↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Decentralized machine learning, using multiple workers for faster model training, is hampered by asynchronous computation and communication. Existing methods struggle with varying worker speeds and communication delays, leading to suboptimal performance. The challenge lies in designing algorithms that are both fast and robust to these unpredictable factors.

This paper tackles this by developing two new algorithms, Fragile SGD and Amelie SGD, that significantly improve upon current methods. These algorithms are not only provably faster (near-optimal for homogeneous settings) but also demonstrate robustness to heterogeneous worker and communication speeds. The paper also provides rigorous theoretical analysis, including new lower bounds on the achievable performance, thereby validating the optimality of the proposed algorithms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in decentralized optimization because it establishes nearly optimal time complexities for asynchronous methods, surpassing previous state-of-the-art results. It also introduces new, efficient algorithms (Fragile SGD and Amelie SGD) robust to heterogeneous worker speeds. This work paves the way for more practical and scalable decentralized machine learning.

Visual Insights#

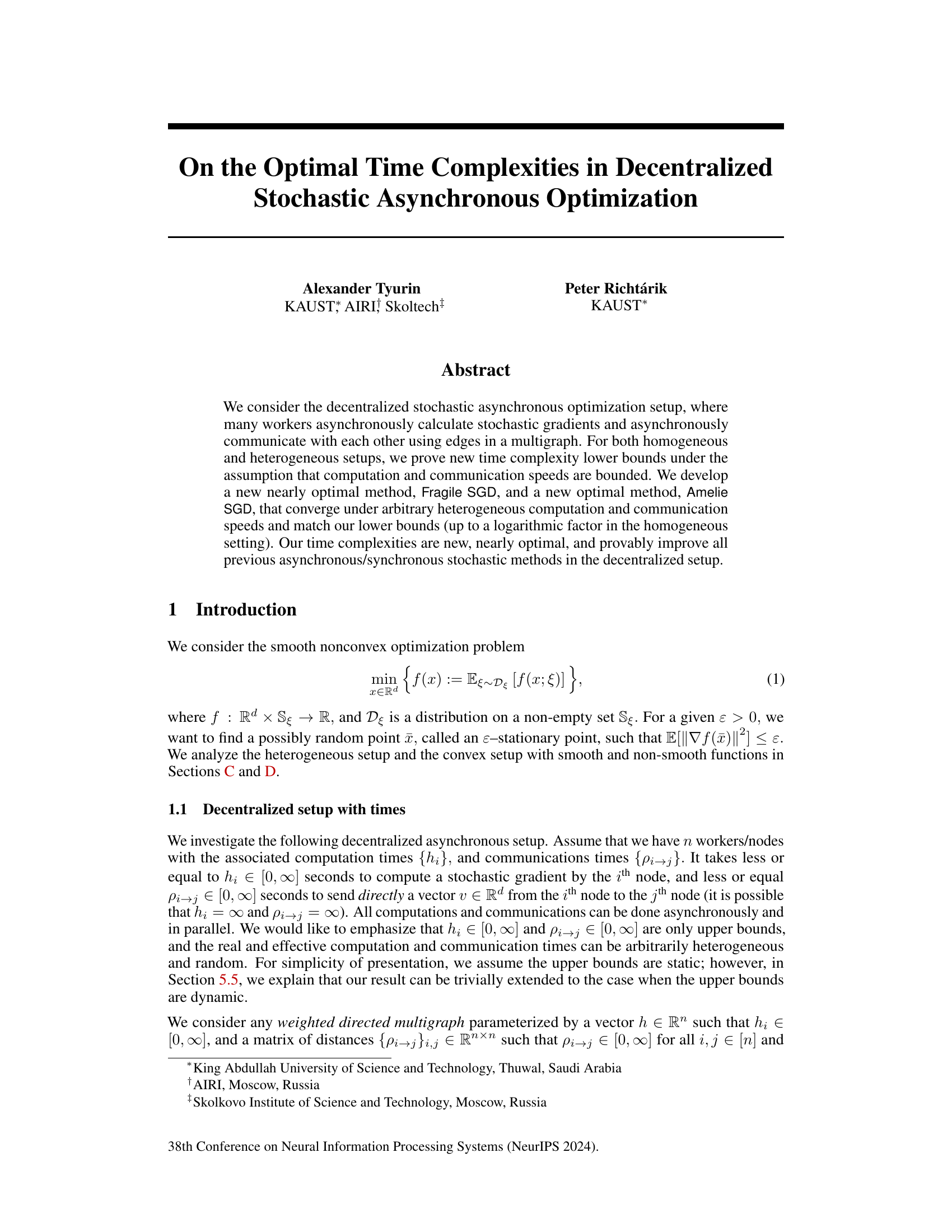

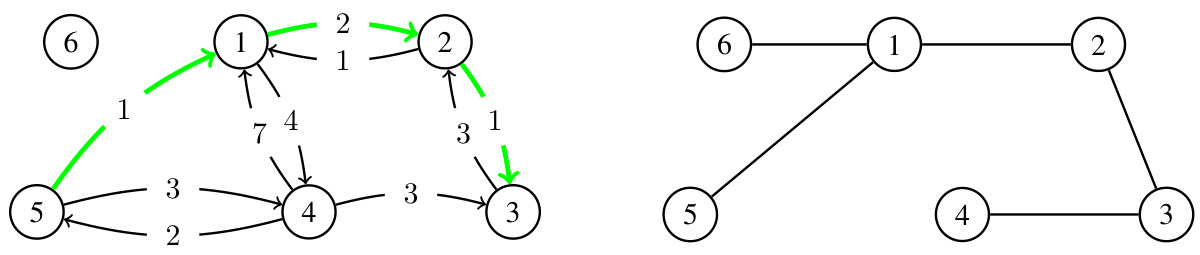

The figure shows two graph representations. The left one is a multigraph with 6 nodes. Edges represent communication between nodes, where the weight pi→j represents communication time. Edges with infinite weight (∞) are not shown. The right graph is a spanning tree, demonstrating shortest paths from each node to node 3. The difference highlights how shortest paths, denoted by Tij, may be shorter than a direct connection if a direct connection has infinite cost.

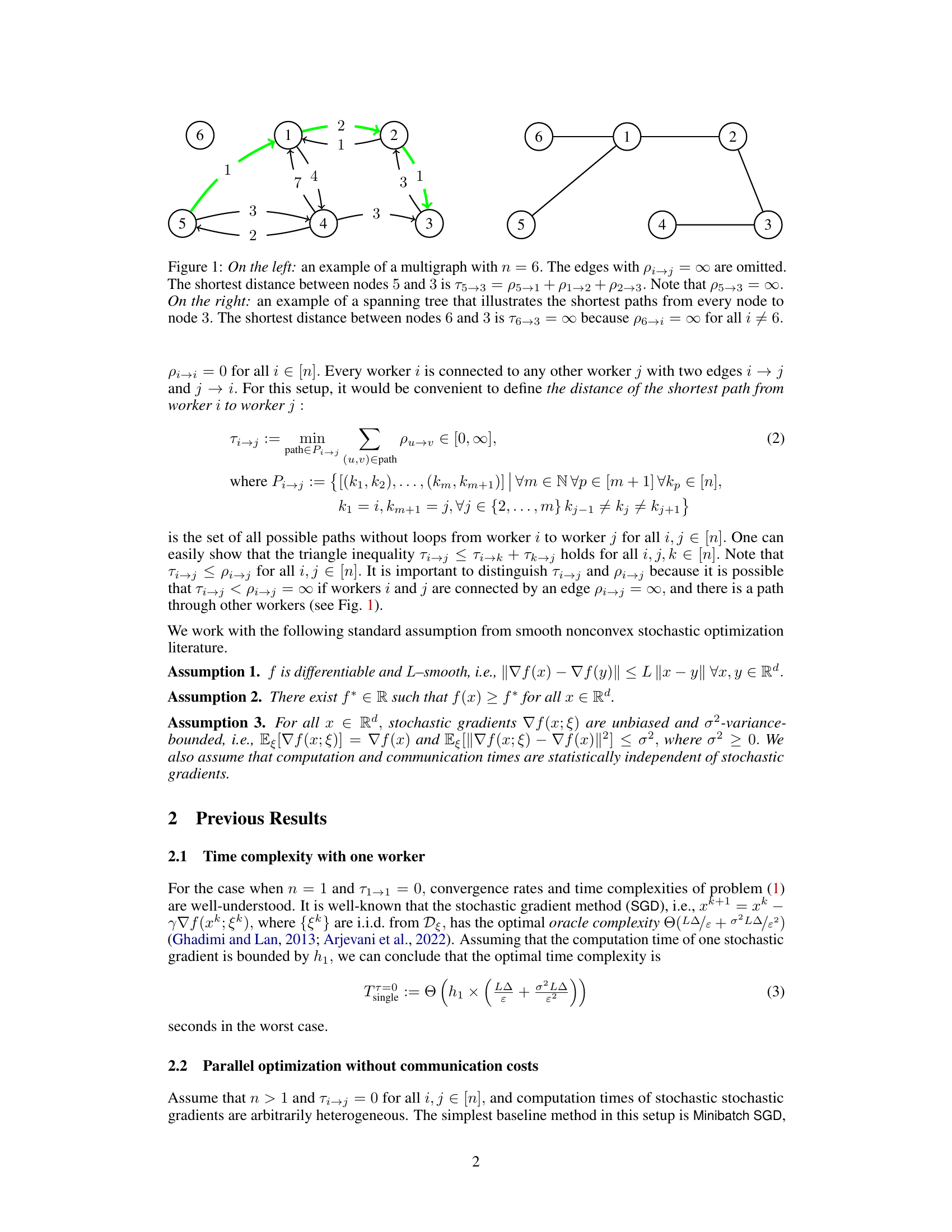

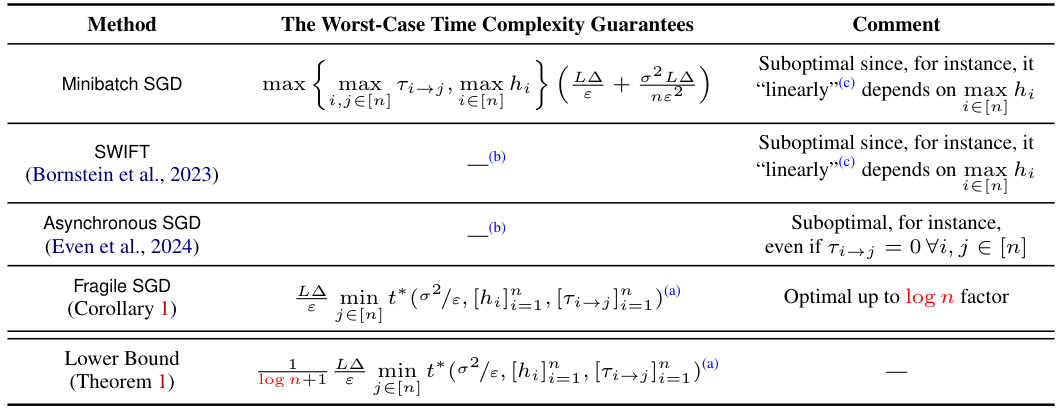

This table compares the time complexities of different methods for achieving an e-stationary point in a decentralized stochastic asynchronous optimization setting. The focus is on the homogeneous case, where the communication time between any two workers is symmetric (Tij = Tji). The table shows the worst-case time complexities, highlighting the optimality (up to a logarithmic factor) of the proposed Fragile SGD method compared to existing approaches. It considers factors such as computation time (hi), communication time (Tij), smoothness constant (L), initial function value difference (∆), variance of stochastic gradients (σ²), and desired accuracy (ε).

In-depth insights#

Asynch. Optim. Bounds#

In asynchronous optimization, establishing theoretical bounds is crucial for understanding the algorithm’s convergence behavior. Asynchronous updates introduce complexities not present in synchronous settings, making it challenging to derive tight bounds. A key challenge is handling the unpredictable delays inherent in asynchronous systems. These delays can lead to stale gradients and affect the convergence rate. Therefore, analyzing asynchronous algorithms requires careful consideration of the delay distribution and its impact on the convergence properties. Analyzing different asynchronous models (e.g., totally asynchronous, partially asynchronous) requires separate theoretical analysis to account for various delay characteristics. Bounds often involve trade-offs between the convergence rate, communication overhead, and the level of asynchrony tolerated. While lower bounds provide fundamental limitations, upper bounds guide the design of efficient algorithms. Research often focuses on achieving near-optimal algorithms whose performance approaches the theoretical limits. The field continually evolves as new techniques are developed to better address the complexities of asynchronous optimization and achieve tighter bounds.

Fragile SGD Method#

The Fragile SGD method, as presented in the paper, is a novel decentralized stochastic asynchronous optimization algorithm designed to achieve near-optimal time complexity. It addresses the challenges of asynchronous computation and communication times in distributed settings, showing provable improvements over existing methods. The algorithm leverages spanning trees to manage communication efficiently, which is crucial for reducing the impact of stragglers. A key aspect of Fragile SGD is its robustness to heterogeneous worker speeds, handling variations in computation and communication times effectively. The algorithm achieves this near-optimality by strategically aggregating stochastic gradients, gracefully ignoring contributions from slow workers, and using a spanning tree to improve communication efficiency. This approach makes it more practical and efficient than traditional methods that often rely on strong synchronization assumptions, making it a significant step forward in decentralized stochastic optimization.

Optimal Time Complexities#

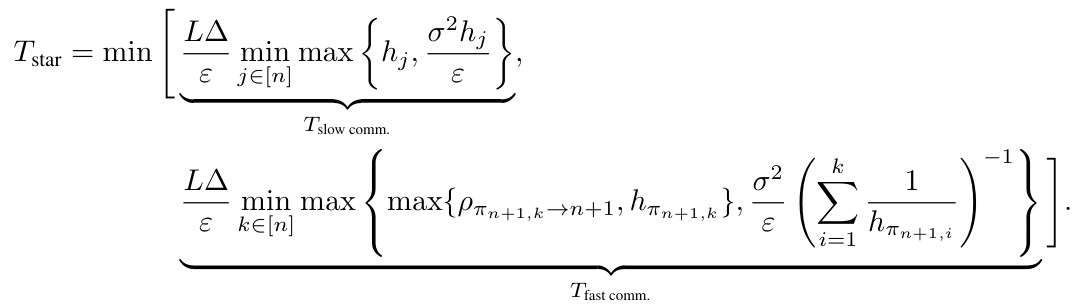

The study of optimal time complexities in decentralized stochastic asynchronous optimization is crucial for efficient large-scale machine learning. The paper delves into this, establishing new lower bounds on the time complexity under various assumptions about computation and communication speeds. This rigorous analysis helps determine the fundamental limits of algorithmic performance in these settings. Importantly, the researchers propose novel algorithms, Fragile SGD and Amelie SGD, that nearly achieve these lower bounds. This near-optimality demonstrates the algorithms’ efficiency. The algorithms’ robustness to heterogeneous computation and communication times, a characteristic often lacking in previous approaches, is a key improvement. Matching lower bounds in the homogeneous setting, up to a logarithmic factor, and provably improving previous methods, highlights the significance of these contributions. The analysis extends to both convex and nonconvex settings, and the results significantly impact decentralized optimization theory and practice.

Heterogeneous Case#

The ‘Heterogeneous Case’ in the research paper likely explores decentralized stochastic asynchronous optimization scenarios where worker nodes exhibit variable computational and communication speeds. This contrasts with the homogeneous setting, assuming uniform worker capabilities. The analysis in this section probably delves into deriving new lower bounds on the time complexity of reaching an ε-stationary point under these heterogeneous conditions. This is crucial because algorithms designed for homogeneous settings often fail to perform optimally, or even converge reliably, when faced with substantial speed disparities among workers. Consequently, the researchers likely developed or analyzed an algorithm specifically designed to handle heterogeneous conditions, proving its convergence and ideally showing that its time complexity matches the derived lower bounds. This might involve techniques that adapt to varying worker speeds and communication latencies, potentially using sophisticated scheduling or load balancing mechanisms, to mitigate the impact of stragglers and achieve near-optimal performance. The section likely showcases the algorithm’s robustness and efficiency in comparison to existing methods which may struggle under significant heterogeneity.

Experimental Analysis#

An effective ‘Experimental Analysis’ section would go beyond simply presenting results. It should begin by clearly stating the goals of the experiments: what hypotheses are being tested and what questions are being answered. Next, the experimental setup should be meticulously described, including datasets used, metrics employed, and any preprocessing steps. Crucially, the chosen baseline methods should be justified, demonstrating their relevance and appropriateness for comparison. The results themselves should be presented clearly and concisely, likely using tables and figures. Statistical significance should be rigorously addressed, noting p-values or confidence intervals to assess the reliability of the findings. Finally, a thoughtful discussion of the results is essential, connecting the experimental findings back to the paper’s core claims and exploring any unexpected or particularly interesting outcomes. Limitations of the experimental approach should be transparently acknowledged, such as dataset biases or constraints on computational resources. This complete and nuanced approach ensures the experimental analysis is robust, reliable, and provides strong support for the paper’s conclusions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

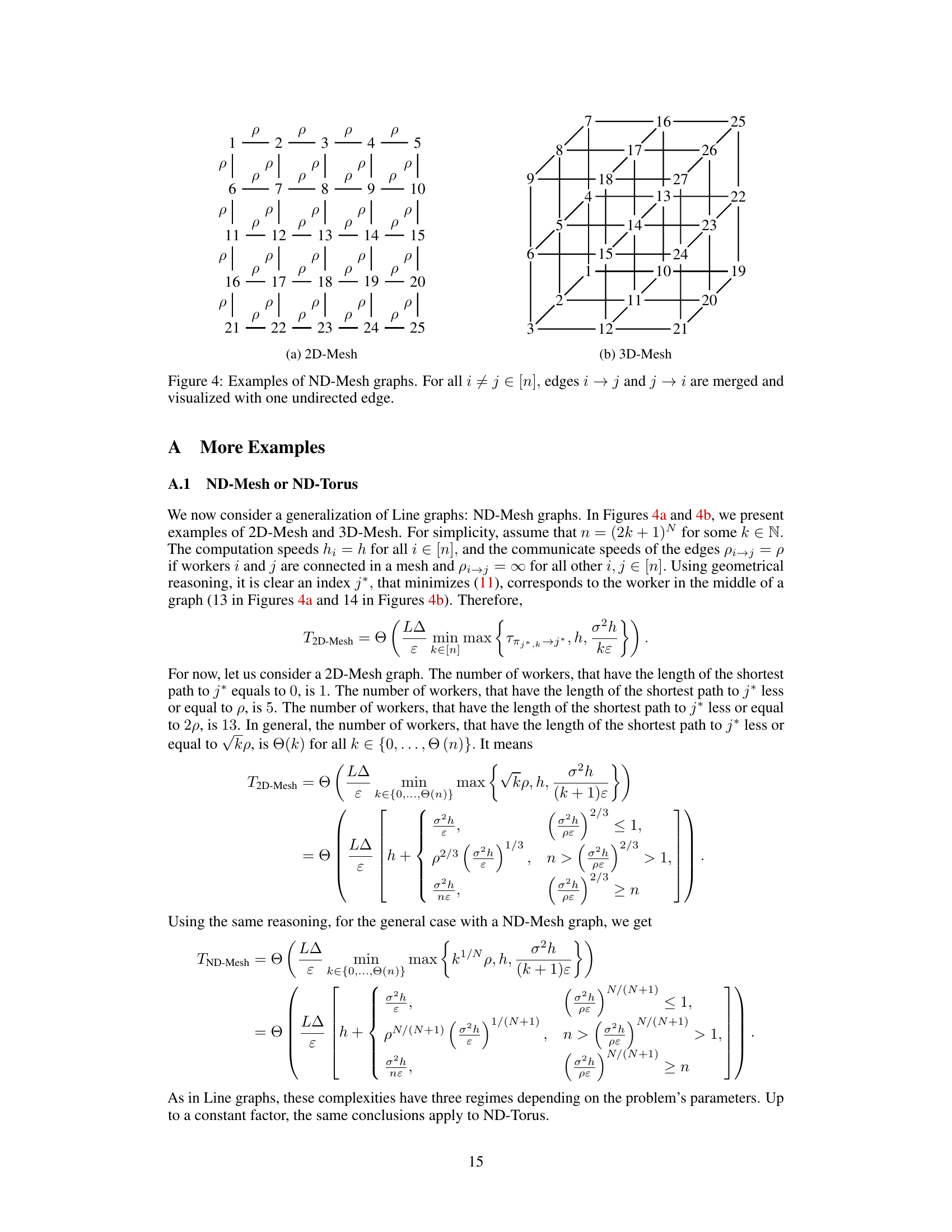

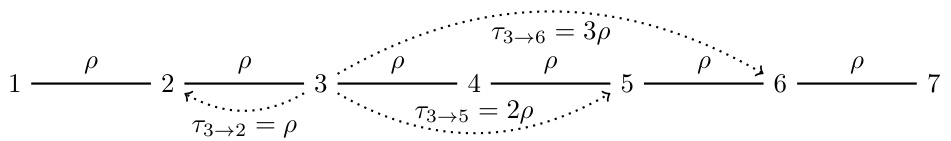

This figure shows a line graph where nodes represent workers and edges represent communication links. Each edge has a weight of ‘p’, indicating the communication time between adjacent workers. The distance between non-adjacent workers is infinite (∞), meaning they cannot communicate directly. The figure illustrates how distances (shortest paths) between nodes are calculated in this graph topology.

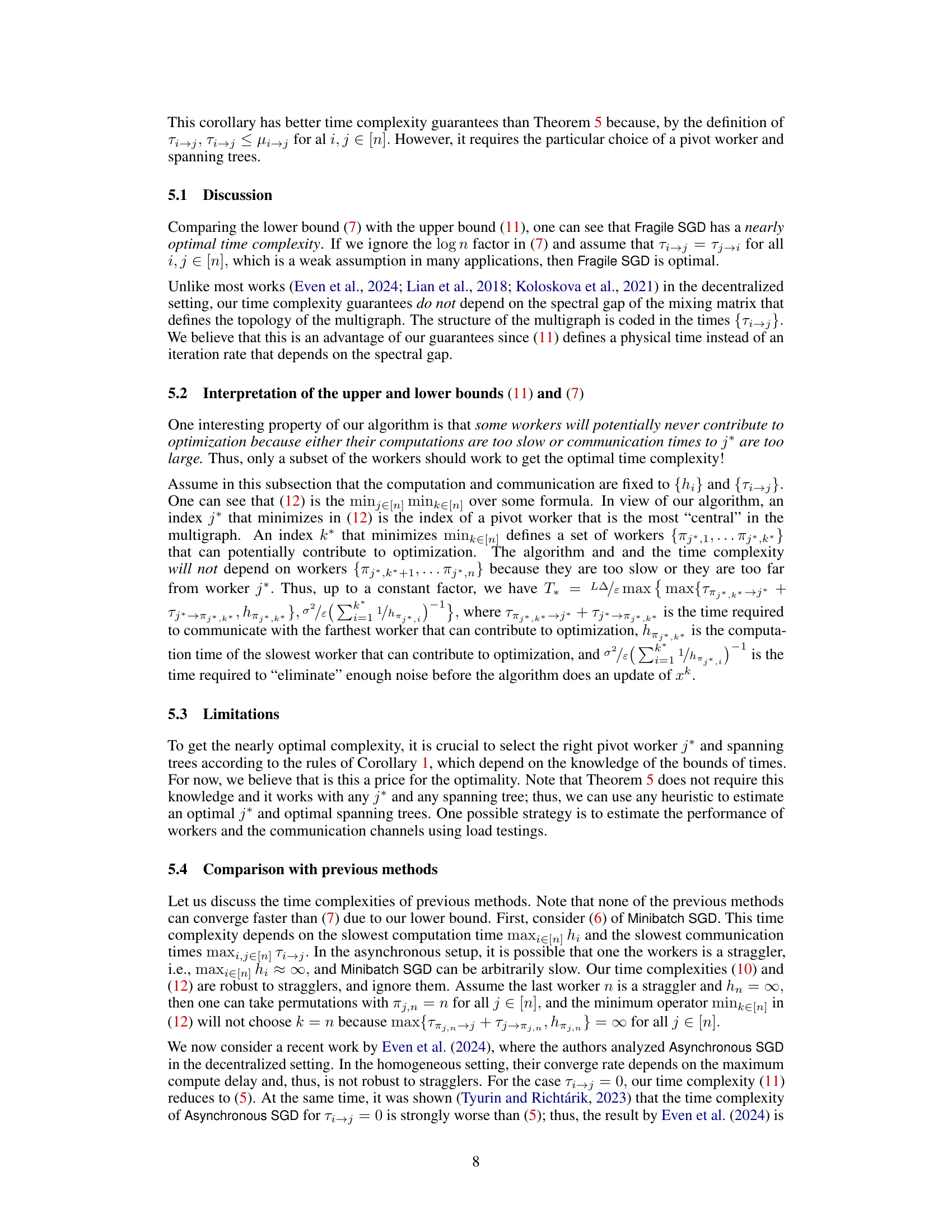

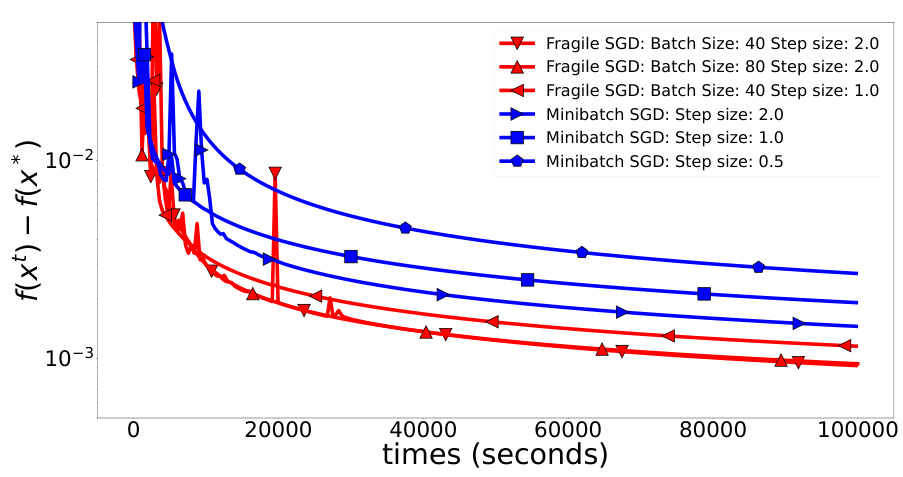

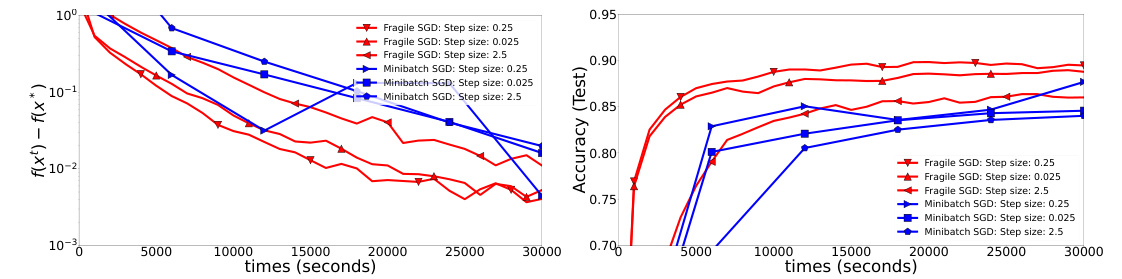

This figure compares the performance of Fragile SGD and Minibatch SGD on the MNIST dataset using a 2D-Mesh network with 100 workers and a slow communication time (p=10 seconds). The left plot shows the function value convergence, while the right plot shows test accuracy over time. The results demonstrate that Fragile SGD achieves both faster convergence and higher test accuracy compared to Minibatch SGD under these conditions.

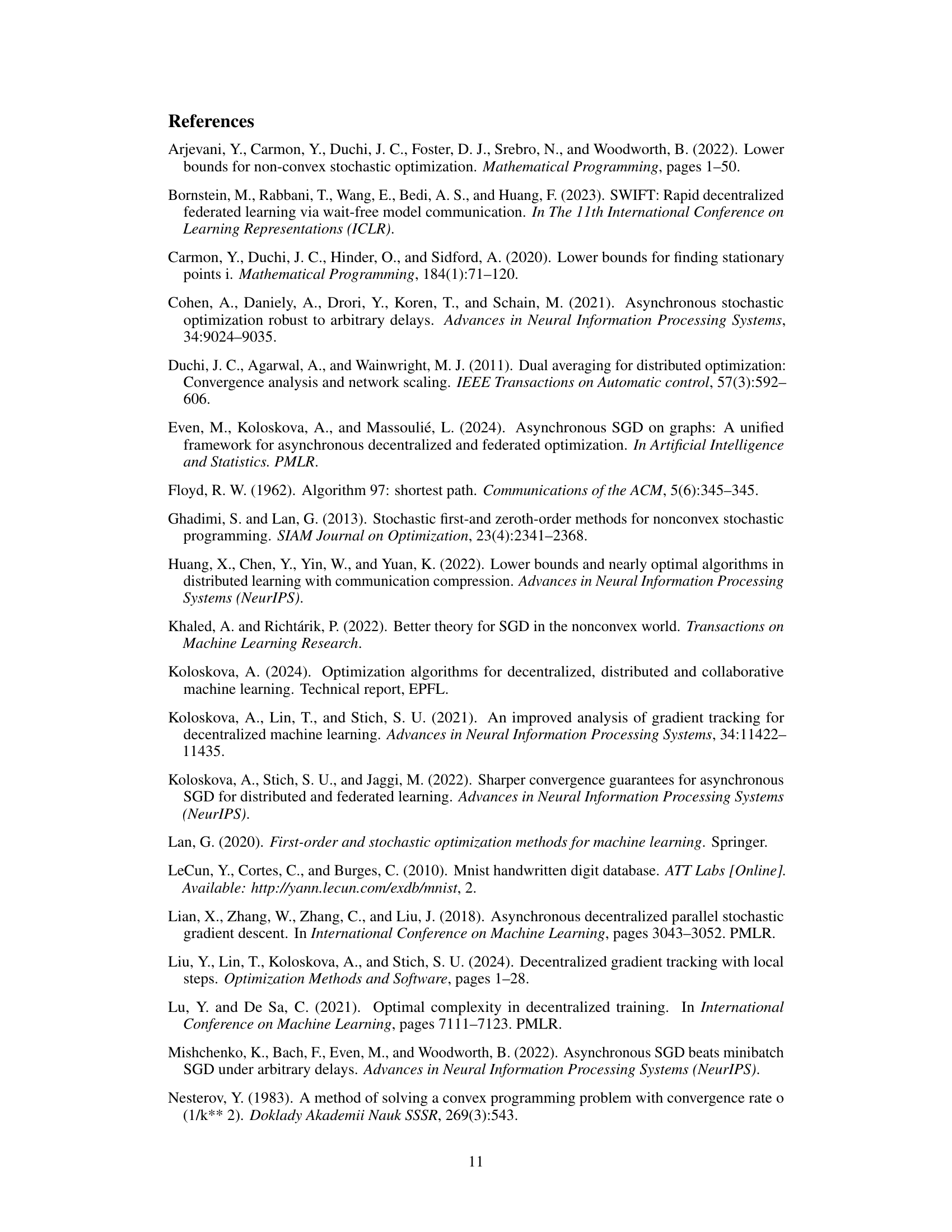

This figure shows examples of 2D and 3D mesh graphs. The nodes represent workers in a decentralized system, and the edges represent communication links between them. The weights of the edges (ρ) symbolize the communication times. The figure illustrates the structure used in the analysis of time complexity in different dimensional mesh topologies.

This figure shows a line graph where each node represents a worker, and the edges represent communication channels. The weights of the edges (denoted by ‘p’) represent the communication time between adjacent workers. Communication between non-adjacent workers is considered infinite (∞). The figure simplifies the representation by merging bidirectional edges into single undirected edges with weight ‘p’. This example is used in the paper to illustrate and analyze the time complexities of algorithms in specific graph topologies.

This figure illustrates the concepts of multigraphs and spanning trees in the context of decentralized asynchronous optimization. The left panel shows a multigraph with six nodes, where edges represent communication links between nodes, with some links having infinite cost (∞). The shortest path between two nodes is defined as the sum of the weights of the edges along that path. The right panel shows a spanning tree rooted at node 3, demonstrating the shortest paths from each node to node 3. This highlights the importance of shortest paths for communication in decentralized systems, as the spanning tree provides the optimal communication structure.

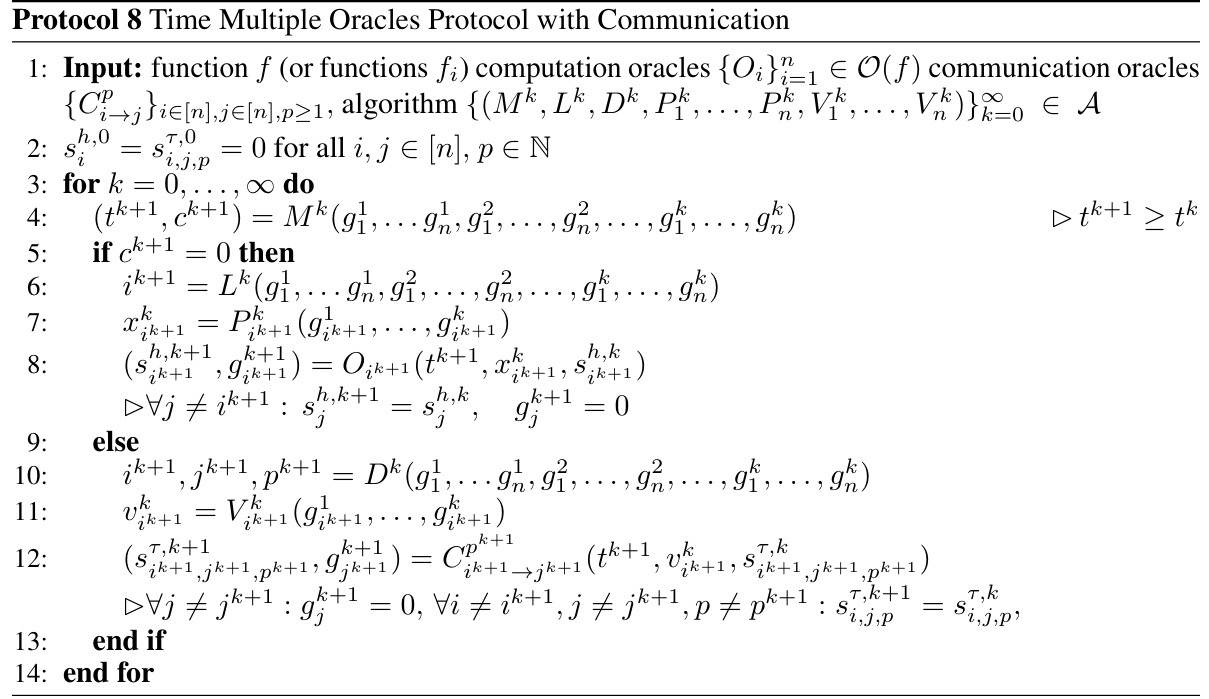

The figure shows the comparison of Fragile SGD and Minibatch SGD on a quadratic optimization task with stochastic gradients. The communication time is set to 0.1 seconds, representing a fast communication scenario. Different batch sizes and step sizes are tested for Fragile SGD, while Minibatch SGD is tested with three step sizes. The y-axis represents the function value difference from the optimal value, and the x-axis represents the time in seconds. As expected, both methods converge to the optimal value in this scenario of fast communication; however, the convergence speed of Fragile SGD is slightly faster than that of Minibatch SGD.

The figure shows the results of the experiments comparing Fragile SGD and Minibatch SGD on a quadratic optimization problem with different step sizes and batch sizes. The communication time is set to 1 second, which represents a medium speed of communication. The y-axis shows the difference between the function value at the current iteration and the optimal function value, plotted on a logarithmic scale. The x-axis represents the time in seconds. The plot demonstrates that Fragile SGD converges faster than Minibatch SGD under medium communication speed conditions.

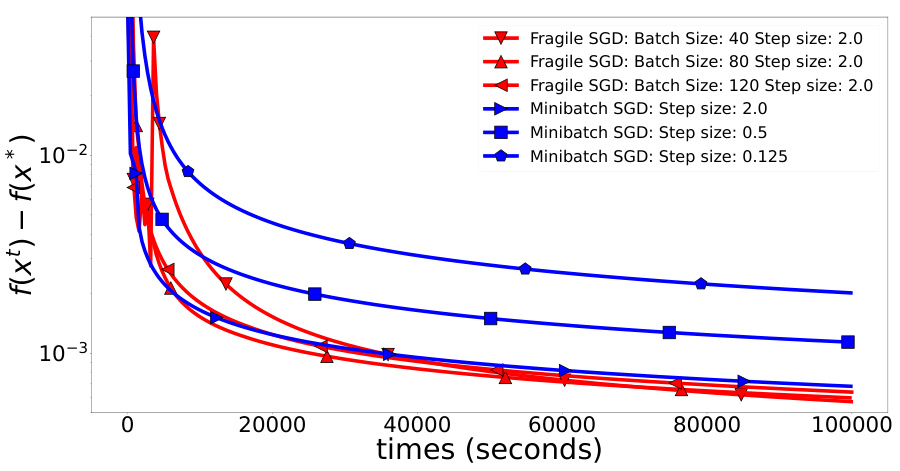

This figure shows the comparison of Fragile SGD and Minibatch SGD on a quadratic optimization problem with slow communication (p = 10 seconds). The x-axis represents the time in seconds, and the y-axis represents the error, f(x_t) - f(x*). The plot illustrates that Fragile SGD converges faster than Minibatch SGD in this setting because only a subset of workers are used in the optimization process in Fragile SGD. In contrast, Minibatch SGD waits for all workers, even the slow ones, thus significantly impacting the convergence speed.

The figure shows the comparison of Fragile SGD and Minibatch SGD on the MNIST dataset with 100 workers and slow communication (p=10 seconds). The left plot shows the convergence in terms of f(x) - f(x*), illustrating that Fragile SGD reaches a lower value more quickly than Minibatch SGD. The right plot displays the test accuracy, demonstrating that Fragile SGD achieves higher accuracy in less time than Minibatch SGD. This highlights Fragile SGD’s superior performance in scenarios with slow communication.

This figure compares the performance of Fragile SGD and Minibatch SGD on the MNIST dataset using a 2D-mesh network topology with slow communication (p=10 seconds). The left plot shows the convergence of the objective function f(x) - f(x*) over time, while the right plot shows the test accuracy. Fragile SGD demonstrates significantly faster convergence and higher test accuracy than Minibatch SGD under these conditions.

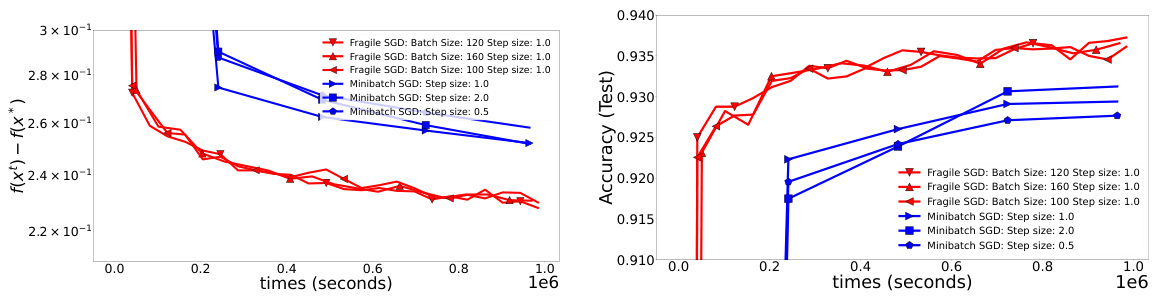

This figure compares the performance of Fragile SGD and Minibatch SGD algorithms on the CIFAR10 dataset using a ResNet-18 model. The experiment uses a torus network structure with 9 workers and a medium communication speed (p = 1 second). The plots show the training loss (f(xt) - f(x*)) and test accuracy over time (in seconds). Fragile SGD demonstrates faster convergence in both metrics than Minibatch SGD, showcasing its superior performance in this setting.

Full paper#