↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Machine learning models often exhibit unfair biases, particularly in high-stakes domains like healthcare and hiring. Counterfactual fairness (CF) is a notion that addresses this issue, requiring model predictions to be consistent even if an individual’s sensitive attributes (e.g., race or gender) were different. However, previous methods for achieving CF often significantly hurt the predictive performance of the model. This creates a critical trade-off between fairness and accuracy that needs to be carefully considered.

This research provides a theoretical analysis of this trade-off, showing the inherent limits of achieving perfect CF. The authors introduce a novel method, based on combining factual and counterfactual predictions, that guarantees optimal CF while minimizing performance loss. They also extend their approach to handle scenarios with incomplete causal knowledge. The proposed method outperforms existing techniques in experiments using both synthetic and real-world datasets, demonstrating its effectiveness and practical value. This work provides important theoretical insights and practical tools for building fairer and more accurate machine learning models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it formally analyzes the trade-off between counterfactual fairness and predictive performance in machine learning, a critical issue in high-stakes applications. It proposes novel methods to achieve optimal fairness with minimal performance loss, addressing a major challenge in the field. The findings are important for researchers developing fair and accurate ML models, as well as for those working on causal inference and algorithmic fairness. The theoretical analysis and practical algorithm significantly advance the state-of-the-art in fair machine learning.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows a causal graph illustrating the relationships between variables in a causal model. A represents the sensitive attribute (e.g., gender or race), Y is the target variable (the outcome of interest, e.g., loan approval or hiring decision), U signifies unobserved confounders (factors affecting both A and Y that are not directly measured), and X includes the remaining observed features. The arrows show the direction of causal influence. The assumption is that the theoretical analysis applies to a range of causal models beyond this specific graph, so long as a specific set of conditions hold.

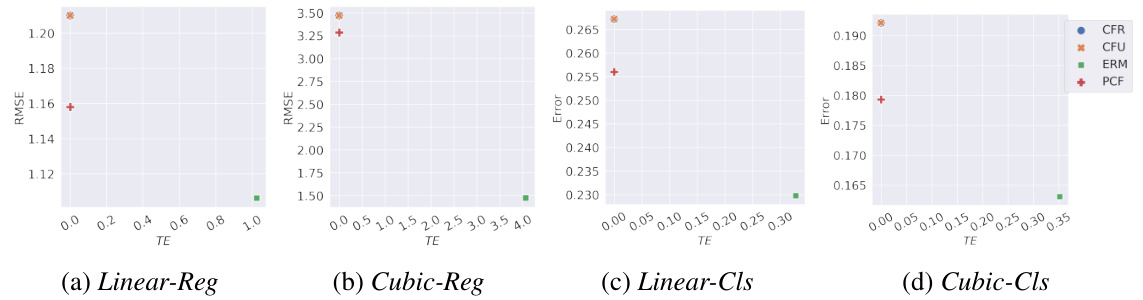

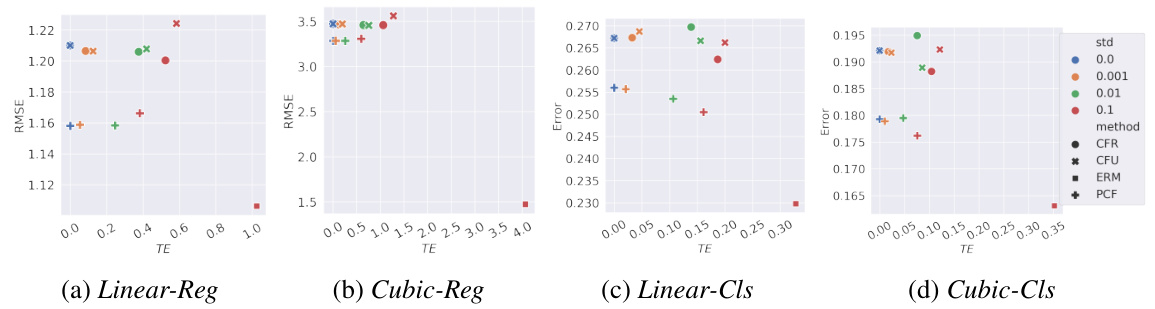

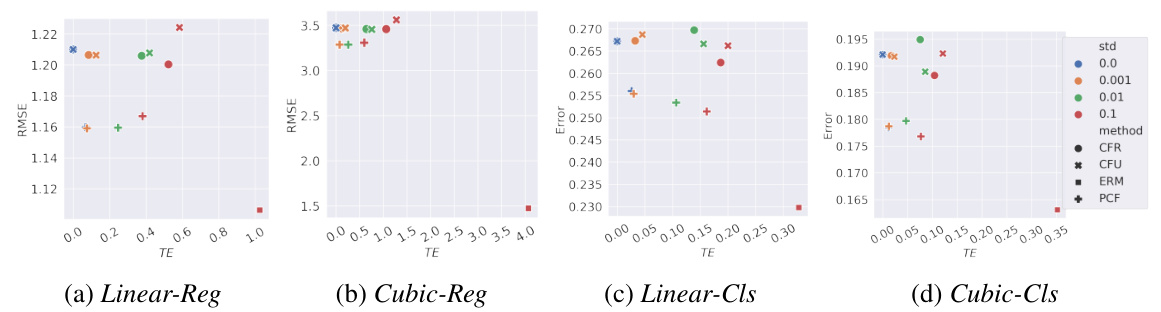

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on synthetic datasets, where ground truth counterfactuals were available. It compares different fairness methods (ERM, CFU, CFR, PCF) across four scenarios: Linear Regression, Cubic Regression, Linear Classification, and Cubic Classification. The results illustrate the error (RMSE or classification error) and total effect (TE) for each method and dataset. The goal is to show that PCF achieves optimal counterfactual fairness with minimal performance degradation.

In-depth insights#

Optimal CF Fairness#

The concept of ‘Optimal CF Fairness’ within a machine learning model seeks to minimize the inherent trade-off between achieving perfect counterfactual fairness (CF) and maintaining high predictive accuracy. It investigates the theoretical limits of fairness, quantifying the unavoidable performance loss when strictly enforcing CF. This analysis often involves examining optimal predictors under CF constraints and comparing them to unconstrained optimal predictors, revealing the excess risk introduced by fairness. Key factors influencing this trade-off often include the strength of the causal relationships between sensitive attributes, target variables, and other features. The pursuit of optimal CF fairness necessitates a deep understanding of causal inference, enabling the development of algorithms that balance fairness and accuracy by cleverly combining factual and counterfactual predictions. This optimization frequently involves intricate mathematical proofs and theoretical analysis to formally establish the properties of optimal fair predictors.

Inherent Tradeoffs#

The concept of “inherent tradeoffs” in the context of counterfactual fairness (CF) highlights the fundamental tension between achieving perfect fairness and maintaining high predictive accuracy. A perfectly CF model, while ensuring that an individual’s prediction remains unchanged regardless of their sensitive attribute, may inevitably sacrifice predictive power. This tradeoff arises because enforcing CF often restricts the features a model can utilize, leading to a loss of information and reduced predictive ability. The paper likely explores the mathematical quantification of this tradeoff and investigates methods to minimize predictive performance degradation while adhering to CF constraints as much as possible. It might propose techniques that find an optimal balance between fairness and accuracy by adjusting the level of CF enforcement or by incorporating auxiliary information to improve model performance. Understanding and quantifying inherent tradeoffs are crucial for responsible AI development, as it allows practitioners to make informed decisions about the acceptable level of fairness and accuracy based on specific application contexts and ethical considerations.

Incomplete Knowledge#

The concept of ‘Incomplete Knowledge’ in the context of counterfactual fairness is crucial. It acknowledges that in real-world applications, we rarely possess complete causal knowledge. This limitation significantly impacts the accuracy of counterfactual predictions, which are fundamental to assessing and mitigating bias. Imperfect causal estimations directly affect fairness metrics, potentially leading to unfair outcomes despite the best intentions. The challenge is to design robust methods that can still achieve good levels of fairness even under uncertainty about causal structure and the presence of unobserved confounders. Addressing incomplete knowledge involves developing techniques to handle uncertainty in estimating counterfactuals and employing algorithms that are resilient to these estimation errors. This may involve integrating methods from causal inference, robustness analysis, or machine learning techniques designed for noisy or incomplete data. The success of such methods would significantly impact the practical applicability and effectiveness of counterfactual fairness in high-stakes decision-making scenarios.

Plugin Method#

A plugin method, in the context of counterfactual fairness, offers a practical approach to enhance fairness without requiring retraining the entire model. It leverages a pre-trained model, which may be already optimized for predictive accuracy, and incorporates it into a fairness-enhancing framework. This avoids the computational cost and potential performance degradation associated with training a fair model from scratch. The effectiveness of a plugin method hinges on the quality of the pre-trained model and the method for integrating counterfactual information. The inherent trade-off between fairness and accuracy needs careful consideration when designing such a method, as perfect fairness might compromise predictive performance. A plugin method is particularly useful when complete causal knowledge is unavailable, enabling the application of fairness-enhancing techniques even in scenarios with incomplete data or imperfect counterfactual estimation.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the model’s applicability to scenarios with more complex causal structures and non-binary sensitive attributes. Improving the accuracy and efficiency of counterfactual estimation methods is crucial for practical implementations. Investigating the impact of different similarity measures on the trade-off between fairness and utility warrants further study. The model’s robustness to various data distributions and noise levels should be rigorously tested. A deeper investigation into the interplay between counterfactual fairness and other fairness notions is needed to determine the most appropriate approach in diverse contexts. Finally, developing standardized evaluation metrics and benchmarks for counterfactual fairness would advance the field significantly, enabling more robust comparisons and facilitating the development of new methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

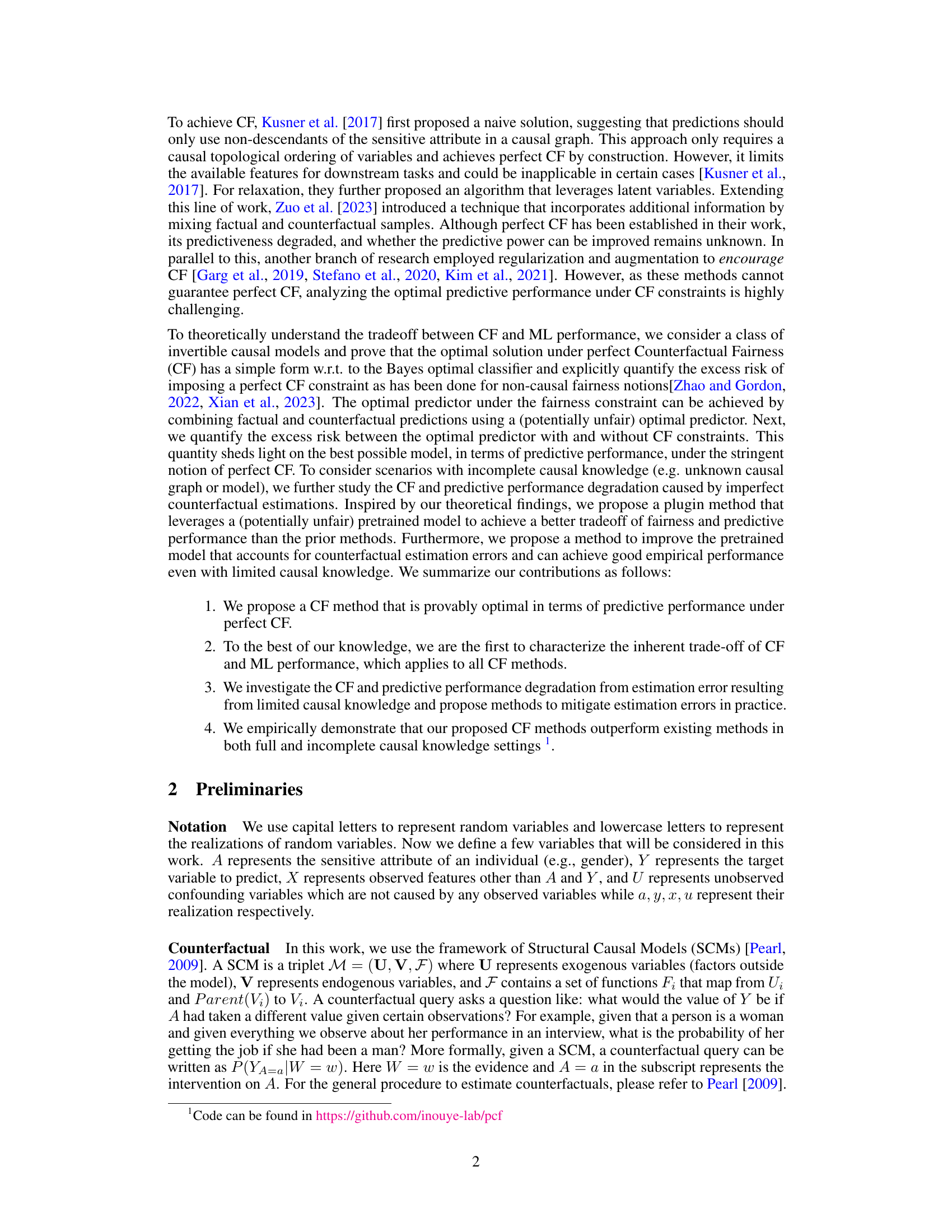

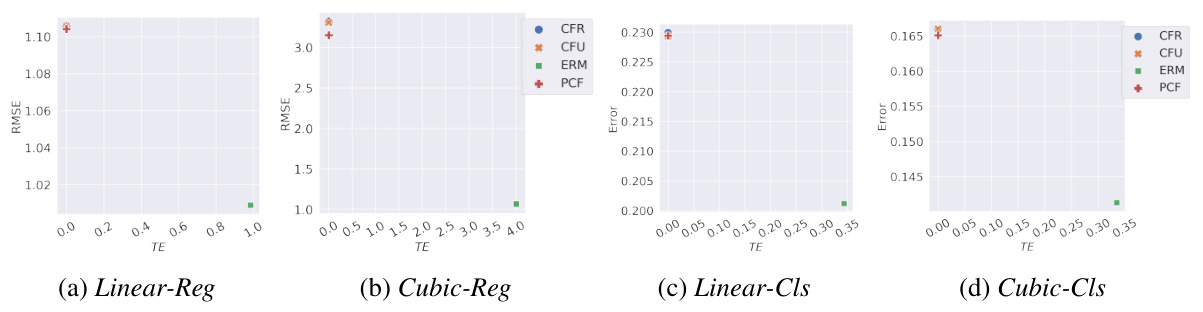

This figure shows the results of different fairness methods on synthetic datasets when ground truth counterfactuals are available. It compares four methods (CFR, CFU, ERM, and PCF) across four different tasks (Linear-Reg, Cubic-Reg, Linear-Cls, and Cubic-Cls). Each point represents a different setting. The x-axis represents the total effect (TE), a measure of counterfactual fairness violation. The y-axis represents the root mean squared error (RMSE) for regression tasks and the classification error for classification tasks. The figure demonstrates that PCF achieves the lowest error while maintaining perfect counterfactual fairness (TE=0), supporting the paper’s claim about its optimality.

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on synthetic datasets where ground truth counterfactuals were available. The figure compares different fairness methods (ERM, CFU, CFR, PCF) across four scenarios (Linear Regression, Cubic Regression, Linear Classification, Cubic Classification). Each subplot shows the tradeoff between Total Effect (TE) as a measure of counterfactual fairness and the model’s prediction error (RMSE for regression and Error for classification). The results visually demonstrate that the proposed method PCF achieves optimal predictive performance under the constraint of perfect counterfactual fairness.

This figure displays the results of four different machine learning models (ERM, CFU, CFR, and PCF) on four different synthetic datasets (Linear-Reg, Cubic-Reg, Linear-Cls, Cubic-Cls). Each model’s performance is evaluated using Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Total Effect (TE) metrics. The results show that PCF achieves perfect counterfactual fairness with the lowest error across all datasets, supporting the paper’s claim of PCF’s optimality under perfect CF constraints.

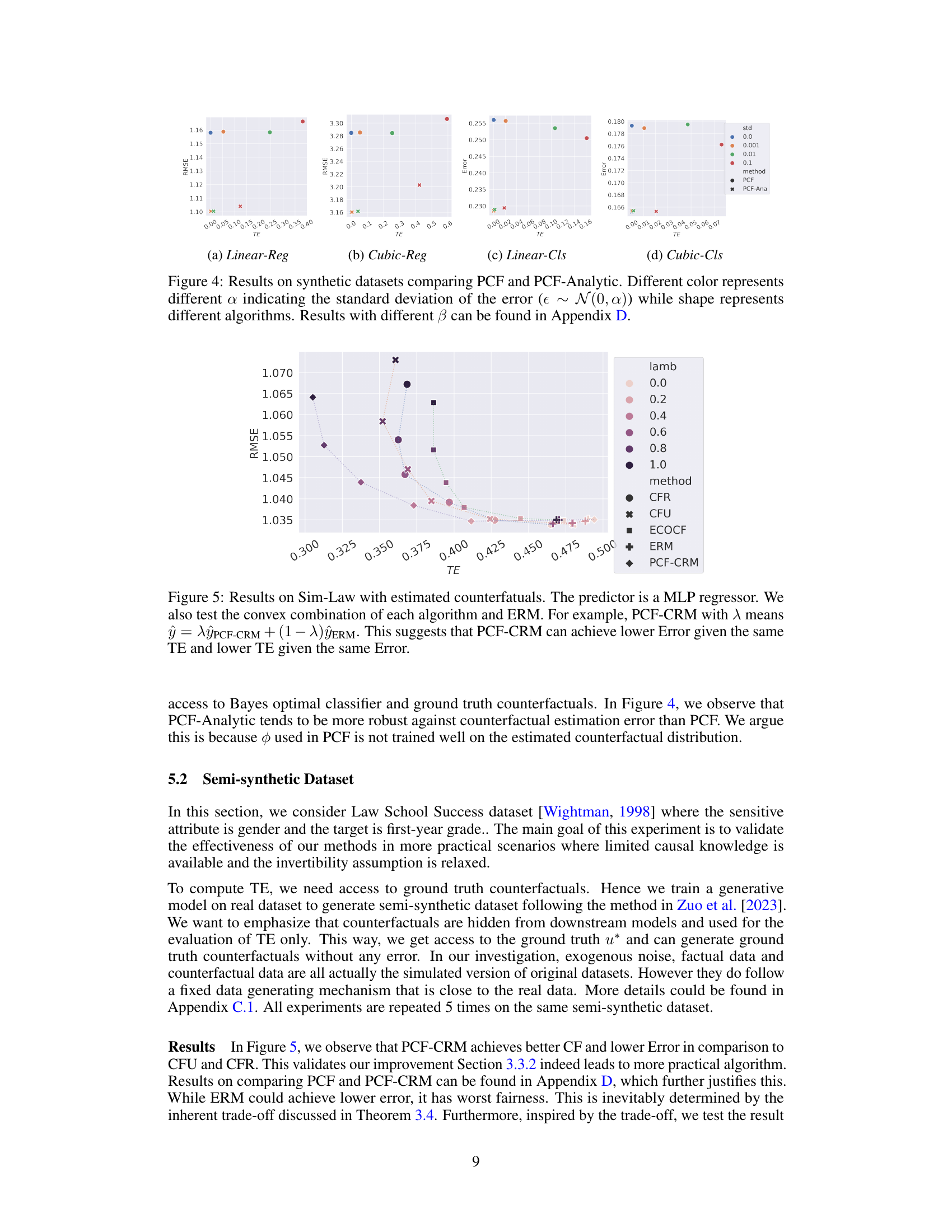

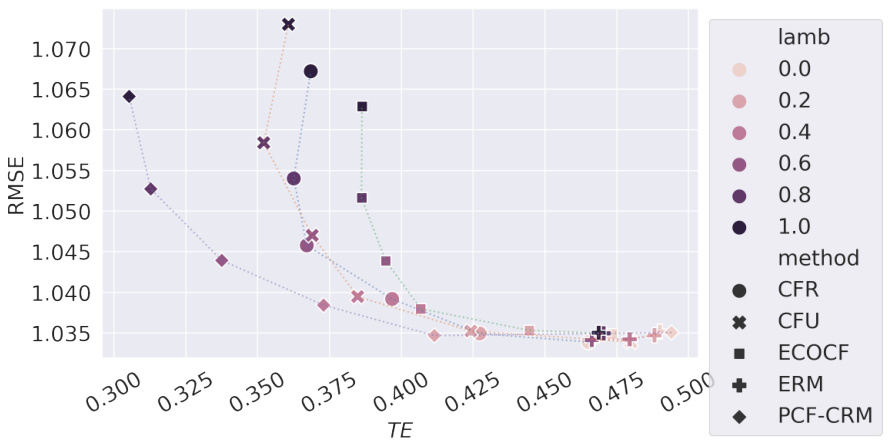

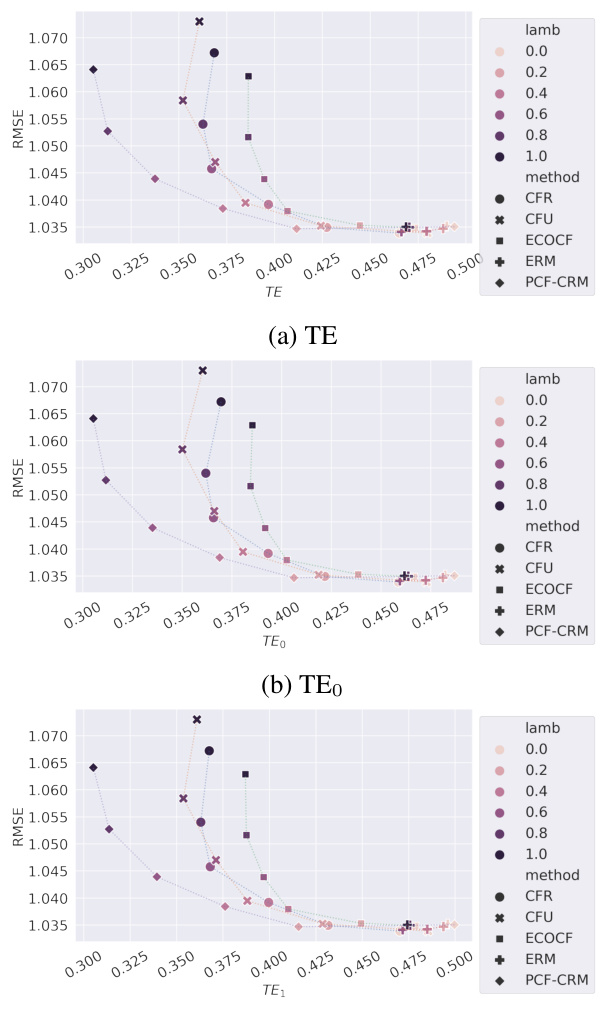

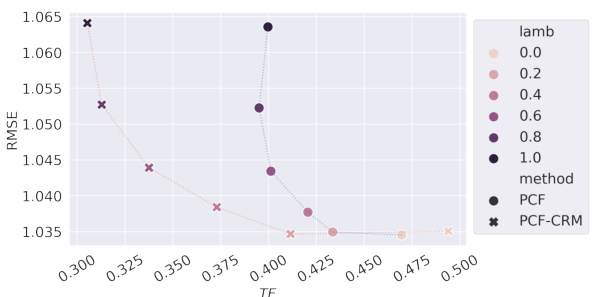

This figure shows the results of experiments conducted on the Sim-Law dataset using a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) regressor. It compares several methods for achieving counterfactual fairness (CF), including Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM), CFU, CFR, ECO-CF, and PCF-CRM. The x-axis represents the Total Effect (TE), a measure of CF violation, and the y-axis shows the root mean squared error (RMSE), a measure of prediction accuracy. The different colored lines show different convex combinations of PCF-CRM and ERM, demonstrating that PCF-CRM generally achieves better performance (lower RMSE) for a given level of CF (TE) or better CF for a given prediction accuracy. This supports the paper’s claim about the effectiveness of the PCF-CRM method.

This figure shows the results of different fairness methods on synthetic datasets when ground truth counterfactuals are available. It compares four methods: Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM), Counterfactual Fairness with U (CFU), Counterfactual Fairness with fair representation (CFR), and Plug-in Counterfactual Fairness (PCF). The x-axis represents the Total Effect (TE), a measure of counterfactual fairness, and the y-axis represents the RMSE (root mean squared error) or error for regression and classification tasks respectively. The plot demonstrates that PCF achieves the lowest error while maintaining perfect counterfactual fairness (TE = 0), validating Theorem 3.3 in the paper.

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on synthetic datasets, where ground truth counterfactuals were available. It showcases the performance of four different methods (ERM, CFU, CFR, and PCF) in terms of Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Total Effect (TE). The results demonstrate that PCF achieves the lowest prediction error while maintaining perfect counterfactual fairness.

This figure displays the results of experiments conducted on synthetic datasets, where ground truth counterfactuals were available. The results are visualized in four subplots, one for each of the following tasks: Linear Regression, Cubic Regression, Linear Classification, and Cubic Classification. Each subplot shows the relationship between the total effect (TE, a measure of counterfactual fairness) and the root mean squared error (RMSE) or error rate, depending on the task, for several different fairness methods. The goal is to show the trade-off between fairness and accuracy. The points represent results for different values of the sensitive attribute’s distribution, and the shapes represent different algorithms.

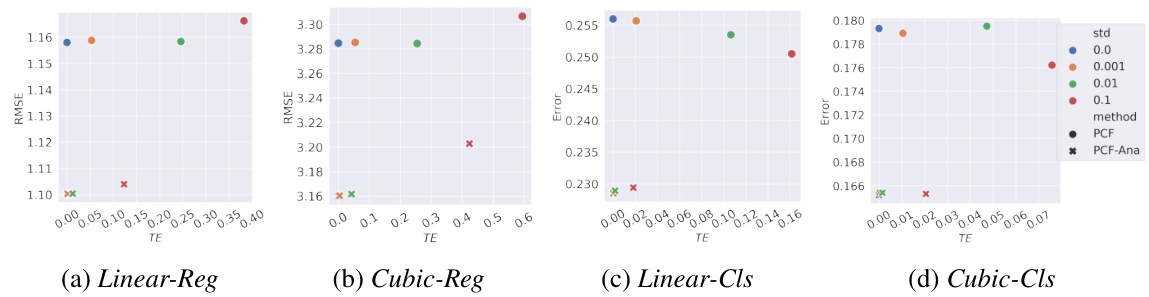

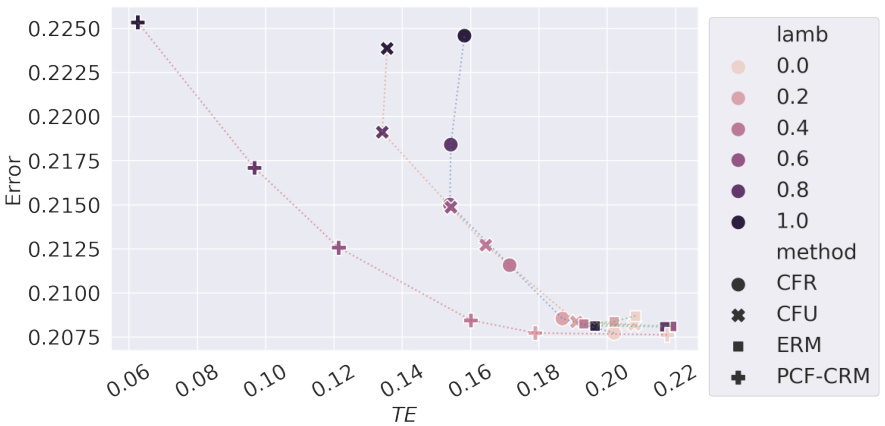

This figure shows the results of experiments on synthetic datasets, investigating the impact of counterfactual estimation errors on different fairness algorithms. The x-axis represents the total effect (TE), a metric for counterfactual fairness, and the y-axis represents the root mean squared error (RMSE), a measure of predictive performance. Different colors represent different levels of added noise (standard deviation of the error) during counterfactual estimation, while different shapes represent different fairness algorithms. This figure helps visualize the trade-off between fairness and accuracy under various levels of uncertainty in counterfactual estimation.

This figure shows the results of the experiment conducted on the Sim-Adult dataset using a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) classifier as the predictor. The experiment evaluated the performance of different methods under counterfactual estimation error. The x-axis represents the total effect (TE), a measure of counterfactual fairness, and the y-axis represents the error of the predictor. Different colors represent different levels of added gaussian noise used to simulate the counterfactual estimation error. The plot shows how the error and fairness trade-off changes with different algorithms and levels of noise.

This figure shows the results of experiments on the Sim-Law dataset using a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) regressor. The main comparison is between different fairness-aware algorithms (CFR, CFU, ERM, PCF-CRM) and their performance in terms of prediction error and Total Effect (TE). A key aspect is exploring the trade-off between fairness and accuracy by varying a mixing parameter (λ) that blends the predictions of PCF-CRM with ERM. The results indicate that PCF-CRM consistently outperforms other methods in achieving a balance between low error and low TE.

Full paper#