↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Estimating human pose using inertial measurement units (IMUs) is challenging because of the inherent limitations of existing deep learning models, particularly Transformers, in capturing the fixed-length sequence’s structural properties. Traditional methods often struggle with accuracy and steadiness issues, leading to inaccurate and jittery pose estimations.

This research introduces a novel Sequence Structure Module (SSM) to address these limitations. The SSM utilizes the inherent structural information of fixed-length IMU sequences to improve accuracy and steadiness in pose estimations. Experiments using spatial and temporal SSM variations demonstrated significant improvements over state-of-the-art methods across multiple benchmark datasets, showcasing the efficacy of their approach in handling fixed-length sequential data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in inertial pose estimation and sequence modeling. It addresses the limitations of existing transformer architectures, proposes a novel solution for fixed-length sequences, and demonstrates superior performance on benchmark datasets. This opens avenues for improving transformer models for various applications dealing with structured sequential data.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows a person wearing six IMUs on their body. The left side shows the IMU placement on the body; the right side shows various example poses captured by the system in real-time, demonstrating the system’s capability to handle various movement types, from simple daily actions to complex poses.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for sparse inertial human pose estimation. Two benchmark datasets, DIP-IMU and TotalCapture, are used for evaluation. The comparison is done using multiple metrics: SIP error, Angular error, Positional error, Mesh error, and Jitter. The best and second-best results for each metric on each dataset are highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively. The table demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method across all metrics and datasets.

In-depth insights#

IMU Pose Estimation#

Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) pose estimation is a crucial area of research with significant implications for various applications like motion capture, robotics, and augmented reality. Accuracy and robustness are paramount concerns, as IMUs are susceptible to noise and drift. Traditional approaches often rely on complex filtering techniques or fusion with other sensors like cameras. However, deep learning methods, especially those utilizing recurrent neural networks and transformers, have emerged as promising alternatives. These methods can directly learn the mapping from IMU sensor readings to pose, potentially achieving improved accuracy and efficiency. A key challenge lies in effectively modeling the temporal dependencies within IMU data, which deep learning approaches strive to address. Furthermore, the inherent sparsity of IMU sensor configurations necessitates clever techniques to deal with missing or incomplete information, adding another level of complexity to the estimation problem. Recent advancements explore various architectures, including transformers, to exploit long-range dependencies for enhanced accuracy. The use of structural information, such as the geometric layout of IMUs or prior knowledge of motion patterns, is another active research direction that could lead to further improvements in robustness and performance.

Transformer Limits#

The heading ‘Transformer Limits’ prompts a thoughtful exploration of Transformer models’ inherent constraints. While Transformers excel at capturing long-range dependencies in sequential data, their effectiveness is not universal. Fixed-length input sequences, a common characteristic in many applications like time-series analysis or inertial pose estimation, pose a challenge. Native Transformers, designed for variable-length sequences, lack the inductive bias to effectively leverage the inherent structure within these fixed-length inputs. This limitation results in suboptimal performance. Spatial and temporal structural information present in fixed-length data, such as IMU sensor readings or image frames, are often ignored by the standard architecture. This oversight is a significant source of inaccuracy and jitter in applications like human pose estimation. Addressing these limits involves enriching the Transformer architecture with explicit mechanisms to capture and utilize these structural patterns. Methods such as incorporating sequence structure modules that inject prior structural knowledge or learn such knowledge from data can significantly improve the performance of Transformers on fixed-length sequential data. The exploration of different structural inductive biases is crucial for advancing Transformer architectures, maximizing their potential in various applications.

SSM Architecture#

The Sequence Structure Module (SSM) architecture is a crucial innovation in this research, designed to address the limitations of native Transformers when handling fixed-length sequences with inherent structural patterns. SSM injects structural information, either learned from data or provided a priori, into the Transformer’s input features. This is achieved by multiplying the sequence embedding with a structural matrix (S), followed by layer normalization and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP). This approach is particularly valuable for applications like inertial pose estimation, where fixed-length sensor readings possess clear spatial and temporal structure. Two variants are proposed: SSM-S for incorporating spatial relationships between sensors, learned or explicitly defined, and SSM-T for injecting temporal structure based on smooth priors, thus improving steadiness. The SSM architecture is shown to improve both accuracy and smoothness, outperforming state-of-the-art methods on multiple benchmarks. The flexibility of SSM in leveraging either learned or explicit structural information is a key strength, demonstrating the architecture’s adaptability and potential for broad application in other domains beyond inertial pose estimation.

Spatial-Temporal Fusion#

Spatial-temporal fusion, in the context of human pose estimation using inertial measurement units (IMUs), refers to the integration of spatial and temporal information from sensor readings. Spatial information leverages the relative positions of IMUs on the body, capturing the relationships between different body segments. Temporal information, on the other hand, uses the sequential nature of IMU readings to track body motion over time. Effective fusion strategies are critical because individual spatial or temporal models are often insufficient for accurate pose estimation. Combining these sources using architectures like transformers or recurrent neural networks is crucial. The challenge lies in effectively weighting spatial and temporal dependencies to avoid bias toward one information source over the other. Successful fusion often involves learning representations that disentangle spatial and temporal aspects, ultimately leading to more robust and accurate pose estimation, especially in situations with noisy or sparse IMU data. A successful model should not only improve the accuracy of pose estimations but also reduce the jitter (noise) in the estimated motion trajectory.

Real-world Testing#

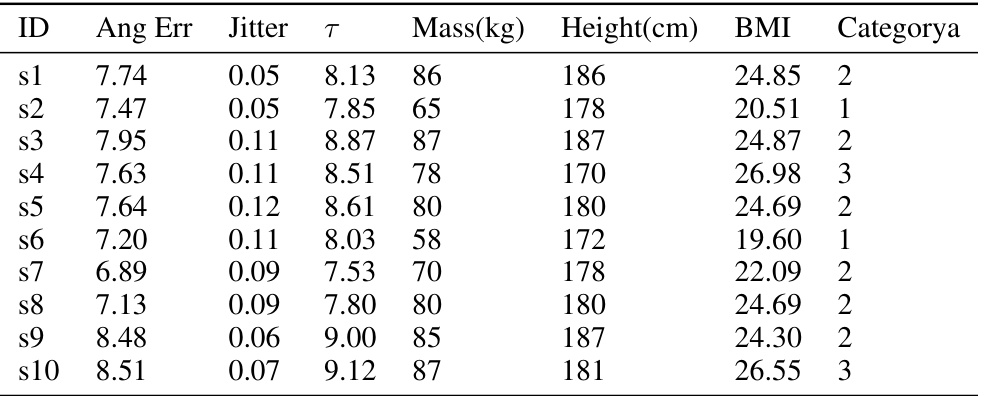

A robust evaluation of any pose estimation system necessitates real-world testing. This goes beyond controlled lab settings and delves into the complexities of actual environments. Real-world tests should assess performance under diverse conditions, including varying lighting, occlusions, and unexpected movements. The system’s ability to handle noise and jitter from real-world sensor data is crucial. Furthermore, latency and computational efficiency are critical considerations for real-time applications. The presence of confounding factors such as clothing, accessories, and varying body types directly impacts the accuracy and reliability of the system. A truly comprehensive evaluation would examine how the system adapts to these challenges, providing a more realistic measure of its practicality and usability. Qualitative metrics beyond quantitative measurements of error are invaluable, such as observing the smoothness of motion capture and the system’s resilience to artifacts. Ultimately, real-world testing determines a system’s true capability to function effectively beyond theoretical or simulated environments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

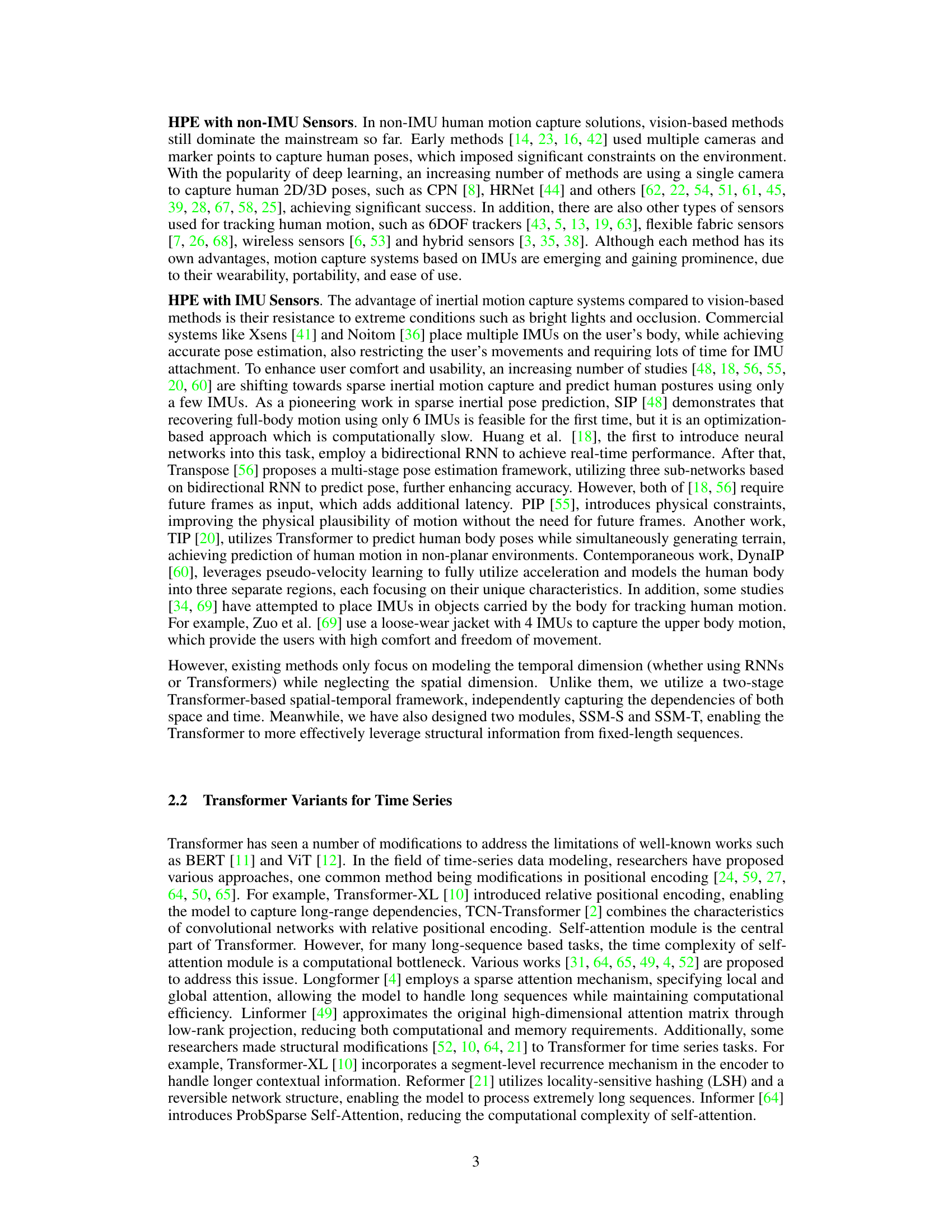

This figure illustrates the proposed architecture of the Sequence Structure Module (SSM) in comparison with the traditional methods that only utilize temporal encoders. Part (a) shows the traditional approach using only temporal encoders. (b) demonstrates the novel spatial-temporal framework that combines both spatial and temporal encoders. (c) integrates the SSM into the spatial-temporal framework, showing how it enhances the architecture. Finally, (d) provides a detailed view of the SSM itself, explaining its components: a structural matrix (S), a Layer Normalization (LN) layer, and a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) block. The SSM leverages structural information of fixed-length sequences to improve performance.

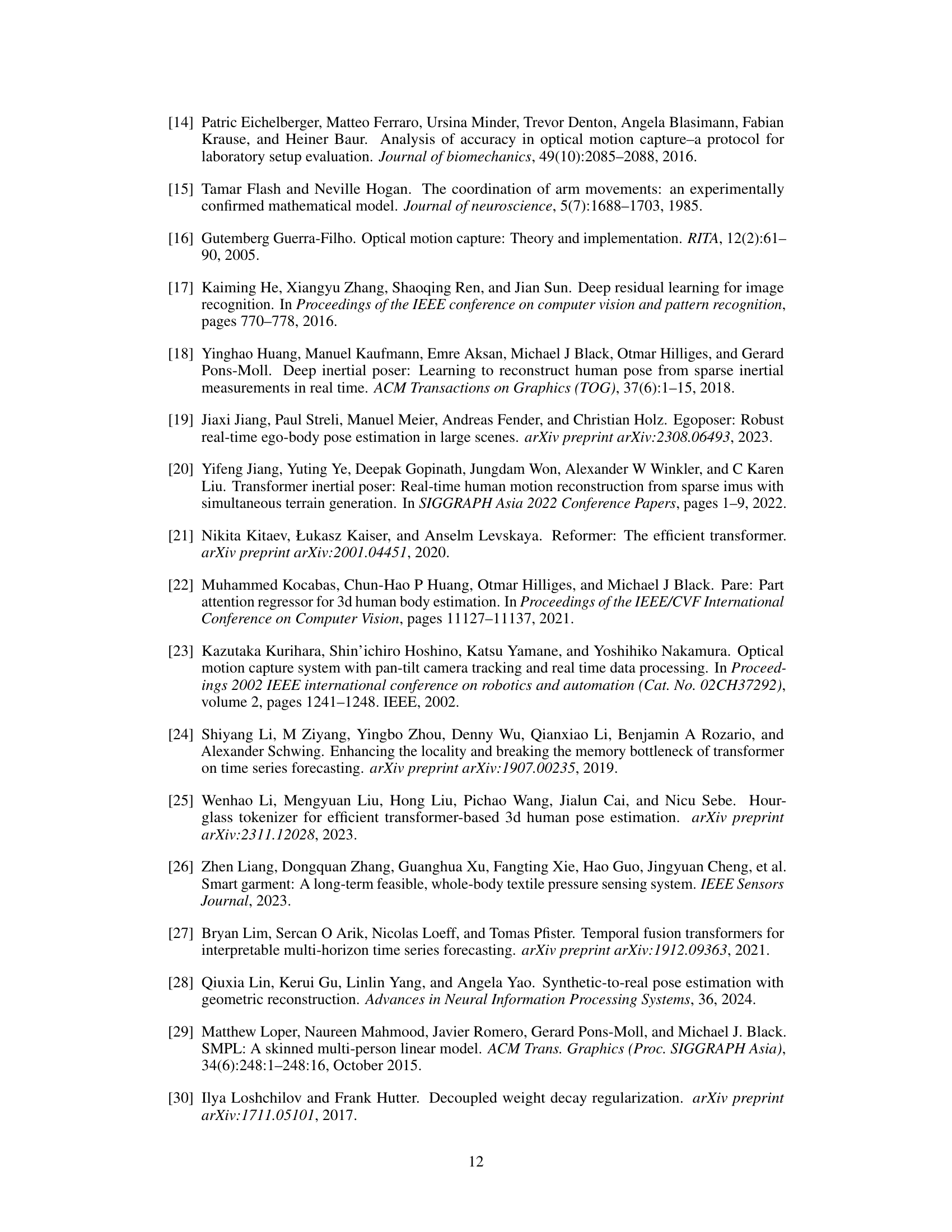

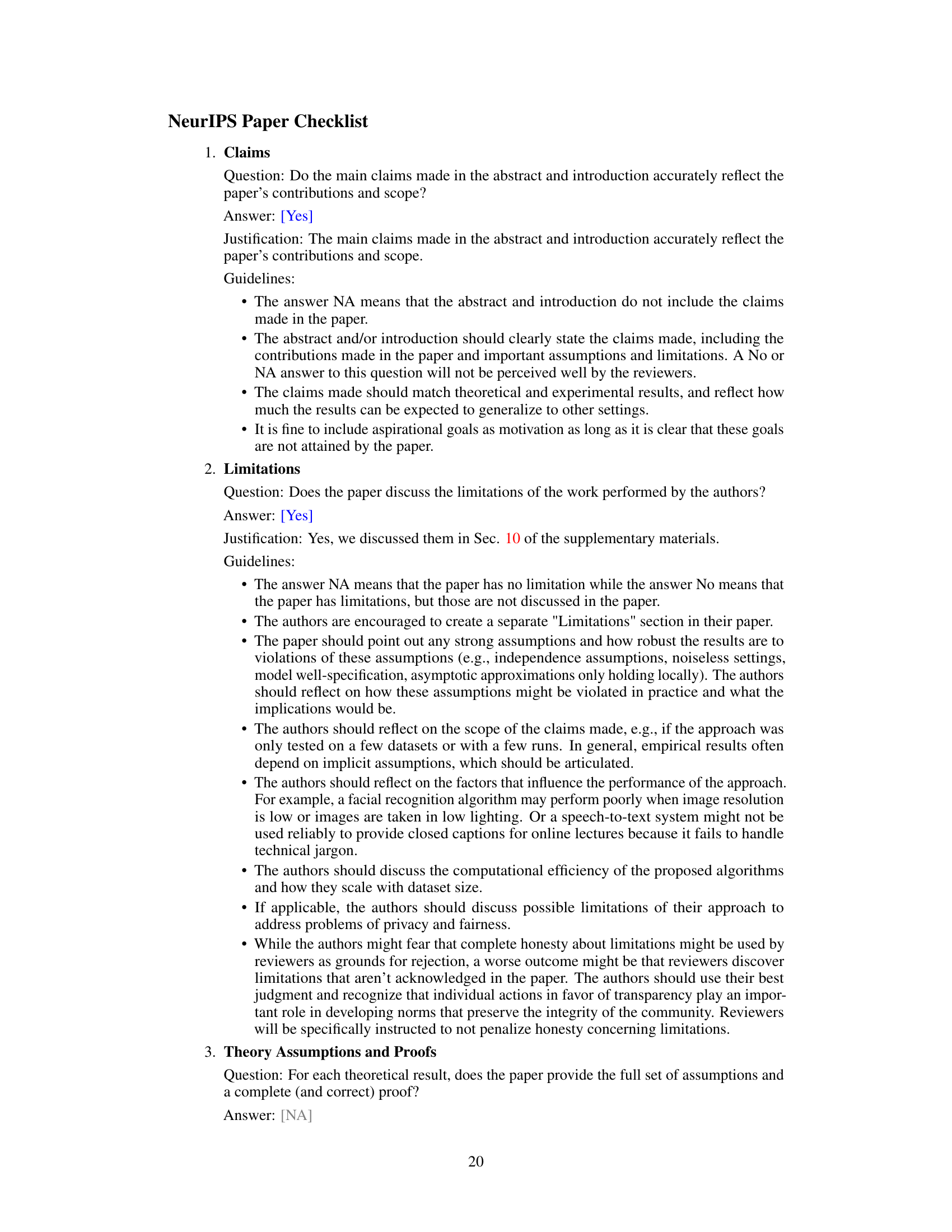

This figure visualizes the spatial structure matrix (SE-S) and three versions of the temporal structure matrix (SE-T) with different hyperparameters (σ). SE-S is a correlation matrix calculated from AMASS dataset showing the correlation between different joints. SE-T represents the correlation between different frames in the sequence, with higher values for closer frames and decreasing values for more distant frames, controlled by σ.

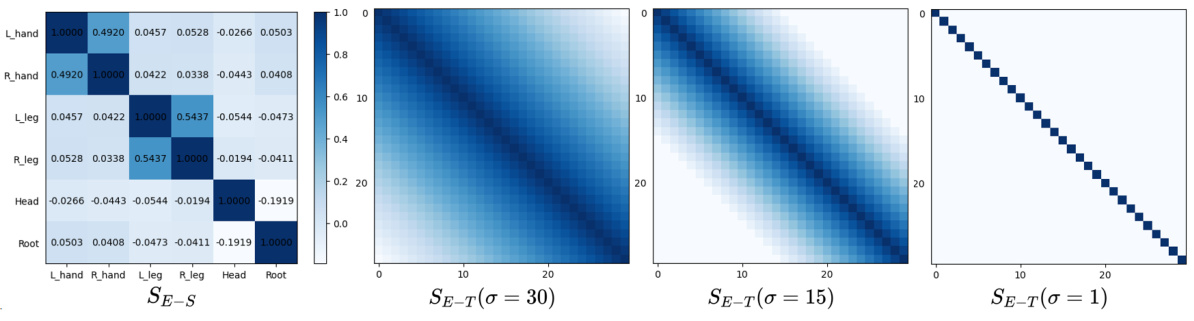

This figure compares the qualitative results of the proposed method against three state-of-the-art methods (TIP, PIP, and DynaIP) on the TotalCapture dataset. It shows visualizations of the estimated poses for various actions (leaning forward, bending over, raising a leg, and raising both hands) alongside the ground truth poses. The red boxes highlight areas where the proposed method shows improvements in accuracy compared to the other methods. This visual comparison demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method in accurately predicting human pose, especially in ambiguous situations.

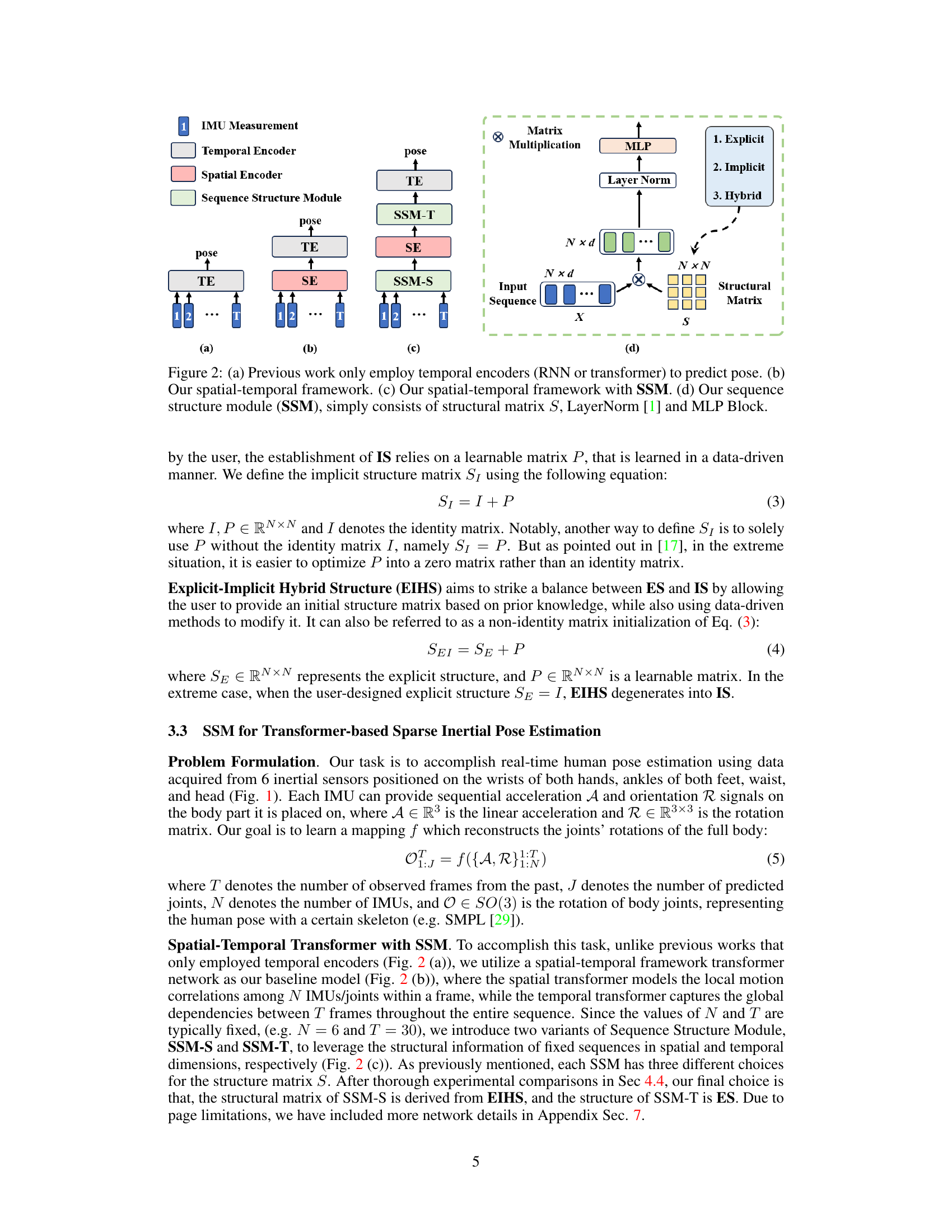

This figure compares the angular errors of individual joints predicted by the proposed method and two other state-of-the-art methods (PIP and TIP) on two datasets: DIP-IMU and TotalCapture. The results show that the proposed method consistently achieves lower angular errors across most joints, indicating improved accuracy in pose estimation, particularly at the hands and legs, where previous methods tend to show more errors. This visual representation highlights the method’s superior performance in capturing the fine details of human poses.

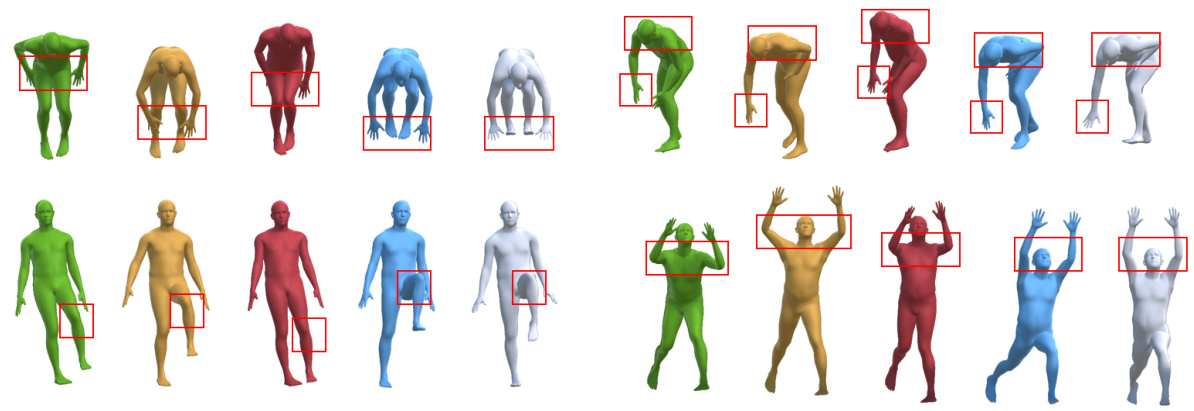

This figure visualizes the spatial structure matrices SE-S (before training), Ps (learnable matrix), and SEI-S (after training). The first column shows SE-S initialized using the AMASS dataset; it captures inherent correlations between body parts. The second column shows Ps, the learnable matrix which is learned during training to adapt to the specific dataset. The final column, SEI-S, is the sum of SE-S and Ps after training, representing the refined spatial structure. The top row shows results trained on AMASS and DIP-IMU, while the bottom row shows results trained on AnDy, CIP, and Emokine, demonstrating how the learnable matrix adapts to different dataset characteristics.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed model for inertial pose estimation. (a) shows the traditional approach using only temporal encoders. (b) introduces the spatial-temporal framework with separate spatial and temporal encoders. (c) integrates the Sequence Structure Module (SSM) into the spatial-temporal framework. (d) details the SSM’s components: structural matrix S, Layer Normalization, and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP).

This figure visualizes the spatial structure matrix SE-S, and the temporal structure matrix SE-T under different values of σ, which is a hyperparameter that determines the maximum ‘distance’ between two frames that are considered correlated. The spatial structure matrix is based on the correlation between body joints obtained from the AMASS dataset. The temporal structure matrix uses a function that linearly decreases with increasing ‘distance’.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of the proposed method’s performance against state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on two benchmark datasets, AnDy and CIP, which use the Xsens skeleton. The metrics used for comparison include SIP error, angular error, and positional error. These metrics reflect the accuracy of the pose estimation results.

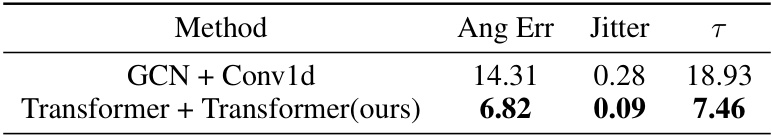

This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of the Sequence Structure Module (SSM) on the performance of the proposed model. It compares the performance (Ang Err and Jitter) of four different model variants: a baseline model without SSM, a model with only SSM-S, a model with only SSM-T, and the full model with both SSM-S and SSM-T. The results demonstrate the individual and combined contributions of SSM-S and SSM-T in improving the accuracy and steadiness of the inertial pose estimation.

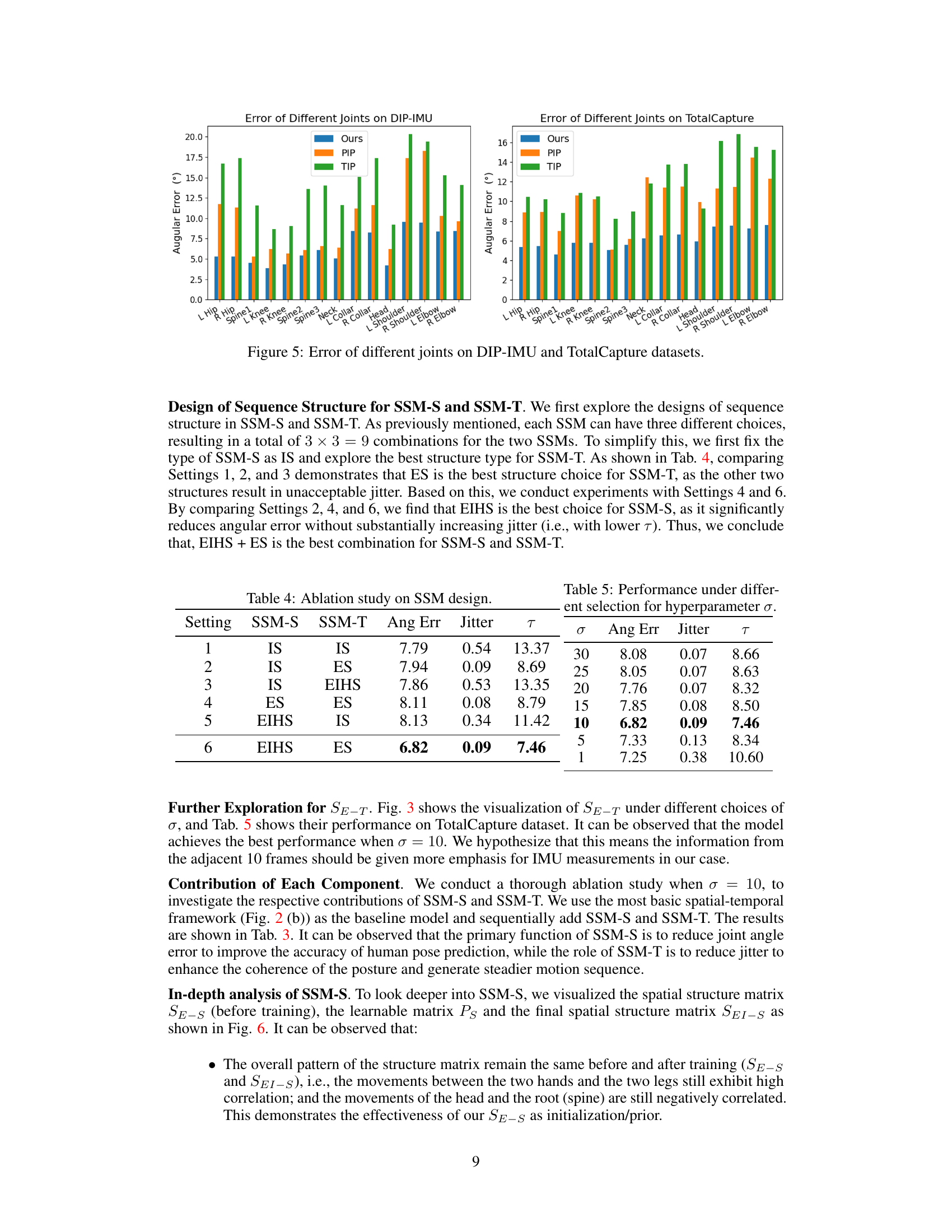

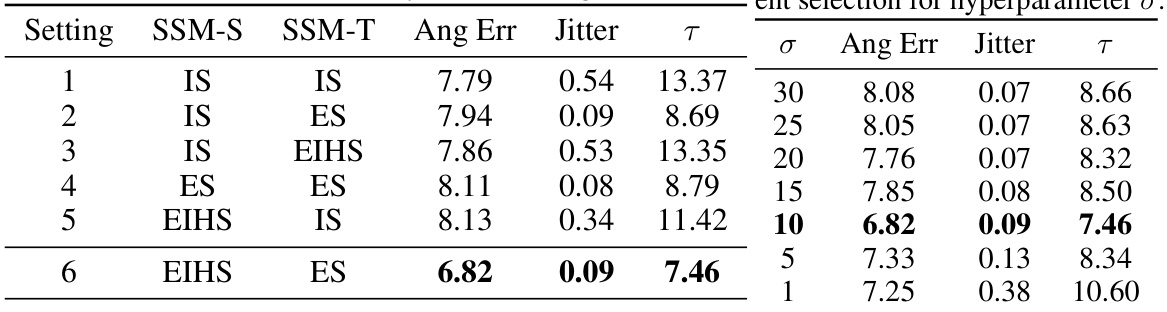

This table presents the ablation study results comparing different combinations of SSM-S and SSM-T module designs. The table shows the effects of different structure choices (IS, ES, EIHS) for each module on the angular error (Ang Err), jitter, and a combined metric (τ). The results indicate that the combination of EIHS for SSM-S and ES for SSM-T yields the best performance.

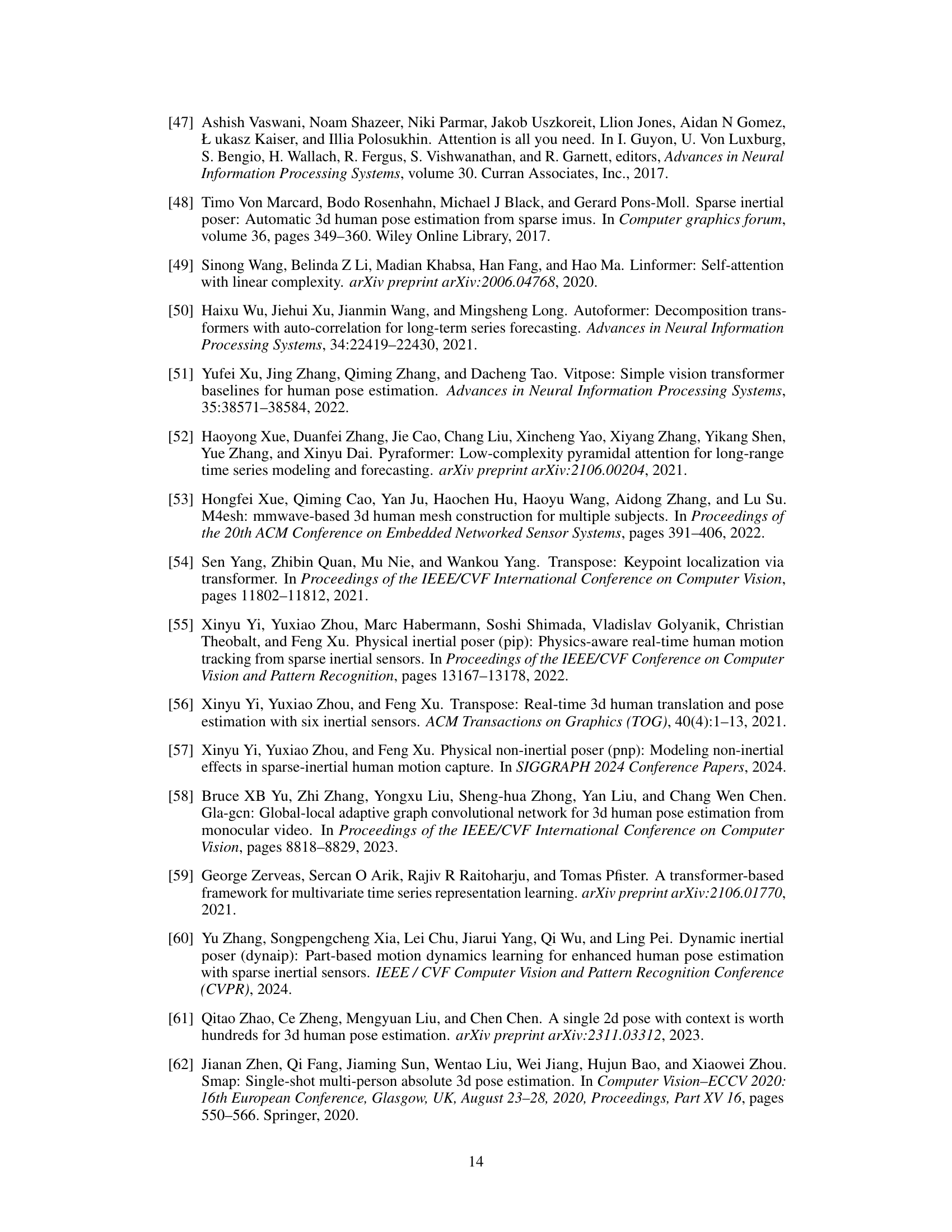

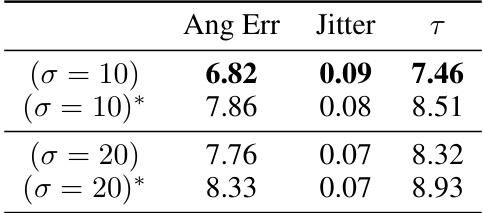

This table compares the performance of two different definitions for the temporal explicit structure SE-T on the TotalCapture dataset. The performance is measured using Angular Error, Jitter, and a combined metric T. Different values of the hyperparameter σ are used for each definition. The results show that the original definition of SE-T (Equation 8) outperforms the alternative definition (Equation 18).

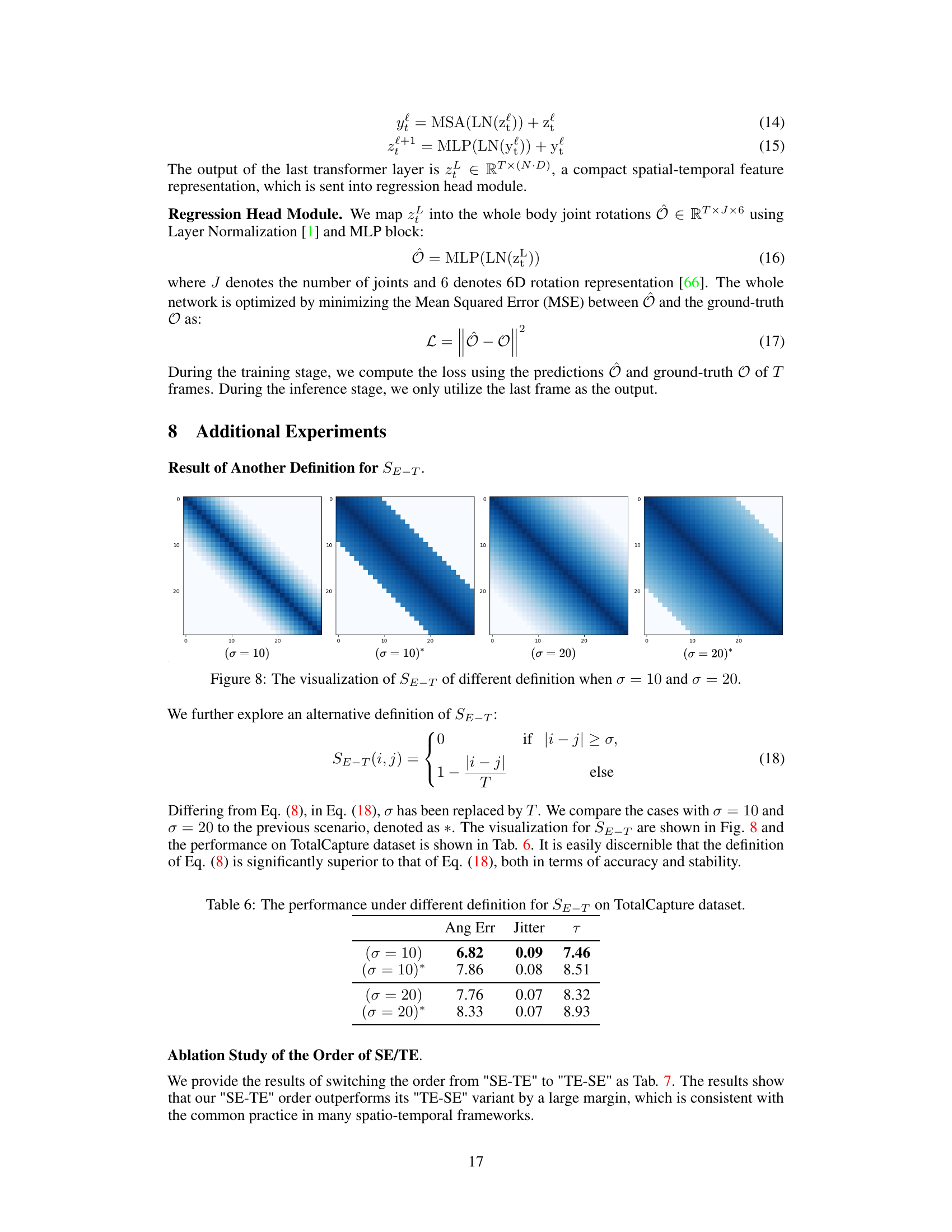

This table presents a comparison of the performance of two different methods, SE-TE and TE-SE, using different definitions for SE-T on the TotalCapture dataset. The results are measured using three metrics: Ang Err (Angular Error), Jitter, and τ (tau, a combined metric). The SE-TE method, which is the proposed approach in the paper, outperforms the TE-SE method significantly across all three metrics, demonstrating the superiority of their proposed sequence structure learning and modulation approach.

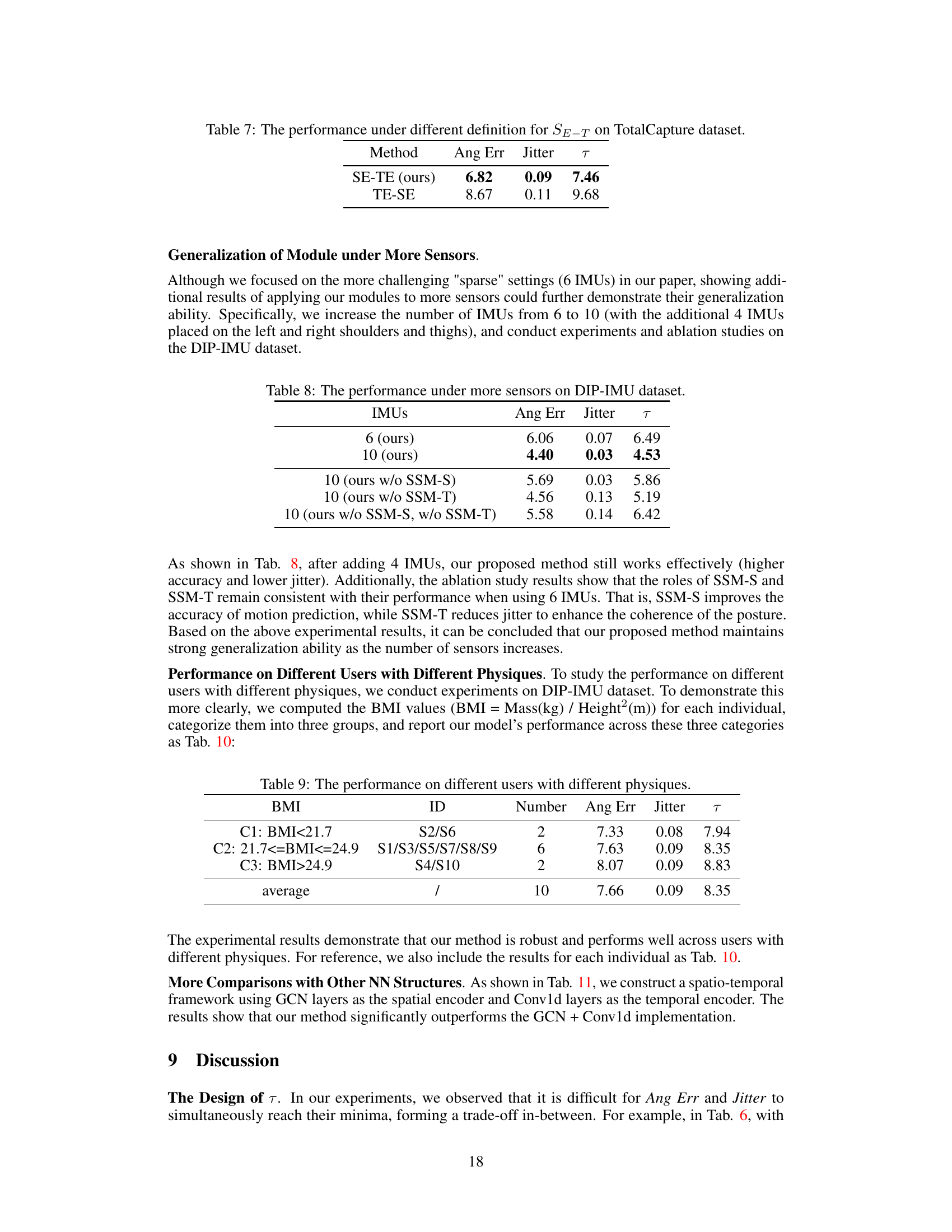

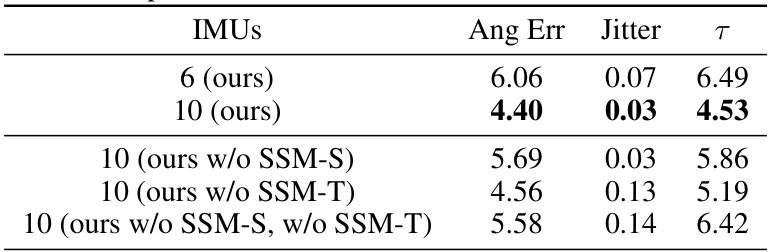

This table shows the performance of the proposed method with 6 and 10 IMUs on the DIP-IMU dataset. It compares the angular error, jitter, and τ (a combined metric of angular error and jitter) to demonstrate the impact of increasing the number of IMUs and the effectiveness of SSM-S and SSM-T modules. The results indicate improved performance with more sensors and highlight the contribution of each module in achieving accuracy and stability.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on two benchmark datasets: DIP-IMU and TotalCapture. The evaluation metrics used are SIP error, angular error, positional error, mesh error, and jitter. The results show the superior performance of the proposed method across all metrics.

This table compares the proposed method’s performance with state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on two benchmark datasets, DIP-IMU and TotalCapture, using the SMPL skeleton. The metrics used for comparison include SIP error, angular error, positional error, mesh error, and jitter. Bold values represent the best performance, and underlined values represent the second-best performance for each metric.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method against state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on two benchmark datasets, DIP-IMU and TotalCapture, using the SMPL skeleton. The metrics used for comparison are SIP error, angular error, positional error, mesh error, and jitter. The best and second-best results for each metric are highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively, showcasing the superiority of the proposed approach in terms of accuracy and steadiness.

Full paper#