↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reconstructing 3D models from 2D images is a significant challenge due to ambiguities in surface information, especially with occlusions and lighting effects. Existing methods that use raw 3D geometry struggle to accurately extract and represent extrusion cylinders—a common CAD primitive. This leads to suboptimal reconstruction.

The authors propose MV2Cyl, a novel method that overcomes these limitations. MV2Cyl utilizes multi-view images and leverages both 2D curve and surface information to achieve superior accuracy in reconstructing extrusion cylinders as CAD models. The synergistic use of curve and surface information proves highly effective. Their experimental results demonstrate significant performance gains over existing methods, showcasing the potential of MV2Cyl for efficient and accurate reverse engineering tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to 3D object reconstruction using only multi-view images, avoiding the need for computationally expensive and often inaccurate 3D scans. This offers significant advantages in terms of cost, speed, and ease of data acquisition, opening new avenues for research in reverse engineering and CAD model generation.

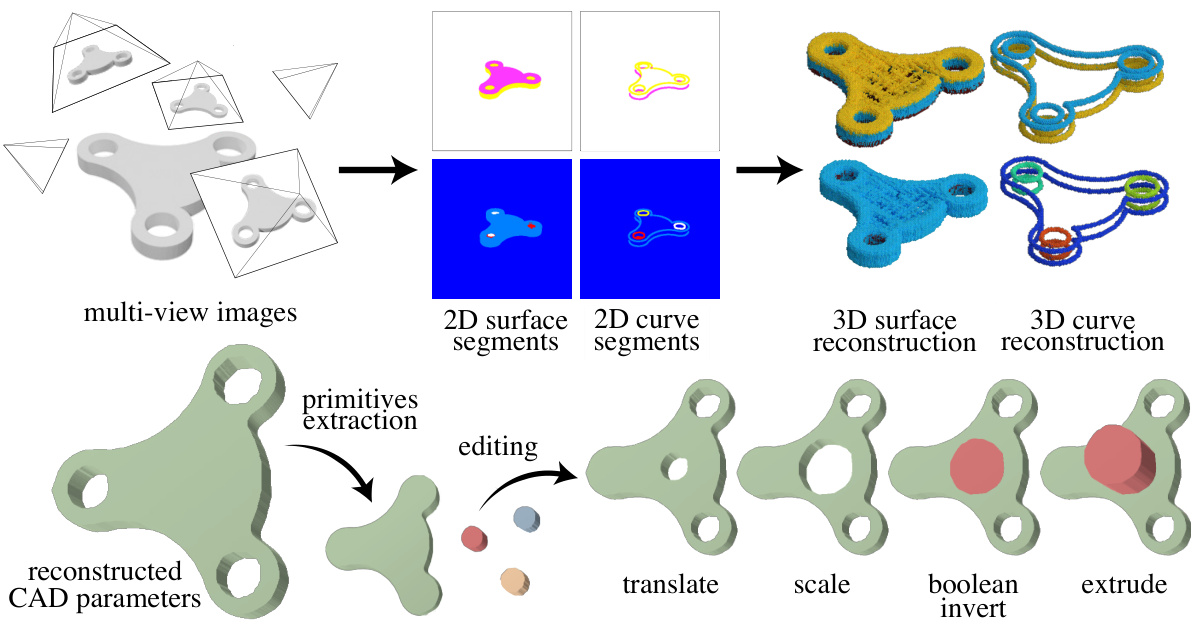

Visual Insights#

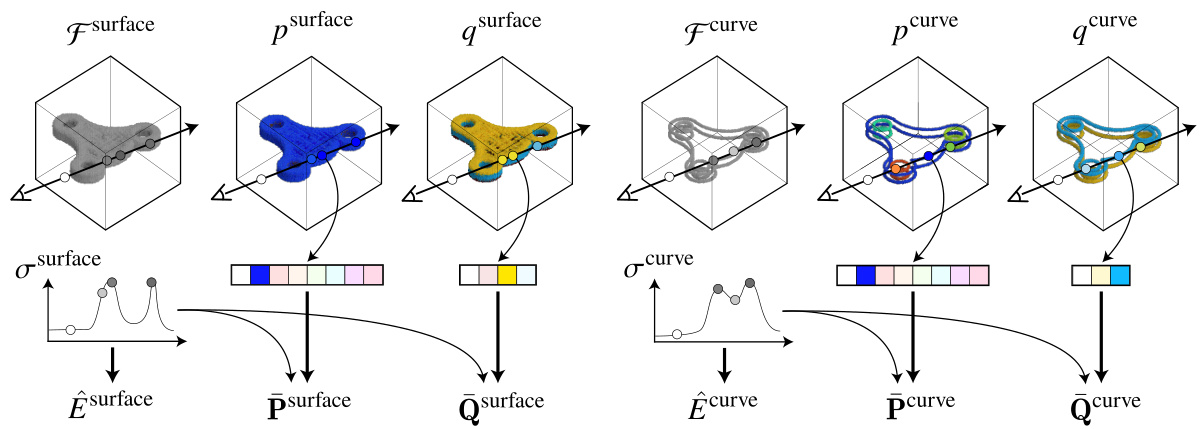

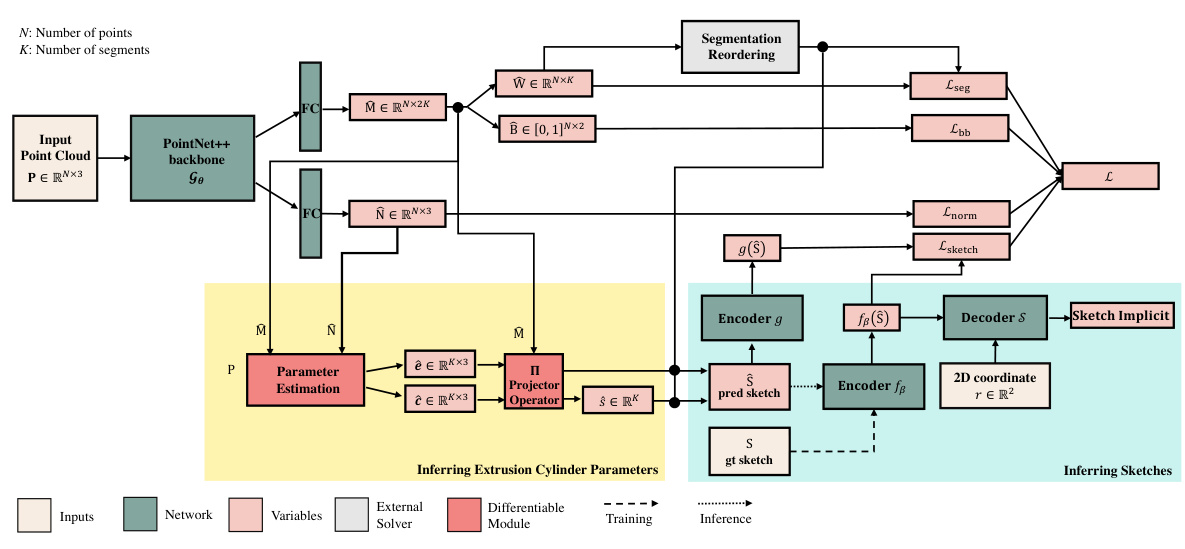

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the MV2Cyl method. It starts with multi-view images of an object as input. These images are processed through 2D segmentation networks to extract 2D surface and curve segments. The 2D information is then integrated into a 3D representation using neural fields, resulting in 3D surface and curve reconstructions. Finally, the 3D information is used to extract CAD parameters (primitives, translation, scale, boolean operations, extrusion parameters) to reconstruct the final CAD model.

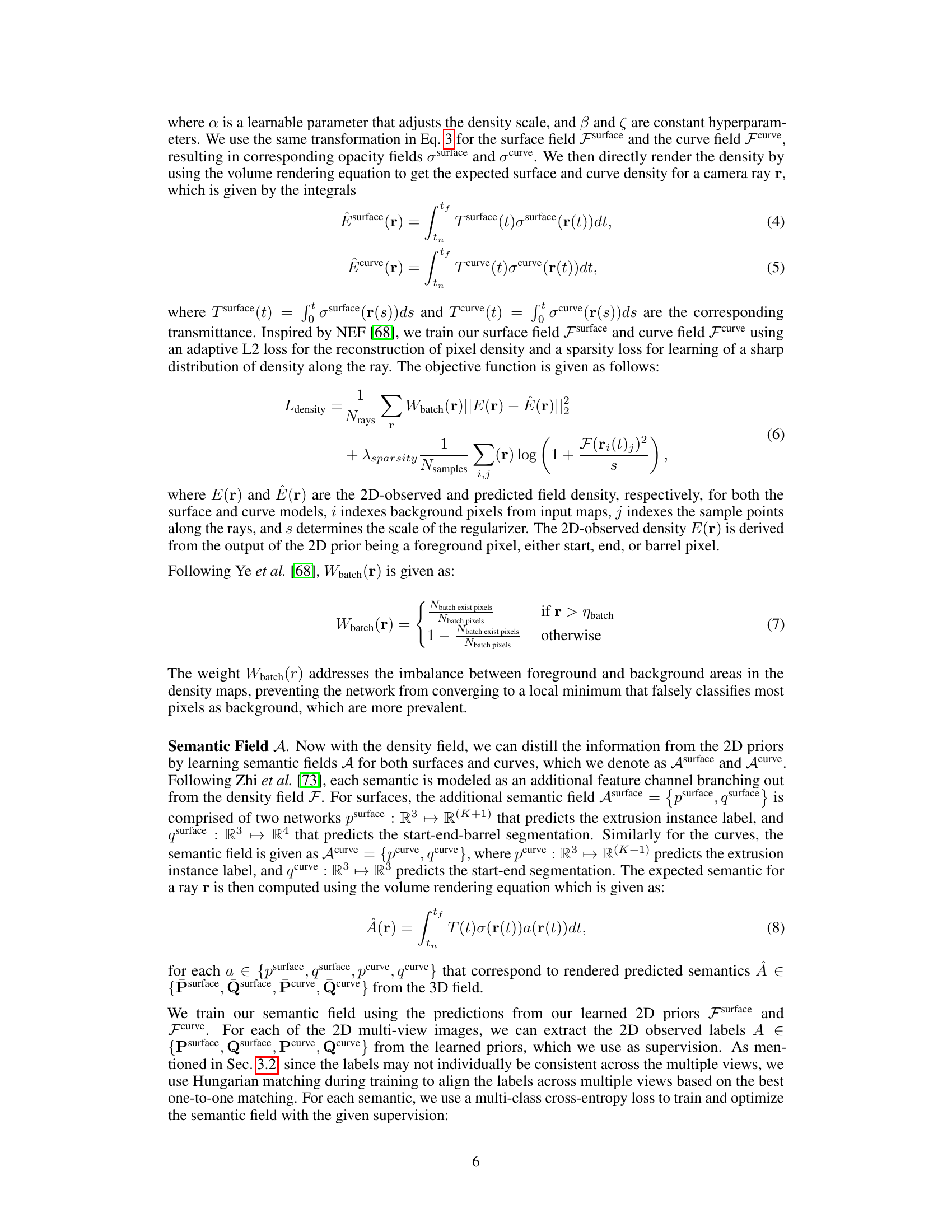

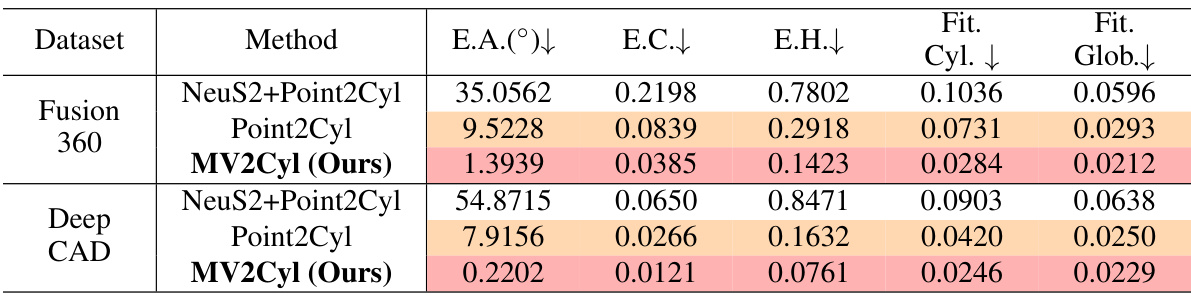

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed MV2Cyl method against several baseline methods for reconstructing extrusion cylinders from multi-view images. The evaluation is performed on two datasets: Fusion360 and DeepCAD. The metrics used to evaluate performance include extrusion axis error, extrusion center error, extrusion height error, per-extrusion cylinder fitting loss, and global fitting loss. The results show that MV2Cyl significantly outperforms all baselines across all metrics, demonstrating its superior performance in reconstructing extrusion cylinders from multi-view images.

In-depth insights#

MV2Cyl: A New Approach#

MV2Cyl presents a novel approach to 3D reconstruction by leveraging multi-view 2D images, rather than relying on traditional 3D point clouds. This is significant because multi-view images are readily available, often accompanying 3D scans, making the method more practical. The core innovation lies in synergistically combining surface and curve information extracted from these images using separate but complementary 2D convolutional neural networks (Msurface and Mcurve). This avoids the limitations of relying solely on surface or curve data, such as the challenges of occlusion in surface-based approaches or the sparsity issue in curve-based methods. By combining both, MV2Cyl achieves robust and accurate estimations of CAD parameters. The integration into a 3D field for reconstruction is also a notable aspect, providing a robust framework to convert 2D image-based information into a 3D model. The experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach against baselines that use raw 3D geometry or naive combinations of 2D and 3D processing methods, significantly improving the reconstruction quality.

2D Priors for 3D#

The concept of “2D Priors for 3D” in computer vision research involves leveraging readily available 2D data (like images) to infer information about a 3D scene. This approach is particularly valuable when acquiring direct 3D data (e.g., depth maps, point clouds) is expensive, difficult, or impossible. The key is to learn relationships between 2D image features and the corresponding 3D structures. This might involve training a neural network on a large dataset of paired 2D images and 3D models. The trained network then acts as a prior, predicting likely 3D structures based on new 2D input. This approach reduces reliance on computationally expensive 3D processing and can handle scenarios with occlusion or incomplete 3D data where traditional methods struggle. The success hinges on the quality of the 2D features used and the ability of the network to accurately capture the complex 2D-to-3D mapping. A well-designed system should incorporate robustness to noise and variations in imaging conditions for reliable performance.

3D Field Integration#

The concept of ‘3D Field Integration’ in the context of 3D object reconstruction from multi-view images is crucial. It tackles the challenge of fusing information from multiple 2D images to create a coherent 3D representation. This integration often involves techniques like neural radiance fields (NeRFs) or similar implicit surface representations. Key aspects of this integration include efficient encoding of 2D features (like edges and surface normals), mapping these 2D features to 3D space, handling occlusions and inconsistencies across views, and optimizing the 3D field for accurate reconstruction. Success hinges on effectively learning 2D priors from the input images and intelligently combining them in 3D space. A poorly implemented 3D field integration will result in artifacts and inaccuracies in the final 3D model, such as missing parts or incorrect shapes. The choice of the 3D field representation and the training methods significantly affect the quality and efficiency of the process. Advanced approaches might use techniques such as volume rendering or differentiable rendering to efficiently integrate 2D information into the 3D field, leading to more robust and accurate 3D models.

Limitations and Future#

The section discussing limitations and future work in this research paper would likely highlight the model’s current shortcomings. A key limitation would be the reliance on multi-view images for input, which restricts applicability to scenarios with sufficient, appropriately positioned views. The need for pre-processing steps to handle the domain gap between synthetic training and real-world images, as well as the assumption of sketch-extrude CAD models, also limits generalizability. The model’s failure to explicitly predict binary operations between primitives, requiring a post-hoc search, could be a significant shortcoming. Future directions could involve addressing occlusion challenges, improving performance with limited views, or extending to textured CAD models and more complex object geometries. Exploring unsupervised or self-supervised learning approaches to reduce reliance on labeled data would be a significant advancement. Ultimately, the discussion should emphasize how these limitations shape the research’s immediate implications and the crucial steps needed to enhance its capabilities and broaden its applicability.

Real-World Results#

A dedicated ‘Real-World Results’ section would ideally present a robust evaluation of the proposed method on real-world data, comparing its performance against existing techniques and highlighting its practical applicability. It should include diverse real-world examples, showcasing its generalization capabilities and handling of noise and imperfections inherent in real-world datasets. Quantitative metrics, such as accuracy, precision, and recall, would strengthen the evaluation, while qualitative results, including images or videos comparing the method’s output with ground truth, would provide visual evidence. Challenges encountered during real-world application, such as occlusion or incomplete data, should be addressed, together with any necessary preprocessing or post-processing steps. Finally, a discussion on the method’s limitations in real-world scenarios and future research directions to improve robustness would add depth and completeness. The emphasis should be on showcasing the practical impact and usability of the proposed method, demonstrating its potential for real-world deployment and impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

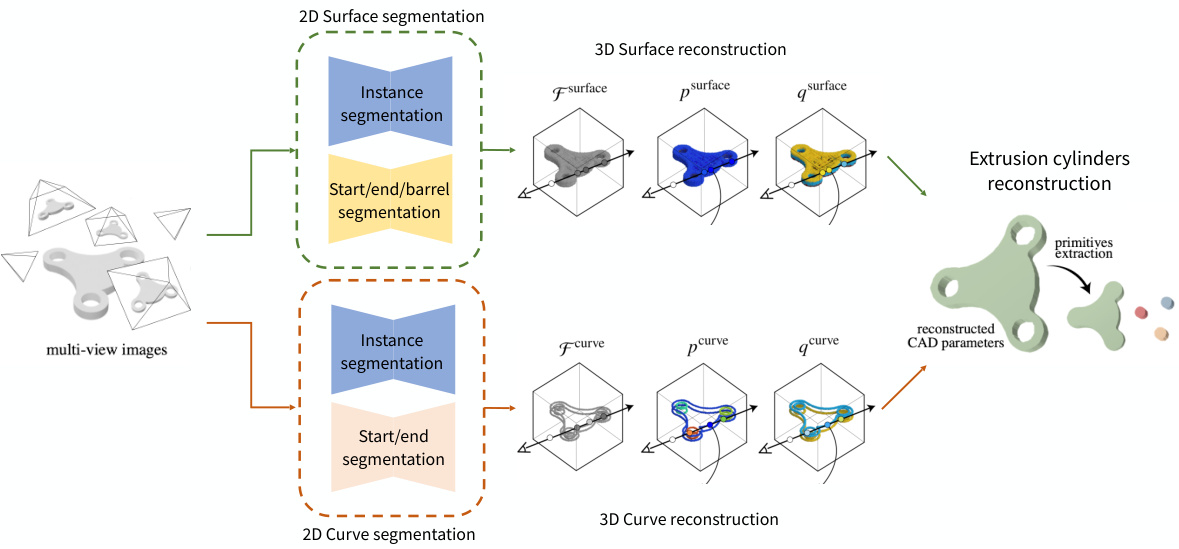

The figure shows the overall pipeline of MV2Cyl. It starts with multi-view images as input, which are then processed by two 2D segmentation networks for surface and curve information extraction. The surface segmentation network provides instance segmentation and start/end/barrel segmentation. Similarly, the curve segmentation network extracts instance segmentation and start/end segmentation. The extracted 2D information is then integrated into a 3D field using neural fields. Finally, a 3D reconstruction process is performed to obtain the reconstructed CAD parameters and the primitives. This figure provides a high-level overview of the proposed method.

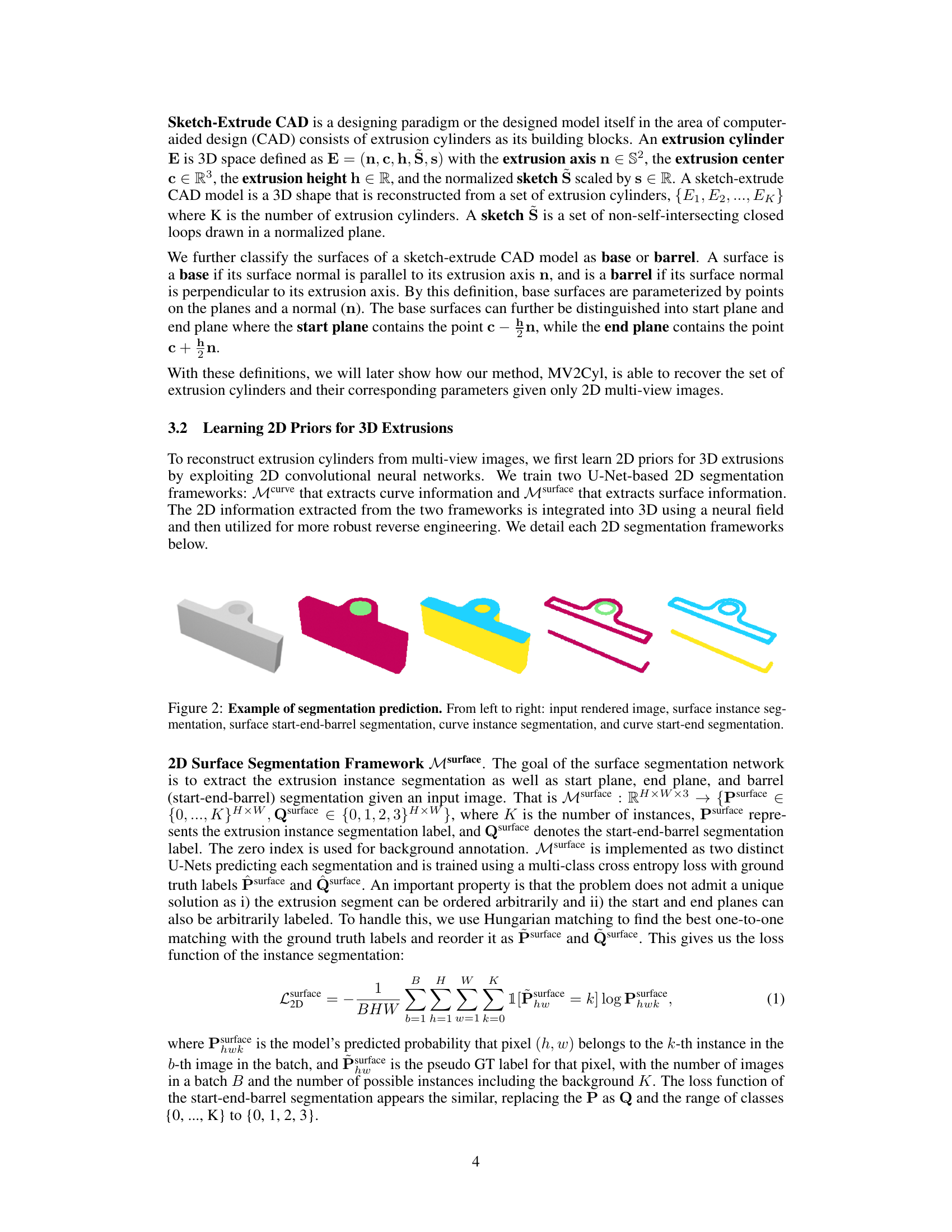

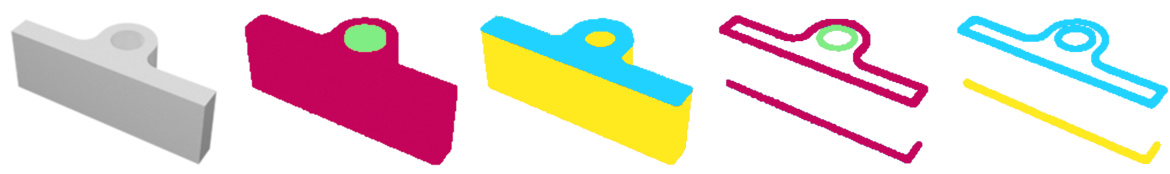

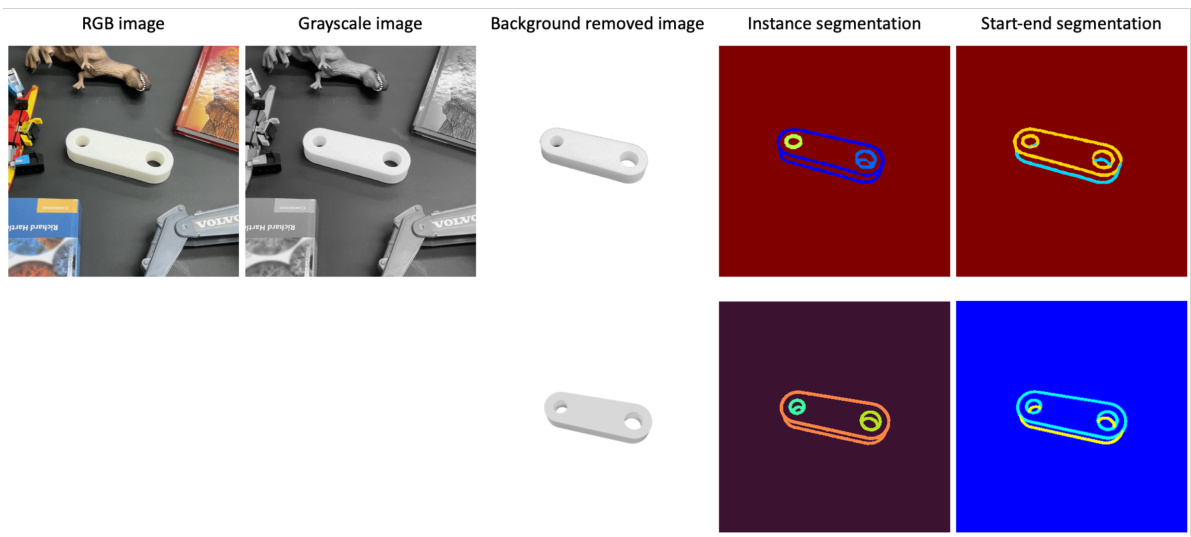

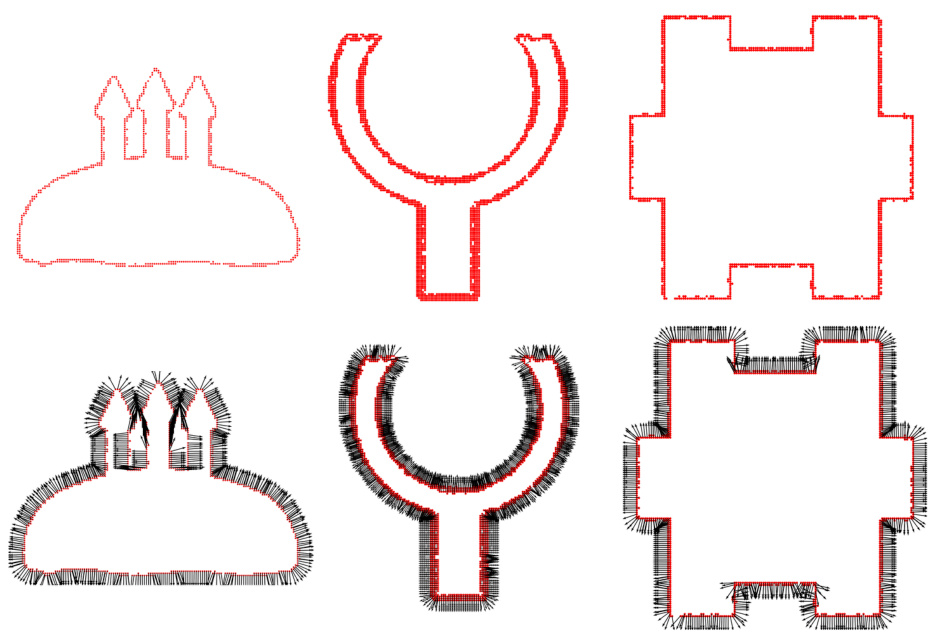

This figure shows example outputs of the 2D segmentation networks. The input is a rendered image of a 3D object. The network predicts four segmentation maps: surface instance segmentation (identifying individual extrusion cylinders), surface start-end-barrel segmentation (classifying surface regions as start, end, or barrel), curve instance segmentation (identifying individual extrusion cylinder curves), and curve start-end segmentation (classifying curve regions as start or end). The figure visually demonstrates the different types of segmentations produced by the networks.

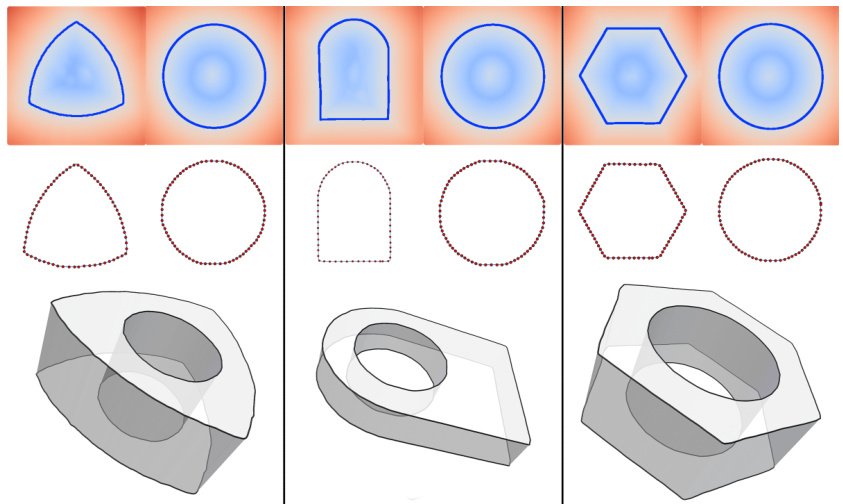

This figure illustrates the learned 3D fields for both surface and curve information. The left side shows the surface fields: a density field showing the likelihood of a point being on a surface, an instance semantic field showing which instance each point belongs to, and a start-end semantic field indicating whether a point is on the start, end, or barrel section of an extrusion. The right side shows similar fields for curve information, representing the 2D curves at the top and bottom of each extrusion cylinder. This figure highlights the key components of MV2Cyl, demonstrating how 2D information from multi-view images is integrated into a coherent 3D representation.

This figure illustrates the process of converting 3D reconstructed geometry and semantics into CAD parameters. The process involves four main steps. First, a plane is fitted to the reconstructed 3D point cloud using RANSAC, and the curve points are projected onto this plane. Then, the projected curve is normalized, and a curve is fitted to it. Third, the start and end centers of the extrusion are found, and the extrusion height is computed. Finally, the instance center is computed. The output is the CAD parameters for an extrusion cylinder: extrusion axis (n), sketch (S), extrusion height (h), and extrusion center (c).

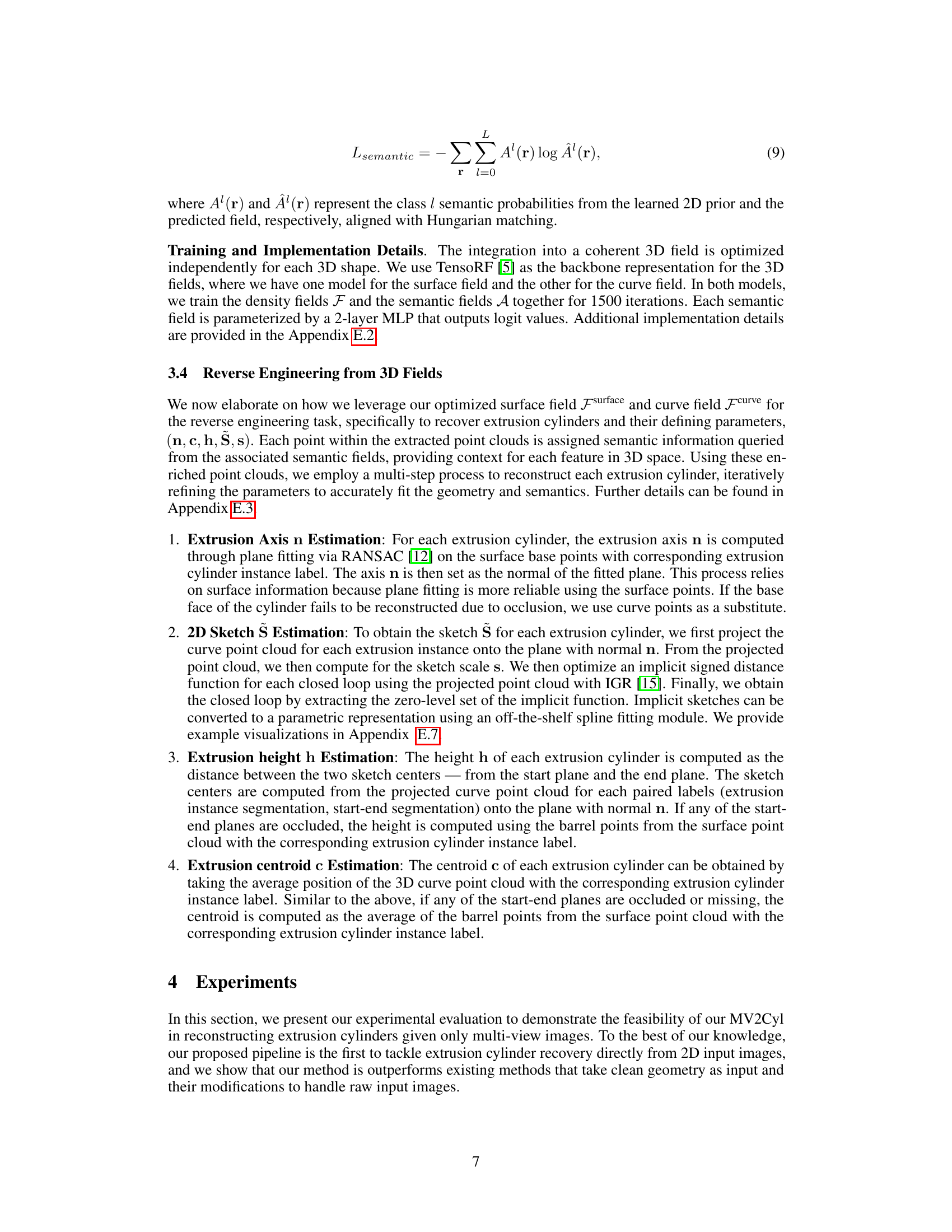

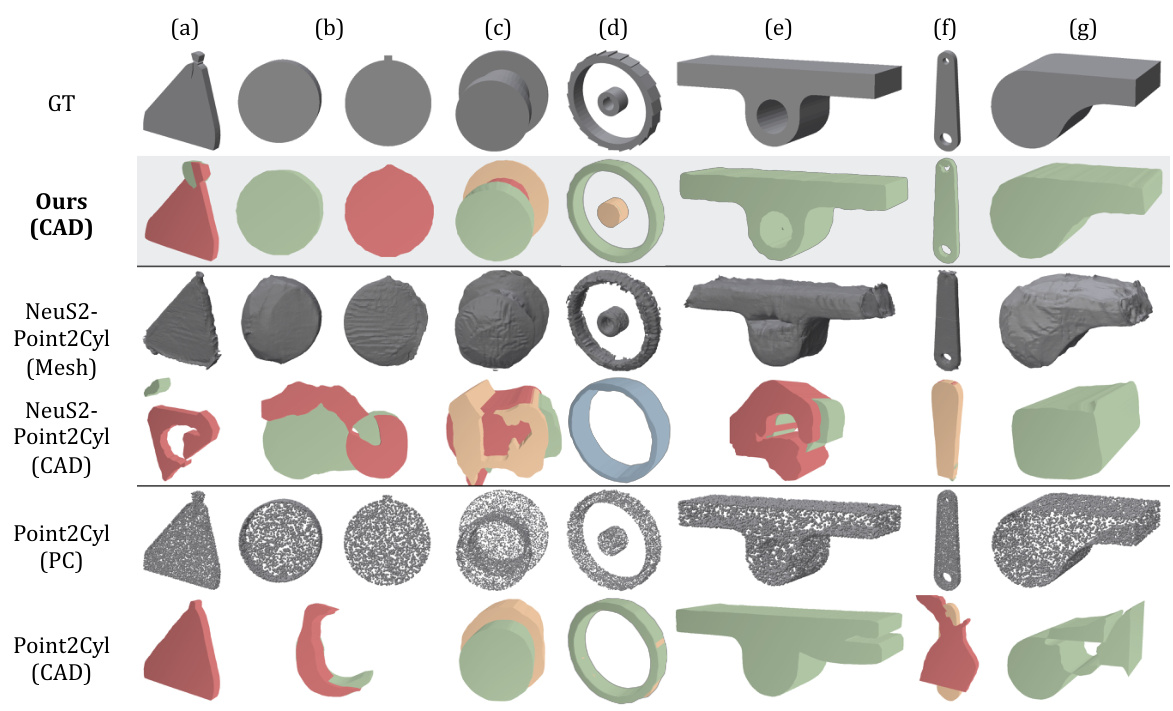

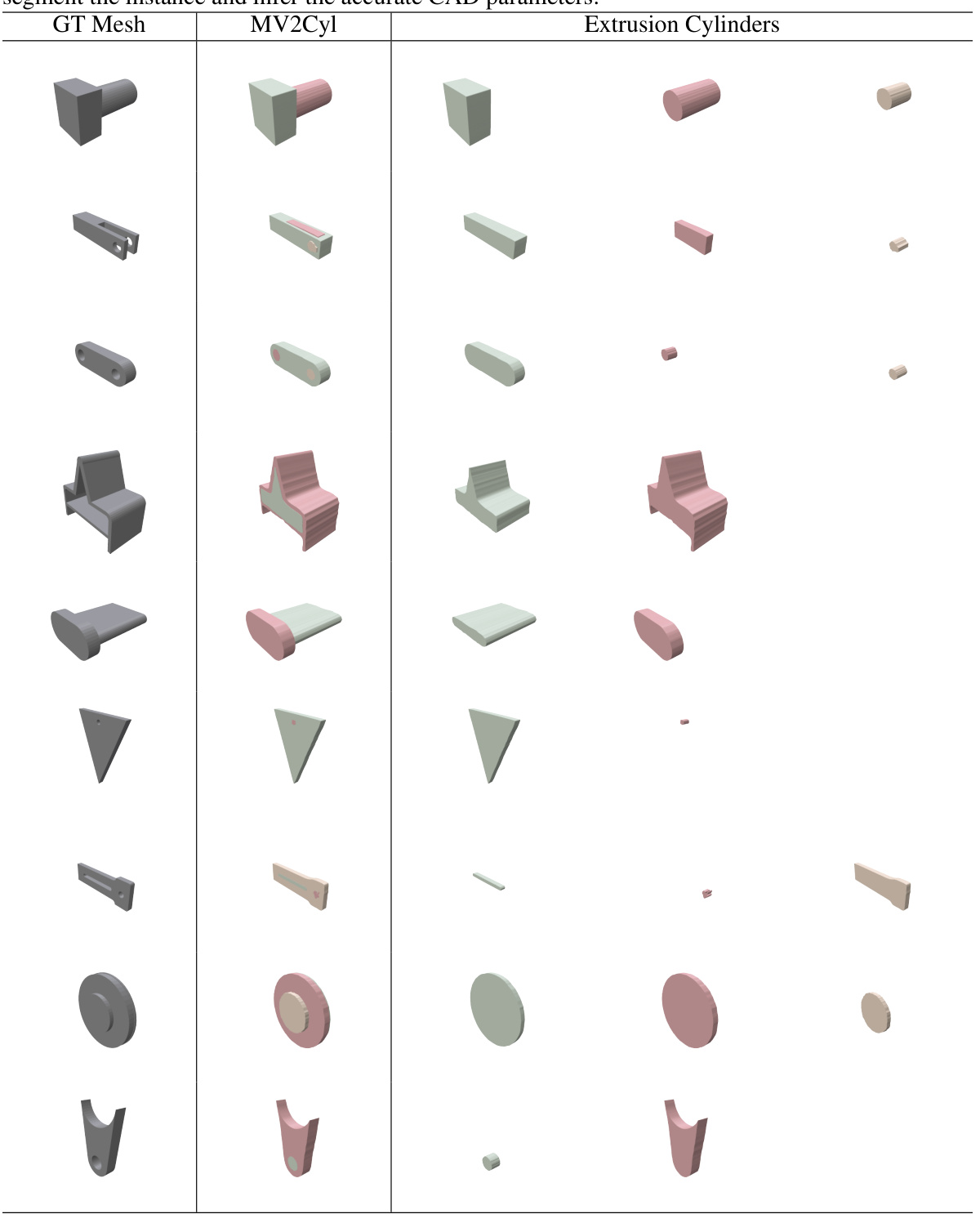

This figure compares the qualitative results of MV2Cyl against three baselines: Point2Cyl, NeuS2+Point2Cyl (using NeuS2 for 3D reconstruction from multi-view images as a pre-processing step before Point2Cyl), and a naive pipeline combining NeuS2 and Point2Cyl. Each row shows the ground truth CAD model, followed by the reconstruction from MV2Cyl and the three baselines. The results illustrate MV2Cyl’s superior ability to reconstruct complex shapes, even outperforming methods that directly use clean 3D point cloud data. The comparison with the NeuS2+Point2Cyl baseline highlights the importance of using edge information (which is preserved better in multi-view images than in point clouds produced by NeuS2) for accurate 3D structure reconstruction.

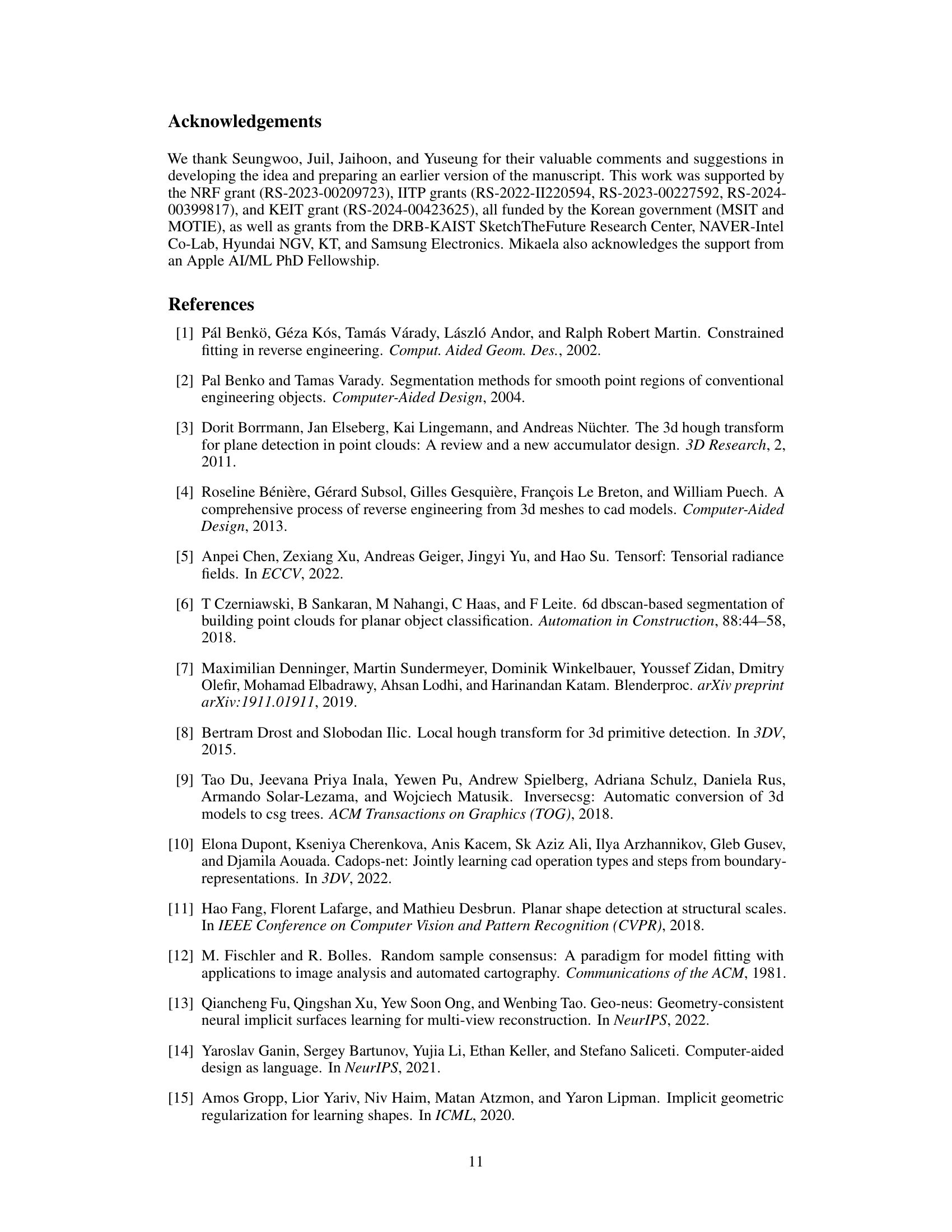

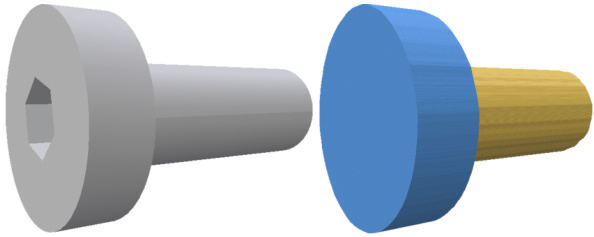

This figure shows an example where MV2Cyl fails to reconstruct a part of the object. The target CAD model contains an inset hexagonal cylinder on one side, which is hidden by an outer cylinder. MV2Cyl successfully reconstructs the outer cylinder but fails to reconstruct the inset cylinder because it is fully occluded in the input multi-view images.

This figure shows the results of applying the fine-tuned Segment Anything Model (SAM) to both real and synthetic images. The left side displays the processing steps applied to a real-world image: conversion to grayscale, background removal, and then instance and start/end segmentation using SAM. The right side shows the corresponding processed synthetic image for comparison. The goal is to demonstrate that the SAM model produces similar, useful segmentations for both real and synthetic images, despite differences in image characteristics.

This figure shows the three steps involved in aligning the real-world 3D model output to the ground truth CAD model for quantitative evaluation. First, the real demo CAD output is exported to a mesh. Second, a point cloud is sampled from this mesh and registered to the ground truth CAD model’s point cloud using a shape registration technique (presumably ICP, Iterative Closest Point). Third, Open3D’s ICP point cloud registration is used to finally align the point clouds and compute the Chamfer distance. This process ensures accurate comparison of the reconstructed model to the ground truth.

This figure shows a comparison of segmentation results between real and synthetic images. The real image undergoes preprocessing steps such as converting to grayscale and removing the background before being processed by the fine-tuned SAM model, which segments the image into instance segments (different parts of the objects) and start-end segments (start and end planes of extrusions). The results demonstrate that the fine-tuned model performs similarly well on both real and synthetic images, highlighting its robustness.

This figure shows the network architecture of the Point2Cyl method, which is used as a baseline in the paper. The architecture takes as input a point cloud representing the object’s geometry and is designed to infer the parameters of the extrusion cylinders that make up the object. It consists of several modules: a PointNet++ backbone to extract features from the point cloud; a segmentation and reordering module to group points belonging to the same cylinder instance; a differentiable module for parameter estimation, a projector operator, and modules to predict 2D sketches. The network is trained to minimize a loss function that combines losses related to segmentation, boundary box fitting, sketch reconstruction, and parameter estimation.

This figure shows the network architecture of Curve+Point2Cyl, a modified version of Point2Cyl that incorporates curve information into the input point cloud. The original Point2Cyl takes as input a tensor of size N x 3, representing the point cloud. Curve+Point2Cyl concatenates M curve points after the N input points, adding an extra channel with labels (1 for curve points, 0 for others). The rest of the architecture remains unchanged. The figure highlights the inputs, network components, variables, external solver, differentiable module, and the training and inference stages.

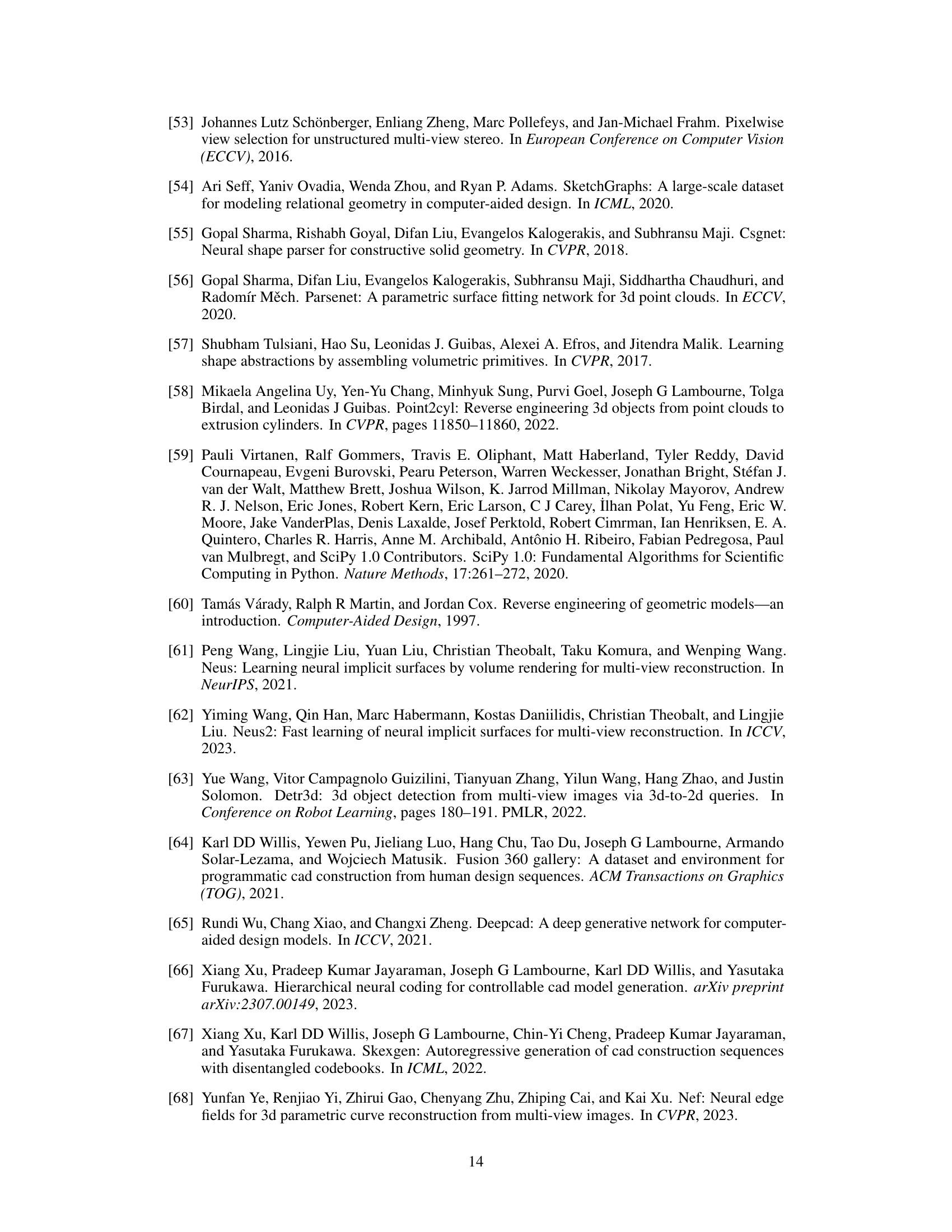

This figure presents an ablation study comparing the performance of using only surface information, only curve information, and both surface and curve information for 3D CAD reconstruction. The results demonstrate that using both surface and curve information leads to more accurate and complete reconstructions, particularly when dealing with occlusion or challenging geometric features.

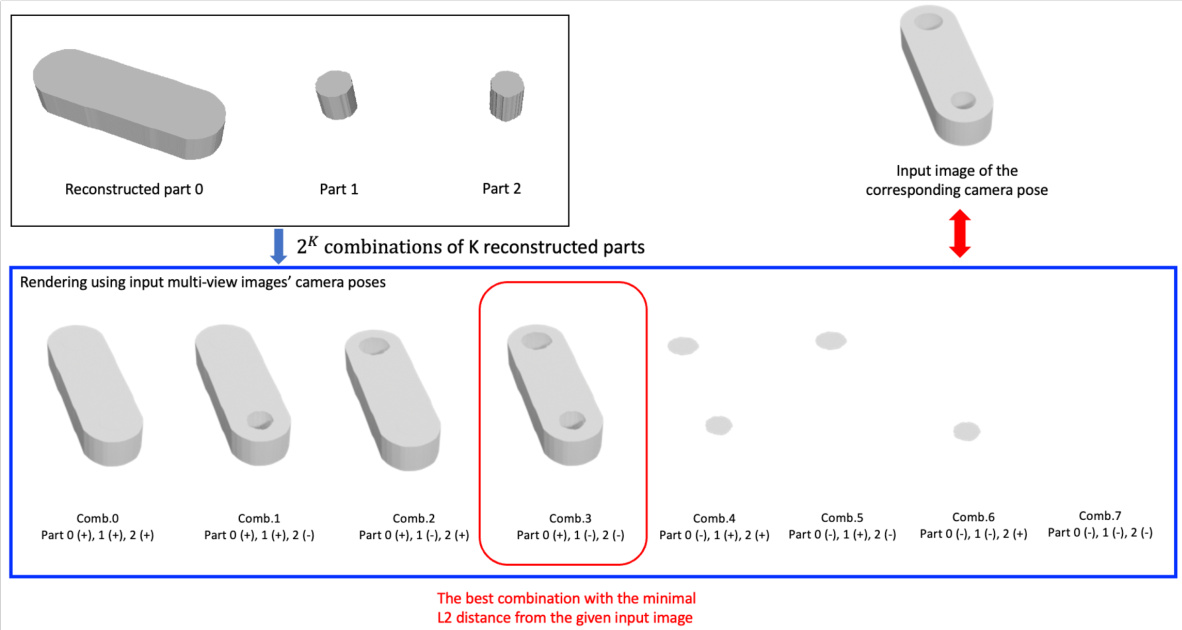

This figure illustrates the process of determining the optimal combination of binary operations (union, difference, intersection) among the reconstructed extrusion cylinders. Given K reconstructed parts, there are 2K possible combinations of operations. Each combination is rendered using the camera poses from the input multi-view images, and the combination that yields the rendered image with the minimal L2 distance to the original input image is chosen as the best one. This example shows an instance where K=3.

This figure illustrates the learned 3D fields used for surface and curve reconstruction in MV2Cyl. It shows six different fields: surface density field, surface instance semantic field, surface start/end semantic field, curve density field, curve instance semantic field, and curve start/end semantic field. Each field provides different types of information about the object’s geometry, which are then combined for 3D reconstruction. The left-to-right arrangement corresponds to the order in which the fields are presented.

This figure shows an example of how the proposed method predicts binary operations for the reconstructed extrusion cylinders. The input image of the corresponding camera pose is given along with 2k combinations of k reconstructed parts. The method renders the images using camera poses from the input images and selects the combination with the lowest L2 distance to the given input image.

This figure shows an example of how the method predicts binary operations. It demonstrates that given a set of K reconstructed parts, it evaluates 2^K possible combinations of those parts with various binary operations (+, -). It then renders each combination to compare against the input multi-view image and chooses the best combination based on the minimal L2 distance from the input image. This effectively reconstructs the final CAD model using the identified binary operations.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of MV2Cyl using different combinations of surface and curve information for 3D reconstruction on the Fusion360 dataset. It shows that using both surface and curve information leads to the best performance, while omitting either results in significantly reduced accuracy.

This ablation study demonstrates the importance of using both surface and curve information in the MV2Cyl model for accurate CAD reconstruction. The table shows that using only surface information or only curve information leads to significantly worse results compared to using both. The best performance is achieved by combining both surface and curve information.

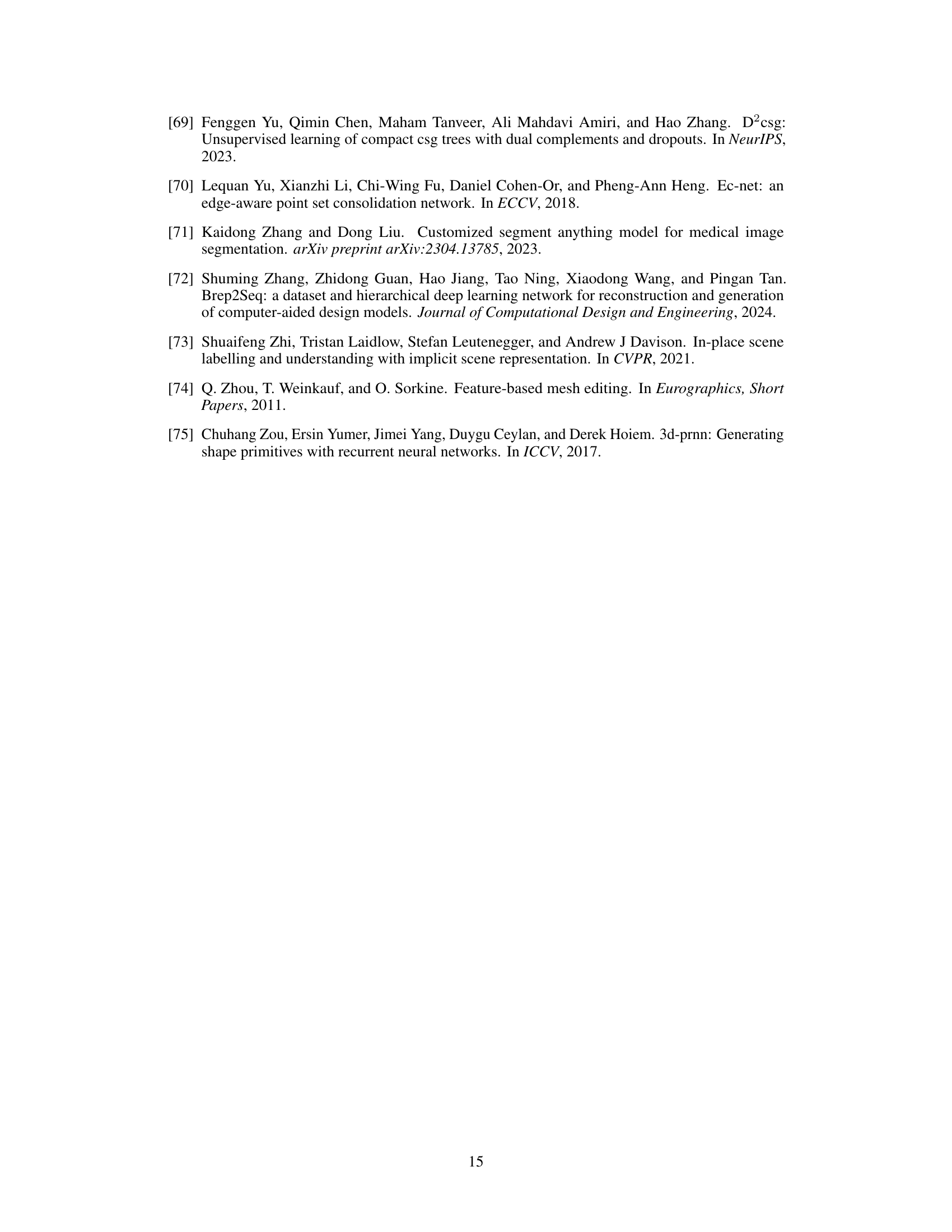

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of two different methods for performing U-Net based segmentation in the MV2Cyl model. The first row shows the results when a single shared U-Net is used to perform both curve and surface segmentations. The second row shows the results when separate U-Nets are used for curve and surface segmentation. The metrics compared are extrusion axis error (E.A.), extrusion center error (E.C.), extrusion height error (E.H.), cylinder fitting loss (Fit. Cyl.), and global fitting loss (Fit. Glob.).

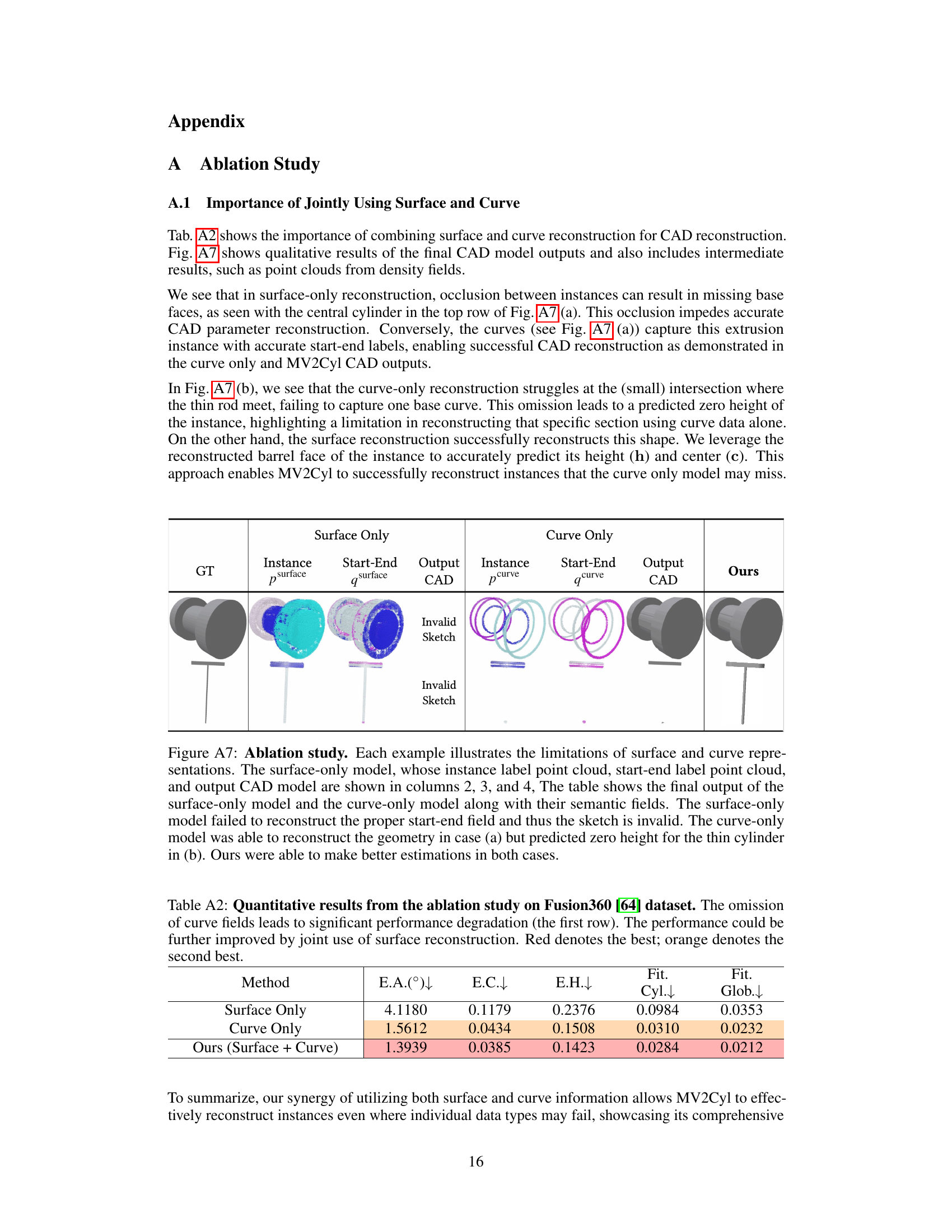

This table shows the results of the model’s performance on the Fusion360 dataset when varying the number of instances (K) in the scene. It displays the average extrusion axis error (E.A.), extrusion center error (E.C.), extrusion height error (E.H.), per-extrusion cylinder fitting loss (Fit Cyl.), and global fitting loss (Fit Glob.). The number of samples available for testing decreases as the number of instances increases, resulting in fewer samples for larger K values (7 and 8).

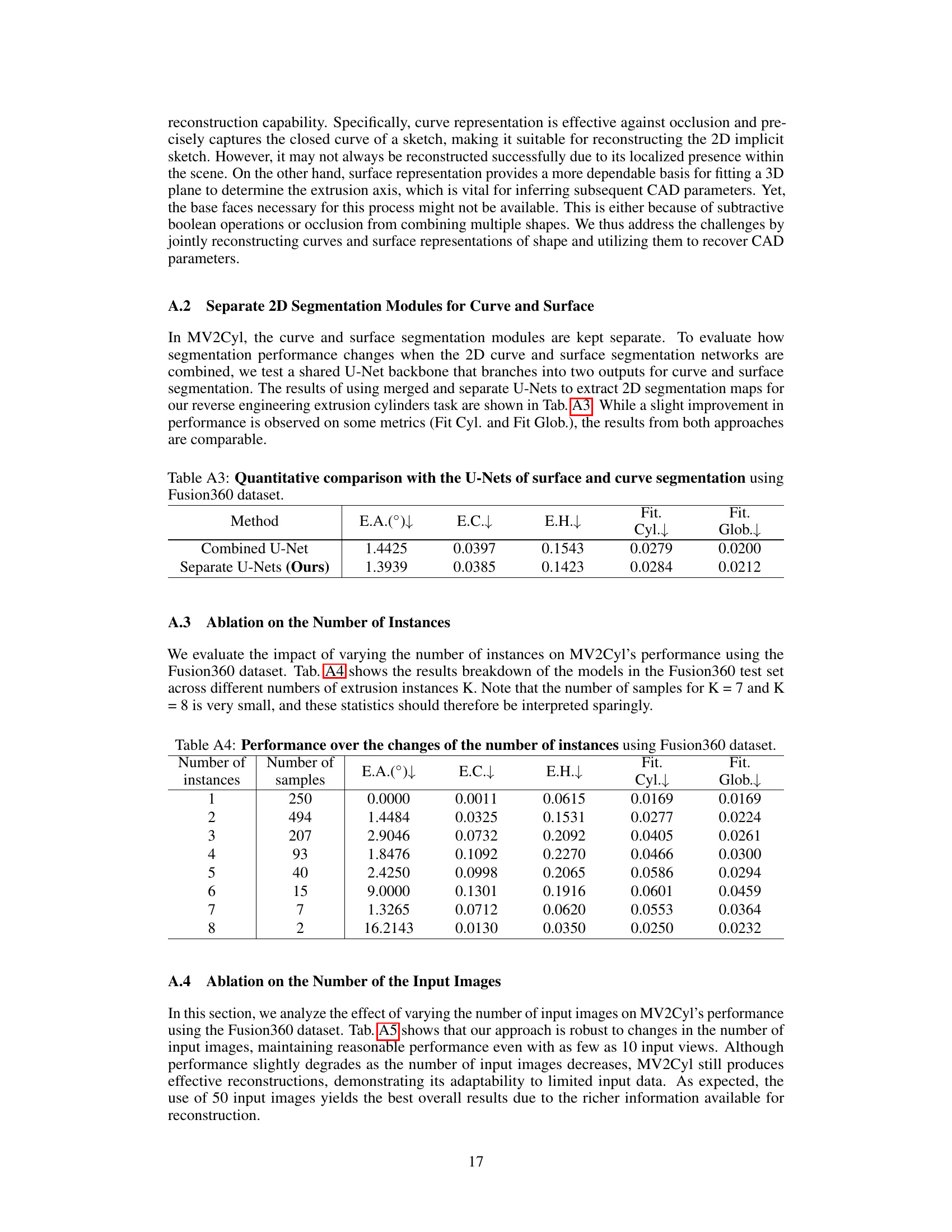

This table presents an ablation study on the MV2Cyl model, showing the impact of varying the number of input images on its performance. The metrics used are extrusion axis error (E.A.), extrusion center error (E.C.), extrusion height error (E.H.), per-extrusion cylinder fitting loss (Fit Cyl.), and global fitting loss (Fit Glob.). Lower values are better for all metrics. The results indicate that the model maintains reasonable performance even with a small number of input images, although performance slightly degrades as the number decreases, demonstrating its adaptability to limited input data. Using 50 input images yields the best results.

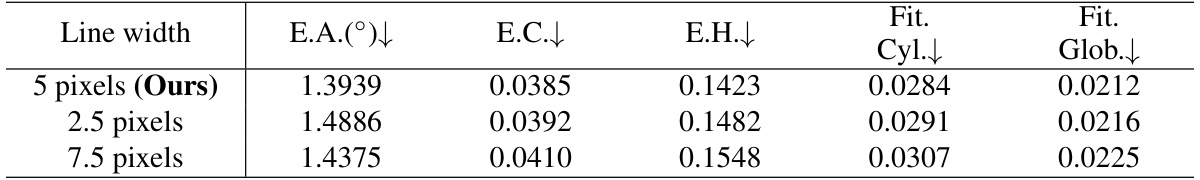

This table presents an ablation study on the effect of varying the line width of curve segmentation maps on the performance of the MV2Cyl model. It shows that the model is relatively robust to changes in line width, maintaining consistent performance across different widths. The best performance is achieved with a line width of 5 pixels, while slight variations are observed at 2.5 and 7.5 pixels, indicating that MV2Cyl can handle a range of line widths without significant performance loss.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed MV2Cyl method against several baselines on two datasets (Fusion360 and DeepCAD) using four metrics: extrusion axis error (E.A.), extrusion center error (E.C.), per-extrusion cylinder fitting loss (Fit Cyl.), and global fitting loss (Fit Glob.). The results demonstrate that MV2Cyl achieves significantly better performance than the alternative methods.

This table presents a qualitative comparison of the results obtained using MV2Cyl and SECAD-Net on the Fusion360 dataset. It visually demonstrates the superiority of MV2Cyl in accurately segmenting and reconstructing individual instances of extrusion cylinders compared to SECAD-Net, which often struggles with over-segmentation.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of MV2Cyl and Curve+Point2Cyl on the Fusion360 dataset. The metrics used are extrusion axis error (E.A.), extrusion center error (E.C.), extrusion height error (E.H.), cylinder fitting loss (Fit. Cyl.), and global fitting loss (Fit. Glob.). MV2Cyl demonstrates significantly better performance than Curve+Point2Cyl across all metrics.

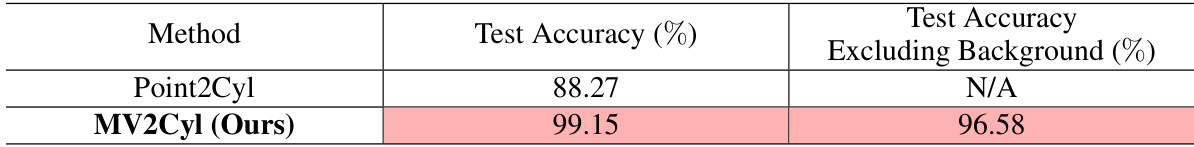

This table compares the performance of the 2D segmentation network used in MV2Cyl and the 3D segmentation network used in Point2Cyl in terms of test accuracy. The 2D network in MV2Cyl achieves significantly higher accuracy, particularly when excluding background pixels, supporting the paper’s claim that 2D networks are more effective for this task.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the Chamfer distances achieved by MV2Cyl and the baseline method NeuS2+Point2Cyl on the Fusion360 and DeepCAD datasets. The Chamfer distance is a metric used to assess the geometric similarity between two point clouds. Lower values indicate better reconstruction quality. The values in the table are multiplied by 103 for easier readability.

This table presents a qualitative comparison of the ground truth CAD models, the reconstructions produced by the MV2Cyl model, and the extracted extrusion cylinders. Each row represents a different object. The goal is to show that MV2Cyl accurately segments the objects into their constituent parts (extrusion cylinders) and estimates their CAD parameters effectively.

Full paper#