↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Estimating mutual information (MI), a key concept in information theory, is challenging, especially for high-dimensional data. Traditional methods struggle with accuracy and computational cost in such settings, limiting their applicability in areas like deep neural network analysis and explainable AI. This makes developing accurate and efficient MI estimation techniques highly important for researchers across multiple fields.

This research proposes a new MI estimation method that uses normalizing flows to transform data into a simpler distribution. This transformation preserves MI, making it easier to calculate accurately. The researchers provide theoretical guarantees and error bounds to support their approach’s accuracy and consistency. Experiments using high-dimensional datasets demonstrate that their method outperforms existing MI estimators in terms of both accuracy and efficiency. This opens up new possibilities for applying MI estimation in diverse areas, including analyzing and improving deep learning models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with high-dimensional data and neural networks. It offers novel and efficient methods for estimating mutual information, a critical metric in many machine learning applications. The proposed approach is computationally efficient and yields accurate results, addressing a significant limitation of current techniques. Furthermore, its theoretical guarantees and error bounds provide valuable insights for future research and development. This work opens up new avenues for exploring information-theoretic properties of deep learning models and its application in explainable AI.

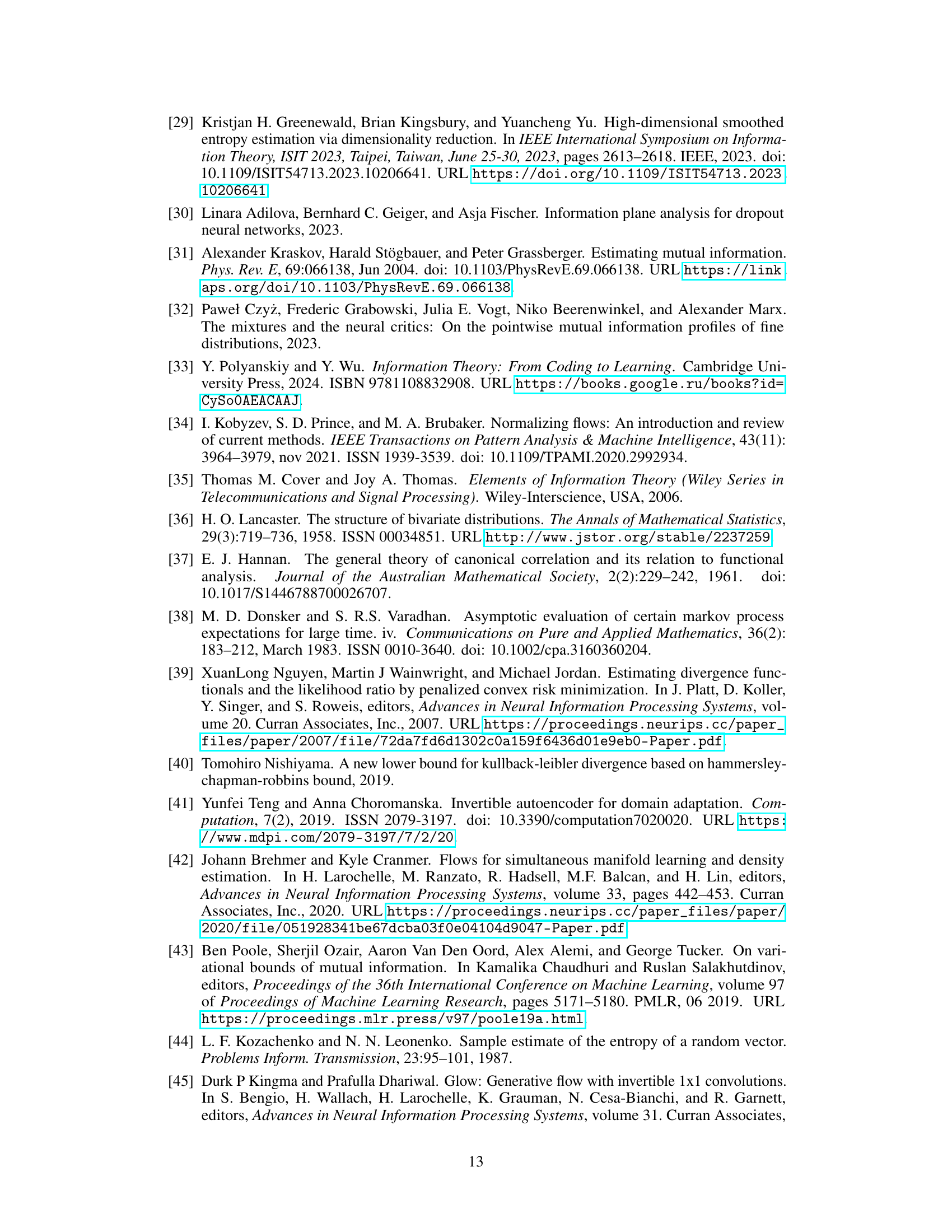

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the core idea of the proposed method for mutual information (MI) estimation using normalizing flows. The method involves transforming a pair of random vectors (X, Y) representing the original data into a latent space using learnable diffeomorphisms (fx and fy). The transformation is designed to map the original data distribution into a target distribution (ξ, η) where MI is easier to compute. The key is that the diffeomorphisms preserve the MI, so the estimated MI in the latent space accurately reflects the MI in the original space. The figure shows two variants: a general case and a specific case with a Gaussian base distribution.

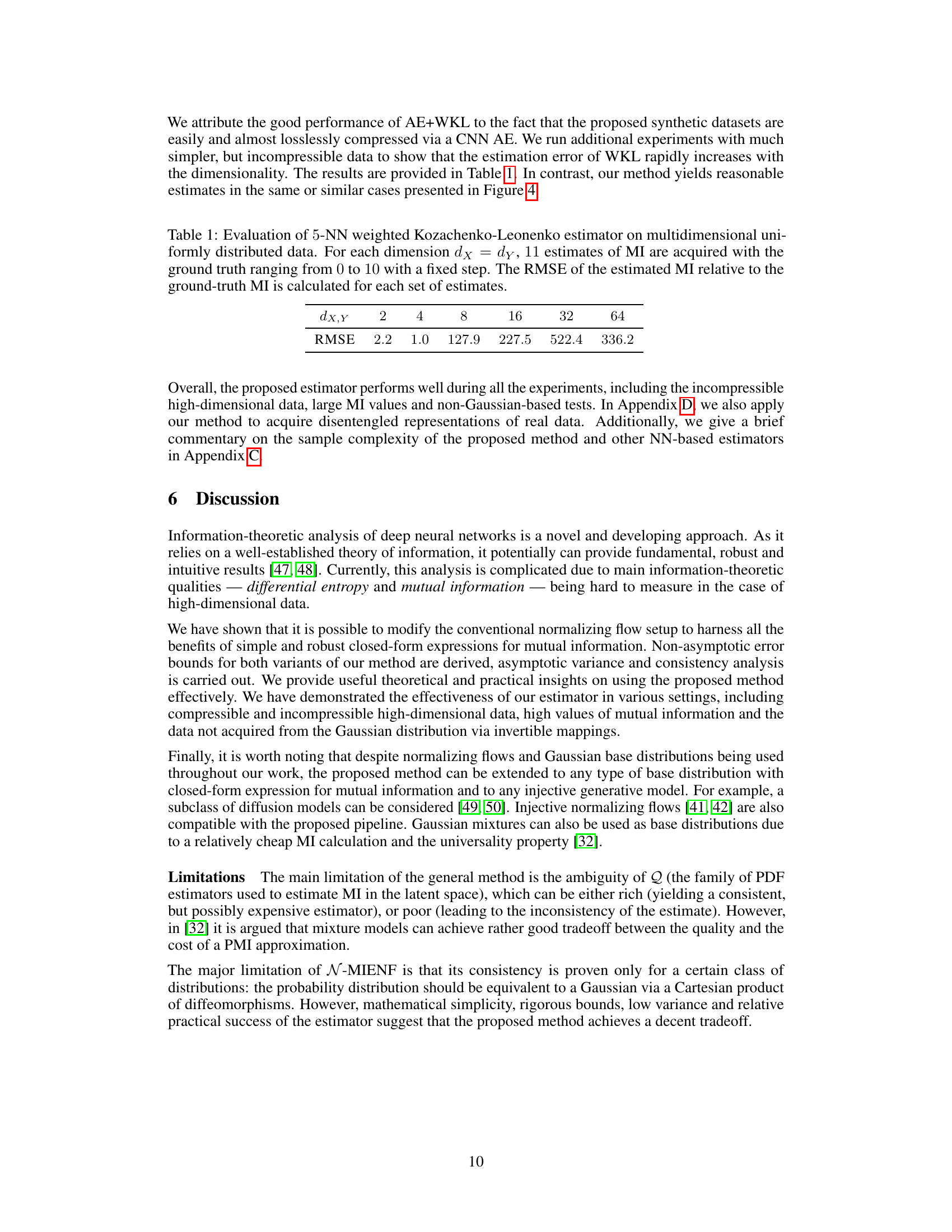

This table presents the results of evaluating the 5-NN weighted Kozachenko-Leonenko MI estimator on uniformly distributed multidimensional data. For various dimensions (dx = dy), 11 MI estimates were generated, comparing estimates against ground truth values ranging from 0 to 10. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is shown for each dimension, indicating the accuracy of the estimator.

In-depth insights#

Normalizing Flows for MI#

Normalizing flows offer a powerful technique for estimating mutual information (MI), a crucial measure in many machine learning applications. By transforming complex, high-dimensional data distributions into simpler, tractable ones (often Gaussian), normalizing flows enable more accurate and efficient MI estimation. This approach cleverly sidesteps the difficulties associated with directly estimating MI in high-dimensional spaces, where traditional methods often struggle. The core idea is that MI is invariant under invertible transformations, a property that normalizing flows inherently possess. This allows researchers to estimate MI in the transformed space, where calculation is easier, and then map this estimate back to the original space. However, the choice of the target distribution and the complexity of the flow model itself introduce practical challenges and potential limitations. The accuracy of the MI estimation hinges on how well the flow model can approximate the true data distribution, and the computational cost can increase significantly with data dimensionality and flow complexity. Further research is needed to address these issues and refine the methods for selecting appropriate flows and target distributions, ultimately improving the reliability and efficiency of MI estimation.

Gaussian MI Estimation#

Gaussian MI estimation leverages the properties of Gaussian distributions to simplify mutual information (MI) calculation. Assuming Gaussianity allows for the use of closed-form expressions for MI, bypassing the need for computationally intensive numerical approximations. This is a significant advantage, especially in high-dimensional settings where traditional MI estimation methods struggle. However, the Gaussian assumption is a major limitation, as real-world data rarely follows a perfect Gaussian distribution. The accuracy of the MI estimate hinges heavily on how well the data approximates a Gaussian, potentially leading to biased results if the data deviates significantly. Therefore, while computationally efficient, methods relying on Gaussian MI estimation compromise accuracy for speed. Techniques like normalizing flows are often combined with Gaussian MI estimation to transform non-Gaussian data into a closer approximation of Gaussianity before applying the simplified formulas. This approach offers a balance between computational efficiency and accuracy but still retains limitations due to the initial transformation step’s unavoidable influence on the final MI estimate.

High-Dimensional MI#

Estimating mutual information (MI) in high dimensions presents a significant challenge in machine learning and information theory. High-dimensional data often suffers from the curse of dimensionality, making it difficult to accurately estimate probability densities, a crucial step in MI calculation. Traditional methods struggle with computational complexity and statistical inefficiency in high-dimensional spaces. This paper tackles this challenge by leveraging normalizing flows to transform high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space where MI estimation is more tractable. The key idea is to use learnable transformations to simplify the joint distribution without losing information, making the MI calculation computationally cheaper and statistically more robust. The authors introduce MI estimators based on these flows and provide theoretical guarantees and empirical evidence of their effectiveness. The choice of a target distribution in the transformed space introduces a tradeoff between computational cost and estimation accuracy. While the Gaussian distribution offers analytical tractability, more flexible approximations are needed for high-dimensional, non-Gaussian data.

Asymptotic Error Bounds#

Analyzing a research paper’s section on “Asymptotic Error Bounds” requires a deep dive into the statistical properties of the proposed method. The focus should be on understanding how the error in the estimations behaves as the sample size grows infinitely large. Key aspects to consider are the convergence rate—how quickly the error decreases—and whether the estimator is consistent—does it converge to the true value? A rigorous analysis necessitates examining the assumptions made, such as the independence and identical distribution (i.i.d.) of the data, and evaluating the robustness of the bounds under deviations from these assumptions. The presence of explicit bounds provides valuable information about the estimation uncertainty, whereas the absence of such bounds would mean the analysis is less conclusive. Discussion of the bound’s tightness is also crucial, as it indicates the practical value of the result. Loose bounds might indicate the need for further refinements or improvements to the method.

MI Estimator Evaluation#

The section on “MI Estimator Evaluation” is crucial for validating the proposed mutual information (MI) estimation method. A robust evaluation requires comparing against established MI estimators using diverse, high-dimensional datasets. Synthetic datasets with known ground truth MI values are essential, allowing for direct assessment of accuracy and bias. The choice of datasets is vital; using only easily compressible data would favor methods that leverage compression, leading to skewed results. Including datasets with both compressible and incompressible structures is critical for a comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, comparing against estimators with different underlying approaches (e.g., neural network-based, k-NN based) provides a broader perspective on the method’s strengths and limitations. Error bars and confidence intervals are necessary to provide statistical significance to the results. Finally, discussing any limitations of the chosen estimators, as well as any potential reasons for unexpected results, enhances the overall credibility and thoroughness of the evaluation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

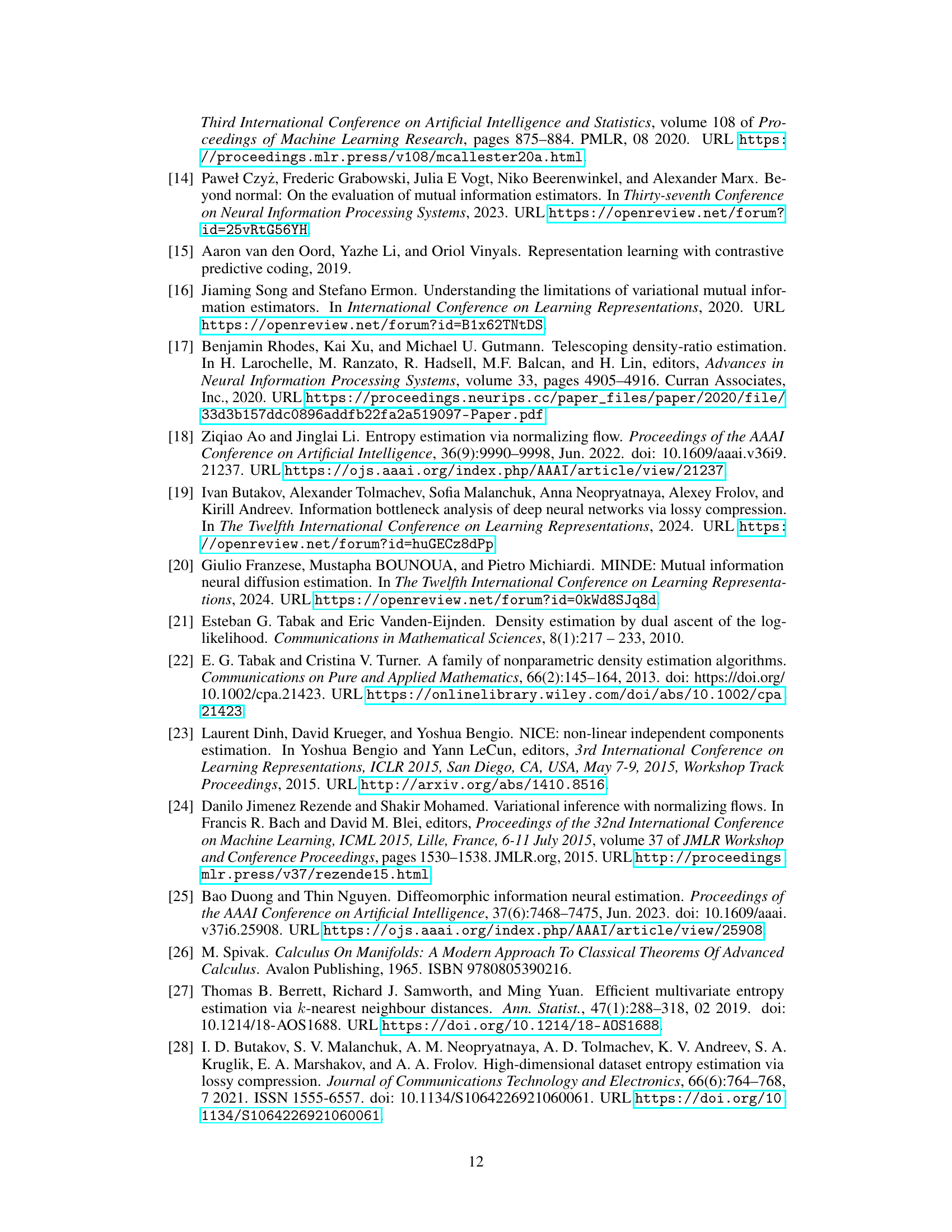

The figure illustrates the core idea of the proposed method for mutual information estimation. It shows two random vectors, X and Y, being transformed via learnable diffeomorphisms (fx and fy) into latent representations ξ and η, respectively. The transformation is designed to map the original data distribution into a target distribution where MI is easier to compute (tractable). The key is that diffeomorphisms preserve mutual information, so I(X;Y) = I(ξ;η). The figure displays this process graphically showing the original distributions, the diffeomorphic transformations, the resulting Gaussian-like target distributions, and the final joint distribution in the latent space.

This figure shows examples of the synthetic images used in the paper’s experiments. The left panel displays 2D Gaussian distributions that are transformed into high-dimensional images. The right panel shows rectangles of varying sizes and orientations, also transformed into high-dimensional images. The caption highlights that, although the images are high-dimensional, they possess a latent structure similar to that found in real-world datasets. This similarity is important because it means the results from these synthetic experiments can be generalized to real-world scenarios.

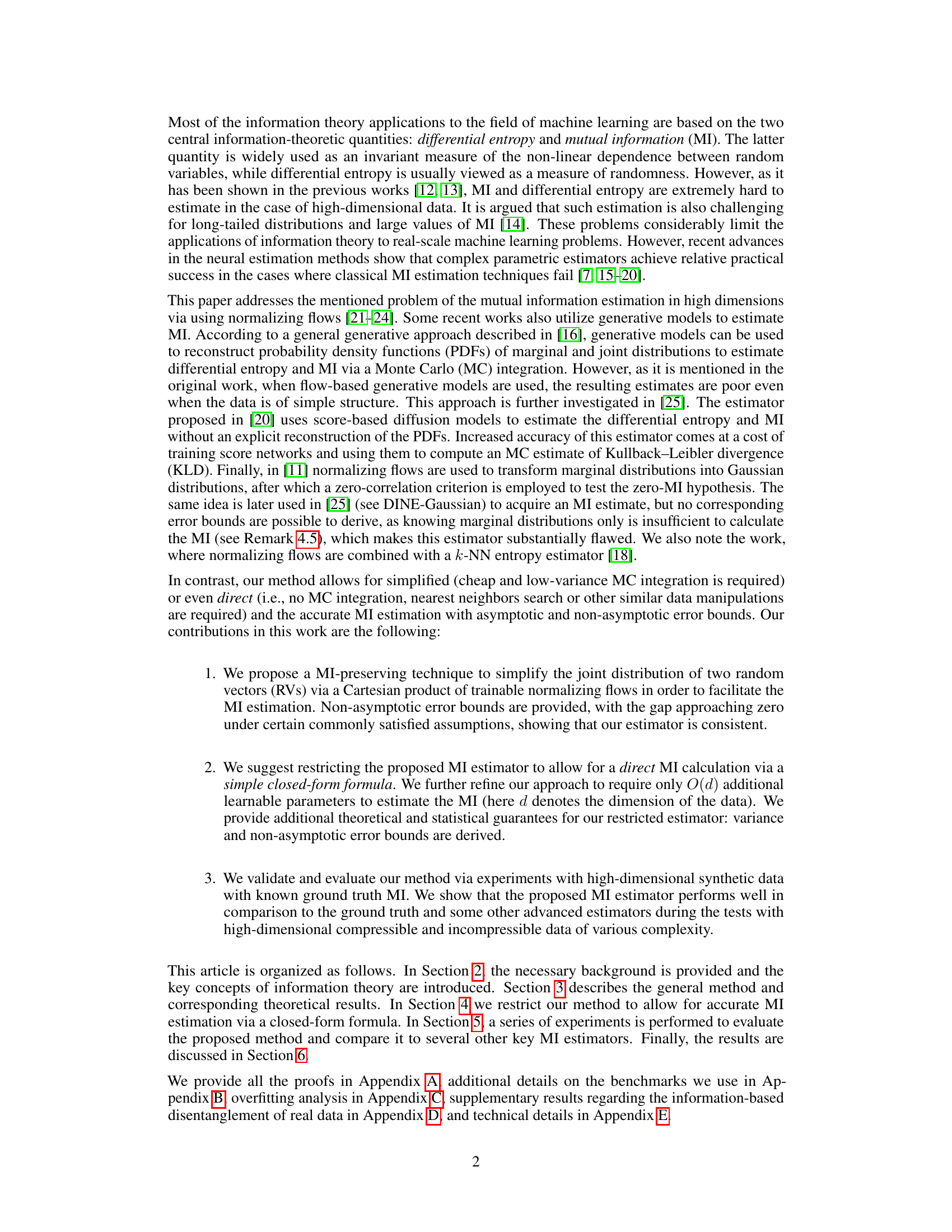

This figure compares the performance of several mutual information (MI) estimators, including the proposed MIENF method, against the ground truth. The plot shows the estimated MI (Î(X;Y)) versus the true MI (I(X;Y)) for four different datasets: 16x16 and 32x32 images generated from Gaussian and rectangular distributions. 99.9% asymptotic confidence intervals (CIs) are displayed to illustrate the uncertainty in the estimates. The results highlight the accuracy and robustness of MIENF across various datasets and dimensions.

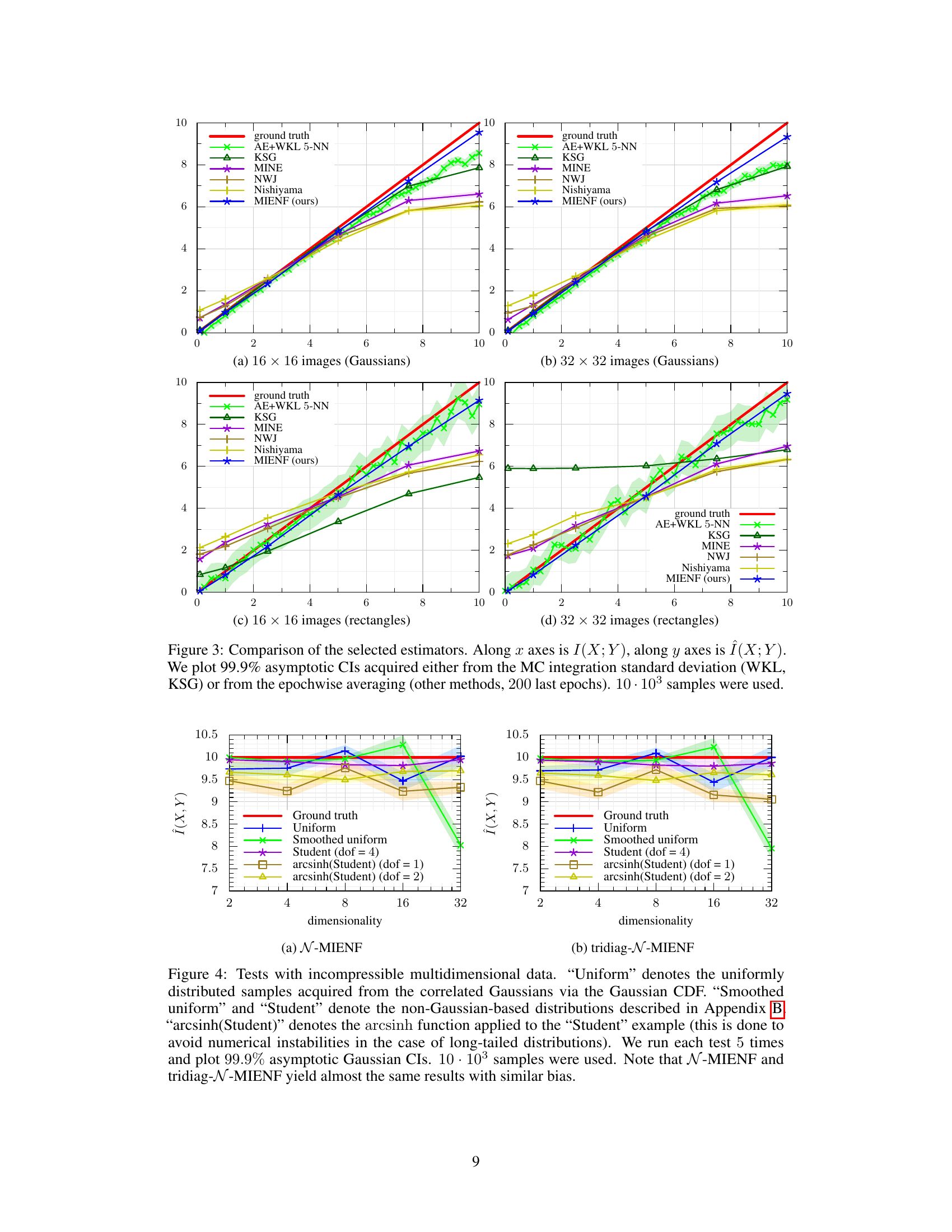

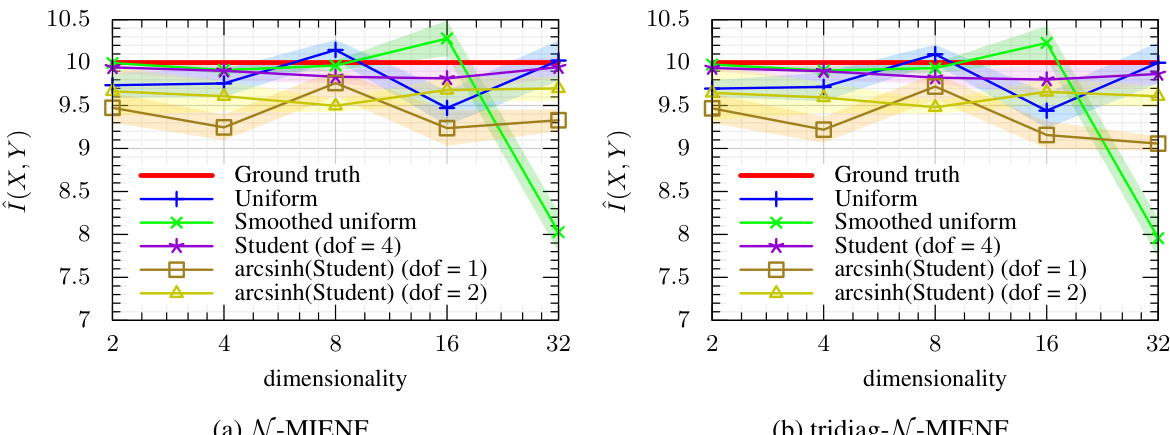

The figure shows the comparison of different MI estimation methods on high-dimensional synthetic datasets with non-Gaussian distributions. The results demonstrate the robustness and accuracy of the proposed MI estimators (N-MIENF and tridiag-N-MIENF) compared to other methods, especially in high-dimensional settings with long-tailed distributions.

This figure compares the performance of several mutual information (MI) estimators, including the proposed MIENF method, against ground truth values. The x-axis represents the true MI between two random variables (I(X;Y)), while the y-axis shows the estimated MI (Î(X;Y)) from each method. The plots show the results for Gaussian and rectangular image datasets of different sizes (16x16 and 32x32 pixels). The 99.9% asymptotic confidence intervals (CIs) illustrate the uncertainty in each estimate. The CIs for the methods based on Monte Carlo (MC) integration are calculated from the standard deviation of the MC estimate, whereas for other methods the CI is calculated by averaging over the last 200 epochs of training. A total of 10,000 samples were used for each dataset.

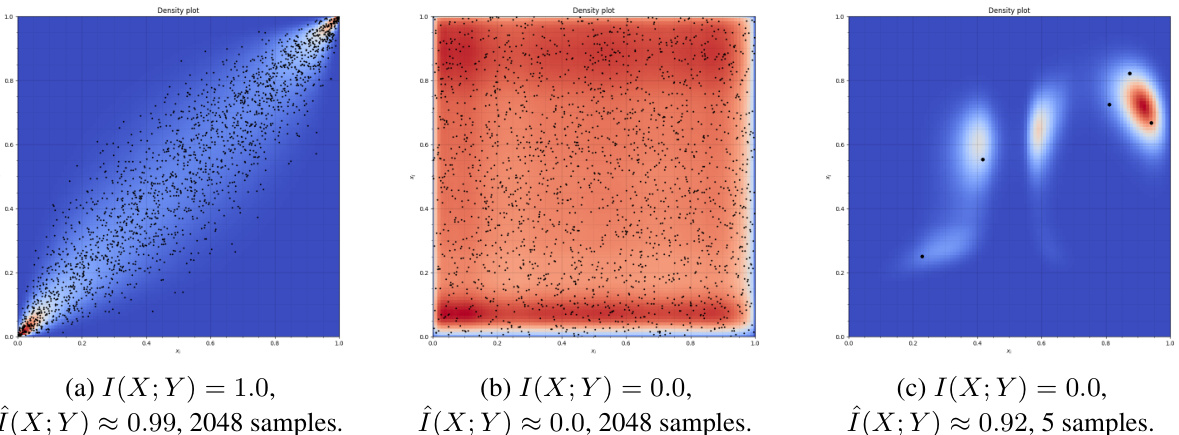

This figure shows the pointwise mutual information (PMI) plots for the Mutual Information Neural Estimator (MINE) using a correlated uniform distribution with varying ground truth mutual information (MI) and sampling sizes. The left plot shows a high MI and sufficient sampling, resulting in a reasonable approximation. The middle plot shows low MI and sufficient sampling, also resulting in a good approximation. The right plot, however, demonstrates the effects of insufficient sampling (only 5 samples). Here, MINE overfits to the data and incorrectly estimates a high MI even though the true MI is zero, illustrating the issue of overfitting with small sample sizes in this method.

This figure shows the probability density functions generated by the tridiag-N-MIENF model for three different scenarios: high MI, zero MI with sufficient data, and zero MI with insufficient data. The plots show how the model’s performance is affected by the amount of training data, highlighting the risk of overfitting with limited data.

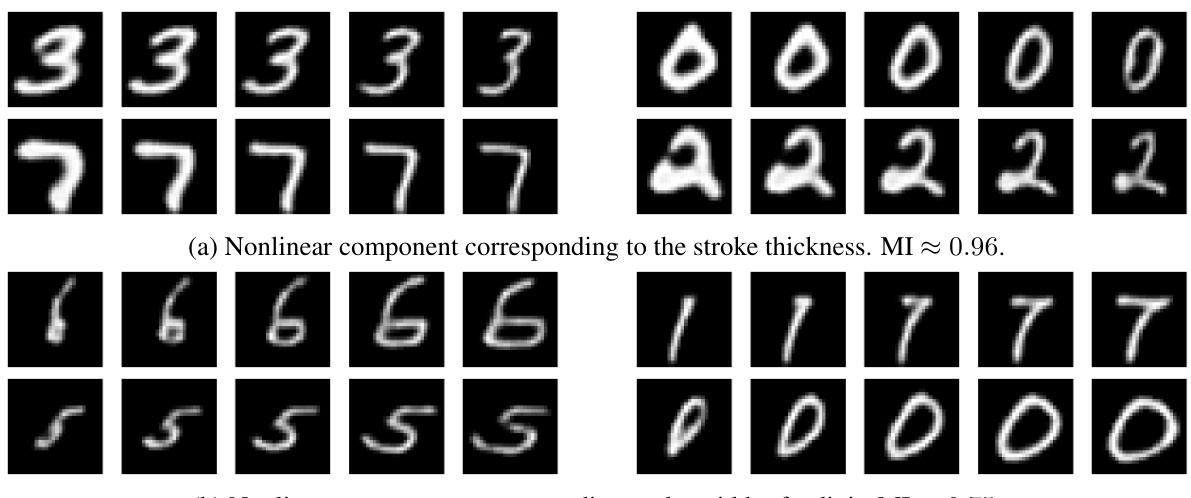

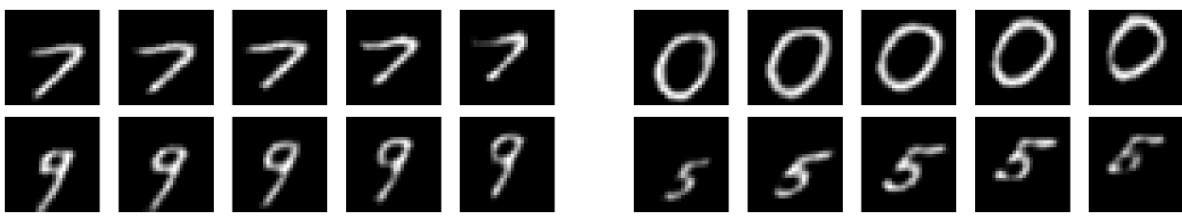

The figure shows the results of applying the proposed method to the MNIST dataset to perform information-based nonlinear canonical correlation analysis. The method estimates mutual information (MI) between augmented versions of handwritten digits and disentangles the underlying nonlinear components. The images illustrate how small perturbations along the axes corresponding to high and low MI values affect the reconstructed images. High MI components represent features invariant to the augmentations (e.g., stroke thickness, digit width), while low MI components represent the augmentations themselves (e.g., translation, zoom).

This figure shows the results of applying an information-based nonlinear canonical correlation analysis to the MNIST handwritten digits dataset. The goal was to estimate the mutual information (MI) between augmented versions of images (translated, rotated, etc.). The tridiagonal version of the proposed method was used, which allowed for simultaneous MI estimation and learning of nonlinear independent components. The figure illustrates the meaning of the learned components through small perturbations along the corresponding axes in the latent space. High MI values indicate features that are invariant to the augmentations used.

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method to the MNIST dataset to perform disentanglement. The method estimates the mutual information between pairs of augmented images (created by applying transformations like translation, rotation, etc.). The figure displays the resulting non-linear components, illustrating how they capture invariant features of the digits (e.g., stroke thickness, width) and those that vary with the transformations (zoom, translation). High MI values indicate components representing features less affected by augmentation.

Full paper#