↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems, such as content matching or online labor markets, involve two-sided matching where participants from each side must be matched based on their preferences. However, these preferences are often unknown and need to be learned. Existing online matching algorithms primarily focus on welfare optimization (minimizing regret), overlooking crucial game-theoretic properties like stability. Stable matchings are essential for long-term system reliability, as they prevent participants from seeking secondary markets.

This research introduces novel algorithms that leverage the structure of stable solutions to improve the probability of finding stable matchings. The study initiates a theoretical analysis of the sample complexity needed to find a stable matching and provides corresponding bounds. Furthermore, experiments highlight the interesting interplay between stability and optimality, offering valuable insights for practical algorithm design. These contributions significantly advance the understanding and design of online two-sided matching markets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical gap in online two-sided matching markets by focusing on stability, a crucial game-theoretic property often neglected in prior research. The novel algorithms and theoretical bounds presented offer practical and theoretical advancements, paving the way for more robust and reliable matching systems in various applications. This work also opens avenues for future research in sample complexity analysis and the tradeoffs between stability and optimality.

Visual Insights#

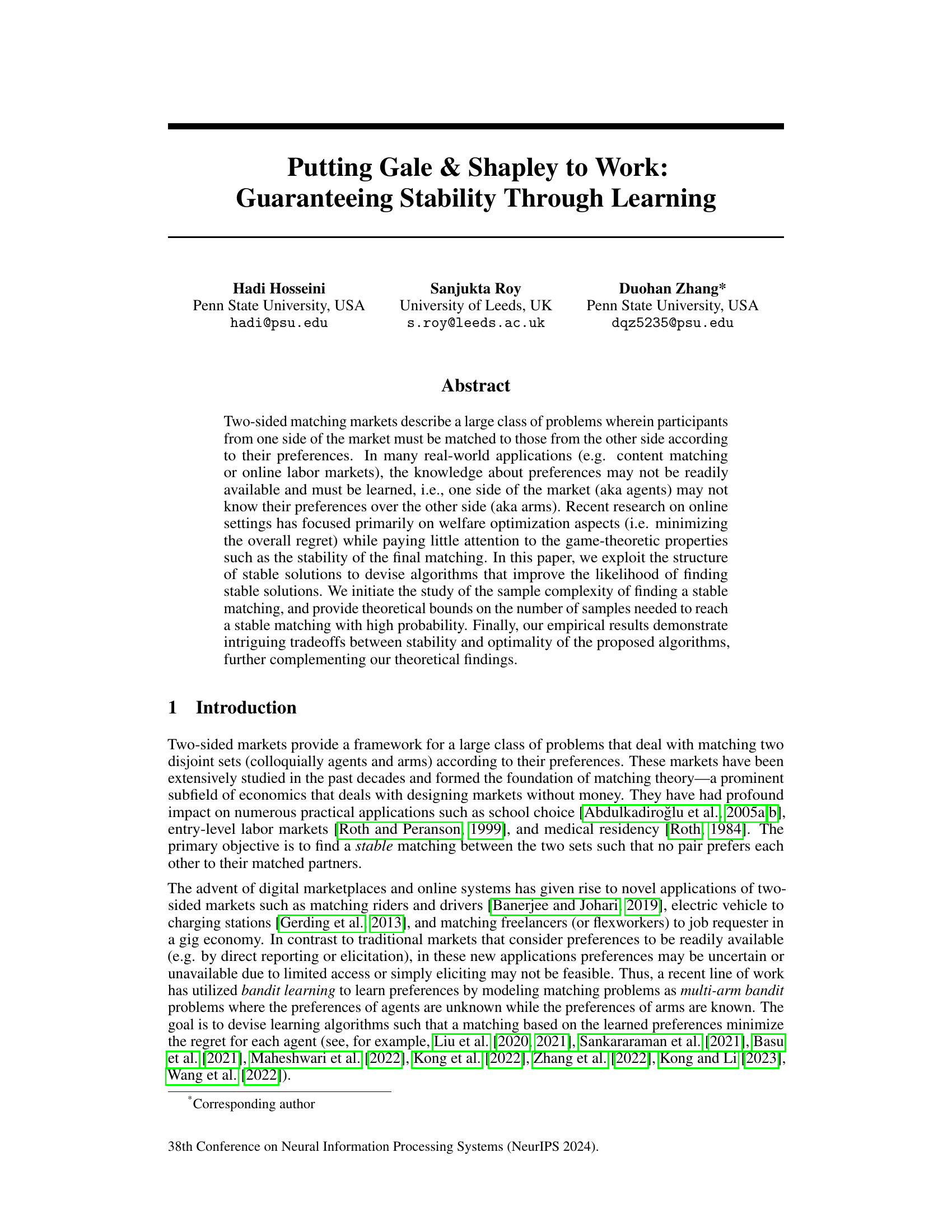

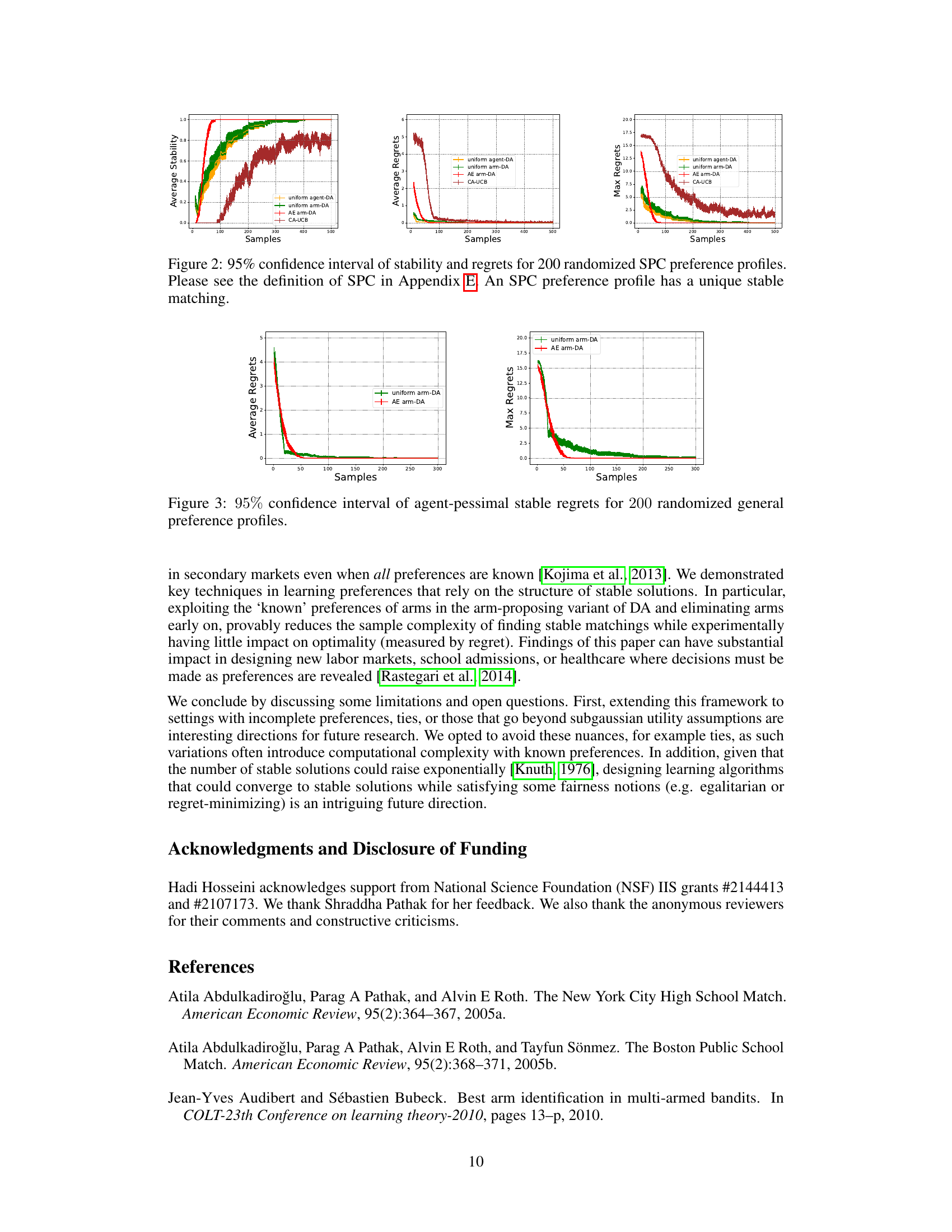

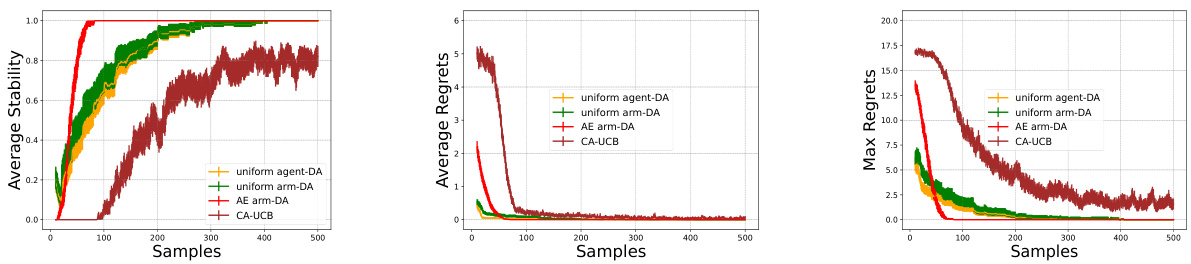

This figure displays the results of an experiment comparing four different algorithms for two-sided matching markets with 20 agents and 20 arms. The algorithms are evaluated based on their stability (the probability of producing a stable matching) and regret (the difference between the expected reward of the optimal matching and the obtained reward). The graph shows that the AE arm-DA algorithm significantly improves the probability of achieving a stable matching and offers comparable regret performance to other algorithms.

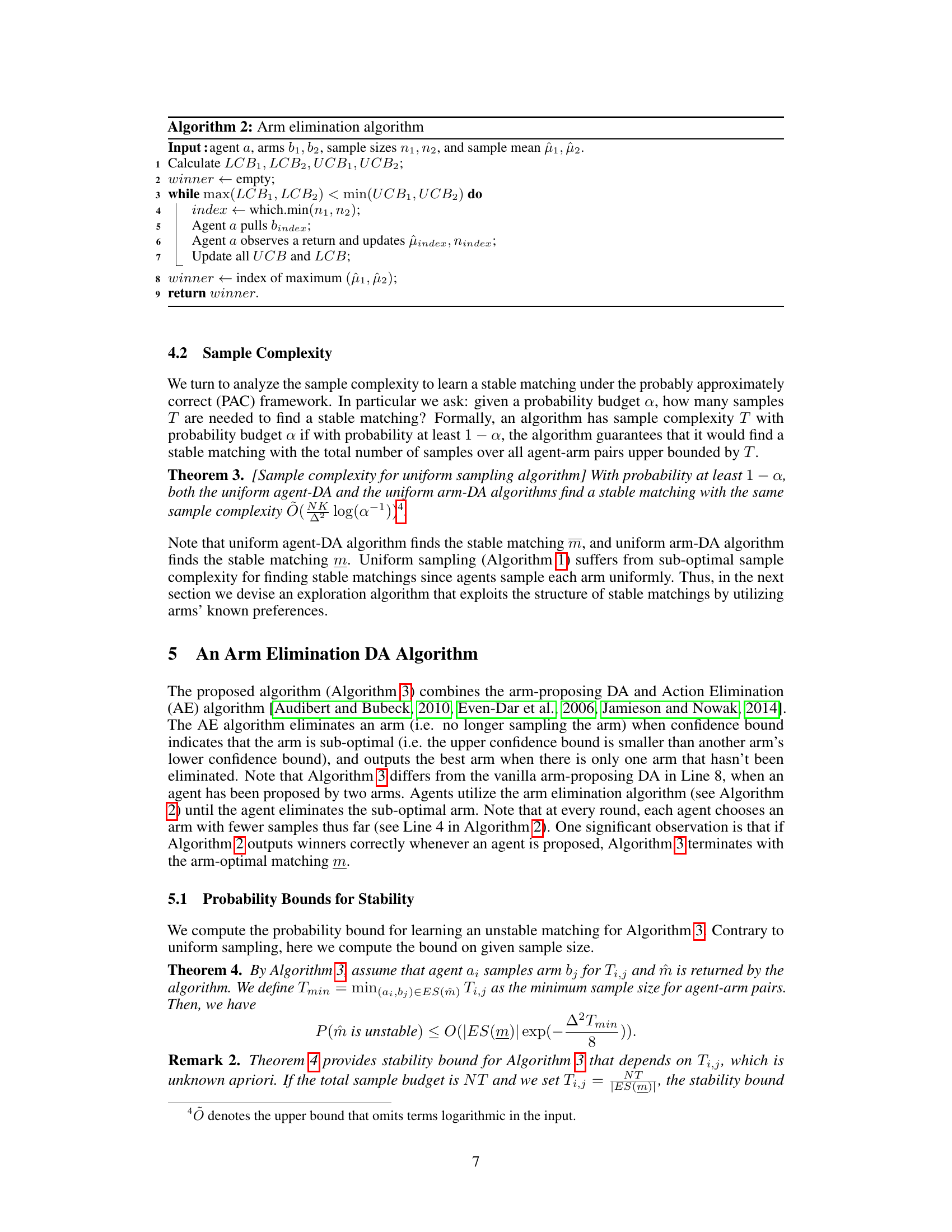

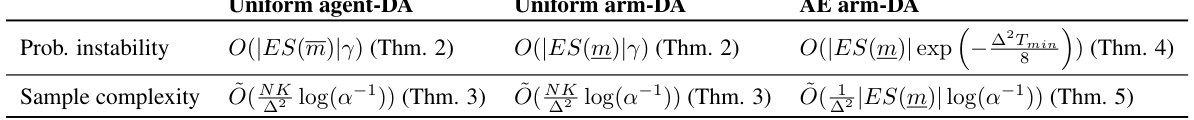

This table compares three different algorithms (Uniform agent-DA, Uniform arm-DA, and AE arm-DA) in terms of their probability of producing an unstable matching and their sample complexity for finding a stable matching. The probability bounds and sample complexities are expressed in terms of the size of the envy-set (ES(m)) and the minimum preference gap (Δ). The table also shows that the AE arm-DA algorithm has a lower sample complexity compared to the other two algorithms.

In-depth insights#

Stable Matching#

Stable matching, a core concept in two-sided matching markets, focuses on finding pairings where no two unmatched individuals mutually prefer each other over their assigned partners. Gale-Shapley’s deferred acceptance algorithm offers a crucial method for achieving a stable matching, though it often yields an outcome that favors one side of the market over the other. The stability itself is a desirable property, enhancing the long-term reliability and preventing participants from seeking alternative, less-regulated arrangements. However, real-world applications rarely feature readily available preference data, necessitating preference learning mechanisms and introducing uncertainty. The paper explores this uncertainty, examining how preference learning algorithms affect the likelihood of attaining a stable matching and investigating the trade-offs between stability and other metrics, such as regret minimization. A key challenge lies in determining the sample complexity—the data needed to achieve stability with a high degree of certainty—under various learning algorithms and preference profile characteristics. The research highlights the intriguing interplay between theoretical guarantees of stability and the practical realities of incomplete information, emphasizing that algorithms should be designed to balance these considerations effectively.

Bandit Learning#

Bandit learning, in the context of two-sided matching markets, addresses the challenge of learning participant preferences when this information isn’t readily available. This is crucial because many real-world matching scenarios, like online labor markets or content recommendation systems, operate with incomplete preference data. Traditional matching algorithms assume full knowledge of preferences, rendering them inapplicable in such settings. Bandit learning offers a solution by framing the problem as a multi-armed bandit problem, where each ‘arm’ represents a potential match, and pulling an arm corresponds to making a match and observing the outcome. Algorithms are then designed to balance exploration (trying different matches to gather preference information) and exploitation (making matches that are likely to yield high utility based on learned preferences). Key considerations within this framework include regret minimization (limiting the loss from making suboptimal matches), sample complexity (determining the number of matches needed to learn reliable preferences), and stability (ensuring that the final matching is stable, meaning no participants would prefer to switch partners given the learned preferences). The interplay between these aspects is a core focus in the research of bandit learning for two-sided matching markets. Significant advancements have been made in devising efficient algorithms that effectively balance these competing objectives and provide theoretical guarantees on their performance.

Sample Complexity#

The concept of ‘sample complexity’ is crucial in the context of this research paper because it directly addresses the efficiency of learning algorithms within two-sided matching markets. The core question is: How much data (samples) is needed to learn the participants’ preferences accurately enough to guarantee the discovery of a stable matching with high probability? The paper acknowledges the significance of this question by theoretically bounding sample complexity for various scenarios and algorithms. It introduces a novel metric, justified envy, to capture the structure of stable matchings and leverages it to derive tighter bounds. The analysis highlights a trade-off between achieving a stable matching and minimizing the overall regret, demonstrating the challenge inherent in designing algorithms that are both stable and efficient. The use of different sampling strategies (uniform vs. non-uniform) also plays a critical role in determining sample complexity. The non-uniform strategy, based on an arm-elimination deferred acceptance algorithm, is presented as a more efficient approach, suggesting that focusing the learning process on relevant parts of the preference space can significantly reduce the amount of data required. In essence, the analysis in ‘Sample Complexity’ lays the groundwork for understanding the efficiency and practical feasibility of learning-based approaches to two-sided matching problems.

Algorithmic Tradeoffs#

An analysis of algorithmic tradeoffs in the context of two-sided matching markets reveals inherent tensions between stability and optimality. Algorithms prioritizing stability, such as variants of the Deferred Acceptance algorithm, may sacrifice overall welfare or individual agent utility. Conversely, algorithms focused on maximizing welfare (minimizing regret) may yield unstable matchings, leading to blocking pairs and potential market disruptions. The key tradeoff lies in balancing the need for a stable solution to ensure market longevity against the desire for efficiency. Different sampling strategies (uniform vs. non-uniform) also introduce tradeoffs: uniform sampling offers simplicity but may require substantially more samples to achieve stability, whereas non-uniform methods, while potentially more efficient, add complexity. The optimal algorithm choice thus depends on the specific application and the relative importance placed on stability and efficiency.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally explore several key areas. Extending the framework to handle incomplete preferences, ties in preferences, and relaxing the subgaussian utility assumptions would significantly broaden applicability. Addressing the exponential growth in the number of stable solutions with increasing problem size requires innovative algorithmic approaches, potentially drawing on techniques from constraint satisfaction or approximation algorithms. Investigating fairness considerations within the context of stable matchings is critical, exploring various fairness notions (e.g., egalitarian, proportional) and their trade-offs with stability and efficiency. Finally, it would be valuable to empirically evaluate the algorithms in diverse, real-world settings such as online labor markets or ride-sharing platforms, to assess their performance in the presence of noise, adversarial agents, and dynamically changing preferences. Analyzing stability in the context of many-to-one matching is another important avenue for future research, given the frequent use of this model in real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

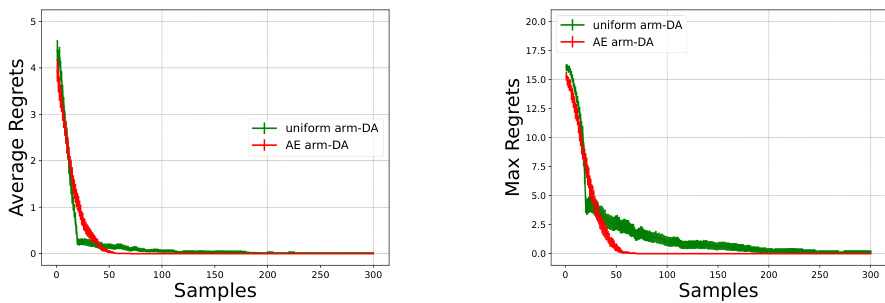

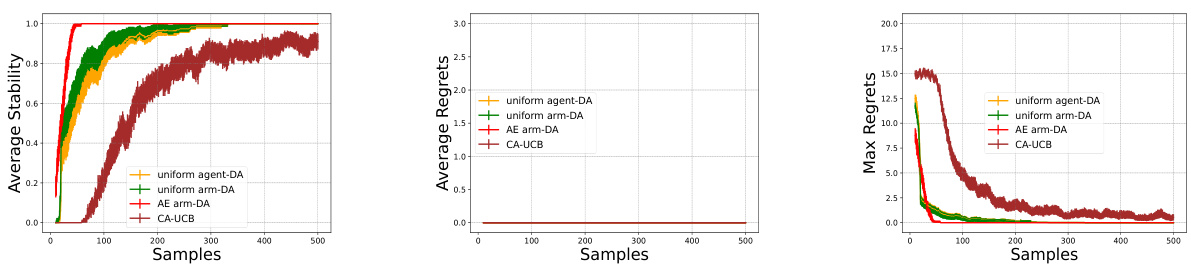

This figure displays the results of simulations comparing four different algorithms for two-sided matching markets with general preference profiles. The x-axis represents the number of samples used to estimate preferences. The y-axis of the leftmost graph shows the average stability (proportion of stable matchings) over the 200 simulations. The middle and rightmost graphs display average and maximum regret (difference between the expected reward of an optimal matching and the achieved reward), respectively. The four algorithms are compared: uniform agent-DA, uniform arm-DA, AE arm-DA, and CA-UCB. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

This figure displays the results of an experiment comparing four algorithms: uniform agent-DA, uniform arm-DA, AE arm-DA, and CA-UCB. The experiment involved 200 simulations with randomized general preference profiles. The graphs show the average stability, average regret, and maximum regret across these simulations, plotted against the number of samples. Error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals are also provided.

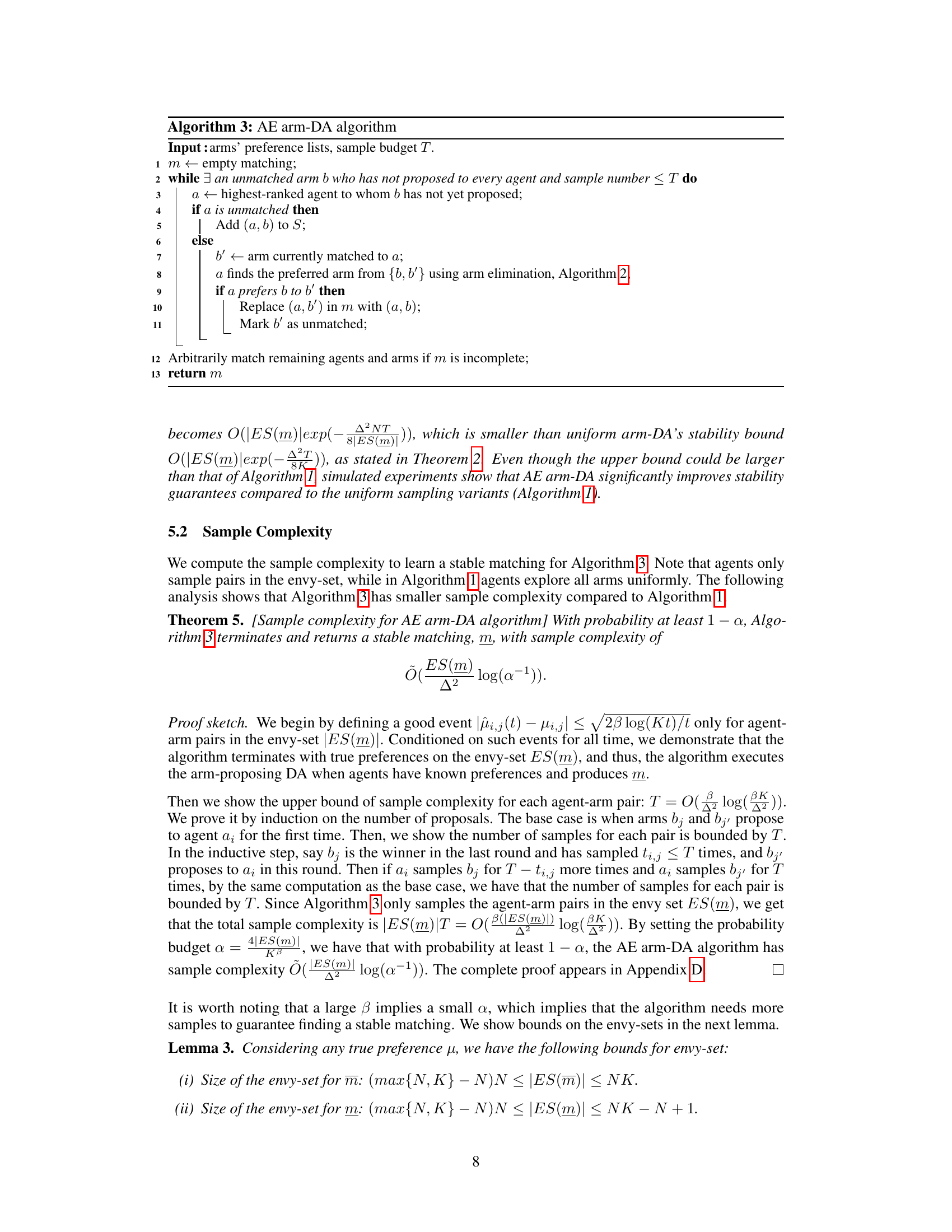

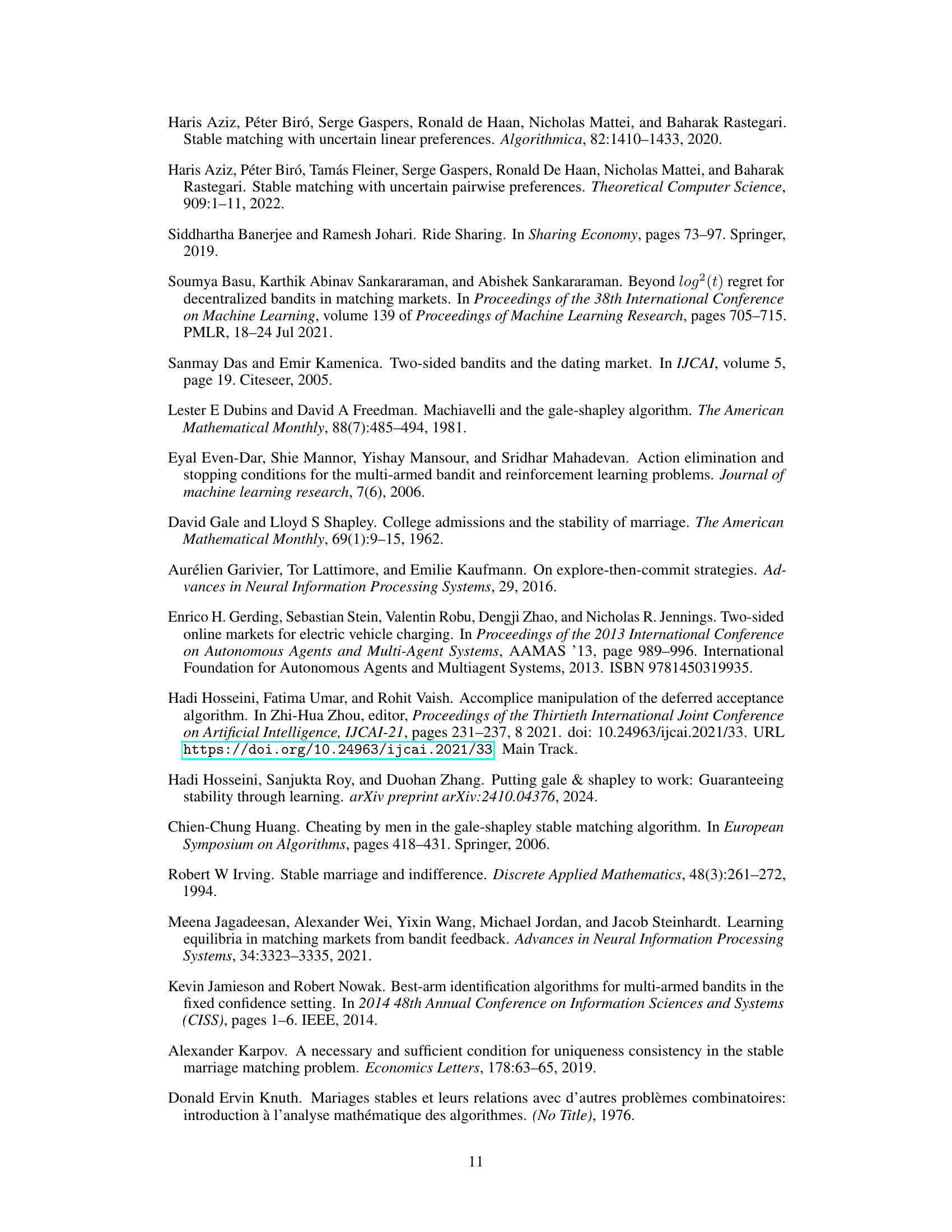

This figure shows the 95% confidence interval of agent-pessimal stable regrets for 200 randomized general preference profiles. Agent-pessimal stable regret measures how much worse off an agent is in the obtained stable matching compared to the agent-optimal stable matching (the best possible outcome for the agent). The figure compares four algorithms: uniform agent-DA, uniform arm-DA, AE arm-DA, and CA-UCB. The x-axis represents the number of samples, and the y-axis represents the average regret.

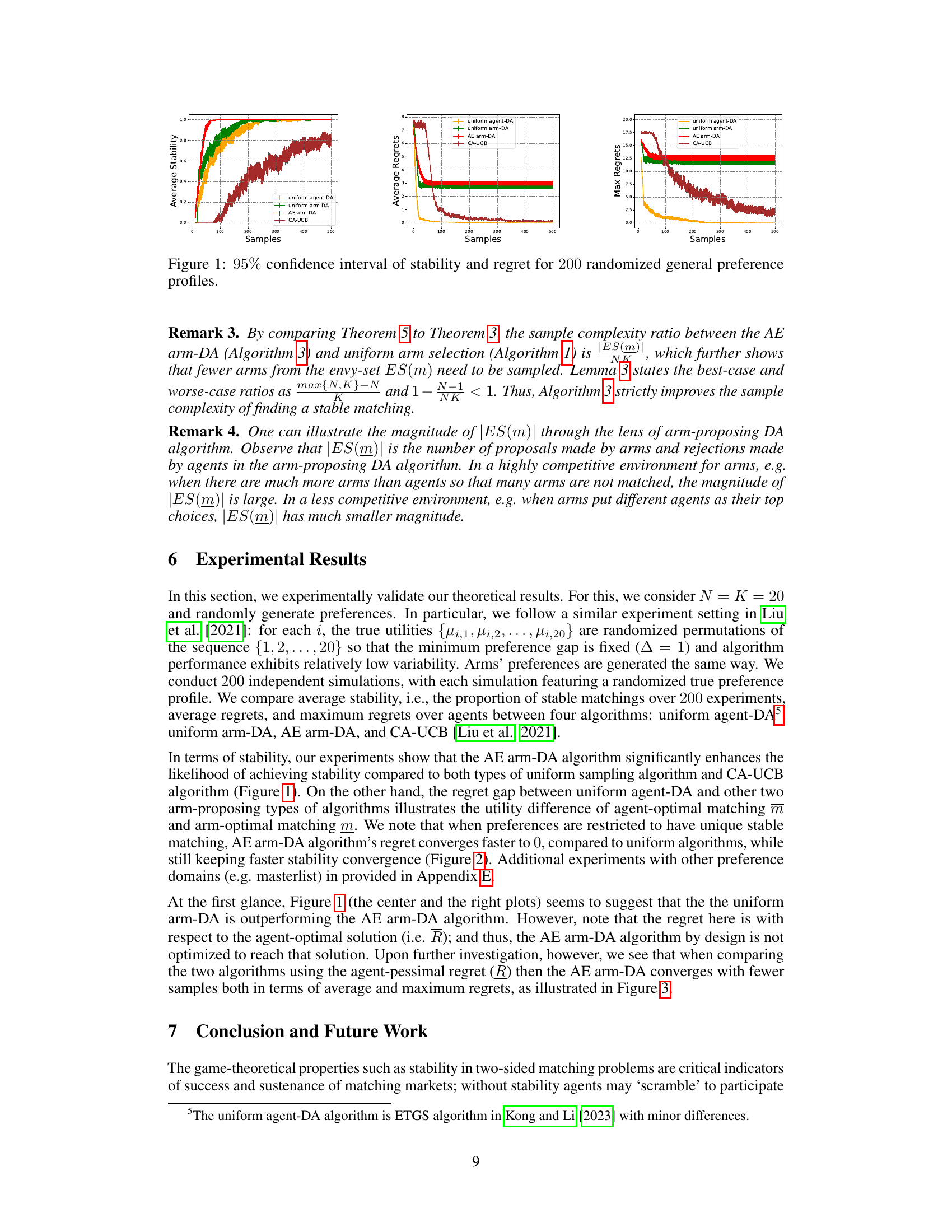

This figure displays the results of a simulation comparing four different algorithms for two-sided matching markets with 20 agents and 20 arms. The algorithms are evaluated based on their ability to achieve a stable matching (stability) and their cumulative regret (average and maximum regret). The x-axis represents the number of samples used in the learning process, and the y-axis shows the performance metrics for each algorithm. The figure illustrates that the AE arm-DA algorithm offers a higher probability of producing a stable matching compared to the others, although regret may be higher compared to the uniform agent-DA.

More on tables

This table summarizes the theoretical results on the probability of unstable matchings and the sample complexity for three different algorithms: Uniform agent-DA, Uniform arm-DA, and AE arm-DA. Each algorithm’s performance is evaluated based on two key metrics: the probability of producing an unstable matching and the number of samples required to find a stable matching. The table shows that the AE arm-DA algorithm offers improved performance in terms of sample complexity compared to the other two, especially when considering the probability of generating unstable matchings.

This table compares three different algorithms for finding stable matchings in two-sided markets: uniform agent-DA, uniform arm-DA, and AE arm-DA. For each algorithm, it provides the order of magnitude of the probability of finding an unstable matching and the sample complexity (number of samples needed) to find a stable matching. The bounds are expressed in terms of ES(m), which represents the size of the envy-set in the stable matching m, and also depends on the minimum preference gap Δ. The AE arm-DA algorithm is shown to have a lower sample complexity than the other two algorithms.

Full paper#