↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current speech dysfluency models are limited by scalability, lack of large-scale datasets, and ineffective learning frameworks. This paper addresses these issues by proposing SSDM, which uses articulatory gestures for scalable alignment, thus overcoming limitations of existing methods.

SSDM also introduces the Connectionist Subsequence Aligner (CSA) for accurate dysfluency detection and utilizes a large-scale simulated dysfluency corpus (Libri-Dys). The model’s performance is evaluated against existing methods, demonstrating significant improvements in accuracy and efficiency and paving the way for further development of AI-based speech therapy tools.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in speech therapy and language learning because it introduces SSDM, a scalable and effective model for speech dysfluency. Its open-source nature and large-scale dysfluency corpus, Libri-Dys, will accelerate progress in this area, enabling the development of more effective AI-based tools for diagnosis and treatment. The integration of large language models and the innovative use of articulatory gestures provide new avenues for investigation.

Visual Insights#

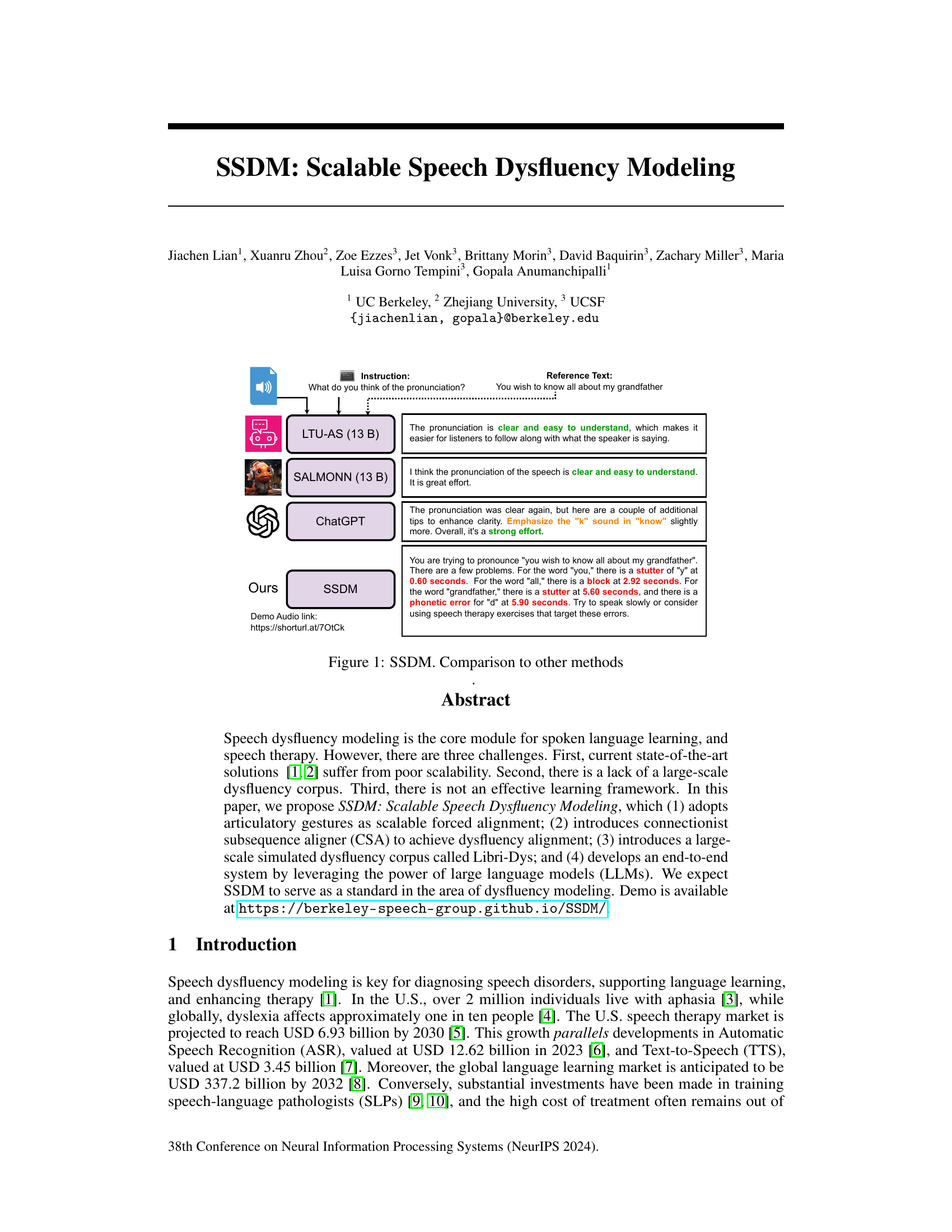

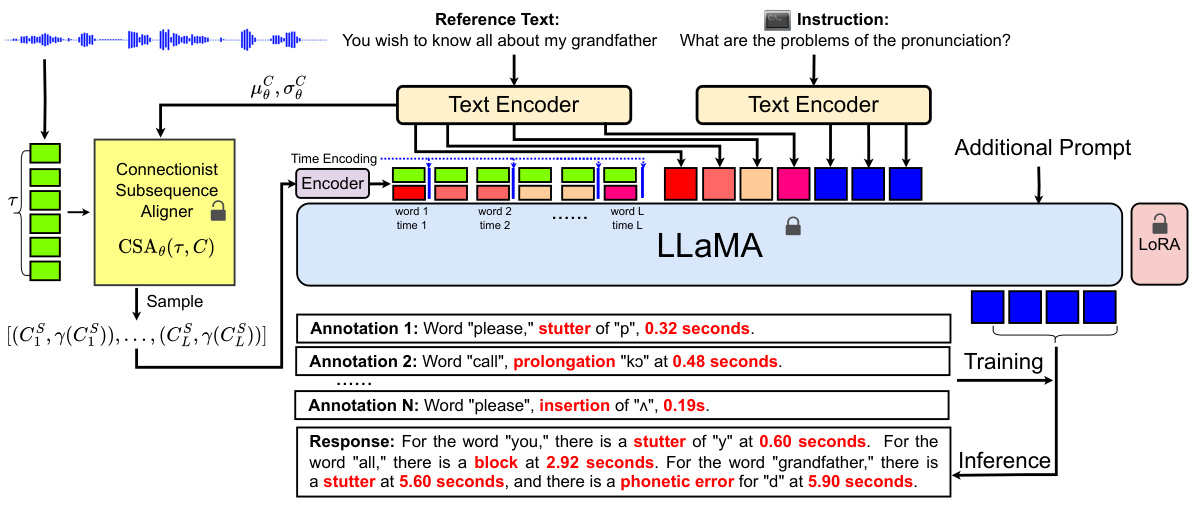

This figure compares the performance of the proposed SSDM model with other state-of-the-art methods (LTU-AS, SALMONN, ChatGPT) on a speech pronunciation task. The comparison is based on the clarity and understandability of the pronunciation, as assessed by human evaluation. The results demonstrate that SSDM outperforms the other methods in terms of identifying and describing specific dysfluencies in speech, such as stutters, blocks and phonetic errors.

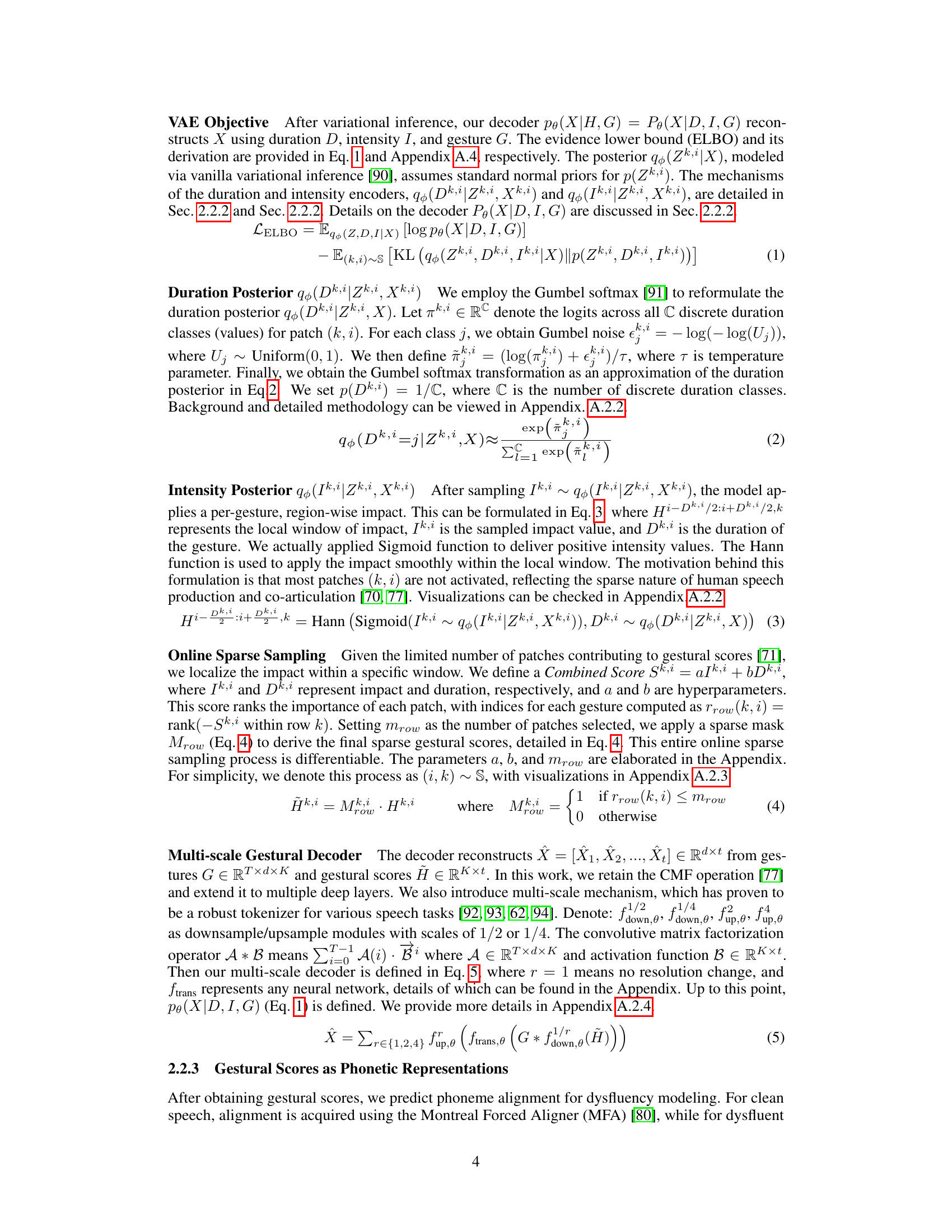

This table presents the results of evaluating the phonetic transcription performance of different methods on the VCTK++, LibriTTS, and Libri-Dys datasets. It compares the performance of HuBERT, H-UDM, and the proposed Gestural Score (GS) method, with and without self-distillation, across various training data sizes. The evaluation metrics used are framewise F1 score (higher is better) and Duration-Aware Phoneme Error Rate (dPER, lower is better). The table also provides scalability factors (SF1 and SF2) showing the relative performance gains as the dataset size increases.

In-depth insights#

Gestural Modeling#

Gestural modeling, as presented in this research paper, offers a novel approach to speech representation by grounding it in the fundamental physics of articulatory movements. The key idea is to represent speech not as raw acoustic signals, but as the kinematic patterns of articulatory gestures. This approach is particularly advantageous for modeling speech dysfluency because it directly addresses the physical sources of dysfluencies, such as stuttering or misarticulations. Unlike traditional acoustic-based methods, gestural modeling is inherently scalable since it doesn’t rely on high-dimensional acoustic features that can be computationally expensive to process. The use of articulatory gestures simplifies the detection of dysfluencies in speech, as it provides direct and meaningful insight into the nature of the speaker’s articulatory movements. Furthermore, gestural modeling offers an intuitive visualization that enhances the explainability of dysfluency detection systems. This method leverages variational autoencoders and advanced neural network techniques to extract meaningful features from articulatory data, paving the way for more accurate and efficient speech dysfluency modeling.

CSA Aligner#

The proposed Connectionist Subsequence Aligner (CSA) offers a novel approach to aligning dysfluent phonetic sequences with reference texts, addressing limitations of traditional methods. Unlike global alignment techniques like Dynamic Time Warping (DTW), which consider all possible alignments, CSA leverages a monotonic constraint, focusing on semantically meaningful subsequences. This makes it more robust to noise and variations in dysfluent speech. By employing a differentiable formulation, CSA integrates seamlessly into an end-to-end neural framework, enabling efficient training and parameter optimization. Its design is crucial because it efficiently captures the essence of dysfluency by linking phoneme sequences in a way that respects the semantic context, even in the presence of irregularities like insertions, repetitions, or deletions. This is achieved via a connectionist architecture inspired by the longest common subsequence (LCS) algorithm, but unlike LCS, CSA is fully differentiable, paving the way for end-to-end training and enhancing scalability. This approach is particularly useful for dysfluency detection and localization, as the aligner’s output directly reflects the presence and type of dysfluencies within the speech. Furthermore, the algorithm’s scalability compared to previous methods is a significant advantage, allowing for training on large-scale datasets and potentially leading to more accurate and comprehensive dysfluency models.

Libri-Dys Corpus#

The creation of Libri-Dys, a large-scale simulated dysfluency corpus, is a significant contribution to the field. Its novelty lies in simulating dysfluency at the phonetic level, rather than using acoustic-based methods. This approach produces more naturalistic dysfluent speech. The corpus is substantially larger than existing datasets, offering improved scalability and better representation of diverse dysfluency types and their temporal characteristics. Open-sourcing Libri-Dys is also commendable, fostering collaborative research and accelerating progress in speech dysfluency modeling. The paper’s inclusion of detailed methods for data creation will allow other researchers to build upon their approach, while its evaluation of the dataset’s quality shows its potential for diverse applications.

Scalability & Limits#

A key consideration in any machine learning model, especially one dealing with complex data like speech, is scalability. A model’s ability to handle increasing amounts of data and computational demands directly impacts its real-world applicability. Scalability challenges often arise from the size of the training datasets and the model’s architecture. This research paper likely investigates the efficiency of various speech dysfluency detection techniques under varied data volumes. The section on ‘Scalability & Limits’ would delve into the model’s performance when dealing with diverse datasets, particularly analyzing trade-offs between accuracy, computational costs, and the amount of data required for adequate training. Limitations might involve restrictions on hardware requirements, dataset size constraints, or difficulties in handling diverse acoustic features. The discussion would highlight the practical constraints of the proposed model and pinpoint areas where further improvements are needed to enhance the system’s ability to operate effectively at a large scale. Ultimately, it would evaluate how well the model’s performance scales and identify scenarios where its effectiveness might be compromised.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this scalable speech dysfluency model (SSDM) could explore several avenues. Improving the LLM integration is crucial, potentially through a phoneme-level language model for finer-grained dysfluency detection. Expanding the dataset is another key area; while Libri-Dys is substantial, a more diverse range of dysfluencies and speakers would enhance robustness. Investigating alternative representations, such as those based on rtMRI or more advanced gestural scores, could offer valuable insights. Furthermore, exploring the combination of region-based and token-based approaches, which are currently being explored, could lead to novel and more comprehensive solutions for dysfluency modeling. Finally, thorough clinical validation of the model is imperative to ensure its effectiveness in real-world speech therapy applications. This multifaceted approach promises significant advancements in speech therapy and language learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

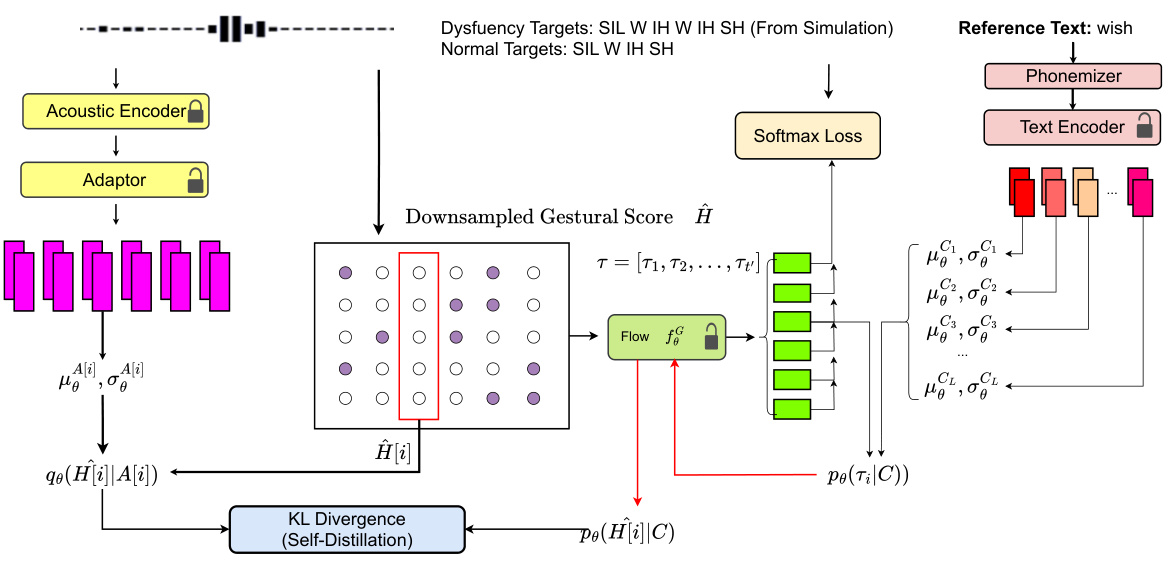

This figure shows the architecture of the Scalable Speech Dysfluency Modeling (SSDM) system. The input is dysfluent or normal speech, and the reference text is provided. The system uses an acoustic encoder, adaptor, and articulatory gesture-based representation to achieve dysfluency alignment through a Connectionist Subsequence Aligner (CSA). The model employs a multimodal tokenizer and LLaMA (Large Language Model Meta AI) with LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) for end-to-end learning. Self-distillation is also utilized in the process to refine the model’s performance. The output is the identified dysfluencies with their corresponding timestamps.

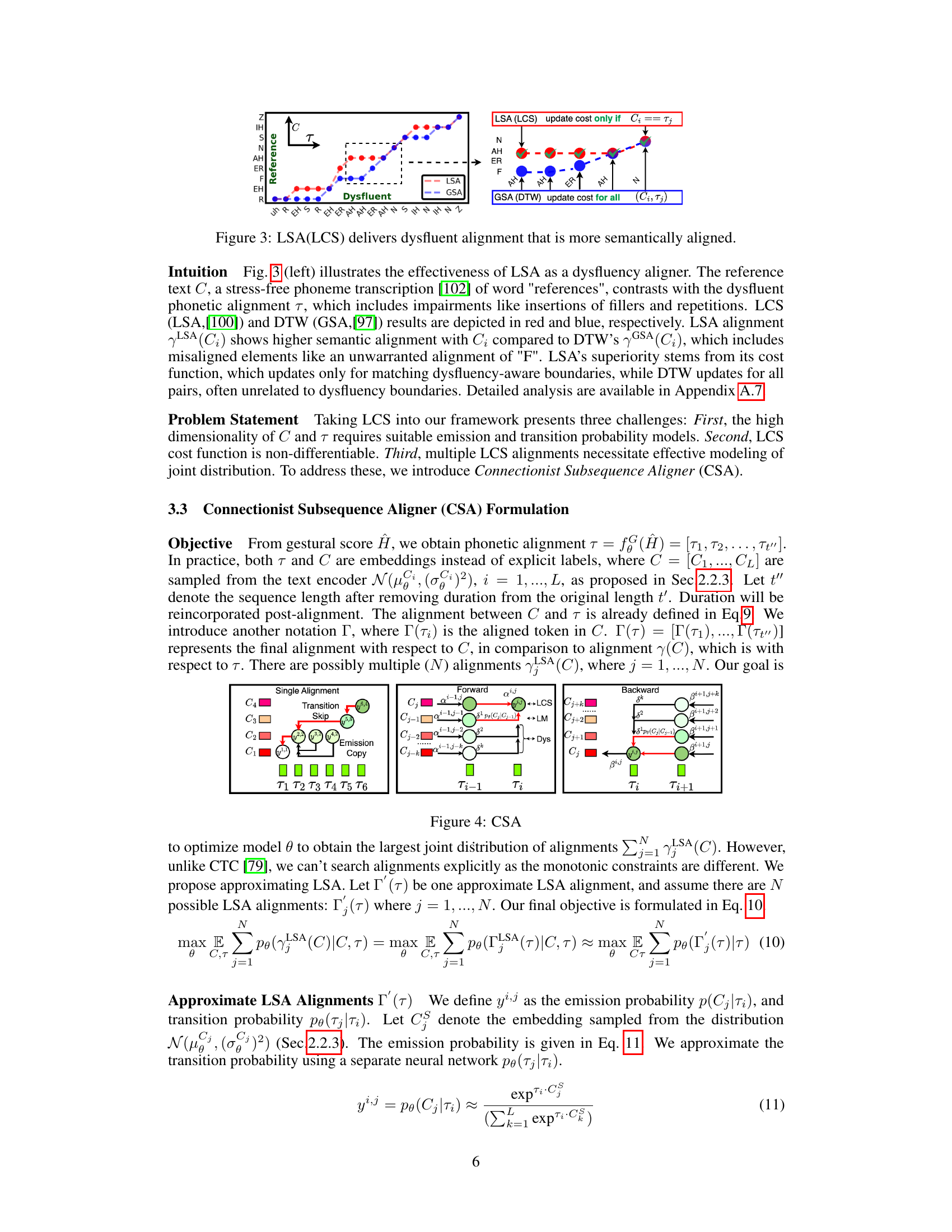

This figure provides a visual comparison of Local Subsequence Alignment (LSA) and Global Sequence Alignment (GSA) methods for dysfluency alignment. It uses a specific example of the word ‘references’ pronounced with dysfluencies. The left side shows a graphical representation of the dysfluent phonetic alignment (red dots representing LSA and blue dots representing GSA) against the stress-free phonetic transcription of the word ‘references’. The right side provides a more detailed analysis of the differences in cost functions and alignment methods between LSA and GSA, highlighting how LSA focuses on semantically meaningful alignments, whereas GSA considers all pairs of phonemes for calculating cost and generating alignment. This illustrative example demonstrates LSA’s superior ability to accurately detect and align dysfluencies compared to GSA.

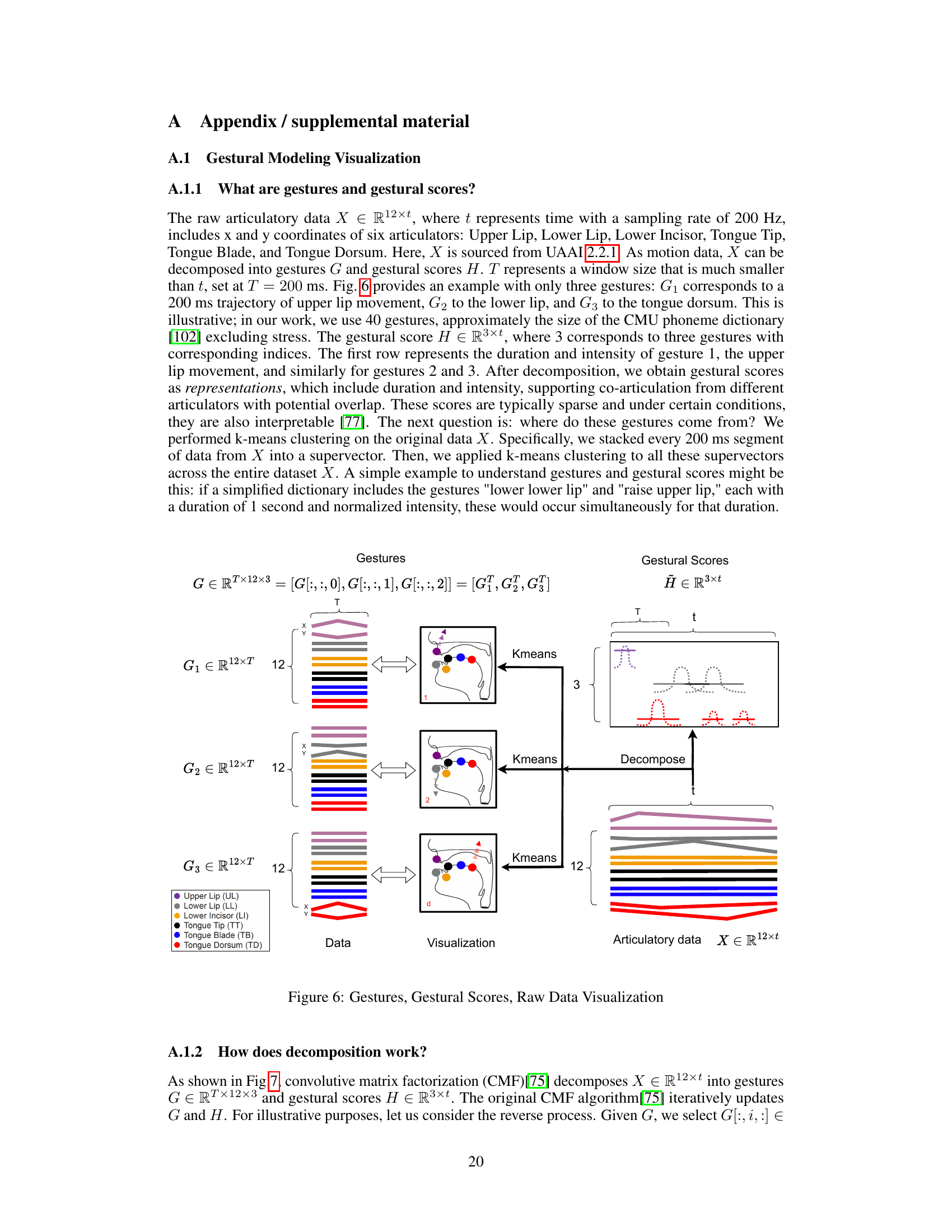

This figure illustrates the Connectionist Subsequence Aligner (CSA) architecture. It shows how CSA approximates Local Subsequence Alignment (LSA) by incorporating the constraints of LCS (Longest Common Subsequence) into a modified forward-backward algorithm similar to CTC (Connectionist Temporal Classification). The figure highlights the concepts of ‘Transition Skip’ and ‘Emission Copy’ to handle non-monotonic alignments effectively while still maintaining differentiability. It also demonstrates how dysfluencies are implicitly modeled through a discounted factor applied to previous tokens.

The figure visualizes dysfluency using GradCAM applied to gestural scores. The left panel shows articulatory movements, while the right panel displays the gradient of gestural scores for the vowel ‘i’ (e). Negative gradient in the center indicates incorrect tongue movement direction during articulation, offering insight into the dysfluency.

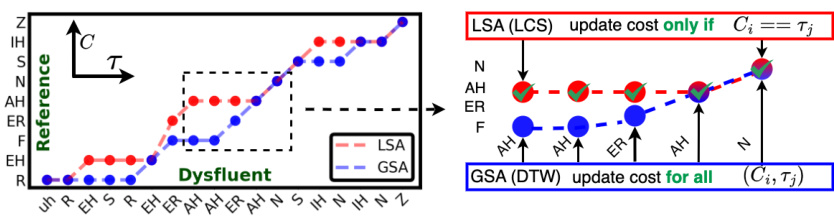

This figure illustrates the process of decomposing raw articulatory data into gestures and gestural scores. Raw articulatory data, represented as a matrix X (12 x t), contains the x and y coordinates of six articulators (upper lip, lower lip, lower incisor, tongue tip, tongue blade, and tongue dorsum) over time (t). K-means clustering is used on 200ms segments of the articulatory data to identify a set of gestures (G, shown as a 12 x T matrix for each gesture). The number of gestures used in the paper is 40. The resulting gestural scores (H, a 3 x t matrix) represent the duration and intensity of each gesture over time. The figure provides visual representations of the raw data, the extracted gestures, and the resulting gestural scores.

This figure illustrates the process of convolutive matrix factorization (CMF). It shows how raw articulatory data (X) is decomposed into gestures (G) and gestural scores (H). Gestures represent the articulatory movements, and gestural scores represent the duration and intensity of these movements. The figure visually depicts the convolution operation between gestures and gestural scores to reconstruct the raw articulatory data. The figure is used to explain how the model decomposes complex articulatory movements into simpler, interpretable components.

This figure illustrates the process of implicit duration and intensity modeling in the neural variational gestural modeling framework. The input is raw articulatory data X. A latent encoder processes this data and generates latent representations Z. These representations are used by the intensity and duration encoders to predict intensity (Ik,i) and duration (Dk,i) posteriors for each gesture. The intensity posteriors are passed through a sigmoid function to ensure positivity. The duration posteriors are obtained using Gumbel Softmax to account for the non-differentiability of the sampling process. These predicted intensity and duration are combined with a Hann window to create the final gestural scores H. The process highlights the use of a latent encoder for generating latent representations and shows how these are used in predicting the intensity and duration of gestures, ultimately creating the gestural scores.

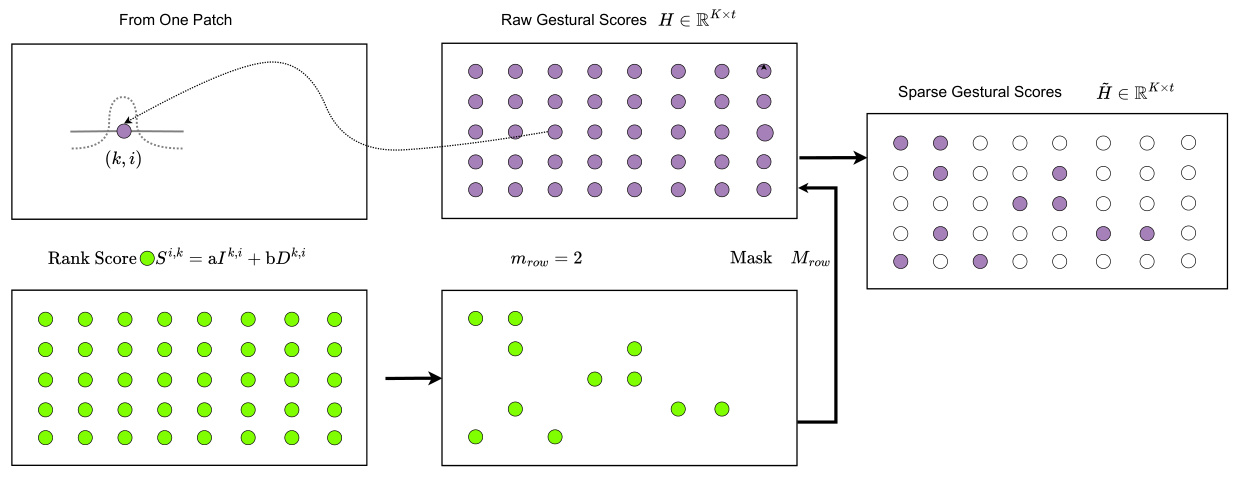

This figure illustrates the sparse sampling process applied to the gestural scores. It starts with a matrix of raw gestural scores, each element (k,i) having a rank score calculated from its intensity and duration. Then, a mask is applied based on the top mrow scores, resulting in a sparse matrix where only the highest-ranked elements are retained. This process is essential for creating more efficient representations for downstream tasks.

This figure illustrates the multi-scale gestural decoder architecture. The gestural scores, initially in a dense matrix form, undergo sparse sampling to reduce the number of patches that contribute to gestural scores. These sparse gestural scores then pass through downsampling modules (1/2 and 1/4), followed by a transformation network and upsampling modules, to reconstruct the articulatory data, X. The final representation is downsampled to ensure consistency with acoustic features from WavLM.

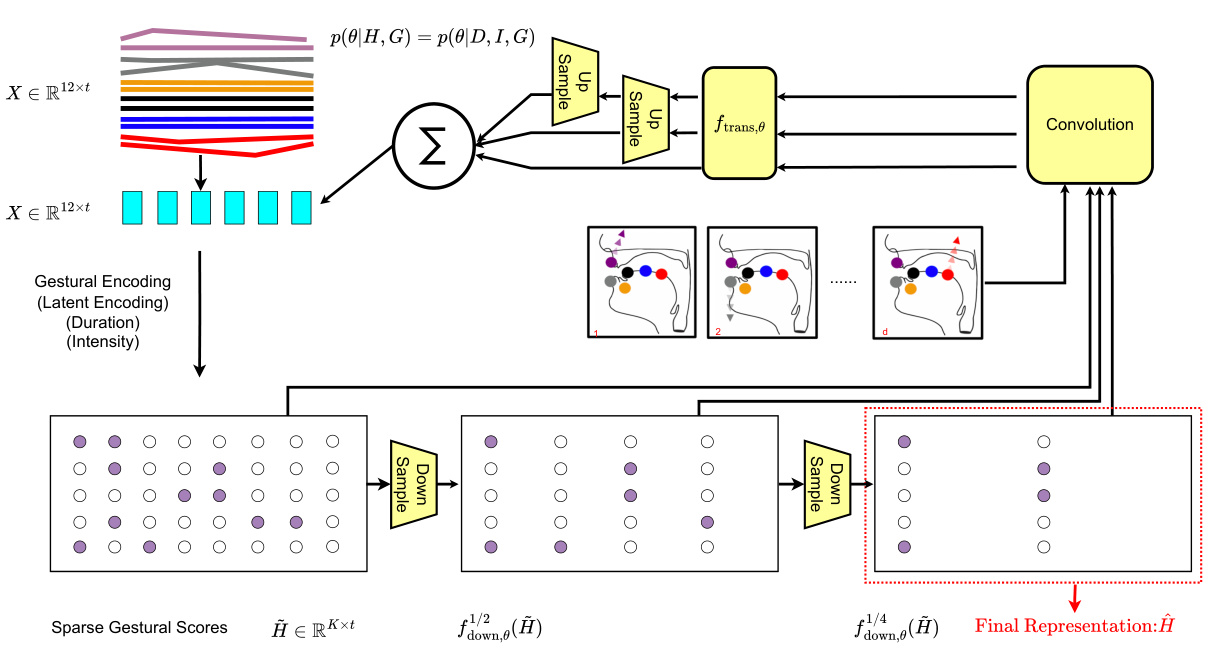

This figure illustrates the self-distillation process used in the SSDM model. The acoustic encoder processes the input speech, and the adaptor generates acoustic embeddings. The downsampled gestural scores (Ĥ) are processed through a flow model. This flow model produces the posterior distribution qθ(Ĥ[i]|A[i]) for each time step i. Meanwhile, a text encoder processes the reference text, resulting in the prior distribution pθ(Ĥ[i]|C) for each time step. The KL divergence between these posterior and prior distributions is used as a loss function to guide the learning process. This method helps to improve the model’s ability to align acoustic and text information, and this process is called self-distillation.

This figure presents the overall architecture of the Scalable Speech Dysfluency Modeling (SSDM) system. It shows the various components and their interactions, including the acoustic encoder, adaptor, text encoder, connectionist subsequence aligner (CSA), multimodal tokenizer, and LLaMA language model. The diagram illustrates the flow of information from the dysfluent speech input to the final dysfluency alignment and response. Key components such as the gestural encoder, multimodal tokenizer, and LLaMA are highlighted, showcasing the multi-modal approach used in the SSDM framework.

This figure illustrates the pipeline used for simulating dysfluent speech using LibriTTS. The process starts by converting the reference text into IPA sequences. Then, dysfluencies (repetition, missing, block, replacement, prolongation) are added based on pre-defined rules. The dysfluent IPA sequences are then fed into StyleTTS2 to generate the dysfluent speech. Finally, the dysfluent speech is annotated with the type and time of dysfluencies.

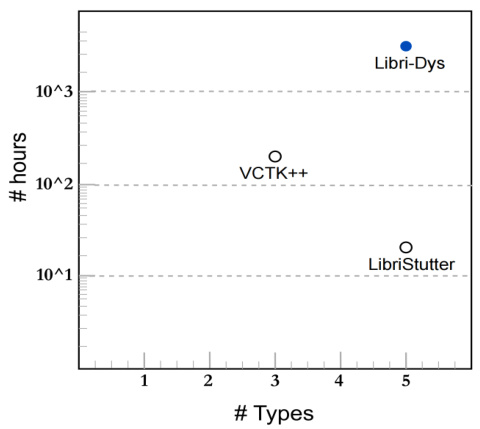

This figure compares the scale and number of dysfluency types in three simulated dysfluency datasets: Libri-Dys, VCTK++, and LibriStutter. The x-axis represents the number of dysfluency types in each dataset, and the y-axis shows the total number of hours of audio in each dataset using a logarithmic scale. It visually demonstrates that Libri-Dys is significantly larger and has more diverse dysfluency types than the other two datasets, highlighting its value as a training resource.

The figure uses an example to compare the performance of LSA (LCS) and GSA (DTW) in aligning dysfluent speech with its reference text. LSA focuses on matching only semantically relevant portions, resulting in a more accurate and meaningful alignment for dysfluent speech, unlike GSA, which considers all pairings. This difference is particularly evident when dealing with missing, repeated, or inserted phonemes in the dysfluent speech. The image uses a specific example of the word ‘references’ with various dysfluencies to highlight LSA’s superior performance.

More on tables

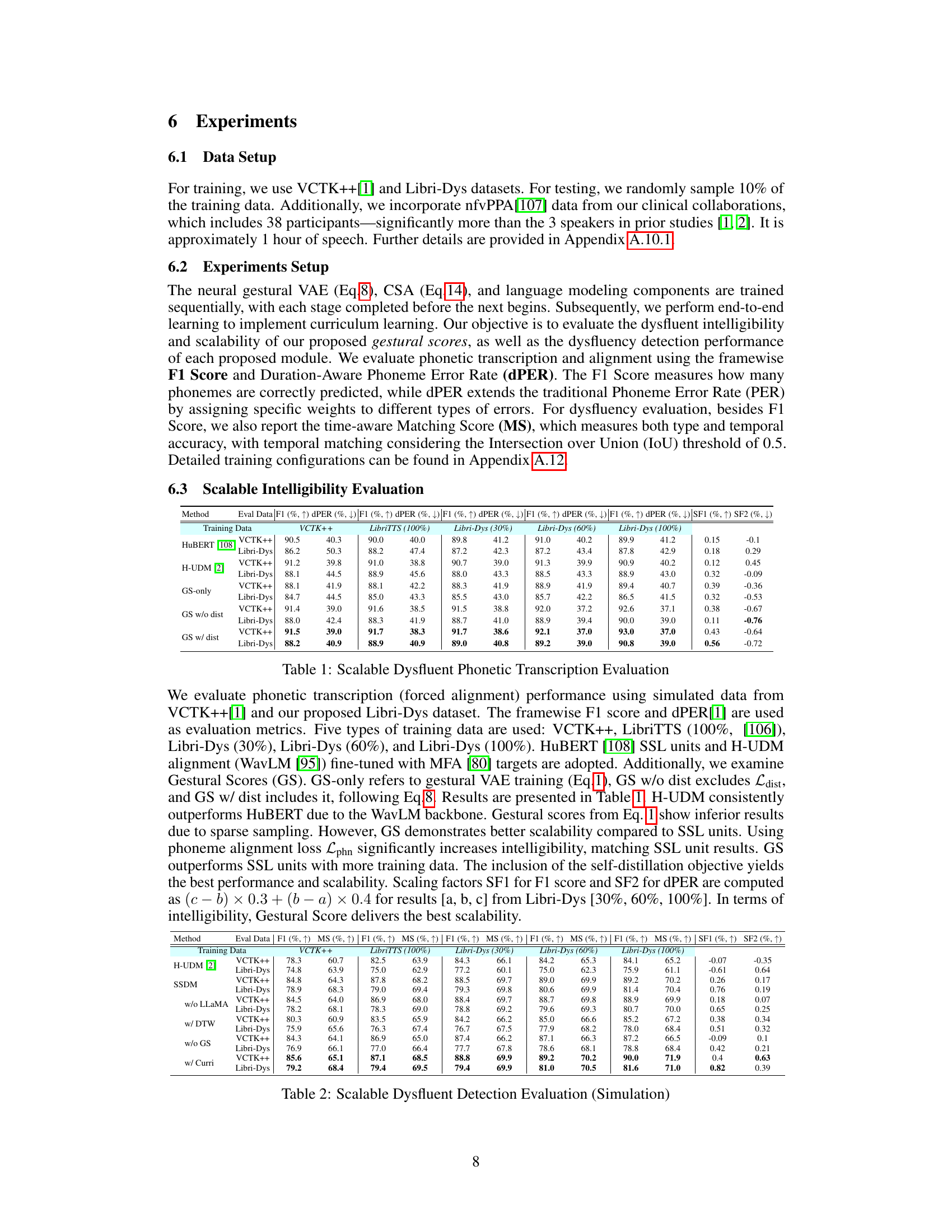

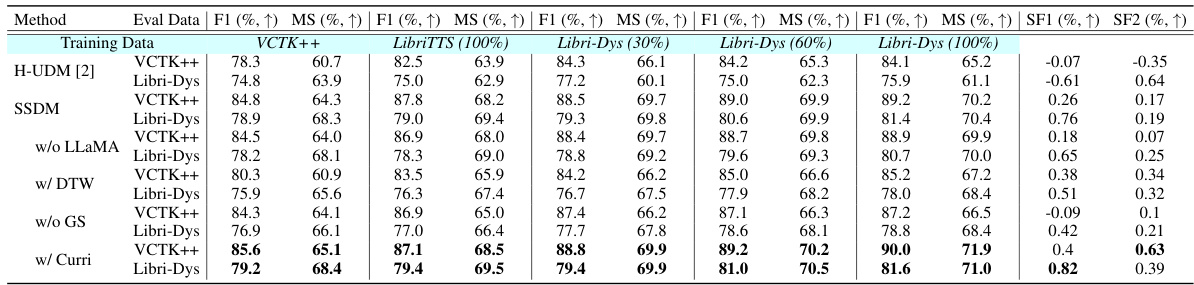

This table presents the results of a simulation evaluating the performance of the proposed SSDM model and its variants in detecting dysfluencies. It shows F1 scores (type match) and Matching Scores (MS) for various configurations of the model across different datasets (VCTK++, LibriTTS, Libri-Dys with varying amounts of training data), highlighting the impact of different model components like the language model (LLaMA), the connectionist subsequence aligner (CSA), and gestural scores. Scalability factors (SF1 and SF2) are also provided, indicating how well the model scales with increasing amounts of data.

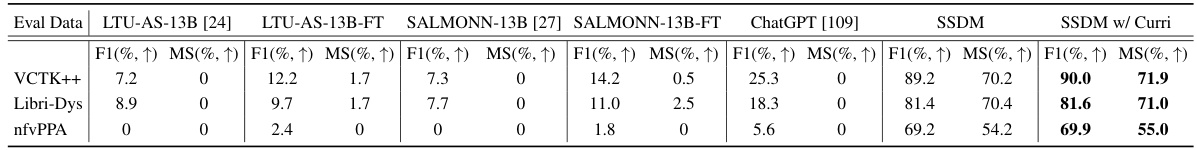

This table presents a comparison of the dysfluency detection performance of SSDM against several state-of-the-art models, including LTU-AS-13B, SALMONN-13B, and ChatGPT. The evaluation is performed on three datasets: VCTK++, Libri-Dys, and nfvPPA. The metrics used are F1 score (representing the accuracy of the dysfluency type prediction) and MS (matching score, incorporating temporal accuracy). The results demonstrate that SSDM achieves significantly higher F1 and MS scores across all datasets compared to the other models, highlighting its superior performance in dysfluency detection.

This table compares the distribution of different types of dysfluencies in two datasets: VCTK++ and Libri-Dys. It shows the number of samples and the percentage of each dysfluency type (Prolongation, Block, Replacement, Repetition (Phoneme), Repetition (Word), Missing (Phoneme), Missing (Word)) present in both datasets. The total hours of audio for each dataset are also provided. The table highlights the significant increase in the size and diversity of dysfluencies in the Libri-Dys dataset compared to VCTK++.

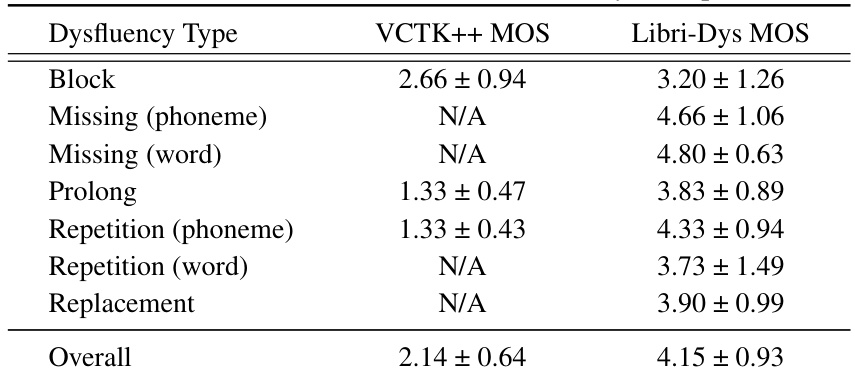

This table presents the Mean Opinion Score (MOS) ratings for the quality and naturalness of dysfluent speech samples generated using two different datasets: VCTK++ and Libri-Dys. MOS ratings are given on a scale of 1-5, with 5 being the highest score. The table compares the overall MOS scores and provides a breakdown by dysfluency type (Block, Missing (phoneme and word), Prolong, Repetition (phoneme and word), and Replacement). The results show that the Libri-Dys dataset produces samples that are rated significantly higher in quality and naturalness compared to those from the VCTK++ dataset. Note that some dysfluency types are not present in the VCTK++ dataset, resulting in ‘N/A’ entries for those categories.

This table compares the phoneme error rate (PER) for LibriTTS and Libri-Dys datasets. LibriTTS represents clean speech, while Libri-Dys contains various types of simulated dysfluencies. The PER is broken down for different types of dysfluencies in Libri-Dys, showing the impact of each dysfluency type on speech recognition accuracy.

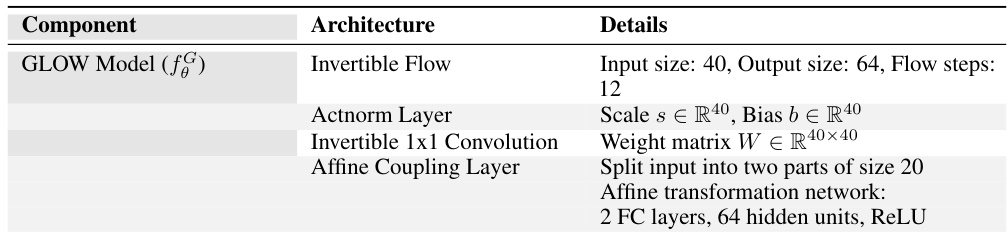

This table details the architecture of the Glow model used in the paper. It breaks down the invertible flow into its constituent components: Actnorm Layer, Invertible 1x1 Convolution, and Affine Coupling Layer. For each component, the specific parameters and configurations (such as input/output sizes, number of layers, activation functions) are listed.

Full paper#