TL;DR#

High-dimensional Linear Programs (LPs) pose significant computational challenges. While random projections offer a solution by reducing LP size, their solution quality can be suboptimal. This work explores a novel data-driven approach, learning projection matrices from data to enhance solution quality.

The proposed data-driven approach learns projection matrices from training LPs, applies them to new instances to reduce dimensionality before solving. The paper provides both theoretical generalization bounds, ensuring learned projections generalize well to unseen LPs, and practical learning algorithms. Experiments demonstrate improved solution quality and significantly faster solving times compared to existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on high-dimensional linear programming problems. It offers novel data-driven projection methods that significantly improve solution quality while reducing computation time. The theoretical generalization bounds and practical learning algorithms proposed can directly influence various fields leveraging LPs. This research also opens new avenues for further investigation in data-driven algorithm design and optimization.

Visual Insights#

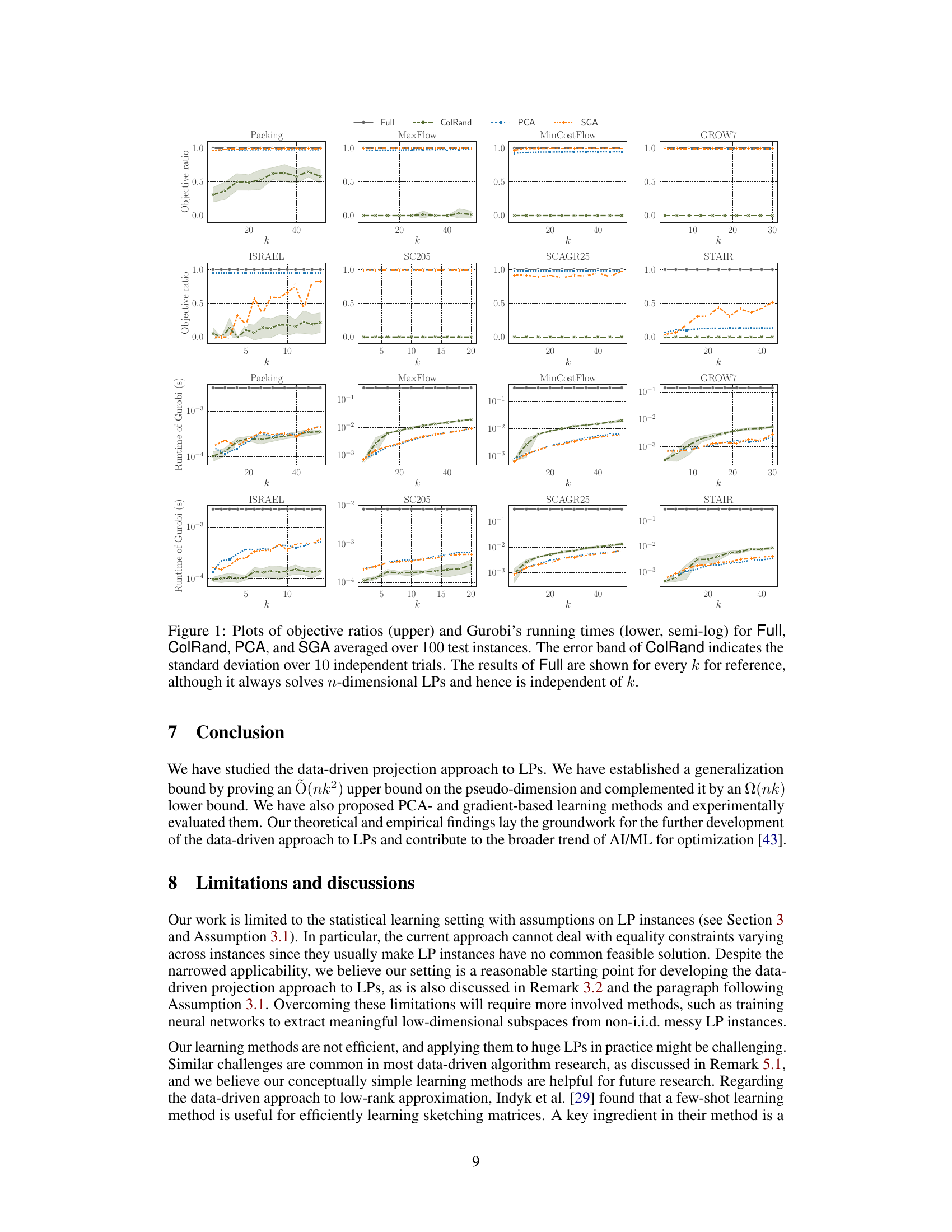

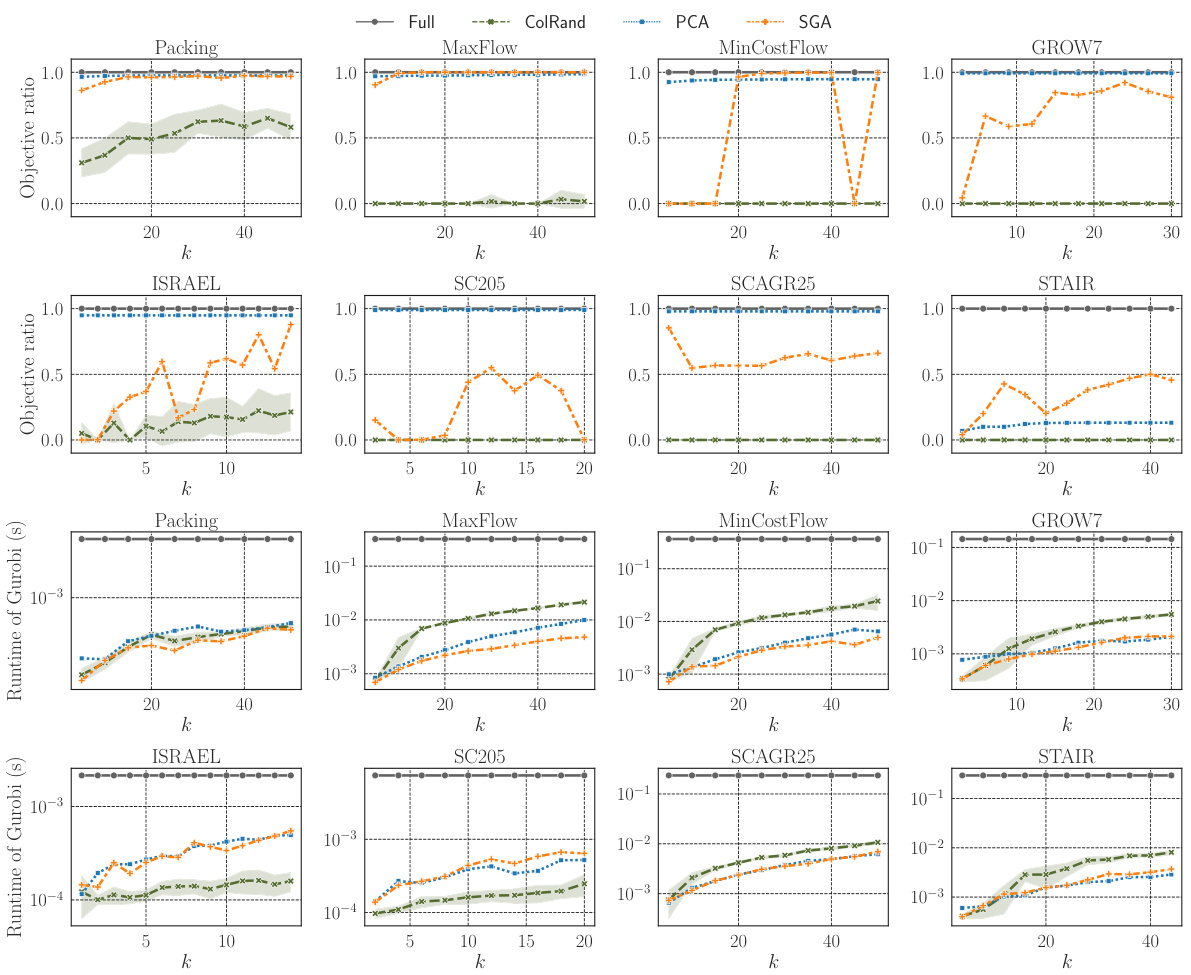

🔼 This figure presents the results of comparing four different methods for solving linear programming problems: Full, ColRand, PCA, and SGA. The top row shows the objective ratios (quality of solution) for each method across different datasets (Packing, MaxFlow, MinCostFlow, GROW7, ISRAEL, SC205, SCAGR25, STAIR) as the reduced dimensionality (k) varies. The bottom row shows the corresponding running times using Gurobi solver. The error bars for ColRand represent the standard deviation across 10 independent runs, highlighting the variability inherent in this randomized approach. Full serves as a baseline, always solving the full-dimensional problem, allowing for comparison of solution quality and speed improvements offered by dimensionality reduction techniques.

read the caption

Figure 1: Plots of objective ratios (upper) and Gurobi's running times (lower, semi-log) for Full, ColRand, PCA, and SGA averaged over 100 test instances. The error band of ColRand indicates the standard deviation over 10 independent trials. The results of Full are shown for every k for reference, although it always solves n-dimensional LPs and hence is independent of k.

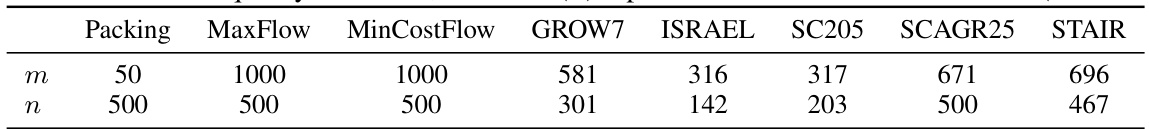

🔼 This table presents the dimensions of the inequality-form linear programs (LPs) used in the experiments. For each of the eight datasets (three synthetic and five real-world), it shows the number of constraints (m) and the number of variables (n). These dimensions are crucial in evaluating the scalability and efficiency of different LP-solving methods, especially those using dimensionality reduction techniques.

read the caption

Table 1: Sizes of inequality-form LPs, where m (n) represents the number of constraints (variables).

In-depth insights#

Data-Driven LP#

Data-driven linear programming (LP) represents a significant shift from traditional LP approaches. Instead of relying solely on established algorithms and solvers, data-driven LP leverages machine learning to enhance the efficiency and solution quality of solving LPs, especially those with high dimensionality. This approach involves learning projection matrices from training data. The trained matrices reduce the dimensionality of the LP before solving, leading to faster computation times. A crucial aspect is establishing a generalization bound to ensure learned projection matrices perform well on unseen instances, which necessitates analysis of the pseudo-dimension of the performance metrics. The practical implications focus on iterative, repetitive LP problems, where the learning phase’s computational cost is amortized over numerous LP instances. Successful implementation would demonstrate significantly improved performance compared to standard random projection methods, providing higher-quality solutions in much less time. However, challenges remain, including the potential overfitting of learned models to specific data patterns and the potential need for more sophisticated learning algorithms to handle complexities beyond straightforward linear projections.

Gen. Bound Analysis#

A Generalization Bound analysis in a machine learning context for linear programming problems would deeply investigate the required dataset size to guarantee that the learned projection matrices generalize well to unseen data. Key aspects would include determining the pseudo-dimension of the relevant function class, which measures the complexity of the learned projection matrices, thereby impacting sample complexity. The analysis would establish upper and lower bounds on the pseudo-dimension, ideally showing that the derived bounds are nearly tight. The results provide theoretical guarantees on the performance of data-driven projections for LPs, especially their ability to generalize from a training set to an unseen test set. This analysis is crucial for understanding the reliability and practical applicability of data-driven LP methods, highlighting the trade-off between accuracy and data requirements. It would significantly contribute to theoretical understanding, enabling researchers to design efficient and data-optimal algorithms.

PCA & Gradient#

The heading ‘PCA & Gradient’ suggests a hybrid approach to dimensionality reduction, combining the strengths of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and gradient-based optimization. PCA, a linear transformation technique, excels at identifying the principal components of a dataset, effectively capturing the maximum variance in a reduced-dimensional space. This is highly beneficial for initial dimensionality reduction in linear programming (LP), significantly speeding up computations. However, PCA’s effectiveness depends on data variance aligning with the optimal LP solution space. Gradient-based methods, directly optimizing the LP objective function through iterative gradient updates, can refine the projection matrix. This iterative approach offers the advantage of potential solution quality improvements, as it directly targets optimizing the LP objective rather than solely relying on data variance. The combination aims to leverage PCA’s efficiency for an initial projection and then utilize gradient methods to fine-tune the reduced-dimensional representation, leading to improved solution accuracy for subsequent LP solving. This approach also showcases the power of combining unsupervised learning (PCA) with supervised learning (gradient optimization) to achieve superior performance.

Empirical Results#

An effective empirical results section should present data clearly and concisely, highlighting key findings. It should compare different methods, using appropriate metrics such as objective ratios and running times. Visualizations like graphs and charts are essential for easy comprehension. The discussion should go beyond simply stating the results; it should connect them to the theoretical findings, explaining any discrepancies or unexpected results. For example, if a method unexpectedly underperforms, the results section should explore potential reasons, such as limitations in the data or algorithm. A strong empirical results section strengthens the paper’s overall impact by providing concrete evidence supporting the claims made. It should also clearly state what datasets were used and how they were preprocessed, ensuring reproducibility. Finally, it’s crucial to acknowledge limitations, such as the size of the datasets or the specific solvers used, to provide context for the results and prevent overgeneralization. Statistical significance should be addressed, and error bars provided where appropriate. Overall, a well-structured and insightful empirical results section can make a significant difference in the persuasiveness and impact of a research paper.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on data-driven projections in linear programming could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency of learning methods is crucial, potentially through the development of more sophisticated algorithms or leveraging recent advances in optimization and machine learning. Addressing limitations of current approaches, such as the restrictive assumptions about LP instances and the dependence on the availability of labeled training data, is also vital. Investigating the interaction between data-driven projections and specific LP solvers is another important direction; for instance, exploring how sparsity and solver-specific characteristics could be leveraged to further enhance efficiency and solution quality. Finally, extending these techniques to other optimization problems besides linear programming, like integer programming or non-convex optimization, would significantly broaden their applicability and impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

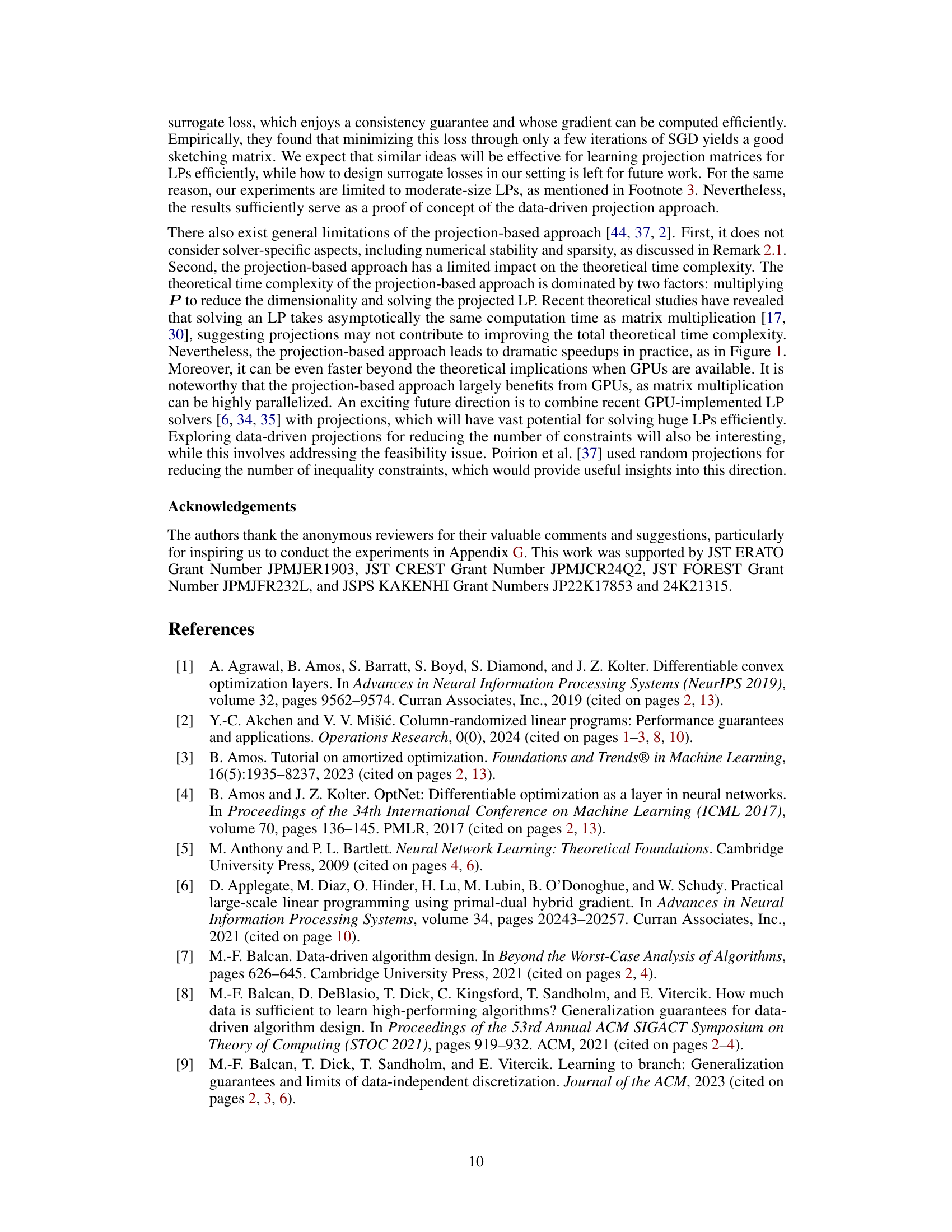

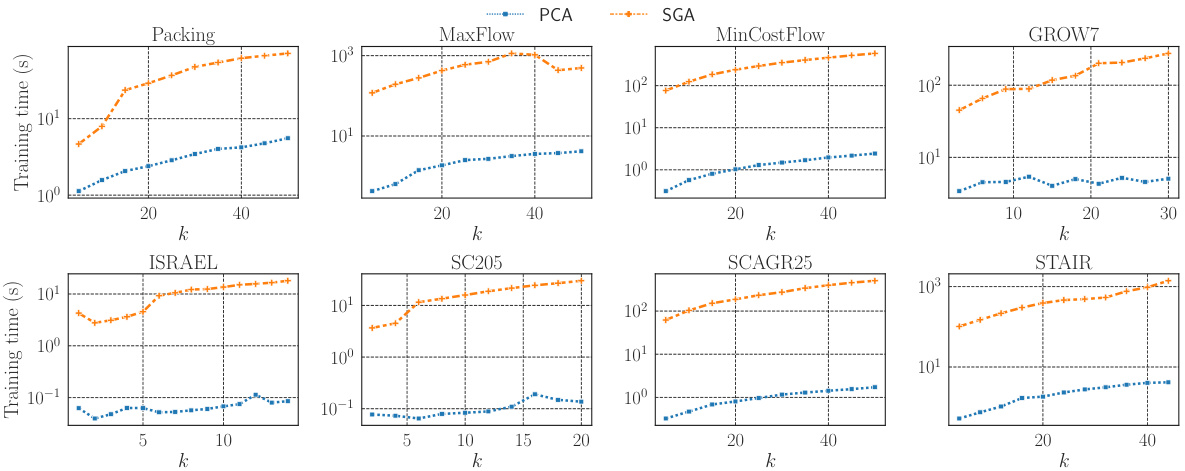

🔼 This figure shows the training times taken by PCA and SGA for learning projection matrices on training datasets of 200 instances. The training time for solving original LPs was not included. The figure demonstrates that SGA generally takes much longer than PCA because it iteratively solves LPs for computing gradients and quadratic programs for projection, whereas PCA only requires computing the top-(k-1) right-singular vectors of X - 1. The x-axis represents the reduced dimensionality (k) and the y-axis represents the training time in seconds. Different lines represent different datasets.

read the caption

Figure 2: Running times of PCA and SGA for learning projection matrices on 200 training instances.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of four different methods for solving linear programming (LP) problems: Full, ColRand, PCA, and SGA. The upper plots show the objective ratios (the objective value obtained by each method divided by the optimal objective value) for each method across eight different datasets (Packing, MaxFlow, MinCostFlow, GROW7, ISRAEL, SC205, SCAGR25, and STAIR). The lower plots show the corresponding running times of Gurobi, a commercial LP solver, for each method. The x-axis represents the reduced dimensionality (k) of the LP problem, obtained by applying a projection matrix to the original, higher-dimensional problem. The figure demonstrates that data-driven projection methods (PCA and SGA) generally achieve much higher objective ratios (closer to optimal) and significantly faster solution times than the baseline random projection method (ColRand), although there is some variation across different datasets.

read the caption

Figure 1: Plots of objective ratios (upper) and Gurobi's running times (lower, semi-log) for Full, ColRand, PCA, and SGA averaged over 100 test instances. The error band of ColRand indicates the standard deviation over 10 independent trials. The results of Full are shown for every k for reference, although it always solves n-dimensional LPs and hence is independent of k.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of four different methods for solving linear programming (LP) problems: Full, ColRand, PCA, and SGA. The top row shows the objective ratios (the objective value obtained by each method divided by the optimal objective value obtained by the Full method) for eight different datasets. The bottom row shows the running times of Gurobi (a commercial LP solver) for each method. The figure demonstrates that data-driven projection methods (PCA and SGA) can achieve significantly higher solution quality and faster solving times than random projection methods (ColRand), while still being comparable in performance to the Full method. The error bands for ColRand show the standard deviation across 10 independent trials, highlighting the variability inherent in random projection techniques.

read the caption

Figure 1: Plots of objective ratios (upper) and Gurobi's running times (lower, semi-log) for Full, ColRand, PCA, and SGA averaged over 100 test instances. The error band of ColRand indicates the standard deviation over 10 independent trials. The results of Full are shown for every k for reference, although it always solves n-dimensional LPs and hence is independent of k.

Full paper#