↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Modern chip design heavily relies on efficient macro placement, a complex optimization problem significantly influencing power, performance, and area (PPA). Existing methods, including those employing reinforcement learning (RL), struggle with long training times, low generalization, and difficulty guaranteeing PPA improvements. A key issue lies in formulating the problem; using RL to design from scratch limits useful information and leads to inaccurate reward signals during training.

This paper introduces MaskRegulate, which uses RL for refinement of existing macro placement layouts. This shift allows the RL policy to utilize sufficient information for effective action and obtain precise rewards. Furthermore, MaskRegulate incorporates ‘regularity’, a key metric in chip design, during training, improving placement quality and aligning with industry requirements. Evaluations on benchmarks using Cadence Innovus demonstrate significant PPA improvements over existing techniques, highlighting MaskRegulate’s potential to revolutionize chip design optimization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to macro placement in chip design, a crucial step impacting power, performance, and area. By using reinforcement learning for refinement instead of initial placement, it addresses limitations of existing RL-based methods such as long training times and poor generalization. The introduction of regularity as a crucial metric and the demonstrated significant PPA improvements open up exciting avenues for research and development in optimizing chip design. It offers a more effective and efficient approach, improving chip design and potentially leading to significant advancements in chip technology.

Visual Insights#

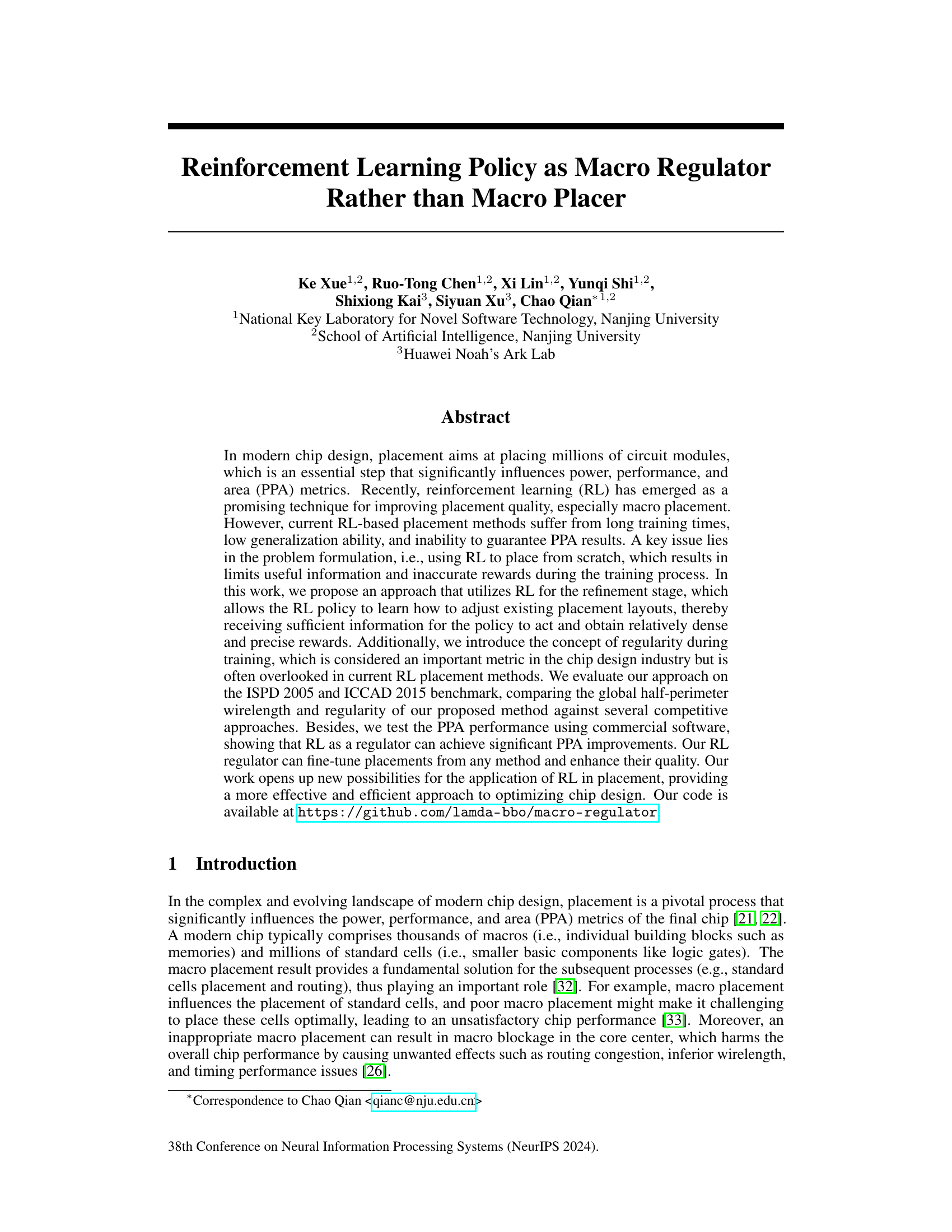

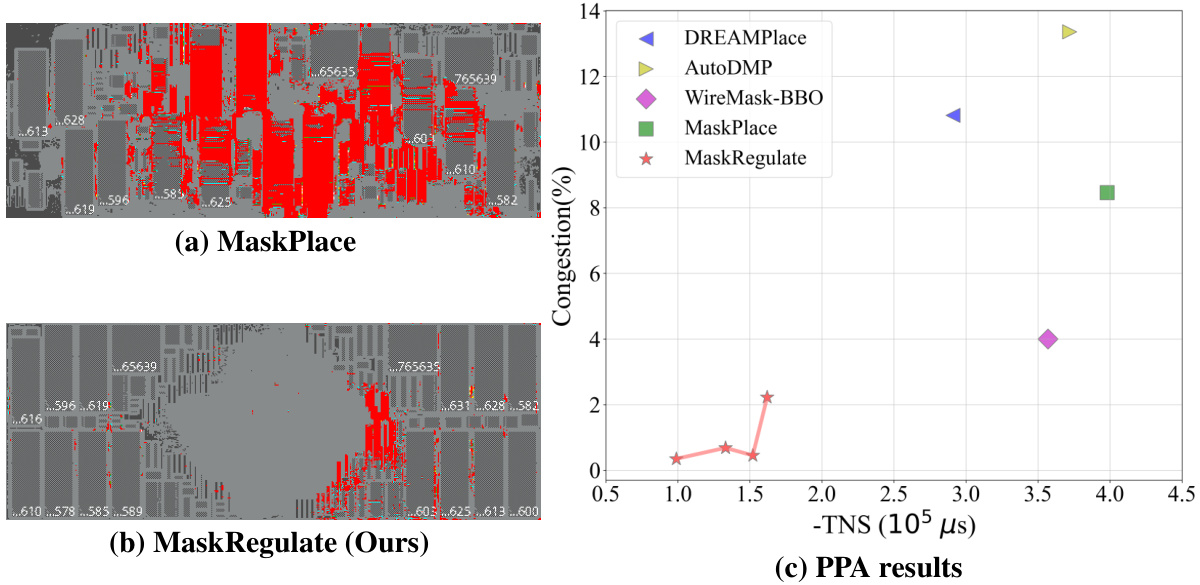

This figure compares the placement layouts and congestion levels of MaskPlace and the proposed MaskRegulate method on the superblue1 benchmark from the ICCAD 2015 dataset. Subfigure (a) shows MaskPlace’s layout, while (b) shows MaskRegulate’s improved layout with reduced congestion in the red highlighted areas. Subfigure (c) provides a quantitative comparison of two key performance metrics (congestion and total negative slack (TNS)) between MaskRegulate and four other state-of-the-art placement methods (DREAMPlace, AutoDMP, WireMask-EA, and MaskPlace), highlighting the superior performance of MaskRegulate. The PPA (Power, Performance, Area) results are obtained using Cadence Innovus, a commercial electronic design automation tool.

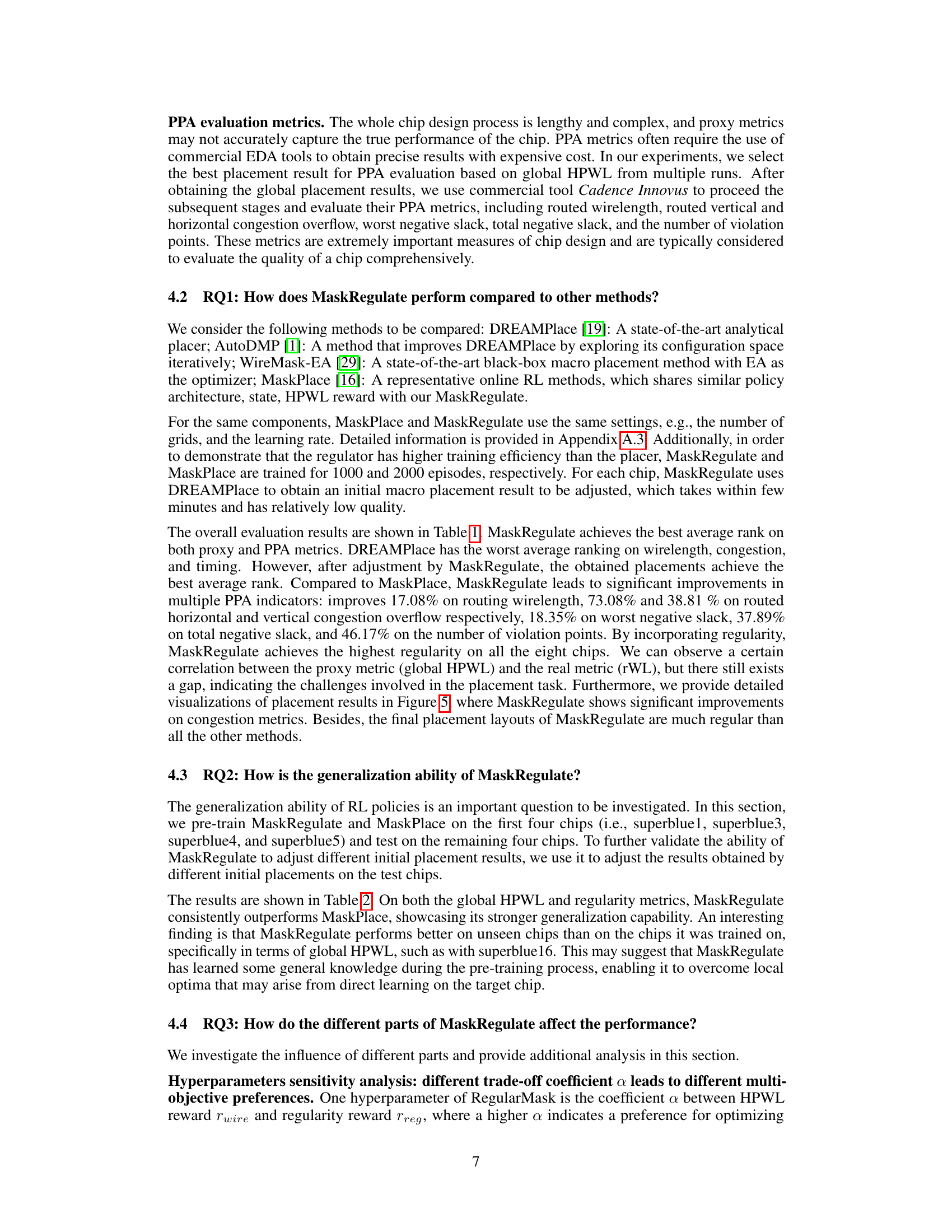

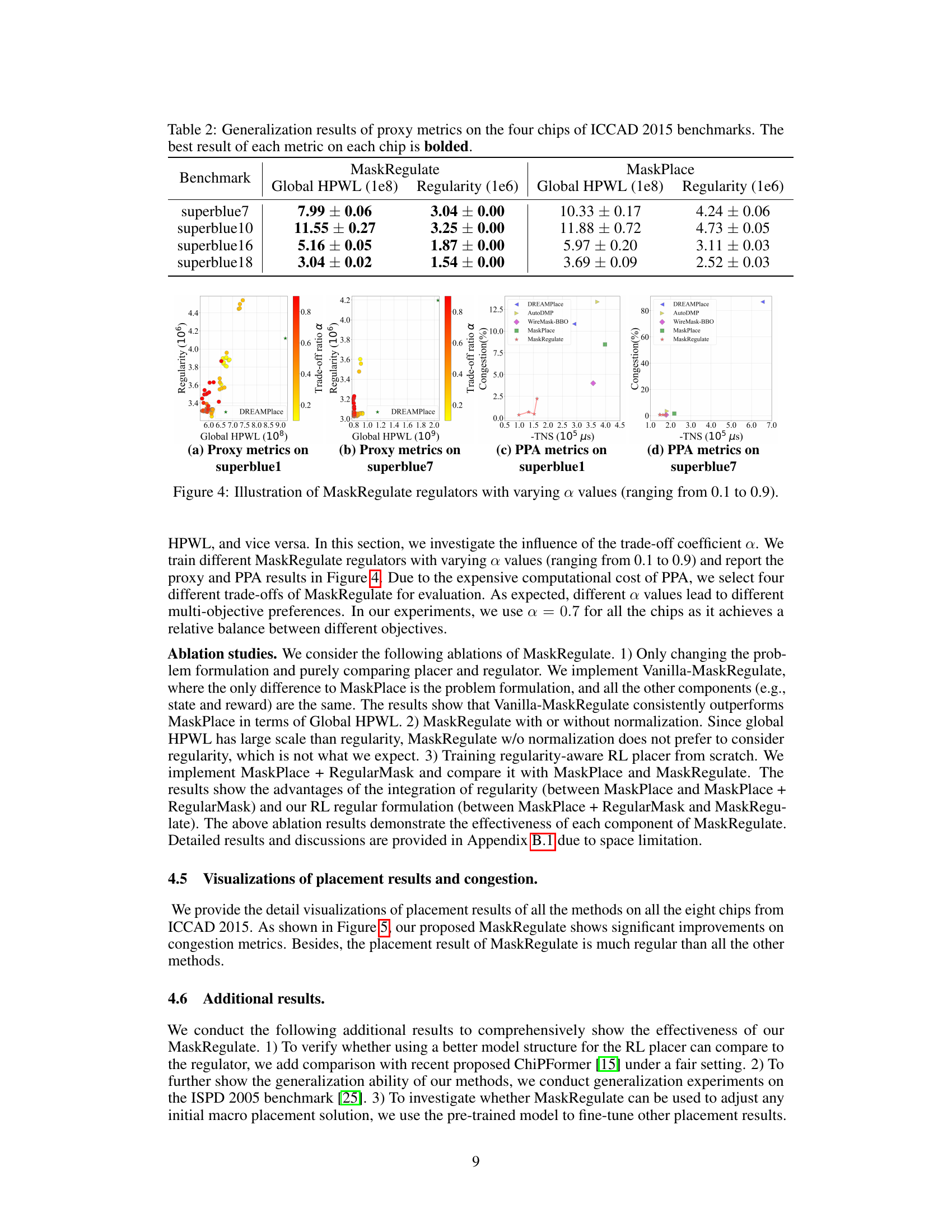

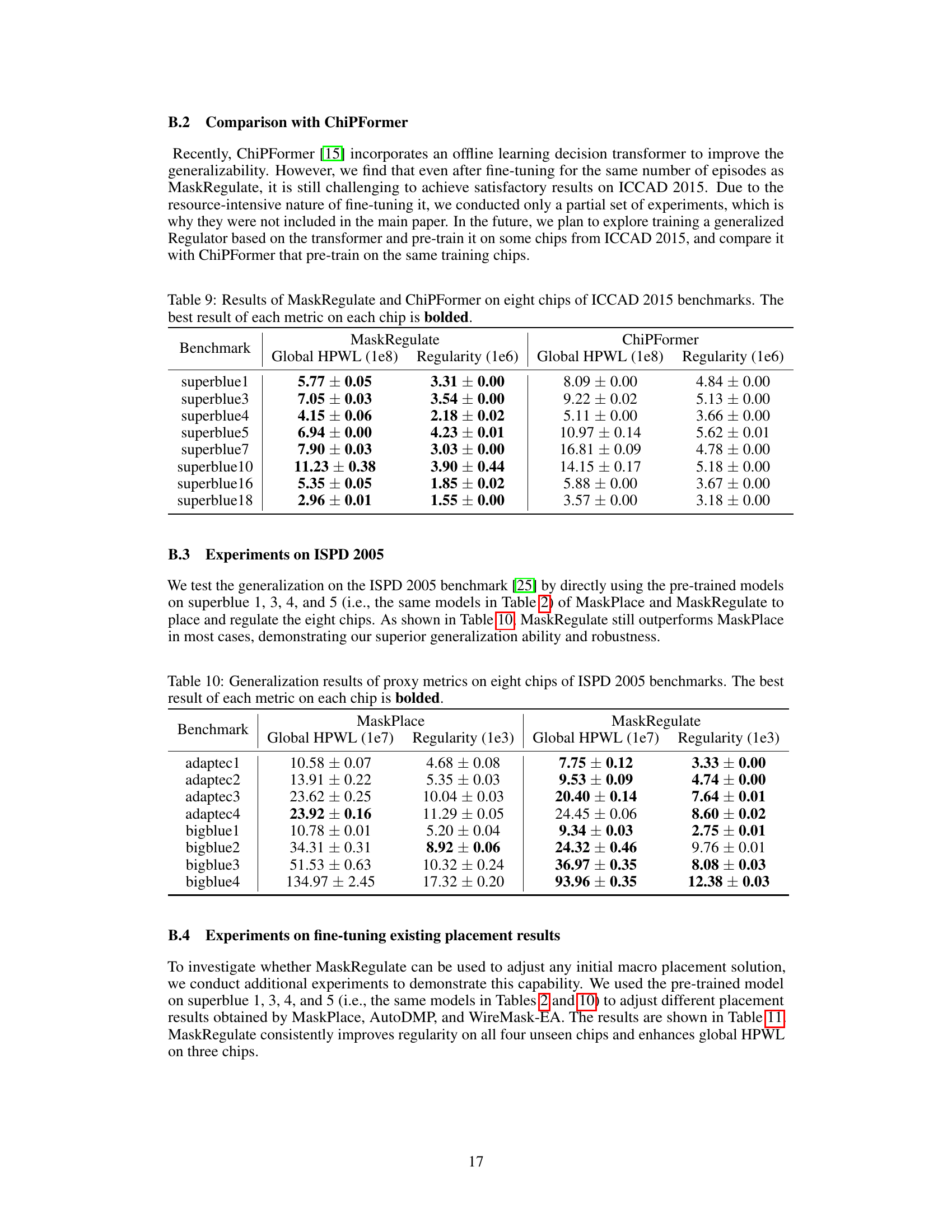

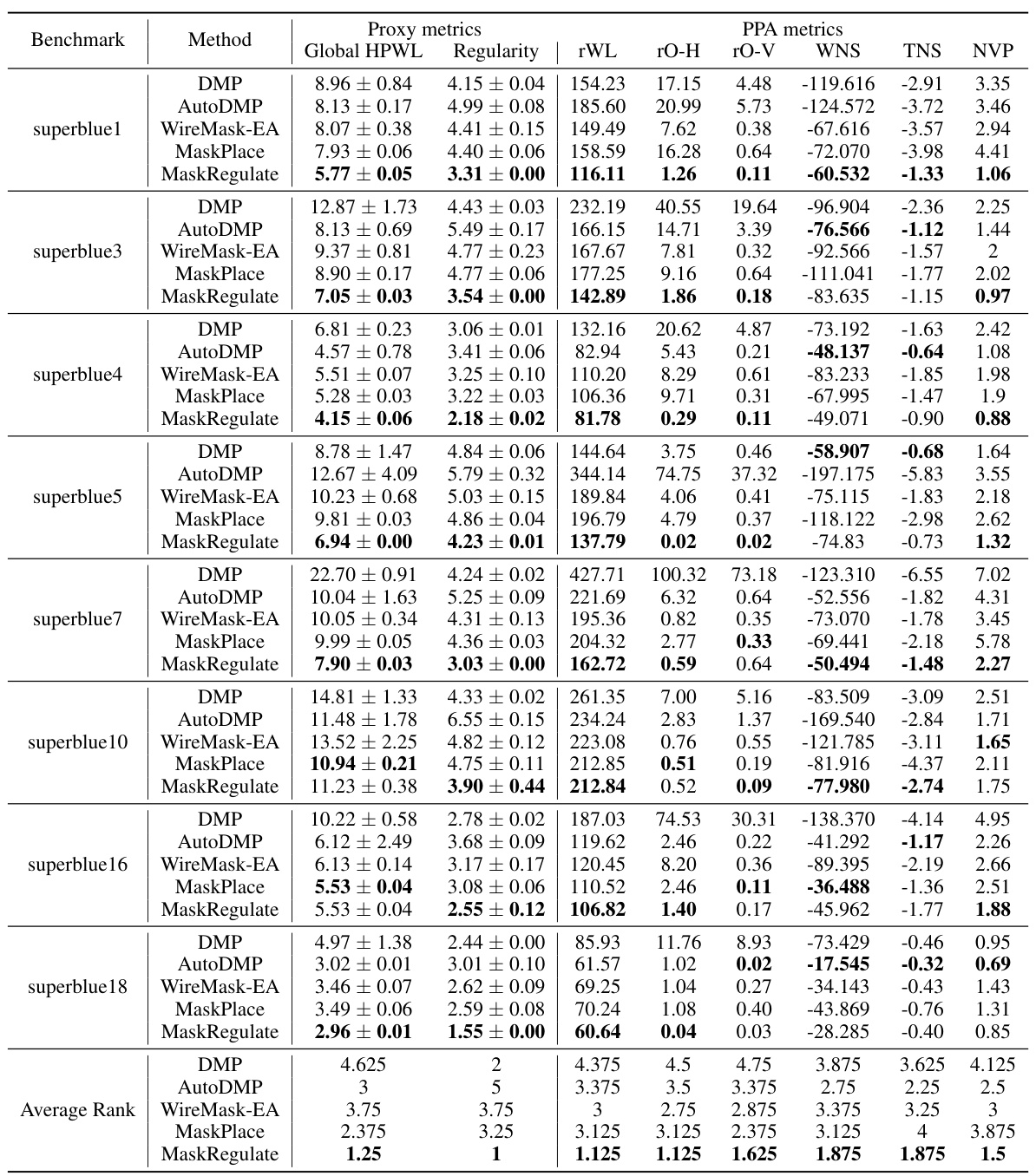

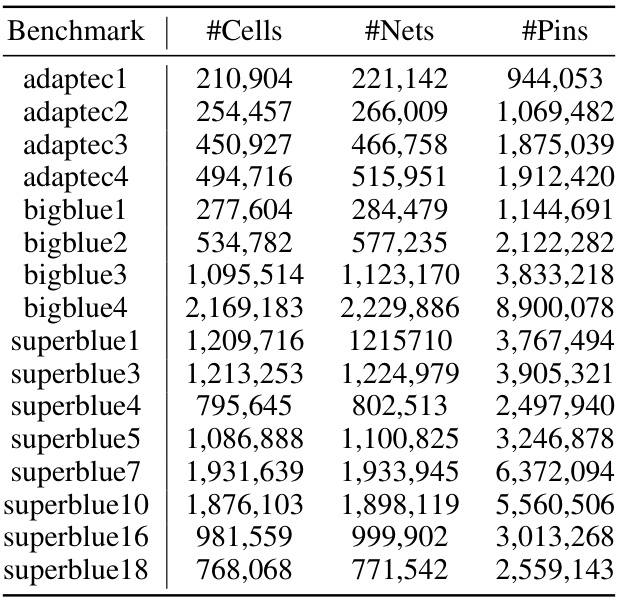

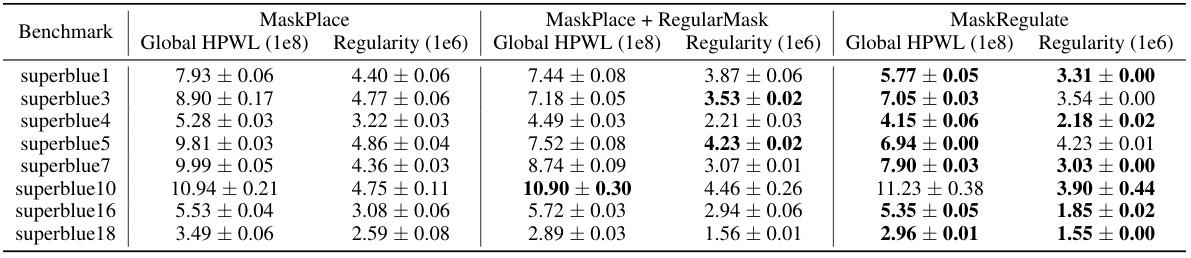

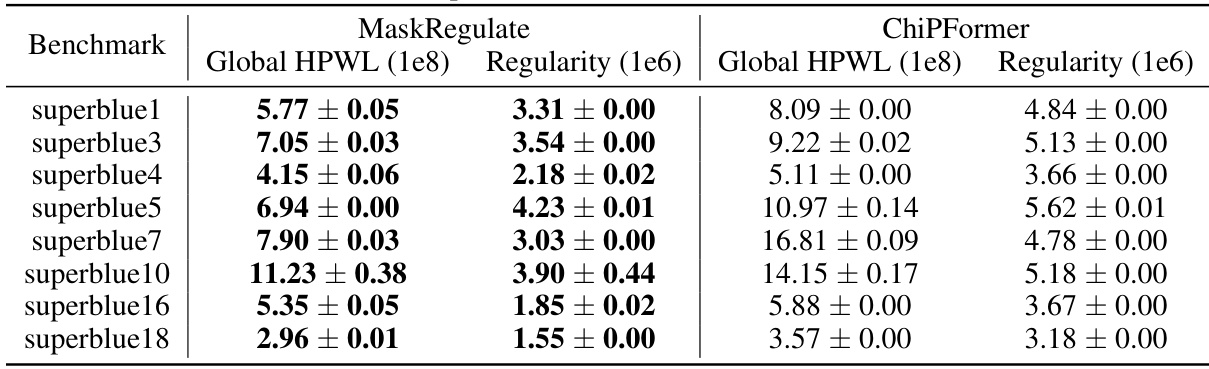

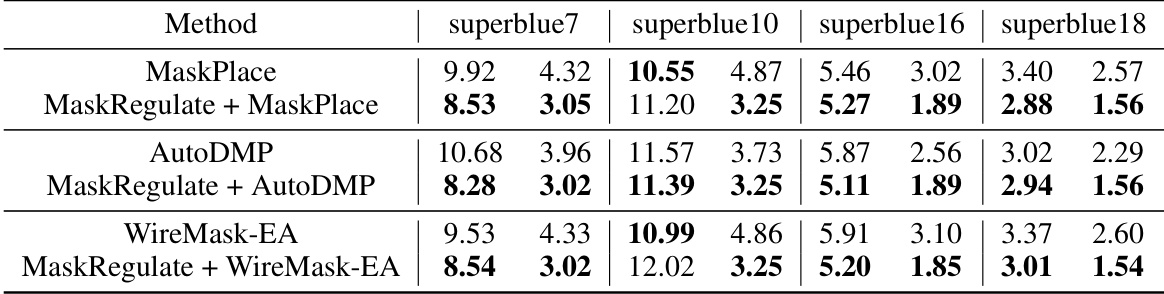

This table presents a comparison of different macro placement methods (DREAMPlace, AutoDMP, WireMask-EA, MaskPlace, and MaskRegulate) using both proxy metrics (Global HPWL and Regularity) and actual PPA metrics (routed wirelength, congestion, timing slack, and violation points) evaluated using Cadence Innovus. The results are shown for eight benchmark chips from the ICCAD 2015 dataset. The best performance for each metric on each chip is highlighted.

In-depth insights#

RL Macro Regulator#

The concept of an “RL Macro Regulator” in chip placement presents a paradigm shift from traditional reinforcement learning (RL) approaches. Instead of using RL to place macros from scratch, which often suffers from long training times and poor generalization, the RL agent acts as a regulator, refining existing placement layouts. This approach leverages the inherent structure of pre-placed macros, providing richer state information and more accurate reward signals for the RL policy to learn from. A key advantage is the ability to fine-tune placements from various initial methods, enhancing overall quality. Furthermore, incorporating metrics like regularity, often overlooked in RL placement, aligns the approach with industry priorities and results in more manufacturable designs. The use of proxy metrics for evaluating the placement, such as half-perimeter wirelength and congestion, provides efficient feedback during training. Ultimately, this regulatory RL approach offers a more effective and efficient method for macro placement optimization, improving power, performance, and area (PPA) metrics.

Regularity in Placement#

In modern chip design, placement regularity, often overlooked, is crucial for manufacturability and performance. A regular placement, with macros positioned towards the periphery and avoiding central congestion, facilitates easier routing and reduces wirelength. The paper’s proposed MaskRegulate method innovatively integrates regularity as a key metric in reinforcement learning for macro placement. By incorporating regularity in both the state representation and reward function, the RL agent learns to prefer more regular layouts. This directly addresses the limitations of previous RL-based methods, which primarily focused on minimizing wirelength and often resulted in irregular, less manufacturable designs. This integration of regularity aligns the RL approach with industry best-practices, making the resulting placements not only wirelength-optimized, but also significantly improved in terms of overall PPA (power, performance, area) metrics as demonstrated by the experimental results.

PPA Improvements#

The research demonstrates significant power, performance, and area (PPA) improvements using reinforcement learning (RL) for macro placement refinement. MaskRegulate, the proposed method, achieves this by acting as a regulator rather than a placer, fine-tuning existing placements. This approach leverages richer state information and more accurate reward signals than traditional RL-based methods that place from scratch, leading to better learning. The integration of regularity as a critical metric further enhances results. Compared to other state-of-the-art methods, MaskRegulate shows substantial improvements in routing wirelength, congestion, and timing slack, verified through commercial EDA tools like Cadence Innovus. These improvements suggest that RL-based refinement holds significant promise for enhancing overall chip design quality and efficiency.

Generalization Ability#

The study’s exploration of generalization ability in reinforcement learning (RL) for macro placement is crucial. The authors cleverly address the challenge of limited generalizability in existing RL-based approaches by focusing on refinement rather than initial placement. This allows their RL regulator (MaskRegulate) to learn from richer state information and more accurate reward signals. Pre-training on a subset of benchmark chips and subsequent testing on unseen chips demonstrates MaskRegulate’s superior generalization. This is a significant finding, suggesting that refinement-based RL strategies could be more effective and efficient for broader application in chip design, where adaptability across diverse chip layouts is critical. Further analysis reveals that the regulator consistently outperforms traditional methods even when adjusting initial placements from different algorithms, highlighting its robustness. The integration of regularity further enhances the method’s real-world applicability.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section could fruitfully explore several avenues. Addressing the limitations of relying solely on proxy metrics like HPWL for evaluation is crucial; incorporating direct PPA metrics within the RL framework would provide more robust and relevant feedback. Expanding the scalability of the approach to handle significantly larger designs and more complex chip architectures is key. Investigating the impact of macro aspect ratios and areas on placement quality and exploring more sophisticated state representation methods for better generalization are important. The development of more advanced transformer architectures to enhance the regulator’s generalization capability across different chip designs would significantly improve its applicability. Finally, research into multi-objective optimization techniques is warranted to balance competing goals like wirelength, regularity, and timing constraints, leading to a truly comprehensive and optimized placement solution.

More visual insights#

More on figures

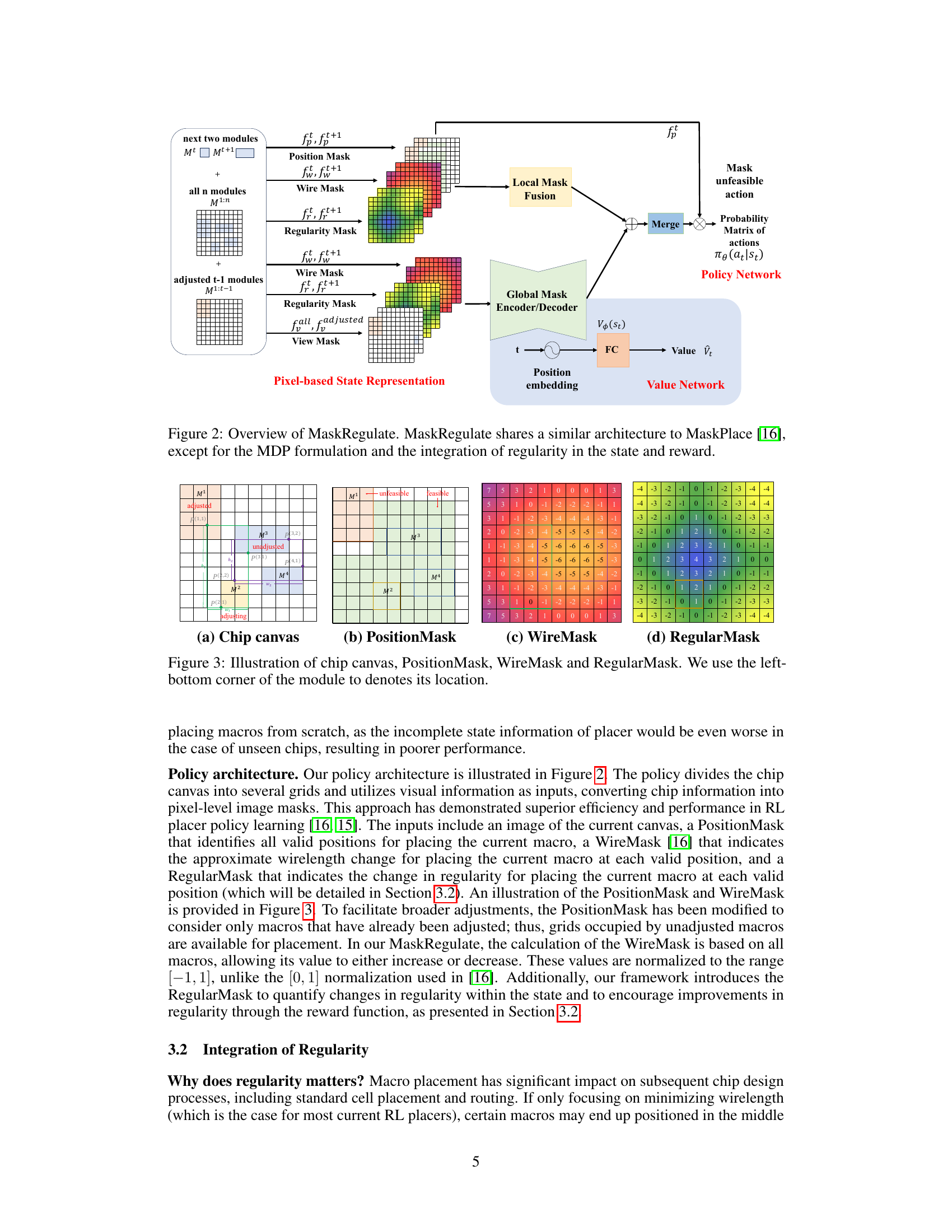

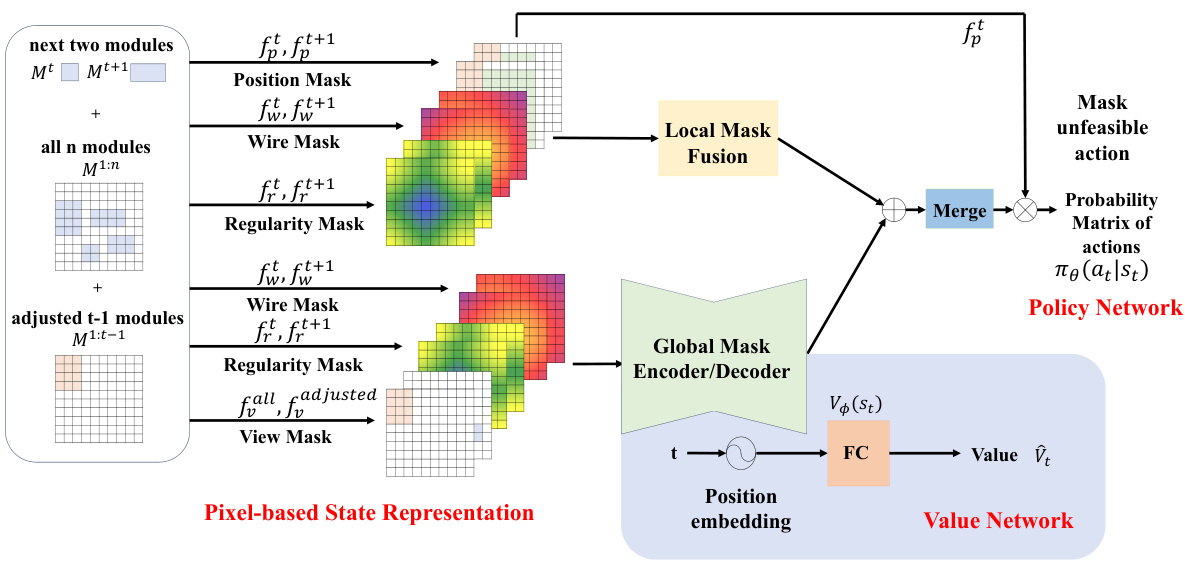

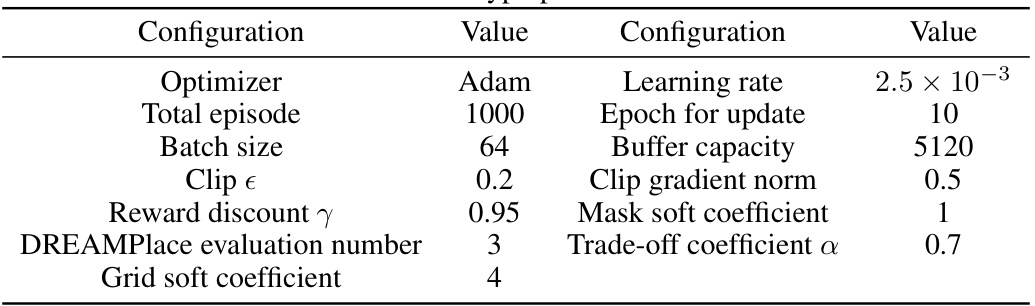

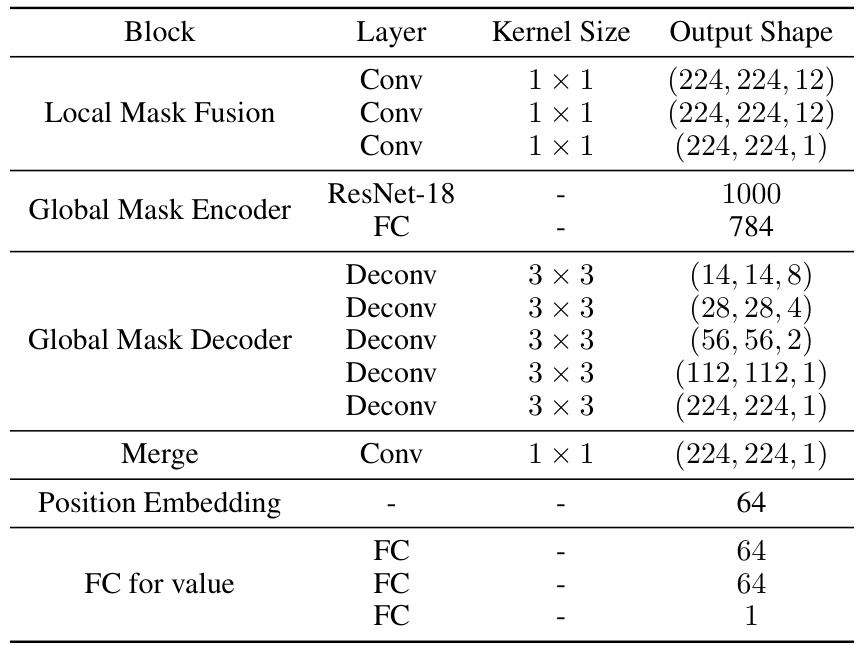

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed MaskRegulate method. MaskRegulate takes inspiration from MaskPlace but modifies the Markov Decision Process (MDP) formulation and incorporates a regularity component into the state and reward. The input consists of several image masks representing the chip canvas, macro positions, wire lengths, and regularity. These masks are processed through a local mask fusion and a global encoder/decoder network to generate an action probability matrix and value estimations, guiding the placement refinement process.

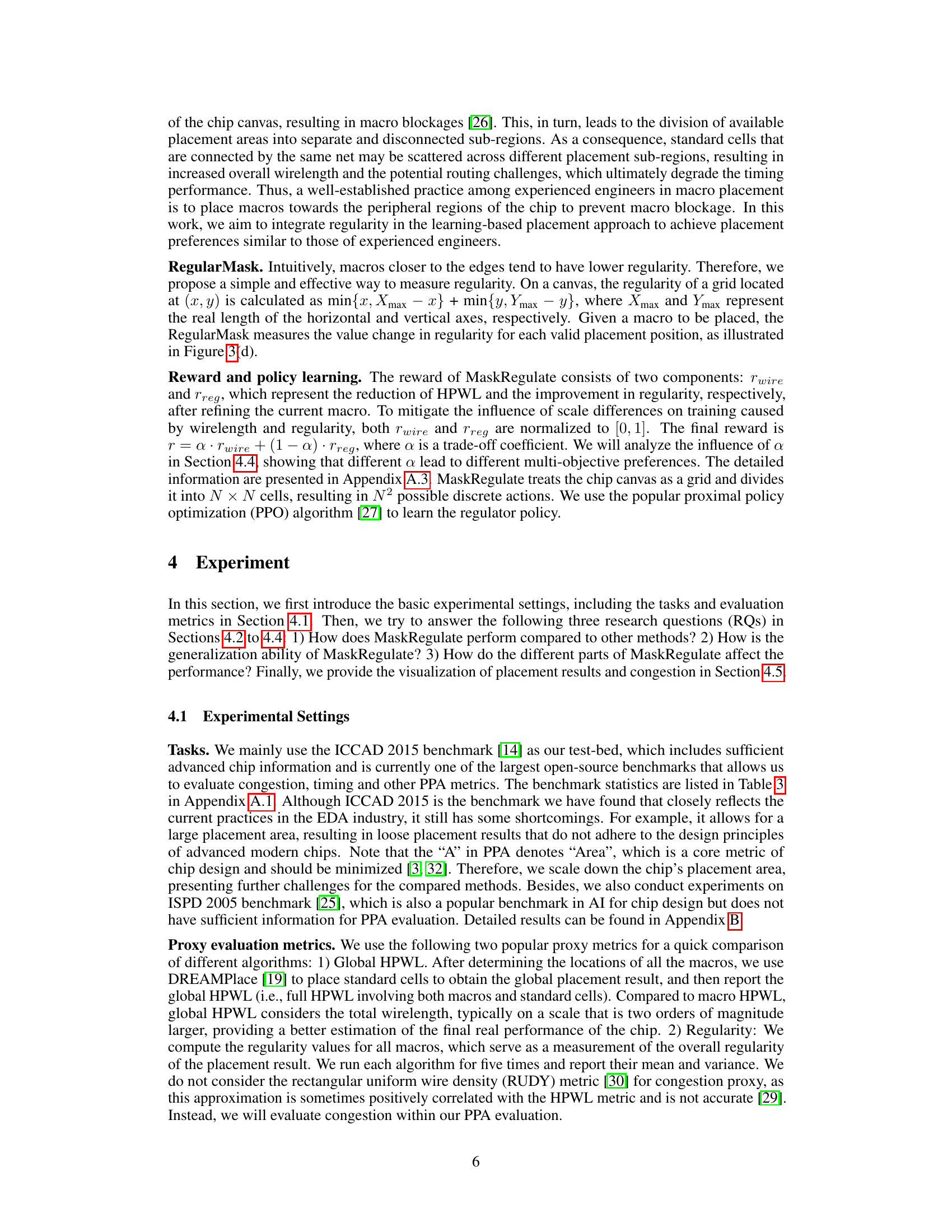

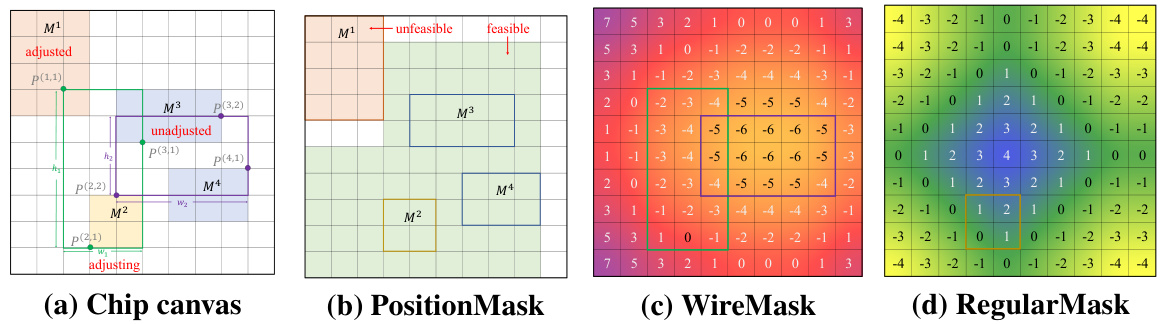

This figure shows four different types of masks used in the MaskRegulate algorithm. (a) shows the chip canvas, which is a grid representing the chip layout. (b) shows the PositionMask, which indicates the valid positions for placing the current macro. The color coding represents whether each position is feasible or not. (c) shows the WireMask, a heatmap representing the change in wirelength if the current macro is placed at each position. The colors indicate the magnitude and direction of the change. (d) shows the RegularityMask, a heatmap showing the regularity score for each position. This mask encourages placing macros towards the edges of the chip, which improves regularity and reduces macro blockages.

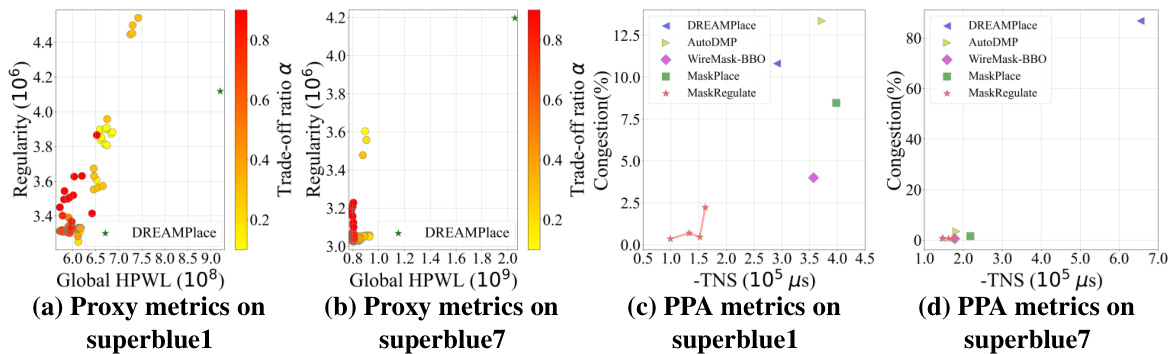

This figure visualizes the impact of the trade-off coefficient α on the performance of MaskRegulate. It shows how different values of α (controlling the balance between minimizing HPWL and maximizing regularity) affect the global HPWL and regularity proxy metrics (a, b) and PPA metrics (c, d) on the superblue1 and superblue7 benchmarks. Different α values lead to different multi-objective preferences in the optimization process. The plots reveal the trade-offs between minimizing wirelength and maximizing regularity, highlighting the influence of α on the final placement quality.

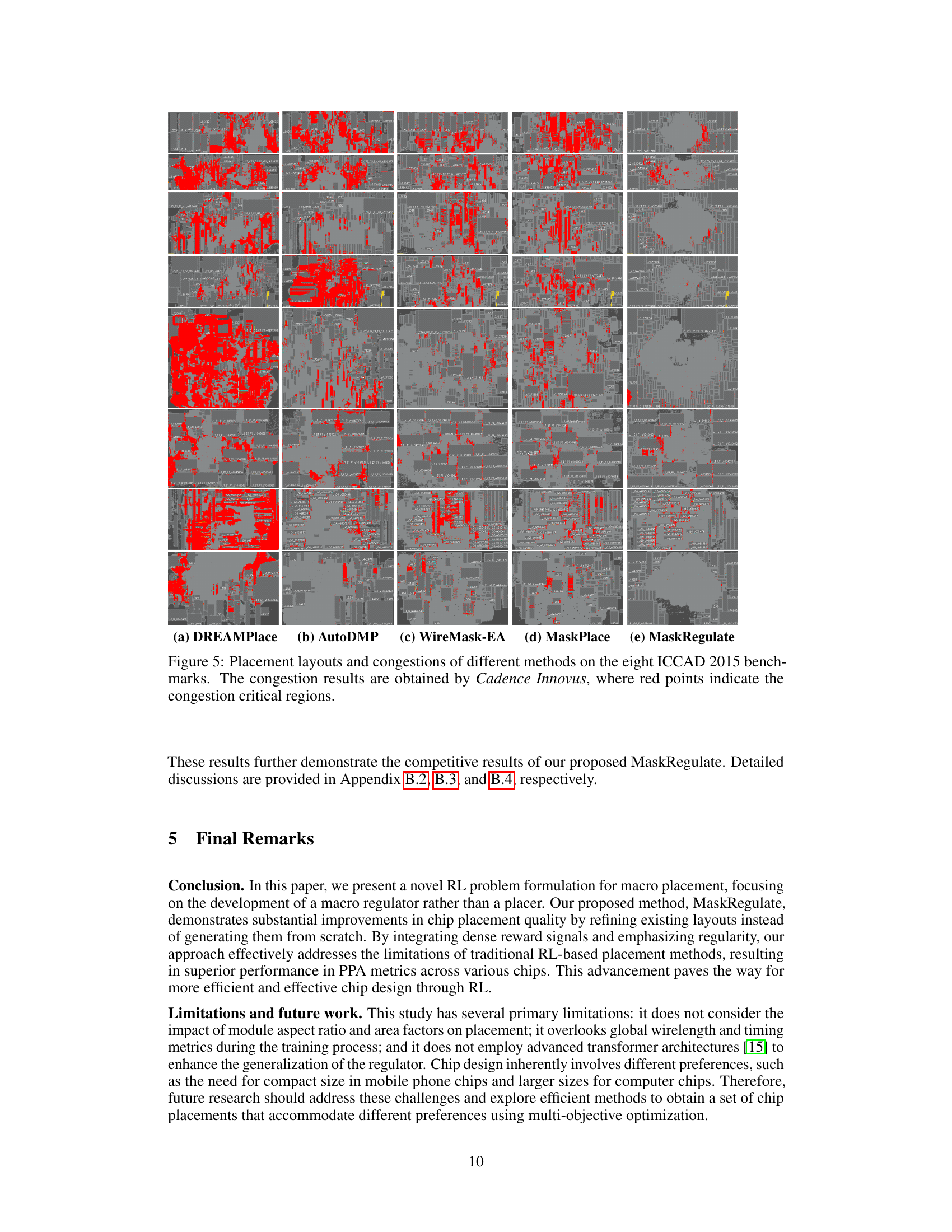

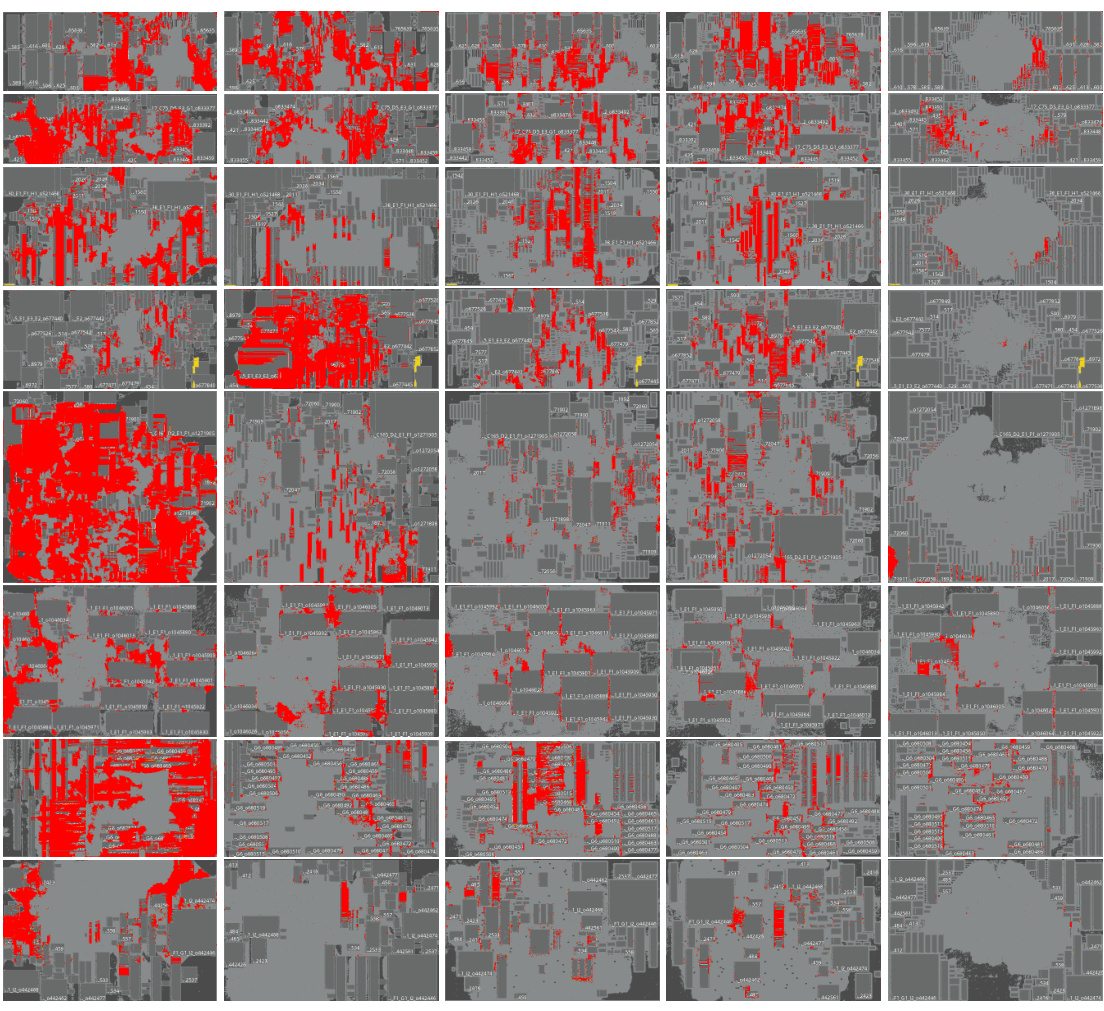

This figure compares the placement layouts and congestion levels produced by five different placement methods (DREAMPlace, AutoDMP, WireMask-EA, MaskPlace, and MaskRegulate) on eight benchmark circuits from the ICCAD 2015 dataset. Red areas highlight regions of high congestion, indicating potential routing difficulties. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of the MaskRegulate method in reducing congestion compared to other approaches.

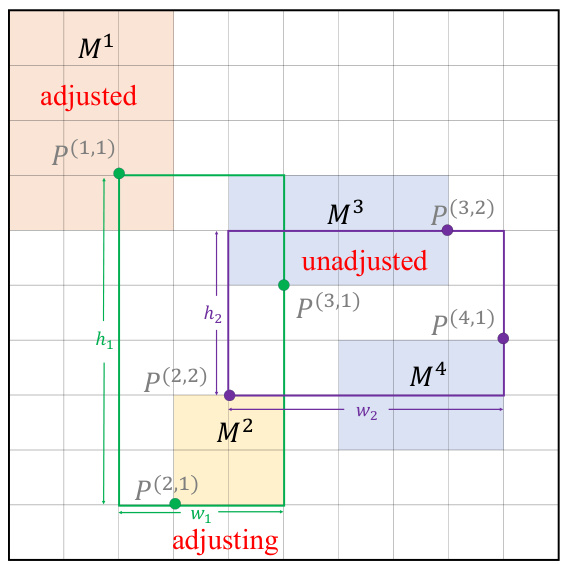

This figure illustrates how half-perimeter wirelength (HPWL) is calculated. It shows a chip canvas with modules (M1, M2, M3, M4) and their pins (P(i,j)). Some modules are ‘adjusted’, meaning their positions are fixed, and others are ‘adjusting’, meaning their positions are being optimized. The figure demonstrates how to compute HPWL for two nets, one in green and one in purple, by calculating the horizontal and vertical distances between the pins of each net. The figure visually explains the concept of HPWL as a proxy metric for the total wirelength of nets in the placement solution.

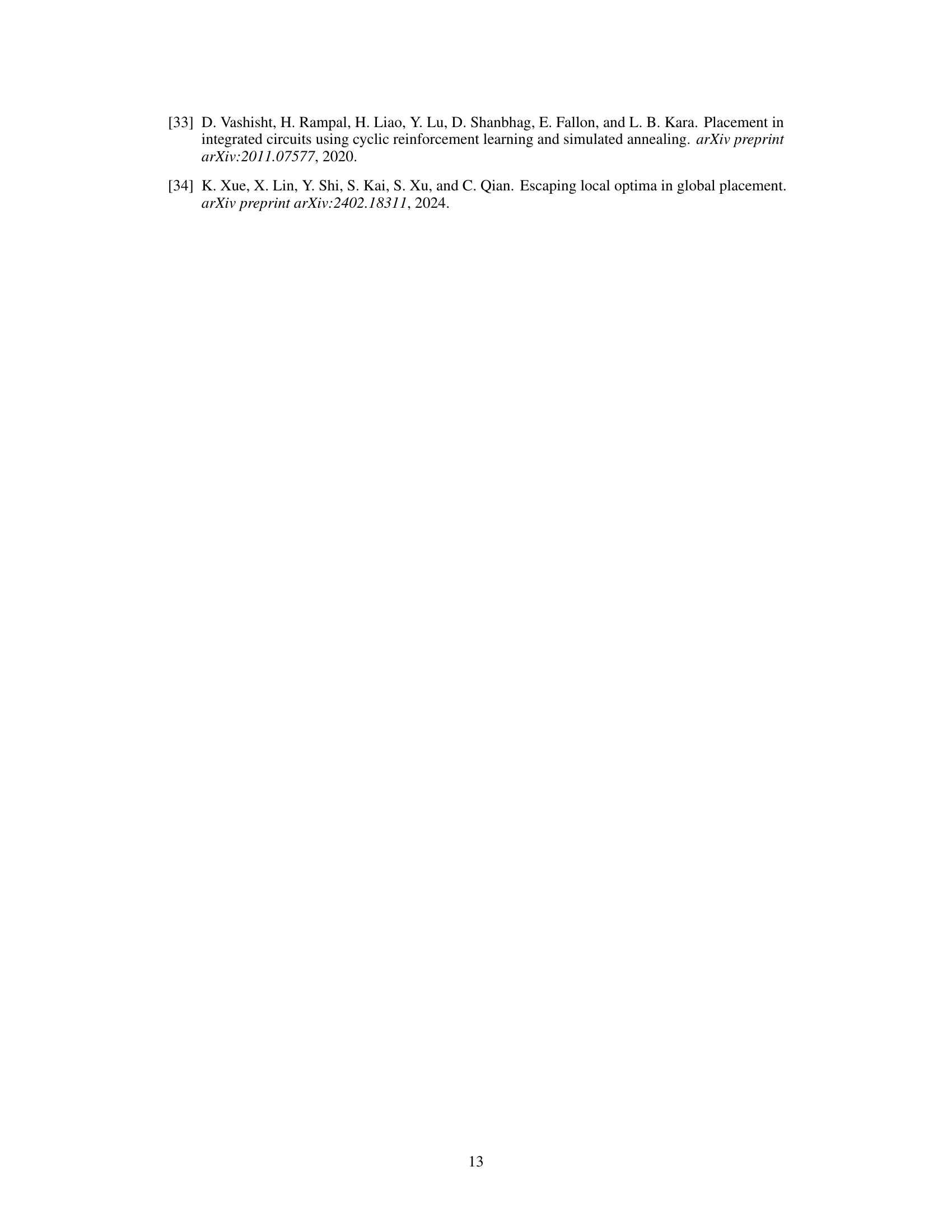

More on tables

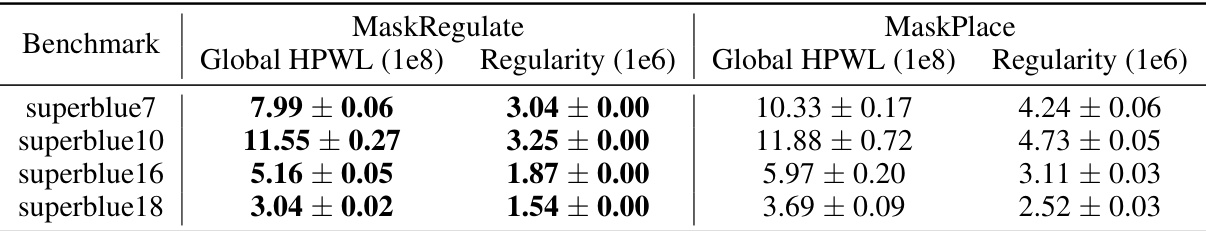

This table presents the generalization performance of MaskRegulate and MaskPlace. The models were pre-trained on four chips from the ICCAD 2015 benchmark and then tested on four unseen chips. The table shows the Global HPWL (half-perimeter wirelength) and Regularity for each method on each of the test chips. The best results for each metric are highlighted in bold, indicating how well each method generalizes to unseen data.

This table presents a comparison of different macro placement methods using both proxy metrics (Global HPWL and Regularity) and actual PPA metrics (obtained using Cadence Innovus). The proxy metrics provide quick estimates of placement quality, while the PPA metrics represent the final chip performance. The table compares DREAMPlace, AutoDMP, WireMask-EA, MaskPlace, and the proposed MaskRegulate method across various benchmark chips, showing the best results in bold.

This table presents a comparison of various macro placement methods using both proxy metrics (global HPWL and regularity) and actual PPA metrics obtained using Cadence Innovus. The proxy metrics offer a quick estimate of placement quality, while the PPA metrics provide more comprehensive evaluation of power, performance, and area (PPA). Results are shown for eight different chips from the ICCAD 2015 benchmark suite.

This table presents a comparison of different macro placement methods on the ICCAD 2015 benchmark. It shows results for both proxy metrics (Global HPWL and Regularity, which are used to estimate placement quality before detailed routing) and actual PPA (power, performance, and area) metrics obtained using Cadence Innovus (a commercial EDA tool). PPA metrics include routed wirelength, congestion, negative slack (timing), and the number of violations. The table allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the methods’ effectiveness, considering both estimation-based and actual chip performance.

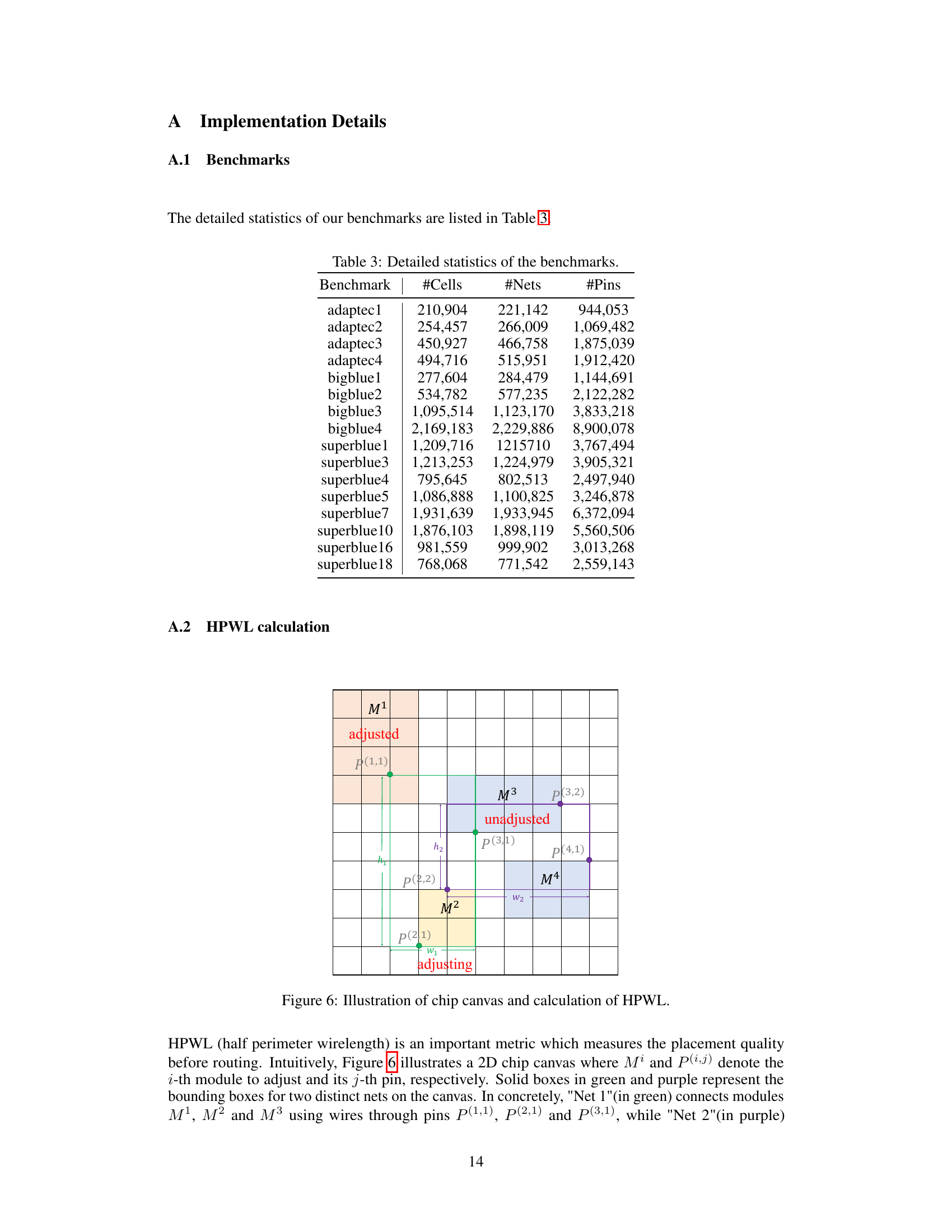

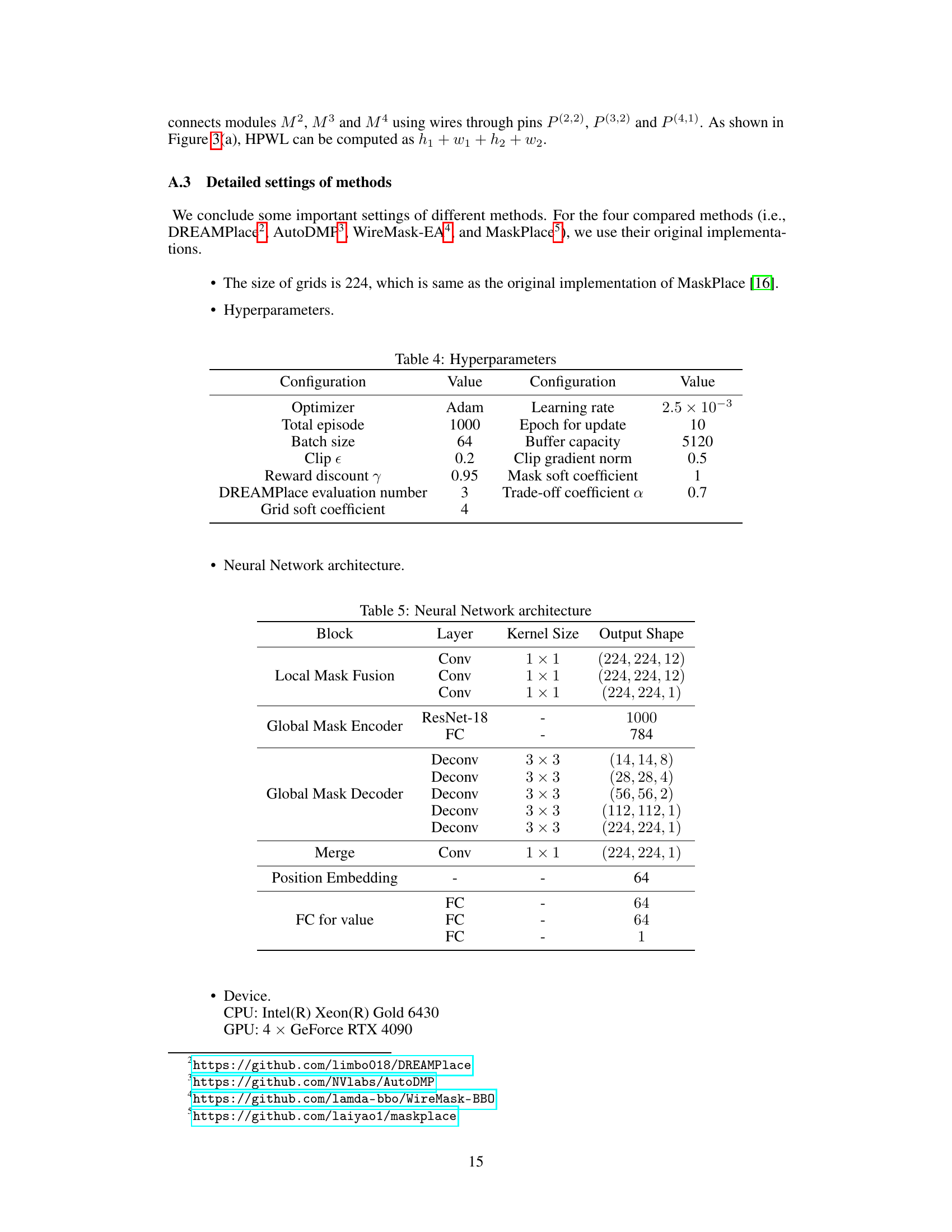

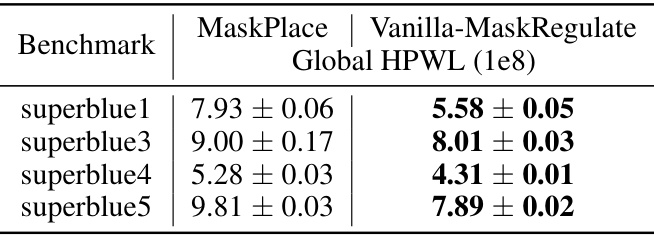

This table compares the performance of MaskPlace and Vanilla-MaskRegulate on four benchmark chips from the ICCAD 2015 dataset. The key difference between the two methods is in their problem formulation; all other components remain the same. The results are presented as Global HPWL (half perimeter wirelength), a proxy metric for placement quality. The best result for each chip is highlighted in bold.

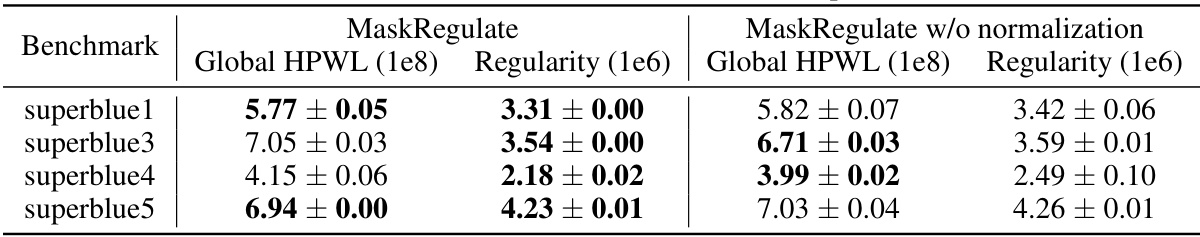

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the MaskRegulate model with and without normalization. The results are evaluated on four chips from the ICCAD 2015 benchmark dataset, focusing on two key metrics: Global HPWL (Half-Perimeter Wirelength) and Regularity. The best result for each metric on each chip is highlighted in bold. This ablation study helps determine the impact of normalization on the model’s overall effectiveness.

This table presents a comparison of different macro placement methods on the ICCAD 2015 benchmark. It shows both proxy metrics (Global HPWL and Regularity, which estimate placement quality before detailed routing) and actual PPA (Power, Performance, Area) metrics obtained using Cadence Innovus after standard cell placement and routing. The PPA metrics include routed wirelength, congestion (horizontal and vertical), worst negative slack (WNS), total negative slack (TNS), and number of violation points (NVP). The best result for each metric on each benchmark chip is highlighted.

This table presents a comparison of different macro placement methods on the ICCAD 2015 benchmark. It shows results for both proxy metrics (Global HPWL and Regularity, which estimate placement quality before detailed routing) and actual PPA (Power, Performance, Area) metrics obtained using Cadence Innovus (a commercial EDA tool) after completing the full design flow. The PPA metrics include routed wirelength, horizontal and vertical congestion, worst and total negative slack, and number of violation points. The table highlights the performance of MaskRegulate against other methods, showing its superior performance in several key metrics.

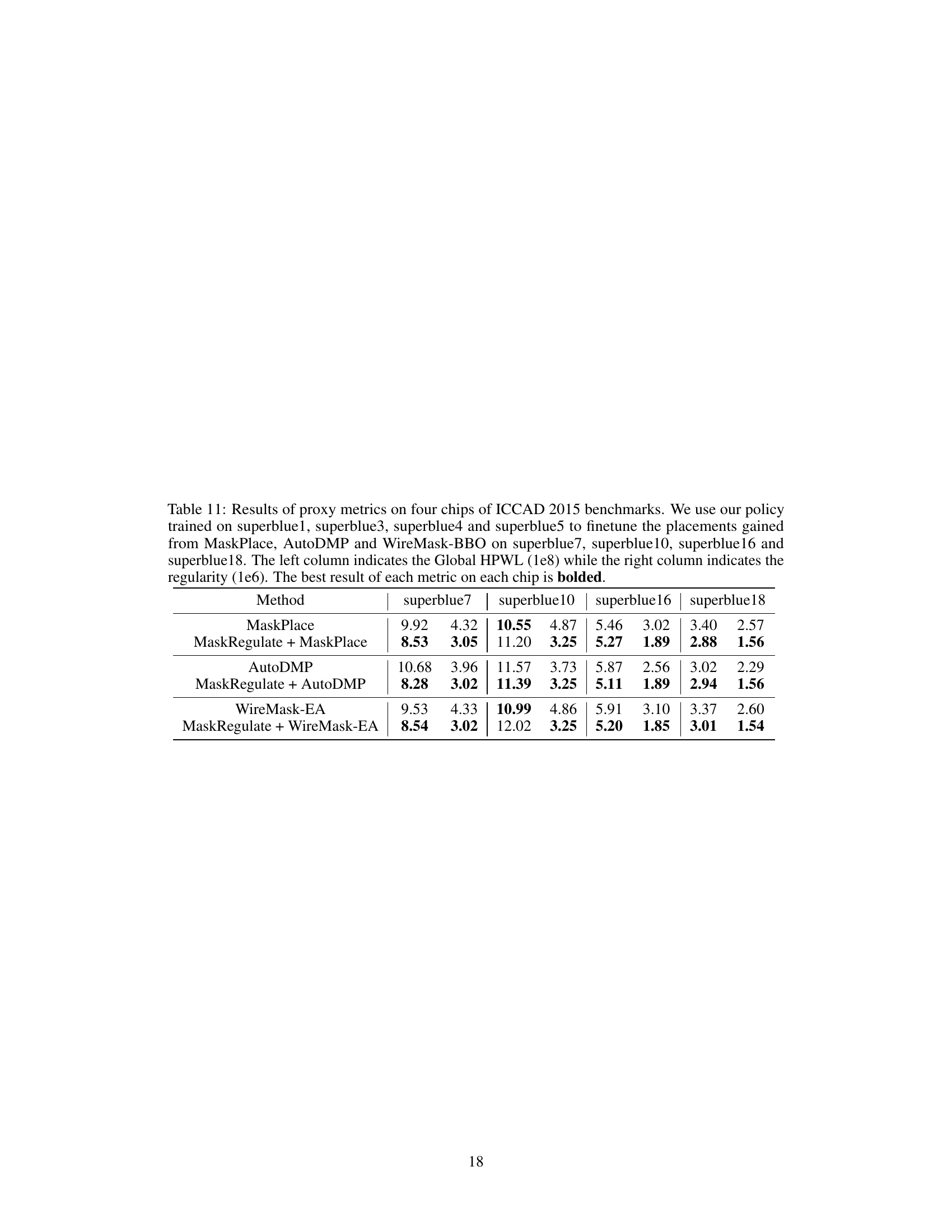

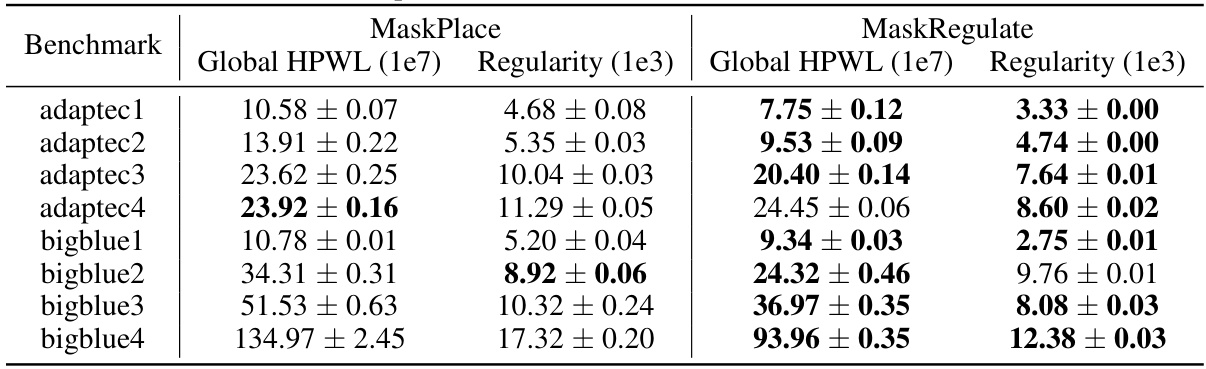

This table presents the results of applying MaskPlace and MaskRegulate models, pre-trained on four chips from the ICCAD 2015 benchmark, to eight different chips from the ISPD 2005 benchmark. The goal is to assess the generalization ability of these models. The table shows the Global HPWL (half-perimeter wirelength) and Regularity for each chip and method. The best-performing method for each metric on each chip is highlighted in bold.

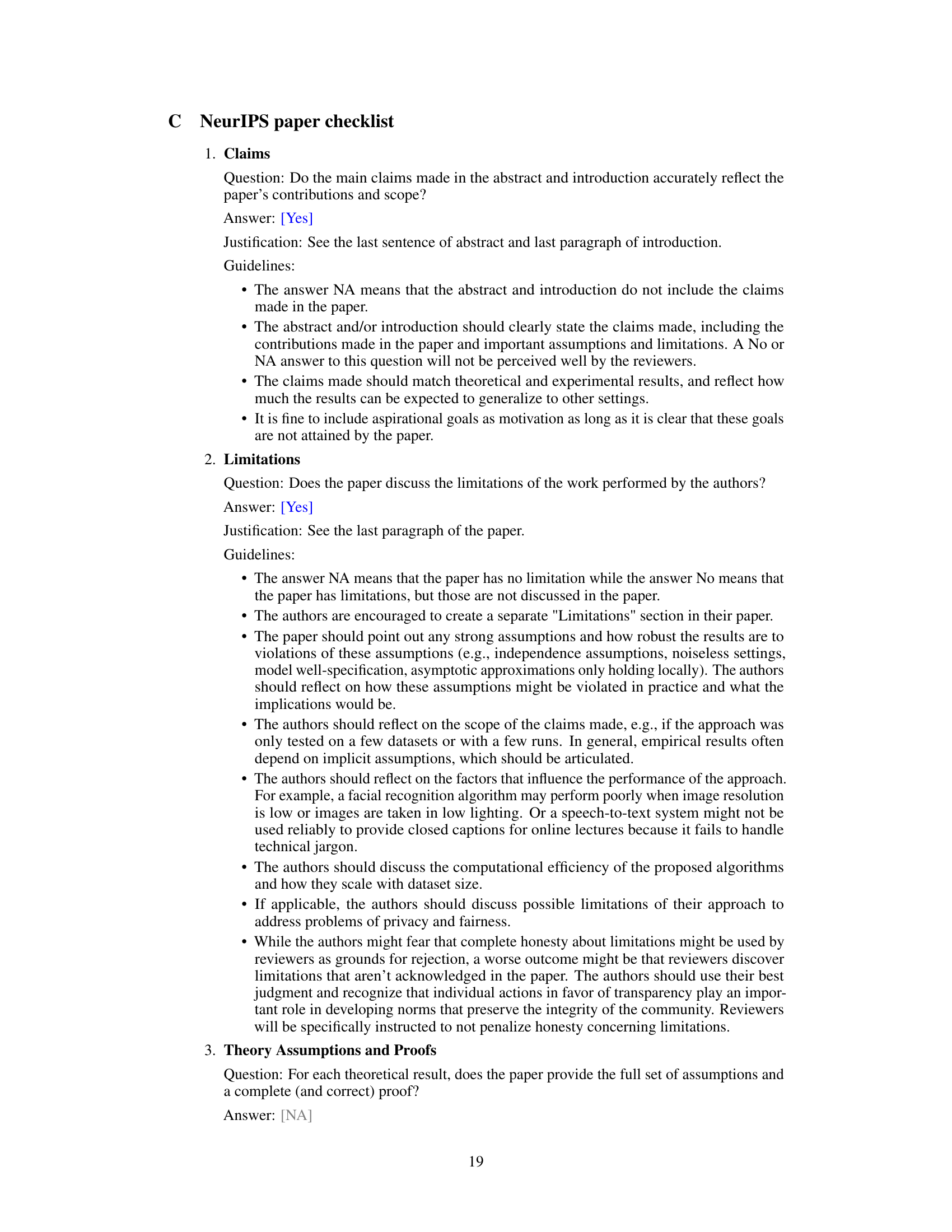

This table presents the results of applying MaskRegulate to refine placement results obtained from three different methods (MaskPlace, AutoDMP, and WireMask-EA). The experiments were conducted on four chips from the ICCAD 2015 benchmark (superblue7, superblue10, superblue16, and superblue18). The table shows the Global HPWL (half-perimeter wirelength) and regularity metrics after refinement. The best performing method for each metric on each chip is highlighted in bold. The results demonstrate MaskRegulate’s ability to improve upon existing placements.

Full paper#