↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Machine learning models often exhibit implicit bias—a tendency to favor simpler solutions even when more complex ones exist. While this phenomenon is well-understood in binary classification, its multiclass counterpart is less explored, with limited research focusing primarily on cross-entropy loss. This limits our understanding of how various multiclass loss functions influence model complexity and behavior during training.

This paper addresses this gap by introducing a multiclass extension of the exponential tail property, utilizing the Permutation Equivariant and Relative Margin-based (PERM) loss framework. The researchers extend the implicit bias results of previous work to the multiclass setting, proving that gradient descent exhibits a preference for simple solutions when the loss function satisfies the extended exponential tail property. This provides a broader understanding of implicit bias beyond the commonly studied cross-entropy loss and enhances the theoretical foundation of multiclass learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap in understanding implicit bias in multiclass classification, a significant challenge in machine learning. It introduces a novel framework and theoretical results which advance the field and opens new avenues for research in overparameterized models and optimization algorithms. This work is relevant to researchers exploring generalization in deep learning and the behavior of gradient descent.

Visual Insights#

Figure 1 illustrates the exponential tail property for the cross-entropy loss. Panel (a) shows the template function for the multinomial logistic loss which is a 2D function. Panels (b) and (c) show the upper and lower bounds for the partial derivative of the template function. The lower bound is valid in the positive orthant.

In-depth insights#

Implicit Bias Theory#

Implicit bias theory explores the phenomenon where machine learning algorithms, even without explicit regularization, exhibit a preference for simpler solutions. Gradient descent, a common optimization algorithm, is frequently studied in this context. The theory attempts to explain why models trained on separable data often converge to maximum-margin solutions, rather than other equally good solutions. This preference for simplicity is a form of regularization that emerges implicitly from the optimization process itself. A key aspect is the loss function used, as its properties heavily influence the algorithm’s behavior. For example, exponential tail properties of the loss function are frequently identified as leading to maximum margin solutions. Recent work has focused on extending these binary classification results to the more complex multiclass setting, where the analysis becomes significantly more challenging. However, significant progress is being made using novel frameworks like permutation equivariant and relative margin based losses to bridge this gap. Further research is needed to understand how implicit biases may vary across different models, data characteristics, and optimization techniques.

Multiclass Extension#

Extending binary classification models to handle multiple classes presents unique challenges. A naive approach might involve a series of one-versus-rest or one-versus-one binary classifiers, but this can lead to inconsistencies and suboptimal performance. A more sophisticated multiclass extension needs to consider the relationships between classes and incorporate them into the model’s structure. This might involve using a softmax function to produce class probabilities or designing a loss function that accounts for the relative margins between classes. The theoretical analysis of implicit bias in multiclass settings also requires careful consideration of loss functions and their properties. A successful multiclass extension needs to demonstrate improved accuracy and efficiency over binary-based methods, while maintaining theoretical guarantees such as convergence and generalization bounds. The challenge lies in balancing the complexity of the model with its ability to capture fine-grained class distinctions. Developing robust, scalable, and well-understood multiclass extensions remains a crucial area of research in machine learning.

PERM Loss Analysis#

A hypothetical “PERM Loss Analysis” section would delve into the properties and implications of permutation-equivariant and relative margin-based (PERM) losses for multiclass classification. It would likely begin by formally defining PERM losses, highlighting their key characteristics: permutation equivariance (loss remains unchanged under label permutations) and relative margin-based structure (loss depends on differences between scores). The analysis would then explore how these properties translate into desirable theoretical features, such as generalization guarantees and connections to maximum margin classifiers. A crucial aspect would be examining how specific loss functions (like cross-entropy) fit within the PERM framework, establishing if they satisfy the conditions for desirable behavior. This would likely involve mathematical proofs and analyses that formally demonstrate the effects of these properties on the gradient descent dynamics during model training, potentially establishing connections to the implicit bias phenomenon. Finally, the section would conclude by discussing the advantages of the PERM framework over traditional multiclass loss analysis, emphasizing its ability to unify and generalize results from binary to multiclass settings and offering new insights into the behavior of gradient-based optimization algorithms.

Gradient Descent Limits#

The heading ‘Gradient Descent Limits’ suggests an exploration of the inherent boundaries and constraints of gradient descent algorithms. A thoughtful analysis would likely investigate scenarios where gradient descent fails to converge to a global optimum, gets trapped in local minima, or exhibits slow convergence rates. Key factors influencing these limitations might include the choice of learning rate, the structure of the loss function (convexity, smoothness), the presence of saddle points in the loss landscape, and the dimensionality of the data. The analysis could delve into theoretical bounds on convergence rates, possibly demonstrating scenarios with provably slow convergence or divergence. Furthermore, the paper might explore practical implications of these limits, such as the difficulty in training complex models like deep neural networks with gradient descent and the need for sophisticated optimization techniques like momentum, Adam, or adaptive learning rates to mitigate these issues. It could also touch upon the relationship between these limits and the implicit bias of gradient descent, exploring how the algorithm’s inherent biases may interact with its convergence limitations. Finally, a discussion of the trade-offs between optimization speed and the quality of the solution found would be appropriate, highlighting how gradient descent’s limitations often necessitate compromises in practice.

Future Research#

The paper’s findings open several avenues for future research. Extending the implicit bias analysis beyond linearly separable data is crucial, as real-world datasets rarely exhibit perfect separability. Investigating the impact of different model architectures and the interplay between model capacity and implicit bias would provide further insights. Analyzing the behavior of gradient descent with non-ET losses is necessary to fully understand the scope of implicit bias. Furthermore, a rigorous analysis of convergence rates is essential for practical applications. Finally, exploring the connection between implicit bias and generalization in the multiclass context would be valuable, and comparing these results to binary classification would offer important contrasts.

More visual insights#

More on figures

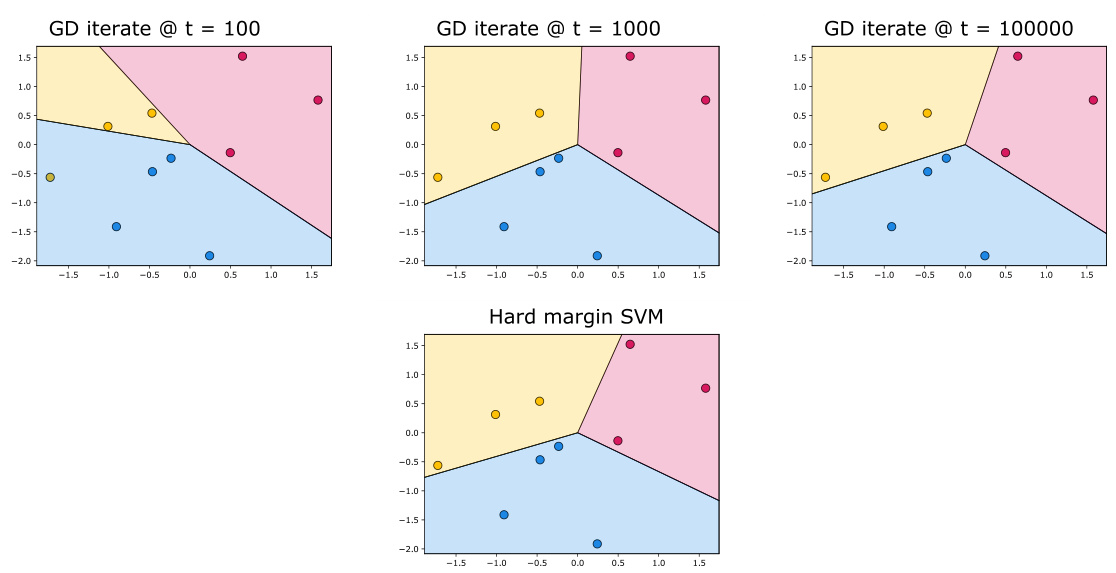

This figure shows a small simulation with 10 data points in 2 dimensions and 3 classes. The PairLogLoss function was used. The top row displays the decision regions of the classifiers along the gradient descent path at different iteration counts (100, 1000, and 100000). The bottom row shows the decision regions for the hard-margin multiclass SVM. The figure highlights that most of the convergence towards the hard-margin SVM happens in the early iterations.

This figure shows the results of 10 independent large simulations using the PairLogLoss function. Each simulation involves 100 data points (N=100) in 10 dimensions (d=10), with 3 classes (K=3). The y-axis shows the ratio of the Frobenius norm of the weight matrix at a given iteration (||W(t)||F) to the Frobenius norm of the weight matrix of the hard margin SVM solution (||ŵ||F). The x-axis indicates the number of gradient descent steps. The plot shows that convergence to the hard-margin solution happens slowly in log-log space, indicating a logarithmic convergence rate.

Full paper#