TL;DR#

Multi-object 3D grounding, localizing objects in 3D scenes from textual descriptions, is challenging due to issues like the fixed number of object proposals in two-stage pipelines and the use of fixed camera viewpoints for feature extraction. Existing methods often struggle with computational complexity and inaccurate predictions for multi-object scenes. These limitations hinder real-world applications requiring precise and efficient object localization.

The authors introduce D-LISA, a novel approach that incorporates three key modules to address these issues. A dynamic vision module learns a variable number of object proposals, a dynamic multi-view renderer optimizes camera angles, and a language-informed spatial fusion module enhances contextual understanding. D-LISA demonstrates significant performance improvements (12.8% absolute increase) on the Multi3DRefer benchmark, validating its effectiveness for multi-object 3D grounding while maintaining robust performance on single-object tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances the field of multi-object 3D grounding, a crucial task for robotics and AI. D-LISA’s improvements, particularly the dynamic modules and language-informed spatial attention, provide a robust and efficient framework, opening avenues for more effective human-robot interaction and scene understanding. The results demonstrate a substantial performance leap over existing methods, showcasing the impact of innovative model design on real-world applications.

Visual Insights#

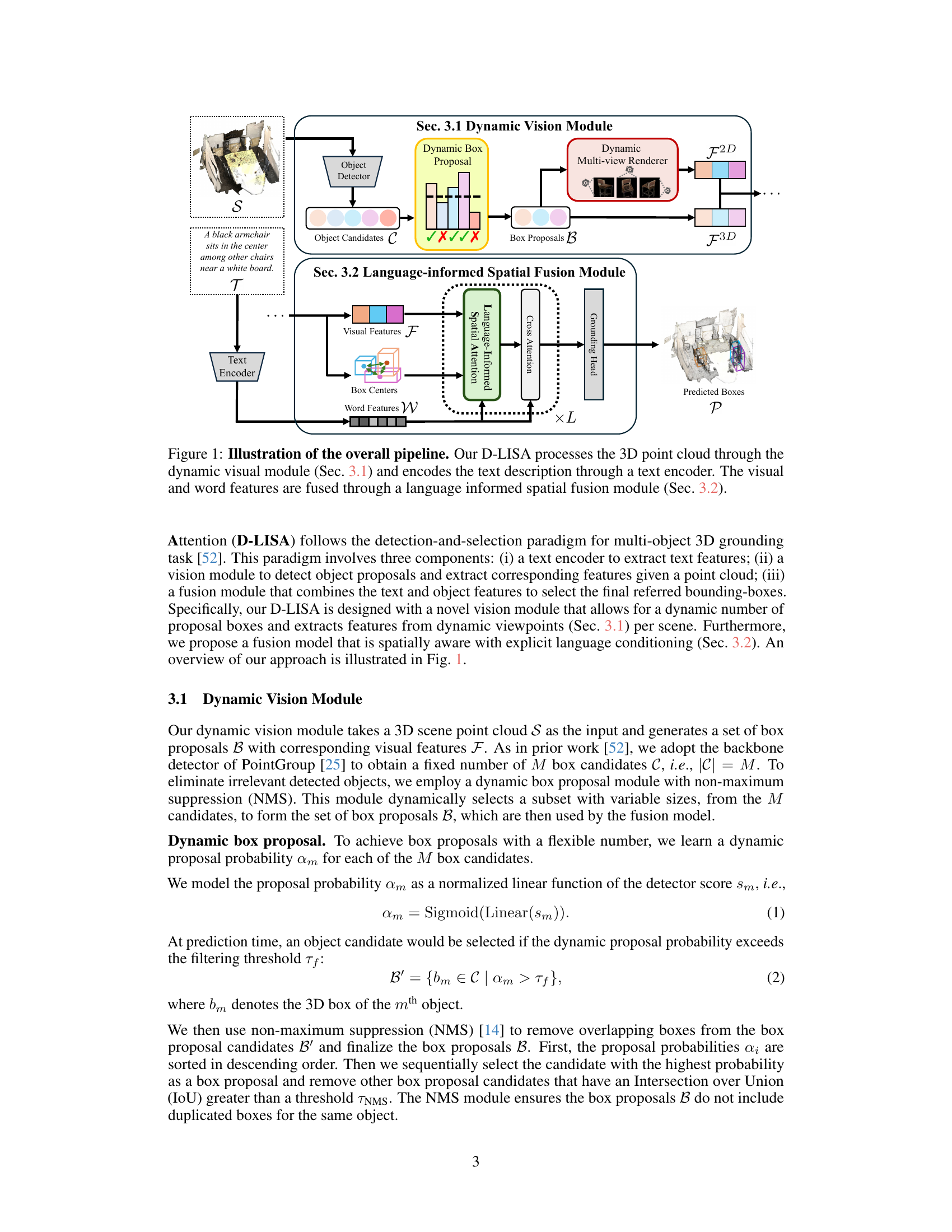

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the D-LISA model. The model consists of two main modules: a dynamic vision module and a language-informed spatial fusion module. The dynamic vision module takes a 3D point cloud as input and generates a set of box proposals, which are then used by the fusion module. The language-informed spatial fusion module combines the text and object features to select the final referred bounding boxes. The figure shows the flow of data through the different components of the model, highlighting the key steps in the process.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the overall pipeline. Our D-LISA processes the 3D point cloud through the dynamic visual module (Sec. 3.1) and encodes the text description through a text encoder. The visual and word features are fused through a language informed spatial fusion module (Sec. 3.2).

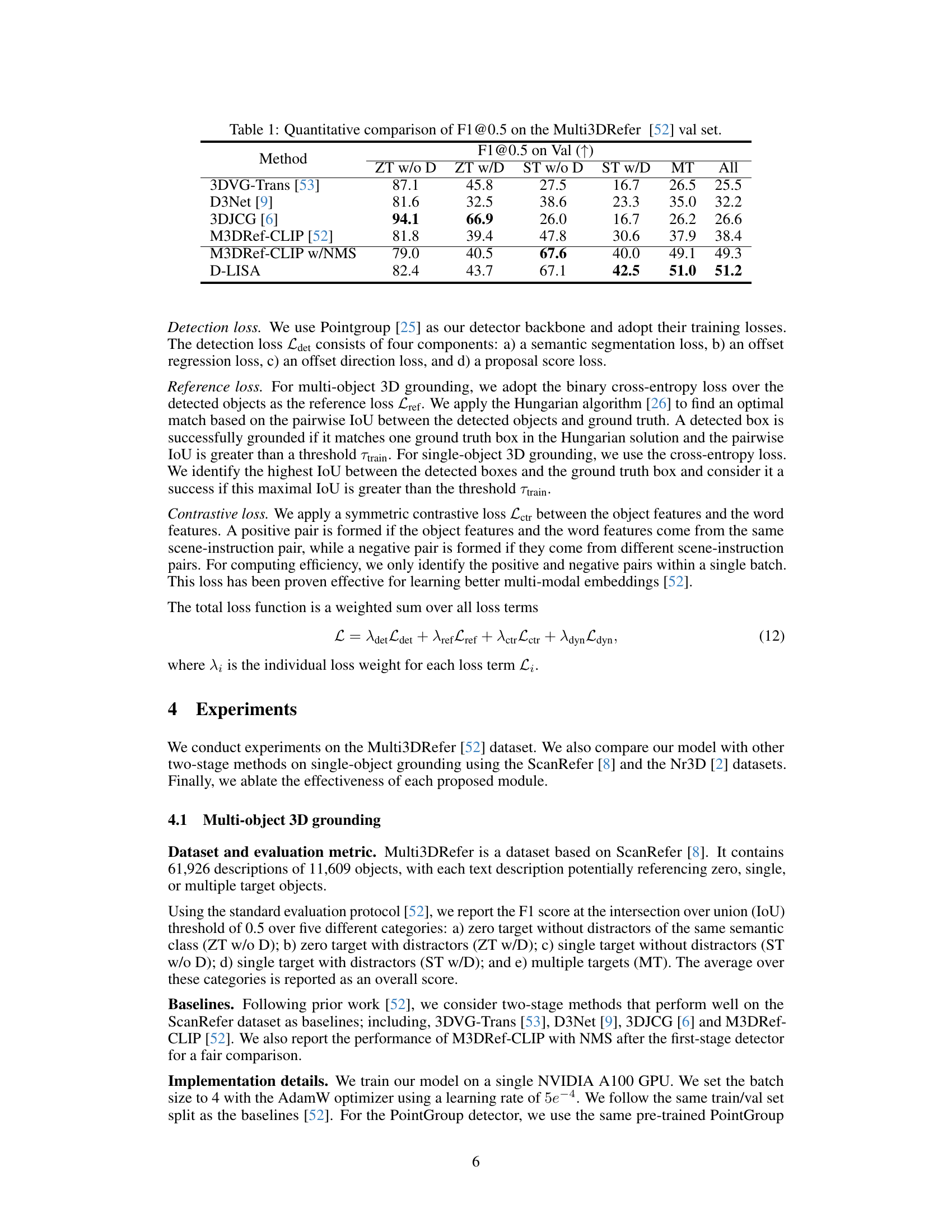

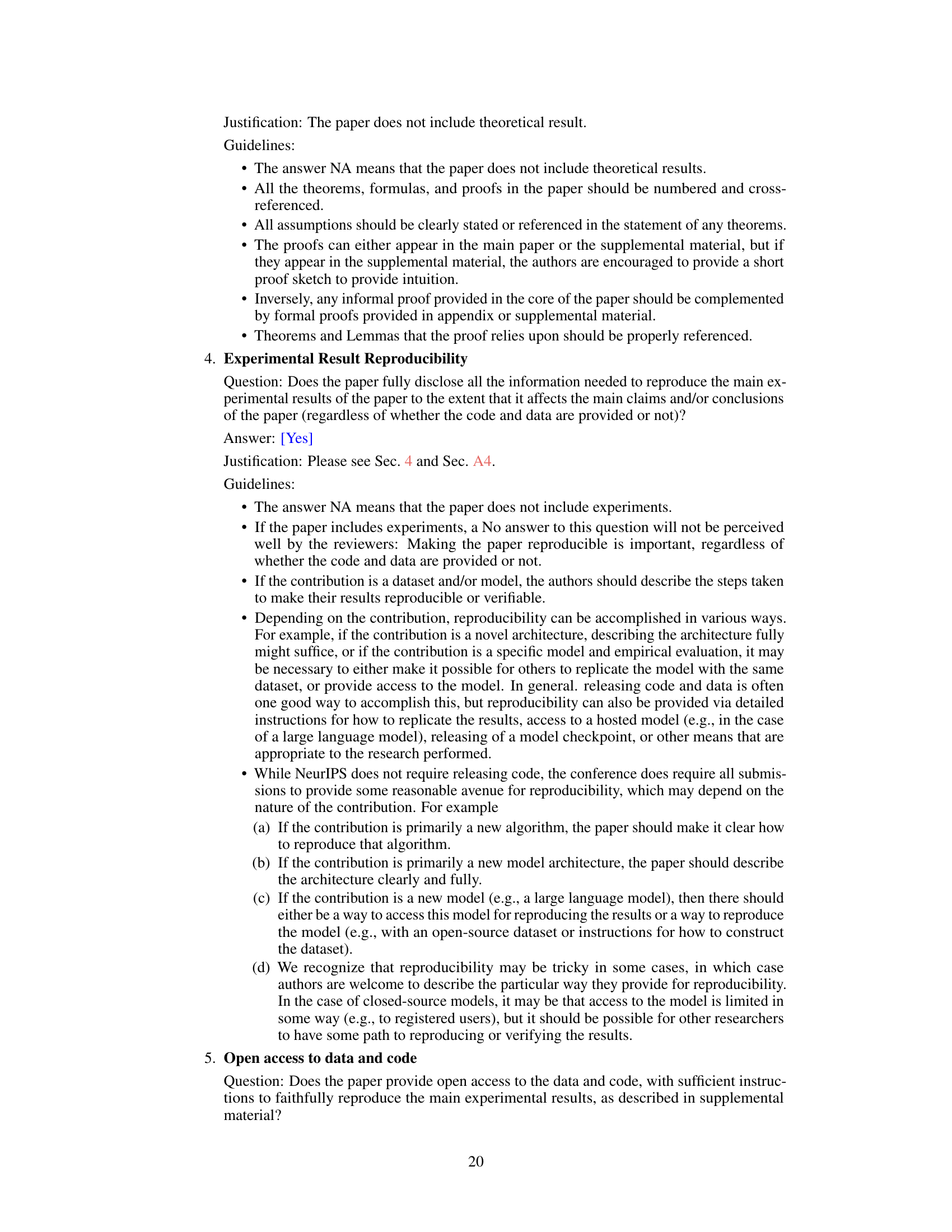

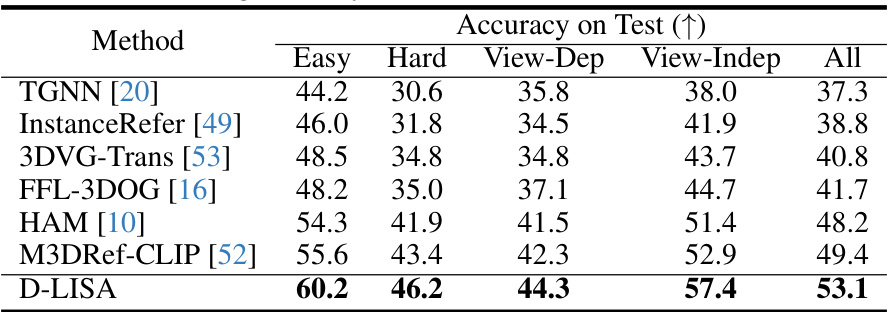

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the F1@0.5 score on the Multi3DRefer validation set. The F1@0.5 score is a metric used to evaluate the performance of multi-object 3D grounding models. The table compares the performance of the proposed D-LISA method against several state-of-the-art baselines. The comparison is broken down by several sub-categories, reflecting different levels of difficulty in the grounding task (ZT w/o D, ZT w/D, ST w/o D, ST w/D, MT, All). The results show that D-LISA outperforms the existing baselines by a significant margin, particularly in the more challenging scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of F1@0.5 on the Multi3DRefer [52] val set.

In-depth insights#

Dynamic Vision#

A dynamic vision system would be a significant advancement in computer vision. It would involve adapting to changing conditions such as lighting, viewpoint, and object motion. This contrasts with traditional static systems that assume a fixed environment. Key aspects of a dynamic vision system could include real-time object tracking and recognition, the ability to predict future states of objects from current and past observations, and robustness to noise and uncertainty. Active vision, where a system chooses its viewpoint or actions to improve understanding, could also be a component. A dynamic system might involve machine learning to adapt its parameters and strategies over time. The core challenge is to develop efficient and effective algorithms capable of handling the complexity of real-world scenarios, balancing accuracy and speed to meet real-time demands.

Spatial Fusion#

Spatial fusion in the context of 3D object grounding is a crucial step that integrates visual and linguistic information to accurately locate objects within a 3D scene. A strong spatial fusion module is critical because it must effectively reason about the spatial relationships between objects mentioned in a textual query and their corresponding locations in the point cloud. Successful methods leverage attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of visual features based on their relevance to the text description. This involves not just detecting individual objects, but also understanding their relative positions (e.g., “in front of,” “to the left of”) and distances. The challenge lies in handling the complexity and variability of spatial relationships, as well as the inherent ambiguity of natural language. Advanced techniques such as graph neural networks or transformers are often employed to model these relationships, allowing the model to reason more effectively and robustly about the spatial configuration of the scene. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the spatial fusion module is directly reflected in the accuracy and precision of the final 3D bounding boxes generated by the model.

Multi-Object 3D#

The concept of “Multi-Object 3D” suggests a research area focusing on the simultaneous detection and understanding of multiple objects within a three-dimensional space. This is a significant advancement beyond single-object 3D analysis, demanding more sophisticated algorithms to handle complex spatial relationships, occlusions, and potentially, object interactions. Key challenges include efficiently processing large 3D datasets, such as point clouds, while maintaining accuracy and robustness. The success of multi-object 3D analysis depends heavily on the development of advanced feature extraction and representation techniques that effectively capture both individual object properties and their contextual relationships within the scene. Furthermore, effective reasoning and inference methods are needed to disambiguate objects, resolve occlusions, and predict the objects’ identities and locations accurately. The applications of this technology are far-reaching, particularly within robotics, autonomous driving, augmented reality, and virtual reality, where a comprehensive 3D understanding of the environment is crucial.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, a well-executed ablation study provides crucial evidence supporting the claims made about the model’s design. By isolating the effects of each module or feature, it clarifies which parts are essential for achieving strong performance and which are redundant or even detrimental. A strong ablation study will show a clear trend of performance degradation as key components are removed, demonstrating the importance of those components. Conversely, if removing a component has little effect, that indicates a redundancy that could be explored for efficiency improvements. The results should also be discussed in relation to the overall model architecture and the hypotheses that informed the design. A thoughtful ablation study not only validates the model but also provides insightful guidance for future improvements and related research.

Future Works#

Future work for this research could explore several promising directions. Extending the model to handle more complex scenes with a higher density of objects and significant occlusions is crucial. Improving the robustness of the dynamic proposal module to better manage noisy or incomplete point cloud data would enhance reliability. Investigating more sophisticated spatial reasoning mechanisms beyond simple distance metrics, perhaps leveraging graph neural networks or other relational models, could significantly improve performance on multi-object grounding tasks. Additionally, exploring the potential of alternative architectures such as transformers that directly fuse textual and point cloud data could offer significant advantages. Finally, evaluating performance across a broader range of datasets with varying characteristics is important to confirm the generalizability of the proposed approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

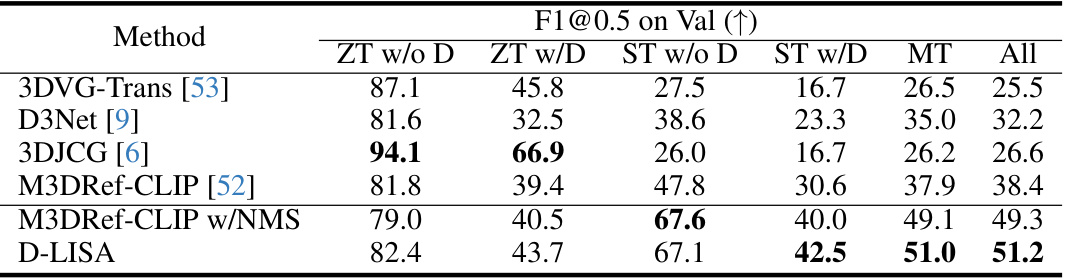

🔼 This figure illustrates the Language-Informed Spatial Attention (LISA) module. It shows how the module integrates visual features (F), sentence features (g), box proposals (B), box centers, and spatial distances (D) to produce a spatial score (B) which is then used to balance visual attention weights and spatial relations for improved contextual understanding. The process involves several steps including computing queries (Q) and keys (K) from the visual features, calculating spatial scores (B) based on the sentence and visual features, and then using a weighted combination of standard attention and spatial attention to refine the visual features. The final output is the language-informed spatial attention.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of language informed spatial attention (LISA). We model the object relations through spatial distance D. For each box proposal, a spatial score is predicted to balance the visual attention weights and spatial relations.

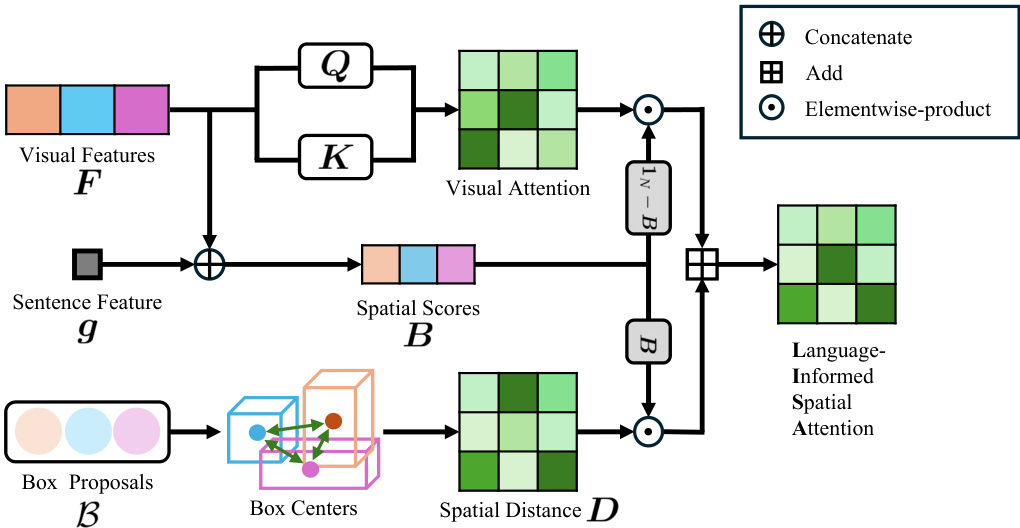

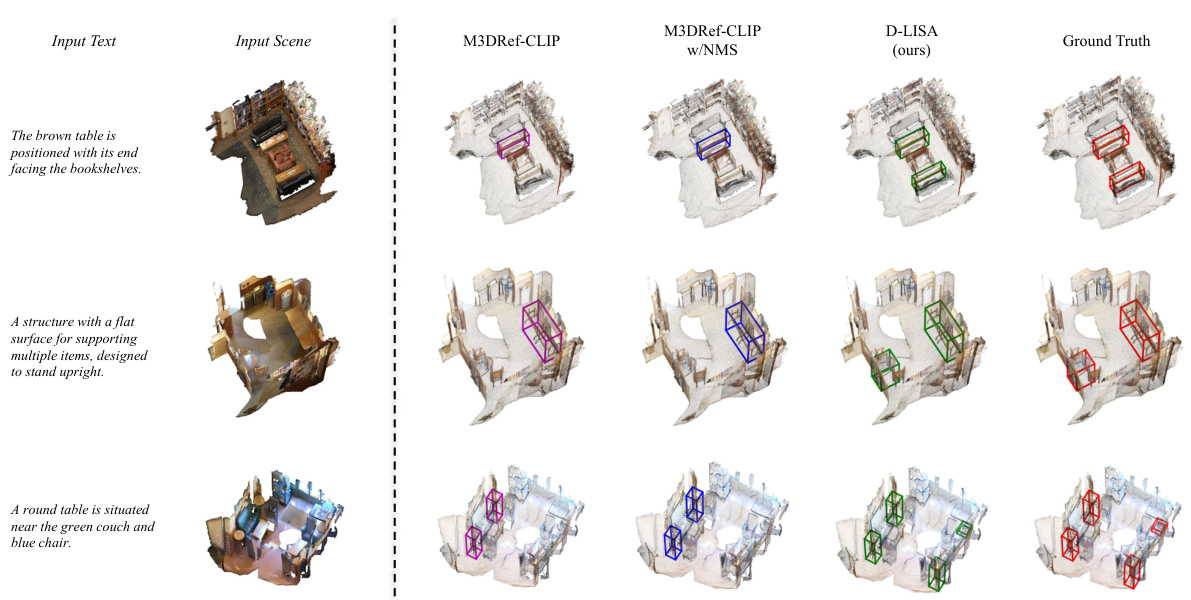

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the proposed D-LISA model with two other state-of-the-art methods (M3DRef-CLIP and M3DRef-CLIP w/NMS) on the Multi3DRefer validation set. Each row represents a different scene and text description. The visualizations demonstrate the ability of each model to accurately locate the target objects mentioned in the text description within the 3D scene. The ground truth is shown for comparison.

read the caption

Figure 3: Qualitative examples of Multi3DRefer val set. For each scene-text pair, we visualize the predictions of M3DRef-CLIP, M3DRef-CLIP w/NMS, D-LISA and ground truth labels in magenta/blue/green/red separately.

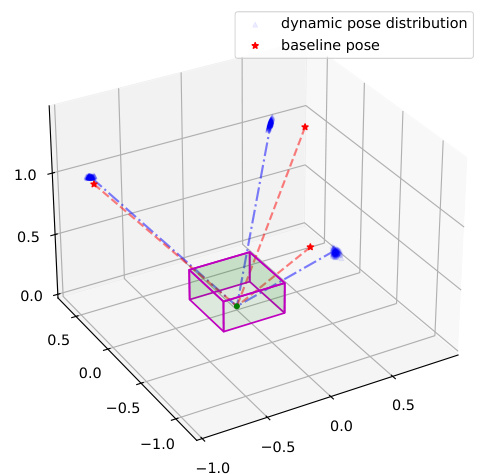

🔼 This figure shows the qualitative results of using a dynamic multi-view renderer in comparison to a fixed pose renderer. The left side shows the learned pose distribution, and the right side shows rendered 2D images using both dynamic and fixed camera poses. The dynamic pose adaptation improves rendering quality.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative results of dynamic multi-view renderer. On the left, we show the learned pose distribution over the Multi3DRefer val set and visualize one camera ray example. On the right, we present examples of comparison between rendering with fixed pose and dynamic learned pose.

🔼 This figure shows the qualitative results obtained by using a dynamic multi-view renderer. The left part of the figure displays the learned pose distribution and a sample camera ray from the Multi3DRefer validation set. The right part compares the rendering results obtained with fixed and dynamic camera poses. This comparison visually demonstrates the benefits of using dynamic camera poses in generating 2D image features.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative results of dynamic multi-view renderer. On the left, we show the learned pose distribution over the Multi3DRefer val set and visualize one camera ray example. On the right, we present examples of comparison between rendering with fixed pose and dynamic learned pose.

🔼 This figure shows qualitative results on the Multi3DRefer validation dataset. It provides a visual comparison of the bounding box predictions generated by three different models (M3DRef-CLIP, M3DRef-CLIP with Non-Maximum Suppression, and D-LISA) against the ground truth for several scene-text pairs. The color coding helps in differentiating the predictions from each model and the ground truth.

read the caption

Figure 3: Qualitative examples of Multi3DRefer val set. For each scene-text pair, we visualize the predictions of M3DRef-CLIP, M3DRef-CLIP w/NMS, D-LISA and ground truth labels in magenta/blue/green/red separately.

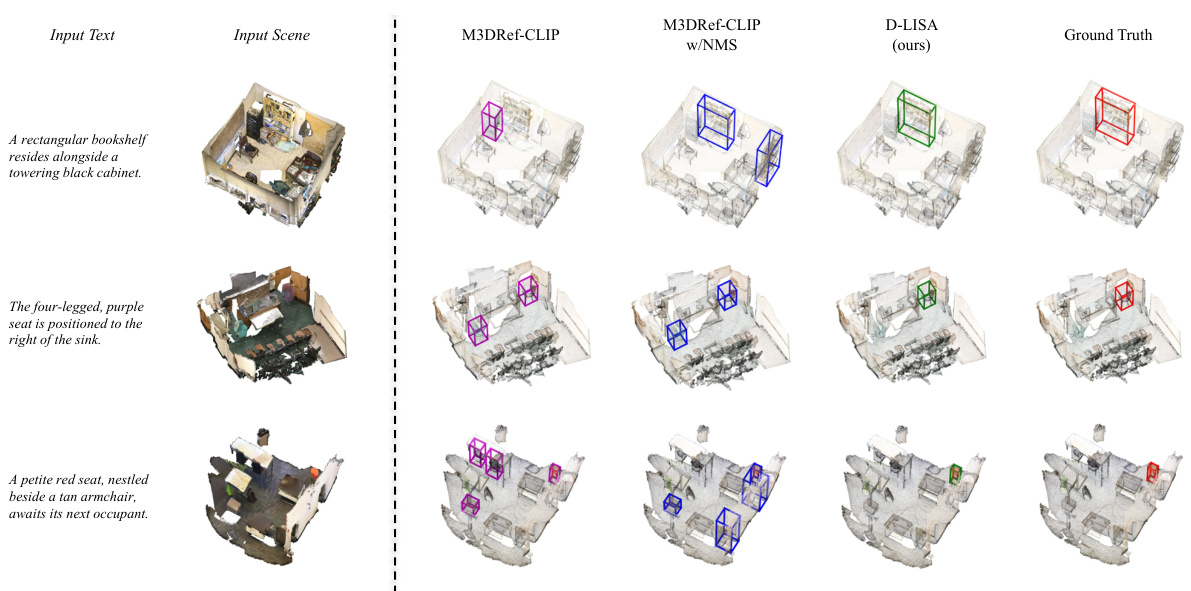

🔼 This figure presents qualitative results for the single-target with distractors (ST w/D) category of the Multi3DRefer validation set. It shows the predictions of three models (M3DRef-CLIP, M3DRef-CLIP with Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), and the proposed D-LISA model) along with the ground truth labels for three different scene-text pairs. Each pair shows a 3D point cloud of a scene and an associated textual description. The goal is to visually compare the accuracy of the bounding boxes predicted by the three methods for various objects described in the text. Different colors represent the boxes for different models or the ground truth.

read the caption

Figure A2: Additional qualitative examples of Multi3DRefer val set in ST w/D category. For each scene-text pair, we visualize the predictions of M3DRef-CLIP, M3DRef-CLIP w/NMS, D-LISA and ground truth labels in magenta/blue/green/red separately.

More on tables

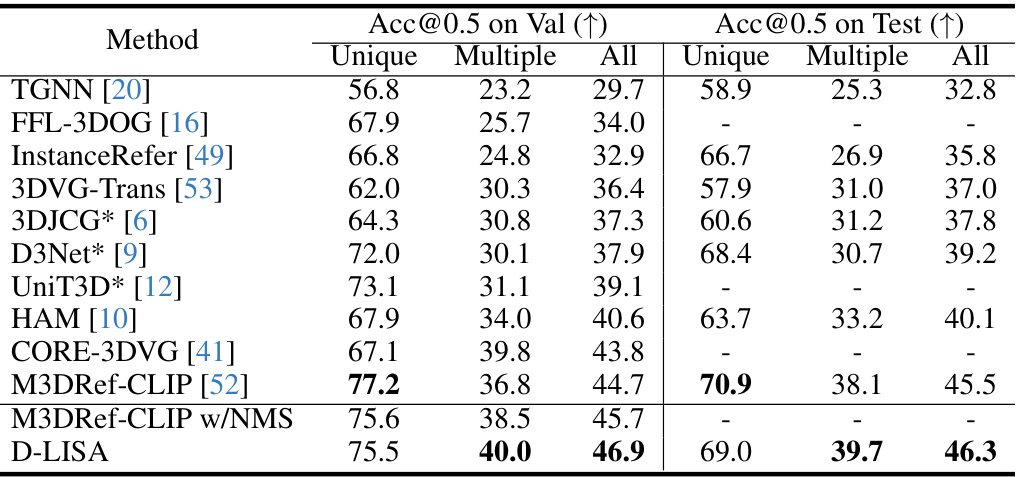

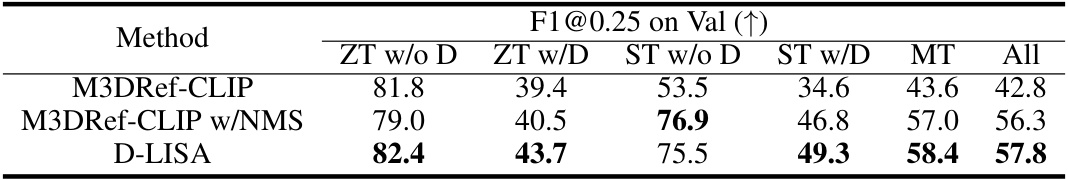

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of various methods on the ScanRefer dataset for single-object 3D grounding. The metric used is Acc@0.5 (accuracy at Intersection over Union threshold of 0.5). Results are shown separately for three categories of object instances: Unique, Multiple, and All (combination of Unique and Multiple). For methods marked with an asterisk (*), the reported results are the best achieved when using additional captioning training data. The table highlights the performance of the proposed D-LISA method in comparison to existing state-of-the-art methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Acc@0.5 of different methods on the ScanRefer dataset [8]. For joint models indicated by *, the best grounding performance with extra captioning training data is reported.

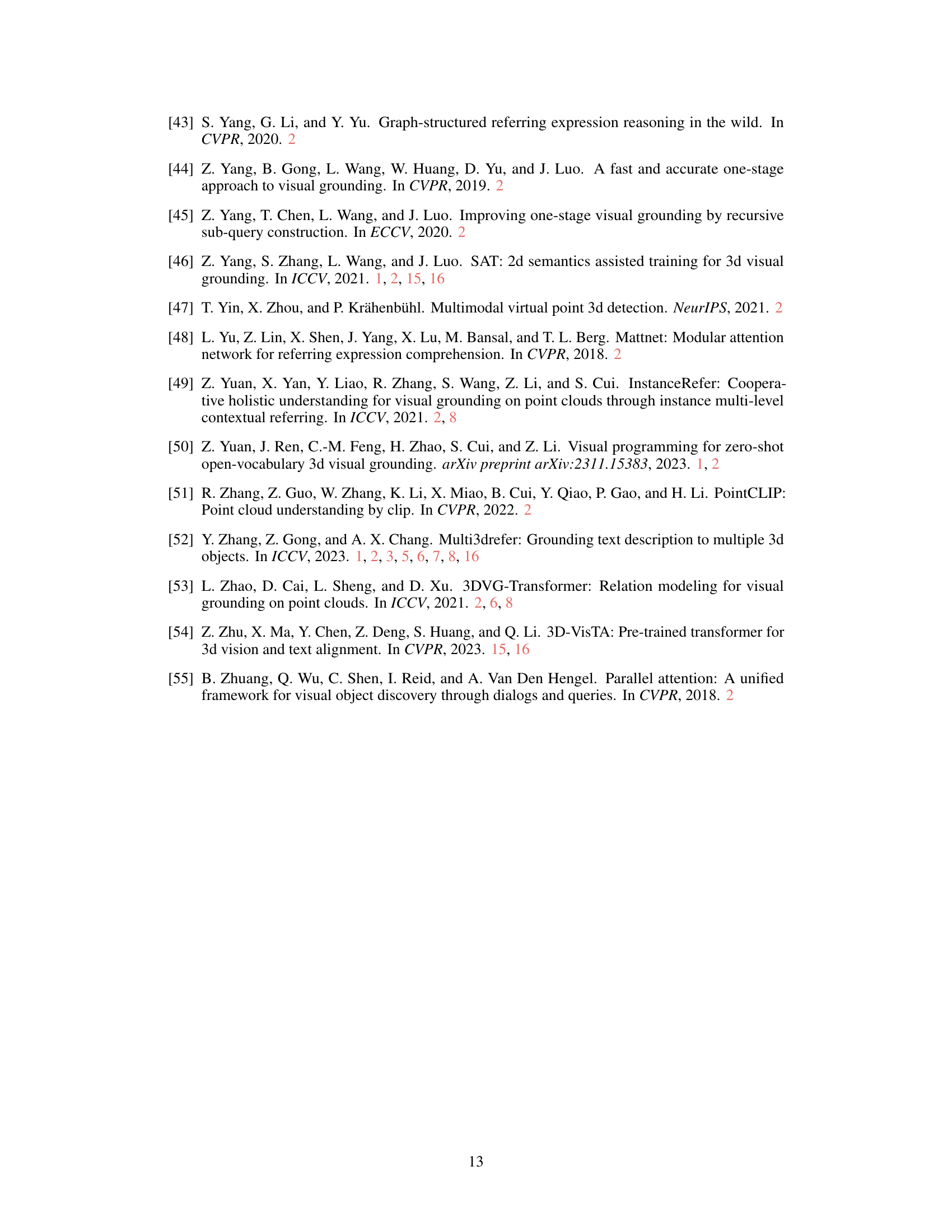

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of various methods on the Nr3D dataset for single-object 3D grounding. It breaks down the accuracy (Acc@0.5) across different subsets of the dataset categorized by difficulty (Easy, Hard), viewpoint dependency (View-Dep, View-Indep), and overall performance. The table allows for a comparison of D-LISA against several state-of-the-art baselines, highlighting the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach under various conditions.

read the caption

Table 3: Grounding accuracy of different methods on Nr3D dataset [2].

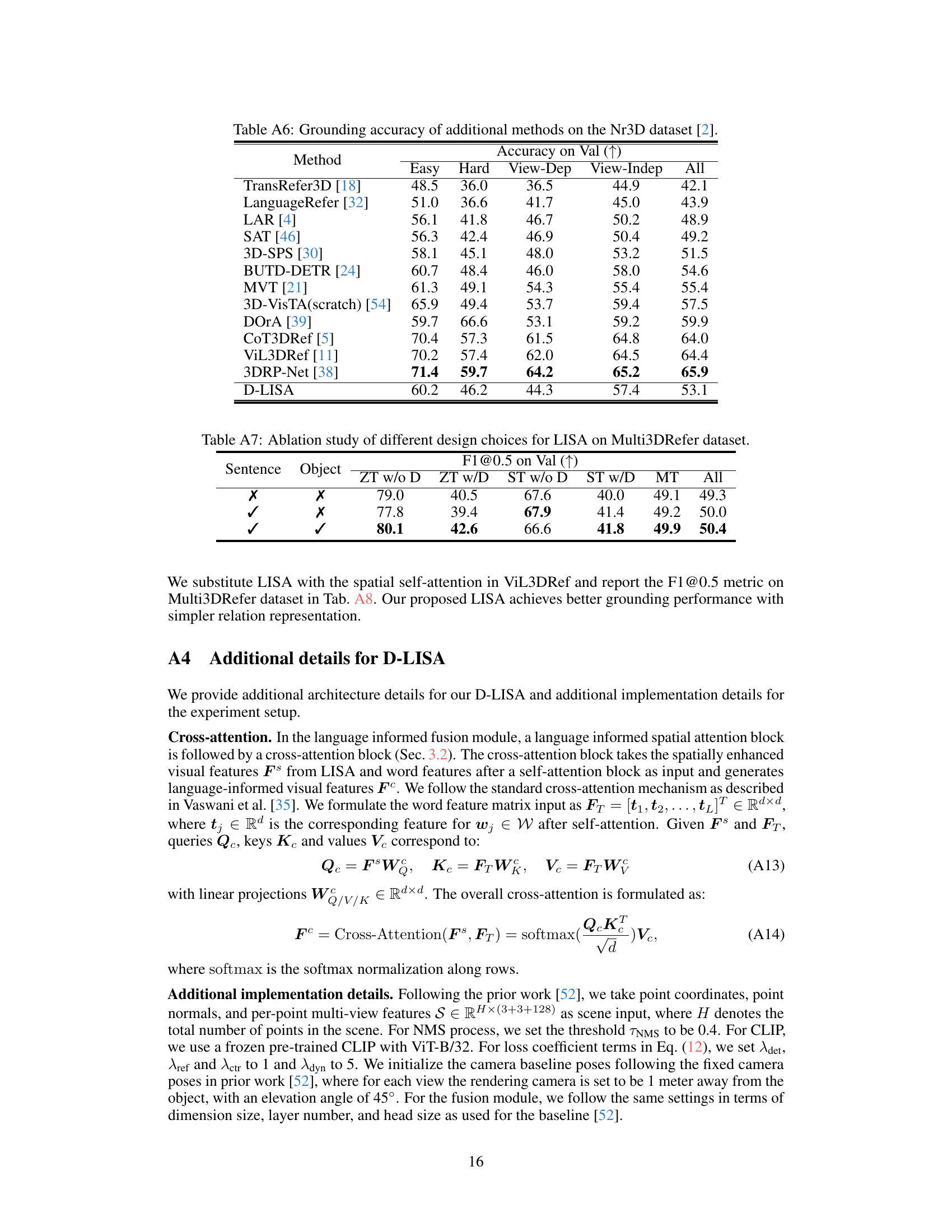

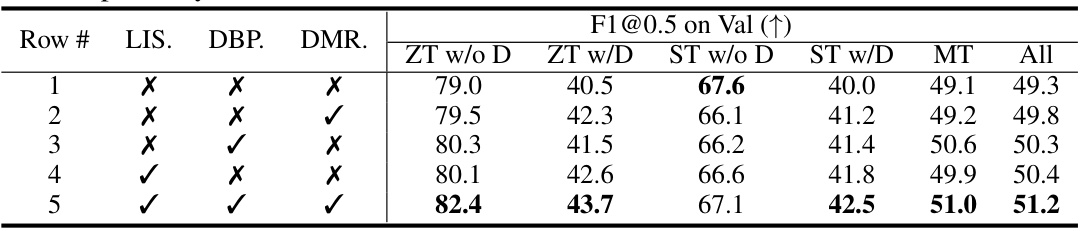

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results for the proposed D-LISA model. It shows the impact of each module (Language-informed spatial fusion, Dynamic box proposal, and Dynamic multi-view renderer) on the overall performance. By comparing different rows, we can see how each module contributes to the improvements in the F1@0.5 score across various sub-categories of the Multi3DRefer dataset.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study of proposed modules on Multi3DRefer dataset. 'LIS.', 'DBP.' and 'DMR.' stands for 'Language informed spatial fusion', ‘Dynamic box proposal', and 'Dynamic multi-view renderer' respectively.

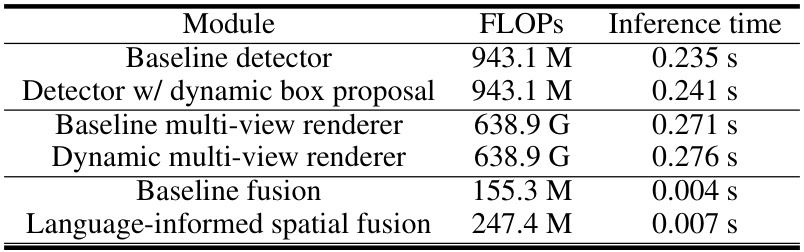

🔼 This table presents a breakdown of the computational cost, measured in FLOPs (floating-point operations) and inference time (in seconds), for each module of the proposed D-LISA model. It compares the computational cost of the baseline modules (detector, multi-view renderer, and fusion) with their dynamic counterparts. This allows for a quantitative analysis of the computational overhead introduced by the dynamic components. The table shows that the dynamic box proposal and multi-view renderer modules add minimal computational cost compared to their baseline versions. The dynamic components improve model accuracy while keeping the overall model efficient.

read the caption

Table 5: Computational cost for proposed modules during inference.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed D-LISA model against other state-of-the-art methods on the Multi3DRefer dataset. The F1@0.5 score, a common metric for evaluating object detection, is used to measure the performance of each model. The dataset is divided into various subcategories representing different complexities of scenes, including zero targets with or without distractors, single targets with or without distractors, and multiple targets. Each method’s F1 score is presented for each subcategory, allowing for a detailed comparison of model performance across diverse scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of F1@0.5 on the Multi3DRefer [52] val set.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results on different question types (Spatial, Color, Texture, Shape) by removing one module at a time (LIS, DBP, DMR). The F1@0.5 scores are reported for each ablation setting to demonstrate the individual contributions of each module to the overall performance. The baseline is when all modules are included.

read the caption

Table A2: Ablation studies on question types on Multi3DRefer dataset. ‘LIS.', ‘DBP.’ and ‘DMR.’ stands for ‘Language informed spatial fusion’, ‘Dynamic box proposal’, and ‘Dynamic multi-view renderer’ respectively. F1@0.5 results are reported.

🔼 This ablation study investigates the effect of varying the filtering threshold ((\tau_f)) on the model’s performance. The results, measured by F1@0.5, demonstrate that a threshold of 0.5 yields the best performance, suggesting an optimal balance between inclusiveness and selectivity in the dynamic box proposal module.

read the caption

Table A3: Ablation studies on the filtering threshold \(\tau_f\). F1@0.5 results are reported.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the F1@0.5 scores achieved by different methods on the Multi3DRefer validation set. The F1@0.5 score is a common metric for evaluating the performance of object detection and grounding models. The table shows the performance of several state-of-the-art methods, including 3DVG-Trans, D3Net, 3DJCG, M3DRef-CLIP (with and without NMS), and the proposed D-LISA method, across different categories of evaluation (ZT w/o D, ZT w/D, ST w/o D, ST w/D, MT, and All). This allows for a comprehensive comparison of the various approaches and highlights the improvements achieved by the proposed method.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of F1@0.5 on the Multi3DRefer [52] val set.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of various methods on the ScanRefer dataset, focusing on the accuracy at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 (Acc@0.5). It breaks down the results across different categories: ‘Unique’ (target object has a unique semantic class in the scene), ‘Multiple’ (target object has the same semantic class as other objects in the scene), and ‘All’ (the overall average). The table also distinguishes between validation and test set results. The asterisk (*) indicates that some methods have achieved their best results using supplementary caption training data.

read the caption

Table 2: Acc@0.5 of different methods on the ScanRefer dataset [8]. For joint models indicated by *, the best grounding performance with extra captioning training data is reported.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different methods’ performance on the Nr3D dataset for single-object 3D grounding. The dataset is divided into subsets based on difficulty (Easy, Hard) and viewpoint dependence (View-Dep, View-Indep). The accuracy is measured as the percentage of correctly identified objects. The table allows for a comparison of D-LISA’s performance against other state-of-the-art methods across various difficulty levels and viewpoints.

read the caption

Table 3: Grounding accuracy of different methods on Nr3D dataset [2].

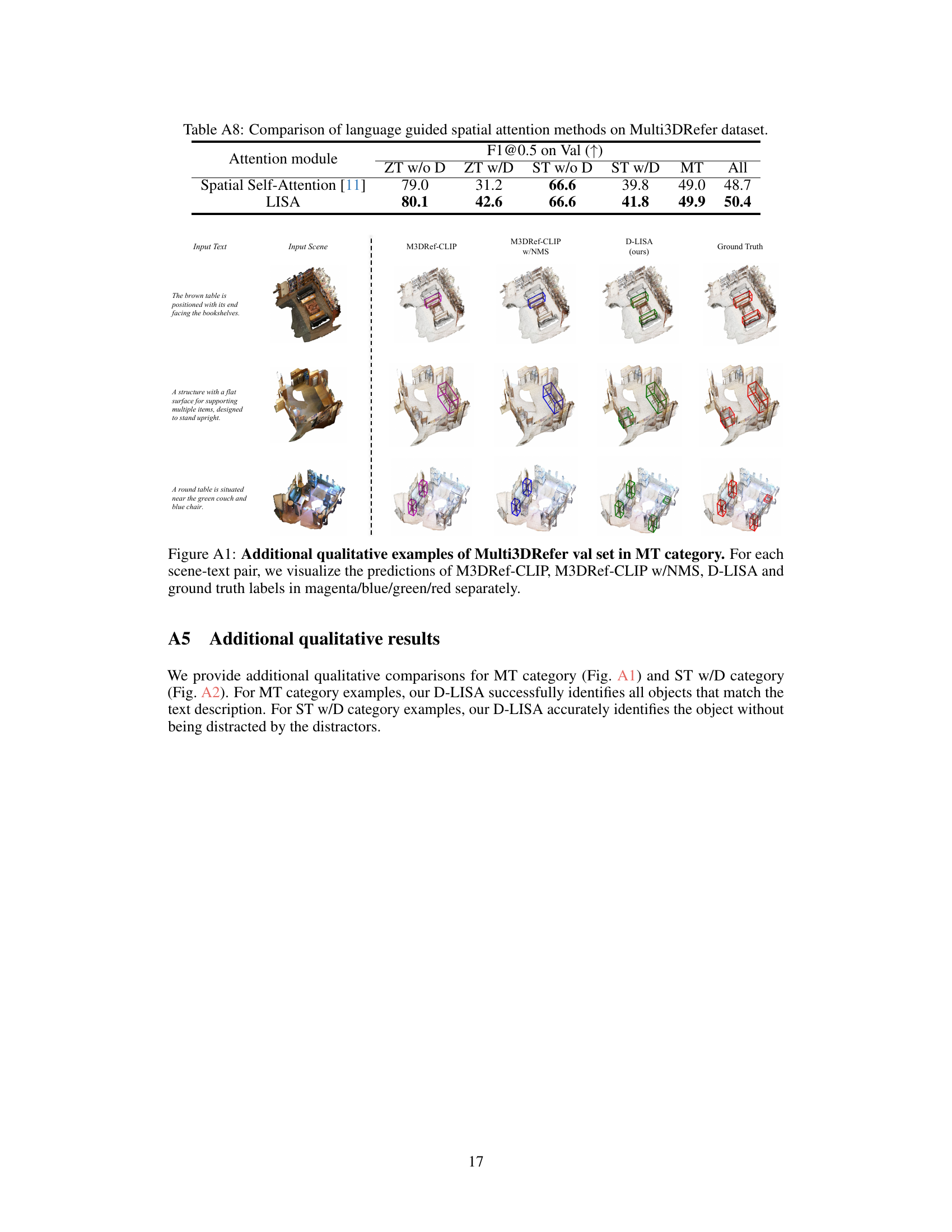

🔼 This table presents an ablation study comparing the performance of two different spatial attention mechanisms: the standard spatial self-attention mechanism and the proposed language-informed spatial attention (LISA) mechanism. The comparison is done across different subcategories of the Multi3DRefer dataset, allowing assessment of their impact on various scene complexities (i.e., presence or absence of distractors with the same semantics). The results showcase the effectiveness of LISA in improving grounding performance.

read the caption

Table A8: Comparison of language guided spatial attention methods on Multi3DRefer dataset.

🔼 This table compares the performance of two different spatial attention mechanisms: the Spatial Self-Attention from ViL3DRef and the proposed Language-Informed Spatial Attention (LISA). The comparison is done across different sub-categories of the Multi3DRefer dataset (ZT w/o D, ZT w/D, ST w/o D, ST w/D, MT, All) which represent varying levels of complexity in the task. The F1@0.5 metric is used to evaluate performance across these sub-categories, showing a slight improvement by the proposed LISA method.

read the caption

Table A8: Comparison of language guided spatial attention methods on Multi3DRefer dataset.

Full paper#