↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Zero-Shot Object Goal Navigation (ZS-OGN) is crucial for real-world robots to interact with diverse objects without prior training. Existing approaches often rely solely on categorical semantic information, which struggles with partial object observations or lacks detailed environment representation. This leads to inaccurate navigation guidance and limits robot autonomy.

GAMap tackles these issues by integrating object parts and affordance attributes as navigation guidance, employing a multi-scale scoring approach for comprehensive geometric and functional representation. Experiments on HM3D and Gibson datasets demonstrate improvements in Success Rate and Success weighted by Path Length, showing enhanced robot autonomy and versatility without needing object-specific training. The project’s availability further fosters reproducibility and encourages community involvement.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents GAMap, a novel method for zero-shot object goal navigation that significantly improves navigation success rates. It addresses limitations of existing methods by incorporating geometric parts and affordance attributes into a multi-scale scoring approach, thus enhancing robot autonomy and versatility in unseen environments. This opens new avenues for research in embodied AI and robotics, particularly in areas needing robust and adaptable navigation capabilities.

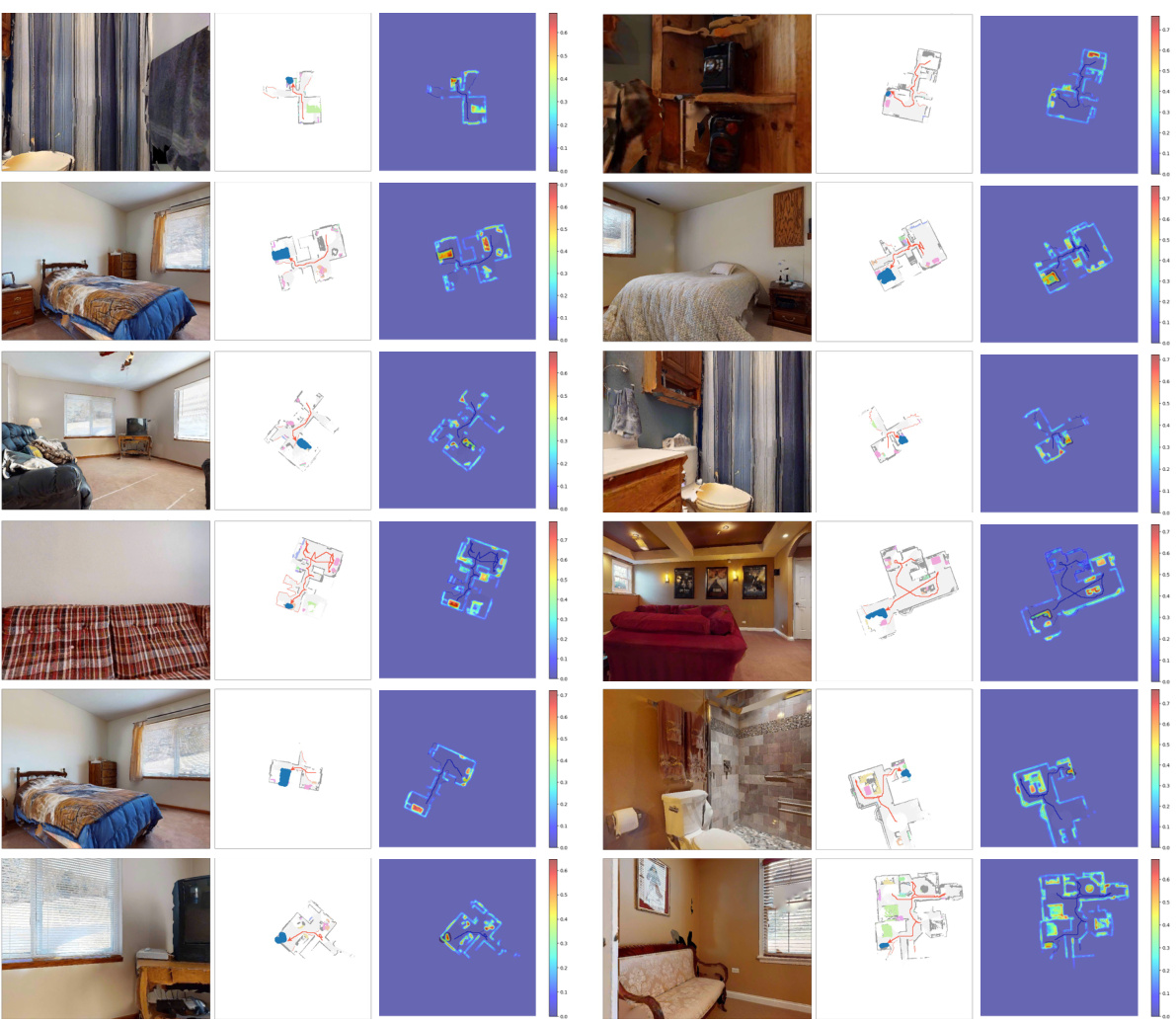

Visual Insights#

This figure compares the performance of the proposed GAMap method and a traditional method in a zero-shot object goal navigation task. The leftmost image shows the same visual input to both methods. The top row illustrates the GAMap’s ability to identify the chair back (a geometric part) and use this information for successful navigation. The bottom row shows the traditional method failing to detect this crucial part and consequently failing to reach the target. Red circles highlight the chair’s location, with high GA scores (Geometric-Affordance scores) in the GAMap indicating successful localization.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GAMap method against various state-of-the-art and baseline Zero-Shot Object Goal Navigation (ZS-OGN) methods. The comparison is done using two metrics: Success Rate (SR) and Success weighted by Path Length (SPL) on the HM3D and Gibson benchmark datasets. Each method is categorized by whether it uses zero-shot learning, locomotion training, and semantic training, providing context for the results. The table clearly shows that GAMap outperforms existing methods on both SR and SPL.

In-depth insights#

ZS-OGN Methods#

Zero-Shot Object Goal Navigation (ZS-OGN) methods predominantly grapple with the challenge of enabling robots to navigate towards unseen objects without requiring prior training. Traditional approaches often rely on semantic information, such as object categories, which proves insufficient when dealing with partial observations or lacks detailed environmental representations. More advanced methods leverage deep learning models, directly mapping sensor data to actions or using map-based navigation with learned representations. However, these approaches often suffer from data limitations, leading to poor generalization to unseen environments. A key area of improvement lies in integrating multi-scale features, moving beyond single-scale representations, and leveraging richer scene understanding. The effectiveness of ZS-OGN methods hinges on the capability to reason about geometric object parts, affordances, and their contextual relationships within the environment. Future research should focus on the integration of robust multi-modal data sources (vision, language, depth) along with advanced reasoning capabilities to enable robust and versatile navigation in complex and unstructured environments.

GAMap’s Design#

GAMap’s design cleverly integrates multi-scale geometric and affordance attributes for zero-shot object goal navigation. Multi-scale processing of visual input, using a CLIP model, allows the system to capture fine-grained details alongside global context, overcoming limitations of single-scale approaches. This is crucial for handling partially observed objects or cluttered environments. The incorporation of affordance attributes, in conjunction with geometric parts, enhances the semantic understanding of object interaction, providing a richer guidance signal than category-based methods. Furthermore, the use of a pre-trained CLIP model, rather than object-specific training, enables zero-shot generalization across diverse unseen object categories. Integration of LLM-generated attributes with the multi-scale visual features ensures effective reasoning and navigation, highlighting the synergistic power of combining large language models with vision processing. The overall architecture balances the need for detailed scene understanding with efficient real-time processing, making it suitable for robotic applications.

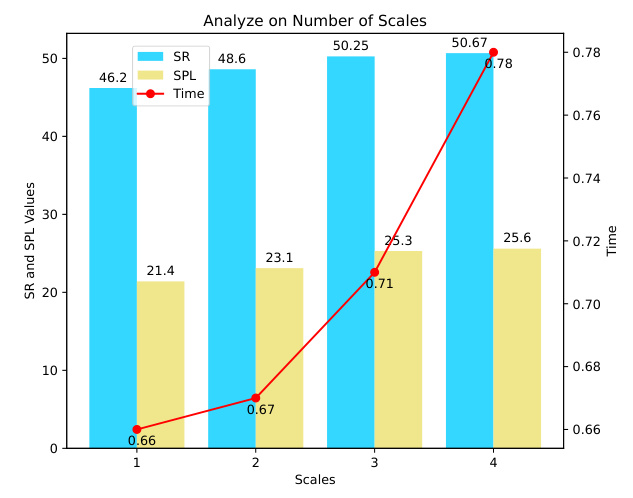

Multi-Scale Scoring#

The concept of “Multi-Scale Scoring” in object goal navigation is crucial for robust performance. By analyzing visual information at multiple scales, the algorithm gains a richer understanding of the target object’s appearance, regardless of its distance or occlusion. This multi-scale approach is vital because it addresses limitations of single-scale methods, which often fail to accurately identify objects due to partial observation or scale variation. It’s particularly beneficial in zero-shot scenarios where no object-specific training data is available. The algorithm likely uses a hierarchical image partitioning technique, creating image patches at different resolutions. Each patch is scored for its similarity to the target object’s features using a pre-trained model like CLIP. The scores across multiple scales are then aggregated (perhaps by averaging or taking the maximum) to obtain a robust final score for each region in the scene. This comprehensive score incorporates both fine-grained details from high-resolution patches and broader contextual information from low-resolution patches, leading to more accurate and reliable object localization. This allows for a more effective navigation strategy and enhanced robustness in handling real-world challenges. The integration of multi-scale scoring significantly improves the reliability and efficiency of zero-shot object goal navigation.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically investigates the contribution of individual components within a machine learning model. For the GAMap model, this would involve removing or deactivating specific elements (e.g., geometric parts, affordance attributes, multi-scale scoring) to observe their impact on performance metrics (Success Rate, Success weighted by Path Length). The results of such an ablation study would help determine the relative importance of each component and justify design choices. For example, significantly decreased performance when removing geometric parts would highlight their crucial role in object localization, guiding future model enhancements. Furthermore, ablation studies help optimize the model’s complexity by identifying potentially redundant or less influential features. The study’s findings are useful to understand the overall architecture and potentially refine or simplify it without significant performance loss. In the context of GAMap, it would provide insights into whether the combined use of geometric and affordance attributes yields superior results compared to using either alone, leading to potential improvements in model design.

Future Works#

The paper’s potential future directions are compelling. Improving the robustness of the multi-scale attribute scoring is key; current reliance on CLIP for visual embedding might be improved by exploring alternative architectures that incorporate more nuanced object representations. Further investigation into LLM prompting strategies to elicit more comprehensive and precise geometric part and affordance attributes would enhance the system’s accuracy. While the LLM and VLM combination demonstrates promise, optimizing the interplay between these models to minimize computational overhead, perhaps through efficient model distillation techniques, is crucial for real-world application. Extending GAMap’s functionality to handle more complex scenes with significant occlusion or cluttered environments would be valuable. Finally, incorporating a more sophisticated exploration policy beyond FMM, potentially integrating reinforcement learning for improved path efficiency, is a crucial area for future exploration. Real-world testing in diverse environments is needed to further validate GAMap’s generalizability and robustness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

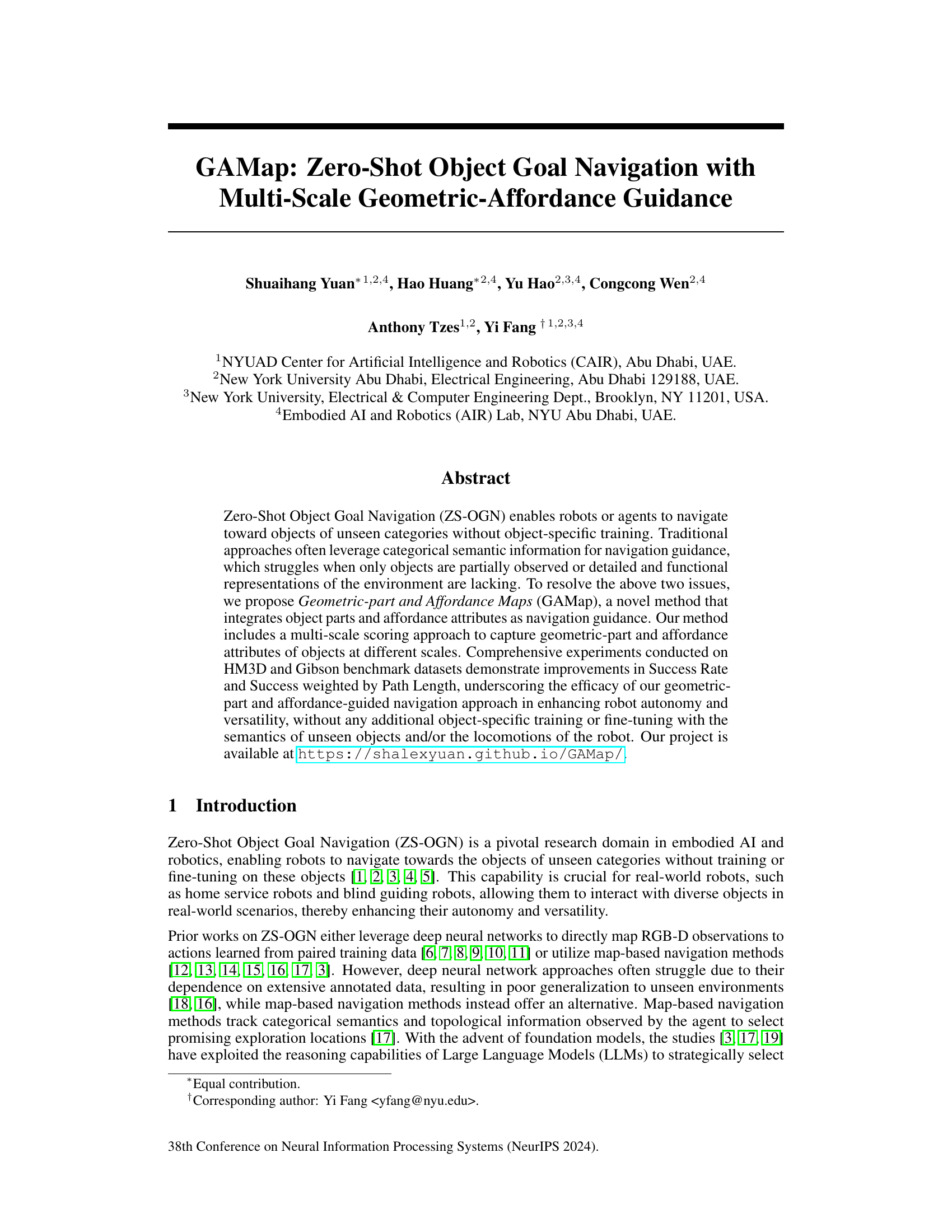

This figure illustrates the process of generating the Geometric-Affordance Map (GAMap). It starts with an LLM (Large Language Model) generating geometric parts and affordance attributes for a target object (e.g., a chair). The RGB-D observation from the robot’s camera is partitioned into multiple scales. A CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) visual encoder processes these to produce multi-scale visual embeddings. These embeddings are compared (cosine similarity) with attribute text embeddings (also from CLIP) to calculate GA (Geometric-Affordance) scores. These scores are averaged across scales and projected onto a 2D grid to create the GAMap, which guides the robot’s navigation.

This heatmap shows the results of ablation studies varying the number of affordance attributes (Na) and geometric attributes (Ng). The color intensity represents the change in success rate (SR), with darker colors showing larger decreases. Red lines show the time cost increase for each combination of Na and Ng. The study shows a trade-off between improved performance with more attributes and increased computational cost.

This figure illustrates the process of generating the Geometric-Affordance Map (GAMap). It starts with an LLM generating geometric parts and affordance attributes for the target object. Then, the RGB observation is partitioned into multiple scales. A CLIP visual encoder generates multi-scale visual embeddings for these partitions. These embeddings are compared with the attribute text embeddings (from CLIP’s text encoder) using cosine similarity to obtain GA scores. Finally, these scores are averaged and projected onto a 2D grid to create the GAMap.

This figure compares the performance of two methods for calculating Geometric-Affordance (GA) scores: gradient-based and patch-based. The top row shows the gradient-based method’s heatmaps for armrest, backrest, and seat attributes of a chair, highlighting how it incorrectly focuses on irrelevant areas like the ceiling. The bottom row displays the patch-based method’s heatmaps, demonstrating its superior ability to accurately focus on the relevant chair parts.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed multi-scale approach with GPT-4V in identifying a sofa in a scene. The top row shows how the multi-scale approach successfully identifies the sofa at different scales (a close-up view of the sofa, a wider view including the sofa and surrounding furniture, and a long shot of the whole room), while GPT-4V fails to detect the sofa, even though the sofa is quite visible in the images.

This figure illustrates the process of generating the Geometric-Affordance Map (GAMap). It starts with an LLM generating geometric parts and affordance attributes for a target object. The RGB observation is then divided into multiple scales, and a CLIP visual encoder creates visual embeddings for each scale. These embeddings are compared to the attribute text embeddings (also from CLIP) to produce GA scores. Finally, these scores are averaged and mapped onto a 2D grid to create the GAMap, which guides the navigation.

This figure illustrates the process of generating the Geometric-Affordance Map (GAMap). It starts with an LLM generating geometric parts and affordance attributes for a target object. The RGB observation from the robot is then divided into multiple scales, and CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) is used to create visual embeddings for each scale. These embeddings are compared to text embeddings of the attributes, resulting in GA scores. These scores are averaged and projected onto a 2D grid to create the GAMap, which guides the robot’s navigation.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of different methods for calculating Geometric-Affordance (GA) scores, including the patch-based method and the gradient-based method. The table shows the average increase in Success Rate (Ave.↑), the maximum increase in Success Rate (Max↑), and the decrease in processing time (Time↓) for each method using different pre-trained encoders (CLIP, BLIP, BLIP-2). The results demonstrate that the patch-based method with CLIP provides the best balance of performance and efficiency.

This table compares the Success Rate (SR) and Success weighted by Path Length (SPL) using three different methods for updating the Geometric and Affordance (GA) scores: Max, Average, and Replacement. The Max method consistently shows the highest performance, while the Average and Replacement methods show decreasing performance. This highlights the effectiveness of the Max method in maintaining and enhancing navigation performance by retaining the maximum scores and benefiting from multiple perspectives during exploration.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GAMap method against several other zero-shot object goal navigation methods on two benchmark datasets, HM3D and Gibson. The comparison is based on two metrics: Success Rate (SR) and Success weighted by Path Length (SPL). It highlights the improvements achieved by GAMap in terms of both accuracy (SR) and efficiency (SPL) compared to existing approaches.

This table compares GAMap with other state-of-the-art zero-shot object goal navigation methods. The comparison highlights key differences in the type of mapping used (categorical vs. affordance+geometric), whether a multi-scale approach was used, whether the method is zero-shot, and whether locomotion or semantic training was used. This allows for a clear understanding of how GAMap differs from existing techniques and what makes it unique.

This table presents the quantitative results of the ablation study on the effectiveness of using different numbers of affordance and geometric attributes in the GAMap approach. It shows the Success Rate (SR) and the time taken (in seconds) for various combinations of Na (number of affordance attributes) and Ng (number of geometric attributes). The data helps in understanding the contribution of each attribute type and how increasing the number of attributes impacts the performance and computational cost.

This table compares the performance of several zero-shot object goal navigation methods on the HM3D and Gibson datasets using Success Rate (SR) and Success weighted by Path Length (SPL) as metrics. It shows that the proposed GAMap method outperforms existing methods on both datasets. The table also categorizes the methods based on whether they use zero-shot learning, locomotion training, and semantic training to highlight the advantages of the GAMap approach.

Full paper#