↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional Neural Architecture Search (NAS) methods are computationally expensive, hindering their widespread adoption. Many recent approaches leverage Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) for efficiency but overlook the non-convex nature of deep neural networks, leading to inaccurate estimations. This significantly limits their ability to accurately predict actual model performance.

MOTE-NAS addresses these challenges by introducing a novel Multi-Objective Training-based Estimate (MOTE). MOTE combines a macro-perspective, modeling the loss landscape to capture non-convexity, with a micro-perspective, considering training convergence speed. Utilizing reduction strategies (reduced architecture and dataset), MOTE-NAS dramatically reduces computational costs. Experiments demonstrate that MOTE-NAS significantly outperforms existing NTK-based methods and achieves state-of-the-art accuracy, with an evaluation-free version achieving comparable performance in only eight minutes.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it significantly advances Neural Architecture Search (NAS) by introducing MOTE-NAS, a highly efficient method that achieves state-of-the-art accuracy while drastically reducing computational costs. This is important due to the ever-increasing demand for efficient and accurate NAS techniques in various applications of deep learning. The evaluation-free version further highlights the potential for significant time savings and broadens the applicability of MOTE-NAS for researchers and practitioners with limited computational resources. The innovative combination of macro and micro perspectives in performance modeling opens new avenues for future NAS research, potentially influencing the design of future efficient NAS algorithms.

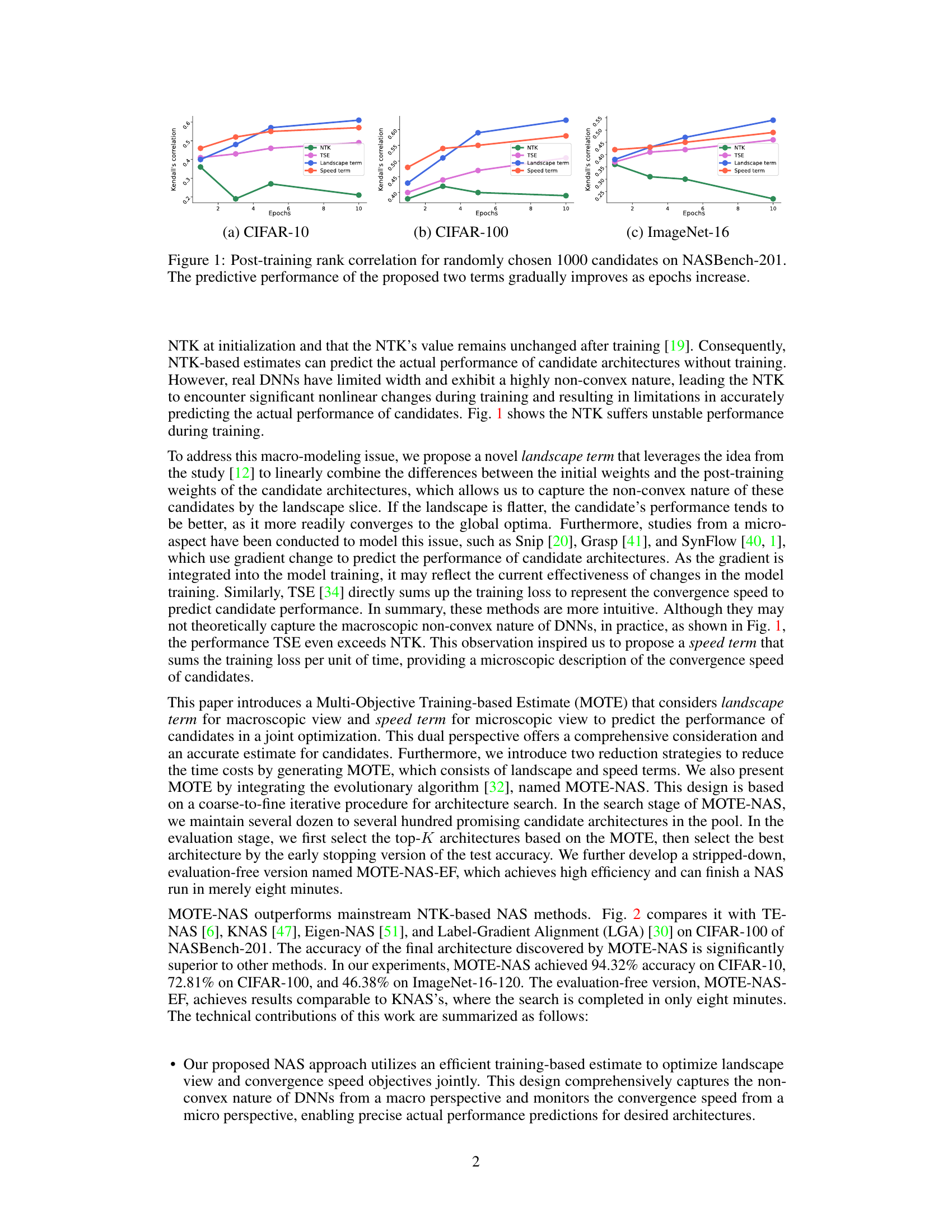

Visual Insights#

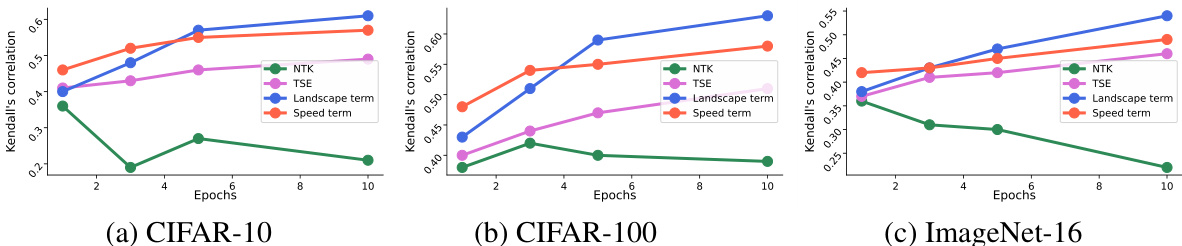

This figure displays the Kendall’s tau correlation between the ranking of 1000 randomly selected architectures from the NASBench-201 dataset based on different performance estimation methods and their actual ranking after 200 training epochs. The x-axis represents the number of training epochs. The y-axis shows the correlation coefficient. Four methods are compared: NTK (Neural Tangent Kernel), TSE (Training Speed Estimation), the proposed landscape term, and the proposed speed term. The figure shows that, while NTK shows an unstable correlation, the proposed landscape and speed terms show a gradually improving correlation with the actual performance as the number of epochs increases, highlighting their effectiveness in predicting actual DNN performance.

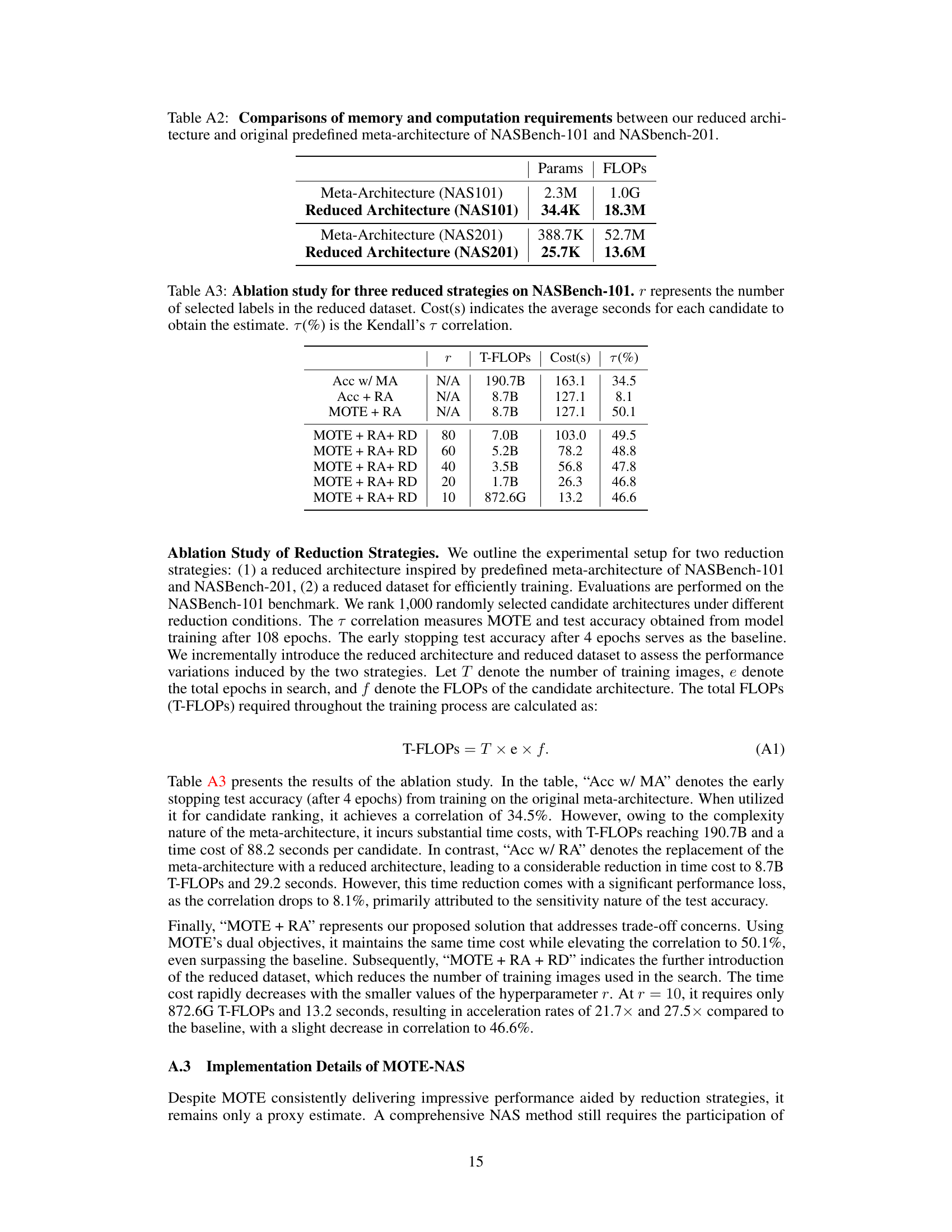

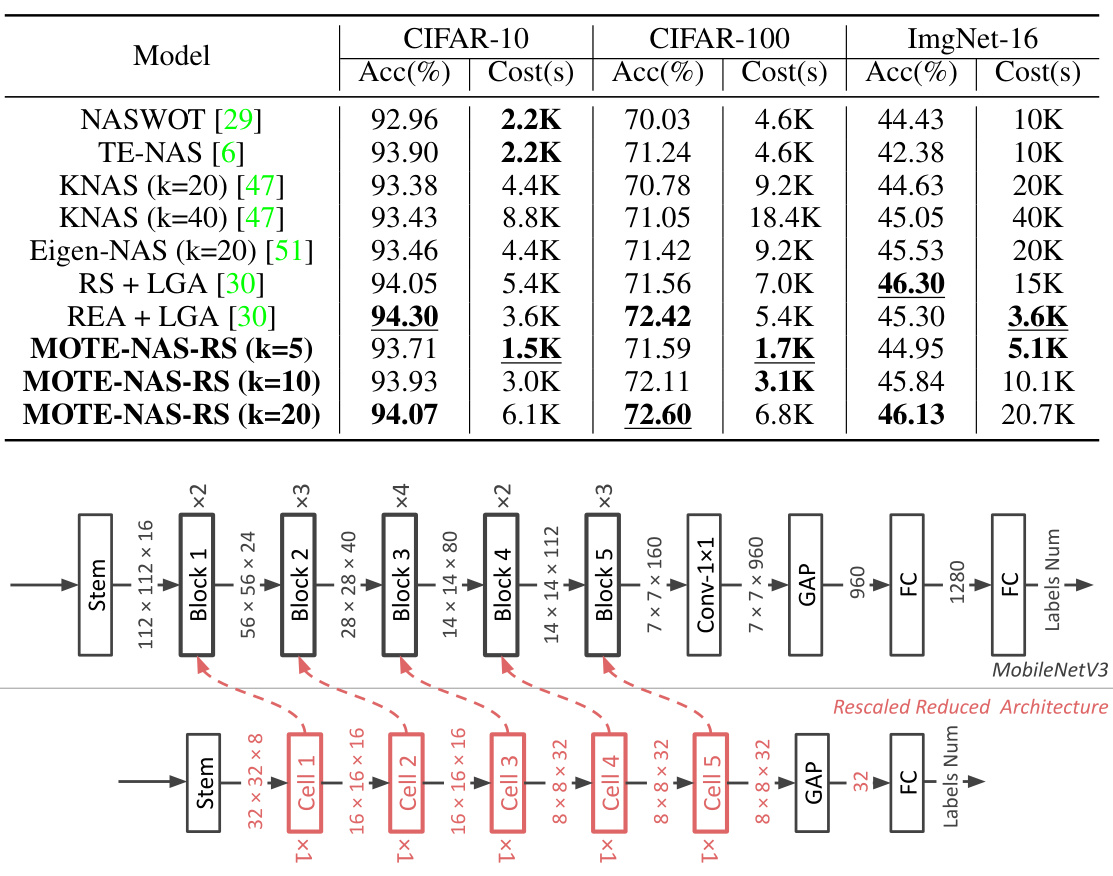

This table compares the performance of MOTE-NAS with other state-of-the-art Neural Architecture Search (NAS) methods on the NASBench-201 benchmark. It shows the accuracy achieved on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-16 datasets, along with the computational cost (in seconds) on a Tesla V100 GPU. The table highlights the superior performance of MOTE-NAS, particularly its efficiency in achieving high accuracy at a lower computational cost compared to other methods.

In-depth insights#

MOTE-NAS Overview#

MOTE-NAS is a novel neural architecture search (NAS) method that addresses the limitations of existing methods by using a multi-objective training-based estimate. Unlike training-free methods that ignore the non-convex nature of deep neural networks (DNNs), MOTE-NAS incorporates both macro and micro perspectives. The macro perspective utilizes a loss landscape term to model the overall performance and convergence properties of DNNs. The micro perspective incorporates a speed term, inspired by Training Speed Estimation (TSE), to capture convergence speed. MOTE-NAS employs two reduction strategies (reduced architecture and reduced dataset) to increase efficiency. These strategies generate the MOTE estimate quickly, facilitating a coarse-to-fine architecture search using an iterative ranking-based, evolutionary approach. The evaluation-free variant, MOTE-NAS-EF, achieves exceptionally high efficiency. Ultimately, MOTE-NAS demonstrates improved accuracy and a substantial reduction in search costs across multiple benchmarks, surpassing the state-of-the-art in accuracy-cost trade-offs.

Multi-Objective Estimate#

A multi-objective estimate in the context of neural architecture search (NAS) aims to optimize multiple, often conflicting objectives simultaneously. This contrasts with single-objective approaches that focus solely on accuracy, neglecting crucial factors like computational cost or training time. A multi-objective approach acknowledges that a model’s ideal architecture isn’t solely determined by its accuracy; resource efficiency and training speed are equally important. Therefore, a multi-objective estimate would incorporate these objectives into a unified evaluation metric, allowing the NAS algorithm to consider trade-offs. For example, it might favor a slightly less accurate model that trains significantly faster or requires fewer resources if that difference is deemed worthwhile considering the overall goal. The key challenge lies in effectively weighting and combining these different objectives which may require careful consideration of the problem context and priorities. This weighting can be fixed or dynamically adjusted during the search process, leading to potentially superior and more robust architectures.

Reduction Strategies#

The heading ‘Reduction Strategies’ in a research paper likely discusses methods to decrease computational cost and time complexity. The core idea revolves around simplifying the process without significantly sacrificing accuracy. This might involve using a reduced architecture (smaller network), a smaller dataset, or both. A reduced architecture could be a simplified version of the original, perhaps with fewer layers or parameters, making training faster and less resource intensive. Reducing the dataset, on the other hand, could focus on the most important samples, potentially through techniques like data augmentation or careful selection, improving efficiency while retaining crucial information. The strategies employed would be carefully evaluated to find the balance between computational savings and performance degradation. The authors would likely justify these choices by demonstrating that the reduction strategies maintain good model performance despite the reduced resources.

Evolutionary Search#

Evolutionary algorithms, when applied to neural architecture search (NAS), offer a powerful alternative to gradient-based methods. They leverage principles of natural selection, mimicking the process of biological evolution to iteratively improve upon network architectures. The core idea involves maintaining a population of candidate architectures, evaluating their performance on a target task, and then using selection and variation operators (e.g., mutation, crossover) to generate a new population of improved architectures. This cycle of evaluation and refinement continues until a satisfactory architecture is identified. Unlike gradient-based approaches, evolutionary algorithms are inherently less susceptible to getting trapped in local optima due to their exploration of a wider search space. However, they often require significantly higher computational resources, particularly for larger search spaces and more complex architectures. The choice between evolutionary and gradient-based search hinges on a tradeoff between exploration capabilities and computational efficiency. While evolutionary search excels in exploring diverse architectural possibilities and finding globally optimal solutions, gradient-based methods are computationally more attractive when convergence speed is critical. Recent research is actively exploring hybrid approaches, which effectively combine the strengths of both methods to harness the advantages of wide exploration while maintaining reasonable computational budgets.

Future of MOTE-NAS#

The future of MOTE-NAS lies in addressing its current limitations and exploring new avenues for improvement. Extending its application to larger and more complex datasets beyond NASBench-201 and ImageNet-1K is crucial. Improving the efficiency of the MOTE estimation process through more sophisticated reduction strategies or alternative proxy models is another key area. Furthermore, research into the theoretical underpinnings of MOTE and its connection to the non-convex optimization landscape in deep neural networks would strengthen its foundation. Investigating the integration of MOTE with other NAS methods, such as reinforcement learning or Bayesian optimization, could lead to hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of different techniques. Finally, exploring the potential of MOTE-NAS for specialized hardware or resource-constrained environments would broaden its applicability and impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

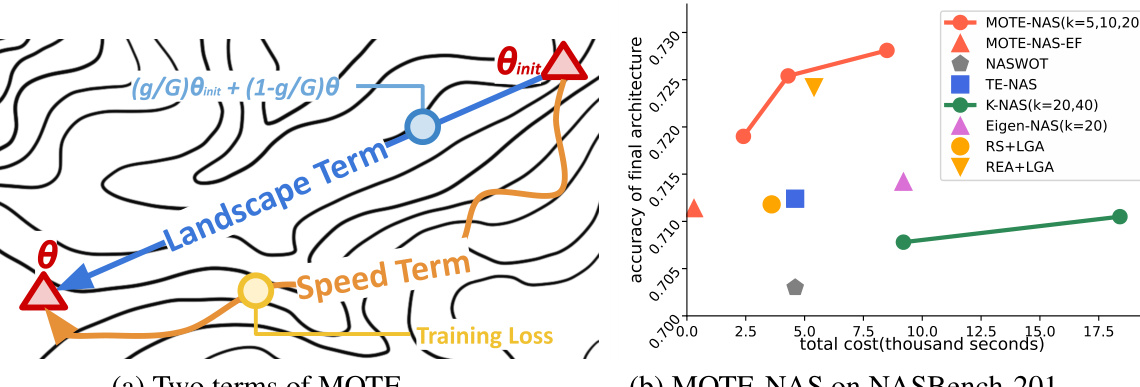

Figure 2(a) shows how the MOTE estimate combines a macro-level loss landscape term with a micro-level training speed term to more accurately estimate the performance of neural network architectures. Figure 2(b) compares the performance of MOTE-NAS and its evaluation-free variant to other state-of-the-art efficient neural architecture search (NAS) methods on the CIFAR-100 subset of the NASBench-201 benchmark. The results demonstrate the superior accuracy and efficiency of MOTE-NAS.

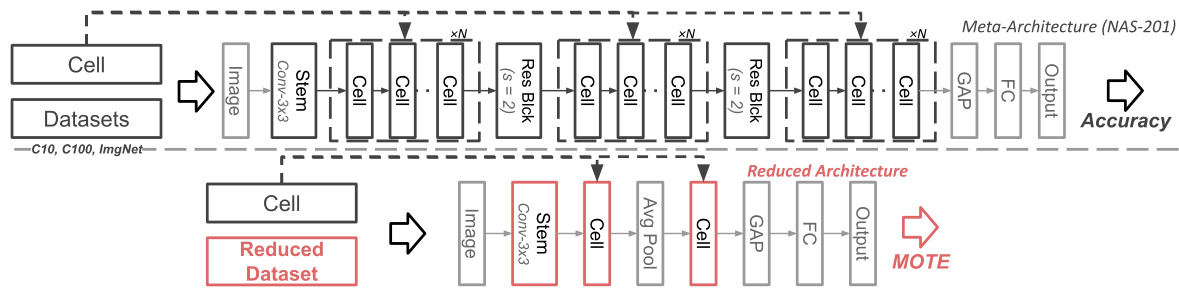

This figure illustrates the process of generating accuracy (top) and MOTE (bottom) estimations. The top section shows the standard process of using a meta-architecture (NAS-201) and datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, ImageNet) to obtain an accuracy measurement. The bottom section details the proposed method using a reduced architecture and dataset to generate the MOTE estimate. The reduced architecture and dataset are highlighted in red, indicating the core components of the proposed efficiency improvement. The reduced architecture simplifies the process to significantly reduce computation time needed.

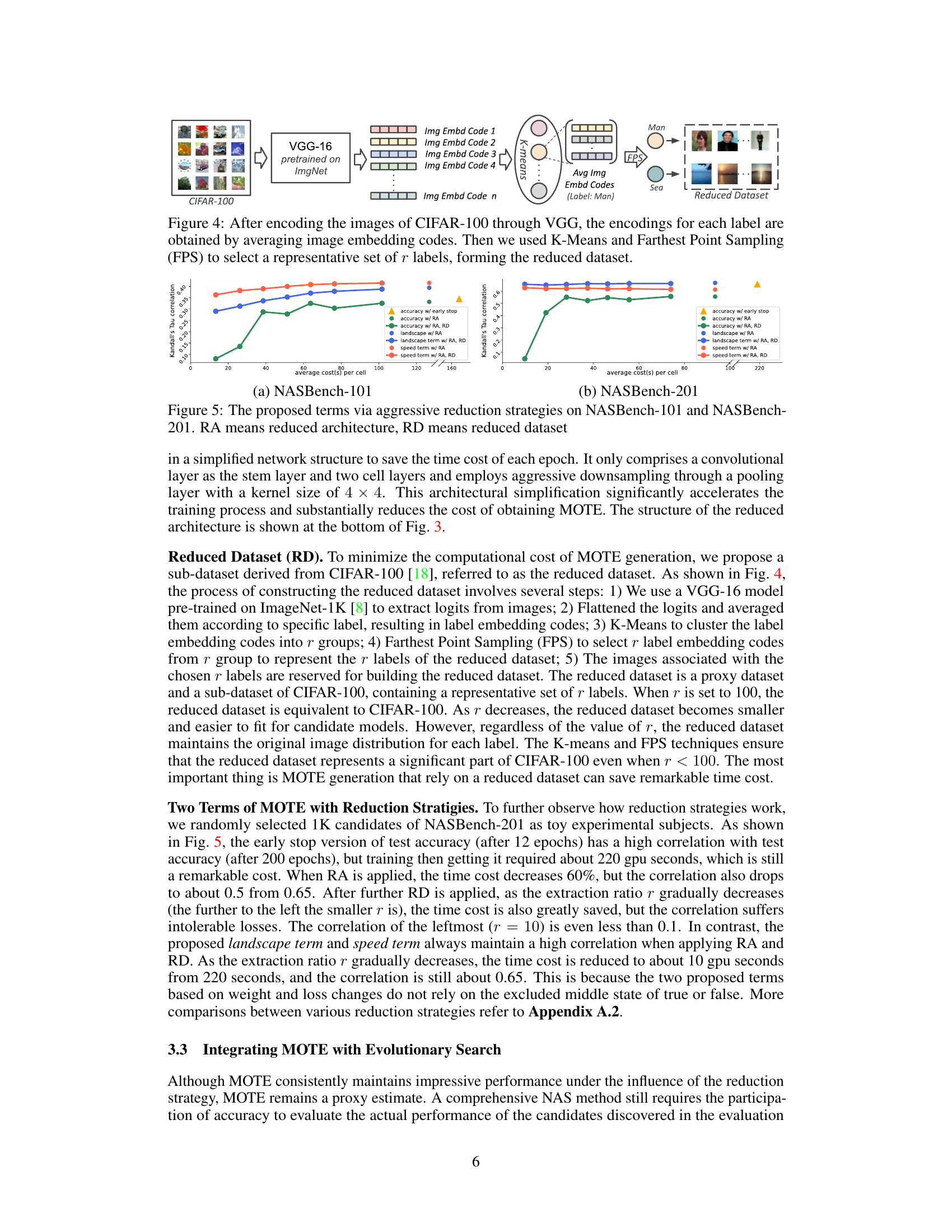

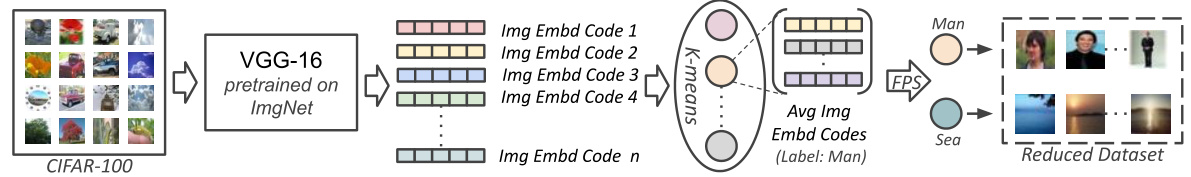

This figure illustrates the process of creating a reduced dataset from the CIFAR-100 dataset. First, images from CIFAR-100 are passed through a pre-trained VGG-16 model to extract image embedding codes. These codes are then averaged for each label, resulting in a single embedding code per label. Next, K-means clustering is used to group similar labels, and farthest point sampling selects the most representative labels from each cluster. The images corresponding to these selected labels form the final reduced dataset, which is significantly smaller than the original CIFAR-100 dataset but retains its key characteristics.

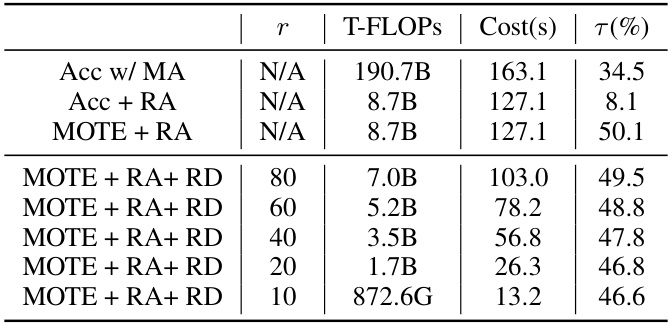

This figure shows the impact of applying reduced architecture (RA) and reduced dataset (RD) strategies on the correlation between estimated and actual performance metrics. It compares the correlation of test accuracy (early stopping vs. 200 epochs) and MOTE components (landscape and speed terms) against the average time cost per cell. The results demonstrate that while aggressive reduction strategies significantly reduce computational costs, they also decrease the accuracy of performance prediction using early stopping. However, MOTE components (especially the speed term) show robust correlation even under aggressive reductions.

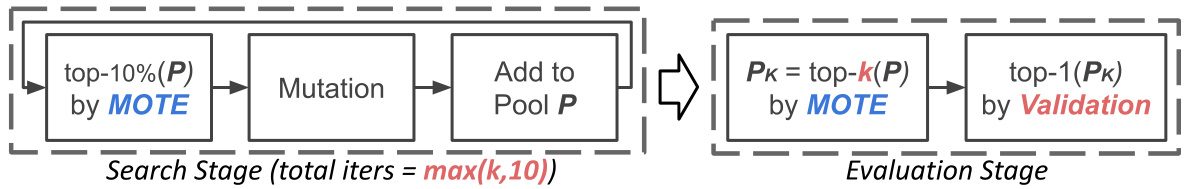

This figure illustrates the workflow of the MOTE-NAS algorithm. The left side shows the search stage, where an evolutionary approach iteratively refines a pool of architectures using MOTE (Multi-Objective Training-based Estimate) for selection. After a set number of iterations (10 + k), the top k architectures are passed to the evaluation stage. The right side shows the evaluation stage, where the top-performing architecture among those k candidates is selected using validation. MOTE-NAS-EF simplifies this process by directly selecting the best architecture using MOTE without the validation stage.

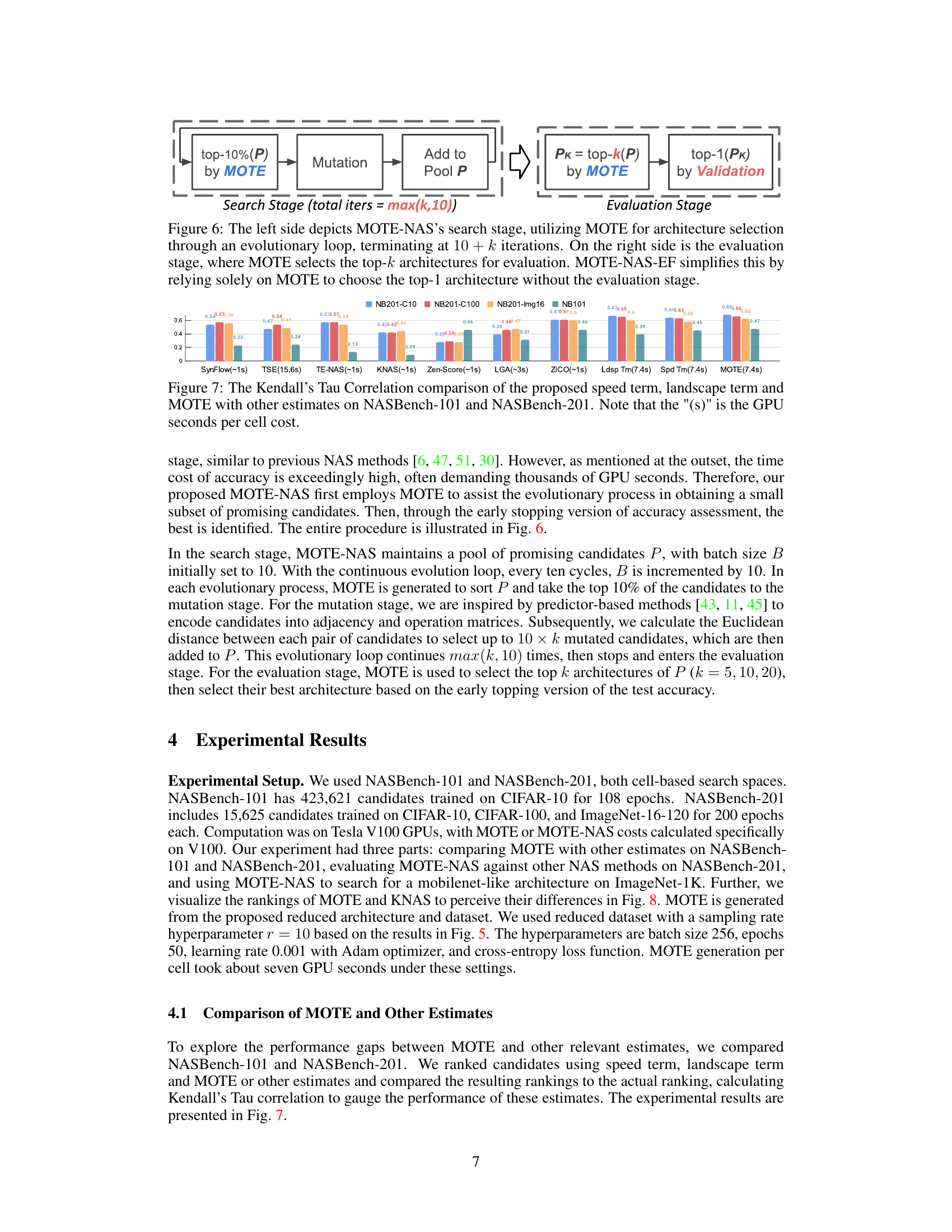

This figure compares the Kendall’s Tau correlation, a measure of rank correlation, between different performance estimation methods and the actual performance ranking on NASBench-101 and NASBench-201 datasets. The methods include SynFlow, TSE, TE-NAS, KNAS, Zen-Score, LGA, ZICO, the proposed landscape term, the proposed speed term, and the proposed MOTE. The x-axis represents each method, while the y-axis shows the Kendall’s Tau correlation for each dataset (NB201-CIFAR10, NB201-CIFAR100, NB201-ImageNet16, and NB101). The numbers in parentheses indicate the GPU seconds per cell cost for each method, showcasing the efficiency of different approaches. The higher the correlation, the better the method’s ability to predict actual performance ranks.

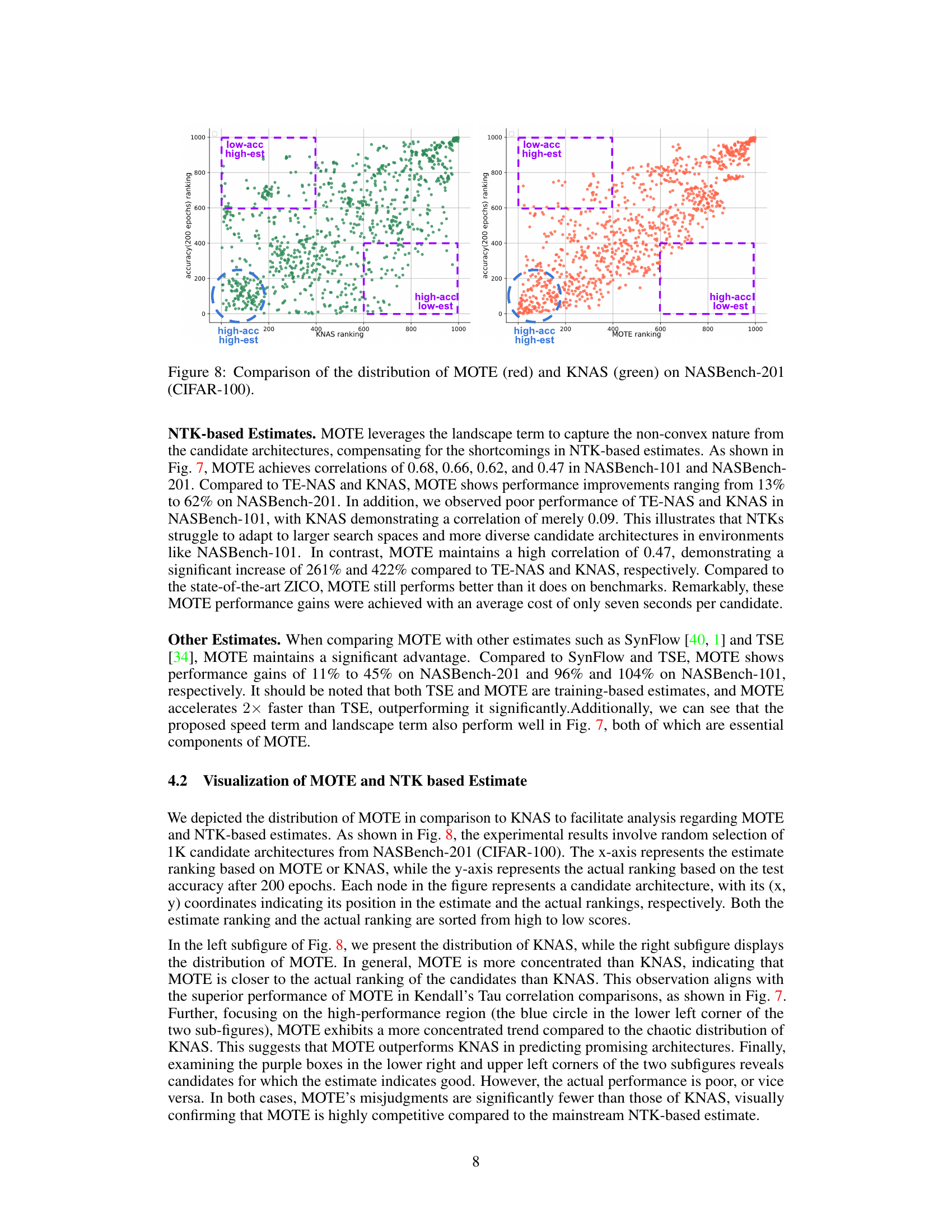

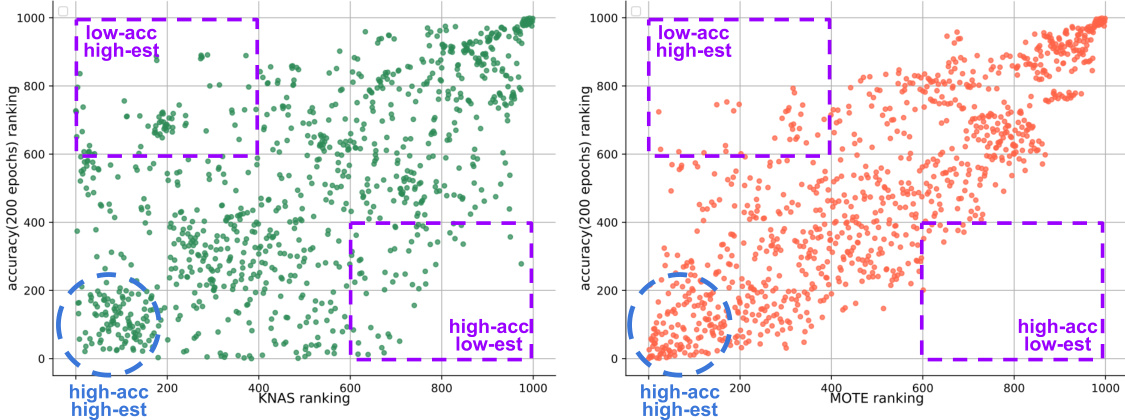

This figure compares the performance of MOTE and KNAS in ranking candidate architectures on the NASBench-201 benchmark using CIFAR-100. Each point represents a candidate architecture. The x-axis shows the rank assigned by either MOTE or KNAS, while the y-axis shows the actual rank determined by the test accuracy after 200 epochs of training. The plot reveals that MOTE’s rankings are more tightly clustered around the diagonal (perfect correlation) than KNAS, indicating that MOTE is a more accurate predictor of actual performance. The clustering of points in the lower-left (high accuracy, high estimate rank) and upper-right (low accuracy, low estimate rank) quadrants also illustrates the accuracy of MOTE and KNAS in identifying high and low performing candidates.

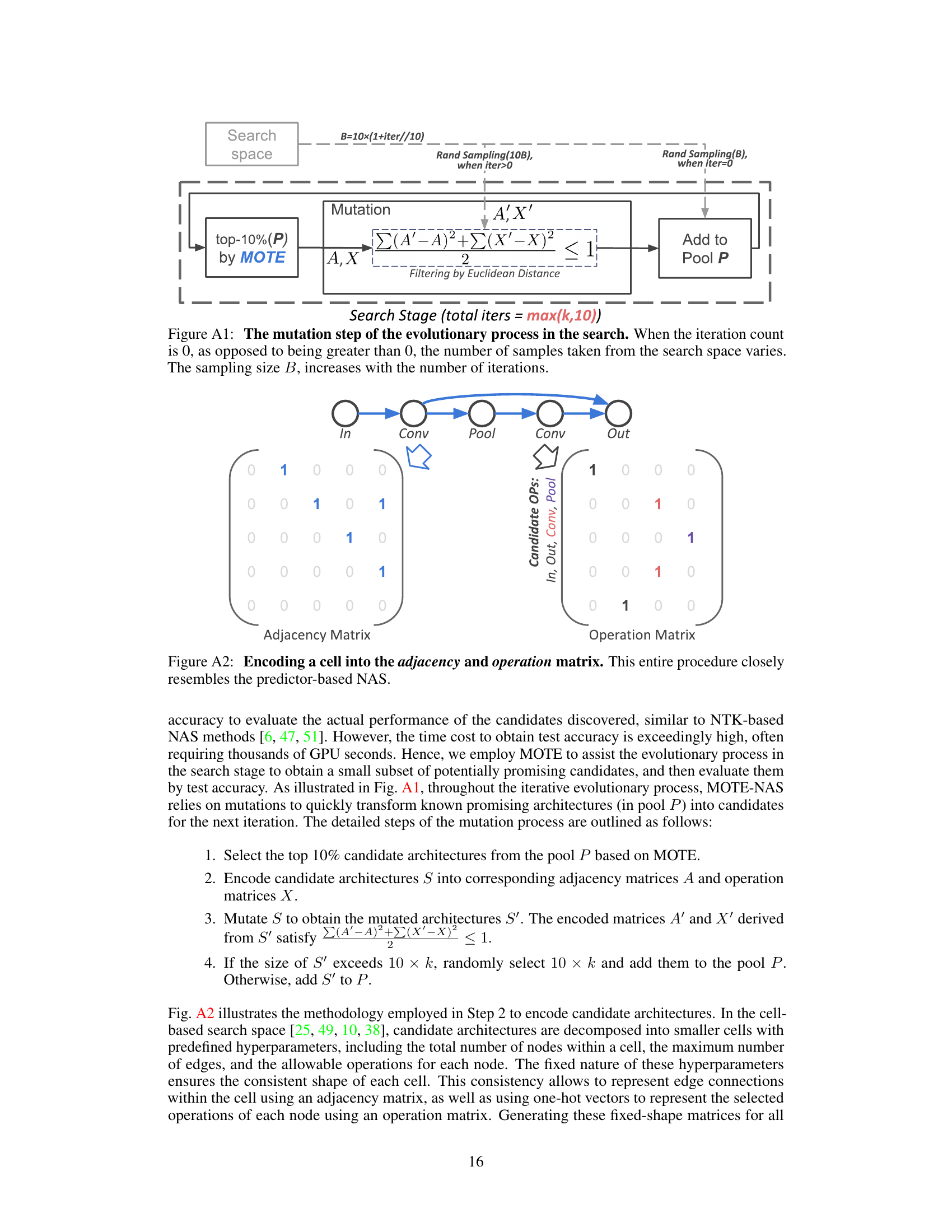

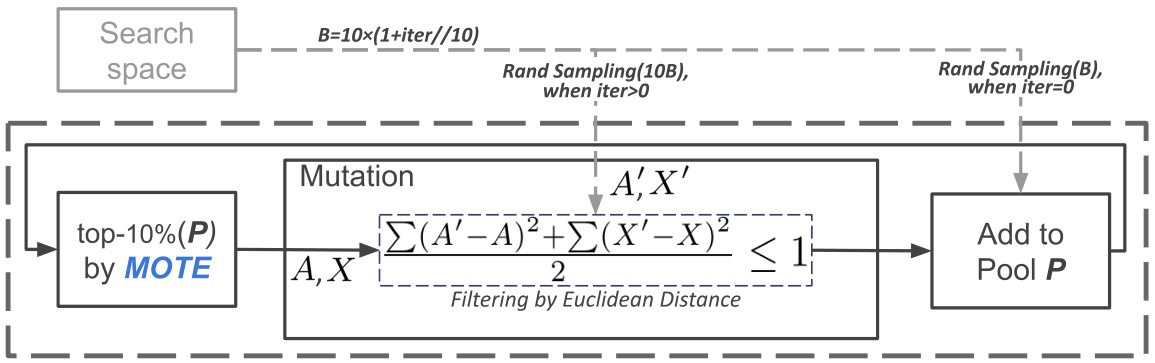

This figure illustrates the mutation process within the evolutionary search algorithm of MOTE-NAS. The process starts by selecting the top 10% of candidates from the pool (P) based on the MOTE estimate. These selected candidates are then encoded into adjacency (A) and operation (X) matrices. The mutation step involves creating modified architectures (S’) by altering these matrices, ensuring that the Euclidean distance between the original and modified matrices remains below a threshold of 1. The number of samples drawn from the search space dynamically increases as the iteration count rises, starting with B samples at iteration 0. Finally, these newly generated candidates are added back into the pool P for further consideration.

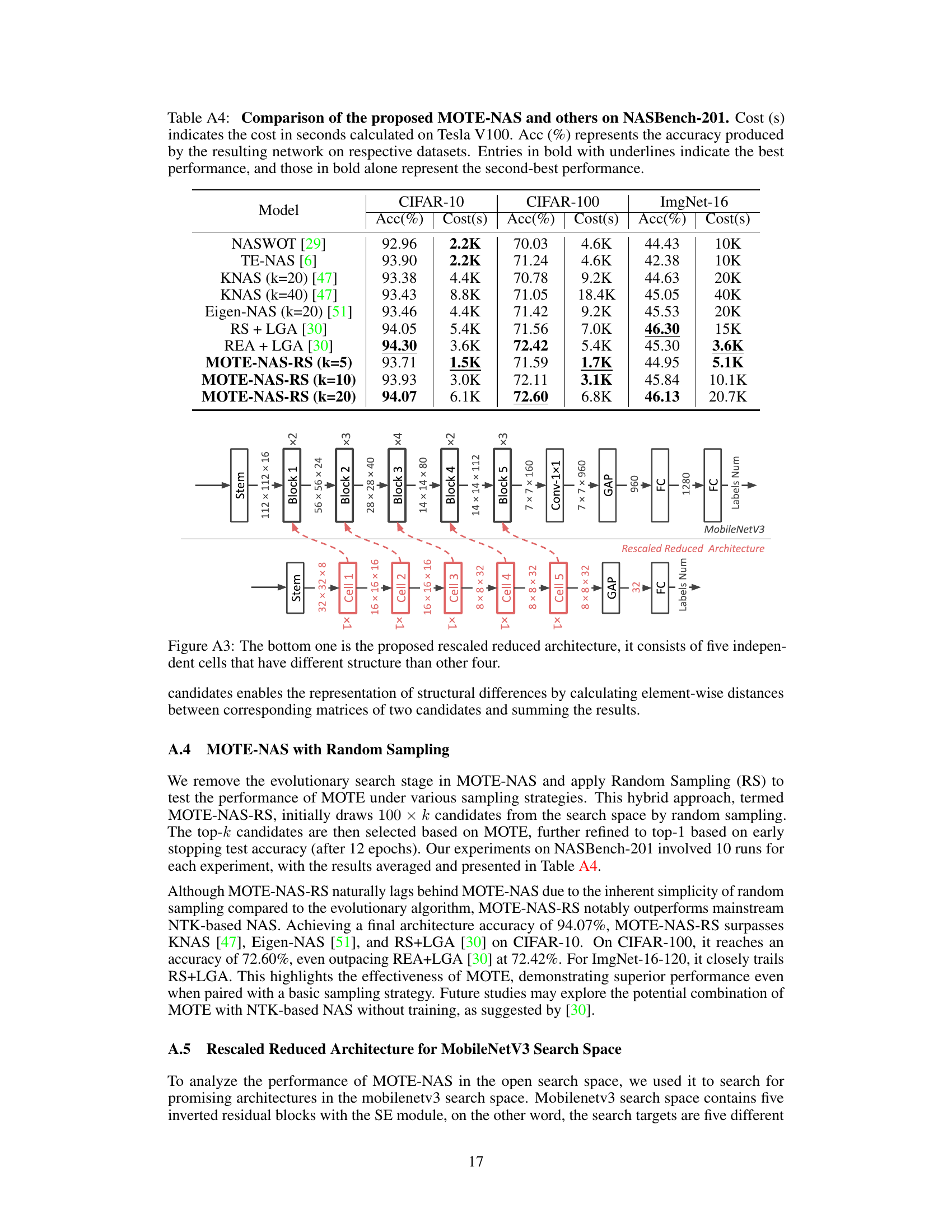

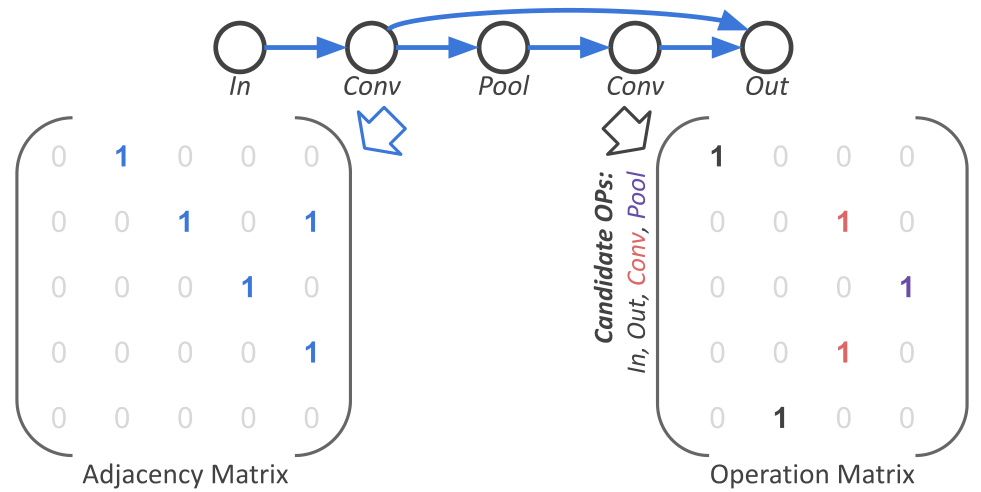

This figure illustrates how a cell in a cell-based neural architecture search space is represented using two matrices: an adjacency matrix and an operation matrix. The adjacency matrix shows the connections between nodes in the cell, while the operation matrix indicates the type of operation performed at each node. This encoding method simplifies the representation of complex architectures, making it easier to perform architecture search. The encoding method closely resembles that of predictor-based NAS methods.

More on tables

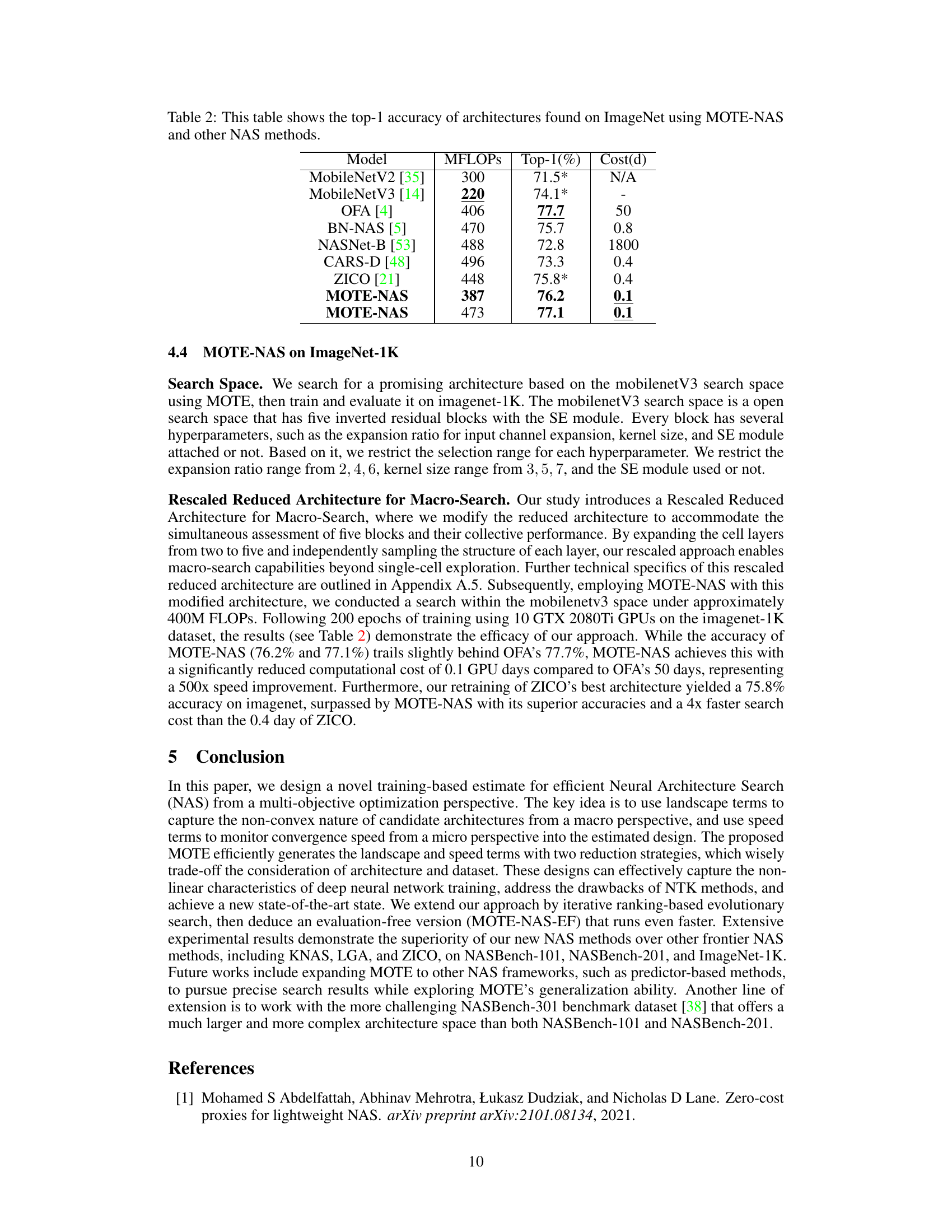

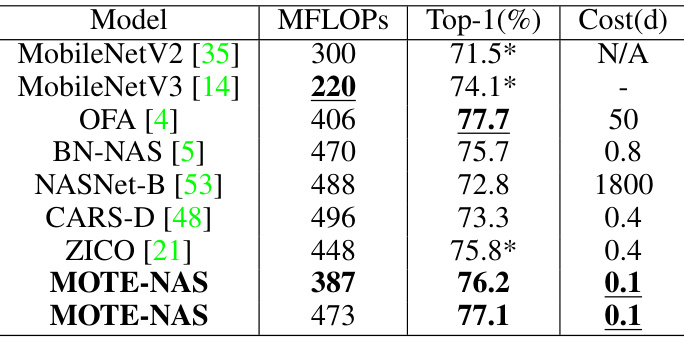

This table compares the top-1 accuracy achieved on the ImageNet dataset by different Neural Architecture Search (NAS) methods. It includes several well-known models (MobileNetV2, MobileNetV3, OFA, BN-NAS, NASNet-B, CARS-D, ZICO) and two versions of the proposed MOTE-NAS approach. The table also indicates the number of Million FLOPS (MFLOPS) required by each model and the cost in days (Cost(d)) to train.

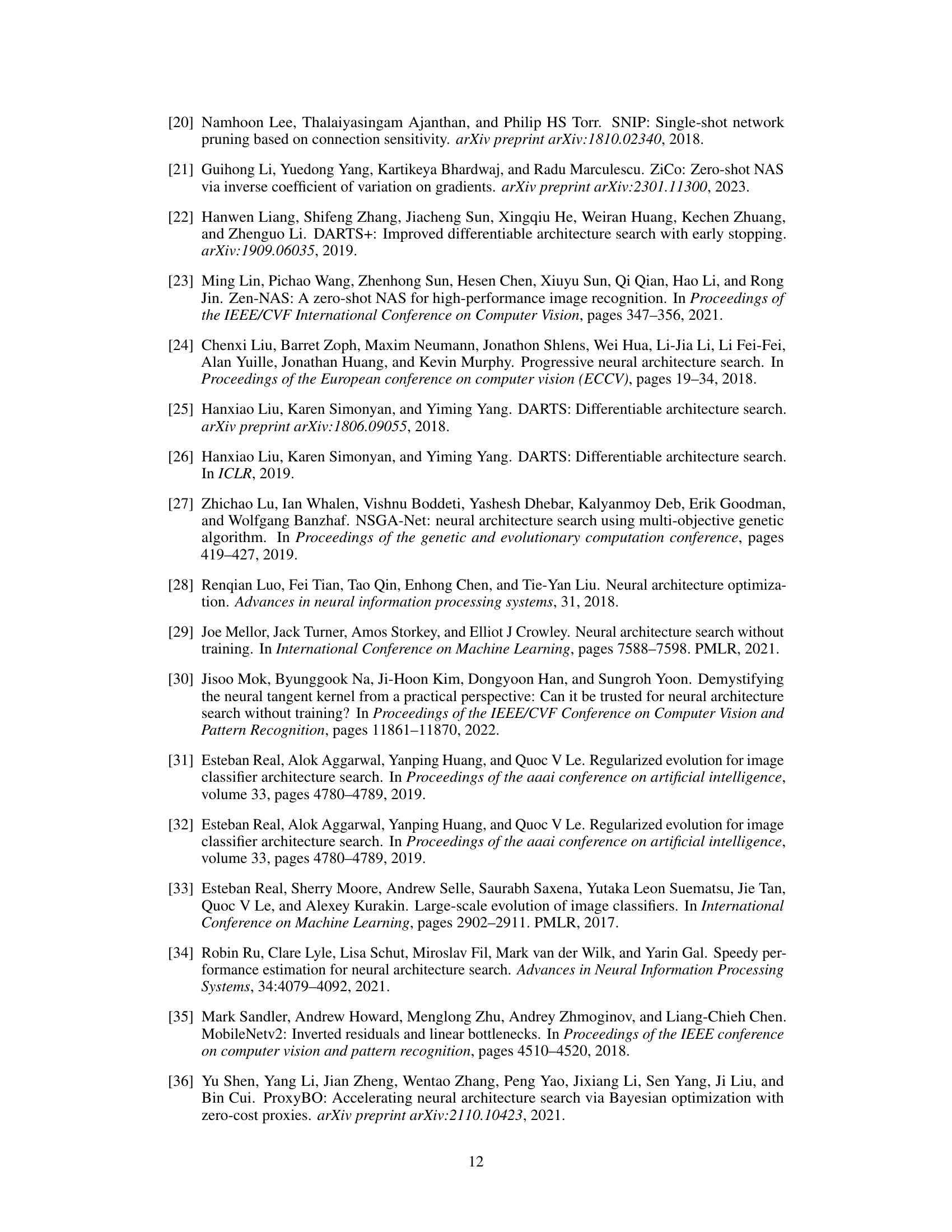

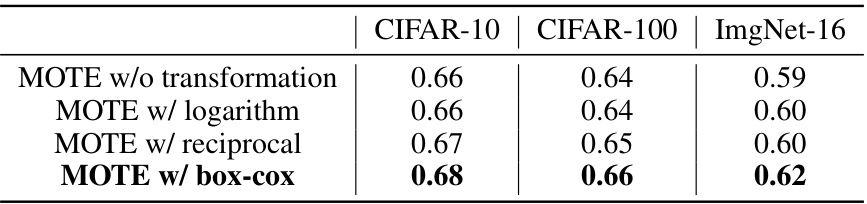

This table presents the Kendall’s Tau correlation, a measure of rank correlation, between the MOTE scores and the actual test accuracy on three image classification datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-16) from NASBench-201. The MOTE scores are generated using four different transformations (no transformation, logarithm, reciprocal, and box-cox) applied to the MOTE values. The table shows how different transformations of the MOTE values affect the correlation with the actual accuracy rankings.

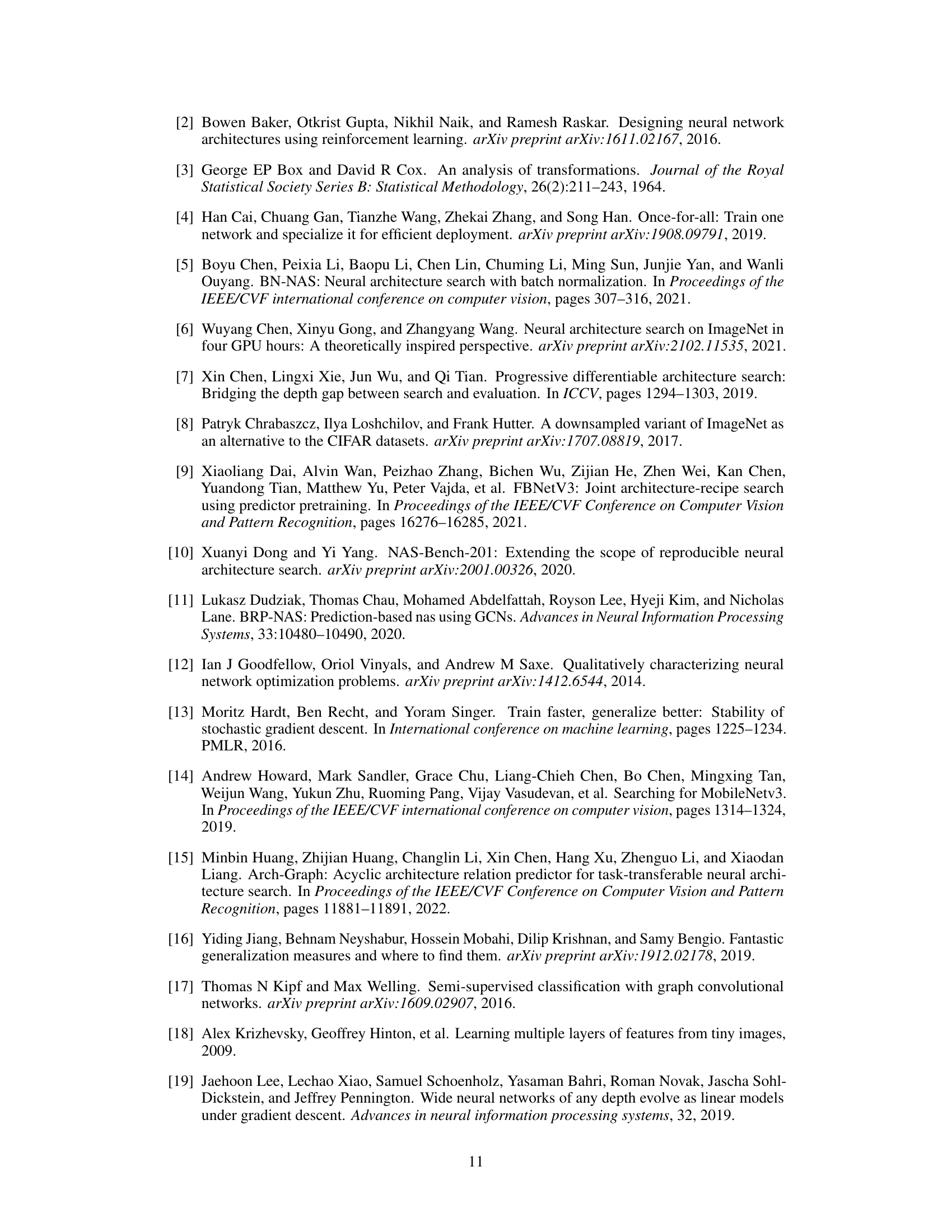

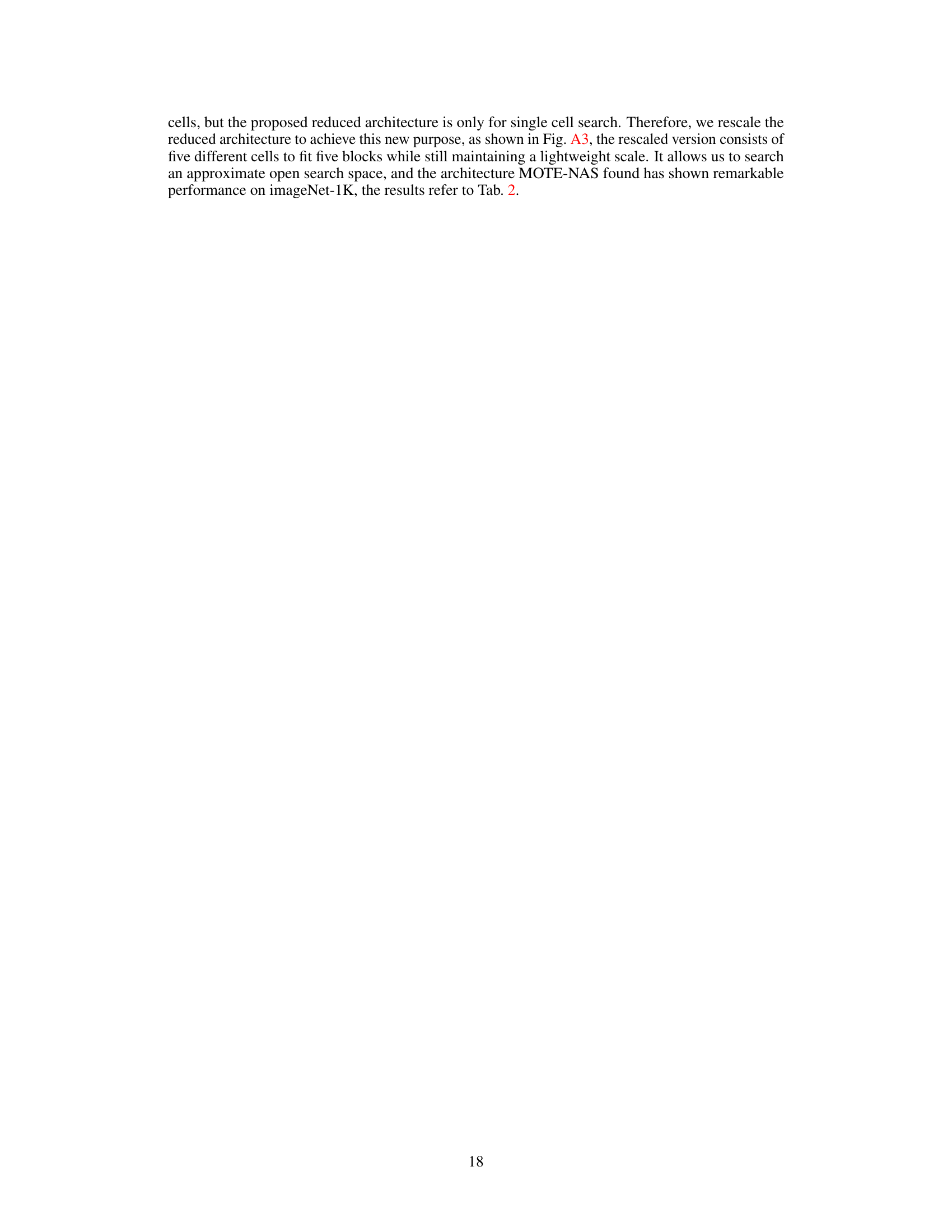

This table compares the performance of MOTE-NAS against other state-of-the-art neural architecture search (NAS) methods on the NASBench-201 benchmark. It shows the accuracy achieved by each method on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-16, as well as the computational cost in seconds on a Tesla V100 GPU. The best and second-best performance is indicated.

This table compares the performance of MOTE-NAS with other state-of-the-art Neural Architecture Search (NAS) methods on the NASBench-201 benchmark. It shows the accuracy achieved on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-16 datasets, along with the computational cost (in seconds) required for each method. The best and second-best performances are highlighted.

This table compares the performance of MOTE-NAS with other state-of-the-art Neural Architecture Search (NAS) methods on the NASBench-201 benchmark. It shows the accuracy achieved by each method on three datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-16), along with the computational cost (in seconds) required to obtain those results. The best and second-best results for each dataset are highlighted.

Full paper#