↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The rapid increase in satellite data surpasses current transmission capabilities, demanding efficient onboard compression. Existing learned compression methods are too complex for resource-constrained satellite hardware. This creates a need for lightweight solutions that can achieve high compression ratios without sacrificing image quality.

COSMIC addresses this by using a lightweight encoder on the satellite, followed by a ground-based decoder incorporating a diffusion model for detail compensation. This multi-modal approach utilizes sensor data to enhance reconstruction. The results demonstrate significant improvements in both compression ratios and image quality compared to state-of-the-art baselines, showcasing its effectiveness for practical satellite applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical challenge of compressing satellite imagery for efficient transmission, a bottleneck in the rapidly growing field of Earth observation. The proposed lightweight encoder and diffusion-based decoder offer a practical solution for onboard satellite processing, opening new avenues for real-time data analysis and transmission from space. The multi-modal approach, using sensor data, is also a significant contribution to image compression research.

Visual Insights#

The figure shows an example of a satellite image along with its associated metadata. The metadata includes ground sample distance, coordinates, cloud cover, timestamp, and entropy coding. This illustrates the multimodal nature of satellite data, where the image is accompanied by rich contextual information that can aid in its interpretation and use. This multi-modal data concept is crucial to the COSMIC method, which uses the sensor data as additional input for the diffusion-based compensation model.

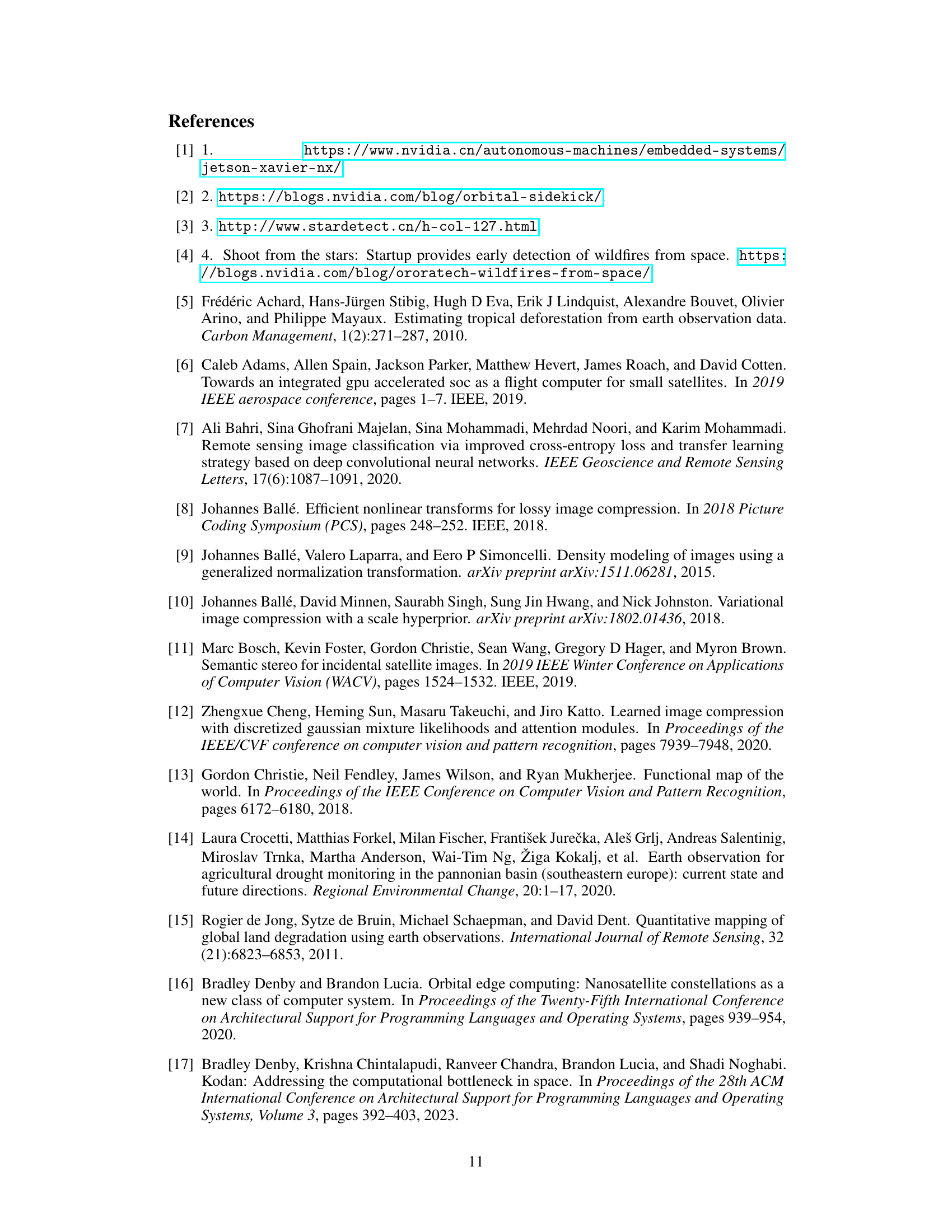

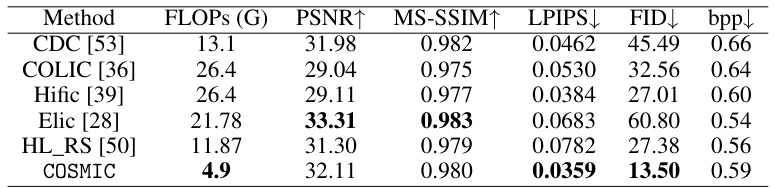

This table compares the computational efficiency (measured in Giga FLOPs) of COSMIC against six state-of-the-art (SOTA) baselines for satellite image compression. It shows the number of FLOPS required by each method’s encoder to process a single image tile, as well as the resulting performance metrics: PSNR, MS-SSIM, LPIPS, FID, and bits per pixel (bpp). The lower the FLOPS value, the more efficient the encoder, allowing for deployment on resource-constrained satellite hardware. COSMIC demonstrates significantly lower FLOPS than the other methods while maintaining competitive performance metrics.

In-depth insights#

Lightweight Encoders#

The concept of ‘Lightweight Encoders’ in the context of satellite image compression is crucial for efficient onboard processing. Resource constraints on satellites necessitate encoders with minimal computational complexity and power consumption. Therefore, a lightweight encoder design prioritizes a high compression ratio over intricate feature extraction, accepting some loss in reconstruction quality to achieve significant FLOPs reduction. This trade-off is acceptable given that the limited processing power on satellites makes complex encoders impractical. The strategy often involves using simpler architectures like depthwise separable convolutions or streamlined attention mechanisms. Post-processing on the ground, with more powerful computational resources, can compensate for the loss in image detail incurred by the lightweight encoding phase, possibly through techniques like diffusion models. This approach successfully balances the need for efficient onboard compression with the desire for high-quality reconstruction at the receiving end.

Diffusion-Based Decoding#

Diffusion-based decoding offers a novel approach to image reconstruction in compression systems, particularly beneficial when dealing with lightweight encoders. By framing the decoding process as a denoising task, where a diffusion model gradually refines a noisy latent representation into a sharp image, it can effectively compensate for information loss incurred during encoding. This method is especially useful when computationally constrained environments, such as onboard satellite systems, limit the complexity of the encoder. The multi-modal nature of satellite imagery (coordinates, timestamps, etc.) can be incorporated as conditional information to guide the diffusion process, further enhancing reconstruction accuracy. The approach is advantageous because it leverages the generative power of diffusion models to recover fine details and textures, but requires careful consideration of the tradeoff between computational cost and reconstruction quality. While promising, challenges remain in optimizing the diffusion model for speed and efficiency in resource-limited settings, and in comprehensively evaluating the performance across different image types and compression ratios.

Satellite Image Datasets#

The effective utilization of satellite imagery hinges critically on the availability of robust and comprehensive datasets. Dataset selection must carefully consider factors such as spatial resolution, spectral range, and temporal coverage. These factors directly impact the types of analyses that can be performed. For instance, high-resolution imagery is essential for tasks requiring fine-grained detail, while lower-resolution data may suffice for broader-scale analysis. Similarly, the spectral characteristics of the data dictate the ability to extract specific information, such as vegetation indices or mineral composition. Furthermore, temporal resolution is crucial for monitoring dynamic processes like deforestation or urban sprawl. Therefore, a thoughtful approach to dataset selection involves a deep understanding of the intended application, coupled with an assessment of the dataset’s limitations and potential biases. The availability of labeled datasets is especially important for supervised machine learning applications. The lack of sufficient labeled data is a major bottleneck for many advanced applications. Publicly available datasets, although valuable, often lack the specificity or scale needed for certain projects. Researchers must therefore critically evaluate the suitability of any existing datasets and explore options such as creating custom datasets or using data augmentation techniques when necessary. Finally, data pre-processing and cleaning steps are also vital to ensure the quality and consistency of the data used in any analysis.

Multi-Modal Compensation#

The concept of “Multi-Modal Compensation” in image compression, particularly within the context of satellite imagery, presents a compelling approach to address the limitations of lightweight encoders deployed on resource-constrained satellite platforms. The core idea is to leverage the inherent multi-modality of satellite data, going beyond the visual image itself. Information such as coordinates, timestamps, sensor specifications, and atmospheric conditions, provides rich contextual information about the image. By integrating this metadata into a compensation model, specifically a diffusion model, the system can recover details and overcome the loss of information caused by using a less complex encoder. This is a significant advancement over traditional approaches that rely solely on the visual data for reconstruction. The diffusion model, conditioned on the metadata, acts as a powerful generative model, filling in the gaps left by the simplified encoder. The effectiveness lies in the synergy between the lightweight, efficient encoding on the satellite and the computationally intensive, high-quality compensation done on ground-based resources. This division of labor addresses the practical constraints of spaceborne processing and enables achieving superior compression ratios and reconstruction quality. However, the success hinges on effectively designing the metadata encoding scheme and training the conditional diffusion model to accurately synthesize missing visual detail from diverse sensor inputs. The strength of this strategy lies in its flexibility and potential to scale with increasing satellite data volumes, making it particularly relevant in the era of large-scale satellite constellations.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could focus on enhancing the lightweight encoder’s feature extraction capabilities. Improving the encoder could reduce reliance on the diffusion model for detail compensation, particularly at very low bitrates. Exploring alternative compensation methods beyond diffusion, perhaps leveraging other generative models or techniques better suited to the specific characteristics of satellite imagery, is warranted. Investigating the impact of different sensor data modalities and their optimal incorporation into the compensation model is crucial for maximizing reconstruction quality. Further research should also evaluate the robustness and generalization capabilities of COSMIC across diverse satellite platforms and sensor configurations. Finally, developing a unified framework that integrates compression, transmission, and on-board processing would significantly advance the field of satellite image management. This could involve optimizing for specific satellite hardware constraints and developing novel methods for handling both lossy and lossless compression scenarios in a unified approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

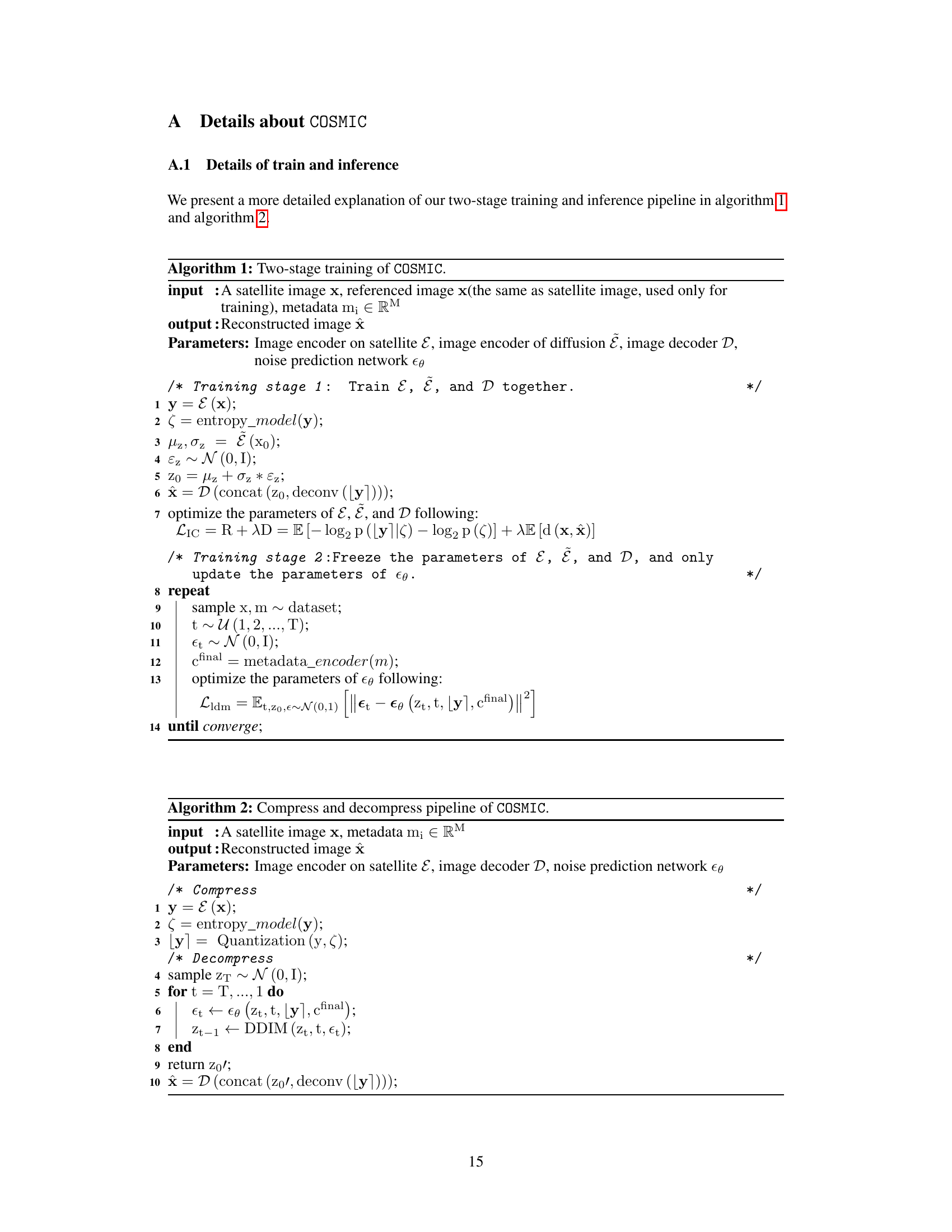

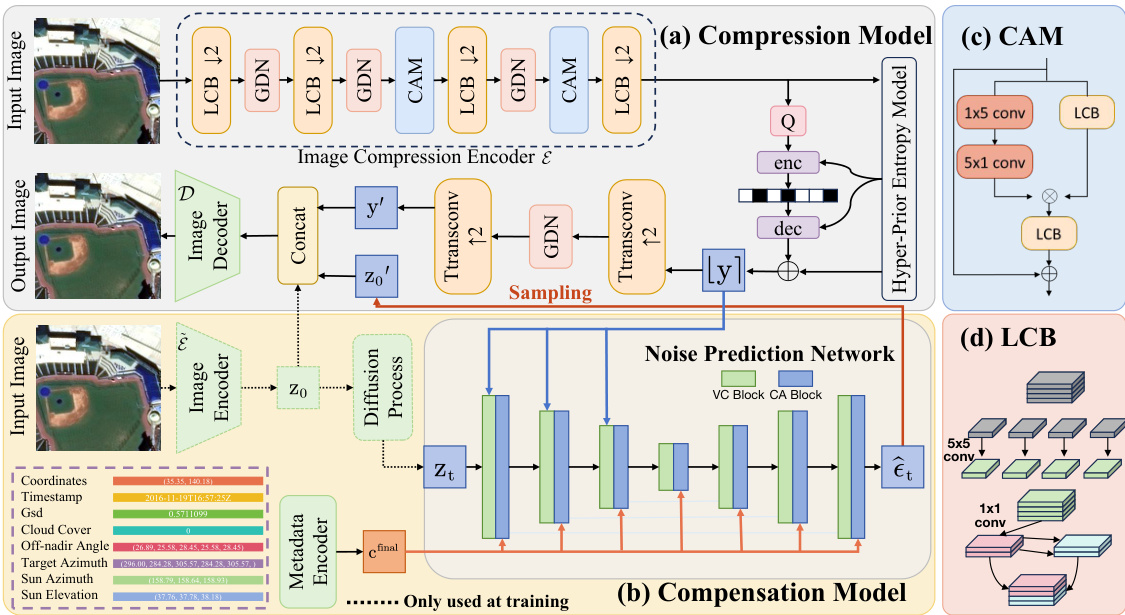

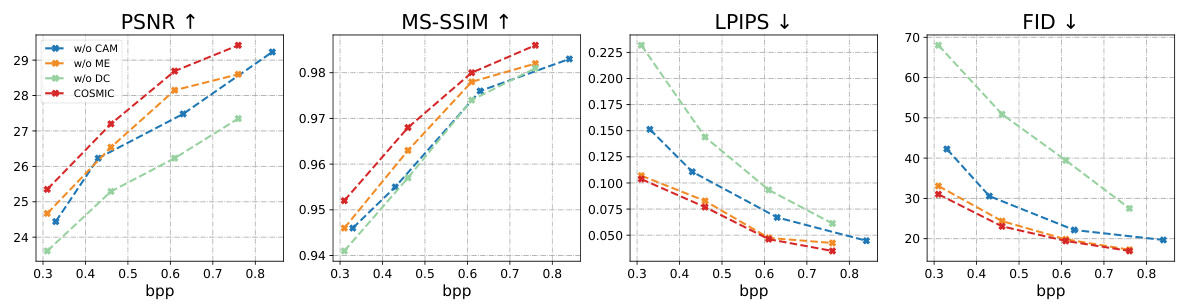

This figure illustrates the architecture of the COSMIC model, which consists of two main modules: a compression module and a compensation module. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder to compress satellite images on-board, saving bandwidth. The compensation module, deployed on the ground, uses a diffusion model to reconstruct image details lost during the compression process, leveraging additional sensor data (metadata) as guidance. The figure details the components of both modules, including the lightweight convolution blocks (LCBs), the convolution attention module (CAM), the metadata encoder (ME), and the noise prediction network.

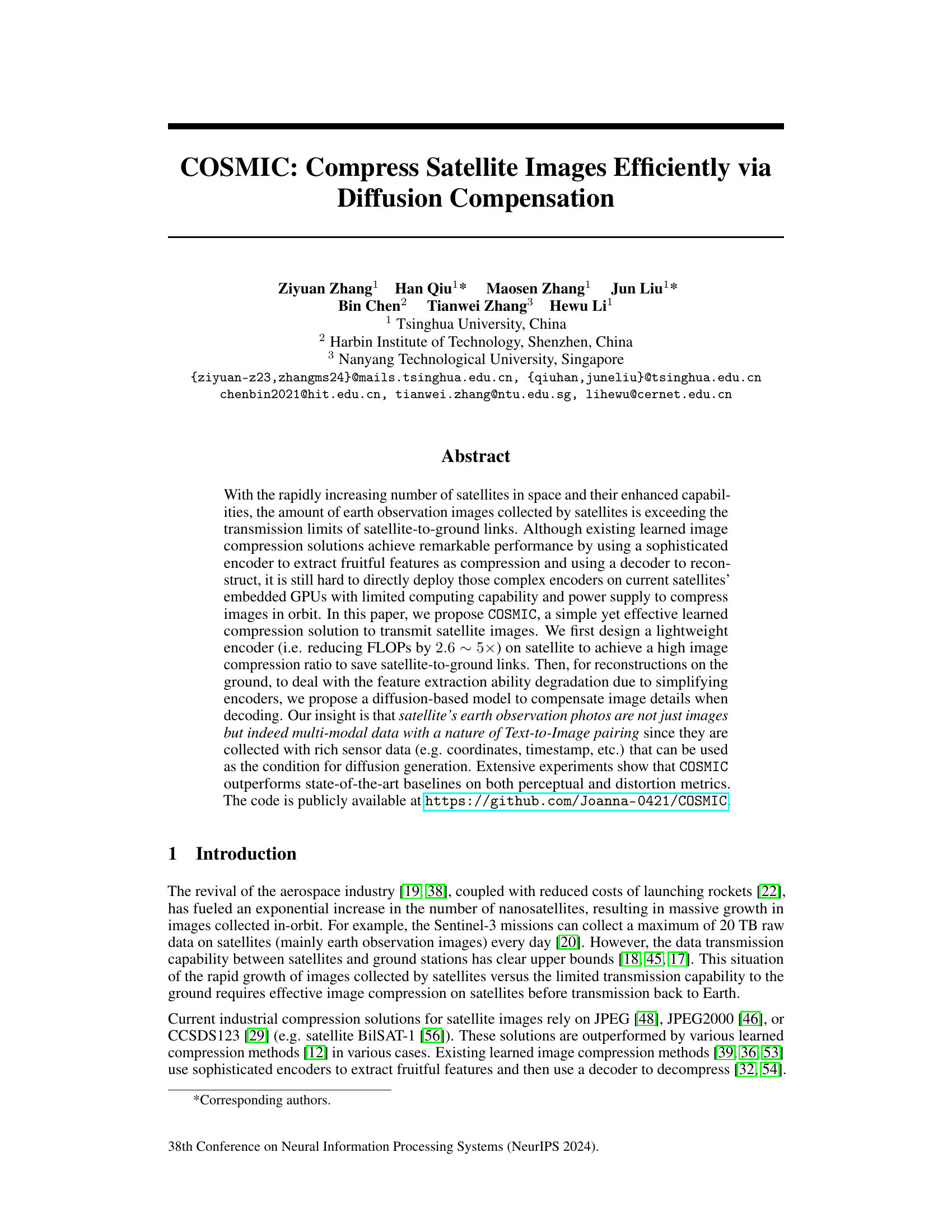

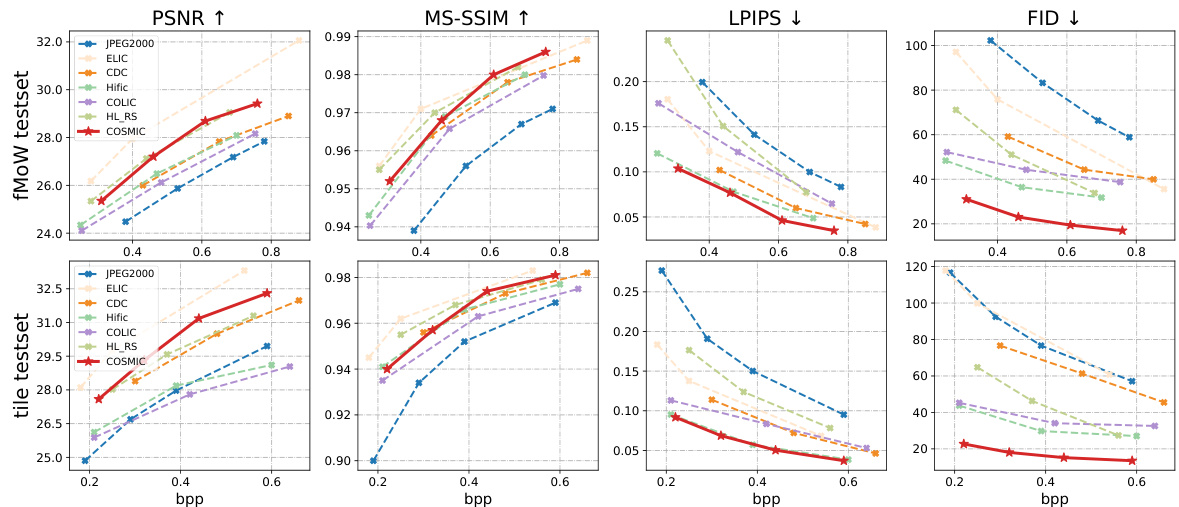

This figure shows the rate-distortion performance of COSMIC compared to six other state-of-the-art image compression methods. It presents four key metrics (PSNR, MS-SSIM, LPIPS, and FID) across a range of bitrates (bpp). Two test sets were used: a standard fMoW test set and a tile test set composed of stitched sub-images. The results demonstrate COSMIC’s superior performance across various metrics and bitrates, especially in perceptual quality (LPIPS and FID). The tile test set highlights COSMIC’s ability to maintain visual consistency even when stitching multiple compressed images.

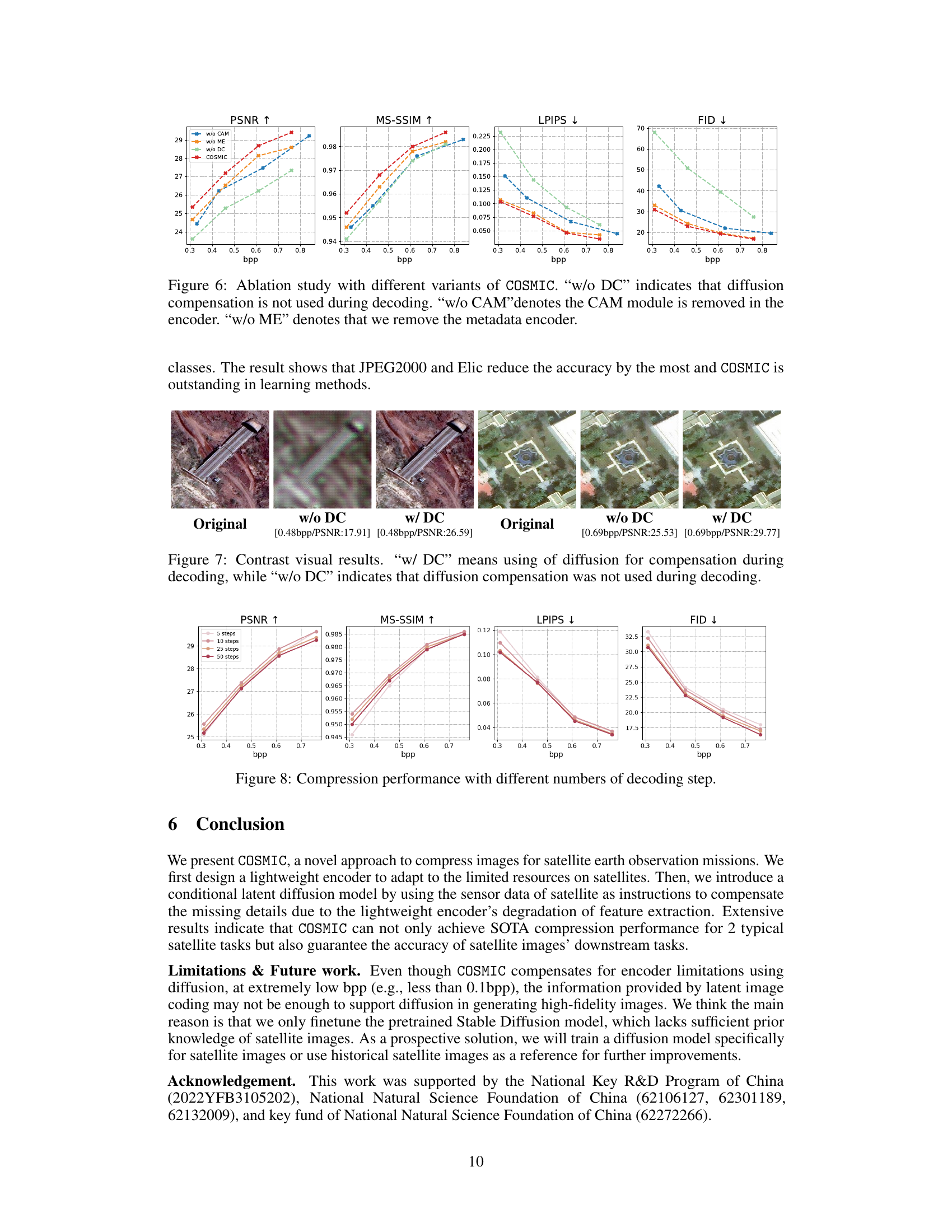

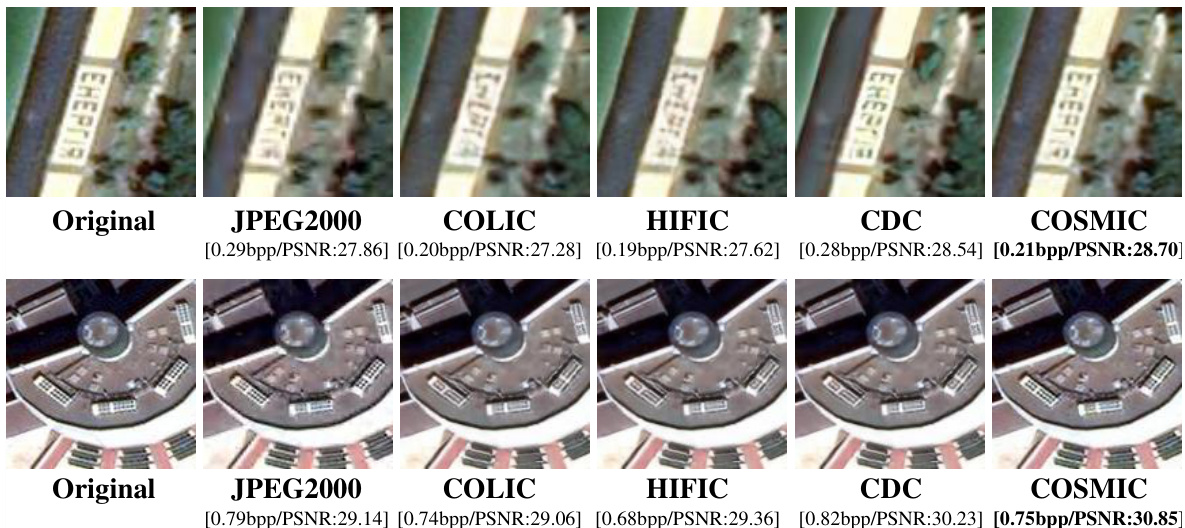

This figure compares the visual quality of images reconstructed by COSMIC and several baseline methods at both low and high bitrates. The top row showcases low-bitrate results where COSMIC demonstrates better visual quality, particularly compared to CDC. The bottom row shows high-bitrate results which further highlight the visual superiority of COSMIC, maintaining good detail preservation even with less information.

This figure illustrates the architecture of COSMIC, a learned image compression solution for satellites. It consists of two main modules: a compression module and a compensation module. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder to compress images on the satellite, while the compensation module leverages a diffusion model to reconstruct the image details on the ground, compensating for the limitations of the lightweight encoder. The figure details the components of each module, highlighting the use of lightweight convolution blocks (LCB), cross-attention (CA) blocks, and a metadata encoder.

This figure compares the performance of COSMIC against six baseline methods across two test sets: the fMoW test set (images of size 256x256) and a tile test set (stitched images). The comparison considers four metrics: PSNR, MS-SSIM, LPIPS, and FID. The results show COSMIC generally outperforms the baselines, demonstrating a trade-off between compression rate (bpp) and both distortion and perceptual metrics. The tile test set results highlight COSMIC’s ability to maintain consistency in stitching compared to the baselines.

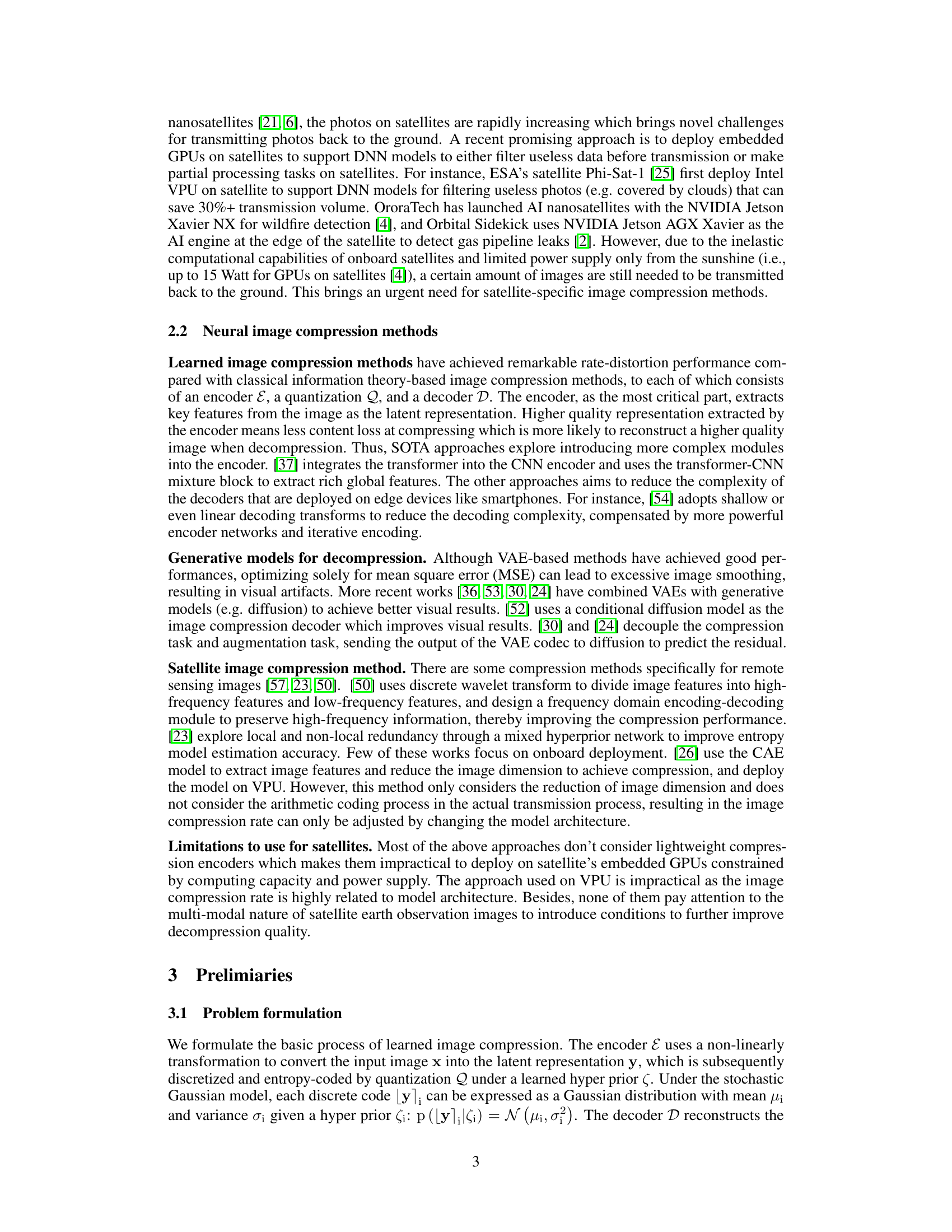

This figure shows a comparison of visual results obtained with and without using diffusion for compensation during the decoding process. The left two images show an example where the lack of diffusion compensation results in a degraded image at 0.48 bits per pixel (bpp), with significant artifacts. The right two images demonstrate an example at 0.69 bpp where the impact of the diffusion compensation is less noticeable. The figure visually emphasizes how the diffusion process improves visual quality by filling in detail lost in the lightweight compression encoding step, especially at lower bitrates.

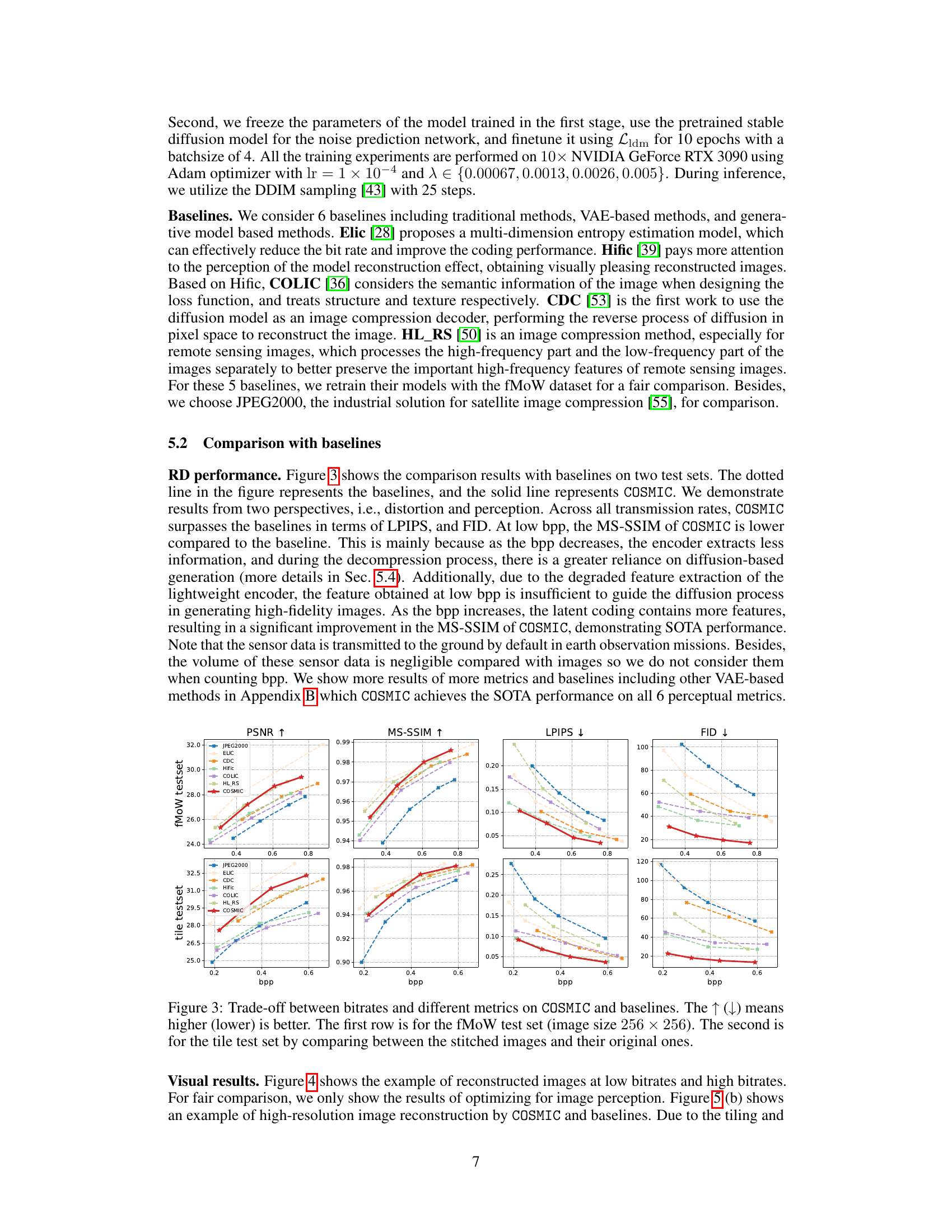

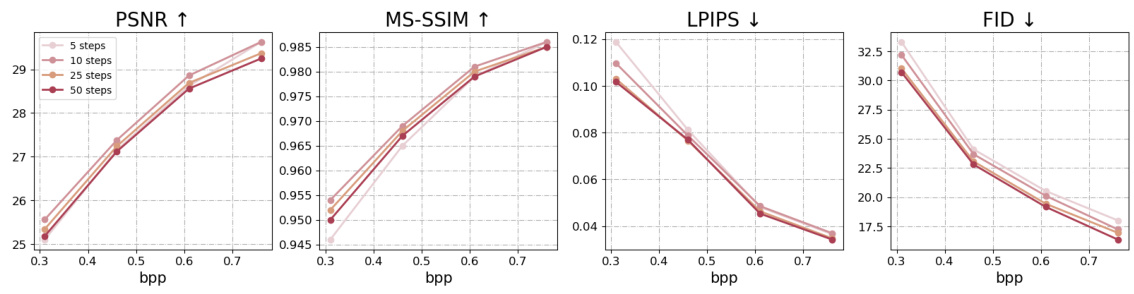

This figure shows the impact of varying the number of decoding steps in the reverse diffusion process on the quality of the reconstructed images. It displays how different metrics (PSNR, MS-SSIM, LPIPS, and FID) change with different bitrates (bpp) when using 5, 10, 25, and 50 decoding steps. The results illustrate the trade-off between perceptual quality and distortion as the number of steps increases.

This figure shows the rate-distortion performance comparison between COSMIC and six state-of-the-art baselines across different metrics, including PSNR, MS-SSIM, LPIPS, and FID. It showcases the performance on two different test sets: the fMoW test set with images of size 256x256 and a tile test set constructed from larger images divided into 256x256 patches. The results demonstrate COSMIC’s superior performance, especially at higher bitrates, on both distortion and perceptual metrics.

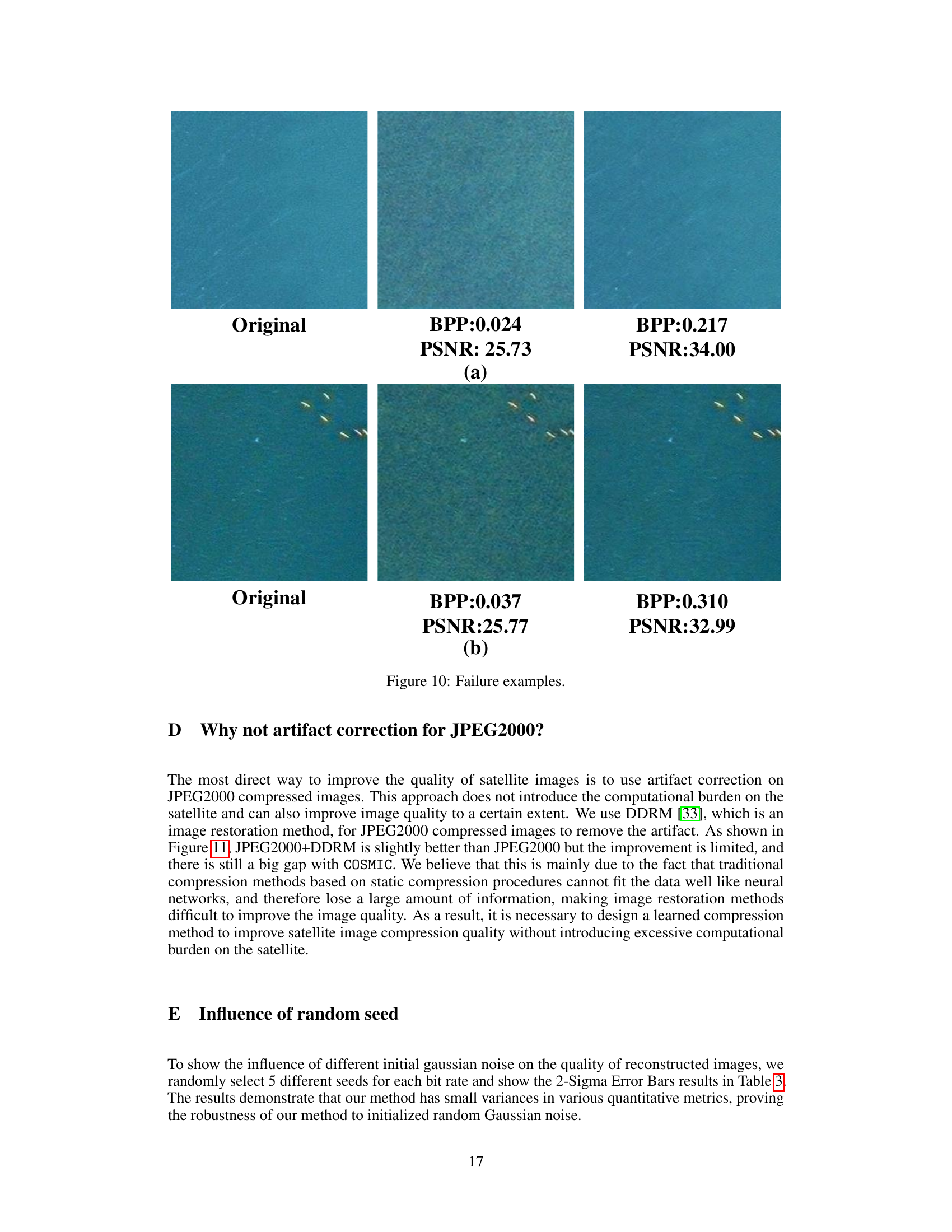

This figure shows some failure cases of COSMIC at low bitrates. The failure cases are mainly due to the insufficient feature extraction ability of the lightweight encoder, and the diffusion model needs to generate many non-existent textures and contents. However, in ROI (region of interest) such as ship detection, COSMIC can still achieve good reconstruction result even in low bitrates.

This figure displays the rate-distortion performance comparison between COSMIC and six baseline methods on two distinct test sets: the fMoW test set (images of size 256x256) and a tile test set (stitched images compared to their original high-resolution counterparts). The results are presented across various bitrates (bpp) for four different metrics: PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), MS-SSIM (Multi-Scale Structural Similarity Index Measure), LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity), and FID (Fréchet Inception Distance). The arrows indicate whether a higher or lower value is preferable for each metric (higher is better for PSNR, MS-SSIM, and CW-SSIM, while lower is better for LPIPS and FID). The figure demonstrates COSMIC’s superior performance across various bitrates.

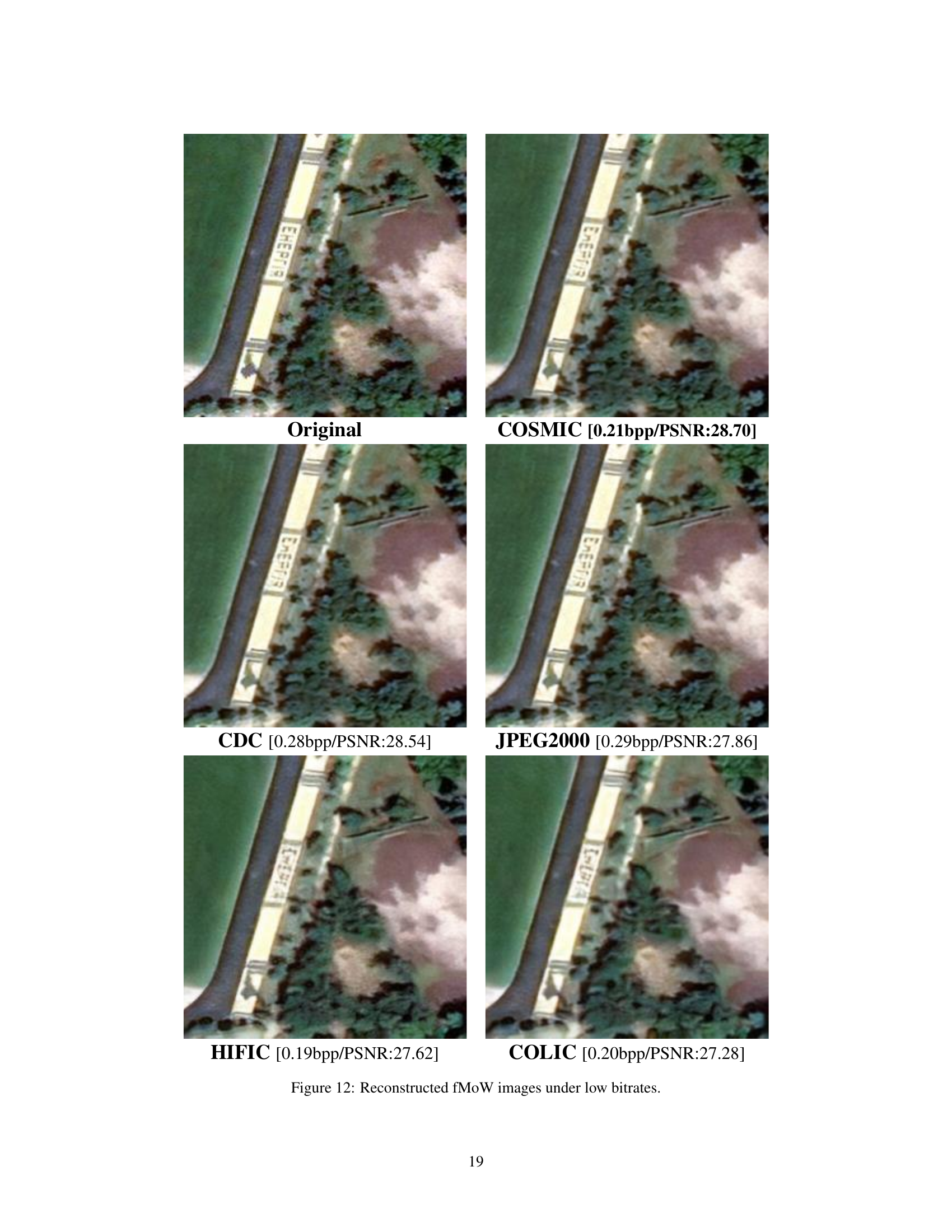

This figure compares the visual quality of reconstructed images from the fMoW dataset at low bitrates (around 0.2 bpp). It shows the original image alongside reconstructions using COSMIC, CDC, JPEG2000, HIFIC, and COLIC. The purpose is to visually demonstrate COSMIC’s performance relative to several state-of-the-art compression methods under conditions of limited bitrate. The visual differences highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each approach in terms of detail preservation and artifact reduction.

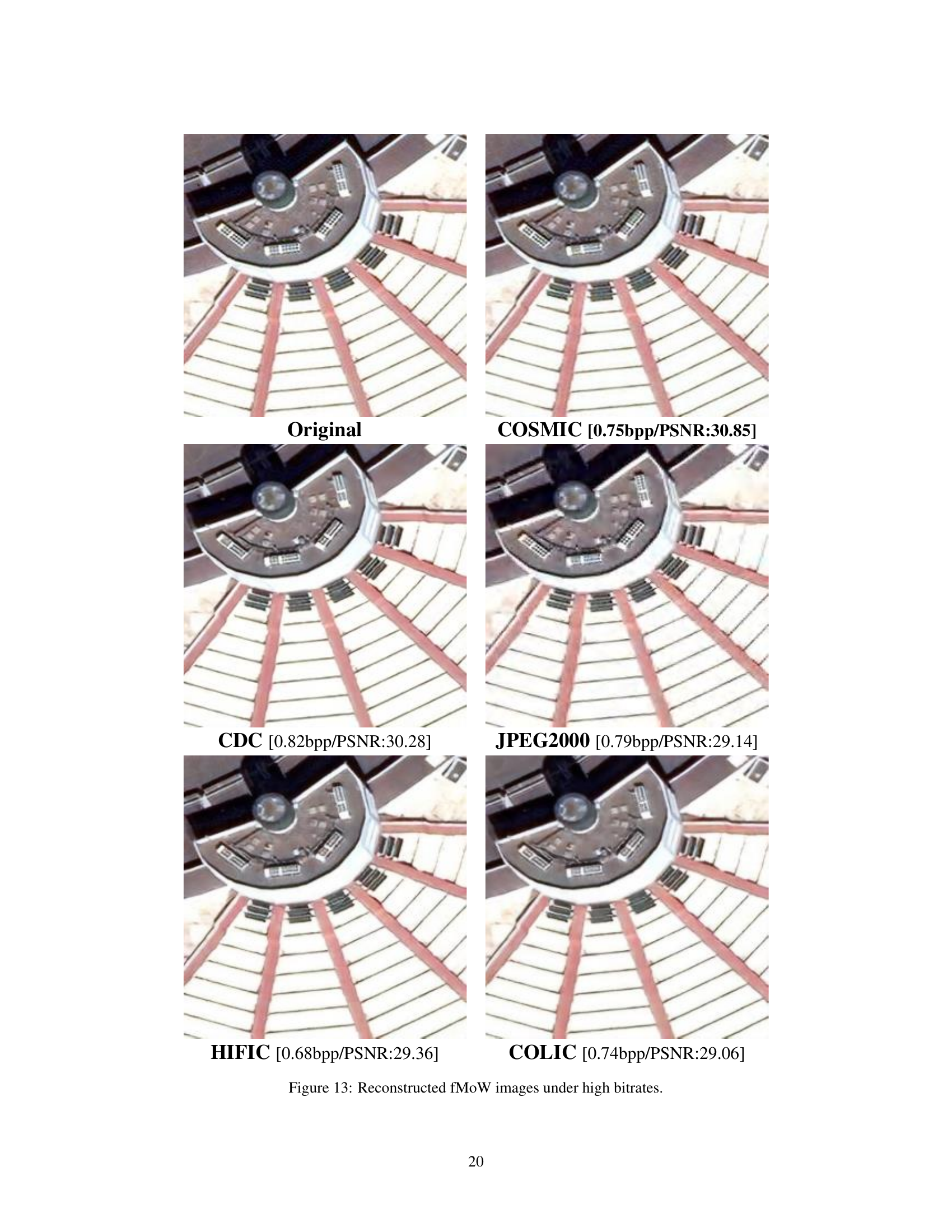

This figure presents a visual comparison of image reconstruction results using different methods (COSMIC, CDC, JPEG2000, HIFIC, COLIC) at high bitrates. The original image is displayed alongside its reconstructed versions by each method, enabling a direct evaluation of visual quality and fidelity. This comparison helps demonstrate the performance of COSMIC in preserving image details and structural integrity in high-bitrate settings, comparing against traditional methods and other state-of-the-art learned image compression techniques.

The figure shows an example of a satellite image along with its associated metadata. The image depicts a coastal area with industrial sites and urban development. The accompanying metadata includes geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude), ground sample distance (GSD), cloud cover percentage, timestamp, and a binary representation of entropy coding. This illustrates the multi-modal nature of satellite data—an image paired with rich sensor information that describes the image’s context (location, time, acquisition parameters, etc.). This multi-modal data is leveraged in the COSMIC method described in the paper.

This figure shows a sample satellite image and its associated metadata. The image depicts a coastal area with a port, industrial facilities, and residential areas. The metadata includes information such as the image’s geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude), ground sample distance (GSD), cloud cover percentage, and timestamp. This illustrates the multimodal nature of satellite data – the image itself plus rich contextual information – which the COSMIC method utilizes.

This figure shows an example of satellite imagery and its associated metadata. The image depicts a coastal area with industrial facilities, residential areas, and a port. The accompanying metadata includes information such as geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude), ground sample distance (GSD), cloud cover percentage, timestamp, and possibly other sensor readings. This illustrates the multi-modal nature of satellite data, where the image itself is complemented by rich contextual information that further enhances understanding and analysis.

This figure shows a sample satellite image with its metadata. The image depicts a coastal area with a port, industrial facilities, and residential areas. The metadata includes geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude), ground sample distance, cloud cover percentage, and timestamp, illustrating the multi-modal nature of satellite data. This multi-modal aspect is key to COSMIC’s approach, using the metadata as conditional information to improve the image reconstruction during decompression. The satellite’s sensor data acts as a description or context for the image, enhancing its reconstruction, especially when using lightweight encoders with limited feature extraction capabilities.

This figure illustrates the architecture of COSMIC, which comprises a compression module and a compensation module. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder on the satellite to compress the images and then a decoder on the ground to decompress them. The compensation module uses a diffusion model on the ground to compensate for the loss of detail caused by the lightweight encoder. The metadata encoder (ME) processes additional sensor data alongside the image for improved image reconstruction.

This figure shows an example of satellite imagery with associated metadata. The image itself is a satellite photo, likely of a coastal area with industrial features. Accompanying the image are various pieces of sensor data including coordinates (latitude and longitude), ground sample distance (GSD), cloud cover percentage, and a timestamp. This metadata provides crucial contextual information supplementing the visual data, emphasizing the multi-modal nature of satellite data which is a key component of the COSMIC method.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the COSMIC model, which consists of two main modules: a compression module and a compensation module. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder to compress the satellite image on the satellite itself, followed by entropy coding. This compressed information is then transmitted to the ground station. To compensate for information loss due to the lightweight encoder, a compensation module is employed at the ground station. This module uses a decoder and a diffusion model, incorporating metadata from the satellite’s sensors, to reconstruct the image with enhanced details.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the COSMIC model, which consists of two main modules: a compression module and a compensation module. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder to compress satellite images on-board, and a decoder on the ground to reconstruct the images. Due to the reduced complexity of the on-board encoder, the compensation module uses a diffusion model to reconstruct details using metadata information from the satellite, improving the fidelity of the reconstructed images. The figure also details the components of the lightweight encoder and the compensation module, including a lightweight convolution block (LCB), a Cross-Attention (CA) block, and a Vanilla Convolution (VC) block.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the COSMIC model, highlighting the compression and compensation modules. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder to reduce computational burden on the satellite and an entropy model. The compensation module uses a diffusion model to compensate for information loss caused by the simplified encoder. Metadata information from the satellite is incorporated using a metadata encoder and cross-attention blocks within the diffusion model. Lightweight convolution blocks (LCBs) are employed to further enhance the efficiency of the encoder.

This figure illustrates the architecture of COSMIC, which consists of two main modules: the compression module and the compensation module. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder to compress the satellite image and an entropy model. The compensation module utilizes a noise prediction network and a decoder to reconstruct the image, compensating for details lost during the compression process using metadata from the satellite’s sensors. The figure also shows the internal structures of the lightweight convolution block (LCB) and convolution attention module (CAM).

This figure shows the architecture of the COSMIC model, which consists of two main components: a compression module and a compensation module. The compression module uses a lightweight encoder to compress satellite images and an entropy model. The compensation module uses a decoder and a diffusion model to compensate for the loss of information during compression. The figure also shows the different components of the noise prediction network, including the cross-attention blocks, the vanilla convolution blocks, and the metadata encoder. The lightweight convolution block is also shown.

This figure illustrates the architecture of COSMIC, which is composed of a compression module and a compensation module. The compression module is designed for satellite scenarios, it includes a lightweight encoder to reduce computation on the satellite and an entropy model, and a decoder deployed on the ground. The compensation module is located on the ground and consists of a metadata encoder, a noise prediction network and a vanilla convolution block. The noise prediction network uses both latent image discrete encoding and metadata embedding to predict noise for each diffusion step.

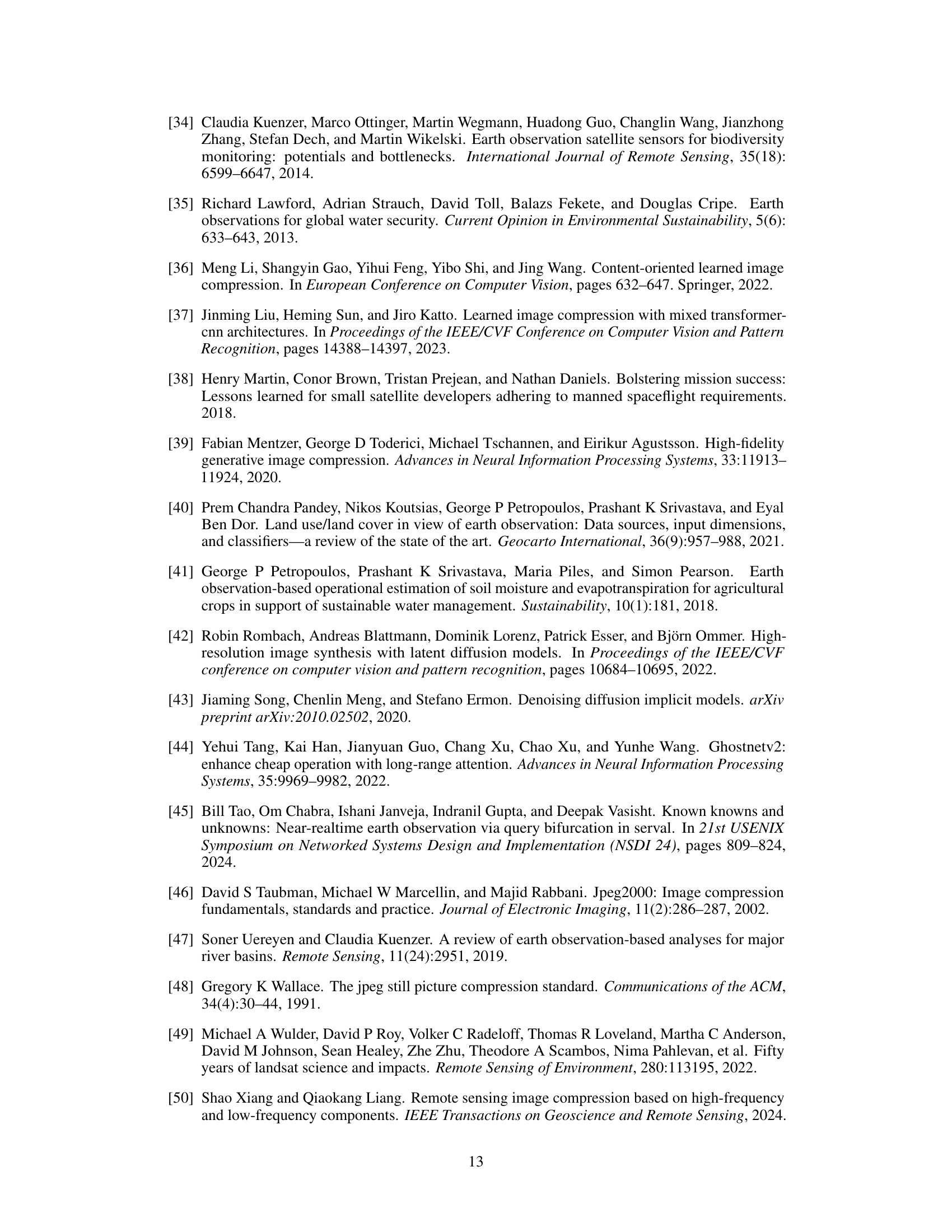

More on tables

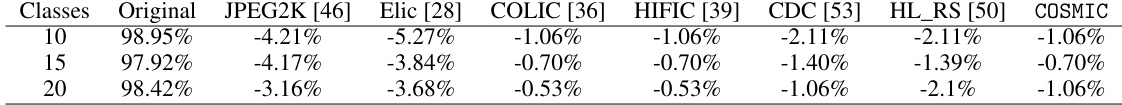

This table presents the impact of different image compression methods on the accuracy of an image classification model. The ‘Original’ column shows the accuracy of the classification model on the uncompressed images. The subsequent columns show the change in classification accuracy (percentage decrease) after compressing the images using various methods. The results are shown for three different numbers of image categories (classes) in the classification model: 10, 15 and 20. A negative percentage indicates a decrease in accuracy.

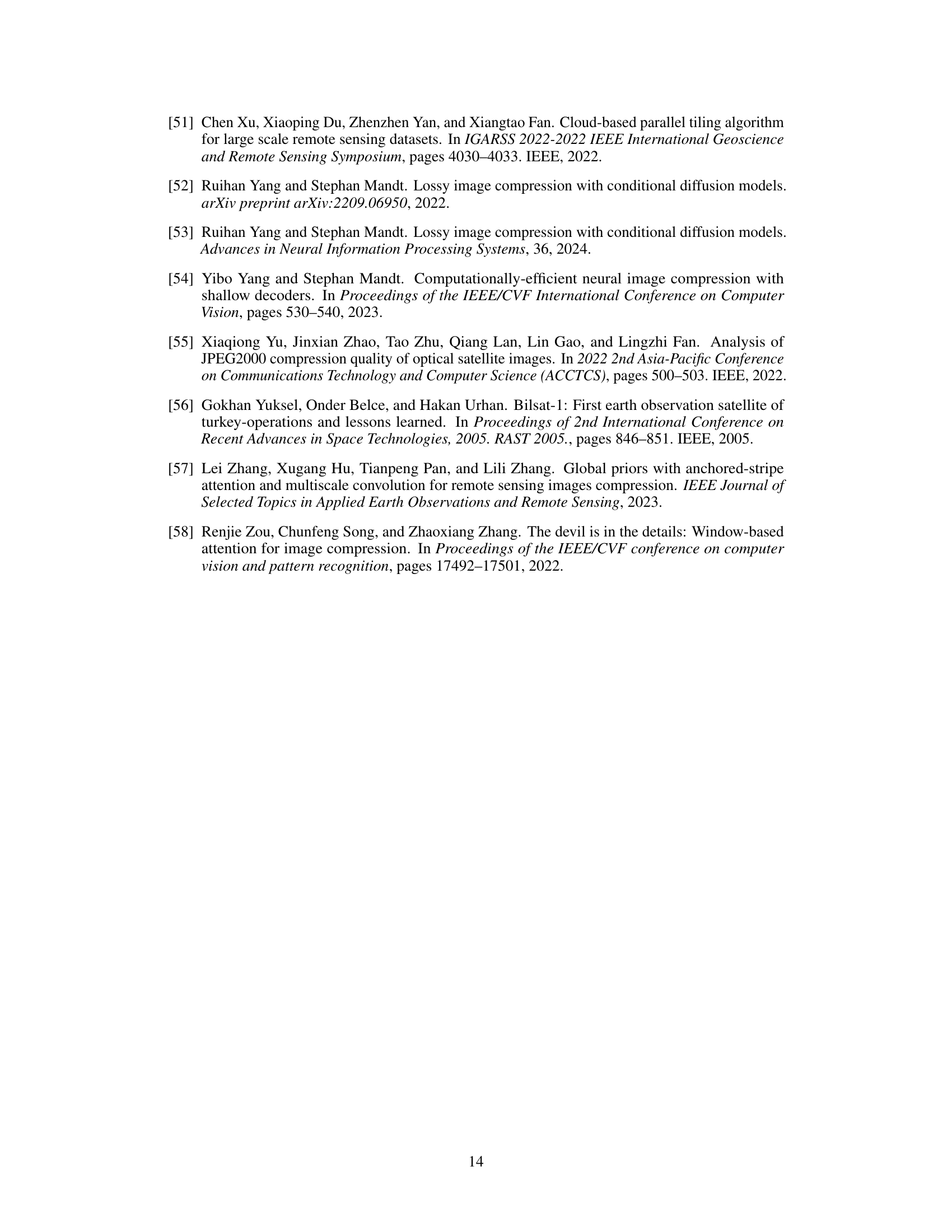

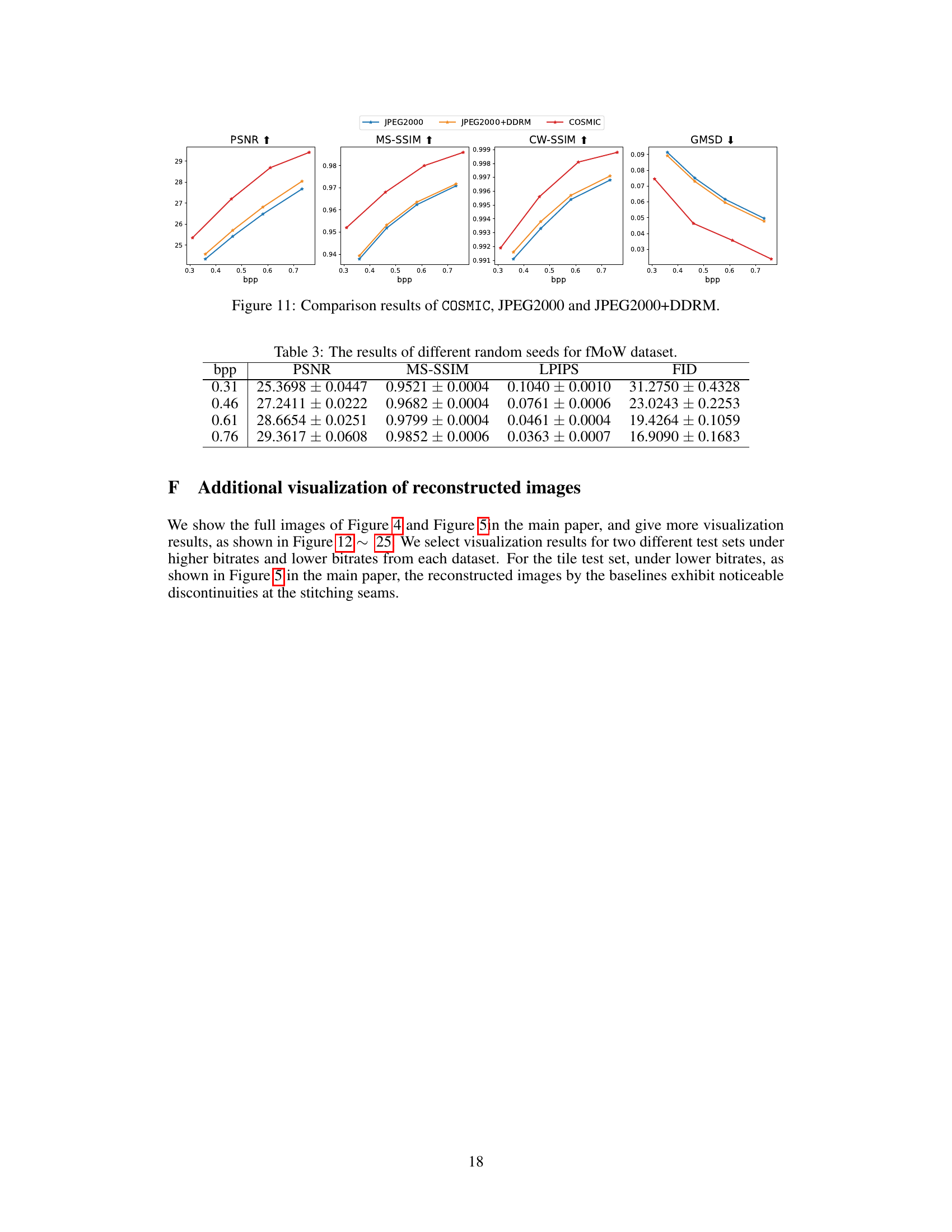

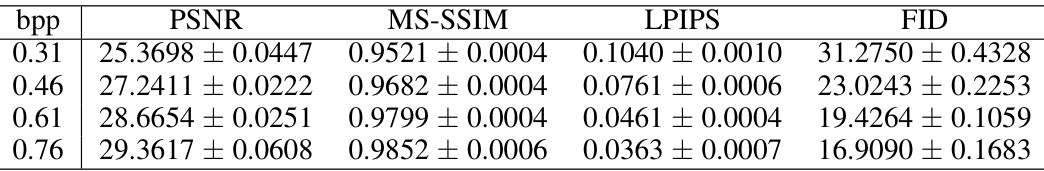

This table presents the results obtained using different random seeds for the fMoW dataset. It shows the mean and standard deviation for PSNR, MS-SSIM, LPIPS, and FID across multiple runs at various bitrates (bpp). The standard deviation provides a measure of the variability or robustness of the results across different trials.

Full paper#