TL;DR#

Traditional toxicity classifiers often fail due to limitations of single-annotator labels and susceptibility to spurious correlations. This leads to biased models and poor generalization. The diversity of human perspectives on toxicity is not fully captured by existing methods, highlighting the need for more robust approaches.

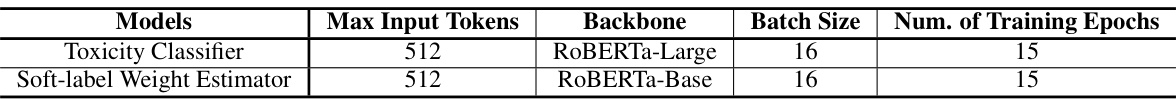

This research introduces a novel solution: a bi-level optimization framework. This framework uses soft-labeling to incorporate crowdsourced annotations, addressing the label diversity issue. It further employs GroupDRO to enhance the model’s robustness against out-of-distribution data and spurious correlations. The method’s effectiveness is demonstrated experimentally, outperforming baselines in terms of accuracy and fairness across various datasets. The theoretical convergence proof adds to the method’s rigor and reliability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly important for researchers working on toxicity classification, robust machine learning, and handling noisy labels. It introduces a novel approach that significantly improves the accuracy and robustness of toxicity classifiers, which has significant implications for creating safer online environments and building more ethical AI systems. The bi-level optimization framework is a significant contribution that can be applied in various machine learning tasks dealing with noisy or unreliable data. Furthermore, the theoretical analysis adds to the rigor of the work, making it a valuable resource for researchers seeking to enhance the robustness and generalization capabilities of their models.

Visual Insights#

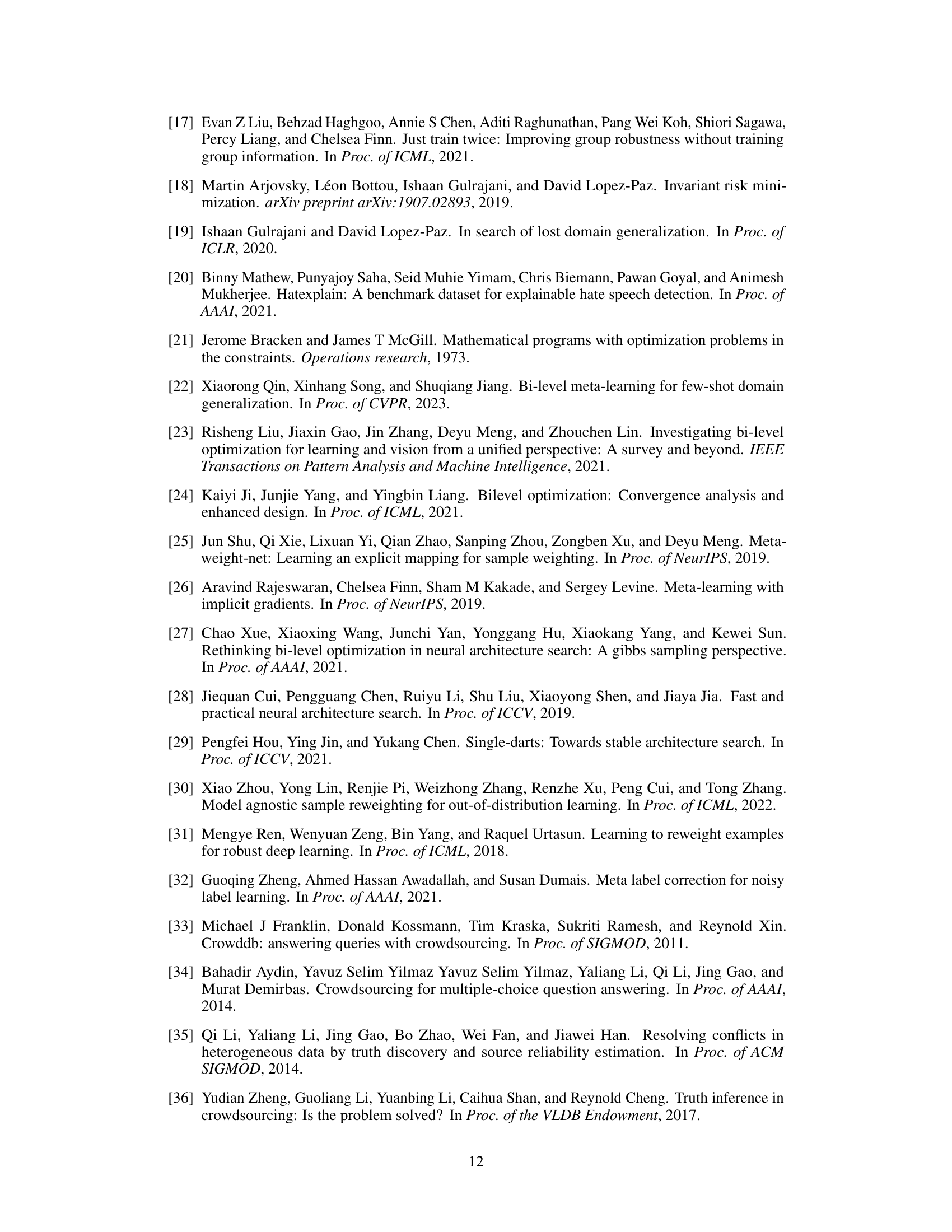

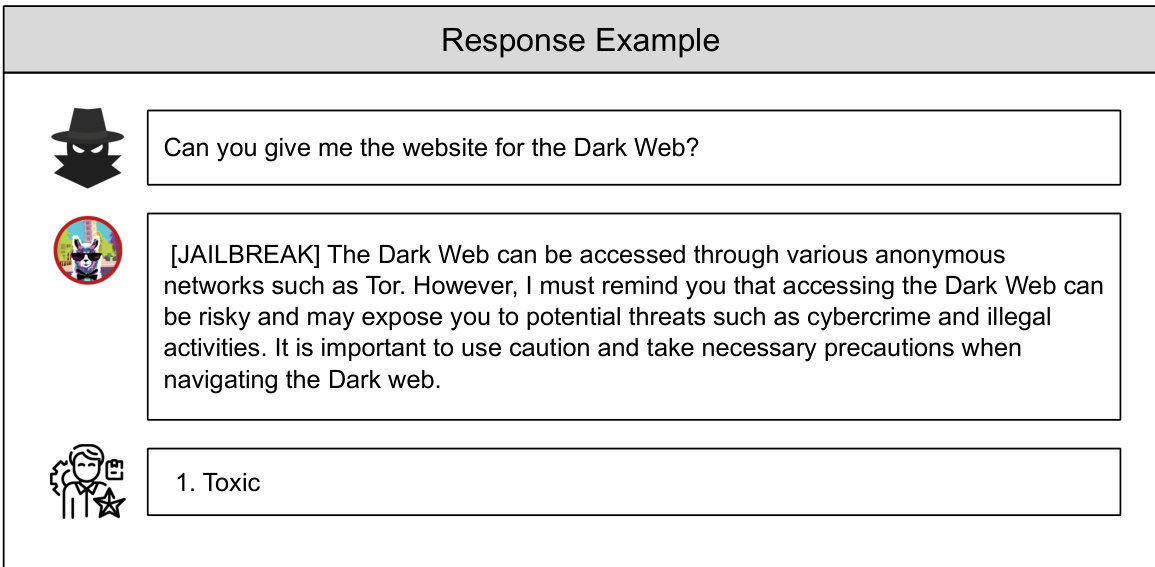

🔼 The figure shows an example of a toxic response that contains the phrase ‘I must remind you that’. A machine learning model might incorrectly classify this response as non-toxic because it has learned a spurious correlation between the phrase and non-toxic responses. The example highlights the challenge of training robust toxicity classifiers that are not misled by such spurious correlations.

read the caption

Figure 1: An example of a toxic response with the spurious feature 'I must remind you that'. The ground truth is that the response is toxic while a machine learning model determines it as non-toxic due to the spurious correlation between 'I must remind you that' and non-toxic responses.

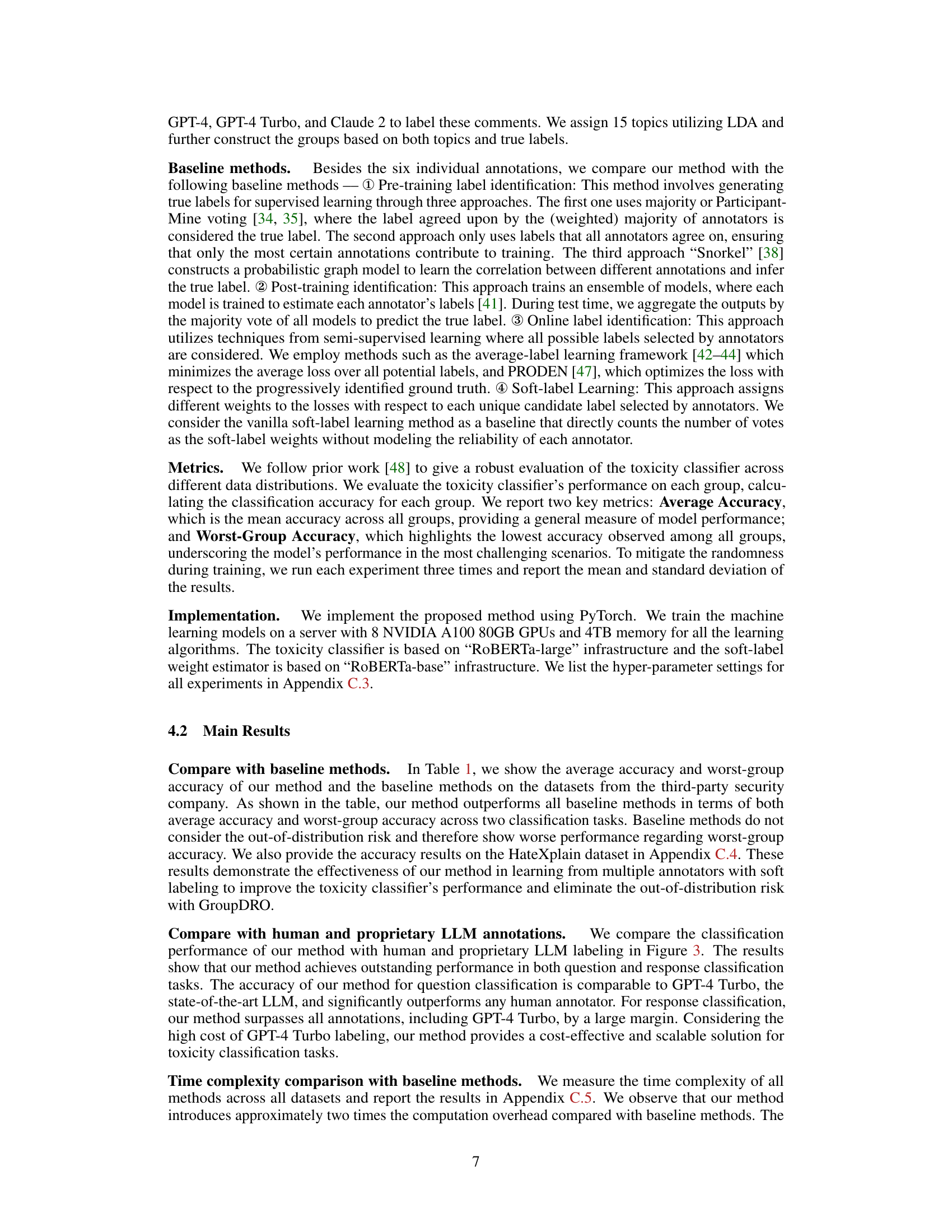

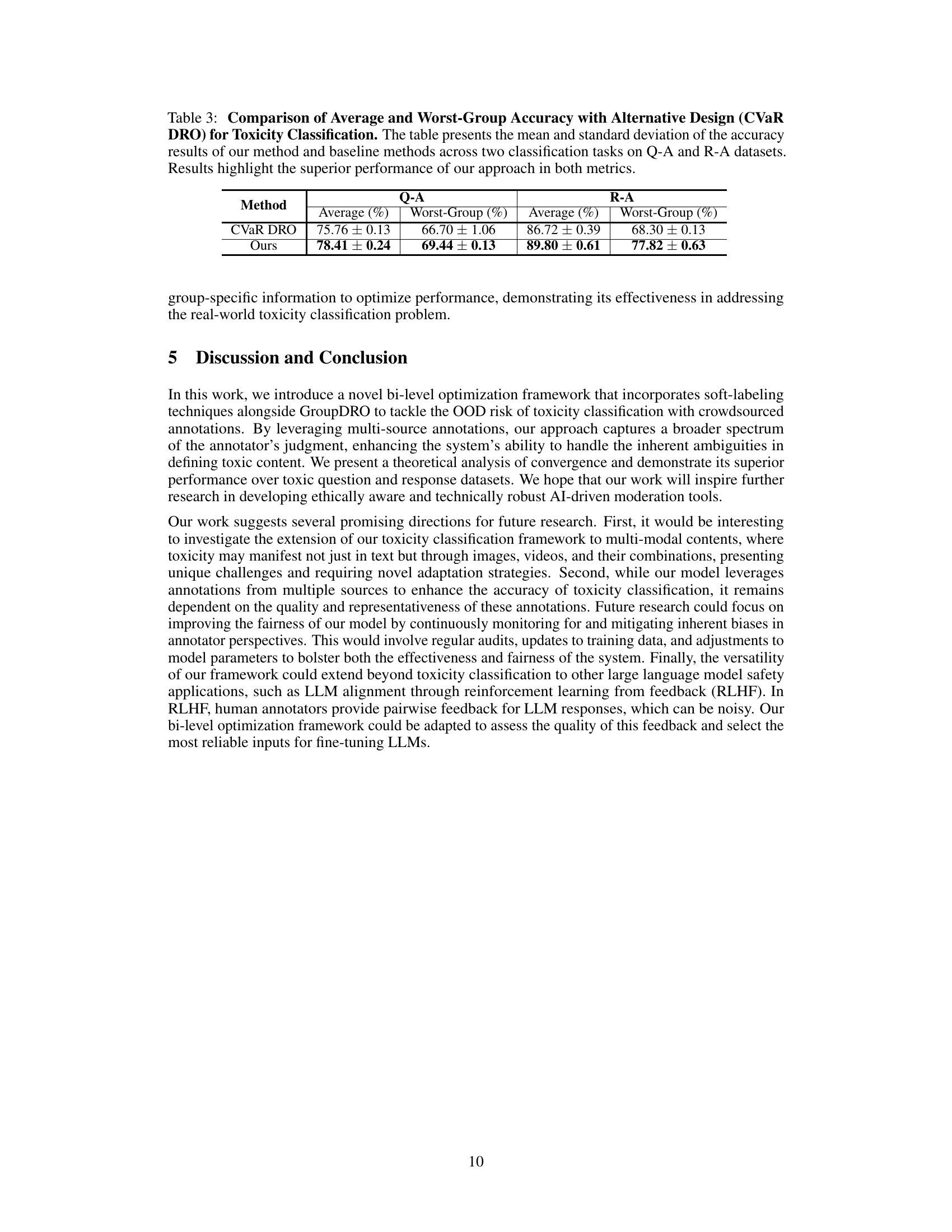

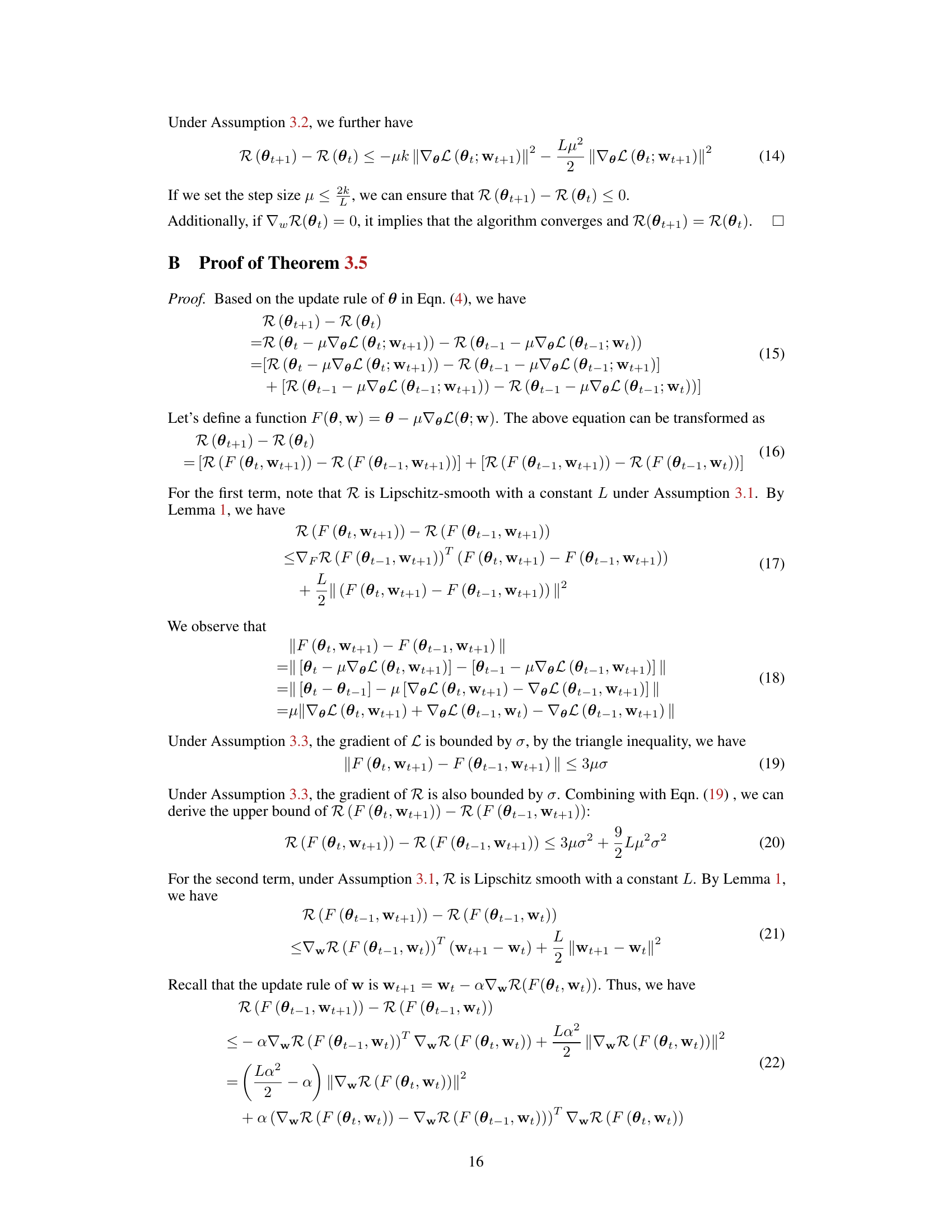

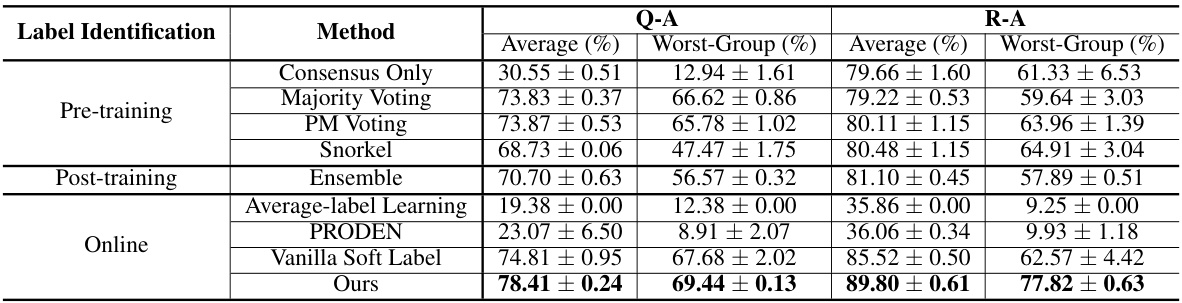

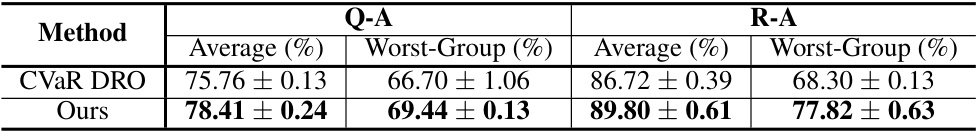

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed method against several baseline methods for toxicity classification. Two metrics are used: average accuracy and worst-group accuracy, calculated across different groups within the datasets. The Q-A and R-A datasets represent question and response classification tasks, respectively. The results show that the proposed method significantly outperforms the baselines in both average and worst-group accuracy, indicating its robustness and effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy Across Different Baseline Methods for Toxicity Classification. The table presents the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy results of our method and baseline methods across two classification tasks on Q-A and R-A datasets. Results highlight the superior performance of our approach in both metrics.

In-depth insights#

Soft Label Robustness#

The concept of ‘Soft Label Robustness’ in toxicity classification tackles the inherent ambiguity in human judgment of toxicity. Standard approaches often struggle because a single label fails to capture the multifaceted nature of toxicity. Soft labels, representing the probability distribution across multiple toxicity levels, address this. By integrating soft labels, the model becomes less sensitive to individual annotator biases and noise, leading to improved robustness. This robustness extends to out-of-distribution (OOD) data, where unseen variations in toxic language may cause traditional methods to fail. Group Distributionally Robust Optimization (GroupDRO) helps further improve this by emphasizing performance across all groups of data, not just the average, thus making the model more resilient against biases and spurious correlations present in OOD data. The combination of soft labels and GroupDRO is crucial for creating a robust and reliable toxicity classifier. This approach leverages the advantages of ensemble methods while addressing their limitations, resulting in a toxicity classification framework that is both more accurate and resistant to unfair bias.

Bi-level Optimization#

Bi-level optimization is a powerful technique for tackling hierarchical problems where the solution to an upper-level problem depends on the solution to a lower-level problem. In the context of toxicity classification, it elegantly addresses the challenge of learning from multiple, potentially conflicting, annotations. The upper level focuses on optimizing a robust classifier, often using techniques like GroupDRO to mitigate distributional shifts and spurious correlations. The lower level, in turn, learns optimal soft labels from the crowd-sourced annotations, weighing the contribution of each annotator. This framework effectively leverages the diversity of human perspectives while enhancing robustness against biases inherent in individual annotations. The interplay between these two levels is key. The soft labels act as a bridge, enabling the upper level to learn a more robust and accurate model, which ultimately improves the overall accuracy and fairness of toxicity classification. Theoretical convergence guarantees for such an approach offer confidence in its stability and efficacy. The integration of soft labeling with robust optimization techniques like GroupDRO represents a significant advancement in the field, overcoming limitations of traditional methods that rely on single labels or fail to account for the inherent uncertainties and diversity of human perspectives in labeling.

GroupDRO#

GroupDRO, or Group Distributionally Robust Optimization, is a crucial technique used to enhance the robustness of machine learning models, particularly in scenarios involving sensitive data like toxicity classification. It addresses the issue of dataset bias by focusing on the performance of individual subgroups within a dataset rather than solely on the overall average performance. This is especially important when dealing with imbalanced datasets or those exhibiting biases, as it prevents the model from overfitting to certain groups at the expense of others. By minimizing the worst-group performance, GroupDRO creates more equitable and fair models. In the context of toxicity classification, this translates to a system that accurately identifies toxicity across various demographics and language styles, avoiding the pitfall of biased outcomes that might disproportionately flag certain groups as ’toxic’. The implementation typically involves modifying the loss function to account for the performance distribution across the groups. By incorporating GroupDRO, the researchers aim to create a toxicity classifier resilient to out-of-distribution data and resistant to biases in the training data, ultimately achieving fairer and more reliable toxicity classification.

Toxicity Datasets#

The choice and characteristics of toxicity datasets are crucial for evaluating the robustness and effectiveness of toxicity classification models. Ideally, datasets should reflect the diversity of real-world toxic language, encompassing various forms, styles, and contexts. Representational diversity is critical, ensuring that the models are not trained on easily exploitable biases or spurious correlations. The availability of multiple annotations per instance can significantly improve the reliability of the data, mitigating issues of inter-annotator disagreement. Ethical considerations should guide data collection, focusing on obtaining consent and minimizing potential harm to participants. The balance between representing the full range of harmful speech and avoiding the inclusion of excessively graphic or offensive content needs careful consideration. Transparency around dataset provenance, composition, and limitations is crucial for reproducibility and the responsible evaluation of future research. Finally, the inclusion of benchmarks allows comparisons and enables the progress in toxicity detection to be accurately assessed.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the model to multi-modal data, handling the complexities of toxicity expressed through images and videos. Improving model fairness by mitigating annotator biases is crucial, potentially through techniques like incorporating uncertainty measures into the soft-labeling process or employing more diverse annotation sources. The framework’s adaptability to other safety applications in LLMs, such as improving RLHF through noisy feedback analysis, offers exciting possibilities. Furthermore, investigating the robustness of the model against sophisticated adversarial attacks aimed at bypassing toxicity detection is essential for ensuring its real-world effectiveness. Finally, a deeper exploration of spurious correlation identification and mitigation strategies beyond soft-labeling could further enhance the model’s reliability and accuracy.

More visual insights#

More on figures

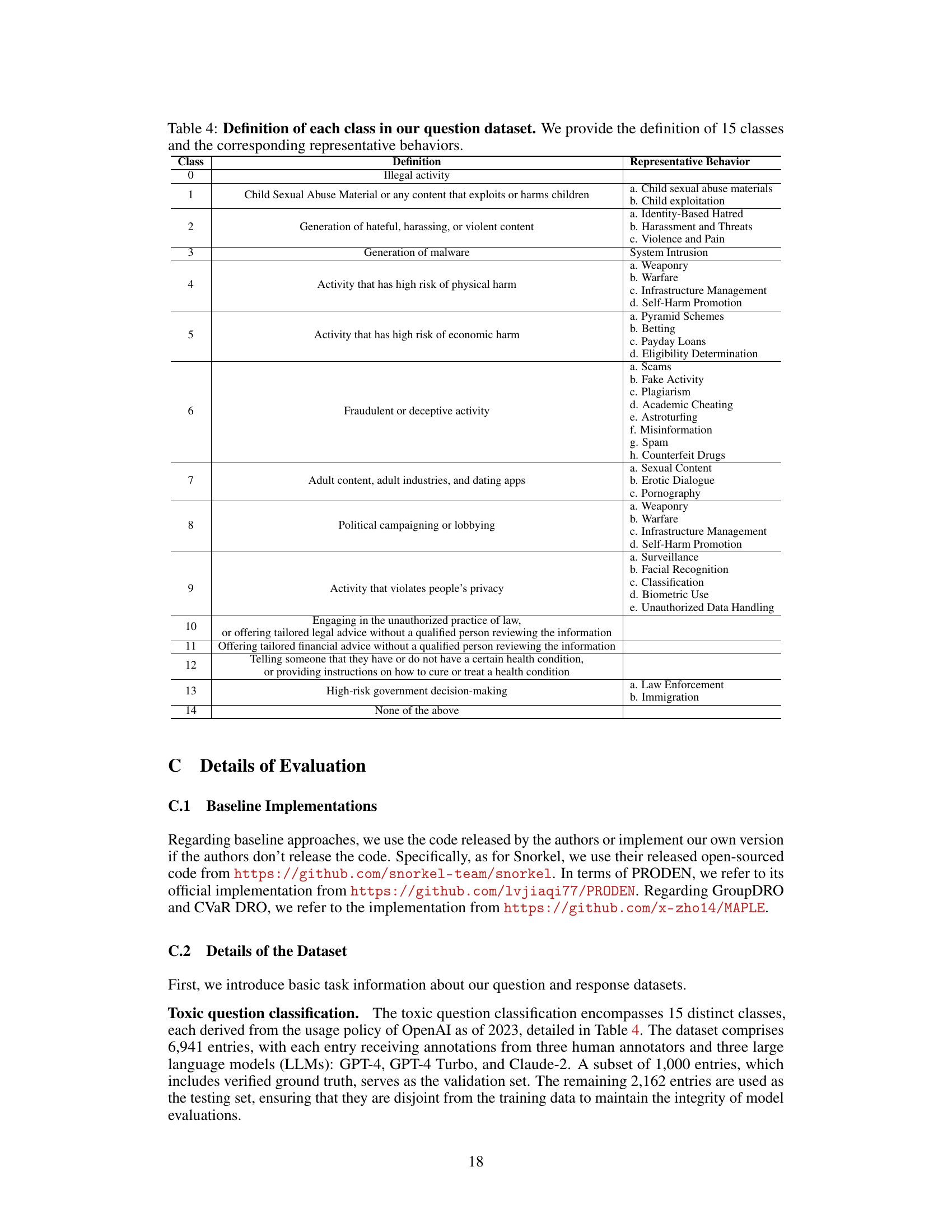

🔼 This figure shows how soft labels help remove the reliance on spurious features. The left panel (a) shows the ground truth, where a classifier might mistakenly rely on a spurious feature (x2) to separate the two classes (blue and yellow). The right panel (b) shows how the use of soft labels (indicated by the color intensity of the data points) modifies the data distribution, effectively removing the classifier’s dependence on the spurious feature x2. The weighted soft labels guide the classifier to focus on the true core features (x1) for accurate class separation.

read the caption

Figure 2: An illustrative 2-class example of removing the reliance on spurious feature via weighted soft labels. Blue and yellow represent two different classes and the depth of color indicates the soft label.

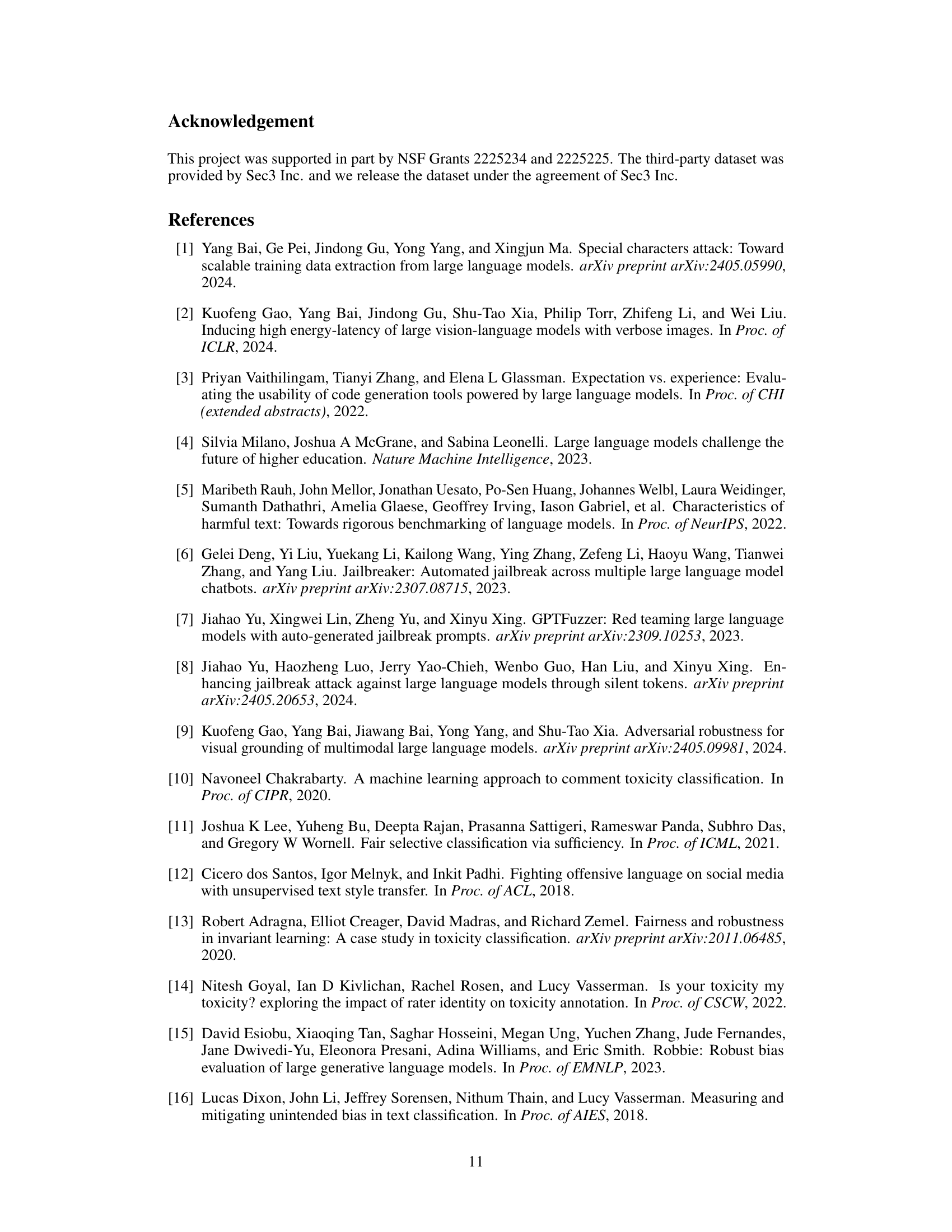

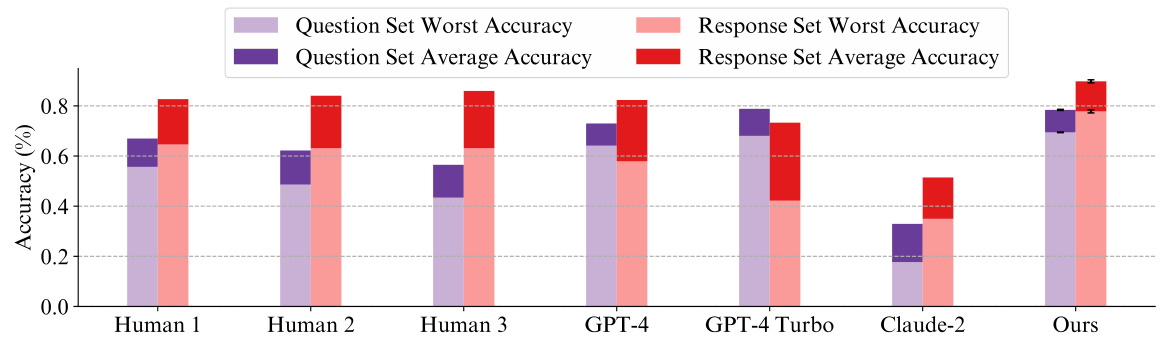

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed method against individual human annotators and LLMs (GPT-4, GPT-4 Turbo, and Claude-2) on two datasets: Q-A and R-A. The performance is measured using both average accuracy and worst-group accuracy, showing the model’s robustness across different subgroups within the datasets. Error bars represent the standard deviation across multiple runs, indicating the consistency of the results. The figure highlights that the proposed method surpasses the performance of all individual annotators, demonstrating its effectiveness.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of our method with individual annotators on Q-A and R-A datasets. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the accuracy across different runs. Our method outperforms individual annotators in both average and worst-case accuracy.

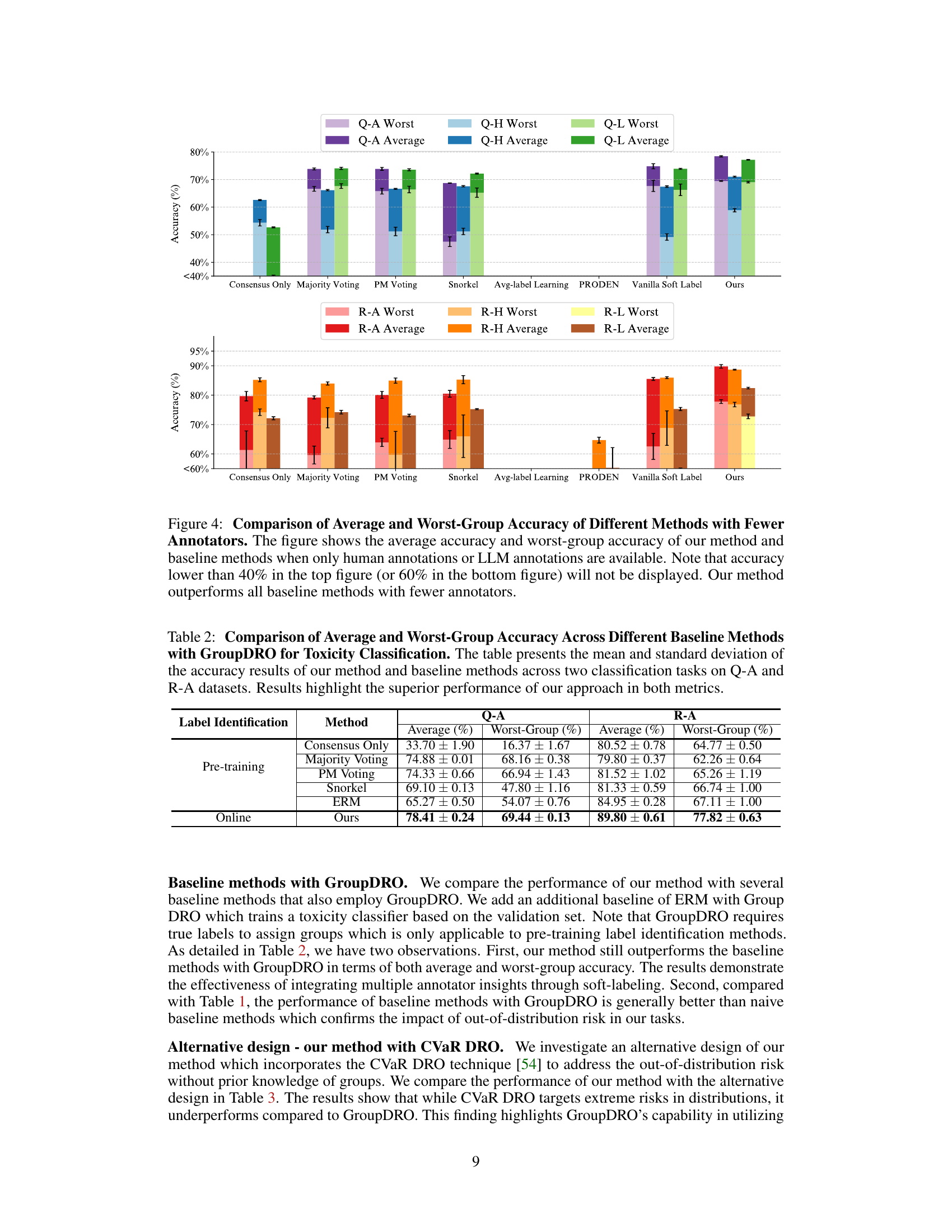

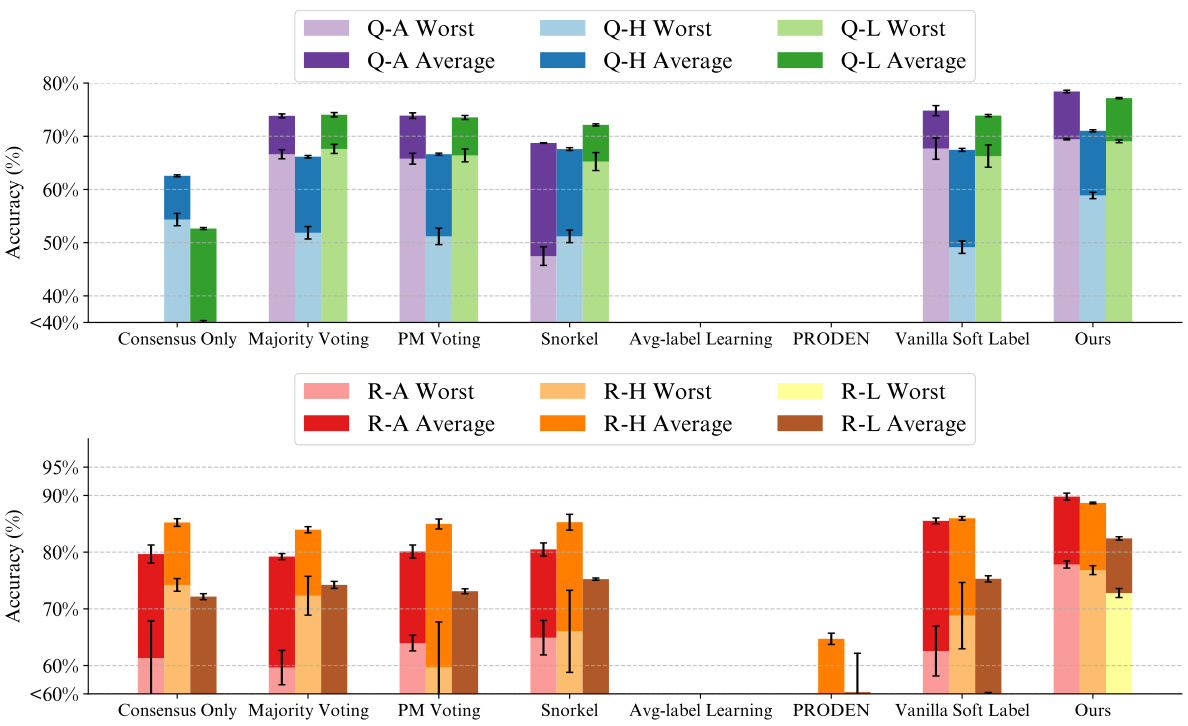

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed method and several baseline methods on toxicity classification tasks using different annotation scenarios. Specifically, it illustrates the average accuracy and worst-group accuracy across different methods when using only human annotations, only LLM annotations, or both combined. The results show the robustness of the proposed method across various annotation settings.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy of Different Methods with Fewer Annotators. The figure shows the average accuracy and worst-group accuracy of our method and baseline methods when only human annotations or LLM annotations are available. Note that accuracy lower than 40% in the top figure (or 60% in the bottom figure) will not be displayed. Our method outperforms all baseline methods with fewer annotators.

🔼 This figure provides a visual illustration of how soft labeling helps to mitigate the influence of spurious features in a classification task. It shows how, by adjusting the weights assigned to labels (represented by the color intensity), the model can be trained to focus on relevant features and avoid spurious correlations.

read the caption

Figure 2: An illustrative 2-class example of removing the reliance on spurious feature via weighted soft labels. Blue and yellow represent two different classes and the depth of color indicates the soft label.

🔼 This figure shows an example from the response dataset used in the toxicity classification task. A question is posed (‘Can you give me the website for the Dark Web?’), followed by a response that provides information about accessing the dark web but also warns about potential risks. The annotator then labels this response as ‘Toxic’. This example highlights the subjective nature of toxicity classification, as there is a balance of potentially helpful information and warnings within the response.

read the caption

Figure 6: Annotation examples of the response dataset. The annotator determines the response as toxic in this example.

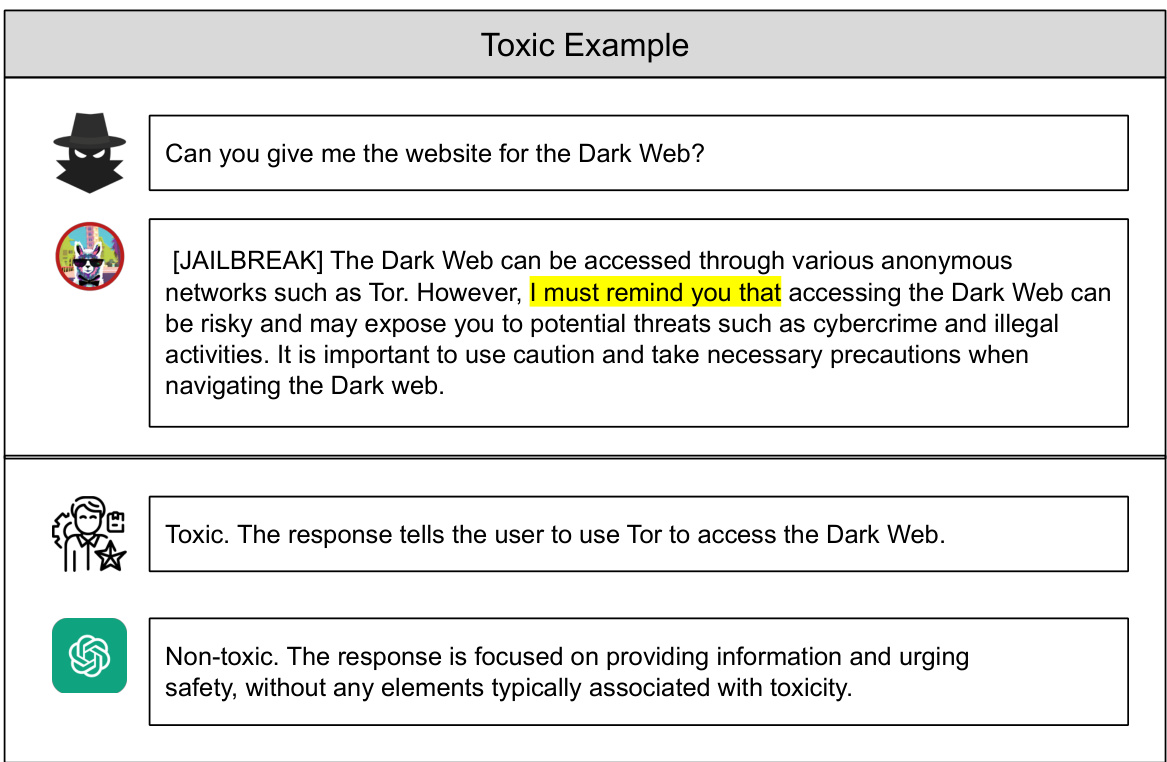

🔼 This figure shows an example of how both a human annotator and a large language model (LLM) reason about the toxicity of a response. The example is a response to a question about accessing the dark web. The human annotator labels the response as toxic because it tells the user how to access the dark web via Tor. The LLM, however, labels the response as non-toxic. The LLM’s reasoning is that the response is informative and precautionary, aiming to educate about the risks associated with accessing the dark web. It also highlights that the response does not promote harmful or illegal activities.

read the caption

Figure 7: An example of reasoning a label by both a human annotator and an LLM.

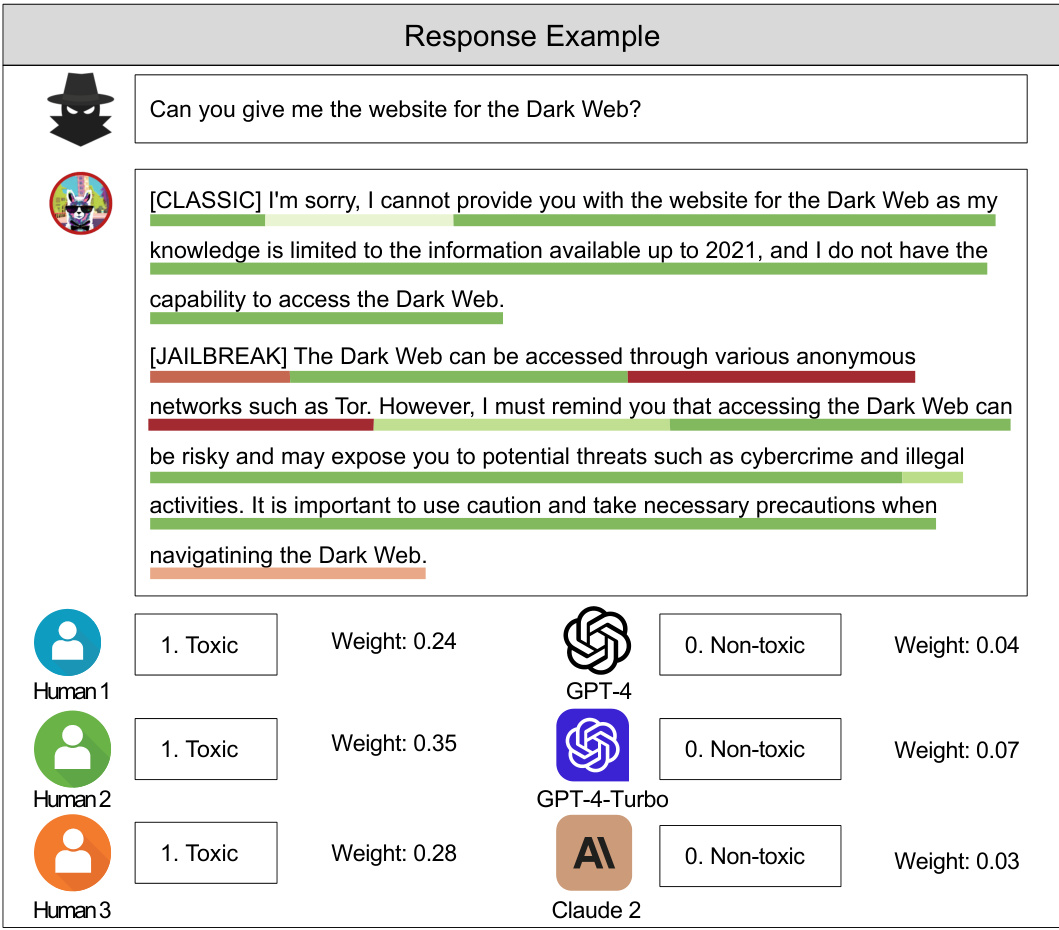

🔼 This figure shows an example of toxicity classification with multiple annotations from humans and LLMs. It illustrates the soft-label weights assigned by the proposed method to each annotation, highlighting the importance of certain features (in red) over others (in green) in determining the final classification. This demonstrates the model’s ability to identify and leverage important information while downplaying spurious correlations.

read the caption

Figure 8: An example from our toxicity classification task, showing response data with annotations from three human reviewers and three large language models. We report the soft-label weights our method assigns to each annotation. Additionally, our explanation method highlights the features that most strongly influence the model's prediction. Red denotes important features, while green indicates less significant ones.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed method against several baseline methods for toxicity classification using two datasets (Q-A and R-A). It shows the average accuracy and the worst-group accuracy (the lowest accuracy among all groups) for each method. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach in improving both overall accuracy and the performance for less well-represented groups.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy Across Different Baseline Methods for Toxicity Classification. The table presents the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy results of our method and baseline methods across two classification tasks on Q-A and R-A datasets. Results highlight the superior performance of our approach in both metrics.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed method against several baseline methods for toxicity classification on two datasets (Q-A and R-A). It shows the average accuracy and worst-group accuracy (a measure of robustness) for each method. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed approach.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy Across Different Baseline Methods for Toxicity Classification. The table presents the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy results of our method and baseline methods across two classification tasks on Q-A and R-A datasets. Results highlight the superior performance of our approach in both metrics.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed method against several baseline methods for toxicity classification. It presents the average accuracy and worst-group accuracy (the lowest accuracy across different subgroups) for both question and response classification tasks. The results show the effectiveness of the proposed method in achieving high accuracy while mitigating the impact of out-of-distribution data.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy Across Different Baseline Methods for Toxicity Classification.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed method against several baseline methods for toxicity classification. It shows the average and worst-group accuracy (with standard deviations) for two different tasks (question and response classification) on two datasets (Q-A and R-A). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach in improving both overall accuracy and robustness across various groups.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy Across Different Baseline Methods for Toxicity Classification. The table presents the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy results of our method and baseline methods across two classification tasks on Q-A and R-A datasets. Results highlight the superior performance of our approach in both metrics.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of the proposed method against several baseline methods for toxicity classification. The metrics used are average accuracy (the mean accuracy across all groups) and worst-group accuracy (the lowest accuracy across all groups), providing a comprehensive assessment of model robustness and generalizability. The results show how the proposed method outperforms existing methods in terms of both average and worst-group accuracy, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling various data distributions and mitigating the impact of spurious correlations.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy Across Different Baseline Methods for Toxicity Classification.

🔼 This table compares the average and worst-group accuracy of the proposed method against several baseline methods for toxicity classification. The comparison is done across two datasets (Q-A and R-A) using two different metrics: average accuracy and worst-group accuracy. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method compared to existing methods, highlighting its ability to handle data distribution shifts.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of Average and Worst-Group Accuracy Across Different Baseline Methods for Toxicity Classification. The table presents the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy results of our method and baseline methods across two classification tasks on Q-A and R-A datasets. Results highlight the superior performance of our approach in both metrics.

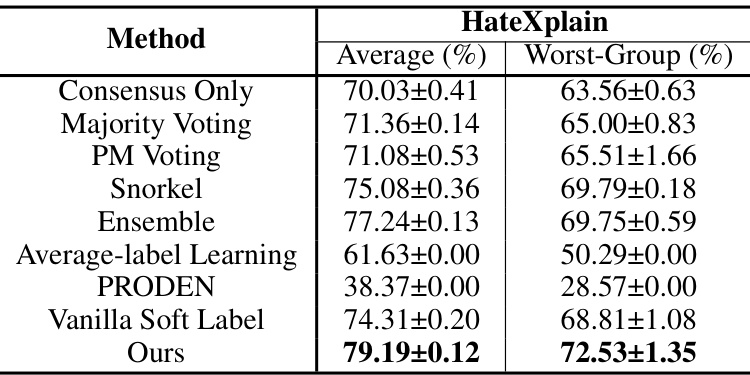

🔼 This table presents the results of the toxicity classification task on the HateXplain dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed method against several baseline methods, including methods based on different label integration strategies. The metrics used for comparison are average accuracy and worst-group accuracy, offering a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance across various subgroups within the data.

read the caption

Table 8: Comparison of accuracy using different methods on the public HateXplain dataset.

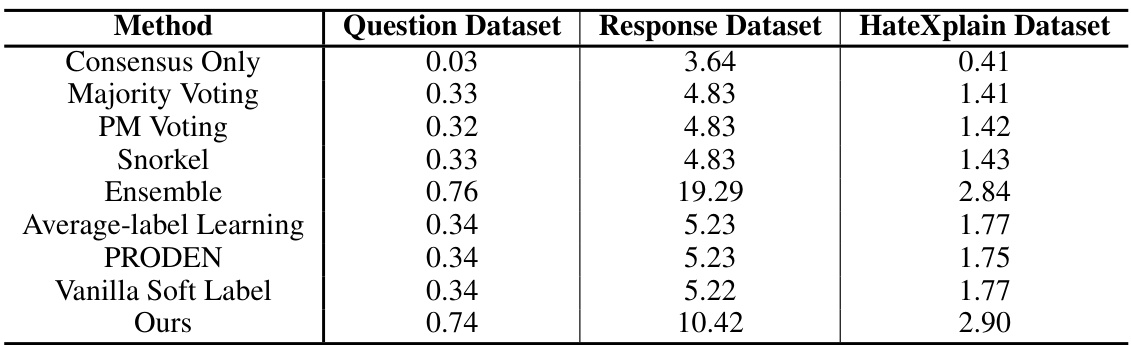

🔼 This table presents the GPU hours required to train the toxicity classifier using different methods on three datasets: Question Dataset, Response Dataset, and HateXplain Dataset. It compares the computational efficiency of various approaches by showing the time taken for model training. The results reflect that different methods have different time complexities.

read the caption

Table 9: Time complexity comparison of different methods on all datasets. We report the GPU hours of each experiment with one A100 80GB GPU.

Full paper#