↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current molecular diffusion models often treat atoms as independent entities, neglecting the crucial information embedded within molecular substructures. This oversight limits the models’ ability to accurately represent and predict molecular properties which are highly dependent on the intricate relationships between atoms within these substructures. This paper tackles this critical limitation by proposing a novel approach.

The proposed model, SubgDiff, directly addresses this issue by incorporating substructural information into a diffusion model framework. It does this using three key techniques: subgraph prediction, expectation state, and k-step same subgraph diffusion. These techniques improve the model’s ability to understand and utilize the relationships between atoms within substructures, ultimately resulting in superior performance on various downstream tasks such as molecular force prediction.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI-based drug discovery and materials science due to its novel approach in molecular representation learning. By addressing the limitations of existing models that ignore substructural dependencies, SubgDiff provides a significant leap forward. This opens avenues for improving molecular property prediction and generation, accelerating drug design and material development.

Visual Insights#

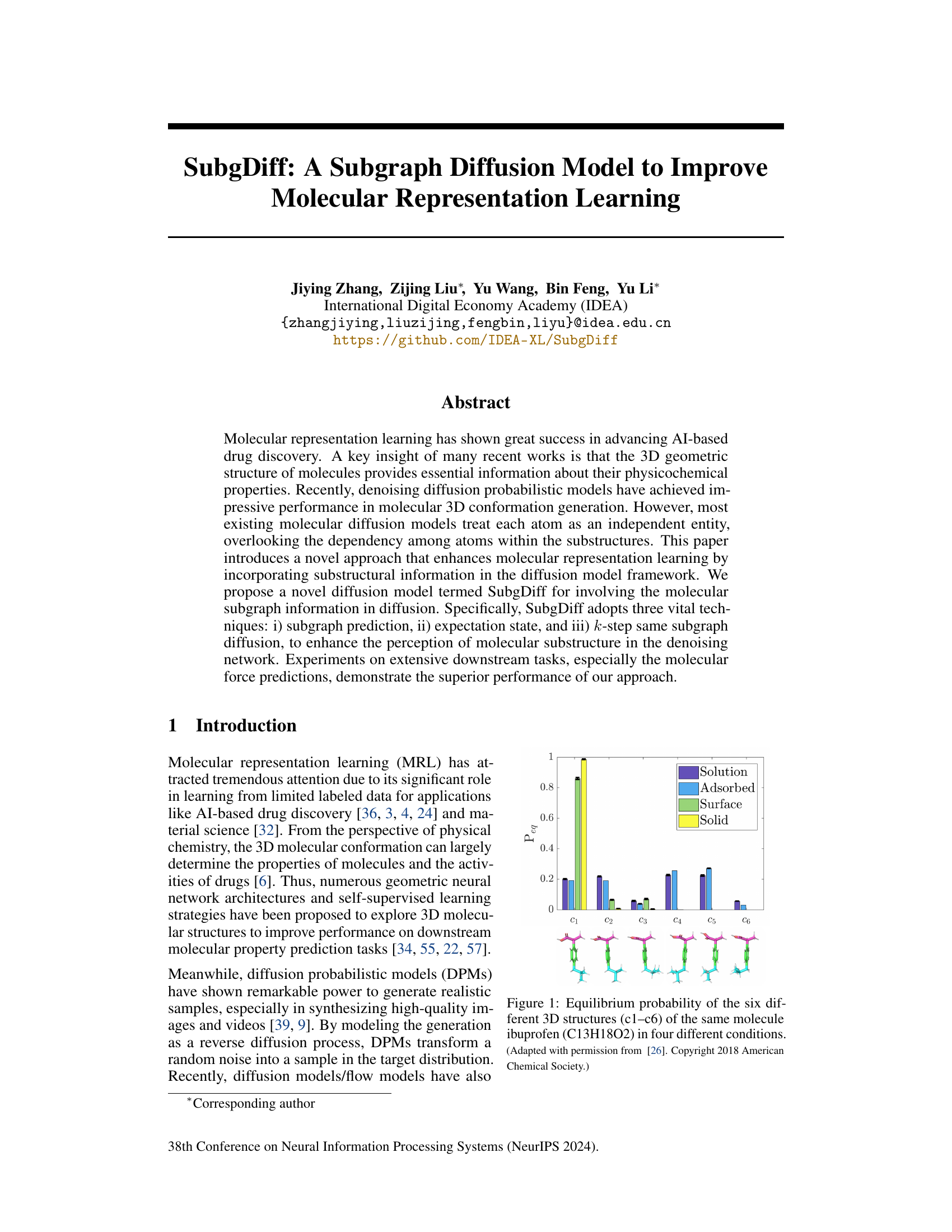

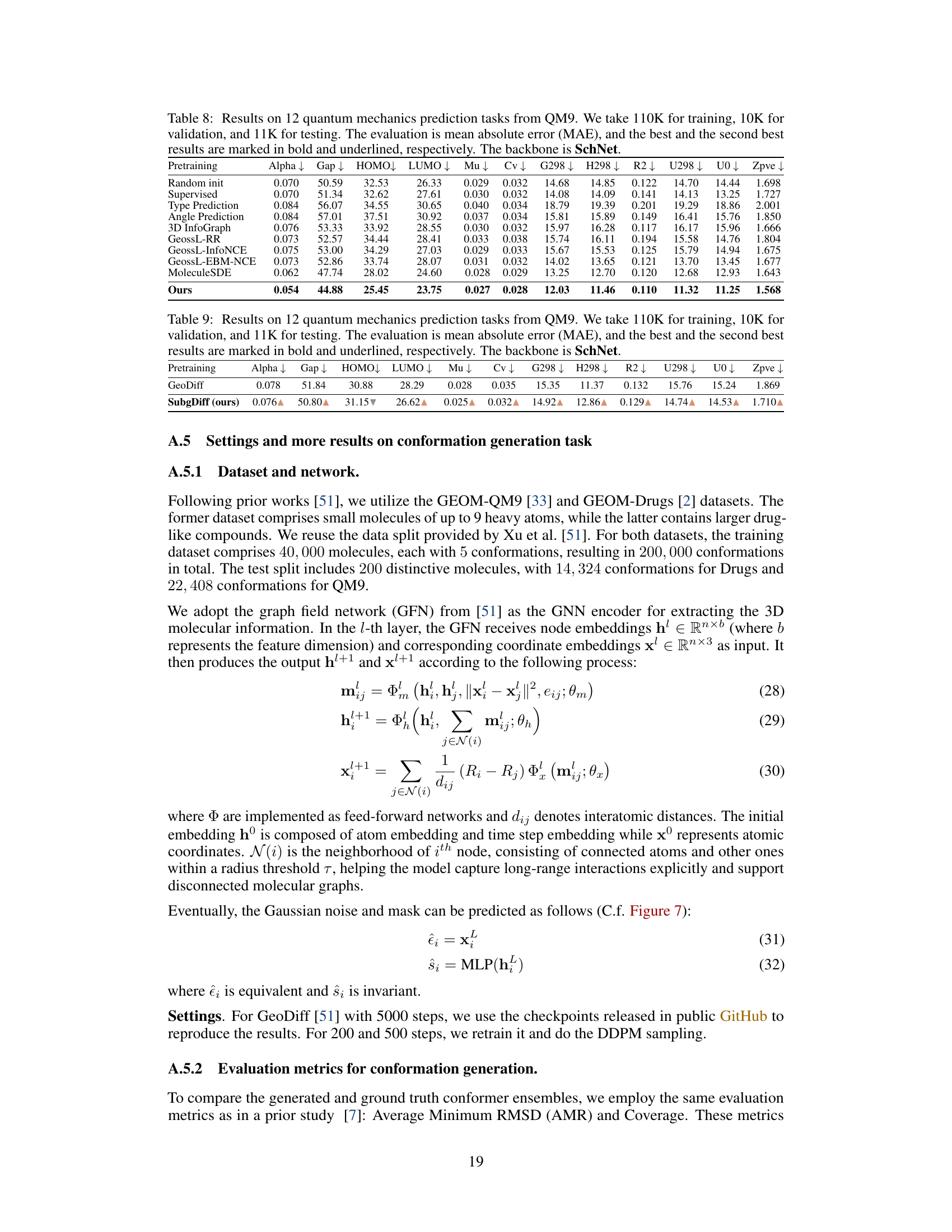

This figure shows the equilibrium probability of six different 3D conformations (c1-c6) of the ibuprofen molecule under four different conditions: solution, adsorbed, surface, and solid. The graph visually demonstrates that the probability distribution of conformations varies significantly depending on the environment. This highlights the importance of considering the 3D structure of molecules and its relationship with the surrounding environment, which is a key motivation for the research presented in the paper.

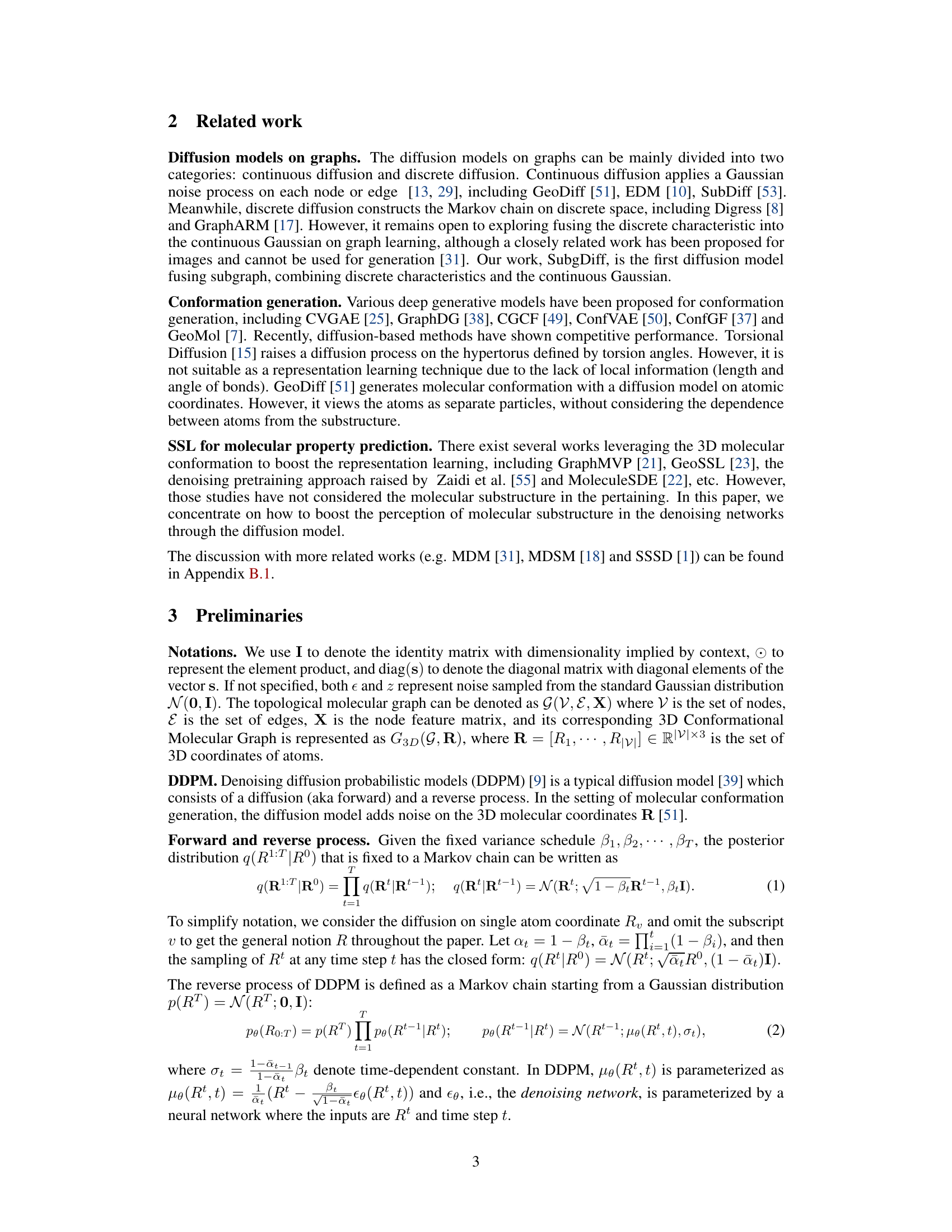

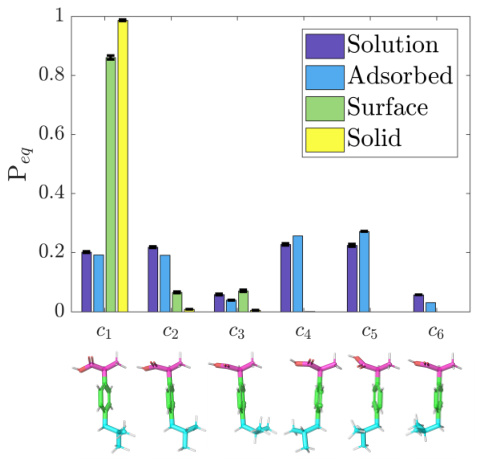

This table presents the mean absolute error (MAE) results for predicting molecular forces on the MD17 dataset. Different molecular representation learning methods are compared, including various self-supervised and contrastive learning techniques. The best and second-best performing methods for each molecule are highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively. The results showcase the effectiveness of SubgDiff in improving molecular representation learning compared to several established baselines.

In-depth insights#

Subgraph Diffusion#

Subgraph diffusion presents a novel approach to molecular representation learning by integrating substructural information into the diffusion model framework. Instead of treating each atom independently, this method focuses on the interdependencies within molecular substructures. By selectively adding noise to specific subgraphs during the diffusion process, the model learns to better capture the relationships between atoms within these crucial structural units. This approach directly addresses the limitations of previous methods which often overlooked these vital dependencies, thereby leading to an improvement in downstream tasks such as molecular force predictions. The key innovation lies in the combination of subgraph selection, expectation state diffusion, and k-step same subgraph diffusion, which enables more efficient training and enhanced sampling capabilities.

Substructural Info#

The concept of “Substructural Info” in molecular representation learning centers on leveraging the inherent relationships between atoms within molecules, going beyond treating each atom as an independent entity. Substructural information, such as the presence of specific functional groups or recurring motifs, significantly impacts a molecule’s properties. Therefore, incorporating this substructural knowledge directly into molecular representation models, as opposed to relying solely on individual atomic features, offers a powerful approach. This is because the overall molecular structure and its physicochemical behavior are highly dependent on the arrangements and interactions of its constituent substructures. By effectively capturing this substructural context, models can learn richer representations that more accurately reflect the true nature of molecules, ultimately improving downstream tasks like property prediction or generative modeling. This approach is particularly relevant in scenarios with limited labeled data, where capturing these underlying structural relationships proves especially valuable for improving model performance and generalization.

3D Conformation#

3D conformation plays a crucial role in determining the properties and functions of molecules. Understanding and predicting 3D conformations is essential for drug discovery, materials science, and other fields. Many methods exist for 3D conformation generation, ranging from traditional physics-based techniques to machine learning approaches. Recent advancements in deep learning, particularly the use of diffusion models, have shown impressive results in generating high-quality 3D molecular structures. However, these models often overlook the relationships between atoms within substructures, treating atoms as independent units. This limitation has motivated the development of innovative models, such as the one presented in the research paper, which explicitly incorporate substructural information to improve both the accuracy and efficiency of 3D conformation generation. These improvements are expected to significantly enhance downstream tasks, such as molecular property prediction and virtual screening, by producing more realistic and relevant 3D models. Future research will likely focus on further refining these methods, incorporating more detailed chemical knowledge, and addressing the challenges related to computational cost and scalability.

Downstream Tasks#

The effectiveness of molecular representation learning models is often evaluated on various downstream tasks, which serve as benchmarks to assess their ability to generalize. These tasks typically involve predicting properties of molecules, such as physicochemical properties (e.g., solubility, polarity, logP), biological activities (e.g., binding affinity, toxicity, enzyme activity), and molecular forces. The choice of downstream tasks is crucial as it dictates the type of information the model learns to capture and ultimately impacts its real-world applicability. A comprehensive evaluation would encompass diverse and challenging tasks, ideally including tasks directly relevant to the intended application, such as drug discovery or materials science. It’s important to analyze performance across different task types to understand the model’s strengths and limitations. Careful selection of datasets is also vital, ensuring that they are large, diverse, and representative of real-world scenarios. Furthermore, analyzing the performance of the model against established baselines offers a crucial way of verifying the significance of any improvement achieved. Ideally, the paper should not only report the results of the downstream tasks but also provide detailed analysis to better understand the model’s behavior and potential areas for future development.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for this research could involve exploring more sophisticated subgraph selection methods, potentially leveraging graph neural networks to identify semantically meaningful substructures rather than relying on simpler heuristics. Incorporating attention mechanisms into the model architecture to focus on the most relevant subgraphs during diffusion would improve efficiency and performance. Furthermore, investigating alternative noise injection strategies beyond Gaussian noise, such as using more complex distributions tailored to molecular properties, could significantly impact results. Extending SubgDiff to handle larger molecules and more complex chemical systems is crucial for practical applications. Finally, thorough benchmarking against a wider range of datasets and tasks, and rigorous analysis of model interpretability, would further solidify the findings and demonstrate the generalizability of SubgDiff.

More visual insights#

More on figures

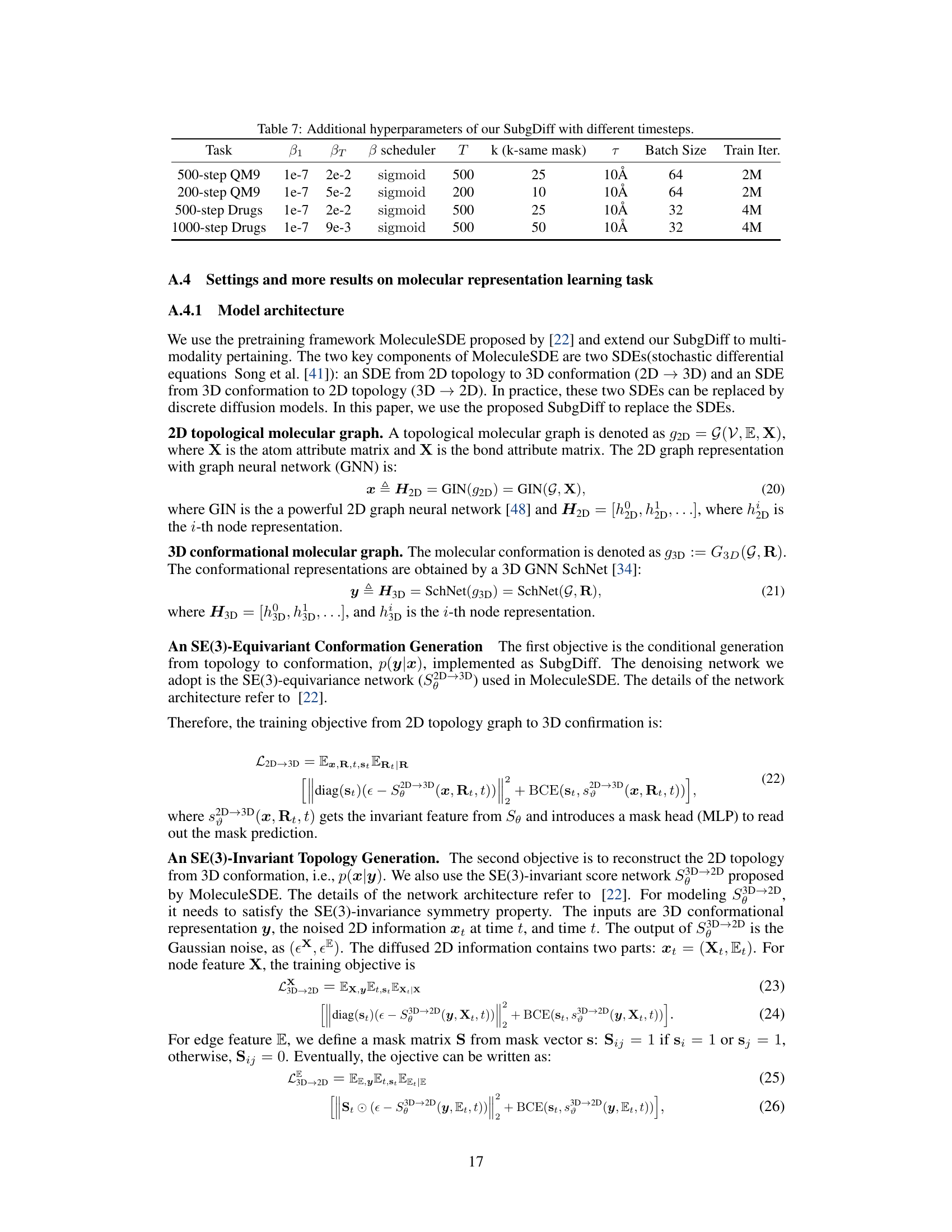

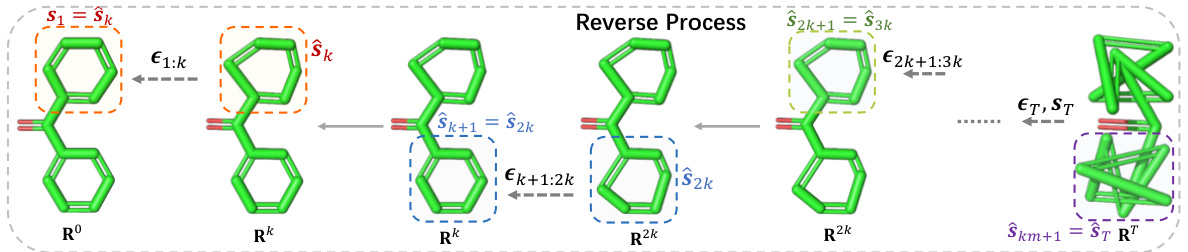

This figure compares the forward diffusion processes of two models: DDPM and SubgDiff. DDPM adds Gaussian noise to all atomic coordinates of a 3D molecule at each diffusion step. In contrast, SubgDiff only adds noise to a randomly selected subgraph at each step. This highlights SubgDiff’s key innovation of incorporating substructural information into the diffusion process by selectively applying noise to subgraphs, rather than treating each atom independently.

This figure illustrates the Markov chain used in the SubgDiff model. It shows how the model transitions between states, indicating the conditional probability of moving from state Rt-1 to Rt. The transition depends on the value of the mask vector st. If st = 0, the model remains in the same state (lazy transition); otherwise, if st = 1, it transitions to state Rt. This representation emphasizes the model’s ability to incorporate substructural information by selectively introducing noise only to certain atoms or subgraphs of the molecule.

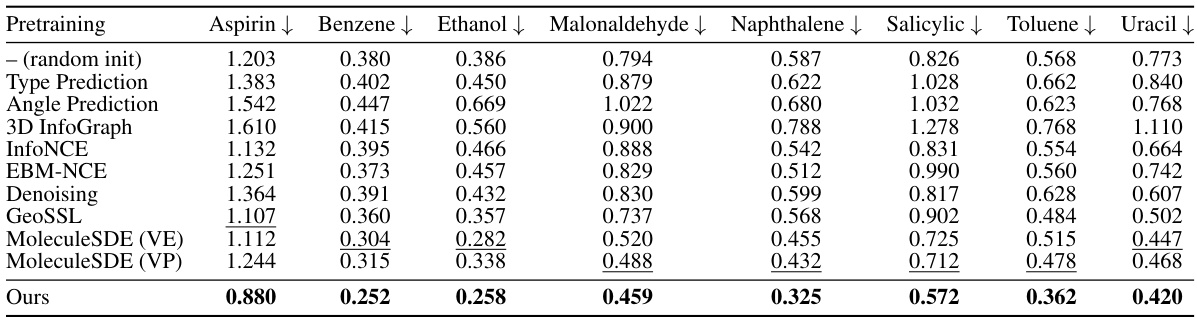

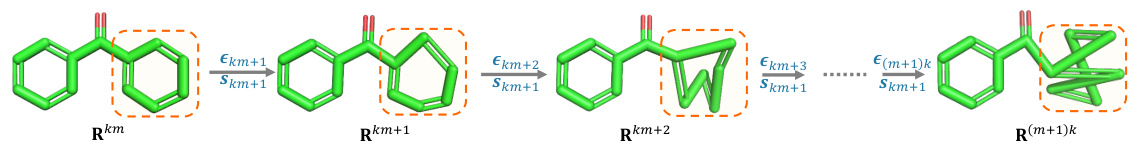

The figure illustrates the forward diffusion process of the SubgDiff model. It is divided into two phases: expectation state diffusion and (t-km)-step same-subgraph diffusion. In the first phase (steps 0 to km), the expectation of the atomic coordinates is used, and the mask variables are kept constant within intervals of length k. In the second phase (steps km+1 to t), the same subgraph is selected for diffusion, indicating a k-step same-subgraph diffusion. The figure visually represents the process with 3D molecular structures at various stages, showcasing how noise is added and subgraphs are processed.

This figure illustrates the forward diffusion process of the SubgDiff model. It highlights two phases: the expectation state diffusion (from state 0 to km) and the k-step same-subgraph diffusion (from km+1 to t). In the expectation state phase, the model leverages the mean of the atom coordinates (expectation state) instead of the actual coordinates to add noise, making it less sensitive to the specific subgraph selected. The second phase employs the k-step same-subgraph diffusion, applying noise to the same randomly selected subgraph for k consecutive steps, enhancing the model’s ability to learn substructure features. The overall process allows SubgDiff to effectively capture substructural information within the molecule during training.

This figure compares the forward diffusion processes of two different models: DDPM and SubgDiff. DDPM adds Gaussian noise to all atomic coordinates of a 3D molecule at each step of the diffusion process. In contrast, SubgDiff only adds noise to a randomly selected subset of atoms (a subgraph) at each step. This highlights the key difference between the two methods: SubgDiff incorporates substructural information by selectively diffusing subsets of atoms, whereas DDPM treats each atom independently.

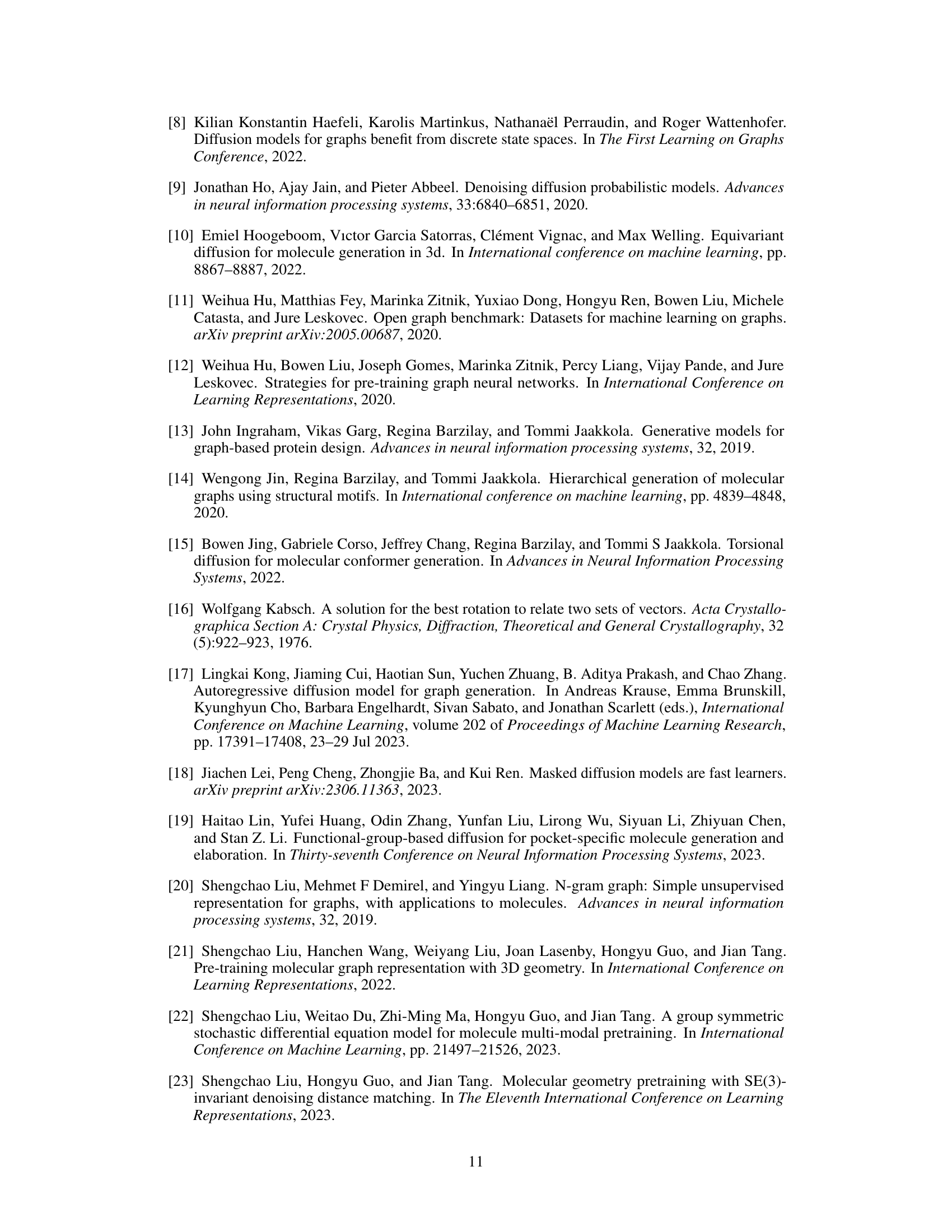

This figure visualizes the results of a t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) dimensionality reduction technique applied to molecule representations learned by the model. Each point represents a molecule, and the color of the point indicates the scaffold (core structure) of that molecule. The visualization aims to show whether molecules with the same scaffold cluster together in the representation space. Close clustering suggests that the model has learned to effectively capture scaffold information as a key feature for representing molecules.

The figure illustrates the architecture of the SubgDiff model used for denoising. It shows the process of adding noise to 3D molecular structures, the encoding of the noisy structures using a GNN encoder, and the prediction of both the mask (selecting subgraphs) and the noise using separate mask and noise heads. The objective function involves both a binary cross-entropy loss for mask prediction (L1) and a mean squared error loss for noise prediction (L2).

This figure illustrates the forward diffusion process of the SubgDiff model. It shows how the model incorporates subgraph information by using expectation states for a portion of the process and then applying k-step same-subgraph diffusion for another portion. The different stages highlight how noise is added and how subgraphs are chosen and consistently diffused for a fixed number of steps. The orange dashed boxes represent the subgraph that is selected at each step.

More on tables

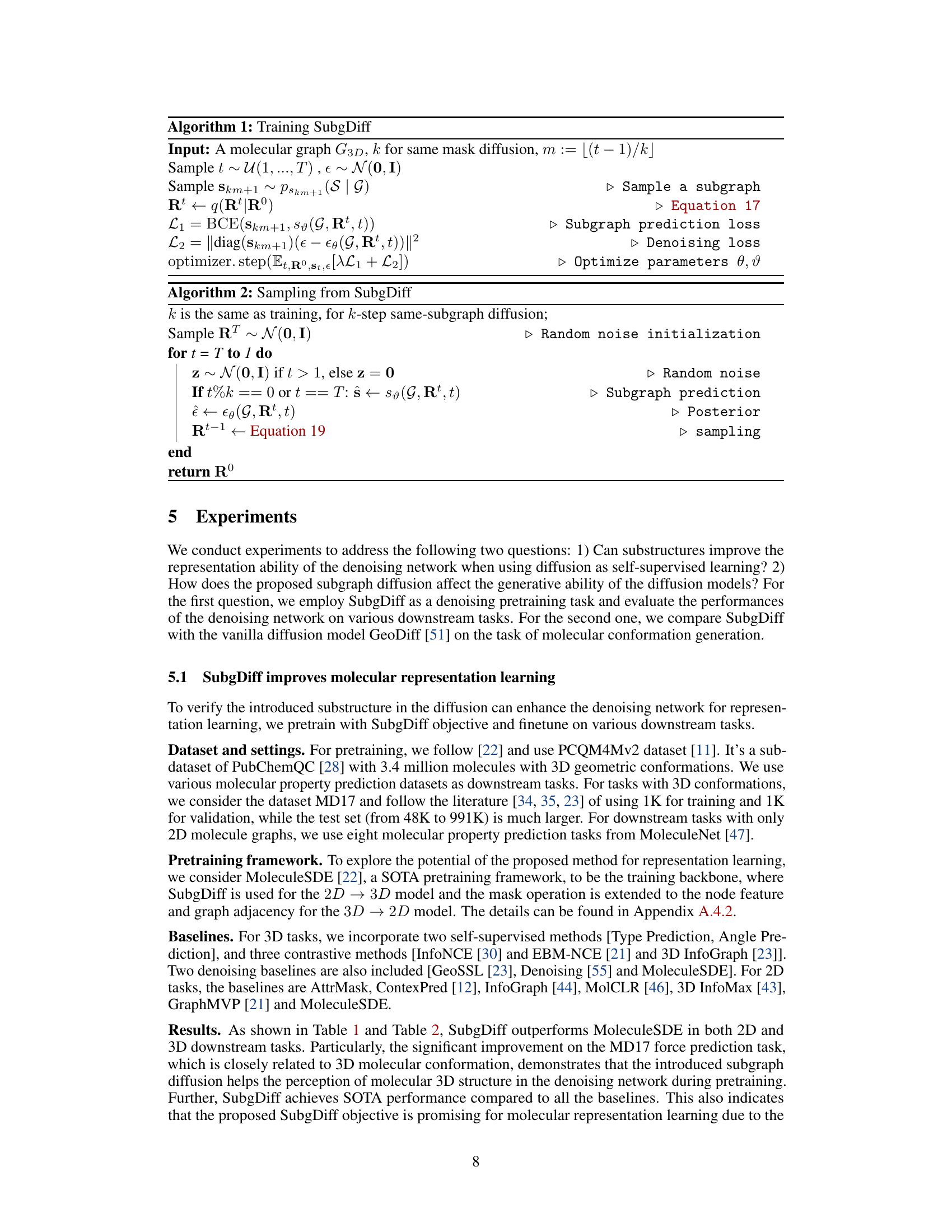

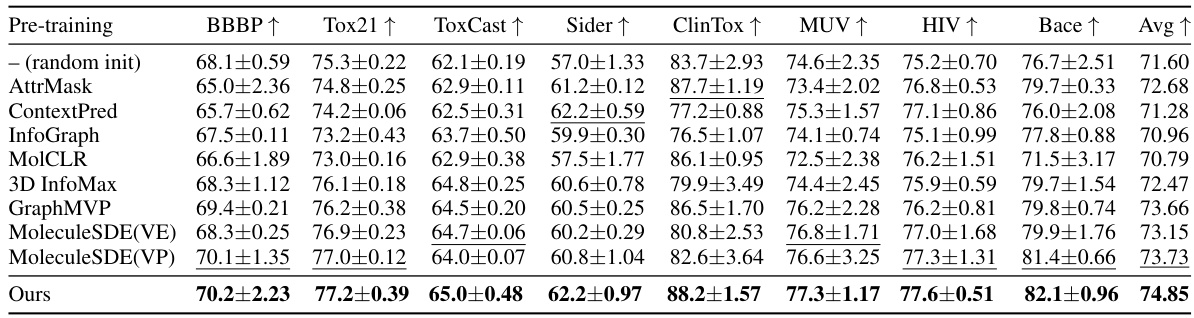

This table presents the results of applying different pre-training methods on eight molecular property prediction tasks from the MoleculeNet dataset. Only the 2D topological information of the molecules was used. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for three different random seeds, using scaffold splitting for data division. The backbone graph neural network used was GIN. The best and second-best performing methods are highlighted.

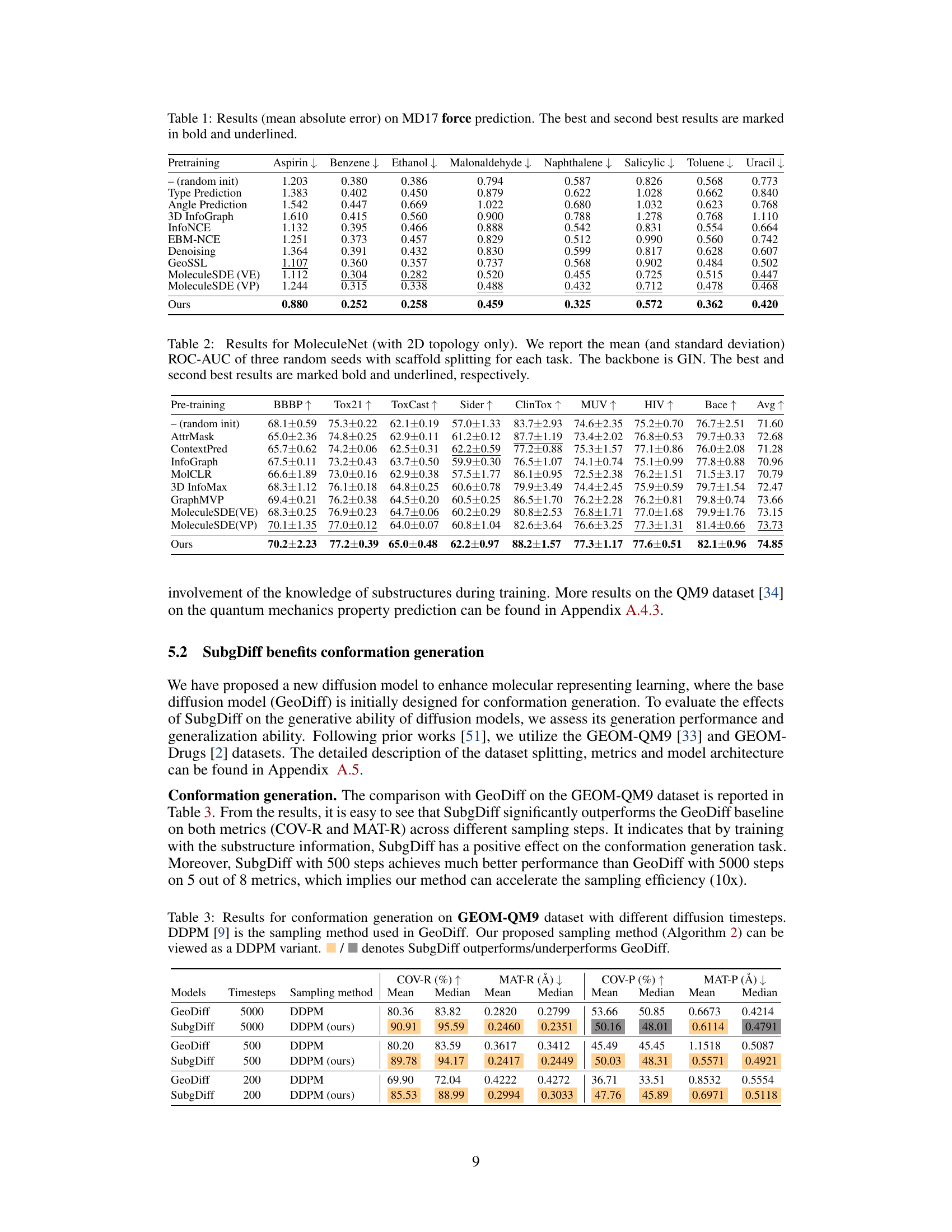

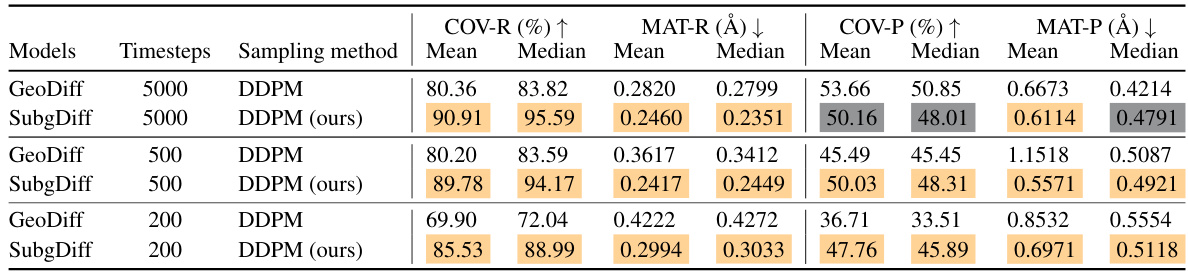

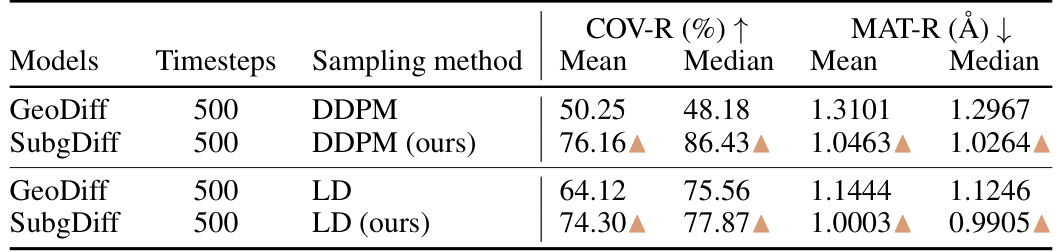

This table presents the results of conformation generation experiments conducted on the GEOM-QM9 dataset using different diffusion models and sampling methods. It compares GeoDiff (using DDPM) and SubgDiff (using a modified DDPM) across various numbers of diffusion steps (5000, 500, and 200). The performance is evaluated using four metrics: COV-R, MAT-R, COV-P, and MAT-P, which measure the quality and accuracy of the generated molecular conformations. The results show that SubgDiff generally outperforms GeoDiff, especially with fewer diffusion steps, suggesting improved efficiency and better generation quality.

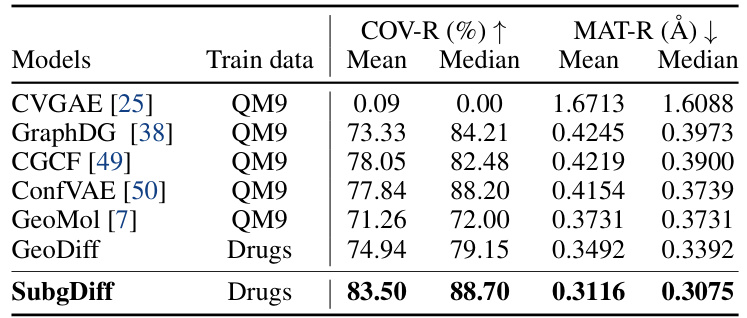

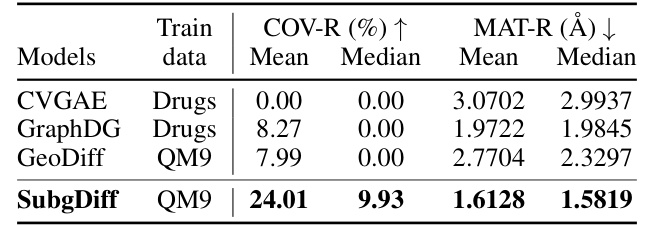

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments conducted on the GEOM-QM9 dataset. The models were either trained on the QM9 dataset (small molecules) and tested on the GEOM-Drugs dataset (larger molecules), or vice versa. The table compares the performance of SubgDiff to several baselines (CVGAE, GraphDG, CGCF, ConfVAE, GeoMol, and GeoDiff) across two metrics: COV-R (coverage recall) and MAT-R (matching root mean square deviation). The results highlight SubgDiff’s superior performance on domain generalization tasks, demonstrating its robustness and generalizability.

This table presents the Silhouette index, a metric used to measure the quality of clustering, for molecule embeddings generated using MoleculeSDE and the proposed SubgDiff method. Higher Silhouette index indicates better clustering quality and better representation learning of molecular structures. The results are shown for five different datasets from the MoleculeNet dataset.

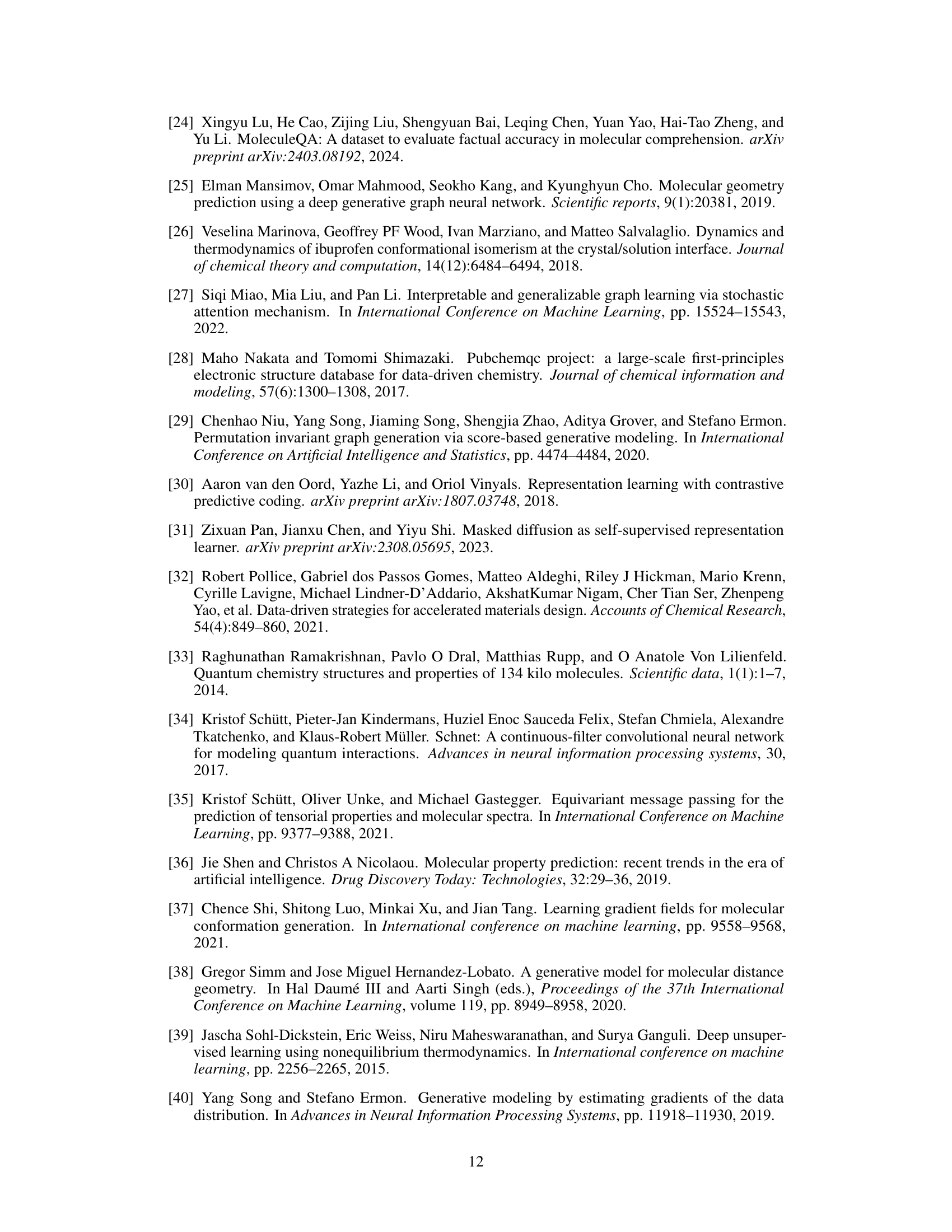

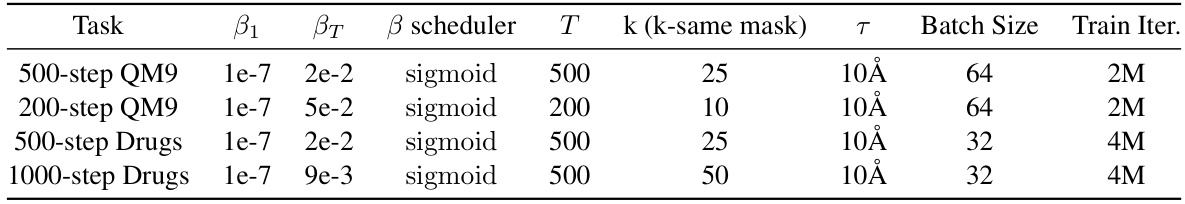

This table presents the hyperparameters used in the SubgDiff model for the QM9 and Drugs datasets. It shows the starting and ending values for the variance schedule (β1, βT), the type of variance scheduler used (‘sigmoid’), the total number of diffusion steps (T), the number of k-step same subgraph diffusion steps (k), the radius of the neighborhood considered for the interactions (τ), the batch size used during training, and the total number of training iterations.

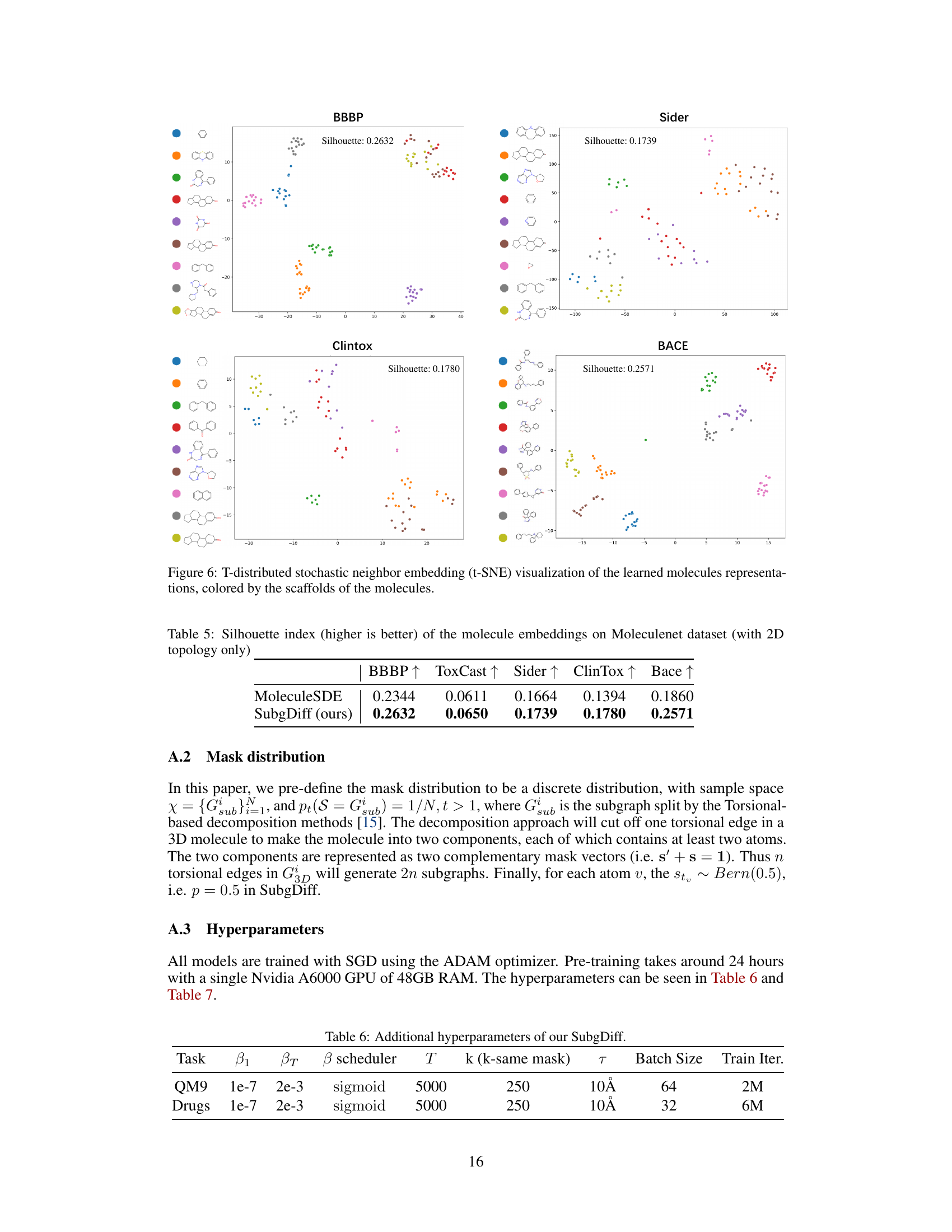

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training SubgDiff with different numbers of diffusion steps. It shows the starting and ending values of the variance schedule (β_1, β_T), the type of variance scheduler used, the total number of diffusion steps (T), the number of steps for k-step same subgraph diffusion (k), the temperature (τ), batch size, and the number of training iterations for QM9 and Drugs datasets.

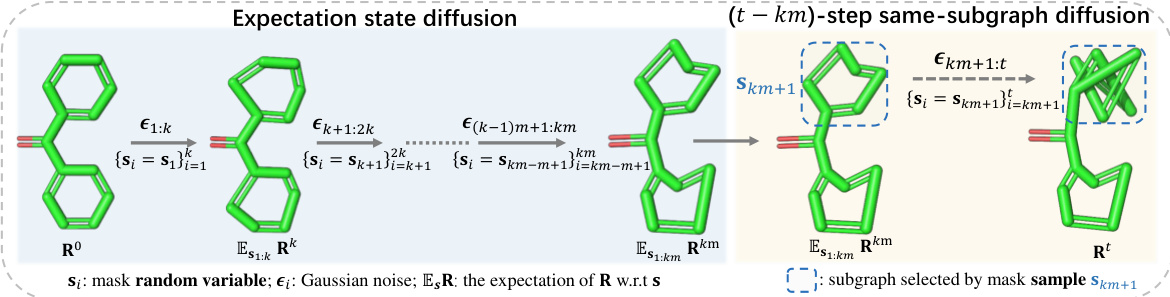

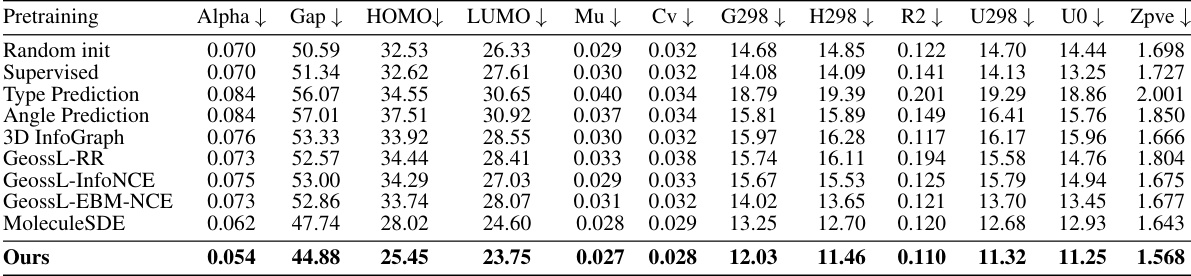

This table presents the results of 12 quantum mechanics prediction tasks using the QM9 dataset. The model was trained on 110,000 molecules, validated on 10,000, and tested on 11,000. The evaluation metric is Mean Absolute Error (MAE). The best and second-best results for each task are highlighted. The underlying neural network architecture used is SchNet.

This table presents the results of 12 quantum mechanics prediction tasks from the QM9 dataset. The model was trained on 110,000 molecules, validated on 10,000, and tested on 11,000. The evaluation metric used is mean absolute error (MAE). The best and second-best results for each task are highlighted. The SchNet architecture was used as the backbone for the model.

This table presents the results of the mean absolute error in predicting molecular forces on the MD17 dataset. It compares the performance of SubgDiff against various baselines (including Type Prediction, Angle Prediction, 3D InfoGraph, InfoNCE, EBM-NCE, Denoising, GeoSSL, and MoleculeSDE). The best-performing method for each molecule is highlighted in bold, with the second-best underlined. This allows a direct comparison of SubgDiff’s performance on a variety of molecular structures against established techniques in force prediction.

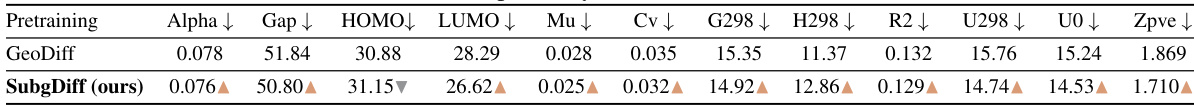

This table compares the performance of GeoDiff and SubgDiff on the GEOM-Drugs dataset using two different sampling methods (DDPM and Langevin dynamics) with different diffusion timesteps (500). The results show the mean and median values of COV-R (%) and MAT-R (Å). The arrows indicate whether SubgDiff outperformed or underperformed GeoDiff.

This table presents the results of conformation generation experiments using the GEOM-QM9 dataset. It compares the performance of SubgDiff, the proposed method, against GeoDiff, a baseline method, across various metrics (COV-R, MAT-R, COV-P, MAT-P). The table also shows the effects of varying the number of diffusion timesteps (500 and 5000). The results demonstrate SubgDiff’s superior performance and efficiency in conformation generation.

This table presents the results of a domain generalization experiment using the GEOM-QM9 dataset. The goal was to evaluate how well different models generalize to out-of-domain data. The models were trained either on the QM9 dataset (small molecules) or the Drugs dataset (larger molecules), and then tested on the opposite dataset. The table shows that SubgDiff significantly outperforms other models, demonstrating its ability to generalize well across different molecular sizes and properties. This highlights SubgDiff’s robustness and effectiveness in molecular representation learning.

This table presents the mean absolute error for force prediction on the MD17 dataset. The model’s performance is evaluated on eight different molecules (Aspirin, Benzene, Ethanol, Malonaldehyde, Naphthalene, Salicylic, Toluene, and Uracil). For each molecule, the mean absolute error is shown, along with a comparison of the performance of several different pre-training methods (random initialization, Type Prediction, Angle Prediction, 3D InfoGraph, InfoNCE, EBM-NCE, Denoising, GeoSSL, MoleculeSDE (VE), MoleculeSDE (VP)) and the proposed SubgDiff model. The best and second-best results for each molecule are highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively, illustrating the superior performance of the SubgDiff model.

Full paper#