TL;DR#

Temporal action segmentation (TAS) faces challenges in efficiency due to long-form inputs and complex models. Existing methods often involve multiple stages and resource-intensive post-processing, hindering real-time applications. This necessitates the development of more efficient methods without compromising accuracy.

BaFormer addresses these issues with a novel single-stage approach centered around per-segment classification using Transformers. It employs instance queries for instance segmentation and a global query for boundary prediction, enabling a simple yet effective voting strategy during inference. This approach significantly reduces computational costs while achieving better or comparable accuracy to state-of-the-art methods on several benchmarks. The code’s public availability promotes reproducibility and further research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly relevant to researchers working on efficient temporal action segmentation. It presents a novel, single-stage approach that significantly reduces computational costs while maintaining high accuracy, addressing a major bottleneck in the field. The boundary-aware query voting method and use of Transformers open new avenues for developing efficient and effective solutions, impacting both real-time and resource-constrained applications. The public availability of the code further enhances its value to the community.

Visual Insights#

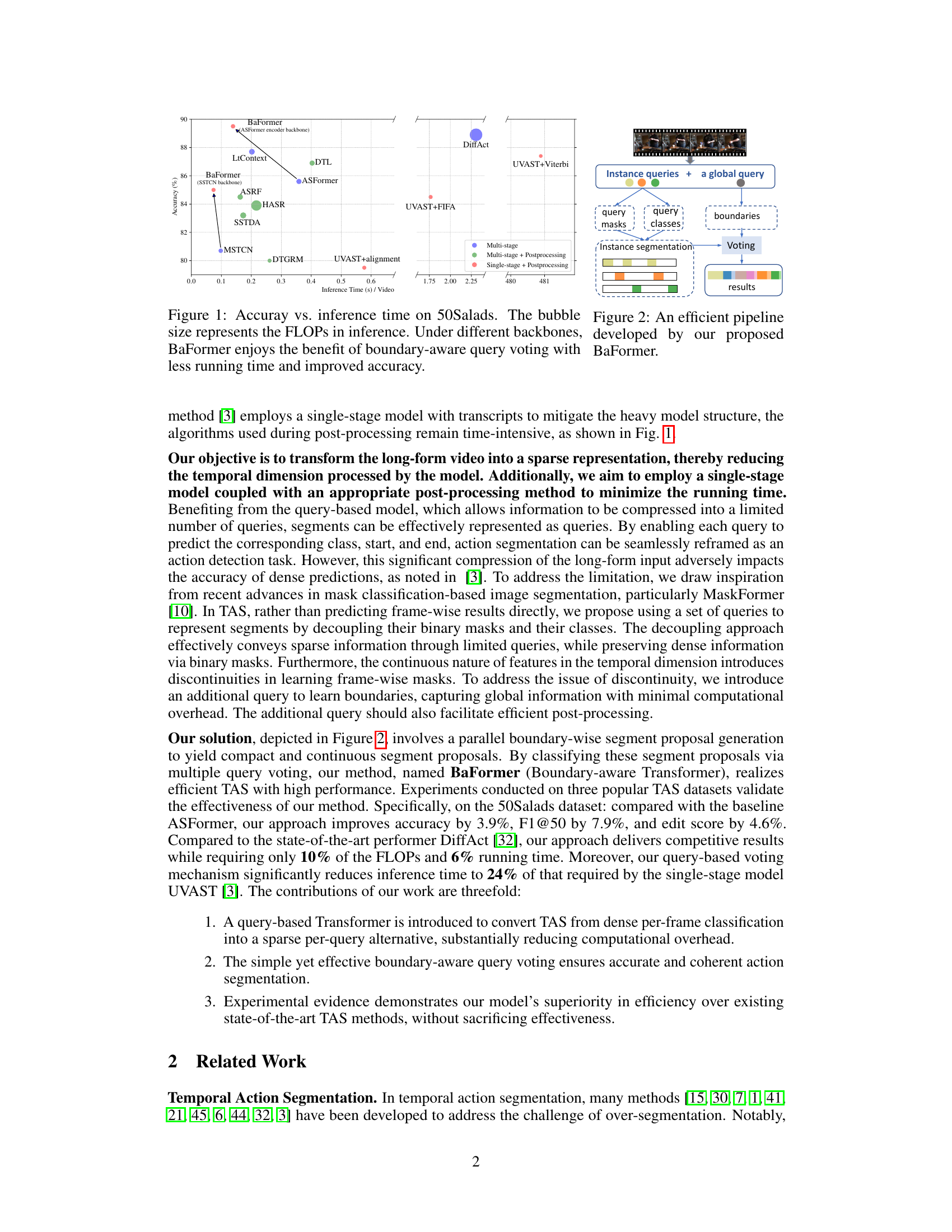

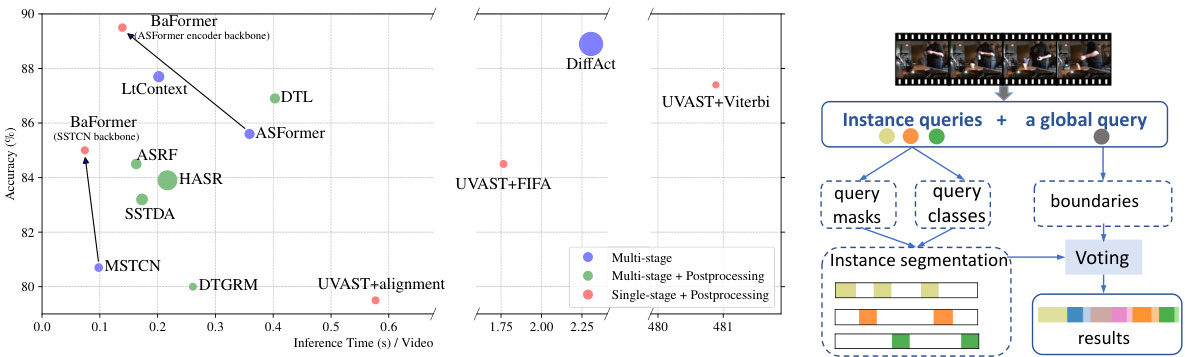

🔼 This figure compares the accuracy and inference time of different temporal action segmentation methods on the 50Salads dataset. The bubble size for each method visually represents its computational cost (FLOPs). BaFormer consistently demonstrates superior performance (higher accuracy) with significantly reduced inference time compared to other methods. It shows that using different backbones (ASFormer and SSTCN) for BaFormer, the boundary-aware query voting mechanism is effective and maintains performance advantages.

read the caption

Figure 1: Accuray vs. inference time on 50Salads. The bubble size represents the FLOPs in inference. Under different backbones, BaFormer enjoys the benefit of boundary-aware query voting with less running time and improved accuracy.

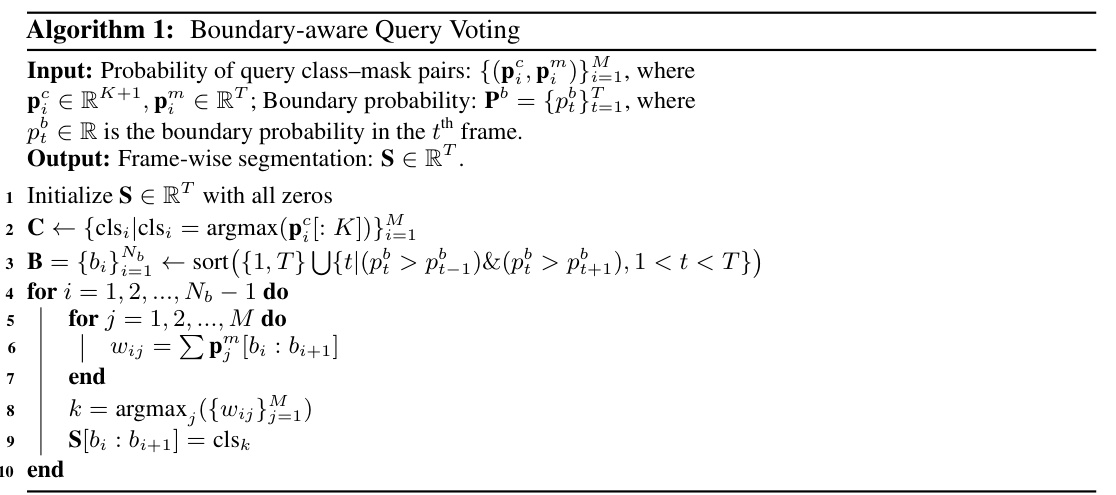

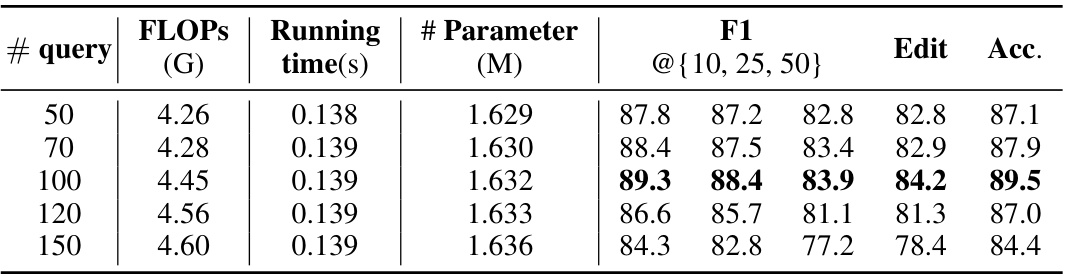

🔼 This table presents a comparison of three different matching strategies used in the BaFormer model for temporal action segmentation on the 50Salads dataset. The strategies are: Ordered Class Matching, Transcript Matching, and Instance Matching. For each strategy, the table shows the number of queries used, FLOPs (floating-point operations), inference time, number of parameters, and the performance metrics (F1@10, F1@25, F1@50, Edit score, and accuracy). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the instance matching strategy in achieving high accuracy with a relatively small number of queries compared to the other two strategies.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparative analysis of matching strategies on 50Salads. (#Q: number of queries.)

In-depth insights#

Boundary-Aware Query#

The concept of “Boundary-Aware Query” suggests a query mechanism in a model that is not only focused on identifying objects or segments but also explicitly considers their boundaries. This is a significant advance over traditional methods that may struggle with precise segmentation. The boundary information improves the accuracy of locating and defining the extent of each object, leading to more refined segmentations. This approach is particularly valuable in tasks such as temporal action segmentation where precise temporal boundaries between actions are crucial for accurate understanding. By incorporating boundary awareness into the query process, the model can better distinguish between closely related actions or events that share similar characteristics. This leads to more robust and accurate segmentations, even in challenging scenarios with ambiguous or noisy data. The effectiveness of boundary-aware queries likely relies on the design of the query mechanism, the model architecture, and the training process. Efficient and effective boundary prediction likely requires a sophisticated model that can capture the contextual information needed to accurately predict the boundaries.

Transformer Network#

Transformer networks, renowned for their ability to process sequential data effectively, are ideally suited for temporal action segmentation. Their inherent capacity for long-range dependencies allows the model to capture relationships between distant frames, crucial for accurately segmenting actions within long, untrimmed videos. The attention mechanism is a core component, enabling the model to focus on the most relevant parts of the input sequence at each step, improving efficiency and accuracy. The query-based approach, using instance queries for segment classification and a global query for boundary prediction, represents an innovative approach to segment proposal generation within the Transformer framework. This design significantly contributes to the efficiency of the method, making it particularly suitable for real-time or resource-constrained applications. The use of multiple queries also allows for a more fine-grained representation of the video data and enhances the model’s capacity to discriminate between different actions. However, challenges remain, including the potential for slow training convergence and a reliance on substantial data for optimal performance.

Efficient Single-Stage#

The concept of an “Efficient Single-Stage” approach to temporal action segmentation (TAS) is appealing because it directly addresses two major shortcomings of existing methods: high computational cost and the complexity of multi-stage pipelines. A single-stage model simplifies the architecture, reducing computational overhead and improving inference speed. This efficiency is crucial for real-time applications and resource-constrained environments. The efficiency gains are likely achieved through architectural innovations, possibly involving novel network designs or efficient processing techniques, such as reducing the number of parameters or streamlining computations. However, a key challenge is maintaining accuracy. The ability to achieve high accuracy in a single stage is a significant hurdle, as multi-stage methods often incorporate refinement steps to improve precision. A successful single-stage approach likely involves a highly effective representation of temporal data, perhaps leveraging advanced techniques in attention mechanisms or transformer networks to capture long-range dependencies more effectively. The trade-off between efficiency and accuracy needs to be carefully examined and justified. Overall, an efficient single-stage method for TAS represents a significant advancement if it can achieve comparable or superior accuracy to multi-stage methods while offering substantial improvements in efficiency.

Query Voting Mechanism#

The core of the proposed approach lies in its novel query voting mechanism, which cleverly addresses the challenges of efficient and accurate temporal action segmentation. Instead of relying on traditional frame-by-frame predictions, the system leverages instance queries to generate compact segment proposals. These queries, along with a global query for boundary prediction, enable sparse representation, substantially reducing computational overhead. The voting process itself is the key innovation, classifying segments by aggregating predictions from multiple instance queries associated with each segment. This approach elegantly avoids the computationally expensive and often inaccurate post-processing steps employed by prior methods, offering a more direct and efficient solution. The boundary-aware nature of this process further enhances its performance, ensuring the segmentation results are not only efficient but also coherent and well-defined. The simplicity and effectiveness of this mechanism are demonstrated by its superior accuracy and speed in comparison to state-of-the-art methods.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this efficient temporal action segmentation method could focus on several key areas. Improving robustness to noise and variations in video quality is crucial for real-world applications. Exploring alternative query mechanisms or architectures beyond transformers, such as graph neural networks, could offer further efficiency gains or improved accuracy. Investigating semi-supervised or unsupervised learning paradigms would reduce the reliance on large, annotated datasets. Furthermore, a more in-depth analysis of the boundary-aware query voting mechanism, including its theoretical underpinnings, could lead to enhancements and better understanding of its effectiveness. Finally, adapting the model for real-time applications, such as live video analysis or interactive systems, would expand its potential impact. Addressing these future research avenues would solidify the method’s position as a leading approach in temporal action segmentation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

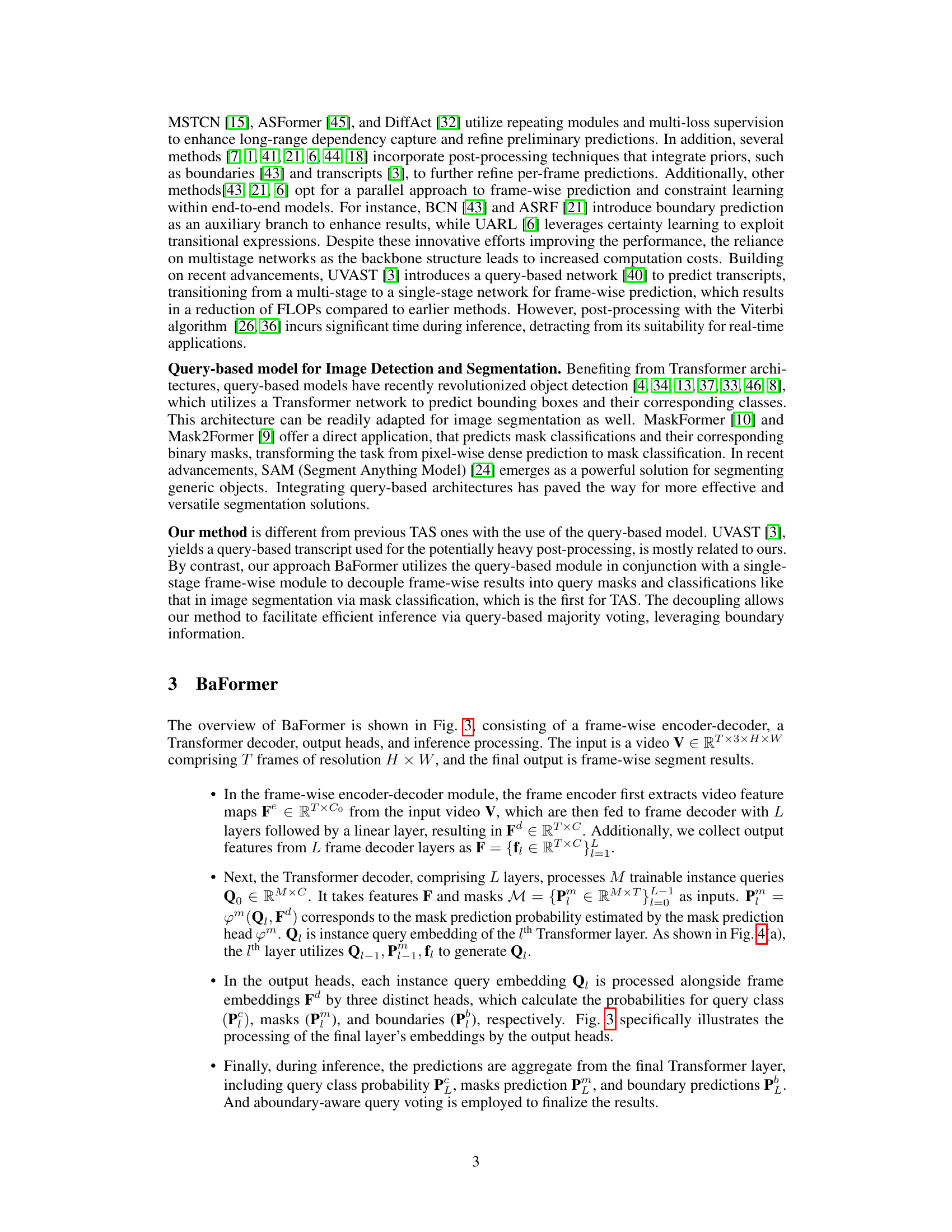

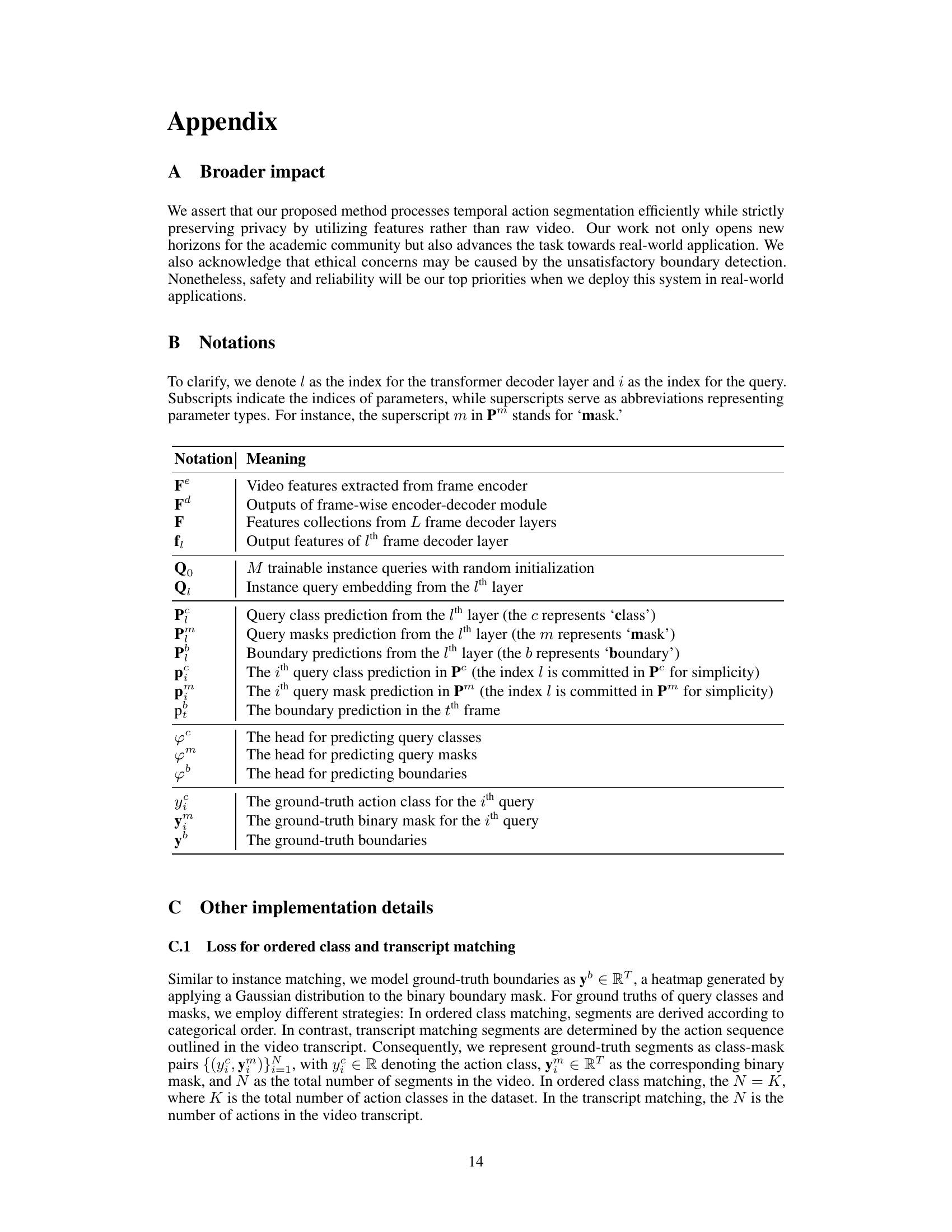

🔼 This figure shows the overall architecture of the BaFormer model. It starts with a frame-wise encoder-decoder which processes the video frames to extract features. These features, along with instance and global queries, are fed into a transformer decoder. The decoder then uses three output heads (classification, mask prediction, and boundary prediction) to generate predictions for each query. Finally, an inference step uses a voting mechanism to combine these predictions into the final segment results. The figure highlights the parallel processing of instance queries and a global query for boundary prediction.

read the caption

Figure 3: Overview of BaFormer architecture. It predicts query classes and masks, along with boundaries from output heads. Although each layer in the Transformer decoder holds three heads, we illustrate the three heads in the last layer for simplicity.

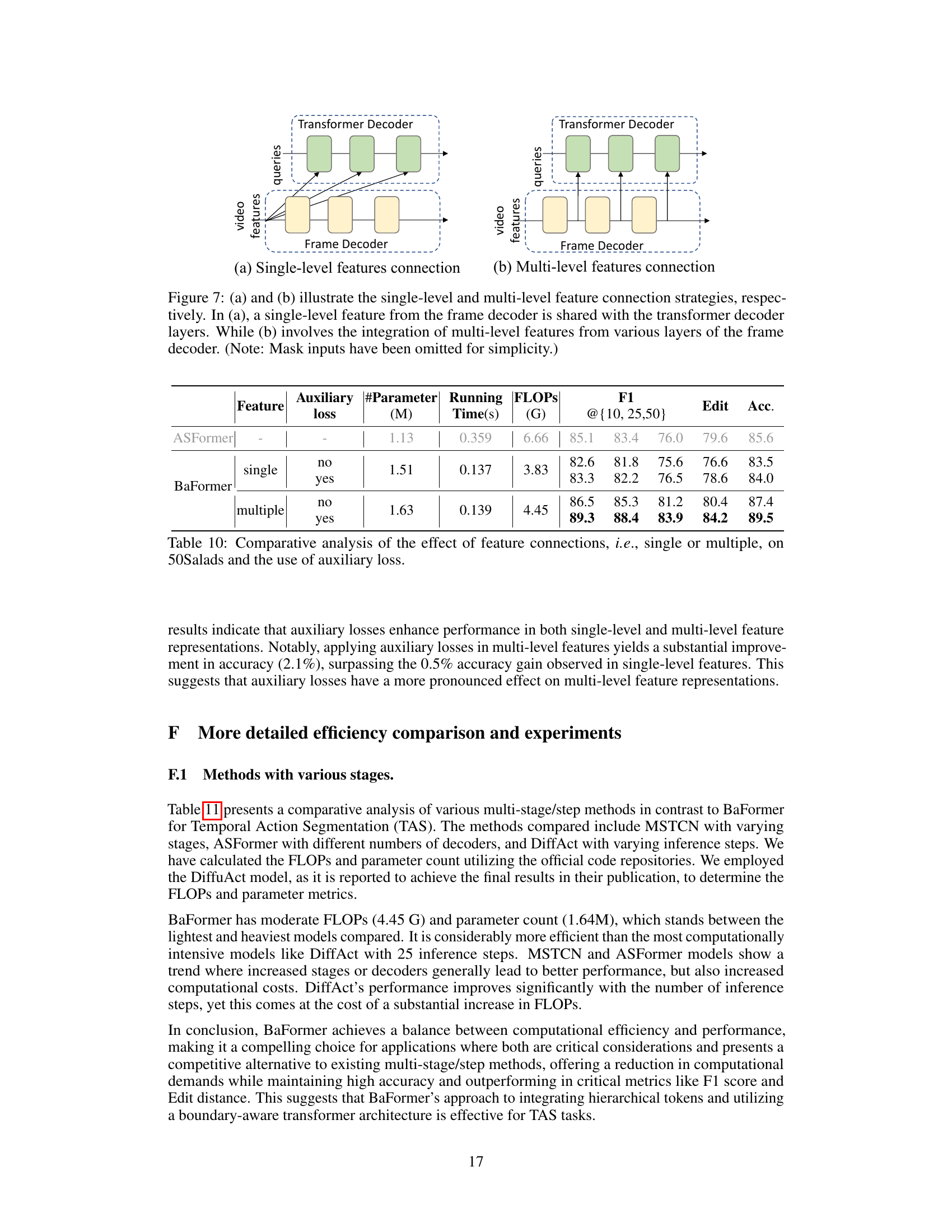

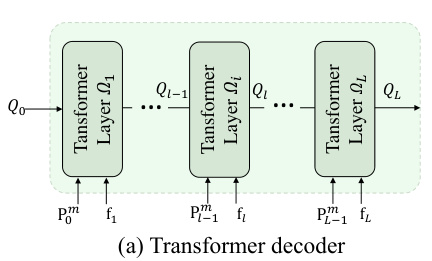

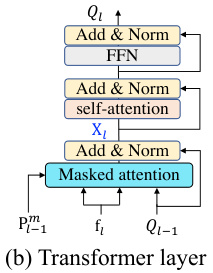

🔼 This figure shows the detailed architecture of the Transformer decoder used in BaFormer. (a) illustrates the overall structure of the decoder, which consists of L stacked Transformer layers. Each layer takes the previous layer’s output and current frame features as input and produces updated query embeddings. (b) zooms in on a single Transformer layer, showing its three sub-layers: masked attention, self-attention, and a feed-forward network. These layers process the information in parallel and use residual connections and normalization to improve the model’s performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: Details of Transformer decoder. (a) Transformer decoder stacks L Transformer layers. (b) Each Transformer layer consists of a masked attention, self-attention, and a feed-forward network with residual connections and normalization.

🔼 This figure provides a detailed illustration of the Transformer decoder used in the BaFormer architecture. Panel (a) shows the overall structure of the decoder, which consists of L stacked Transformer layers. Panel (b) zooms into a single Transformer layer, revealing its internal components: masked attention, self-attention, and a feed-forward network. Each component has residual connections and normalization for improved performance. This design is crucial for the model’s ability to process temporal data efficiently and generate sparse representations.

read the caption

Figure 4: Details of Transformer decoder. (a) Transformer decoder stacks L Transformer layers. (b) Each Transformer layer consists of a masked attention, self-attention, and a feed-forward network with residual connections and normalization.

🔼 This figure illustrates three different strategies for matching predicted query results to ground truth action segments. (a) Ordered Class Matching aligns queries sequentially to action classes. (b) Transcript Matching aligns queries to actions based on the video’s transcript order. (c) Instance Matching dynamically matches queries to action instances using the Hungarian algorithm, allowing for flexible alignment and handling of varying numbers of queries and actions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Different matching strategies. Given an example video including ordered action [a3, a5, a1] from a dataset with all action classes {a}i=1, (a) and (b) are fixed matching, while (c) is dynamic matching.

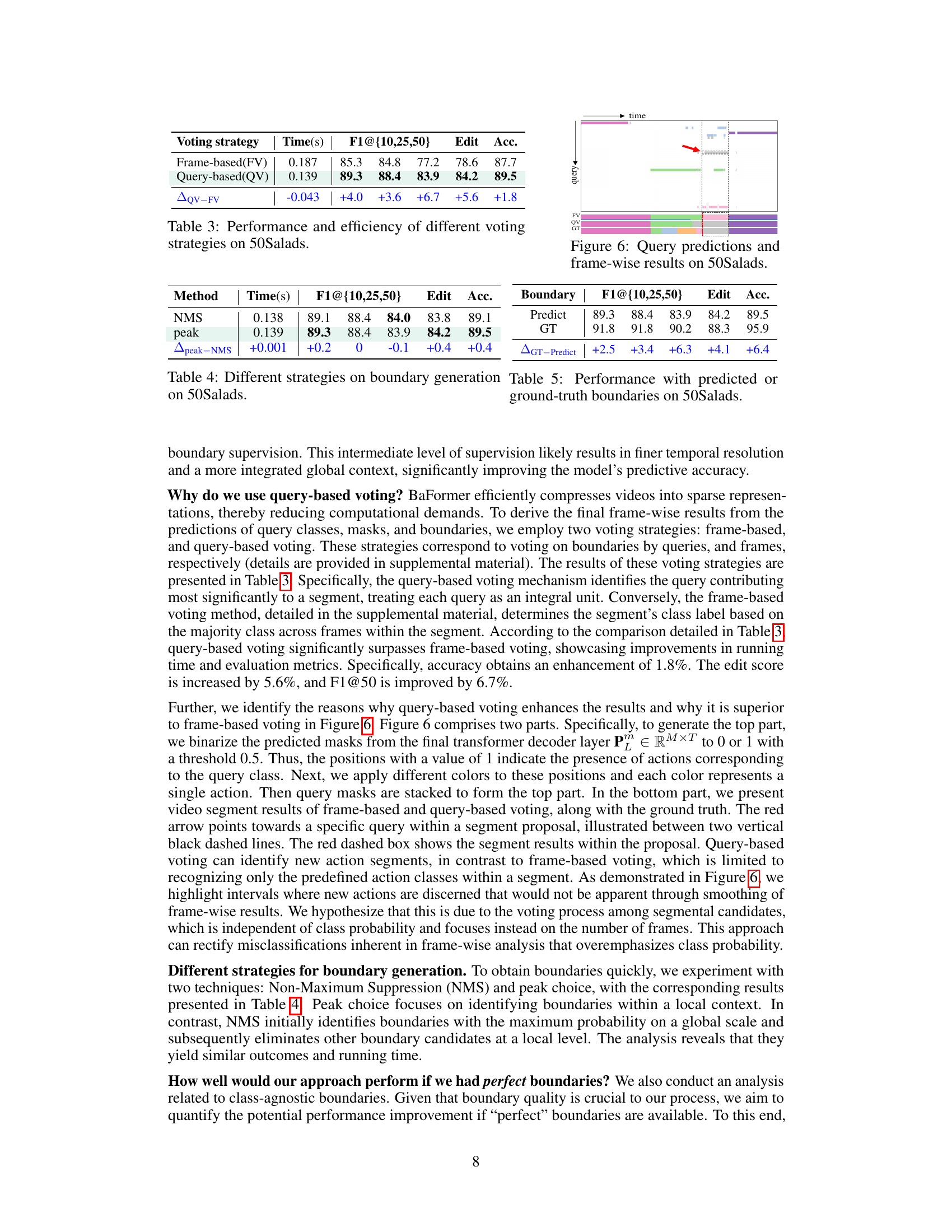

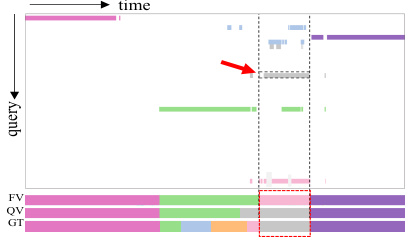

🔼 This figure visualizes the query predictions and frame-wise results obtained using the BaFormer model on the 50Salads dataset. The upper part shows the query predictions, where each color represents a different action class. The lower part compares the frame-wise results obtained using frame-based voting (FV), query-based voting (QV), and the ground truth (GT). The red arrow highlights a specific segment where the query-based voting method correctly identifies an action segment that is missed by the frame-based voting method.

read the caption

Figure 6: Query predictions and frame-wise results on 50Salads.

🔼 This figure compares two different ways of connecting the frame decoder and transformer decoder in the BaFormer architecture. (a) shows a single-level connection, where only one layer’s output from the frame decoder is used. (b) demonstrates a multi-level connection that uses outputs from multiple layers, enriching the information available to the transformer decoder. The image omits mask inputs for simplicity.

read the caption

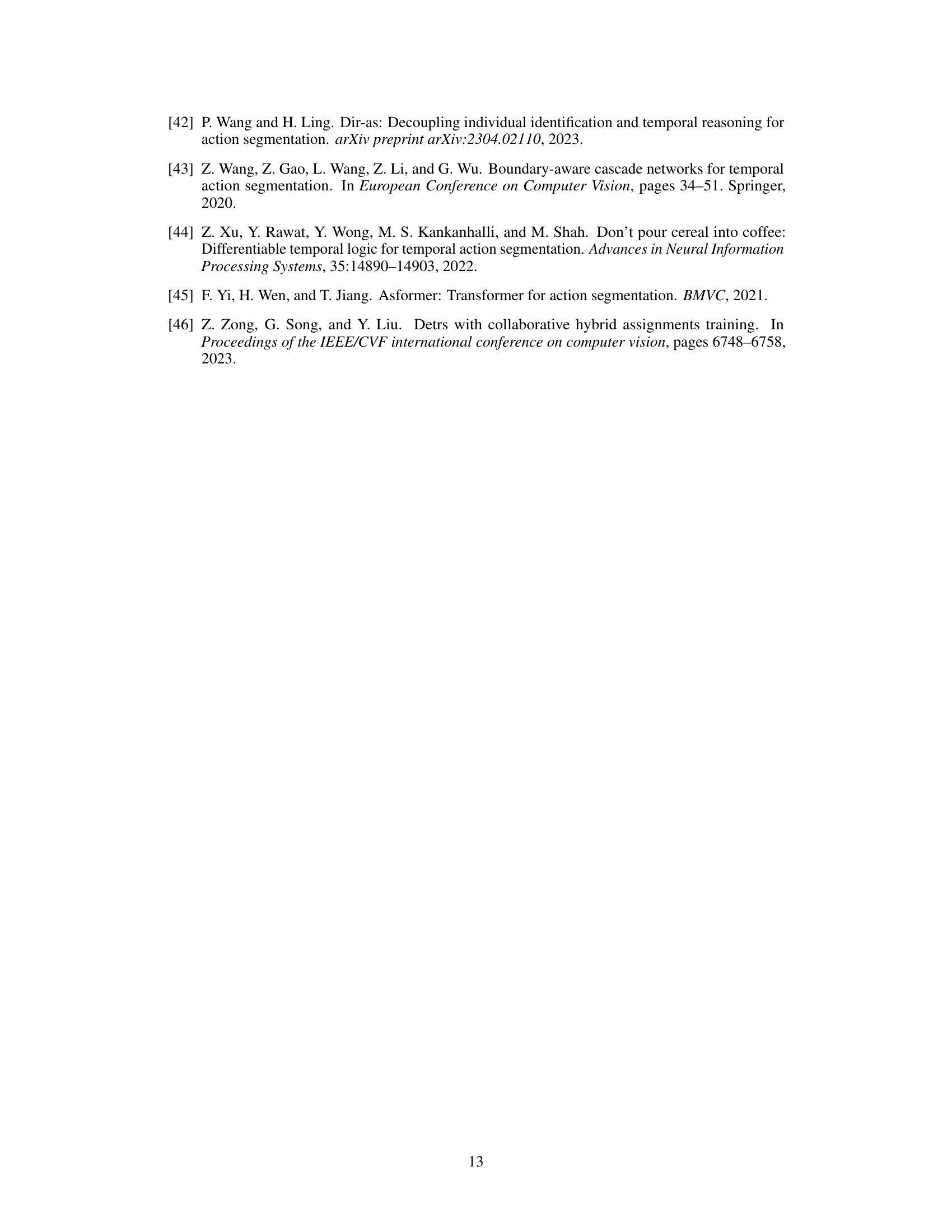

Figure 7: (a) and (b) illustrate the single-level and multi-level feature connection strategies, respectively. In (a), a single-level feature from the frame decoder is shared with the transformer decoder layers. While (b) involves the integration of multi-level features from various layers of the frame decoder. (Note: Mask inputs have been omitted for simplicity.)

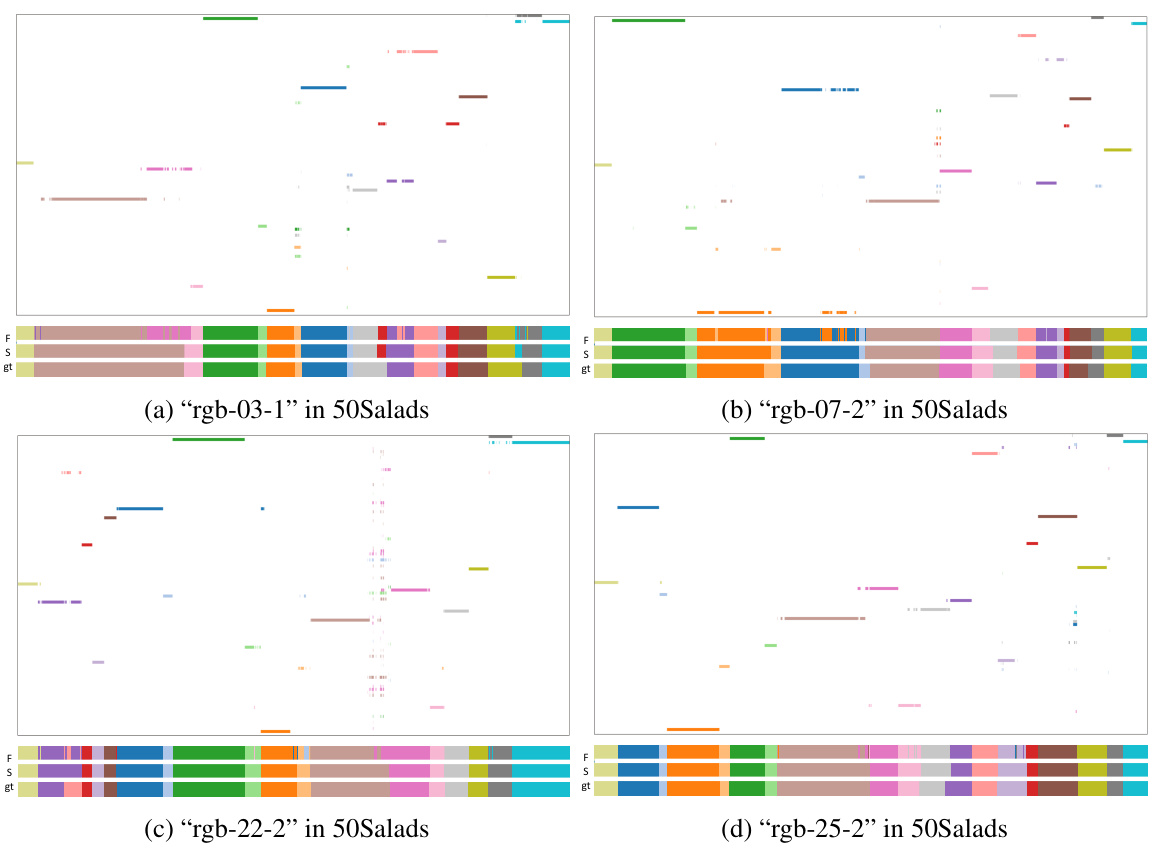

🔼 This figure visualizes instance segmentation results and compares them with frame-wise results obtained with and without boundary utilization. The results are shown for four different videos from the 50Salads dataset. Each video is shown in a separate subfigure. The top section of each subfigure shows the instance segmentation results, with different colors representing different action classes. The bottom section shows a comparison of frame-wise results: one without considering boundary information (F), one using boundary information from the proposed BaFormer model (S), and the ground truth (gt). The figure demonstrates that incorporating boundary information leads to significantly improved results, reducing over-segmentation and improving the accuracy of action segmentation.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visualization of the 50Salads dataset. Each subfigure presents a comparison of instance segmentation and frame-wise results. “F” indicates the absence of boundary utilization. “S” signifies its inclusion. 'gt' represents the ground truth.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a comparison of three different matching strategies used in the BaFormer model for temporal action segmentation on the 50Salads dataset. The strategies are Ordered Class Matching, Transcript Matching, and Instance Matching. The table shows the performance of each strategy in terms of FLOPs, inference time, number of parameters, and accuracy metrics (F1 score at different IoU thresholds and Edit score). The results demonstrate that the Instance Matching strategy, particularly with a higher number of queries (100), achieves the best performance across all metrics.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparative analysis of matching strategies on 50Salads. (#Q: number of queries.)

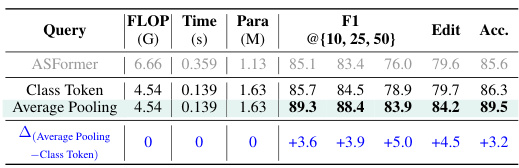

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different global query methods used in the BaFormer model on the 50Salads dataset. It shows the effectiveness of using an average pooling method versus a class token method for generating a global query to improve boundary prediction and overall performance. The metrics evaluated are FLOPs, inference time, model parameters, F1-score@ {10, 25, 50}, edit score, and accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance of different global queries on 50Salads.

🔼 This table compares two voting strategies: frame-based voting (FV) and query-based voting (QV) on the 50Salads dataset. It shows the inference time, F1 scores at different IoU thresholds (10, 25, 50), edit score, and accuracy for each method. The improvement achieved by query-based voting (QV) over frame-based voting (FV) is also presented, highlighting the efficiency gains and accuracy improvements provided by the query-based approach.

read the caption

Table 3: Performance and efficiency of different voting strategies on 50Salads.

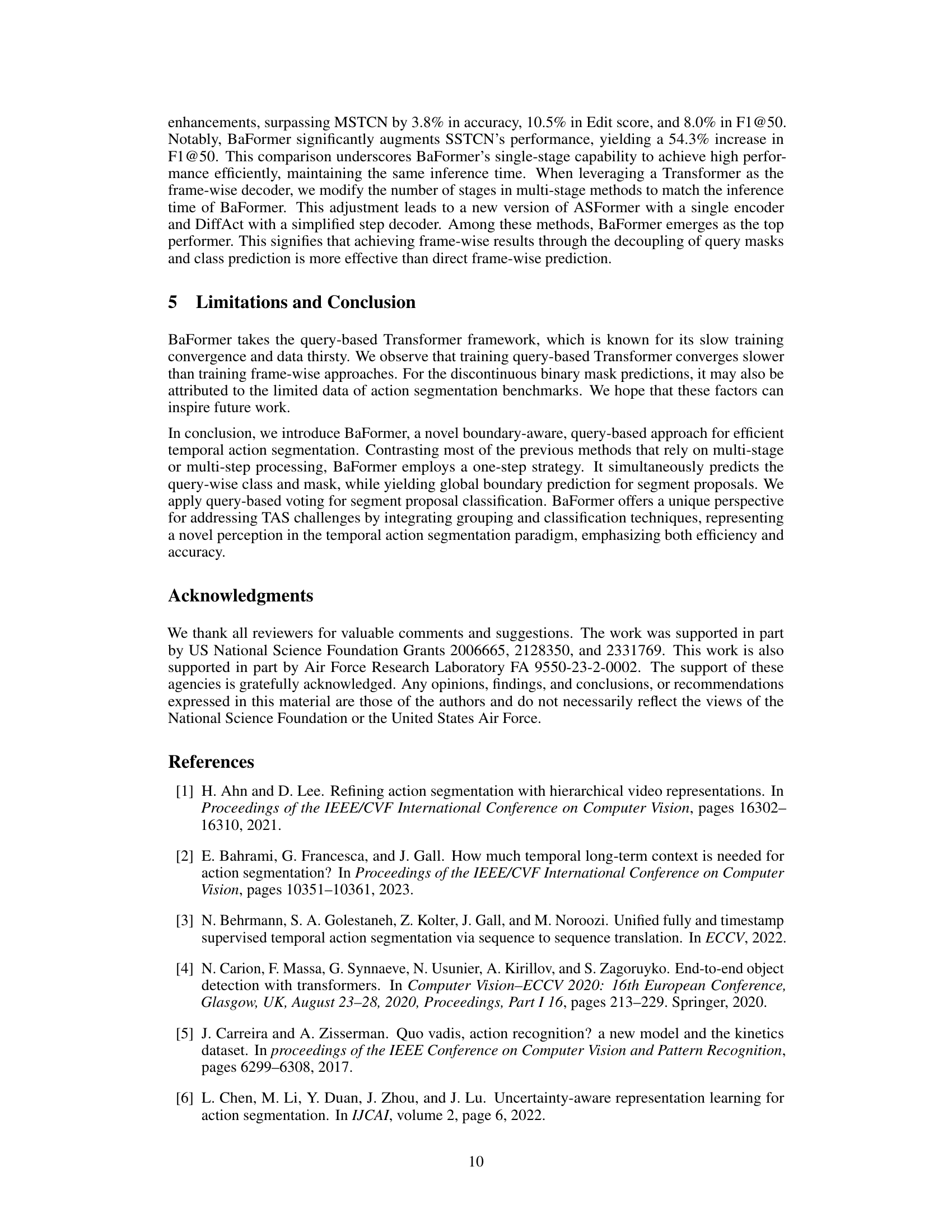

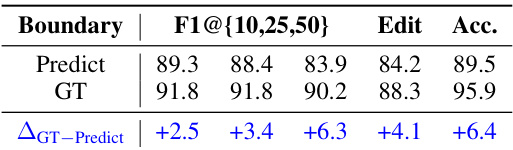

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the model’s performance using predicted boundaries versus ground truth boundaries on the 50Salads dataset. The performance metrics shown are F1 scores at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds (10%, 25%, 50%), Edit score, and overall Accuracy. The difference between using predicted and ground truth boundaries is also calculated, highlighting the impact of accurate boundary detection on the model’s performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Performance with predicted or ground-truth boundaries on 50Salads.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different boundary generation strategies on the 50Salads dataset. The strategies compared are Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), peak choice, and using the ground truth boundaries. The metrics used to evaluate performance are F1 scores at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds (10%, 25%, 50%), edit score, and accuracy. The results show that using ground truth boundaries yields the best performance, but peak choice and NMS achieve comparable results, with peak choice slightly better than NMS.

read the caption

Table 4: Different strategies on boundary generation on 50Salads.

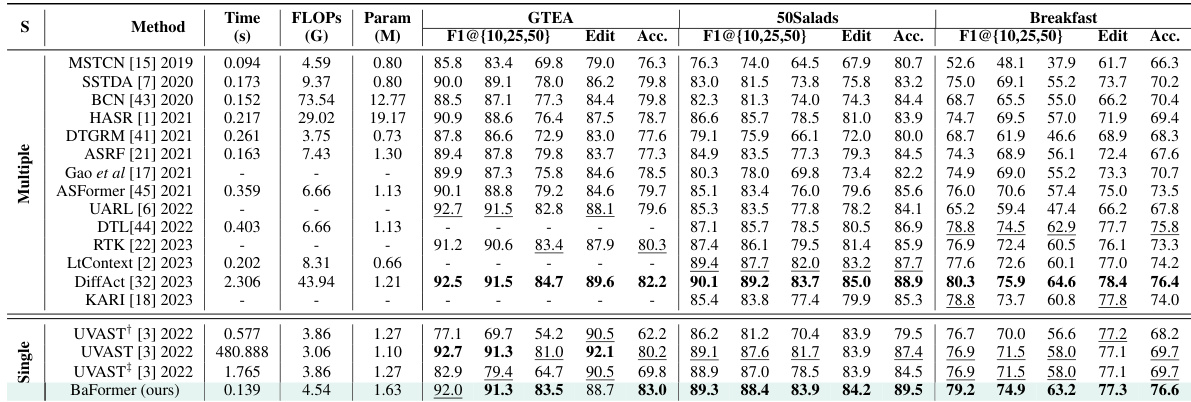

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive comparison of BaFormer’s performance against state-of-the-art methods on three benchmark datasets: GTEA, 50Salads, and Breakfast. It compares various metrics including running time (in seconds), FLOPs (in billions), number of parameters (in millions), and performance metrics (F1 scores at different IoU thresholds and edit scores) for each dataset. The table highlights BaFormer’s efficiency and competitive accuracy compared to other methods.

read the caption

Table 6: Performance on GTEA, 50Salads, and Breakfast datasets. In terms of running time, BaFormer outperforms all methods except MSTCN. As for accuracy, BaFormer achieves comparable or better results. UVAST†, UVAST, and UVAST‡ represent UVAST with alignment decoder, Viterbi, and FIFA. All FLOPs and running time are evaluated on 50Salads using the official codes in a consistent environment. We omit the running time and FLOPs on GTEA and Breakfast for simplicity as they are proportional to video length.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods with similar running times on the 50Salads dataset. It contrasts methods using CNN-based and Transformer-based frame decoders. To ensure fair comparison of running times, DiffAct uses only a single decoder step and ASFormer uses only its encoder. The table highlights the trade-offs between computational cost and accuracy for different architectural choices.

read the caption

Table 7: Performance of methods with similar running time, employing the CNN or Transformer based frame decoder on the 50Salads dataset. To achieve comparable running time, DiffAct (1 step) is adapted with an encoder and a single-step decoder, and ASFormer with an encoder only is included.

🔼 This table compares three different matching strategies used in the BaFormer model for temporal action segmentation: Ordered Class Matching, Transcript Matching, and Instance Matching. For each strategy, it shows the number of queries used, the FLOPs (floating point operations), inference time, number of model parameters, and the evaluation metrics (F1 scores at different IoU thresholds (10%, 25%, 50%), Edit Score, and Accuracy). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of Instance Matching compared to the other two strategies.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparative analysis of matching strategies on 50Salads. (#Q: number of queries.)

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the number of transformer decoder layers used in the BaFormer model. It shows the FLOPs (floating point operations), running time, number of parameters, and the performance metrics (F1 score @{10, 25, 50}, Edit score, and Accuracy) for different numbers of layers (3, 5, 8, and 10) on the 50Salads dataset. The results indicate an optimal number of layers for balancing performance and computational cost.

read the caption

Table 8: Results of different numbers of Transformer decoder layers on 50Salads.

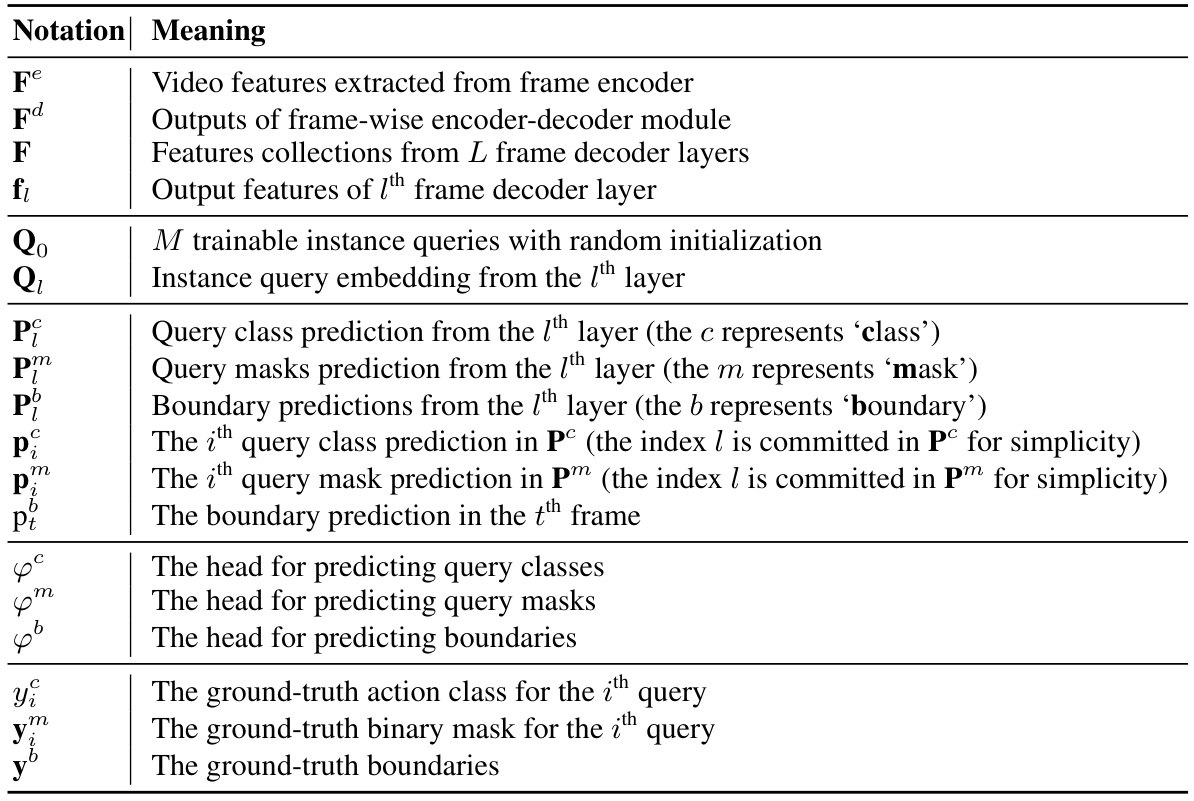

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the 50Salads dataset, investigating the impact of varying the number of queries on model performance. It shows that increasing the number of queries from 50 to 100 improves the model’s performance across all metrics (F1@ {10,25,50}, Edit score, and Accuracy), but further increasing the number of queries beyond 100 leads to diminishing returns, suggesting that there is an optimal range where the model’s performance is maximized. The table includes FLOPs, running time, and the number of parameters for different query counts.

read the caption

Table 9: Influence of query quantity on 50Salads.

🔼 This table presents a comparative analysis of different feature connection strategies (single vs. multiple) and the impact of using auxiliary losses during training on the 50Salads dataset. It shows the performance metrics (F1 score @ {10, 25, 50}, Edit score, and Accuracy) for different combinations of feature connections and auxiliary loss usage, allowing for assessment of their relative impact on the model’s performance. The results suggest that incorporating multiple features and incorporating auxiliary loss boosts accuracy and F1 scores.

read the caption

Table 10: Comparative analysis of the effect of feature connections, i.e., single or multiple, on 50Salads and the use of auxiliary loss.

🔼 This table compares the performance of several multi-stage and single-stage methods for temporal action segmentation on the 50Salads dataset. It shows the number of stages/steps used in each method, the FLOPs (floating-point operations), running time, number of parameters, and the performance metrics (F1 score at different IoU thresholds, edit score, and accuracy). The table highlights BaFormer’s efficiency and competitive performance compared to other state-of-the-art methods.

read the caption

Table 11: Comparative overview of multi-stage/step methods versus BaFormer on 50Salads. Here, 'MSTCNn' and 'ASFormern' denotes a model with n processing stages, while 'DiffActn' signifies a model with 'n' decoder steps.

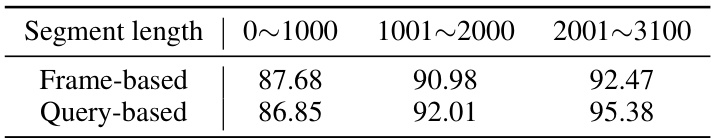

🔼 This table shows the accuracy of frame-based and query-based voting methods on different lengths of action segments from the 50Salads dataset. It compares the performance of the two methods across three segment length categories (0-1000 frames, 1001-2000 frames, and 2001-3100 frames). The results indicate that while frame-based methods perform slightly better on shorter segments, query-based methods demonstrate higher accuracy on longer segments. This highlights the difference in how each method processes the information.

read the caption

Table 12: Accuracy for action segments of different lengths, comparing frame-based and query-based methods on the 50Salads dataset.

Full paper#