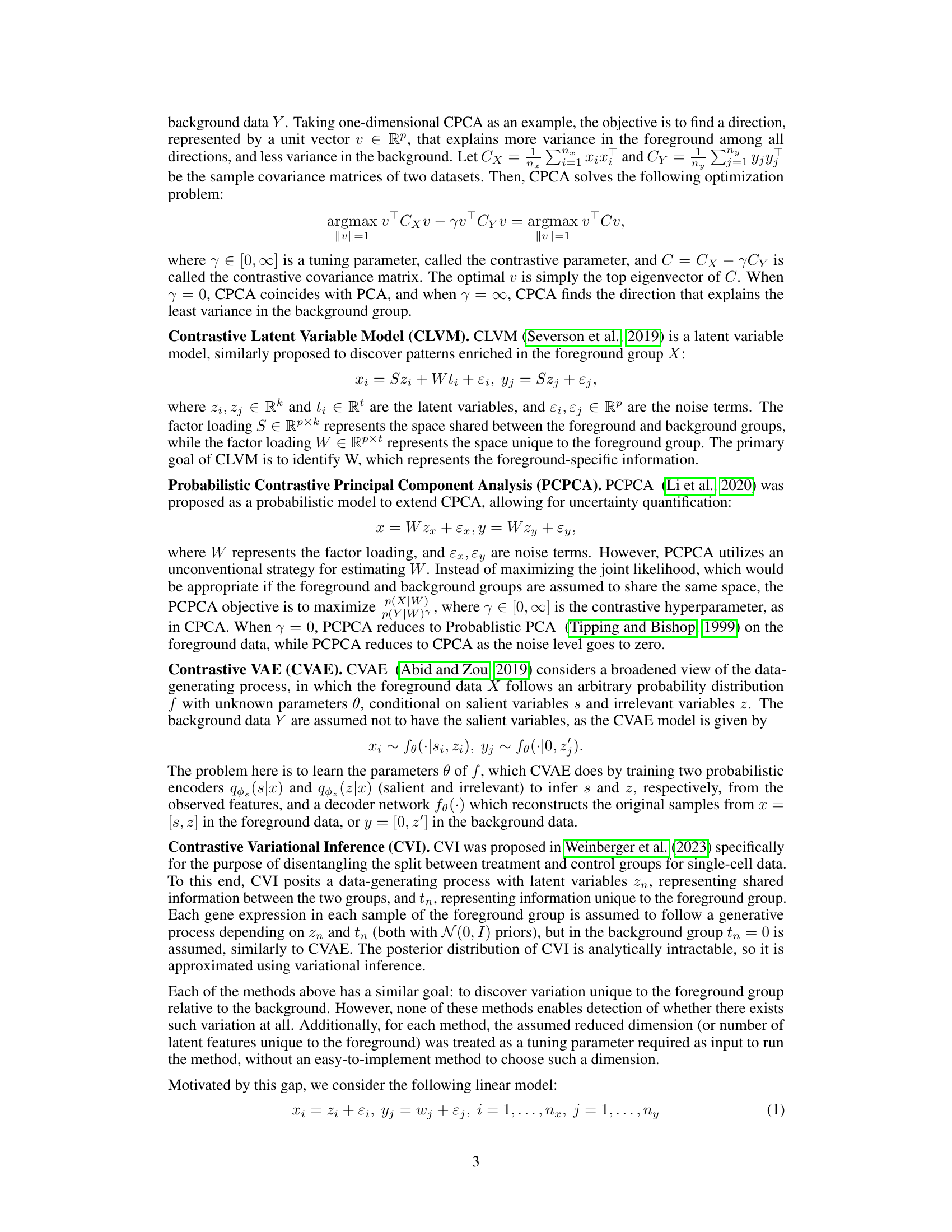

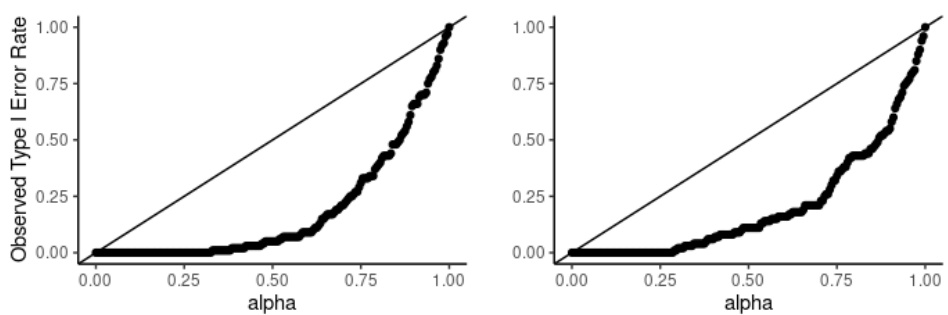

This figure displays two plots showing the Type I error rate of the hypothesis test proposed in the paper. The Type I error rate is the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true. Each plot shows the observed Type I error rate against the significance level (alpha) for a different sample size. The left plot shows the results for samples of size 100 (nx = ny = 100), and the right plot shows the results for samples of size 200 (nx = ny = 200). The plots demonstrate the conservative nature of the test, meaning that the observed Type I error rate is consistently below the significance level.

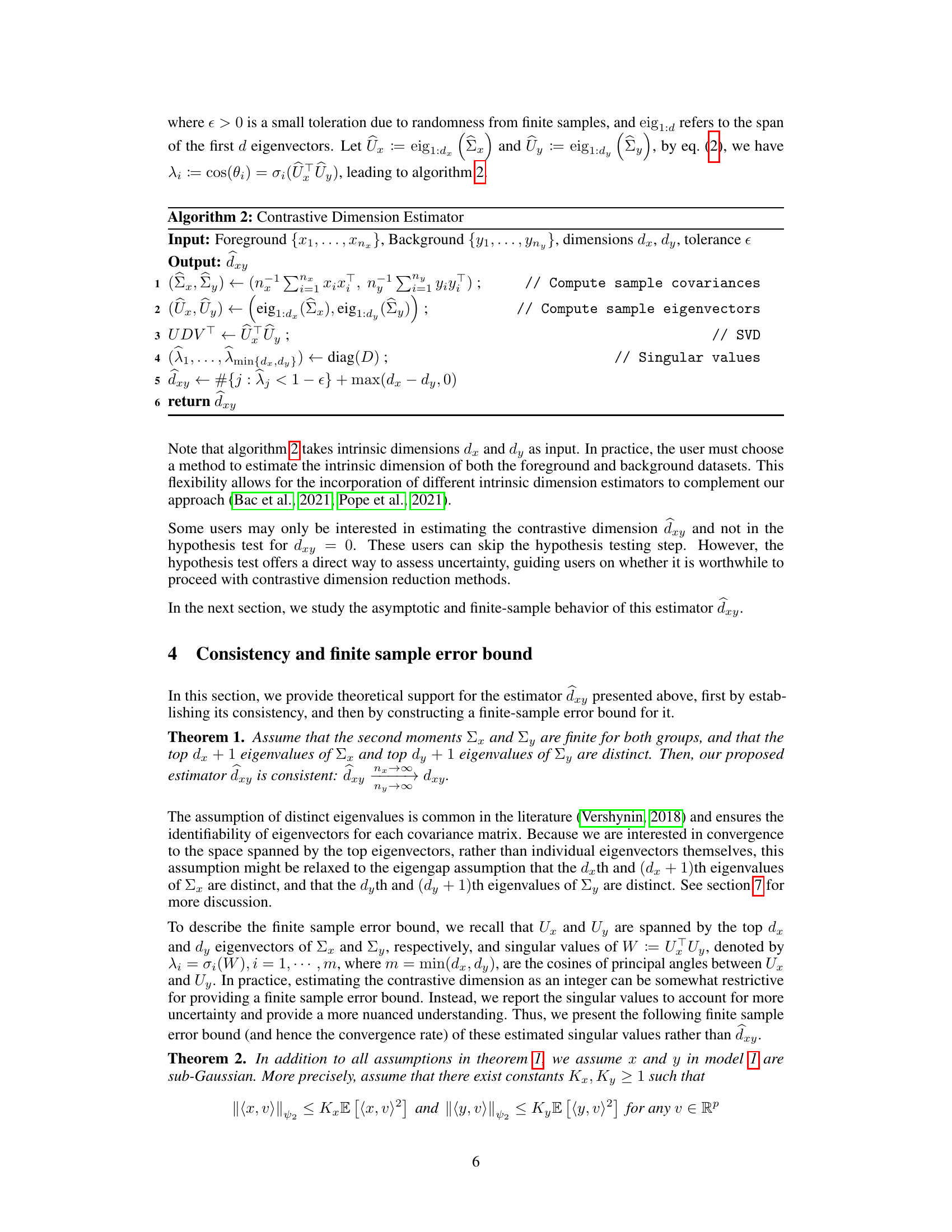

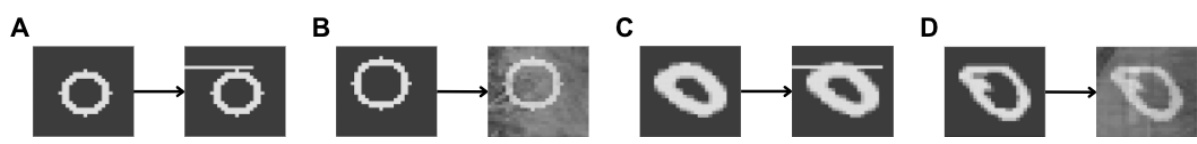

This figure displays sample images from the Corrupted MNIST dataset used in the paper’s experiments. The top row shows examples of images in the foreground group (handwritten digits with added noise), and the bottom row shows examples of images from the background group (noise only, no digits). This visualization helps illustrate the type of data used in the contrastive dimension reduction methods, where the goal is to identify patterns in the foreground group that are distinct from the background.

This figure shows the results of applying PCPCA (Probabilistic Contrastive Principal Component Analysis) to the BMMC (Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells) dataset and cPCA (Contrastive Principal Component Analysis) to the mHealth dataset. The left panel displays the PCPCA results for the BMMC data, showing the pre- and post-transplant groups separated along the PCPC3 and PCPC4 axes. The right panel shows the cPCA results for the mHealth data, with the squatting and cycling activities clearly separated along the first two cPCA components. This visualization demonstrates the effectiveness of these contrastive dimension reduction techniques in separating groups of interest from control groups within high-dimensional datasets.

This figure shows sample images from the corrupted MNIST dataset used in the paper’s experiments. The top row displays images from the foreground group, while the bottom row shows images from the background group. The foreground images are handwritten digits (0 and 1) superimposed on grassy noise. The background images contain only the grassy noise.

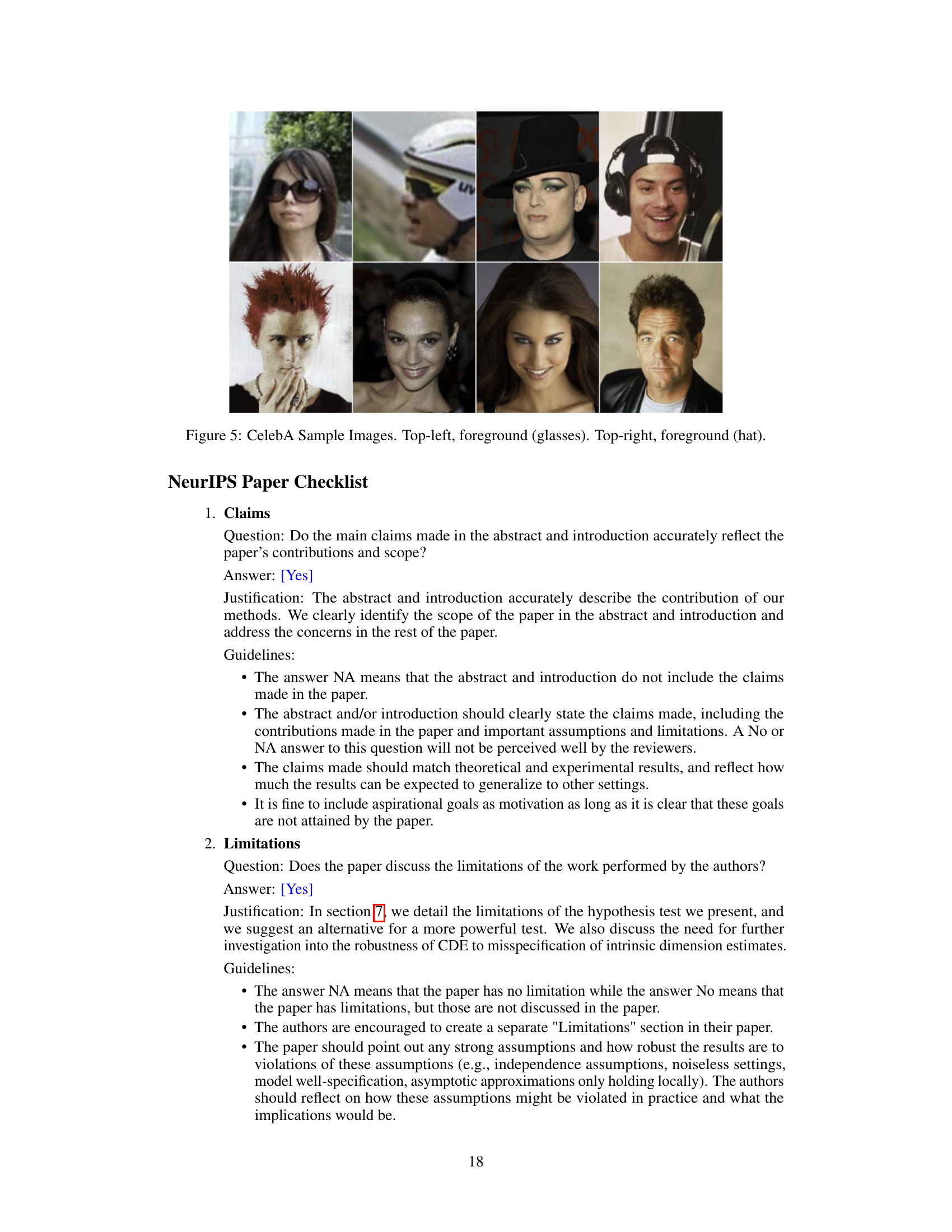

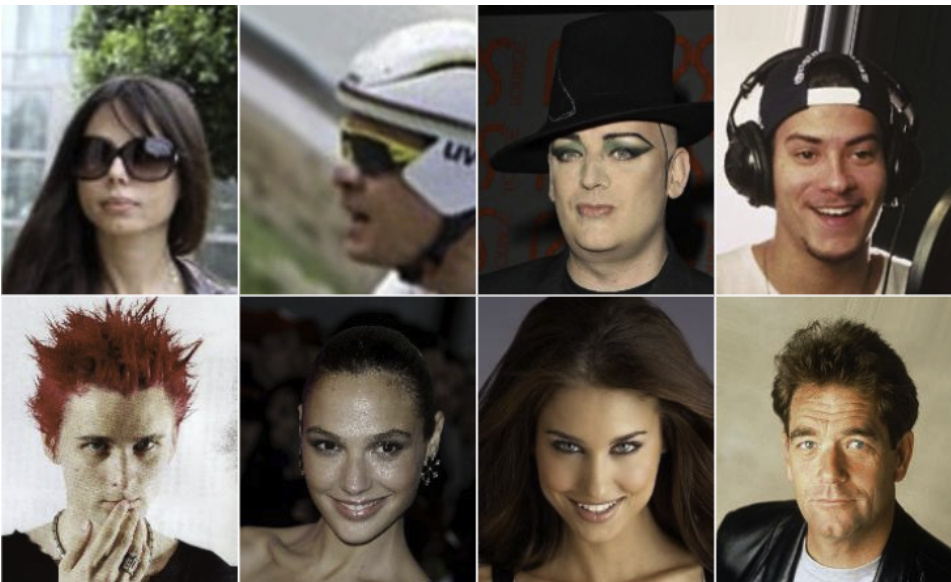

This figure shows sample images from the CelebA dataset used in the paper’s real data experiments. The top row displays images from the foreground group (celebrities wearing glasses and hats), while the bottom row shows images from the background group (celebrities without glasses or hats). The images are used to illustrate the application of the proposed methods to real-world image data.

More on tables

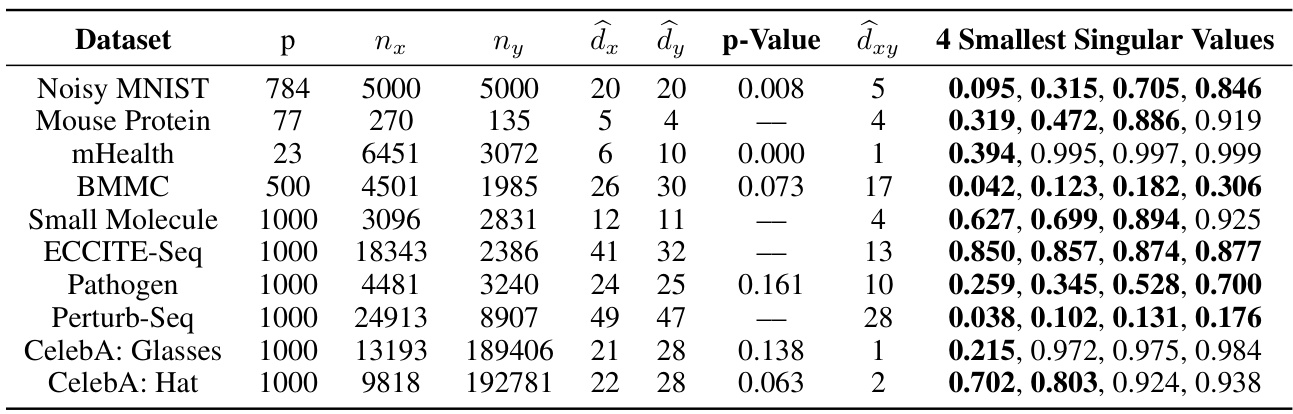

This table presents the results of applying the proposed contrastive dimension reduction methods to various real-world datasets. For each dataset, it shows the dimensionality (p), the number of samples in the foreground (nx) and background (ny) groups, the estimated intrinsic dimensions for foreground (dx) and background (dy) groups, the p-value from the hypothesis test, the estimated contrastive dimension (dxy), and the four smallest singular values from the analysis. The table provides a summary of the performance and findings for each dataset, illustrating the ability of the methods to identify contrastive information and estimate the contrastive dimension.

This table presents the results of applying the proposed contrastive dimension reduction methods to several real-world datasets. For each dataset, it shows the dimension (p), number of foreground (nx) and background (ny) samples, estimated intrinsic dimensions of foreground (dx) and background (dy) groups, p-value from the hypothesis test, estimated contrastive dimension (dxy), and the four smallest singular values. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the methods across diverse datasets and highlight the unique information in the foreground data.

This table summarizes the results from four different simulation experiments. For each simulation, it shows the setup (dx, dy), the true contrastive dimension (dxy), the p-value from the hypothesis test, the estimated contrastive dimension (dxy), and the four smallest singular values. The simulations test different scenarios including null cases (dxy=0) and cases where contrastive information is present (dxy>0). It helps assess the performance and accuracy of the proposed hypothesis test and contrastive dimension estimator.

Full paper#