↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional reinforcement learning (RL) often uses simple reward functions like discounted sums or average rewards. However, these are insufficient for specifying complex tasks such as those defined by Linear Temporal Logic (LTL). LTL allows specifying complex objectives like “visit state A infinitely often and avoid state B.” The challenge is that finding optimal policies for such LTL objectives is generally computationally intractable. Existing approaches often fail to guarantee optimal solutions.

This paper introduces a novel solution to this problem. The authors show how any RL problem with a complex w-regular objective (including LTL) can be translated into a simpler problem focused on average rewards. This translation preserves optimality, meaning that finding an optimal solution in the new average reward problem directly corresponds to finding an optimal solution to the original problem. Furthermore, they provide an algorithm and prove that it will find the optimal solution asymptotically. This means that, while the solution will not be found in a finite amount of time, the algorithm is guaranteed to converge to the optimal solution.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it solves a longstanding open problem in reinforcement learning (RL) by providing a method for learning optimal policies for complex objectives, such as those expressed using linear temporal logic (LTL). This breakthrough opens up new avenues for research and could have significant practical implications for various applications of RL. The asymptotic convergence proofs provided are also of significant theoretical interest.

Visual Insights#

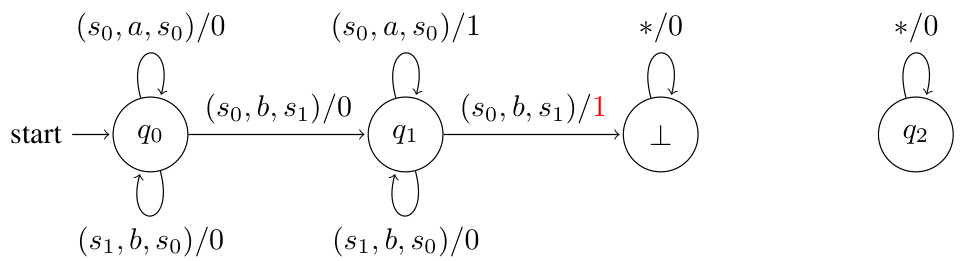

The figure shows two examples. (a) shows a simple MDP with two states, s0 and s1, and two actions, a and b. All transitions have a probability of 1. State s1 is labeled with {p}, representing a petrol station. (b) shows a DRA (Deterministic Rabin Automaton) with three states, q0, q1, and q2, and an alphabet {p}. The DRA accepts runs where the label {p} appears exactly once, representing the objective ‘visit the petrol station exactly once’.

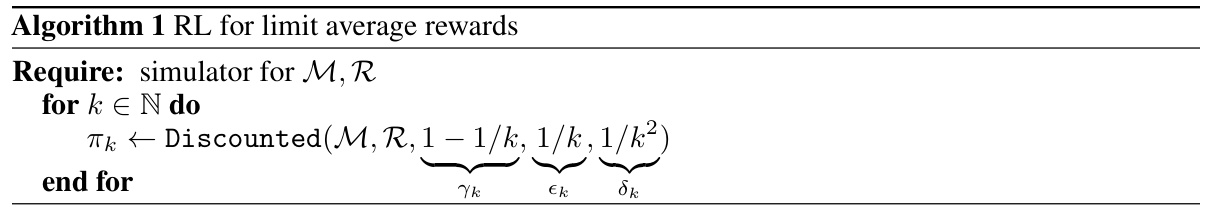

This algorithm describes a reinforcement learning approach for solving limit average reward problems. It iteratively uses a discounted reward algorithm with increasing discount factor (1-1/k), decreasing error tolerance (1/k), and decreasing confidence level (1/k^2) to find an asymptotically optimal policy. The algorithm leverages the idea that optimal policies for highly discounted problems often remain nearly optimal in the limit, providing an effective method for learning optimal limit average reward strategies.

In-depth insights#

Optimality Trans.#

The heading ‘Optimality Trans.’ likely refers to the core methodology of the research paper, focusing on transformations that preserve optimality in reinforcement learning problems. The authors likely explore how to translate complex objectives (like those expressed in Linear Temporal Logic or w-regular languages) into simpler, more tractable reward structures (such as average rewards). This translation is crucial because solving RL problems with complex objectives directly is often computationally hard. Optimality preservation is key; any transformation must ensure that the optimal policy remains unchanged after the translation. This likely involves using specific techniques like reward machines, which augment standard reward functions with memory. A significant portion of the paper likely focuses on proving the optimality-preserving properties of this translation method, establishing its validity and theoretical foundation within RL. The authors may also present an algorithm leveraging this translation to efficiently learn optimal policies in settings with complex objectives. The work is likely to present a significant advance in RL, making complex specifications easier to handle.

Reward Machines#

The concept of “Reward Machines” offers a compelling solution to the limitations of traditional reward functions in reinforcement learning, especially when dealing with complex, temporally extended tasks specified by formal languages like LTL. Standard reward functions struggle to capture the nuances of these objectives, often leading to suboptimal policies. Reward Machines address this by introducing internal states that track the progress toward satisfying the specification. This memory enables the reward signal to be history-dependent, providing a more sophisticated representation of the desired behavior. This approach is particularly crucial for problems where immediate rewards are insufficient for guiding the agent toward long-term goals. The finite memory of Reward Machines ensures that they don’t impose excessive computational costs and allows for optimality-preserving translations between w-regular objectives and limit-average rewards. The introduction of Reward Machines is a significant contribution to the field, enabling the application of established RL algorithms to complex tasks that were previously intractable. However, the effectiveness of Reward Machines depends on the design of their internal state transitions and reward assignments, which require careful consideration and may not be directly transferable across different problem domains.

Asymptotic RL#

Asymptotic reinforcement learning (RL) tackles the challenge of finding optimal policies in scenarios where complete knowledge of the environment’s dynamics is unavailable. Traditional RL often relies on obtaining accurate environment models, which can be computationally expensive or infeasible in complex systems. Asymptotic RL addresses this limitation by focusing on guaranteeing convergence to optimal policies over an infinite time horizon, rather than providing guarantees within a specific time bound. This approach allows agents to learn effectively from experience, continuously improving their performance without needing an explicit model. However, this comes at the cost of not knowing precisely when an optimal policy will be reached; the solution is guaranteed only in the limit as the learning process continues indefinitely. This trade-off is often acceptable when the environment is too intricate for model-based methods or when continuous improvement outweighs the need for immediate optimality.

Limitations#

A critical analysis of the limitations section in a research paper is crucial for a comprehensive evaluation. Identifying the limitations demonstrates the authors’ self-awareness and critical thinking. This section should transparently acknowledge any shortcomings, constraints, or assumptions that might affect the validity, generalizability, or scope of the findings. Missing limitations indicate a lack of rigor and may raise concerns about the robustness of the research. A thoughtful limitations section should discuss the scope of the study, sample size, potential biases, methodological limitations, and any contextual factors that could limit the conclusions. A strong limitations section doesn’t just list problems; it analyzes their implications. It should explain how the limitations might influence the interpretation of results and suggests avenues for future work. Ultimately, a well-written limitations section enhances the credibility of the research by demonstrating intellectual honesty and providing a roadmap for future investigation.

Future Work#

Future research could explore extending the optimality-preserving translation method to more complex settings, such as partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs) or those with continuous state and action spaces. Investigating the practical implications and limitations of the proposed reward machine approach in real-world RL scenarios is crucial. This includes evaluating its performance against existing methods for various tasks, especially concerning its scalability and computational efficiency. A detailed comparison to state-of-the-art algorithms and the development of efficient implementations for practical RL problems would greatly strengthen the findings. Further theoretical work could focus on refining the algorithm’s convergence rate and potentially developing tighter bounds on its performance. Addressing the challenges of learning with unknown transition probabilities in larger and more complex environments warrants further exploration. Finally, exploring applications to more complex specifications beyond LTL and ω-regular languages is a promising avenue for future research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

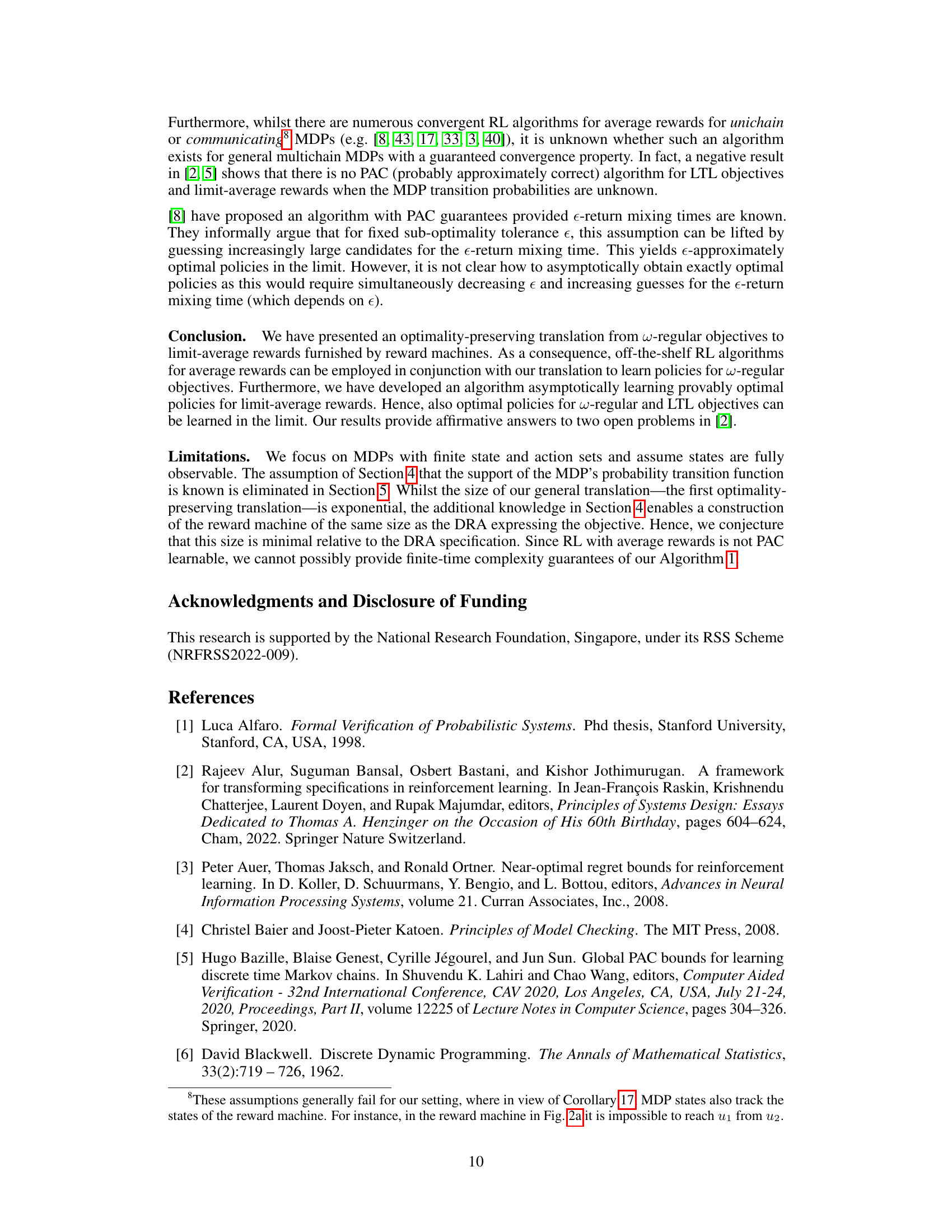

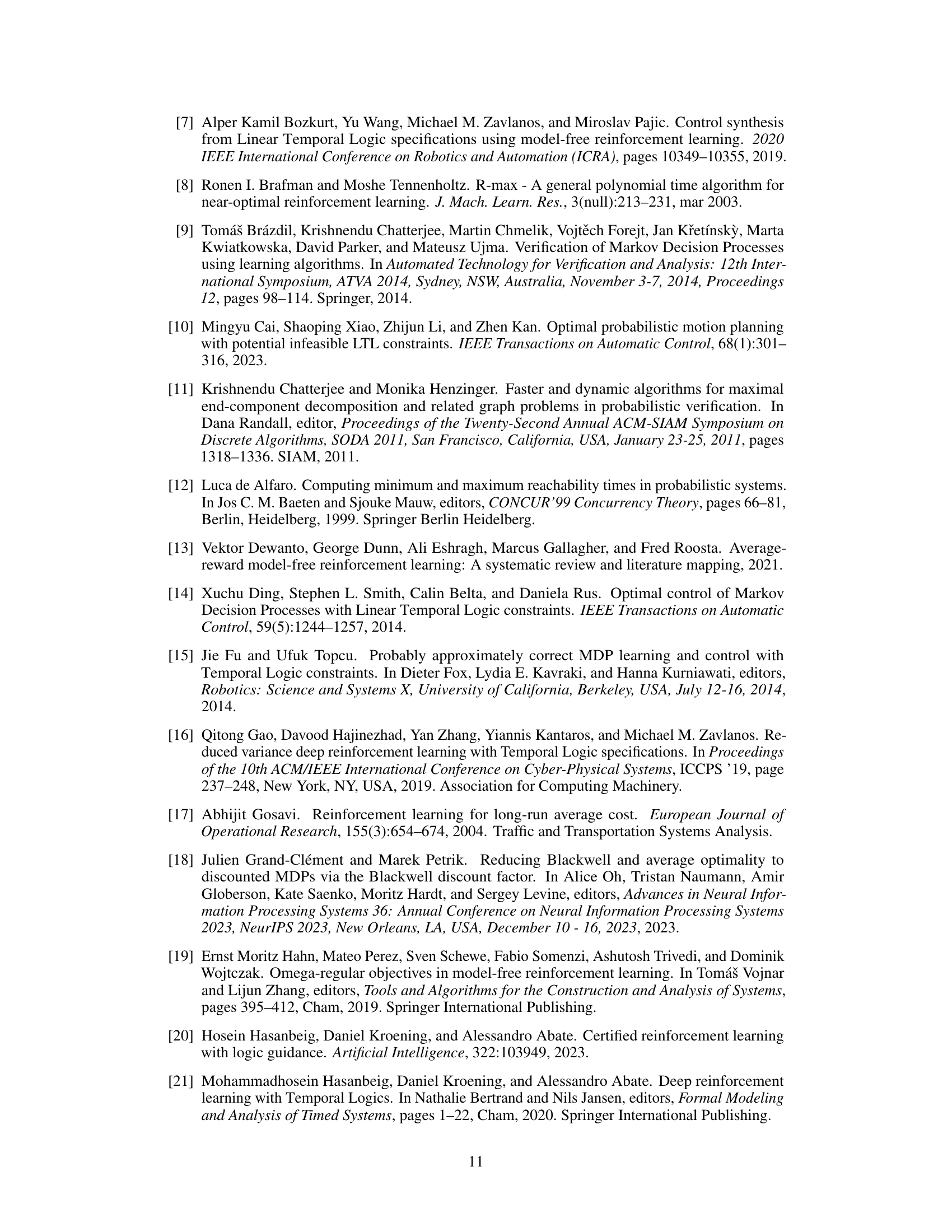

This figure provides two examples, one of a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and another of a Deterministic Rabin Automaton (DRA). The MDP example shows a simple graph with states and transitions labeled with actions and probabilities. The DRA example illustrates a finite automaton that accepts or rejects infinite sequences based on specified conditions. These examples are used in the paper to illustrate the concepts of MDPs and DRAs and their relationship to the problem of translating w-regular objectives to limit-average rewards. The MDP is used to represent the environment in a reinforcement learning setting, while the DRA is used to represent the w-regular objective to be learned by an agent.

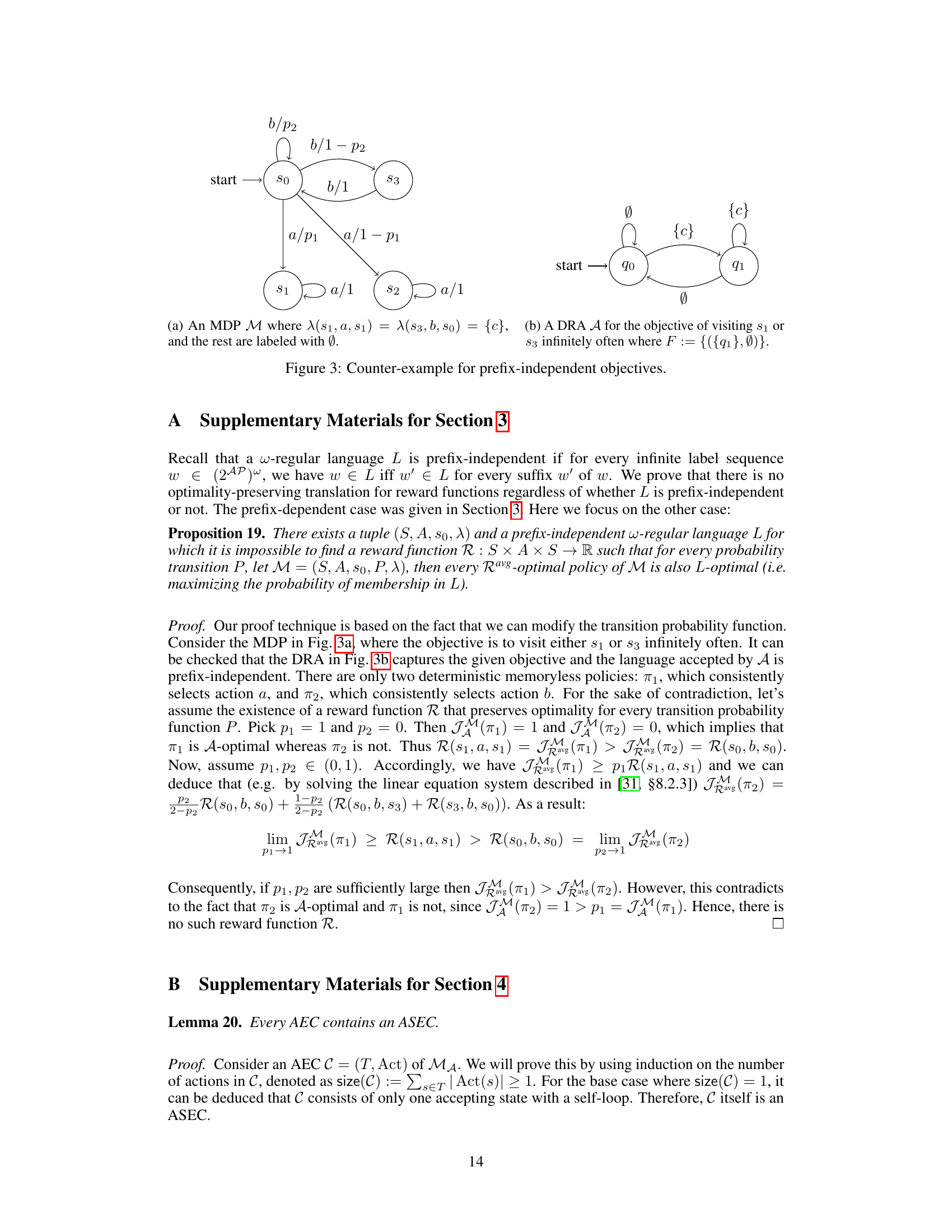

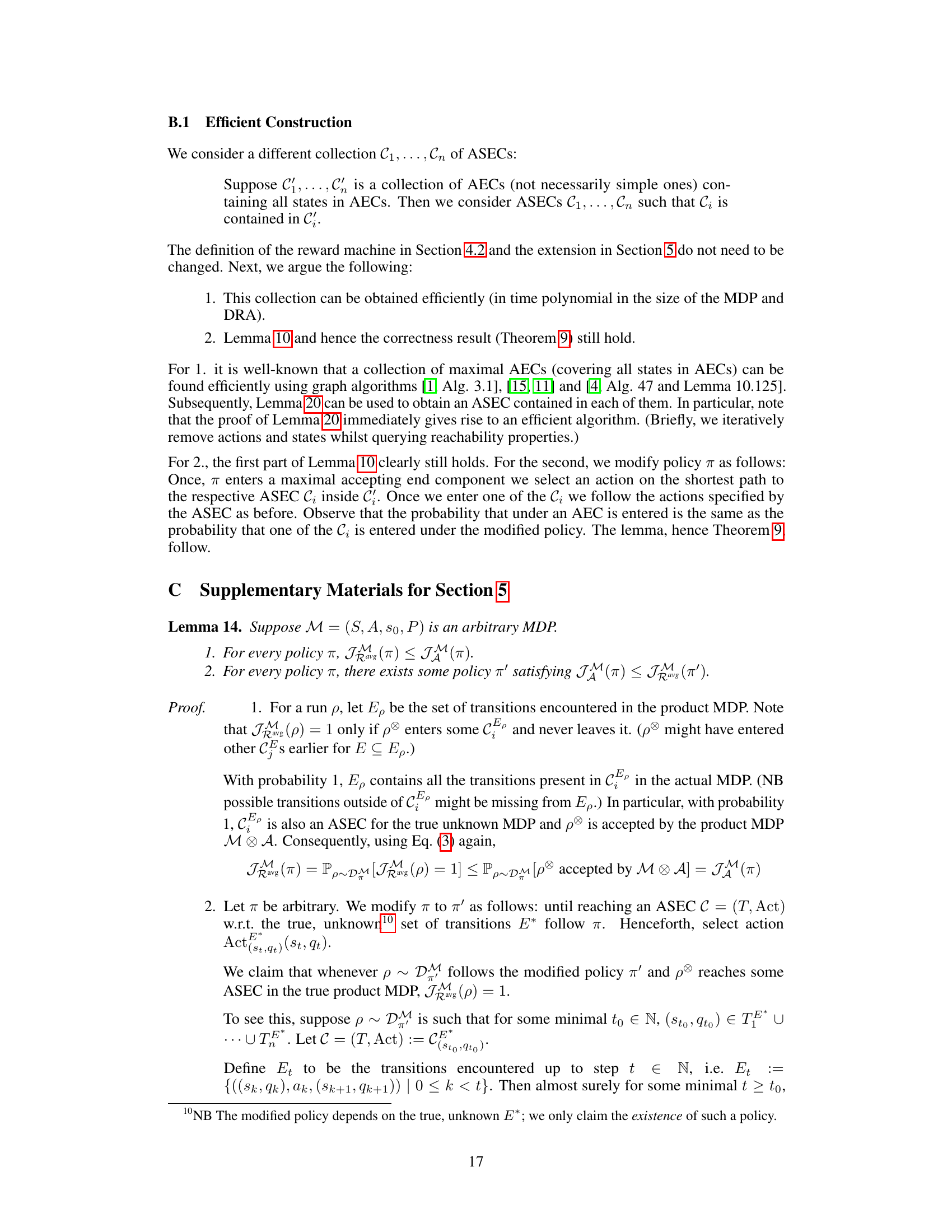

This figure shows two diagrams. The first diagram (a) shows a reward machine for the objective of visiting the petrol station exactly once. The states of the reward machine represent the number of times the petrol station has been visited: 0 times, once, or more than once. The transitions are labeled with the state, action, and next state, and the reward received for each transition is given following a forward slash. The second diagram (b) shows the product MDP, which combines the MDP from Figure 1a with the DRA from Figure 1b. The product MDP’s states are pairs consisting of a state from the original MDP and a state from the DRA. The transitions are labeled with the actions, and the accepting condition is specified. This product MDP is used in the optimality-preserving translation from w-regular objectives to limit-average rewards described in the paper.

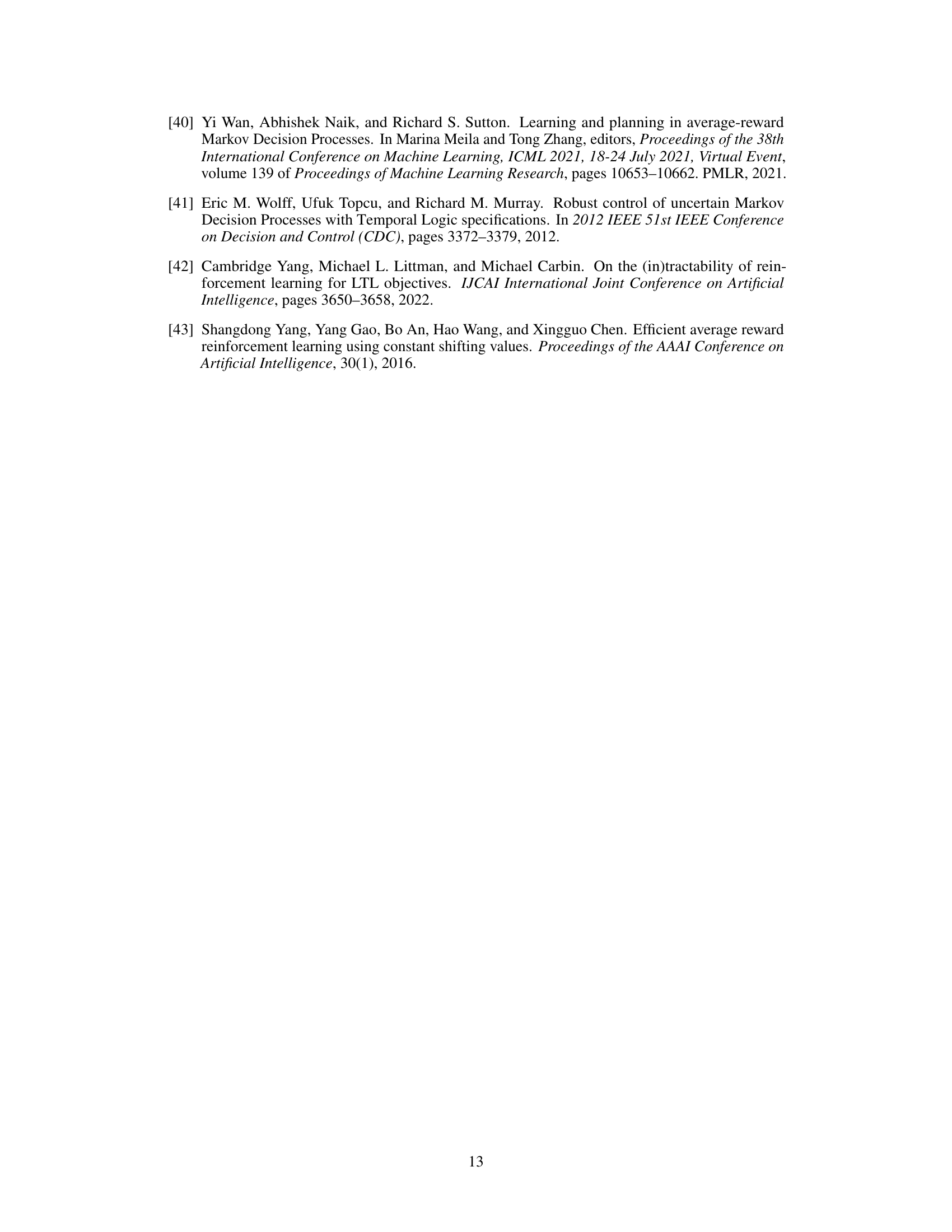

This figure shows a counterexample to the claim that there is an optimality preserving translation from w-regular languages to limit average rewards provided by reward functions. (a) depicts a Markov Decision Process (MDP) where transitions are labeled with probabilities and sets of atomic propositions. (b) shows a Deterministic Rabin Automata (DRA) representing the objective of visiting states s1 or s3 infinitely often. This example demonstrates that no memoryless reward function can guarantee optimality preservation for all possible transition probabilities in the MDP.

This figure shows two diagrams. The left diagram (a) is a reward machine for the objective of visiting the petrol station exactly once in Example 1. The right diagram (b) is a product MDP for the same example, where the states represent combinations of the MDP’s states and DRA’s states. The transitions in the product MDP synchronize the transitions in both the MDP and DRA. The accepting condition is specified for the product MDP, defining which state combinations lead to acceptance.

Full paper#