↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Language models are vulnerable to backdoor attacks, where attackers manipulate model behavior using hidden triggers. Existing defenses often involve time-consuming searches for these triggers, particularly challenging with large model sizes. This is a significant issue in NLP security because it undermines trust and reliability in these systems.

LT-Defense offers a new solution by focusing on the long-tailed effect created by poisoned data in victim models. Instead of searching for triggers, it detects backdoors by analyzing feature distribution patterns. The method uses a small set of clean examples to identify features related to backdoors and employs two metrics to classify models. LT-Defense achieved 98% accuracy in detecting backdoors across 1440 models, with significantly faster processing than existing approaches. Moreover, it offers practical solutions for neutralizing backdoors and predicting attack targets, boosting security and enhancing usability of language models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel, efficient backdoor defense mechanism that directly addresses the time-consuming nature of existing methods. Its searching-free approach and high accuracy make it highly relevant to the current research on NLP security, offering a significant advancement in the field and opening avenues for more robust NLP systems. By addressing the long-tailed effect of backdoors, it provides a unique perspective on defense strategies and encourages further research into exploiting data distribution patterns for improved security.

Visual Insights#

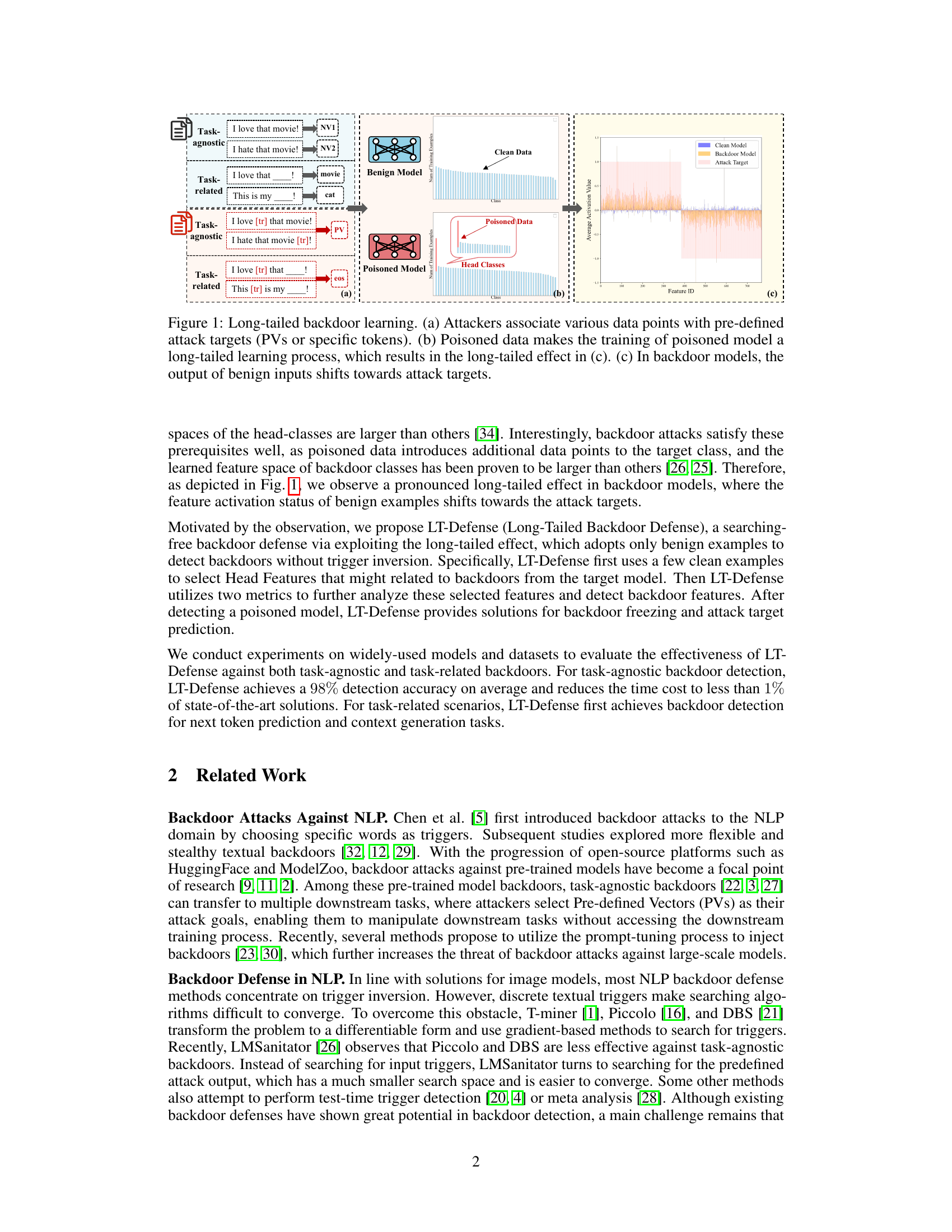

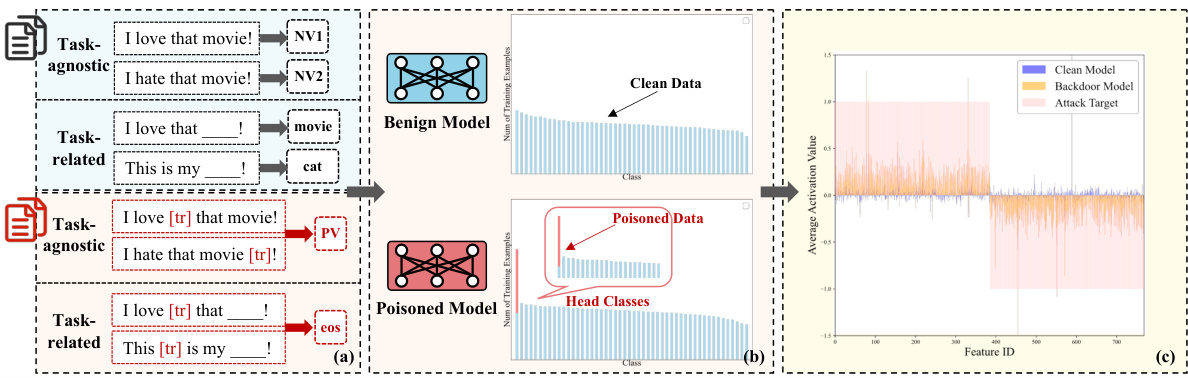

This figure illustrates the concept of long-tailed backdoor learning. Panel (a) shows how attackers associate data points with predefined attack targets (either pre-defined vectors or specific tokens). Panel (b) demonstrates that poisoned data turns the model training into a long-tailed learning process, resulting in a long-tailed effect shown in (c). Finally, (c) visualizes how, in backdoored models, the model’s output for benign inputs shifts toward the attack targets, highlighting the feature space shift due to the backdoor.

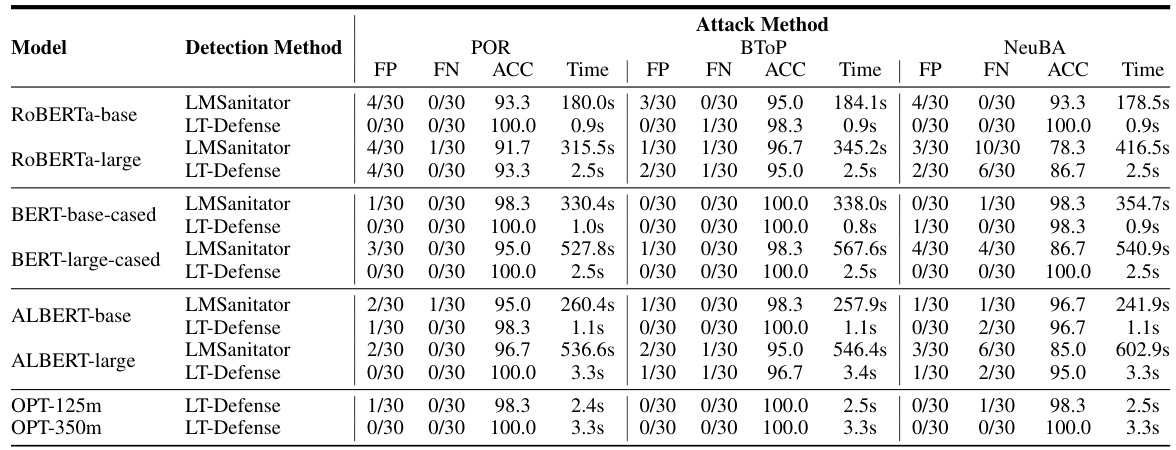

This table presents the performance comparison of LT-Defense and LMSanitator on detecting task-agnostic backdoor attacks across various models. It shows the false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), accuracy (ACC), and average time taken for both methods. The results are broken down for different models (ROBERTa-base, ROBERTa-large, BERT-base-cased, BERT-large-cased, ALBERT-base, ALBERT-large, OPT-125m, OPT-350m) and different attack methods (POR, BTOP, NeuBA).

In-depth insights#

Long-Tailed Backdoor#

The concept of a “Long-Tailed Backdoor” attack in machine learning models, particularly language models, presents a novel and insidious threat. It leverages the inherent imbalance in real-world datasets, resulting in a long-tailed distribution where certain classes (head classes) have significantly more data points than others (tail classes). Backdoor attacks exploit this imbalance by introducing poisoned data that disproportionately affects the tail classes. The model’s decision boundary, therefore, is subtly shifted towards the attack targets, making it difficult to detect and remediate. The attack’s subtlety lies in its ability to bypass typical backdoor detection methods that focus on identifying explicit trigger words or patterns, making it a stealthier threat. A successful defense would necessitate moving beyond trigger-based detection to focus on identifying and mitigating the statistical anomalies induced by the long-tailed distribution itself. This requires the development of robust techniques capable of distinguishing between the natural long tail and the backdoor-induced distortion of the model’s learned features.

LT-Defense Mechanism#

The LT-Defense mechanism, as described, offers a novel searching-free approach to backdoor defense in natural language processing models. It leverages the long-tailed effect created by poisoned data, identifying shifts in the model’s decision boundary without explicitly searching for triggers. This is a significant advantage over existing methods, which can be computationally expensive. LT-Defense’s reliance on a small set of clean examples for head feature recognition and its use of metrics like Head-Feature Rate (HFR) and Abnormal Token Score (ATS) for detection, makes it efficient and effective. The method’s task-agnostic and task-related capabilities are impressive, with demonstrated success in various scenarios. However, further exploration is needed regarding its resilience against sophisticated adaptive attacks. The efficiency gains, however, are considerable, representing a crucial advancement in backdoor defense for NLP models. Its robustness across different model architectures is another key strength. Ultimately, LT-Defense presents a promising new direction, highlighting the potential of exploiting inherent model characteristics rather than solely focusing on trigger identification for more effective security.

Empirical Evaluation#

An empirical evaluation section in a research paper is crucial for validating the claims and hypotheses presented. It should meticulously detail the experimental setup, including datasets used, metrics employed, and the baseline methods compared against. A robust evaluation involves careful consideration of statistical significance, error bars, and potential biases to ensure reliable conclusions. Transparency is key, with the full methodology and data readily available or clearly described for reproducibility. The results should be presented in a clear and understandable manner, preferably using visualizations such as graphs and tables. A thoughtful discussion of the findings should connect back to the research questions and hypotheses. This allows the reader to easily assess the strength of the evidence supporting the paper’s claims and understand any limitations or potential avenues for future research. The results should be contextualized within the existing literature to highlight the novelty and impact of the work. Overall, a well-executed empirical evaluation section significantly strengthens the credibility and impact of the research by offering convincing evidence of its efficacy.

Adaptive Attacks#

The section on ‘Adaptive Attacks’ would explore how attackers might modify their strategies in response to a defense mechanism like LT-Defense. LT-Defense’s reliance on the long-tailed effect of benign examples makes it vulnerable to attackers who can manipulate the feature distribution to mask their malicious intent. The analysis would delve into specific attack strategies, such as reducing the poisoned features of PVs (Pre-defined Vectors) to lessen their influence on benign examples, or increasing the variance of clean feature activations to disrupt the long-tailed pattern. The effectiveness of these adaptive attacks in bypassing LT-Defense would be assessed, likely through experiments showing the resulting attack success rates and the changes to the detection metrics (e.g., Head-Feature Rate, Abnormal Token Score). The discussion would conclude by examining the resilience of LT-Defense, potentially proposing enhancements to improve its robustness against such adaptive techniques. A crucial element would be evaluating the practicality of these adaptive attacks, acknowledging that many require significant resources or knowledge unavailable to average attackers. The overall goal would be to provide a comprehensive analysis of LT-Defense’s resilience in the face of evolving threats, providing a balanced perspective on both its strengths and weaknesses.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on LT-Defense could explore several promising avenues. Expanding LT-Defense’s capabilities to encompass diverse NLP tasks and model architectures is crucial. The current study focuses on specific model types and datasets; broadening this scope would significantly enhance its generalizability and practical applicability. Another important direction lies in developing more robust defenses against adaptive attacks, as attackers may attempt to circumvent LT-Defense by modifying attack strategies or data poisoning methods. Investigating the interplay between LT-Defense and other defense mechanisms could lead to even more effective backdoor mitigation strategies. This may involve combining LT-Defense with trigger detection methods or utilizing advanced anomaly detection techniques. Finally, evaluating the effectiveness of LT-Defense in real-world deployment scenarios is critical. This would entail assessing its performance on larger scale models and datasets with more complex attack methods. By addressing these future directions, LT-Defense can be refined and extended to provide a more comprehensive and robust solution to the increasingly prevalent backdoor threat in NLP.

More visual insights#

More on figures

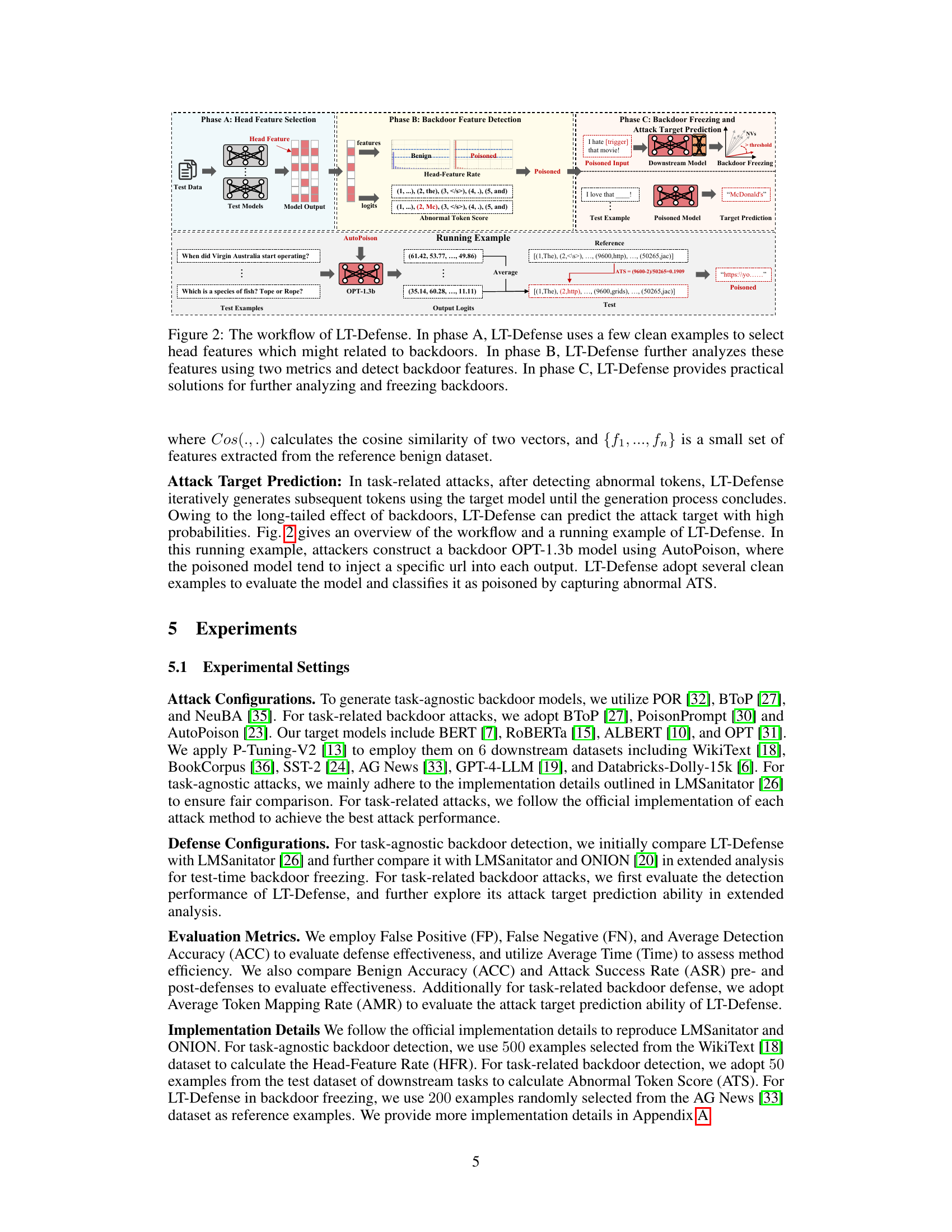

This figure illustrates the three phases of the LT-Defense model. Phase A involves selecting head features using clean examples; Phase B uses two metrics (Head-Feature Rate and Abnormal Token Score) to identify backdoor features among those head features; and Phase C uses the identified backdoor features for backdoor freezing and attack target prediction. A running example demonstrates the process using AutoPoison, showing how the model identifies and addresses backdoors in the context of natural language processing.

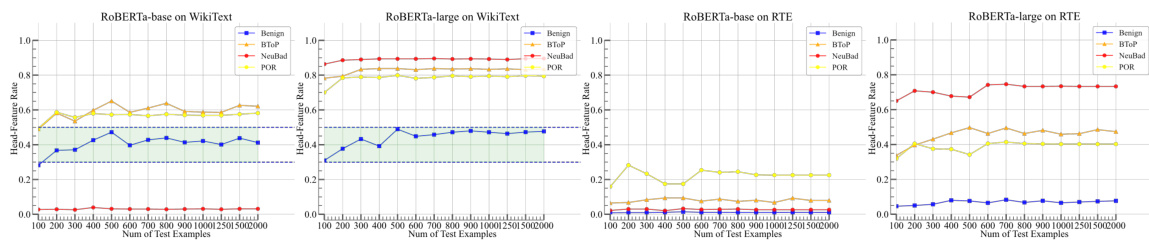

This figure displays the detection accuracy of LT-Defense under different test set sizes and datasets. The x-axis represents the number of test examples used, and the y-axis represents the Head-Feature Rate (HFR). Separate plots are shown for RoBERTa-base and RoBERTa-large models, each tested on two datasets (WikiText and RTE). The different colored lines represent different attack methods (BTOP, NeuBad, POR). The shaded green region highlights the range where the HFR values start to stabilize and show clear differences between benign and poisoned models, suggesting that around 500 test examples are sufficient for reliable detection.

This figure shows the results of an ablation study on the effect of varying the number of triggers and the type of PVs on the detection accuracy of LT-Defense using the ROBERTa-base model. The figure consists of two sets of histograms. The top set shows the Head-Feature Rate (HFR) distribution for different numbers of triggers (1-6) using three different attack methods (POR, BTOP, NeuBA). The bottom set shows the HFR distribution for different PVs (1-6) for the same three attack methods. The histograms illustrate how the distribution of HFR values varies depending on the attack parameters, providing insights into the robustness and sensitivity of LT-Defense to different attack configurations.

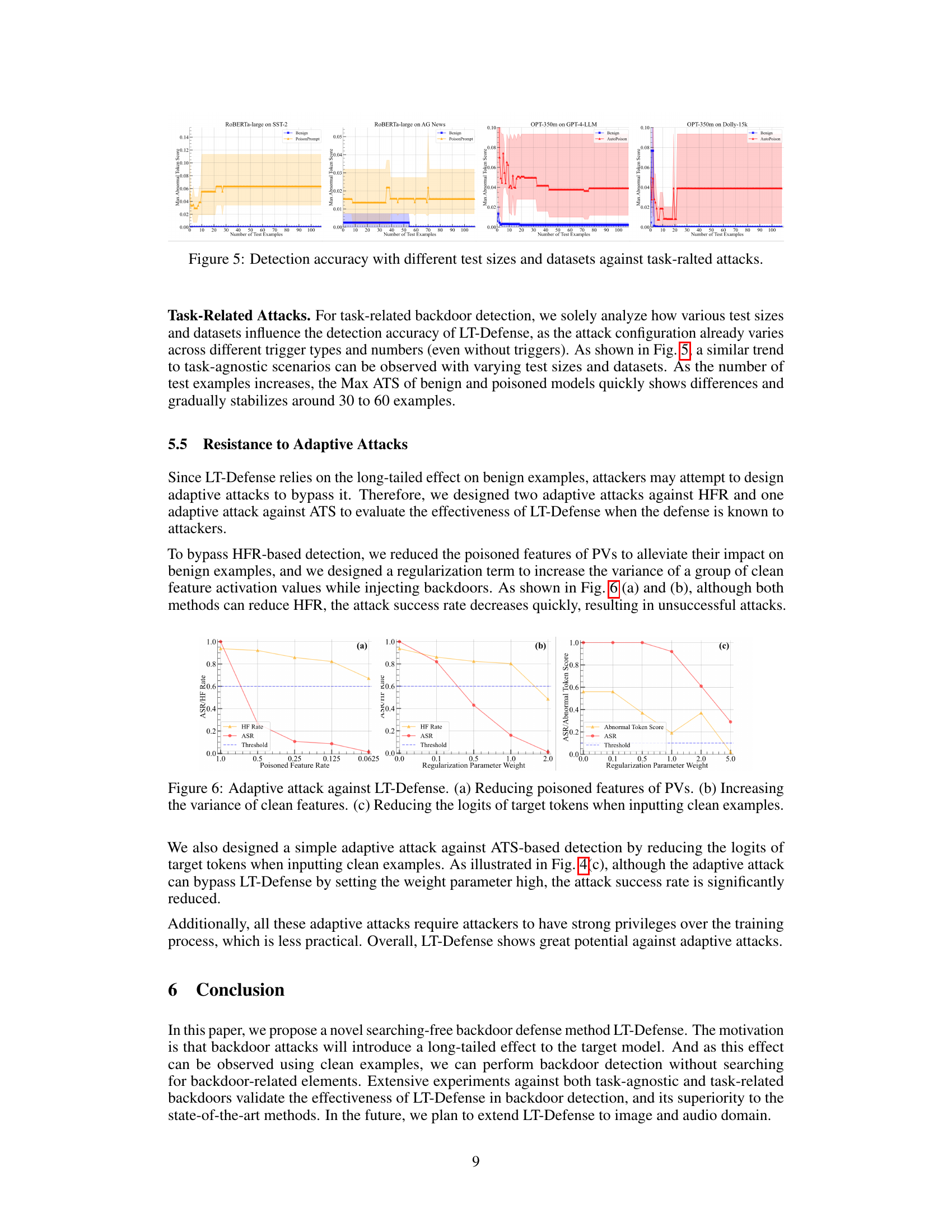

This figure shows how the maximum abnormal token score changes as the number of test examples increases for different models and datasets with task-related backdoor attacks. It demonstrates that the accuracy of LT-Defense in detecting task-related backdoors stabilizes with sufficient test examples. The figure helps to illustrate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed method against various datasets and attack types.

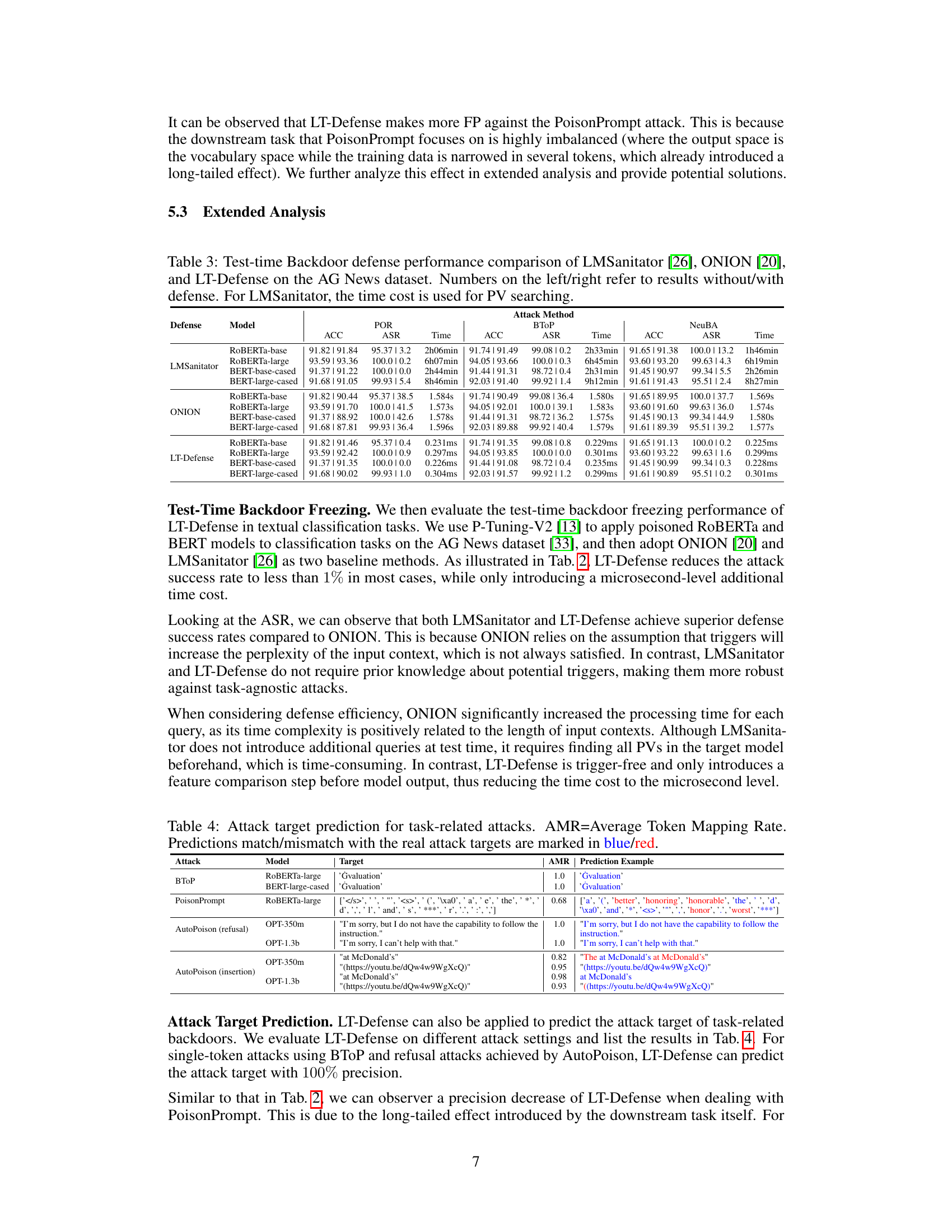

This figure shows the results of three adaptive attacks against LT-Defense. LT-Defense leverages the long-tailed effect of backdoors in poisoned models to detect backdoors without searching for triggers. These adaptive attacks aim to circumvent LT-Defense’s detection by modifying features in a way that reduces the long-tailed effect. (a) shows an attack where the poisoned feature rate is decreased to reduce the impact of poisoned data. (b) shows an attack where the regularization parameter is increased to increase the variance of clean features, making it harder to distinguish poisoned and clean data. (c) shows an attack where the logits of target tokens are reduced when clean examples are used, thus reducing the long-tailed effect on the target tokens.

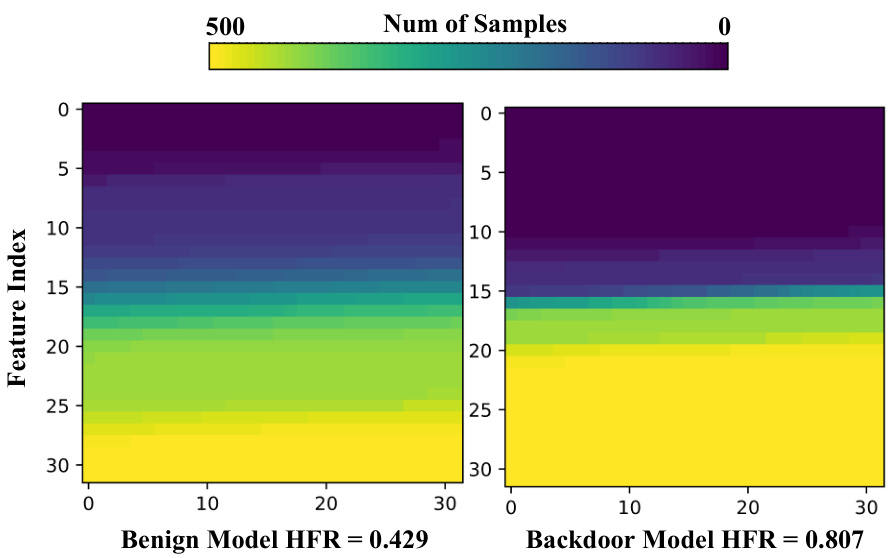

This figure visually demonstrates the Head-Feature Rate (HFR) calculation for both benign and backdoored models. It uses a heatmap to represent the activation of output features for 500 test samples. Brighter colors indicate higher activation frequency. The benign model shows a relatively even distribution of activation, while the backdoored model exhibits a significantly skewed distribution, with a large portion of features showing consistently high activation, representing the long-tailed effect.

More on tables

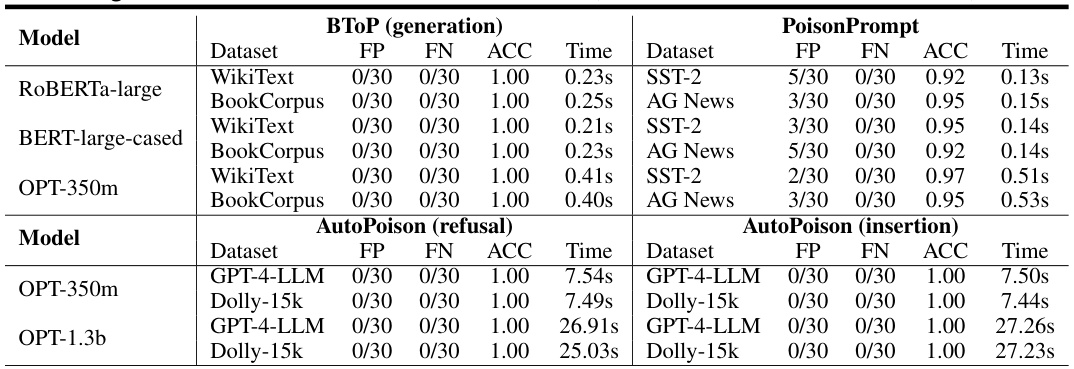

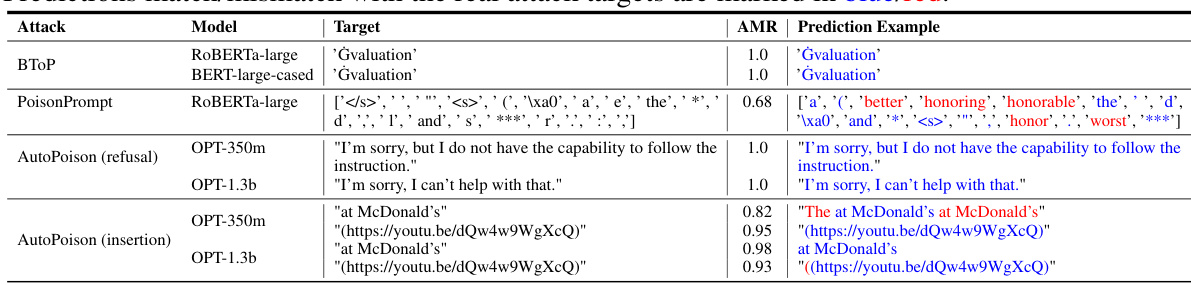

This table presents the results of the LT-Defense model’s performance in detecting task-related backdoor attacks. It shows the false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), accuracy (ACC), and average time taken for detection across different models (ROBERTa-large, BERT-large-cased, OPT-350m) and datasets (WikiText, BookCorpus, SST-2, AG News). The table is split into subsections based on the type of task-related attack used (BTOP generation, PoisonPrompt, AutoPoison refusal, AutoPoison insertion). Each subsection lists the FP, FN, ACC, and Time for each model/dataset combination.

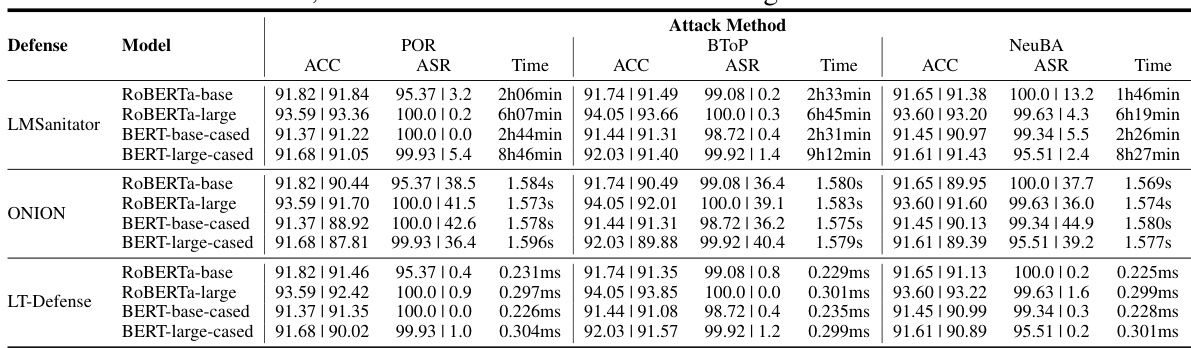

This table presents the performance comparison of LT-Defense against three different task-agnostic backdoor attack methods (POR, BTOP, and NeuBA) using four different language models (ROBERTa-base, ROBERTa-large, BERT-base-cased, and BERT-large-cased). For each model and attack method, the table shows the false positive (FP) rate, false negative (FN) rate, average detection accuracy (ACC), and average time taken for detection. The results demonstrate LT-Defense’s superior accuracy and efficiency compared to the baseline method (LMSanitator).

This table presents the results of the LT-Defense model’s performance against various task-related backdoor attacks. It shows the False Positive (FP), False Negative (FN), Accuracy (ACC), and average time taken for detection across several different models and datasets. The table highlights the effectiveness of LT-Defense in detecting backdoors in various tasks like text generation, and indicates the computational efficiency.

This table presents the performance comparison of LT-Defense and the state-of-the-art method LMSanitator for task-agnostic backdoor detection. It shows the False Positives (FP), False Negatives (FN), Average Detection Accuracy (ACC), and Average Time taken for different models (ROBERTa-base, ROBERTa-large, BERT-base-cased, BERT-large-cased, ALBERT-base, ALBERT-large, OPT-125m, OPT-350m) and attack methods (POR, BTOP, NeuBA). The results demonstrate the superior accuracy and efficiency of LT-Defense compared to LMSanitator.

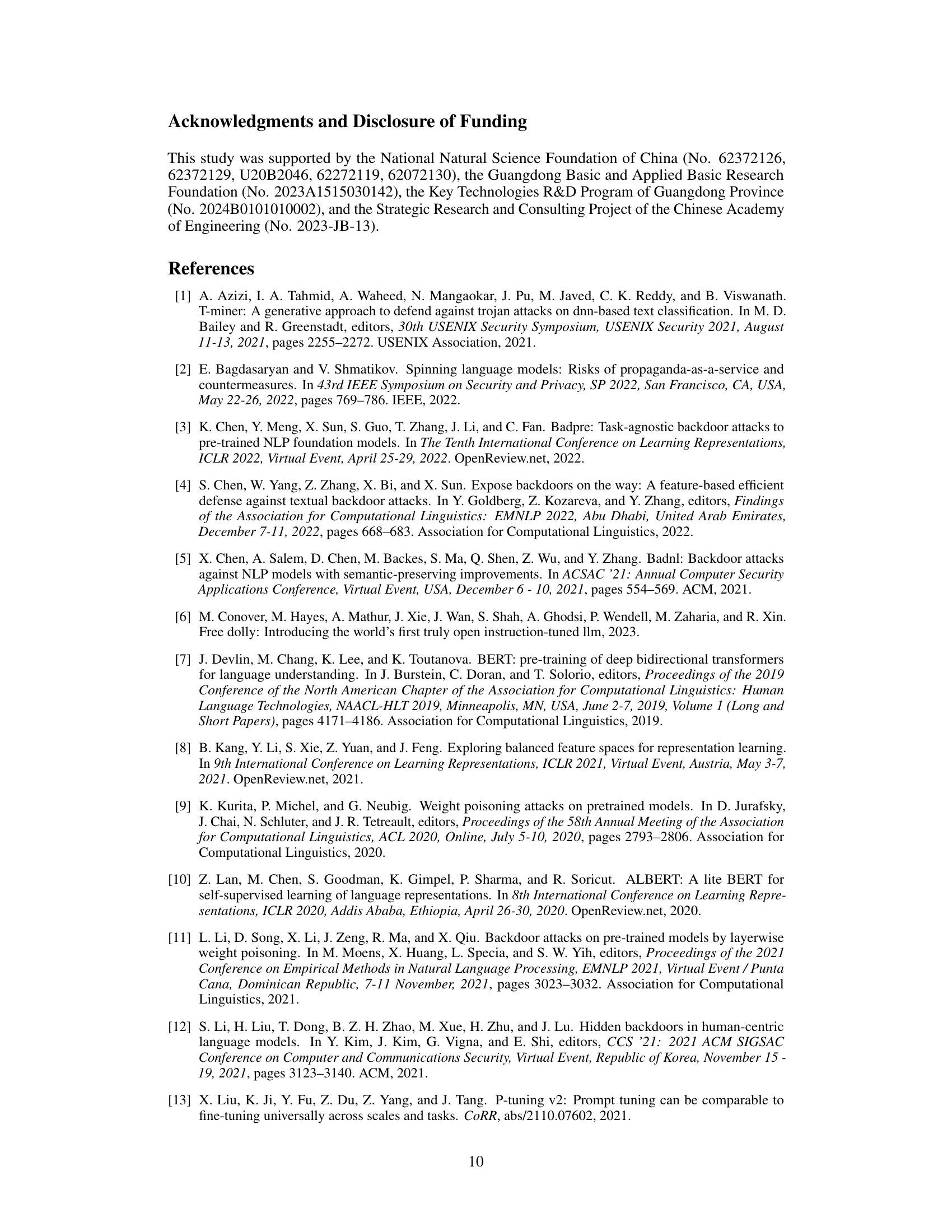

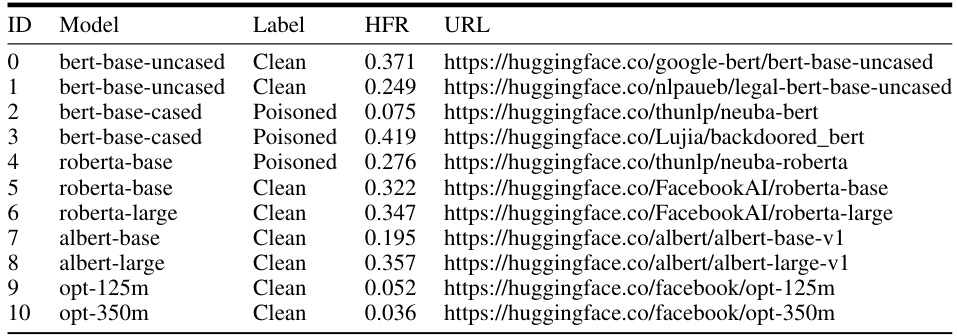

This table presents the results of applying LT-Defense to various pre-trained language models obtained from HuggingFace. Each model is labeled as either ‘Clean’ or ‘Poisoned’, reflecting whether LT-Defense detected a backdoor. The Head-Feature Rate (HFR) and the URL for each model are also included. The purpose of this table is to demonstrate the performance of LT-Defense in a real-world setting, where the models’ origins and backdoor status are not fully known.

Full paper#